Yellowdesk (talk | contribs) →Highest dollar schemes: Removed {{Current}} tag. This tag is intended for articles edited by hundreds on the same day. See: Template talk:Current#Policy for using {{current}} |

|||

| Line 93: | Line 93: | ||

* [[High Yield Investment Program]]s are related to established economic rules such as supply and demand, material assets that appreciate based on value-added through high-end skills such as high-end electronics, buidings & estates, hotels, technology parks, museums, theater and organic systems such as businesses involved in producing the previously mentioned material assets. HYIPs could involve printing of cards as certificates, with units being transferable to third parties. The monetary value of units rises over time, so most holders of such cards won't want to transfer their units. At the same time, the card can be used as a means of exchange for value making it a form of money. It's like turning the HYIPs into a form of Central Bank and the units it issues become currency. |

* [[High Yield Investment Program]]s are related to established economic rules such as supply and demand, material assets that appreciate based on value-added through high-end skills such as high-end electronics, buidings & estates, hotels, technology parks, museums, theater and organic systems such as businesses involved in producing the previously mentioned material assets. HYIPs could involve printing of cards as certificates, with units being transferable to third parties. The monetary value of units rises over time, so most holders of such cards won't want to transfer their units. At the same time, the card can be used as a means of exchange for value making it a form of money. It's like turning the HYIPs into a form of Central Bank and the units it issues become currency. |

||

* On [[July 25]], [[2007]], Glyn Richards of Cherry Hill, New Jersey was arrested for taking in multiples of $25,000.00 with a promise of a monthly $9000 payment for 4 months, returning $36,000 total. The scheme was that his company, All Freight Logistics, had a contract with the U.S. Department of Defense for transporting military equipment to and from Iraq\Iran during the time of war. Richards took in more than $10 million dollars from Investors nationwide, with an unknown amount returned. [http://www.courierpostonline.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20070725/NEWS01/70725031/1006] |

|||

== As a political metaphor == |

== As a political metaphor == |

||

Revision as of 18:26, 26 July 2007

A Ponzi scheme is a fraudulent investment operation that involves paying abnormally high returns ("profits") to investors out of the money paid in by subsequent investors, rather than from net revenues generated by any real business, named after Charles Ponzi.

Overview

A Ponzi scheme usually offers abnormally high short-term returns in order to entice new investors. The high returns that a Ponzi scheme advertises (and pays) require an ever-increasing flow of money from investors in order to keep the scheme going.

The system is doomed to collapse because there are little or no underlying earnings from the money received by the promoter. However, the scheme is often interrupted by legal authorities before it collapses, because a Ponzi scheme is suspected and/or because the promoter is selling unregistered securities. As more and more investors become involved, the likelihood of the scheme coming to the attention of authorities will continue to increase.

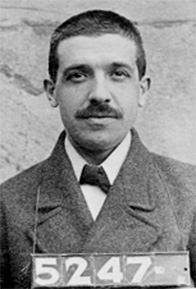

The scheme is named after Charles Ponzi, who became notorious for using the technique after emigrating from Italy to the United States in 1903. Ponzi was not the first to invent such a scheme, but his operation took in such a large amount of money that it was the first to become known throughout the United States. Today's schemes are often considerably more sophisticated than Ponzi's, although the underlying formula is quite similar and the principle behind every Ponzi scheme is to exploit lapses in judgment arising out of greed.

Hypothetical example

An advertisement is placed promising extraordinary returns on an investment – for example 20% for a 30 day contract. The precise mechanism for this incredible return can be attributed to anything that sounds good but is not specific: "global currency arbitrage", "hedge futures trading", "high yield investment programs", or similar.

With no proven track record for the investors, only a few investors are tempted, usually for smaller sums (say $5,000). Sure enough, 30 days later, the investor receives $6,000 – the original capital plus the 20% return ($1,000). At this point, greed starts to overcome reason: the investor will put in more money, and, as word begins to spread, other investors grab the "opportunity" to participate. More and more people invest, and see their investments return the promised large returns.

The reality of the scheme is that the "return" to the initial investors is being paid out of the new, incoming investment money, not out of profits. There is no "global currency arbitrage", "hedge futures trading", or "high yield investment programs" actually taking place. Instead, when Investor D puts in money, that money becomes available to pay out "profits" to investors A, B, and C. When investors X, Y, and Z put in money, that money is available to pay "profits" to investors A through W.

One reason that the scheme works so well is that early investors – those who actually got paid the large returns – quite commonly reinvest (keep) their money in the scheme (it does, after all, pay out much better than any alternative investment). Thus those running the scheme don't actually have to pay out very much (net) – they simply have to send statements to investors that show how much the investors have earned by keeping the money in what looks like a great place to get a high return.

The catch is that at some point one of three things will happen: (a) the promoters will vanish, taking all the investment money (less payouts) with them; (b) the scheme will collapse of its own weight, as investment slows and the promoters start having problems paying out the promised returns (and when they start having problems, the word spreads, and more people start asking for their money); or (c) the scheme is exposed, because when legal authorities begin examining accounting records of the so-called enterprise, they find that much of the "assets" that should exist, do not.

What is and is not a Ponzi scheme

- A pyramid scheme is a form of fraud similar in some ways to a Ponzi scheme, relying as it does on a disbelief in financial reality, including the hope of an extremely high rate of return. However, several characteristics distinguish pyramid schemes from Ponzi schemes:

- In a Ponzi scheme, the schemer acts as a “hub” for the victims, interacting with all of them directly. In a pyramid scheme, those who recruit additional participants benefit directly (in fact, failure to recruit typically means no investment return).

- A Ponzi scheme relies on some esoteric investment approach, insider connections, etc., and often attracts well-to-do investors; pyramid schemes explicitly claim that new money will be the source of payout for the initial investments.

- A pyramid scheme is bound to collapse a lot faster, simply because of the demand for exponential increases in participants to sustain it (Ponzi schemes can survive simply by getting most participants to "reinvest" their money, with a relatively small number of new participants).

- A bubble. A bubble relies on suspension of disbelief and an expectation of large profits, but it is not the same as a Ponzi scheme. A bubble involves ever-rising (and unsustainable) prices in an open market (be that shares of a stock, housing prices, the price of tulip bulbs, or anything else). As long as buyers are willing to pay ever-increasing prices, sellers can get out with a profit. And there doesn't need to be a schemer behind a bubble. (In fact, a bubble can arise without any fraud at all - for example, housing prices in a local market that rise sharply but eventually drop sharply because of overbuilding.)

- Robbing Peter to pay Paul. When debts are due and the money to pay them is lacking, whether because of bad luck or deliberate theft, debtors often make their payments by borrowing or stealing from other monies they have. It does not follow that this is a Ponzi scheme. From the basic facts set out, it is not, because there is no indication that the lenders were promised unrealistically high rates of return via claims of unusual financial investments. Nor (from these basic facts) is there any indication that the borrower (banker) is progressively increasing the amount of borrowing ("investing") to cover payments to initial investors (as, again, Ponzi was not the first to do.)

Notable Ponzi schemes

Highest dollar schemes

The eponymous scheme was orchestrated by Charles Ponzi, who went from anonymity to being a well-known Boston millionaire in six months using such a scheme in 1920. Profits were supposed to come from exchanging international postal reply coupons. He promised 50% interest (return) on investments in 45 days or “double your money” in 90 days. About 40,000 people invested about $15 million all together (roughly $150 million in 2006 dollars); in the end, only a third of that money was returned to them.

Besides the Ponzi scheme other similar historic schemes include:

- Before Ponzi, in 1899 William "520 Percent" Miller opened for business as the "Franklin Syndicate" in Brooklyn, New York. Miller promised 10% a week interest and exploited some of the main themes of Ponzi schemes such as customers reinvesting the interest they made. He defrauded buyers of $1 million and was sentenced to jail for 10 years. When he was pardoned he opened a grocery store on Long Island. During the Ponzi investigation, Miller was interviewed by the Boston Post to compare his scheme to Ponzi's — the interviewer found them remarkably similar, but Ponzi's became more famous for taking in seven times as much money.[1]

- Between 1970 and 1984 in Portugal, a woman known as Dona Branca maintained a scheme that paid 10% monthly interest. In 1988 she was sentenced to 10 years in prison. She always claimed that she was only trying to help the poor, but in her trial it was proven that she had received the equivalent of 85 million Euro.[2][3]

- MMM was a Russian company that existed in the 1990s. It involved at least two million people and collected as much as $1.5 billion. The founder was sentenced to 4.5 years in prison in 2007.

- In autumn of 1994, the European Kings Club collapsed, causing a damage of about $1.1 billion. This scam was led by Damara Bertges and Hans Günther Spachtholz. In the Swiss cantons Uri and Glarus about every tenth adult invested into the EKC. The scam involved buying "letters" valued at 1,400 francs that entitled buyers to receive 12 monthly payments of 200 francs. The organisation was based in Gelnhausen, Germany.[4]

- In May 1995, Pennsylvania's attorney general moved to freeze the assets of the Foundation for New Era Philanthropy and its chairman, John G. Bennett, Jr. The organization had raised over $500 million from 1,100 donors. Participants, including the Red Cross, had believed they were participating in a matching-gifts program through New Era but, in fact it was simply a Ponzi scheme. Losses amounted to $135 million.

- In early 1996, the SEC filed a civil action against Bennett Funding Group, its chief financial officer, Patrick R. Bennett, and other companies Bennett controlled, in connection with a massive Ponzi scheme. The companies fraudulently raised hundreds of millions of dollars, purportedly to purchase assignments of equipment leases and promissory notes. [1]

- In 1997 the government of Albania officially endorsed a series of pyramid investment funds. When the inevitable end came, the people of Albania, who had lost $1.2 billion, took their protest to the streets in a revolt that toppled the government.

- In 2000, a Ponzi scheme perpetrated by Scientology minister Reed Slatkin came unraveled when the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission regulators became aware that Slatkin was not a licensed investment adviser. Slatkin had raised some $600 million from over 500 wealthy investors, mostly Hollywood celebrities.

- In December 2005, in Los Angeles, California, Larry Toshio Osaki, who ran a gigantic Ponzi scheme and continued to offer bogus investments in accounts receivable "factoring" after being ordered to stop by a federal judge, was sentenced to 20 years in federal prison. In addition to the prison term, Judge Stephen V. Wilson ordered Osaki to pay more than $145 million in restitution to victims.

- In May 2006, James Paul Lewis, Jr. was sentenced to 30 years in federal prison for running a $311 million Ponzi scheme over a 20-year time period. He operated under the name Financial Advisory Consultants from Lake Forest, California

- In October 2006, in Malaysia, two prominent members of society and several others were held for running an alleged scam, known as SwissCash or Swiss Mutual Fund (1948). SwissCash offered a returns of up to 300% within a 15-month investment period. Currently, this HYIP investment is offered to citizens of Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia. It claimed investors’ funds were channeled to business activities ranging from oil exploration to shipping and agriculture in the Caribbean. The company claims to be operating out of New York and incorporated in Commonwealth of Dominica.[5] [6] [7]

- On Friday 13 April 2007 a person named Sibt-e-Hassan Shah aka "Double Shah" was arrested by government officials in Wazirabad, a small town of Pakistan. [2]. Sibt-e-Hassan claimed to double the money within 30 days in the beginning of his scheme and later 90 days. He is suspected to have gathered very large investments (approx US$ 1 Billion) in a very short time period.

- The Brothers was a large investment operation, eventually revealed to be a Ponzi scheme, in Costa Rica from the late 1980s until 2002. The fund was operated by brothers Luis Enrique and Osvaldo Villalobos. Investigators determined that the scam took in at least $400 million. Most of the clientele were American and Canadian retirees but some Costa Ricans also invested the minimum $10,000. About 6,300 individuals ultimately were involved. Interest rates were 3% per month, usually paid in cash, or 2.8% compounded. The ability to pay such high interest was attributed to Luis Enrique Villalobos’ existing agricultural aviation business, investment in unspecified European high yield funds, and loans to Coca Cola, among others. Osvaldo Villalobos’ role was primarily to move money around a large number of shell companies and then pay investors. In May 2007 Osvaldo Villalobos was sentenced to 18 years in prison for fraud and illegal banking. Luis Enrique Villalobos remains a fugitive. [3]

- The Enron company was itself essentially a Ponzi scheme, which took its profits and the retirement funds of its employees and plowed them into driving their stock price higher, until the scheme was uncovered.

- On Wednesday July 4, 2007, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas and the Securities and Exchange Commission (Philippines) cited FrancSwiss Financial Co. as a Ponzi scheme which targeted Overseas Filipino Workers.

Other notable schemes

Other notable (but lesser dollar) Ponzi schemes include:

- Sarah Howe, who in 1880 opened up a "Ladies Deposit" in Boston promising eight percent interest, although she had no method of making profits. This unique scheme was billed as "for women only". Howe disappeared with the money from her scam.[1]

- The novel Chance by Joseph Conrad depicted a Ponzi scheme in 1914 before Ponzi himself had hit the scene. Conrad's scammer "de Barral" offered ten percent interest on deposits in his operation "without system, plan, foresight, or judgement".

- On March 22, 2000, four people were indicted in the Northern District of Ohio, on charges including conspiracy to commit and committing mail and wire fraud. A company with which the defendants were affiliated allegedly collected more than $26 million from "investors" without selling any product or service, and paid older investors with the proceeds of the money collected from the newer investors. [4]

- In late 2003, a scheme by Bill Hickman, Sr., and his son, Bill Jr., was shut down. He had been selling unregistered securities that promised yields of up to 20 percent; more than $8 million was defrauded from dozens of residents of Pottawatomie County, Oklahoma, along with investors from as far away as California. [5] Hickman was sentenced to 160 years in state prison.

- In December 2004, Mark Drucker pleaded guilty to a Ponzi scheme in which he told investors that he would use their funds to buy and sell securities through a brokerage account. He claimed that he was making significant profits on his day trades and that he had opportunities to invest in select IPOs that were likely to turn a substantial profit in a short period of time. He promised guaranteed returns of up to fifty (50%) percent in 90 days or less. In less than two years of trading, Drucker actually lost more than $850,000 in day trading and had no special access to IPOs. He paid out more than $3.6 million to investors while taking in $6.3 million. [6] [7]

- In June 2005, in Los Angeles, California, John C. Jeffers was sentenced to 168 months (14 years) in federal prison and ordered to pay $26 million in restitution to more than 80 victims. Jeffers and his confederate John Minderhout ran what they said was a high-yield investment program they called the “Short Term Financing Transaction.” The funds were collected from investors around the world from 1996 through 2000. Some investors were told that proceeds would be used to finance humanitarian projects around the globe, such as low-cost housing for the poor in developing nations. Jeffers sent letters to some victims that falsely claimed the program had been licensed by the Federal Reserve and the program had a relationship with the International Monetary Fund and the United States Treasury. Jeffers and Minderhout promised investors profits of up to 4,000 percent. Most of the money collected in the scheme went to Jeffers to pay commissions to salespeople, to make payments to investors to keep the scheme going, and to pay his own personal expenses. [8]

- In February 2006, Edmundo Rubi pleaded guilty to bilking hundreds of middle and low-income investors out of more than $24 million between 1999 and 2001, when he fled the U.S. after becoming aware that he was under suspicion. The investors in the scheme, called “Knight Express”, were told that their funds would be used to purchase and resell Federal Reserve notes, and were promised a six percent monthly return. Most of those bilked were part of the Filipino community in San Diego. [9]

- On May 10, 2006, Spanish police arrested 9 people associated with Forum Filatelico and Afinsa Bienes Tangibles in an apparent Ponzi scheme that affected 250,000 investors from 1998 to 2001. Investors were promised huge returns from investments in a stamp fund. [10]

- 12DailyPro was a version of what is commonly known as a "paid autosurf" program where "investors" deposited money and received an extremely high profit (44%) within a short period (12 days). Charis Johnson created what authorities considered one of the largest modern day versions of the Ponzi scheme. She accumulated a total of over US$1.9 million from the program. More than 300,000 people joined over the course of 8 months, spending over $500 million [11]. When a federal investigation of 12DailyPro took place, its main payment processor, Stormpay, froze all funds related to it. Stormpay has since refused to return any of these funds. On February 24, 2006, the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) ordered 12DailyPro and its parent company to cease and desist all operations. On February 28, a Los Angeles judge ordered all company assets and records to be turned over to an appointed receiver for investigation. Charis F. Johnson now faces criminal and civil suits from both local and federal agencies.

- High Yield Investment Programs are related to established economic rules such as supply and demand, material assets that appreciate based on value-added through high-end skills such as high-end electronics, buidings & estates, hotels, technology parks, museums, theater and organic systems such as businesses involved in producing the previously mentioned material assets. HYIPs could involve printing of cards as certificates, with units being transferable to third parties. The monetary value of units rises over time, so most holders of such cards won't want to transfer their units. At the same time, the card can be used as a means of exchange for value making it a form of money. It's like turning the HYIPs into a form of Central Bank and the units it issues become currency.

- On July 25, 2007, Glyn Richards of Cherry Hill, New Jersey was arrested for taking in multiples of $25,000.00 with a promise of a monthly $9000 payment for 4 months, returning $36,000 total. The scheme was that his company, All Freight Logistics, had a contract with the U.S. Department of Defense for transporting military equipment to and from Iraq\Iran during the time of war. Richards took in more than $10 million dollars from Investors nationwide, with an unknown amount returned. [12]

As a political metaphor

Some free-market economists, such as Thomas Sowell have argued that national social security systems, such as the Social Security system in the United States and the National insurance system in the United Kingdom, are actually large-scale Ponzi schemes.

Sowell and others point out that, under these national systems, incoming payments, made up of taxes and/or other kinds of non-voluntary contributions, are neither saved nor invested. Instead, current contributions (from one set of individuals, due benefits at a later time) are used to pay for current benefits (to another set of individuals).

Sowell and others claim that this "pay-as-you-go" system has begun to show its inherent flaws as North American demographics trend toward more pensioners and fewer workers, because of declining birth rates and increasing life expectancy.

Retirement programs run by national governments, though they involve the taxes paid in by workers being redistributed to pensioners, nevertheless differ in a number of basic features that are usually found in Ponzi schemes, but are not fundamental to them:

- Retirement systems, like Social Security, are openly declared for what they are. In a genuine Ponzi scheme, the perpetrators falsely claim that there is some business that generates the promised revenues. In Social Security, people know where the money comes from, and actuaries supply written predictions of future cash in-flows and out-flows.

- Retirement systems promise a stipend to the country's retired persons, not the quick and exorbitant profits to current investors that Ponzi schemes invariably offer.

- Retirement systems rely on the taxing power of the state to ensure continuous funding. In practice, this taxing power has been used primarily for dedicated revenues (taxes), although in theory general tax revenues could be used to supplement worker payments into the systems. (Historically in the U.S., Social Security has almost always been in surplus, so this has not yet become an issue.) When and if the political process is used to raise required contributions via retirement taxes, or to reduce benefits (including raising the retirement age), either across the board or just for the better-off, there would certainly be opposition from those who would pay more or get less, but politicians have only those two choices (plus borrowing) if revenues are inadequate.

- The idea of making Social Security a "fully funded" system has been discussed several times but always floundered on the cost. The cost has gone up as making any fundamental change has been deferred.

- In the long run, retirement systems pay out an approximately equal amount to what was paid in, per contributor, plus interest [citation needed]. In the short run, pension surpluses can be used to cover a government's current general-revenue shortfall, as has been happening in the United States since Social Security contribution rates were increased in 1983.

- Retirement systems are in many ways insurance rather than investment systems. A person who dies before retirement gets no money back (regardless of what he/she paid in). Someone who lives to a very old age continues to get payments regardless of the amount of money he/she has paid in. And someone disabled, even at a relatively young age (well before he/she can make significant payments into the system, or have significant private investments), still receives payments until the end of his/her life. Due to this, the typical retiree who does not become disabled early sees a lower rate of return than the risk free rate.

- Unlike a Ponzi scheme, government receipts (taxes) and payouts (entitlements) can be calculated quite accurately in the short term (five to ten years), and predicted (with a range of assumptions) for periods beyond that timeframe. A sudden collapse is therefore unlikely [citation needed].

The U.S. Social Security Administration provides the following analysis of this "Ponzi scheme" charge as applied to a pay-as-you-go system like Social Security:

- There is a superficial analogy between pyramid or Ponzi schemes and pay-as-you-go insurance programs in that in both money from later participants goes to pay the benefits of earlier participants. But that is where the similarity ends. A pay-as-you-go system can be visualized as a simple pipeline, with money from current contributors coming in the front end and money to current beneficiaries paid out the back end. So we could [imagine] that at any given time there might be, say, 40 million people receiving benefits at the back end of the pipeline; and as long as we had 40 million people paying taxes in the front end of the pipe, the program could be sustained forever. It does not require a doubling of participants every time a payment is made to a current beneficiary. (There does not have to be precisely the same number of workers and beneficiaries at a given time--there just needs to be a stable relationship between the two.) As long as the amount of money coming in the front end of the pipe maintains a rough balance with the money paid out, the system can continue forever. There is no unsustainable progression driving the mechanism of a pay-as-you-go pension system and so it is not a pyramid or Ponzi scheme.

- If the demographics of the population were stable, then a pay-as-you-go system would not have demographically-driven financing ups and downs and no thoughtful person would be tempted to compare it to a Ponzi arrangement. However, since population demographics tend to rise and fall, the balance in pay-as-you-go systems tends to rise and fall as well. During periods when more new participants are entering the system than are receiving benefits there tends to be a surplus in funding (as in the early years of Social Security). During periods when beneficiaries are growing faster than new entrants (as will happen when the baby boomers retire), there tends to be a deficit. This vulnerability to demographic ups and downs is one of the problems with pay-as-you-go financing. But this problem has nothing to do with Ponzi schemes, or any other fraudulent form of financing, it is simply the nature of pay-as-you-go systems.

(from "Ponzi Schemes" , which also describes the original Ponzi scheme in detail)

Trivia

- In one episode of the Nickelodeon cartoon Doug, the title character enters a sweepstakes to win a large amount of prizes, run by a company called "Ponzi Puzzles," an obvious reference to Ponzi schemes. Appropriately, Doug spends a considerable amount of time completing the puzzles and getting the money necessary to enter the sweepstakes, but ends up winning nothing.

- In the HBO show Six Feet Under, Season 1, Episode 2, the man who dies at the beginning is at the head of a Ponzi scheme.

See also

- Finance

- Holiday Magic

- HYIP

- Investment

- List of finance topics

- Pyramid scheme

- Lottery

- Get-rich-quick schemes

- Matrix scheme

- Reed Slatkin

References

- ^ a b Zuckoff, Mitchell. Ponzi's Scheme: The True Story of a Financial Legend. Random House: New York, 2005. (ISBN 1-4000-6039-7) Cite error: The named reference "zuckoff" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Visão, Apanhados pelos selos, 18 May 2006.

- ^ CanalSurWeb, Banqueros del pueblo, 12 May 2006

- ^ de:European Kings Club

- ^ The Star, Malaysia, 04 October 2006.

- ^ Today, Singapore, 24 January 2007.

- ^ Bank Negara, Malaysia, Malaysia, 05 September 2006.

External links

- US Securities and Exchange Commission background information

- Ponzi Schemes, by Bill E. Branscum, a financial crimes investigator]

The news story that got the Pakistani conman Double Shah in trouble; done by an investigative journalist Usman Ghazi for daily The Nation. http://www.nation.com.pk/daily/apr-2007/6/index6.php http://www.nation.com.pk/daily/apr-2007/14/index5.php

[[cs:aji{| class="wikitable" |- ! header 1 ! header 2 ! header 3 |- | row 1, cell 1 | row 1, cell 2 | row 1, cell 3 |- | row 2, cell 1 | row 2, cell 2 | row 2, cell 3 |}]]