Beatrizsborges (talk | contribs) Tag: Visual edit |

Beatrizsborges (talk | contribs) Tag: Visual edit |

||

| (33 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description| |

{{Short description|French coal mine shaft}} |

||

{{Infobox mine|name=Saint-Charles shaft|image=1880 - Puits Saint-Charles.jpg|caption=surface installations|location=Bourgogne-Franche-Comté|country=[[France]]|type=shaft|opening year=September 14, 1845|active years=August 19, 1847}} |

|||

{{Infobox settlement |

|||

The '''Saint-Charles shaft''' (or No. 8 shaft) is one of the main collieries of the [[Ronchamp coal mines|Ronchamp coal mine]]. It is located in [[Ronchamp]], [[Haute-Saône]], in eastern France. In the second half of the nineteenth century, this shaft made it possible to mine large coal seams, contributing to the company's golden age. |

|||

| official_name = Dornach |

|||

| image_skyline = Dornach, Temple calviniste.jpg |

|||

| image_caption = Dornach Reformed Temple. |

|||

| image_map = Mulhouse Dornach.jpg |

|||

| image_map1 = France location map-Regions and departements-2016.svg |

|||

| map_caption = Location of the district in Mulhouse. |

|||

| coordinates = {{coord|47|44|50|N|7|18|33|W}} |

|||

| population_total = 5684 hab. (2006) |

|||

| settlement_type = Administration |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Dornach''' is one of the main affluent residential districts<ref>{{Cite web |title=AFUT - Votre ingénierie mutualisée et d'intérêt général |url=https://afut-sudalsace.org/ |access-date=2024-05-06 |website=afut-sudalsace.org}}</ref><ref name=":0">{{Cite web |title=AFUT - Votre ingénierie mutualisée et d'intérêt général |url=https://afut-sudalsace.org/ |access-date=2024-05-06 |website=afut-sudalsace.org}}</ref> of [[Mulhouse]] intra muros, bordering [[Morschwiller-le-Bas]] and [[Lutterbach]]. It is an ancient settlement that owes its name to the [[Celts]], a name that the Romans later Latinized into Durnacum and later Germanized into Dornach. Dornach was once an autonomous commune, and for a long time served as a border village between the independent [[Republic of Mulhouse]] and Upper [[Alsace]] (of which it was a part), which was alternately under French and German rule. As such, it was home to the local Jewish and Catholic bourgeoisie, who were unable to stay in the territory of the Republic of Mulhouse due to the adoption of the exclusive [[Reformed Christianity|Calvinist]] religion. |

|||

Saint-Charles has been open for over fifty years, a long life compared to other open shafts in the Ronchamp mining basin. It has also experienced mining disasters such as fires and firedamp blasts. The shaft is distinguished by its revolutionary extraction system using a cleat machine. The process, too complex, was eventually abandoned following technical setbacks. |

|||

In 1908, under the [[German Empire]], the town, whose population had grown strongly in the 19th century thanks to industrial development, asked to be merged with Mulhouse, as it was unable to solve the problems associated with urban development on its own. The merger took effect in 1914, the year in which the district was the scene of the Battle of Dornach. The former Dornach industrial district of Brustlein became a fully-fledged Mulhouse district, while the Daguerre district, previously located in both communes, was unified, and the City of Mulhouse used the undeveloped parts of the commune to build the Haut-Poirier district (Illberg and Bel Air) and the Coteaux district. The former village area to the west of the [[Strasbourg]] → Basel railroad line, located between the Dornach fairgrounds and the commune of Lutterbach, became the Mulhouse district of Dornach, which took on its current boundaries. |

|||

After closure, the pit buildings were converted into housing; the slag heaps were re-used between the wars, as they were still rich in coal. At the end of the twentieth century, these same slag heaps, which had become a dumping ground for a nearby factory, burst into flames, frightening the local population. |

|||

At the start of the 21st century, Dornach still retains its village-style urban layout, making it an attractive residential area. The proximity of a large peripheral shopping area, two university campuses and two business parks, combined with motorway and rail links (Zu-Rhein, Mulhouse-Dornach and Musées stations) and the presence of the tramway (Line 3, Mulhouse Vallée de la Thur tram-train) further enhance this appeal. The late 20th and early 21st centuries were marked by the development of the ever-expanding Mulhouse Technology Crescent to the north, south and west of the district. |

|||

== Situation before sinking == |

|||

== Geography == |

|||

After the Saint-Louis shaft was sunk in the hamlet of La Houillère in 1810, the company dug a series of shafts close to the outcrops, varying in depth from 19 to 165 meters. But the last shafts dug around 1830, found no coal. Shaft no. 5, continued by drilling, found no trace of coal, and shaft no. 6 stumbled on an uplift in the coalfield linked to a fault. In 1839, shaft no. 7 was sunk in search of coal. However, with the company bankrupt, the concession was put up for sale and the sinking stopped. |

|||

The Dornach district lies to the west of Mulhouse. A tributary of the Doller river, the Steinbaechlein, runs through the district, having been canalized in the 19th century when the area was industrialized. |

|||

In 1843, Charles Demandre and Joseph Bezanson bought the Ronchamp concession and continued sinking shaft no. 7. They finally found coal at 205 meters, behind the uplift.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|2001|p=17}}</ref> Shortly after the No. 7 shaft was commissioned, borehole X was drilled on the Champagney plain, uncovering significant coal seams. On August 28, 1845, a prefectoral decree authorized the digging of shaft no. 8.<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

=== Transport === |

|||

The district is served by the Mulhouse-Dornach train station and by public transport in the Mulhouse area. |

|||

== Sinking == |

|||

=== Neighboring towns and districts === |

|||

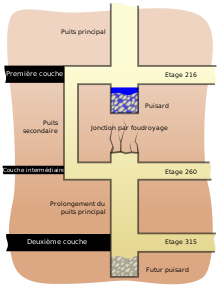

[[File:Fonçage puits Saint-Charles sous stot.svg|left|thumb|The “under stot” sinking method.]] |

|||

{{Adjacent communities|NORTHWEST=[[Lutterbach]]|title=Communes and districts bordering the Dornach district|North=Brustlein (Mulhouse)|South=Daguerre (Mulhouse)|EAST=[[Les Coteaux (Mulhouse)]]|WEST=Morschwiller-le-Bas|SOUTHEAST=Haut-Poirier|state=|Centre=Dornach}} |

|||

Sinking of the shaft began on September 11, 1845, with a rectangular cross-section measuring 4.64 meters × 2.14 meters; the extraction chamber measures 1.70 meters × 1.76 meters.<ref name=":1">{{Harvtxt|François Mathet|1882|pp=137 144}}</ref> By the end of 1846, it had reached a depth of 180 meters. A 60-hp steam engine was installed. On August 19, 1847, at a depth of 225.80 meters, the first layer was encountered, with a thickness of 2.50 meters of pure coal.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=3}}</ref> |

|||

To exploit the first layer immediately, the company uses the “sous stot” digging technique: a second shaft is dug parallel to the main shaft from the first layer. Once the intermediate layer has been reached, a gallery is dug under the main shaft and continues to the second layer. When both sections are completed, a junction is made. Digging lasted from September 1847 to April 1848.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=4}}</ref> |

|||

=== Toponymy === |

|||

Alsatian: Durni. Derived from Turnach (1250) from the [[Gallo-Romance languages|Gallo-Roman]] etymon Turnacum, meaning “where there is a rise in the ground”. This word has the same etymology as Tournay and Tournai (Doornik) in Belgium.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Paul Urban |first=Michel |title=Lieux dits dictionnaire étymologique et historique des noms de lieux d'Alsace |date=2003 |publisher=Editions du Rhin}}</ref> |

|||

== |

== Operation == |

||

[[File:Plan Puits Saint-Charles 1.jpg|thumb|280x280px|Plan of Saint-Charles well facilities.]] |

|||

In 1848, a steam engine consisting of a single vertical cylinder with a diameter of 49 centimeters and a stroke of 1.356 meters was installed. This was a Meyer machine manufactured in the Expansion workshops, with a flywheel six meters in diameter. The extraction machine's pendulum is supported by two cast-iron columns, and vertical guides frame the piston. The manual braking system was replaced by a steam brake. The machine is rated at 60 hp6. The extraction compartment has only two guides, and the cages slide on either side of them. The cages can only hold one 315-kg carriage. Rolling is carried out by wheelbarrow in the galleries and with carts on cast-iron or wooden rails. In the same year,<ref group="notes">Jacking” involves digging a mine shaft from the surface. By extension, any excavation of a steeply inclined structure can be described as jacking. This includes not only the excavation, but also the removal of spoil and the initial lining.</ref> a large 700-metre-long inclined plane was built to follow the coal bed.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=5}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Plan Puits Saint-Charles 2.jpg|left|thumb|300x300px|Floor plan of the Saint-Charles: canteen and porter's quarters; weighbridge; administration; old boilers and machine; large chimney; coils; new machine; and c. boilers added during expansions; lamp house; well; smoke channel; thick dividing wall. ]] |

|||

In 1850, 57,413 tonnes of coal were extracted from the bowels of the Saint-Charles shaft. The latter exploited some of the most important veins in the Ronchamp coalfields, including a four-metre-thick layer in 1862 and a three-metre-thick layer discovered four years later.<ref name=":2">{{Cite web |title=Les puits creusés dans le bassin houiller de ronchamp |url=http://www.abamm.org/lespuits.html |access-date=2024-05-07 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref> In June 1861, the Saint-Charles pit continued to operate without interruption, extracting 2,585 tonnes of coal. However, this was no longer the most productive pit, as the Saint-Joseph pit extracted 6,258 tonnes and the Sainte-Barbe pit 2,622 tonnes in the same month.<ref name=":3">{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=34}}</ref> Production amounted to 24,292.<ref name=":3" /> tons in 1861, 30,205.7 tons in 1862 and 67,036 tons in 1863.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Michel Godard|2012|p=336}}</ref> |

|||

In 1868, the most important part of the second layer was mined and production reached 100 tonnes per day. At the same time, the link with the Sainte-Marie shaft was completed, facilitating ventilation.<ref name=":0">{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=35}}</ref> By 1873, all mining at the Saint-Charles shaft was taking place in the second layer on floors 260 and 315, and consideration was being given to mining the intermediate layer (located between the first and second layers).<ref name=":0" /> Three years later, in January, 2,610 tonnes of coal, 550 cubic metres of water and 673 tonnes of spoil were brought up from the shaft.<ref name=":0" /> In 1877, a telephone was installed to communicate with the bottom of the shaft.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=36}}</ref> |

|||

=== Prehistory === |

|||

Evidence of Dornach's occupation dates back to the [[Neolithic|Neolithic period]], with carved flints and axes discovered at the foot of the Illberg. Remains from the Hallstatt and La Tène periods include tombs, Vilannovian fibulae, Gallic coins and other objects. The Romans Latinized the name Durnachos to Durnacum or Turnacum. During major invasions, the area was occupied by the Alamanni and Franks, who Germanized the name to Turnich, Durnich, Durnach and finally Dornach.<ref>{{Cite web |title=L'histoire de Dornach... en diagonale |url=http://www.dornach.fr/website/memoire/histoire/49-histoire-de-dornach-en-diagonale.html |access-date=2024-05-06 |website=www.dornach.fr}}</ref> |

|||

== The cleat machine == |

|||

[[File:Machine à tacquet 02.jpg|thumb|Plans of the bottom of the shaft. 1: ground plan of the galleries, 2: plan of the brick dams, 3: cross-section of the shaft.]] |

|||

In the [[Middle Ages]], the village of Dornach belonged to the abbey of [[Murbach]], which gave it in fief to a noble family taking the name of Dornach.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The City of Dornach – The Swiss Spectator |url=https://www.swiss-spectator.ch/schwarzbubenland/ |access-date=2024-05-06 |website=www.swiss-spectator.ch}}</ref> |

|||

By 1849, operations at the Saint-Charles shaft gradually expanded to the south, east, and west. The company considered sinking another well (the Saint-Joseph well, which would be sunk the following year), but sinking a well can take five to six years, and the company needed immediate resources. It therefore decided to sink an inclined plane at the same time as the Saint-Joseph shaft, to reach the area to be mined more quickly. The breakthrough of this descending gallery began in December 1849. It was initially equipped with a horse-drawn carousel, but this system was not sufficiently efficient, so the engineers thought of a new mining system: the cleat machine.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=8}}</ref> |

|||

A cleat machine has already been installed at the bottom of Compagnie des Mines d'Anzin's Davy pit in La Sentinelle, in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais coalfield, and the collieries have decided to use the same system at Ronchamp. Initially, a single circuit is to start from the Saint-Joseph shaft, then follow the inclined plane before climbing back up through the Saint-Charles shaft.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|pp=8-9}}</ref> |

|||

=== Renaissance === |

|||

[[File:Machine à tacquet 01.png|thumb|292x292px|The cleat machine.]] |

|||

At the beginning of the 15th century, the de Dornach family died out. The sole heiress, Vérène, married Hertrich II Zu Rhein. The fiefdom of Dornach remained in the hands of the Zu Rheins until the French Revolution. The Thirty Years' War decimated the village, which fell from 200 inhabitants at the start of the conflict to 18 or 20 by the end of the war. When peace was signed, Dornach was repopulated.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Steiner |url=https://www.amazon.co.uk/Chutes-renaissance-spirituelles-conf%C3%A9rences-Dornach/dp/2881891519 |title=Chute Et Renaissance: Douze conférences faites à Dornach du 5 au 28 janvier 1923 |date=2006-12-14 |publisher=ROMANDES |isbn=978-2-88189-151-9 |language=French}}</ref> |

|||

In 1850, more than 200 meters below the surface, a steam engine and two boilers were installed in a large room close to the coal beds. The room, 50 meters from the shaft, is 17 meters long, 8 meters wide, and 4 meters high, and is supported by a massive oak framework, some parts of which are 40 cm square. This steam engine powers the cleat machine installed in the 700-meter-long inclined plane. The underground machines and boilers were supplied by Sthelier of Thann, as were the engine and all the cleat equipment for the vertical shaft. These elements were installed and ready for use on May 20, 1852. Until 1853, major mechanical operating problems were encountered, but these were resolved as testing progressed. Engineer Schutz was one of the instigators of this initiative, the machinery having been invented by Mr. Mehus 1. Conversely, engineer Mathet, who joined the company in 1855, was highly critical of the system and its adoption, finding it dangerous for miners' lives due to the drought that could disrupt ventilation and even cause firedamp. He also described the fragility of the woodwork and the high temperatures the drivers had to endure.<ref>{{Harvtxt|François Mathet|1882|pp=139-140}}</ref> On October 19, the underground boilers were lit, but immediately the fire, fanned by the 250-meter-high chimney, sucked all the air out of the mine. As a result, ventilation was difficult, and the workings were invaded by firedamp. On March 12, 1853, the inclined plane's cleat machine was put into operation. The water accumulated at the bottom of the large chute is evacuated by hand pumps installed at the top and bottom of the inclined plane over 200 meters. These pumps were operated by women. But on April 1, despite all the precautions taken, a fire broke out in the woods near the boilers.<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

In 1855 and again in 1856, the Saint-Charles shaft produced 54,081 tonnes of coal thanks to the cleat machine. That same year, however, the decision was made to abandon this machine. At the same time, the women were dismissed from mine 1. The following year, the machine was dismantled and replaced by a wheel mining machine. This set in motion two cables, one ascending, the other descending, and vice-versa. Each cable was guided by two parallel wooden sills.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=7}}</ref> |

|||

=== In the 19th century === |

|||

[[File:Etablissement Dollfus-Mieg à Dornach.jpg|thumb|The Dollfus-Mieg factory in the 19th century.]] |

|||

Mulhouse's first industrialization soon had an impact on the village. It was in Dornach that the first steam engine was installed in 1812.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Historique de l |url=https://archive.wikiwix.com/cache/index2.php?url=http://www.alsace-lorraine.org/historiquea.htm#federation=archive.wikiwix.com&tab=url |access-date=2024-05-06 |website=archive.wikiwix.com}}</ref> Along the Steinbaechlein, textile factories set up shop: Blech-Fries, DollfusMieg et Cie, Hofer and Schlumberger, Thierry-Mieg au Brustlein. Louis René Villermé visits Dornach to write Tableau de l'état physique et moral des ouvriers employés dans les manufactures de coton, de laine et de soie, published in 1840. In it, he describes the working conditions of workers in the commune's factories.<blockquote>“In Mulhouse, in Dornach, work started at five in the morning and finished at five in the evening, summer and winter alike. [...] You have to see them arriving in town every morning and leaving every evening. Among them are a multitude of pale, skinny women, walking barefoot in the middle of the mud and who, for want of umbrellas, wear their aprons or petticoats over their heads when it rains or snows, to protect their faces and necks, and a larger number of young children, no less dirty, no less pale, covered in rags, all greasy with the oil from the looms that falls on them while they work. The latter, better protected from the rain by the impermeability of their clothes, don't even carry on their arms, like the women just mentioned, a basket containing the day's provisions; but they do carry in their hands, or hide under their jackets as best they can, the morsel of bread that must feed them until the time they return home.”<ref>{{Cite web |title=MIA: Paul Lagargue: 'Le droit à la paresse' (1880) |url=https://www.marxists.org/francais/lafargue/works/1880/00/lafargue_18800000.htm |access-date=2024-05-06 |website=www.marxists.org}}</ref></blockquote>He also describes the workers' lodgings: “I saw in Mulhouse, Dornach and neighboring houses, miserable dwellings where two families each slept in a corner, on straw thrown on the floor and held together by two boards.... The misery in which the workers in the cotton industry in the Haut-Rhin department live is so profound that it produces the sad result that, while in the families of manufacturers, merchants, drapers and factory managers, half of the children reach the age of twenty-one, this same half ceases to exist before the age of two in the families of weavers and cotton mill workers."<ref>{{Cite web |last=Marseillaise |first=La |title=[#MémoriaDauPaïs] Le logement des ouvriers |url=https://www.lamarseillaise.fr/culture/le-logement-des-ouvriers-GFLM042712 |access-date=2024-05-06 |website=www.lamarseillaise.fr |language=fr-FR}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Riedweg |first=Eugène |url=https://books.google.com.br/books?id=licBEQAAQBAJ&pg=PA61&lpg=PA61&dq=J%E2%80%99ai+vu+%C3%A0+Mulhouse,+%C3%A0+Dornach+et+dans+des+maisons+voisines,+de+ces+mis%C3%A9rables+logements+o%C3%B9+deux+familles+couchaient+chacune+dans+un+coin,+sur+la+paille+jet%C3%A9e+sur+le+carreau+et+retenue+par+deux+planches%E2%80%A6+Cette+mis%C3%A8re+dans+laquelle+vivent+les+ouvriers+de+l%E2%80%99industrie+du+coton+dans+le+d%C3%A9partement+du+Haut-Rhin+est+si+profonde+qu%E2%80%99elle+produit+ce+triste+r%C3%A9sultat+que,+tandis+que+dans+les+familles+des+fabricants+n%C3%A9gociants,+drapiers,+directeurs+d%E2%80%99usines,+la+moiti%C3%A9+des+enfants+atteint+la+vingt+et+uni%C3%A8me+ann%C3%A9e,+cette+m%C3%AAme+moiti%C3%A9+cesse+d%E2%80%99exister+avant+deux+ans+accomplis+dans+les+familles+de+tisserands+et+d%E2%80%99ouvriers+de+filatures+de+coton.&source=bl&ots=feAGjK6IJP&sig=ACfU3U3cZFRl_kuSVO86PqQnWB4esN3Gmw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwifypKn0PmFAxXgPrkGHWNTBJEQ6AF6BAgIEAM |title=Mulhouse: Images d'une ville singulière |date=1997-01-01 |publisher=FeniXX |isbn=978-2-307-47289-6 |language=fr}}</ref> |

|||

In May 1852, a second machine of the same type, but vertical, was put into service over the entire height of the shaft, replacing the Meyer coil machine. It too suffered numerous breakdowns, requiring frequent shutdowns to readjust various parts over several months and in the years that followed. Finally, on March 29, 1857, the Board of Directors decided to return to the cable extraction system, and the vertical cleat machine was dismantled in 48 days, starting the following May 17. A 9-meter-high wooden headframe was built over the shaft, and the Meyer machine was refurbished.<ref>{{Harvtxt|François Mathet|1882|pp=141-173}}</ref> |

|||

Adolphe Braun's photographic company was founded in Dornach in 1853.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Universalis |first=Encyclopædia |title=Résultats pour « Michel » (Page 147) - Recherche |url=https://www.universalis.fr/recherche/Michel/article/147/ |access-date=2024-05-06 |website=Encyclopædia Universalis |language=fr-FR}}</ref> It became an industrial establishment in 1862. Its reputation soon spread around the world, thanks to reproductions of works of art housed in the major museums of Europe.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Château de Chantilly {{!}} Parc {{!}} Grandes Écuries |url=https://chateaudechantilly.fr/ |access-date=2024-05-06 |website=Château de Chantilly |language=fr-FR}}</ref> The population grew rapidly: 160 in 1764, 500 in 1789, 900 in 1813, 3,000 in 1851, 11,234 in 1913. |

|||

=== |

=== Accidents and disasters === |

||

[[File:Puits Saint-Charles XXe - 03.JPG|thumb|Miners in the shaft around 1880.]] |

|||

On August 19, 1914, Dornach, the new district of Mulhouse,<ref>{{Cite web |title=Dornach - Notice Communale |url=http://cassini.ehess.fr/fr/html/fiche.php?select_resultat=12088 |access-date=2024-05-06 |website=cassini.ehess.fr}}</ref> was at the heart of one of the first battles of the [[World War I]]. On August 8, according to [[Plan XVII]], French troops entered Mulhouse. But the city fell back into German hands two days later. Heavy fighting broke out in Illzach along the railway embankment. On August 18, French troops resume the offensive. The Germans and French were face to face in Dornach the following morning. The Battle of Dornach begins. The French artillery fired large numbers of shells into the houses of Dornach to support the advance of their infantry. By 5 p.m., French troops had taken possession of Mulhouse. Hundreds were killed and wounded on both sides. French troops abandoned Mulhouse on August 25, 1914. During the war, the Dornach chemical factories produced asphyxiating gas for German troops. They were bombed by French aircraft in November 19158. According to the newspaper Le Miroir, 42 workers, the plant manager and a German colonel were asphyxiated by the gases they were producing9. Served by streetcar, train and freeway and close to major industrial areas, Dornach nevertheless retained a “village-like” urban structure, making it an attractive residential area. From the end of the 20th century onwards, it became one of Mulhouse's two main middle-class neighborhoods,<ref name=":0" /> attracting mainly residents from wealthier socio-professional categories. |

|||

Three firedamp blasts occurred in 1857: eight miners perished on January 29, two on March 3, and two on March 14.<ref name=":2" /> On March 16, the entire workforce went on strike of these disasters. The shaft was deemed too dangerous, with poor ventilation and faulty equipment. The management lodged a complaint for coalition offenses, but the [[Haute-Saône]] prefecture ruled in favor of the miners, and the engineer was sentenced to prison for flagrant breaches of safety.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Jean-Jacques Parietti|2010|p=91}}</ref> |

|||

On November 8, 1857, a fire broke out in the underground boiler room. The openings of shafts no. 7 and Saint-Charles are hermetically sealed. On January 18 the following year, a dog and a lighted lamp descended to the bottom of the shaft to test for the presence of a firedamp. On January 30, the openings in both shafts were reopened. However, energetic ventilation rekindled the fire in the coal. In 1859, water flooded the mine after more than six months of inactivity.<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

== Religious communities == |

|||

In 1886, the shaft was bricked up from top to bottom, with a diameter of 3.30 meters. At the bottom, for the first time in Ronchamp, metal frames were installed over a kilometer of the gallery. Unfortunately, in June of the same year, another firedamp explosion killed twenty-three people.<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

=== The Jewish community === |

|||

Until 1798, Jews were forbidden to live in Mulhouse. They settled in the surrounding communes, such as Dornach. In 1798, the city's Jewish community drew up a Memorbuch. It contained prayers in memory of the victims of persecution in [[Germany]], [[Austria]], [[Bohemia]], [[Spain]], [[Poland]] and [[Holland]].<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":2">{{Cite book |last=Hyman |first=Paula |url=https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Emancipation_of_the_Jews_of_Alsace.html?id=7q99QgAACAAJ |title=The Emancipation of the Jews of Alsace: Acculturation and Tradition in the Nineteenth Century |last2=Hyman |first2=Professor of Judaic Studies Paula E. |date=1991 |publisher=Yale University Press |isbn=978-0-300-04986-2 |language=en}}</ref> In the 19th century, the community continued to grow. A new synagogue, now abandoned, was built in 1851 to plans by [[Jean-Baptiste Schacre]], architect for the city of Mulhouse. A special feature of the Dornach synagogue is the existence of a small pit, located between the Almémor<ref group="notes">Literally “dais”, platform for reading the Torah (Pentateuch), the Prophets and the Scroll of Esther</ref> and the Holy Ark<ref group="notes">Torah scroll cabinet</ref> and filled in 1959. In June 1940, faced with the advance of the German army, many Jews fled Mulhouse and the Dornach district. The Nazis expelled those who remained in September.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web |title=Dornach |url=http://www.judaisme-alsalor.fr/synagog/hautrhin/a-f/dornach.htm#:~:text=Dornach,%20attach%C3%A9e%20au%20royaume%20de,abrit%C3%A9%20une%20petite%20communaut%C3%A9%20juive. |access-date=2024-05-06 |website=www.judaisme-alsalor.fr}}</ref><ref name=":2" /> |

|||

[[File:Cèdre arbre remarquable Dornach temple.jpg|thumb|376x376px|One hundred year old cedar in the garden of the Dornach temple]] |

|||

=== The |

=== The ending === |

||

After the 1886 disaster, a large part of the galleries and the construction site were destroyed, in addition, forty years of intensive mining had greatly depleted the deposit, leaving the shaft virtually abandoned. But three years later, strong demand for coal prompted the company to rehabilitate the entire site and resume mining.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=39}}</ref> |

|||

The Dornach temple on rue Schoepflin is the place of worship for the Protestant Reformed community. The Protestant parish of Dornach includes Protestants from Dornach, Heimsbrunn, Lutterbach, Morschwiller-le-Bas and Reiningue. |

|||

In 1891, the pit was fitted out to accommodate around a hundred workers, but two years later, work was again halted, and only water was brought up from the shaft.<ref name=":4">{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=40}}</ref> The following year, mining was resumed to remove the remains of coal panels,<ref group="notes">The panels are large-area pillars or unused mine areas.</ref> estimated to weigh 10,000 tonnes. They were excavated at a rate of 100 tonnes per day by around one hundred workers.<ref name=":4" /> In October 1895, the workers completed the stripping<ref group="notes">When a mine or shaft is mined, galleries are dug in a checkerboard pattern to extract the coal, forming regular, square natural pillars. When all the galleries have been dug, these pillars, which contain a lot of coal, are removed. This is known as “de-piling”.</ref> and proceeded with the clearing.<ref group="notes">When digging the galleries, natural pillars are not enough, so wooden beams are installed. At the end of the operation, they are reclaimed. This is known as “deforestation”.</ref> This work was completed in December of the same year. The shaft was then backfilled.<ref name=":4" /> |

|||

=== The Catholic community === |

|||

The Coteaux de l'Illberg parish community supports several Catholic churches in the area, including Saint Barthélemy Church in Rue du Château Zu-Rhein. |

|||

== |

== Conversion == |

||

The shaft was backfilled from January to June 1896 at around ten carloads of shale per day. In May, an eight-meter-thick plug of clay and concrete was installed to make the shaft watertight.<ref>{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|pp=40-55}}</ref> The surface installations were demolished, except the machine building, which was converted into housing, and another building which housed accommodation and the “La Ruche” store.<ref name=":7">{{Harvtxt|PNRBV|p=24}}</ref> The adjacent store was demolished in 2005 after being destroyed by fire.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Ancien magasin La Ruche |url=http://www.abamm.org/divers02.html |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref> |

|||

{{Demography |

|||

| Title = Demographic trends of Dornach |

|||

| 1793 = 503 |

|||

| 1800 = 567 |

|||

| 1806 = 777 |

|||

| 1821 = 1139 |

|||

| 1831 = 1634 |

|||

| 1836 = 2706 |

|||

| 1841 = 2920 |

|||

| 1846 = 3150 |

|||

| 1851 = 2983 |

|||

| 1861 = 3867 |

|||

| 1866 = 3981 |

|||

| 1872 = 4114 |

|||

| 1876 = 4750 |

|||

| 1881 = 4511 |

|||

| 1886 = 5445 |

|||

| 1891 = 5655 |

|||

| 1896 = 6179 |

|||

| 1901 = 7312 |

|||

| 1906 = 8440 |

|||

| 1911 = 10447 |

|||

| source = Ldh/EHESS/Cassini |

|||

}} |

|||

At the beginning of the 21st century, several of the pit's buildings still stand, including the well-preserved mining machine building, repainted white, and the large building housing the mine masters and the canteen. All these buildings have now been converted into housing.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Le puits Saint Charles |url=http://www.abamm.org/stcharle.html |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref><gallery mode="packed" widths="280"> |

|||

== Major museums == |

|||

File:Puits Saint-Charles 2015.JPG|The floor of the Saint-Charles well in 2015. |

|||

The Cité du Train and the Musée Electropolis, two internationally renowned museums, are located in the north of the district. The former is Europe's largest railway museum,<ref>{{Cite web |date=2011-09-03 |title=Cité du Train - Musée du chemin de fer |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110903122907/http://www.citedutrain.com/fr/train/ |access-date=2024-05-06 |website=web.archive.org}}</ref> while the latter is Europe's largest museum of the history of electricity and household appliances. |

|||

File:Puits Saint-Charles 2013 (2).JPG|Area where the well is located. |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

== Mining town and shops == |

|||

In 1961, the city of Mulhouse donated land in Dornach to enable the SNCF to display rolling stock representative of its history. On October 14, 1969, the “Association du Musée Français du Chemin de Fer” was founded.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Ajecta – Musée vivant du chemin de fer |url=https://www.ajecta.fr/ |access-date=2024-05-06 |language=fr-FR}}</ref> |

|||

{{coord|47.702515|6.653095|scale:1000_region:FR|name=Ateliers centraux et bureaux}} |

|||

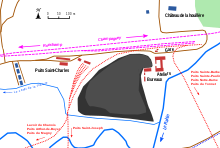

[[File:Plan Puits Saint-Charles - annexes - terrils - cités.svg|thumb|The environment of the Saint-Charles well and its ancillary facilities.{{Legend|black|slag heaps}}{{Legend|#800000|Mine buildings}}{{Legend|#004080|Mining town}}{{Legend|red|Coal mining network|outline=red dotted}}{{Legend|blue|Line from Vesoul to Plancher-les-Mines Chemins de fer vicinaux de la Haute-Saône}}{{Legend|pink|Ligne de Paris-Est à Mulhouse-Ville Compagnie des chemins de fer de l'Est then Société nationale des chemins de fer français}}]] |

|||

In 1866, a food and clothing store was built on the site of the Saint-Charles well, next to the offices. It was later expanded to include a bakery and butcher's shop, and named “La Ruche”. The store was run by the company, and miners' purchases were deducted directly from their wages via their order and payroll books. After the [[World War II|Second World War]], the store became a cooperative limited company with shares on the stock exchange.<ref name=":7" />[[File:Cité minière Saint-Charles.JPG|left|thumb|Saint-Charles housing estate.]]To accommodate the large workforce employed at the Saint-Charles shaft, a mining housing estate was built in 1872, a few dozen meters from the pithead. It consisted of four houses built of roughcast sandstone rubble, each with a single storey and long-sloped mechanical tile roofs.<ref name=":5">{{Harvtxt|PNRBV|p=25}}</ref><ref name=":6" /><ref>{{Cite web |title=La cité Saint Charles |url=http://www.abamm.org/citeou04.html |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref> Although the collieries had originally intended to build 24 dwellings, they had to give up for financial reasons. Each house is divided into four units, with two bedrooms, a kitchen, a cellar, an attic, and a garden for each family.<ref name=":5" /> On March 11, 2010, the houses were listed in the general inventory of cultural heritage.<ref name=":6" /> |

|||

== The slag heap == |

|||

In 1992, the Electropolis Museum was created, thanks in part to EDF's sponsorship, to save the exhibition's centerpiece from destruction: a genuine working steam engine from 1901, coupled to a Sulzer-BBC alternator, a jewel in the crown of Mulhouse's technical and industrial heritage. It is 15 m long, weighs 170 tonnes of cast iron, steel and copper, and has a 6 m diameter wheel. Between 1901 and 1947, it supplied 900 kilowatts of electricity at 400 volts to Mulhouse's historic D.M.C. industrial textile mill. A witness to the era of the first world's fairs, it took 20,000 hours of restoration work to get it up and running again every day for multimedia sound and light shows.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Electropolis Museum, Mulhouse, France |url=https://artsandculture.google.com/partner/museum-edf-%C3%A9lectropolis |access-date=2024-05-06 |website=Google Arts & Culture |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

The “terril du puits Saint-Charles” is a fairly extensive flat slag heap where waste rock has been piling up for half a century. Between 1926 and 1931, the slag heap's shales were sorted at the coal washing center to extract the remaining coal that was used as fuel for the boilers installed on the Chanois plain.<ref name=":8">{{Harvtxt|Parietti|1999|p=41}}</ref> |

|||

In June 1993, the 15-metre-high slag heap containing 35,000 m<sup>3</sup> of shale caught fire. A neighboring plant (MagLum) had previously buried waste such as zinc, cyanide, nickel, sulfur, polyurethane foam, hydrogen sulfide, phenols and hydrocarbon derivatives there. Thick black smoke billowed over the communes of [[Ronchamp]] and [[Champagney, Haute-Saône|Champagney]], causing concern and mobilizing the population. Gas analyses and health monitoring of children were carried out (27 of them complained of various symptoms: vomiting, nausea, headaches, throat and eye irritations). Analyses revealed heavy metal content (including aluminum) 750 times higher than the norm, as well as traces of trichloroethylene and nitrate vapors. Despite the intervention of the fire department and the installation of firebreak trenches and barriers, the fire persisted for months.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Le feu dans le terril de Saint Charles |url=http://www.abamm.org/terris11.html |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref><ref name=":8" /><ref>{{Cite web |date=1994-02-07 |title=La psychose d'un ancien village minier face au terril en feu depuis neuf mois - L'Humanité |url=https://www.humanite.fr/-/-/la-psychose-dun-ancien-village-minier-face-au-terril-en-feu-depuis-neuf-mois |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=humanité |language=fr-FR}}</ref> Part of the slag heap had to be moved in 1994 to extinguish it. The slag heap was then used as backfill for a road.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Enlèvement des schistes brûlants |url=http://www.abamm.org/terris12.html |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref> The Saint-Charles pit still has a large slag heap, even though a large part of it was removed during the fire.<ref name=":6">{{Cite web |title=Le terril de Saint Charles |url=http://www.abamm.org/terris10.html |access-date=2024-05-07 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref><gallery mode="packed" widths="250"> |

|||

== Parc de la Mer Rouge == |

|||

File:2018-03 - Terril Saint-Charles - 01.jpg|General aerial view of the slag heap, shaft buildings and large offices. |

|||

The Parc de la Mer Rouge is a business park created in 1984, mainly for service sector companies.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2020-02-14 |title=La mer rouge et la Brenne |url=https://www.chateau-bouchet.com/le-chateau/la-mer-rouge-et-la-brenne/ |access-date=2024-05-06 |website=Château du Bouchet |language=fr-FR}}</ref> |

|||

File:2015-11 - Terril Saint-Charles - 14.JPG|View of the slag heap. |

|||

File:2015-11 - Terril Saint-Charles - 03.JPG|The summit. |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

== Workshops and offices == |

|||

[[File:Ateliers-Bureaux-Ronchamp XXe 01.jpg|thumb|Large offices and workshops.]] |

|||

{{Coord|47.702515|6.653095}} |

|||

Shortly after the opening of the shaft and its good results, the company decided to set up its central workshops and offices next to the shaft and established a link with the rail network. These facilities remained the nerve center of the collieries until their closure in 1958.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Les ateliers de réparation des mines |url=http://www.abamm.org/ateliers.html |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref> The site was converted into a car manufacturing subcontracting plant before being decommissioned in 2008. At the beginning of the 21st century, the site was used for exhibitions and shooting games. |

|||

== The station == |

|||

[[File:Puits Saint-Charles XXe - 01.JPG|thumb|Loading coal wagons at the shaft exit.]] |

|||

{{Coord|47.703343|6.653262}} |

|||

Once the coal carts have been hauled up from the Saint-Charles shaft, they are emptied into large wagons. The wagons are transferred to a station close to the shaft via a railroad built in 1858, before the coal is shipped to the coal mine's customers, most of whom are from [[Alsace]], via the Paris-Est to [[Mulhouse-Ville station|Mulhouse-Ville]] railroad.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Le réseau ferré entre les puits |url=http://www.abamm.org/resferre.html |access-date=2024-05-08 |website=www.abamm.org}}</ref> |

|||

The station was in operation from the mid-19th century until 1958, when the mines closed, after which it was dismantled. At the beginning of the 21st century, the station site was overgrown, and only a few remnants of the installations and network remained. |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

*[[Ronchamp coal mines]] |

|||

*[[Mining in France]] |

|||

*[[Sainte-Barbe Coal Mine]] |

|||

*[[Cokerie-lavoir du Chanois]] |

|||

== References == |

== References == |

||

| Line 104: | Line 99: | ||

== Notes == |

== Notes == |

||

<references group="notes" /> |

<references group="notes" /> |

||

== Bibliography == |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Parietti |first=Jean-Jacques |title=Les Houillères de Ronchamp |date=2001 |publisher=Éditions Comtoises |isbn=2-914425-08-2}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Parietti |first=Jean-Jacques |title=Les Houillères de Ronchamp, vol. 2: Les mineurs |date=2010 |publisher=Franche-Comté culture & patrimoine |isbn=978-2-36230-001-1}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Parietti |first=Jean-Jacques |title=Le puits Saint-Charles, coll. Les dossiers de la Houillère |date=1999 |publisher=Ronchamp, Association des amis du musée de la mine}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Mathet |first=François |url=http://jubilotheque.upmc.fr/ead.html?id=GR_000387_001 |title=Mémoire sur les mines de Ronchamp |date=1882 |publisher=Société de l'industrie minérale}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=PNRBV |title=Le charbon de Ronchamp : circuits miniers de Ronchamp, coll. « Déchiffrer le patrimoine » |date=1999 |publisher=Parc naturel régional des Ballons des Vosges |isbn=2-910328-31-7}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |title=Société de l'industrie minérale, Bulletin trimestriel |date=1882 |publisher=Saint-Étienne}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Thirria |first=Édouard |title=Manuel à l'usage de l'habitant du département de la Haute-Saône |date=1869}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Godard |first=Michel |title=Enjeux et impacts de l'exploitation minière du bassin houiller de Ronchamp |date=2012}} |

|||

[[fr: Puits Saint-Charles]] |

|||

[[Category:Ronchamp coal mines]] |

|||

Revision as of 15:51, 21 May 2024

surface installations | |

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Country | France |

| Production | |

| Type | shaft |

| History | |

| Opened | September 14, 1845 |

| Active | August 19, 1847 |

The Saint-Charles shaft (or No. 8 shaft) is one of the main collieries of the Ronchamp coal mine. It is located in Ronchamp, Haute-Saône, in eastern France. In the second half of the nineteenth century, this shaft made it possible to mine large coal seams, contributing to the company's golden age.

Saint-Charles has been open for over fifty years, a long life compared to other open shafts in the Ronchamp mining basin. It has also experienced mining disasters such as fires and firedamp blasts. The shaft is distinguished by its revolutionary extraction system using a cleat machine. The process, too complex, was eventually abandoned following technical setbacks.

After closure, the pit buildings were converted into housing; the slag heaps were re-used between the wars, as they were still rich in coal. At the end of the twentieth century, these same slag heaps, which had become a dumping ground for a nearby factory, burst into flames, frightening the local population.

Situation before sinking

After the Saint-Louis shaft was sunk in the hamlet of La Houillère in 1810, the company dug a series of shafts close to the outcrops, varying in depth from 19 to 165 meters. But the last shafts dug around 1830, found no coal. Shaft no. 5, continued by drilling, found no trace of coal, and shaft no. 6 stumbled on an uplift in the coalfield linked to a fault. In 1839, shaft no. 7 was sunk in search of coal. However, with the company bankrupt, the concession was put up for sale and the sinking stopped.

In 1843, Charles Demandre and Joseph Bezanson bought the Ronchamp concession and continued sinking shaft no. 7. They finally found coal at 205 meters, behind the uplift.[1] Shortly after the No. 7 shaft was commissioned, borehole X was drilled on the Champagney plain, uncovering significant coal seams. On August 28, 1845, a prefectoral decree authorized the digging of shaft no. 8.[2]

Sinking

Sinking of the shaft began on September 11, 1845, with a rectangular cross-section measuring 4.64 meters × 2.14 meters; the extraction chamber measures 1.70 meters × 1.76 meters.[2] By the end of 1846, it had reached a depth of 180 meters. A 60-hp steam engine was installed. On August 19, 1847, at a depth of 225.80 meters, the first layer was encountered, with a thickness of 2.50 meters of pure coal.[3]

To exploit the first layer immediately, the company uses the “sous stot” digging technique: a second shaft is dug parallel to the main shaft from the first layer. Once the intermediate layer has been reached, a gallery is dug under the main shaft and continues to the second layer. When both sections are completed, a junction is made. Digging lasted from September 1847 to April 1848.[4]

Operation

In 1848, a steam engine consisting of a single vertical cylinder with a diameter of 49 centimeters and a stroke of 1.356 meters was installed. This was a Meyer machine manufactured in the Expansion workshops, with a flywheel six meters in diameter. The extraction machine's pendulum is supported by two cast-iron columns, and vertical guides frame the piston. The manual braking system was replaced by a steam brake. The machine is rated at 60 hp6. The extraction compartment has only two guides, and the cages slide on either side of them. The cages can only hold one 315-kg carriage. Rolling is carried out by wheelbarrow in the galleries and with carts on cast-iron or wooden rails. In the same year,[notes 1] a large 700-metre-long inclined plane was built to follow the coal bed.[5]

In 1850, 57,413 tonnes of coal were extracted from the bowels of the Saint-Charles shaft. The latter exploited some of the most important veins in the Ronchamp coalfields, including a four-metre-thick layer in 1862 and a three-metre-thick layer discovered four years later.[6] In June 1861, the Saint-Charles pit continued to operate without interruption, extracting 2,585 tonnes of coal. However, this was no longer the most productive pit, as the Saint-Joseph pit extracted 6,258 tonnes and the Sainte-Barbe pit 2,622 tonnes in the same month.[7] Production amounted to 24,292.[7] tons in 1861, 30,205.7 tons in 1862 and 67,036 tons in 1863.[8]

In 1868, the most important part of the second layer was mined and production reached 100 tonnes per day. At the same time, the link with the Sainte-Marie shaft was completed, facilitating ventilation.[9] By 1873, all mining at the Saint-Charles shaft was taking place in the second layer on floors 260 and 315, and consideration was being given to mining the intermediate layer (located between the first and second layers).[9] Three years later, in January, 2,610 tonnes of coal, 550 cubic metres of water and 673 tonnes of spoil were brought up from the shaft.[9] In 1877, a telephone was installed to communicate with the bottom of the shaft.[10]

The cleat machine

By 1849, operations at the Saint-Charles shaft gradually expanded to the south, east, and west. The company considered sinking another well (the Saint-Joseph well, which would be sunk the following year), but sinking a well can take five to six years, and the company needed immediate resources. It therefore decided to sink an inclined plane at the same time as the Saint-Joseph shaft, to reach the area to be mined more quickly. The breakthrough of this descending gallery began in December 1849. It was initially equipped with a horse-drawn carousel, but this system was not sufficiently efficient, so the engineers thought of a new mining system: the cleat machine.[11]

A cleat machine has already been installed at the bottom of Compagnie des Mines d'Anzin's Davy pit in La Sentinelle, in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais coalfield, and the collieries have decided to use the same system at Ronchamp. Initially, a single circuit is to start from the Saint-Joseph shaft, then follow the inclined plane before climbing back up through the Saint-Charles shaft.[12]

In 1850, more than 200 meters below the surface, a steam engine and two boilers were installed in a large room close to the coal beds. The room, 50 meters from the shaft, is 17 meters long, 8 meters wide, and 4 meters high, and is supported by a massive oak framework, some parts of which are 40 cm square. This steam engine powers the cleat machine installed in the 700-meter-long inclined plane. The underground machines and boilers were supplied by Sthelier of Thann, as were the engine and all the cleat equipment for the vertical shaft. These elements were installed and ready for use on May 20, 1852. Until 1853, major mechanical operating problems were encountered, but these were resolved as testing progressed. Engineer Schutz was one of the instigators of this initiative, the machinery having been invented by Mr. Mehus 1. Conversely, engineer Mathet, who joined the company in 1855, was highly critical of the system and its adoption, finding it dangerous for miners' lives due to the drought that could disrupt ventilation and even cause firedamp. He also described the fragility of the woodwork and the high temperatures the drivers had to endure.[13] On October 19, the underground boilers were lit, but immediately the fire, fanned by the 250-meter-high chimney, sucked all the air out of the mine. As a result, ventilation was difficult, and the workings were invaded by firedamp. On March 12, 1853, the inclined plane's cleat machine was put into operation. The water accumulated at the bottom of the large chute is evacuated by hand pumps installed at the top and bottom of the inclined plane over 200 meters. These pumps were operated by women. But on April 1, despite all the precautions taken, a fire broke out in the woods near the boilers.[6]

In 1855 and again in 1856, the Saint-Charles shaft produced 54,081 tonnes of coal thanks to the cleat machine. That same year, however, the decision was made to abandon this machine. At the same time, the women were dismissed from mine 1. The following year, the machine was dismantled and replaced by a wheel mining machine. This set in motion two cables, one ascending, the other descending, and vice-versa. Each cable was guided by two parallel wooden sills.[14]

In May 1852, a second machine of the same type, but vertical, was put into service over the entire height of the shaft, replacing the Meyer coil machine. It too suffered numerous breakdowns, requiring frequent shutdowns to readjust various parts over several months and in the years that followed. Finally, on March 29, 1857, the Board of Directors decided to return to the cable extraction system, and the vertical cleat machine was dismantled in 48 days, starting the following May 17. A 9-meter-high wooden headframe was built over the shaft, and the Meyer machine was refurbished.[15]

Accidents and disasters

Three firedamp blasts occurred in 1857: eight miners perished on January 29, two on March 3, and two on March 14.[6] On March 16, the entire workforce went on strike of these disasters. The shaft was deemed too dangerous, with poor ventilation and faulty equipment. The management lodged a complaint for coalition offenses, but the Haute-Saône prefecture ruled in favor of the miners, and the engineer was sentenced to prison for flagrant breaches of safety.[16]

On November 8, 1857, a fire broke out in the underground boiler room. The openings of shafts no. 7 and Saint-Charles are hermetically sealed. On January 18 the following year, a dog and a lighted lamp descended to the bottom of the shaft to test for the presence of a firedamp. On January 30, the openings in both shafts were reopened. However, energetic ventilation rekindled the fire in the coal. In 1859, water flooded the mine after more than six months of inactivity.[6]

In 1886, the shaft was bricked up from top to bottom, with a diameter of 3.30 meters. At the bottom, for the first time in Ronchamp, metal frames were installed over a kilometer of the gallery. Unfortunately, in June of the same year, another firedamp explosion killed twenty-three people.[6]

The ending

After the 1886 disaster, a large part of the galleries and the construction site were destroyed, in addition, forty years of intensive mining had greatly depleted the deposit, leaving the shaft virtually abandoned. But three years later, strong demand for coal prompted the company to rehabilitate the entire site and resume mining.[17]

In 1891, the pit was fitted out to accommodate around a hundred workers, but two years later, work was again halted, and only water was brought up from the shaft.[18] The following year, mining was resumed to remove the remains of coal panels,[notes 2] estimated to weigh 10,000 tonnes. They were excavated at a rate of 100 tonnes per day by around one hundred workers.[18] In October 1895, the workers completed the stripping[notes 3] and proceeded with the clearing.[notes 4] This work was completed in December of the same year. The shaft was then backfilled.[18]

Conversion

The shaft was backfilled from January to June 1896 at around ten carloads of shale per day. In May, an eight-meter-thick plug of clay and concrete was installed to make the shaft watertight.[19] The surface installations were demolished, except the machine building, which was converted into housing, and another building which housed accommodation and the “La Ruche” store.[20] The adjacent store was demolished in 2005 after being destroyed by fire.[21]

At the beginning of the 21st century, several of the pit's buildings still stand, including the well-preserved mining machine building, repainted white, and the large building housing the mine masters and the canteen. All these buildings have now been converted into housing.[22]

-

The floor of the Saint-Charles well in 2015.

-

Area where the well is located.

Mining town and shops

47°42′09″N 6°39′11″E / 47.702515°N 6.653095°E

In 1866, a food and clothing store was built on the site of the Saint-Charles well, next to the offices. It was later expanded to include a bakery and butcher's shop, and named “La Ruche”. The store was run by the company, and miners' purchases were deducted directly from their wages via their order and payroll books. After the Second World War, the store became a cooperative limited company with shares on the stock exchange.[20]

To accommodate the large workforce employed at the Saint-Charles shaft, a mining housing estate was built in 1872, a few dozen meters from the pithead. It consisted of four houses built of roughcast sandstone rubble, each with a single storey and long-sloped mechanical tile roofs.[23][24][25] Although the collieries had originally intended to build 24 dwellings, they had to give up for financial reasons. Each house is divided into four units, with two bedrooms, a kitchen, a cellar, an attic, and a garden for each family.[23] On March 11, 2010, the houses were listed in the general inventory of cultural heritage.[24]

The slag heap

The “terril du puits Saint-Charles” is a fairly extensive flat slag heap where waste rock has been piling up for half a century. Between 1926 and 1931, the slag heap's shales were sorted at the coal washing center to extract the remaining coal that was used as fuel for the boilers installed on the Chanois plain.[26]

In June 1993, the 15-metre-high slag heap containing 35,000 m3 of shale caught fire. A neighboring plant (MagLum) had previously buried waste such as zinc, cyanide, nickel, sulfur, polyurethane foam, hydrogen sulfide, phenols and hydrocarbon derivatives there. Thick black smoke billowed over the communes of Ronchamp and Champagney, causing concern and mobilizing the population. Gas analyses and health monitoring of children were carried out (27 of them complained of various symptoms: vomiting, nausea, headaches, throat and eye irritations). Analyses revealed heavy metal content (including aluminum) 750 times higher than the norm, as well as traces of trichloroethylene and nitrate vapors. Despite the intervention of the fire department and the installation of firebreak trenches and barriers, the fire persisted for months.[27][26][28] Part of the slag heap had to be moved in 1994 to extinguish it. The slag heap was then used as backfill for a road.[29] The Saint-Charles pit still has a large slag heap, even though a large part of it was removed during the fire.[24]

-

General aerial view of the slag heap, shaft buildings and large offices.

-

View of the slag heap.

-

The summit.

Workshops and offices

47°42′09″N 6°39′11″E / 47.702515°N 6.653095°E

Shortly after the opening of the shaft and its good results, the company decided to set up its central workshops and offices next to the shaft and established a link with the rail network. These facilities remained the nerve center of the collieries until their closure in 1958.[30] The site was converted into a car manufacturing subcontracting plant before being decommissioned in 2008. At the beginning of the 21st century, the site was used for exhibitions and shooting games.

The station

47°42′12″N 6°39′12″E / 47.703343°N 6.653262°E

Once the coal carts have been hauled up from the Saint-Charles shaft, they are emptied into large wagons. The wagons are transferred to a station close to the shaft via a railroad built in 1858, before the coal is shipped to the coal mine's customers, most of whom are from Alsace, via the Paris-Est to Mulhouse-Ville railroad.[31]

The station was in operation from the mid-19th century until 1958, when the mines closed, after which it was dismantled. At the beginning of the 21st century, the station site was overgrown, and only a few remnants of the installations and network remained.

See also

References

- ^ Parietti (2001, p. 17)

- ^ a b François Mathet (1882, pp. 137 144)

- ^ Parietti (1999, p. 3)

- ^ Parietti (1999, p. 4)

- ^ Parietti (1999, p. 5)

- ^ a b c d e "Les puits creusés dans le bassin houiller de ronchamp". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-07.

- ^ a b Parietti (1999, p. 34)

- ^ Michel Godard (2012, p. 336)

- ^ a b c Parietti (1999, p. 35)

- ^ Parietti (1999, p. 36)

- ^ Parietti (1999, p. 8)

- ^ Parietti (1999, pp. 8–9)

- ^ François Mathet (1882, pp. 139–140)

- ^ Parietti (1999, p. 7)

- ^ François Mathet (1882, pp. 141–173)

- ^ Jean-Jacques Parietti (2010, p. 91)

- ^ Parietti (1999, p. 39)

- ^ a b c Parietti (1999, p. 40)

- ^ Parietti (1999, pp. 40–55)

- ^ a b PNRBV, p. 24)

- ^ "Ancien magasin La Ruche". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ "Le puits Saint Charles". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ a b PNRBV, p. 25)

- ^ a b c "Le terril de Saint Charles". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-07.

- ^ "La cité Saint Charles". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ a b Parietti (1999, p. 41)

- ^ "Le feu dans le terril de Saint Charles". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ "La psychose d'un ancien village minier face au terril en feu depuis neuf mois - L'Humanité". humanité (in French). 1994-02-07. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ "Enlèvement des schistes brûlants". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ "Les ateliers de réparation des mines". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ "Le réseau ferré entre les puits". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

Notes

- ^ Jacking” involves digging a mine shaft from the surface. By extension, any excavation of a steeply inclined structure can be described as jacking. This includes not only the excavation, but also the removal of spoil and the initial lining.

- ^ The panels are large-area pillars or unused mine areas.

- ^ When a mine or shaft is mined, galleries are dug in a checkerboard pattern to extract the coal, forming regular, square natural pillars. When all the galleries have been dug, these pillars, which contain a lot of coal, are removed. This is known as “de-piling”.

- ^ When digging the galleries, natural pillars are not enough, so wooden beams are installed. At the end of the operation, they are reclaimed. This is known as “deforestation”.

Bibliography

- Parietti, Jean-Jacques (2001). Les Houillères de Ronchamp. Éditions Comtoises. ISBN 2-914425-08-2.

- Parietti, Jean-Jacques (2010). Les Houillères de Ronchamp, vol. 2: Les mineurs. Franche-Comté culture & patrimoine. ISBN 978-2-36230-001-1.

- Parietti, Jean-Jacques (1999). Le puits Saint-Charles, coll. Les dossiers de la Houillère. Ronchamp, Association des amis du musée de la mine.

- Mathet, François (1882). Mémoire sur les mines de Ronchamp. Société de l'industrie minérale.

- PNRBV (1999). Le charbon de Ronchamp : circuits miniers de Ronchamp, coll. « Déchiffrer le patrimoine ». Parc naturel régional des Ballons des Vosges. ISBN 2-910328-31-7.

- Société de l'industrie minérale, Bulletin trimestriel. Saint-Étienne. 1882.

- Thirria, Édouard (1869). Manuel à l'usage de l'habitant du département de la Haute-Saône.

- Godard, Michel (2012). Enjeux et impacts de l'exploitation minière du bassin houiller de Ronchamp.