Iridescent (talk | contribs) |

Iridescent (talk | contribs) →Background: reword for clarity |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

The historic industrial town of [[Chelsea, London|Chelsea]] on the north bank of the [[River Thames]] about {{convert|3|mi|km}} west of [[Westminster]], and the rich farming village of [[Battersea]] facing it on the south bank, had been linked by the modest wooden [[Battersea Bridge]] since 1771.<ref name="Matthews65">{{Harvnb|Matthews|2008|p=65}}</ref> In 1842 the [[Commissioners of Woods and Forests|Commission of Woods, Forests, and Land Revenues]] recommended the building of an [[Thames Embankment|embankment]] at Chelsea to free new land for development, and proposed the building of a new bridge downstream of Battersea Bridge and the replacement of Battersea Bridge with a more modern structure.<ref name="Roberts130">{{Harvnb|Roberts|2005|p=130}}</ref> Work on the [[Chelsea Embankment]] began in 1862, and work on the [[Chelsea Bridge|Victoria Bridge]] (later renamed Chelsea Bridge), a short distance downstream of Battersea Bridge, began in 1851 and was completed in 1858.<ref name="Roberts112">{{Harvnb|Roberts|2005|p=112}}</ref> The proposal to demolish Battersea Bridge was meanwhile abandoned.<ref name="Roberts130" /> |

The historic industrial town of [[Chelsea, London|Chelsea]] on the north bank of the [[River Thames]] about {{convert|3|mi|km}} west of [[Westminster]], and the rich farming village of [[Battersea]] facing it on the south bank, had been linked by the modest wooden [[Battersea Bridge]] since 1771.<ref name="Matthews65">{{Harvnb|Matthews|2008|p=65}}</ref> In 1842 the [[Commissioners of Woods and Forests|Commission of Woods, Forests, and Land Revenues]] recommended the building of an [[Thames Embankment|embankment]] at Chelsea to free new land for development, and proposed the building of a new bridge downstream of Battersea Bridge and the replacement of Battersea Bridge with a more modern structure.<ref name="Roberts130">{{Harvnb|Roberts|2005|p=130}}</ref> Work on the [[Chelsea Embankment]] began in 1862, and work on the [[Chelsea Bridge|Victoria Bridge]] (later renamed Chelsea Bridge), a short distance downstream of Battersea Bridge, began in 1851 and was completed in 1858.<ref name="Roberts112">{{Harvnb|Roberts|2005|p=112}}</ref> The proposal to demolish Battersea Bridge was meanwhile abandoned.<ref name="Roberts130" /> |

||

Although Chelsea and Battersea were now linked by two bridges, by the mid 19th century the wooden Battersea Bridge |

Although Chelsea and Battersea were now linked by two bridges, by the mid 19th century the wooden Battersea Bridge had become dilapidated and was considered unsafe and unpopular.<ref name="Roberts63">{{Harvnb|Roberts|2005|p=63}}</ref> The newer Victoria Bridge, meanwhile, suffered severe congestion. In 1860, [[Albert, Prince Consort|Prince Albert]] suggested that a new [[tollbridge]] built between the two existing bridges would be profitable,<ref name="Davenport71">{{Harvnb|Davenport|2006|p=71}}</ref> and in the early 1860s the Albert Bridge Company was created with the aim of building a new bridge.<ref name="Matthews71">{{Harvnb|Matthews|2008|p=71}}</ref> An 1863 proposal was blocked by strong opposition from the operators of Battersea Bridge, less than {{convert|500|yd|m}} from the site proposed for the new bridge and concerned at potential loss of custom.<ref name="Matthews71" /> A compromise was reached, and in 1864 a new Act of Parliament was passed, authorising the new bridge on condition that it was completed within five years,<ref name="Cookson126">{{Harvnb|Cookson|2006|p=126}}</ref> but compelling the Albert Bridge Company to purchase Battersea Bridge at the time of the new bridge's opening and to compensate the owners of Battersea Bridge with £3,000 (about £{{formatnum:{{Inflation|UK|3000|1864|r=-3}}|0}} as of {{CURRENTYEAR}}) per annum until the new bridge opened.<ref name="Davenport72" />{{Inflation-fn|UK}} |

||

[[File:Bridge of Franz Joseph I., Prague.jpg|right|thumb|The 1868 [[Franz Joseph Bridge]] in Prague was built to the proposed design of the future Albert Bridge]] |

[[File:Bridge of Franz Joseph I., Prague.jpg|right|thumb|The 1868 [[Franz Joseph Bridge]] in Prague was built to the proposed design of the future Albert Bridge]] |

||

Revision as of 00:45, 7 June 2009

Albert Bridge | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates | 51°28′56″N 0°10′00″W / 51.48222°N 0.16667°W |

| Carries | A3031 road |

| Crosses | River Thames |

| Locale | Chelsea, London |

| Heritage status | Grade II* listed structure |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Ordish–Lefeuvre Principle, subsequently modified to an Ordish–Lefeuvre Principle / Suspension bridge / Beam bridge hybrid design |

| Total length | 710 feet (220 m) |

| Width | 41 feet (12 m) |

| Height | 66 feet (20 m) |

| Longest span | 384 feet 9 inches (117.27 m) (before 1973), 185 feet (56 m) (after 1973) |

| No. of spans | 4 (3 before 1973) |

| Piers in water | 6 (4 before 1973) |

| Clearance below | 37 feet 9 inches (11.5 m) at lowest astronomical tide[1] |

| History | |

| Designer | Rowland Mason Ordish, Joseph Bazalgette |

| Opened | 23 August 1873 |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 19,821 vehicles (2004)[2] |

| Location | |

| |

Albert Bridge is a Grade II* listed road bridge over the River Thames in West London, connecting Chelsea on the north bank to Battersea on the south bank. Designed and built by Rowland Mason Ordish as an Ordish–Lefeuvre Principle modified cable-stayed bridge in 1873, the bridge proved structurally unsound and between 1884 and 1887 was modified by Sir Joseph Bazalgette into a structure incorporating design elements of a suspension bridge. Continued problems with the bridge's structural soundness led to the Greater London Council adding two concrete piers in 1973, turning the central span of the bridge into a simple beam bridge. Consequently, the bridge is today an unusual hybrid of three different bridge types.

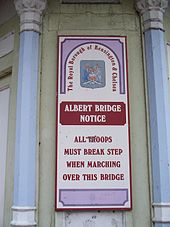

The bridge was built as a toll bridge, but was commercially unsuccessful, and six years after opening it was taken into public ownership and the tolls were lifted. Despite this, the tollbooths remained in place, the only surviving examples of bridge tollbooths in London. Nicknamed "The Trembling Lady" due to its tendency to vibrate when large numbers of people walked over it, signs at the entrances to the bridge warning troops from the nearby Chelsea Barracks to break step while crossing the bridge are still in place.

With a roadway only 27 feet (8.2 m) wide and serious structural weaknesses, the bridge was poorly equipped to cope with the advent of the motor vehicle in the 20th century. Despite repeated proposals to demolish or pedestrianise it, the bridge has remained open to vehicles throughout its existence other than for brief periods during repairs, and is one of only two Thames road bridges in central London never to have been replaced. Despite the strengthening of the structure by Bazalgette and the Greater London Council, the structural soundness of the bridge has deteriorated since it was built, and a series of increasingly strict traffic control measures have been imposed on the bridge in an effort to limit the number of vehicles using it and thus prolong its lifespan. Due to these measures, it is the least busy Thames road bridge in London other than the little used Southwark Bridge. However, the condition of the bridge continues to deteriorate due to traffic load and severe rotting of the timber deck structure caused by the urine of the many dogs using it as a route to nearby Battersea Park.

In 1992 the bridge was repainted and rewired, and now has an unusual colour scheme designed to increase its visibility in poor lighting conditions and hence avoid damage from collisions with shipping, and is illuminated by 4,000 bulbs at night. It is now one of West London's most striking landmarks.

Background

The historic industrial town of Chelsea on the north bank of the River Thames about 3 miles (4.8 km) west of Westminster, and the rich farming village of Battersea facing it on the south bank, had been linked by the modest wooden Battersea Bridge since 1771.[3] In 1842 the Commission of Woods, Forests, and Land Revenues recommended the building of an embankment at Chelsea to free new land for development, and proposed the building of a new bridge downstream of Battersea Bridge and the replacement of Battersea Bridge with a more modern structure.[4] Work on the Chelsea Embankment began in 1862, and work on the Victoria Bridge (later renamed Chelsea Bridge), a short distance downstream of Battersea Bridge, began in 1851 and was completed in 1858.[5] The proposal to demolish Battersea Bridge was meanwhile abandoned.[4]

Although Chelsea and Battersea were now linked by two bridges, by the mid 19th century the wooden Battersea Bridge had become dilapidated and was considered unsafe and unpopular.[6] The newer Victoria Bridge, meanwhile, suffered severe congestion. In 1860, Prince Albert suggested that a new tollbridge built between the two existing bridges would be profitable,[7] and in the early 1860s the Albert Bridge Company was created with the aim of building a new bridge.[8] An 1863 proposal was blocked by strong opposition from the operators of Battersea Bridge, less than 500 yards (460 m) from the site proposed for the new bridge and concerned at potential loss of custom.[8] A compromise was reached, and in 1864 a new Act of Parliament was passed, authorising the new bridge on condition that it was completed within five years,[9] but compelling the Albert Bridge Company to purchase Battersea Bridge at the time of the new bridge's opening and to compensate the owners of Battersea Bridge with £3,000 (about £373,000 as of 2024) per annum until the new bridge opened.[10][11]

The Albert Bridge Company appointed Rowland Mason Ordish as designer for the new bridge.[8] Ordish was a leading architectural engineer of the period, and had already worked on the Royal Albert Hall, St Pancras railway station, the Crystal Palace and Holborn Viaduct.[8] The bridge was to be built using the Ordish–Lefeuvre Principle, an early form of cable-stayed bridge design which Ordish had patented in 1858.[7] Ordish's design differed from conventional suspension bridges in that, while as with a conventional suspension bridge a parabolic cable supported the centre of the bridge, 32 inclined stays supported the remainder of the bridge's load.[12] Each stay consisted of a flat wrought iron bar attached to the bridge deck, and a wire rope composed of 1000 1⁄10-inch (2.5 mm) diameter wires joining the wrought iron bar to one of the four octagonal support columns.[13]

Design and construction

Although authorised in 1864, the start of work on the bridge was delayed due to negotiations regarding the proposed Chelsea Embankment, as the design of the bridge could not be finalised until the exact layout of the new roads being built on the north bank of the river were agreed.[9] While plans for the Chelsea Embankment were debated, Ordish built the Franz Joseph Bridge over the Vltava in Prague to the same design as that intended for the Albert Bridge.[14][n 1]

In 1869, the time limit given by the 1864 Act to build the bridge expired, yet delays caused by the Chelsea Embankment project meant work had not yet even begun, and a new Act of Parliament was required to extend the time limit for completion of the project.[9] In 1870 work finally began, with construction expected to take roughly a year and to cost £70,000 (about £8,168,000 as of 2024).[11][14] In the event, construction took over three years and cost £200,000 (about £22,384,000 as of 2024).[9][11] It was intended to open the bridge and the Chelsea Embankment in a joint ceremony in 1874; however, the Albert Bridge Company was keen to start recouping the substantially higher than expected costs, and the bridge opened with no formal ceremony on 23 August 1873, almost ten years after it had been authorised.[14] As agreed in the Act authorising the construction of the new bridge, at this time Battersea Bridge was bought outright by the Albert Bridge Company.[8][15]

Ordish's bridge was 41 feet (12 m) wide and 710 feet (220 m) long, with a 384-foot-9-inch (117.27 m) central span.[10] The deck was supported by 32 rigid steel rods suspended from four octagonal cast iron towers, with the towers resting on cast iron piers.[9] The four piers were cast at Battersea and floated down the river into position, at which time they were filled with concrete; at the time they were the largest castings ever made.[9][14] Unlike most other suspension bridges of the time, the towers were positioned outside the bridge to avoid causing any obstruction to the roadway.[14] At each end of the bridge were a pair of tollbooths with a bar between them, to prevent people entering the bridge without paying.[14]

The bridge became nicknamed "The Trembling Lady" due to its tendency to vibrate, particularly when used by troops from the nearby Chelsea Barracks.[16] Concerns about the risks of mechanical resonance effects on suspension bridges, following the 1831 collapse of the Broughton Suspension Bridge and the 1850 collapse of Angers Bridge, led to warning notices being placed on the bridge warning troops to break step when crossing the bridge;[17] although the barracks closed in 2008, the warning signs are still in place today.[13][n 2]

Transfer to public ownership

The bridge was catastrophically unsuccessful financially. By the time the new bridge eventually opened the Albert Bridge Company had been paying compensation to the Battersea Bridge Company for nine years, and on completion of the bridge became liable for the costs of repairing the dilapidated and dangerous Battersea Bridge.[18] The costs of subsidising Battersea Bridge drained funds intended for the building of wide approach roads, making the bridge difficult to reach.[4] Located slightly further from central London than neighbouring Victoria (Chelsea) Bridge, demand for the new bridge was lower than expected, and in the first nine months of its operation it raised only £2,085 (about £245,000 as of 2024) in tolls.[11][18]

In 1877 the Metropolis Toll Bridges Act was passed, which allowed the Metropolitan Board of Works to buy all London bridges between Hammersmith and Waterloo bridges and free them from tolls.[19] In 1879, Albert Bridge, which had cost £200,000 to build, was bought by the Board of Works along with Battersea Bridge for a combined cost of £170,000 (about £21,833,000 as of 2024).[11][20] The tolls were removed from both bridges on 24 May 1879.[7] The octagonal tollbooths were left in place, and today are the only surviving bridge tollbooths in London.[21]

Structural weaknesses

In 1884 the Board of Works' Chief Engineer Sir Joseph Bazalgette conducted an inspection of the bridge and found that the steel rods were already showing serious signs of corrosion.[16] Over the next three years the steel staying rods were augmented with steel chains, giving it an appearance more closely resembling a conventional suspension bridge,[13][22] and a new timber deck was laid, at a total cost of £25,000 (about £3,292,000 as of 2024).[7][11] Despite these improvements, Bazalgette was still concerned about the bridge's structural integrity and a weight limit of 5 tons was imposed on vehicles using the bridge.[14]

With a roadway only 27 feet (8.2 m) wide and subject to weight restrictions from early on, the bridge was ill-suited to the advent of motorised transport in the 20th century. In 1926 the Royal Commission on Cross-River Traffic recommended demolition and rebuilding of the bridge to carry four lanes of traffic, but the plan was not carried out due to a shortage of funds in the Great Depression.[23] The bridge continued to deteriorate, and in 1935 the weight limit was reduced to 2 tons.[23]

Due to its ongoing structural weaknesses, in 1957 the London County Council proposed replacing the bridge with a more conventional design. A protest campaign led by John Betjeman led to the proposal being withdrawn, but there continued to be serious concerns about the integrity of the bridge.[16] In 1964 an experimental tidal flow scheme was introduced, in which only northbound traffic was permitted to use the bridge in the mornings and only southbound traffic in the evenings.[14] However, the bridge continued to deteriorate, and in 1970 the Greater London Council (GLC) sought and obtained consent to strengthen the bridge. In April 1972 the bridge closed for works to be carried out.[14]

Pedestrianised park proposal

The GLC's solution entailed adding two concrete piers in the middle of the river, supporting the central span and turning the central section of the bridge into a beam bridge.[24] Additionally, the main girder was strengthened and a lightweight replacement deck laid. The measures were only intended to be temporary, to allow the bridge to remain open for five years while a replacement was discussed; the GLC estimated that they would last for a maximum of 30 years and that the bridge would shortly need to be closed or replaced.[25]

In early 1973 the Architectural Review submitted a proposal to convert the bridge into a landscaped public park and pedestrian footpath across the river.[26] The proposal proved very popular with the area's residents, and in May 1973 a campaign led by John Betjeman, Sybil Thorndike and Laurie Lee raised a petition of 2,000 signatures for the bridge to be permanently closed to traffic on its reopening.[24] Although reopening the bridge to traffic in July 1973, the GLC announced their intention to proceed with the Architectural Review scheme and to close it permanently to traffic once legal matters had been dealt with.[24][n 3]

The Royal Automobile Club campaigned vigorously against the pedestrianisation proposal. A publicity campaign fronted by actress Diana Dors in favour of reopening the bridge was launched, whilst a lobbying group of local residents led by poet Robert Graves campaigned in support of the GLC's plan.[16] Graves's campaign collected over a thousand signatures in support, but was attacked vigourously by the British Road Federation, who derided the apparent evidence of public support for the scheme as "sending a lot of students around to council flats [where] most people will sign anything without knowing what it is all about".[25] A public enquiry of 1974 recommended that the bridge remain open to avoid causing congestion on neighbouring bridges, and the bridge remained open to traffic with the tidal flow and 2-ton weight limit in place.[24]

Present day

In 1990 the tidal flow system was abandoned and the bridge was converted back to two way traffic. A traffic island was installed on the south end of the bridge to prevent larger vehicles from using the bridge. In the early years of the 21st century the Chelsea area experienced a growth in the popularity of large four-wheel drive cars (so-called Chelsea tractors), many of which were over the 2 ton weight limit; it was estimated that 1⁄3 of all vehicles using the bridge were over the weight limit.[27] In July 2006 the 27-foot (8.2 m) wide roadway was narrowed to a single lane in each direction to reduce the load on the bridge.[28] Red and white plastic barriers have been erected along the roadway in an effort to protect the structure from damage caused by cars.[29]

Between 1905 and 1981 Albert Bridge had been painted in a uniform green colour and in 1981 was repainted yellow, but in 1992 the bridge underwent significant redecoration and rewiring.[30] Partially as a result, it is now a major landmark of west London. The bridge is painted in a scheme of pink, blue and green, intended to increase visibility in fog and murky light and hence reduce the risks of shipping colliding with the fragile structure during the day.[31] At night, a network of 4,000 low-voltage tungsten-halogen bulbs illuminate the bridge; in 1993 the innovative use of long-life low-energy lighting was commended by Mary Archer, at the time Chairwoman of the National Energy Foundation.[17] Its distinctive and striking current appearance has led to its being used as a backdrop for numerous films set in the Chelsea area, such as Absolute Beginners, Sliding Doors and Maybe Baby.[26]

Aside from Tower Bridge, built in 1894, Albert Bridge is now the only Thames road bridge in central London never to have been replaced.[9] Despite being intended as a temporary measure to be removed in 1978, the concrete central piers remain in place,[17] and although in 1974 the bridge's lifespan was estimated at a maximum of 30 years, the bridge is still standing and still operational.[25] The bridge was given protection as a Grade II* listed structure in 1975, granting it protection against further significant alteration without consultation.[32] Despite this, the bridge continues to deteriorate. While proposals have been drawn up by Kensington and Chelsea Council to repair and rescue the bridge,[29] as of March 2008 funds for the repairs were unavailable.[33] As well as structural damage caused by traffic, the timbers underpinning the deck are being seriously rotted by the urine of dogs crossing the bridge to and from nearby Battersea Park.[34][n 4] With multiple measures in place to reduce traffic flow and prolong the life of the bridge, as of 2009 it carries approximately 19,000 vehicles per day, the lowest usage of any Thames road bridge in London other than the little-used Southwark Bridge.[35]

Notes and references

- Notes

- ^ Damaged during the Second World War, the Franz Joseph Bridge was replaced by a more conventional bridge in the 1950s. Albert Bridge and the Franz Joseph Bridge were the only significant bridges built using the Ordish–Lefeuvre Principle; a third smaller Ordish–Lefeuvre Principle bridge was also built in Singapore.

- ^ A similar resonance effect caused the closure of the nearby Millennium Bridge in 2000 shortly after its opening.

- ^ A modified form of the Architectural Review design was used in 1999 for the Green Bridge, carrying Mile End Park over Mile End Road in East London.

- ^ Due to the lack of large open spaces on the north side of the river in this area large numbers of dogs cross daily to be walked in Battersea Park.

- References

- ^ Thames Bridges Heights, Port of London Authority, retrieved 2009-05-25

- ^ Cookson 2006, p. 316

- ^ Matthews 2008, p. 65

- ^ a b c Roberts 2005, p. 130

- ^ Roberts 2005, p. 112

- ^ Roberts 2005, p. 63

- ^ a b c d Davenport 2006, p. 71

- ^ a b c d e Matthews 2008, p. 71

- ^ a b c d e f g Cookson 2006, p. 126

- ^ a b Davenport 2006, p. 72

- ^ a b c d e f UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 38

- ^ a b c Tilly 2002, p. 217

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Matthews 2008, p. 72

- ^ Cookson 2006, p. 123

- ^ a b c d Cookson 2006, p. 127

- ^ a b c Cookson 2006, p. 130

- ^ a b Pay, Lloyd & Waldegrave 2009, p. 70

- ^ Cookson 2006, p. 147

- ^ "The Freeing of the Bridges", The Times, p. 12, 1880-06-28

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Quinn 2008, p. 237

- ^ Roberts 2005, p. 131

- ^ a b Roberts 2005, p. 132

- ^ a b c d Matthews 2008, p. 73

- ^ a b c Cookson 2006, p. 128

- ^ a b Roberts 2005, p. 133

- ^ Temko, Ned (2006-08-20), "Chelsea choked by its tractors", The Guardian, retrieved 2009-06-04

- ^ Albert Bridge feeling the strain, BBC News, 2006-07-28, retrieved 2009-06-04

- ^ a b "Albert Bridge undergoes restoration study". Builder & Engineer. London. 2008-03-17. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ^ Roberts 2005, p. 135

- ^ Cookson 2006, p. 129

- ^ Historic England. "Details from listed building database ({{{num}}})". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ Paige, Elaine (2008-03-02), "What's a girl to do against all this blah?", Daily Telegraph, retrieved 2009-06-04

- ^ Roberts 2005, p. 134

- ^ Pay, Lloyd & Waldegrave 2009, p. 71

- Bibliography

- Cookson, Brian (2006), Crossing the River, Edinburgh: Mainstream, ISBN 1 840189 76 2, OCLC 63400905

- Davenport, Neil (2006), Thames Bridges: From Dartford to the Source, Kettering: Silver Link Publishing, ISBN 1 857942 29 9

- Matthews, Peter (2008), London's Bridges, Oxford: Shire, ISBN 978 0 7478 0679 0, OCLC 213309491

- Pay, Ian; Lloyd, Sampson; Waldegrave, Keith (2009), London's Bridges: Crossing the Royal River, Wisley: Artists' and Photographers' Press, ISBN 978 1 9043 3290 9, OCLC 280442308

- Quinn, Tom (2008), London's Strangest Tales, London: Anova Books, ISBN 1 861059 76 0

- Roberts, Chris (2005), Cross River Traffic, London: Granta, ISBN 1 862078 00 9

- Smith, Denis (2001), Civil Engineering Heritage London and the Thames Valley, London: Thomas Telford, ISBN 0 7277 2876 8

- Tilly, Graham (2002), Conservation of Bridges, Didcot: Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0 419259 10 4

Further reading

- Loobet, Patrick Battersea Past, 2002, pp48–49. Historical Publications Ltd. ISBN 0-948667-76-1