more accurate |

Undid revision 478354923 by Zenkai251 (talk) Believing something and stating something are not the same, I can "note" something that I don't believe. |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

The '''Genesis creation narrative''' is the [[creation myth]] contained in the first two chapters of the [[Book of Genesis]], the first book of the [[Hebrew Bible]] (the [[Old Testament]] of the [[Christian Bible]]). Chapter one describes the creation of the world by [[Elohim]] ([[Hebrew language|Hebrew]] for "[[God]]") in six days by means of divine speech, culminating in the creation of [[mankind]], with God resting on, blessing and sanctifying the [[Shabbat|seventh day]]. Chapter two describes [[YHWH]]—the [[Yahweh|personal name]] of the [[God of Israel]]—forming the first man ([[Adam (Bible)|Adam]]) from dust, placing him in the [[Garden of Eden]], and making the first woman ([[Eve (Bible)|Eve]]) from his side. |

The '''Genesis creation narrative''' is the [[creation myth]] contained in the first two chapters of the [[Book of Genesis]], the first book of the [[Hebrew Bible]] (the [[Old Testament]] of the [[Christian Bible]]). Chapter one describes the creation of the world by [[Elohim]] ([[Hebrew language|Hebrew]] for "[[God]]") in six days by means of divine speech, culminating in the creation of [[mankind]], with God resting on, blessing and sanctifying the [[Shabbat|seventh day]]. Chapter two describes [[YHWH]]—the [[Yahweh|personal name]] of the [[God of Israel]]—forming the first man ([[Adam (Bible)|Adam]]) from dust, placing him in the [[Garden of Eden]], and making the first woman ([[Eve (Bible)|Eve]]) from his side. |

||

[[Nahum Sarna]] |

[[Nahum Sarna]] notes that the [[Israelites]] borrowed some [[Mesopotamian mythology|Mesopotamian]] themes but adapted them to [[God in Judaism|their belief in one God]] as expressed by the ''[[shema]]''.{{sfn|Sarna|1997|p=50}} [[Robert Alter]] describes the combined narrative as "compelling in its archetypal character, its adaptation of myth to [[monotheist]]ic ends".{{sfn|Alter|2004|p=xii}} |

||

In Genesis 1 God creates by spoken command, suggesting a comparison with a king, who has only to speak for things to happen.{{sfn|Bandstra|1999|p=39}} Each command is followed by naming. In the ancient Near East naming was bound up with the act of creating: thus in Egyptian literature the [[creator god]] pronounced the names of everything: the ''[[Enuma Elish]]'' begins at the point where nothing has yet been named.{{sfn|Walton|2003|p=158}} The Hebrew [[verb]] used to describe God's creative act is ''bara'', which is used only with God as its [[Subject (grammar)|subject]]. No creature, including [[Human|man]], is ever the subject of the verb ''bara'', but only the [[Object (grammar)|object]]. According to [[John H. Walton (theologian)|John Walton]], ''bara'' concerns not the creation of matter ''[[ex nihilo]]'' (from nothing), but the ordering of functions and roles.{{sfn|Walton|2006|p=183}} [[Walter Brueggemann]] says that it can be interpreted both as referring to creation ''ex nihilo'' and the ordering of functions and roles, and that the grammatical evidence for either view is inconclusive.<ref>{{harvnb|Brueggemann|1982|p=29}}. "The familiar statement of verse 1 admits more of more than one rendering. The conventional translation (supported by Isa 46:10) makes a claim for creation as an absolute and decisive act of God. But it may be a dependent temporal clause ("when God began to create"): it then relates closely to what follows, and creation is understood to be an ongoing work which God has begun and continues. The evidence of the grammar is not decisive, and either rendering is possible."</ref> In any case, he concludes, the Genesis creation narrative emphasizes [[monotheism]] and the [[Divine providence|providence]] of God, and that we need not choose between the two exegetical options, just as the text itself does not: creation ''ex nihilo'' emphasizes the majestic and transcendent power of God, while the ordering of pre-existent material emphasizes the providence of God.<ref>{{harvnb|Brueggemann|1982|pp=29-30}}. "The very ambiguity of ''creation from nothing'' and ''creation from chaos'' is a rich expository possibility. We need not choose between them, even as the text does not...The former asserts the majestic and exclusive power of God. The latter asserts that even the way life is can be claimed by God. By the double focus on the power of God and the use made of chaos, the text affirms the difference between God and creature."</ref> Traditional or conservative [[exegete]]s in the [[Judaeo-Christian]] tradition state that ''bara'' indeed does refer to a creation ''ex nihilo''.{{sfn|Wenham|1987|p=352}} |

In Genesis 1 God creates by spoken command, suggesting a comparison with a king, who has only to speak for things to happen.{{sfn|Bandstra|1999|p=39}} Each command is followed by naming. In the ancient Near East naming was bound up with the act of creating: thus in Egyptian literature the [[creator god]] pronounced the names of everything: the ''[[Enuma Elish]]'' begins at the point where nothing has yet been named.{{sfn|Walton|2003|p=158}} The Hebrew [[verb]] used to describe God's creative act is ''bara'', which is used only with God as its [[Subject (grammar)|subject]]. No creature, including [[Human|man]], is ever the subject of the verb ''bara'', but only the [[Object (grammar)|object]]. According to [[John H. Walton (theologian)|John Walton]], ''bara'' concerns not the creation of matter ''[[ex nihilo]]'' (from nothing), but the ordering of functions and roles.{{sfn|Walton|2006|p=183}} [[Walter Brueggemann]] says that it can be interpreted both as referring to creation ''ex nihilo'' and the ordering of functions and roles, and that the grammatical evidence for either view is inconclusive.<ref>{{harvnb|Brueggemann|1982|p=29}}. "The familiar statement of verse 1 admits more of more than one rendering. The conventional translation (supported by Isa 46:10) makes a claim for creation as an absolute and decisive act of God. But it may be a dependent temporal clause ("when God began to create"): it then relates closely to what follows, and creation is understood to be an ongoing work which God has begun and continues. The evidence of the grammar is not decisive, and either rendering is possible."</ref> In any case, he concludes, the Genesis creation narrative emphasizes [[monotheism]] and the [[Divine providence|providence]] of God, and that we need not choose between the two exegetical options, just as the text itself does not: creation ''ex nihilo'' emphasizes the majestic and transcendent power of God, while the ordering of pre-existent material emphasizes the providence of God.<ref>{{harvnb|Brueggemann|1982|pp=29-30}}. "The very ambiguity of ''creation from nothing'' and ''creation from chaos'' is a rich expository possibility. We need not choose between them, even as the text does not...The former asserts the majestic and exclusive power of God. The latter asserts that even the way life is can be claimed by God. By the double focus on the power of God and the use made of chaos, the text affirms the difference between God and creature."</ref> Traditional or conservative [[exegete]]s in the [[Judaeo-Christian]] tradition state that ''bara'' indeed does refer to a creation ''ex nihilo''.{{sfn|Wenham|1987|p=352}} |

||

Revision as of 01:57, 23 February 2012

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Creationism | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| History | ||||

| Types | ||||

| Biblical cosmology | ||||

| Creation science | ||||

| Rejection of evolution by religious groups | ||||

| Religious views | ||||

|

||||

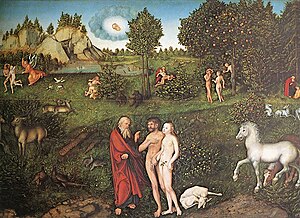

The Genesis creation narrative is the creation myth contained in the first two chapters of the Book of Genesis, the first book of the Hebrew Bible (the Old Testament of the Christian Bible). Chapter one describes the creation of the world by Elohim (Hebrew for "God") in six days by means of divine speech, culminating in the creation of mankind, with God resting on, blessing and sanctifying the seventh day. Chapter two describes YHWH—the personal name of the God of Israel—forming the first man (Adam) from dust, placing him in the Garden of Eden, and making the first woman (Eve) from his side.

Nahum Sarna notes that the Israelites borrowed some Mesopotamian themes but adapted them to their belief in one God as expressed by the shema.[1] Robert Alter describes the combined narrative as "compelling in its archetypal character, its adaptation of myth to monotheistic ends".[2]

In Genesis 1 God creates by spoken command, suggesting a comparison with a king, who has only to speak for things to happen.[3] Each command is followed by naming. In the ancient Near East naming was bound up with the act of creating: thus in Egyptian literature the creator god pronounced the names of everything: the Enuma Elish begins at the point where nothing has yet been named.[4] The Hebrew verb used to describe God's creative act is bara, which is used only with God as its subject. No creature, including man, is ever the subject of the verb bara, but only the object. According to John Walton, bara concerns not the creation of matter ex nihilo (from nothing), but the ordering of functions and roles.[5] Walter Brueggemann says that it can be interpreted both as referring to creation ex nihilo and the ordering of functions and roles, and that the grammatical evidence for either view is inconclusive.[6] In any case, he concludes, the Genesis creation narrative emphasizes monotheism and the providence of God, and that we need not choose between the two exegetical options, just as the text itself does not: creation ex nihilo emphasizes the majestic and transcendent power of God, while the ordering of pre-existent material emphasizes the providence of God.[7] Traditional or conservative exegetes in the Judaeo-Christian tradition state that bara indeed does refer to a creation ex nihilo.[8]

In Genesis 2 the Hebrew word used when God formed the first man is yatsar, meaning "fashioned", a verb used in contexts such as a potter forming a pot from clay.[9] God breathed his own breath of life into the man and he became a living soul, Hebrew nepesh, a word meaning life, vitality, or the living personality; man shares nepesh with all creatures, but only of man is this life-giving act of God described.[10]

A common hypothesis among biblical scholars today is that the first major comprehensive draft of the Pentateuch (the series of five books which begins with Genesis and ends with Deuteronomy) was composed in the late 7th or the 6th century BC by the Jahwist source and that this was later expanded by the addition of various narratives and laws by the Priestly source into a work very like the one we have today.[11] In the narrative the two sources appear in reverse order: according to the most prevalent delineation of the sources, Genesis 1 is Priestly and Genesis 2 is Jahwistic. In their view, its over-riding purpose is to establish a monotheistic creation in opposition to the polytheistic creation myth of Israel's historic enemy, Babylon.[12] Professor R.N. Whybray, discussing the themes of Genesis in the Oxford Bible Commentary, writes that the Primeval Narrative (Genesis 1-11), introduces a supreme and single God who creates a world which is "good"; later, mankind will rebel against this God, bringing on the catastrophe of the Flood, to be followed in due course by the more hopeful destiny of a human race blessed through Abraham.[13]

Structure and summary

Structure

The creation narrative is made up of two parts, roughly equivalent to the two first chapters of the Book of Genesis.

While Genesis 2 is a simple linear narrative proceeding from God's forming the first man through the Garden of Eden to the creation of the first woman and the institution of marriage, Genesis 1 is notable for its elaborate internal structure. It consists of eight acts of creation over six days, framed by an introduction and a conclusion. In each of the first three days there is an act of division: day one divides the darkness from light, day two the "waters above" from the "waters below", and day three the sea from the land. In each of the next three days these divisions are populated: day four populates the darkness and light with sun, moon and stars; day five populates seas and skies with fish and fowl; and finally land-based creatures and mankind to populate the land.[14]

According to David M. Carr there are significant parallels between the two stories, but also significant differences: in the first account mankind (male and female) are created after animals, while in the second the man is created first, then animals, and "finally the woman as the climax of creation."[15] Carr further notes: "Together this combination of parallel character and contrasting profile point to the different origin of materials in Genesis 1:1–1:2–3 and 2:4b–3:23, however elegantly they have now been combined."[15]

The two are joined by Genesis 2:4a, "These are the generations of the heavens and of the earth when they were created." This echoes the first line of Genesis 1, "In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth", and is reversed in the next phrase, Genesis 2:4b, "...in the day that the LORD God made the earth and the heavens". The full significance of this is unclear, but it does reflect the preoccupation of each chapter, Genesis 1 looking down from heaven, Genesis 2 looking up from the earth, according to Friedman.[16]

Chapter one – General creation

- Opening: "In the beginning...".Gen 1:1

- First day: Light is commanded to appear ("Let there be light!") The light is divided from the darkness, and they are named "day" and "night".Gen 1:3

- Second day: God makes a firmament ("Let a firmament be...!")—the second command—to divide the waters above from the waters below. The firmament is named "skies".Gen 1:6–7

- Third day: God commands the waters below to be gathered together in one place, and dry land to appear (the third command)."earth" and "sea" are named. God commands the earth to bring forth grass, plants, and fruit-bearing trees (the fourth command).Gen 1:9–10

- Fourth day: God puts lights in the firmament (the fifth command) to separate light from darkness and to mark days, seasons and years. Two great lights are made to appear (most likely the Sun and Moon, but not named), and the stars.Gen 1:14–15

- Fifth day: God commands the sea to "teem with living creatures", and birds to fly across the heavens (sixth command) He creates birds and sea creatures, and commands them to be fruitful and multiply.Gen 1:20–21

- Sixth day: God commands the land to bring forth living creatures (seventh command);Gen 1:24–25 He makes wild beasts, livestock and reptiles. He then creates humanity in His "image" and "likeness" (eighth command). They are commanded to "be fruitful, and multiply, and fill the earth, and subdue it." The totality of creation is described by God as "very good."Gen 1:26–28

- Seventh day: "Thus the heavens and the earth were finished, and all the host of them." God, having completed the heavens and the earth, rests from His work, and blesses and sanctifies the seventh day.Gen 2:1–3

Literary bridge

"These are the generations of the heavens and of the earth when they were created, in the day that the LORD God made the earth and the heavens,". (Genesis 2:4) The opening of verse 2:4 provides a "bridge" connecting the two accounts of the creation narrative. More than just a bridge, this verse is the first of ten "generations" (Hebrew tôledôt) phrases used throughout Genesis, which provide a literary structure to the book.[17] They function as headings to what comes after, but the position of this, the first example, has been the subject of much debate.[18]

Chapter two – Special creation

- Genesis 2:4b places events "in the day when YHWH Elohim made the earth and the heavens...."

- "...before any plant had appeared, before any rain had fallen, while a spring watered the earth," Yahweh forms the man (Heb. ha-adam הָאָדָם) out of dust from the ground (Heb. ha-adamah הָאֲדָמָה), and breaths the breath of life into his nostrils, "and the man became a living being."

- Yahweh plants a garden in Eden and sets the man in it, and causes pleasant trees to sprout from the ground, and trees necessary for food, and also the tree of life and the tree of knowledge of good and evil. (Some modern translations alter the tense-sequence so that the garden is prepared before the man is set in it, but the Hebrew has the man created before the garden).

- An unnamed river is described: it goes out from Eden to water the garden, after which it parts into four named streams.

- Yahweh sets the man in the garden to work it and keep it, and tells him he may eat the fruit of all the trees except the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, "for in that day thou shalt surely die."

- Yahweh sees it is not good for the man to be alone, and resolves to make a "helper" for him. He makes domestic animals and birds, and the man gives them their names, but none of them is a fitting helper. So Yahweh causes the man to sleep, and takes a rib and forms a woman. The woman proves to be the fit mate for the man, and a statement instituting marriage follows: "Therefore shall a man leave his father and his mother, and shall cleave unto his wife: and they shall be one flesh."

- Genesis 2 concludes with a notice that the man and his wife were naked, but felt no shame.

Composition

Historical context

Although tradition attributes the first five biblical books to Moses, today most scholars believe that they are "a composite work, the product of many hands and periods."[19] Genesis 2 (and indeed much of the remainder of Genesis, as well as much of Exodus and Numbers) is the product of an author, or perhaps a group of like-minded authors, called the Yahwist. The Yahwist wrote among and for the Jews of the Babylonian exile, which lasted from 658 to 538 BC, and his purpose was to demonstrate that Yahweh, the god of Israel, would act to save his chosen people no matter how often they sinned and turned away from him.[20]

Genesis 1, plus many other passages in Genesis, Exodus and Numbers and all of Leviticus, is the work of a different and later author or group of authors, called the Priestly source. These authors worked in Jerusalem and/or Babylon, in the period immediately after the Exile ended, and their purpose was to provide a blueprint for a society controlled by priests and the reconstructed Temple.[20] "Social order must mimic cosmic order, Israel and its priests carefully acting like Yahweh at creation and separating between what the worldview and the moral code allow and what they do not."[21]

As for why the book was created, a theory which has gained considerable interest, although still controversial is "Persian imperial authorisation". This proposes that the Persians, after their conquest of Babylon in 538 BC, agreed to grant Jerusalem a large measure of local autonomy within the empire, but required the local authorities to produce a single law code accepted by the entire community. The two powerful groups making up the community – the priestly families who controlled the Temple, and the landowning families who made up the "elders" – were in conflict over many issues, and each had its own "history of origins", but the Persian promise of greatly increased local autonomy for all provided a powerful incentive to cooperate in producing a single text.[22]

Influences on the Genesis creation narrative

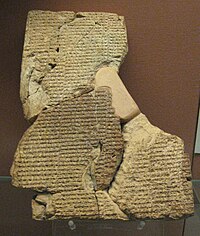

Genesis 1-11 as a whole is imbued with Mesopotamian myths.[23] Genesis 1 bears both striking differences from and striking similarities to Babylon's national creation myth, the Enuma Elish. On the side of similarities, both begin from a stage of chaotic waters before anything is created, in both a fixed dome-shaped "firmament" divides these waters from the habitable Earth, and both conclude with the creation of a human called "man" and the building of a temple for the god (in Genesis 1, this temple is the entire cosmos).[24] On the side of contrasts, Genesis 1 is uncompromisingly monotheistic, it makes no attempt to account for the origins of God, and there is no trace of the resistance to the reduction of chaos to order (Gk. theomachy, lit. "God-fighting"), all of which mark the Mesopotamian creation accounts.[1]

There also seems to be a direct literary relationship between Genesis 2 and the Enuma Elish. Both begin with a series of statements of what did not exist at the moment when creation began; the Enuma Elish has a spring (in the sea) as the point where creation begins, paralleling the spring (on the land – Genesis 2 is notable for being a "dry" creation story) in Genesis 2:6 that "watered the whole face of the ground"; in both myths, Yahweh/the gods first create a man to serve him/them, then animals and vegetation. At the same time, and as with Genesis 1, the Jewish version has drastically changed its Babylonian model: Eve, for example, seems to fill the role of a mother-goddess when, in Genesis 4:1, she says that she has "created a man with Yahweh", but she is in no way a divine being like her Babylonian counterpart.[25]

Scholars recognise close parallels between the Yahwist's creation story and another Mesopotamian myth, the Atra-Hasis epic – parallels that in fact extend throughout Genesis 2–11, from the Creation to the Flood and its aftermath. In addition to numerous plot-details (e.g. the divine garden and the role of the first man in the garden, the creation of the man from a mixture of earth and divine substance, the chance of immortality, etc), both stories have a similar overall theme: the gradual clarification of man's relationship with God(s) and animals.[15]

Biblical creation mythology outside Genesis

The narrative in Genesis 1 was not the only creation-myth in ancient Israel, and the complete biblical evidence seems to indicate two contrasting models. The first is the "logos" (meaning speech) model, where a supreme God "speaks" dormant matter into existence. The second is the "agon" (meaning struggle or combat) model, in which it is God's victory in battle over the monsters of the sea that mark his sovereignty and might.[26] Genesis 1 is the supreme example of the "logos" mythology; an example of the "agon" myth can be seen in Isaiah 51:9–10, in which the prophet recalls both the Exodus and the ancient Israelite myth in which God vanquishes the water deities: "Awake, awake! ... It was you that hacked Rahab in pieces, that pierced the Dragon! It was you that dried up the Sea, the waters of the great Deep, that made the abysses of the Sea a road that the redeemed might walk..."[27]

The agon creation tradition also preserves the original polytheistic religion of Israel, in which Yahweh was the head of the bene elohim, the "sons of God," or divine council. The lesser deities, the "host of heaven," have military and messenger functions, have great powers and knowledge, and are immortal. "What remains of this pantheon today are the angels who inhabit the sacred universes of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, [and] do the bidding of God."[28] Despite the thorough-going monotheism of Genesis 1-11, and especially Genesis 1, there remain traces of this underlying, older, polytheistic inheritance: thus, when God says "Let us make man in our own image," the most probable reading is that he is speaking to the members of the bene elohim council, and it can be inferred from Genesis 3 ("See," says God, "the man has become like one of us, knowing good from evil...") that the tree of life and the tree of knowledge of good and evil, which give benefits with which the bene elohim gods were associated (knowledge, immortality), were placed in Eden for the benefit of the gods.[29]

Exegetical points

General notes

Genesis 1 opens with the line Bereshit bara elohim, "In the beginning God created..." The word bara is translated as "created" in English, but the concept it embodied was not the same as the modern term. In the world of the ancient Near East, the gods demonstrated their power over the world not by creating matter but by fixing destinies: so the essence of the bara which God performs in Genesis concerns bringing "heaven and earth" (a set phrase meaning "everything") into existence by organising and assigning roles and functions.[5]

Two names of God are used, Elohim in Genesis 1 and Yahweh Elohim in Genesis 2. In a Jewish tradition dating back to the medieval scholar Rashi, the different names indicate different attributes of God, "Elohim" his justice, "Yahweh" his mercy, with Yahweh-Elohim combining the two.[30] In modern times the two names, plus differences in the styles of the two chapters and a number of discrepancies between Genesis 1 and Genesis 2, were instrumental in the development of source criticism and the documentary hypothesis.[31]

The cosmos created in Genesis 1-2:3 also bears a striking resemblance to the Tabernacle in Exodus 35-40, which was the prototype of the Temple in Jerusalem and the focus of priestly worship of Yahweh; for this reason, and because other Middle Eastern creation stories also climax with the construction of a temple/house for the creator-god, Genesis 1 can be interpreted as a description of the construction of the cosmos as God's house, and the Temple in Jerusalem as a microcosm of the cosmos.[32]

The use of numbers in ancient texts was often numerological rather than factual - that is, the numbers were used because they held some symbolic value to the author.[33] The number seven, denoting divine completion, permeates Genesis 1: verse 1:1 consists of seven words, verse 1:2 of fourteen, and 2:1-3 has 35 words (5x7); Elohim is mentioned 35 times, "heaven/firmament" and "earth" 21 times each, and the phrases "and it was so" and "God saw that it was good" occur 7 times each.[34] The number four symbolises completion on earth: the four rivers of Eden water "all the earth".[35]

Genesis 2-3, the story of Eden, was probably authored around 500 BC as "a discourse on ideals in life, the danger in human glory, and the fundamentally ambiguous nature of humanity - especially human mental facilities." According to Genesis 2:10-14 the Garden is located on the mythological border between the human and the divine worlds, probably on the far side of the Cosmic Ocean near the rim of the world; following a conventional ancient Near Eastern concept, the Eden river first forms that ocean and then divides into four rivers which run from the four corners of the earth towards its centre.[36]

Genesis 1:1-3

- In the beginning

- In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth and the earth was without form, and void, and darkness was over the Deep and the "rûach" of God hovered over the face of the waters.

The opening phrase of Genesis 1:1 can be translated in at least three ways: (1) as a statement that the cosmos had an absolute beginning (In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth); (2) as a statement describing the condition of the world when God began creating (When in the beginning God created the heavens and the earth, the earth was untamed and shapeless); and (3) essentially similar to the second version but taking all of Genesis 1:2 as background information (When in the beginning God created the heavens and the earth, the earth being untamed and shapeless, God said, Let there be light!).[38] The second seems to be the meaning intended by the original Priestly author: the verb bara is used only of God, (people do not bara), and it concerns the assignment of roles, as in the creation of the first people as "male and female" (i.e., it allocates them gender roles): in other words, the power of God is being shown not by the creation of matter but by the fixing of destinies.[5]

"The heavens and the earth" is a set phrase meaning "everything", i.e., the cosmos. This was made up of three levels, the habitable earth in the middle, the heavens above, an underworld below, all surrounded by a watery "ocean" of chaos. The earth itself was a flat disc, surrounded by mountains or sea. Above it was the firmament, a transparent but solid dome resting on the mountains, allowing men to see the blue of the waters above, with "windows" to allow the rain to enter, and containing the sun, moon and stars. The waters extended below the earth, which rested on pillars sunk in the waters, and in the underworld was Sheol, the abode of the dead.[39]

Before God begins the world is tohu wa-bohu (Hebrew: תֹהוּ וָבֹהוּ): the word tohu by itself means "emptiness, futility"; it is used to describe the desert wilderness. Bohu has no known meaning and was apparently coined to rhyme with and reinforce tohu.[40] It appears again in Jeremiah 4:23,Jer. 4:23 where Jeremiah warns Israel that rebellion against God will lead to the return of darkness and chaos, "as if the earth had been ‘uncreated’."[41] Tohu wa-bohu, chaos, is the condition that bara, ordering, remedies.[42]

Darkness and "Deep" (Heb. תְהוֹם tehôm)are two of the three elements of the chaos represented in tohu wa-bohu (the third is the formless earth). In the Enuma Elish the Deep is personified as the goddess Tiamat, the enemy of Marduk;[42] here it is the formless body of primeval water surrounding the habitable world, later to be released during the Deluge, when "all the fountains of the great deep burst forth" from the waters beneath the earth and from the "windows" of the sky.[43]

Rûach (רוּחַ) has the meanings "wind, spirit, breath," and elohim can mean "great" as well as "god": the ruach elohim which moves over the Deep may therefore mean the "wind/breath of God" (the storm-wind is God's breath in Psalms 18:16 and elsewhere, and the wind of God returns in the Flood story as the means by which God restores the earth), or God's "spirit", a concept which is somewhat vague in Hebrew bible, or simply a great storm-wind.[44] Victor Hamilton in his commentary on Genesis decides, somewhat tentatively, for "spirit of God", but dismisses any suggestion that this can be identified with the Holy Spirit of Christian theology.[45]

Genesis 1:4-13

- Day 1

- And God said, Let there be light! and there was light, and God saw that the light was good, and he separated the light from the darkness. God called the light “day,” and the darkness he called “night.” And there was evening, and there was morning—the first day.

God creates by spoken command and names the elements of the world as he creates them. In the ancient Near East the act of naming was bound up with the act of creating: thus in Egyptian literature the creator god pronounced the names of everything, and the Enuma Elish begins at the point where nothing has yet been named.[4] God's creation by speech also suggests that he is being compared to a king, who has merely to speak for things to happen.[3]

- Day 2

- And God said, “Let there be a rāqîa between the waters to separate water from water.” So God made the rāqîa and separated the water under the vault from the water above it, and it was so, and God called the rāqîa “heavens”, and there was evening, and there was morning—the second day.

Rāqîa, or firmament, is from rāqa, the verb used for the act of beating metal into thin plates.[46] Created on the second day of creation and populated by luminaries on the fourth, it is a solid dome which separates the earth below from the heavens and their waters above, as in Egyptian and Mesopotamian belief of the same time.[47] In Genesis 1:17 the stars are set in the raqia; in Babylonian myth the heavens were made of various precious stones (compare Exodus 24:10,Exodus 24:10 where the elders of Israel see God on the sapphire floor of heaven), with the stars engraved in their surface.[48]

- Day 3

- And God said, “Let the water under the sky be gathered to one place, and let dry ground appear.” And it was so. God called the dry ground “land,” and the gathered waters he called “seas.” And God saw that it was good.

The waters withdraw, creating a ring of ocean surrounding a single circular continent.[49] After this, the last of three acts of separation - darkness from light, water from water, seas from land - the third day continues with preparations for populating the now orderly world.

- Then God said, “Let the land produce vegetation: seed-bearing plants and trees on the land that bear fruit with seed in it, according to their various kinds.” And it was so. The land produced vegetation: plants bearing seed according to their kinds and trees bearing fruit with seed in it according to their kinds. And God saw that it was good, and there was evening, and there was morning—the third day.

God does not create or make trees and plants, but instead commands the earth to produce them. The underlying theological meaning seems to be that God has given the previously barren earth the ability to produce vegetation, and it now does so at his command. Paul Kissling of Dallas Christian College, in his commentary on Genesis, makes the point that the reference to "kinds" appears to look forward to the laws found later in the Pentateuch, which lay great stress on holiness through separation.[50] At the end of the third day God has created a foundational environment of light, heavens, seas and earth.[51]

Genesis 1:14-2:3

- Day 4

- And God said, “Let there be lights in the firmament of the heavens to separate the day from the night, and let them serve as signs to mark seasons and days and years, and let them be lights in the vault of the sky to give light on the earth,” and it was so. God made two great lights, the greater light to govern the day and the lesser light to govern the night. He also made the stars. God set them in the vault of the sky to give light on the earth, to govern the day and the night, and to separate light from darkness. And God saw that it was good. And there was evening, and there was morning—the fourth day.

The three levels of the cosmos are populated in the same order in which they were created - heavens, sea, earth. The language of "ruling" is introduced: the heavenly bodies will "govern" day and night and mark seasons and years and days: this was of central importance to the Priestly authors and the religious festivals organised around the cycles of the sun and moon.[52] Our translation here says God puts "lights" in the firmament, but the Hebrew word ma'or means literally "lamps".[53]

- Day 5

- And God said, “Let the water teem with living creatures, and let birds fly above the earth across the vault of the sky.” So God created the great creatures of the sea and every living and moving thing with which the water teems, according to their kinds, and every winged bird according to its kind, and God saw that it was good. God blessed them and said, “Be fruitful and increase in number and fill the water in the seas, and let the birds increase on the earth.” And there was evening, and there was morning—the fifth day.

In the Egyptian and Mesopotamian mythologies the creator-god has to do battle with the sea-monsters before he can make heaven and earth; in Genesis 1:21 the word tanin, sometimes translated as "sea monsters" ("great creatures" in the translation here), parallels the named chaos-monsters Rahab and Leviathan from Psalm 74:13 and Isaiah 27:1 and 51:9, but there is no hint of combat and the tanin are simply creatures created by God.[54]

- Day 6

- And God said, “Let the land produce living creatures according to their kinds: livestock, creatures that move along the ground, and wild animals, each according to its kind.” And it was so. God made the wild animals according to their kinds, the livestock according to their kinds, and all the creatures that move along the ground according to their kinds. And God saw that it was good.

The world has now been inhabited and is ready for the creation of mankind.

- Then God said, “Let us make human beings in our image, in our likeness, so that they may rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky, over the livestock and all the wild animals, and over all the creatures that move along the ground.” So God created human beings in his own image, in the image of God he created them, male and female he created them.

When in Genesis 1:26 God says "Let us make man", the word used is adam; in this form it is a generic noun, "mankind", and does not imply that this creation is male. After this first mention the word always appears as ha-adam, "the man", but as Genesis 1:27 shows ("God created the human in his own image ... male and female he created them"), the word is still not exclusively male. In Genesis 2:7 a pun is introduced: God creates adam (man) from adamah (earth).[55]

The meaning of the phrase "image of God" is unclear. Suggestions include: (1) Having the spiritual qualities of God such as intellect, will, etc.; (2) Having the physical form of God; (3) a combination of these two; (4) Being God's counterpart on earth and able to enter into a relationship with him; (5) Being God's representative or viceroy on earth.[56]

The fact that God says "Let us make man..." has given rise to several theories, of which the two most important are that "us" is royal plural or plural of majesty,[57] or that it reflects a setting in a divine council with God enthroned as king and proposing the creation of mankind to the lesser divine beings.[58]

- God blessed them and said to them, “Be fruitful and increase; fill the earth and subdue it; rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground.” Then God said, “I give you every seed-bearing plant on the face of the whole earth and every tree that has fruit with seed in it. They will be yours for food. 30 And to all the beasts of the earth and all the birds in the sky and all the creatures that move on the ground—everything that has the breath of life in it—I give every green plant for food.” And it was so.

God tells the animals and humans that he has given them "the green plants for food" - creation is to be vegetarian. Only later, after the Flood, is man given permission to eat meat. This has led to some interesting modern proposals on the theological program of the Priestly author of Genesis: this author appears to look back to an ideal past in which mankind lived at peace both with itself and with the animal kingdom, and which could be re-achieved through a proper sacrificial life in harmony with God.[59]

- God saw all that he had made, and it was very good. And there was evening, and there was morning—the sixth day.

God's first act was the creation of undifferentiated light; dark and light were then separated into night and day, their order (evening before morning) signifying that this was the liturgical day; and then the sun, moon and stars were created to mark the proper times for the festivals of the week and year. Only when this is done does God create man and woman and the means to sustain them (plants and animals). At the end of the sixth day, when creation is complete, the world is a cosmic temple in which the role of humanity is the worship of God. This parallels Mesopotamian myth (the Enuma Elish) and also echoes chapter 38 of the Book of Job, where God recalls how the stars, the "sons of God", sang when the corner-stone of creation was laid.[60]

- Day 7

- Thus the heavens and the earth were finished, and all the host of them. And on the seventh day God finished his work that he had done, and he rested on the seventh day from all his work that he had done. So God blessed the seventh day and made it holy, because on it God rested from all his work that he had done in creation. (Genesis 2:1–2:3)

Creation is followed by rest. This is not quite the Sabbath, which is commanded in Exodus, but it looks forward to it. In ancient Near Eastern literature the divine rest is achieved in a temple as a result of having brought order to chaos. Rest is both disengagement, as the work of creation is finished, but also engagement, as the deity is now present in his temple to maintain a secure and ordered cosmos.[61]

Genesis 2:4-25

- In the day that the LORD God made the earth and the heavens, when no bush of the field was yet in the land and no small plant of the field had yet sprung up, for the LORD God had not caused it to rain on the land, and there was no man to work the ground, and a mist was going up from the land and was watering the whole face of the ground...

The Yahwistic creation account opens "in the day the LORD God made the earth and the heavens," a set introduction similar to those found in similar Babylonian myths.[62] Before the man is created the earth is a barren waste watered by an ed (Genesis 2:6); the KJV translated this as "mist", following Jewish practice, but since the the mid-20th century it has been generally accepted that the real meaning is a spring of underground water.[63]

- ...then the LORD God formed the man of dust from the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living creature.

In Genesis 1 the characteristic word for God's activity is bara, "created"; in Genesis 2 the word used when he creates the man is yatsar, meaning "fashioned", a word used in contexts such as a a potter fashioning a pot from clay.[9] God breathes his own breath into the clay and it becomes nepesh, a word meaning life, vitality, the living personality; man shares nepesh with all creatures, but only of man is this life-giving act of God described.[10]

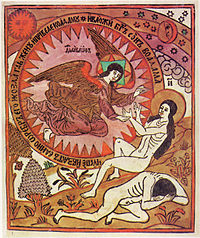

- And the LORD God planted a garden in Eden, in the east, and there he put the man whom he had formed. And out of the ground the LORD God made to spring up every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food. The tree of life was in the midst of the garden, and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

Eden, where God puts his Garden of Eden, is from a root meaning fertility: the first man is to work in God's miraculously fertile garden.[64] The "tree of life" is a motif from Mesopotamian myth: in the Epic of Gilgamesh the hero is given a plant whose name is "man becomes young in old age," but the plant is stolen from him by a serpent.[65] There has been much scholarly discussion about the type of knowledge given by the second tree, whether human qualities, sexual consciousness, ethical knowledge, or universal knowledge, with the last being the most widely accepted.[66] In Eden, mankind has a choice between wisdom and life, and chooses the first, although God intended them for the second.[67]

- Now a river flowed out of Eden to water the garden, and from there it divided and became four rivers. The name of the first is Pishon; it flows around the whole land of Havilah, where there is gold. The gold of that land is good; the bdellium and the onyx stone are there. The name of the second river is Gihon; it flows around the whole land of Cush. The name of the third river is Tigris; it flows east of Assyria. And the fourth river is the Euphrates.

The mythic Eden and its rivers may reflect the real Jerusalem, the Temple and the Promised Land. Eden may represent the divine garden on Zion, the mountain of God, which was also Jerusalem; while the real Gihon was a spring outside the city (mirroring the spring which waters Eden); and the imagery of the Garden, with its serpent and cherubs, has been seen as a reflection of the real images of the Solomonic Temple with its copper serpent (the nehushtan) and guardian cherubs.[68] Genesis 2 is the only place in the bible where it appears as a geographic location: elsewhere, notably Book of Ezekiel 28, it is a mythological place located on the holy Mountain of God, with echoes of a Mesopotamian myth of the king as a primordial man placed in a divine garden to guard the tree of life.[69]

- Then the LORD God took the man and put him into the garden of Eden to cultivate it and keep it. The LORD God commanded the man, saying, “From any tree of the garden you may eat freely; but from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat from it you will surely die.”

"Good and evil" may be a set phrase meaning simply "everything", but it may also have a moral connotation. When God forbids the man to eat from the tree of knowledge he says that if he does so he is "doomed to die": the Hebrew behind this is in the form used in the bible for issuing death sentences.[70]

- Then the LORD God said, “It is not good for the man to be alone; I will make him a helper suitable for him.” Out of the ground the LORD God formed every beast of the field and every bird of the sky, and brought them to the man to see what he would call them; and whatever the man called a living creature, that was its name; the man gave names to all the cattle, and to the birds of the sky, and to every beast of the field...

The term "helper" is a customary English term used for the Hebrew phrase ezer kenegdo, which is notably difficult to translate. Kenegdo means "alongside, opposite, a counterpart to him", and ezer means active intervention on behalf of the other person.[71] God's naming of the elements of the cosmos in Genesis 1 illustrated his authority over creation; now the man's naming of the animals (and of Woman) illustrates his authority within creation.[72]

- ...but for Adam there was not found a helper suitable for him. So the LORD God caused a deep sleep to fall upon the man, and he slept; then He took one of his ribs and closed up the flesh at that place. The LORD God fashioned into a woman the rib which He had taken from the man, and brought her to the man. The man said, “This is now bone of my bones, And flesh of my flesh; She shall be called Woman, because she was taken out of Man.”

The woman is called ishshah, Woman, with an explanation that this is because she was taken from ish, meaning "man"; the two words are not in fact connected. Later, after the story of the Garden is complete, she will be given a name, Hawwah, Eve. This means "living" in Hebrew, from a root that can also mean "snake".[73] The use of a rib from man's side, instead of a head bone or a foot bone, implies the woman to be his equal--loved and protected--rather his ruler or his slave being trampled under foot.[74]

- For this reason a man shall leave his father and his mother, and be joined to his wife; and they shall become one flesh. And the man and his wife were both naked and were not ashamed.

Marriage is monogamous ("wife", not "wives" - in Judah at the time Genesis was canonised the issue of marriage, polygamy and divorce was a burning one) and takes precedence over all other ties. The end-point of creation is a man and a woman united in a state of innocence, but the word "naked", arummim, looks forward to the "subtle", arum, serpent about to be introduced in the next verse.[75]

See also

- Adapa

- Atra-hasis epic

- Allegorical interpretations of Genesis

- Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament

- Babylonian mythology

- Bereishit (parsha) (Traditional Jewish understandings of Genesis 1-2)

- Biblical cosmology

- Biblical criticism

- Christian mythology

- Creation (disambiguation)

- Enuma Elish

- Hexameron

- Jehovah

- Jewish mythology

- List of creation myths

- Mesopotamian mythology

- Religion and mythology

- Sumerian creation myth

- Sumerian literature

- Timeline of the Bible

- Tree of the knowledge of good and evil

- Tree of life

- Yahweh

Citations

- ^ a b Sarna 1997, p. 50.

- ^ Alter 2004, p. xii.

- ^ a b Bandstra 1999, p. 39.

- ^ a b Walton 2003, p. 158.

- ^ a b c Walton 2006, p. 183.

- ^ Brueggemann 1982, p. 29. "The familiar statement of verse 1 admits more of more than one rendering. The conventional translation (supported by Isa 46:10) makes a claim for creation as an absolute and decisive act of God. But it may be a dependent temporal clause ("when God began to create"): it then relates closely to what follows, and creation is understood to be an ongoing work which God has begun and continues. The evidence of the grammar is not decisive, and either rendering is possible."

- ^ Brueggemann 1982, pp. 29–30. "The very ambiguity of creation from nothing and creation from chaos is a rich expository possibility. We need not choose between them, even as the text does not...The former asserts the majestic and exclusive power of God. The latter asserts that even the way life is can be claimed by God. By the double focus on the power of God and the use made of chaos, the text affirms the difference between God and creature."

- ^ Wenham 1987, p. 352.

- ^ a b Alter 2004, p. 20, 22.

- ^ a b Davidson 1973, p. 31.

- ^ Davies 2001, p. 37.

- ^ Leeming 2004.

- ^ Whybray 2001, p. 40.

- ^ Ruiten 2000, pp. 9–10.

- ^ a b c Carr 1996, p. 64.

- ^ Friedman 2003, p. 35 (fn).

- ^ Cross 1973, pp. 301ff.

- ^ Thomas 2011, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Speiser 1964, p. xxi.

- ^ a b KuglerHartin 2009, pp. 14–16.

- ^ Janzen 2004, p. 118.

- ^ Ska 2006, pp. 169, 217–218.

- ^ Kutsko 2000, p. 62, quoting J. Maxwell Miller.

- ^ McDermott 2002, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Van Seters 1992, pp. 122–124.

- ^ Fishbane 2003, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Brettler 2005, pp. 203–204.

- ^ Penchansky 2005, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Penchansky 2005, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Kaplan 2002, p. 93.

- ^ Wylen 2005, p. 109.

- ^ Levenson 2004, p. 13.

- ^ Hyers 1984, p. 74.

- ^ Wenham 1987, p. 6.

- ^ Stordalen 2000, p. 275-276.

- ^ Stordalen 2000, p. 473-474.

- ^ Keel 1997, p. 20.

- ^ Bandstra 1999, p. 38-39.

- ^ Knight 1990, pp. 175–176.

- ^ Alter 2004, p. 17.

- ^ Thompson 1980, p. 230.

- ^ a b Walton 2001.

- ^ Wenham 2003, p. 29.

- ^ Blenkinsopp 2011, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Hamilton 1990, pp. 111–114.

- ^ Hamilton 1990, p. 122.

- ^ Seeley 1991, p. 227.

- ^ Walton 2003, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Seeley 1997, p. 236.

- ^ Kissling 2004, p. 106.

- ^ Bandstra 1999, p. 41.

- ^ Bandstra 1999.

- ^ Walsh 2001, p. 37 (fn.5).

- ^ Walton 2003, p. 160.

- ^ Alter 2004, p. 18-19,21.

- ^ Kvam et. al. 1999, p. 24.

- ^ Davidson 1973, p. 24.

- ^ Levenson 2004, p. 14.

- ^ Rogerson 1991, p. 19ff.

- ^ Blenkinsopp 2011, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Walton 2006, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Van Seters 1998, p. 22.

- ^ Anderson 1987, pp. 137–140.

- ^ Levenson 2004, p. 15.

- ^ Davidson 1973, p. 29.

- ^ Kooij 2010, p. 17.

- ^ Propp 1990, p. 193.

- ^ Stordalen 2000, p. 307-310.

- ^ Davidson 1973, p. 33.

- ^ Alter 2004, p. 21.

- ^ Alter 2004, p. 22.

- ^ Turner 2009, p. 20.

- ^ Hastings 2003, p. 607.

- ^ White 1958, p. 46.

- ^ Kissling 2004, pp. 176–178.

References

- Alter, Robert (2004). The Five Books of Moses. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393333930.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Anderson, Francis I. (1987). "On Reading Genesis 1-3". In Freedman (ed.). Backgrounds for the Bible. Eisenbrauns.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Missing|editor1=(help); Unknown parameter|editor1 first=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|editor1 last=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|editor2 first=ignored (help) - Bandstra, Barry L. (1999). Reading the Old Testament: An Introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Wadsworth Publishing Company. p. 576. ISBN 0495391050.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2011). Creation, Un-Creation, Re-Creation: A Discursive Commentary on Genesis 1-11. T&T Clarke International.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bouteneff, Peter C. (2008). Beginnings: Ancient Christian Readings of the Biblical Creation Narrative. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic. ISBN 9780801032332.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title=|ref=harv(help) - Brettler, Mark Zvi (2005). How To Read the Bible. Jewish Publication Society.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brueggemann, Walter (1982). "Genesis 1:1-2.4". Interpretation of Genesis. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 382. ISBN 9780804231015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Carr, David M. (1996). Reading the Fractures in Genesis. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0664220711.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Biography: David M. Carr, Professor of Old Testament - Union Theological Seminary - Carr, David M. (2011). "The Garden of Eden Story". An Introduction to the Old Testament. John Wiley & Sons.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cross, Frank Moore (1973). "The Priestly Work". Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic: Essays in the History of the Religion of Israel. Harvard University Press. p. 394. ISBN 0674091760.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapter=|ref=harv(help) - Dalley, Stephanie (2000). Myths from Mesopotamia: creation, the flood, Gilgamesh, and others. Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davidson, Robert (1973). Genesis 1-11. Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, G.I. (2001). "Introduction to the Pentateuch". In John Barton (ed.). Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fishbane, Michael (2003). Biblical Myth and Rabbinic Mythmaking. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198267339.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title=|ref=harv(help) - Friedman, Richard Elliott (2003). The Bible with Sources Revealed. HarperCollins.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hamilton, Victor P (1990). The Book of Genesis: Chapters 1-17. New International Commentary on the Old Testament (NICOT). Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 540. ISBN 0802825214.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hastings, James (2003). Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics, Part 10. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 9780766136823.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Heidel, Alexander (1963). Babylonian Genesis (2nd ed.). Chicago University Press. ISBN 0226323994.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title=|ref=harv(help) - Heidel, Alexander (1963). The Gilgamesh Epic and Old Testament Parallels (2nd Revised ed.). Chicago University Press. ISBN 0226323986.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title=|ref=harv(help) - Hyers, Conrad (1984). The meaning of creation: Genesis and modern science. Westminster John Knox. p. 207. ISBN 0804201250.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Janzen, David (2004). The social meanings of sacrifice in the Hebrew Bible: a study of four writings. Walter de Gruyter Publisher. ISBN 978-3110181586.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kaplan, Aryeh (2002). "Hashem/Elokim: Mixing Mercy with Justice". The Aryeh Kaplan reader: the gift he left behind. Mesorah Publication, Ltd. p. 224. ISBN 0899061737. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Keel, Othmar (1997). The symbolism of the biblical world. Eisenbrauns.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - King, Leonard (2010). Enuma Elish: The Seven Tablets of Creation; The Babylonian and Assyrian Legends Concerning the Creation of the World and of Mankind. Cosimo Inc.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kissling, Paul (2004). Genesis, Volume 1. College Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Knight, Douglas A (1990). "Cosmology". In Watson E. Mills (General Editor) (ed.). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press. ISBN 0865544026.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kooij, Arie van der (2010). "The story of Paradise in the light of Mesopotamian culture and literature". In Dell, Katherine J; Davies, Graham; Koh, Yee Von (eds.). Genesis, Isaiah, and Psalms. Brill.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kugler, Robert; Hartin, Patrick (2009). An Introduction to the Bible. Eerdmans.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kutsko, John F. (2000). Between Heaven and Earth: divine presence and absence in the Book of Ezekiel. Eisenbrauns.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kvam, Kristen E.; Schearing, Linda S.; Ziegler, Valarie H., eds. (1999). Eve and Adam: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim readings on Genesis and gender. Indiana University Press. p. 515. ISBN 0253212715.

- Leeming, David A. (2004). "Biblical creation". The Oxford companion to world mythology (online ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Levenson, Jon D. (2004). "Genesis: introduction and annotations". In Berlin, Adele; Brettler, Marc Zvi (eds.). The Jewish study Bible. Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Louth, Andrew (2001). "Introduction". In Andrew Louth (ed.). Genesis 1-11. InterVarsity Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - May, Gerhard (1994 (English trans. 2004)). Creatio ex nihilo. T&T Clarke International.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McDermott, John J. (2002). Reading the Pentateuch: a historical introduction. Paulist Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McMullin, Ernin (2010). "Creation ex nihilo: early history". In David B. Burrell, Carlo Cogliati, Janet M. Soskice (ed.). Creation and the God of Abraham. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Penchansky, David (2005). Twilight of the Gods: Polytheism in the Hebrew Bible. U.S.: Westminster/John Knox Press. ISBN 0664228852.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Propp, W.H. (1990). "Eden Sketches". In Propp, W.H.; Halpern, Baruch; Freedman, D.N. (eds.). The Hebrew Bible and its interpreters. Eisenbrauns.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ruiten, Jacques T. A. G. M. (2000). Primaeval history interpreted. Brill.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rogerson, John William (1991). Genesis 1-11. T&T Clark.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sarna, Nahum M. (1997). "The Mists of Time: Genesis I-II". In Feyerick, Ada (ed.). Genesis: World of Myths and Patriarchs. New York: NYU Press. p. 560. ISBN 0814726682.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sawyer, John F.A. (1992). "The Image of God, the Wisdom of Serpents, and the Knowledge of Good and Evil". In Paul Morris, Deborah Sawyer (ed.). A walk in the garden: biblical, iconographical and literary images of Eden. Sheffield Academic Press Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Seeley, Paul H. (1991). "The Firmament and the Water Above: The Meaning of Raqia in Genesis 1:6–8" (PDF). Westminster Theological Journal. 53. Westminster Theological Seminary: 227–240.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Seeley, Paul H. (1997). "The Geographical Meaning of 'Earth' and 'Seas' in Genesis 1:10" (PDF). Westminster Theological Journal. 59. Westminster Theological Seminary: 231–55.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ska, Jean-Louis (2006). Introduction to reading the Pentateuch. Eisenbrauns.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Smith, Mark S. (2002). The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel (2nd ed.). William B Eerdmans Publishing Co. ISBN 080283972X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Smith, Mark S. (2001). The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts (New Ed ed.). Oxford University Press USA. ISBN 0195167686.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Speiser, Ephraim Avigdor (1964). Genesis. Doubleday.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Spence, Lewis (1916 (reissued 2010)). Myths and Legends of Babylonia and Assyria. Kessinger Publishing, LLC. p. 496. ISBN 1564595005.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stenhouse, John (2000). "Genesis and Science". In Gary B. Ferngren (ed.). The History of Science and Religion in the Western Tradition: An Encyclopedia. New York, London: Garland Publishing, Inc. p. 76. ISBN 0-8153-1656-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stordalen, Terje (2000). Echoes of Eden. Peeters.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thomas, Matthew A. (2011). These Are the Generations: Identity, Covenant and the Toledot Formula. T&T Clark (Continuum).

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thompson, J. A. (1980). Jeremiah. New International Commentary on the Old Testament (2nd ed.). Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 831. ISBN 0802825303.

it's as if the earth had been 'uncreated.'

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Turner, Laurence A. (2009). Genesis. Sheffield Phoenix Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Van Seters, John (1998). "The Pentateuch". In Steven L., McKenzie; M. Patrick, Graham (eds.). The Hebrew Bible Today: An Introduction to Critical Issues. Westminster John Knox Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Van Seters, John (1992). Prologue to History: The Yahwist As Historian in Genesis. New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0664221793.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Walsh, Jerome T. (2001). Style and structure in Biblical Hebrew narrative. Liturgical Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Walton, John H. (2006). Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament: Introducing the Conceptual World of the Hebrew Bible. Baker Academic. ISBN 0801027500.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Walton, John H. (2003). "Creation". In T. Desmond Alexander, David Weston Baker (ed.). Dictionary of the Old Testament: Pentateuch. InterVarsity Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Walton, John H. (2001). Genesis. Zondervan. ISBN 9780310866206.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Walton, John H.; Matthews, Victor H.; Chavalas, Mark W. (2000). "Genesis". The IVP Bible background commentary: Old Testament. InterVarsity Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wenham, Gordon (2003). Exploring the Old Testament: A Guide to the Pentateuch. Exploring the Bible Series. Vol. 1. IVP Academic. p. 223.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wenham, Gordon (1987). Genesis 1-15. Vol. 1 and 2. Texas: Word Books. ISBN 0849902002.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - White, Ellen G. (1958) [1910]. "The Creation". Patriarchs and Prophets. The Conflict of the Ages. Vol. 1. Boise, Idaho: Pacific Press Publishing Association. p. 803. ISBN 1883012503.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Whybray, R.N (2001). "Genesis". In John Barton (ed.). Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wylen, Stephen M. (2005). "Chapter 6 Midrash". The seventy faces of Torah: the Jewish way of reading the Sacred Scriptures. Paulist Press. p. 256. ISBN 0809141795.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)

External links

Sources for the biblical text

- Chapter 1 Chapter 2 (Hebrew-English text, translated according to the JPS 1917 Edition)

- Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 (Hebrew-English text, with Rashi's commentary. The translation is the authoritative Judaica Press version, edited by Rabbi A.J. Rosenberg.)

- Chapter 1 Chapter 2 (New American Bible)

- Chapter 1 Chapter 2 (King James Version)

- Chapter 1 Chapter 2 (Revised Standard Version)

- Chapter 1 Chapter 2 (New Living Translation)

- Chapter 1 Chapter 2 (New American Standard Bible)

- Chapter 1 Chapter 2 (New International Version (UK))

- "Enuma Elish", at Encyclopedia of the Orient Summary of Enuma Elish with links to full text.

- ETCSL—Text and translation of the Eridu Genesis (alternate site) (The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford)

- "Epic of Gilgamesh" (summary)

- British Museum: Cuneiform tablet from Sippar with the story of Atra-Hasis