The American musician Taylor Swift has influenced popular culture with her music, artistry, performances, image, politics, beliefs and actions, collectively referred to as the Taylor Swift effect by publications. Debuting as a 16-year-old independent singer-songwriter in 2006, Swift steadily amassed fame, success, and public curiosity in her career, becoming a monocultural figure.

One of the most prominent celebrities of the 21st century, Swift is recognized for her versatile musicality, songwriting prowess, and business acuity that have inspired artists and entrepreneurs worldwide. She began in country music, ventured into pop, and explored alternative rock, indie folk and electronic styles, blurring music genre boundaries. Critics describe her as a cultural quintessence wielding a rare combination of chart success, critical acclaim, and intense fan support, resulting in her wide impact on and beyond the music industry.

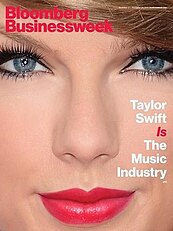

From the end of the album era to the rise of the Internet, Swift has driven the evolution of music distribution, perception, and consumption across the 2000s, 2010s, and 2020s, and has used social media to spotlight issues within the industry and society at large. Having forged a strong economic and political leverage, she prompted reforms to recording, streaming, and distribution structures for greater artists' rights, increased awareness of creative ownership in terms of masters and intellectual property, and has led the vinyl revival. Her consistent commercial success is considered unprecedented by journalists, with simultaneous achievements in album sales, digital sales, streaming, airplay, vinyl sales, record charts, and touring. Bloomberg Businessweek stated she is "The Music Industry",[13] one of her many honorific sobriquets. According to Billboard, Swift is "an advocate, a style icon, a marketing wiz, a prolific songwriter, a pusher of visual boundaries and a record-breaking road warrior".[14]

Swift is a subject of academic research, media studies, and cultural analysis, generally focused on concepts of poptimism, feminism, capitalism, internet culture, celebrity culture, consumerism, Americanism, post-postmodernism, and other sociomusicological phenomena. Several academic institutions offer courses on her. Scholars have variably attributed Swift's dominant cultural presence to her musical sensibility, artistic integrity, global engagement, intergenerational appeal, public image, and marketing acumen. Several authors have used the adjective "Swiftian" to describe works reminiscent or derivative of Swift.

Fame and stardom[edit]

Taylor Swift is one of the highest selling music artists of all time.[15] She is the richest female musician and the first billionaire in history with music as the main source of income (US$1,100,000,000, as of 2023).[16][17] She has released 11 studio albums and four re-recorded albums, supported by a number of singles, apart from her non-album songs and collaborations.[18] All of her albums were commercially lucrative and positively received by music critics. Billboard noted that only a handful of artists have had Swift's trifecta of chart success, critical acclaim, and fan support, resulting in her widespread impact.[15]

Several publications note Swift's popularity and longevity as the kind of "ceaseless" fame and "global influence" unseen since the 20th century.[19][20] To CNN, Swift began the 2010s decade as a country star and ended it as an "all-time musical titan".[21] New York's Jody Rosen and Chicago Tribune's Steve Chapman called Swift the world's biggest pop star and music star, respectively, leaving her peers "vying for second place" as per Rosen.[22][23] Elle and Fortune have described Swift as "pop megastar at celestial echelons" and "the world's greatest female leader", respectively.[24][25]

Cultural presence[edit]

Taylor Swift is the biggest thing going in the entertainment industry. Turn on the TV or radio, scroll social media, listen to talk on the street, and there she is.

Shirley McMarlin, Pittsburgh Tribune-Review (2023)[26]

Journalists describe Swift as a cultural touchstone. The Guardian columnist Greg Jericho dubbed Swift a "cultural vitality" whose consistent popularity, accentuated by the era of internet, surpassed that of the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, David Bowie, Bruce Springsteen and U2, all of whom had a short-lived commercial and critical prime, whereas Swift continued to find success in the 18th year of her career with her tenth studio album, Midnights (2022). Jericho stated that only Drake, Kanye West and Beyoncé could compete with Swift in terms of popularity, while deeming Swift the most popular female artist of the 21st century;[4] Drake mentioned Swift in his 2023 song "Red Button", with lyrics "Taylor Swift the only nigga that I ever rated / Only one could make me drop the album just a little later".[10] Chris Molanphy of Slate stated that Swift's career has lasted longer than that of the Beatles, breaking the band's once-deemed "unbeatable" records.[7] Multiple journalists have compared her fame to that of Michael Jackson or Madonna.[27][28] The New York Times author Ben Sisario felt Swift's cultural dominance competes with Jackson and Madonna in the 1980s, calling it something the "entertainment business had largely accepted as impossible to replicate in the fragmented 21st century."[9] Many critics, including Sam Lansky of Time, consider Swift one of the last monocultural entities in the world.[29][5][10][30]

Within celebrity culture, Swift's music, life, and image are points of attention.[31][32] Swift became a teen idol upon the release of her eponymous debut studio album in 2006,[33] and has since become a dominant figure in popular culture,[11] often referred to as a pop icon or diva.[34][35][22] Gayle Pamerleau of the University of Pittsburgh at Greensburg credited globalization for Swift's fame and called her a social contagion benefitting "from existing in a time of 24-hour, global connectedness, when everybody knows what everyone else is thinking and doing."[26] The Ringer's Kate Knibbs called Swift inescapable as her music saturates "deep into the tissue of contemporary public life whether we like it or not."[36] Hence, Swift's career choices result in reforms in the music industry. In a 2016 article, Billboard opined that despite having had only a decade-old career, Swift had shown an "undeniable" cultural impact.[37][25]

Kirsty Fairclough of the University of Salford dubbed Swift "the center of the cultural universe."[38] Billboard journalists felt that "her presence in popular music is the same as popular music itself. She's firing on all cylinders, across multiple mediums and eras, and has zero peers on her level",[39] whereas News.com.au asserted "there hasn't probably been anyone on the planet as culturally significant as Swift ever."[2] Writing for CNN, Scottie Andrew felt that "whenever there's a lull in the cultural discourse", Swift becomes the topic of focus.[40] Billie Schwab Dunn of Newsweek remarked, "Swift has dominated the marketplace, a large portion of the cultural zeitgeist and media attention like no other artist before her".[3] Kyle Chayka of The New Yorker felt Swift is a heroic figure like Napoleon and Julius Caesar, all of whom are "agents of the world-spirit" and symbolic of their respective periods in time.[41]

Time included Swift on its 2010, 2015 and 2019 rankings of the 100 most influential people.[42] In 2014, she was named to Forbes' 30 Under 30 list in the music category.[43] Swift became the youngest woman to be included on Forbes' list of the 100 most powerful women in 2015, ranked at number 64,[44] and the first entertainer to ever place in the list's top five in 2023.[45] She was the most googled woman in 2019 and musician in 2022,[46][47] as well as the most googled songwriter of all time,[48] and The Guardian named her the most powerful woman in U.K. media.[49] Media outlets noted that she reached a new zenith of fame in 2023, with Glamour saying she "has officially taken over every aspect of popular culture."[50][32][11] Describing a critical consensus, writer Jeff Yang said Swift is "increasingly being spoken about as an economic force of nature, a transformative creator advocate, organizer and innovator and arguably the most influential and even the most powerful figure in the music industry."[12]

American symbol[edit]

Journalists associate Swift's fame with Americanism. According to Knibbs, with her second studio album Fearless (2008), Swift had become a "countrified celebrity solidified into industrial-grade American fame" due to her craftsmanship.[36] Jack Dickey of Time said, Swift became "America's most important musician" by 2014.[51] Maxim called her career "a quintessential American success story".[52] Collider contributor Shaina Weatherhead wrote that "Whether she likes it or not, Taylor Swift has become a pillar of the cultural zeitgeist", embodying love, diligence and feminism. Weatherhead added Swift's fame turned her into a staple of American culture beyond just American music.[53]

Journalists such as Ann Jamieson of Tampa Bay Times, MSNBC's Michael A. Cohen and NBC News' Kaetlyn Liddy have described Swift as an "American treasure",[54] "the most famous and influential cultural icon" in the U.S.,[55] and "synonymous with American pop culture", respectively.[56] Writer Anna Mark felt that the Swift's hold on popular culture impacted American culture in the process.[57] In an op-ed for The Washington Post, Eugene Robinson opined Swift and the Super Bowl are two of the most beloved phenomena in American culture.[58]

Cultural critic Greil Marcus noted that Swift "wears the American flag on her face"—red lips, white skin, and blue eyes.[20] According to Vulture writer Nate Jones, Swift is the "musical embodiment of American hegemony",[59] while The Wall Street Journal columnist Peggy Noonan felt Americans should be thankful to Swift, as her career is an "epic American story".[60] Emily St. James of Vox wrote that Swift tells the stories of American millennials through her songs in the manner Springsteen represented American baby boomers.[61] Writers at Financial Times described her as one of "America's most successful cultural symbols".[8] Swift also metaphorically called herself as "Miss Americana" in her 2019 song "Miss Americana & the Heartbreak Prince",[62] which also inspired the namesake 2020 documentary about her life and career.[63]

Tributes and honorifics[edit]

Swift received various honorific titles and sobriquets recognizing her impact. "America's Sweetheart" is a title the media used for her in her early days, owing to her "all-American girl" image;[64][65] "Princess of Country" stemmed from her mainstream popularity as a country star.[66][67][68] Some outlets called her the "Pop Titan"[69][70] or "Queen of Pop" due to her pop music dominance.[71][72][73] Time and PopSugar used "Queen of Bridges" to appreciate Swift's ability to compose well-received bridges.[72][73] "Queen of Easter Eggs" was coined once Swift became known for the Easter eggs and clues embedded in her album cycles.[74][75][76][77] She was dubbed "The Music Industry" by Bloomberg Businessweek and American journalist Barbara Walters in light of her grip on the industry's fiber.[78][79][80]

In 2019, Swift became the first recipient of the Woman of the Decade (the 2010s) title from Billboard for being "one of the most accomplished musical artists of all time over the course of the 2010s",[81] and the American Music Awards named her Artist of the Decade for her record-setting wins in the 2010s.[82] In 2021, the Brit Awards awarded Swift the Global Icon trophy "in recognition of her immense impact on music across the world".[83] In 2022, the Nashville Songwriters Association International named her Songwriter of the Decade to acknowledge her success as a writer.[84][85] In 2023, she was presented the Innovator Award by iHeartRadio Music Awards for "her impact on global pop culture" and named Person of the Year by Time, the first time an entertainer received the designation in its 96-year history.[5][86]

Various objects and locations have been named after Swift. The Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville, Tennessee, established the Taylor Swift Education Center to host curriculum-connected activities for school groups, music programs, workshops and book talks.[87][88] Swift received an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degree from New York University in 2022 for being "one of the most prolific and celebrated artists of her generation".[89] She has two organisms named after her—Nannaria swiftae and Castianeira swiftay.[90][91] Botanists named a plant remote sensor TSWIFT (Tower Spectrometer on Wheels for Investigating Frequent Timeseries).[92][93]

Musicianship[edit]

Country music revival[edit]

Swift reshaped the 21st-century country music scene.[94] The country landscape is "much different today", according to Tom Roland of Billboard, due to Swift and her career decisions that several critics regarded "unorthodox".[37] Rosen described Swift as the first country act whose fame extended beyond the U.S. and marked internationally, as she offered "modernity, cosmopolitanism, youth" in a genre traditionally representing conservatism, parochialism and older adults.[22] Her chart success extended to Asia and the U.K., where country music had not been popular.[94][22] As of February 2011, Fearless sold 400,000 copies in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Indonesia and the Philippines.[95] Following her rise to fame, country record labels became interested in signing young singers capable of writing their own music.[96] In 2008, Sasha Frere-Jones of The New Yorker called Swift a "preternaturally skilled student of established values". Frere-Jones wrote, as the opening act for Rascal Flatts, Swift "[strutted] across stage platforms, performing a percussion duet on garbage cans, and switching gears without pause—her voice, all the while, light and breathy and without affectation—she returned the crowd's energy with the professionalism she has shown since the age of fourteen."[97] Rolling Stone said Swift's country music had a large impact on 2010s pop music.[98] The Country Music Association recognized Swift's "long-term positive impact on the appreciation of country music for generations to come" by awarding her with the second-ever Pinnacle Award in 2013.[99]

According to Roland, Swift insisted on writing her songs, mining inspiration from her real life. She entered country music, which has historically been "a place where adults sang grown-up songs for other adults".[37] With her autobiographical songs of romance and heartbreak, Swift introduced the country genre to a relatable younger generation.[22] Although the U.S. country radio's target audience was between ages 25 and 54, listeners were generally limited to those older than 35 years. Various country music acts, label executives, and radio programmers have unsuccessfully attempted to lower this median age since the early 1980s, but with Swift's rise in the mid to late 2000s the median age dropped below 25 with the genre attracting teenagers. According to programmer John Shomby, Swift "wrote for that specific age and was the first one to ever do that."[37]

Swift was one of the first country acts to employ internet as a marketing tool, promoting her music through MySpace, which was the largest social networking website in the world from 2005 to 2009.[100][101] She created her MySpace page the day before her then-label, Big Machine Records, was launched (August 31, 2005), and eventually amassed over 45 million streams via MySpace, which label CEO Scott Borchetta cited to convince "skeptical" country radio stations of Swift's niche audience. Social media followings and streaming service data have since been used "to prove an act's viability to radio".[37] Sisario credited Swift with widening the appeal of country music, introducing it to younger audiences, and contributing to country radio surpassing Top 40 as the largest format in the U.S.[102]

Poptimism[edit]

Journalists highlighted how Swift redefined the 21st-century pop music direction by expanding pop's perceived boundaries to bring forth emotional engagement and artistic ambition without forfeiting commercial success, defying critical beliefs. In 2013, Rosen described the Red-era Swift as a prim figure—"a rock critic's darling who hasn't the faintest whiff of countercultural cool about her", setting her apart from pop stars that followed the "raunchiness" trend of the period.[22] In 2016, Roland said Swift "managed to conquer country and, in an unprecedented move, transition fully into life as a pop artist with her latest album, 1989, without even a hiccup."[37] 1989's commercial success transformed Swift's image from a country singer to a full-fledged pop star.[103][104][105] Its singles received heavy rotation on U.S. radio over one and a half years following its release, which Billboard noted as "a kind of cultural omnipresence" that was rare for a 2010s album.[106]

Humanities academic Shaun Cullen described Swift as a figure "at the cutting edge of postmillennial pop".[107] Retrospectives from GQ's Jay Willis,[108] Vulture's Sasha Geffen,[109] and NME's Hannah Mylrea note how 1989 shunned hip hop and R&B crossover trends, influencing younger artists to explore "pure pop" and cultivating a trend of nostalgic 1980s-styled sound.[110] Ian Gormely of The Guardian deemed Swift a leading figure of 21st-century poptimism who replaced dance and urban trends with ambition. He wrote that her transition to pop proved "chart success and clarity of artistic vision aren't mutually exclusive ideas."[111] Geffen attributed Swift's pop transition success to her lyrics rooted in layered, emotional engagement rather than superficial themes that dominated mainstream pop.[109]

According to Lucy Harbron of Clash, pop stars like Dua Lipa would not exist if Swift had not normalized blending various pop music genres in 1989—an explicit trend among pop artists since the album.[112] It paved the way for artists "who no longer wish to be ghettoised into separated musical genres", for BBC's Neil Smith.[113] Critics Sam Sanders and Ann Powers regarded Swift as a "surprisingly successful composite of megawatt pop star and bedroom singer-songwriter" [114] while Philip Cosores of Uproxx felt Swift does not completely conform to either the traditional pop star or the "classic rocker" aesthetics, presenting a novel type of artistry.[115]

Genre heterogeneity[edit]

Swift has ventured into diverse genres and undertaken artistic reinventions throughout her career.[116][117] Pitchfork opined in 2021 that Swift changed the music landscape forever with a "singularly perceptive" catalog that accommodates musical and cultural shifts.[118] Harbron stated Swift's genre-spanning career encouraged her peers to experiment with diverse sounds.[112] The BBC and Time designated Swift a "music chameleon".[117][116] Swift stated that she "knew she had to keep innovating" to stay ahead of record labels working to replace her.[5]

Swift's fourth album Red (2012) intensified the critical debate over Swift's genre categorization, as she was a country artist at that time, but Red contained heavy pop, electronic and rock elements. Swift said that she opts to let others label genres.[119] Critics felt that Red signified Swift's inevitable transition to mainstream pop. Randall Roberts of Los Angeles Times claimed that Red is "perfectly rendered American popular music" irrespective of whether it is a pop or country record. The New York Times' Jon Caramanica dubbed Swift "a pop star in a country context".[120][121] According to Harbron, Red proved the industry that avant-garde is not the only experimental approach in music and that Swift "opened a door for every other musician" in 2012 to coalesce multiple genres into an album.[112]

Post-1989, Swift released her 2020 albums Folklore and Evermore, which were described as a mix of indie folk,[122][123] chamber pop,[124] and alternative rock styles.[125][126] They expanded the perception of Swift's discography, with many critics describing her catalog as a musically heterogeneous collection of songs.[31][127] Having demonstrated an emo appeal, Swift's songs are often covered by pop-punk and metalcore acts.[128] American singer-songwriter Noah Kahan said that Folklore and Evermore helped reignite popular interest in folk music,[129] and Billboard credited Swift with the power "to pull any sound she wants into mainstream orbit".[130][131]

Songwriting[edit]

Swift has a capacity for writing songs and lyrics that are very immediate, that tap into universal emotions and experiences, and that also play with her own public image, in a way that creates this self-perpetuating loop of interest and analysis of her music.

Nate Sloan, The Independent (2022)[132]

Swift is fundamentally a Nashville-enriched songwriter, "steeped in Music Row's values of craftsmanship and storytelling", as per Rosen.[22] Her songs are known for their passion and intense emotions.[23] According to Zoya Raza-Sheikh of The Independent, Swift is able to balance universal themes with hyper-specificity, possessing "an uncanny talent for reflecting the world's emotional angst through her own lens."[132] In being personal and vulnerable in her lyrics, music journalist Nick Catucci opined Swift helped make space for other singers like Ariana Grande, Halsey, and Billie Eilish to later do the same.[133] Professor Hannah Wing of Wichita State University attributed Swift's popularity to the intimacy in her music, cultivating a "feeling of closeness".[134] According to Scarlet Keys, songwriting professor at Berklee College of Music, Swift "mixes poetry with a very colloquial, current language", and frequently uses poetic devices but also knows to be "practical", such as in "Mean" (2011) or "Shake It Off" (2014).[20] Similarly, Sam Corbin of The New York Times described Swift as "a linguistic maverick, writing lyrics that toggle between mixed metaphor and catchy confessional."[135]

According to Raza-Sheikh, Fearless and Speak Now (2010) depicted Swift's adolescent innocence that resonated with a large audience, followed by her matured records Red and 1989, which exhibited her confidence in defining her narrative, becoming "unafraid of upsetting the status quo and critics"; she explored "the role of the villain" in her sixth studio album, Reputation (2017).[132] It was not until Folklore and Evermore some critics considered Swift's artistic credibility.[136] Commentators regarded both Folklore and Evermore as poetic reinventions, contextualizing them as "lockdown projects" or archetypal "quarantine albums".[137][138] Uproxx noted that Folklore changed the tone of music in 2020.[139] Critic Tom Hull wrote that Swift "caught the spirit of the times" with Folklore.[140] The New York Times and Vogue named Folklore one of the best moments of the "COVID era".[141][142] The rock critic Robert Christgau remarked that Swift's consistent artistic outputs made her an enduring songwriter, labelling himself a "longtime admirer of Swift".[143]

British scholar Jonathan Bate dubbed Swift a "real poet" with a "literary sensibility" evoking the likes of Emily Dickinson and Charlotte Brontë that was rare in pop music.[144] Stephanie Burt, an English professor at Harvard University, described Swift's songwriting skills as rare "at both the macro level of songwriting—presenting a story or an idea—as well as the micro level of fitting together vowels and consonants."[145] According to Andrew Unterberger of Billboard, Swift raised the "commercial ceiling" for singer-songwriters, benefitting artists such as Zach Bryan and SZA, who are primarily songwriters who emphasize personal themes.[10] Swift's songs have also helped non-native speakers, especially fans outside the Anglosphere, learn the English language.[146][147] She is Google's most searched songwriter of all time,[148] and the term "Swiftian" has been used in music journalism to describe works similar to or derivative of Swift.[149][150][151]

Commercial success[edit]

These numbers are especially improbable when you consider the music, and the musician, behind them. Swift is an oddball. There is no real historical precedent for her. Her path to stardom has defied the established patterns; she falls between genres, eras, demographics, paradigms, trends. She is a Pennsylvania Yankee turned teen-pop country singer, a Nashville star who crossed over to Top 40, a confessional singer-songwriter who masquerades as a global pop diva. Her music mashes up the quirkily homespun and the gleaming pop-industrial, Etsy and Amazon, in a way we've never quite heard before.

Jody Rosen on Swift's success, New York (2013)[22]

Swift has gained a reputation as a "perennial chart topper" as per Time.[152] Her discography has achieved huge commercial success across all formats and sectors. Rosen felt it was historically unprecedented—disproving the presumed notions of music's commercial success in the 21st century.[22][153] In the late 2010s, publications considered her million-selling albums a peculiarity in the streaming-dominated industry, as the end of the album era was marked by decline in album sales.[154][155] Hence, musicologists Mary Fogarty, Gina Arnold and Paul Théberge dub her an anomaly.[156][157] Following Swift's enduring success in the 2020s, The Atlantic opined that Swift's "reign" defies the convention that the prime of an artist's commercial success lasts for few years only,[158] whereas Rolling Stone considers her "a genre on her own", forming a major portion of total music consumption figures.[159]

Domestic[edit]

A highly successful artist on multiple Billboard charts, Swift has been credited with pushing the boundaries of commercial success.[131][158] She ranks eighth on Greatest of All Time Artists—a Billboard list ranking music acts based on chart success—as the only 21st-century act in the top 15.[160] Surpassing The Beatles and setting a new record, she is the longest-reigning act of the Billboard Artist 100 (100 weeks);[161] the soloist with the most cumulative weeks atop the Billboard 200 (68);[162] the woman with the most Billboard 200 number-ones (12),[163] Hot 100 entries (212),[164] Hot 100 top-10 entries (42),[165] and weeks atop the Top Country Albums chart (99);[166] and the act with the most Digital Songs number-ones (26),[167] the most number-one Pop Airplay songs (12),[168] and the longest song to top the Hot 100 ("All Too Well (10 Minute Version)").[169] Swift is the first and only act to monopolize the Hot 100's top 10 and place as the Billboard Year-End number-one artist in three different decades (2009, 2015 and 2023).[170][171]

Critics describe Swift's commercial power as unrivaled, as her success is evenly distributed across streaming, pure album sales, and track sales.[14] She is the only act in Luminate Data history to have six albums (or more than two albums)—Speak Now, Red, 1989, Reputation, Midnights, and 1989 (Taylor's Version)—sell over one million copies in one week.[172] To New York magazine, her sales figures prove she is "the one bending the music industry to her will".[155] Financial Times and I-D called Swift "the last pop superstar", given her ability to generate sales figures unseen since the "1990s boy bands" era, which was regarded as the commercial peak of the U.S. music business.[173][174]

International[edit]

The International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) named her Global Recording Artist of the Year in 2014, 2019, 2022 and 2023 for being the most consumed artist in those years; she is the only artist to achieve this three and four times.[175] Charlotte Kripps of The Independent said Swift led an international resurgence in country music, introducing the genre to a new U.K. audience.[176] Swift also became the first country act to find chart success beyond the Anglosphere. Rosen described her as the genre's "first truly global star", cultivating dedicated fandoms in foreign markets such as Ireland, Brazil, Taiwan,[22] and China,[177] where country music was not popular.[94][22] Jakarta, Quezon City and Singapore are among her biggest cities on streaming platforms.[178]

She holds several unique all-time chart feats in Australia, Ireland and the U.K.[179] In 2021, she became the first act to have three number-one albums on the U.K. Albums Chart in less than a year, besting the Beatles' 54-year-old record.[25][180] On Chinese music platforms, her albums are some of the best-selling of all time and have earned her the highest income for a foreign artist (RMB 159,000,000).[181] She was the world's highest-grossing female touring act of the 2010s.[182] According to Annabelle Heard, CEO of the Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA), "Swift has completely reset the narrative for what a solo artist can accomplish."[183]

Streaming[edit]

On Spotify, Swift is the most streamed artist of all time globally,[184] the only artist to have received more than 200 and 300 million streams in one day,[185][186] and the first female act to reach 100 million monthly listeners.[187] Swift's eleventh studio album The Tortured Poets Department is the most streamed album in a single day, with 315 million streams, and the first to collect one billion global streams in one week.[188][189] Variety dubbed Swift the "Queen of Stream".[190] Swift is also Apple Music's most streamed woman ever and set the platform's all-time record for most listeners for any artist in a single year.[191][192] The platform's vice president, Oliver Schusser, stated, "She is a generation-defining artist and a true change agent in the music industry, and there is no doubt that her impact and influence will be felt for years to come."[193]

Physical[edit]

Swift is noted for her vast CD and vinyl sales in the 21st century, when music consumption had largely shifted to digital formats.[156] Having driven the vinyl revival, she is regarded as a champion of independent record shops.[194][195][159] Swift has made LP variants of her albums available exclusively at small businesses, driving their sales; during the COVID-19 pandemic, she shared her LPs to record shops for free.[196][197] Due to her support of independent record shops, Record Store Day (RSD) named Swift their first-ever global ambassador.[196]

Evermore held the record for the biggest sales week for vinyl LPs in the U.S. since Luminate Data's inauguration in 1991, although it has since been surpassed by Swift's own Red (Taylor's Version) (2021) with 112,000 vinyl LP sales,[198] and Midnights with 575,000 LPs.[199] The latter is the first 21st-century album to sell over one million LPs in the U.S. and over 80,000 LPs in a year in the U.K.[200][201] 1989 (Taylor's Version) sold 1.014 million copies on vinyl in the U.S. in 2023, becoming the first vinyl album to sell one million copies in a calendar year since data tracking began, and Swift accounted for 7% of vinyl sales in 2023.[202] 1989 (Taylor's Version) also helped annual U.K. vinyl sales reach nearly six million copies, the highest in 33 years.[203] For the first time since 1992, the U.K. Office for National Statistics (ONS) designated vinyl records as one of the select goods and services in assessing the national cost of living and rate of inflation.[204] In 2023, Swift became the first artist to concurrently occupy the top three positions of the IFPI Global Vinyl Album Chart with her albums.[205]

Business acumen[edit]

"At 33 years old, pop star Taylor Swift is one of the world’s most influential business leaders. She has outmaneuvered music executives vying to control her song rights, sparred with tech giants and sold record numbers of albums. She secured her fans' loyalty by speaking directly to them online—before it was a marketing strategy."

— Anne Steele, "How to Succeed in Business Like Taylor Swift", The Wall Street Journal[206]

Swift established a reputation as a savvy businesswoman. Journalists often distinguish her as an "unparalleled marketing genius" with "high-minded business acumen" and an entrepreneurial role model.[207][208][209] According to Steele, Swift's "winding and winning" career presents management lessons beyond the music industry.[206] Economist Paul Krugman argued, "Being a congenital cynic, I'd like to attribute her fame to marketing hype, but the sad truth is that she's a highly talented songwriter and musician with remarkable stage presence."[210] In 2024, Billboard placed Swift atop its annual Power 100 list—a ranking of the most influential music industry executives.[211] Author Melinda Newman commented, Swift is an enduring force in the music business committed to innovation and risks that "reap remarkable rewards" for the rest of the industry.[212]

Name and brand[edit]

Various authors have compared Swift to media franchises, conglomerate companies or a one-woman brand. Knibbs and Elamin Abdelmahmoud described Swift as an omnipresent musical institution with economic, commercial and cultural consequences.[214][36] Labor economist Carolyn Sloan likened Swift to "a big corporation, essentially, operating in many sectors".[6] Her brand power has been compared to that of the DC Extended Universe and the Marvel Cinematic Universe.[207][173] According to Internet survey company QuestionPro, Swift's hypothetical net promoter score would make her the fourth most admired brand in the world.[215] CNN journalists have described the impact of her brand; Bryan Mena opined, Swift "didn't have to run a major company or helm a central bank to wield an immense economic power, and she has achieved remarkable feats that would be impressive for any typical business leader running a Fortune 500 company",[216] whereas Scottie Andrew remarked that news outlets and companies often use her name in headlines, interviews, branded content and products to capitalize off of her fame.[217]

Per Professor R. Polk Wagner at the University of Pennsylvania Law School, Swift associating her lyrics with a range of goods and services through trademark applications represents her understanding that "she is bigger than the music". He added, "It's more of a branding right, thinking of Taylor Swift as a conglomerate."[218] Additionally, in a practice called "domain squatting", Swift bought the pornographic website domain names "taylorswift.porn" and "taylorswift.adult" to prevent them from being misused.[219]

Social media presence[edit]

Swift, one of the most followed people on social network services, is a "social media powerhouse", according to Entrepreneur.[208] She was the most followed person on Instagram from September 2015 to March 2016,[220][221] and has consistently been influential on Twitter, placing first in Brandwatch's annual rankings three times.[b] The Washington Post additionally noted, "Swift is one of few foreign celebrities who have gained more than 10 million followers on Weibo, China's answer to Twitter".[177] Ticketing executive Nathan Hubbard said that Swift was the first musician "to be natively online."[9] Culture critic Brittany Spanos opined that Swift's social media presence is one of the reasons she is still "really relevant" after years: Swift "grew her fan base on Myspace. She was using Tumblr way past its prime. Twitter. She's now on TikTok, commenting on people's videos."[225]

Swift's marketing is a combination of social media engagement and television. Cision called Swift a "master of product launch", with knowledge of "a strategic and well-balanced communications campaign". According to public relations (PR) academic Sinead Norenius-Raniere, Swift's integrated marketing strategy consists of timed announcements across marketing channels, harnessing the potential of both traditional and digital media, authentic and "intimate" communications with consumers to build trust, and usage of multimedia to offer "sneak peeks".[226] Billboard attributed Swift's "enduring relevance" in part to how she "understands her audience" and employs campaigns that "don't neatly fit industry narratives".[131] Her novel promotional efforts, such as Midnights Mayhem with Me, were a subject of critical praise for innovation.[227][207] Bond Benton, an associate professor in communication and media at Montclair State University said "there is a memetic quality to the way Swift is presented online", which has since been repurposed by other celebrities to increase their engagement.[40]

Album cycles[edit]

Swift is known for her traditional, conceptual album rollouts, often referred to as "eras", each of which consists of a variety of promotional activities.[228][229][230] Rolling Stone described her eras as an inescapable "multimedia bonanza".[231] She is credited with making the "two-year album cycle" approach of releasing and promoting albums the industry standard and helped popularize the term and concept of "eras" in broader media contexts.[37][232][233] Nevertheless, journalists also praised Swift's fast-succeeding release of Evermore less than five months after Folklore. Variety compared it to similar moves by the Beatles and U2,[234] while Rolling Stone found it reminiscent of Prince in 1987 and David Bowie in 1977.[235]

Easter eggs and cryptic teasers similar to Swift's became a common practice in pop music.[236] Publications describe her discography as a music "universe" subject to analyses by fans, critics and journalists.[237][238][11] Swift's outfits, accessories, diction, color coding, numerology, and elaborate album packaging have also been Easter eggs.[207][239][131] El País critic Iker Seisdodos called her "a master of the art of suspense".[20] According to journalist Ashley Lutz, her marketing style is "an ever-changing burlesque act of selectively revealing details while maintaining an aura of mystery and excitement"—a strategy that goes beyond the music and entertainment industries.[207]

Each of Swift's eras is characterized by a unique aesthetic, color palette, fashion style,[240][241] and an associated mood or emotion.[242] The Conversation described her album releases as cultural moments.[243] Reinventing her image and style throughout her career, Swift has popularized several aesthetic trends, such as Polaroid motifs with 1989,[244] and cottagecore with Folklore and Evermore.[245] Lutz opined that the era shifts helped broaden her fan base and critical appeal.[207] Pop culture commentator Jeetendr Sehdev asserted Swift has managed to remain interesting by constantly reinventing herself "while remaining authentic".[207] However, in a counterview, Fairclough claimed that Swift's "shifting aesthetic" indicates her struggle with a lack of identity.[34]

Corporate relations[edit]

Swift embraces corporate sponsors. Her marketing incorporates strategic business partnerships with companies, which were once regarded as a "taboo" among musicians.[246] Marketing expert Christopher Ming wrote, "Sure, working with brands like Apple Music, Elizabeth Arden, and Diet Coke feel like no-brainers. But it takes a certain amount of marketing ingenuity to make campaigns with NCAA Football, United Postal Service [sic], and Papa John's work. Yet they all did."[207] Swift promoted Red (Taylor's Version) and 1989 (Taylor's Version) using Starbucks and Google Search, respectively.[247][248] Journalists stated that the impact of her album releases is "felt across social media", with brands and companies often endorsing her to capitalize on her "momentum", leveraging her cultural relevance.[249][50][250]

Industry and economy[edit]

The economic impact of Swift's career has been termed as Swiftonomics.[251] Abrdn's Bred Wilhite considers Swiftonomics a branch of economics that deals with the intersection of consumer emotions and capitalism.[252] Economists and industry academics have studied Swift's macroeconomic influence on businesses worldwide, comparing her to countries. According to trade publication Pollstar, if Swift were a country, she would be the 199th largest economy on earth, analogous to a small Caribbean nation.[253] Katie Atkinson of Billboard equated Swift's 2023 earnings (an estimated $2 billion) to the gross domestic product (GDP) of East Timor.[254] QuestionPro estimated her 2023 economy at $5 billion, higher than the GDP of 50 countries.[215] Swift's name and presence has a microeconomic impact as well, benefitting various small businesses.[255] MarketWatch termed Swift's influence on markets as "the Taylor Swift stock-market effect".[256]

Swift's tours are channels of "economic enrichment".[258] According to author Peggy Noonan, Swift altered "the rules of entertainment economics".[60] Analyses of her economic impact includes studying the "booming" economy around her concert tours, which escalates travel, lodging, cosmetic, fashion, and food businesses,[259] and tourism revenues of cities by millions of dollars.[260][261][262] After the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused a global economic recession, the unprecedented ticket sales of the Eras Tour represented a "post-COVID demand shock in the U.S.", as per Bloomberg L.P. correspondent Augusta Saraiva.[263]

Challenging industry norms[edit]

Swift has been instrumental in reforming the business aspects of music,[264] often considered a flag-bearer for artists' rights. Journalists praise her ability to question industry practices, noting how her moves changed streaming platform policies, prompted awareness of intellectual property among upcoming musicians, reshaped the concert ticket model,[14][265] and negotiated better financial compensations from labels for all music artists.[266] Elle described the Swift-enabled reforms to streaming services as "a milestone moment in the history of music".[25]

Streaming reforms[edit]

Swift contested music streaming services to regulate corporate policies for better preservation of artistic integrity.[25][267] She said digital streaming services have become a dominant form of media consumption since 2013, causing a gradual decline in traditional album sales.[268][269] In November 2014, Swift announced that 1989, her then-upcoming album, would not be released on Spotify, which was growing in popularity at the time, in protest of the platform's "minuscule" payment to artists (US$0.006 to 0.0084 per stream). In an op-ed for The Wall Street Journal, she expressed her belief that the value of works of art should be fixed by artists:[268]

"Music is art, and art is important and rare. Important, rare things are valuable. Valuable things should be paid for. It's my opinion that music should not be free, and my prediction is that individual artists and their labels will someday decide what an album's price point is. I hope they don't underestimate themselves or undervalue their art."

Karim R. Lakhani and Marco Iansiti, business administration professors at Harvard Business School, reviewed the issue and upheld Swift's belief that musicians should set the prices.[270] For academic Jessica Searle, Swift proposed music as a "non public good".[271] Nilay Patel, writing for Vox, criticized Swift's beliefs about albums and said she "doesn't understand supply and demand"; Patel stated that the internet has "killed" the album format, claiming most consumers would not shop for a Swift CD anymore.[272] Eventually, Swift withdrew her entire discography from Spotify, prompting it to say "We hope she'll change her mind and join us in building a new music economy that works for everyone."[268] 1989 was a commercial success upon release, and another Vox journalist Constance Grady regarded this a "major blow" for Spotify, which attempted to bring Swift back by releasing playlists dedicated to Swift. Her music stayed off Spotify for nearly three years, until Swift released it back on June 9, 2017, in celebration of Swift's milestone 100 million certified units from the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA).[273] Spotify CEO Daniel Ek stated on CBS This Morning that he convinced Swift to bring her music back on Spotify by meeting her in Nashville, "explaining the model, why streaming mattered", and how her fans want her music back on Spotify.[274]

In June 2015, Swift wrote an open letter to Apple Inc. on Tumblr, addressing the three-month free trial that Apple Music had chosen to offer their users while not paying the artists whose catalogs are streamed by users during the trial period. Swift said she finds it "shocking" that they had opted not to pay "writers, producers, or artists" for the three months. She explained:[275]

"This is not about me. This is about the new artist or band that has just released their first single and will not be paid for its success. This is about the young songwriter who just got his or her first cut and thought that the royalties from that would get them out of debt. This is about the producer who works tirelessly to innovate and create, just like the innovators and creators at Apple are pioneering in their field...but will not get paid for a quarter of a year's worth of plays on his or her songs. ... Three months is a long time to go unpaid, and it is unfair to ask anyone to work for nothing. We don't ask you for free iPhones. Please don't ask us to provide you with our music for no compensation."

Swift asserted 1989 would not be on Apple Music either and urged the company to change the policy before its launch on June 30, 2015.[275] Eddy Cue, an Apple executive, apologized and promised to reverse the policy.[276] Cue told Associated Press, "When I woke up this morning and I saw Taylor's note that she had written, it solidified that we needed to make a change."[277] When Apple Music officially launched, it paid royalties to artists during the three-month trial.[267] Various musicians, music organizations and industry commentators expressed their gratitude to Swift.[277]

Following the expiration of her six-album Big Machine contract in 2018, Swift signed a new global contract with Republic Records, a label owned by Universal Music Group.[278] She revealed that, as part of the contract, any sale of Universal's shares in Spotify would result in non-recoupable equity shares for all Universal artists.[279] Grady called it a huge promise from Universal "far from assured" until Swift interceded.[280] Financial Times's Jamie Powell said, "Swift, on her own, is as powerful as an entire union", and dubbed the equity negotiation "Comrade Swift's special dividend".[281] Yang opined that it demonstrated "the full weight of Swift's power: In an unprecedented move that seals her status as a kind of joan of arc for creator rights".[282] In 2023, American businessman Elon Musk asked Swift to release her music or concert videos directly to Twitter; highlighting the pleas of Ek, Cue and Musk, Fast Company opined Swift is "arguably the most powerful person in tech".[283]

Intellectual property[edit]

Swift's "battle" against exploitative recording contracts for the ownership of her masters has been described as "revolutionary".[25] In June 2019, after Swift moved to Republic Records, Braun acquired Big Machine for $330 million, making him the owner of all the Big Machine masters, including those of Swift's first six studio albums. Swift responded she attempted to purchase the masters but was offered unfavorable conditions, while Borchetta claimed she declined a chance to purchase them.[284] Swift alleged the label blocked her from performing her music at the 2019 American Music Awards,[285] and claimed Borchetta and Braun were "exercising tyrannical control" over her.[286] Big Machine then released Live from Clear Channel Stripped 2008 (2020), an unreleased live album by Swift, without due diligence.[287] The controversy was highly publicized, becoming one of the most widely discussed and covered news topics of 2020 and 2021.[288] Evening Standard called it "music's biggest feud".[289]

Re-recording the albums was the only viable option to gain full ownership of her music, as per Swift. Braun sold the masters in October 2020 to Shamrock Holdings for $405 million under the condition he would continue profiting.[290] Swift disapproved again, rejected a Shamrock offer for equity partnership, and began releasing the re-recordings via Republic.[291] The re-recorded albums were met with critical and commercial success, breaking multiple commercial records.[292][293] When "All Too Well (10 Minute Version)" became the longest song ever to top the Hot 100, Jack Antonoff, the song's producer and a frequent collaborator of Swift, told Rolling Stone that a 10-minute-long song topping the Hot 100 teaches artists to "not listen" to what the industry has to say.[294]

Numerous music artists, politicians, journalists and legal experts supported Swift's actions regarding the issue, deeming it trailblazing and inspirational.[286][295] Publications observed, while the issue of master ownership and conflicts between labels and artists such as Prince, the Beatles, Janet Jackson, and Def Leppard have been prevalent earlier, Swift was one of the few to make it a public discourse on artists' rights, private equity and industry ethics.[296][297][213][298] Dubbing the dispute one of the 50 "most important moments" of the 2010s decade,[299] Rolling Stone journalists noted Swift's role in shifting the public perception of the concept of re-recording or re-mastering.[300] Dominic Rushe of The Guardian said Swift's battle marked a change in the digital music era, with artists more aware of their rights without the need to rely on record labels anymore.[298] Pitchfork critic Sam Sodomsky recognized the visibility she brought, saying Swift "can enact change by wielding the leverage of the reliability of her success" and that it is "financially lucrative for the industry to listen" when she speaks.[213]

Unlike most artists when faced with this kind of injustice, Swift could stand up for herself, and in doing so, invoke meaningful dialogue and inspire change within the notoriously slow-moving music industry ... Re-recording a back catalog of six full albums and respective secret bonus tracks, then developing a hugely successful campaign to drive loyal fans towards the new versions of their beloved albums—and away from the original master recordings, prompting a dip in streams that will be mimicked in the rights holders' income statement—is something only very, very few artists can do. Taylor Swift is, indeed, amongst that handful.

— Eilish Gilligan, "Taylor Swift's Re-Recordings Expose The Music Industry's Chokehold On Intellectual Property", Refinery29[301]

The A.V. Club and MarketWatch interpreted Swift's statements as a criticism of private equity, highlighting The Carlyle Group, one of Braun's investors.[302] U.S. Congress members like Elizabeth Warren and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez backed Swift and stated that she is "one of many" creative businesses threatened by private equity firms that harm the U.S. economy.[303][304] Music attorney James Sammataro observed that "any time Taylor brings attention to an issue, it gets magnified ... She has a very loud megaphone and she's not afraid to use it. She's had great success in effectuating change."[305] The outcomes of the re-recording venture have been described as unprecedented.[292] Kornhaber opined that the re-recordings disproved critics who doubted Swift.[306]

Distribution models[edit]

The concert industry shifted to a "slow ticketing model" after Swift, who is known for her stadium concerts and commercial "dominance of the touring industry",[307][308] first implemented it with the Reputation Stadium Tour (2018). It replaced the selling-out of tickets in minutes with a demand-driven ticketing approach that requires consumers to register in advance and allowed them to purchase tickets at any time and price level upon access. This meant higher ticket prices in the beginning and a gradual drop as the concert date approached, replacing "momentum with consumer choice and experience" and bypassing scalpers, according to David Marcus of Ticketmaster. The model was initially criticized by journalists, who thought it was an attempt at camouflaging Swift's dull ticket sales following her unfavorable press in 2016; however, the tour was a sold-out success, surpassing the Beatles to become the highest grossing North American tour of all time, after which critics favored the model.[309][310][311]

In November 2022, the pre-sale of the U.S. leg of the Eras Tour was mismanaged by Ticketmaster, attracting widespread public and political criticism. Due to the "astronomical" demand for tickets,[312] with 3.5 million people registering for the on-sale program, the Ticketmaster website crashed within an hour of sale but still sold 2.4 million tickets, breaking the record for the most concert tickets sold by an artist in a single day. Ticketmaster attributed the crash to "historically unprecedented" site traffic.[313][314] Fans and consumer groups accused Ticketmaster of deceit and monopoly.[315] Several members of U.S. Congress claimed that Ticketmaster and its parent company Live Nation Entertainment should be separated as their merger led to substandard service and higher ticket prices.[316] The U.S. Department of Justice opened investigations into Live Nation–Ticketmaster,[317] whereas several fans sued the companies for intentional deception, fraud, price fixing, and antitrust law violations.[318] Bipartisan members of the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee censured the companies at a hearing.[319] Under pressure from the National Economic Council, Ticketmaster and other ticketing companies agreed to terminate junk fees—additional fees revealed at the end of ticket purchases. American legal scholar William Kovacic termed it the "Taylor Swift policy adjustment."[320] For the 2023 concert film of the tour, Swift adopted an unconventional release strategy that directly partnered with movie theaters to bypass the major film studios.[321]

Pitchfork asked, "Is there any other artist [other than Swift] who could force urgency into the federal investigation of a music industry monopoly just by going on tour?"[322] Entertainment Weekly and The A.V. Club listed "Swifties vs. Ticketmaster" as one of the biggest cultural news stories of 2022. The former's Allaire Nuss wrote, "If there was ever an artist with enough pop-culture prowess to bring down the music industry's most hated monopoly, it's Taylor Swift."[323][324] The Washington Post proclaimed Swift has "an unbreakable hold on our increasingly fractured world—and its discourse—in a way that almost no one else can."[11]

Media, fashion, and politics[edit]

Swift is widely covered in mass media, which has generated a range of public perceptions of her. She and her music have been referenced or used in numerous books,[325] films, and television shows.[326] A subject of incessant scrutiny in the press,[327] her relationship with the mainstream media has been described by critics as an example of the celebrity–industrial complex.[328] Swift is considered "polarizing", receiving both favorable and unfavorable press throughout her career.[329][330]

She is regarded as a feminist figure.[25] She has criticized the way media depicts women,[331] as her dating life and disputes have attracted tabloid scrutiny and widespread online attention.[332][333][334][335] She has been vocal about the impact of press coverage on personal health, discussing issues such as eating disorders, self-esteem, and cyberbullying; various academics and journalists have opined that Swift's openness regarding these topics are crucial for raising mental health awareness.[336][337][338]

Additionally, Swift is often dubbed a millennial cultural figure,[339][340][341] as well as a fashion influencer. The evolution of her style has been the subject of media coverage and analysis.[342][264] She has reinvented her image and aesthetic throughout her career, matching respective album cycles with distinct themes, impacting fashion trends in the process. Her street style, in particular, has received acclaim.[240][241]

Authors regard Swift as the most powerful music personality in American politics.[343] Having used her fame to incite political action,[16] Swift was the second most influential celebrity in Joe Biden's win in the 2020 U.S. presidential election, after LeBron James.[344] Various surveys have deemed her a deciding factor in elections, one that can bridge the polarization in American politics.[345][346][347] Swift has inspired a number of legislative proposals and laws.[348][349][350][351]

Creative inspiration[edit]

Swift has influenced numerous music artists across genres since her debut.[128] Critics began noticing her influence on popular music in 2013,[22] and credit her albums with inspiring an entire generation of singer-songwriters.[37][122][352] Paul McCartney was inspired by Swift's artistry and fans to write the 2018 song "Who Cares".[353] Other acts who cited Swift as an influence include:

- 5 Seconds of Summer[354]

- Gracie Abrams[355]

- Adele[356]

- Baby Queen[355]

- Bahjat[357]

- Kelsea Ballerini[358]

- Priscilla Block[359]

- Phoebe Bridgers[355]

- Bailey Bryan[360]

- Camila Cabello[361]

- Sabrina Carpenter[362]

- Sofia Carson[363]

- The Chainsmokers[364]

- Clairo[355]

- Gus Dapperton[355]

- Daya[365]

- Billie Eilish[366]

- Ellis[367]

- Fletcher[368]

- Gayle[355]

- Girl in Red[369]

- Selena Gomez[370]

- Ellie Goulding[371]

- Mckenna Grace[372]

- Conan Gray[355]

- Loren Gray[373]

- Griff[355]

- Halsey[374]

- Maya Hawke[375]

- Niall Horan[376]

- Huh Yun-jin[377]

- Lilas Ikuta[378]

- Jax[379]

- Ruston Kelly[367]

- Kim Chae-won[380]

- Laufey[381]

- Little Mix[382]

- Atsuko Maeda[383]

- Catherine McGrath[356]

- Tate McRae[384]

- Shawn Mendes[385]

- Maren Morris[386]

- The National[387]

- Nina Nesbitt[388]

- Niki[389]

- Finneas O'Connell[390]

- Christina Perri[391]

- Maisie Peters[355]

- The Regrettes[392]

- Renforshort[132]

- Freya Ridings[393]

- Olivia Rodrigo[355]

- Maggie Rogers[394]

- Ruann[395]

- Ruth B.[396]

- Rina Sawayama[397]

- Shamir[367]

- Troye Sivan[355]

- Slayyyter[398]

- Soccer Mommy[399]

- Hailee Steinfeld[400]

- Tegan and Sara[401]

- Tzuyu[402]

- The Vamps[403]

- Hana Vu[367]

- Wild Pink[367]

- Hayley Williams[404]

Various musicians were inspired by aspects of Swift's career, such as her work ethic and appeal. Swift's comments on artists' rights influenced Bryan Adams,[405] Ashanti,[406] the Departed,[407] Snoop Dogg,[408] Paris Hilton,[409] Joe Jonas,[410] Zara Larsson,[411] Niki,[412] Offset,[413] Rita Ora,[414] Rodrigo,[415] and SZA.[416] Ashanti commented, "Taylor is amazing for what she's done and to be able to be a female in this very male-dominated industry, to accomplish that is amazing. Owning your property and getting a chance to have ownership of your creativity is so so important. Male, female, singer, rapper, whatever, I hope this is a lesson for artists to get in there and own."[406] SZA said, "Taylor letting that whole situation go with her masters, then selling all of those fucking records. That's the biggest 'fuck you' to the establishment I've ever seen in my life, and I deeply applaud that shit."[416]

Swift has also helped artists achieve mainstream fame by inviting them on her tours as opening acts, such as Ed Sheeran, Mendes, Cabello, and Charli XCX.[417] Filipino-British singer Beabadoobee, an opening act on the Eras Tour, stated that touring with Swift was one of her dreams growing up.[418] American musicians Jack Antonoff and Aaron Dessner acknowledged Swift's role in expanding their careers as record producers. Antonoff stated, "Taylor's the first person who let me produce a song. Before Taylor, everyone said: 'You're not a producer'. It took Taylor Swift to say: 'I like the way this sounds'."[419][420] Swift helped American rapper Kendrick Lamar garner his first-ever number-one song on the Billboard Hot 100 with "Bad Blood" (2015), whereas Trinidadian rapper Nicki Minaj credited Swift, who had promoted Minaj's 2011 single "Super Bass", with the song's unanticipated success.[421][422]

Outside the music industry, Swift has inspired authors, novelists,[423] film directors, and screenwriters, including Sina Grace (Superman: The Harvests of Youth),[424] Jenny Han (The Summer I Turned Pretty),[425] Abby McDonald (Bridgerton),[426] and Jennifer Kaytin Robinson (Someone Great[427] and Do Revenge).[428] Canadian film director Shawn Levy described Swift as "a culture magnet unlike anything I've seen".[429] Mexican filmmaker Guillermo del Toro opined, Swift is "a very accomplished director, she's incredibly articulate and deep about what she's trying to do—and what she will do."[430] Swift has also inspired impersonators such as Ashley Leechin,[431] Jade Jolie,[432] and Taylor Sheesh.[433]

Fandom[edit]

Swift's close connection with her fans, Swifties, is considered unique for artists of her stature.[434][435] Swifties have been described as a loyal fanbase with high levels of participation and creativity.[264] Author Amanda Petrusich described Swifties' allegiance as both "mighty and frightening".[436] The fandom has been the subject of journalistic and academic interest;[437] critical analysis of Swift is referred to as "Swiftology" in the media.[438][439] To business scientists Brendan Canavan and Claire McCamley, the relationship between Swift and Swifties represents post-postmodern consumerism.[440] The fan frenzy, generally termed "Swiftmania",[441] has been considered the 21st-century equivalent to Beatlemania by journalists such as Jon Bream of Star Tribune, who said "Swift has achieved a once unthinkable monoculture, a zeitgeistian redux of Beatlemania".[26][30]

As Swift has been a source of myth in popular culture, journalists describe her works, celebrity, and the fanfare surrounding them as a world on its own. Glamour and The Washington Post termed it the Taylor Swift Cinematic Universe;[11][237] Entertainment Weekly called it Taylor Swift Musical Universe.[238] In The Guardian, Adrian Horton said "Swiftverse" is a subculture of mass media cultivated by "years of worldbuilding and Swiftian mythology",[239] while Alim Kheraj and Billboard wrote that Swift turned pop music into a "multiplayer puzzle" with a fanbase commitment that other artists have subsequently attempted to reproduce.[442][308]

Cross-cultural effect[edit]

In attempting to define and analyze Swift's impact on various fields, a number of publications have contextualized it to what they generally termed the "Taylor Swift effect". Marcus Collins, professor of marketing at the University of Michigan Ross School of Business, described the effect as a network effect. He said that Swift's stature is "such that when she does something people follow [...] She's influencing a group of people and those people are influencing each other and other people. There's a network effect that's at play." Chris Bibey, in Yahoo! Finance, opined the Taylor Swift effect "could have an impact on your future business and investing endeavors" irrespective of one's own interest in Swift.[443] Various phenomena have been attributed to the effect, such as:

- The upsurge in guitar sales to women, a previously ignored demographic, following Swift's image as a female guitarist and her affinity for guitar in her performances.[444][445][446]

- The record-setting voter registrations reported whenever Swift encouraged her followers to register as voters via social media.[447][448][449]

- The consumerist phenomenon of purchasing any product or service related even peripherally to Swift.[450]

- The increased legal attention towards the machinery of the music industry and recording contracts.[451][452]

- The economic enrichment or "wide financial halo", in the words of Forbes, that Swift casts on places she visits on tour,[6][453] and the open requests from politicians and heads of government to Swift, asking her to tour territories under their jurisdiction.[5]

- The significant increase in viewership and brand value that media franchises, television programs and sports organizations, enjoy following Swift's engagement with them.[454][455][456][457]

- The string of law bills passed or drafted by legislatures, inspired by Swift.[458][459]

- The vinyl revival in the 2020s decade.[204]

According to Time's Sam Lansky, the "real" Taylor Swift effect is psychological. It has influenced people, especially women who have been "conditioned to accept dismissal, gaslighting, and mistreatment from a society that treats their emotions as inconsequential", to believe that their emotions and perceptions matter.[5] Kyle Chayka of The New Yorker coined the term "Swiftularity" to refer to Swift's "inescapability" in all facets of popular culture. Chayka opined that Swiftularity is a media funnel, "siphoning [the public] toward an increasingly narrow set of subjects", wherein contemporaneous objects or topics in popular culture become part of Swift's influence one by one, ranging from politics and sports to technology like artificial intelligence (AI).[41]

Scholarly interest[edit]

Swift is a subject of academic research.[132][460] Her artistry, fame, entrepreneurship and societal impact are broadly the topics of scholarly media studies.[31][461][462] According to literature professor Elizabeth Scala, who dubbed Swift a bridge between contemporary and historical fiction, Swift's creativity is "contagious" and of particular interest to academics.[132] In The New York Times article "Taylor Swift is Singing Us Back to Nature", conservation scientist Jeff Opperman opined that Swift's songs are "filled with the language and images of the natural world", revitalizing themes of nature in popular culture after a reported decline in nature-themed words.[463] "Love Story" (2008) is amongst the songs studied by evolutionary psychologists to understand the relationship between popular music and human mating strategies.[464][465] In explaining why Swift has become a subject of academic study, literary scholar Burt stated, "humanities ought to study culture, including the culture of the present day, and Taylor Swift is all over that culture" and claimed that future historians and anthropologists will study Swift's art, fame and reception to understand the contemporaneous society and deduce cross-cultural patterns.[1]

Academic programs[edit]

Various higher educational institutions offer undergraduate and elective courses focusing on Swift.[264][31][466] Many of the courses employ a dissection of Swift's work as "an entry point into criticism, analysis, and broader cultural issues and touchstones."[467][468] To examine Swift's multifaceted impact, Indiana University Bloomington had a three-day academic conference in 2023.[460] In 2024, the University of Melbourne hosted the "Swiftposium", an international symposium organized by scholars from 78 Australian and New Zealand institutes, timed alongside the Eras Tour.[469][470] Organizers stated that the conference was more academic than fan-oriented with a fair amount of criticism among the approximately 400 papers submitted.[471]

| Institution | Course title(s) | Course description(s) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona State University | Psychology of Taylor Swift | Phenomena such as gossip, relationships, and revenge through Swift's work and life | [472] |

| Austin Peay State University | The Invisible String of Romanticism | Poeticism of Swift's songwriting alongside Romantic poets like William Wordsworth | [473] |

| Berklee College of Music | Songs of Taylor Swift | Swift's compositions, lyricism, global appeal, and musical evolution across her 10 albums | [474] |

| Binghamton University | Taylor Swift, 21C Music | Impact of the 21st-century music industry on Swift's music evolution, gender, race, sexuality, and business | [475] |

| Brigham Young University | Miss Americana: Taylor Swift, Ethics and Political Society | Ethical analysis of themes in Swift's music | [476] |

| Ghent University | Literature: Taylor's Version | Critical analysis of Swift's writing techniques, styles and themes against classical English literature | [477] |

| Harvard University | Taylor Swift and Her World | Literary and aesthetic analysis of Swift's music, lyrics, influence and artistry in the context of American art, culture and literature | [478] |

| New York University Tisch School of the Arts | Swiftology 101 | Swift's creative music entrepreneurship, legacy, image, genres, fandom, and analyses of youth, girlhood, race, ownership, American nationalism, and social media | [479] |

| Northeastern University | Speak Now: Gender & Storytelling in Taylor Swift's Eras | The impact of women's literary and cultural contributions to genre and narrative on the artistry of Swift's ten musical eras | [480] |

| Queen Mary University of London | Taylor Swift and Literature | Swift's lyricism as literature, its canonicity, literary value, and critical theory in political, national, and historical contexts. | [481] |

| Queen's University at Kingston | Taylor Swift's Literary Legacy | Swift's sociopolitical impact on contemporary culture, the recontextualization of her songs as literature, and exploration of her work within feminist and queer theory | [482] |

| Rice University | Miss Americana: The Evolution and Lyrics of Taylor Swift | Swift's cultural impact, songwriting evolution, femininity, social media, public opinion, whiteness, and feud | [483] |

| St. Thomas University (Canada) | Communications and Taylor Swift | Swift's marketing, communication strategies, and use of social media | [484] |

| Stanford University | All Too Well (Ten Week Version) | In-depth analysis of "All Too Well" | [485] |

| The Last Great American Songwriter: Storytelling With Taylor Swift Through the Eras | Literary analysis of Swift's repertoire, lyrical evolution, and cultural impact | [486] | |

| University of California, Berkeley | Artistry and Entrepreneurship: Taylor's Version | Swift as a songwriter, business woman and creative influence, and her impact on literature, economics, business and sociology | [487] |

| University of Florida | Musical storytelling with Taylor Swift and other iconic female artists | Investigation of the storytelling in songs by female artists such as Aretha Franklin, Billie Holiday, and Dolly Parton, with emphasis on Swift | [467] |

| University of Houston | The Entrepreneurial Genius of Taylor Swift | Swift's entrepreneurship, marketing, fan engagement, community building and branding strategies | [488] |

| University of Kansas | The Sociology of Taylor Swift | Swift's fans as a community of interest and subculture | [489] |

| University of Miami School of Law | Intellectual Property Law Through the Lens of Taylor Swift | Swift's re-recorded albums, trademarks, copyrights, contracts, lawsuits, privacy and other legal issues. | [490] |

| University of Missouri | Taylor Swiftory: History & Literature Through Taylor Swift | Swift as a historical literary source | [491] |

| University of the Philippines | Celebrity Studies: Taylor Swift in Focus | Swift's celebrity and its impact on the relationships between the public, media, class, politics, gender, race, and success. | [492] |

| University of South Carolina | Life is Just a Classroom: Taylor's Version | Swift's business aspects, such as her economic impact, ticket sales, merchandise, philanthropy, fandom, and corporate sponsorships | [473] |

| University of South Dakota | The Taylor Swift Effect | Intersection of Swift and the law, such as her re-recorded albums and copyright issues | [451] |

| University of Texas at Austin College of Liberal Arts | The Taylor Swift Songbook | Formalist literary criticism of Swift's songs alongside poets such as William Shakespeare, John Keats, Robert Frost, Emily Dickinson and Sylvia Plath | [493] |

Footnotes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Burt, Stephanie (December 29, 2023). "Taylor Swift at Harvard". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on January 8, 2024. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ^ a b Cartwright, Lexie (November 18, 2023). "How Taylor Swift went from pop celebrity to most famous person on the planet". News.com.au. Archived from the original on November 19, 2023. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ^ a b Dunn, Billie (December 13, 2023). "Taylor Swift Breaks Astonishing Record". Newsweek. Archived from the original on December 23, 2023. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ^ a b Jericho, Greg (October 28, 2022). "Taylor Swift's incredible success in graphs – who can blame me for being a Swiftie as a 50-year-old man?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 28, 2022. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Lansky, Sam (December 6, 2023). "Taylor Swift Is TIME's 2023 Person of the Year". Time. Archived from the original on December 8, 2023. Retrieved December 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c McGrath, Maggie. "Taylor Swift's Power Era: Why The Billionaire Pop Star Is One Of The World's Most Powerful Women". Forbes. Archived from the original on December 20, 2023. Retrieved December 5, 2023.

- ^ a b Molanphy, Chris (November 4, 2022). "How Taylor Swift Achieved the Unthinkable". Slate. Archived from the original on November 5, 2022. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Politi, James; Chavez, Steff (February 1, 2024). "Taylor Swift becomes a target in the US election culture wars". Financial Times. Archived from the original on January 31, 2024. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ a b c Ben, Sisario (August 5, 2023). "How Taylor Swift's Eras Tour Conquered the World". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 5, 2023. Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Unterberger, Andrew (December 15, 2023). "Billboard's Greatest Pop Stars of 2023: No. 1 — Taylor Swift". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 15, 2023. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Yahr, Emily (December 26, 2022). "2022: The year in review (Taylor's version)". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 26, 2022. Retrieved December 26, 2022.

- ^ a b Yang, Jeff (December 2, 2023). "Opinion: How Taylor Swift conquered capitalism". CNN. Archived from the original on December 23, 2023. Retrieved December 2, 2023.

- ^ a b "Cover Trail: Taylor Swift Is the Music Industry". Bloomberg Businessweek. November 13, 2014. Archived from the original on August 28, 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c Schneider, Marc (July 24, 2023). "8 Ways Taylor Swift Has Changed the Music Business". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 24, 2023. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ^ a b "Taylor Swift's 40 Biggest Hot 100 Hits". Billboard. March 23, 2022. Archived from the original on December 14, 2022. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ^ a b "2023 America's Self-Made Women Net Worth — Taylor Swift". Forbes. June 1, 2023. Archived from the original on January 10, 2011. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- ^ Pendleton, Devon; Ballentine, Claire; Patino, Marie; Whiteaker, Chloe; Li, Diana (October 26, 2023). "Taylor Swift Vaults Into Billionaire Ranks With Blockbuster Eras Tour". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on October 26, 2023. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- ^ "Taylor Swift Albums and Discography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on May 14, 2023. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- ^ Cragg, Michael. "Is Taylor Swift our last remaining real popstar?". i-D. Archived from the original on May 6, 2023. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Seisdedos, Iker (December 27, 2022). "Pop music in the era of Taylor Swift: Behind the success of today's biggest star". El País. Archived from the original on December 27, 2022. Retrieved December 28, 2022.

- ^ Asmelash, Leah; Andrew, Scottie (December 31, 2019). "The 10 artists who transformed music this decade". CNN. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Rosen, Jody (November 17, 2013). "Why Taylor Swift Is the Reigning Queen of Pop". New York. Archived from the original on November 19, 2013. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ a b Chapman, Steve (November 2, 2023). "Steve Chapman: How Taylor Swift restored my faith in humanity". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on November 3, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ "And the world's greatest female leader is ... Taylor swift". Fortune. March 26, 2015. Archived from the original on September 17, 2023. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Khan, Fawzia (June 18, 2021). "The Might Of Taylor Swift". Elle. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ a b c McMarlin, Shirley (June 13, 2023). "How popular is Taylor Swift? It's the 2023 version of Beatlemania". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Archived from the original on June 17, 2023. Retrieved June 17, 2023.

- ^ Rosa, Christopher (December 24, 2019). "Taylor Swift Is the Artist of the Decade—Whether You Like It or Not". Glamour. Archived from the original on December 15, 2023. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Peoples, Glenn (October 27, 2023). "Taylor Swift's New '1989' Will push Aside the Original — Just Like Her Other 'Taylor's Version' Albums Have". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 30, 2023. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ Snapes, Laura (October 30, 2023). "Baby, one more time: why Madonna, Britney Spears and Taylor Swift are all on a nostalgia trip". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 2, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ a b Bream, Jon (June 24, 2023). "Taylor Swift delivers the most fan-fulfilling concert of all time in Minneapolis". Star Tribune. Retrieved June 24, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Franssen 2022, p. 90-92.

- ^ a b Grady, Constance (October 12, 2023). "The Eras concert movie is Taylor Swift leveling up". Vox. Archived from the original on October 12, 2023. Retrieved October 13, 2023.

- ^ "Taylor Swift: 'My Confidence Is Easy To Shake'". NPR. November 2, 2012. Archived from the original on April 28, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2021.Thanki, Juli (September 24, 2015). "Taylor Swift: Teen idol to 'biggest pop artist in the world'". The Tennessean. Retrieved May 13, 2021.Yahr, Emily (June 16, 2016). "Taylor Swift's first song came out 10 years ago. Here's what she was like as a teen songwriter". Arts and Entertainment. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2021.