| Influenza | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Family medicine, pulmonology, infectious diseases, emergency medicine |

Influenza, commonly known as the flu, is an infectious disease of birds and mammals caused by an RNA virus of the family Orthomyxoviridae (the influenza viruses). In people, common symptoms of influenza are fever, sore throat, muscle pains, severe headache, coughing, and weakness and fatigue.[1] In more serious cases, influenza causes pneumonia, which can be fatal, particularly in young children and the elderly. Although the common cold is sometimes confused with influenza, the common cold is a much less severe disease and caused by a different virus.[2] Similarly, gastroenteritis is sometimes called "stomach flu" or "24-hour flu", but is unrelated to influenza.

Typically, influenza is transmitted from infected mammals through the air by coughs or sneezes creating aerosols containing the virus, and from infected birds through their droppings. Influenza can also be transmitted by saliva, nasal secretions, feces and blood. Infections either occur through direct contact with these bodily fluids, or by contact with contaminated surfaces. Flu viruses remain infectious for over 30 days at 0°C (32°F) and about one week at human body temperature, although they are rapidly inactivated by disinfectants and detergents.[3]

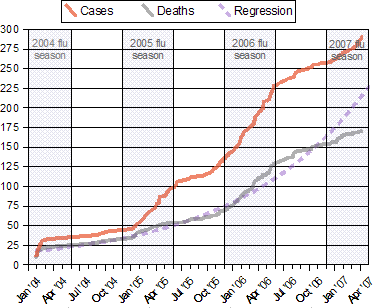

Flu spreads around the world in seasonal epidemics, killing millions of people in pandemic years and hundreds of thousands in non-pandemic years. Three influenza pandemics occurred in the 20th century—each following a major genetic change in the virus—and killed tens of millions of people. Often, these pandemics result from the spread of a flu virus between animal species. Since it first killed humans in Asia in the 1990s a deadly avian strain of H5N1 has posed the greatest influenza pandemic threat. However, this virus has not yet mutated to spread easily between people.[4]

Vaccinations against influenza are most common in high-risk humans in industrialised countries[5] and farmed poultry.[6] The most common human vaccine is the trivalent flu vaccine that contains purified and inactivated material from three viral strains. Typically this vaccine includes material from two influenza A virus subtypes and one influenza B virus strain.[7] A vaccine formulated for one year may be ineffective in the following year, since the influenza virus changes every year and different strains become dominant. Antiviral drugs can be used to treat influenza, with neuraminidase inhibitors being particularly effective.

| Influenza (flu) |

|---|

|

Etymology

The term influenza has its origins in fifteenth-century Italy, where the cause of the disease was ascribed to unfavourable astrological influences. Evolution in medical thought led to its modification to influenza di freddo, meaning "influence of the cold". The word "influenza" was first attested in English in 1743 when it was borrowed during an outbreak of the disease in Europe.[8] Archaic terms for influenza include epidemic catarrh, grippe, (sometimes spelt "grip" or "gripe"), sweating sickness and Spanish fever (particularly for the 1918 pandemic strain).[9]

History

The symptoms of human influenza were clearly described by Hippocrates roughly 2400 years ago.[10][11] Since then, the virus has caused numerous pandemics. Historical data on influenza are difficult to interpret, as the symptoms can be similar to those of other diseases, such as diphtheria, pneumonic plague, typhoid fever, dengue or typhus. The first convincing record of an influenza pandemic was of an outbreak in 1580, which began in Asia and spread to Europe via Africa. In Rome over 8,000 people were killed and several Spanish cities were almost wiped out.[12] Pandemics continued sporadically throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, with the pandemic of 1830-1833 being particularly widespread; it infected approximately a quarter of the people exposed.[12]

The most famous and lethal outbreak was the so-called Spanish flu pandemic (type A influenza, H1N1 subtype), which lasted from 1918 to 1919. Older estimates say it killed 40-50 million people[13] while current estimates say 50 million to 100 million people worldwide were killed.[14] This pandemic has been described as "the greatest medical holocaust in history" and may have killed as many people as the black death.[12] This huge death toll was caused by an extremely high infection rate of up to 50%, and the extreme severity of the symptoms.[13] Indeed, symptoms in 1918 were so unusual that initially influenza was misdiagnosed as dengue, cholera, or typhoid. One observer wrote, "One of the most striking of the complications was hemorrhage from mucous membranes, especially from the nose, stomach, and intestine. Bleeding from the ears and petechial hemorrhages in the skin also occurred."[14] The majority of deaths were from bacterial pneumonia, a secondary infection caused by influenza, but the virus also killed people directly, causing massive hemorrhages and edema in the lung.[15]

The Spanish flu pandemic was truly global, spreading even to the Arctic and remote Pacific islands. The unusually severe disease killed 2.5 % of those infected, as opposed to the more usual flu epidemic mortality rate of 0.1 %.[15] Another unusual feature of this pandemic was that it mostly killed young adults, with 99% of pandemic influenza deaths occurring in people under 65 and more than half in young adults 20 to 40 years old.[16] This is unusual since influenza is normally most deadly to the very young (under age 2) and the very old (over age 70). The total mortality of the 1918-1919 pandemic is not known, but it is estimated that 2.5 % to 5 % of the world's population was killed. As many as 25 million may have been killed in the first 25 weeks; in contrast, HIV/AIDS has killed 25 million in its first 25 years.[14]

Later flu pandemics were not so devastating. They included the 1957 Asian Flu (type A, H2N2 strain) and the 1968 Hong Kong Flu (type A, H3N2 strain), but even these smaller outbreaks killed millions of people. In contrast to 1918 Spanish flu, in later pandemics antibiotics were available to control secondary infections, and this may have helped reduce mortality.[15]

| Name of pandemic | Date | Deaths | Subtype involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asiatic (Russian) Flu | 1889-90 | 1 million | possibly H2N2 |

| Spanish Flu | 1918-20 | 40 million | H1N1 |

| Asian Flu | 1957-58 | 1 to 1.5 million | H2N2 |

| Hong Kong Flu | 1968-69 | 0.75 to 1 million | H3N2 |

The etiological cause of influenza, the Orthomyxoviridae family of viruses, was first discovered in pigs by Richard Schope in 1931.[19] This discovery was shortly followed by the isolation of the virus from humans by a group headed by Patrick Laidlaw at the Medical Research Council of the United Kingdom in 1933.[20] However, it was not until Wendell Stanley first crystallised tobacco mosaic virus in 1935 that the non-cellular nature of viruses was appreciated.

The first significant step towards preventing influenza was the discovery by Thomas Francis, Jr. in 1944 of a live vaccine for influenza. This built on work by Frank Macfarlane Burnet, who showed that the virus lost virulence when it was cultured in fertilised hen's eggs.[21] Application of this observation by Francis allowed his group of researchers at the University of Michigan to develop the first flu vaccine, with support from the U.S. army.[22] The U.S. army was deeply involved in this research due to its experience of influenza in World War I, when thousands of troops were killed by the virus in a matter of months.[14]

Although there were scares in New Jersey in 1976 (with the Swine Flu), world-wide in 1977 (with the Russian Flu), and in Hong Kong and other Asian countries in 1997 (with H5N1 avian influenza), there have been no major pandemics since the 1968 Hong Kong Flu. Immunity to previous pandemic influenza strains and vaccination may have limited the spread of the virus, and may have helped prevent further pandemics.[18]

Microbiology

Types of influenza virus

The influenza virus is an RNA virus of the family Orthomyxoviridae, which comprises the influenzaviruses, Isavirus and Thogotovirus. There are three types of influenza virus: Influenzavirus A, Influenzavirus B or Influenzavirus C. Influenza A and C infect multiple species, while influenza B almost exclusively infects humans.[23]

The type A viruses are the most virulent human pathogens among the three influenza types and causes the most severe disease. The Influenza A virus can be subdivided into different serotypes based on the antibody response to these viruses.[23] The serotypes that have been confirmed in humans, ordered by the number of known human pandemic deaths, are:

- H1N1 caused "Spanish Flu".

- H2N2 caused "Asian Flu".

- H3N2 caused "Hong Kong Flu".

- H5N1 is a pandemic threat in 2006-7 flu season.

- H7N7 has unusual zoonotic potential.[24]

- H1N2 is endemic in humans and pigs.

- H9N2, H7N2, H7N3, H10N7.

Influenza B virus is almost exclusively a human pathogen, and is less common than influenza A. The only other animal known to be susceptible to influenza B infection is the seal.[25] This type of influenza mutates at a rate 2-3 times lower than type A[26] and consequently is less genetically diverse, with only one influenza B serotype.[23] As a result of this lack of antigenic diversity, a degree of immunity to influenza B is usually acquired at an early age. However, influenza B mutates enough that lasting immunity is not possible.[27] This reduced rate of antigenic change, combined with its limited host range (inhibiting cross species antigenic shift), ensures that pandemics of influenza B do not occur.[28]

The influenza C virus infects humans and pigs, and can cause severe illness and local epidemics.[29] However, influenza C is less common than the other types and usually seems to cause mild disease in children.[30][31]

Structure and properties

The following applies for Influenza A viruses, although other strains are very similar in structure[32]:

The influenza A virus particle or virion is 80-120 nm in diameter and usually roughly spherical, although filamentous forms can occur.[33] Unusually for a virus, the influenza A genome is not a single piece of nucleic acid; instead, it contains eight pieces of segmented negative-sense RNA (13.5 kilobases total), which encode 11 proteins (HA, NA, NP, M1, M2, NS1, NEP, PA, PB1, PB1-F2, PB2).[34] The best-characterised of these viral proteins are hemagglutinin and neuraminidase, two large glycoproteins found on the outside of the viral particles. Neuraminidase is an enzyme involved in the release of progeny virus from infected cells, by cleaving sugars that bind the mature viral particles. By contrast, hemagglutinin is a lectin that mediates binding of the virus to target cells and entry of the viral genome into the target cell.[35] The hemagglutinin (HA or H) and neuraminidase (NA or N) proteins are targets for antiviral drugs.[36] These proteins are also recognised by antibodies, i.e. they are antigens.[18] The responses of antibodies to these proteins are used to classify the different serotypes of influenza A viruses, hence the H and N in H5N1.

Infection and replication

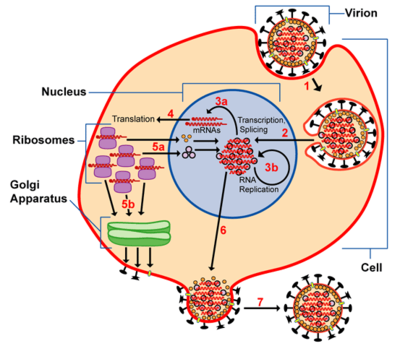

Influenza viruses bind through hemagglutinin onto sialic acid sugars on the surfaces of epithelial cells; typically in the nose, throat and lungs of mammals and intestines of birds (Stage 1 in infection figure).[37] The cell imports the virus by endocytosis. In the acidic endosome, part of the haemagglutinin protein fuses the viral envelope with the vacuole's membrane, releasing the viral RNA (vRNA) molecules, accessory proteins and RNA-dependent RNA transcriptase into the cytoplasm (Stage 2).[38] These proteins and vRNA form a complex that is transported into the cell nucleus, where the RNA-dependent RNA transcriptase begins transcribing complementary positive-sense vRNA (Steps 3a and b).[39] The vRNA is either exported into the cytoplasm and translated (step 4), or remains in the nucleus. Newly-synthesised viral proteins are either secreted through the Golgi apparatus onto the cell surface (in the case of neuraminidase and hemagglutinin, step 5b) or transported back into the nucleus to bind vRNA and form new viral genome particles (step 5a). Other viral proteins have multiple actions in the host cell, including degrading cellular mRNA and using the released nucleotides for vRNA synthesis and also inhibiting translation of host-cell mRNAs.[40]

Negative-sense vRNAs that form the genomes of future viruses, RNA-dependent RNA transcriptase, and other viral proteins are assembled into a virion. Hemagglutinin and neuraminidase molecules cluster into a bulge in the cell membrane. The vRNA and viral core proteins leave the nucleus and enter this membrane protrusion (step 6). The mature virus buds off from the cell in a sphere of host phospholipid membrane, acquiring hemagglutinin and neuraminidase with this membrane coat (step 7).[41] As before, the viruses adhere to the cell through hemagglutinin; the mature viruses detach once their neuraminidase has cleaved sialic acid residues from the host cell.[37] After the release of new influenza virus, the host cell dies.

Because of the absence of RNA proofreading enzymes, the RNA-dependent RNA transcriptase makes a single nucleotide insertion error roughly every 10 thousand nucleotides, which is the approximate length of the influenza vRNA. Hence, nearly every newly-manufactured influenza virus is a mutant.[42] The separation of the genome into eight separate segments of vRNA allows mixing or reassortment of vRNAs if more than one viral line has infected a single cell. The resulting rapid change in viral genetics produces antigenic shifts and allow the virus to infect new host species and quickly overcome protective immunity.[18] This is important in the emergence of pandemics, as discussed in the Epidemiology section.

Symptoms

In humans, influenza's effects are much more severe than those of the common cold, and last longer. Recovery takes about one to two weeks. Influenza can be deadly, especially for the weak, old or chronically ill.[18] According to the on-line version of the Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy:

- "Symptoms start 24 to 48 hours after infection and can begin suddenly. Chills or a chilly sensation are often the first indication of influenza. Fever is common during the first few days, and the temperature may rise to 102 to 103 °F (approximately 38 to 39 °C). Many people feel sufficiently ill to remain in bed for days; they have aches and pains throughout the body, most pronounced in the back and legs."[1]

The virus attacks the respiratory tract, is transmitted from person to person by saliva droplets expelled by coughing or sneezing, and can cause the following symptoms:

It can be difficult to distinguish between the common cold and influenza in the early stages of these infections.[2] Since anti-viral drugs are most effective in treating influenza if given early (see treatment section, below), it can be important to identify cases early. Of the symptoms listed above, a combination of cough, fever and nasal congestion is good evidence that the infection is influenza.[43]

Most people who get influenza will recover in one to two weeks, but others will develop life-threatening complications (such as pneumonia). According to the World Health Organization: "Every winter, tens of millions of people get the flu. Most are home, sick and miserable, for about a week. Some—mostly the elderly—die. We know the world-wide death toll exceeds a few hundred thousand people a year, but even in developed countries the numbers are uncertain, because medical authorities don't usually verify who actually died of influenza and who died of a flu-like illness."[44] Even healthy people can be affected, and serious problems from influenza can happen at any age. People over 50 years old, very young children and people of any age with chronic medical conditions, are more likely to get complications from influenza: such as pneumonia, bronchitis, sinus, and ear infections.[45]

The flu can worsen chronic health problems. People with emphysema, chronic bronchitis or asthma may experience shortness of breath while they have the flu, and influenza may cause worsening of coronary heart disease or congestive heart failure.[46] Smoking is another risk factor associated with more serious disease and increased mortality from influenza.[47]

Common symptoms of the flu such as fever, headaches, and fatigue, come from the huge amounts of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (such as interferon or tumor necrosis factor) produced from influenza-infected cells.[2][48] In contrast to the rhinovirus that causes the common cold, influenza does cause tissue damage, so symptoms are not entirely due to the inflammatory response.[49]

Epidemiology

Seasonal variations

Influenza reaches peak prevalence in winter, and because the Northern and Southern Hemisphere have winter at different times of the year, there are actually two flu seasons each year. This is why the World Health Organization (assisted by the National Influenza Centers) makes recommendations for two different vaccine formulations every year; one for the Northern, and one for the Southern Hemisphere.[51]

It remains unclear why outbreaks of the flu occur seasonally rather than uniformly throughout the year. One possible explanation is that, because people are indoors more often during the winter, they are in close contact more often, and this promotes transmission from person to person. Another is that cold temperatures lead to drier air, which may dehydrate mucus, preventing the body from effectively expelling virus particles. The virus may also survive longer on exposed surfaces (doorknobs, countertops, etc.) in colder temperatures. Increased travel and visitation due to the Northern Hemisphere winter holiday season may also play a role.[52] However, seasonal changes in infection rates are also seen in tropical regions and these peaks of infection are seen mainly during the rainy season.[53] Seasonal changes in contact rates from school-terms, which are a major factor in other childhood diseases such as measles and pertussis, may also play a role in flu. A combination of these small seasonal effects may be amplified by "dynamical resonance" with the endogenous disease cycles.[54] H5N1 exibits seasonality in both humans and birds.[50]

Epidemic and pandemic spread

As influenza is caused by a variety of species and strains of viruses, in any given year some strains can die out while others create epidemics while yet another strain can cause a pandemic. Typically, in a year's normal two flu seasons (one per hemisphere) there are between three and five million cases of severe illness and up to 500,000 deaths worldwide, which by some definitions is a yearly influenza epidemic.[55] A recent study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an United States government agency concerned with issues of public health, estimated an average of 36,000 deaths each year from influenza-related complications in America.[56] Every ten to twenty years a pandemic occurs, which infects a large proportion of the world's population, and can kill tens of millions of people (see history section).

New influenza viruses are constantly being produced by mutation or by reassortment.[23] Mutations can cause small changes in the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase antigens on the surface of the virus. This is called antigenic drift, which creates an increasing variety of strains over time until one of the variants eventually achieves higher fitness, becomes dominant, and rapidly sweeps through the human population often causing an epidemic.[57] In contrast, when influenza viruses re-assort, they may acquire new antigens - for example by reassortment between avian strains and human strains. This is called antigenic shift. If a human influenza virus is produced with entirely novel antigens, everybody will be susceptible and the novel influenza will spread uncontrollably, causing a pandemic.[58]

Prevention and treatment

Vaccination and hygiene

Vaccination against influenza with a flu vaccine is strongly recommended for high-risk groups, such as children and the elderly. These vaccines can be produced in several ways; the most common method is to grow the virus in fertilised hen eggs. After purification, the virus is inactivated (for example, by treatment with detergent) to produce an inactivated-virus vaccine. Alternatively, the virus can be grown in eggs until it loses virulence and the avirulent virus given as a live vaccine.[18] The effectiveness of these flu vaccines is variable. Due to the high mutation rate of the virus, a particular flu vaccine usually confers protection for no more than a few years. Every year, the World Health Organization predicts which strains of the virus are most likely to be circulating in the next year, allowing pharmaceutical companies to develop vaccines that will provide the best immunity against these strains.[51] Vaccines have also been developed to protect poultry from avian influenza. These vaccines can be effective against multiple strains and are used either as part of a preventative strategy, or combined with culling in attempts to eradicate outbreaks.[59]

It is possible to get vaccinated and still get influenza. The vaccine is reformulated each season for a few specific flu strains, but cannot possibly include all the strains actively infecting people in the world for that season. It takes about six months for the manufacturers to formulate and produce the millions of doses required to deal with the seasonal epidemics; occasionally, a new or overlooked strain becomes prominent during that time and infects people although they have been vaccinated (as in the 2003-2004 season).[60] It is also possible to get infected just before vaccination and get sick with the very strain that the vaccine is supposed to prevent, as the vaccine takes about two weeks to become effective.[45]

Vaccination is most important in vulnerable populations, such as children or the elderly. The 2006-2007 season is the first in which the CDC has recommended that children younger than 59 months receive the annual flu vaccine.[61] Vaccines can cause the immune system to react as if the body were actually being infected, and general infection symptoms (many cold and flu symptoms are just general infection symptoms) can appear, though these symptoms are usually not as severe or long-lasting as influenza. The most dangerous side-effect is a severe allergic reaction to either the virus material itself, or residues from the hen eggs used to grow the influenza; however, these reactions are extremely rare.[62]

Good personal health and hygiene habits are reasonably effective in avoiding and minimizing influenza. Since influenza spreads through aerosols and contact with contaminated surfaces, it is important to persuade people to cover their mouths while sneezing and to wash their hands regularly.[61]

Treatment

People with the flu are advised to get plenty of rest, drink a lot of liquids, avoid using alcohol and tobacco and, if necessary, take medications such as acetaminophen (paracetamol) to relieve the fever and muscle aches associated with the flu. Children and teenagers with flu symptoms (particularly fever) should avoid taking aspirin during an influenza infection (especially influenza type B) because doing so can lead to Reye syndrome, a rare but potentially fatal disease of the liver.[63]

Since influenza is caused by a virus, antibiotics have no effect on the infection, but may be prescribed if the influenza causes secondary infections such as bacterial pneumonia. Antiviral medication is sometimes effective, but viruses can develop resistance to the standard antiviral drugs. The antiviral drugs amantadine and rimantadine are designed to block a viral ion channel and prevent the virus from infecting cells. These drugs are sometimes effective against influenza A if given early in the infection, but are always ineffective against influenza B.[64] Measured resistance to amantadine and rimantadine in American isolates of H3N2 has increased to 91% in 2005.[65] Antiviral drugs such as oseltamivir (trade name Tamiflu) and zanamivir (trade name Relenza) are neuraminidase inhibitors that are designed to halt the spread of the virus in the body.[66] These drugs are often effective against both influenza A and B.[64] Different strains of influenza virus have differing degrees of resistance against these antivirals and it is impossible to predict what degree of resistance a future pandemic strain might have.

Research

Research on influenza includes studies on molecular virology, how the virus produces disease (pathogenesis), host immune responses, viral genomics, and how the virus spreads (epidemiology). These studies help in developing influenza countermeasures; for example, a better understanding of the body's immune response aids in vaccine development, and a detailed picture of how influenza invades cells aids in the development of antiviral drugs. One important basic research program is the Influenza Genome Sequencing Project, which is creating a library of influenza sequences; this library should help to clarify which factors make one strain more lethal than another, which genes most affect immunogenicity, and how the virus evolves over time.[67]

Research into new vaccines is particularly important: as current vaccines are slow and expensive to produce and must be reformulated every year. The sequencing of the influenza genome and recombinant DNA technology may accelerate the generation of new vaccine strains by allowing scientists to substitute new antigens into a previously-developed vaccine strain.[68] New technologies are also being developed to grow virus in cell culture; which promises higher yields, less cost, better quality and surge capacity.[69] The US government has purchased from Sanofi Pasteur and Chiron Corporation several million doses of vaccine meant to be used in case of an influenza pandemic of H5N1 avian influenza and is conducting clinical trials with these vaccines.[70]

Infection in other animals

|

Influenza infects many animal species and transfer of viral strains between species can occur. Birds are thought to be the main animal reservoirs of influenza viruses.[71] Sixteen forms of hemagglutinin and 9 forms of neuraminidase have been identified. All known subtypes (HxNy) are found in birds but many subtypes are endemic in humans, dogs, horses, and pigs; populations of camels, ferrets, cats, seals, mink, and whales also show evidence of prior infection or exposure to influenza.[27] Variants of flu virus are sometimes named according to the species the strain is endemic in or adapted to. The main variants named using this convention are: Bird flu, Human Flu, Swine Flu, Horse Flu and Dog Flu. In pigs, horses and dogs influenza symptoms are similar to humans, with cough, fever and loss of appetite.[27] The frequency of animal diseases are not as well-studied as human infection, but an outbreak of influenza in harbour seals caused approximately 500 seal deaths off the New England coast in 1979-1980.[72] On the other hand, outbreaks in pigs are common and do not cause severe mortality.[27]

Flu symptoms in birds are variable and can be unspecific.[73] The symptoms following infection with low-pathogenicity avian influenza may be as mild as ruffled feathers, a small reduction in egg production or weight loss combined with minor respiratory disease.[74] Since these mild symptoms can make diagnosis in the field difficult, tracking the spread of avian influenza requires laboratory testing of samples from infected birds. Some strains such as Asian H9N2 are highly virulent to poultry, and may cause more extreme symptoms and significant mortality.[75] In its most highly pathogenic form, influenza in chickens and turkeys produces a sudden appearance of severe symptoms and almost 100 % mortality within two days.[76] As the virus spreads rapidly in the crowded conditions seen in the intensive farming of chickens and turkeys, these outbreaks can cause large economic losses to poultry farmers.

An avian-adapted, highly pathogenic strain of H5N1 (called HPAI A(H5N1), for "highly pathogenic avian influenza virus of type A of subtype H5N1") causes H5N1 flu, commonly known as "avian influenza" or simply "bird flu", and is endemic in many bird populations, especially in Southeast Asia. This Asian lineage strain of HPAI A(H5N1) is spreading globally. It is epizootic (an epidemic in non-humans) and panzootic (a disease affecting animals of many species, especially over a wide area) killing tens of millions of birds and spurring the culling of hundreds of millions of other birds in an attempt to control its spread. Most references in the media to "bird flu" and most references to H5N1 are about this specific strain.[77][78]

At present, HPAI A(H5N1) is an avian disease and there is no evidence suggesting efficient human-to-human transmission of HPAI A(H5N1). In almost all cases, those infected have had extensive physical contact with infected birds.[79] In the future, H5N1 may mutate or reassort into a strain capable of efficient human-to-human transmission. Due to its high lethality and virulence, its endemic presence, its large and increasing biological host reservoir, the H5N1 virus is the world's pandemic threat in the 2006-7 flu season, and billions of dollars are being raised and spent researching H5N1 and preparing for a potential influenza pandemic.[80]

Economic impact

Influenza produces direct costs due to lost productivity and associated medical treatment, as well as indirect costs of preventative measures. In the United States influenza is responsible for a total cost of over $10 billion per year, while it has been estimated that a future pandemic could cause hundreds of billions of dollars in direct and indirect costs.[81] However, the economic impact of past pandemics have not been intensively studied and some authors have suggested that the Spanish influenza actually had a positive long-term effect on per-capita income growth, despite a large reduction in the working population and severe short-term depressive effects.[82] Other studies have attempted to predict the costs of a pandemic as serious as the 1918 Spanish flu on the U.S. economy, where 30 percent of all workers became ill, and 2.5 percent were killed. A 30 percent sickness rate and a three-week length of illness would decrease gross domestic product by 5 percent. Additional costs would come from medical treatment of 18 million to 45 million people, and total economic costs would be approximately $700 billion.[83]

Preventative costs are also high. Governments worldwide have spent billions of U.S. dollars preparing and planning for a potential H5N1 avian influenza pandemic: with costs associated with purchasing drugs and vaccines as well as developing disaster drills and strategies for improved border controls.[80] On November 1 2005 President George Bush unveiled the National Strategy To Safeguard Against The Danger of Pandemic Influenza[84] backed by a request to Congress for 7.1 billion U.S. dollars to begin implementing the plan.[85] Internationally, on January 18 2006 donor nations pledged two billion U.S. dollars to combat bird flu at the two day International Pledging Conference on Avian and Human Influenza held in China.[86]

Up to 2006, over ten billion dollars have been spent and over two hundred million birds have been killed to try to contain H5N1 avian influenza.[87] However, as these efforts have been largely ineffective at controlling the spread of the virus, other approaches are being tried: for example, the Vietnamese government in 2005 adopted a combination of mass poultry vaccination, disinfecting, culling, information campaigns and bans on live poultry in cities.[88] As a result of such measures, the cost of poultry farming has increased, while the cost to consumers has gone down due to demand for poultry falling below supply. This has resulted in devastating losses for many farmers. Poor poultry farmers can not afford mandated measures keeping their bird livestock from contact with wild birds (and other measures) thus risking losing their livelihood altogether. Multinational poultry farming is increasingly becoming unprofitable as H5N1 avian influenza becomes endemic in wild birds worldwide.[89] Financial ruin for poor poultry farmers, that can be as severe as threatening starvation, has caused some to commit suicide and many others to stop cooperating with efforts to deal with this virus; further increasing the human toll, the spread of the disease and the chances of a pandemic mutation.[90][91]

See also

- Information concerning flu research can be found at

- Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research

- H5N1 genetic structure

- ICEID

- Influenza Genome Sequencing Project

- Cytokine storm

- International Partnership on Avian and Pandemic Influenza

- National Influenza Centers

- Pandemic Preparedness and Response Act

References and notes

- ^ a b Merck Manual Home Edition. "Influenza: Viral Infections".

- ^ a b c Eccles R (2005). "Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza". Lancet Infect Dis. 5 (11): 718–25. PMID 16253889.

- ^ Suarez D, Spackman E, Senne D, Bulaga L, Welsch A, Froberg K (2003). "The effect of various disinfectants on detection of avian influenza virus by real time RT-PCR". Avian Dis. 47 (3 Suppl): 1091–5. PMID 14575118.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Avian influenza (" bird flu")". WHO. February 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-20. - Fact sheet

- ^ WHO position paper : influenza vaccines WHO weekly Epidemiological Record 19 August 2005, vol. 80, 33 (pp 277-288)

- ^ Villegas P (1998). "Viral diseases of the respiratory system". Poult Sci. 77 (8): 1143–5. PMID 9706079.

- ^ Horwood F, Macfarlane J. "Pneumococcal and influenza vaccination: current situation and future prospects" (PDF). Thorax. 57 Suppl 2: II24–II30. PMID 12364707.

- ^ Harper D. "Influenza". etymonline.com - Online etymology dictionary.

- ^ Smith P. Online dictionary of archaic medical terms. Accessed 23 Oct 06 "Archaic Medical Terms".

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Martin P, Martin-Granel E (2006). "2,500-year evolution of the term epidemic". Emerg Infect Dis. 12 (6). PMID 16707055.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hippocrates. "Of the Epidemics" (written 400 BCE and translated by Francis Adams). Retrieved 2006-10-18.

- ^ a b c Potter CW (2006). "A History of Influenza". J Appl Microbiol. 91 (4): 572–579. PMID 11576290.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Patterson KD, Pyle GF. (1991). "The geography and mortality of the 1918 influenza pandemic". Bull Hist Med. 65 (1): 4–21. PMID 2021692.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Knobler S, Mack A, Mahmoud A, Lemon S (Editors) (ed.). "Chapter 1: The Story of Influenza". The Threat of Pandemic Influenza: Are We Ready? Workshop Summary (2005). Washington DC: The National Academies Press. pp. p60.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help);|pages=has extra text (help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ a b c Taubenberger J, Reid A, Janczewski T, Fanning T (2001). "Integrating historical, clinical and molecular genetic data in order to explain the origin and virulence of the 1918 Spanish influenza virus". Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 356 (1416): 1829–39. PMID 11779381.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Simonsen L, Clarke M, Schonberger L, Arden N, Cox N, Fukuda K (1998). "Pandemic versus epidemic influenza mortality: a pattern of changing age distribution". J Infect Dis. 178 (1): 53–60. PMID 9652423.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Taubenberger J, Morens D (2006). "1918 Influenza: the mother of all pandemics". Emerg Infect Dis. 12 (1): 15–22. PMID 16494711.

- ^ a b c d e f Hilleman M (2002). "Realities and enigmas of human viral influenza: pathogenesis, epidemiology and control". Vaccine. 20 (25–26): 3068–87. PMID 12163258.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Shimizu K. (1997). "History of influenza epidemics and discovery of influenza virus". Nippon Rinsho. 55 (10): 2505–201. PMID 9360364.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Smith W, Andrewes CH, Laidlaw PP. (1933). "A virus obtained from influenza patients". Lancet. 2 pages = 66-68.

{{cite journal}}: Missing pipe in:|volume=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet: Biography The Nobel Foundation. Accessed 22 Oct 06

- ^ Kendall H (2006). "Vaccine Innovation: Lessons from World War II" (PDF). Journal of Public Health Policy. 27 (1): 38–57.

- ^ a b c d Hay A, Gregory V, Douglas A, Lin Y (2001). "The evolution of human influenza viruses" (PDF). Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 356 (1416): 1861–70. PMID 11779385.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fouchier R, Schneeberger P, Rozendaal F, Broekman J, Kemink S, Munster V, Kuiken T, Rimmelzwaan G, Schutten M, Van Doornum G, Koch G, Bosman A, Koopmans M, Osterhaus A (2004). "Avian influenza A virus (H7N7) associated with human conjunctivitis and a fatal case of acute respiratory distress syndrome". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 101 (5): 1356–61. PMID 14745020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Osterhaus A, Rimmelzwaan G, Martina B, Bestebroer T, Fouchier R (2000). "Influenza B virus in seals". Science. 288 (5468): 1051–3. PMID 10807575.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nobusawa E, Sato K (2006). "Comparison of the mutation rates of human influenza A and B viruses". J Virol. 80 (7): 3675–8. PMID 16537638.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Webster R, Bean W, Gorman O, Chambers T, Kawaoka Y (1992). "Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses". Microbiol Rev. 56 (1): 152–79. PMID 1579108.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zambon M (1999). "Epidemiology and pathogenesis of influenza". J Antimicrob Chemother. 44 Suppl B: 3–9. PMID 10877456.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Matsuzaki Y, Sugawara K, Mizuta K, Tsuchiya E, Muraki Y, Hongo S, Suzuki H, Nakamura K (2002). "Antigenic and genetic characterization of influenza C viruses which caused two outbreaks in Yamagata City, Japan, in 1996 and 1998". J Clin Microbiol. 40 (2): 422–9. PMID 11825952.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Matsuzaki Y, Katsushima N, Nagai Y, Shoji M, Itagaki T, Sakamoto M, Kitaoka S, Mizuta K, Nishimura H (2006). "Clinical features of influenza C virus infection in children". J Infect Dis. 193 (9): 1229–35. PMID 16586359.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Katagiri S, Ohizumi A, Homma M (1983). "An outbreak of type C influenza in a children's home". J Infect Dis. 148 (1): 51–6. PMID 6309999.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses descriptions of: Orthomyxoviridae Influenzavirus B Influenzavirus C

- ^ International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. "The Universal Virus Database, version 4: Influenza A".

- ^ Ghedin E, Sengamalay N, Shumway M, Zaborsky J, Feldblyum T, Subbu V, Spiro D, Sitz J, Koo H, Bolotov P, Dernovoy D, Tatusova T, Bao Y, St George K, Taylor J, Lipman D, Fraser C, Taubenberger J, Salzberg S (2005). "Large-scale sequencing of human influenza reveals the dynamic nature of viral genome evolution". Nature. 437 (7062): 1162–6. PMID 16208317.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Suzuki Y (2005). "Sialobiology of influenza: molecular mechanism of host range variation of influenza viruses". Biol Pharm Bull. 28 (3): 399–408. PMID 15744059.

- ^ Wilson J, von Itzstein M (2003). "Recent strategies in the search for new anti-influenza therapies". Curr Drug Targets. 4 (5): 389–408. PMID 12816348.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Wagner R, Matrosovich M, Klenk H (2002). "Functional balance between haemagglutinin and neuraminidase in influenza virus infections". Rev Med Virol. 12 (3): 159–66. PMID 11987141.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lakadamyali M, Rust M, Babcock H, Zhuang X (2003). "Visualizing infection of individual influenza viruses". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 100 (16): 9280–5. PMID 12883000.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cros J, Palese P (2003). "Trafficking of viral genomic RNA into and out of the nucleus: influenza, Thogoto and Borna disease viruses". Virus Res. 95 (1–2): 3–12. PMID 12921991.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kash J, Goodman A, Korth M, Katze M (2006). "Hijacking of the host-cell response and translational control during influenza virus infection". Virus Res. 119 (1): 111–20. PMID 16630668.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nayak D, Hui E, Barman S (2004). "Assembly and budding of influenza virus". Virus Res. 106 (2): 147–65. PMID 15567494.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Drake J (1993). "Rates of spontaneous mutation among RNA viruses". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 90 (9): 4171–5. PMID 8387212.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Monto A, Gravenstein S, Elliott M, Colopy M, Schweinle J (2000). "Clinical signs and symptoms predicting influenza infection". Arch Intern Med. 160 (21): 3243–7. PMID 11088084.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Peter M. Sandman and Jody Lanard "Bird Flu: Communicating the Risk" 2005 Perspectives in Health Magazine Vol. 10 issue 2.

- ^ a b Key Facts about Influenza (Flu) Vaccine CDC publication. Published October 17, 2006. Accessed 18 Oct 2006.

- ^ Angelo SJ, Marshall PS, Chrissoheris MP, Chaves AM. "Clinical characteristics associated with poor outcome in patients acutely infected with Influenza A." Conn Med. 2004 Apr;68(4):199-205. PMID 15095826

- ^ Murin S, Bilello K (2005). "Respiratory tract infections: another reason not to smoke". Cleve Clin J Med. 72 (10): 916–20. PMID 16231688.

- ^ Schmitz N, Kurrer M, Bachmann M, Kopf M (2005). "Interleukin-1 is responsible for acute lung immunopathology but increases survival of respiratory influenza virus infection". J Virol. 79 (10): 6441–8. PMID 15858027.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Winther B, Gwaltney J, Mygind N, Hendley J. "Viral-induced rhinitis". Am J Rhinol. 12 (1): 17–20. PMID 9513654.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b WHO Confirmed Human Cases of H5N1 Data published by WHO Epidemic and Pandemic Alert and Response (EPR). Accessed 24 Oct. 2006

- ^ a b Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2006–2007 influenza season WHO report 2006-02-14. Accessed 19 October 2006.

- ^ Weather and the Flu Season NPR Day to Day, December 17 2003. Accessed, 19 October 2006

- ^ Shek LP, Lee BW. "Epidemiology and seasonality of respiratory tract virus infections in the tropics." Paediatr Respir Rev. 2003 Jun;4(2):105-11. PMID 12758047

- ^ Dushoff J, Plotkin JB, Levin SA, Earn DJ. "Dynamical resonance can account for seasonality of influenza epidemics." Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 30 November2004;101(48):16915-6. PMID 15557003

- ^ Influenza WHO Fact sheet N°211 Revised March 2003. Accessed 22 October 2006

- ^ Thompson W, Shay D, Weintraub E, Brammer L, Cox N, Anderson L, Fukuda K (2003). "Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States". JAMA. 289 (2): 179–86. PMID 12517228.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Long intervals of stasis punctuated by bursts of positive selection in the seasonal evolution of influenza A virus". Biol Direct. 1 (1): 34. 2006. PMID 17067369.

- ^ Parrish C, Kawaoka Y. "The origins of new pandemic viruses: the acquisition of new host ranges by canine parvovirus and influenza A viruses". Annu Rev Microbiol. 59: 553–86. PMID 16153179.

- ^ Capua I, Alexander D (2006). "The challenge of avian influenza to the veterinary community" (PDF). Avian Pathol. 35 (3): 189–205. PMID 16753610.

- ^ Holmes E, Ghedin E, Miller N, Taylor J, Bao Y, St George K, Grenfell B, Salzberg S, Fraser C, Lipman D, Taubenberger J (2005). "Whole-genome analysis of human influenza A virus reveals multiple persistent lineages and reassortment among recent H3N2 viruses". PLoS Biol. 3 (9): e300. PMID 16026181.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Prevention and Control of Influenza: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) CDC report (MMWR 2006 Jul 28;55(RR10):1-42) Accessed 19 Oct 06.

- ^ Questions & Answers: Flu Shot CDC publication Updated Jul 24, 2006. Accessed 19 Oct 06.

- ^ Glasgow J, Middleton B (2001). "Reye syndrome--insights on causation and prognosis". Arch Dis Child. 85 (5): 351–3. PMID 11668090.

- ^ a b Stephenson I, Nicholson K (1999). "Chemotherapeutic control of influenza". J Antimicrob Chemother. 44 (1): 6–10. PMID 10459804.

- ^ "High levels of adamantane resistance among influenza A (H3N2) viruses and interim guidelines for use of antiviral agents--United States, 2005-06 influenza season". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 55 (2): 44–6. 2006. PMID 16424859.

- ^ Moscona A (2005). "Neuraminidase inhibitors for influenza". N Engl J Med. 353 (13): 1363–73. PMID 16192481.

- ^ Influenza A Virus Genome Project at The Institute of Genomic Research. Accessed 19 Oct 06

- ^ Subbarao K, Katz J. "Influenza vaccines generated by reverse genetics". Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 283: 313–42. PMID 15298174.

- ^ Bardiya N, Bae J (2005). "Influenza vaccines: recent advances in production technologies". Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 67 (3): 299–305. PMID 15660212.

- ^ New York Times article ""Doubt Cast on Stockpile of a Vaccine for Bird Flu"" by Denise Grady. Published: March 30, 2006. Accessed 19 Oct 06

- ^ Gorman O, Bean W, Kawaoka Y, Webster R (1990). "Evolution of the nucleoprotein gene of influenza A virus". J Virol. 64 (4): 1487–97. PMID 2319644.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hinshaw V, Bean W, Webster R, Rehg J, Fiorelli P, Early G, Geraci J, St Aubin D (1984). "Are seals frequently infected with avian influenza viruses?". J Virol. 51 (3): 863–5. PMID 6471169.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Elbers A, Koch G, Bouma A (2005). "Performance of clinical signs in poultry for the detection of outbreaks during the avian influenza A (H7N7) epidemic in The Netherlands in 2003". Avian Pathol. 34 (3): 181–7. PMID 16191700.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Capua I, Mutinelli F. "Low pathogenicity (LPAI) and highly pathogenic (HPAI) avian influenza in turkeys and chicken." In: Capua I, Mutinelli F. (eds.), A Colour Atlas and Text on Avian Influenza, Papi Editore, Bologna, 2001, pp. 13-20

- ^ Bano S, Naeem K, Malik S (2003). "Evaluation of pathogenic potential of avian influenza virus serotype H9N2 in chickens". Avian Dis. 47 (3 Suppl): 817–22. PMID 14575070.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Swayne D, Suarez D (2000). "Highly pathogenic avian influenza". Rev Sci Tech. 19 (2): 463–82. PMID 10935274.

- ^ Li K, Guan Y, Wang J, Smith G, Xu K, Duan L, Rahardjo A, Puthavathana P, Buranathai C, Nguyen T, Estoepangestie A, Chaisingh A, Auewarakul P, Long H, Hanh N, Webby R, Poon L, Chen H, Shortridge K, Yuen K, Webster R, Peiris J (2004). "Genesis of a highly pathogenic and potentially pandemic H5N1 influenza virus in eastern Asia". Nature. 430 (6996): 209–13. PMID 15241415.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Li KS, Guan Y, Wang J, Smith GJ, Xu KM, Duan L, Rahardjo AP, Puthavathana P, Buranathai C, Nguyen TD, Estoepangestie AT, Chaisingh A, Auewarakul P, Long HT, Hanh NT, Webby RJ, Poon LL, Chen H, Shortridge KF, Yuen KY, Webster RG, Peiris JS. "The Threat of Pandemic Influenza: Are We Ready?" Workshop Summary The National Academies Press (2005) "Today's Pandemic Threat: Genesis of a Highly Pathogenic and Potentially Pandemic H5N1 Influenza Virus in Eastern Asia", pages 116-130

- ^ Liu J (2006). "Avian influenza--a pandemic waiting to happen?" (PDF). J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 39 (1): 4–10. PMID 16440117.

- ^ a b Rosenthal, E. and Bradsher, K. Is Business Ready for a Flu Pandemic? The New York Times 16-03-2006 Accessed 17-04-2006

- ^ Statement from President George Bush on Influenza Accessed 26 Oct 2006

- ^ Brainerd, E. and M. Siegler (2003), “The Economic Effects of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic”, CEPR Discussion Paper, no. 3791.

- ^ Poland G (2006). "Vaccines against avian influenza--a race against time". N Engl J Med. 354 (13): 1411–3. PMID 16571885.

- ^ National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza Whitehouse.gov Accessed 26 Oct 2006.

- ^ Bush Outlines $7 Billion Pandemic Flu Preparedness Plan State.gov. Accessed 26 Oct 2006

- ^ Donor Nations Pledge $1.85 Billion to Combat Bird Flu Newswire Accessed 26 Oct 2006.

- ^ Avian Influenza and its Global Implications US AID. Accessed 26 Oct 2006.

- ^ Reuters Vietnam to unveil advanced plan to fight bird flu published on April 28, 2006. Accessed 26 Oct 2006

- ^ Poultry sector suffers despite absence of bird flu UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Accessed 26 Oct 2006

- ^ Nine poultry farmers commit suicide in flu-hit India Reuters. Published on April 12, 2006. Accessed 26 Oct 2006.

- ^ In the Nile Delta, Bird Flu Preys on Ignorance and Poverty New York Times. Published on April 13, 2006. Accessed 26 Oct 2006.

Further reading

|

General

History

Microbiology

|

Pathogenesis

Epidemiology

Treatment and prevention

Research

|

External links

- CDC info on influenza

- World Health Organization Fact Sheet Overview of influenza.

- NHS Direct Health encyclopedia entry

- BioHealthBase Bioinformatics Resource Center Database of influenza sequences and related information.

- Medicine Net's overview of influenza

- Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding Influenza Law related government reports.

- Influenza Surveillance and Contingency Plans (by Country/Region)

- Orthomyxoviridae The Universal Virus Database of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses.

- Influenza Virus Resource from the NCBI.

- 'Myxoviruses' Microbiology at the University of Leicester.