No edit summary |

|||

| (5 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

| signature_alt = Signature written in ink in a flowing script |

| signature_alt = Signature written in ink in a flowing script |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Ludwig van Beethoven'''{{refn|The prefix ''van'' to the surname "Beethoven" reflects the [[Dutch in Belgium|Flemish]] origins of the family; the surname suggests that "at some stage they lived at or near a [[beet]]-farm".{{sfn|Cooper|1996|p=36}}|group=n}} ({{IPAc-en|audio=En-LudwigVanBeethoven.ogg|ˈ|l|ʊ|d|v|ɪ|ɡ|_|v|æ|n|_|ˈ|b|eɪ|t|(|h|)|oʊ|v|ən}}; {{IPA-de|ˈluːtvɪç fan ˈbeːthoːfn̩|lang|De-Ludwig van Beethoven.ogg}}; baptised 17 December 1770{{spaced ndash}}26 March 1827) was a German [[composer]] and [[pianist]]. His works span the transition between the [[Classical period (music)|classical]] and [[Romantic music|romantic]] eras in [[classical music]]. |

'''Ludwig van Beethoven'''{{refn|The prefix ''van'' to the surname "Beethoven" reflects the [[Dutch in Belgium|Flemish]] origins of the family; the surname suggests that "at some stage they lived at or near a [[beet]]-farm".{{sfn|Cooper|1996|p=36}}|group=n}} ({{IPAc-en|audio=En-LudwigVanBeethoven.ogg|ˈ|l|ʊ|d|v|ɪ|ɡ|_|v|æ|n|_|ˈ|b|eɪ|t|(|h|)|oʊ|v|ən}}; {{IPA-de|ˈluːtvɪç fan ˈbeːthoːfn̩|lang|De-Ludwig van Beethoven.ogg}}; baptised 17 December 1770{{spaced ndash}}26 March 1827) was a German [[composer]] and [[pianist]]. His works span the transition between the [[Classical period (music)|classical]] and [[Romantic music|romantic]] eras in [[classical music]]. He is a crucial figure of [[classical music]], and is considered one of the greatest and most influential composers of all time.<ref>{{cite web||url=https://www.britannica.com/list/10-classical-music-composers-to-know|last=Zelazko|first=Alikja|title=10 Classical Music Composers to Know|website=[[Encyclopaedia Britannica]]}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.classical-music.com/article/50-greatest-composers-all-time|title=The 50 Greatest Composers of All Time|website=www.classical-music.com}}</ref><ref name="Smith">{{Cite journal| year = 1927| last = Smith| first = Brent | title = Ludwig van Beethoven| journal = Proceedings of the Musical Association| volume = 53| pages = pp. 85-94}}</ref><ref name="Palmer">{{cite book | year = 1996| last = Palmer| first = Willard A. | title = First Sonatina Book: Alfred Masterwork Edition - Piano Sheet Music Collection| page = 16 | location = California | publisher = Alfred Publishing}}</ref><ref>{{cite web||url=https://www.classicfm.com/composers/beethoven/best-pieces-ever-written/|last=Suchet|first=John|title=Definitively the 20 greatest Beethoven works of all time|website=classicfm.com}}</ref><ref>{{cite web||url=https://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/23/arts/music/23composers.html|last=Tommatini|first=Anthony|title=The Greatest|website=[[The New York Times]].com}}</ref> |

||

His career has conventionally been divided into early, middle, and late periods. The "early" period in which he forged his craft, is typically seen to last until 1802. His "middle" period, (sometimes characterised as "heroic") shows an individual development from the "classical" styles of [[Franz Joseph Haydn|Joseph Haydn]] and [[Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart]], covers the years 1802 to 1812, during which he increasingly suffered from [[deafness]]. In the "late" period from 1812 to his death in 1827, he extended his innovations in musical form and expression. |

|||

Beethoven was born in [[Bonn]]. His musical talent was obvious at an early age, and he was initially harshly and intensively taught by his father [[Johann van Beethoven]]. He was later taught by the composer and conductor [[Christian Gottlob Neefe]], under whose tuition he published his first work, a set of keyboard variations, in 1783. He found relief from a dysfunctional home life with the family of [[Helene von Breuning]], whose children he loved, befriended and taught piano. At age 21, he moved to [[Vienna]] and studied composition with Haydn. Beethoven then gained a reputation as a virtuoso pianist, and he was soon courted by [[Karl Alois, Prince Lichnowsky]] for compositions, which resulted in his three [[Piano Trios, Op. 1 (Beethoven)|Opus 1]] [[piano trio]]s (the earliest works to which he accorded an [[opus number]]) in 1795. |

Beethoven was born in [[Bonn]]. His musical talent was obvious at an early age, and he was initially harshly and intensively taught by his father [[Johann van Beethoven]]. He was later taught by the composer and conductor [[Christian Gottlob Neefe]], under whose tuition he published his first work, a set of keyboard variations, in 1783. He found relief from a dysfunctional home life with the family of [[Helene von Breuning]], whose children he loved, befriended and taught piano. At age 21, he moved to [[Vienna]] and studied composition with Haydn. Beethoven then gained a reputation as a virtuoso pianist, and he was soon courted by [[Karl Alois, Prince Lichnowsky]] for compositions, which resulted in his three [[Piano Trios, Op. 1 (Beethoven)|Opus 1]] [[piano trio]]s (the earliest works to which he accorded an [[opus number]]) in 1795. |

||

Revision as of 00:44, 30 March 2020

Ludwig van Beethoven | |

|---|---|

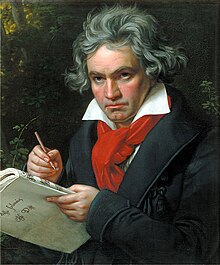

Portrait of Beethoven, 1820 | |

| Born | |

| Baptised | 17 December 1770 |

| Died | 26 March 1827 (aged 56) |

| Works | List of compositions |

| Signature | |

Ludwig van Beethoven[n 1] (/ˈlʊdvɪɡ væn ˈbeɪt(h)oʊvən/ ; German: [ˈluːtvɪç fan ˈbeːthoːfn̩] ; baptised 17 December 1770 – 26 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. His works span the transition between the classical and romantic eras in classical music. He is a crucial figure of classical music, and is considered one of the greatest and most influential composers of all time.[2][3][4][5][6][7]

His career has conventionally been divided into early, middle, and late periods. The "early" period in which he forged his craft, is typically seen to last until 1802. His "middle" period, (sometimes characterised as "heroic") shows an individual development from the "classical" styles of Joseph Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, covers the years 1802 to 1812, during which he increasingly suffered from deafness. In the "late" period from 1812 to his death in 1827, he extended his innovations in musical form and expression.

Beethoven was born in Bonn. His musical talent was obvious at an early age, and he was initially harshly and intensively taught by his father Johann van Beethoven. He was later taught by the composer and conductor Christian Gottlob Neefe, under whose tuition he published his first work, a set of keyboard variations, in 1783. He found relief from a dysfunctional home life with the family of Helene von Breuning, whose children he loved, befriended and taught piano. At age 21, he moved to Vienna and studied composition with Haydn. Beethoven then gained a reputation as a virtuoso pianist, and he was soon courted by Karl Alois, Prince Lichnowsky for compositions, which resulted in his three Opus 1 piano trios (the earliest works to which he accorded an opus number) in 1795.

His first major orchestral work, the First Symphony, appeared in 1800, and his first set of string quartets was published in 1801. During this period, his hearing began to deteriorate, but he continued to conduct, premiering his Third and Fifth Symphonies in 1804 and 1808, respectively. His Violin Concerto appeared in 1806. His last piano concerto (No. 5, Op. 73, known as the 'Emperor'), dedicated to his great patron Archduke Rudolf of Austria, was premiered in 1810, but not with the composer as soloist. He was almost completely deaf by 1814, and he then gave up performing and appearing in public.

In the following years, removed from society, Beethoven composed many of his most admired works including his later symphonies and his mature chamber music and piano sonatas. His only opera Fidelio, which had been first performed in 1805, was revised to its final version in 1814. He composed his Missa Solemnis in the years 1819–1823, and his final, Ninth, Symphony, one of the first examples of a choral symphony, in 1822–1824. Written in his last years, his late string quartets of 1825–26 are amongst his final achievements. After some months of bedridden illness he died in 1827.

Beethoven's works in all genres remain mainstays of the classical music repertoire; he is also remembered for his troublesome relationship with his contemporaries.

Life and career

Background and early life

Beethoven was the grandson of Ludwig van Beethoven (1712–1773), a musician from the town of Mechelen in the Austrian Duchy of Brabant (in what is now the Flemish region of Belgium) who had moved to Bonn at the age of 21.[8][9] Ludwig was employed as a bass singer at the court of Clemens August, Archbishop-Elector of Cologne, eventually rising to become, in 1761, Kapellmeister (music director) and hence a pre-eminent musician in Bonn. The portrait he commissioned of himself towards the end of his life remained displayed in his grandson's rooms as a talisman of his musical heritage.[10] Ludwig had one son, Johann (1740–1792), who worked as a tenor in the same musical establishment and gave keyboard and violin lessons to supplement his income.[8] Johann married Maria Magdalena Keverich in 1767; she was the daughter of Heinrich Keverich (1701–1751), who had been the head chef at the court of the Archbishopric of Trier.[11] Beethoven was born of this marriage in Bonn. There is no authentic record of the date of his birth; however, the registry of his baptism, in the Catholic Parish of St. Remigius on 17 December 1770, survives, and the custom in the region at the time was to carry out baptism within 24 hours of birth. There is a consensus, (with which Beethoven himself agreed) that his birth date was 16 December, but no documentary proof of this.[12]

Of the seven children born to Johann van Beethoven, only Ludwig, the second-born, and two younger brothers survived infancy. Kaspar Anton Karl was born on 8 April 1774, and Nikolaus Johann, the youngest, was born on 2 October 1776.[13]

Beethoven's first music teacher was his father. He later had other local teachers: the court organist Gilles van den Eeden (d. 1782), Tobias Friedrich Pfeiffer (a family friend, who provided keyboard tuition), and Franz Rovantini (a relative, who instructed him in playing the violin and viola).[8] From the outset his tuition regime, which began in his fifth year, was harsh and intensive, often reducing him to tears; with the involvement of the insomniac Pfeiffer there were irregular late-night sessions with the young Beethoven being dragged from his bed to the keyboard.[14] His musical talent was obvious at a young age. Johann, aware of Leopold Mozart's successes in this area (with his son Wolfgang and daughter Nannerl), attempted to promote his son as a child prodigy, claiming that Beethoven was six (he was seven) on the posters for his first public performance in March 1778.[15]

Bonn 1780–1792

In 1780 or 1781, Beethoven began his studies with his most important teacher in Bonn, Christian Gottlob Neefe.[16] Neefe taught him composition; in March 1783 appeared Beethoven's first published work, a set of keyboard variations (WoO 63).[13] [n 2] Beethoven soon began working with Neefe as assistant organist, at first unpaid (1782), and then as a paid employee (1784) of the court chapel.[18] His first three piano sonatas, WoO 47, sometimes known as "Kurfürst" ("Elector") for their dedication to the Elector Maximilian Friedrich (1708–1784), were published in 1783.[19] In the same year the first printed reference to Beethoven appeared in the Magazin der Musik - "Louis van Beethoven [sic] [...] a boy of 11 years and most promising talent. He plays the piano very skilfully and with power, reads at sight very well [...] the chief piece he plays is Das wohltempierte Klavier of Sebastian Bach, which Herr Neefe puts into his hands [...]"[8]

Maximilian Friedrich's successor as the Elector of Bonn was Maximilian Franz. He gave some support to Beethoven, appointing him Court Organist and paying towards his visit to Vienna of 1792. [11][20]

He was introduced in these years to several people who became important in his life. He often visited the cultivated von Breuning family, where he taught piano to some of the children, and where the widowed Frau von Breuning offered him a motherly friendship. Here he also met Franz Wegeler, a young medical student, who became a lifelong friend (and was to marry one of the von Breuning daughters). The von Breuning family environment offered an alternative to his home life, which was increasingly dominated by his father's decline. Another frequenter of the von Breunings was Count Ferdinand von Waldstein, who became a friend and financial supporter during Beethoven's Bonn period.[21][22] .[23] Waldstein was to commission in 1791 Beethoven's first work for the stage, the ballet Musik zu einem Ritterballett (WoO 1).[24]

In the period 1785–90 there is virtually no record of Beethoven's activity as a composer. This may be attributed to the lukewarm response his initial publications had attracted, and also to ongoing problems in the Beethoven family.[25] His mother died in 1787, shortly after Beethoven’s first visit to Vienna, where he stayed for about two weeks and almost certainly met with Mozart.[21]. In 1789 Beethoven's father was forcibly retired from the service of the Court (as a consequence of his alcoholism) and it was ordered that half of his father's pension be paid directly to him for support of the family.[26] He contributed further to the family's income by teaching (to which Wegeler said he had "an extraordinary aversion"[27]) and by playing viola in the court orchestra. This familiarized him with a variety of operas, including works by Mozart, Gluck and Paisiello.[28] Here he also befriended Anton Reicha, a composer, flautist and violinist of about his own age who was a nephew of the court orchestra's conductor, Josef Reicha.[29]

From 1790 to 1792, Beethoven composed a number of works (none were published at the time) showing a growing range and maturity. Musicologists have identified a theme similar to those of his Third Symphony in a set of variations written in 1791.[30] It was perhaps on Neefe's recommendation that Beethoven received his first commissions; the Literary Society in Bonn commissioned a cantata to mark the occasion of the death in 1790 of Joseph II (WoO 87), and a further cantata, to celebrate the subsequent accession of Leopold II as Holy Roman Emperor (WoO 88), may have been commissioned by the Elector.[31]. These two Emperor Cantatas were never performed at the time and they remained lost until the 1880s, when they were described by the composer Johannes Brahms as "Beethoven through and through" and as such prophetic of the style which would mark his music as distinct from the classical tradition.[32]

Beethoven was probably first introduced to Joseph Haydn in late 1790, when the latter was travelling to London and stopped in Bonn around Christmas time.[33] A year and a half later, they met in Bonn on Haydn's return trip from London to Vienna in July 1792, when Beethoven played in the orchestra at the Redoute in Godesberg. It is likely that arrangements were made at that time for Beethoven to study with the older master.[34] Waldstein wrote to him before his departure: “You are going to Vienna in fulfilment of your long-frustrated wishes […] With the help of assiduous labour you shall receive Mozart’s spirit from Haydn’s hands.”[21]

Vienna 1792–1802

Beethoven left Bonn for Vienna in November 1792, amid rumours of war spilling out of France; he learned shortly after his arrival that his father had died.[35][36] Over the next few years, Beethoven responded to the widespread feeling that he was a successor to the recently deceased Mozart by studying that master's work and writing works with a distinctly Mozartean flavour.[37]

He did not immediately set out to establish himself as a composer, but rather devoted himself to study and performance. Working under Haydn's direction,[38] he sought to master counterpoint. He also studied violin under Ignaz Schuppanzigh.[39] Early in this period, he also began receiving occasional instruction from Antonio Salieri, primarily in Italian vocal composition style; this relationship persisted until at least 1802, and possibly as late as 1809.[40]

With Haydn's departure for England in 1794, Beethoven was expected by the Elector to return home to Bonn. He chose instead to remain in Vienna, continuing his instruction in counterpoint with Johann Albrechtsberger and other teachers. In any case, by this time it must have seemed clear to his employer that Bonn would fall to the French, as it did in October 1794, effectively leaving Beethoven without a stipend or the necessity to return.[41] However, a number of Viennese noblemen had already recognised his ability and offered him financial support, among them Prince Joseph Franz Lobkowitz, Prince Karl Lichnowsky, and Baron Gottfried van Swieten.[42]

Assisted by his connections with Haydn and Waldstein, Beethoven began to develop a reputation as a performer and improviser in the salons of the Viennese nobility.[43] His friend Nikolaus Simrock began publishing his compositions, starting with a set of keyboard variations on a theme of Dittersdorf (WoO 66).[44] By 1793, he had established a reputation in Vienna as a piano virtuoso, but he apparently withheld works from publication so that their eventual appearance would have greater impact.[42]

His first public performance in Vienna was in March 1795, where he first performed one of his piano concertos. [n 3][46] Shortly after this performance, he arranged for the publication of the first of his compositions to which he assigned an opus number, the three piano trios, Opus 1. These works were dedicated to his patron Prince Lichnowsky,[45] and were a financial success; Beethoven's profits were nearly sufficient to cover his living expenses for a year.[47] In 1799 Beethoven participated in (and won) a notorious piano 'duel' at the home of Baron Raimund Wetzlar (a former patron of Mozart) against the virtuoso Joseph Wölfl; and in the following year he similarly triumphed against Daniel Steibelt at the salon of Count Moritz von Fries.[48] Beethoven's eighth piano sonata the "Pathétique" (Op. 13), published in 1799 is described by the musicologist Barry Cooper as "surpass[ing] any of his previous compositions, in strength of character, depth of emotion, level of originality, and ingenuity of motivic and tonal manipulation."[49]

Beethoven composed his first six string quartets (Op. 18) between 1798 and 1800 (commissioned by, and dedicated to, Prince Lobkowitz). They were published in 1801. He also completed his Septet (Op. 20) in 1799, which was one of his most popular works during his lifetime. With premieres of his First and Second Symphonies in 1800 and 1803, he became regarded as one of the most important of a generation of young composers following Haydn and Mozart. But his melodies, musical development, use of modulation and texture, and characterisation of emotion all set him apart from his influences, and heightened the impact some of his early works made when they were first published.[50] For the premiere of his First Symphony, he hired the Burgtheater on 2 April 1800, and staged an extensive programme, including works by Haydn and Mozart, as well as his Septet, the Symphony, and one of his piano concertos (the latter three works all then unpublished). The concert, which the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung described as "the most interesting concert in a long time," was not without difficulties; among the criticisms was that "the players did not bother to pay any attention to the soloist."[51] By the end of 1800, Beethoven and his music were already much in demand from patrons and publishers.[52]

In May 1799, he taught piano to the daughters of Hungarian Countess Anna Brunsvik. During this time, he fell in love with the younger daughter Josephine. Amongst his other students, from 1801 to 1805, he tutored Ferdinand Ries, who went on to become a composer and later wrote about their encounters. The young Carl Czerny, who later became a renowned music teacher himself, studied with Beethoven from 1801 to 1803. In late 1801, he met a young countess, Julie ("Giulietta") Guicciardi, through the Brunsvik family; he mentions his love for Julie in a November 1801 letter to a friend, but class difference prevented any consideration of pursuing this. He later dedicated his Sonata No. 14, now commonly known as the Moonlight Sonata, to her.[53]

In the spring of 1801 he completed The Creatures of Prometheus, a ballet. The work received numerous performances in 1801 and 1802, and he rushed to publish a piano arrangement to capitalise on its early popularity.[54] In the spring of 1802 he completed the Second Symphony, intended for performance at a concert that was cancelled. The symphony received its premiere instead at a subscription concert in April 1803 at the Theater an der Wien, where he had been appointed composer in residence. In addition to the Second Symphony, the concert also featured the First Symphony, the Third Piano Concerto, and the oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives. Reviews were mixed, but the concert was a financial success; he was able to charge three times the cost of a typical concert ticket.[55]

His business dealings with publishers also began to improve in 1802 when his brother Kaspar, who had previously assisted him casually, began to assume a larger role in the management of his affairs. In addition to negotiating higher prices for recently composed works, Kaspar also began selling some of his earlier unpublished compositions, and encouraged him (against Beethoven's preference) to also make arrangements and transcriptions of his more popular works for other instrument combinations. Beethoven acceded to these requests, as he could not prevent publishers from hiring others to do similar arrangements of his works.[56]

1802–1812

Deafness

Beethoven told the English pianist Charles Neate (in 1815) that he dated his hearing loss from a fit he suffered in 1798 induced by a quarrel with a singer.[57]. During its gradual decline, his hearing was further impeded by a severe form of tinnitus.[58] As early as 1801, he wrote to Wegeler and another friend Karl Amenda, describing his symptoms and the difficulties they caused in both professional and social settings (although it is likely some of his close friends were already aware of the problems).[59] The cause was probably otosclerosis, perhaps accompanied by degeneration of the auditory nerve.[60][n 4]

On the advice of his doctor, he moved to the small Austrian town of Heiligenstadt, just outside Vienna, from April to October 1802 in an attempt to come to terms with his condition. There he wrote the document now known as the “Heiligenstadt Testament”, a letter to his brothers which records his thoughts of suicide due to his growing deafness and records his resolution to continue living for and through his art. The letter was never actually sent and was discovered in the composer’s papers after his death.[63] The letters to Wegeler and Amenda were not so despairing; in them Beethoven commented also on his ongoing professional and financial success at this period, and his determination, as he expressed it to Wegeler, to “seize Fate by the throat; it shall certainly not crush me completely.”[60] In 1806, Beethoven noted on of his musical sketches "Let your deafness no longer be a secret – even in art."[64].

Beethoven's hearing loss did not prevent him from composing music, but it made playing at concerts—a important source of income at this phase of his life—increasingly difficult. (It also contributed substantially to his social withdrawal.)[60] Czerny remarked that Beethoven could still hear speech and music normally until 1812.[65] But in April and May 1814, playing in his Piano Trio, Op. 97 (known as the ’’Archduke’’), he made his last public appearances as a soloist. The composer Louis Spohr noted : “the piano was badly out of tune, which Beethoven minded little, since he did not hear it […] there was scarcely anything left of the virtuosity of the artist […] I was deeply saddened.”[66] [n 5] From 1814 onwards Beethoven used for conversation ear-trumpets designed by Johann Nepomuk Maelzel, and a number of these are on display at the Beethoven-Haus in Bonn.[68]

The ‘heroic’ period

Beethoven’s return to Vienna from Heiligenstadt was marked by a change in musical style, and is now often designated as the start of his middle or "heroic" period characterised by many original works composed on a grand scale.[69] According to Carl Czerny, Beethoven said, "I am not satisfied with the work I have done so far. From now on I intend to take a new way."[70] An early major work employing this new style was the Third Symphony in E flat Op. 55, known as the Eroica, written in 1803-4. The idea of creating a symphony based on the career of Napoleon may have been suggested to Beethoven by Count Bernadotte in 1798[71]. Beethoven, sympathetic to the ideal of the heroic revolutionary leader, originally gave the symphony the title "Bonaparte", but disillusioned by Napoleon declaring himself Emperor in 1804, he scratched napoleon's name from the manuscript's title page, and the symphony was published in 1806 with its present title and the subtitle "to celebrate the memory of a great man."[71] The Eroica wass longer and larger in scope than any previous symphony. When it premiered in early 1805 it received a mixed reception. Some listeners objected to its length or misunderstood its structure, while others viewed it as a masterpiece.[72]

Other middle period works extend in the same dramatic manner the musical language Beethoven had inherited. The Rasumovsky string quartets, and the Waldstein and Appassionata piano sonatas share the heroic spirit of the Third Symphony.[71]. Other works of this period include the Fourth through Eighth Symphonies, the oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives, the opera Fidelio, and the Violin Concerto.[73] In an 1810 review, Beethoven was hailed by E. T. A. Hoffmann as one of the three great "Romantic" composers, along with Haydn and Mozart; Hoffmann called his Fifth Symphony "one of the most important works of the age".[74]

During this time his income came from publishing his works, from performances of them, and from his patrons, for whom he gave private performances and copies of works they commissioned for an exclusive period prior to their publication. Some of his early patrons, including Prince Lobkowitz and Prince Lichnowsky, gave him annual stipends in addition to commissioning works and purchasing published works.[75] Perhaps his most important aristocratic patron was Archduke Rudolf of Austria , Archbishop of Olomouc and Cardinal-Priest, and the youngest son of Emperor Leopold II, who in 1803 or 1804 began to study piano and composition with him. They became friends, and their meetings continued until 1824.[76] Beethoven dedicated 14 compositions to Rudolph, including the Archduke Trio (1811) and Missa solemnis (1823).

His position at the Theater an der Wien was terminated when the theatre changed management in early 1804, and he was forced to move temporarily to the suburbs of Vienna with his friend Stephan von Breuning. This slowed work on Leonore, (his original title for his opera), his largest work to date, for a time. It was delayed again by the Austrian censor, and finally premiered, under its present tile of Fidelio in November 1805 to houses that were nearly empty because of the French occupation of the city. In addition to being a financial failure, this version of Fidelio was also a critical failure, and Beethoven began revising it.[77]

Despite this failure, Beethoven continued to attract recognition. In 1807 the musician and publisher Muzio Clementi secured the rights for publishing his works in England, and Haydn's former patron Prince Esterházy commissioned a mass (the Mass in C, Op. 86) for his wife's name-day. But he could not count on such recognition alone. A colossal benefit concert which he organized in December 1808, including the premieres of the Fifth and Sixth (Pastoral) symphonies, the Fourth Piano Concerto, extracts from the Mass in C, the scena and aria Ah! perfido Op. 65 and the Choral Fantasy op. 80, was under-rehearsed, involved many stops and starts, and had a reception that was mixed at the best.[71]

In the autumn of 1808, after having been rejected for a position at the Royal Theatre, Beethoven received an offer from Napoleon's brother Jérôme Bonaparte, then king of Westphalia, for a well-paid position as Kapellmeister at the court in Cassel. To persuade him to stay in Vienna, the Archduke Rudolph, Prince Kinsky and Prince Lobkowitz, after receiving representations from the composer's friends, pledged to pay him a pension of 4000 florins a year. Only Archduke Rudolph paid his share of the pension on the agreed date.[78] Kinsky, immediately called to military duty, did not contribute and soon died after falling from his horse.[79] The Austrian currency destabilized and Lobkowitz went bankrupt in 1811, so that Beethoven eventually had recourse to the law, which in 1815 brought him some recompense.[80].

"The Immortal Beloved"

In the spring of 1811 Beethoven became seriously ill, suffering headaches and high fever. On the advice of his doctor, he spent six weeks in the Bohemian spa town of Teplitz. The following winter, which was dominated by work on the Seventh Symphony, he was again ill, and his doctor ordered him to spend the summer of 1812 at the spa Teplitz. It is certain that he was at Teplitz when he wrote a ten-page love letter to his "Immortal Beloved", which he never sent to its addressee.[81]

The identity of the intended recipient was long a subject of debate, although the musicologist Maynard Solomon has effectively proved that the intended recipient must have been Antonie Brentano; other candidates have included Juliette Guicciardi, Therese Malfatti and Josephine Brunsvik.[82] [n 6]

All of these had been regarded by Beethoven as possible soulmates during his first decade in Vienna. Guicciardi, although she flirted with Beethoven, never had any serious interest in him and married Wenzel Robert von Gallenberg in November 1803. (Beethoven insisted to his later secretary and biographer, Anton Schindler, that Gucciardi had "sought me out, crying, but I scorned her.")[84] Josephine had since Beethoven's initial infatuation with her married the elderly Jospeh Count Deym, who died in 1804. Beethoven began to visit her and commenced a passionate correspondence. Initially he accepted that Josephine could not love him, but he continue to address himself to her even after she had moved to Budapest, finally demonstrating that he had got the message in his last letter to her of 1807: "I thank you for wishing still to appear as if I were not altogether banished from your memory".[85] Malfatti was the niece of Beethoven's doctor in 1808-1809, and he proposed to her in 1810. He was 40, she was 19 - the proposal was rejected.[86]

Antonie (Toni) Brentano (née von Birkenstock), ten years younger than the composer, was the wife of Franz Brentano, the half-brother of Bettina Brentano (who in 1811 married the poet Achim von Arnim) and of the poet and writer Clemens Brentano. Bettina met Beethoven in Vienna in 1810 and this was the composer's introduction to the family. It would seem that Antonie and Beethoven had an affair during 1811-1812. Antonie left Vienna with her husband in late 1812 and never met with (or apparently corresponded with) Beethoven again. although in her later years she wrote and spoke fondly of him.[87]

1813–1822

Family problems

In early 1813 Beethoven apparently went through a difficult emotional period, and his compositional output dropped. His personal appearance degraded—it had generally been neat—as did his manners in public, notably when dining.[88]

Family issues may have played a part in this. Beethoven had visited his brother Johann at the end of October 1812. He wished to end Johann's cohabitation with Therese Obermayer, a woman who already had an illegitimate child. He was unable to convince Johann to end the relationship and appealed to the local civic and religious authorities, but Johann and Therese married on 8 November.[89]

The illness and eventual death of his brother Kaspar from tuberculosis became an increasing concern. Kaspar had been ill for some time; in 1813 Beethoven lent him 1500 florins, to procure the repayment of which he was ultimately led to complex legal measures.[90] After Kaspar died on 15 November 1815, Beethoven immediately became embroiled in a protracted legal dispute with Kaspar's wife Johanna over custody of their son Karl, then nine years old. Beethoven had successfully applied to Kaspar to have himself named sole guardian of the boy. A late codicil to Kaspar's will gave him and Johanna joint guardianship.[91] While Beethoven was successful at having his nephew removed from her custody in January 1816, and had him removed to a private school[92] in 1818 he was again preoccupied by the legal processes around Karl. While giving evidence to the court for the nobility, the Landrechte, Beethoven was unable to prove that he was of noble birth and as a consequence, on 18 December 1818 the case was transferred to the civil magistracy of Vienna, where he lost sole guardianship.[92][n 7] He only regained custody after intensive legal struggles in 1820.[93] During the years that followed, Beethoven frequently interfered in his nephew's life in what Karl perceived as an overbearing manner.[94]

Career

Beethoven was finally motivated to begin significant composition again in June 1813, when news arrived of Napoleon's deafeat at the Battle of Vitoria by a coalition the Duke of Wellington. This stimulated him to write the orchestral work Wellington's Victory. It was first performed on 8 December, along with his Seventh Symphony, at a charity concert for victims of the war. The work was a popular hit, probably because of its programmatic style, which was entertaining and easy to understand. It recpoeived repeat performances at concerts he staged in January and February 1814. His renewed popularity led to demands for a revival of Fidelio, which, in its third revised version, was also well received at its July opening. That summer he composed a piano sonata for the first time in five years (No. 27, Opus 90). This work was in a markedly more Romantic style than his earlier sonatas. He was also one of many composers who produced music in a patriotic vein to entertain the many heads of state and diplomats who came to the Congress of Vienna that began in November 1814. His output of songs included his only song cycle, "An die ferne Geliebte," and the extraordinarily expressive second setting of the poem "An die Hoffnung" (Op. 94) in 1815. Compared to its first setting in 1805 (a gift for Josephine Brunsvik), it was "far more dramatic ... The entire spirit is that of an operatic scena."[95]

Between 1815 and 1817 Beethoven's output dropped again. He attributed part of this to a lengthy illness (he called it an "inflammatory fever") that he had for more than a year, starting in October 1816.[96] Biographers have speculated on a variety of other reasons that also contributed to the decline, including the his love-interests and the harsh censorship policies of the Austrian government.

By early 1818 his health had improved, and his nephew moved in with him in January. On the downside, his hearing had deteriorated to the point that conversation became difficult, necessitating the use of conversation books. His household management had also improved somewhat; Nanette Streicher, who had assisted in his care during his illness, continued to provide some support, and he finally found a skilled cook.[97] His musical output in 1818 was still somewhat reduced, but included song collections and the "Hammerklavier" Sonata, as well as sketches for two symphonies that eventually coalesced into the epic Ninth.

In 1819 Beethoven began work on the Diabelli Variations and the Missa Solemnis, composing over the next few years piano sonatas and bagatelles to satisfy the demands of publishers and the need for income. He was ill again for an extended time in 1821, and completed the Missa in 1823, three years after its original due date. Around 1822 his brother Johann began to assist him in his business affairs, including him lending him money against ownership of some of his compositions.[98]

The conversation books

As a result of Beethoven's hearing loss, Beethoven's conversation books are an unusually rich written resource for this period. Used primarily in the last ten or so years of his life, his friends wrote in these books so that he could know what they were saying, and he then responded either orally or in the book. The books contain discussions about music and other matters, and give insights into his thinking; they are a source for investigations into how he intended his music should be performed, and also his perception of his relationship to art. It was suggested by Beethoven's biographer Alexander Wheelock Thayer that, of 400 conversation books, 264 were destroyed (and others were altered) after his death by his secretary Schindler, who wished only an idealised biography of the composer to survive.[99] The music historian Theodore Albrecht has however demonstrated that Thayer's allegations were over the top.[n 8] Presently 136 books covering the period 1819-1827 are preserved at the Staatsbibliothek Berlin, with another two at the Beethoven-Haus in Bonn.[101]

1822–1827

Two commissions in 1822 improved Beethoven's financial prospects. The Philharmonic Society of London offered a commission for a symphony, and Prince Nikolas Golitsin of Saint Petersburg offered to pay Beethoven's price for three string quartets. The first of these commissions spurred him to finish the Ninth Symphony, which was first performed, along with the Missa Solemnis, on 7 May 1824, to great acclaim at the Kärntnertortheater. The Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung gushed, "inexhaustible genius had shown us a new world", and Carl Czerny wrote that his symphony "breathes such a fresh, lively, indeed youthful spirit ... so much power, innovation, and beauty as ever [came] from the head of this original man, although he certainly sometimes led the old wigs to shake their heads." Unlike his more lucrative earlier concerts, this did not make him much money, as the expenses of mounting it were significantly higher.[102] A second concert on 24 May, in which the producer guaranteed him a minimum fee, was poorly attended; nephew Karl noted that "many people [had] already gone into the country". It was Beethoven's last public concert.[103]

Beethoven then turned to writing the string quartets for Golitsin. This series of quartets, known as the "Late Quartets," went far beyond what musicians or audiences were ready for at that time. Composer Louis Spohr called them "indecipherable, uncorrected horrors." Opinion has changed considerably from the time of their first bewildered reception: their forms and ideas inspired musicians and composers including Richard Wagner and Béla Bartók, and continue to do so. Of the late quartets, Beethoven's favourite was the Fourteenth Quartet, op. 131 in C♯ minor, which he rated as his most perfect single work.[104] The last musical wish of Schubert was to hear the Op. 131 quartet, which he did on 14 November 1828, five days before his death.[105]

He wrote the last quartets amidst failing health. In April 1825 he was bedridden, and remained ill for about a month. The illness—or more precisely, his recovery from it—is remembered for having given rise to the deeply felt slow movement of the Fifteenth Quartet, which he called "Holy song of thanks ('Heiliger Dankgesang') to the divinity, from one made well." He went on to complete the quartets now numbered Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Sixteenth. The last work completed by Beethoven was the substitute final movement of the Thirteenth Quartet, which replaced the difficult Große Fuge. Shortly thereafter, in December 1826, illness struck again, with episodes of vomiting and diarrhoea that nearly ended his life.[citation needed]

In 1825, his nine symphonies were performed in a cycle for the first time, by the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra under Johann Philipp Christian Schulz. This was repeated in 1826.[106]

Beethoven's nephew Karl attempted suicide on 31 July 1826 by shooting himself in the head. He survived and was brought to his mother's house, where he recuperated. He and Beethoven were reconciled, but Karl insisted on joining the army and last saw Beethoven in January 1827.[107]

Illness and death

Beethoven was bedridden for most of his remaining months, and many friends came to visit. He died on 26 March 1827 at the age of 56 during a thunderstorm. His friend Anselm Hüttenbrenner, who was present at the time, said that there was a peal of thunder at the moment of death. An autopsy revealed significant liver damage, which may have been due to heavy alcohol consumption.[108] It also revealed considerable dilation of the auditory and other related nerves.[109][110]

Beethoven's funeral procession on 29 March 1827 was attended by an estimated 20,000 people. Franz Schubert, who died the following year and was buried next to him, was one of the torchbearers. He was buried in a dedicated grave in the Währing cemetery, north-west of Vienna, after a requiem mass at the church of the Holy Trinity (Dreifaltigkeitskirche). His remains were exhumed for study in 1862, and moved in 1888 to Vienna's Zentralfriedhof.[108] In 2012, his crypt was checked to see if his teeth had been stolen during a series of grave robberies of other famous Viennese composers.[111]

There is dispute about the cause of his death: alcoholic cirrhosis, syphilis, infectious hepatitis, lead poisoning, sarcoidosis and Whipple's disease have all been proposed.[112] Friends and visitors before and after his death clipped locks of his hair, some of which have been preserved and subjected to additional analysis, as have skull fragments removed during the 1862 exhumation.[113] Some of these analyses have led to controversial assertions that he was accidentally poisoned to death by excessive doses of lead-based treatments administered under instruction from his doctor.[114][115]

Music

Overview

Beethoven is acknowledged to be one of the giants of classical music. Together with Bach and Johannes Brahms, he is referred to as one of the "three Bs" who epitomize that tradition. He was a pivotal figure in the transition from the 18th century musical classicism to 19th century romanticism, and his influence on subsequent generations of composers was profound. His music features twice on the Voyager Golden Record, a phonograph record containing a broad sample of the images, common sounds, languages, and music of Earth, sent into outer space with the two Voyager probes.[116]

Beethoven composed in several musical genres and for a variety of instrument combinations. His works for symphony orchestra include nine symphonies (of which the Ninth Symphony includes a chorus), and about a dozen pieces of "occasional" music. He wrote seven concerti for one or more soloists and orchestra, as well as four shorter works that include soloists accompanied by orchestra. His only opera is Fidelio; other vocal works with orchestral accompaniment include two masses and a number of shorter works.

His large body of compositions for piano includes 32 piano sonatas and numerous shorter pieces, including arrangements of some of his other works. Works with piano accompaniment include 10 violin sonatas, 5 cello sonatas, and a sonata for French horn, as well as numerous lieder.

He also wrote a significant quantity of chamber music. In addition to 16 string quartets, he wrote five works for string quintet, seven for piano trio, five for string trio, and more than a dozen works for various combinations of wind instruments.

The three periods

Beethoven's career as a composer is conventionally divided into early, middle, and late periods. The "early" period is typically seen to last until 1802, the "middle" period from 1802 to 1812, and the "late" period thereafter. This distinction was first introduced in 1828, just one year after his death, and while often challenged and refined it remains a starting point to understand the development of Beethoven's work.[117]

Beethoven's early years in Bonn arguably represent a further, preliminary, period. His earliest known composition was from 1782, and a total of 40 pieces by him dating from 1792 or earlier are known today (though mainly from much later sources). Today his best-known works from before 1790 are three piano quartets and three piano sonatas, the quartets being closely modelled on Mozart's sonatas for piano and violin. From 1790 to 1802, his best music can be found in a cantata and a number of concert arias, and in some variations for solo piano, while his instrumental music (including movements of symphonies and a draft violin concerto, as well as various fragmentary chamber works) is conservative and uninspired.[n 9]

The conventional "first period" begins after Beethoven's arrival in Vienna in 1792. In the first few years he seems to have composed less than he did at Bonn, and his Piano Trios, op.1 were not published until 1795. From this point onward, he had mastered the 'Viennese style' (best known today from Haydn and Mozart) and was making the style his own. His works from 1795 to 1800 are larger in scale than was the norm (writing sonatas in four movements, not three, for instance); typically he uses a scherzo rather than a minuet and trio; and his music often includes dramatic, even sometimes over-the-top, uses of extreme dynamics and tempi and chromatic harmony. It was this that led Haydn to believe the third trio of Op.1 was too difficult for an audience to appreciate.[118]

He also explored new directions and gradually expanded the scope and ambition of his work. Some important pieces from the early period are the first and second symphonies, the set of six string quartets Opus 18, the first two piano concertos, and the first dozen or so piano sonatas, including the famous Pathétique sonata, Op. 13.

Middle period

His middle (heroic) period began shortly after the personal crisis brought on by his recognition of encroaching deafness. It includes large-scale works that express heroism and struggle. Middle-period works include six symphonies (Nos. 3–8), the last two piano concertos, the Triple Concerto and violin concerto, five string quartets (Nos. 7–11), several piano sonatas (including the Waldstein and Appassionata sonatas), the Kreutzer violin sonata and his only opera, Fidelio.

The "middle period" is sometimes associated with a "heroic" manner of composing,[119] but the use of the term "heroic" has become increasingly controversial in Beethoven scholarship. The term is more frequently used as an alternative name for the middle period.[120] The appropriateness of the term "heroic" to describe the whole middle period has been questioned as well: while some works, like the Third and Fifth Symphonies, are easy to describe as "heroic", many others, like his Symphony No. 6, Pastoral, are not.[121]

Late period

Beethoven's late period began in the decade 1810-1819. He began a renewed study of older music, including works by Johann Sebastian Bach and George Frideric Handel, that were then being published in the first attempts at complete editions. The overture The Consecration of the House (1822) was an early work to attempt to incorporate these influences. A new style emerged, now called his "late period". He returned to the keyboard to compose his first piano sonatas in almost a decade: the works of the late period include the last five piano sonatas and the Diabelli Variations, the last two sonatas for cello and piano, the late string quartets (see below), and two works for very large forces: the Missa Solemnis and the Ninth Symphony.[citation needed] Works from this period are characterised by their intellectual depth, their formal innovations, and their intense, highly personal expression. The String Quartet, Op. 131 has seven linked movements, and the Ninth Symphony adds choral forces to the orchestra in the last movement.[71] Other compositions from this period include the Missa solemnis, the last five string quartets (including the massive Große Fuge) and the last five piano sonatas.

He was attracted to the ideals of the Age of Enlightenment. In 1804, when Napoleon's imperial ambitions became clear, Beethoven took hold of the title page of his Third Symphony and scratched the name Bonaparte out so violently that he made a hole in the paper. He later changed the work's title to "Sinfonia Eroica, composta per festeggiare il sovvenire d'un grand'uom" ("Heroic Symphony, composed to celebrate the memory of a great man"), and he rededicated it to his patron, Prince Joseph Franz von Lobkowitz, at whose palace it was first performed.[122]

Legacy

The Beethoven Monument in Bonn was unveiled in August 1845, in honour of the 75th anniversary of his birth. It was the first statue of a composer created in Germany, and the music festival that accompanied the unveiling was the impetus for the very hasty construction of the original Beethovenhalle in Bonn (it was designed and built within less than a month, on the urging of Franz Liszt). A statue to Mozart had been unveiled in Salzburg, Austria, in 1842. Vienna did not honour Beethoven with a statue until 1880.[123] His is the only name inscribed on one of the plaques that trim Symphony Hall, Boston; the others were left empty because it was felt that only Beethoven's popularity would endure.[124]

There is a museum, the Beethoven House, the place of his birth, in central Bonn. The same city has hosted a musical festival, the Beethovenfest, since 1845. The festival was initially irregular but has been organised annually since 2007.

The Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies serves as a museum, research center, and host of lectures and performances devoted solely to this life and works.

The third largest crater on Mercury is named in his honour, as is the main-belt asteroid 1815 Beethoven.

See also

- Beethoven and his contemporaries

- Beethoven in film

- Catalogues of Beethoven compositions

- Death of Ludwig van Beethoven

References

Notes

- ^ The prefix van to the surname "Beethoven" reflects the Flemish origins of the family; the surname suggests that "at some stage they lived at or near a beet-farm".[1]

- ^ Most of Beethoven's early and works and those to which he did not give an opus number were listed by Georg Kinsky and Hans Halm as "WoO", works without opus number. Kin sky and Halm also listed 18 doubtful works in their appendix ("WoO Anhang"). In addition, some minor works not listed with opus numbers or in the WoO list have Hess catalogue numbers.[17]

- ^ It is uncertain whether this was the First or Second. Documentary evidence is unclear, and both concertos were in a similar state of near-completion (neither was completed or published for several years).[45]

- ^ The cause of Beethoven’s deafness has also variously been attributed to , amongst other possibilities, lead poisoning from Beethoven’s preferred wines[61], and Paget's disease of bone [62]

- ^ In 1824 Beethoven stood by the conductor Michael Umlauf during the premiere of his Ninth Symphony beating time (although Umlauf had warned the singers and orchestra to ignore him), and was not even aware of the applause which followed until he was turned to witness it.[67]

- ^ Solomon sets out his case in detail in his biography of Beethoven.[83]

- ^ Their ruling stated: "It ... appears from the statement of Ludwig van Beethoven [...] is unable to prove nobility: hence the matter of guardianship is transferred to the Magistrate[92]

- ^ "[It is now] abundantly clear that Schindler never possessed as many as c. 400 conversation books, and that he never destroyed roughly five-eighths of that number." [100]

- ^ GroveOnline, section 12, quote: "... a few rather colourless sonata movements... Less impressive, in these years, is the instrumental music in the sonata style. ... Where Beethoven departed from formula in these works he seems to have straggled helplessly, as in the violin concerto fragment. ... Beethoven at Bonn was a less interesting composer of works in the sonata style than of music in other genres ..."

Citations

- ^ Cooper 1996, p. 36.

- ^ Zelazko, Alikja. "10 Classical Music Composers to Know". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ "The 50 Greatest Composers of All Time". www.classical-music.com.

- ^ Smith, Brent (1927). "Ludwig van Beethoven". Proceedings of the Musical Association. 53: pp. 85-94.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Palmer, Willard A. (1996). First Sonatina Book: Alfred Masterwork Edition - Piano Sheet Music Collection. California: Alfred Publishing. p. 16.

- ^ Suchet, John. "Definitively the 20 greatest Beethoven works of all time". classicfm.com.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Tommatini, Anthony. "The Greatest". The New York Times.com.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ a b c d GroveOnline, section 1.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 407.

- ^ Swafford 2014, pp. 12–17.

- ^ a b Thayer 1967a, p. 50.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, p. 53.

- ^ a b Stanley 2000, p. 7.

- ^ Swafford 2014, pp. 22, 32.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, pp. 57–8.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 34.

- ^ Cooper 1996, p. 210.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, pp. 65–70.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, p. 69.

- ^ Cooper 1996, p. 50.

- ^ a b c GroveOnline, section 2.

- ^ Cooper 1996, p. 55.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, p. 121–122.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, p. 95.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 51.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, pp. 95–98.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, p. 96.

- ^ Cooper 2008, pp. 35–41.

- ^ Cooper 1996, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Swafford 2014, pp. 107–111.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 35.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 41.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, pp. 34–36.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 42.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 43.

- ^ GroveOnline, section 3.

- ^ Cooper 2008, pp. 47, 54.

- ^ Thayer 1921, p. 161.

- ^ Ronge 2013.

- ^ a b Cooper 2008, p. 53.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 59.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 46.

- ^ a b Cooper 2008, p. 59.

- ^ Lockwood 2005, p. 144.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 56.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 79.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 82.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 58.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 90.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 97.

- ^ Steblin 2009.

- ^ Cooper 2008, pp. 98–103.

- ^ Cooper 2008, pp. 112–27.

- ^ Cooper 2008, pp. 112–15.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 160.

- ^ Swafford 2014, pp. 223–24.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 108.

- ^ a b c GroveOnline, section 5.

- ^ Stevens 2013, pp. 2854–2858.

- ^ Oiseth 2015, pp. 139–47.

- ^ Cooper 1996, pp. 169–172.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 162.

- ^ Ealy 1994, p. 262.

- ^ Thayer 1967a, p. 577-578.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 351.

- ^ Ealy 1994, pp. 266–267.

- ^ Tyson 1969, p. 138-141.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 131.

- ^ a b c d e GroveOnline.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 148.

- ^ GroveOnline, sections 14 and 15.

- ^ Hoffmann 2003.

- ^ Cooper 2008, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Lockwood 2005, pp. 300–01.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 150.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 195.

- ^ Cooper 1996, p. 48.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 194.

- ^ Brandenburg 1996, p. 582.

- ^ Cooper 1996, p. 107.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 223–231.

- ^ Solomon, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Solomon, pp. 197–199.

- ^ Solomon, p. 196.

- ^ Solomon, pp. 231–239.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 284–285.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 282.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 301–302.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 302–303.

- ^ a b c Solomon 1998, p. 303.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 316-321.

- ^ Solomon 1998, pp. 3364–365.

- ^ Lockwood 2005, p. 278.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 254.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 260.

- ^ Solomon 1998, p. 360.

- ^ Clive 2001, p. 239.

- ^ Albrecht 2009, p. 181.

- ^ Hammelmann 1965, p. 187.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 317.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 318.

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 213.

- ^ Winter 1994, p. 245.

- ^ Tom Service. "Riccardo Chailly on Beethoven: 'It's a long way from the First to the Ninth'", The Guardian, 26 October 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2014

- ^ John Suchet. "Karl van Beethoven (1806–58) Beethoven's nephew". Classic FM. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ a b Cooper 2008, pp. 318, 349.

- ^ SaccentiSmildeSaris 2011.

- ^ SaccentiSmildeSaris 2012.

- ^ Jovanovic, Dragana (3 July 2012). "Teeth Thief Hits Graves of Great Composers". ABC. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ^ Mai (2006)

- ^ Meredith 2005, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Eisinger (2008)

- ^ Lorenz (2007)

- ^ "Golden Record Music List". NASA. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ GroveOnline, section 11.

- ^ GroveOnline, section 13.

- ^ Solomon, Maynard (1990). Beethoven essays. Harvard University Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-674-06379-2. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ Steinberg, Michael P. (2006). Listening to reason: culture, subjectivity, and nineteenth-century music. Princeton University Press. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-0-691-12616-6. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ Burnham, Scott G.; Steinberg, Michael P. (2000). Beethoven and his world. Princeton University Press. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-0-691-07073-5. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ "Friedrich Oelenhainz (1745–1804), Franz Joseph Maximilian Fürst von Lobkowitz (1772–1816)]". Beethoven-Haus Bonn. April 2002. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ^ Comini, Alessandra (2008). Alessandra Comini, The Changing Image of Beethoven: A Study in Mythmaking. ISBN 978-0-86534-661-1. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- ^ "The History of Symphony Hall".

Sources

- Albrecht, Theodore (2009). "Anton Schindler as destroyer and forger of Beethoven's conversation books: A case for decriminalization" (PDF). In Blažeković, Zdravko (ed.). Music's intellectual history. New York: RILM. pp. 169–181. ISBN 978-1-932765-05-2.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brandenburg, Sieghard, ed. (1996). Ludwig van Beethoven: Briefwechsel. Gesamtausgabe. Munich: Henle.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Clive, H.P. (2001). Beethoven and His World: A Biographical Dictionary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816672-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cooper, Barry, ed. (1996). The Beethoven Companion (revised ed.). Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-50-027871-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cooper, Barry (2008). Beethoven. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 978-0-19-531331-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ealy, George Thomas (Spring 1994). "Of Ear Trumpets and a Resonance Plate: Early Hearing Aids and Beethoven's Hearing Perception". 19th-Century Music. 17 (3): 262–73. doi:10.1525/ncm.1994.17.3.02a00050. JSTOR 746569.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Eisinger, Josef (2008). "The lead in Beethoven's hair". Toxicological & Environmental Chemistry. 90: 1–5. doi:10.1080/02772240701630588.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hammelmann, Han (March 1965). "Beethoven's Conversation Books". The Musical Times. 106 (1465): 187–189. doi:10.2307/948240. JSTOR 948240.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Haberl, Dieter (2006). "Beethovens erste Reise nach Wien – Die Datierung seiner Schulreise zu W.A. Mozart". Neues Musikwissenschaftliches Jahrbuch. 14: 215–255.

- Hoffmann, E. T. A. (2003). E. T. A. Hoffmann's musical writings : Kreisleriana, The poet and the composer, music criticism. ISBN 978-0-521-54339-2. OCLC 1050939426.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kerman, Joseph; Tyson, Alan; Burnham, Scott G.; et al. (2001). "Ludwig van Beethoven". Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- Lockwood, Lewis (17 January 2005). Beethoven: The Music and the Life. W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-32638-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lorenz, Michael (Winter 2007). "Commentary on Wawruch's Report: Biographies of Andreas Wawruch and Johann Seibert, Schindler's Responses to Wawruch's Report, and Beethoven's Medical Condition and Alcohol Consumption". The Beethoven Journal. 22 (2): 92–100.

- Mai, FM (2006). "Beethoven's terminal illness and death". The Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. 36 (3): 258–63. PMID 17214130.

- Meredith, William Rhea (2005). "The History of Beethoven's Skull Fragments". Beethoven Journal. 20 (1–2): 3–46. OCLC 64392567.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Morris, Edmund (2010). Beethoven: The Universal Composer. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-075975-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Oiseth, Stanley J (27 October 2015). "Beethoven's autopsy revisited: A pathologist sounds a final note". Journal of Medical Biography. 25 (3): 139–147. doi:10.1177/0967772015575883. PMID 26508624.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Ronge, Julia (2013). "Beethoven's Studies with Joseph Haydn (With a Postscript on the Length of Beethoven's Bonn Employment". Beethoven Journal. 28 (1): 4–25.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Saccenti, Edoardo; Smilde, Age K; Saris, Wim H M (2011). "Beethoven's deafness and his three styles". BMJ. 343: d7589. doi:10.1136/bmj.d7589. PMID 22187391.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Saccenti, Edoardo; Smilde, Age K; Saris, Wim H M (2012). "Beethoven's deafness and his three styles". BMJ. 344: e512. doi:10.1136/bmj.e512.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Solomon, Maynard (November 1998). Beethoven (2nd revised ed.). New York: Schirmer Trade Books. ISBN 978-0-8256-7268-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stanley, Glenn, ed. (2000). The Cambridge Companion to Beethoven. doi:10.1017/ccol9780521580748. ISBN 978-0-521-58074-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Steblin, Rita (2009). "'A dear, enchanting girl who loves me and whom I love': New Facts about Beethoven's Beloved Piano Pupil Julie Guicciardi". Bonner Beethoven-Studien. 8: 89–152.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stevens, Michael; et al. (November 2013). "Lead and the Deafness of Ludwig Van Beethoven". Laryngoscope. 123 (11): 2854–2858. doi:10.1002/lary.24120. PMID 23686526.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Swafford, Jan (2014). Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-31255-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thayer, A. W. (1921). Krehbiel, Henry Edward (ed.). The Life of Ludwig Van Beethoven, Vol 1. The Beethoven Association. OCLC 422583.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thayer, Alexander Wheelock (1967a). Forbes, Elliot (ed.). Thayer's Life of Beethoven. Vol. 1. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02717-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thayer, Alexander Wheelock (1967b). Forbes, Elliot (ed.). Thayer's Life of Beethoven. Vol. 2. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02718-0.

- Tyson, Alan (February 1969). "Beethoven's Heroic Phase". Musical Times. 110 (1512): 139–141. JSTOR 952790.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Winter, Robert (1994). The Beethoven Quartet Companion. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20420-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Ludwig van Beethoven at the Musopen project

- Ludwig van Beethoven at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Beethoven-Haus Bonn

- Free scores by Ludwig van Beethoven at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Free scores by Ludwig van Beethoven in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- The Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies, The Beethoven Gateway (San José State University)

- "Discovering Beethoven". BBC Radio 3.

- Works by Ludwig van Beethoven at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Ludwig van Beethoven at Internet Archive

- Works by Ludwig van Beethoven at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)