Beatrizsborges (talk | contribs) |

DuncanHill (talk | contribs) Fix harv/sfn no-target errors |

||

| (82 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description| |

{{Short description|French coal mine shaft}} |

||

{{Infobox mine|name=Saint-Charles shaft|image=1880 - Puits Saint-Charles.jpg|caption=surface installations|location=Bourgogne-Franche-Comté|country=[[France]]|type=shaft|opening year=September 14, 1845|active years=August 19, 1847}} |

|||

| name = Lille 3000 |

|||

The '''Saint-Charles shaft''' (or No. 8 shaft) is one of the main collieries of the [[Ronchamp coal mines|Ronchamp coal mine]]. It is located in [[Ronchamp]], [[Haute-Saône]], in eastern France. In the second half of the nineteenth century, this shaft made it possible to mine large coal seams, contributing to the company's golden age. |

|||

| logo = Lille3000 |

|||

| type = Event |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Lille 3000''' is an association representing a cultural program promoted by the city of Lille and the Lille 2004 organizing committee. |

|||

Saint-Charles has been open for over fifty years, a long life compared to other open shafts in the Ronchamp mining basin. It has also experienced mining disasters such as fires and firedamp blasts. The shaft is distinguished by its revolutionary extraction system using a cleat machine. The process, too complex, was eventually abandoned following technical setbacks. |

|||

Lille 3000 is intended as a continuation of the dynamism instilled by Lille in 2004 as European Capital of Culture. |

|||

After closure, the pit buildings were converted into housing; the slag heaps were re-used between the wars, as they were still rich in coal. At the end of the twentieth century, these same slag heaps, which had become a dumping ground for a nearby factory, burst into flames, frightening the local population. |

|||

Lille 3000 reuses the cultural venues created or renovated for Lille 2004 (Tri Postal, Maisons Folies etc.); but also creates new ones (rehabilitation of the former Saint Sauveur goods station, which became a cultural center in 2009, etc.). |

|||

== Situation before sinking == |

|||

Together with the city, the association manages several of the cultural facilities mentioned above, and regularly organizes a wide range of activities, metamorphoses, shows and exhibitions. |

|||

After the Saint-Louis shaft was sunk in the hamlet of La Houillère in 1810, the company dug a series of shafts close to the outcrops, varying in depth from 19 to 165 meters. But the last shafts dug around 1830, found no coal. Shaft no. 5, continued by drilling, found no trace of coal, and shaft no. 6 stumbled on an uplift in the coalfield linked to a fault. In 1839, shaft no. 7 was sunk in search of coal. However, with the company bankrupt, the concession was put up for sale and the sinking stopped. |

|||

In 1843, Charles Demandre and Joseph Bezanson bought the Ronchamp concession and continued sinking shaft no. 7. They finally found coal at 205 meters, behind the uplift.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|2001|p=17}}</ref> Shortly after the No. 7 shaft was commissioned, borehole X was drilled on the Champagney plain, uncovering significant coal seams. On August 28, 1845, a prefectoral decree authorized the digging of shaft no. 8.<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

Every three years or so since 2006, Lille 3000 has also presented a series of major themed cultural events (cultural seasons) lasting several months and attracting millions of visitors, under the artistic direction of Didier Fusillier. These events open with a grand parade through the streets of Lille. |

|||

== |

== Sinking == |

||

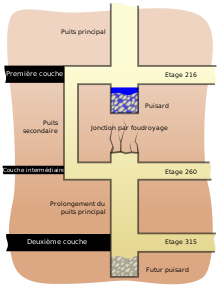

[[File:Fonçage puits Saint-Charles sous stot.svg|left|thumb|The “under stot” sinking method.]] |

|||

Sinking of the shaft began on September 11, 1845, with a rectangular cross-section measuring 4.64 meters × 2.14 meters; the extraction chamber measures 1.70 meters × 1.76 meters.<ref name=":1">{{Harvtxt|Mathet|1882|pp=137 144}}</ref> By the end of 1846, it had reached a depth of 180 meters. A 60-hp steam engine was installed. On August 19, 1847, at a depth of 225.80 meters, the first layer was encountered, with a thickness of 2.50 meters of pure coal.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=3}}</ref> |

|||

To exploit the first layer immediately, the company uses the “sous stot” digging technique: a second shaft is dug parallel to the main shaft from the first layer. Once the intermediate layer has been reached, a gallery is dug under the main shaft and continues to the second layer. When both sections are completed, a junction is made. Digging lasted from September 1847 to April 1848.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=4}}</ref> |

|||

=== Bombayser de Lille === |

|||

[[File:2 éléphants à la mairie de lille - Lille 3000.JPG|thumb]] |

|||

The main theme of Lille 3000's first cultural season, which ran from October 14 2006 to January 14 2007, was India, at the crossroads of art and modernity. It involved the organization of 450 events, including music, cinema, theater, dance, meetings, and exhibitions, attracting nearly a million visitors1. |

|||

== Operation == |

|||

The Lille 3000 themes related to India were divided into several distinct categories, each held at different venues according to a calendar2 ; |

|||

[[File:Plan Puits Saint-Charles 1.jpg|thumb|280x280px|Plan of Saint-Charles well facilities.]] |

|||

In 1848, a steam engine consisting of a single vertical cylinder with a diameter of 49 centimeters and a stroke of 1.356 meters was installed. This was a Meyer machine manufactured in the Expansion workshops, with a flywheel six meters in diameter. The extraction machine's pendulum is supported by two cast-iron columns, and vertical guides frame the piston. The manual braking system was replaced by a steam brake. The machine is rated at 60 hp6. The extraction compartment has only two guides, and the cages slide on either side of them. The cages can only hold one 315-kg carriage. Rolling is carried out by wheelbarrow in the galleries and with carts on cast-iron or wooden rails. In the same year,<ref group="notes">Jacking” involves digging a mine shaft from the surface. By extension, any excavation of a steeply inclined structure can be described as jacking. This includes not only the excavation, but also the removal of spoil and the initial lining.</ref> a large 700-metre-long inclined plane was built to follow the coal bed.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=5}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Plan Puits Saint-Charles 2.jpg|left|thumb|300x300px|Floor plan of the Saint-Charles: canteen and porter's quarters; weighbridge; administration; old boilers and machine; large chimney; coils; new machine; and c. boilers added during expansions; lamp house; well; smoke channel; thick dividing wall. ]] |

|||

In 1850, 57,413 tonnes of coal were extracted from the bowels of the Saint-Charles shaft. The latter exploited some of the most important veins in the Ronchamp coalfields, including a four-metre-thick layer in 1862 and a three-metre-thick layer discovered four years later.<ref name=":2">{{Cite web |title=Les puits creusés dans le bassin houiller de ronchamp |url=http://www.abamm.org/lespuits.html |access-date=2024-05-07 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref> In June 1861, the Saint-Charles pit continued to operate without interruption, extracting 2,585 tonnes of coal. However, this was no longer the most productive pit, as the Saint-Joseph pit extracted 6,258 tonnes and the Sainte-Barbe pit 2,622 tonnes in the same month.<ref name=":3">{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=34}}</ref> Production amounted to 24,292.<ref name=":3" /> tons in 1861, 30,205.7 tons in 1862 and 67,036 tons in 1863.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Godard|2012|p=336}}</ref> |

|||

In 1868, the most important part of the second layer was mined and production reached 100 tonnes per day. At the same time, the link with the Sainte-Marie shaft was completed, facilitating ventilation.<ref name=":0">{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=35}}</ref> By 1873, all mining at the Saint-Charles shaft was taking place in the second layer on floors 260 and 315, and consideration was being given to mining the intermediate layer (located between the first and second layers).<ref name=":0" /> Three years later, in January, 2,610 tonnes of coal, 550 cubic metres of water and 673 tonnes of spoil were brought up from the shaft.<ref name=":0" /> In 1877, a telephone was installed to communicate with the bottom of the shaft.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=36}}</ref> |

|||

* Music |

|||

* Film, literature and fashion |

|||

* Exhibitions |

|||

* Theater |

|||

* Dance |

|||

* Maisons Folie |

|||

* Midi Midi |

|||

* Metamorphosis |

|||

== The cleat machine == |

|||

[[File:Machine à tacquet 02.jpg|thumb|Plans of the bottom of the shaft. 1: ground plan of the galleries, 2: plan of the brick dams, 3: cross-section of the shaft.]] |

|||

[[File:Lille 3000 drapeaux.jpg|thumb]] |

|||

By 1849, operations at the Saint-Charles shaft gradually expanded to the south, east, and west. The company considered sinking another well (the Saint-Joseph well, which would be sunk the following year), but sinking a well can take five to six years, and the company needed immediate resources. It therefore decided to sink an inclined plane at the same time as the Saint-Joseph shaft, to reach the area to be mined more quickly. The breakthrough of this descending gallery began in December 1849. It was initially equipped with a horse-drawn carousel, but this system was not sufficiently efficient, so the engineers thought of a new mining system: the cleat machine.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=8}}</ref> |

|||

The second season of Lille 3000, entitled Europe XXL, ran from March 14 to July 12, 2009. Its main theme was Eastern Europe, to mark the twentieth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. It led to the organization of around 500 events and some 50 exhibitions, and attracted almost a million visitors1. |

|||

A cleat machine has already been installed at the bottom of Compagnie des Mines d'Anzin's Davy pit in La Sentinelle, in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais coalfield, and the collieries have decided to use the same system at Ronchamp. Initially, a single circuit is to start from the Saint-Joseph shaft, then follow the inclined plane before climbing back up through the Saint-Charles shaft.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|pp=8-9}}</ref> |

|||

=== Fantastic === |

|||

[[File:Machine à tacquet 01.png|thumb|292x292px|The cleat machine.]] |

|||

Lille 3000's third season ran from October 6, 2012 to January 13, 2013. Its theme was the world of the supernatural, the fantastic and the strange. It attracted almost two million visitors3. |

|||

In 1850, more than 200 meters below the surface, a steam engine and two boilers were installed in a large room close to the coal beds. The room, 50 meters from the shaft, is 17 meters long, 8 meters wide, and 4 meters high, and is supported by a massive oak framework, some parts of which are 40 cm square. This steam engine powers the cleat machine installed in the 700-meter-long inclined plane. The underground machines and boilers were supplied by Sthelier of Thann, as were the engine and all the cleat equipment for the vertical shaft. These elements were installed and ready for use on May 20, 1852. Until 1853, major mechanical operating problems were encountered, but these were resolved as testing progressed. Engineer Schutz was one of the instigators of this initiative, the machinery having been invented by Mr. Mehus 1. Conversely, engineer Francois Mathet, who joined the company in 1855, was highly critical of the system and its adoption, finding it dangerous for miners' lives due to the drought that could disrupt ventilation and even cause firedamp. He also described the fragility of the woodwork and the high temperatures the drivers had to endure.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Mathet|1882|pp=139-140}}</ref> On October 19, the underground boilers were lit, but immediately the fire, fanned by the 250-meter-high chimney, sucked all the air out of the mine. As a result, ventilation was difficult, and the workings were invaded by firedamp. On March 12, 1853, the inclined plane's cleat machine was put into operation. The water accumulated at the bottom of the large chute is evacuated by hand pumps installed at the top and bottom of the inclined plane over 200 meters. These pumps were operated by women. But on April 1, despite all the precautions taken, a fire broke out in the woods near the boilers.<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

In 1855 and again in 1856, the Saint-Charles shaft produced 54,081 tonnes of coal thanks to the cleat machine. That same year, however, the decision was made to abandon this machine. At the same time, the women were dismissed from mine 1. The following year, the machine was dismantled and replaced by a wheel mining machine. This set in motion two cables, one ascending, the other descending, and vice-versa. Each cable was guided by two parallel wooden sills.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=7}}</ref> |

|||

In addition to several shows and events, the season included installations throughout the city and numerous exhibitions in the metropolis' main museums4. |

|||

In May 1852, a second machine of the same type, but vertical, was put into service over the entire height of the shaft, replacing the Meyer coil machine. It too suffered numerous breakdowns, requiring frequent shutdowns to readjust various parts over several months and in the years that followed. Finally, on March 29, 1857, the Board of Directors decided to return to the cable extraction system, and the vertical cleat machine was dismantled in 48 days, starting the following May 17. A 9-meter-high wooden headframe was built over the shaft, and the Meyer machine was refurbished.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Mathet|1882|pp=141-173}}</ref> |

|||

=== Renaissance === |

|||

Lille 3000's fourth season kicked off on September 26, 2015, inaugurated by a grand parade through the streets of Lille. This season aimed to showcase the vitality of the contemporary world, via numerous exhibitions and urban metamorphoses. The beginning of the 21st century embodies a turbulent era from which a new world is emerging, embodied here by major cities; represented for this edition were Rio, Detroit, Eindhoven, Phnom Penh and Seoul. |

|||

=== Accidents and disasters === |

|||

Renaissance attracted 1.6 million visitors. |

|||

[[File:Puits Saint-Charles XXe - 03.JPG|thumb|Miners in the shaft around 1880.]] |

|||

Three firedamp blasts occurred in 1857: eight miners perished on January 29, two on March 3, and two on March 14.<ref name=":2" /> On March 16, the entire workforce went on strike of these disasters. The shaft was deemed too dangerous, with poor ventilation and faulty equipment. The management lodged a complaint for coalition offenses, but the [[Haute-Saône]] prefecture ruled in favor of the miners, and the engineer was sentenced to prison for flagrant breaches of safety.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|2010|p=91}}</ref> |

|||

On November 8, 1857, a fire broke out in the underground boiler room. The openings of shafts no. 7 and Saint-Charles are hermetically sealed. On January 18 the following year, a dog and a lighted lamp descended to the bottom of the shaft to test for the presence of a firedamp. On January 30, the openings in both shafts were reopened. However, energetic ventilation rekindled the fire in the coal. In 1859, water flooded the mine after more than six months of inactivity.<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

=== Eldorado === |

|||

Lille 3000's fifth season runs from April to December 2019 on the theme of Mexico. Eldorado attracted over 2.5 million visitors5.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2019-05-07 |title=Eldorado lille3000 — Parade |url=https://www.eldorado-lille3000.com/en/parade-2/ |access-date=2024-04-29 |website=www.eldorado-lille3000.com |language=en-GB}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Lille3000 Parade Eldorado.jpg|center|thumb]] |

|||

In 1886, the shaft was bricked up from top to bottom, with a diameter of 3.30 meters. At the bottom, for the first time in Ronchamp, metal frames were installed over a kilometer of the gallery. Unfortunately, in June of the same year, another firedamp explosion killed twenty-three people.<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

=== The Great Eldorado Parade === |

|||

=== The ending === |

|||

After the 1886 disaster, a large part of the galleries and the construction site were destroyed, in addition, forty years of intensive mining had greatly depleted the deposit, leaving the shaft virtually abandoned. But three years later, strong demand for coal prompted the company to rehabilitate the entire site and resume mining.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=39}}</ref> |

|||

This parade was composed mainly of five floats. There were many elements of the 2018 Fiesta de los Muertos sent by Mexico; but also harmonies, amateur participants and professional companies invited for the occasion. Four floats were imagined, decorated and orchestrated by Roubaix-based collective Art Point M: the Dia de los Muertos float featuring mariachis; the [[Frida Kahlo|Frida-Khalo]] float; the Alebrijes float accompanied by Compagnie du Tire-Laine; and the [[Lucha libre|Lucha Libre]] float re-enacting a live wrestling match. |

|||

[[File:Gare Lille Flandres Eldorado 2019 mai 04.jpg|thumb|One of the ten alebrijes stands vigil in front of Lille Flandres station. These fantastic creatures were created by Pedro Linares López in 1936. Alebrijes are statues made of wood or papier-mâché. Rue Faidherbe is home to ten of these monumental sculptures, created in partnership with artisans from Mexico City's Museum of Popular Art, the City of Mexico (Artsumex), Mexico City's El Volador workshops and lille3000.]] |

|||

In all, a dozen bands and 3,000 dancers, musicians and people in make-up or disguises [ref. needed] paraded around the floats in Mexican colors.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2019-05-01 |title=Lille 3000 Eldorado: A Year-Long Cultural Extravaganza in the North of France |url=https://francetoday.com/culture/art_and_design/lille-3000-eldorado-a-year-long-cultural-extravaganza/ |access-date=2024-04-29 |website=France Today}}</ref> |

|||

In 1891, the pit was fitted out to accommodate around a hundred workers, but two years later, work was again halted, and only water was brought up from the shaft.<ref name=":4">{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=40}}</ref> The following year, mining was resumed to remove the remains of coal panels,<ref group="notes">The panels are large-area pillars or unused mine areas.</ref> estimated to weigh 10,000 tonnes. They were excavated at a rate of 100 tonnes per day by around one hundred workers.<ref name=":4" /> In October 1895, the workers completed the stripping<ref group="notes">When a mine or shaft is mined, galleries are dug in a checkerboard pattern to extract the coal, forming regular, square natural pillars. When all the galleries have been dug, these pillars, which contain a lot of coal, are removed. This is known as “de-piling”.</ref> and proceeded with the clearing.<ref group="notes">When digging the galleries, natural pillars are not enough, so wooden beams are installed. At the end of the operation, they are reclaimed. This is known as “deforestation”.</ref> This work was completed in December of the same year. The shaft was then backfilled.<ref name=":4" /> |

|||

==== Parade entertainment ==== |

|||

On Saturday, May 4, 2019, the festivities got underway at 3 pm at Tripostal and the Euralille shopping center, where children and adults got ready in make-up, costume, mask, and wreath workshops until 6 pm. And at 3 p.m., a flash mob set the pace in Place du Théâtre, opposite the Lille Opera House. |

|||

==== Musiques de la parade ==== |

|||

During the parade, many artists were present on the floats. On the [[Day of the Dead|Dia de Los Muertos]] (“Day of the Dead”) float, the Mexican music group Mariachi Cocula6 was on hand to entertain the people of Lille along the established route. For the float representing Mexican painter Frida Kahlo, group 4cascabel6 played the Fandango, a musical genre with Latin and African influences. On the Alebrijes float (wooden statues representing fantastic animals and creatures), the Compagnie du Tire-Laine6, an orchestra based in the Moulins district, brought together over sixty musicians. After the parade, they organized a grand ball on the Place du Théâtre at the end of the evening. |

|||

The festivities continued after the parade ended, from 10 pm to 1 am. Musicians from Soundtruck6 and DJ El Frances6 improvised a music studio in a Volkswagen van near Rue Nationale. In the Place du Théâtre, the group Kumbia Boruka6, founded by Hernan Cortes, got the tourists up and dancing with its blend of Mexican accordion and Jamaican reggae. Other groups, such as Mariachi Los Tarasco6 and Theator Tol6, offered songs and music from all over the world. Electro-house music was also in the spotlight on Place Rihour, where DJ Batichica, originally from [[Guadalajara]] in [[Mexico]], presented a set of EDM ([[Electronic dance music|Electronic Dance Music]]). |

|||

==== Parade safety ==== |

|||

Along the entire parade route, between Place des Buisses and Champ de Mars, 250,000 spectators gathered to watch the nearly 800-meter-long procession pass by. The organizers had set up a restricted and regulated traffic and parking plan. A protective perimeter was set up by the national police in downtown Lille from 3 pm to 2 am. Streets affected by the parade were closed to traffic from 6.30 pm to 2 am. In some streets downstream from the starting point, visitors waited for two hours for the parade to pass. Most were on foot along the routes reserved for the floats, which slowed the parade's progress to the Champ de Mars. |

|||

==== Parade postponed ==== |

|||

The parade, scheduled for Saturday, April 27, 2019, has been postponed to Saturday, May 4, 2019, due to weather conditions (forecasts of high winds threatened the smooth running of the parade). The decision was taken on Thursday, April 25 by the lille3000 organization, Lille City Council, and the Nord<ref>{{Cite web |date=2024-04-30 |title=La Voix du Nord |url=https://www.lavoixdunord.fr/ |access-date=2024-04-30 |website=La Voix du Nord |language=fr}}</ref> prefecture. It was the first time in five editions that a lille3000 parade had been postponed. As a result of the postponement, some installations originally scheduled for the parade were not present.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2019-04-25 |title=Lille 3000 Eldorado : quelles conséquences peut avoir le report de la parade d'ouverture ? |url=https://france3-regions.francetvinfo.fr/hauts-de-france/nord-0/lille/lille-3000-eldorado-quelles-consequences-peut-avoir-report-parade-ouverture-1660341.html |access-date=2024-04-30 |website=France 3 Hauts-de-France |language=fr-FR}}</ref> |

|||

== Exhibitions == |

|||

For this season, a number of exhibitions on the theme of El Dorado (myth, travel, migration, nature, etc.) have been set up (see sub-sections below). Other major exhibitions are also on offer at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Lille, the Piscine in Roubaix, the Louvre-Lens and the Frac Grand Large in Dunkirk. |

|||

== Conversion == |

|||

Mexican muralists, the “Tlacolulokos” duo (named after their native village), have been invited to paint three murals in the Mexican tradition, with local inspiration; two exhibitions are devoted to the art of fresco.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Chauffard |first=Coline |date=2019-03-19 |title=Tlacolulokos, des couleurs mexicaines sur les murs lillois |url=https://www.lavoixdunord.fr/554683/article/2019-03-19/tlacolulokos-des-couleurs-mexicaines-sur-les-murs-lillois |access-date=2024-04-30 |website=La Voix du Nord |language=fr}}</ref> |

|||

The shaft was backfilled from January to June 1896 at around ten carloads of shale per day. In May, an eight-meter-thick plug of clay and concrete was installed to make the shaft watertight.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|pp=40-55}}</ref> The surface installations were demolished, except the machine building, which was converted into housing, and another building which housed accommodation and the “La Ruche” store.<ref name=":7">{{Harvtxt|PNRBV|1999|p=24}}</ref> The adjacent store was demolished in 2005 after being destroyed by fire.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Ancien magasin La Ruche |url=http://www.abamm.org/divers02.html |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref> |

|||

=== Eldorama === |

|||

Le Tripostal hosts the Eldorado exhibition from April 27 to September 1, 2019. In three chapters, it retraces the great story of Eldorado. On the second floor, visitors will find the Dream Worlds section. The second floor features The Rush. Finally, on the top floor of the building, visitors can find the section entitled Un eldorado sans fin. Chinese artist [[Chen Zhen (artist)|Chen Zhen]]'s dragon and Japanese artist [[Yayoi Kusama]]'s light piece are also on show11.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2019-04-28 |title=VIDEO. Eldorado-Lille 3000 : l'annulation de la parade n'empêche pas le bon début des festivités |url=https://france3-regions.francetvinfo.fr/hauts-de-france/nord-0/lille/video-eldorado-lille-3000-annulation-parade-n-empeche-pas-bon-debut-festivites-1661469.html |access-date=2024-04-30 |website=France 3 Hauts-de-France |language=fr-FR}}</ref> |

|||

At the beginning of the 21st century, several of the pit's buildings still stand, including the well-preserved mining machine building, repainted white, and the large building housing the mine masters and the canteen. All these buildings have now been converted into housing.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Le puits Saint Charles |url=http://www.abamm.org/stcharle.html |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref><gallery mode="packed" widths="280"> |

|||

=== Intenso/Mexicano === |

|||

File:Puits Saint-Charles 2015.JPG|The floor of the Saint-Charles well in 2015. |

|||

In this exhibition at the Hôtel de l'Hospice Comtesse from April 27 to August 30, 2019, visitors can discover works by the great names of Mexican art: [[Frida Kahlo]], [[Diego Rivera]], [[José Clemente Orozco]] and [[Manuel Álvarez Bravo]]. In all, 48 paintings, prints, and photographs from the permanent collection of Mexico City's [[Museo de Arte Moderno]]. The exhibition covers the Mexican 20th century. |

|||

File:Puits Saint-Charles 2013 (2).JPG|Area where the well is located. |

|||

=== US-Mexico/Border === |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

From April 27 to July 28, Maison Folie in Wazemmes will be exhibiting “the work of contemporary artists who explore the border as both a physical reality and a subject of imagination and experimentation, enabling projects to emerge and solutions to be found”. The exhibition was previously presented in Los Angeles, at the Craft & Folk Art Museum. Drawings, architecture, sculpture, painting, and photography are on show, demonstrating the crossover between the different disciplines. |

|||

=== The Green Goddess === |

|||

== Mining town and shops == |

|||

From April 27 to November 3, 2019, the Gare Saint Sauveur is hosting the “La Déesse Verte” exhibition, which draws a parallel between art and nature. A vast greenhouse has been reconstituted and embellished by the works of some twenty artists, who raise issues such as the overexploitation of nature and the effects of the human kingdom on the ecosystem. |

|||

{{coord|47.702515|6.653095|scale:1000_region:FR|name=Ateliers centraux et bureaux}} |

|||

=== Curiosity === |

|||

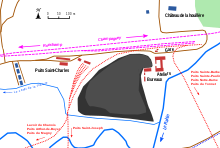

[[File:Plan Puits Saint-Charles - annexes - terrils - cités.svg|thumb|The environment of the Saint-Charles well and its ancillary facilities.{{Legend|black|slag heaps}}{{Legend|#800000|Mine buildings}}{{Legend|#004080|Mining town}}{{Legend|red|Coal mining network|outline=red dotted}}{{Legend|blue|Line from Vesoul to Plancher-les-Mines Chemins de fer vicinaux de la Haute-Saône}}{{Legend|pink|Ligne de Paris-Est à Mulhouse-Ville Compagnie des chemins de fer de l'Est then Société nationale des chemins de fer français}}]] |

|||

From April 27 to July 13, 2019, Lille's natural history museum is exhibiting collections from Mexico City's Museum of Popular Art, referring to Mexico's traditional culture and imaginary world. |

|||

In 1866, a food and clothing store was built on the site of the Saint-Charles well, next to the offices. It was later expanded to include a bakery and butcher's shop, and named “La Ruche”. The store was run by the company, and miners' purchases were deducted directly from their wages via their order and payroll books. After the [[World War II|Second World War]], the store became a cooperative limited company with shares on the stock exchange.<ref name=":7" />[[File:Cité minière Saint-Charles.JPG|left|thumb|Saint-Charles housing estate.]]To accommodate the large workforce employed at the Saint-Charles shaft, a mining housing estate was built in 1872, a few dozen meters from the pithead. It consisted of four houses built of roughcast sandstone rubble, each with a single storey and long-sloped mechanical tile roofs.<ref name=":5">{{Harvtxt|PNRBV|1999|p=25}}</ref><ref name=":6" /><ref>{{Cite web |title=La cité Saint Charles |url=http://www.abamm.org/citeou04.html |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref> Although the collieries had originally intended to build 24 dwellings, they had to give up for financial reasons. Each house is divided into four units, with two bedrooms, a kitchen, a cellar, an attic, and a garden for each family.<ref name=":5" /> On March 11, 2010, the houses were listed in the general inventory of cultural heritage.<ref name=":6" /> |

|||

== Public installations == |

|||

=== Alebrijes === |

|||

== The slag heap == |

|||

In front of Lille Flandres station, rue Faidherbe, ten large-format alebrijes - statues of half-real, half-fantastic animals from Mexican folklore - have been installed. Installed at the end of April, they will remain there for 8 months until December. |

|||

The “terril du puits Saint-Charles” is a fairly extensive flat slag heap where waste rock has been piling up for half a century. Between 1926 and 1931, the slag heap's shales were sorted at the coal washing center to extract the remaining coal that was used as fuel for the boilers installed on the Chanois plain.<ref name=":8">{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=41}}</ref> |

|||

=== Calaveras === |

|||

Giant skulls, or Calaveras, manufactured by an undertaker, have been painted and decorated by Mexican artists and placed around town, mainly in the garden of the Ilot Comtesse. |

|||

In June 1993, the 15-metre-high slag heap containing 35,000 m<sup>3</sup> of shale caught fire. A neighboring plant (MagLum) had previously buried waste such as zinc, cyanide, nickel, sulfur, polyurethane foam, hydrogen sulfide, phenols and hydrocarbon derivatives there. Thick black smoke billowed over the communes of [[Ronchamp]] and [[Champagney, Haute-Saône|Champagney]], causing concern and mobilizing the population. Gas analyses and health monitoring of children were carried out (27 of them complained of various symptoms: vomiting, nausea, headaches, throat and eye irritations). Analyses revealed heavy metal content (including aluminum) 750 times higher than the norm, as well as traces of trichloroethylene and nitrate vapors. Despite the intervention of the fire department and the installation of firebreak trenches and barriers, the fire persisted for months.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Le feu dans le terril de Saint Charles |url=http://www.abamm.org/terris11.html |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref><ref name=":8" /><ref>{{Cite web |date=1994-02-07 |title=La psychose d'un ancien village minier face au terril en feu depuis neuf mois - L'Humanité |url=https://www.humanite.fr/-/-/la-psychose-dun-ancien-village-minier-face-au-terril-en-feu-depuis-neuf-mois |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=humanité |language=fr-FR}}</ref> Part of the slag heap had to be moved in 1994 to extinguish it. The slag heap was then used as backfill for a road.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Enlèvement des schistes brûlants |url=http://www.abamm.org/terris12.html |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref> The Saint-Charles pit still has a large slag heap, even though a large part of it was removed during the fire.<ref name=":6">{{Cite web |title=Le terril de Saint Charles |url=http://www.abamm.org/terris10.html |access-date=2024-05-07 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref><gallery mode="packed" widths="250"> |

|||

=== Monumental chandelier === |

|||

File:2018-03 - Terril Saint-Charles - 01.jpg|General aerial view of the slag heap, shaft buildings and large offices. |

|||

Designed by the Transe Express company, which made its name at the 1992 Albertville Olympic Games, the celestial chandelier is installed in Lille's Grand Palace. Suspended from a crane, it comprises eight branches at the ends of which musicians play, their weight ensuring the stability of the installation. Wind instruments, ground instruments, and frenzied rhythms are on the program, transforming the public square into a ballroom. The suspended orchestra is accompanied by acrobats, who soar several meters high between earth and sky. |

|||

File:2015-11 - Terril Saint-Charles - 14.JPG|View of the slag heap. |

|||

=== Museum Of The Moon === |

|||

File:2015-11 - Terril Saint-Charles - 03.JPG|The summit. |

|||

Located in the heart of [Lille Flandres train station], the Museum Of The Moon is a ten-meter inflatable moon suspended above the ground. It was created by English artist [Luke Gerram] from [NASA] lunar images and will be on view until December 2019. |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

=== Soles de Oro === |

|||

Created by Mexican visual artist [Betsabeé Romero], the Soleils d'or are dozens of mirrors set up in the Old Stock Exchange in the capital of Flanders. Concave in shape and linked together at the height of just a few meters, they produce a variety of light effects, much to the delight of passers-by. |

|||

== Workshops and offices == |

|||

[[File:Ateliers-Bureaux-Ronchamp XXe 01.jpg|thumb|Large offices and workshops.]] |

|||

A mural painted as part of Eldorado on a wall in Lille-Moulins, entitled Hydrates toi d'urbaine liqueur, has been strongly criticized by the Alliance police union. The mural depicted three women in Mexican muralist style, one of whom bore the word ACAB (an acronym for All Cops Are Bastards) on her arm, which the artists said referred to the frequent corruption in the Mexican police force. The artists themselves erased the word ACAB in April 1912. |

|||

{{Coord|47.702515|6.653095}} |

|||

=== Counter-festival === |

|||

Elnorpadcado is a counter-festival organized to protest the 2019 Lille 3000 “Eldorado” edition. It ran from April 26 to December 1, 2019. |

|||

Shortly after the opening of the shaft and its good results, the company decided to set up its central workshops and offices next to the shaft and established a link with the rail network. These facilities remained the nerve center of the collieries until their closure in 1958.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Les ateliers de réparation des mines |url=http://www.abamm.org/ateliers.html |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref> The site was converted into a car manufacturing subcontracting plant before being decommissioned in 2008. At the beginning of the 21st century, the site was used for exhibitions and shooting games. |

|||

The organizers of this counter-festival are protesting against the gigantism of Lille3000 and its cultural seasons, which in their view are not designed for the people of Lille and Northern France, but to attract an essentially foreign audience: “We're simply saying stop, enough is enough! Since 2004, lille3000 has been proposing huge projects, with excessive communication. At this stage, it's perversion! The festival was triggered by a public outcry against the city's incoherence in proposing these outrageous events, while at the same time implementing a much-criticized concreting plan. One project, in particular, has crystallized all the tensions: the rehabilitation of the Friche Saint-Sauveur13 , which will be largely concreted over (notably for the construction of a new swimming pool and housing), while the people of Lille have been calling for more green space for years. |

|||

== The station == |

|||

[[File:Puits Saint-Charles XXe - 01.JPG|thumb|Loading coal wagons at the shaft exit.]] |

|||

{{Coord|47.703343|6.653262}} |

|||

Once the coal carts have been hauled up from the Saint-Charles shaft, they are emptied into large wagons. The wagons are transferred to a station close to the shaft via a railroad built in 1858, before the coal is shipped to the coal mine's customers, most of whom are from [[Alsace]], via the Paris-Est to [[Mulhouse-Ville station|Mulhouse-Ville]] railroad.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Le réseau ferré entre les puits |url=http://www.abamm.org/resferre.html |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref> |

|||

The station was in operation from the mid-19th century until 1958, when the mines closed, after which it was dismantled. At the beginning of the 21st century, the station site was overgrown, and only a few remnants of the installations and network remained. |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

*[[Lille]] |

|||

*[[ |

*[[Ronchamp coal mines]] |

||

*[[ |

*[[Mining in France]] |

||

*[[Sainte-Barbe Coal Mine]] |

|||

*[[Cokerie-lavoir du Chanois]] |

|||

== References == |

== References == |

||

<references /> |

<references /> |

||

== Bibliography == |

|||

* |

|||

== Notes == |

== Notes == |

||

<references group="notes" /> |

<references group="notes" /> |

||

== Bibliography == |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Parietti |first=Jean-Jacques |title=Les Houillères de Ronchamp |date=2001 |publisher=Éditions Comtoises |isbn=2-914425-08-2}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Parietti |first=Jean-Jacques |title=Les Houillères de Ronchamp, vol. 2: Les mineurs |date=2010 |publisher=Franche-Comté culture & patrimoine |isbn=978-2-36230-001-1}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Parietti |first=Jean-Jacques |title=Le puits Saint-Charles, coll. Les dossiers de la Houillère |date=1999 |publisher=Ronchamp, Association des amis du musée de la mine}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Mathet |first=François |url=http://jubilotheque.upmc.fr/ead.html?id=GR_000387_001 |title=Mémoire sur les mines de Ronchamp |date=1882 |publisher=Société de l'industrie minérale |access-date=2024-05-08 |archive-date=2016-03-03 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303201840/http://jubilotheque.upmc.fr/ead.html?id=GR_000387_001 |url-status=dead }} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=PNRBV |title=Le charbon de Ronchamp : circuits miniers de Ronchamp, coll. « Déchiffrer le patrimoine » |date=1999 |publisher=Parc naturel régional des Ballons des Vosges |isbn=2-910328-31-7}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |title=Société de l'industrie minérale, Bulletin trimestriel |date=1882 |publisher=Saint-Étienne}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Thirria |first=Édouard |title=Manuel à l'usage de l'habitant du département de la Haute-Saône |date=1869}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Godard |first=Michel |title=Enjeux et impacts de l'exploitation minière du bassin houiller de Ronchamp |date=2012}} |

|||

[[fr: Puits Saint-Charles]] |

|||

[[Category:Ronchamp coal mines]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 09:21, 30 May 2024

surface installations | |

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Country | France |

| Production | |

| Type | shaft |

| History | |

| Opened | September 14, 1845 |

| Active | August 19, 1847 |

The Saint-Charles shaft (or No. 8 shaft) is one of the main collieries of the Ronchamp coal mine. It is located in Ronchamp, Haute-Saône, in eastern France. In the second half of the nineteenth century, this shaft made it possible to mine large coal seams, contributing to the company's golden age.

Saint-Charles has been open for over fifty years, a long life compared to other open shafts in the Ronchamp mining basin. It has also experienced mining disasters such as fires and firedamp blasts. The shaft is distinguished by its revolutionary extraction system using a cleat machine. The process, too complex, was eventually abandoned following technical setbacks.

After closure, the pit buildings were converted into housing; the slag heaps were re-used between the wars, as they were still rich in coal. At the end of the twentieth century, these same slag heaps, which had become a dumping ground for a nearby factory, burst into flames, frightening the local population.

Situation before sinking[edit]

After the Saint-Louis shaft was sunk in the hamlet of La Houillère in 1810, the company dug a series of shafts close to the outcrops, varying in depth from 19 to 165 meters. But the last shafts dug around 1830, found no coal. Shaft no. 5, continued by drilling, found no trace of coal, and shaft no. 6 stumbled on an uplift in the coalfield linked to a fault. In 1839, shaft no. 7 was sunk in search of coal. However, with the company bankrupt, the concession was put up for sale and the sinking stopped.

In 1843, Charles Demandre and Joseph Bezanson bought the Ronchamp concession and continued sinking shaft no. 7. They finally found coal at 205 meters, behind the uplift.[1] Shortly after the No. 7 shaft was commissioned, borehole X was drilled on the Champagney plain, uncovering significant coal seams. On August 28, 1845, a prefectoral decree authorized the digging of shaft no. 8.[2]

Sinking[edit]

Sinking of the shaft began on September 11, 1845, with a rectangular cross-section measuring 4.64 meters × 2.14 meters; the extraction chamber measures 1.70 meters × 1.76 meters.[2] By the end of 1846, it had reached a depth of 180 meters. A 60-hp steam engine was installed. On August 19, 1847, at a depth of 225.80 meters, the first layer was encountered, with a thickness of 2.50 meters of pure coal.[3]

To exploit the first layer immediately, the company uses the “sous stot” digging technique: a second shaft is dug parallel to the main shaft from the first layer. Once the intermediate layer has been reached, a gallery is dug under the main shaft and continues to the second layer. When both sections are completed, a junction is made. Digging lasted from September 1847 to April 1848.[4]

Operation[edit]

In 1848, a steam engine consisting of a single vertical cylinder with a diameter of 49 centimeters and a stroke of 1.356 meters was installed. This was a Meyer machine manufactured in the Expansion workshops, with a flywheel six meters in diameter. The extraction machine's pendulum is supported by two cast-iron columns, and vertical guides frame the piston. The manual braking system was replaced by a steam brake. The machine is rated at 60 hp6. The extraction compartment has only two guides, and the cages slide on either side of them. The cages can only hold one 315-kg carriage. Rolling is carried out by wheelbarrow in the galleries and with carts on cast-iron or wooden rails. In the same year,[notes 1] a large 700-metre-long inclined plane was built to follow the coal bed.[5]

In 1850, 57,413 tonnes of coal were extracted from the bowels of the Saint-Charles shaft. The latter exploited some of the most important veins in the Ronchamp coalfields, including a four-metre-thick layer in 1862 and a three-metre-thick layer discovered four years later.[6] In June 1861, the Saint-Charles pit continued to operate without interruption, extracting 2,585 tonnes of coal. However, this was no longer the most productive pit, as the Saint-Joseph pit extracted 6,258 tonnes and the Sainte-Barbe pit 2,622 tonnes in the same month.[7] Production amounted to 24,292.[7] tons in 1861, 30,205.7 tons in 1862 and 67,036 tons in 1863.[8]

In 1868, the most important part of the second layer was mined and production reached 100 tonnes per day. At the same time, the link with the Sainte-Marie shaft was completed, facilitating ventilation.[9] By 1873, all mining at the Saint-Charles shaft was taking place in the second layer on floors 260 and 315, and consideration was being given to mining the intermediate layer (located between the first and second layers).[9] Three years later, in January, 2,610 tonnes of coal, 550 cubic metres of water and 673 tonnes of spoil were brought up from the shaft.[9] In 1877, a telephone was installed to communicate with the bottom of the shaft.[10]

The cleat machine[edit]

By 1849, operations at the Saint-Charles shaft gradually expanded to the south, east, and west. The company considered sinking another well (the Saint-Joseph well, which would be sunk the following year), but sinking a well can take five to six years, and the company needed immediate resources. It therefore decided to sink an inclined plane at the same time as the Saint-Joseph shaft, to reach the area to be mined more quickly. The breakthrough of this descending gallery began in December 1849. It was initially equipped with a horse-drawn carousel, but this system was not sufficiently efficient, so the engineers thought of a new mining system: the cleat machine.[11]

A cleat machine has already been installed at the bottom of Compagnie des Mines d'Anzin's Davy pit in La Sentinelle, in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais coalfield, and the collieries have decided to use the same system at Ronchamp. Initially, a single circuit is to start from the Saint-Joseph shaft, then follow the inclined plane before climbing back up through the Saint-Charles shaft.[12]

In 1850, more than 200 meters below the surface, a steam engine and two boilers were installed in a large room close to the coal beds. The room, 50 meters from the shaft, is 17 meters long, 8 meters wide, and 4 meters high, and is supported by a massive oak framework, some parts of which are 40 cm square. This steam engine powers the cleat machine installed in the 700-meter-long inclined plane. The underground machines and boilers were supplied by Sthelier of Thann, as were the engine and all the cleat equipment for the vertical shaft. These elements were installed and ready for use on May 20, 1852. Until 1853, major mechanical operating problems were encountered, but these were resolved as testing progressed. Engineer Schutz was one of the instigators of this initiative, the machinery having been invented by Mr. Mehus 1. Conversely, engineer Francois Mathet, who joined the company in 1855, was highly critical of the system and its adoption, finding it dangerous for miners' lives due to the drought that could disrupt ventilation and even cause firedamp. He also described the fragility of the woodwork and the high temperatures the drivers had to endure.[13] On October 19, the underground boilers were lit, but immediately the fire, fanned by the 250-meter-high chimney, sucked all the air out of the mine. As a result, ventilation was difficult, and the workings were invaded by firedamp. On March 12, 1853, the inclined plane's cleat machine was put into operation. The water accumulated at the bottom of the large chute is evacuated by hand pumps installed at the top and bottom of the inclined plane over 200 meters. These pumps were operated by women. But on April 1, despite all the precautions taken, a fire broke out in the woods near the boilers.[6]

In 1855 and again in 1856, the Saint-Charles shaft produced 54,081 tonnes of coal thanks to the cleat machine. That same year, however, the decision was made to abandon this machine. At the same time, the women were dismissed from mine 1. The following year, the machine was dismantled and replaced by a wheel mining machine. This set in motion two cables, one ascending, the other descending, and vice-versa. Each cable was guided by two parallel wooden sills.[14]

In May 1852, a second machine of the same type, but vertical, was put into service over the entire height of the shaft, replacing the Meyer coil machine. It too suffered numerous breakdowns, requiring frequent shutdowns to readjust various parts over several months and in the years that followed. Finally, on March 29, 1857, the Board of Directors decided to return to the cable extraction system, and the vertical cleat machine was dismantled in 48 days, starting the following May 17. A 9-meter-high wooden headframe was built over the shaft, and the Meyer machine was refurbished.[15]

Accidents and disasters[edit]

Three firedamp blasts occurred in 1857: eight miners perished on January 29, two on March 3, and two on March 14.[6] On March 16, the entire workforce went on strike of these disasters. The shaft was deemed too dangerous, with poor ventilation and faulty equipment. The management lodged a complaint for coalition offenses, but the Haute-Saône prefecture ruled in favor of the miners, and the engineer was sentenced to prison for flagrant breaches of safety.[16]

On November 8, 1857, a fire broke out in the underground boiler room. The openings of shafts no. 7 and Saint-Charles are hermetically sealed. On January 18 the following year, a dog and a lighted lamp descended to the bottom of the shaft to test for the presence of a firedamp. On January 30, the openings in both shafts were reopened. However, energetic ventilation rekindled the fire in the coal. In 1859, water flooded the mine after more than six months of inactivity.[6]

In 1886, the shaft was bricked up from top to bottom, with a diameter of 3.30 meters. At the bottom, for the first time in Ronchamp, metal frames were installed over a kilometer of the gallery. Unfortunately, in June of the same year, another firedamp explosion killed twenty-three people.[6]

The ending[edit]

After the 1886 disaster, a large part of the galleries and the construction site were destroyed, in addition, forty years of intensive mining had greatly depleted the deposit, leaving the shaft virtually abandoned. But three years later, strong demand for coal prompted the company to rehabilitate the entire site and resume mining.[17]

In 1891, the pit was fitted out to accommodate around a hundred workers, but two years later, work was again halted, and only water was brought up from the shaft.[18] The following year, mining was resumed to remove the remains of coal panels,[notes 2] estimated to weigh 10,000 tonnes. They were excavated at a rate of 100 tonnes per day by around one hundred workers.[18] In October 1895, the workers completed the stripping[notes 3] and proceeded with the clearing.[notes 4] This work was completed in December of the same year. The shaft was then backfilled.[18]

Conversion[edit]

The shaft was backfilled from January to June 1896 at around ten carloads of shale per day. In May, an eight-meter-thick plug of clay and concrete was installed to make the shaft watertight.[19] The surface installations were demolished, except the machine building, which was converted into housing, and another building which housed accommodation and the “La Ruche” store.[20] The adjacent store was demolished in 2005 after being destroyed by fire.[21]

At the beginning of the 21st century, several of the pit's buildings still stand, including the well-preserved mining machine building, repainted white, and the large building housing the mine masters and the canteen. All these buildings have now been converted into housing.[22]

-

The floor of the Saint-Charles well in 2015.

-

Area where the well is located.

Mining town and shops[edit]

47°42′09″N 6°39′11″E / 47.702515°N 6.653095°E

In 1866, a food and clothing store was built on the site of the Saint-Charles well, next to the offices. It was later expanded to include a bakery and butcher's shop, and named “La Ruche”. The store was run by the company, and miners' purchases were deducted directly from their wages via their order and payroll books. After the Second World War, the store became a cooperative limited company with shares on the stock exchange.[20]

To accommodate the large workforce employed at the Saint-Charles shaft, a mining housing estate was built in 1872, a few dozen meters from the pithead. It consisted of four houses built of roughcast sandstone rubble, each with a single storey and long-sloped mechanical tile roofs.[23][24][25] Although the collieries had originally intended to build 24 dwellings, they had to give up for financial reasons. Each house is divided into four units, with two bedrooms, a kitchen, a cellar, an attic, and a garden for each family.[23] On March 11, 2010, the houses were listed in the general inventory of cultural heritage.[24]

The slag heap[edit]

The “terril du puits Saint-Charles” is a fairly extensive flat slag heap where waste rock has been piling up for half a century. Between 1926 and 1931, the slag heap's shales were sorted at the coal washing center to extract the remaining coal that was used as fuel for the boilers installed on the Chanois plain.[26]

In June 1993, the 15-metre-high slag heap containing 35,000 m3 of shale caught fire. A neighboring plant (MagLum) had previously buried waste such as zinc, cyanide, nickel, sulfur, polyurethane foam, hydrogen sulfide, phenols and hydrocarbon derivatives there. Thick black smoke billowed over the communes of Ronchamp and Champagney, causing concern and mobilizing the population. Gas analyses and health monitoring of children were carried out (27 of them complained of various symptoms: vomiting, nausea, headaches, throat and eye irritations). Analyses revealed heavy metal content (including aluminum) 750 times higher than the norm, as well as traces of trichloroethylene and nitrate vapors. Despite the intervention of the fire department and the installation of firebreak trenches and barriers, the fire persisted for months.[27][26][28] Part of the slag heap had to be moved in 1994 to extinguish it. The slag heap was then used as backfill for a road.[29] The Saint-Charles pit still has a large slag heap, even though a large part of it was removed during the fire.[24]

-

General aerial view of the slag heap, shaft buildings and large offices.

-

View of the slag heap.

-

The summit.

Workshops and offices[edit]

47°42′09″N 6°39′11″E / 47.702515°N 6.653095°E

Shortly after the opening of the shaft and its good results, the company decided to set up its central workshops and offices next to the shaft and established a link with the rail network. These facilities remained the nerve center of the collieries until their closure in 1958.[30] The site was converted into a car manufacturing subcontracting plant before being decommissioned in 2008. At the beginning of the 21st century, the site was used for exhibitions and shooting games.

The station[edit]

47°42′12″N 6°39′12″E / 47.703343°N 6.653262°E

Once the coal carts have been hauled up from the Saint-Charles shaft, they are emptied into large wagons. The wagons are transferred to a station close to the shaft via a railroad built in 1858, before the coal is shipped to the coal mine's customers, most of whom are from Alsace, via the Paris-Est to Mulhouse-Ville railroad.[31]

The station was in operation from the mid-19th century until 1958, when the mines closed, after which it was dismantled. At the beginning of the 21st century, the station site was overgrown, and only a few remnants of the installations and network remained.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Parietti (2001, p. 17)

- ^ a b Mathet (1882, pp. 137 144)

- ^ Parietti (1999, p. 3)

- ^ Parietti (1999, p. 4)

- ^ Parietti (1999, p. 5)

- ^ a b c d e "Les puits creusés dans le bassin houiller de ronchamp". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-07.

- ^ a b Parietti (1999, p. 34)

- ^ Godard (2012, p. 336)

- ^ a b c Parietti (1999, p. 35)

- ^ Parietti (1999, p. 36)

- ^ Parietti (1999, p. 8)

- ^ Parietti (1999, pp. 8–9)

- ^ Mathet (1882, pp. 139–140)

- ^ Parietti (1999, p. 7)

- ^ Mathet (1882, pp. 141–173)

- ^ Parietti (2010, p. 91)

- ^ Parietti (1999, p. 39)

- ^ a b c Parietti (1999, p. 40)

- ^ Parietti (1999, pp. 40–55)

- ^ a b PNRBV (1999, p. 24)

- ^ "Ancien magasin La Ruche". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ "Le puits Saint Charles". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ a b PNRBV (1999, p. 25)

- ^ a b c "Le terril de Saint Charles". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-07.

- ^ "La cité Saint Charles". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ a b Parietti (1999, p. 41)

- ^ "Le feu dans le terril de Saint Charles". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ "La psychose d'un ancien village minier face au terril en feu depuis neuf mois - L'Humanité". humanité (in French). 1994-02-07. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ "Enlèvement des schistes brûlants". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ "Les ateliers de réparation des mines". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ "Le réseau ferré entre les puits". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

Notes[edit]

- ^ Jacking” involves digging a mine shaft from the surface. By extension, any excavation of a steeply inclined structure can be described as jacking. This includes not only the excavation, but also the removal of spoil and the initial lining.

- ^ The panels are large-area pillars or unused mine areas.

- ^ When a mine or shaft is mined, galleries are dug in a checkerboard pattern to extract the coal, forming regular, square natural pillars. When all the galleries have been dug, these pillars, which contain a lot of coal, are removed. This is known as “de-piling”.

- ^ When digging the galleries, natural pillars are not enough, so wooden beams are installed. At the end of the operation, they are reclaimed. This is known as “deforestation”.

Bibliography[edit]

- Parietti, Jean-Jacques (2001). Les Houillères de Ronchamp. Éditions Comtoises. ISBN 2-914425-08-2.

- Parietti, Jean-Jacques (2010). Les Houillères de Ronchamp, vol. 2: Les mineurs. Franche-Comté culture & patrimoine. ISBN 978-2-36230-001-1.

- Parietti, Jean-Jacques (1999). Le puits Saint-Charles, coll. Les dossiers de la Houillère. Ronchamp, Association des amis du musée de la mine.

- Mathet, François (1882). Mémoire sur les mines de Ronchamp. Société de l'industrie minérale. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- PNRBV (1999). Le charbon de Ronchamp : circuits miniers de Ronchamp, coll. « Déchiffrer le patrimoine ». Parc naturel régional des Ballons des Vosges. ISBN 2-910328-31-7.

- Société de l'industrie minérale, Bulletin trimestriel. Saint-Étienne. 1882.

- Thirria, Édouard (1869). Manuel à l'usage de l'habitant du département de la Haute-Saône.

- Godard, Michel (2012). Enjeux et impacts de l'exploitation minière du bassin houiller de Ronchamp.