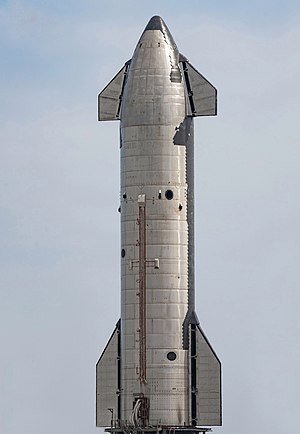

Starship prototipe SN20 at the SpaceX Starbase in Boca Chica (Texas) | |

| Manufacturer | SpaceX |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | United States |

| Applications |

|

| Website | https://www.spacex.com/vehicles/starship/ |

| Specifications | |

| Spacecraft type | Crewed, reusable |

| Payload capacity | 100t - 150t |

| Crew capacity | Up to 100 (planned) |

| Dimensions | |

| Height | 50 m (160 ft) |

| Diameter | 9 m (30 ft) |

| Wingspan | 17 m (56 ft) |

| Production | |

| Status | In development |

| Related spacecraft | |

| Derivatives | Starship HLS |

| Flown with | SpaceX Super Heavy |

Starship is a spacecraft currently under development by American aerospace company SpaceX. Together with its booster, Super Heavy, it composes the Starship super heavy-lift space launch vehicle. The spacecraft is designed to transport both crew and cargo to a variety of destinations, including Earth orbit, the Moon, Mars, and potentially beyond. It is intended to enable long duration interplanetary flights for a crew of up to 100 people. It will also be capable of point-to-point transport on Earth, enabling travel to anywhere in the world in one hour or less.

Development began in 2012, when Elon Musk, CEO of SpaceX, described a plan to build a reusable rocket system with substantially greater capabilities than the Falcon 9 and the planned Falcon Heavy. The rocket evolved through many design and name changes. On July 25, 2019, the Starhopper prototype performed the first successful flight at SpaceX Starbase near Boca Chica, Texas.[1] The SN15 prototype became the first full-size test spacecraft to take off and land successfully in May 2021.[2] On April 20, 2023, Ship 24 and Booster 7 lifted off the pad, the first time the booster and starship flew together as a fully integrated stack.

Design

The Starship spacecraft is 50 m (160 ft) tall, 9 m (30 ft) in diameter, and is fitted with 3 Raptor and 3 Raptor Vacuum engines for increased thrust in the vacuum of outer space.[3][4] The vehicle's payload bay, measuring 17 m (56 ft) tall by 8 m (26 ft) in diameter, is the largest of all planned launch vehicles; its internal volume of 1,000 m3 (35,000 cu ft) is slightly larger than the ISS's pressurized volume.[5] SpaceX also provides a 22 m (72 ft) tall payload bay configuration for even larger payloads.[6]

Starship has a total propellant capacity of 1,200 t (2,600,000 lb)[7] across main tanks and header tanks.[8] The header tanks are better insulated due to their position and are reserved for use to flip and land the spacecraft following reentry.[9]About 130 L (34 US gal) of hydraulic fluid is used for the spacecraft's operations.[10]: 158 A set of reaction control thrusters, mounted on the exterior, control attitude while in space.[11]

The spacecraft has four body flaps to control the spacecraft's orientation and help dissipate energy during atmospheric entry,[12] composed of two forward flaps and two aft flaps. According to SpaceX, the flaps replace the need for wings or tailplane, reduces the fuel needed for landing, and crucially the flaps allow landing at destinations in the Solar System where runways don't exist (for example, Mars).[13]: 1 Under the forward flaps, hardpoints are used for lifting and catching the spacecraft via mechanical arms.[14] The flap's hinges are sealed with metal because they would be easily damaged during reentry.[15]

Starship's heat shield, composed of thousands[16] of hexagonal black tiles that can withstand temperatures of 1,400 °C (2,600 °F),[17][18] is designed to be used many times without maintenance between flights.[19] The tiles are made of silica[20] and are attached with pins rather than glued,[18] with small gaps in between to counteract heat expansion.[15]Their hexagonal shape facilitates mass production[15] and prevents hot plasma from causing severe damage.

Variants

For satellite launch, Starship will have a large cargo door that will open to release payloads and close upon reentry instead of a more conventional jettisonable nose-cone fairing. Instead of a cleanroom, payloads are integrated directly into Starship's payload bay, which requires purging the payload bay with temperature-controlled ISO class 8 clean air.[6] To deploy Starlink satellites, the cargo door will be replaced with a slot and dispenser rack, whose mechanism has been compared to a Pez candy dispenser.[21]

Crewed Starship vehicles would replace the cargo bay with a pressurized crew section and have a life support system. For long-duration missions, such as crewed flights to Mars, SpaceX describes the interior as potentially including "private cabins, large communal areas, centralized storage, solar storm shelters, and a viewing gallery." [6] Starship's life support system is expected to recycle resources such as air and water from waste.[22]

Starship Human Landing System (Starship HLS) is a crewed lunar lander variant of the Starship vehicle that is extensively modified for landing, operation, and takeoff from the lunar surface. It features modified landing legs, a body-mounted solar array, a set of thrusters mounted mid-body to assist with final landing and takeoff, two airlocks, and an elevator to lower crew and cargo onto the lunar surface. Starship HLS will be able to land more than 100 t (220,000 lb) of load on the Moon per flight.[23]

Starship will be able to be refueled by docking with separately launched Starship propellant tanker spacecraft in orbit. Doing so would increase the spacecraft's mass capacity and allow it to reach higher-energy targets,[a] such as geosynchronous orbit, the Moon, and Mars.[24] A Starship propellant depot could cache methane and oxygen on-orbit, and will be used by Starship HLS.[25]

Prototypes and tests

Notes

- ^ Synonymous with increasing the delta-v budget of the spacecraft

References

- ^ Tariq Malik (2019-07-26). "SpaceX Starship Prototype Takes 1st Free-Flying Test Hop". Space.com. Retrieved 2022-01-24.

- ^ Roulette, Joey (2021-05-05). "SpaceX successfully landed a Starship prototype for the first time". The Verge. Retrieved 2022-01-24.

- ^ Dvorsky, George (6 August 2021). "SpaceX Starship Stacking Produces the Tallest Rocket Ever Built". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Petrova, Magdalena (13 March 2022). "Why Starship is the holy grail for SpaceX". CNBC. Archived from the original on 28 May 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ Garcia, Mark (5 November 2021). "International Space Station Facts and Figures". NASA. Archived from the original on 6 June 2022. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ a b c "Starship Users Guide" (PDF). SpaceX. March 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 August 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ Lawler, Richard (29 September 2019). "SpaceX's plan for in-orbit Starship refueling: a second Starship". Engadget. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (30 March 2021). "Watch SpaceX's launch and attempted landing of Starship prototype rocket SN11". CNBC. Archived from the original on 30 March 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- ^ Kooser, Amanda (1 October 2019). "Elon Musk video lets us peep inside SpaceX Starship". CNET. Archived from the original on 10 June 2022. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ "Final Programmatic Environmental Assessment for the SpaceX Starship/Super Heavy Launch Vehicle Program at the SpaceX Boca Chica Launch Site in Cameron County, Texas" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration and SpaceX. June 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 June 2022. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ Wattles, Jackie (10 December 2020). "Space X's Mars prototype rocket exploded yesterday. Here's what happened on the flight". CNN. Archived from the original on 10 December 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (3 March 2021). "SpaceX Starship prototype rocket explodes after successful landing in high-altitude flight test". CNBC. Archived from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Starbase Overview" (PDF). SpaceX. 29 March 2023. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ Weber, Ryan (31 October 2021). "Major elements of Starship Orbital Launch Pad in place as launch readiness draws nearer". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Sesnic, Trevor (11 August 2021). "Starbase Tour and Interview with Elon Musk". The Everyday Astronaut (Interview). Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (6 August 2021). "Musk: 'Dream come true' to see fully stacked SpaceX Starship rocket during prep for orbital launch". CNBC. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Torbet, Georgina (29 March 2019). "SpaceX's Hexagon Heat Shield Tiles Take on an Industrial Flamethrower". Digital Trends. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ a b Reichhardt, Tony (14 December 2021). "Marsliner". Air & Space/Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 6 May 2022. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ Inman, Jennifer Ann; Horvath, Thomas J.; Scott, Carey Fulton (24 August 2021). SCIFLI Starship Reentry Observation (SSRO) ACO (SpaceX Starship). Game Changing Development Annual Program Review 2021. NASA. Archived from the original on 11 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ Bergeron, Julia (6 April 2021). "New permits shed light on the activity at SpaceX's Cidco and Roberts Road facilities". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ Dvorsky, George (6 June 2022). "Musk's Megarocket Will Deploy Starlink Satellites Like a Pez Dispenser". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 9 June 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ Grush, Loren (4 October 2019). "Elon Musk's future Starship updates could use more details on human health and survival". The Verge. Archived from the original on 8 October 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ Burghardt, Thomas (20 April 2021). "After NASA taps SpaceX's Starship for first Artemis landings, the agency looks to on-ramp future vehicles". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Scoles, Sarah (12 August 2022). "Prime mover". Science. 377 (6607): 702–705. Bibcode:2022Sci...377..702S. doi:10.1126/science.ade2873. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 35951703. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ "NASA's management of the Artemis missions" (PDF). NASA Office of Inspector General. 15 November 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.