Wasted Time R (talk | contribs) →Vietnam War and foreign policy: fix cite in last |

Wasted Time R (talk | contribs) →Vietnam War and foreign policy: continue to expand on PP |

||

| Line 89: | Line 89: | ||

The [[Conscription in the United States|U.S. military draft]] was scheduled to conclude at the end of June 1971, and the Senate faced a contentious debate about whether to extend it, as the [[Vietnam War]] continued.<ref name="nyt060571">{{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F40F1EFB3D5A1A7493C7A9178DD85F458785F9 | title=Senators Reject Limits on Draft; 2-Year Plan Gains | author=[[David E. Rosenbaum]] | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1971-06-05]] | accessdate=2007-12-29}}</ref> The [[Nixon administration]] had announced in February that it wanted a two-year extension to June 1973, after which the draft would end,<ref name="nyt020371">{{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F50C12FD3A55127B93C1A91789D85F458785F9 | title=Stennis Favors 4-Year Draft Extension, but Laird Asks 2 Years | author=[[David E. Rosenbaum]] | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1971-02-03]] | accessdate=2007-12-30}}</ref> while [[Senate Armed Services Committee]] chairman [[John Stennis]] thought this unrealistic and wanted a four-year extension.<ref name="nyt020371"/> By June 1971, some Democratic senators opposed to the war wanted to limit this to a one-year extension, while others wanted to end it immediately.<ref name="nyt060571"/> Gravel was one of the latter, saying, "It's a senseless war, and one way to do away with it is to do away with the draft."<ref name="nyt060571"/> A Senate vote on [[June 4]] indicated majority support for the two-year extension;'<ref name="nyt060571"/> on [[June 18]] Gravel announced his intention to counteract that by [[filibuster]]ing the renewal legislation.<ref>{{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=FA081EF73B5B1A7493C0AB178DD85F458785F9 | title=Filibustering the Draft | author=Mike Gravel | work=Letters to the Editor | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1971-06-22]] | accessdate=2007-12-29}}</ref> The first filibuster attempt failed on [[June 23]] when the Senate voted cloture for only the fifth time since 1927.<ref>{{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F70B1EFF3854127B93C6AB178DD85F458785F9 | title=Senate Votes Closure in Draft Debate, 65 to 27 | author=[[David E. Rosenbaum]] | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1971-06-24]] | accessdate=2007-12-29}}</ref> Protracted negotiations took place over House conference negotiations on the bill, revolving in large part around Senate Majority Leader [[Mike Mansfield]]'s eventually unsuccessful amendment to tie renewal to a troop withdrawal timetable from Vietnam; during this time the draft law expired and no one was conscripted.<ref name="nyt092271">{{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F50B10FD385C1A7493C0AB1782D85F458785F9 | title=Senate Approves Draft Bill, 55-30; President to Sign | author=[[David E. Rosenbaum]] | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1971-09-22]] | accessdate=2007-12-29}}</ref> On [[August 5]] the Nixon administration pleaded for a renewal before the Senate went on recess, but Gravel successfully blocked an attempt to limit debate by Stennis and no vote was held.<ref>{{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F60C1EF8395C1A7493C4A91783D85F458785F9 | title='72 Draft Lottery Assigns No. 1 to Those Born Dec. 4 | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1971-08-06]] | accessdate=2007-12-30}}</ref> Finally on [[September 21]], [[1971]], the Senate invoked cloture over Gravel's second filibuster attempt by one vote, and then passed the two-year draft extension.<ref name="nyt092271"/> Gravel's attempts to stop the draft had failed<ref name="nyt102671"/> (notwithstanding Gravel's latter claims that he had stopped the draft, taken at face value in some media reports, during his 2008 presidential campaign<ref>During Gravel's 2008 presidential campaign, he would claim that, "In 1971, Senator Mike Gravel (D-Alaska), by waging a lone five month filibuster, singlehandedly ended the draft in The United States thereby saving thousands of lives." See {{cite web | url=http://www.gravel2008.us/draft | title=Mike Gravel and the Draft | publisher=Mike Gravel for President 2008 | accessdate=2007-12-30}} A 2006 article in ''[[The Nation]]'' stated that "It was Gravel who in 1971, against the advice of Democratic leaders in the Senate, launched a one-man filibuster to end the peacetime military draft, forcing the administration to cut a deal that allowed the draft to expire in 1973." See {{cite news | url=http://www.commondreams.org/views06/0415-24.htm | title=Pentagon Papers Figure Bids for Presidency | author=John Nichols | publisher=[[The Nation]] | date=[[2006-04-15]] | accessdate=2007-12-20}} Neither of these assessments is correct. From the beginning of the draft review process in February 1971, the Nixon administration wanted a two-year extension to June 1973, followed by a shift to an all-volunteer force — see {{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F50C12FD3A55127B93C1A91789D85F458785F9 | title=Stennis Favors 4-Year Draft Extension, but Laird Asks 2 Years | author=[[David E. Rosenbaum]] | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1971-02-03]] | accessdate=2007-12-30}} — and this is what is what the September 1971 Senate vote gave them. Gravel's goal had been to block the renewal of the draft completely, thereby ending conscription past June 1971. See {{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=FA081EF73B5B1A7493C0AB178DD85F458785F9 | title=Filibustering the Draft | author=Mike Gravel | work=Letters to the Editor | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1971-06-22]] | accessdate=2007-12-29}}</ref>). |

The [[Conscription in the United States|U.S. military draft]] was scheduled to conclude at the end of June 1971, and the Senate faced a contentious debate about whether to extend it, as the [[Vietnam War]] continued.<ref name="nyt060571">{{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F40F1EFB3D5A1A7493C7A9178DD85F458785F9 | title=Senators Reject Limits on Draft; 2-Year Plan Gains | author=[[David E. Rosenbaum]] | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1971-06-05]] | accessdate=2007-12-29}}</ref> The [[Nixon administration]] had announced in February that it wanted a two-year extension to June 1973, after which the draft would end,<ref name="nyt020371">{{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F50C12FD3A55127B93C1A91789D85F458785F9 | title=Stennis Favors 4-Year Draft Extension, but Laird Asks 2 Years | author=[[David E. Rosenbaum]] | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1971-02-03]] | accessdate=2007-12-30}}</ref> while [[Senate Armed Services Committee]] chairman [[John Stennis]] thought this unrealistic and wanted a four-year extension.<ref name="nyt020371"/> By June 1971, some Democratic senators opposed to the war wanted to limit this to a one-year extension, while others wanted to end it immediately.<ref name="nyt060571"/> Gravel was one of the latter, saying, "It's a senseless war, and one way to do away with it is to do away with the draft."<ref name="nyt060571"/> A Senate vote on [[June 4]] indicated majority support for the two-year extension;'<ref name="nyt060571"/> on [[June 18]] Gravel announced his intention to counteract that by [[filibuster]]ing the renewal legislation.<ref>{{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=FA081EF73B5B1A7493C0AB178DD85F458785F9 | title=Filibustering the Draft | author=Mike Gravel | work=Letters to the Editor | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1971-06-22]] | accessdate=2007-12-29}}</ref> The first filibuster attempt failed on [[June 23]] when the Senate voted cloture for only the fifth time since 1927.<ref>{{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F70B1EFF3854127B93C6AB178DD85F458785F9 | title=Senate Votes Closure in Draft Debate, 65 to 27 | author=[[David E. Rosenbaum]] | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1971-06-24]] | accessdate=2007-12-29}}</ref> Protracted negotiations took place over House conference negotiations on the bill, revolving in large part around Senate Majority Leader [[Mike Mansfield]]'s eventually unsuccessful amendment to tie renewal to a troop withdrawal timetable from Vietnam; during this time the draft law expired and no one was conscripted.<ref name="nyt092271">{{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F50B10FD385C1A7493C0AB1782D85F458785F9 | title=Senate Approves Draft Bill, 55-30; President to Sign | author=[[David E. Rosenbaum]] | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1971-09-22]] | accessdate=2007-12-29}}</ref> On [[August 5]] the Nixon administration pleaded for a renewal before the Senate went on recess, but Gravel successfully blocked an attempt to limit debate by Stennis and no vote was held.<ref>{{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F60C1EF8395C1A7493C4A91783D85F458785F9 | title='72 Draft Lottery Assigns No. 1 to Those Born Dec. 4 | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1971-08-06]] | accessdate=2007-12-30}}</ref> Finally on [[September 21]], [[1971]], the Senate invoked cloture over Gravel's second filibuster attempt by one vote, and then passed the two-year draft extension.<ref name="nyt092271"/> Gravel's attempts to stop the draft had failed<ref name="nyt102671"/> (notwithstanding Gravel's latter claims that he had stopped the draft, taken at face value in some media reports, during his 2008 presidential campaign<ref>During Gravel's 2008 presidential campaign, he would claim that, "In 1971, Senator Mike Gravel (D-Alaska), by waging a lone five month filibuster, singlehandedly ended the draft in The United States thereby saving thousands of lives." See {{cite web | url=http://www.gravel2008.us/draft | title=Mike Gravel and the Draft | publisher=Mike Gravel for President 2008 | accessdate=2007-12-30}} A 2006 article in ''[[The Nation]]'' stated that "It was Gravel who in 1971, against the advice of Democratic leaders in the Senate, launched a one-man filibuster to end the peacetime military draft, forcing the administration to cut a deal that allowed the draft to expire in 1973." See {{cite news | url=http://www.commondreams.org/views06/0415-24.htm | title=Pentagon Papers Figure Bids for Presidency | author=John Nichols | publisher=[[The Nation]] | date=[[2006-04-15]] | accessdate=2007-12-20}} Neither of these assessments is correct. From the beginning of the draft review process in February 1971, the Nixon administration wanted a two-year extension to June 1973, followed by a shift to an all-volunteer force — see {{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F50C12FD3A55127B93C1A91789D85F458785F9 | title=Stennis Favors 4-Year Draft Extension, but Laird Asks 2 Years | author=[[David E. Rosenbaum]] | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1971-02-03]] | accessdate=2007-12-30}} — and this is what is what the September 1971 Senate vote gave them. Gravel's goal had been to block the renewal of the draft completely, thereby ending conscription past June 1971. See {{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=FA081EF73B5B1A7493C0AB178DD85F458785F9 | title=Filibustering the Draft | author=Mike Gravel | work=Letters to the Editor | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1971-06-22]] | accessdate=2007-12-29}}</ref>). |

||

Meanwhile, on [[June 13]], [[1971]], ''[[The New York Times]]'' began printing large portions of the [[Pentagon Papers]].<ref name="nyt061371a">{{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F10B1FFD3D5813748DDDAA0994DE405B818BF1D3 | title=Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces 3 Decades of Growing U. S. Involvement | author=[[Neil Sheehan]] | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1971-06-13]] | accessdate=2007-12-30}}</ref> This was a large collection of secret government documents pertaining to the [[Vietnam War]], which had been leaked to ''The Times'' by former [[United States Department of Defense|Defense Department]] analyst [[Daniel Ellsberg]].<ref name="usc-timeline">{{cite web | url=http://www.topsecretplay.org/index.php/content/timeline | title=Timeline | work=Top Secret: The Battle for the Pentagon Papers | publisher=[[Annenberg Center for Communication]] at [[University of Southern California]] | accessdate=2007-12-30}}</ref> The [[U.S. Justice Department]] immediately tried to halt publication, on the grounds that the information revealed within the papers harmed the national interest.<ref name="usc-timeline"/> Within the new two weeks, a federal court injunction halted publication in ''The Times''; ''[[The Washington Post]]'' and several other newspapers began publishing parts of the documents, with some of them also being halted by injunctions; and the whole matter went to the [[U.S. Supreme Court]] for arguments.<ref name="usc-timeline"/> |

Meanwhile, on [[June 13]], [[1971]], ''[[The New York Times]]'' began printing large portions of the [[Pentagon Papers]].<ref name="nyt061371a">{{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F10B1FFD3D5813748DDDAA0994DE405B818BF1D3 | title=Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces 3 Decades of Growing U. S. Involvement | author=[[Neil Sheehan]] | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1971-06-13]] | accessdate=2007-12-30}}</ref> This was a large collection of secret government documents pertaining to the [[Vietnam War]], which had been leaked to ''The Times'' by former [[United States Department of Defense|Defense Department]] analyst [[Daniel Ellsberg]].<ref name="usc-timeline">{{cite web | url=http://www.topsecretplay.org/index.php/content/timeline | title=Timeline | work=Top Secret: The Battle for the Pentagon Papers | publisher=[[Annenberg Center for Communication]] at [[University of Southern California]] | accessdate=2007-12-30}}</ref> The [[U.S. Justice Department]] immediately tried to halt publication, on the grounds that the information revealed within the papers harmed the national interest.<ref name="usc-timeline"/> Within the new two weeks, a federal court injunction halted publication in ''The Times''; ''[[The Washington Post]]'' and several other newspapers began publishing parts of the documents, with some of them also being halted by injunctions; and the whole matter went to the [[U.S. Supreme Court]] for arguments.<ref name="usc-timeline"/> Looking for an alternate publication mechanism, Ellsburg arranged for the papers to be given to Gravel.<ref name="beacon-hist">{{cite web | url=http://www.beacon.org/client/pentagonpapers.cfm | title=Beacon Press & the Pentagon Papers: History | publisher=[[Beacon Press]] | date=[[2006-10-22]] | accessdate=2007-12-30}}</ref> On the night of [[June 29]], [[1971]], Gravel attempted to read the papers on the floor of the Senate as part of his filibuster against the draft, but was thwarted when no quorum could be formed.<ref name="nyt063071">{{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F60617FC395C1A7493C2AA178DD85F458785F9 | title=Gravel Speaks 3 Hours; Senator Reading Study to Press | author=[[David E. Rosenbaum]] | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1971-06-30]] | accessdate=2007-12-30}}</ref> Gravel instead convened a session of the Buildings and Grounds subcommittee that he chaired, and began reading from the papers with the press in attendance,<ref name="nyt063071"/> omitting supporting documents that he felt might compromise national security;<ref name="nyt070171">{{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F70B14FC3A5B1A7493C3A9178CD85F458785F9 | title=Action by Gravel Vexes Many Senators | author=John W. Finney | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1971-07-01]] | accessdate=2007-12-30}}</ref> he read until 1 a.m., until with tears and sobs he said that he could no longer physically continue.<ref name="nyt070171"/> Gravel inserted 4,100 pages of the Papers into the [[Congressional Record]] of his subcommittee. The following day, the Supreme Court's ''[[New York Times Co. v. United States]]'' decision ruled in favor of the newspapers<ref name="usc-timeline"/> and publication in ''The Times'' and others resumed. |

||

These pages were later issued by the [[Beacon Press]], the publishing arm of the [[Unitarian Universalist Association]], as the "Senator Gravel Edition" — the most complete edition of the Pentagon Papers to be published. The "Gravel Edition" was edited and annotated by [[Noam Chomsky]] and [[Howard Zinn]], and included an additional volume of analytical articles on the origins and progress of the war, also edited by Chomsky and Zinn. |

|||

These events changed Gravel in the months following from an obscure freshman senator in a far corner of the country to a nationally-visible political figure.<ref name="nyt102671">{{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F30A12F73D5E127A93C4AB178BD95F458785F9 | title=Fame Travels With Senator Gravel, the Man Who Read Pentagon Papers Into the Record | author=[[David E. Rosenbaum]] | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1971-10-26]] | accessdate=2007-12-24}}</ref> He became a sought-after speaking on the college circuit as well as at political fundraisers,<ref name="nyt102671"/> opportunities he welcomed as lectures were "the one honest way a Senator has to supplement his income."<ref name="nyt102671"/> The Democratic candidates for the [[United States presidential election, 1972|1972 presidential election]] sought out his endorsement.<ref name="nyt102671"/> In January 1972 Gravel did endorse [[Maine]] Senator [[Ed Muskie]],<ref>{{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F00D16F83C591A7493C7A8178AD85F468785F9 | title=More Muskie Support | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1972-01-15]] | accessdate=2007-12-24}}</ref> hoping his endorsement would help Muskie with the party's left wing and in the ethnic French-Canadian areas in [[New Hampshire primary|first primary state New Hampshire]]<ref name="nyt102671"/> (which Muskie would indeed win, but not convincingly and his campaign faltered soon thereafter). |

These events changed Gravel in the months following from an obscure freshman senator in a far corner of the country to a nationally-visible political figure.<ref name="nyt102671">{{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F30A12F73D5E127A93C4AB178BD95F458785F9 | title=Fame Travels With Senator Gravel, the Man Who Read Pentagon Papers Into the Record | author=[[David E. Rosenbaum]] | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1971-10-26]] | accessdate=2007-12-24}}</ref> He became a sought-after speaking on the college circuit as well as at political fundraisers,<ref name="nyt102671"/> opportunities he welcomed as lectures were "the one honest way a Senator has to supplement his income."<ref name="nyt102671"/> The Democratic candidates for the [[United States presidential election, 1972|1972 presidential election]] sought out his endorsement.<ref name="nyt102671"/> In January 1972 Gravel did endorse [[Maine]] Senator [[Ed Muskie]],<ref>{{cite news | url=http://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F00D16F83C591A7493C7A8178AD85F468785F9 | title=More Muskie Support | publisher=[[The New York Times]] | date=[[1972-01-15]] | accessdate=2007-12-24}}</ref> hoping his endorsement would help Muskie with the party's left wing and in the ethnic French-Canadian areas in [[New Hampshire primary|first primary state New Hampshire]]<ref name="nyt102671"/> (which Muskie would indeed win, but not convincingly and his campaign faltered soon thereafter). |

||

Revision as of 14:49, 30 December 2007

Mike Gravel | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Alaska | |

| In office January 3, 1969 – January 3, 1981 | |

| Preceded by | Ernest Gruening |

| Succeeded by | Frank Murkowski |

| 3rd Speaker of the Alaska House of Representatives | |

| In office 1965–1966 | |

| Preceded by | Bruce Biers Kendall |

| Succeeded by | William K. Boardman |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May 13, 1930 Springfield, Massachusetts |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Rita Martin (divorced) Whitney Stewart Gravel |

| Profession | Real estate development, author |

| Signature | File:Gravelsign.JPG |

Maurice Robert "Mike" Gravel (Template:PronEng) (born May 13, 1930) is a former Democratic United States Senator from Alaska who served two terms from 1969 to 1981, and is a candidate for the Demcratic Party nomination in the 2008 presidential election.

Born and raised in Springfield, Massachusetts to French-Canadian immigrant parents, Gravel served in the United States Army in West Germany and graduated from Columbia University. He moved to Alaska in the late 1950s, becoming a real estate developer and entering politics. He served in the Alaska House of Representatives from 1963 to 1966 and became its Speaker of the House. Gravel was elected to the United States Senate in 1968.

As Senator, Gravel became nationally known for his unsuccessful attempts to end the draft during the Vietnam War and for having put the Pentagon Papers into the public record in 1971. He played a role in stopping nuclear testing in Alaska and in getting approval for the Trans-Alaska pipeline. He conducted an unusual campaign for the Democratic nomination for Vice President of the United States in 1972. He was re-elected to the Senate in 1974, but gradually alienated most of his Alaskan constituencies and his bid for a third term was defeated in a Democratic primary election in 1980.

Gravel returned to business ventures and went through difficult times, suffering corporate and personal bankruptcies. He became a passionate advocate of direct democracy and the National Initiative, and in 2006 began a run for President of the United States in part to promote those ideas. His campaign gained an Internet following and national attention from forceful and idiosyncratic debate appearances during 2007, but has consistently shown very little support in national polls.

Early life, military service, education

Gravel was born in Springfield, Massachusetts to French-Canadian immigrant parents, Marie Bourassa and Alphonse Gravel,[2] a painting contractor.[3] There, he was raised in a working class neighborhood,[4] while he learned at home to speak French fluently.[5] He was educated in parochial schools as a Roman Catholic, attending Assumption College Preparatory School. He has a sister, Marguerite, who became a nun,[3] but Gravel himself struggled with Catholicism.[1]

Gravel studied for one year at American International College in Springfield,[6] then enlisted in the United States Army in 1951 and served in West Germany as a Special Adjutant in the Communication and Intelligent Services and as a Special Agent in the Counter Intelligence Corps until 1954,[7][4] eventually becoming a First Lieutenant.[8] A dyslexic, who talks about his learning disability openly,[9] he attended Columbia University's School of General Studies in New York City, where he studied economics and received a B.S. in 1956.[10] He had come to New York "flat broke",[8] and supported himself by working as a bar boy in a hotel,[8] driving a taxicab,[11] and working in the investment bond department at Bankers Trust.[8] During this time he left the Catholic faith.[1]

Move to Alaska

Gravel "decided to become a pioneer in a faraway place,"[8] and moved to Alaska in 1956, without funds or a job, looking for a place where he could be a viable candidate for public office;[11] Alaska's voting age of 19, less than most other states' 21, played a role,[12] as did its cooler climate.[11] He found work in several areas, including real estate sales, brakeman for the Alaska Railroad, and as a very successful property developer on the Kenai Peninsula.[13][8] He joined the Anchorage Unitarian Universalism fellowship, and would continue a sporadic relationship with the movement throughout his life.[1]

Gravel married Rita Jeannette Martin, who had been Anchorage's "Miss Fur Rendezvous" of 1958,[14] on April 29, 1959.[14] They had two children, Martin Anthony Gravel and Lynne Denise Gravel,[14] born circa 1960 and 1962 respectively.[12] Meanwhile, he ran unsuccessfully for the territorial legislature in 1958.[11] He went on a national speaking tour concerning tax reform in 1959, sponsored by the Jaycees.[10] He ran unsuccessfully for the Anchorage City Council in 1960.[11]

State legislator

With some newfound wealthy backers,[12] Gravel ran for the Alaska House of Representatives representing Anchorage in 1962 and won.[11]

Gravel served in the Alaska House of Representatives from 1963 to 1966, winning re-election in 1964. During 1965 and 1966, he served as the Speaker of the House, surprising observers by winning that post.[12] As Speaker he antagonized fellow lawmakers by imposing his will on the legislature's commitees.[12]

He did not run for re-election in 1966, instead choosing to run for Alaska's seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, losing to four-term incumbent Democrat Ralph Rivers[11] by 1,300 votes[12] and splitting the Democratic party in the process.[12]

Following his defeat, Gravel returned to the real-estate business in Anchorage.[12]

U.S. Senator

Election to Senate in 1968

In 1968 he ran against the 81-year-old incumbent Democratic Senator Ernest Gruening, a popular former governor of the Alaska Territory who was considered one of the fathers of Alaska's statehood,[11] for his party's nomination to the U.S. Senate. Gravel's campaign was primarily based on his youth.[12] He hired Joseph Napolitan, the first self-described political consultant, in late 1966,[12] and they spent over a year and a half planning a short primary election campaign that featured a half-hour, well-produced[11] biographical film of Gravel that was shown frequently on both television and on home projectors in many Eskimo villages.[12] The heavy showings quickly reversed a large Gruening lead in polls into a Gravel lead.[12] Gravel also benefitted by being deliberately ambiguous about his Vietnam policy. Gruening had been one of only two Senators to vote against the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution and, according to Gravel, "...all I had to do was stand up and not deal with the subject, and people would assume that I was to the right of Ernest Gruening, when in point of fact I was to the left of him."[11]

Gravel unexpectedly beat Gruening in a tight result[15] in the primary and went on to win the general election, gaining 45% of the vote against 37% for Republican Elmer E. Rasmuson and 18% for Gruening, who ran a write-in campaign as an Independent.[16]

Senate assignments and style

Gravel served on the Environment and Public Works Committee throughout his Senate career. He also served on the Finance and Interior Committees and he chaired the Energy, Water Resources, and Environmental Pollution subcommittees.[17]

By his own admission Gravel was too new and "too abrasive" to be effective in the Senate by the usual means of seniority-based committee assignments or negotiating backroom deals with other senators,[12][5] and was sometimes seen as arrogant by the more senior members.[12] Gravel instead relied upon attention-getting gestures to achieve what he wanted, hoping national exposure would force other senators to listen to him.[5] As part of this he voted with Southern Democrats to keep the Senate filibuster rule in place,[12] and accordingly supported Russell Long and Robert Byrd and opposed Ted Kennedy in Senate leadership battles.[12]

Nuclear issues

In the late 1960s and early 1970s the Pentagon was in the process of performing calibration tests for a nuclear warhead that, upon investigation, was revealed to be obsolete. The Cannikin tests involved the detonation of nuclear bombs under the seabed of the North Pacific at Amchitka Island, Alaska. Gravel opposed the tests in Congress and organized worldwide environmental opposition to their continuation. The program was halted after the second test.

Nuclear power was considered an environmentally clean alternative for the commercial generation of electricity and was part of a popular national policy for the peaceful use of atomic energy in the 1950s and 1960s. Gravel publicly opposed this policy in 1970. He used his office to organize citizen opposition to the policy and to persuade Ralph Nader's organization to join the opposition.

Vietnam War and foreign policy

Six months before United States Secretary of State Henry Kissinger's secret mission to the People's Republic of China in July 1971, Gravel introduced legislation to recognize and normalize relations with the PRC;[citation needed] he reiterated his position, with four other senators in agreement, during Senate hearings in June 1971.[18]

The U.S. military draft was scheduled to conclude at the end of June 1971, and the Senate faced a contentious debate about whether to extend it, as the Vietnam War continued.[19] The Nixon administration had announced in February that it wanted a two-year extension to June 1973, after which the draft would end,[20] while Senate Armed Services Committee chairman John Stennis thought this unrealistic and wanted a four-year extension.[20] By June 1971, some Democratic senators opposed to the war wanted to limit this to a one-year extension, while others wanted to end it immediately.[19] Gravel was one of the latter, saying, "It's a senseless war, and one way to do away with it is to do away with the draft."[19] A Senate vote on June 4 indicated majority support for the two-year extension;'[19] on June 18 Gravel announced his intention to counteract that by filibustering the renewal legislation.[21] The first filibuster attempt failed on June 23 when the Senate voted cloture for only the fifth time since 1927.[22] Protracted negotiations took place over House conference negotiations on the bill, revolving in large part around Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield's eventually unsuccessful amendment to tie renewal to a troop withdrawal timetable from Vietnam; during this time the draft law expired and no one was conscripted.[23] On August 5 the Nixon administration pleaded for a renewal before the Senate went on recess, but Gravel successfully blocked an attempt to limit debate by Stennis and no vote was held.[24] Finally on September 21, 1971, the Senate invoked cloture over Gravel's second filibuster attempt by one vote, and then passed the two-year draft extension.[23] Gravel's attempts to stop the draft had failed[5] (notwithstanding Gravel's latter claims that he had stopped the draft, taken at face value in some media reports, during his 2008 presidential campaign[25]).

Meanwhile, on June 13, 1971, The New York Times began printing large portions of the Pentagon Papers.[26] This was a large collection of secret government documents pertaining to the Vietnam War, which had been leaked to The Times by former Defense Department analyst Daniel Ellsberg.[27] The U.S. Justice Department immediately tried to halt publication, on the grounds that the information revealed within the papers harmed the national interest.[27] Within the new two weeks, a federal court injunction halted publication in The Times; The Washington Post and several other newspapers began publishing parts of the documents, with some of them also being halted by injunctions; and the whole matter went to the U.S. Supreme Court for arguments.[27] Looking for an alternate publication mechanism, Ellsburg arranged for the papers to be given to Gravel.[28] On the night of June 29, 1971, Gravel attempted to read the papers on the floor of the Senate as part of his filibuster against the draft, but was thwarted when no quorum could be formed.[29] Gravel instead convened a session of the Buildings and Grounds subcommittee that he chaired, and began reading from the papers with the press in attendance,[29] omitting supporting documents that he felt might compromise national security;[30] he read until 1 a.m., until with tears and sobs he said that he could no longer physically continue.[30] Gravel inserted 4,100 pages of the Papers into the Congressional Record of his subcommittee. The following day, the Supreme Court's New York Times Co. v. United States decision ruled in favor of the newspapers[27] and publication in The Times and others resumed.

These pages were later issued by the Beacon Press, the publishing arm of the Unitarian Universalist Association, as the "Senator Gravel Edition" — the most complete edition of the Pentagon Papers to be published. The "Gravel Edition" was edited and annotated by Noam Chomsky and Howard Zinn, and included an additional volume of analytical articles on the origins and progress of the war, also edited by Chomsky and Zinn.

These events changed Gravel in the months following from an obscure freshman senator in a far corner of the country to a nationally-visible political figure.[5] He became a sought-after speaking on the college circuit as well as at political fundraisers,[5] opportunities he welcomed as lectures were "the one honest way a Senator has to supplement his income."[5] The Democratic candidates for the 1972 presidential election sought out his endorsement.[5] In January 1972 Gravel did endorse Maine Senator Ed Muskie,[31] hoping his endorsement would help Muskie with the party's left wing and in the ethnic French-Canadian areas in first primary state New Hampshire[5] (which Muskie would indeed win, but not convincingly and his campaign faltered soon thereafter).

Run for Vice President in 1972

Gravel actively campaigned for the office of Vice President of the United States during the 1972 presidential election, announcing on June 2, 1972, over a month before the 1972 Democratic National Convention began, that he was interested in running for the nomination should the choice be opened up to convention delegates.[32] Towards this end he began soliciting delegates for their support in advance of the convention.[33] He was not alone in this effort, as former Governor of Massachusetts Endicott Peabody had been running a quixotic campaign for the same post[34] since the prior year. Likely presidential nominee George McGovern was in fact considering the unusual move of naming three or four acceptable vice-presidential candidates and letting the delegates choose.[34]

At the convention's final day on July 14, 1972, presidential nominee McGovern selected and announced Senator Thomas Eagleton of Missouri as his vice-presidential choice.[35] Eagleton was unknown to many delegates and the choice seemed to smack of traditional ticket balancing considerations.[35][36] Thus, there were delegates willing to look elsewhere. Gravel was nominated by Bettye Fahrenkamp, the national committeewoman of Alaska; he then addressed the convention and won 226 delegate votes, coming in third behind Eagleton and Frances "Sissy" Farenthold of Texas, in chaotic balloting[37][36] that included several other candidates as well.

For his efforts, Gravel attracted some attention: famed writer Norman Mailer would say he "provided considerable excitement" and was "good-looking enough to have played leads in B-films".[38] while Rolling Stone correspondent Hunter S. Thompson said Gravel "probably said a few things that might have been worth hearing, under different circumstances ..."[39] Yet, the whole process had been doubly disastrous for the Democrats: the time consumed with the nominating and seconding and other speeches of all the vice-presidential candidates had lost the focus of the delegates on the floor[39] and famously pushed back McGovern's speech until 3:30 a.m.,[39] while the haste and cynicism with which Eagleton had been selected was rewarded with his personal relevations and withdrawal from the ticket soon after the convention concluded.

Re-election to Senate in 1974

Several years earlier, Alaskan politicians had speculated that Gravel would have a hard time getting both renominated and elected when his first term expired,[5] given that he was originally elected without a base party organization and tended to focus on national rather than local issues.[5]

Nonetheless, in 1974 Gravel was re-elected to the Senate,[40] winning 58% of the vote against 42% for Republican State Senator C. R. Lewis, who was a national officer of the John Birch Society.[41]

Alaskan issues

By 1971, Gravel was urging construction of the much-argued Trans-Alaska pipeline, addressing environment concerns by saying that the pipeline's builders and operators should have "total and absolute" responsibility for any consequent environmental damage.[42] In 1973, Gravel introduced an amendment to empower the Congress to make the policy decision about the construction of the pipeline. The amendment passed the Senate by a single vote. The pipeline has been responsible for 20% of the U.S. oil supply.

In opposition to the Alaskan fishing industry, Gravel advocated American participation in the formation of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). For two years he opposed legislation that permitted the U.S. to unilaterally take control of the 200-mile waters bordering its land mass. The legislation was passed, and the United States has signed but never ratified the UNCLOS.

He helped secure a private grant to facilitate the first Inuit Circumpolar Conference in 1977, attended by Inuit representatives from Alaska, Canada, and Greenland. These conferences now also include representatives from Russia.

In the early 1970s Gravel supported a demonstration project that established links between Alaskan villages and the National Institute of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, for medical diagnostic communications.

A key, emotional issue in the state at the time was "locking up Alaska", making reference to allocation of its vast, mostly uninhabited land.[43] In 1978 Gravel blocked passage, via procedural delays,[43] a complex, compromise lands bill that would have put some of Alaska's vast federal land holdings under state control while preserving other portions for federal parks and refuges;[11] the action would earn Gravel the enmity of fellow Alaska Senator Ted Stevens.[11] In 1980 a new lands bill came up for consideration, that was less favorable to Alaskan interests; it set aside 104 of Alaska's 375 million acres for national parks, conservation areas, and other restricted federal uses.[43] Gravel, in representation of those interests, tried to stop the bill, including staging a filibuster.[11] The Senate, however, voted cloture and then passed the bill.[44] Frustrated, Gravel said the Senate was "a little bit like a tank of barracudas."[43]

Gravel authored and secured the passage into law of the General Stock Ownership Corporation (GSOC), Subchapter U of the Tax Code, as a prerequisite to a failed 1980 Alaskan ballot initiative that would have paid dividends to Alaskan citizens for Pipeline-related revenue.

Loss of Senate seat in 1980

In 1980 Gravel was challenged for the Democratic Party's nomination by State Representative Clark Gruening, the grandson of the man Gravel had defeated in a primary twelve years earlier. Gruening won the bitterly-fought[44] primary, with about 55 percent of the vote to Gravel's 44 percent.[44] As an incumbent candidate in 1968, Gravel had never established a firm party base;[15] a group of Democrats, including future governor Steve Cowper,[45] led the campaign against Gravel, with Gravel's actions in respect to the 1978 and 1980 Alaskan lands bills a major issue,[11][44] especially given that the latter's denouement happened but a week before the primary.[43] The sources of Gravel's campaign funds, some of which came from political action committees outside the state, also became an issue in the contest.[44] Another factor may have been Alaska's primary system, which allows unlimited cross-over voting across parties and from its large unaffiliated electorate;[45] Republicans believed Gruening would be an easier candidate to defeat in the general election.[44] In any case, Gravel would later concede that by the time of his defeat, he had alienated "almost every constituency in Alaska."[11] Gruening did go on to lose in the general election to Republican Frank Murkowski. To date, Gravel is the last Democrat to represent Alaska in Congress.

Career after leaving the Senate

Gravel took the 1980 defeat hard, recalling years later: "I had lost my career. I lost my marriage. I was in the doldrums for ten years after my defeat."[46] Sometime in the early 1980s, he and his first wife Rita were divorced; she would later be the recipient of all of his Senate pension income.[11]

During the 1980s, Gravel was a real estate developer in Anchorage and Kenai, Alaska,[47] a consultant, and a stockbroker.[11] One of his real estate ventures, a condominium business, was forced to declare bankruptcy and a lawsuit ensued.[11]

Beginning in 1989 he reentered the world of politics.[11] He became founder and head of The Democracy Foundation, which promotes direct democracy.[48]

Gravel led an effort to get a United States Constitutional amendment to allow voter-initiated federal legislation similar to state ballot initiatives. He argued that Americans are able to legislate responsibly, and that the Act and Amendment in the National Initiative would allow American citizens to become "law makers".

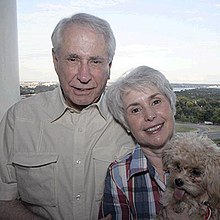

Gravel married his second wife, Whitney Stewart Gravel, circa 1984;[49] they live in Arlington County, Virginia. They have the two grown children from his first marriage, Martin Gravel and Lynne Gravel Mosier, and four grandchildren.[50] In the 2000s, Gravel suffered from serious health issues, requiring three surgeries in 2003 for back pain and neuropathy;[11] in 2004 he declared personal bankruptcy.[11] After that, he began taking a salary from the non-profit organizations he was working for. Much of that income was lent to his presidential campaign; in 2007, he declared that he has "zero net worth."[11]

Barnes Review controversy

In June 2003 Gravel gave a speech on direct democracy at a conference hosted by the American Free Press. The event was cosponsored by the Barnes Review, a journal that endorses Holocaust denial.[51] Gravel has said repeatedly that he does not share such a view, stating "You better believe I know that six million Jews were killed. I've been to the Holocaust Museum. I've seen the footage of General Eisenhower touring one of the camps. They're [referring to the Barnes Review and publisher Willis Carto] nutty as loons if they don't think it happened". The newspaper had intended to interview Gravel about the National Initiative. Gravel later recounted the background to the event:

"He [Carto] liked the idea of the National Initiative. I figured it was an opportunity to discuss it. Whether it is the far right, far left, whatever, I'll make my pitch to them. They gave me a free subscription to American Free Press. They still send it to me today. I flip through it sometimes. It has some extreme views, and a lot of the ads in it are even more extreme and make me want to upchuck. Anyways, sometime later, Carto contacted me to speak at that Barnes Review Conference. I had never heard of the Barnes Review, didn't know anything about it or what they stood for. I was just coming to give a presentation about the National Initiative. I was there maybe 30 minutes. I could tell from the people in the room (mainly some very old men) that they were pretty extreme. I gave my speech, answered some questions and left. I never saw the agenda for the day or listened to any of the other presentations."[52]

Political positions

Gravel has stated that he is an advocate for "a national, universal single-payer not-for-profit health care system" in the United States which would utilize vouchers and enable citizens to choose their own doctor.[53] He has proposed to index veteran health care entitlements to take full account of increases in the costs of care and medicine.[53] He supports a drug policy that legalizes and regulates all drugs, treating drug abuse as a medical issue, rather than a criminal matter.[54] Gravel favors a guest worker program,[53] supports the FairTax proposal that calls for eliminating the IRS and the income tax and replacing it with a progressive national sales tax of 23 percent on newly manufactured items and services, retaining progressivity via all taxes on spending up to the poverty level being refunded to every household.[53] Gravel has advocated that carbon energy should be taxed to provide the funding for a global effort to bring together the world's scientific and engineering communities to develop energy alternatives to significantly reduce the world’s energy dependence on carbon.[53] Gravel in principle does not object to the use of embryonic stem cells for medical research purposes. He is avowedly pro-choice on the issue of abortion and women's reproductive rights. He supports constitutional amendments towards direct democracy.

Some of his political leanings and convictions may also be gleaned from his 1972-published manifesto, Citizen Power.

2008 presidential campaign

Template:Future election candidate

At the start of 2006, Gravel decided the best way he could promote direct democracy and the National Initiative was to run for president.[11] On April 17, 2006,[55] Gravel became the first candidate for the Democratic nomination for President of the United States in the 2008 election, announcing his run in a speech to the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. Short on campaign cash, he took public transportation to get to his announcement.[56] Other principal issues for Gravel were a progressive retail sales tax, which he saw as removing tax loopholes for the rich, relieving tax burdens on the middle class and the poor, and allowing abolition of the Internal Revenue Service; withdrawal from the war in Iraq within 120 days; a single payer national health care system; and term limits.

Gravel campaigned almost full time in New Hampshire, the first primary state, following his announcement. Prior to February 2007, opinion polls of contenders for the Democratic nomination all showed Gravel with a 1% or less support level. He addressed the Democratic National Committee's Winter Convention in early February 2007 and was one of the participants in the Democratic Presidential Candidates forum in Carson City, Nevada later the same month. At the end of March 2007, Gravel's campaign had less than $500 in cash on hand against debts of nearly $90,000.[57]

On April 26, 2007, Gravel took part in the first Democratic presidential debate at South Carolina State University in Orangeburg, South Carolina. During the debate he suggested a Democratic bill requiring the president to withdraw from Iraq on pain of criminal penalties. He also advocated positions such as opposing preemptive nuclear war. He stated that the Iraq War had the effect of creating more terrorists and that the "war was lost the day that George Bush invaded Iraq on a fraudulent basis." Regarding his fellow candidates, he said, "I got to tell you, after standing up with them, some of these people frighten me — they frighten me."[58] Media stories said that Gravel was responsible for much of whatever "heat" and "flashpoints" had taken place.[59][60][58] Gravel gained considerable publicity by shaking up the normally staid multiple-candidate format; The New York Times' media critic said that what Gravel had done was "steal a debate with outrageous, curmudgeonly statements."[61] The powers of the Internet was a benefit: a YouTube video of his responses in the debate achieved in excess of 225,892 views, and honors such as #17 most views (for week), #7 top rated (for week), #23 top favorited (for week), #25 most discussed (for week), #4 most linked (for week), #1 most viewed - news and politics (for week), and #1 top rated - news and politics (for week);[62] his name became the 15th most searched-for in the blogosphere;[63] and his website garnered more traffic than those of frontrunners Hillary Rodham Clinton, Barack Obama, or John Edwards.[11] Gravel appeared on the popular Colbert Report on May 3,[11] and his campaign and career was profiled in national publications such as Salon.[11] Some thirty-five years after he first achieved the national spotlight, he had found it again.

However, it did not improve his performance in the polls; a May 2007 CNN poll showed him with less than 0.5 percent support among Democrats. [64] Gravel participated in the next several debates, in one case after CNN reversed a prior decision to exclude him.[65] Gravel, as with some of the other second-tier candidates, did not get as much time as the leaders; during the June 2, 2007 New Hampshire debate, which lasted two hours, he was asked 10 questions and allowed to speak for five minutes and 37 seconds.[66] During the July 23, 2007 CNN-YouTube presidential debate, Gravel responded to audience applause when he had complained of a lack of airtime and said: "Thank you. Has it been fair thus far?" [67] In the ABC News Des Moines, Iowa debate of August 19, 2007, moderator George Stephanopoulos noted in his that Gravel polled a statistical zero percent support in the state, meaning less than 0.5% support, and then directed roughly five percent of his questions to Gravel;[68] in a poll asking who did the best in the debate, Gravel placed seventh among the eight candidates.[69] National opinion polls of contenders for the Democratic nomination continued to show Gravel with one percent or zero percent numbers. By the end of the third-quarter 2007, Gravel had about $17,500 in cash on hand, and had collected a total of about $380,000 so far during the 2008 election cycle.[70]

Beginning with the October 30, 2007 Philadelphia event, Gravel was excluded from most of the remaining Democratic debates, with the debate sponsors or the Democratic National Committee saying Gravel's campaign had not met fundraising, polling, or local campaign organizational thresholds.[71][72][73] For the Philadelphia exclusion, Gravel blamed corporate censorship on the part of sponsor owner and alleged military-industrial complex member General Electric for his exclusion[74][75] and mounted a counter-gathering and debate against a video screen a short distance away,[76] but he had now lost his most ready access to visibility. In reaction, supporters have organized and held "mass donation days" to help the campaign gain momentum and necessary funds. One such day was December 5, 2007, the anniversary of the Repeal of Prohibition; this day yielded upwards of $10,000 from donations. Supporters are now organizing another effort to boost Gravel's fundraising for January 1, 2008, using the phrase "Gravel Resolution for Revolution" as a catchphrase and way to publicize.

References

- ^ a b c d Mike Gravel's Unitarian Universalism, by Doug Muder, UUWorld, December 10 2007. Accessed December 19 2007.

- ^ Battle, Robert. "The Ancestors of Mike Gravel". WARGS.com. Retrieved 2007-05-02.

- ^ a b "No Shortcuts to the Top (2)", World Voice News, April 30, 2007. Accessed July 20, 2007.

- ^ a b Jo-Ann Moriarty, "Springfield native has sights set on top job", The Republican, February 19, 2007. Accessed July 7, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k David E. Rosenbaum (1971-10-26). "Fame Travels With Senator Gravel, the Man Who Read Pentagon Papers Into the Record". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ James Stuart Olson, Dictionary of the Vietnam War, Greenwood Press, 1988, p. 174 ff. ISBN 0313249431.

- ^ "Mike Gravel and the Draft". Mike Gravel for President. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ^ a b c d e f Martin Tolchin (1976-02-27). "Senators From Hinterlands Recall Early Years in City; U.S. Senators Recall Their Early Years in City". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Democracy Now, broadcast of forum on "How the Pentagon Papers Came to be Published...", July 2, 2007 [1]

- ^ a b Stephen Haycox, Gravel entry in American Legislative Leaders in the West, 1911-1994, Greenwood Press, 1997. ISBN 031330212X. p. 126.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Alex Koppelman, "Don't worry, be Mike Gravel", Salon.com, May 7, 2007. Accessed July 4, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Warren Weaver, Jr. (1971-07-02). "Impetuous Senator: Maurice Robert Gravel". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Democracy in Action (April 17 2007). "Interview with Former U.S. Sen. Mike Gravel". National Press Club. Retrieved 2007-04-29.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c Current Biography Yearbook 1972, H.W. Wilson Co., published in collection 1986, p. 184.

- ^ a b Robert KC Johnson, "Not Many Senators Have Found Themselves in Joe Lieberman's Predicament", History News Network, August 7, 2006. Accessed July 7, 2007.

- ^ Chinn, Ronald E. (1969). "The 1968 Election in Alaska". The Western Political Quarterly. 22 (3): 456–461. Retrieved 2007-11-25.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Senator Mike Gravel". National Initiative for Democracy. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ^ Terence Smith (1971-06-24). "5 SENATORS BACK PEKING SEAT IN U.N.; 4 Urge Admission Even at Cost of Ousting Taiwan". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d David E. Rosenbaum (1971-06-05). "Senators Reject Limits on Draft; 2-Year Plan Gains". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b David E. Rosenbaum (1971-02-03). "Stennis Favors 4-Year Draft Extension, but Laird Asks 2 Years". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Mike Gravel (1971-06-22). "Filibustering the Draft". Letters to the Editor. The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ David E. Rosenbaum (1971-06-24). "Senate Votes Closure in Draft Debate, 65 to 27". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b David E. Rosenbaum (1971-09-22). "Senate Approves Draft Bill, 55-30; President to Sign". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "'72 Draft Lottery Assigns No. 1 to Those Born Dec. 4". The New York Times. 1971-08-06. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ During Gravel's 2008 presidential campaign, he would claim that, "In 1971, Senator Mike Gravel (D-Alaska), by waging a lone five month filibuster, singlehandedly ended the draft in The United States thereby saving thousands of lives." See "Mike Gravel and the Draft". Mike Gravel for President 2008. Retrieved 2007-12-30. A 2006 article in The Nation stated that "It was Gravel who in 1971, against the advice of Democratic leaders in the Senate, launched a one-man filibuster to end the peacetime military draft, forcing the administration to cut a deal that allowed the draft to expire in 1973." See John Nichols (2006-04-15). "Pentagon Papers Figure Bids for Presidency". The Nation. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) Neither of these assessments is correct. From the beginning of the draft review process in February 1971, the Nixon administration wanted a two-year extension to June 1973, followed by a shift to an all-volunteer force — see David E. Rosenbaum (1971-02-03). "Stennis Favors 4-Year Draft Extension, but Laird Asks 2 Years". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-30.{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) — and this is what is what the September 1971 Senate vote gave them. Gravel's goal had been to block the renewal of the draft completely, thereby ending conscription past June 1971. See Mike Gravel (1971-06-22). "Filibustering the Draft". Letters to the Editor. The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-29.{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Neil Sheehan (1971-06-13). "Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces 3 Decades of Growing U. S. Involvement". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d "Timeline". Top Secret: The Battle for the Pentagon Papers. Annenberg Center for Communication at University of Southern California. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ^ "Beacon Press & the Pentagon Papers: History". Beacon Press. 2006-10-22. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b David E. Rosenbaum (1971-06-30). "Gravel Speaks 3 Hours; Senator Reading Study to Press". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b John W. Finney (1971-07-01). "Action by Gravel Vexes Many Senators". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "More Muskie Support". The New York Times. 1972-01-15. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Senator Gravel to Seek Vice-Presidential Spot". Associated Press for The New York Times. 1972-06-03. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Steven V. Roberts (1972-06-28). "Uncommitted Delegate in the Spotlight". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b James M. Naughton (1972-07-09). "The Air Went Out Of the Whoopee Cushions". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Max Frankel (1972-07-14). "Impassioned Plea: Dakotan Urges Party to Lead the Nation in Healing Itself McGovern Names Eagleton Running Mate; Calls Nixon 'Fundamental Issue'". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b The Nation, "The Foregone Convention", July 24, 1972

- ^ Ken Rudin (2004-09-27). "The Worst Acceptance Speech?". Political Junkie. NPR. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Mailer, Norman (1983). St. George and the Godfather. Arbor House. ISBN 0877955638.

- ^ a b c Thompson, Hunter S. (1973). Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail '72. New York: Popular Library. pp. 319–320.

- ^ Wallace Turner (1974-11-07). "Alaska Governor's Contest in Doubt". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "John Birch Official Seeks to Replace Gravel in Alaska". United Press International for The New York Times. 1974-01-11. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Senator Supports Pipeline; Would Make Operator Liable". United Press International for The New York Times. 1971-02-18. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e Wallace Turner (1980-08-26). "Polls Indicate Gravel Is in Trouble In Alaska's Senate Primary Today". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e f Wallace Turner (1980-08-28). "Gravel Loses a Bitter Fight In Senate Primary in Alaska". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Wallace Turner, "Side Issues Figure in Tricky Alaska Primary", The New York Times, July 6, 1982. Accessed July 7, 2007.

- ^ Politics1, "P2008: An Interview With Presidential Candidate Mike Gravel" by Ron Gunzburger, April 17, 2006

- ^ Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, Mike Gravel profile

- ^ "First Democrat to Announce Candidacy for President on Monday", Joe Lauria, CommonDreams New Centre, Published April 13, 2006

- ^ Kerry Eleveld, "Mike Gravel's big splash?", The Advocate, July 3, 2007. Accessed July 7, 2007.

- ^ "Mike Gravel Biography". Mike Gravel for President 2008. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- ^ Alex Grobman, Rafael Medoff. "Holocaust Denial: A Global Survey - 2003". David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ^ Ron Gunzburger (2006-04-17). "An Interview with Presidential Candidate Mike Gravel". Politics1.com. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e "How Mike Stands on the Issues". Mike Gravel for President 2008. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- ^ "Fmr. Sen. Mike Gravel: Unfiltered". Iowa Independent. 2007-05-14. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Washington: A 'Maverick' For President". The New York Times. 2006-04-18. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Philip Elliot, "Ex-Alaska Sen. Gravel Runs for President", Associated Press, April 17, 2006. Accessed March 10, 2007.

- ^ "FEC Form 3P for Mike Gravel". Federal Election Commission. 2007-04-15. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b No Breakout Candidate at Democratic Debate, ABC News, Apr. 26, 2007

- ^ Clinton edges ahead after first Democratic debate, The Times, Apr. 27, 2007

- ^ Hillary Clinton shines in Democratic candidates' debate, Ewen MacAskill, The Guardian, Apr. 27, 2007

- ^ Alessandra Stanley (2007-05-04). "A Show Where Candidates Are More Prop Than Player". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Must have got lost". Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ Mark Memmott, Jill Lawrence (2007-04-30). "Mike Gravel, soon to be a household name". USA Today. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Bill Schneider (2007-05-07). "Poll: Liberals moving toward Clinton; GOP race tightens". CNN.com. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Gravel Dismisses CNN, WMUR-TV And Union Leader Statement" (Press release). Mike Gravel for President 2008. 2007-03-19. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

{{cite press release}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ ""The Mainstream Media Has Gone Underground..."" (Press release). Mike Gravel for President 2008. 2007-06-05. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

{{cite press release}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Part I: CNN/YouTube Democratic presidential debate transcript". CNN.com. 2007-07-24. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Statistical Analysis Shows ABC News Unfair in Democrat Debate". NewsBusters. 2007-08-24. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "ABC News Poll" August 19, 2007, ABC News

- ^ "Report for Mike Gravel for President 2008". Federal Election Commission. 2007-10-17. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Alex Johnson (2007-10-31). "Democratic rivals target Clinton's vote on Iran". MSNBC.com. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "CNN keeps Gravel out of Democratic debate in Las Vegas". Associated Press for Las Vegas Sun. 2007-11-07. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Kucinich booted from Iowa debate". theHill.com. December 12, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-14.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Mike Gravel (2007-10-30). "Corporate Censorship!". Mike Gravel for President 2008. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Sarah Wheaton (2007-10-30). "Gravel vs. MSNBC". Retrieved 2007-12-29.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Larry Eichel (2007-10-30). "The debate is on. Here. Tonight". philly.com. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

- The Pentagon Papers Senator Gravel Edition. Vol. Five. Critical Essays. Boston. Beacon Press, 1972. 341p. plus 72p. of Index to Vol. I–IV of the Papers, Noam Chomsky, Howard Zinn, editors.

External links

Official Web sites

- National Initiative for Democracy (Founded by Mike Gravel)

Articles, analysis, biography

- Congressional Biography

- Biographical entry at The Democracy Foundation

- I'm voting for ... what's-his-name BBC article

- Vote for Mike Gravel article at Explorations Deep Into the Quagmire Known blog.

- Genealogy of Mike Gravel

Pentagon Papers

- Gravel edition of the Pentagon Papers Complete text, with supporting documents

- Democracy Now! Special: "How the Pentagon Papers Came to Be Published by the Beacon Press": Mike Gravel and Daniel Ellsberg (audio/video and transcript)

Interviews

- Blue State Observer — Interview

- Blue State Observer — Scones with the Senator

- Interview with Mike Gravel — The Eisenthal Report: Part 1, Part 2, Analysis

- Interview with Mike Gravel — CitizenPowerMagazine.net

- Mike Gravel on Antiwar Radio with Scott Horton

- Mike Gravel video interview: part 1, part 2, part 3, and part 4.

- Answering a question about gays in the military

- Conversation' With Mike Gravel

- Mike Gravel on CNN Situation Room with Wolf Blitzer

- Washington Journal interview and call-in on C-SPAN — part 1 part 2 part 3 part 4. Wide range of issues are discussed.

- Interviewed by Harold Channer. Discusses Louis O. Kelso, Binary Economics, National Initiative, and the interplay between the National Initiative, and Binary Economics. The two being the different faces of the same coin.

- Bernie Ward Program KGO Radio San Francisco May 23,2007