Beatrizsborges (talk | contribs) Tag: Visual edit |

Beatrizsborges (talk | contribs) Tag: Visual edit |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

== Operation == |

== Operation == |

||

[[File:Plan Puits Saint-Charles 1.jpg|thumb]] |

[[File:Plan Puits Saint-Charles 1.jpg|thumb|280x280px]] |

||

In 1848, a steam engine consisting of a single vertical cylinder with a diameter of 49 centimeters and a stroke of 1.356 meters was installed. This was a Meyer machine manufactured in the Expansion workshops, with a flywheel six meters in diameter. The extraction machine's pendulum is supported by two cast-iron columns, and vertical guides frame the piston. The manual braking system was soon replaced by a more efficient steam brake5. The machine is rated at 60 hp6. The extraction compartment has only two guides, and the cages slide on either side of them. The cages can only hold one 315-kg carriage. Rolling is carried out by wheelbarrow in the galleries and with carts on cast-iron or wooden rails. In the same year, a large 700-metre-long inclined plane was built to follow the coal bed7. |

In 1848, a steam engine consisting of a single vertical cylinder with a diameter of 49 centimeters and a stroke of 1.356 meters was installed. This was a Meyer machine manufactured in the Expansion workshops, with a flywheel six meters in diameter. The extraction machine's pendulum is supported by two cast-iron columns, and vertical guides frame the piston. The manual braking system was soon replaced by a more efficient steam brake5. The machine is rated at 60 hp6. The extraction compartment has only two guides, and the cages slide on either side of them. The cages can only hold one 315-kg carriage. Rolling is carried out by wheelbarrow in the galleries and with carts on cast-iron or wooden rails. In the same year, a large 700-metre-long inclined plane was built to follow the coal bed7. |

||

[[File:Plan Puits Saint-Charles 2.jpg|left|thumb]] |

[[File:Plan Puits Saint-Charles 2.jpg|left|thumb|300x300px]] |

||

In 1850, 57,413 tonnes of coal were extracted from the bowels of the Saint-Charles shaft. The latter exploited some of the most important veins in the Ronchamp coalfields, including a four-metre-thick layer in 1862 and a three-metre-thick layer discovered four years later.1 In June 1861, the Saint-Charles pit continued to operate without interruption, extracting 2,585 tonnes of coal. However, this was no longer the most productive pit, as the Saint-Joseph pit extracted 6,258 tonnes and the Sainte-Barbe pit 2,622 tonnes in the same month8. Production amounted to 24,292.8 tons in 1861, 30,205.7 tons in 1862 and 67,036 tons in 18639 |

In 1850, 57,413 tonnes of coal were extracted from the bowels of the Saint-Charles shaft. The latter exploited some of the most important veins in the Ronchamp coalfields, including a four-metre-thick layer in 1862 and a three-metre-thick layer discovered four years later.1 In June 1861, the Saint-Charles pit continued to operate without interruption, extracting 2,585 tonnes of coal. However, this was no longer the most productive pit, as the Saint-Joseph pit extracted 6,258 tonnes and the Sainte-Barbe pit 2,622 tonnes in the same month8. Production amounted to 24,292.8 tons in 1861, 30,205.7 tons in 1862 and 67,036 tons in 18639 |

||

Revision as of 16:57, 7 May 2024

Les installations de surface du puits. | |

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Country | France |

The Saint-Charles shaft (or No. 8 shaft) is one of the main collieries of the Ronchamp coal mine. It is located in Ronchamp, Haute-Saône, in eastern France. In the second half of the nineteenth century, this shaft made it possible to mine large coal seams, contributing to the company's golden age.

Saint-Charles has been open for over fifty years, which is a long life compared to other open shafts in the Ronchamp mining basin. It has also experienced mining disasters such as fires and firedamp blasts. The shaft is distinguished by its revolutionary extraction system using a cleat machine. The process, too complex, was eventually abandoned following technical setbacks.

After closure, the pit buildings were converted into housing; the slag heaps were even re-used between the wars, as they were still rich in coal. At the end of the twentieth century, these same slag heaps, which had become a dumping ground for a nearby factory, burst into flames, frightening the local population.

Situation before sinking

After the Saint-Louis shaft was sunk in the hamlet of La Houillère in 1810, the company dug a series of shafts close to the outcrops, varying in depth from 19 to 165 meters. But the last shafts dug around 1830, found no coal. Shaft no. 5, continued by drilling, found no trace of coal, and shaft no. 6 stumbled on an uplift in the coalfield linked to a fault. In 1839, shaft no. 7 was sunk in search of coal. However, with the company bankrupt, the concession was put up for sale and the sinking stopped.

In 1843, Charles Demandre and Joseph Bezanson bought the Ronchamp concession and continued sinking shaft no. 7. They finally found coal at a depth of 205 meters, behind the uplift1. Shortly after the No. 7 shaft was commissioned, borehole X was drilled on the Champagney plain, uncovering significant coal seams. On August 28, 1845, a prefectoral decree authorized the digging of shaft no. 82.

Sinking

Sinking of the shaft began on September 11, 1845, with a rectangular cross-section measuring 4.64 metres × 2.14 metres; the extraction chamber measures 1.70 metres × 1.76 metres3. By the end of 1846, it had reached a depth of 180 meters. A 60 hp steam engine was installed. On August 19, 1847, at a depth of 225.80 metres, the first layer was encountered, with a thickness of 2.50 metres of pure coal2.

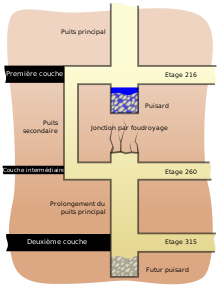

To exploit the first layer immediately, the company uses the “sous stot” digging technique: a second shaft is dug parallel to the main shaft from the first layer. Once the intermediate layer has been reached, a gallery is dug under the main shaft and continues to the second layer. When both sections are completed, a junction is made. Digging lasted from September 1847 to April 18484.

Operation

In 1848, a steam engine consisting of a single vertical cylinder with a diameter of 49 centimeters and a stroke of 1.356 meters was installed. This was a Meyer machine manufactured in the Expansion workshops, with a flywheel six meters in diameter. The extraction machine's pendulum is supported by two cast-iron columns, and vertical guides frame the piston. The manual braking system was soon replaced by a more efficient steam brake5. The machine is rated at 60 hp6. The extraction compartment has only two guides, and the cages slide on either side of them. The cages can only hold one 315-kg carriage. Rolling is carried out by wheelbarrow in the galleries and with carts on cast-iron or wooden rails. In the same year, a large 700-metre-long inclined plane was built to follow the coal bed7.

In 1850, 57,413 tonnes of coal were extracted from the bowels of the Saint-Charles shaft. The latter exploited some of the most important veins in the Ronchamp coalfields, including a four-metre-thick layer in 1862 and a three-metre-thick layer discovered four years later.1 In June 1861, the Saint-Charles pit continued to operate without interruption, extracting 2,585 tonnes of coal. However, this was no longer the most productive pit, as the Saint-Joseph pit extracted 6,258 tonnes and the Sainte-Barbe pit 2,622 tonnes in the same month8. Production amounted to 24,292.8 tons in 1861, 30,205.7 tons in 1862 and 67,036 tons in 18639

In 1868, the most important part of the second layer was mined and production reached 100 tonnes per day. At the same time, the link with the Sainte-Marie shaft was completed, facilitating ventilation10. By 1873, all mining at the Saint-Charles shaft was taking place in the second layer on floors 260 and 315, and consideration was being given to mining the intermediate layer (located between the first and second layers10). Three years later, in January, 2,610 tonnes of coal, 550 cubic metres of water and 673 tonnes of spoil were brought up from the shaft10. In 1877, a telephone was installed to communicate with the bottom of the shaft11.

The cleat machine

By 1849, operations at the Saint-Charles shaft were gradually expanding to the south, east and west. The company considered sinking another well (the Saint-Joseph well, which would be sunk the following year), but sinking a well can take five to six years, and the company needed immediate resources12. It therefore decided to sink an inclined plane at the same time as the Saint-Joseph shaft, to reach the area to be mined more quickly. Breakthrough of this descending gallery began in December 1849. It was initially equipped with a horse-drawn carousel, but this system was not sufficiently efficient, so the engineers thought of a new mining system: the cleat machine12.

Une machine à taquets a déjà été installée au fond de la fosse Davy de la Compagnie des mines d'Anzin à La Sentinelle, dans le bassin minier du Nord-Pas-de-Calais, et les houillères ont décidé d'employer ce système à Ronchamp. Au départ, un seul et même circuit doit partir du puits Saint-Joseph puis emprunter le plan incliné avant de remonter par le puits Saint-Charles.

References