This timeline of events related to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) includes events related to the discovery, development, manufacture, marketing, uses, concerns, litigation, regulation, and legislation, involving the human-made PFASs. The timeline focuses on some perfluorinated compounds, particularly perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS)[1] and on the companies that manufactured and marketed them, mainly DuPont and 3M.[2] An example of PFAS is the fluorinated polymer polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), which has been produced and marketed by DuPont under its trademark Teflon. GenX chemicals and perfluorobutanesulfonic acid (PFBS) are organofluorine chemicals used as a replacement for PFOA and PFOS.[3]

PFAS compounds and their derivatives are widely used in many products from water resistant textiles to fire-fighting foam.[4][1] PFAS are commonly found in every American household in products as diverse as non-stick cookware, stain resistant furniture and carpets, wrinkle free and water repellant clothing, cosmetics, lubricants, paint, pizza boxes, popcorn bags and many other everyday products.[5]

Timeline[edit]

19th century[edit]

- 1802 Éleuthère Irénée du Pont, who had emigrated from France after the French Revolution, founded a company to produce gunpowder called E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company (commonly referred to as DuPont) in Brandywine Creek, near Wilmington, Delaware.[6]

20th century[edit]

- 1902 John Dwan, Hermon Cable, Henry Bryan, and William A. McGonagle co-founded Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company (3M) in Two Harbors, Minnesota in 1902 as a corundum mining operation.[7] The men did not know at that time that "corundum was really another low-grade mineral called anorthosite."[8]

- 1930 General Motors and DuPont formed Kinetic Chemicals to produce Freon.

- 1935 On 22 January, E. I. du Pont de Nemours & Co., Inc., formally opened the Haskell Laboratory of Industrial Toxicology on the grounds of the Experimental Station of the company.[9] It was at that time, "one of the first in-house toxicology facilities." It was established on the advice of a DuPont in-house doctor named George Gehrmann.[10][11]: 278–288 According to a 1935 news item in the Industrial and Engineering Chemistry journal, the purpose of the du Pont facility was to thoroughly test all du Pont products as a public health measure to determine the effects of du Pont's finished products on the "health of the ultimate consumer " and that the products "are safe" "before they are placed on the market". The Haskell Laboratory facilities were "not to be employed in the development of compounds useful in therapeutics.". W. F. von Oettingen was the first director of Haskell Laboratory of Industrial Toxicology.[9] The laboratory was named after Harry G. Haskell, du Pont's vice president,[12]

- 6 April 1938 Roy J. Plunkett (1910–1994), who was then a 27-year-old research chemist who worked at the DuPont's Jackson Laboratory in Deepwater, New Jersey,[13] was working with gases related to DuPont's Freon refrigerants, when an experiment he was conducting produced an unexpected new product.[14]—tetrafluoroethylene resin. He had accidentally invented polytetrafluorethylene (PTFE), a saturated fluorocarbon polymer—the "first compound in the family of Perfluorinated compounds (PFCs), "to be marketed commercially."(Lyons 2007)[15] It took ten years of research before polytetrafluorethylene (PTFE) was introduced under its trade name Teflon, where it became known for being "extremely heat-tolerant and stick-resistant."[16] In 1985, Plunkett was named to the National Inventors' Hall of Fame for the invention of Teflon, which "has been of great personal benefit to people—not just indirectly, but directly to real people whom I know."[14] Plunkett described the discovery and development at the 1986 American Chemical Society symposium on the History of High Performance Polymers.[17]: 261–266 He said that he and his assistant, Jack Rebok, had opened a tetrafluoroethylene (TFE) cylinder to examine an unusual white powder that had prevented the TFE gas from flowing out. Upon opening the cylinder, they found that the white powder was "packed onto the bottom and lower sides of the cylinder." The sample of gaseous TFE in the cylinder had polymerized spontaneously into a white, waxy solid. The polymer was polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE). In 1945, DuPont commercialized PTFE as Teflon. They found that PTFE was resistant to corrosion, had low surface friction, and high heat resistance.[17] Tetrafluorethylene (TFE) can cyclize with a wide variety of compounds which led to the creation of a range of organofluorine compounds.

- 1950s For decades—beginning in the 1950s—3M manufactured PFAS at its plant in Cottage Grove in Washington County, Minnesota. 3M, with 10,000 employees in Maplewood in Ramsey County where it is headquartered—is the largest employer in Maplewood.[18]

- 1950s According to the 2016 lawsuit brought against 3M by Lake Elmo, Minnesota, 3M had "disposed of PFCs and PFC-containing waste at a facility it owned and operated in Oakdale, Minnesota (the "Oakdale Facilities")" during the 1950s.[18][19]

- 1951 "The DuPont chemical plant in Washington, West Virginia, began using PFOA in its manufacturing process."[20]

- 1954 R. A. Dickison, who was employed at DuPont, received an inquiry about C8's "possible toxicity."[10]

- 1955 A study undertaken by Gordon I. Nordby and J. Murray Luck at Stanford University found that "PFAS binds to proteins in human blood."[21]

- 1960s DuPont "buried about 200 drums of C8 on the banks of the Ohio River near the plant."[10]

- 1963 The United States Navy scientists began to work with 3M to develop aqueous film-forming foams (AFFF). The US military began to use AFFF since its development in 1963 and patented AFFF in 1967.[22][23]

- 1961 A DuPont in-house toxicologist said C8 was toxic and should be "handled with extreme care."[10]

- 1962 3M moved its headquarters from Saint Paul, Minnesota—where it had been located since 1910, to its headquarters at 3M Center in Maplewood, Minnesota.[24]

- 1965 John Zapp, who was then director of DuPont's Haskell Laboratories, "received a memo describing preliminary studies that showed that even low doses of a related surfactant could increase the size of rats' livers, a classic response to exposure to a poison."[10]

- 1967 In the wake of the 1967 USS Forrestal fire, which happened off the coast of north Vietnam—"one of the worst disasters in U.S. naval history"—in which 134 people were killed and the U.S. Navy aircraft carrier was almost destroyed, the US Navy began to make it mandatory for its vessels to carry Aqueous Film Forming Foams (AFFF) on board.[23] A rocket, that was accidentally launched by a power surge, caused a fire that burned all night when it hit a "fuel tank, igniting leaking fuel and causing nine bombs to explode."[23][25]

- October 1969 In a laboratory that he shared with his father, Bill Gore, while experimenting with ways of "stretching extruded PTFE into pipe-thread tape", and after "series of unsuccessful experiments", Robert (Bob) Gore (1937–2020), accidentally discovered that a "sudden, accelerated yank" caused the PTFE to "stretch about 800%, which resulted in the transformation of solid PTFE into a microporous structure that was about 70% air."[26] At the time Bob Gore was working with W. L. Gore and Associates, a company established by his father Wilbert (Bill) Gore (1912–1986), who had worked at Remington Arms DuPont plant in Ilion, New York, during World War II as a chemical engineer.[26]

- early 1970s According to court documents in the lawsuit against 3M, the company had "disposed of PFCs and PFC-containing waste at the city of Lake Elmo's Washington County Landfill".[19]

- 1970s The Quartz said that according to a document on file with the US Environmental Protection Agency and discovered by The Intercept's Sharon Lerner in June 2019, reported that the document was on file with the US Environmental Protection Agency, that Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company (3M) "knew as early as the 1970s that PFAS was accumulating in human blood." 3M's own experiments on rats and monkeys concluded that PFAS compounds "should be regarded as toxic."[27]

- 1970s In the 1970s researchers at 3M documented the presence of PFOS and PFOA—the "two best-known PFAS compounds"—in fish.[28]

- 1970s In Australia, firefighting foams containing PFAS had been used "extensively" since the 1970s, because they were very effective in "fighting liquid fuel fires."[29]

- 1978 3M scientists, Hugh J. Van Noordwyk and Michael A. Santoro published an article on 3M's hazardous waste program in the Environmental Health Perspectives (EHP) journal,[30] which is supported by the United States Department of Health and Human Services's (DHHS) National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), an institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The authors said that 3M considered "thermal destruction of hazardous wastes" as the "best method for their disposal".[30] By 1978, 3M had built seven incineration facilities throughout the United States on "3M manufacturing plant sites at Brownwood, Texas, Cordova, Illinois, Cottage Grove, Minnesota, Decatur, Alabama, Hartford City, Indiana, Nevada, Missouri, and White City, Oregon."[30]: 247

- 1983 Following approval by the Federal Environmental Protection Agency and the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency in July, 3M, described by The New York Times as a "diversified manufacturing concern" announced their $6 million cleanup of what would become known as the Oakdale Dump.[31] The Times said that it was the "second major clean of a hazardous waste area in Minnesota to be financed entirely by a private company." The three dumps, that had been abandoned by 3M, had "contaminated ground water and soil with hazardous chemical wastes", according to environmental officials.[31]

- 1998 Cincinnati, Ohio-based Robert Bilott, an American environmental attorney with Taft Stettinius & Hollister, took a case representing Wilbur Tennant, a Parkersburg, West Virginia, farmer, whose herd of cattle had been decimated by strange symptoms that Tennant blamed on DuPont's Washington Works facilities.[32]

- 1998 The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) "was first alerted to the risks" of PFAS—human-made "forever chemicals" that "never break down once released and they build up in our bodies".[33] The EPA's Stephen Johnson, said in Barboza's 18 May 2000 Times article that The EPA first talked to 3M in 1998 after they were first alerted to 3M's 1998 laboratory rat study in which "male and female rats were given doses of the chemical and then mated. When a pregnant rat continued to get regular doses of about 3.2 milligrams per kilogram of body weight, most of the offspring died within four days." According to Johnson, "With all that information, [the EPA] finally talked to 3M and said that raises a number of concerns. What are you going to do?"[34]

- Summer of 1999 Bilott filed a federal suit in the Southern District of West Virginia on behalf of Wilbur Tennant against DuPont.[32] A report commissioned by the EPA and DuPont and authored by 6 veterinarians—3 chosen by the EPA and the others by DuPont—found that Tennant's cattle had died because of Tennant's "poor husbandry", which included "poor nutrition, inadequate veterinary care and lack of fly control." The report said that DuPont was not responsible for the cattle's health problems.[32]

21st century[edit]

2000s[edit]

- 17 May 2000 3M stopped manufacturing "PFOS (perfluorooctanesulphonate)-based flurosurfactants using the electrochemical flouorination process."[35] Prior to 2000, the "most common PFCs" used in AFFFs were "PFOS and its derivatives."[35] According to Robert Avsec, who was Fire Chief of the Chesterfield, Virginia, Fire and EMS Department for 26 years, in fires classified as Class B—which includes fires that are difficult to extinguish, such as "fires that involve petroleum or other flammable liquids"—firefighters use a classification of firefighting foam called Aqueous Film Forming Foams (AFFF) foams.[35] Concerns have been raised about PFCs contaminating groundwater sources.[35]

- 17 May 2000 Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist,[36] David Barboza reported that 3M had voluntarily agreed to stop manufacturing Scotchgard because of their "corporate responsibility" to be "environmentally friendly". Their own tests had proven that PFOS, an agent that 3M used in the fabrication of Scotchgard—was proven to linger in the environment and in humans. Barboza said that 3M's "decision to drop Scotchgard" would likely affect DuPont's use of PFOAs in the manufacturing of Teflon.[37]

- 18 May 2000 Barboza corrected his 17 May 2000 report saying that 3M had not acted voluntarily to be environmentally friendly as they had claimed. EPA officials said that while, "it did not see an immediate safety risk for consumers using products now on the market...if 3M had not acted they would have taken steps to remove the product from the market."[34] EPA had become "concerned about potential long-term health risks to humans after a 3M study showed that the chemical, perfluorooctanyl sulfonate (PFOS), lingered for years in human blood and animal tissue and that high doses were known to kill laboratory rats."[34]

- August 2000 In his research in preparation for the court case, Bilott found an article mentioning the "little-known substance"—a surfactant— called perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) or C8—had been found in DuPont's Dry Run Creek, adjacent to Tennant farm, and Bilott requested "more information on the chemical". This concerned DuPont's lawyer, Bernard J. Reilly, who raised concerns at DuPont's Delaware headquarters.[38]

- Fall of 2000 A court order that Bilott had requested, forced DuPont to submit 110,000 pages of documents dated back to the 1950s of DuPont's "private internal correspondence, medical and health reports and confidential studies conducted by DuPont scientists".[32]

- 2001 DuPont settled the lawsuit filed by Bilott on behalf of Tennant for an undisclosed sum.[39][40]

- 2001 The Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) sampled surface waters from 21 streams across the state for PFAS after elevated levels were found in water, fish, and wildlife in Minnesota and other areas. However, the results ranging between 1 and 24 parts per trillion (ppt) were not considered a concern based on information available at the time.[41][42]

- March 2001 After spending months poring through the DuPont's documents, attorney Bilott sent a 972-page submission to directors of all relevant regulatory authorities, including the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) director Christie Whitman, and the US AG, John Ashcroft, demanding "immediate action be taken to regulate PFOA and provide clean water to those living near" DuPont's Washington Works facilities.[32]

- April 2001 In a highly cited article in the Environmental Science & Technology, published by the American Chemical Society, John Giesy and Kurunthachalam Kannan reported "for the first time, on the global distribution of perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS), a fluorinated organic contaminant." Based on the findings of their 2000 study, Giesy and Kannan said that "PFOS were widely detected in wildlife throughout the world" and that "PFOS is widespread in the environment." They said that "PFOS can bioaccumulate to higher trophic levels of the food chain" and that the "concentrations of PFOS in wildlife are less than those required to cause adverse effects in laboratory animals."[4][43]

"PFOS was measured in the tissues of wildlife, including, fish, birds, and marine mammals. Some of the species studied include bald eagles, polar bears, albatrosses, and various species of seals. Samples were collected from urbanized areas in North America, especially the Great Lakes region and coastal marine areas and rivers, and Europe. Samples were also collected from a number of more remote, less urbanized locations such as the Arctic and the North Pacific Oceans. ... Concentrations of PFOS in animals from relatively more populated and industrialized regions, such as the North American Great Lakes, Baltic Sea, and Mediterranean Sea, were greater than those in animals from remote marine locations. Fish-eating, predatory animals such as mink and bald eagles contained concentrations of PFOS that were greater than the concentrations in their diets."

— John P. Giesy and Kurunthachalam Kannan. 2001. - June 2001 According to a June 2007 article in the Industrial Fire Journal (IFJ), the Firefighting Foam Coalition (FFC) was created by "[m]anufacturers of firefighting foams and the fluorosurfactants they contain" as a "focal point" for co-operation with "several environmental authorities" regarding "potential environmental impacts of its products."[44]: 75 The article said that there has been a heightened awareness on the part of the "fire protection industry" on its environmental impact as concerns were raised about ozone depletion in the late 1980s.[44]: 75

- 31 August 2001 A state court action was filed in West Virginia by Bilott, Harry Deitzler, an attorney with Hill, Peterson, Carper, Bee and Deitzler, and others on behalf of thirteen individuals in the "Leach Case"—Jack W. Leach, William Parrish, Joseph K. Kiger, Darlene G. Kiger, Judy See, Rick See, Jack L. Cottrell, Virginia L. Cottrell, Carrie K. Allman, Roger D. Allman, Sandy Cowan, Aaron B. McConnell, and Angela D. McConnell—DuPont.[45][32] Tennant had settled his lawsuit privately with DuPont. In their "Amended class action complaint" attorneys for the plaintiffs, said that in October and November 2000 and July 2001, DuPont had sent notices to Lubeck Public Service District (LPSD) customers, informing them that there was PFOA in the LPSD's water system.[46] In 2000, West Virginia recognized the medical-monitoring claim which allows a plaintiff to "sue retroactively for damages".[32] Bilott filed the class-action suit in August 2001 in the West Virginia state court, "even though four of the six affected water districts lay across the Ohio border."[32]

- 2002 DuPont's Fayetteville, North Carolina facility began to manufacture C8.[47]

- 2002 Since 2002, when the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) first developed "Health Based Values for PFOS and PFOA", the MDH has also developed "health-based guidance values for PFOS, PFOA, PFBS, and PFBA, and uses the PFOS value as a surrogate for evaluating PFHxS (in lieu of sufficient PFHxS-specific toxicological information)."[48] MDH had begun partnering with Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) to investigate PFAS in "drinking water investigations east of Saint Paul near the 3M Cottage Grove plant and related legacy waste disposal sites in Washington County."[48]

- 2002 Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) "Public Health Laboratory developed an analytical method tailored to the PFAS found in the 3M waste disposal sites."[48] They also "developed two other methods with longer analyte lists to evaluate AFFF and other sites."[48] These investigations resulted in the discovery of "groundwater contamination covering over 150 square miles, affecting the drinking water supplies of over 140,000 Minnesotans. Over 2,600 private wells have been sampled and 798 drinking water advisories issued."[48]

- 2002 BIOEX a French manufacturer of firefighting foam, pioneer in environmentally friendly foams, launched in 2002 the first multipurpose fluorine-free foam (ECOPOL) into the market. Their environmental challenge has been to convince their customers to choose their new generation of green products, which are 100% fluorine free, and have proven to be effective.[49]

- 2003 Weinberg Group's then Vice-President of Product Defense, P. Terrence Gaffney wrote a 5-page letter urging DuPont to prepare a defense strategy for future litigation related to the health impacts of PFOAs in Parkersburg, West Virginia. The letter was mentioned in an Environmental Science & Technology article called "The Weinberg proposal" by Paul D. Thacker.[50] Gaffney wrote that, "DuPont must shape the debate at all levels." He offered several strategies which included the establishment of "blue ribbon panels", the coordination of papers on PFOA and on junk science, the "publication of papers and articles dispelling the alleged nexus between PFOA and teratogenicity as well as other claimed harm."[51]

- 2003 Gale D. Pearson, then a local lawyer in Cottage Grove, was one of the first people to look into contaminated ground water in Cottage Grove. In 2003, lawyers had contacted her regarding a personal injury case about contaminated water near a [DuPont/Chemouris] plant in West Virginia where they manufactured Teflon in a process that used PFOAs, a type of PFAS. She knew that 3M had manufactured PFOAs in their Cottage Grove facility.[52] Pearson discovered through the Environmental Working Group (EWS) that PFAS were not just found in Washington County, Minnesota and West Virginia, but all over the world.[52] 3M had dumped waste in the Cottage Grove "when it was still just farmland" and in other nearby farmlands in Washington County.[52] Pearson and her team hired a chemist to test soil and water samples on the properties where 3M had dumped the chemicals.[52] Blood samples from the local population in the affected area were also tested for PFAS. Pearson said that the laboratory tests revealed that there was a "hotspot of contamination in the blood of the community."[52]

- 19 June 2003 Ted Schaefer, a chemist who worked for 3M in Australia patented a firefighting foam that did not contain PFOS or any other persistent ingredients. Immediately after 3M chose to no longer manufacture PFOS in 2000, the company deployed Schaefer to develop a replacement for the Aqueous Film Forming Foams (AFFF). By 2002, Shaefer, who had worked for years on "foams used to put out forest fires", developed a fluorine-free foam that was able to put out jet fuel fires within 46 seconds. The International Civil Aviation Organization standard was 60-seconds.[53][23]

- October 2003 A report by Oregon State University's Jennifer Field which was based on "data on fluorosurfactants in groundwater at three military sites where AFFF was used to train fire responders" concluded that the "perfluoroalkyl sulfonates and perfluoroalkyl carboxylates found in the groundwater came from PFOS-based AFFF agents".[44] Field said that "the 6:2 fluorotelomer sulfonate was likely the primary breakdown product of the six-carbon fluorosurfactants contained in fluorotelomer-based AFFF." Field's report was presented at an October 2003 EPA workgroup, which"determined that modern AFFF agents" were "not likely to be a source of PFCAs such as PFHxA and PFOA in the environment. EPA concluded that existing data "provided no evidence that these fluorosurfactants biodegrade into PFOA or its homologs..." according to a 2007 Industrial Fire Journal (IFJ) article.[44]

- 2004 PFCs were detected in the Oakdale facilities and the landfill by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) and it was "revealed that the PFCs had leached from the Oakdale Facilities and the Landfill into the groundwater aquifers serving as Lake Elmo's drinking water supply."[19]

- 2004 According to 2004 report by ChemRisk—an "industry risk assessor" hired by DuPont, Dupont's Parkersburg, West Virginia-based Washington Works plant had "dumped, poured and released" over 1.7 million pounds of C8 or perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) into the environment between 1951 and 2003.[54]

- 23 November 2004 The Circuit Court of Wood County, West Virginia class action lawsuit, Leach, et al v. E. I. DuPont deNemours and Co. against DuPont, on behalf of residents in the Parkersburg regional area—including Little Hocking, Ohio, Lubeck Public Service District, West Virginia, the city of Belpre, Ohio, Tuppers Plains, Ohio, Mason County Public Service District, West Virginia and the village of Pomeroy, Ohio—whose water systems were affected by C-8 water contamination was certified by Judge George W. Hill on 23 November 2004.[55] The settlement in 2004 "established a court-approved scientific panel to determine what types of ailments are likely linked to PFOA exposure."[56] In a 25 November 2019, case in the District court of Ohio, the judge "rejected DuPont's claims that the court had misinterpreted the 2004 class-action settlement, and that the court should have applied Ohio's tort reform act, which caps the amount of some types of damages plaintiffs can receive."[56] The settlement included a requirement that DuPont "pay the costs of medical monitoring for nearly 100,000 people in the area."[57] Over "3,500 residents opted out of the class-action settlement to instead pursue individual lawsuits."[57]

- 2005-2006 The C8 Health Project undertaken by the C8 Science Panel "surveyed 69,030 individuals" who had "lived, worked, or attended school for ≥ 1 year in one of six contaminated water districts near the plant between 1950 and 3 December 2004."[20]

- 2005 According to a 2005 Journal of Vinyl and Additive Technology article that was cited in The Intercept, "PFAS chemicals are used widely to help with the molding and extrusions of plastic".[58][59]

- 2006 The EPA brokered a voluntary agreement with DuPont and eight other major companies to phase out the use of PFOS and PFOA in the United States.[60]

- January 2007 Dennis Paustenbach, who was the founder of ChemRisk, co-authored an article entitled "A methodology for estimating human exposure to perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA): a retrospective exposure assessment of a community (1951-2003)" in the Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, in which the authors said that " The predicted historical lifetime and average daily estimates of PFOA intake by persons who lived within 5 miles of the plant over the past 50 yr were about 10,000-fold less than the intake of the chemical not considered as a health risk by an independent panel of scientists who recently studied PFOA."[61]

- 2009 3M shut down their Saint Paul Plant.[24] In 1910, 3M had moved its headquarters and manufacturing facilities from Duluth to one building on Forest Street in Dayton's Bluff, Saint Paul, one of Saint Paul's oldest communities on the east side of the Mississippi River.[24] Over the years, it expanded into a 61-acre 3M campus.[62] Whirlpool's factory, Hamm's/Stroh's brewery and other industries were also located along East 7th Street, the diagonal-running artery that ran through the Dayton Bluff neighborhood to downtown St. Paul. The three companies shut down in "rapid succession."[62] 3M was the last of the three leaving the community. These companies had provided good-paying jobs in the neighbourhood so their closing left Dayton Bluff as a "boulevard of broken dreams"—a "once-thriving neighborhood descended into a defeating spiral of decay, witnessed by vacant lots, boarded-up storefronts and rising crime."[62] When the St. Paul's development agency, the Port Authority, took over the campus, it was renamed Beacon Bluff.[62]

- September 2009 The U.S. EPA released Method 537, its first for analyzing PFAS.[63]

2010s[edit]

- 2010 Lake Elmo, Minnesota, a city of about 8,000 people in Washington County, Minnesota—sued 3M when PFAS chemicals, known as 'forever chemicals', were found to have contaminated Lake Elmo's drinking water.[18]

- March 2010 The Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) found PFAS contamination at the former Wurtsmith Air Force Base (WAFB) after sampling a former fire training area on the base. Finding a mean concentration of 5,099 ppt of PFOS and 1,309 ppt of PFOA in Clark's Marsh in Oscoda, Michigan nearby WAFB.[64] MDEQ also found PFOS concentrations in fish as high as 9,580,000 ppt, resulting in the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) issuing a "Do Not Eat" advisory for all species of fish in Clark's Marsh and several species in the Au Sable River. MDEQ requested help from state toxicologists to determine the significance of these PFAS levels, which resulted in a statewide sampling plan in 2013 and 2014 to determine the scope of PFAS contamination throughout the state, specifically around WAFB. As a result, several more contamination sites were found, including a nearby McDonald's store fire that was put out with AFFF firefighting foam.[41][65][66]

- March 2014 The EPA's Federal Facilities Restoration and Reuse Office (FFRRO) developed and published a fact sheet which provided a "summary of the emerging contaminants perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), including physical and chemical properties, environmental and health impacts, existing federal and state guidelines, detection and treatment methods.[67][68]

- March 2014 The Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) released PFAS surface water standards, with drinking waterbody values of 420 ppt for PFOA and 11 ppt for PFOS, and non-drinking waterbody values of 12,000 ppt for PFOA and 12 ppt for PFOS.[69]

- 2016 The EPA "published a voluntary health advisory for PFOA and PFOS" which warned that "exposure to the chemicals at levels above 70 parts per trillion, total, could be dangerous."[70]

- 2016 The city of Lake Elmo, Minnesota sued 3M a second time for polluting their drinking water with PFAS chemicals.[18] 3M filed for a dismissal and was refused in 2017.[19]

- 2016 In a 17 October 2016 article by Robert Avsec, Fire Chief of the Chesterfield, Virginia, Fire and EMS Department for 26 years, manufacturers of the firefighting foam had "moved away from PFOS and its derivatives as a result of legislative pressure." They began to develop and market "fluorine-free...firefighting foams"—foams "that do not use fluorochemicals"[35]

- 2017 3M net sales for 2017 were $31.657 billion compared to $30.109 billion in 2016.[71]

- 2017 The Fire Fighting Foam Coalition's 2017 fact sheet said that the short chain (C6) fluorosurfactants which are replacing the longer C8 in AFFF are "low in toxicity and not considered to be bioaccumulative based on current regulatory criteria."[72]

- 2017 PFAS are on the Government of Canada's 2019 chart of substances that are prohibited by Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA) and by Prohibition of Certain Toxic Substances Regulations, 2012. These substances are under these regulations because they are "among the most harmful" and "have been declared toxic to the environment and/or human health", are "generally persistent and bioaccumulative." The "regulations prohibit the manufacture, use, sale, offer for sale or import of the toxic substances listed below, and products containing them, with a limited number of exemptions."[73]

- 5 January 2017 The jury in a case against DuPont, awarded compensation of $10.5 million to the plaintiff in the U.S. District Court in Columbus, with U.S. Chief District Judge Edmund A. Sargus Jr. presiding. The attorney for the plaintiff, Gary J. Douglas urged the jury to award punitive damages that reflected DuPont's assets and income—as revealed by the witness for the plaintiff—Robert Johnson a forensic economist. Johnson said that DuPont has $18.8 billion in assets "that can be converted to cash" and "has net sales of $68 million a day." Johnson said that DuPont makes "$2 million...in 42 minutes."[74]

- 13 February 2017 The 2001 class-action suit that Bilott had filed against DuPont, on behalf of the Parkersburg area residents, resulted in DuPont agreeing to pay $671 million in cash to settle about 3,550 personal injury claims involving a leak of perfluorooctanoic acid—PFOA or C-8— used to make Teflon in its Parkersburg, West Virginia-based Washington Works facilities. DuPont denied any wrongdoing.[45][32][75][76] Chemours shares rose 13 percent and DuPont shares rose 1 percent.[76]

- 22 May 2017 According to a 2 November 2018, Bloomberg article, the Minnesota Health Department (MHD) notified the office of the Mayor of Cottage Grove, Myron Bailey, that the MHD had "set a new, [stricter], lower level for a type of unregulated chemical found in Minnesota's drinking water" and that Cottage Grove's water "would exceed the new threshold" that was necessary to "better protect infants and young children."[77] Bailey called a state of emergency.[52]

- Fall 2017 When abnormally high levels of PFAS were found in Belmont, Michigan, it became one of the first places where PFAS contaminations caught the attention of the media. The contamination was attributed to Wolverine Worldwide, a footwear company that had used Scotchgard to "treat shoe leather" and had dumped their waste in that area decades ago at a landfill operated by the company and at two illegally operated dumps discovered by concerned citizens.[78][79] A residential well tested across the street from Wolverine's landfill had a PFOS level of 38,000 ppt.[79]

- Late 2017 The Australian Government established an Expert Health Panel for PFAS to "advise the Australian Government on the evidence for potential health impacts associated with PFAS exposure and recommend priority areas for future research." Their report was submitted in March 2018.[29]

- 13 November 2017 The state of Michigan creates the Michigan PFAS Action Response Team (MPART), the first multi-agency action team of its kind in the nation. Agencies representing health, environment and other branches of state government have joined to investigate sources and locations of PFAS contamination in the state, take action to protect people's drinking water, and keep the public informed.[80]

- 2018 The Australian National University was commissioned by the Australian Government to conduct a health study to examine patterns of PFAS contamination and potential implications for human health at Defence sites in Australia, with a focus on three sites—Williamtown in New South Wales, Oakey in Queensland and Katherine in the Northern Territory.[29]

- 10 January 2018 According to the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services's Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) website, which was last reviewed on10 January 2018, the "health effects of PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS, and PFNA have been more widely studied than other per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Some, but not all, studies in humans with PFAS exposure have shown that certain PFAS may affect growth, learning, and behavior of infants and older children, lower a woman's chance of getting pregnant, interfere with the body's natural hormones, increase cholesterol levels, affect the immune system, and increase the risk of cancer."[81]

- 10 January 2018 The state of Michigan established an enforceable cleanup standard of 70 ppt for PFOA and PFOS, individually or combined. Concurrently, two science advisory committees were created to "coordinate and review medical and environmental health, PFAS science and develop evidence-based recommendations", these committees are a part of the Michigan PFAS Action Response Team (MPART).[82]

- 30 January 2018 According to an article by the Center for Science and Democracy's director, Michael Halpern and posted by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), in early 2018, Nancy Beck, Deputy Assistant Administrator at the Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention (OCSPP),[83] the Office of Land and Emergency Management (OLEM), Office of Research and Development (ORD)—three branches of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—exchanged chains of emails with Office of Management and Budget (OMB), the United States Department of Defense (DoD), HHS, and the Pentagon,[70] to put pressure on the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) to censor a report that measured the "health effects" of PFAS that are "found in drinking water and household products throughout the United States."[84] Beck wrote to EPA staff including, Jennifer Orme-Zavaleta, Ryan Jackson, and Peter Grevatt, and Mike Flynn (EPA) in regards to "PFAS meeting with ATSDR" that the "implications for susceptible populations came as a surprise to OCSPP staff."[85] Beck is "one of the EPA political appointees with ties to the chemical industry involved in the effort to prevent the study from being released."[84] An email by an unidentified Trump administration aid that was forwarded by Office of Management and Budget's(OMB) James Herz, said that "The public, media, and Congressional reaction to these numbers is going to be huge. The impact to EPA and [the Defense Department] is going to be extremely painful. We (DoD and EPA) cannot seem to get ATSDR to realize the potential public relations nightmare this is going to be." one unidentified White House aide said in an email forwarded on 30 Jan. by James Herz, a political appointee who oversees environmental issues at the OMB. The email added: "The impact to EPA and [the Defense Department] is going to be extremely painful. We (DoD and EPA) cannot seem to get ATSDR to realize the potential public relations nightmare this is going to be."[70]

- 20 February 2018 The state of Minnesota "settled its lawsuit against the 3M Company in return for a settlement of $850 million".[86] Their Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) interactive map indicates the location of dozens of wells under advisory because of contaminated ground water in southern Minnesota where Mississippi River winds past Saint Paul's.[87] After the trial concluded, the Attorney General of Minnesota published some of the documents related to the case, saying that said the public had a right to know as 3M had been aware of health risks for decades.[52]

- Early 2018 Department of Health & Human Services's Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) was about to publish its assessment of PFAS chemicals, with a focus on two specific chemicals from the PFAS class—PFOA and PFOS—that have "contaminated water supplies near military bases, chemical plants and other sites from New York to Michigan to West Virginia" which showed that the PFAS chemicals "endanger human health at a far lower level than EPA has previously called safe."[70] The HHS updated ATSDR study would have warned that exposure to PFOA and PFOS at less than one-sixth of the EPAs current guideline of 70 parts per trillion, "could be dangerous for sensitive populations like infants and breastfeeding mothers."[70]

- March 2018 The United States Department of Defense's (DoD)'s report to Congress said that test that they conducted showed that the amount of PFAS chemicals in water supplies near 126 DoD facilities, "exceeded the current safety guidelines".[70] The DoD has "used foam containing" PFAS chemicals "in exercises at bases across the country". The DoD, therefore, "risks the biggest liabilities" in relation to the use of PFAS chemicals according to Politico.[70]

- March 2018 The PFAS Expert Health Panel on PFAS submitted their commissioned report to the Australian government.[88]

- 14 May 2018 Politico gained access to the email chains and published the story in May, saying that Scott Pruitt's EPA had worked with the Trump administration to block the publication of the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) report.[70]

- 21 June 2018 The Department of Health & Human Services's Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) 697-page draft report for public comment, "Toxicological Profile for Perfluoroalkyls", was finally released.[89][90]

- October 2018 The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) and Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR) issued a 'Do Not Eat' advisory for all white-tailed deer within five miles of Clark's Marsh (near former WAFB). The state tested 128 white-tailed deer across Michigan, 20 deer each from four separate PFAS investigation areas and an additional 48 from other areas submitted by hunters during the 2017 hunting season. One of twenty deer tested near Clark's Marsh was found to have a PFOS level of 547 parts per billion (ppb) taken from a muscle sample. It is unknown how PFAS could accumulate to the level seen in the deer found near Clark's Marsh. All deer except the one with elevated levels at Clark's Marsh were found to have no or very low levels of PFAS chemicals. MDHHS recommended state residents not eat kidneys or livers from any deer as PFAS chemicals can accumulate in these organs.[91]

- 14 November 2018 According to The Guardian, a 14 November 2018 EPA draft assessment said that "animal studies showing effects on the kidneys, liver, immune system and more from GenX,"[60][3] the chemicals manufactured by Chemours—a corporate spin-off of DuPont, in Fayetteville, North Carolina.[92] GenX chemicals are using PFOA (C8) for manufacturing fluoropolymers such as teflon,[93][94] and in products such as firefighting foam, paints, food packaging, outdoor fabrics, and cleaning products.[95]

- 7 December 2018 The Michigan PFAS Science Advisory Panel releases Scientific Evidence and Recommendations for Managing PFAS Contamination in Michigan, which outlines evidence-based recommendations for the state as well as recommendations for areas of future research or monitoring to address gaps in information. It includes a recommendation that the State of Michigan set advisory limits for PFAS other than PFOA and PFOS, and for the state to develop new drinking water standards "based on weight of evidence and convergence of toxicological and epidemiological data", suggesting that the current national advisory level of 70 ppt for PFOA + PFOS may be too high. It also recommends gathering research to better understand exposure routes for PFAS, including biosolids and how PFAS is transferred between biosolids, crops and groundwater.[96]

- 19 March 2019 The Concord Monitor reported that the New Hampshire House Bill 494, which was to be introduced in March, would compel Department of Environmental Services (DES) of the state of New Hampshire to enact new standards that would force "polluters to stop the flow of toxins" from the Superfund Coakley landfill site in North Hampton and Greenland that threatens the drinking water of five Seacoast towns and contaminate surface water bodies in the surrounding area.[97] The contamination represents "some of the highest levels ever found anywhere of PFNA", one of the perfluorinated chemicals.[97][98]

- April 2019 The Michigan PFAS Action Response Team (MPART) and its agencies released public health drinking water screening levels for 5 PFAS compounds: PFOA, PFOS, PFBS, PFHxS, and PFNA.[69]

- May 2019 The Stockholm Convention COP "decided to eliminate production and use of two important toxic POPs, PFOA and Dicofol" as recommended by the United Nation's Stockholm Convention's Persistent Organic Pollutants Review Committee (POPRC-15).[99]

- 29 May 2019 The city of Lake Elmo, Minnesota and 3M reached a settlement over the drinking water contamination lawsuit. 3M will pay $2.7 million to Lake Elmo's water account and will "transfer 180 acres of farmland" to Lake Elmo which is "valued at $1.8 million."[18]

- 29 May 2019 The state of New Hampshire filed a lawsuit against Dupont, 3M, and other companies, for their roles in the crisis in drinking water contamination in the United States. The lawsuit claims that the polluted water is the result of the manufacture and use of perfluorinated chemicals, a group of more than 4,000 compounds collectively known as PFAS.[2]

- June 2019 In what was described as a "huge step toward cleaning up the prevalence of—and prevent further contamination from—PFAS chemicals in ground, surface and drinking water"[100] the Department of Environmental Services of the state of New Hampshire submitted a "final rulemaking proposal" for new, lower maximum contaminant levels (MCLs)/drinking water standards and ambient groundwater quality standards (AGQS) for four per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) and perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS)."[101] When implemented on 1 October, following the approval of and adoption by New Hampshire's Joint Legislative Committee on Administrative Rules (JLCAR) on 18 July, New Hampshire will be able to "compel polluters to clean up contaminated sites."[100] One of the contaminated sites is the "Coakley landfill in North Hampton and Greenland."[100]

- 23 September 2019 On 23 September 2019 the CDC and ATSDR announced that they had "established cooperative agreements with seven partners to study the human health effects of exposures to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) through drinking water at locations across the nation."[102]

- September 2019 Andrew R. Wheeler, EPA Administrator, met with industry lobbyists and said that "Congressional efforts to clean up legacy PFAS pollution in the National Defense Authorization Act for fiscal 2020" were "just not workable." Wheeler refuses to "designate PFAS chemicals as "hazardous substances" under the Superfund law."[33]

- 1 October 2019 A lawsuit was filed in the Merrimack County Superior Court by 3M, Plymouth Water & Sewer District, and two others against the state Department of Environmental Services to prevent the new permitted levels for PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, and PFHxS from being implemented.[101]

- 4 October 2019 At the 15th meeting of the United Nation's Stockholm Convention's Persistent Organic Pollutants Review Committee (POPRC-15) held in Rome, on 4 October, over 100 scientific experts representing many countries, "recommended that a group of hazardous chemicals"—"Perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS), its salts, and PFHxS-related compounds"—be eliminated in order to better protect human health and the environment from its harmful impacts."[99] PFHxS and PFHxS-related salts and compounds are a "group of industrial chemicals used widely in a number of consumer goods as a surfactant and sealant including in carpets, leather, clothing, textiles, fire-fighting foams, papermaking, printing inks and non-stick cookware. They are known to be harmful to human health including the nervous system, brain development, endocrine system and thyroid hormone."[99]

- 25 November 2019 Judge Edmund A. Sargus Jr. of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Ohio ruled in favor of the plaintiffs against DuPont in the court case E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co. C-8 Pers. Injury Litig., S.D. Ohio, No. 2:13-md-02433, 11/25/19.. Judge Sargus blocked DuPont from defending against claims that were decided in the set of previous trials, involving residents of Ohio and West Virginia who say PFAS from E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co.'s Washington Works manufacturing facility, which was located along the Ohio River, "contaminated their water, and caused cancer and other diseases". The company had argued that their "release of PFOA amounted to negligence".[56]

2020s[edit]

- 14 January 2020 Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel filed a lawsuit against 17 companies, including 3M, Chemours, and DuPont, for hiding known health and environmental risks from the state and its residents. Nessel's complaint identifies 37 sites with known contamination[103]

- 10 March 2020 EPA announced its proposed regulatory determinations for two PFAS in drinking water. In a Federal Register notice the agency requested public comment on whether it should set maximum contaminant levels for PFOA and PFOS in public water systems.[104]

- 3 August 2020 The Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE, formerly MDEQ) enacts some of the strictest drinking water standards in the country in the form of maximum contaminant levels (MCLs), limiting PFOA at 8 ppt and PFOS at 16 ppt (lowered from the previous limit of 70 ppt for both), and introduces MCLs for 5 previously unregulated PFAS compounds – PFNA at 6 ppt, PFHxA at 400,000 ppt, PFHxS at 51 ppt, PFBS at 420 ppt, and HFPO-DA at 370 ppt. The passage of these contaminant levels marks the first time Michigan has developed its own MCLs rather than adopting or modifying existing federal standards.[105][106]

- 3 March 2021 EPA announced that it will develop national drinking water standards for PFOA and PFOS.[107]

- 17 March 2021 EPA announced plans to revise wastewater standards (effluent guidelines) for manufacturers of PFAS chemicals.[108]

- 21 April 2021 3M sues the state of Michigan, seeking to invalidate its new drinking water standards.[109]

- July 2021 The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) updated its 'Do Not Eat' advisory for white-tailed deer at Clark's Marsh (near former WAFB) from 5 to 3 miles. After testing an additional 44 deer near Clark's Marsh MDHHS was able to identify a relationship between PFOS detections in deer liver with the deer's distance from Clark's Marsh. The Michigan DNR estimated a 3-mile area as the expected travel range of white-tailed deer in the area. In both muscle and liver samples, the highest level of PFAS chemical was PFOS, at 82.6 parts per billion (ppb) in a muscle sample and 2,970 ppb in a liver sample.[110][111]

- 14 September 2021 EPA announced plans to revise effluent guidelines for businesses that conduct chromium electroplating operations and discharge PFAS in their wastewater.[112][113]

- 21 October 2021 EPA announced, "a whole-of-agency approach" for addressing PFAS, titled "PFAS Strategic Roadmap: EPA's Commitments to Action 2021-2024".[114]

- 27 December 2021 EPA published a regulation requiring drinking water utilities to conduct monitoring for 29 PFAS compounds. The data are to be collected during 2023 to 2025. The agency may use the monitoring data to develop additional regulations.[115][116]

- 13 April 2022 14 State Attorneys General signed a letter to the EPA urging the agency to use its current-year funding to "meet commitments and deadlines outlined in its PFAS Strategic Roadmap".[117]

- 15 June 2022 The EPA issued interim updated drinking water health advisories for PFOS and PFOA, drastically lowering previous levels from 70 ppt for both to 0.02 ppt for PFOS and 0.004 ppt for PFOA. The agency also issued final health advisories for HFPO-DA and its ammonium salt GenX at 10 ppt and for PFBS at 2000 ppt.[118]

- 22 June 2023 the American multinational 3M reached a $10.3bn settlement with a host of US public water systems to resolve water pollution claims tied to PFASs.[119] Three other major chemicals companies – Chemours, DuPont and Corteva – have reached an agreement in principle for $1.19bn to settle claims they contaminated US public water systems with PFAS.[119]

Relevant compounds[edit]

| Compound | Chemical formula | Structural model | 3D image | Other names | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

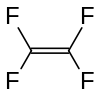

| Tetrafluoroethylene (TFE) | C2F4 |

|

|

Tetrafluoroethene, Perfluoroethylene, Perfluoroethene | Precursor to PTFE (Teflon) |

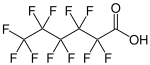

| Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) | C8HF15O2 |

|

perfluorooctanoic acid, PFOA, C8, perfluorooctanoate, perfluorocaprylic acid, FC-143, F-n-octanoic acid, PFO | ||

| Perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) | C9HF17O2 | As ion: perfluorononanoate | Here the health effects of PFNA, one of the ten most common PFAS, has been more widely studied.[81] Some of the "highest levels" of PFNA "ever found anywhere" are present in the Superfund Coakley landfill site in North Hampton, New Hampshire, and Greenland, New Hampshire.[97] | ||

| Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) | C8HF17O3S | As ion: perfluorooctanesulfonate | |||

| Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) | (C2F4)n |

|

Syncolon, Fluon, Poly(tetrafluroethene), Poly(difluoromethylene), Poly(tetrafluoroethylene), Teflon | ||

| Perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS) | C6HF13O3S |

|

|

Perfluorohexane-1-sulphonic acid | |

| Perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA) | C6HF11O |

|

|

Perfluoro-1-pentanecarboxylic acid | |

| GenX | C6H4F11NO3 | GenX, FRD-902, Ammonium 2,3,3,3-tetrafluoro-2-(heptafluoropropoxy)propanoate | Replacement for PFOA developed by DuPont. GenX is created by combining two HFPO molecules to form HFPO-DA fluoride which is then converted to HFPO-DA. GenX is the ammonium salt of HFPO-DA. When GenX contacts water it releases HFPO-DA.

This ammonium salt is the chemical compound trademarked by Chemours as GenX, though many other compounds related to the GenX process are informally referred to as GenX.[120] | ||

| Hexafluoropropylene oxide (HFPO) | C3F6O |

|

|

2,2,3-Trifluoro-3-(trifluoromethyl)oxirane | Precursor to GenX |

| Hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid fluoride (HFPO-DA fluoride) | C6F12O2 | 2,3,3,3-tetrafluoro-2-(heptafluoropropoxy)propionyl fluoride | Precursor to GenX | ||

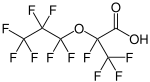

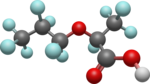

| Hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (HFPO-DA) | C6HF11O3 |

|

|

FRD-903, 2,3,3,3-tetrafluoro-2-(heptafluoropropoxy)propanoic acid | Chemical used in the GenX process. GenX hydrolyzes in the presence of water to form HFPO-DA.[120] |

| Perfluorobutanesulfonic acid (PFBS) | C4HF9O3S |

|

|

References[edit]

- ^ a b "PFAS". Merit Laboratories, Inc. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ a b Schlanger, Zoë (3 October 2019). "Dupont and 3M knowingly contaminated drinking water across the US, lawsuits allege". Quartz. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ a b Fact Sheet: Draft Toxicity Assessments for GenX Chemicals and PFBS (Report). EPA. 14 November 2018.

- ^ a b Sedlak, Meg (October 2016). "Profile - Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS)" (PDF). sfei.org. San Francisco Estuary Institute. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ http://www.mwra.com/01news/2019/2019-11-PFAS-fact-sheet.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "DuPont Timeline". Delaware Online. 11 December 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ "Company Profiles for Students", 3M, 1 January 1999, archived from the original on 18 May 2013

- ^ "The History of 3M: from humble beginnings to Fortune 500". nd. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ a b "Haskell Laboratory of Industrial Toxicology". Industrial and Engineering Chemistry. News Edition. 13 (3): 44–46. 10 February 1935. doi:10.1021/cen-v013n003.p044 (inactive 31 January 2024). ISSN 0097-6423. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link) - ^ a b c d e Lerner, Sharon (11 August 2015). "The Teflon Toxin: DuPont and the Chemistry of Deception". The Intercept. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ Michaels, David (1995). "When Science Isn't Enough: Wilhelm Hueper, Robert A.M. Case and the Limits of Scientific Evidence in Preventing Occupational Bladder Cancer". International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health. 1 (3): 278–288. doi:10.1179/oeh.1995.1.3.278. PMID 9990166.

- ^ "Haskell Laboratory of Industrial Toxicology". C&EN Global Enterprise. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ "Dr. Roy J. Plunkett: Discoverer of Fluoropolymers" (PDF). The Fluoropolymers Division Newsletter (Summer): 1–2. 1994. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2003.

- ^ a b Lyons, Richard D. (15 May 1994). "Roy J. Plunkett Is Dead at 83; Created Teflon While at Du Pont". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ "Roy J. Plunkett". Science History Institute. 14 December 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ "Inventor profile". National Inventors Hall of Fame Foundation, Inc. 2007. Archived from the original on 17 January 2008. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ a b Plunkett, Roy J. (15–18 April 1986). Seymour, Roy B.; Kirshenbaum, G.S. (eds.). The History of Polytetrafluoroethylene: Discovery and Development. Proceedings of the Symposium on the History of High Performance Polymers at the American Chemical Society Meeting. High Performance Polymers: Their Origin and Development. New York: Elsevier. ISBN 0-444-01139-0.

- ^ a b c d e Sepic, Matt; Kirsti Marohn (21 May 2019). "3M, Lake Elmo settle for $2.7M, land transfer in drinking water lawsuit". MPR News. Lake Elmo. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d City of Lake Elmo v. 3M Company. Document 41 (D. Minn. 2017)

- ^ a b Vaughn, Barry; Winquist, Andrea; Steenland, Kyle (1 January 2013). "Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) Exposures and Incident Cancers among Adults Living Near a Chemical Plant". Environmental Health Perspectives. 121 (11–12): 1313–1318. doi:10.1289/ehp.1306615. PMC 3855514. PMID 24007715.

- ^ Nordby, Gordon I.; Luck, J. Murray (1 August 1955). "Perfluorooctanoic acid interactions with human serum albumin". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 219 (1): 399–404. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)65805-3. PMID 13295293.

- ^ Place, Benjamin J.; Field, Jennifer A. (3 July 2012). "Identification of Novel Fluorochemicals in Aqueous Film-Forming Foams (AFFF) Used by the US Military". Environmental Science and Technology. 46 (13): 7120–7127. doi:10.1021/es301465n. ISSN 0013-936X. PMC 3390017. PMID 22681548.

- ^ a b c d Lerner, Sharon (10 February 2018). "The Military's Toxic Firefighting Foam Disaster". Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ a b c Pearson, Marjorie (nd). "900 Bush Avenue: The House that Research Built: Early Years in Saint Paul". Saint Paul Historical. Historic Saint Paul. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017. Marjorie Pearson, the author of the article worked for Summit Envirosolutions, Inc.

- ^ Ross, Rachel; Tech (30 April 2019). "What Are PFAS?". Live Science. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ a b "Robert W. Gore", Science History Institute, 29 June 2016, retrieved 9 October 2019

- ^ Schlanger, Zoë (13 June 2019). "3M knew it was contaminating the food supply back in 2001". Quartz. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ Lerner, Sharon (31 July 2018). "3M Knew About the Dangers of PFOA and PFOS Decades Ago, Internal Documents Show". The Intercept. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ a b c "Per- and Poly-Fluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS): Health effects and exposure pathways" (PDF), Department of Health, Australian Government, p. 4, nd, retrieved 8 October 2019

- ^ a b c Van Noordwyk, Hugh J.; Santoro, Michael A. (1978). "Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company's Hazardous Waste Program". Environmental Health Perspectives. 27: 245–249. doi:10.2307/3428885. ISSN 0091-6765. JSTOR 3428885. PMC 1637293. PMID 738241.

- ^ a b "Minnesota Mining to clean up waste dump". The New York Times. Oakdale, Minnesota. 21 July 1983. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Rich, Nathaniel (6 April 2016). "The Lawyer Who Became DuPont's Worst Nightmare". New York Times. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ a b Ayala, Christine (1 October 2019). "EPA on 'forever chemicals': Let them drink polluted water". The Hill. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ a b c Barboza, David (18 May 2000). "E.P.A. Says It Pressed 3M for Action on Scotchgard Chemical". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Avsec, Robert P. (17 October 2016). "How safe is firefighting foam?". FireRescue1. Retrieved 4 October 2019. Firerescue1 is an official partner of International Association of Fire Chiefs

- ^ Funakoshi, Minami (17 April 2013). "China Reacts to David Barboza's Pulitzer Prize". The Atlantic. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ Barboza, David (17 May 2000). "3M Says It Will Stop Making Scotchgard". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ Blake, Mariah (27 August 2015). "A Toxic Chemical Ruined The Lives Of These People — And It's Probably In Your Blood". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ "DuPont lawsuits (re PFOA pollution in USA)". Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ Lerner, Sharon (20 August 2015). "The Teflon Toxin: How DuPont Slipped Past the EPA". The Intercept. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ a b Bell, Scott (18 May 2018). "PFAS - Emerging, But Not New". LimnoTech. Archived from the original on 12 September 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "PFAS Sampling in Lakes and Streams". www.michigan.gov. Archived from the original on 27 April 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ Giesy, John P.; Kannan, Kurunthachalam (1 April 2001). "Global Distribution of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate in Wildlife". Environmental Science & Technology. 35 (7): 1339–1342. Bibcode:2001EnST...35.1339G. doi:10.1021/es001834k. ISSN 0013-936X. PMID 11348064. S2CID 8974107.

- ^ a b c d Nicholson, Trent (June 2007). "The safety & benefits of AFFF agents – Let the facts speak?" (PDF). Industrial Fire Journal (68): 70–75. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ a b "Robert Bilott (2017)". Right Livelihood Award. 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ "Amended class action complaint" (PDF), Hill, Peterson, Carper, Bee and Deitzler (HPCBD), 1 August 2001

- ^ Kelly, Sharon (4 January 2016). "DuPont's deadly deceit: The decades-long cover-up behind the "world's most slippery material"". Salon. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "History of Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Minnesota". Minnesota Department of Health. nd. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ "ECHA - Fighting fire with fluorine-free foams".

- ^ Thacker, Paul D. (22 February 2006), "The Weinberg proposal", Environmental Science & Technology, 40 (9): 2862, doi:10.1021/es0630137, PMID 16719079

- ^ Thacker, Paul D. (22 February 2006). "The Weinberg proposal". Environmental Science & Technology. 40 (9): 2862. doi:10.1021/es0630137. PMID 16719079.

- ^ a b c d e f g The Cancer-Linked Chemical In America's Tap Water. Bloomberg. Bloomberg Technology Decrypted. 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ Schaefer, Ted H. (19 June 2003), Aqueous foaming composition, retrieved 6 October 2019

- ^ Mordock, Jeff (1 April 2016). "Taking on DuPont: Illnesses, deaths blamed on pollution from W. Va. plant". Delaware Online. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ "C-8 Class Action Settlement", Hill, Peterson, Carper, Bee & Deitzler, nd, retrieved 9 December 2019

- ^ a b c Gilmer, Ellen M. (26 November 2019). "PFAS Plaintiffs Score Partial Win Over DuPont in Ohio Litigation". Bloomberg. Environment and Energy. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ a b James E., Casto (4 January 2019). "C8 Controversy". West Virginia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ Kulikov, Oleg (10 August 2005). "Novel processing aids for extrusion of polyethylene" (PDF). Journal of Vinyl and Additive Technology. 11 (3): 127–131. doi:10.1002/vnl.20048. ISSN 1548-0585. S2CID 137388589. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ Lerner, Sharon (8 October 2019). "Toxic PFAS Chemicals Found in Artificial Turf". The Intercept. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ a b Zanolli, Lauren (23 May 2019). "Why you need to know about PFAS, the chemicals in pizza boxes and rainwear". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ Paustenbach, Dennis J.; Panko, Julie M.; Scott, Paul K.; Unice, Kenneth M. (January 2007). "A methodology for estimating human exposure to perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA): a retrospective exposure assessment of a community (1951-2003)". Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. 70 (1): 28–57. doi:10.1080/15287390600748815. ISSN 1528-7394. PMID 17162497. S2CID 1653667.

- ^ a b c d Anderson, Jim (30 September 2013). "Rising in the East: Dayton's Bluff envisions 'a new day'". Star Tribune. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ NATIONAL EXPOSURE RESEARCH LABORATORY, OFFICE OF RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT (September 2009). "METHOD 537. DETERMINATION OF SELECTED PERFLUORINATED ALKYL ACIDS IN DRINKING WATER BY SOLID PHASE EXTRACTION AND LIQUID CHROMATOGRAPHY/TANDEM MASS SPECTROMETRY (LC/MS/MS)". U.S. EPA. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- ^ "Addendum for Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Michigan Current State of Knowledge and Recommendations for Future Actions" (PDF). Michigan.gov. August 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "Oscoda Area, Oscoda, Iosco County". www.michigan.gov. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ "PFAS Sampling in Lakes and Streams". www.michigan.gov. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ Emerging contaminants: perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) (PDF). Federal Facilities Restoration and Reuse Office (FFRRO) (Report). 2014. p. 10. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ Viberg, Henrik; Eriksson, Per (2011). "Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)". Reproductive and Developmental Toxicology. Elsevier. pp. 623–635. ISBN 978-0-12-382032-7. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ a b "Overview of Michigan's Screening Values & MCLs Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)" (PDF). Michigan.gov. September 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Snider, Annie (14 May 2018). "White House, EPA headed off chemical pollution study". POLITICO. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ "Why Is 3M Company (MMM) Down 6.1% Since its Last Earnings Report?". Yahoo. 26 February 2018.

- ^ "Fact sheet on AFFF fire fighting agents" (PDF). Fire Fighting Foam Coalition. 2017. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ Prohibition of Certain Toxic Substances Regulations (PDF). The Government of Canada (Report). 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ Rinehart, Earl (5 January 2017). "Jury awards $10.5 million in punitive damages in DuPont cancer case". The Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ "Lawyer who took on DuPont has book coming out". AP News. New York. 10 July 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ a b Nair, Arathy S. (13 February 2017). "DuPont settles lawsuits over leak of chemical used to make Teflon". Reuters. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ Kary, Tiffany; Cannon, Christopher (2 November 2018). "Cancer-Linked Chemicals Created by 3M Could Be In Your Groundwater". Bloomberg. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ Macfarlane, Daniel (1 November 2018). "These chemicals in North American waters could spark a health crisis in Canada". Macleans. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ a b VanGilder, Rachel (25 September 2017). "Toxic tap water: Neighbors worry about illegal dump sites". www.woodtv.com. Archived from the original on 19 May 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ Ellison, Garret (13 November 2017). "Michigan creates multi-agency PFAS pollution response team". MLive. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Potential health effects of PFAS chemicals | ATSDR". 26 November 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ Ellison, Garret (9 January 2018). "Michigan abruptly sets PFAS cleanup rules". MLive. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ Email chain on PFAS study (PDF), January 2018, retrieved 4 October 2019

- ^ a b "Bipartisan Outrage as EPA, White House Try to Cover Up Chemical Health Assessment". Union of Concerned Scientists. 16 May 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ Email chain on PFAS-CDC study (PDF), January 2018, retrieved 4 October 2019

- ^ "Minnesota 3M PFC Settlement". The State of Minnesota's 3M PFC Settlement Portal. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ Wells, retrieved 6 October 2019

- ^ Public Consultation Report (PDF) (Report). Australia: PFAS Expert Health Panel. March 2018. p. 377. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ Toxicological Profile for Perfluoroalkyls (PDF). Draft for Public Comment. Atlanta, Georgia: ATSDR and CDC. 21 June 2018. p. 697. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ "Availability of Draft Toxicological Profile: Perfluoroalkyls". Federal Register. 22 June 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ "PFAS levels in Michigan Deer and Eat Safe Wild Game Guidelines" (PDF). michigan.gov. 11 January 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ "GenX Frequently Asked Questions" (PDF). GenX Investigation. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (NCDEQ). 15 February 2018.

- ^ Beekman, M.; et al. (12 December 2016). "Evaluation of substances used in the GenX technology by Chemours, Dordrecht". National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM, The Netherlands). Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- ^ "What is the difference between PFOA, PFOS and GenX and other replacement PFAS?". PFOA, PFOS and Other PFASs. EPA. 18 February 2018.

- ^ "Basic Information on PFAS". PFOA, PFOS and Other PFASs. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 18 February 2018.

- ^ Savitz, David; Masten, Susan; Lau, Christopher; Jones, Dan; Field, Jennifer; Bartell, Scott (7 December 2018). "Scientific Evidence and Recommendations for Managing PFAS Contamination in Michigan" (PDF). Michigan.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Messmer, Mindi (19 March 2019). "My Turn: Lawmakers must step up to protect our water". Concord Monitor. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "New Hampshire HB494 | TrackBill".

- ^ a b c "UN experts recommend elimination of additional hazardous chemicals to protect human health and the environment". BRSMeas. 4 October 2019. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ a b c "NH acts to protect public health from PFAS". Fosters. Concord, New Hampshire. 4 October 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ a b McMenemy, Jeff (4 October 2019). "3M suit aims to block tougher PFAS standards for water in NH". Fosters. Concord, New Hampshire. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) and Your Health". ATSDR. CDC/ATSDR PFAS Related Activities. 23 September 2019. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ Oosting, Jonathan (14 January 2020). "Dana Nessel sues 3M, DuPont over 'unconscionable' PFAS pollution in Michigan". Bridge Michigan. Archived from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ EPA (2020-03-10). "Announcement of Preliminary Regulatory Determinations for Contaminants on the Fourth Drinking Water Contaminant Candidate List; Request for public comment." Federal Register, 85 FR 14098

- ^ "New state drinking water standards pave way for expansion of Michigan's PFAS clean-up efforts". Michigan.gov. 3 August 2020. Archived from the original on 3 January 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ Matheny, Keith (3 August 2020). "Michigan's drinking water standards for these chemicals now among toughest in nation". Detroit Free Press. Archived from the original on 31 January 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ EPA (2021-03-03). "Announcement of Final Regulatory Determinations for Contaminants on the Fourth Drinking Water Contaminant Candidate List." Federal Register, 86 FR 12272

- ^ EPA (2021-03-17). "Clean Water Act Effluent Limitations Guidelines and Standards for the Organic Chemicals, Plastics and Synthetic Fibers Point Source Category." Advance notice of proposed rulemaking. 86 FR 14560

- ^ Ellison, Garret (7 May 2021). "3M sues Michigan, seeks to invalidate PFAS drinking water rules". MLive. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "PFAS levels in Michigan Deer from the Oscoda Area, Iosco County" (PDF). michigan.gov. 22 April 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ "PFAS in Deer". michigan.gov. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ EPA (2021-09-14). "Preliminary Effluent Guidelines Program Plan 15." Notice of availability. Federal Register, 86 FR 51155

- ^ Preliminary Effluent Guidelines Program Plan 15 (PDF) (Report). EPA. September 2021. p. 6-4. EPA 821-R-21-003.

- ^ "PFAS Strategic Roadmap: EPA's Commitments to Action 2021-2024". EPA. 24 March 2022.

- ^ EPA (2021-12-27). "Revisions to the Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR 5) for Public Water Systems and Announcement of Public Meetings." 86 FR 73131

- ^ "Fifth Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule". EPA. 11 January 2022.

- ^ "ATTORNEYS GENERAL OF PENNSYLVANIA, MASSACHUSETTS, STATES OF NEW YORK, IOWA, MICHIGAN, MINNESOTA, MAINE, CONNECTICUT, OREGON, HAWAII, DELAWARE, WISCONSIN, NEW MEXICO, RHODES ISLAND" (PDF). www.michigan.gov. 13 April 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 April 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ "Drinking Water Health Advisories for PFAS Fact Sheet for Communities" (PDF). epa.gov. 15 June 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ a b "3M pays $10.3bn to settle water pollution suit over 'forever chemicals'". The Guardian. 22 June 2023. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ a b Hogue, Cheryl (12 February 2018). "What's GenX still doing in the water downstream of a Chemours plant?". Chemical & Engineering News. Archived from the original on 16 March 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.