| Inner German border | |

|---|---|

| North and central Germany | |

| |

| Type | Border fortification system |

| Height | Up to 4 metres (13 ft) |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | German Democratic Republic, Federal Republic of Germany |

| Condition | Mostly demolished |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1945 |

| Built by | German Democratic Republic |

| In use | 1945–1990 |

| Materials | Steel, concrete |

| Demolished | 1990 |

| Battles/wars | Cold War |

| Garrison information | |

| Garrison | National People's Army, Stasi (East); Bundesgrenzschutz, Bayerische Grenzpolizei, Bundeszollverwaltung, US Army, British Frontier Service (West) |

The inner German border (German: Innerdeutsche Grenze or deutsch-deutsche Grenze, informally Zonengrenze) was the frontier between the German Democratic Republic (GDR, East Germany) and the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG, West Germany) between 1945 and 1990. It was 1,381 kilometres (858 mi) long, reaching from the Baltic Sea to the border of Czechoslovakia. Formally established on 1 July 1945, the border originally marked the boundary between the Western and Soviet occupation zones of Germany. It became the most heavily fortified frontier in the world, defined by a continuous line of high metal fences and walls, barbed wire, electrified alarms, trenches, watchtowers, automatic booby-traps and minefields. It was guarded around the clock by 50,000 armed East German border guards who faced tens of thousands of West German, British and US border guards and soldiers on the other side.[1] Over a million NATO and Warsaw Pact troops were stationed further back, constantly alert for an invasion that ultimately never came.

The border was a physical manifestation of Winston Churchill's metaphor of an Iron Curtain separating the Soviet and Western blocs during the Cold War. It marked the boundary between the two ideological systems – capitalist and communist, democratic and totalitarian. Built in phases from 1952 to the late 1980s,[2] the border fortifications were constructed by East Germany in response to the ever-increasing numbers of its citizens fleeing to the West.[3] The inner German border caused widespread economic and social disruption on both sides, with East Germans living in the border region suffering especially draconian restrictions. Around 1,000 people died trying to cross the border during its 45-year existence.[4]

The internationally more famous Berlin Wall was a physically separate, less elaborate and much shorter border system surrounding the enclave of West Berlin, more than 170 kilometres (110 mi) to the east of the inner German border. The day after the Berlin Wall fell on 9 November 1989, the inner German border was also opened and millions of East Germans poured into the West. The inner German border was not finally abandoned until 1 July 1990[5] – exactly 45 years to the day since it was established – only three months before German reunification formally ended the division of Germany.

Today, relatively little remains of the inner German border. The route of the border has been declared part of a "European Green Belt" along the course of the old Iron Curtain stretching from the Arctic Circle to the Black Sea, linking various national parks and nature reserves. Numerous museums and memorials along the old border commemorate the division and reunification of Germany and, in some places, preserve elements of the border fortifications.[6]

Origins of the border

The inner German border owed its origins to the agreements reached at the Tehran Conference in November–December 1943. The conference established the European Advisory Commission (EAC) to outline proposals for the partition of a defeated Germany into British, American and Soviet occupation zones (a French occupation zone was established later).[7] At the time, Germany was divided into a series of gaue – Nazi administrative subdivisions – which had succeeded the administrative divisions of Weimar Germany. These had in turn replaced the earlier duchies and kingdoms of the German Empire and pre-unification Germany.[8]

The demarcation line was based on a British proposal of 15 January 1944 which was devised by a special committee of the British Cabinet. It envisaged a line of control along the borders of the old states or provinces of Mecklenburg, Saxony, Anhalt and Thuringia, which had ceased to exist as separate entities when the Prussians unified Germany in 1871.[9] Additional minor adjustments were made for practical reasons.[7] The British would occupy the north-west of Germany, the United States would occupy the south and the Soviet Union would occupy the east. Berlin was to be treated as a separate joint zone of occupation, deep inside the Soviet zone. The rationale behind this arrangement was that it would give the Soviets a powerful incentive to see the war through to the end. It would give the British an occupation zone that was physically close to the UK and on the coast, making it easier to resupply it from the UK. It was also hoped that decentralising forces in Germany would be promoted by reviving traditional provincial boundaries. The old domination of Prussia would be undermined through "the revival of loyalties to States and Provinces with certain natural internal boundaries dictated by geography, history and economic considerations ... An anti-Prussian bias may well develop in certain areas, and there are strong grounds for weakening the present preponderance of Prussia."[10]

The United States envisaged a very different division of Germany. The US put forward a proposal with a large American zone in the north, a smaller zone for the Soviets in the east – with the American and Soviet zones meeting at Berlin – and another smaller zone for the British in the south. President Franklin D. Roosevelt disliked the idea of a US occupation zone in the south, as its supply routes would be dependent on access through France, which it was feared would be unstable following its liberation. To forestall expected American objections, the British proposal was presented directly to the EAC without prior agreement with the Americans. The Russians immediately accepted the proposal and left the United States with little choice but to accept as well. The final division of Germany was thus mainly along the lines of the British proposal, with the Americans being given the North Sea port-cities of Bremen and Bremerhaven as an enclave within the British zone to ease President Roosevelt's concerns about supply routes.[11]

The division of Germany went into effect on 1 July 1945. Because of the unexpectedly rapid Allied advance in central Germany in the final weeks of the war, British and American troops occupied large areas of territory that were assigned to the Soviet zones of occupation. These included a broad area of what was to become the western parts of East Germany, as well as parts of Czechoslovakia and Austria. The redeployment of Western troops at the start of July 1945 was an unpleasant surprise for many German refugees, who had fled west to escape the Russian advance. A fresh wave of refugees headed further west as the Americans and British withdrew and Soviet troops entered the areas allocated to the Soviet occupation zone.[12]

It was originally intended that post-war Germany would be governed jointly by the Allies. Following Germany's unconditional surrender in May 1945, the Allied Control Council (ACC) was formed under the terms of the Declaration on the Defeat of Germany, signed in Berlin on 5 June 1945. The council was "the highest authority for matters concerning the whole of Germany". Each of the four powers – France, the UK, the US and the USSR – were represented by their supreme commanders in Germany. The council operated from 30 August 1945 until it was suspended on 20 March 1948.[13] By the time of its demise, cooperation between the Western Allies and the Soviets had broken down completely over the issue of Germany's political and economic future. In May 1949 the three western occupation zones were merged to form the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), a democratically governed federal state with a free market economy. The Soviets responded in October 1949 with the establishment of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), a highly centralised communist dictatorship organised on Stalinist lines.[14] The former demarcation lines between the western and eastern zones had now become a de facto international frontier – the inner German border.

From the outset, West Germany did not accept the legitimacy of East Germany. The Basic Law (constitution) of West Germany set out the principle (known as the Alleinvertretungsanspruch, or "claim of sole representation") that the Federal Republic of Germany was the single and only legitimate representative of the German people and of their national will. According to Article 1 of the Basic Law, "Germany is an indivisible democratic republic, composed of German states ... There is only one German citizenship."[15] Under this interpretation, the East German government was for many years regarded by the West German government as an illegal organisation intent on depriving Germans of their constitutional rights. It had not been freely or fairly elected, and the creation of East Germany itself was a fait accompli by the East German Communists and their Soviet allies. Acts by other countries that lent legitimacy to East Germany and strengthened the division of Germany were strongly resisted. The government of West Germany's first chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, applied what became known as the Hallstein Doctrine: "The Federal Republic will view the establishment of diplomatic relations with the so-called German Democratic Republic by third parties as an unfriendly act tending to aggravate the division of Germany", as Adenauer put it in 1955. Until the late 1960s, the West German government would only maintain diplomatic relations with countries that did not recognise East Germany, and severed relations with countries that did so, including Yugoslavia in 1957 and Cuba in 1963.[16][17] By 1963 West Germany had 87 embassies around the world while the GDR had only thirteen, including the Soviet Union and the other Warsaw Pact countries plus such other Communist states as North Korea and Vietnam.[18]

The principle of sole representation had important consequences for the inner German border. West Germany regarded German citizenship and rights as unitary, applying equally to East and West German citizens alike. An East German who escaped or was released to the West automatically entered into full enjoyment of those rights, including West German citizenship and social benefits.[17] A would-be immigrant from another country who could get to East Germany could not be barred from entering West Germany across the internal border, which had great significance in later decades. West German laws were deemed to be applicable in the East; violations of human rights in East Germany could be prosecuted in the West. East Germans thus had a powerful incentive to move to the West, where they would enjoy greater freedoms as well as improved economic prospects. The East German government had an equally important incentive – indeed, a political imperative – to define the country as a legitimate state in its own right, not merely the "Soviet occupation zone" (sowjetische Besatzungszone) as West Germany referred to it.[19] In the terminology of the GDR's rulers, West Germany was enemy territory (feindliches Ausland). It was portrayed as a capitalist, semi-fascist state that exploited its citizens, sought to regain the lost territories of the Third Reich and stood opposed to the peaceful socialism of the GDR.[20]

Development of the border

1945 to 1952: the "Green Border"

In the early days of the occupation, the Allies maintained controls on so-called "interzonal traffic" between all the zones of Germany, as well as controlling Germany's international frontiers. The aim was to manage the flow of refugees and prevent the escape of wanted persons such as former Nazi officials and intelligence officers.[21] Travel restrictions in the western zones were gradually lifted as the western German economy was revived by the Allies. In the Soviet zone, however, the poverty and lack of personal freedom led to huge numbers of eastern Germans emigrating to western Germany. Between October 1945 and June 1946, 1.6 million Germans left the Soviet zone and moved to the west.[22] In response, the Soviets persuaded the Allied Control Council to close all zonal borders on 30 June 1946. A system of interzonal passes was introduced to restrict traffic between the zones.[23]

The interzonal and international borders were initially controlled directly by the Allied militaries. The pre-war Grenzpolizei (German national border police service) had been abolished because of its wartime takeover by the Nazis and infiltration by the SS.[24] The situation was initially somewhat anarchic immediately after the war, with large numbers of refugees still in transit. There were a number of incidents of both Soviet and American troops mounting unauthorised expeditions into each others' zones to loot and kidnap, as well as unauthorised shooting across the boundary line.[25] It became apparent that the armies of the Western Allies by themselves could not effectively seal off the borders and interzonal boundaries. From the spring of 1946, newly trained German police forces under the control of the individual German states took on the task of patrolling the borders alongside Allied troops.[26]

The east-west interzonal border became steadily more tense as the relationship between the Western Allies and the Soviets broke down. Whereas early incidents of Soviet incursions across the line could be attributed to "outlaw" elements, the Soviets now began to actively promote the infiltration of spies and the smuggling of black-market goods across the interzonal border.[27] They also encouraged the emigration to the West of numerous unwanted German refugees, to rid them of the burden of supporting such individuals. By late August 1947, over 5,000 illegal border crossers were being detained by US forces each week. However, an increasing number of the crossers were of economic value to the Soviets. From September 1947 an increasingly strict control regime was imposed on the eastern boundary. The number of Soviet soldiers on the boundary was increased and they were supplemented with border guards from the newly established East German Volkspolizei ("People's Police").[28]

The West Germans likewise stepped up border security at the start of the 1950s. On 2 March 1951 the West German government authorised the establishment of a federal frontier protection authority, initially composed of 10,000 men organised as the Bundesgrenzschutz or BGS (Federal Border Guard).[29] Their numbers were raised to 20,000 a few months later.[30] The BGS was constituted as a highly mobile, lightly armed force tasked with guarding the borders and capable of combating internal threats constituting a national emergency. It became operational on 15 February 1952, supporting the local border police in handling routine border control problems such as illegal crossings of a nonmilitary nature.[30] Allied troops (the British in the north, the Americans in the south) retained responsibility for the military security of the border. They could take operational control of the local border police and the BGS in a military emergency.[31]

The boundary line was nonetheless still fairly easy to cross. Local inhabitants could cross the line to maintain fields on the other side, or even to live on one side and work on the other. Those who were unable to obtain passes could usually bribe the border guards or sneak across at various points. Refugees from the east, who were often Germans expelled from other countries in central and eastern Europe, were guided across the boundary by villagers in exchange for hefty fees. Other locals smuggled goods from east to west and vice versa to supplement their often meagre incomes.[32] The number of border migrants remained high despite the increase in East German security measures, with 675,000 people fleeing to West Germany between 1949 and 1952.[33] In one incident in 1950 that demonstrated the porosity of the border at this time, an entire circus, consisting of 90 wagons with 35 horses and sundry elephants, tigers and monkeys, was able to cross the border secretly without being detected by patrols.[34]

There were major differences in the way that the Western and Eastern sides tackled illegal border crossings. Because the GDR did not at this stage officially regard the inner German border as a "state border", those who were caught while trying to cross it illegally could not be punished under passport control legislation; instead, they were to be punished for crimes against the economy, principally sabotage.[35] The Western side did not attempt to stop people crossing from the east, but faced the challenge of keeping Soviet and East German military personnel and spies out. US and West German border patrollers were authorised to use reasonable force, including firearms, if they came across soldiers crossing from the other side who were attempting to flee or resist arrest. Civilians, on the other hand, would merely be kept under surveillance until they could be picked up by the West German border guards or police.[36]

1952 to 1967: the "Special Regime"

The border remained largely unfortified for several years after the East and West German republics were established in 1949, although by this time the East Germans had already blocked many unofficial crossing points with ditches and barricades. This changed abruptly on 26 May 1952 when the GDR Council of Ministers ordered the implementation of a "special regime on the demarcation line" in what the GDR Prime Minister Otto Grotewohl justified as a measure to keep out the "spies, diversionists, terrorists and smugglers" who were allegedly being sent across the border in ever-increasing numbers.[37] In reality, though, the decision to fortify the border had been taken some time earlier. East Germany was haemorrhaging citizens at the rate of 10,000-20,000 a month, many of them from the skilled, educated and professional classes. The exodus threatened the viability of East Germany's already beleaguered economy.[38] The Soviets were as alarmed by the problem as their East German protegés. On 1 April 1952, members of the East German leadership met the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in Moscow. Stalin's foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov proposed that the East Germans should "introduce a system of passes for visits of West Berlin residents to the territory of East Berlin [so as to stop] free movement of Western agents" in the GDR. Stalin agreed, calling the situation "intolerable". He advised the East Germans to build up their border defences, telling them: "The demarcation line between East and West Germany should be considered a border – and not just any border, but a dangerous one ... The Germans will guard the first line of defence, and we will put Russian troops on the second line." [39]

The introduction of the "special regime" was carried out as abruptly as the construction of the Berlin Wall nine years later. A ploughed 10 m (30 ft) strip was created along the entire length of the inner German border. An adjoining 500 m (1,500 ft) wide "protective strip" (Schutzstreifen) was placed under severe restrictions and a further 5 km (3 mile) wide "restricted zone" (Sperrzone) was created in which only those holding a special permit could live or work. Trees and brush were cut down along the border to clear lines of sight for the border guards and eliminate cover for would-be border crossers. Houses adjoining the border were torn down, bridges were closed and barbed-wire fencing was put up in many places. Tight restrictions were placed on farming, with fields along the border being worked only in daylight hours and under the watch of armed border guards. The guards were authorised to use "weapons ... in case of failure to observe the orders of border patrols".[37]

The sudden closure of the border caused acute disruption for communities on both sides. As it had previously been merely an administrative boundary, homes, businesses, industrial sites and municipal amenities had been constructed straddling the border. They were now literally split down the middle. In Oebisfelde, the residents found that they could no longer access the shallow end of their swimming pool; in Buddenstedt, the border ran just behind the goal posts of a football field, putting the goalkeeper at risk of being shot by the border guards. An open-cast coal mine at Schöningen was split in half, causing Western and Eastern engineers to engage in a race to cart away equipment before the other side could seize it. Workers on both sides found themselves cut off from their homes and jobs. Farmers with land on the other side of the border effectively lost it, as they could no longer reach it.[40] In Philippsthal, a house containing a printing shop was split in two by the border, which ran through the middle of the building. The doors leading to the East German portion of the building were bricked up and blocked until 1976.[41] The disruption on the eastern side of the border was, however, far worse. Some 8,369 civilians living in the Sperrgebiet were forcibly resettled by the East German government in a programme codenamed "Operation Vermin" (Aktion Ungeziefer). Those expelled included foreigners, people who were not registered with the police, convicted criminals and "people who because of their position in or toward society pose a threat to the antifascist, democratic order."[42] Another 3,000 residents, realising that they were about to be expelled from their homes, fled to the West.[33] By the end of 1952 the inner German border was virtually sealed.

The border between East and West Berlin was also significantly tightened, although it was not fully closed at this stage. By the end of September 1952, about 200 of the 277 streets which ran from the Western sectors to the East were closed to traffic and the remainder were subjected to constant police observation. Railway traffic was routed around the Western sectors and all workers and employees of nationalised factories had to pledge not to visit West Berlin; if they did so, they would be fired. Even with these restrictions, however, the border in Berlin remained considerably more accessible than the main inner German border. Berlin consequently became the main route by which East Germans left for the West.[43] The outflow of people remained considerable. Between 1949 and the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961, an estimated 3.5 million East Germans – one-sixth of East Germany's entire population – emigrated to the West. After 1952, the majority left via West Berlin. Events such as the crushing of the 1953 uprising and the shortages caused by the introduction of collectivisation resulted in major increases in refugee numbers, swamping West Berlin with fleeing easterners.[43]

A further expansion of the border regime occurred in July 1962 when the entire Baltic coast of East Germany was made a border zone. A 500-metre (1,600 ft) wide strip on the eastern side of the Bay of Mecklenburg was added to the tightly controlled protective strip, while strict limits were put on a variety of coastal activities that could be useful to would-be escapees. The use and movement of boats was restricted – for instance, not allowing their use during the night – and camping and accommodating visitors in the coastal zone required official permission.[44]

1967 to 1989: The "Modern Frontier"

Towards the end of the 1960s, the East German government decided to upgrade the border to establish what East German leader Walter Ulbricht termed the "modern frontier" (die moderne Grenze). The redeveloped border system took advantage of the knowledge that had been obtained in building and maintaining the Berlin Wall. Many of the lessons from Berlin were transferred to the inner German border, where the border defences were systematically upgraded to make it far harder to cross successfully. Barbed wire fences were replaced with harder-to-climb steel mesh. Directional anti-personnel mines and anti-vehicle ditches were introduced to block the movement of people and vehicles. Tripwires and electric signals were introduced to make it easier for the border guards to detect escapees. All-weather patrol roads were built to enable rapid access to any point along the border and wooden guard towers were replaced with prefabricated concrete towers and observation bunkers. The changes were intended to make the border far more secure as well as enabling manpower to be used more effectively.[45] The East Germans also hoped to make the border system less intrusive to reduce its negative psychological impact on Western public opinion.[46]

Construction of the new border system started in September 1967. The first phase of the upgrading programme, from 1967 to 1972, was initially seen as a strengthening of weak points in the existing system but from then onwards it became a general rolling programme of work along the entire length of the border.[47] Nearly 1,300 km of new fencing was built, usually further back from the geographical border line than the old barbed wire fences had been.[45] The entire system was expected to be completed by 1975 but delays resulted in the modernisation programme continuing well into the 1980s.[48] The new border system had an immediate effect in reducing the number of escapes. During the mid-1960s, an average of about 1,000 people a year had made it across the border. Ten years later, that figure had fallen to about 120 per year.[49]

At the same time, tensions between the two Germanies eased with the inauguration of West German Chancellor Willy Brandt's Ostpolitik. The Brandt government sought to normalise relations between West Germany and its eastern neighbours, and produced a series of treaties and agreements. Most significantly, on 21 December 1972 the two Germanies signed a "Treaty on the Basis of Relations between the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic". East and West Germany agreed to recognise each other's sovereignty and support each other's applications for UN membership (achieved in September 1973). Reunification remained a theoretical objective for West Germany, but in practice the issue was put to one side by the West and was abandoned entirely by the East.[50] East German's international isolation was rapidly ended, with the number of countries recognising the GDR rising from thirteen in 1962 to 115 by 1975.[51]

The agreement had significant implications for the border. The two Germanies established a border commission (Grenzkommission) which met from 1973 to the mid-1980s to resolve practical problems arising from the existence of the border. One early key task was to survey and agree on a definitive border line, as the existing line was somewhat imprecise. Boundary stones and poles were installed to mark the agreed-upon line. Its work was largely completed by 1983, though it was unable to resolve the persistent problem of what to do about the Elbe river. The West Germans considered the border to run along the East German bank of the river, while the East Germans regarded the river's middle point or Thalweg to be the border line.[52] This led to a number of clashes, some of which came close to armed conflict.[53] The normalisation of relations between East and West Germany also led to a degree of relaxation in the border controls, although the border fortifications were as rigorously maintained as ever.[54]

In 1988, the increasingly unsustainable costs of maintaining the border installations led the GDR leadership to propose replacing them with a high-technology system codenamed Grenze 2000. Drawing on technology which the Red Army had deployed in Afghanistan during the Soviet-Afghan War, it would have replaced the border fences with a network of signal tripwires, seismic detectors to detect footsteps, infrared beams, microwave detectors and other electronic sensors. It was never implemented, not least because of the high costs of construction, which were estimated at 257 million East German marks.[55][56]

The impact of the border

Economic and social impact

The closure of the border had a substantial economic and social impact on both East and West Germany. Cross-border transport links were largely severed; ten main railway lines, 24 secondary lines, 23 autobahns or national roads, 140 regional roads and thousands of smaller roads, paths and waterways were blocked or otherwise interrupted. The tightest level of closure came in 1966, by which time only six railway lines were left open along with three autobahns, one regional road and two waterways. When relations between the two Germanies eased in the 1970s, the East Germans agreed to open up more crossing points in exchange for economic assistance. Telephone and mail communications remained open throughout, although packages and letters sent through the mail were routinely opened and telephone calls were monitored.[7]

The economic impact of the border's effective closure was severe. Many towns and villages were severed from their markets and economic hinterlands. The border areas became significantly poorer and less economically healthy than localities located further away. The two German states responded to the problem in different ways. West Germany gave substantial subsidies to border communities under the "aid to border regions" (Zonenrandförderung) programme, an initiative begun in 1971 to save the border area from total decline. Special aid was given to communities and districts if more than 50% of their area, or 50% of their population, was located within 40 kilometres (25 mi) of the inner German border, the Czechoslovak border or the Baltic coast. Infrastructure and businesses along the border benefited from substantial state investment. Many border communities were thereby saved from total decline.[57]

East Germany's border towns had a much harder time, partly because their country was poorer to begin with but also because of the much harsher restrictions imposed on the border areas by the GDR government. Industry withered in many districts, with agriculture becoming the largest employer. In the northern district of Nordwestmecklenburg, for instance, over 42% of the working population was employed in agriculture by 1989.[58] The border region was progressively depopulated though the clearance of numerous villages and the forcible relocation of border inhabitants. Towns along the border suffered draconian building restrictions; inhabitants were forbidden not only to build new houses but were not allowed to repair existing ones, causing communities to fall into severe decay.[59] The state did nothing to improve the border economy or infrastructure. On the other hand, it did provide some compensation for those remaining in the border zone. A 15% income supplement was given to those living in the Sperrzone and Schutzstreifen, though this did not halt the shrinkage of the border population as younger people moved elsewhere to find employment and better living conditions.[57]

The creation of the border zone and the building and maintenance of its fortifications had a very substantial cost for the East German state. The border zone occupied a great deal of land, taking up around 6,900 square kilometres (2,700 sq mi) (over six per cent) of East German territory [60]. In nominal terms this was slightly larger than the US state of Connecticut or about the same size as the British county of Lincolnshire, but as a proportion of East Germany's land area it was equivalent to around the size of Texas or two-thirds the size of Wales. Within this area, normal economic activities were severely curtailed or ceased entirely in some areas where residents were forced to leave. The actual cost of the border system was such a closely guarded secret that even today it is still uncertain exactly how much it cost to build and maintain. The cost of some individual elements is known; for instance, the BT-9 watchtowers each cost around 65,000 East German marks to build and the expanded metal fences cost around 151,800 marks per kilometre. The implementation of the "modern frontier" in the 1970s led to a major increase in personnel costs. Figures for the total annual expenditure on GDR border troops show a rise from 600 million marks per annum in 1970 to nearly 1 billion by 1983. In early 1989, East German economists sought to assess the cost-effectiveness of the border by dividing the cost of the border by the number of arrests. They found that the border was grossly inefficient from a financial perspective. Each arrest cost 2.1 million marks, while the average value of each working person was only 700,000. In other words, the average cost of an arrest was nearly three times the value of the prisoner.[61]

Views of the border

The West and East German governments promoted very different views of the border. The GDR's official name for the border was the Staatsgrenze der DDR zur Bundesrepublik Deutschland und West-Berlin ("state border between the GDR and the Federal Republic of Germany and West Berlin")[62] As the name indicates, the border was seen by the GDR as a bona fide international frontier of a sovereign state. The East German government presented border as a defensive rampart against Western aggression. In Grenzer ("Border Guard"), a 1981 propaganda film made by the East German Army, NATO and West German troops and tanks are depicted as ruthless militarists advancing towards East Germany. The "imperialist" West Germans are accused of pursuing "revanchism as a state doctrine" and seeking to reclaim not only East Germany but also the "Eastern Territories", the former German lands annexed by Poland and Russia in 1945. The border is described as "the dividing line between socialism and imperialism". Grenztruppen interviewed in the film speak of the rightness of their cause and the threat of Western agents, spies and provocateurs. The role played by the Grenztruppen in protecting the state is emphasised with songs such as "This state is our life, we stand for it with our lives". Grenztruppen killed on the border are hailed as heroes and their memorial in East Berlin is saluted by schoolchildren.[63][64]

For many years, the West German government's policy of regarding East Germany as an illegitimate Soviet-controlled entity led to it rejecting East Germany's claims to international legitimacy. Whereas the GDR referred to "the state border", West Germany called it merely the "demarcation line" (Demarkationslinie) of the "Soviet occupation zone" (Sowjetische Besatzungszone). The government's public statements emphasised the cruelty and injustice of the division of Germany. Signs along the Western side of the frontier declared "Hier ist Deutschland noch geteilt – Auch drüben ist Deutschland!" ("Here Germany is still divided – Germany is over there, too!"). The official view was put succinctly in a leaflet distributed to Western visitors to the border zone in the 1960s:

An echelonned system of barbed wire fences, wire entanglements, mines, observation posts and prohibited zones divides both men and women of our people more poignantly than oceans, mountains and state frontiers could do. Behind these fortifications there live Germans like ourselves. They, too, want human rights and freedom. Yet informers, fanatics and misguided persons together with a draconic system of justice see to it that they cannot take advantage of these basic rights. Do not let us forget: Germany is over there, too![65]

Whereas civilians were kept well away from the border by the East German government, the West Germans actively encouraged border tourism. The border itself became a popular theme for postage cards, while locations where the border was especially intrusive became tourist attractions. One such example was the divided village of Mödlareuth in Bavaria. The Associated Press reported in 1976 that "Western tourists by the busload come out to have their pictures taken against the backdrop of the latest Communist walled city [sic]. Several cars of sightseers pulled up while we were there; some even stopped to have a family picnic in view of the concrete blockhouse and the bunker-slits protruding from the green hillock where a collective's cows were grazing."[49] Facilities were built to permit the tourists to view the border zone. At Zimmerau in Bavaria, for instance, a 38-metre (125 ft) observation tower (the Bayernturm) was constructed in 1966 to give visitors a view across the hills into East Germany.[66] The inhabitants of the East German village of Kella found themselves becoming a tourist attraction for Westerners in the 1970s and 1980s. A viewing point, the "Window on Kella", was established on a nearby hilltop. Tourists could peer across the border with binoculars and telescopes, and could enjoy a meal at a restaurant overlooking the border zone.[67] Perhaps most surreally, a nudist beach was opened on the Western side in 1975 immediately adjoining the border's terminus near the Baltic Sea port of Travemünde. Visitors often sought to have a nude photograph taken below a looming East German watchtower, though the West Germans noted "a lot more movement on that watchtower since the nudist beach opened."[68][69]

Fortifications on the border

Overview

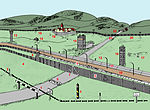

The eastern side of the inner German border was dominated by a complex system of interlocking fortifications and security zones over 1,300 kilometres (810 mi) long and several kilometres deep. The outer fences and walls were the most familiar and visible aspect of the system for Western visitors to the border zone, but they were merely the final obstacle for a would-be escapee. The complexity of the border system increased steadily until it reached its full extent in the early 1980s. The following description and the accompanying diagram describe the border as it was around 1980.

Travelling notionally from east to west[70], an escapee would first reach the edge of the to the restricted zone (Sperrzone), a closely controlled 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) wide strip of land parallel with the border. If he made it past the patrols and watchful inhabitants he would have reached the first of the border fences, the signal fence (Signalzaun) situated around 500 to 1,000 metres (1,600 to 3,300 ft) from the actual border. Climbing or cutting the barbed wire running along the top and side of the fence would cause audible, flashing or silent alarms to be activated to alert the border guards.

Beyond the signal fence was the "protective strip" (Schutzstreifen). It was brightly lit by floodlights in many places to reduce an escapee's chances of using the cover of darkness. Guard towers, bunkers and dog runs were positioned at frequent intervals to keep a round-the-clock watch on the strip. An escapee would next reach the floodlit control strip, often called the "death strip" in the West. Tripwire-activated flare launchers were situated at various points to help the border guards to pinpoint the location of an escape. The last and most formidable obstacle was the outer fence(s). In some places there were multiple parallel rows of fencing, each up to several metres high, with minefields in between. The fences were not electrified but were booby-trapped with directional anti-personnel mines at 10 metres (33 ft) intervals, each one of which was capable of killing at a range of up to 120 metres (390 ft). Finally, the escapee had to cross whatever natural obstacles were on the western side of the border as well as traversing a strip of cleared ground that was up to 500 metres (1,600 ft) wide. While crossing this outer strip, he would appear in clear view and shooting range of the border guards before reaching the safety of West German territory.

Restricted zone

The Sperrzone, a 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) wide area to which access was heavily restricted, was the rear segment of the border defences. When it was established in May 1952 it included a number of villages and valuable agricultural land. Although the land continued to be farmed where possible, many of the inhabitants were expelled on the grounds of political unreliability or simply because they lived inconveniently close to the border line. In some instances, entire villages were razed and the inhabitants were relocated far to the east.[60]

Those who remained behind were required to be completely loyal to the regime and support the border guards, helping them by watching for strangers and unfamiliar vehicles. Even so, they had little freedom of movement; special permits were required to enter the zone and farmers worked under close supervision.[60] They could enter and leave the zone an unlimited number of times but could not travel to other villages within the zone.[71] Curfews were imposed to prevent inhabitants from crossing the border under the cover of darkness.[72]

The Sperrzone was not fenced off but was marked with warning signs. The entry roads were controlled by checkpoints (Kontrollpassierpunkte) through which only authorised individuals could pass. The first layer of border fences, the signal fence, lay on the far side of the Sperrzone to control access to the protective strip or Schutzstreifen adjoining the border itself.[73]

Signal fence

The signal or "hinterland" fence (Signalzaun) was the first of the border fences, dividing the Sperrzone from the more heavily guarded protective strip (Schutzstreifen) adjoining the actual border. Its purpose was to provide the guards with an early warning of an escape attempt. The fence itself was not a particularly formidable obstacle, standing only 2 metres (6.6 ft) high. At the top, middle and bottom, rows of electrified barbed wire strands were attached to insulators. Cutting the wires or pulling them out of place resulted in an alarm being activated, alerting the guards to a possible breach of the fence. In practice, though, the border guards found that the fence frequently malfunctioned. The signal fence also had a 2 metres (6.6 ft) wide control strip on its eastern side. The fence was built on open high ground wherever possible, to ensure that intruders would be silhouetted against the sky and thus be more easily spotted. By mid-1989, 1,185 kilometres (736 mi) of signal fencing had been constructed along the border.[74]

Watchtowers and bunkers

The border defences were overlooked by hundreds of watchtowers situated at regular intervals along the Schutzstreifen. They initially took the form of simple wooden huts mounted on legs between 4 and 12 metres (13 and 39 ft) high, usually constructed from locally sourced timber. Most were replaced with concrete watchtowers from the late 1960s onwards in conjunction with the upgrading of the border defences.[75]

By 1989, there were 529 concrete towers along the length of the inner German border and a further 155 towers of steel and wood construction, as well as various little-used observation platforms in trees.[74] The concrete towers were prefabricated from sections that could be assembled within a few days. Their height could be varied by reducing the number of sections as required. They were connected to an electricity supply and telephone line and were equipped with a powerful 1,000-watt searchlight (Suchscheinwerfer) on the roof that could be directed at targets within a 360-degree radius of the watchtower. The windows could be opened to enable the guards to fire out. In addition, the towers had firing ports emplaced in the side walls below the guard compartment.[76]

The towers were principally of three types:

- The BT-11 (Beobachtungsturm-11, "Observation Tower-11") was introduced in 1969. It stood 11 metres (36 ft) high and was constructed of eleven interlocking circular segments 1 inch (2.5 cm) thick, standing on a concrete platform. The guards were stationed in the eight-sided observation compartment at the top, which was accessed via a steel ladder running up the inside of the 1 metre (3.3 ft) wide circular column. Firing ports were located on each face below the windows. The tower proved unstable because of its top-heavy construction and there were instances of BT-11s collapsing in high winds or after heavy rain had softened the ground under the foundations.[77] On the Baltic coast, where 27 BT-11s were constructed to overlook the East German seaboard, the towers had to be evacuated if the wind was blowing at more than force 6 (50 kilometres per hour (31 mph)).[78]

- The BT-9 (Beobachtungsturm-9 , "Observation Tower-9") was introduced from the mid-1970s to remedy the defects of the BT-11. It was constructed in a similar fashion but its square 2 by 2 metres (6.6 ft × 6.6 ft) profile and lower height, at 9 metres (30 ft), made it more stable. The four-sided guard compartment at the top had distinctive copper-tinted windows. A firing port was positioned on each of the faces of the tower on the penultimate stage before the guard compartment.[76]

- The Führungsstelle or Kommandoturm ("command tower") was a shorter and less commonly seen type of tower that served as the command centre of a border sector. It contained various controls such as remote controls for border gates, fence lighting, alert lights and so on. Disturbances of the signal wire and detonations of SM-70 automatic guns would be detected by the command tower. The towers were surmounted with long-range radio antennae to communicate via R-105 radios to other units. A distinctive feature of this type of tower was the prominent air intake box located at ground level.[76]

Around a thousand observation bunkers also stood along the length of the border.[79] The commonest type was a small concrete bunker known as an "earth bunker" (Erdbunker), usually recessed into a depression in the ground with a view along the guard road and border fence. It was constructed from two base sections, each 0.8 metres (2.6 ft) high and 1.8 by 1.8 metres (5.9 ft × 5.9 ft) in cross-section. It terminated in a third section that had two firing ports in the front side and one or two on each of the other sides. The roof was a separate component nesting on top of the concrete bunker, which could accommodate up to two soldiers.[76]

-

The BT-11 (Beobachtungsturm-11), an 11 metres (36 ft) high observation tower introduced in 1969.

-

The BT-9 (Beobachtungsturm-9), a 9 metres (30 ft) high observation tower introduced in the mid-1970s.

-

A Führungsstelle or Kommandoturm, a 6 metres (20 ft) high tower which doubled as an observation tower and command centre.

-

An observation bunker, known as an Erdbunker, preserved at Observation Post Alpha.

-

One of the much less common steel observation towers, manned by three East German border guards.

Guard dogs

Dog runs (Kettenlaufanlagen) were installed on high-risk sectors of the border. The dogs generally did not roam freely but were chained to steel cables measuring up to 100 metres (330 ft) long, which was suspended above the ground on bipods or tripods. This allowed them to move laterally up and down the border line while limiting their movement towards or away from the line. The runs were often portable so that they could be installed where necessary. Wooden kennels were provided to provide shelter from the weather. The dogs were occasionally turned loose in temporary pens adjoining gates or damaged sections of the fence, or in short confined sections of double fencing, to discourage escapees from entering such areas.[80] By the 1970s, there were 315 dog runs with 460 dogs[79]. This figure increased steadily until a total length of 71.5 kilometres (44.4 mi) of dog runs had been installed by mid-1989,[74] with approximately 2,500 dogs employed as watchdogs and another 2,700 so-called "horse dogs". They were a mixture of breeds, including German Shepherds, schnauzers and various mixed breeds.[81]

The fall of the border in 1989 made the dogs redundant overnight. In January 1990, the East German Defence Ministry announced that it had agreed with a West German animal protection society that the so-called "wall dogs" would be resettled with West German families. The plan produced an immediate controversy. Western newspapers claimed that the dogs were "dangerous" and "killer beasts" which had even had their teeth sharpened to a fine point to make their bite more lethal. The East Germans rejected the allegations and characterised the dogs as "the last victims of Stalinism" who were "very much in need of love", as they had been deprived of normal relationships with humans. The negative stories actually made the dogs more popular for a while. Some buyers actively sought to obtain "killer dogs" for dubious purposes. In reality, the dogs were said to be quite docile. One West German buyer was so indignant at his dog's passivity in the face of burglars that he returned it in disgust to the East Germans. The fears proved exaggerated and almost all of the border dogs were successfully adopted.[81]

Patrol roads

Rapid access to all parts of the border line was required for a quick response to escape attempts. This was initially a problem for the East Germans, as few patrol roads existed along the border in its early years. Patrols typically used a footpath that ran along the control strip alongside the inside of the fence.[75]

When the "modern frontier" was constructed in the late 1960s, an all-weather patrol road (Kolonnenweg, literally "column way") was installed to enable the guards to travel rapidly to any point along the border fence. It consisted of two parallel lines of perforated concrete blocks, each block measuring approximately 0.75 metres (2.5 ft) wide and 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) long. The blocks were pieced with four rows of rectangular concrete holes to aid drainage. In some places they were laid crosswise to provide a continuous roadway. They were also occasionally used as foundation stones for structures such as towers and revetments and to create foundations on which towers were constructed.[73]

The Kolonnenweg was usually located between the control strip and the watchtowers, located further back. Around 900 kilometres (560 mi) of patrol roads were built along the border, of which around 130 kilometres (81 mi) was fully paved.[79] In addition to the main Kolonnenweg, there were numerous short access roads built through forests and fields in the Schutzstreifen. Constructed from the same perforated concrete as the Kolonnenweg, these gave the border guards rapid access from the hinterland to the border line. Some civilians were permitted to use such access roads for forestry or farm work, though only with special permission.[82]

Control strips

The control strips (Kontrollstreifen) were lines of bare earth running parallel with the border fences. They were not an obstacle as such but provided a simple and effective way for the border guards to monitor unauthorised travel across the border. It was almost impossible to cross the strip without leaving footprints, enabling the border guards to identify escape attempts that had not otherwise been detected. They could learn how many individuals had crossed, where escape attempts were being made and at which times of day escapees were active. From this information, the border guards were able to determine where and when patrols needed to be increased, where improved surveillance from watchtowers and bunkers was required, and which areas needed additional fortifications.[75]

There were two control strips, both located on the inward-facing sides of the border fences. The secondary "K2" strip, 2 metres (6.6 ft) wide, ran alongside the signal fence to the rear of the Schutzstreifen, while the primary "K6" strip, 6 metres (20 ft) wide, ran along the inside of the border fence or wall. The K6 strip ran almost uninterrupted along the entire length of the border. Where it ran across roads, the road surface would be ripped up to make way for the control strip; where the border ran along streams and rivers, the strip was constructed in parallel to the waterways.[75] In places where the border was prone to escape attempts, the control strip was illuminated at night by high-intensity floodlights (Beleuchtungsanlage) installed on concrete poles, which were also used at vulnerable points such as rivers and streams crossing the border. The strip was patrolled several times a day by guards, who would inspect it carefully for signs of intrusions.[80]

In the West, the control strip became known as the "death strip" (Todesstreifen) because of the shoot-to-kill orders given to the border guards. The East Germans preferred to call it by the more euphemistic name of the "action strip" (Handlungsstreifen).[83] It was also nicknamed the Pieck-Allee ("Pieck Avenue") after East Germany's president Wilhelm Pieck (1949–1960).[84]

The Soviets had pioneered the use of control strips on the borders of the USSR. The same technique was adapted for use in Germany when the border was first fortified from May 1952 onwards, at a time when it was still being policed by Soviet troops.[75] The construction of the control strip in 1952 was carried out by local villagers conscripted into work brigades. One of those involved, a resident of the Thuringian village of Kella, later recalled:

The tree stumps were blown up, and there wasn't enough soil left over so they had to carry dirt up [the hill] in baskets. They also had to bring all sorts of gardening tools with them. The ten-metre strip was made into something like cultivated garden soil – so that you could see every footprint, every impression. And it was patrolled regularly ... usually by three [officers]."[32]

The control strips were later maintained by a specialist engineering corps, the Grenzpioniere. They used 3 metres (9.8 ft) wide harrows towed by KT-50 bulldozers and copious quantities of herbicide to keep the .[82]

Anti-vehicle barriers

Various types of anti-vehicle barriers were constructed along the inner German border. In the early days of the border, the East Germans blocked vehicle access to roads crossing the border by tearing up the road surface and digging a ditch or building a mound of rubble to physically block the carriageway. Some places were blocked with Czech hedgehogs or cheveaux-de-frise barricades, known in German as Panzersperre or Stahligel ("steel hedgehogs"). These were constructed from three or four pairs of 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) long rails welded to form a spiky tripod weighing over 500 kilograms (1,100 lb) – easily heavy enough to prevent a car from pushing them out of the way. They were a familiar sight on the Berlin Wall and were widely used on the inner German border as well.[85] The barricades were emplaced at intervals calculated to be narrow enough to prevent even small vehicles, such as the iconic Trabant, to pass between them.[82]

Rows of anti-vehicle ditches or Kraftfahrzeug Sperrgraben (KFZ-Sperrgraben) were built during the era of the "modern frontier". These lined 829 kilometres (515 mi) of the border and were absent only where natural obstacles such as streams, rivers, gullies or thick forests made such barriers unnecessary. The ditches were constructed as a V-shaped cut about 0.8 metres (2.6 ft) deep, with a steeply sloping western edge and shallow eastern edge. The western edge was faced with concrete slabs that were 15 centimetres (5.9 in) deep. They proved to be an extremely effective obstacle, preventing almost any type of vehicle from crossing.[85]

The outer fences and walls

The border fences were constructed in a number of phases, starting with the initial fortification of the border from May 1952. The first-generation fence was a crudely built structure comprising barbed-wire fences (Stacheldrahtzäune) standing between 1.2 and 2.5 metres (3.9 and 8.2 ft) high. The fence was overlooked by watchtowers located at strategic intervals along the border. It was, however, a flawed obstacle. In some places it was so poorly constructed or maintained that livestock were able to wander unhindered across the border. In a few places gaps were purposefully left with lowered gate poles in front of them and anti-vehicle Czech hedgehog barricades behind.[86]

The fences were strengthened in the late 1950s, particularly in areas where a high number of escapes were occurring. Parallel rows of barbed wire fences were built, with concertina wire added between the fences in some places to further hinder escapees. The outer fence was often located very close to the actual border. A further obstacle was added by placing short wooden anchor posts about 2 metres (6.6 ft) outwards from both fences. Barbed wire was strung between them to form a V-shape to hinder lateral movement by escapees. In some low-risk areas, only a single fence was installed.[87]

-

Reconstruction of the "first generation" border fence as erected in 1952, with control strip in the foreground.

-

The "second generation" border fences pictured in 1962, with a row of poorly maintained barbed wire in the foreground, a control strip, two rows of barbed wire further back and a watchtower at the rear.

-

The third generation border fence, constructed from several overlapping horizontal tiers of expanded steel mesh fencing. A border marker pole is in the foreground.

-

The border wall at Mödlareuth. The sign reads: "Warning! Border in middle of stream." Much of the wall has been preserved as a memorial.

A "third generation" border fence, much more solidly constructed, was installed in an ongoing programme of improvements from the late 1960s to the 1980s. The entire fence line was moved back to create an outer strip (see below) between the fence and the actual border. The barbed wire fences were replaced with a barrier that was usually between 3.2 and 4 metres (10 and 13 ft) high. It was constructed with expanded metal mesh (Metalgitterzaun) panels. The openings in the mesh were generally too small to provide finger-holds and were very sharp. The panels could not easily be pulled down, as they overlapped, and they could not be cut through with a bolt- or wire-cutter. Nor could they be tunnelled under easily, as the bottom segment of the fences was partially buried in the ground. In a number of places, more lightly constructed fences (Lichtsperren) consisting of mesh and barbed wire lined the border.[80]

The fence was not contiguous but was could be crossed at a number of points, other than the official border crossings. Gates were installed to enable border guards to patrol up to the border line and to give engineers access for maintenance on the outward-facing side of the barrier. Like the fence itself, the gates were designed to be escape-proof. They were hinged from the outside but opened inwards and the pivot pins were welded to prevent them from being removed. They were chained and locked with heavy-duty padlocks, and a sharp saw-toothed steel strip was bolted to the top of the gates to prevent them being climbed.[80]

In some places, villages adjoining the border were fenced with wooden board fences (Holzlattenzaun) or concrete barrier walls (Betonsperrmauern) standing around 3–4 metres (9.8–13.1 ft) high. Windows in buildings adjoining the border were bricked or boarded up, and buildings deemed too close to the border were pulled down. The barrier walls stood along only a small percentage of the border – 29.1 kilometres (18.1 mi) of the total length by 1989.[75] A notorious example was in the divided village of Mödlareuth, where the border ran along the course of a stream that bisected the village. When the border was first fortified in 1952, a wooden board fence was erected just inside East German territory. It was replaced in 1966 by a 700 metres (2,300 ft) long, 3.3 metres (11 ft) high concrete wall built through the village on the East German side of the stream. The village was nicknamed "Little Berlin" for its resemblance to the divided city. The name was well-earned, as the wall was constructed along very similar lines to the one in Berlin. Like the Berlin Wall, its top was lined with sewer pipes or steel pipes to prevent it from being climbed and its interior perimeter was floodlit at night.[88]

Anti-personnel mines

The outer border fences were lined with anti-personnel mines designed to inflict crippling injuries on would-be escapees. The mining of the border began in 1966; by the 1980s, some 1.3 million mines of various Soviet-made types had been laid. The mines were usually laid in a standardised pattern of a rectangular box, 23 by 180 metres (75 by 591 ft), containing three rows of mines. The most common type was the Soviet-made PMD-6M mine. However, its wooden construction made it unreliable and prone to decay. The PMD-6Ms were later replaced by more durable plastic mines of the PMN-2, PMP-71 and PPM-2 types. Most of the mines were pressure-activated, requiring someone to step on one to detonate it, with the exception of the tripwire-activated POMS-2 stake mine. The minefields were not marked on the East German side, though Achtung! Minen! signs were often posted by the West Germans on their side. The mines were a hazard to civilians on both sides of the border; they were frequently set off by animals such as deer and they could be washed out of position by rain or floods. It was not unknown for mines to travel hundreds of metres into fields and streams on either side of the border.[89]

In 1970, the East Germans began to introduce the SM-70 (Splittermine-70) directional anti-personnel mine, mounted on the border fence itself. Some 60,000 SM-70s were eventually installed. It was given various descriptions in the West – "spring gun", "self-firing device" and so on – though to the East Germans, it was known as the "automated firing device" or Selbstschußapparat. The device consisted of a horizontally oriented cone filled with 180 grams (6.3 oz) of TNT explosive into which was embedded around 110 small sharp-edged steel cubes. It was fitted to the inward-facing side of the border fence at intervals of around 10 metres (33 ft). The device was triggered if the tripwire connected to the firing mechanism was pulled or cut.[90] It was potentially lethal to a range of around 120 metres (390 ft). On one occasion, when a deer fell victim to an SM-70, an observer noted that "an approximately 5 meter area appeared as if it had been worked over by a rake."[47] By 1976, SM-70s had been installed along 248 km of the border and conventional minefields lined another 491 km.[91] The mines were eventually removed by the end of 1984 in the face of international condemnation of the East German government.[90]

The outer strip

Until the late 1960s the border fortifications were constructed almost up to the actual border line. The later "modern frontier", by contrast, incorporated a wide strip of cleared land on the Western side in front of the border fence. The outer strip ranged in width from 20 metres (66 ft) to as much as 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) in some places. It gave the border guards a clear field of fire to target escapees who had made it over the fence and provided a buffer zone where engineers could work on maintaining the outward face of the border defences. Access to the outer strip was very tightly controlled, to ensure that the guards themselves would not be tempted to escape. Although often described by Western sources as a "no-man's land", it was in fact wholly East German territory; trespassers could be arrested or shot.[92]

The border line

The actual border line between West and East Germany was located on the far side of the outer strip. It was marked by granite border stones (Grenzsteine), 20 centimetres (7.9 in) square with a + carved on the top and the letters "DDR" on the west-facing edge. In August 1967, the East Germans erected 2,622 distinctive border markers or "barber poles" (Grenzsäule or Grenzpfähle), each located about 500 feet (150 m) apart. They were made of concrete and were painted with the black, red and gold colours of the German flag. Some can still be seen in situ today. A metal East German coat of arms, the Staatsemblem, was fixed to the side of the column that faced West Germany. The column terminated in a metal spike. This was intended to stop birds using the border markers as a perch and thereby prevent them defecating on the coat of arms.[45]

On the West German side there were no barriers of any kind, nor even any patrol roads in most areas. Warning signs (Grenzschilder) with messages such as Achtung! Zonengrenze! ("Danger! Border zone!") or Halt! Hier Zonengrenze ("Stop! The zonal border is here") notified visitors of the presence of the border. Foreign military personnel were restricted from approaching the border to avoid clashes or other unwanted incidents. Signs in English and German provided notifications of the distance to the border to discourage accidental crossings. No such restriction applied to Western civilians, who were free to go up to the border line. There was no physically obstacles to stop them actually crossing it, and there were incidents of West Germans crossing the border to steal East German border markers as souvenirs (at considerable risk, since the East German border guards sought to prevent such "provocations").[45]

The "blue border"

The inner German border system also extended along the Baltic coast, dubbed the "blue border" or sea border of the GDR. The coastline was partly fortified along the mouth of the river Trave opposite the West German port of Travemünde. Watchtowers, walls and fences stood along the marshy shoreline to deter escape attempts and the water was patrolled by high-speed East German boats. The continuous line of the inner German border ended at the peninsula of Priwall, incongruously overlooking a nudist beach on the Western side. From Priwall to Boltenhagen, along some 15 km of the eastern shore of the Bay of Mecklenburg, the East German shoreline was part of the restricted-access Schutzgebiet. The rest of the coast up to the Polish border, including the whole of the island of Rügen, was subject to security controls.[82]

The East Germans sought to hinder seaborne escapes by implementing a variety of security measures along the Baltic coastline. Access to boats was severely limited, as was camping in the coast region. Watchtowers were built, of the same type as those used on the land border, along the entire length of the coastline from Priwall on the West German border to Altwarp on the Polish border.[82] If a suspected escape attempt was spotted, high-speed patrol boats would be dispatched to intercept the fugitives. Armed patrols equipped with powerful mobile searchlights monitored the beaches.[93]

Escapees sought to reach a number of possible destinations across the Baltic. These included the western (West German) shore of the Bay of Mecklenburg; a Danish lightship off the port of Gedser; the southern Danish islands of Lolland and Falster; or simply the international shipping lanes, where escapees would hope to be picked up by a passing freighter. The odds were, however, strongly against escapees. The Baltic Sea's cold waters and strong currents made it at least as hazardous as the man-made obstacles of the landward border. It was not unusual for the bodies of drowned escapees to wash up at various points along the Baltic shore. In all, as many as 189 people are estimated to have died attempting to flee via the Baltic.[94]

Some escapees sought to escape across the "blue border" by jumping overboard from East German ships docked in Baltic harbours. This practice reached such epidemic proportions in the 1960s that Danish harbourmasters took the precaution of installing extra life-saving equipment on quaysides where East German vessels docked. The East German regime responded by stationing armed Transportpolizei (Trapos) on East German passenger ships to deal forcefully with escape attempts. On one occasion in August 1961 the Trapos caused an international incident in the Danish port of Gedser, when they beat up a would-be escapee on the quayside and fired a number of shots, some of which hit a Danish boat in the harbour. The next day, thousands of Danes turned out to protest against "Vopo [[[Volkspolizei]]] methods." In the end, this escape route was choked off by further restricting the already limited travel rights of the East German population.[95]

Guarding the border

East Germany

The East German side of the border was guarded initially by the Border Troops (Pogranichnyie Voiska) of the Soviet NKVD (later the KGB). In 1946, the Soviets established a locally recruited paramilitary force, the German Border Police (Deutsche Grenzpolizei or DGP), under the administration of the Interior Ministry for Security of the State Frontier (Innenministerium zum Schutz der Staatsgrenze). Soviet troops and the DGP shared responsibility for patrolling the border and crossing points until 1955/56, when the Soviets handed over control to the East Germans.[96]

The DGP became increasingly militarised as the East German government decided that protecting the border was a military task. Although it was notionally a police force it was equipped with heavy weapons, including tanks and self-propelled artillery. In 1961 the DGP was converted into a military force within the National People's Army (Nationale Volksarmee, NVA). The newly renamed Border Troops (Grenztruppen, commonly nicknamed the "Grenzer") came under the NVA's Border Command or Grenzkommando. They were responsible for securing and defending the borders with West Germany, Czechoslovakia, Poland, the Baltic Sea and West Berlin. At their peak, the Grenztruppen had up to 50,000 personnel.[96]

Around half of the Grenztruppen were conscripts, a lower proportion than in other branches of the East German armed forces. Their political reliability was under especially close scrutiny due to the sensitive nature of their role. They were subjected to intensive ideological indoctrination, which made up as much as 50 per cent of their training time. They were not allowed to serve in areas near their homes. Some categories of individuals were not allowed to serve in the Grenztruppen at all; for instance if they had close relatives in West Germany, a record of dissent or dissenting family members, or were actively religious.[97] Even if they were accepted for service, trainee border guards who were suspected of political unreliability were weeded out at an early stage. As one later recalled: "At the officers' training school there are always 10 per cent whose loyalty is suspect who are never sent to the border."[98]

The ultimate role of the Grenztruppen was to prevent border escapes by any means necessary, including by shooting escapees. Their marksmanship was expected to be substantially better than that of regular NVA troops; they were required to be able to hit two moving targets at 200 metres (660 ft) with only four shots, by day or night. Failure to shoot was itself a punishable offence, resulting in severe consequences for a soldier and his family.[99]

The East German regime's distrust of its own citizens extended to its border guards, who were in a better position to defect than almost anyone else in the country. Many did in fact flee across the border; between 1961 and 1989, around 7,000 border guards tried to escape. 2,500 succeeded but 5,500 were caught and imprisoned for up to five years.[100] To prevent such defections, the Stasi secret police kept a close watch on the border guards with agents and informers. A special Stasi unit worked covertly within the Grenztruppen, posing as regular border guards, between 1968 and 1985.[101] The Stasi also maintained a pervasive network of informers within the ranks of the Grenztruppen. One in ten officers and one in thirty enlisted men were said to have been "liaison agents", the euphemism for an informer. The Stasi regularly interviewed and maintained files on every border guard. Stasi operatives were directly responsible for some aspects of border security; passport control stations were entirely manned by Stasi officers wearing Grenztruppen uniforms.[102]

As a further measure to prevent escapes, the patrol patterns of the Grenztruppen were carefully arranged to reduce any chance of a border guard defecting. Patrols, watchtowers and observation posts were always manned by two or three soldiers at a time. They were not allowed to go out of each others' sight in any circumstances. When changing the guard in watchtowers, they were under orders to enter and exit the buildings in such a way that there were never less than two people on the ground. Duty rosters were organised to prevent friends and roommates being assigned to the same patrols. The pairings were switched (though not randomly) to ensure that the same people did not repeatedly carry out duty together. Individual border guards did not know until the start of their shift with whom they would be working that day. If a guard attempted to escape, his colleagues were under instructions to shoot him without hesitation or prior warning.[102]

Much of the work of the border guards focused on maintaining and scrutinising the border defences. This included carrying out repair work, looking for evidence of escape attempts, examining the area for signs of suspicious activities and so on. The patrol times and routes were deliberately varied to ensure that there was no predictability, ensuring that a patrol could potentially appear at any time from either direction. Guards posted in watchtowers played an important role in monitoring the border, though shortages of personnel meant that the watchtowers were not continuously manned. During the final years of the East German state, the lack of manpower was so severe that cardboard cut-outs of guards were placed in towers to present the illusion that they were occupied.[103]

The Grenztruppen also had the task of gathering intelligence on West German and NATO activities across the border line. This task was performed primarily by the Grenzaufklärungszug (GAK), an elite reconnaissance force within the Grenztruppen. These became a familiar sight for Western observers of the border as the GAK troopers, uniquely, were tasked with patrolling the western side of the border fence – i.e. in the outer strip, adjoining the geographical border between the two Germanies. Not surprisingly, given that they could defect with only a few footsteps in the right direction, the GAKs were drawn from the most politically reliable echelons of the Grenztruppen. They worked closely with the Stasi and were often seen photographing targets across the border. They also guarded work details carrying out maintenance work on the western side of the fence. The workers would be covered by machine guns to discourage them from attempting to escape.[103]

To maintain what the East German state called Ordnung und Sicherheit ("order and security") along the border, local civilians were co-opted to assist the border guards and police. A decree of 5 June 1958 spoke of encouraging "the working population in the border districts of the GDR [to express] the desire to help by volunteering to guarantee the inviolability of the border." Civilians living in villages along the border were recruited into the "Border Helpers" (Grenzhelfer) and "People's Police Helpers" (Volkspolizeihelfer). They were tasked with patrolling the strip behind the border defences, assisting at control checkpoints and reporting any unusual activities or strangers in their area. In one border community, Kella in Thuringia, the mayor boasted in a 1967 speech that nearly two-thirds of arrests on the border that year had been made by local civilians. The locals were, however, kept away from the border strip itself. The border guards were usually recruited from far-away regions of East Germany to ensure that people living near the border would not become familiar with its workings.[104] Even children were brought into the fold. A "Young Friends of the Border Guards" organisation was established for children living in the border region, modelled on a similar Soviet organisation. The original Soviet version fostered a cult of the border guards, promoting slogans such as "The frontier runs through people's hearts."[105]

West Germany

A number of West German state organisations were responsible for policing the western side of the border. These included the Bundesgrenzschutz (BGS, Federal Border Protection), the Bayerische Grenzpolizei (Bavarian Border Police) and the Bundeszollverwaltung (Federal Customs Administration).[45] In addition, the British Army, the British Frontier Service and the United States Army carried out patrols and provided backup in their respective sectors of the border. West German troops were not allowed to approach within one kilometre of the border individually or within five kilometres in formation without being accompanied by BGS personnel.[2]

The BGS – which today forms part of the Bundespolizei – was responsible for policing Germany's frontiers. It was initially a paramilitary force of 10,000, established in 1951, which was responsible for policing a zone 30 kilometres (19 mi) deep along the border. It eventually became the basis for the present national semi-militarised police force.[106] Its numbers were later expanded to 20,000 men, a mixture of conscripts and volunteers equipped with armoured cars, anti-tank guns, helicopters, trucks and jeeps. Although it was not intended to be able to repel a full-scale invasion, the BGS was tasked with dealing with small-scale threats to the security of West Germany's borders, including the international borders as well as the inner German border. It had limited police powers within its zone of operations to enable it to deal with threats to the peace of the border. The BGS had a reputation for assertiveness which made it especially unpopular with the East Germans, who routinely criticised it as a reincarnation of Hitler's SS. It also sustained a long-running feud with the Bundeszollverwaltung over which agency should have the lead responsibility for the inner German border.[107]