For the consideration of my esteemed fellow editors (just a demo, feel free to revert): See how clean the wikitext is with {r}. Adopting "S" for Smith since it's so common. |

ditto for Fuhrmann; one big advantage of {r} is that it's compatible with the regular <ref></ref> syntax; if an editor doesn't understant {r} and codes e.g. <ref name=F/> instead, it works fine |

||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

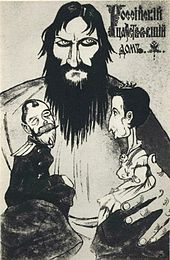

[[File:Makarij, Theofan of Poltava and Rasputin, 1909 03.jpg|thumb|upright=1|Makary, [[Vassili Dimitrievitch Bystrov|Theophanes of Poltava]] and Rasputin]] |

[[File:Makarij, Theofan of Poltava and Rasputin, 1909 03.jpg|thumb|upright=1|Makary, [[Vassili Dimitrievitch Bystrov|Theophanes of Poltava]] and Rasputin]] |

||

Rasputin was born a peasant in the small village of [[Pokrovskoye, Tyumen Oblast|Pokrovskoye]], along the [[Tura River]] in the [[Tobolsk]] ''[[guberniya]]'' (now [[Tyumen Oblast]]) in [[Siberia]].<ref name = "Wilson">Colin Wilson, ''Rasputin and the Fall of the Romanovs'', Arthur Baker Limited, 1964, p. 23-26.</ref> According to official records, he was born on {{OldStyleDate|21 January|1869|9 January}}, and christened the following day. |

Rasputin was born a peasant in the small village of [[Pokrovskoye, Tyumen Oblast|Pokrovskoye]], along the [[Tura River]] in the [[Tobolsk]] ''[[guberniya]]'' (now [[Tyumen Oblast]]) in [[Siberia]].<ref name = "Wilson">Colin Wilson, ''Rasputin and the Fall of the Romanovs'', Arthur Baker Limited, 1964, p. 23-26.</ref> According to official records, he was born on {{OldStyleDate|21 January|1869|9 January}}, and christened the following day.{{r|F|p=7}} He was named for [[St. Gregory of Nyssa]], whose feast was celebrated on January 10.{{r|S|p=14}} |

||

There are few records of Rasputin's parents. His father, Efim (sometimes spelled Yefim), was a peasant farmer and church elder who had been born in Pokrovskoye in 1842, and married Rasputin's mother, Anna Parshukova, in 1863. Efim also worked as a government courier, ferrying people and goods between [[Tobolsk]] and [[Tyumen]] |

There are few records of Rasputin's parents. His father, Efim (sometimes spelled Yefim), was a peasant farmer and church elder who had been born in Pokrovskoye in 1842, and married Rasputin's mother, Anna Parshukova, in 1863. Efim also worked as a government courier, ferrying people and goods between [[Tobolsk]] and [[Tyumen]]{{r|F|p=6}}{{r|S|p=14}} The couple had seven other children, all of whom died in infancy and early childhood. There may have been a ninth child, Feodosiya. According to historian Joseph T. Fuhrmann, Rasputin was certainly close to Fyeodosiya and was godfather to her children, but "the records that have survived do not permit us to say more than that."{{r|F|p=6}} |

||

According to historian Douglas Smith, Rasputin's youth and early adulthood are "a black hole about which we know almost nothing," though the lack of reliable sources and information did not stop others from fabricating stories about his parents and his youth after Rasputin's rise to fame.{{r|S|p=14-15}} Historians agree, however, that like most Siberian peasants, including his mother and father, Rasputin was never formally educated, and he remained illiterate well into his early adulthood.{{r|S|p=14}} |

According to historian Douglas Smith, Rasputin's youth and early adulthood are "a black hole about which we know almost nothing," though the lack of reliable sources and information did not stop others from fabricating stories about his parents and his youth after Rasputin's rise to fame.{{r|S|p=14-15}} Historians agree, however, that like most Siberian peasants, including his mother and father, Rasputin was never formally educated, and he remained illiterate well into his early adulthood.{{r|S|p=14}}{{r|F|p=9}} Local archival records suggest that he had a somewhat unruly youth - possibly involving drinking, small thefts, and disrespect for local authorities - but contain no evidence of his being charged with stealing horses, blasphemy, or bearing false witness, all major crimes that he was later rumored to have committed as a young man.{{r|S|p=16-17}} |

||

In 1886, Rasputin travelled to [[Abalak]], where he met a peasant girl named Praskovya Dubrovina. After a courtship of several months, they married in February 1887. Praskovya remained in Pokrovskoye throughout Rasputin's later travels and rise to prominence, and remained devoted to him until his death. The couple had seven children, though only 3 survived to adulthood: Dmitry (b. 1895), Maria (b. 1898) and Varvara (b. 1900).{{r|S|p=17-18}} |

In 1886, Rasputin travelled to [[Abalak]], where he met a peasant girl named Praskovya Dubrovina. After a courtship of several months, they married in February 1887. Praskovya remained in Pokrovskoye throughout Rasputin's later travels and rise to prominence, and remained devoted to him until his death. The couple had seven children, though only 3 survived to adulthood: Dmitry (b. 1895), Maria (b. 1898) and Varvara (b. 1900).{{r|S|p=17-18}} |

||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

==Religious conversion== |

==Religious conversion== |

||

In 1897, Rasputin developed a renewed interest in religion, and left Pokrovskoye to go on a pilgrimage. His reasons for doing so are unclear: according to some sources, Rasputin left the village to escape punishment for his role in a horse theft. |

In 1897, Rasputin developed a renewed interest in religion, and left Pokrovskoye to go on a pilgrimage. His reasons for doing so are unclear: according to some sources, Rasputin left the village to escape punishment for his role in a horse theft.{{r|F|p=14}} Other sources suggest that he had a vision - either of the [[Virgin Mary]], or of [[Simeon of Verkhoturye|St. Simeon of Verkhoturye]] - while still others suggest that Rasputin's pilgrimage was inspired by his interactions with a young theological student, Melity Zaborovsky.{{r|S|p=20-21}} Whatever his reasons, Rasputin's departure was a radical life change: he was twenty-eight, had been married ten years, and had an infant son with another child on the way. According to Douglas Smith, his decision "could only have been occasioned by some sort of emotional or spiritual crisis."{{r|S|p=21}} |

||

Rasputin had undertaken earlier, shorter pilgrimages to the Holy Znamensky Monastery at Abalak and to Tobolsk's cathedral, but his visit to the St. Nicholas Monastery at Verkhoturye in 1897 was transformative.{{r|S|p=22}} There, he met and was "profoundly humbled" by a ''starets'' (elder) known as Makary. Rasputin may have spent several months at Verkhoturye, and it was perhaps here that he learned to read and write, but he later complained about the monastery itself, claiming that some of the monks engaged in homosexuality and criticizing monastic life as too coercive.{{r|S|p=23-25}} He returned to Pokrovskoye a changed man, looking disheveled and behaving differently than he had before. He became a vegetarian, swore off alcohol, and prayed and sang much more fervently than he had in the past. |

Rasputin had undertaken earlier, shorter pilgrimages to the Holy Znamensky Monastery at Abalak and to Tobolsk's cathedral, but his visit to the St. Nicholas Monastery at Verkhoturye in 1897 was transformative.{{r|S|p=22}} There, he met and was "profoundly humbled" by a ''starets'' (elder) known as Makary. Rasputin may have spent several months at Verkhoturye, and it was perhaps here that he learned to read and write, but he later complained about the monastery itself, claiming that some of the monks engaged in homosexuality and criticizing monastic life as too coercive.{{r|S|p=23-25}} He returned to Pokrovskoye a changed man, looking disheveled and behaving differently than he had before. He became a vegetarian, swore off alcohol, and prayed and sang much more fervently than he had in the past.{{r|F|p=17}} |

||

Rasputin would spend the years that followed living as a ''Stranniki,'' (a holy wanderer, or pilgrim), leaving Pokrovskoye for months or even years at a time to wander the country and visit a variety of different holy sites.{{r|S|p=23,26}} It is possible that Rasputin wandered as far [[Mount Athos|Athos]], Greece - the center of Orthodox monastic life - in 1900.{{r|S|p=25-26}} |

Rasputin would spend the years that followed living as a ''Stranniki,'' (a holy wanderer, or pilgrim), leaving Pokrovskoye for months or even years at a time to wander the country and visit a variety of different holy sites.{{r|S|p=23,26}} It is possible that Rasputin wandered as far [[Mount Athos|Athos]], Greece - the center of Orthodox monastic life - in 1900.{{r|S|p=25-26}} |

||

By the early 1900s, Rasputin had developed a small circle of [[acolytes]], primarily family members and other local peasants, who prayed with him on Sundays and other holy days when he was in Pokrovskoye. Building a makeshift chapel in Efim's root cellar - Rasputin was still living within his fathers household at the time - the group help secret prayer meetings there. These meetings were the subject of some suspicion and hostility from the village priest and other villagers. It was rumored that female followers were ceremonially washing him before each meeting, that the group sang strange songs that the villagers had not heard before, and even that Rasputin had joined the [[Khlysty]], a religious sect whose ecstatic rituals were rumored to included self-[[flagellation]] and sexual orgies.{{r|S|p=28}} |

By the early 1900s, Rasputin had developed a small circle of [[acolytes]], primarily family members and other local peasants, who prayed with him on Sundays and other holy days when he was in Pokrovskoye. Building a makeshift chapel in Efim's root cellar - Rasputin was still living within his fathers household at the time - the group help secret prayer meetings there. These meetings were the subject of some suspicion and hostility from the village priest and other villagers. It was rumored that female followers were ceremonially washing him before each meeting, that the group sang strange songs that the villagers had not heard before, and even that Rasputin had joined the [[Khlysty]], a religious sect whose ecstatic rituals were rumored to included self-[[flagellation]] and sexual orgies.{{r|S|p=28}}{{r|F|p=19-20}} According to historian Joseph Fuhrmann, however, "repeated investigations failed to establish that Rasputin was ever a member of the sect," and rumors that he was a Khlyst appear to have been unfounded.{{r|F|p=20}} |

||

==Rise to prominence== |

==Rise to prominence== |

||

Word of Rasputin's activity and charisma began to spread in Siberia during the early 1900s.{{r|S|p=28}} Sometime between 1902 and 1904, he travelled to the city of [[Kazan]] on the [[Volga river]], where he acquired a reputation as a wise and perceptive ''starets,'' or holy man, who could help people resolve their spiritual crises and anxieties.{{r|S|p=50}} Despite rumors that Rasputin was having sex with some of his female followers, |

Word of Rasputin's activity and charisma began to spread in Siberia during the early 1900s.{{r|S|p=28}} Sometime between 1902 and 1904, he travelled to the city of [[Kazan]] on the [[Volga river]], where he acquired a reputation as a wise and perceptive ''starets,'' or holy man, who could help people resolve their spiritual crises and anxieties.{{r|S|p=50}} Despite rumors that Rasputin was having sex with some of his female followers,{{r|F|p=25}} he won over the father superior of the Seven Lakes Monastery outside Kazan, as well as a local church officials [[Archimandrite]] Andrei and Bishop Chrysthanos, who gave him a letter of recommendation to Bishop Sergei, the rector of the St. Petersburg Theological Seminary at the [[Alexander Nevsky Monastery]], and arranged for him to travel to St. Petersburg, either in 1903 or in the winter of 1904-1905.{{r|S|p=50-52}}{{r|F|p=26}}<ref name="Radzinsky2010">{{cite book|author=Edvard Radzinsky|title=The Rasputin File|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HNBR5R8PDyQC&pg=PA47|date=12 May 2010|publisher=Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group|isbn=978-0-307-75466-0|}}</ref>{{rp|47-8}}{{r|F|p=26}} |

||

Upon meeting Sergei at the Nevsky Monastery, Rasputin was introduced to a number of different church leaders, including Archimandrite Feofan, who was the inspector of the theological seminary, was well-connected in St. Petersburg society, and later served as confessor to the Tsar and his wife. |

Upon meeting Sergei at the Nevsky Monastery, Rasputin was introduced to a number of different church leaders, including Archimandrite Feofan, who was the inspector of the theological seminary, was well-connected in St. Petersburg society, and later served as confessor to the Tsar and his wife.{{r|F|p=29}}{{r|S|p=66}} Feofan was so impressed with Rasputin that he invited him to stay in his home, and became one of Rasputin's most important and influential friends in St. Petersburg.{{r|F|p=29}} |

||

According to Joseph T. Fuhrmann, Rasputin stayed in St. Petersburg for only a few months on his first visit, and returned to Prokovskoye in the fall of 1903. |

According to Joseph T. Fuhrmann, Rasputin stayed in St. Petersburg for only a few months on his first visit, and returned to Prokovskoye in the fall of 1903.{{r|F|p=30}} Historian Douglas Smith, however, argues that it is impossible to know whether Rasputin stayed in St. Petersburg or returned to Prokovskoye at some point between his first arrival there and 1905.{{r|S|p=65}} Regardless, by 1905 Rasputin had formed friendships with several members of the aristocracy, including the "Black Princesses," [[Princess Milica of Montenegro|Militsa]] and [[Princess Anastasia of Montenegro|Anatasia]] of [[Montenegro]], who had married the Tsar's cousins ([[Grand Duke Peter Nikolaevich of Russia|Grand Duke Peter Nikolaevich]] and [[Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich of Russia (1856–1929)|Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich]]), and were instrumental in introducing Rasputin to the Tsar and his family.{{r|S|p=66}}{{r|F|p=29-30,39}} |

||

Rasputin first met the Tsar on November 1, 1905, at the [[Peterhof Palace]]. The tsar recorded the event in his diary, writing that he and Alexandra had "made the acquaintance of a man of God - Grigory, from Tobolsk province."{{r|S|p=65}} Rasputin would not meet the Tsar and his wife again for some months: he returned to Prokovskoye shortly after meeting their first meeting, and did not return to St. Petersburg until July 1906. During this time, however, Rasputin wrote several letters to the Tsar.{{r|S|p=69-76}} |

Rasputin first met the Tsar on November 1, 1905, at the [[Peterhof Palace]]. The tsar recorded the event in his diary, writing that he and Alexandra had "made the acquaintance of a man of God - Grigory, from Tobolsk province."{{r|S|p=65}} Rasputin would not meet the Tsar and his wife again for some months: he returned to Prokovskoye shortly after meeting their first meeting, and did not return to St. Petersburg until July 1906. During this time, however, Rasputin wrote several letters to the Tsar.{{r|S|p=69-76}} |

||

| Line 155: | Line 155: | ||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RhXyCwAAQBAJ|date=22 November 2016 |

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RhXyCwAAQBAJ|date=22 November 2016 |

||

|publisher=Farrar, Straus and Giroux|isbn=978-0-374-71123-8}} |

|publisher=Farrar, Straus and Giroux|isbn=978-0-374-71123-8}} |

||

</ref> |

|||

<ref name="F">{{cite book |

|||

|author=Joseph T. Fuhrmann|title=Rasputin: The Untold Story |

|||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=g8rUz8nu4VIC|date=24 September 2012 |

|||

|publisher=Wiley|isbn=978-1-118-23985-8}} |

|||

</ref> |

</ref> |

||

Revision as of 18:15, 5 March 2017

Grigori Rasputin | |

|---|---|

| File:Григорий Распутин (1914-1916)b.jpg Grigori Rasputin | |

| Born | 22 January 1869 |

| Died | 29 or 30 December 1916 (aged 47) Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Cause of death | Homicide |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Other names | The Mad Monk The Black Monk |

| Title | Father Grigori |

| Spouse | Praskovia Fedorovna Dubrovina |

| Children | Dmitri (1895-1937) Matryona (1898-1977) Varvara (1900-1925) |

| Parent(s) | Efim Rasputin Anna Parshukova |

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin (Russian: Григорий Ефимович Распутин [ɡrʲɪˈɡorʲɪj jɪˈfʲiməvʲɪtɕ rɐˈsputʲɪn]) (21 January [O.S. 9 January] 1869 – 29 or 30 December [O.S. 16 December] 1916) was a Russian mystic and self-proclaimed holy man who befriended the family of Tsar Nicholas II and gained considerable influence in late imperial Russia.

Born to a peasant family in the Siberian village of Pokrovskoye, Rasputin had a religious conversion experience after taking a pilgrimage to a monastery in 1897. He has been described as a monk or as a "strannik" (wanderer, or pilgrim), though he held no official position in the Russian Orthodox Church. After traveling to St. Petersburg, either in 1903 or the winter of 1904-5, Rasputin captivated some church and social leaders. He became a society figure, and met the Tsar in November 1905.

In late 1906, Rasputin began acting as a healer for the Nicholas II and Alexandra's son Alexei, who suffered from hemophilia and was Nicholas' only heir (Tsarevitch). At court, he was a divisive figure, seen by some Russians as a mystic, visionary, and prophet, and by others as a religious charlatan. The high point of Rasputin's power was in 1915, when Nicholas II left St Petersburg to oversee Russian armies fighting World War I, increasing both Alexandra and Rasputin's influence. As Russian defeats in the war mounted, however, both Rasputin and Alexandra became increasingly unpopular. On the night of 29-30 December [O.S. 16-17 December] 1916 Rasputin was assassinated by a group of conservative noblemen who opposed his influence over Alexandra and the Tsar.

Some writers have suggested that Rasputin helped to discredit the tsarist government, and thus helped to precipitate the Russian Revolution and the fall of the Romanov dynasty. Very little about Rasputin's life and influence is certain, however, as accounts have often been based on hearsay, rumor, and legend.

Early life

Rasputin was born a peasant in the small village of Pokrovskoye, along the Tura River in the Tobolsk guberniya (now Tyumen Oblast) in Siberia.[1] According to official records, he was born on 21 January [O.S. 9 January] 1869, and christened the following day.[2]: 7 He was named for St. Gregory of Nyssa, whose feast was celebrated on January 10.[3]: 14

There are few records of Rasputin's parents. His father, Efim (sometimes spelled Yefim), was a peasant farmer and church elder who had been born in Pokrovskoye in 1842, and married Rasputin's mother, Anna Parshukova, in 1863. Efim also worked as a government courier, ferrying people and goods between Tobolsk and Tyumen[2]: 6 [3]: 14 The couple had seven other children, all of whom died in infancy and early childhood. There may have been a ninth child, Feodosiya. According to historian Joseph T. Fuhrmann, Rasputin was certainly close to Fyeodosiya and was godfather to her children, but "the records that have survived do not permit us to say more than that."[2]: 6

According to historian Douglas Smith, Rasputin's youth and early adulthood are "a black hole about which we know almost nothing," though the lack of reliable sources and information did not stop others from fabricating stories about his parents and his youth after Rasputin's rise to fame.[3]: 14-15 Historians agree, however, that like most Siberian peasants, including his mother and father, Rasputin was never formally educated, and he remained illiterate well into his early adulthood.[3]: 14 [2]: 9 Local archival records suggest that he had a somewhat unruly youth - possibly involving drinking, small thefts, and disrespect for local authorities - but contain no evidence of his being charged with stealing horses, blasphemy, or bearing false witness, all major crimes that he was later rumored to have committed as a young man.[3]: 16-17

In 1886, Rasputin travelled to Abalak, where he met a peasant girl named Praskovya Dubrovina. After a courtship of several months, they married in February 1887. Praskovya remained in Pokrovskoye throughout Rasputin's later travels and rise to prominence, and remained devoted to him until his death. The couple had seven children, though only 3 survived to adulthood: Dmitry (b. 1895), Maria (b. 1898) and Varvara (b. 1900).[3]: 17-18

Religious conversion

In 1897, Rasputin developed a renewed interest in religion, and left Pokrovskoye to go on a pilgrimage. His reasons for doing so are unclear: according to some sources, Rasputin left the village to escape punishment for his role in a horse theft.[2]: 14 Other sources suggest that he had a vision - either of the Virgin Mary, or of St. Simeon of Verkhoturye - while still others suggest that Rasputin's pilgrimage was inspired by his interactions with a young theological student, Melity Zaborovsky.[3]: 20-21 Whatever his reasons, Rasputin's departure was a radical life change: he was twenty-eight, had been married ten years, and had an infant son with another child on the way. According to Douglas Smith, his decision "could only have been occasioned by some sort of emotional or spiritual crisis."[3]: 21

Rasputin had undertaken earlier, shorter pilgrimages to the Holy Znamensky Monastery at Abalak and to Tobolsk's cathedral, but his visit to the St. Nicholas Monastery at Verkhoturye in 1897 was transformative.[3]: 22 There, he met and was "profoundly humbled" by a starets (elder) known as Makary. Rasputin may have spent several months at Verkhoturye, and it was perhaps here that he learned to read and write, but he later complained about the monastery itself, claiming that some of the monks engaged in homosexuality and criticizing monastic life as too coercive.[3]: 23-25 He returned to Pokrovskoye a changed man, looking disheveled and behaving differently than he had before. He became a vegetarian, swore off alcohol, and prayed and sang much more fervently than he had in the past.[2]: 17

Rasputin would spend the years that followed living as a Stranniki, (a holy wanderer, or pilgrim), leaving Pokrovskoye for months or even years at a time to wander the country and visit a variety of different holy sites.[3]: 23,26 It is possible that Rasputin wandered as far Athos, Greece - the center of Orthodox monastic life - in 1900.[3]: 25-26

By the early 1900s, Rasputin had developed a small circle of acolytes, primarily family members and other local peasants, who prayed with him on Sundays and other holy days when he was in Pokrovskoye. Building a makeshift chapel in Efim's root cellar - Rasputin was still living within his fathers household at the time - the group help secret prayer meetings there. These meetings were the subject of some suspicion and hostility from the village priest and other villagers. It was rumored that female followers were ceremonially washing him before each meeting, that the group sang strange songs that the villagers had not heard before, and even that Rasputin had joined the Khlysty, a religious sect whose ecstatic rituals were rumored to included self-flagellation and sexual orgies.[3]: 28 [2]: 19-20 According to historian Joseph Fuhrmann, however, "repeated investigations failed to establish that Rasputin was ever a member of the sect," and rumors that he was a Khlyst appear to have been unfounded.[2]: 20

Rise to prominence

Word of Rasputin's activity and charisma began to spread in Siberia during the early 1900s.[3]: 28 Sometime between 1902 and 1904, he travelled to the city of Kazan on the Volga river, where he acquired a reputation as a wise and perceptive starets, or holy man, who could help people resolve their spiritual crises and anxieties.[3]: 50 Despite rumors that Rasputin was having sex with some of his female followers,[2]: 25 he won over the father superior of the Seven Lakes Monastery outside Kazan, as well as a local church officials Archimandrite Andrei and Bishop Chrysthanos, who gave him a letter of recommendation to Bishop Sergei, the rector of the St. Petersburg Theological Seminary at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery, and arranged for him to travel to St. Petersburg, either in 1903 or in the winter of 1904-1905.[3]: 50-52 [2]: 26 [4]: 47–8 [2]: 26

Upon meeting Sergei at the Nevsky Monastery, Rasputin was introduced to a number of different church leaders, including Archimandrite Feofan, who was the inspector of the theological seminary, was well-connected in St. Petersburg society, and later served as confessor to the Tsar and his wife.[2]: 29 [3]: 66 Feofan was so impressed with Rasputin that he invited him to stay in his home, and became one of Rasputin's most important and influential friends in St. Petersburg.[2]: 29

According to Joseph T. Fuhrmann, Rasputin stayed in St. Petersburg for only a few months on his first visit, and returned to Prokovskoye in the fall of 1903.[2]: 30 Historian Douglas Smith, however, argues that it is impossible to know whether Rasputin stayed in St. Petersburg or returned to Prokovskoye at some point between his first arrival there and 1905.[3]: 65 Regardless, by 1905 Rasputin had formed friendships with several members of the aristocracy, including the "Black Princesses," Militsa and Anatasia of Montenegro, who had married the Tsar's cousins (Grand Duke Peter Nikolaevich and Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich), and were instrumental in introducing Rasputin to the Tsar and his family.[3]: 66 [2]: 29-30,39

Rasputin first met the Tsar on November 1, 1905, at the Peterhof Palace. The tsar recorded the event in his diary, writing that he and Alexandra had "made the acquaintance of a man of God - Grigory, from Tobolsk province."[3]: 65 Rasputin would not meet the Tsar and his wife again for some months: he returned to Prokovskoye shortly after meeting their first meeting, and did not return to St. Petersburg until July 1906. During this time, however, Rasputin wrote several letters to the Tsar.[3]: 69-76

Healer to Alexei

Rasputin was wandering as a pilgrim in Siberia when he heard reports of Tsarevich Alexei's illness. It was not publicly known in 1904 that Alexei had haemophilia, a disease that was widespread among European royalty descended from the British Queen Victoria, who was Alexei's great-grandmother. When doctors could not help Alexei, the Tsarina looked everywhere for help, ultimately turning to her best friend, Anna Vyrubova, to secure the help of the charismatic peasant healer Rasputin in 1905.[5] He was said to possess the ability to heal through prayer and was indeed able to give the boy some relief, in spite of the doctors' prediction that he would die.[5] Every time the boy had an injury which caused him internal or external bleeding, the Tsarina called on Rasputin, and the Tsarevich subsequently got better.[citation needed] This made it appear that Rasputin was effectively healing him.

Skeptics[who?] have claimed that he did so by hypnosis.[citation needed] However, during a particularly grave crisis at Spała in Poland in 1912, Rasputin sent a telegram from his home in Siberia, which is believed to have contained advice to ease the suffering of the young prince. His pragmatic tips included suggestions such as "Don't let the doctors bother him too much; let him rest." This was thought to have helped Alexei to relax and allow the child's own natural healing process some room.[6] Others have made the less likely suggestion that he used leeches to attempt to treat the boy. As leech saliva contains anticoagulants such as hirudin, this treatment would most likely have exacerbated his haemophilia instead of providing relief. Diarmuid Jeffreys has pointed out that Rasputin's healing suggestions included halting the administration of aspirin, a then newly available (since 1899) pain-relieving (analgesic) "wonder drug". As aspirin is also an anticoagulant, this intervention would have worsened the hemarthrosis causing Alexei's joints' swelling and pain.[improper synthesis?][7]

The Tsar referred to Rasputin as "our friend" and a "holy man", a sign of the trust that the family had placed in him. Rasputin had a considerable personal and political influence on Alexandra,[8] and the Tsar and Tsarina considered him a man of God and a religious prophet. Alexandra came to believe that God spoke to her through Rasputin. Of course, this relationship can also be viewed in the context of the very strong, traditional, age-old bond between the Russian Orthodox Church and the Russian state leadership. Another important factor was probably the Tsarina's German-Protestant origin. She was definitely highly fascinated by her new Orthodox outlook — the Orthodox religion puts a great deal of faith in the healing powers of prayer.

Controversy

Rasputin soon became a controversial figure, becoming involved in a paradigm of sharp political struggle involving monarchist, anti-monarchist, revolutionary and other political forces and interests. He was accused by many eminent persons of various misdeeds, ranging from an unrestricted sexual life (including raping a nun)[9] to undue political domination over the royal family.[citation needed]

Even before his arrival in St. Petersburg in 1903, the city was wildly fascinated with mysticism and aristocrats were obsessed with anything occult.[10] While fascinated by him, the Saint Petersburg elite did not widely accept Rasputin. He did not fit in with the royal family, and he and the Russian Orthodox Church had a very strained relationship. The Holy Synod frequently attacked Rasputin, accusing him of a variety of immoral or evil practices. Because Rasputin was a court official, though, he and his apartment were under 24-hour surveillance, and, accordingly, there exists some credible evidence about his lifestyle in the form of the famous "staircase notes" — reports from police spies, which were not given only to the Tsar but also published in newspapers.

According to Rasputin's daughter, Maria, Rasputin did "look into" the Khlysty sect, but rejected it. One Khlyst practice was known as "rejoicing" (радение), a ritual which sought to overcome human sexual urges by engaging in group sexual activities so that, in consciously sinning together, the sin's power over the human was nullified.[11] Rasputin is said to have been particularly appalled by the belief that grace is found through self-flagellation.

Like many spiritually minded Russians, Rasputin spoke of salvation as depending less on the clergy and the church than on seeking the spirit of God within. He also maintained that sin and repentance were interdependent and necessary to salvation. Thus, he claimed that yielding to temptation (and, for him personally, this meant sex and alcohol), even for the purposes of humiliation (so as to dispel the sin of vanity), was needed to proceed to repentance and salvation. Rasputin was deeply opposed to war, both from a moral point of view and as something which was likely to lead to political catastrophe. During the years of World War I, Rasputin's increasing drunkenness, sexual promiscuity and willingness to accept bribes (in return for helping petitioners who flocked to his apartment), as well as his efforts to have his critics dismissed from their posts, made him appear increasingly cynical. Attaining divine grace through sin seems to have been one of the central secret doctrines which Rasputin preached to (and practiced with) his inner circle of society ladies.

During World War I, Rasputin became the focus of accusations of unpatriotic influence at court. The unpopular Tsarina, meanwhile, who was of German descent, was accused of acting as a spy in German employ.

When Rasputin expressed an interest in going to the front to bless the troops early in the war, the Commander-in-Chief, Grand Duke Nicholas, promised to hang him if he dared to show up there. Rasputin then claimed that he had a revelation that the Russian armies would not be successful until the Tsar personally took command. With this, the ill-prepared Tsar Nicholas proceeded to take personal command of the Russian army, with dire consequences for himself as well as for Russia.

While Tsar Nicholas II was away at war, Rasputin's influence over Tsarina Alexandra increased.[citation needed] He soon became her confidant and personal adviser, and also convinced her to fill some governmental offices with his own handpicked candidates. To further advance his power in the highest circles of Russian society, Rasputin cohabited with upper-class women in exchange for granting political favours. Because of World War I and the ossifying effects of feudalism and a meddling government bureaucracy, Russia's economy was declining at a very rapid rate. Many at the time laid the blame with Alexandra and with Rasputin, because of his influence over her. Here is an example:

Vladimir Purishkevich was an outspoken member of the Duma. On November 19, 1916, Purishkevich made a rousing speech in the Duma, in which he stated, "The tsar's ministers who have been turned into marionettes, marionettes whose threads have been taken firmly in hand by Rasputin and the Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna — the evil genius of Russia and the Tsarina ... who has remained a German on the Russian throne and alien to the country and its people." Felix Yusupov attended the speech and afterwards contacted Purishkevich, who quickly agreed to participate in the murder of Rasputin.[12]

Rasputin's influence over the royal family was used against him and the Romanovs by politicians and journalists who wanted to weaken the integrity of the dynasty, force the Tsar to give up his absolute political power and separate the Russian Orthodox Church from the state. Rasputin unintentionally contributed to their propaganda by having public disputes with clergy members, bragging about his ability to influence both the Tsar and Tsarina, and also by his dissolute and very public lifestyle. Nobles in influential positions around the Tsar, as well as some parties of the Duma, clamored for Rasputin's removal from the court. Perhaps inadvertently, Rasputin had added to the Tsar's subjects' diminishing respect for him.

Death

Assassination attempt

On 12 July [O.S. 29 June] 1914[13][14] Rasputin was stabbed in the stomach outside his home in Pokrovskoye by Khionia Guseva.[15] Guseva, a 33-year-old peasant woman, was said to be a follower of Iliodor, a "radical right-wing priest" who had fallen from favor with Rasputin, and Rasputin suspected Iliodor of complicity in the attack.[16] The Tsarina's own physician was sent to attend Rasputin[17] and he recovered after some weeks in the hospital. According to his daughter Maria, Rasputin was very much changed by the experience and began to drink alcohol. Guseva was committed as insane and never tried.[18]

Assassination

The murder of Rasputin has become something of a legend, some of it perhaps invented, embellished or simply misremembered by the very men who killed him, which is why it has become so difficult to discern the actual course of events. The date of Rasputin’s death is variously recorded as being either 17 December 1916 or 29 December 1916. This discrepancy arises due to the fact that the Gregorian calendar (New Style) was not introduced into Soviet Russia until 1918.[19] Using the Gregorian calendar the initial attempts to kill Rasputin may have commenced before midnight on 29 December though he may well have died in the early hours of 30 December 1916.[20][21] What is known is that having decided that Rasputin's influence over the Tsarina had made him a threat to the empire, a group of nobles led by Prince Felix Yusupov, the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, and the right-wing politician Vladimir Purishkevich apparently lured Rasputin to the Yusupovs' Moika Palace[22] by intimating that Yusupov's wife, Princess Irina, would be present and receiving friends (in point of fact, she was away in the Crimea).[23] The group led him down to the cellar, where they served him cakes and red wine laced with a large amount of cyanide. According to legend, Rasputin was unaffected, although Vasily Maklakov had supplied enough poison to kill five men. Conversely, Maria's account asserts that, if her father did eat or drink poison, it was not in the cakes or wine because, after the attack by Guseva, he suffered from hyperacidity and avoided anything with sugar. In fact, she expresses doubt that he was poisoned at all. It has been suggested, on the other hand, that Rasputin had developed an immunity to poison due to mithridatism.[24]

Determined to finish the job, Prince Yusupov became anxious about the possibility that Rasputin might live until the morning, leaving the conspirators no time to conceal his body. Yusupov ran upstairs to consult the others and then came back down to shoot Rasputin through the back with a revolver. Rasputin fell, and the company left the palace for a while. Yusupov, who had left without a coat, decided to return to get one, and while at the palace, he went to check on the body. Suddenly, Rasputin opened his eyes and lunged at Yusupov. He grabbed Yusupov and attempted to strangle him. At that moment, however, the other conspirators arrived and fired at Rasputin. After being hit three times in the back, he fell once more. As they neared his body, the party found that, remarkably, he was still alive, struggling to get up. They clubbed him into submission. Some accounts say that his killers also severed his penis (subsequently resulting in urban legends and claims that certain third parties were in possession of the organ).[25][26][27] After binding his body and wrapping him in a carpet, they threw him into the icy Neva River. He broke out of his bonds and the carpet wrapping him, but drowned in the river.[citation needed]

Three days later, Rasputin's body, poisoned, shot four times, badly beaten, and drowned, was recovered from the river. An autopsy established that the cause of death was drowning. It was found that he had indeed been poisoned, and that the poison alone should have been enough to kill him. There is a report that after his body was recovered, water was found in the lungs, supporting the idea that he was still alive before submersion into the partially frozen river.[28]

Subsequently, the Tsarina Alexandra buried Rasputin's body in the grounds of Tsarskoye Selo, but after the February Revolution, a group of workers from Saint Petersburg uncovered the remains, carried them into the nearby woods, and burned them. As the body was being burned, Rasputin appeared to sit up in the fire. His apparent attempts to move and get up thoroughly horrified bystanders. The effect can probably be attributed to improper cremation;[citation needed] since the body was in inexperienced hands, the tendons were probably not cut before burning. Consequently, when the body was heated, the tendons shrank, forcing the legs to bend and the body to bend at the waist, resulting in its appearing to sit up. This final happenstance only further fueled the legends and mysteries surrounding Rasputin, which continue to live on long after his death. The official report of his autopsy disappeared during the Joseph Stalin era, as did several research assistants who had seen it.[29]

Recent evidence

The details of the killing given by Felix Yusupov have never stood up to scrutiny. He changed his account several times; the statement given to the St. Petersburg police, the accounts given whilst in exile in the Crimea in 1917, his 1927 book, and finally the accounts given under oath to libel juries in 1934 and 1965 all differ to some extent, and until recently no other credible, evidence-based theories have been available.[citation needed]

According to the unpublished 1916 autopsy report by Professor Kossorotov, as well as subsequent reviews by Dr. Vladimir Zharov in 1993 and Professor Derrick Pounder in 2004/05, no active poison was found in Rasputin's stomach. A possible explanation would be that the cyanide in the cakes had vaporized due to the high temperatures during the baking in the oven.[citation needed]

It could not be determined with certainty that he drowned, as the water found in his lungs is a common non-specific autopsy finding. All three sources agree that Rasputin had been systematically beaten and attacked with a bladed weapon; but, most importantly, there were discrepancies regarding the number and caliber of handguns used.[citation needed]

Some writers haves speculated that British intelligence agents were involved in Rasputin's assassination. British intelligence reports, sent between London and Saint Petersburg in 1916, indicate that the British were not only extremely concerned about Rasputin's displacement of pro-British ministers in the Russian government but, even more importantly, his apparent insistence on withdrawing Russian troops from World War I. This withdrawal would have allowed the Germans to transfer their Eastern Front troops to the Western Front, leading to a massive outnumbering of the Allies, and threatening their defeat. Whether this was actually Rasputin's intent or whether he was simply concerned about the huge number of casualties (as the Tsarina's letters indicate) is in dispute, but it is clear that the British perceived him as a real threat to the war effort.[citation needed]

Newspaper reporter Michael Smith wrote in his book that British Secret Intelligence Bureau head Mansfield Cumming ordered three of his agents in Russia to eliminate Rasputin in December 1916.[30]

Daughter

Rasputin's daughter, Maria Rasputin (Matryona Rasputina) (1898–1977), emigrated to France after the October Revolution, and then to the U.S. There she worked as a dancer and then a tiger-trainer in a circus. She left memoirs[31] about her father, wherein she painted an almost saintly picture of him, insisting that most of the negative stories were based on slander and the misinterpretations of facts by his enemies.

In popular culture

Numerous film and stage productions have been based on the life of Rasputin.

Notes and citations

- ^ Colin Wilson, Rasputin and the Fall of the Romanovs, Arthur Baker Limited, 1964, p. 23-26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Joseph T. Fuhrmann (24 September 2012). Rasputin: The Untold Story. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-23985-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Douglas Smith (22 November 2016). Rasputin: Faith, Power, and the Twilight of the Romanovs. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-71123-8.

- ^ Edvard Radzinsky (12 May 2010). The Rasputin File. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-75466-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ a b Massie, p. 185.

- ^ Massie, p. 187.

- ^ Diarmuid Jeffreys (2004). Aspirin. The Remarkable Story of a Wonder Drug. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- ^ George King, The Last Empress: The Life and Times of Alexandra Feodorovna, Tsarina of Russia. Replica Books, 2001. ISBN 978-0-7351-0104-3

- ^ Thomas Szasz, A Lexicon of Lunacy: Metaphoric Malady, Moral Responsibility, and Psychiatry. Transaction Publisher, 2003. ISBN 978-0-7658-0506-5.[better source needed]

- ^ "Grigory Rasputin – Russiapedia History and mythology Prominent Russians". Russiapedia.rt.com. Retrieved 2 September 2012.[better source needed]

- ^ Radzinsky, p. 40.

- ^ Radzinsky, p. 434.

- ^ Assassination Attempt on Rasputin – 29 June 1914 | The British Newspaper Archive Blog. Blog.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. Retrieved on 15 July 2014.

- ^ FAVORITE OF TSAR STABBED BY WOMAN – Rasputin, Peasant Monk-Mystic, Said to be at the Point of Death. New York Times (14 July 1914). Retrieved on 15 July 2014.

- ^ Nelipa, p. 45.

- ^ Brenton, Tony (2017), Was Revolution Inevitable?: Turning Points of the Russian Revolution, Oxford University Press, p. 62, ISBN 9780190658939

- ^ The Tsar Sends His Own Physician to Attend the Court Favorite. New York Times. 15 July 1914

- ^ Moe, p. 277.

- ^ Gregorian calendar | Britannica.com

- ^ Grigory Yefimovich Rasputin | Russian mystic | Britannica.com

- ^ http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/RUSrasputin.htm

- ^ Farquhar, Michael (2001). A Treasure of Royal Scandals, p.197. Penguin Books, New York. ISBN 0-7394-2025-9.

- ^ Sulzberger, pp.271-273

- ^ Google Books. Books.google.com.au. Retrieved 2 September 2012.[better source needed]

- ^ Rasputina and Barham (1977). Rasputin, the man behind the myth, a personal memoir. Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-753129-X.

With the skill of a surgeon, these elegant young members of the nobility castrated Grigori Rasputin, flinging the severed penis across the room.

- ^ "Another America article on Rasputin". Anotheramerica.org. Retrieved 2 September 2012.[dead link][better source needed]

- ^ "Rasputin's Penis: Hoax or not?". Museum of Hoaxes article. Retrieved 2 September 2012.[better source needed]

- ^ Joseph L. Gardner (ed.), "The Unholy Monk", Reader's Digest Great Mysteries of the Past, 1991, p. 161.[better source needed]

- ^ Radzinsky and Rosengrant (2000). The Rasputin File. Nan Talese. p. 13. ISBN 0-385-48909-9.

- ^ How Britain's first spy chief ordered Rasputin's murder (in a way that would make every man wince), by Annabel Venning, Daily Mail, 22 July 2010

- ^ Matrena Rasputina, Memoirs of The Daughter, Moscow 2001. ISBN 5-8159-0180-6 Template:Ru icon

References

- Fuhrmann, Joseph T (1990). Rasputin: A Life (illustrated ed.). New York: Praeger. p. 276. ISBN 0-275-93215-X. OCLC 19269485.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laysummary=and|laydate=(help)

- Massie, Robert K (2004) [originally in New York : Atheneum Books, 1967]. Nicholas and Alexandra: An Intimate Account of the Last of the Romanovs and the Fall of Imperial Russia (Common Reader Classic Bestseller ed.). United States: Tess Press. p. 672. ISBN 1-57912-433-X. OCLC 62357914.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=and|laysummary=(help)

- Radzinsky, Edvard (2000) [originally in London : Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2000]. Rasputin: The Last Word. translator Judson Rosengrant. St Leonards, New South Wales, Australia: Allen & Unwin. p. 704. ISBN 1-86508-529-4. OCLC 155418190.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|laysummary=, and|trans_title=(help)[unreliable source?]

Further reading

- King, Greg (1998) [Originally by Carol Pub. in 1995]. The Man Who Killed Rasputin: Prince Felix Youssoupov and the Murder That Helped Bring Down the Russian Empire (illustrated ed.). Secaucus, New Jersey: Citadel Press. ISBN 0-8065-1971-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=,|laysummary=, and|laydate=(help)

External links

- Okhrana Surveillance Report on Rasputin - from the Soviet Krasnyi Arkiv