The removal of James Heilman (Doc James) from the Wikimedia Foundation Board of Trustees has brought the issue of the “knowledge engine”, i.e. the work of the WMF’s "Discovery" department, into focus for the volunteer community.

Ever since his dismissal, Heilman has maintained that disagreements about appropriate transparency related to the Discovery, or "Knowledge Engine", project, funded by a restricted grant from the Knight Foundation, were a key factor in the events that led to his removal. Jimmy Wales has referred to these claims as "utter fucking bullshit".

But what is "discovery" and the knowledge engine all about? This is an attempt to make sense of the patchy information that the Wikimedia Foundation has provided to the volunteer community and the public to date, and to extract some of the underlying ideas related to the project.

A statement of regret

A few days ago, Lila Tretikov posted a statement titled "Some background on the Knowledge Engine grant" on her talk page on Meta-Wiki. This is worth reading in full; parts of it are excerpted in what follows below. She begins by acknowledging that she should have communicated with the volunteer community sooner.

| “ | Why didn't you discuss these ideas with the community sooner?

It was my mistake to not initiate this ideation on-wiki. Quite honestly, I really wish I could start this discussion over in a more collaborative way, knowing what I know today. Of course, that's retrospecting with a firmer understanding of what the ideas are, and what is worthy of actually discussing. In the staff June metrics meeting in 2015, the ideation was beginning to form in my mind from what I was learning through various conversations with staff. I had begun visualizing open knowledge existing in the shape of a universe. I saw the Wikimedia movement as the most motivated and sincere group of beings, united in their mission to build a rocket to explore Universal Free Knowledge. The words "search" and "discovery" and "knowledge" swam around in my mind with some rocket to navigate it. However, "rocket" didn't seem to work, but in my mind, the rocket was really just an engine, or a portal, a TARDIS, that transports people on their journey through Universal Free Knowledge. From the perspective I had in June, however, I was unprepared for the impact uttering the words "Knowledge Engine" would have. Can we all just take a moment and mercifully admit: it's a catchy name. Perhaps not a great one or entirely appropriate in our context (hence we don't use it any more). I was motivated. I didn't yet know exactly what we needed to build, or how we would end up building it. I could've really used your insight and guidance to help shape the ideas, and model the improvements, and test and verify the impacts. However, I was too afraid of engaging the community early on. Why do you think that was? I have a few thoughts, and would like to share them with you separately, as a wider topic. Either way, this was a mistake I have learned enormously from. |

” |

This kind of communication is potentially a good start to mend fences with the community, and redress some of the things that went wrong with how and when this project was started and communicated.

When did this project start?

In her statement, Lila Tretikov recalls her thoughts around the knowledge engine in June 2015. But to locate the actual beginning of this project, we have to look back a little further than that.

"Search & Discovery" first appeared as a department on the Wikimedia Foundation Staff & Contractors template on 30 April 2015. There would have been no point in creating a well-staffed, well-funded Search & Discovery department in April 2015 if the WMF leadership had had no practical idea of what this team was going to be working on.

Risker was perhaps the first to raise public questions about the project, which remained unanswered. Reviewing the WMF's draft 2015–2016 Annual Plan in her capacity as a member of the volunteer-staffed Funds Dissemination Committee in May 2015, she said on Meta:

| “ | Search and Discovery, a new team, seems to be extraordinarily well-staffed with a disproportionate number of engineers at the same time as other areas seem to be wanting for them. I don't see "fix search" in the Call to Action document; even if it fell into the heading "Improve technology and execution", this seems like an abnormally large concentration of the top WMF Engineering minds to be focusing on a topic that didn't even rate its own mention in the CtA. More explanation of why Search and Discovery has suddenly become such a major focus is required to assess whether this is appropriate resourcing. | ” |

This is in line with what James Heilman said in his Signpost op-ed dated January 13, 2016, describing the ideas around Search & Discovery as having been developed before the April to June 2015 quarter:

| “ | Our long-term strategy must be developed in genuine collaboration with our movement. This means that strategy discussions are started early, that ideas are proposed, and that this is done before a year into a project or millions of dollars are spent. Our ideas around "search and discovery" were developed before April to June of 2015 and we presented them first to potential funders rather than our own communities. | ” |

By September 2015 – more than four months before the WMF publicly announced the grant to the community and the world at large on January 6, 2016 – the Knight Foundation had clearly made a decision to support a WMF knowledge engine project. A still extant page on the Knight Foundation website mentions a grant for $250,000, with a grant period running from 1 September 2015 to 31 August 2016, funding work –

| “ | To advance new models for finding information by supporting stage one development of the Knowledge Engine by Wikipedia, a system for discovering reliable and trustworthy public information on the Internet. | ” |

James Heilman's dating of the project matches the facts. And Risker's questions, posed in May 2015, indicate that the volunteer community – including the FDC – had been out of the loop well before June 2015.

Has the Foundation's grant transparency policy changed?

Lila Tretikov addresses another question in her statement:

| “ | Why did the board not publish this grant paperwork?

Generally we do not post donor documents without advance agreement, because doing so breaks donor privacy required in maintaining sustainable donor relations. In practice, I am told we have not actually published grant paperwork since 2010, but we do publicize grants in blogs when requested and agreed to by donors. A portion of the KF knowledge engine grant document that outlines the actual commitments we've made I quoted below. |

” |

This seems to differ from her predecessor Sue Gardner's statement of WMF policy in October 2011. In this statement, Gardner said,

| “ | The Wikimedia Foundation has a policy of publishing our grant applications when the grantmaking institution is okay with it. We don't do a lot of grant applications, and of the ones we do, I am guesstimating that two-thirds of the grantmakers have said it's fine with them for us to publish, and about a third have asked us not to. Some grantmaking institutions are very happy to publish, because they believe the sector as a whole benefits from transparency about how things work. | ” |

Sue Gardner said publishing grant applications is standard policy unless the donor objects. Lila Tretikov says it is standard policy not to publish grant applications, unless "requested and agreed to by donors."

This seems like a subtle move away from the transparency which the WMF has traditionally emphasised as one of its core values.

"Actions speak volumes"

Volunteers have called for weeks for the Knight Foundation grant application and grant letter to be published. A month ago, for example, MLauba addressed Jimmy Wales on his talk page, responding to statements by Wales that James Heilman's narrative was "misdirection", a "trap", "not true" and that he – Wales – was "a much stronger advocate of transparency than James":

| “ | As for your claim to be a bigger champion for transparency, please back it up with the details on the restricted grant from the Knight foundation immediately. Talk is cheap, actions speak volumes. MLauba (Talk) 18:02, 8 January 2016 (UTC) | ” |

Wales replied,

| “ | What sort of details do you want? I'll have to talk to others to make sure there are no contractual reasons not to do so, but in my opinion the grant letter should be published on meta. The Knight Grant is a red herring here, so it would be best to clear the air around that completely as soon as possible.--Jimbo Wales (talk) 18:19, 8 January 2016 (UTC) | ” |

This sounded promising. Yet nothing happened on that front for the best part of a month, until Lila Tretikov's recent statement on her Meta talk page. In the relatively brief discussion that has ensued there to date, James Heilman has reiterated his call for the grant application to be published:

| “ | What has been requested is the "grant application". This is a document prepared by the WMF and submitted to the Knight Foundation rather than a document from the donor. All other mo[ve]ment entities, including chapters and those applying for individual engagement grants publicly post proposals for funding. I do not understan[d] the reasons the WMF cannot also? Doc James (talk •contribs • email) 16:56, 30 January 2016 (UTC) |

” |

Yet the responses posted by Jimmy Wales and fellow Board member Denny Vrandečić (Denny) on that page are anything but encouraging. The WMF board seems remarkably reluctant to publish both the grant application and the grant letter for community review.

Partial information

What Lila Tretikov has now provided on her Meta talk page is a list of expected outcomes of the Knight Foundation grant, deliverable at the conclusion of the first stage. The mention of a first stage raises the obvious question of how many stages are envisaged, and what the expected deliverables for the other stages are.

Liam Wyatt (Wittylama) mentions in his most recent blog post that the WMF's original grant application seems to have been for a much larger amount than the relatively modest $250,000 the Knight Foundation has actually committed to. As others have pointed out, $250,000 is an amount the Wikimedia Foundation can raise and has raised in a few hours on a December afternoon. Liam Wyatt's assertion that the original application was for a much larger amount seems at least plausible.

Details of the grand vision for this multi-stage project, couched in approachable language understandable by anyone, is still lacking. Publication of the grant application would help volunteers and the public understand the WMF leadership's thinking, and the long-term goals of the Discovery project.

"Are you building a new search engine?"

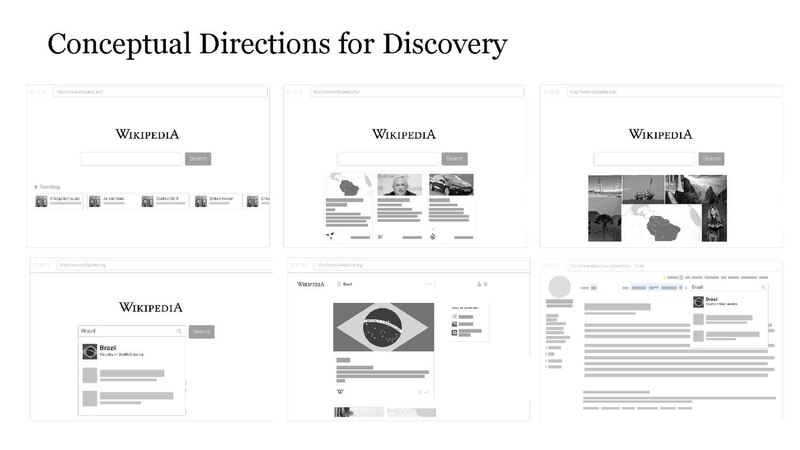

Some related information is available in a Discovery Year 0–1–2 presentation on MediaWiki – but when originally delivered, its slides would have been accompanied by spoken commentary. As it is, the slides are written in such a shorthand and jargon-laden style that it seems likely few general readers will be able to follow the content, and fill in the gaps.

What's described on page 9 of that document however is clearly some form of search engine for open content on the Internet.

This is also reflected in the original Knight Foundation announcement from September 2015:

| “ | To advance new models for finding information by supporting stage one development of the Knowledge Engine by Wikipedia, a system for discovering reliable and trustworthy public information on the Internet. | ” |

Of course, this is not the first time the idea of a search engine has been raised in the Wikimedia universe. Those with long memories will recall Wikia Search, a short-lived free and open-source Web search engine launched by Jimmy Wales' for-profit wiki-hosting company Wikia in 2008.

Wikia Search was conceived as a competitor to the established search engines. It was not a success, closing down in 2009 after failing to attract an audience.

That there have been questions among WMF staff and volunteers whether the WMF is engaged in building a search engine is borne out by a corresponding section in the Discovery FAQ on MediaWiki:

| “ | Are you building a new search engine?

We are not building Google. We are improving the existing CirrusSearch infrastructure with better relevance, multi language, multi projects search and incorporating new data sources for our projects. We want a relevant and consistent experience for users across searches for both wikipedia.org and our project sites. |

” |

At the same time, the Discovery FAQ on MediaWiki asks,

| “ | Would users go to Wikipedia if it were an open channel beyond an encyclopedia? The Wikimedia movement's vision is to make the sum of all human knowledge freely available to everyone. Wikipedia is our largest and most well-known project, but there are many other projects like Wikimedia Commons and Wikidata that move us towards realising our vision. These projects have millions of users every month! So, yes, if we can make a search system that's good enough and meets the needs of our users, people absolutely would use it. |

” |

It is perhaps significant that Wikipedia is now one of the search engine options for the search box in Firefox, alongside Google, Yahoo!, Bing and others.

Deliverables

Assessing whether users would "go to Wikipedia if it were an open channel beyond an encyclopedia" is also one of the key questions the work funded by the Knight Foundation is expected to answer.

The sections of the Knight Foundation grant documentation that Lila Tretikov has quoted on her Meta talk page read as follows:

| “ | What are the expected outcomes of this grant? (quoted text from the grant) At the conclusion of the first stage, the results will include:

What are the activities this grant supports? (quoted text from the grant)

|

” |

Embedding Wikipedia in OEMs and other carriers

Responding to a question about the mention of Original Equipment Manufacturers in the above grant excerpt, Lila Tretikov has indicated on her talk page in Meta that the WMF is

| “ | working with manufacturers that produce mobile phones to put Wikipedia on them at manufacturing time, before those devices are sold. This is especially helpful to raise awareness in emerging markets where Wikipedia is not well known. | ” |

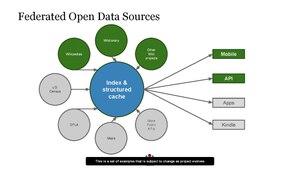

There is no reason to assume that this type of arrangement will be restricted to mobile phones. Even today, the Amazon Kindle e-book reader for example has a Wikipedia look-up function pre-installed, as does the Amazon Echo, a household infotainment assistant that like Apple's Siri responds to voice commands.

One problem the Foundation appears to want to address is that Search often returns "zero results" – i.e. cases where a user query is not mapped to a Wikipedia article.

Kindle users trying to look up a word in a book they're reading will be familiar with this problem. To give an example, the other day I was faced with the term "unentailed" in a Victorian short story. Neither of the Kindle's built-in dictionaries knew the term. Querying Wikipedia on the Kindle yielded the disappointing message: "No Wikipedia results were found for your selection", along with an option to "open Wikipedia". When I did so, I found many Wikipedia articles containing the term, but only one was useful in helping me understand the word: Fee tail.

A better search function might have presented me with that article to begin with. Similarly, I might not have had a zero results message if the Wikipedia search function extended to other Wikimedia projects. Instead, my Kindle might have pointed me to the Wiktionary entry for the word unentailed.

Search improvements like this would make locating information more convenient for Kindle users. Amazon would arguably profit from having a more desirable product.

Machine-generated content

The ongoing community consultation on Meta suggests that one possible approach the Wikimedia Foundation might take would be to

| “ | Explore ways to scale machine-generated, machine-verified and machine-assisted content | ” |

More than half of all language versions of Wikipedia suffer from a long-term dearth or indeed complete lack of human volunteer editors. Wikidata content could be used to have machines generate simple articles "on the fly", using a store of simple sentence templates that Wikidata values are then plugged into. This, too, would reduce the number of times users' searches come up empty.

Public curation of relevance

A key concern for search engines is which information to "surface" in response to a query, i.e. identifying which information is most "relevant" to a user query. (In the above example, for instance, this might have been the Wiktionary entry for the word "unentailed", or the Wikipedia article for "fee tail".)

Here, too, Wikidata and Discovery are apparently envisaged to play a key role in future. A little-visited Discovery RfC draft subpage on MediaWiki speaks of "public curation of relevance":

| “ | We'd like to explore a relevance model where Wikidata could be used as a component of our relevance calculations. This would not only leverage the high quality data in Wikidata but could empower our communities to affect relevance calculations rather than letting algorithms do all the work. As with any system that allows user contributions we would have to be very sensitive and cognizant of anyone gaming the system. | ” |

There are obvious alarm bells attached to that last caveat. Increasing or diminishing the visibility of information to search engine users is what search engine optimisation is all about. Public curation of relevance provides a mechanism that seems tailor-made for that purpose – hence the caveat.

Focus on open content

As discussed in a previous Signpost op-ed, search engines are increasingly re-publishing open content deemed relevant to users' queries on their own sites.

The purpose of a search engine used to be to provide the user with a directory of relevant links. This purpose has shifted: search engines are morphing into answer engines that aim to provide the answers to users' questions directly, obviating users' need to click through to any other site. This supports the search engines' business model: search engines derive a significant part of their income from the ads displayed on search engine results pages. Making sure that users stay on these pages and do not click through to other sites (including Wikipedia) improves the search engines' bottom line.

APIs

The Knight FAQ on MediaWiki emphasises the importance of APIs (application programming interfaces):

| “ | It's important that apps and third parties can search our site too. | ” |

The availability of a Wikipedia knowledge engine would not just benefit users of Wikimedia sites. There are clear overlaps with commercial search engines. Google itself for example, when introducing the Knowledge Graph to the public, referred to it as a "knowledge engine". As mentioned in that publicity video, a key concern when deciding what content to show in response to a query is what other users have judged relevant to their query.

Seen from the viewpoint of potential re-users like Google, Bing, Yandex and other search engines, public curation of relevance, as mentioned above, could help them identify free information sources that human users are likely to find useful.

Thus the API might deliver volunteer-derived data that those answer engines can use to optimise their product – for example through optimised page ranking for open content pages, or direct inclusion of user-preferred free content in answer boxes, knowledge panels and the like.

Coexistence?

Given the information presently available, it seems reasonable to assume that the long-term goal of the Discovery project, including public curation of relevance, is to build a search engine for free information sources on the Internet, and for capturing and defining patterns of human user interaction with such content.

The failed Wikia Search project was designed to compete against Google. Not least because of this failure, it seems unlikely to me that the present Discovery project pursues similar long-term ambitions.

It simply doesn't seem very plausible that the Discovery project could or could even be intended to compete against the likes of Google, Bing and Yandex, given that –

- Wikipedia's open-source nature and APIs would make whatever insights and data the Discovery project generates available to these competitors, who are already well established. Any competitive advantage these data might deliver to a WMF search engine would be instantly neutralised by the fact that its putative competitors would have access to them too.

- Google, Microsoft and Yandex are actually supporting Wikidata. It seems unlikely that they would be funding a competitor.

- Wikidata comes with a no-attribution CC-0 licence, which serves re-users' interests, but undermines the publicly professed rationale of reaching users so as to convert them into editors.

At most, the Wikimedia Foundation board appears to entertain the idea of charging re-users for API use. In other words, the work done by volunteers might be of sufficient economic value to re-users to open up another source of income for the Foundation.

The times, they are a-changing

I recall listening to Lila Tretikov's "Facing the Now" speech at Wikimania 2014, in which she stressed that Wikipedia, while apparently at the peak of its success at the time, was in danger of being left behind by technology developments, and would need to adapt to remain relevant. I wondered at the time what she was driving at, but it seems to become clearer now.

As people's infotainment needs and usage patterns move away from desktop computers to mobile phones, voice-controlled electronic assistants and other products that will be as commonplace in ten or twenty years' time as they are unimagined by most of us today, many of the people who used to visit Wikipedia pages may find their information needs more conveniently satisfied elsewhere than on the pages of an encyclopedia.

The march of technological progress can't be halted. And indeed, many of us find that progress inherently exciting. The idea of positioning the Wikimedia community as the central engine driving many different types of information products and services – or at least a major component of such an engine – is likely to appeal to many Wikimedians. It would certainly keep Wikimedia relevant.

And one might ask, in the absence of scalable alternatives, is there really a better process for generating and curating such content today? Google has long argued that volunteers outperform paid contributors when it comes to such work.

Yet there is also much to be disturbed about. Omnipresent snippets, delivered to a potential audience of billions, amplify the risk of manipulation, creating an information infrastructure that seems more vulnerable to activist influence, or indeed Gleichschaltung, than conventional media. It has been established that even today, search engines would have the power to sway elections if they put their mind to it.

To the extent that volunteer labour helps corporations like Apple, Google, Amazon, and Microsoft make billion-dollar profits, the potential labour patterns described here involve obvious and profound social and economic injustices. On Jimmy Wales' talk page, volunteers have begun to wonder whether they need to unionise to have any influence on the future of their movement.

The increasing importance of machine-generated and machine-read content in efforts to serve global information demand may be anathema to many Wikimedians committed to the idea of an encyclopedia written by people, for people.

And there are other concerns: to what extent do Silicon Valley-facing developments like those described here, efforts to build a technologically slicker product and achieve greater market penetration, detract from other efforts that volunteers might consider more relevant to the core goal of writing an encyclopedia? Making Kindle search functions more easy and satisfying to use is all well and good, but what should the relative priority of such efforts be?

James Heilman is a Wikipedian who has gained much acclaim for his efforts to make Wikipedia's medical content truly reliable. Bringing a Wikipedia article to a quality level that was good enough to make it eligible for inclusion in a peer-reviewed journal (see previous Signpost coverage) – the first Wikipedia article to qualify as a reliable source under Wikipedia's own rules – was a milestone in Wikipedia history, though one the Foundation made no great effort to publicise at the time.

In an alternative universe, the Wikimedia Foundation might put equal focus on supporting and expanding such efforts, believing that a quality product will always have a readership. Ubiquity is not the same as quality; Gresham's law could easily be applied to the world of information as well.

Conclusion

As stated above, this op-ed is my attempt to make sense of the patchy information that has been made public about Discovery, or the Knowledge Engine. I will be grateful to have my interpretations and conclusions confirmed or corrected as appropriate by WMF personnel – and, I am sure, so will the volunteer community.

But most importantly, there are matters here that the community should make an input to. The ongoing community consultation on strategy touches on many of the issues discussed here. It will close on February 15, 2016.

There is also an ongoing issue of transparency. The WMF board should make the Knight Foundation grant application and grant letter public, in line with WMF policy as stated by Sue Gardner in the past. If for some reason the Knight Foundation objects, that should be openly stated and an explanation provided.

- Information sources on Discovery

- meta:User_talk:LilaTretikov_(WMF)

- mw:Wikimedia Discovery/FAQ

- mw:Wikimedia Discovery/Knight FAQ

- mw:Wikimedia_Discovery/RFC

- commons:File:Discovery_Year_0-1-2.pdf

For another perspective on these developments, see Liam Wyatt's blog post Strategy and controversy, part 2.

Update: The grant agreement has since been published, and some further documents have been leaked to the Signpost. See Signpost coverage.

Andreas Kolbe has been a Wikipedia contributor since 2006. He is a member of the Signpost's editorial board. The views expressed in this editorial are his alone and do not reflect any official opinions of this publication. Responses and critical commentary are invited in the comments section.

Discuss this story

Comments

I'm a brand new contributor, as in, I have just created this account today. I can tell you guys for a fact that the reason I have not contributed thus far is because I don't agree or enjoy the fact that all this information is being collected from me. I know it's something that's agreed to upon choosing to use the site. I am one of the few determined dorks that still reads the entire pricy policy and EULA for all the products that I use. (although, you ought to really make those a little bit easier to understand, no one appreciates purposeful lawyer jargon) I'm aware of what's happening, (at least now I am) It's still a bit uncomfortable to take in. Here's the thing, at first I don't know if it was my imagination or what, but it felt like these articles changed so rapidly, or the content was so efficiently user data generated, the site had a mind of it's own. If I come on a site to do research and to learn something new, I want to do just that. I personally want to put the work into it. I don't what the site itself trying to over convenience my search because then I might miss out on stumbling upon something else that's extra fascinating. When I do come on to wikipedia, I no longer use is as a source of reference because it is inherently distracting I can't even stay on the same topic for more than 5 minutes without it demonstrating 6 degrees of separation in terms of content. I use it to keep myself occupied, but I don't use it as a stable trusted resource. I think it's getting out of hand. What's even crazier to me is how finely pinpointed data driven ads have become now too not just in the realm of wikipedia. I swear on my life, when data triggered capabilities were becoming newly implemented, I thought someone was playing a cruel joke on me my phone would be so creepily specific. I was sure when of my more intelligent friends was getting the better half of me. Either that, or my phone computer and other devices had suddenly become sentient. All of these new ideas seem backed by the nobel cause never ending pursuit of knowledge. I'm completely for that! But knowledge doesn't come from my computer or tablet. It doesn't come from what I click on my tablet, or what I've been recorded saying or doing. Sure, you can breach my privacy and learn 'stuff' about me. But stuff and knowledge isn't the same guys. Computers will always lack the most wonderful parts of the living, human, cognitive process. Tech will always lack the flaws, the creativity, the vulnerability, the emotion. It just simply doesn't translate right and never will, we're meant to learn form each other. The internet was absolute wonderful for bringing us closer than ever as a global society, but when you let the machines do all of the work, they just butt in and further the widen.

What DID inspire me to contribute to the post today specifically, was the (only slightly) larger presence of clear concise information you all have presented about your ideas, where the sites going, etc. I've probably found a couple dozen other open dialogs around here that are similar, but everyone sure likes to tiptoe around the issue. I, like many others, truly appreciate honesty and transparency. I think that even though this can be a tough and scary conversation, that people will form their negative or positive opinions regardless once they finally figure it out. And I feel that you're a big enough enough company that you'll do what you want anyway. Theres no reason to hide or dodge it. It's more respectful to engage your users and allow them to more easily know your ambitions and intentions as a company. If people are anything like me, they'll dig and find out what they need to know anyway.

I just have one more thing to say, although my response today may have come off a bit hypercritical, I want to say don't think the sites ambitions are a bad thing. I think that your actions are justified. I still don't necessarily agree with the concept personally, but I still always like maintain an open mind. I would love to hear some more from you guys! How does the grant work, anyhow? I would really love some more information on that too. I apologize for the length, I had so much to say. Hopefully this at least gives you some valuable insight.

W00ptangs (talk) 16:04, 10 February 2016 (UTC)[reply]

What we could do with search and discovery

One of the causes of tension between the WMF and the community is that instead of investing in the IT changes we think we want the WMF invests in software that they think we want. Hence the despair of anyone like myself who has tried to make suggestions through phabricator and bugzilla. There are a bunch of search related software investments that I think the community would welcome:

If the Knowledge Engine is merely a concept in search of some concrete suggestions then I'd like to offer those four as a starter for things that search and discovery could do. If however there are some concrete but not yet disclosed suggestions as to what the Knowledge engine will mean then the sooner they are revealed the less additional anger in the community. ϢereSpielChequers 16:32, 10 February 2016 (UTC)[reply]

Jimbo Wales should clean up his language

I hope that was just a conversation which was intended to be private (but nothing on Wikipedia really is) and not an official statement.— Vchimpanzee • talk • contributions • 20:56, 10 February 2016 (UTC)[reply]

Grant Paperwork

Grant paperwork is only relevant if this is a WMF initiated project. To me it sounds like it is an externally initiated project, which can only be realized in a WMF context. I surmise therefore that some external entities has approached the WMF with this project and the money to pay for it. In which case grant paperwork is not relevant. Jan Pedersen (talk) 14:27, 11 February 2016 (UTC)[reply]

The grant agreement has now been published

See https://wikimediafoundation.org/w/index.php?title=File:Knowledge_engine_grant_agreement.pdf

Mailing list announcement: [2] --Andreas JN466 21:02, 11 February 2016 (UTC)[reply]