Beatrizsborges (talk | contribs) Tag: Visual edit |

DuncanHill (talk | contribs) Fix harv/sfn no-target errors |

||

| (70 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description| |

{{Short description|French coal mine shaft}} |

||

{{Infobox mine|name=Saint-Charles shaft|image=1880 - Puits Saint-Charles.jpg|caption=surface installations|location=Bourgogne-Franche-Comté|country=[[France]]|type=shaft|opening year=September 14, 1845|active years=August 19, 1847}} |

|||

| name = Achille Germain |

|||

The '''Saint-Charles shaft''' (or No. 8 shaft) is one of the main collieries of the [[Ronchamp coal mines|Ronchamp coal mine]]. It is located in [[Ronchamp]], [[Haute-Saône]], in eastern France. In the second half of the nineteenth century, this shaft made it possible to mine large coal seams, contributing to the company's golden age. |

|||

| image = Achille Germain.jpg |

|||

| birth_date = |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Achille Germain''', born May 5, 1884 in Beaupréau (Maine-et-Loire) and died April 12, 1938 in La Flèche (Sarthe), was a French track cyclist. |

|||

Saint-Charles has been open for over fifty years, a long life compared to other open shafts in the Ronchamp mining basin. It has also experienced mining disasters such as fires and firedamp blasts. The shaft is distinguished by its revolutionary extraction system using a cleat machine. The process, too complex, was eventually abandoned following technical setbacks. |

|||

A professional from 1905 to 1919, he won many local events, but also shone on the velodromes of Paris, where he gained a great reputation in middle-distance races, notably taking third place in the French championship in 1914. Second in the Six Jours de Toulouse in 1906, in partnership with Jean Gauban, he also participated twice in the Six Jours de New York, and took part in the first Six Jours de Paris in 1913. |

|||

After closure, the pit buildings were converted into housing; the slag heaps were re-used between the wars, as they were still rich in coal. At the end of the twentieth century, these same slag heaps, which had become a dumping ground for a nearby factory, burst into flames, frightening the local population. |

|||

Achille Germain, nicknamed “Germain de la Flèche” by his followers, also competed in road races, taking part in the 1908 Tour de France, where he placed 16th, achieving his best result with an eighth-place finish on the tenth stage to Bordeaux. The following year, he won a stage in the Circuit de la Loire and finished second overall. |

|||

== Situation before sinking == |

|||

Mobilized as a corporal cyclist with the 317th infantry regiment during the First World War, he retired from the sport in 1919 following an injury sustained during the conflict. He retired to La Flèche to run a cycle repair shop, and became so involved in local life that he was elected town councillor in his final years. |

|||

After the Saint-Louis shaft was sunk in the hamlet of La Houillère in 1810, the company dug a series of shafts close to the outcrops, varying in depth from 19 to 165 meters. But the last shafts dug around 1830, found no coal. Shaft no. 5, continued by drilling, found no trace of coal, and shaft no. 6 stumbled on an uplift in the coalfield linked to a fault. In 1839, shaft no. 7 was sunk in search of coal. However, with the company bankrupt, the concession was put up for sale and the sinking stopped. |

|||

In 1843, Charles Demandre and Joseph Bezanson bought the Ronchamp concession and continued sinking shaft no. 7. They finally found coal at 205 meters, behind the uplift.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|2001|p=17}}</ref> Shortly after the No. 7 shaft was commissioned, borehole X was drilled on the Champagney plain, uncovering significant coal seams. On August 28, 1845, a prefectoral decree authorized the digging of shaft no. 8.<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

== Biography == |

|||

== Sinking == |

|||

=== Early cycling career === |

|||

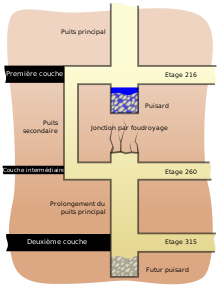

[[File:Fonçage puits Saint-Charles sous stot.svg|left|thumb|The “under stot” sinking method.]] |

|||

Achille Germain was born in Beaupréau, Maine-et-Loire, on May 5, 1884, but his family moved to La Flèche, Sarthe, when he was still very young1. His beginnings in cycling were fairly modest. He took part in his first races in his adopted town in 1902, at the July 14th races held on the Promenade du Pré. He came second in the bonus race2.<ref name=":0">{{Harvtxt|Weecxsteen|1991|p=101}}</ref> |

|||

Sinking of the shaft began on September 11, 1845, with a rectangular cross-section measuring 4.64 meters × 2.14 meters; the extraction chamber measures 1.70 meters × 1.76 meters.<ref name=":1">{{Harvtxt|Mathet|1882|pp=137 144}}</ref> By the end of 1846, it had reached a depth of 180 meters. A 60-hp steam engine was installed. On August 19, 1847, at a depth of 225.80 meters, the first layer was encountered, with a thickness of 2.50 meters of pure coal.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=3}}</ref> |

|||

To exploit the first layer immediately, the company uses the “sous stot” digging technique: a second shaft is dug parallel to the main shaft from the first layer. Once the intermediate layer has been reached, a gallery is dug under the main shaft and continues to the second layer. When both sections are completed, a junction is made. Digging lasted from September 1847 to April 1848.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=4}}</ref> |

|||

The following year, he joined the newly-formed Union vélocipédique fléchoise (UVF), and at the same July 14th meeting, came second in the speed final and third in the bonus race. On September 20, he finished second in the 100-kilometer UVF Cup behind Mareau from Mance, a member of the Union Auto-Cycliste de la Sarthe2.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

[[File:Buffalo, le jour du bol d'or 1897.jpg|left|thumb|The Buffalo velodrome at the end of the 19th century.]] |

|||

Like many racers of the time, Achille Germain took part in both road and track events. On April 4, 1904, at the opening of the Fléchois velodrome on rue Belleborde, he scored his first victory in the middle-distance race, which he won by half a lap over his rivals. The same day, he reached the final of the sprint race, where he was narrowly beaten by Tubières<ref name=":1">{{Harvtxt|Weecxsteen|1991|pp=102-103}}</ref> from Mance. He went on to achieve good results on the Fléchoise track, finishing third in the Sarthe departmental championship and then in the La Flèche championship in June, and fourth in the regional final the following month, an event won by Nantes rider Hardy3. |

|||

== Operation == |

|||

On July 31, Germain scored a prestigious success on the track of the Buffalo velodrome in Neuilly, clearly dominating the 10-kilometer bonus race. During the event, he won the last five of the ten intermediate sprints, pocketing a ten-franc bonus each time4. Back in La Flèche in September, he took second place in the UVF speed championship behind clubmate Albert Leroy, who had just taken part in the Tour de France3.<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

[[File:Plan Puits Saint-Charles 1.jpg|thumb|280x280px|Plan of Saint-Charles well facilities.]] |

|||

In 1848, a steam engine consisting of a single vertical cylinder with a diameter of 49 centimeters and a stroke of 1.356 meters was installed. This was a Meyer machine manufactured in the Expansion workshops, with a flywheel six meters in diameter. The extraction machine's pendulum is supported by two cast-iron columns, and vertical guides frame the piston. The manual braking system was replaced by a steam brake. The machine is rated at 60 hp6. The extraction compartment has only two guides, and the cages slide on either side of them. The cages can only hold one 315-kg carriage. Rolling is carried out by wheelbarrow in the galleries and with carts on cast-iron or wooden rails. In the same year,<ref group="notes">Jacking” involves digging a mine shaft from the surface. By extension, any excavation of a steeply inclined structure can be described as jacking. This includes not only the excavation, but also the removal of spoil and the initial lining.</ref> a large 700-metre-long inclined plane was built to follow the coal bed.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=5}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Plan Puits Saint-Charles 2.jpg|left|thumb|300x300px|Floor plan of the Saint-Charles: canteen and porter's quarters; weighbridge; administration; old boilers and machine; large chimney; coils; new machine; and c. boilers added during expansions; lamp house; well; smoke channel; thick dividing wall. ]] |

|||

In 1850, 57,413 tonnes of coal were extracted from the bowels of the Saint-Charles shaft. The latter exploited some of the most important veins in the Ronchamp coalfields, including a four-metre-thick layer in 1862 and a three-metre-thick layer discovered four years later.<ref name=":2">{{Cite web |title=Les puits creusés dans le bassin houiller de ronchamp |url=http://www.abamm.org/lespuits.html |access-date=2024-05-07 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref> In June 1861, the Saint-Charles pit continued to operate without interruption, extracting 2,585 tonnes of coal. However, this was no longer the most productive pit, as the Saint-Joseph pit extracted 6,258 tonnes and the Sainte-Barbe pit 2,622 tonnes in the same month.<ref name=":3">{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=34}}</ref> Production amounted to 24,292.<ref name=":3" /> tons in 1861, 30,205.7 tons in 1862 and 67,036 tons in 1863.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Godard|2012|p=336}}</ref> |

|||

In 1868, the most important part of the second layer was mined and production reached 100 tonnes per day. At the same time, the link with the Sainte-Marie shaft was completed, facilitating ventilation.<ref name=":0">{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=35}}</ref> By 1873, all mining at the Saint-Charles shaft was taking place in the second layer on floors 260 and 315, and consideration was being given to mining the intermediate layer (located between the first and second layers).<ref name=":0" /> Three years later, in January, 2,610 tonnes of coal, 550 cubic metres of water and 673 tonnes of spoil were brought up from the shaft.<ref name=":0" /> In 1877, a telephone was installed to communicate with the bottom of the shaft.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=36}}</ref> |

|||

== Professional racer == |

|||

== The cleat machine == |

|||

=== A benchmark in track racing (1905-1907) === |

|||

[[File:Machine à tacquet 02.jpg|thumb|Plans of the bottom of the shaft. 1: ground plan of the galleries, 2: plan of the brick dams, 3: cross-section of the shaft.]] |

|||

In 1905, Achille Germain, now a 3rd category professional racer, established himself as one of the best cyclists in his region. On the Fléchois velodrome on March 26, he won the speed event, the 45-lap race behind the bike and the bonus race, a domination he repeated on April 24, when he won the Sarthe departmental speed championship, held on the same track, as well as the 25 km race and the bonus race3. At the end of the summer, he scored two further successes, with the Grand Prix de Tours on September 9 and the Grand Prix de Montluçon the following day, both in the middle-distance race5. He also distinguished himself in more modest competitions, such as the 4-kilometer cantonal race he won in Verron in early October5, or at folklore events: the Pinder circus was visiting La Flèche, and Achille Germain competed with several Fléchois amateurs on the “Canadian track”, a 6.5-meter-diameter construction of wooden rungs spaced ten centimeters apart and inclined at 75 degrees. After an unsuccessful first attempt, he achieved the best performance of the participants, completing eight laps of the track6. |

|||

By 1849, operations at the Saint-Charles shaft gradually expanded to the south, east, and west. The company considered sinking another well (the Saint-Joseph well, which would be sunk the following year), but sinking a well can take five to six years, and the company needed immediate resources. It therefore decided to sink an inclined plane at the same time as the Saint-Joseph shaft, to reach the area to be mined more quickly. The breakthrough of this descending gallery began in December 1849. It was initially equipped with a horse-drawn carousel, but this system was not sufficiently efficient, so the engineers thought of a new mining system: the cleat machine.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=8}}</ref> |

|||

A cleat machine has already been installed at the bottom of Compagnie des Mines d'Anzin's Davy pit in La Sentinelle, in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais coalfield, and the collieries have decided to use the same system at Ronchamp. Initially, a single circuit is to start from the Saint-Joseph shaft, then follow the inclined plane before climbing back up through the Saint-Charles shaft.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|pp=8-9}}</ref> |

|||

During the winter of 1905-1906, Achille Germain trained alongside the best specialists of the day on the Vélodrome d'Hiver track in Paris. He can see the gap that still separates him from the leading racers, but his persistence in training is noticed. Along with Georges Parent, he was chosen to join the coaching team of Henri Cornet, winner of the 1904 Tour de France, in a 50-kilometer tandem matchNote 1 against Karl Ingold. Cornet won by nine laps. At the same meeting, Germain made his mark as an individual in the 15-kilometer race behind motorcycles. Third behind Paul Rugère and Anton Jaeck, his offensive behavior throughout the race was praised by the spectators7. On February 18, he teamed up with Denmark's Axel Hansen in the American-style Twelve Hours race, in which the two competitors took turns at will. At the end of the race, fourteen teams were still classified in the same lap: victory was therefore decided over six laps between the best sprinters in each team. Hansen initially placed fourth, but the commissaires were slow to validate the results after a crash on the last lap. The race was eventually cancelled7. On March 4, a meeting was held at the La Flèche velodrome, bringing together a number of well-known riders. On his home turf, Achille Germain took third place in the bonus race behind Charles Vanoni and Victor Thuau, before losing out to César Simar, Olympic medalist two years earlier, in the 10-kilometer race behind the bike8. |

|||

[[File:Machine à tacquet 01.png|thumb|292x292px|The cleat machine.]] |

|||

[[File:Parc des Princes juin 1906 30 km.png|thumb|Achille Germain (left) at the start of a race at the Parc des Princes on June 3, 1906.]] |

|||

In 1850, more than 200 meters below the surface, a steam engine and two boilers were installed in a large room close to the coal beds. The room, 50 meters from the shaft, is 17 meters long, 8 meters wide, and 4 meters high, and is supported by a massive oak framework, some parts of which are 40 cm square. This steam engine powers the cleat machine installed in the 700-meter-long inclined plane. The underground machines and boilers were supplied by Sthelier of Thann, as were the engine and all the cleat equipment for the vertical shaft. These elements were installed and ready for use on May 20, 1852. Until 1853, major mechanical operating problems were encountered, but these were resolved as testing progressed. Engineer Schutz was one of the instigators of this initiative, the machinery having been invented by Mr. Mehus 1. Conversely, engineer Francois Mathet, who joined the company in 1855, was highly critical of the system and its adoption, finding it dangerous for miners' lives due to the drought that could disrupt ventilation and even cause firedamp. He also described the fragility of the woodwork and the high temperatures the drivers had to endure.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Mathet|1882|pp=139-140}}</ref> On October 19, the underground boilers were lit, but immediately the fire, fanned by the 250-meter-high chimney, sucked all the air out of the mine. As a result, ventilation was difficult, and the workings were invaded by firedamp. On March 12, 1853, the inclined plane's cleat machine was put into operation. The water accumulated at the bottom of the large chute is evacuated by hand pumps installed at the top and bottom of the inclined plane over 200 meters. These pumps were operated by women. But on April 1, despite all the precautions taken, a fire broke out in the woods near the boilers.<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

The outdoor season brought him many successes. On April 23, 1906, in La Flèche, he won the 15-kilometer race behind motorcycles ahead of Arthur Pasquier, then set the track record over 10 kilometers8. The following week, in Tours, he won the 50 kilometer race behind motorcycles, again ahead of Pasquier, then shared victory with Jean Gougoltz in the Grand Prix du Conseil Général in Nantes on May 6. His performances attracted the goodwill of the newspaper L'Auto, which had already dubbed him “Germain de la Flèche”: “The middle-distance race went very easily to the Fléchois crack, Germain. This fellow is about to play a major role8 “. On June 3, he discovered the Parc des Princes track and took third place in the 30-kilometer race behind Antoine Dussot and Henri Lautier, which earned him selection by the organizers of the Grand Prix de Paris. Thanks to the financial support of Viscount de Lesseville, head of the Union Vélocipédique Fléchoise, he was able to employ several trainers to compete in the one-hour race behind tandems. Competing against two of the best cyclists of the time, Henri Cornet and René Pottier, he was soundly beaten, but as with every one of his outings, his attitude was widely praised by the specialists, and Germain became one of the public's most popular riders9,10. At the beginning of July, at the Vélodrome Buffalo, he failed in his attempt to beat the world record for 10 kilometers without trainers, held by Lucien Petit-Breton11,12, but a few days later he scored a clear success over 15 kilometers behind motorcycles on the same track9. On July 15, in La Flèche, in front of an enthusiastic crowd, he won two of the three events organized and took the overall victory9. At the end of August, he was the only rider to hold off César Simar over 30 kilometers at Le Buffalo, then clearly dominated Émile Bouhours over the same distance at Tours in early September13. |

|||

In 1855 and again in 1856, the Saint-Charles shaft produced 54,081 tonnes of coal thanks to the cleat machine. That same year, however, the decision was made to abandon this machine. At the same time, the women were dismissed from mine 1. The following year, the machine was dismantled and replaced by a wheel mining machine. This set in motion two cables, one ascending, the other descending, and vice-versa. Each cable was guided by two parallel wooden sills.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=7}}</ref> |

|||

Achille Germain then took part in the Six Jours de Toulouse, the first race of its kind in Europe, held on the Bazacle velodrome, where he teamed up with local rider Jean Gauban. The duo achieved a promising second place, second only to brothers Émile and Léon Georget. Throughout the event, the Fléchois rider was extremely active, winning numerous prizes, including those for the 47th and 49th hours14,15. On his return, he was triumphantly welcomed back to La Flèche. A few days later, he was sent to Toul barracks, where he was to perform his military service with the 153rd infantry regiment16,17. |

|||

In May 1852, a second machine of the same type, but vertical, was put into service over the entire height of the shaft, replacing the Meyer coil machine. It too suffered numerous breakdowns, requiring frequent shutdowns to readjust various parts over several months and in the years that followed. Finally, on March 29, 1857, the Board of Directors decided to return to the cable extraction system, and the vertical cleat machine was dismantled in 48 days, starting the following May 17. A 9-meter-high wooden headframe was built over the shaft, and the Meyer machine was refurbished.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Mathet|1882|pp=141-173}}</ref> |

|||

Achille Germain was rarely granted leave, but managed to take part in a few races in 1907: beaten by Arthur Pasquier over 40 kilometers in Tours on April 21, he took his revenge and beat him the following week in La Flèche at the Grand Prix du Printemps17 |

|||

=== Accidents and disasters === |

|||

=== Participation in the Tour de France (1908) === |

|||

[[File: |

[[File:Puits Saint-Charles XXe - 03.JPG|thumb|Miners in the shaft around 1880.]] |

||

Three firedamp blasts occurred in 1857: eight miners perished on January 29, two on March 3, and two on March 14.<ref name=":2" /> On March 16, the entire workforce went on strike of these disasters. The shaft was deemed too dangerous, with poor ventilation and faulty equipment. The management lodged a complaint for coalition offenses, but the [[Haute-Saône]] prefecture ruled in favor of the miners, and the engineer was sentenced to prison for flagrant breaches of safety.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|2010|p=91}}</ref> |

|||

Released from military service on March 1, 1908, Achille Germain wanted to take part in more road races: he considered taking part in Paris-Roubaix, but eventually had to give up18. On the velodrome track in La Flèche, in early April, he won the Sarthe speed championship, then finished second to Pasquier in the [[Grand Prix du Printemps]]. In May, on the same track, he won a 12-hour race by a clear 16-lap margin over his nearest rival. A few days later, he came second in the 40-kilometer Grand Prix d'Angers with trainers and announced his entry in the Tour de France18,19. It was the only Tour he contested during his career18. |

|||

On November 8, 1857, a fire broke out in the underground boiler room. The openings of shafts no. 7 and Saint-Charles are hermetically sealed. On January 18 the following year, a dog and a lighted lamp descended to the bottom of the shaft to test for the presence of a firedamp. On January 30, the openings in both shafts were reopened. However, energetic ventilation rekindled the fire in the coal. In 1859, water flooded the mine after more than six months of inactivity.<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

He had a difficult start to the race: at best, he finished 22nd on the fifth stage from Lyon to Grenoble, and was 25th overall on the evening of the sixth stage to Nice. However, race conditions were very tough at the start of the Tour, and only 45 of the 114 entries were still in contention. He went on to achieve some convincing results: 19th in [[Nîmes]] and 15th in [[Toulouse]], 17th in [[Bayonne]] and 8th in [[Bordeaux]], having been among the frontrunners throughout the race. Achille Germain finished the Tour de France with three 12th places and one 14th. In the end, he came 16th with 236 points, 200 behind the winner Lucien Petit-BretonNote 2. This encouraging participation earned him the congratulations of many specialists, such as L'Auto journalist Charles Ravaud, who considered him capable of achieving excellent results if he chose to devote himself even more to the road20. His participation in the Grande Boucle further boosted his popularity: he was carried in triumph on his return to La Flèche station and welcomed into town by over 2,000 people1. |

|||

In 1886, the shaft was bricked up from top to bottom, with a diameter of 3.30 meters. At the bottom, for the first time in Ronchamp, metal frames were installed over a kilometer of the gallery. Unfortunately, in June of the same year, another firedamp explosion killed twenty-three people.<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

=== Success on the road and Six Days of New York (1909) === |

|||

[[File:Lavalade (portrait du coureur sur (...)Agence Rol btv1b531135697.jpg|thumb]] |

|||

Resting during the winter, he made his comeback on April 25, 1909 at the La Flèche velodrome and retained his Sarthe speed champion title21. Beaten in Angers by Daniel Lavalade over 40 kilometers behind motorcycles21, he distinguished himself at the end of May by taking second place in the Circuit de la Loire road race, run over two stages, having won the first in Loudun22. Invited to take part in the eighth stage of the Wolber Grand Prix, organized by Peugeot on June 13 between Paris and La Flèche, Achille Germain placed sixth and, according to L'Auto, earned “his stripes as a great road racer ”23. He was also invited to take part in the ninth stage to Nantes, where he finished fourth before being downgraded for a course error21. |

|||

=== The ending === |

|||

During the summer, he opted out of the Tour de France to compete in a series of lucrative track races. Forced to retire from a 24-hour race in Marseille, he teamed up with Bouteiller for a 12-hour race in Toulouse, taking second place after a hard-fought battle with Jean-Baptiste Dortignacq21. In September, he was one of the main favorites for the Bol d'or, held on the track of the Buffalo velodrome. In the lead after the first four hours of the race, run without trainers, he suffered a serious setback and lost contact: he was only in seventh and last place after seven hours. In the last quarter of the race, Achille Germain overtook two rivals and finally finished fifth with a total of 681.6 kilometers, a long way from three-time winner Léon Georget24. |

|||

After the 1886 disaster, a large part of the galleries and the construction site were destroyed, in addition, forty years of intensive mining had greatly depleted the deposit, leaving the shaft virtually abandoned. But three years later, strong demand for coal prompted the company to rehabilitate the entire site and resume mining.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=39}}</ref> |

|||

In 1891, the pit was fitted out to accommodate around a hundred workers, but two years later, work was again halted, and only water was brought up from the shaft.<ref name=":4">{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=40}}</ref> The following year, mining was resumed to remove the remains of coal panels,<ref group="notes">The panels are large-area pillars or unused mine areas.</ref> estimated to weigh 10,000 tonnes. They were excavated at a rate of 100 tonnes per day by around one hundred workers.<ref name=":4" /> In October 1895, the workers completed the stripping<ref group="notes">When a mine or shaft is mined, galleries are dug in a checkerboard pattern to extract the coal, forming regular, square natural pillars. When all the galleries have been dug, these pillars, which contain a lot of coal, are removed. This is known as “de-piling”.</ref> and proceeded with the clearing.<ref group="notes">When digging the galleries, natural pillars are not enough, so wooden beams are installed. At the end of the operation, they are reclaimed. This is known as “deforestation”.</ref> This work was completed in December of the same year. The shaft was then backfilled.<ref name=":4" /> |

|||

Achille Germain made his return to the road at the end of September with Paris-Tours. His eighteenth-place finish was anecdotal, just as his last few outings on the track were hardly conclusive: he failed twice in his attempt to set the record for the hour without a trainer at La Flèche24. In early December, however, he was selected for the Six Days of New York, one of the world's most famous races, where he teamed up with British runner Reginald Shirley. In the 50th minute of the race, Shirley caused a heavy crash when he passed the baton to Germain, who was hit in the right leg. The duo conceded a lap to the other teams, and despite Germain's best efforts, were unable to catch up. At the end of the first day of racing, Shirley retires, suffering from stomach pains. Achille Germain was joined by the Italian Egisto Carapezzi, whose partner had also been forced to withdraw. In accordance with the regulations, the new crew received a one-lap penalty, but this was nothing compared to the number of laps Carapezzi regularly conceded during his stints. The duo were 21 laps down after 34 hours of racing. Redoubling their efforts to overcome the deficit, the two men suffered a breakdown at the same time and interrupted their race for two hours. At the end of the fifth day, Carapezzi gave up, and despite Achille Germain's desire to continue the race, the judges deemed him too retarded to continue, his deficit having risen to almost 900 laps25. |

|||

== Conversion == |

|||

=== Middle-distance specialist (1910-1913) === |

|||

The shaft was backfilled from January to June 1896 at around ten carloads of shale per day. In May, an eight-meter-thick plug of clay and concrete was installed to make the shaft watertight.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|pp=40-55}}</ref> The surface installations were demolished, except the machine building, which was converted into housing, and another building which housed accommodation and the “La Ruche” store.<ref name=":7">{{Harvtxt|PNRBV|1999|p=24}}</ref> The adjacent store was demolished in 2005 after being destroyed by fire.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Ancien magasin La Ruche |url=http://www.abamm.org/divers02.html |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Achille Germain 1910.png|left|thumb|Achille Germain in 1910.]] |

|||

At the beginning of 1910, Achille Germain once again gave priority to the track. He obtained convincing results at local level, but struggled to confirm his performance in the major Parisian events. In May, however, he competed in the French road championships with coaches. Dropped after the first few kilometers, he eventually came tenth26. After a detour to the track and a success in Brest over 25 kilometers at the expense of César Simar, he returned to the road to take tenth place in Paris-Le Mans27. During the summer, Achille Germain took several places of honor on the velodromes, coming second in the Grand Prix d'inauguration du vélodrome d'Angers, the Challenge Cointreau in the same town, and the Huit heures de Tours, which earned him selection for the Bol d'or. Ill and suffering from the pace set by Léon Georget, he retired shortly after the halfway mark. As in the previous year, he was selected to take part in the Six Days of New York, this time in partnership with the Belgian Verlinden. The two men never found their rhythm and retired after just eight hours of racing27. |

|||

At the beginning of the 21st century, several of the pit's buildings still stand, including the well-preserved mining machine building, repainted white, and the large building housing the mine masters and the canteen. All these buildings have now been converted into housing.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Le puits Saint Charles |url=http://www.abamm.org/stcharle.html |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref><gallery mode="packed" widths="280"> |

|||

In 1911, Achille Germain opened a repair shop in La Flèche for bicycles of all makes1. At the same time, the J.B. Louvet team hired him to race on the road, but after his withdrawal from Paris-Tours, he gave up on Paris-Roubaix, preferring to take part in a track event in Angers. Germain also became a race organizer, setting up the Grand Prix Jean-Baptiste Louvet in La Flèche on May 7. The 130-kilometer road race, open only to members of the Union vélocipédique de France, criss-crossed the region's roads, passing through Le Lude and Baugé1. |

|||

File:Puits Saint-Charles 2015.JPG|The floor of the Saint-Charles well in 2015. |

|||

[[File:27.08.1910 Bol d'Or.jpg|thumb]] |

|||

File:Puits Saint-Charles 2013 (2).JPG|Area where the well is located. |

|||

After several middle-distance successes in Angers and Nantes, notably at the expense of American Woody Headspeth, he returned to the road for Paris-Brest-Paris in the road-tourist category. A crash before Rennes destroyed his bike, and Germain had to walk the 14 kilometers to the city. Unable to repair it, he gave up28. His winter season began with several places of honor, but it was on December 17, at the Vélodrome d'Hiver, that he won a convincing victory in the Prix Robl, a middle-distance race run over 25 kilometers and organized in tribute to the German champion Thaddäus Robl, who died in a plane crash28. Germain not only raced for his own account, but also regularly acted as a trainer for other riders, as in the Prix de Madison Square at the beginning of the following January, in which American Joe Fogler owed his victory in part to him28. |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

[[File:Achille Germain 1912.png|left|thumb]] |

|||

During the 1912 season, Achille Germain concentrated mainly on middle-distance running. He racked up successes in Rouen, Paris and Angers, usually against second-rate opponents. On June 9, on the Parc des Princes track, he took fourth place in the French middle-distance championship, run over 100 kilometers, finishing fifteen laps behind the winner Paul Guignard and seven off the podium29. A week later, in Nantes, he finally beat worthy rivals Émile Bouhours and César Simar in a 50-kilometer race. In August, he came third in the Critérium de demi-fond at Le Buffalo, then won the Le Mans meeting on the Jacobins velodrome. On September 15, he suffered a severe setback in the Grand Prix de France de vitesse at the Parc de Princes, failing in the heats, but returned to the limelight at the end of the year with a convincing victory in the Prix Stocks, run over 40 kilometers at the Vélodrome d'Hiver. Danish rider Herman Kjeldsen was the only rider to stand up to him in this event, but Germain was the strongest and displayed a radiant form that earned him selection for the first Six Jours de Paris, on January 13, 191329. |

|||

== Mining town and shops == |

|||

On the Vel' d'hiv' track, during the first two days, Achille Germain, in partnership with Édouard Léonard, animated the race by consistently leading the pack, but the two riders began to lose contact after the 50th hour of the race. The duo finished ninth, six laps behind the winners, but Germain and Léonard were among the race's top prizewinners30. After the race, Achille Germain's popularity soared once again, enabling him to negotiate higher participation rates at various velodrome meetings. After successes in Angers in March, he made a strong impression on April 13, winning a 30-kilometer race ahead of Daniel Lavalade and César Simar at the Buffalo31. A journalist from ''L'Auto'' declared: "The middle-distance race has returned to the runner with courage personified. My name is Achille Germain32. Considered an outsider for the French middle-distance championship, he took fourth place, a long way behind the winner Paul Guignard. At the [[Grand Prix de Paris]], he came second in the 50-kilometer race, well ahead of Georges Sérès, but containing the return of several well-known runners. He concludes the season with another place of honour, finishing second in the Grand Prix de clôture de Roubaix31. |

|||

{{coord|47.702515|6.653095|scale:1000_region:FR|name=Ateliers centraux et bureaux}} |

|||

[[File:Paul Guignard 9.6.1912.jpg|thumb]] |

|||

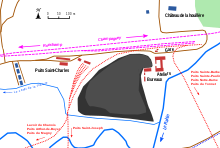

[[File:Plan Puits Saint-Charles - annexes - terrils - cités.svg|thumb|The environment of the Saint-Charles well and its ancillary facilities.{{Legend|black|slag heaps}}{{Legend|#800000|Mine buildings}}{{Legend|#004080|Mining town}}{{Legend|red|Coal mining network|outline=red dotted}}{{Legend|blue|Line from Vesoul to Plancher-les-Mines Chemins de fer vicinaux de la Haute-Saône}}{{Legend|pink|Ligne de Paris-Est à Mulhouse-Ville Compagnie des chemins de fer de l'Est then Société nationale des chemins de fer français}}]] |

|||

As in the previous year, Achille Germain teamed up with Édouard Léonard for the Six Jours de Paris, which started on January 12, 1914. After Léonard dropped out on the second day of the race, Germain teamed up with Charles Meurger, and came within two laps of the leaders. Le Fléchois kept the duo afloat, but Meurger, more of a sprint specialist, conceded several laps and eventually retired after the 61st hour. Germain continued the race with a third team-mate, Alfred Beyl, but it was he who finally retired after 102 hours, having won numerous primes33. After a series of fine performances at the Paris meetings and a major success at the Grand Prix du Printemps de Limoges, he achieved the best result of his career at the French middle-distance championship on July 19, finishing third in the event, won once again by Paul Guignard34. |

|||

In 1866, a food and clothing store was built on the site of the Saint-Charles well, next to the offices. It was later expanded to include a bakery and butcher's shop, and named “La Ruche”. The store was run by the company, and miners' purchases were deducted directly from their wages via their order and payroll books. After the [[World War II|Second World War]], the store became a cooperative limited company with shares on the stock exchange.<ref name=":7" />[[File:Cité minière Saint-Charles.JPG|left|thumb|Saint-Charles housing estate.]]To accommodate the large workforce employed at the Saint-Charles shaft, a mining housing estate was built in 1872, a few dozen meters from the pithead. It consisted of four houses built of roughcast sandstone rubble, each with a single storey and long-sloped mechanical tile roofs.<ref name=":5">{{Harvtxt|PNRBV|1999|p=25}}</ref><ref name=":6" /><ref>{{Cite web |title=La cité Saint Charles |url=http://www.abamm.org/citeou04.html |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref> Although the collieries had originally intended to build 24 dwellings, they had to give up for financial reasons. Each house is divided into four units, with two bedrooms, a kitchen, a cellar, an attic, and a garden for each family.<ref name=":5" /> On March 11, 2010, the houses were listed in the general inventory of cultural heritage.<ref name=":6" /> |

|||

== The slag heap == |

|||

=== World War I and end of career (1914-1919) === |

|||

The “terril du puits Saint-Charles” is a fairly extensive flat slag heap where waste rock has been piling up for half a century. Between 1926 and 1931, the slag heap's shales were sorted at the coal washing center to extract the remaining coal that was used as fuel for the boilers installed on the Chanois plain.<ref name=":8">{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=41}}</ref> |

|||

A few days later, the First World War broke out and, like his competitors, Achille Germain was mobilized. Assigned to the 317th infantry regiment as a corporal cyclist, he was in charge of transporting mail by bicycle. During the war, however, he took part in a number of races on leave. On November 19, 1916, he took part in a 400-lap American-style race at the Vélodrome d'Hiver. Teaming up with Marius Chocque, he came tenth35. In December 1917, on the same track, he won the Prix de la Capitale over 30 kilometers, and the following year he won the Prix d'Avril middle-distance race at the Vel' d'Hiv'35. He then beat a Belgian runner in a middle-distance match held at the Beaulieu velodrome in Le Mans35. |

|||

In June 1993, the 15-metre-high slag heap containing 35,000 m<sup>3</sup> of shale caught fire. A neighboring plant (MagLum) had previously buried waste such as zinc, cyanide, nickel, sulfur, polyurethane foam, hydrogen sulfide, phenols and hydrocarbon derivatives there. Thick black smoke billowed over the communes of [[Ronchamp]] and [[Champagney, Haute-Saône|Champagney]], causing concern and mobilizing the population. Gas analyses and health monitoring of children were carried out (27 of them complained of various symptoms: vomiting, nausea, headaches, throat and eye irritations). Analyses revealed heavy metal content (including aluminum) 750 times higher than the norm, as well as traces of trichloroethylene and nitrate vapors. Despite the intervention of the fire department and the installation of firebreak trenches and barriers, the fire persisted for months.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Le feu dans le terril de Saint Charles |url=http://www.abamm.org/terris11.html |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref><ref name=":8" /><ref>{{Cite web |date=1994-02-07 |title=La psychose d'un ancien village minier face au terril en feu depuis neuf mois - L'Humanité |url=https://www.humanite.fr/-/-/la-psychose-dun-ancien-village-minier-face-au-terril-en-feu-depuis-neuf-mois |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=humanité |language=fr-FR}}</ref> Part of the slag heap had to be moved in 1994 to extinguish it. The slag heap was then used as backfill for a road.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Enlèvement des schistes brûlants |url=http://www.abamm.org/terris12.html |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref> The Saint-Charles pit still has a large slag heap, even though a large part of it was removed during the fire.<ref name=":6">{{Cite web |title=Le terril de Saint Charles |url=http://www.abamm.org/terris10.html |access-date=2024-05-07 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref><gallery mode="packed" widths="250"> |

|||

Demobilized at the beginning of 1919, Achille Germain returned to racing more intensively. Third in the one-hour Trophée de Paris in May, he won the Grand Handicap de demi-fond at the Parc des Princes on July 6. Although he seemed to be in full possession of his powers, he had to put an end to his career because of a groin injury, contracted during the war, which eventually reopened35,36. |

|||

File:2018-03 - Terril Saint-Charles - 01.jpg|General aerial view of the slag heap, shaft buildings and large offices. |

|||

File:2015-11 - Terril Saint-Charles - 14.JPG|View of the slag heap. |

|||

File:2015-11 - Terril Saint-Charles - 03.JPG|The summit. |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

== Workshops and offices == |

|||

[[File:Ateliers-Bureaux-Ronchamp XXe 01.jpg|thumb|Large offices and workshops.]] |

|||

Achille Germain then retired to La Flèche to run his cycle repair shop. Very involved in local life, he invited his friend Robert Spears, world track speed champion, to lay a wreath at the cemetery to commemorate the Armistice on November 11, 192037. In 1922, to pay tribute to the veterans of the Great War, he inaugurated a commemorative plaque on the birthplace of Fléchois aviator Charles Godefroy, made famous by his flight under the Arc de Triomphe in Paris on August 7, 191937,38. Two years later, a Poilus banquet was organized on his initiative in the ballroom of the Hôtel du Cheval Blanc. On this occasion, he donated one of his racing bicycles, offered to the winner of a tombola organized for the benefit of the Anciens Combattants37. Achille Germain was elected vice-chairman of the town's Comité des Fêtes in March 192639. |

|||

{{Coord|47.702515|6.653095}} |

|||

Shortly after the opening of the shaft and its good results, the company decided to set up its central workshops and offices next to the shaft and established a link with the rail network. These facilities remained the nerve center of the collieries until their closure in 1958.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Les ateliers de réparation des mines |url=http://www.abamm.org/ateliers.html |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref> The site was converted into a car manufacturing subcontracting plant before being decommissioned in 2008. At the beginning of the 21st century, the site was used for exhibitions and shooting games. |

|||

But he didn't give up cycling. In 1920, he took on the role of motorcycle coach to Tunisian Ali Neffati, and in the same year, together with his friends, set up a new multi-sports club, "La Flèche-Sportive "36. Among other achievements, this club organized a road race, Paris-La Flèche, which ran for three consecutive editions40. At the same time, Germain was involved in the construction of a new stadium and velodrome to replace Belleborde. After several months of negotiation, work began on a plot of land adjacent to the Route d'Angers: the stadium was inaugurated in November 1921 for a soccer match, while the track was built in early 1922 thanks to the financial support of several great champions, including Robert Spears, Oscar Egg, Maurice Brocco, aviator Georges Kirsch and boxer Georges Carpentier36. In 1925, Achille Germain set up the Printania restaurant and dance hall opposite the new stadium, which quickly became one of the city's most popular entertainment venues41. |

|||

== The station == |

|||

In April 1931, he stood as an independent Republican candidate in the municipal by-elections in La Flèche. Obtaining 1,111 votes, the highest total, he was among the five newly elected. He also ran in the 1932 legislative elections. With 4,108 votes, he came third, more than 5,600 votes behind the incumbent Radical candidate Jean Montigny, who was elected in the first round42. |

|||

[[File:Puits Saint-Charles XXe - 01.JPG|thumb|Loading coal wagons at the shaft exit.]] |

|||

{{Coord|47.703343|6.653262}} |

|||

Once the coal carts have been hauled up from the Saint-Charles shaft, they are emptied into large wagons. The wagons are transferred to a station close to the shaft via a railroad built in 1858, before the coal is shipped to the coal mine's customers, most of whom are from [[Alsace]], via the Paris-Est to [[Mulhouse-Ville station|Mulhouse-Ville]] railroad.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Le réseau ferré entre les puits |url=http://www.abamm.org/resferre.html |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref> |

|||

Re-elected to the La Flèche town council in 1935, still as an independent, he served until his death on April 12, 1938, at the age of 5443. He is buried in the Saint-Thomas cemetery. On May 22, 1978, the town of La Flèche paid tribute to him by naming the street of a newly-built housing estate after him43. |

|||

The station was in operation from the mid-19th century until 1958, when the mines closed, after which it was dismantled. At the beginning of the 21st century, the station site was overgrown, and only a few remnants of the installations and network remained. |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

*[[Lille]] |

|||

*[[ |

*[[Ronchamp coal mines]] |

||

*[[ |

*[[Mining in France]] |

||

*[[Sainte-Barbe Coal Mine]] |

|||

*[[Cokerie-lavoir du Chanois]] |

|||

== References == |

== References == |

||

<references /> |

<references /> |

||

== Bibliography == |

|||

* |

|||

== Notes == |

== Notes == |

||

<references group="notes" /> |

<references group="notes" /> |

||

== Bibliography == |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Parietti |first=Jean-Jacques |title=Les Houillères de Ronchamp |date=2001 |publisher=Éditions Comtoises |isbn=2-914425-08-2}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Parietti |first=Jean-Jacques |title=Les Houillères de Ronchamp, vol. 2: Les mineurs |date=2010 |publisher=Franche-Comté culture & patrimoine |isbn=978-2-36230-001-1}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Parietti |first=Jean-Jacques |title=Le puits Saint-Charles, coll. Les dossiers de la Houillère |date=1999 |publisher=Ronchamp, Association des amis du musée de la mine}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Mathet |first=François |url=http://jubilotheque.upmc.fr/ead.html?id=GR_000387_001 |title=Mémoire sur les mines de Ronchamp |date=1882 |publisher=Société de l'industrie minérale |access-date=2024-05-08 |archive-date=2016-03-03 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303201840/http://jubilotheque.upmc.fr/ead.html?id=GR_000387_001 |url-status=dead }} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=PNRBV |title=Le charbon de Ronchamp : circuits miniers de Ronchamp, coll. « Déchiffrer le patrimoine » |date=1999 |publisher=Parc naturel régional des Ballons des Vosges |isbn=2-910328-31-7}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |title=Société de l'industrie minérale, Bulletin trimestriel |date=1882 |publisher=Saint-Étienne}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Thirria |first=Édouard |title=Manuel à l'usage de l'habitant du département de la Haute-Saône |date=1869}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Godard |first=Michel |title=Enjeux et impacts de l'exploitation minière du bassin houiller de Ronchamp |date=2012}} |

|||

[[fr: Puits Saint-Charles]] |

|||

[[Category:Ronchamp coal mines]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 09:21, 30 May 2024

surface installations | |

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Country | France |

| Production | |

| Type | shaft |

| History | |

| Opened | September 14, 1845 |

| Active | August 19, 1847 |

The Saint-Charles shaft (or No. 8 shaft) is one of the main collieries of the Ronchamp coal mine. It is located in Ronchamp, Haute-Saône, in eastern France. In the second half of the nineteenth century, this shaft made it possible to mine large coal seams, contributing to the company's golden age.

Saint-Charles has been open for over fifty years, a long life compared to other open shafts in the Ronchamp mining basin. It has also experienced mining disasters such as fires and firedamp blasts. The shaft is distinguished by its revolutionary extraction system using a cleat machine. The process, too complex, was eventually abandoned following technical setbacks.

After closure, the pit buildings were converted into housing; the slag heaps were re-used between the wars, as they were still rich in coal. At the end of the twentieth century, these same slag heaps, which had become a dumping ground for a nearby factory, burst into flames, frightening the local population.

Situation before sinking

[edit]After the Saint-Louis shaft was sunk in the hamlet of La Houillère in 1810, the company dug a series of shafts close to the outcrops, varying in depth from 19 to 165 meters. But the last shafts dug around 1830, found no coal. Shaft no. 5, continued by drilling, found no trace of coal, and shaft no. 6 stumbled on an uplift in the coalfield linked to a fault. In 1839, shaft no. 7 was sunk in search of coal. However, with the company bankrupt, the concession was put up for sale and the sinking stopped.

In 1843, Charles Demandre and Joseph Bezanson bought the Ronchamp concession and continued sinking shaft no. 7. They finally found coal at 205 meters, behind the uplift.[1] Shortly after the No. 7 shaft was commissioned, borehole X was drilled on the Champagney plain, uncovering significant coal seams. On August 28, 1845, a prefectoral decree authorized the digging of shaft no. 8.[2]

Sinking

[edit]

Sinking of the shaft began on September 11, 1845, with a rectangular cross-section measuring 4.64 meters × 2.14 meters; the extraction chamber measures 1.70 meters × 1.76 meters.[2] By the end of 1846, it had reached a depth of 180 meters. A 60-hp steam engine was installed. On August 19, 1847, at a depth of 225.80 meters, the first layer was encountered, with a thickness of 2.50 meters of pure coal.[3]

To exploit the first layer immediately, the company uses the “sous stot” digging technique: a second shaft is dug parallel to the main shaft from the first layer. Once the intermediate layer has been reached, a gallery is dug under the main shaft and continues to the second layer. When both sections are completed, a junction is made. Digging lasted from September 1847 to April 1848.[4]

Operation

[edit]

In 1848, a steam engine consisting of a single vertical cylinder with a diameter of 49 centimeters and a stroke of 1.356 meters was installed. This was a Meyer machine manufactured in the Expansion workshops, with a flywheel six meters in diameter. The extraction machine's pendulum is supported by two cast-iron columns, and vertical guides frame the piston. The manual braking system was replaced by a steam brake. The machine is rated at 60 hp6. The extraction compartment has only two guides, and the cages slide on either side of them. The cages can only hold one 315-kg carriage. Rolling is carried out by wheelbarrow in the galleries and with carts on cast-iron or wooden rails. In the same year,[notes 1] a large 700-metre-long inclined plane was built to follow the coal bed.[5]

In 1850, 57,413 tonnes of coal were extracted from the bowels of the Saint-Charles shaft. The latter exploited some of the most important veins in the Ronchamp coalfields, including a four-metre-thick layer in 1862 and a three-metre-thick layer discovered four years later.[6] In June 1861, the Saint-Charles pit continued to operate without interruption, extracting 2,585 tonnes of coal. However, this was no longer the most productive pit, as the Saint-Joseph pit extracted 6,258 tonnes and the Sainte-Barbe pit 2,622 tonnes in the same month.[7] Production amounted to 24,292.[7] tons in 1861, 30,205.7 tons in 1862 and 67,036 tons in 1863.[8]

In 1868, the most important part of the second layer was mined and production reached 100 tonnes per day. At the same time, the link with the Sainte-Marie shaft was completed, facilitating ventilation.[9] By 1873, all mining at the Saint-Charles shaft was taking place in the second layer on floors 260 and 315, and consideration was being given to mining the intermediate layer (located between the first and second layers).[9] Three years later, in January, 2,610 tonnes of coal, 550 cubic metres of water and 673 tonnes of spoil were brought up from the shaft.[9] In 1877, a telephone was installed to communicate with the bottom of the shaft.[10]

The cleat machine

[edit]

By 1849, operations at the Saint-Charles shaft gradually expanded to the south, east, and west. The company considered sinking another well (the Saint-Joseph well, which would be sunk the following year), but sinking a well can take five to six years, and the company needed immediate resources. It therefore decided to sink an inclined plane at the same time as the Saint-Joseph shaft, to reach the area to be mined more quickly. The breakthrough of this descending gallery began in December 1849. It was initially equipped with a horse-drawn carousel, but this system was not sufficiently efficient, so the engineers thought of a new mining system: the cleat machine.[11]

A cleat machine has already been installed at the bottom of Compagnie des Mines d'Anzin's Davy pit in La Sentinelle, in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais coalfield, and the collieries have decided to use the same system at Ronchamp. Initially, a single circuit is to start from the Saint-Joseph shaft, then follow the inclined plane before climbing back up through the Saint-Charles shaft.[12]

In 1850, more than 200 meters below the surface, a steam engine and two boilers were installed in a large room close to the coal beds. The room, 50 meters from the shaft, is 17 meters long, 8 meters wide, and 4 meters high, and is supported by a massive oak framework, some parts of which are 40 cm square. This steam engine powers the cleat machine installed in the 700-meter-long inclined plane. The underground machines and boilers were supplied by Sthelier of Thann, as were the engine and all the cleat equipment for the vertical shaft. These elements were installed and ready for use on May 20, 1852. Until 1853, major mechanical operating problems were encountered, but these were resolved as testing progressed. Engineer Schutz was one of the instigators of this initiative, the machinery having been invented by Mr. Mehus 1. Conversely, engineer Francois Mathet, who joined the company in 1855, was highly critical of the system and its adoption, finding it dangerous for miners' lives due to the drought that could disrupt ventilation and even cause firedamp. He also described the fragility of the woodwork and the high temperatures the drivers had to endure.[13] On October 19, the underground boilers were lit, but immediately the fire, fanned by the 250-meter-high chimney, sucked all the air out of the mine. As a result, ventilation was difficult, and the workings were invaded by firedamp. On March 12, 1853, the inclined plane's cleat machine was put into operation. The water accumulated at the bottom of the large chute is evacuated by hand pumps installed at the top and bottom of the inclined plane over 200 meters. These pumps were operated by women. But on April 1, despite all the precautions taken, a fire broke out in the woods near the boilers.[6]

In 1855 and again in 1856, the Saint-Charles shaft produced 54,081 tonnes of coal thanks to the cleat machine. That same year, however, the decision was made to abandon this machine. At the same time, the women were dismissed from mine 1. The following year, the machine was dismantled and replaced by a wheel mining machine. This set in motion two cables, one ascending, the other descending, and vice-versa. Each cable was guided by two parallel wooden sills.[14]

In May 1852, a second machine of the same type, but vertical, was put into service over the entire height of the shaft, replacing the Meyer coil machine. It too suffered numerous breakdowns, requiring frequent shutdowns to readjust various parts over several months and in the years that followed. Finally, on March 29, 1857, the Board of Directors decided to return to the cable extraction system, and the vertical cleat machine was dismantled in 48 days, starting the following May 17. A 9-meter-high wooden headframe was built over the shaft, and the Meyer machine was refurbished.[15]

Accidents and disasters

[edit]

Three firedamp blasts occurred in 1857: eight miners perished on January 29, two on March 3, and two on March 14.[6] On March 16, the entire workforce went on strike of these disasters. The shaft was deemed too dangerous, with poor ventilation and faulty equipment. The management lodged a complaint for coalition offenses, but the Haute-Saône prefecture ruled in favor of the miners, and the engineer was sentenced to prison for flagrant breaches of safety.[16]

On November 8, 1857, a fire broke out in the underground boiler room. The openings of shafts no. 7 and Saint-Charles are hermetically sealed. On January 18 the following year, a dog and a lighted lamp descended to the bottom of the shaft to test for the presence of a firedamp. On January 30, the openings in both shafts were reopened. However, energetic ventilation rekindled the fire in the coal. In 1859, water flooded the mine after more than six months of inactivity.[6]

In 1886, the shaft was bricked up from top to bottom, with a diameter of 3.30 meters. At the bottom, for the first time in Ronchamp, metal frames were installed over a kilometer of the gallery. Unfortunately, in June of the same year, another firedamp explosion killed twenty-three people.[6]

The ending

[edit]After the 1886 disaster, a large part of the galleries and the construction site were destroyed, in addition, forty years of intensive mining had greatly depleted the deposit, leaving the shaft virtually abandoned. But three years later, strong demand for coal prompted the company to rehabilitate the entire site and resume mining.[17]

In 1891, the pit was fitted out to accommodate around a hundred workers, but two years later, work was again halted, and only water was brought up from the shaft.[18] The following year, mining was resumed to remove the remains of coal panels,[notes 2] estimated to weigh 10,000 tonnes. They were excavated at a rate of 100 tonnes per day by around one hundred workers.[18] In October 1895, the workers completed the stripping[notes 3] and proceeded with the clearing.[notes 4] This work was completed in December of the same year. The shaft was then backfilled.[18]

Conversion

[edit]The shaft was backfilled from January to June 1896 at around ten carloads of shale per day. In May, an eight-meter-thick plug of clay and concrete was installed to make the shaft watertight.[19] The surface installations were demolished, except the machine building, which was converted into housing, and another building which housed accommodation and the “La Ruche” store.[20] The adjacent store was demolished in 2005 after being destroyed by fire.[21]

At the beginning of the 21st century, several of the pit's buildings still stand, including the well-preserved mining machine building, repainted white, and the large building housing the mine masters and the canteen. All these buildings have now been converted into housing.[22]

-

The floor of the Saint-Charles well in 2015.

-

Area where the well is located.

Mining town and shops

[edit]47°42′09″N 6°39′11″E / 47.702515°N 6.653095°E

In 1866, a food and clothing store was built on the site of the Saint-Charles well, next to the offices. It was later expanded to include a bakery and butcher's shop, and named “La Ruche”. The store was run by the company, and miners' purchases were deducted directly from their wages via their order and payroll books. After the Second World War, the store became a cooperative limited company with shares on the stock exchange.[20]

To accommodate the large workforce employed at the Saint-Charles shaft, a mining housing estate was built in 1872, a few dozen meters from the pithead. It consisted of four houses built of roughcast sandstone rubble, each with a single storey and long-sloped mechanical tile roofs.[23][24][25] Although the collieries had originally intended to build 24 dwellings, they had to give up for financial reasons. Each house is divided into four units, with two bedrooms, a kitchen, a cellar, an attic, and a garden for each family.[23] On March 11, 2010, the houses were listed in the general inventory of cultural heritage.[24]

The slag heap

[edit]The “terril du puits Saint-Charles” is a fairly extensive flat slag heap where waste rock has been piling up for half a century. Between 1926 and 1931, the slag heap's shales were sorted at the coal washing center to extract the remaining coal that was used as fuel for the boilers installed on the Chanois plain.[26]

In June 1993, the 15-metre-high slag heap containing 35,000 m3 of shale caught fire. A neighboring plant (MagLum) had previously buried waste such as zinc, cyanide, nickel, sulfur, polyurethane foam, hydrogen sulfide, phenols and hydrocarbon derivatives there. Thick black smoke billowed over the communes of Ronchamp and Champagney, causing concern and mobilizing the population. Gas analyses and health monitoring of children were carried out (27 of them complained of various symptoms: vomiting, nausea, headaches, throat and eye irritations). Analyses revealed heavy metal content (including aluminum) 750 times higher than the norm, as well as traces of trichloroethylene and nitrate vapors. Despite the intervention of the fire department and the installation of firebreak trenches and barriers, the fire persisted for months.[27][26][28] Part of the slag heap had to be moved in 1994 to extinguish it. The slag heap was then used as backfill for a road.[29] The Saint-Charles pit still has a large slag heap, even though a large part of it was removed during the fire.[24]

-

General aerial view of the slag heap, shaft buildings and large offices.

-

View of the slag heap.

-

The summit.

Workshops and offices

[edit]

47°42′09″N 6°39′11″E / 47.702515°N 6.653095°E

Shortly after the opening of the shaft and its good results, the company decided to set up its central workshops and offices next to the shaft and established a link with the rail network. These facilities remained the nerve center of the collieries until their closure in 1958.[30] The site was converted into a car manufacturing subcontracting plant before being decommissioned in 2008. At the beginning of the 21st century, the site was used for exhibitions and shooting games.

The station

[edit]

47°42′12″N 6°39′12″E / 47.703343°N 6.653262°E

Once the coal carts have been hauled up from the Saint-Charles shaft, they are emptied into large wagons. The wagons are transferred to a station close to the shaft via a railroad built in 1858, before the coal is shipped to the coal mine's customers, most of whom are from Alsace, via the Paris-Est to Mulhouse-Ville railroad.[31]

The station was in operation from the mid-19th century until 1958, when the mines closed, after which it was dismantled. At the beginning of the 21st century, the station site was overgrown, and only a few remnants of the installations and network remained.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Parietti (2001, p. 17)

- ^ a b Mathet (1882, pp. 137 144)

- ^ Parietti (1999, p. 3)

- ^ Parietti (1999, p. 4)

- ^ Parietti (1999, p. 5)

- ^ a b c d e "Les puits creusés dans le bassin houiller de ronchamp". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-07.

- ^ a b Parietti (1999, p. 34)

- ^ Godard (2012, p. 336)

- ^ a b c Parietti (1999, p. 35)

- ^ Parietti (1999, p. 36)

- ^ Parietti (1999, p. 8)

- ^ Parietti (1999, pp. 8–9)

- ^ Mathet (1882, pp. 139–140)

- ^ Parietti (1999, p. 7)

- ^ Mathet (1882, pp. 141–173)

- ^ Parietti (2010, p. 91)

- ^ Parietti (1999, p. 39)

- ^ a b c Parietti (1999, p. 40)

- ^ Parietti (1999, pp. 40–55)

- ^ a b PNRBV (1999, p. 24)

- ^ "Ancien magasin La Ruche". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ "Le puits Saint Charles". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ a b PNRBV (1999, p. 25)

- ^ a b c "Le terril de Saint Charles". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-07.

- ^ "La cité Saint Charles". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ a b Parietti (1999, p. 41)

- ^ "Le feu dans le terril de Saint Charles". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ "La psychose d'un ancien village minier face au terril en feu depuis neuf mois - L'Humanité". humanité (in French). 1994-02-07. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ "Enlèvement des schistes brûlants". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ "Les ateliers de réparation des mines". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ "Le réseau ferré entre les puits". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Jacking” involves digging a mine shaft from the surface. By extension, any excavation of a steeply inclined structure can be described as jacking. This includes not only the excavation, but also the removal of spoil and the initial lining.

- ^ The panels are large-area pillars or unused mine areas.

- ^ When a mine or shaft is mined, galleries are dug in a checkerboard pattern to extract the coal, forming regular, square natural pillars. When all the galleries have been dug, these pillars, which contain a lot of coal, are removed. This is known as “de-piling”.

- ^ When digging the galleries, natural pillars are not enough, so wooden beams are installed. At the end of the operation, they are reclaimed. This is known as “deforestation”.

Bibliography

[edit]- Parietti, Jean-Jacques (2001). Les Houillères de Ronchamp. Éditions Comtoises. ISBN 2-914425-08-2.

- Parietti, Jean-Jacques (2010). Les Houillères de Ronchamp, vol. 2: Les mineurs. Franche-Comté culture & patrimoine. ISBN 978-2-36230-001-1.

- Parietti, Jean-Jacques (1999). Le puits Saint-Charles, coll. Les dossiers de la Houillère. Ronchamp, Association des amis du musée de la mine.

- Mathet, François (1882). Mémoire sur les mines de Ronchamp. Société de l'industrie minérale. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- PNRBV (1999). Le charbon de Ronchamp : circuits miniers de Ronchamp, coll. « Déchiffrer le patrimoine ». Parc naturel régional des Ballons des Vosges. ISBN 2-910328-31-7.

- Société de l'industrie minérale, Bulletin trimestriel. Saint-Étienne. 1882.

- Thirria, Édouard (1869). Manuel à l'usage de l'habitant du département de la Haute-Saône.

- Godard, Michel (2012). Enjeux et impacts de l'exploitation minière du bassin houiller de Ronchamp.