→References: add source |

→Themes in his works: shorten title, add link |

||

| Line 166: | Line 166: | ||

Examples of [[postmodernism]] may also be found in Vonnegut's works. Postmodernism often entails a response to the theory that "science can reveal the truth about the world."{{sfn|Marvin|2002|p=16}} They contend that truth is subjective, rather than objective, as it is biased towards each individuals's beliefs and outlook on the world. Postmodernists often use [[unreliable narrator|unreliable]], [[first-person narration]], and narrative [[Postmodern literature#Fragmentation|fragmentation]]. While Vonnegut does use these elements in some of his works, he more distinctly focuses on the peril posed by individuals who find subjective truths, mistake them for objective truths, then proceed to impose these truths on others.{{sfn|Marvin|2002|pp=16–17}} |

Examples of [[postmodernism]] may also be found in Vonnegut's works. Postmodernism often entails a response to the theory that "science can reveal the truth about the world."{{sfn|Marvin|2002|p=16}} They contend that truth is subjective, rather than objective, as it is biased towards each individuals's beliefs and outlook on the world. Postmodernists often use [[unreliable narrator|unreliable]], [[first-person narration]], and narrative [[Postmodern literature#Fragmentation|fragmentation]]. While Vonnegut does use these elements in some of his works, he more distinctly focuses on the peril posed by individuals who find subjective truths, mistake them for objective truths, then proceed to impose these truths on others.{{sfn|Marvin|2002|pp=16–17}} |

||

=== Themes |

=== Themes === |

||

{{anchor|Themes: Society}} |

{{anchor|Themes: Society}} |

||

;Society and social inequity |

;Society and social inequity |

||

Vonnegut was a vocal critic of the society in which he lived, and this was reflected in his writings. Several key themes relating to man's societies recur in Vonnegut's works, such as wealth, the lack of it, and its unequal distribution among a society's members. In ''The Sirens of Titan'', the novel's protagonist, Malachi Constant, is exiled to one of [[Saturn]]'s moons, [[Titan (moon)|Titan]], as a result of his vast wealth, which has made him arrogant and wayward.{{sfn|Marvin|2002|pp=19, 44–5}} In ''God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater'', one is hard-pressed to decipher which set of character's circumstances are worse – the rich, or the poor – as the lives of both group's members are ruled by their wealth or their poverty.{{sfn|Marvin|2002|p=19}} And in ''Hocus Pocus'', the protagonist is named Eugene Debs Hartke, a homage to Vonnegut's socialist views.{{sfn|Sharp|2006|p=1364}} In ''Kurt Vonnegut: A Critical Companion'', Thomas F. Marvin states that, "Vonnegut points out that, left unchecked, capitalism will erode the democratic foundations of the United States." Marvin states further that when a "hereditary aristocracy" develops, where wealth is inherited along familial lines, it "depriv[es] other Americans of the opportunity to rise out of poverty."{{sfn|Marvin|2002|p=19}} Vonnegut also often laments social Darwinism, and a "survival of the fittest" view of society. He points out that social Darwinism leads to a society that inculpates its poor with their own misfortune, and fails to assist them out of their circumstances because "they deserve their fate".{{sfn|Sharp|2006|pp=1364–65}} Additionally, Vonnegut also confronts the idea of volition in a number of his pieces. In ''Slaughterhouse-Five'' and ''Timequake'' the characters have no free will; in ''Breakfast of Champions'', a single character concludes that all free will is concentrated in them; and in ''Cat's Cradle'', there is a religion that views free will as [[heresy|heretical]].{{sfn|Sharp|2006|p=1366}} |

Vonnegut was a vocal critic of the society in which he lived, and this was reflected in his writings. Several key themes relating to man's societies recur in Vonnegut's works, such as wealth, the lack of it, and its unequal distribution among a society's members. In ''The Sirens of Titan'', the novel's protagonist, Malachi Constant, is exiled to one of [[Saturn]]'s moons, [[Titan (moon)|Titan]], as a result of his vast wealth, which has made him arrogant and wayward.{{sfn|Marvin|2002|pp=19, 44–5}} In ''God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater'', one is hard-pressed to decipher which set of character's circumstances are worse – the rich, or the poor – as the lives of both group's members are ruled by their wealth or their poverty.{{sfn|Marvin|2002|p=19}} And in ''Hocus Pocus'', the protagonist is named [[Eugene Debs]] Hartke, a homage to Vonnegut's socialist views.{{sfn|Sharp|2006|p=1364}} In ''Kurt Vonnegut: A Critical Companion'', Thomas F. Marvin states that, "Vonnegut points out that, left unchecked, capitalism will erode the democratic foundations of the United States." Marvin states further that when a "hereditary aristocracy" develops, where wealth is inherited along familial lines, it "depriv[es] other Americans of the opportunity to rise out of poverty."{{sfn|Marvin|2002|p=19}} Vonnegut also often laments social Darwinism, and a "survival of the fittest" view of society. He points out that social Darwinism leads to a society that inculpates its poor with their own misfortune, and fails to assist them out of their circumstances because "they deserve their fate".{{sfn|Sharp|2006|pp=1364–65}} Additionally, Vonnegut also confronts the idea of volition in a number of his pieces. In ''Slaughterhouse-Five'' and ''Timequake'' the characters have no free will; in ''Breakfast of Champions'', a single character concludes that all free will is concentrated in them; and in ''Cat's Cradle'', there is a religion that views free will as [[heresy|heretical]].{{sfn|Sharp|2006|p=1366}} |

||

{{anchor|Themes: Loneliness and loss of purpose}} |

{{anchor|Themes: Loneliness and loss of purpose}} |

||

Revision as of 17:34, 4 August 2015

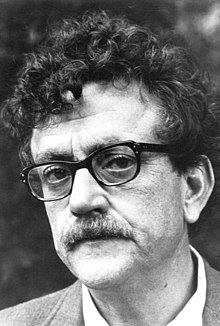

Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. | |

|---|---|

Vonnegut in 1972 | |

| Born | November 11, 1922 Indianapolis, Indiana |

| Died | April 11, 2007 (aged 84) New York City, New York |

| Occupation | Author, humorist, essayist. |

| Nationality | American |

| Genre | Satire Gallows humor Science fiction |

| Notable works | |

| Spouse | Jane Marie Cox (1945–1971; divorce) Jill Krementz (1979–2007; his death) |

| Children | Biological children:

|

| Signature | |

Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. (/ˈvɒn[invalid input: 'ɨ']ɡət/; November 11, 1922 – April 11, 2007) was an American writer, essayist and humorist. In a career spanning over 50 years, Vonnegut published fourteen novels, three short story collections, five plays and five works of non-fiction. He is most famous for his darkly satirical, best-selling novel Slaughterhouse-Five, which tells of the life of Billy Pilgrim.

Born in Indianapolis, Indiana, Vonnegut attended Cornell University, but dropped out in January 1943 and enlisted in the United States Army. He was deployed to Europe to fight in the Second World War, and lived through the Allied bombing of Dresden while bunkering in a meat locker. Afterwards, Vonnegut married Jane Marie Cox, with whom he had three children. He later adopted his sister's three children, after she died of cancer and her husband died in a train accident.

Vonnegut published his first novel, Player Piano, in 1952. The novel was reviewed positively, but was not commercially successful. In the nearly twenty years that followed, Vonnegut published several novels which were only tepidly successful, such as Cat's Cradle (1963) and God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (1964). Vonnegut's magnum opus, however, was his immediately successful sixth novel, Slaughterhouse-Five. The book's antiwar sentiment resonated with its readers amidst the ongoing Vietnam War, and its reviews were generally positive. After its release, Slaughterhouse-Five rocketed to the top of The New York Times Best Seller list, thus thrusting Vonnegut into fame. He was invited to do speeches, lectures and commencement addresses around the country, and received numerous prestigious awards and honours.

Later in his career, Vonnegut published several autobiographical, essay and short story collections, including Fates Worse Than Death (1991), and A Man Without a Country (2005). After his death, he was hailed as a "darkly humorous social critic and the premier novelist of the counterculture." Vonengut's son Mark published a compilation of his father's unpublished compositions, titled Armageddon in Retrospect. Such tributes as the Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library were staged in Vonnegut's honour, and numerous scholarly works were released, examining Vonnegut's writing and humor.

Biography

Family and early life

Vonnegut was born on November 11, 1922 in Indianapolis, Indiana, the youngest of three children of Kurt Vonnegut, Sr. and his wife Edith (née Lieber). His older siblings were Bernard (born 1914) and Alice (born 1917). Vonnegut was almost entirely descended from German immigrants who settled in the United States in the mid-19th century; his patrilineal great-grandfather, Clemens Vonnegut of Westphalia, Germany, settled in Indianapolis and founded the Vonnegut Hardware Company. Kurt's father, and his father before him, were architects; the architecture firm under Kurt, Sr. was quite successful, designing such buildings as the Das Deutsche Haus (now called "The Athenæum"), the Indiana headquarters of the Bell Telephone Company, and the Fletcher Trust Building.[1] Vonnegut's mother was born into Indianapolis high society, as her family, the Liebers, were among the wealthiest in the city as a result of their impeccably prosperous brewery.[2]

Kurt, Sr. married Edith Lieber on November 22, 1913. Although both were fluent German speakers, the ill-feeling toward that country during and after World War I caused the Vonneguts to abandon the culture to show their American patriotism, and they never taught their youngest son German or introduced him to German literature and tradition, leaving him feeling "ignorant and rootless".[3][4] Vonnegut later credited Ida Young, his family's African-American cook and housekeeper for the first ten years of his life, with much of his rearing and instillment of values. "[She] gave me decent moral instruction and was exceedingly nice to me. So she was as great an influence on me as anybody." Vonnegut described Young as "humane and wise", adding that "the compassionate, forgiving aspects of [his] beliefs" came from her.[5]

The financial security and social prosperity that the Vonneguts once enjoyed was destroyed in matter of years. The Liebers's successful brewery was closed in 1921 after the advent of Prohibition in the United States. When the Great Depression hit, few people were financially able to build during the era, causing clients at Kurt, Sr.'s architectural firm to become scarce.[6] Vonnegut's brother and sister had finished their primary and secondary educations in private schools, but Vonnegut was placed in a public school, called "Public School No. 43".[7] He was not begrudged at this,[a] but both of his parents were affected deeply by their economic misfortune. His father withdrew from normal life and became a "dreamy artist".[9] His mother became depressed, withdrawn, bitter and abusive. She labored to regain the family's wealth and status and expressed hatred "as corrosive as hydrochloric acid" for her husband.[10][b] Edith Vonnegut forayed into writing and tried to sell short stories to magazines like Collier's and The Saturday Evening Post with no success.[3]

High school and Cornell

Vonnegut began his high school career in 1936 (aged 14) at Shortridge High School in Indianapolis. While at the school, he played clarinet in the school's band and volunteered as an editor for the Tuesday edition of the school's newspaper, The Shortridge Echo, one of only two daily-operating school newspapers in the U.S. Vonnegut said his tenure with the Echo allowed him to write for a large audience of people—his fellow students—rather than for a teacher, an experience he said was "fun and easy."[1] "It just turned out that I could write better than a lot of other people," Vonnegut observed. "Each person has something he can do easily and can’t imagine why everybody else has so much trouble doing it." For him, that was writing.[7]

"Cornell was a boozy dream, partly because of booze itself, and partly because I was enrolled exclusively in courses I had no talent for. My father and brother agreed that I should study chemistry, since my brother had done so well with chemicals at M.I.T."[12]

–Kurt Vonnegut, Interview with The Paris Review, 1977

After graduating from Shortridge in 1940, Vonnegut moved to Ithaca, New York and enrolled in Cornell University. He wanted to study the humanities or become an architect like his father, but was urged by his father,[c] and brother, a scientist, to study a "useful" disciple.[1] Vonnegut majored in biochemistry, but he had little proficiency in the area, and was indifferent towards his studies.[14] He did find success in other areas of Cornell, however. He became a member of the Delta Upsilon fraternity,[15] and volunteered for the university's daily-running newspaper, The Cornell Daily Sun, first serving as a staff writer, then as an editor.[16] By the end of his freshman year, he was writing a column, titled "Innocents Abroad", where jokes from other publications were rerun. He later worked on the column "Well All Right", penned by himself. It focused on pacifism, which he strongly supported.[7] In the column, he opposed U.S. intervention in World War II.[17]

Second World War

The attack on Pearl Harbor brought the U.S. into the war. Vonnegut was a member of ROTC, but a satirical article in Cornell's newspaper and poor grades cost him his place there. This meant that should he leave Cornell, he would most likely be drafted into the army. He was placed on academic probation in May 1942, and dropped out the following January. Rather than wait to be drafted, he enlisted in the army and in March 1943, reported to Fort Bragg, North Carolina for basic training.[18] While in training, Vonnegut was taught how to operate the 240-millimetre (9.4 in) howitzer, the largest mobile artillery piece in operation during the era. He later received instruction in mechanical engineering from the Carnegie Institute of Technology and the University of Tennessee, as part of the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP).[13] In early 1944, the ASTP was cancelled, due to the army's need for soldiers for Operation Overlord, and he was ordered to an infantry battalion at Camp Atterbury, south of Indianapolis in Edinburgh, Indiana.[19] He lived so close to his home that he was "able to sleep in [his] own bedroom and use the family car on weekends." One of those weekends, May 14, 1944, Vonnegut returned home on leave for Mother's Day to discover that his mother had committed suicide the previous night by overdosing on sleeping pills.[20][d]

Vonnegut had little time to grieve. Three months after Edith Vonnegut's death, he was deployed as an intelligence scout with the 106th Infantry Division, despite having little infantry training. Several months after his deployment, Vonnegut fought in the Battle of the Bulge, the final German offensive of the war.[20] On December 22, 1944, he was captured by the German (Wehrmacht) army, along with fifty other American soldiers.[21] Vonnegut was taken by boxcar to a prison camp south of the Saxon city of Dresden. During the journey, the prisoner trains were bombed by the Royal Air Force, killing about 150 people.[22] After arriving, the detainees were split into groups—officers and privates.[20] As a private, Vonnegut was sent to Dresden, the "first fancy city [he had] ever seen". He lived in a slaughterhouse when he got to the city, and worked in a factory which made malt syrup for pregnant women. Vonnegut recalled the sirens going off whenever another city was getting bombed. They never expected Dresden to get bombed, Vonnegut said. "There were very few air-raid shelters in town and no war industries," he recalled, "just cigarette factories, hospitals, clarinet factories."[12]

However, when the sirens went off on the night of February 13, 1945, it was Dresden that had become the target of the Allied forces. In the hours and days that followed, the Allies engaged in a fierce bombing of the city.[20] The offensive subsided on February 15, with tens of thousands of people dead. Vonnegut marveled at the level of both the destruction in Dresden and the secrecy that attended it. He had managed to survive by bunkering in a meat locker three storeys underground.[7] "It was cool there, with cadavers hanging all around," Vonnegut said. "When we came up the city was gone. [...] They burnt the whole damn town down."[12] Vonnegut and the other privates were put to work immediately after the bombing, excavating bodies from the rubble of the destroyed city.[23] He described the activity as a "terribly elaborate Easter-egg hunt".[12]

In a letter addressed to his father, Vonnegut said that the American prisoners-of-war were evacuated on-foot to the Saxony-Czechoslovakian border after General George Patton captured the Saxon city of Leipzig. They were then abandoned by the guards that accompanied them. Vonnegut had reached a prisoner-of-war repatriation camp in Le Havre, France by May 29, 1945, with the help of several Russian troops.[22] He returned to the United States soon after, and was awarded a Purple Heart, about which he remarked, "I myself was awarded my country's second-lowest decoration, a Purple Heart for frost-bite."[24] He was released from the U.S. Army and sent back to Indianapolis.[25]

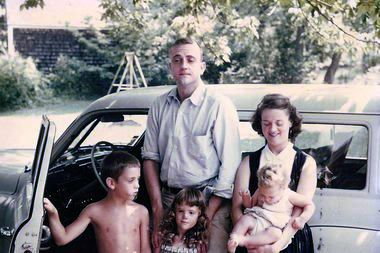

Marriage and early employment

After returned to the United States, 22-year-old Vonnegut married Jane Marie Cox, his high school love and classmate since kindergarten, on September 1, 1945. The pair relocated to Chicago, where Vonnegut enrolled in the University of Chicago as a graduate anthropology student, courtesy of the G.I. Bill, and worked for the Chicago City News Bureau at night. Vonnegut's wife accepted a scholarship from the university to study Russian at a graduate level. Neither of them would finish their degrees, however. Jane dropped out of the school after becoming pregnant with the couple's first son, Mark (born May 1947), and after Kurt's master's thesis, titled "Fluctuations Between Good and Evil in Simple Tales," which analyzed the "Ghost Dance" religious movement among Native Americans and an 1890 war associated with it, was unanimously rejected by the University of Chicago, he left the university without his degree.[e] Afterwards, General Electric (GE) employed Vonnegut as a publicist for the company's Schenectady, New York research laboratory. His brother Bernard had worked at GE since 1945, contributing significantly to an iodine-based invention to create precipitation. In 1949, Kurt and his wife had their second child, a daughter named Edith. Still working for GE, Vonnegut had his first piece, titled "Report on the Barnhouse Effect", published in the February 11, 1950 issue of Collier's, for which he received $750 (equivalent to $9,498 today).[27] Vonnegut wrote another story, after being coached by the fiction editor at Collier's, Knox Burger, and again sold it to the magazine, this time for for $950 (equivalent to $12,031 today). Burger suggested he quit GE, a prospect he had contemplated before. Vonnegut moved with his family to Cape Cod, Massachusetts to write full-time, and left GE in 1951.[28]

Vonnegut's first novel

At Cape Cod, Vonnegut published a number of pieces in magazines such as Collier's, The Saturday Evening Post, and Cosmopolitan, and made most of his money this way. He also did a stint as an English teacher, wrote copy for an advertising agency, and opened the first American Saab dealership, which eventually failed. In 1952, Vonnegut published his first novel, Player Piano, with Scribner's. The novel is set after a third world war, where factory workers have been replaced in favor of automated machines.[29]

Player Piano drew upon Vonnegut's experience as a young executive at GE. He satirized the drive to climb the corporate ladder, one that in Player Piano is rapidly disappearing as automation increases, putting even executives out of work. His central character, Paul Proteus, is given an ambitious wife, a backstabbing assistant, and a feeling of sympathy for the poor. Sent by his boss, Kroner, as a double agent among the poor (who have all the material goods they want, but little sense of purpose), he leads them in a machine-smashing, museum-burning revolution.[30] Player Piano expressed Vonnegut's opposition to McCarthyism, something made clear when the Ghost Shirts, the revolutionary organization Paul penetrates and eventually leads, is referred to by one character as "fellow travelers".[31]

In Player Piano, Vonnegut originated many of the techniques he would use in his later works. The comic, heavy-drinking Shah of Bratpuhr, an outsider to this dystopian corporate United States, is able to ask many questions that an insider would not think to ask, or would cause offense by doing so. For example, when taken to see the supercomputer EPICAC, an artificial intelligence, the Shah asks it "what are people for?" and receives no answer. Speaking for Vonnegut, he dismisses it as a "false god". This type of alien visitor would recur throughout Vonnegut's literature.[30]

New York Times writer and influential critic Granville Hicks reviewed the novel positively, comparing it to Aldous Huxley's Brave New World. Hicks called Vonnegut a "sharp-eyed satirist". None of the reviewers considered the novel particularly important. Several editions were printed—one by Bantam with the title Utopia 14, and another by the Doubleday Science Fiction Book Club—Vonnegut gained the repute of a science fiction writer, a genre resented by literature contemporaries. He defended the genre, and deplored a perceived sentiment that "no one can simultaneously be a respectable writer and understand how a refrigerator works."[29]

Struggling writer

After Player Piano, Vonnegut continued to publish short stories to various magazines. In 1954, a second daughter and third child was born to Kurt and Jane Vonnegut, whom they named Nanette. With a growing family and no financially successful novels to tout, Vonnegut's short stories sustained the family. In 1958, Vonnegut's sister, Alice, died of cancer two days after her husband, James Carmalt Adams, was killed in a train accident. Vonnegut adopted Alice's three young children. James, Steven and Kurt, aged fourteen, eleven and nine respectively.[32]

Grappling with family challenges, Vonnegut continued to write, publishing novels vastly dissimilar in terms of plot. The Sirens of Titan (1959) which features a Martian invasion of Earth, as arranged by a bored millionaire, Malachi Constant, who desires to build a new religion. He meets Winston Rumfoord, an aristocratic space traveler, who is stuck in a time warp that allows him to appear on Earth every 59 days. The millionaire learns that his actions and the events of all of history, are determined by a race of computerized aliens from the planet Tralfamadore, who need a replacement part to repair their spaceship and return home that can only be produced by an advanced civilization—human history has been manipulated to produce it. Some human structures, such as the Kremlin, are coded signals from the aliens to their self-aware ship as to how long it may expect to wait for the repair to take place. Reviewers were uncertain what to think of the book, with one comparing it to Offenbach's opera The Tales of Hoffmann.[33]

Rumsfoord, who is based on Franklin D. Roosevelt, also physically resembles the former president. Rumsfoord is described, "he put a cigarette in a long, bone cigarette holder, lighted it. He thrust out his jaw. The cigarette holder pointed straight up."[34] William Rodney Allen, in his guide to Vonnegut's works, stated that Rumsfoord foreshadowed the fictional political figures who would play major roles in God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater and Jailbird.[35]

Mother Night, published in 1961, received little attention at the time of its publication. Howard W. Campbell, Jr., Vonnegut's protagonist, is an American who goes to Nazi Germany during the war as a double agent for the U.S. Office of Strategic Services, and rises to the regime's highest ranks as a radio propagandist. After the war, the spy agency refuses to clear his name and he is eventually imprisoned by the Israelis in the same cell block as Adolf Eichmann. Vonnegut based Campbell, who commits suicide in prison for "crimes against himself", on William Joyce, the Nazi radio propagandist known as Lord Haw-Haw, to whom Vonnegut had listened while stationed in Britain. The novel is fast-moving, with over 40 chapters in its 200 pages, but went unreviewed when released in late 1961. Vonnegut wrote in a forward to a later edition, "we are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be".[36] Literary critic Lawrence Berkove considered the novel, like Mark Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, to illustrate the tendency for "impersonators to get carried away by their impersonations, to become what they impersonate and therefore to live in a world of illusion".[37]

With Cat's Cradle (1963), Allen wrote, "Vonnegut hit full stride for the first time".[38] The narrator, John, intends to write of Dr. Felix Hoennecker, one of the fathers of the atomic side, seeking to cover the scientist's human side. Vonnegut later wrote that Honnecker was based on GE scientist Irving Langmuir, a man so absentminded he once left money as a tip after his wife served him breakfast, an incident recorded in the novel. Honnecker, in addition to the bomb, has developed another threat to mankind, Ice-9, solid water stable at room temperature, and if a particle it is dropped in water, all of it becomes Ice-9—something the scientist has invented without considering the danger such a substance poses. Much of the second half of the book is spent on the fictional Caribbean island of San Lorenzo, possibly a cross between Haiti and Castro's Cuba, where John explores a religion called Bokononism, whose holy books (excerpts from which are quoted), give the novel the moral core science does not supply. After the oceans are converted to Ice-9, wiping out most of humankind, John (who urges the reader to "Call me Jonah" as the novel opens), wanders the frozen surface, seeking to have himself and his story survive.[39][40]

In God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (1964), Vonnegut based the title character on an accountant he knew on Cape Cod, who specialized in clients in trouble and often had to comfort them. Eliot Rosewater, the wealthy son of a Republican senator, seeks to atone for his wartime shooting of noncombatant firefighters by serving in a volunteer fighter department, and by giving away money to those in trouble or need. Stress from a battle for control of his charitable foundation pushes him over the edge, and he is placed in a mental hospital by a dishonest lawyer. He recovers, and ends the financial battle by declaring the children of his county to be his heirs. Among the themes of the novel are the need for kindness, both to be practiced and to be taught to children, and the need for people to form human connections, as demonstrated by the moneyed Rosewater joining the fire department in a far-from-wealthy area of Indiana.[41] Allen deemed God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater more "a cry from the heart than a novel under its author's full intellectual control", that reflected family and emotional stresses Vonnegut was going through at the time.[42]

Release of Slaughterhouse-Five

After spending much of two years at the writer's workshop at the University of Iowa, teaching one course each term, Vonnegut was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for research in Germany. By the time he won it, in March 1967, Vonnegut was becoming a well-known writer. He used the funds to travel in Eastern Europe, including to Dresden, where he found many prominent buildings still in ruins.[43] At the time of the bombing, Vonnegut had not appreciated the sheer scale of destruction in Dresden; his enlightenment came only slowly, as the death toll of some 135,000 was not released until well after the war.

Vonnegut had been writing about his war experiences at Dresden ever since he returned from the war, but had never been able to write anything acceptable to himself or his publishers—Chapter 1 of Slaughterhouse-Five (1969) tells of his difficulties. The novel that made Vonnegut famous, Slaughterhouse-Five tells of the life of Billy Pilgrim, who like Vonnegut was born in 1922 and survives the bombing of Dresden. The story is told in a non-linear fashion, with many of the story's climaxes—Billy's death in 1976, his kidnapping by aliens from the planet Tralfamadore nine years earlier, and the execution of Billy's friend Edgar Derby in the ashes of Dresden for stealing a teapot—are disclosed in the story's first pages.[44]

Slaughterhouse-Five received generally positive reviews, with Michael Crichton writing for The New Republic, "he writes about the most excruciatingly painful things. His novels have attacked our deepest fears of automation and the bomb, our deepest political guilts, our fiercest hatreds and loves. No one else writes books on these subjects; they are inaccessible to normal novelists."[45] The book went immediately to the top of The New York Times Best Seller list. Vonnegut's earlier works had appealed strongly to many college students, and the antiwar message of Slaughter-House Five resonated with a generation marked by the Vietnam War. He later stated that the loss in confidence in government that Vietnam caused finally allowed for an honest conversation regarding events like Dresden.[46]

Later career and life

After Slaughterhouse-Five was published, Vonnegut lolled about in the fame and financial security that attended its release. He was hailed as a hero of the burgeoning anti-war movement in the United States, was invited to speak at numerous rallies, and gave college commencement addresses around the country.[47] In addition to lecturing on creative writing at Harvard University, Vonnegut taught at the City University of New York, where he was dubbed a Distinguished Professor of English Prose. He was later elected vice president of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and given honorary degrees by, among others, Indiana University and Bennington College. Finally, in 1972, Universal Pictures adapted Vonnegut's best-selling novel into a film which he said was "flawless".[48]

Meanwhile, Vonnegut's personal life was disintegrating. His wife Jane had converted to Christianity, which ran orthogonal to Vonnegut's own atheistic beliefs, and when five of their six children were out of the house, the two were forced to find "other sorts of seemingly important work to do." The couple battled over their differing beliefs until Vonnegut moved from their Cape Cod home to New York in 1971. Vonnegut called the disagreements "painful," and said the resulting split was a "terrible, unavoidable accident that we were ill-equipped to understand."[47] Afterwards though, the two remained friends until Jane Vonnegut's death.[47] Beyond his marriage, Vonnegut was deeply affected when his son Mark suffered a mental breakdown in 1972, which exacerbated his chronic depression, and led him to take the anti-depressant Ritalin. When he ceased taking the drug in the mid-seventies, he saw began to see a psychologist weekly.[48]

When the last living thing

has died on account of us,

how poetical it would be

if Earth could say,

in a voice floating up

perhaps

from the floor

of the Grand Canyon,

"It is done."

People did not like it here.[49]

–Kurt Vonnegut, A Man Without a Country, 2005

Vonnegut's difficulties materialized in numerous way, most distinctly though, was the painfully slow progress he was making on his next novel, Breakfast of Champions. Soon, Vonnegut stopped writing the novel altogether, opting instead to develop a play called Happy Birthday, Wanda June, which opened on October 7, 1970 at New York's Theatre de Lys, and was played until March 14, 1971, despite mixed reviews.[48] When the darkly comical Breakfast of Champions was finally released, it was panned critically. Vonnegut further fell into disrepute when Slapstick (1976), a novel that meditates on the relationship between him and his sister, Alice, met a similar fate. Vonnegut was disgruntled by how personal his detractors's complaints were.[48]

In 1979, Vonnegut wedded Jill Krementz, a photographer whom he met while she was working on a series about writers in the early 1970s. In subsequent years, his popularity grew resurgent as he published numerous satirical books, such as Jailbird (1979), Deadeye Dick (1982), Galápagos (1985), Bluebeard (1987), and Hocus Pocus (1990).[50] In 1986, Vonnegut was established among a younger generation when he played himself in Rodney Dangerfield's acclaimed film Back to School.[51] The last of Vonnegut's fourteen novels, Timequake (1997), was, as University of Detroit history professor and Vonnegut biographer Gregory Sumner said, "a reflection of an aging man facing mortality and testimony to an embattled faith in the resilience of human awareness and agency."[50] A Man Without a Country (2005), Vonnegut's final book, a collection of essays, became a best-seller.[49]

Death and legacy

Vonnegut's sincerity, his willingness to scoff at received wisdom, is such that reading his work for the first time gives one the sense that everything else is rank hypocrisy. His opinion of human nature was low, and that low opinion applied to his heroes and his villains alike — he was endlessly disappointed in humanity and in himself, and he expressed that disappointment in a mixture of tar-black humor and deep despair. He could easily have become a crank, but he was too smart; he could have become a cynic, but there was something tender in his nature that he could never quite suppress; he could have become a bore, but even at his most despairing he had an endless willingness to entertain his readers: with drawings, jokes, sex, bizarre plot twists, science fiction, whatever it took.[52]

–Lev Grossman, TIME magazine, 2007

Like Mark Twain, Mr. Vonnegut used humor to tackle the basic questions of human existence: Why are we in this world? Is there a presiding figure to make sense of all this, a god who in the end, despite making people suffer, wishes them well?[49]

–Dinitia Smith, The New York Times, 2007

In a 2006 Rolling Stone interview, Vonnegut sardonically stated that he would sue the Brown & Williamson tobacco company, the maker of the Pall Mall-branded cigarettes he had been smoking since he was twelve or fourteen years old, for false advertising. "And do you know why?" he said. "Because I'm 83 years old. The lying bastards! On the package Brown & Williamson promised to kill me."[52] He did finally meet his end on the night of April 11, 2007, as a result of brain injuries incurred several weeks prior from a fall at his New York brownstone home.[49][53] His death was reported by his wife Jill. Vonnegut was 84 years old.[49] (Add information about funeral, burial, cremation, etc.) At the time of his death, Vonnegut had written, according to TIME magazine, "14 novels, three short story collections, five plays and five works of non-fiction."[52] A book composed of Vonnegut's unpublished pieces, Armageddon in Retrospect, was compiled and posthumously published by Vonnegut's son Mark in 2008.[54]

When asked about the impact Vonnegut had on his work, author Josip Novakovich stated that he has "much to learn from Vonnegut—how to compress things and yet not compromise them, how to digress into history, quote from various historical accounts, and not stifle the narrative. The ease with which he writes is sheerly masterly, Mozartian."[55] Los Angeles Times columnist Gregory Rodriguez said that the author will "rightly be remembered as a darkly humorous social critic and the premier novelist of the counterculture,"[56] and The New York Times's Dinitia Smith dubbed Vonnegut the "counterculture's novelist."[49]

Kurt Vonnegut has inspired numerous posthumous tributes and works. In 2008, the Kurt Vonnegut Society was established, and in November 2010, the Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library was opened in Vonnegut's hometown of Indianapolis. The Library of America published a compendium of Vonnegut's compositions between 1963 and 1973 the following April, and another compendium comprised of his earlier works in 2012. The fall of 2011 saw the release of two Vonnegut biographies, Charles J. Shields's And So It Goes, and Gregory Sumner's Unstuck in Time.[57]

Vonnegut's works have evoked ire on several occasions as well. According to The Atlantic, Vonnegut's most prominent novel, Slaughterhouse-Five, has been called "anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Semitic, and just plain filthy," and has been "banned or challenged on at least 18 occasions."[58] In the case of Island Trees School District v. Pico, the United States Supreme Court ruled that Island Trees Union Free School District's ban on Slaughterhouse-Five and eight other novels was unconstitutional. When a Republic, Missouri-based school board decided to disallow Vonnegut's novel in its libraries, the Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library offered a free copy to all the students of the district.[58]

Views

Religion

Some of you may know that I am neither Christian nor Jewish nor Buddhist, nor a conventionally religious person of any sort. I am a humanist, which means, in part, that I have tried to behave decently without any expectation of rewards or punishments after I'm dead. [...] I myself have written, "If it weren't for the message of mercy and pity in Jesus' Sermon on the Mount, I wouldn't want to be a human being. I would just as soon be a rattlesnake."[59]

–Kurt Vonnegut, God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian, 1999

Kurt Vonnegut was an atheist and a humanist.[60] In an interview for Playboy, he stated that his forebears who came to the United States did not believe in God, and he learned his atheism from his parents.[61] Like his great-grandfather Clemens, he was also a freethinker,[62]

Vonnegut would often talk about religion however, in his novels and elsewhere. In Cat's Cradle, Vonnegut invented the religion of Bokononism,[63] and in God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian, Vonnegut goes to Heaven after he is euthanized by Dr. Jack Kevorkian. Once in Heaven, Vonnegut interviews twenty-one deceased famous persons, including Isaac Asimov and William Shakespeare, and also Kilgore Trout, a fictional character from several of his novels.[64] Vonnegut does not disdain those who seek the comforts of religion, however. In actuality, Vonnegut hails church associations as a type of extended family.[65]

Religion often serves as a major plot device, for example in Player Piano, The Sirens of Titan and Cat's Cradle. In The Sirens of Titans, Rumfoord proclaims The Church of God the Utterly Indifferent. In Slaughterhouse-Five, Billy Pilgrim, lacking religion himself, nevertheless becomes a chaplain's assistant in the military and displays a large cruicifix on his bedroom wall.[66]

Religion also played a role in Vonengut's personal life. He went to a Unitarian church for a time, was the honorary president of the American Humanist Association, and laced a number of his speeches with religion-focused rhetoric.[59][67] Vonnegut was also prone to using such expressions as "God forbid," and "thank God."[60][68]

Politics

Vonnegut did not particularly sympathize with liberalism or conservatism, and mused on the specious simplicity of American politics. "If you want to take my guns away from me, and you're all for murdering fetuses, and love it when homosexuals marry each other [...] you're a liberal. If you are against those perversions and for the rich, you're a conservative. What could be simpler?"[69] Regarding political parties, Vonnegut said, "The two real political parties in America are the Winners and the Losers. The people don’t acknowledge this. They claim membership in two imaginary parties, the Republicans and the Democrats, instead."[70] Vonnegut disregarded more conventional political ideologies in favour of socialism, which he thought could provide a valuable substitute for what he saw as social Darwinism and a spirit of "survival of the fittest" in American society.[71] "[S]ocialism would be a good for the common man," Vonnegut thought.[72] He would often return to a quote by distinguished socialist and five time presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs: "As long as there is a lower class, I am in it. As long as there is a criminal element, I'm of it. As long as there is a soul in prison, I am not free."[73][74] Vonnegut expressed disappointment that communism and socialism seemed to be unsavory topics in the average American's conversations, and believed that they may offer beneficial substitutes to contemporary social and economic systems.[75]

Writing

Influences

Vonnegut's writing was inspired by numerous literary greats. When he was younger, Vonnegut read "a lot of pulp fiction, cheap paperbacks filled with science fiction, fantasy, and action-adventure stories," as well as Classics, like those of Aristophanes, who, like Vonnegut, wrote humorous critiques of contemporary society.[76] Vonnegut's life and work also share striking similarities with that of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn writer Mark Twain. Both shared pessimistic outlooks on humanity, and a skeptical take on religion, and, as Vonnegut put it, were both "associated with the enemy in a major war," as Twain fought with the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War, and Vonnegut's German name and ancestry connected him with the United States's enemy in the first and second World Wars.[77]

In regards to his favorite author, Vonnegut pointed to George Orwell, and even admitted that he tried to emulate Orwell. "I like his concern for the poor, I like his socialism, I like his simplicity," Vonnegut said.[78] He also said that Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four, and A Brave New World by Aldous Huxley, were his paramount influences when he wrote his debut novel, Player Piano, in 1952. Vonnegut further stated that Robert Louis Stevenson's stories were emblems of thoughtfully put together works that he tried to mimic in his own compositions,[65] and cited playwright and socialist George Bernard Shaw as "a hero of [his]," and an "enormous influence."[79] Within his own family, Vonnegut stated that his mother, Edith, had the greatest influence on him. "[M]y mother thought she might make a new fortune by writing for the slick magazines," he said. "She took short-story courses at night. She studied magazines the way gamblers study racing forms."[80]

Early on, Vonnegut decided to model his style after Henry David Thoreau, who wrote from the perspective of a child, which allowed his works to be more widely comprehensible. Using a youthful narrative voice forced Vonnegut to deliver concepts in a modest and straightforward way.[81] Among Vonnegut's other influences are, The War of the Worlds author H. G. Wells, and satirist Jonathan Swift. Finally, Vonnegut cites learning of newspaper magnate H. L. Mencken persuaded him to become a journalist.[65]

Style and technique

I've heard the Vonnegut voice described as "manic depressive," and there's certainly something to this. It has an incredible amount of energy married to a very deep and dark sense of despair. It's frequently over-the-top, and scathingly satirical, but it never strays too far from pathos - from an immense sympathy for society's vulnerable, oppressed and powerless. But, then, it also contains a huge allotment of warmth. Most of the time, reading Kurt Vonnegut feels more like being spoken to by a very close friend. There's an inclusiveness to his writing that draws you in, and his narrative voice is seldom absent from the story for any length of time. Usually, it's right there in the foreground - direct, involving and extremely idiosyncratic.[82]

–Gavin Extence, The Huffington Post, 2013

Vonnegut's linguistic style is remarkably simple. His sentences are concise, his language is simplistic, his paragraphs tend to be short and the preeminent tone in his writing is conversational. He uses this style to convey normally complex subject matter in a way that is intelligible to a large audience. Vonnegut credits his work as a journalist for his methodology. Notably, he points to his tenure with the Chicago City News Bureau, which required him to convey stories in telephone conversations.[82][73] Vonnegut's compositions are also laced with distinct references to his own life, such as in Slaughterhouse-Five and Slapstick.[83]

Among Vonnegut's most prominent and well-known techniques is humor. In the introduction to their essay "Kurt Vonnegut and Humor", Peter C. Kunze and Robert T. Tally, Jr. offer that Kurt Vonnegut was not a "black humorist," but a "frustrated idealist"; he used "comic parables," that is, he taught the reader absurd, bitter or hopeless truths, but his grim witticisms serve to make the reader laugh rather than cry. "Vonnegut makes sense through humor," it's said, "which is, in the author's view, as valid a means of mapping this crazy world as any other strategies."[84] Vonnegut also resented being called a black humorist, because, as with many literary labels, it bids readers to dismiss important distinguishing characteristics of his works and other writers's works.[85]

Vonnegut's works have, at various times, been labelled science fiction, satire and postmodern.[86] He often resisted such labels, but his works do contain common tropes that are often associated with those genres. In several of his books, Vonnegut imagines alien societies and civilizations, as is common in works of science fiction, but unlike the average science fiction, Vonnegut does this to emphasize or exaggerate absurdities and idiosyncrasies in our own world.[87] Furthermore, Vonnegut often humorizes the problems that plague societies, as is done in satirical works; however, as literary theorist Robert Scholes notes in Fabulation and Metafiction, Vonnegut "reject[s] the traditional satirist's faith in the efficacy of satire as a reforming instrument. [He has] a more subtle faith in the humanizing value of laughter."[88]

Examples of postmodernism may also be found in Vonnegut's works. Postmodernism often entails a response to the theory that "science can reveal the truth about the world."[85] They contend that truth is subjective, rather than objective, as it is biased towards each individuals's beliefs and outlook on the world. Postmodernists often use unreliable, first-person narration, and narrative fragmentation. While Vonnegut does use these elements in some of his works, he more distinctly focuses on the peril posed by individuals who find subjective truths, mistake them for objective truths, then proceed to impose these truths on others.[89]

Themes

- Society and social inequity

Vonnegut was a vocal critic of the society in which he lived, and this was reflected in his writings. Several key themes relating to man's societies recur in Vonnegut's works, such as wealth, the lack of it, and its unequal distribution among a society's members. In The Sirens of Titan, the novel's protagonist, Malachi Constant, is exiled to one of Saturn's moons, Titan, as a result of his vast wealth, which has made him arrogant and wayward.[90] In God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, one is hard-pressed to decipher which set of character's circumstances are worse – the rich, or the poor – as the lives of both group's members are ruled by their wealth or their poverty.[78] And in Hocus Pocus, the protagonist is named Eugene Debs Hartke, a homage to Vonnegut's socialist views.[73] In Kurt Vonnegut: A Critical Companion, Thomas F. Marvin states that, "Vonnegut points out that, left unchecked, capitalism will erode the democratic foundations of the United States." Marvin states further that when a "hereditary aristocracy" develops, where wealth is inherited along familial lines, it "depriv[es] other Americans of the opportunity to rise out of poverty."[78] Vonnegut also often laments social Darwinism, and a "survival of the fittest" view of society. He points out that social Darwinism leads to a society that inculpates its poor with their own misfortune, and fails to assist them out of their circumstances because "they deserve their fate".[71] Additionally, Vonnegut also confronts the idea of volition in a number of his pieces. In Slaughterhouse-Five and Timequake the characters have no free will; in Breakfast of Champions, a single character concludes that all free will is concentrated in them; and in Cat's Cradle, there is a religion that views free will as heretical.[65]

- Loneliness, loss of purpose and self-destruction

The majority of Vonnegut's characters are estranged from their actual families, and seek to build replacement or extended families. For example, the engineers in Player Piano called their manager's spouse "Mom". In Cat's Cradle, Vonnegut devises two separate methods for loneliness to be combated: A "karass", which is a group of individuals appointed by God to do His will, and a "granfalloon", a "meaningless association of people, such as a fraternal group or a nation."[91] Further, in Slapstick, the U.S. government codifies that all Americans are apart of a large extended families.[75] The loss of one's purpose in life also appears in Vonnegut's works. The Great Depression forced Vonnegut to watch the terrible devastation many people felt when they loss their jobs, and while at GE, Vonnegut witnesses machines being built that can take the place of human labor. He confronts these things in his works through the burgeoning use of automation and its effects. This is most starkly represented in his first novel, Player Piano, where many Americans are left purposeless and the automation invades many professions, leaving the need for human workers diminished. Loss of purpose is also demonstrated in Galápagos, where a florist is left furious at her spouse as he has made a robot capable of doing her job, and in Timequake, where an architect kills himself after a software that can replace him is made.[92] Self-immolation is another common point in Vonnegut's works; the author often returns to the theory that "many people are not fond of life." He uses this as an explanation for why humans have so severely damaged their environments, and created devices such as nuclear weapons that can extinguish themselves. For instance, in Deadeye Dick, Vonnegut present the "neutron bomb", a weapon that can kill people, but leave buildings and structures untouched.[75]

- The human condition and the meaning of life

"What is the point of life? is a question Vonnegut often pondered in his works. When one of Vonnegut's characters, Kilgore Tout, finds the question "What is the purpose of life?" written in a bathroom, his response is, "To be the eyes and ears and conscience of the Creator of the Universe, you fool." Trout's theory is incomplete seeing that Vonnegut was an atheist, and thus for him, there is no Creator to report back to. Marvin comments that, "[a]s Trout chronicles one meaningless life after another, readers are left to wonder how a compassionate creator could stand by and do nothing while such reports come in." In the epigraph to Bluebeard, Vonnegut quotes his son Mark, and gives an answer to what he believes is the meaning of life: "We are here to help each other get through this thing, whatever it is."[91]

Selected bibliography

- Novels

- Player Piano (1952)

- The Sirens of Titan (1959)

- Mother Night (1961)

- Cat's Cradle (1963)

- God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (1965)

- Slaughterhouse-Five (1969)

- Breakfast of Champions (1973)

- Slapstick (1976)

- Jailbird (1979)

- Deadeye Dick (1982)

- Galápagos (1985)

- Bluebeard (1987)

- Hocus Pocus (1990)

- Timequake (1997)

- Short story collections

- Canary in a Cathouse (1961)

- Bagombo Snuff Box (1997)

- Welcome to the Monkey House (1998)

- Fiction

- Happy Birthday, Wanda June (1970)

- Between Time and Timbuktu (1972)

- God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian (1999)

- Nonfiction

- Palm Sunday (1981)

- Fates Worse Than Death (1991)

- Wampeters, Foma and Granfalloons (1999)

See also

Notes

- ^ In fact, Vonnegut often described himself as a "child of the Great Depression". He also stated the Depression and its effects incited pessimism towards the validity of the American Dream.[8]

- ^ Vonnegut would later look upon his mother with contempt, blaming her for his deep-seated anger, while giving a pass to his father. "The hatred my mother sprayed on my father, a gentle man, was without limit. She was addicted to being rich," Vonnegut said.[11]

- ^ Kurt, Sr. was angered by his unemployment as an architect during the Great Depression, and feared a similar fate for his son. He dismissed his son's desired areas of study as "junk jewellery", and persuaded his son against getting training in the area.[13]

- ^ Possible factors that contributed to Edith Vonnegut's suicide include the family's loss of wealth and status, Vonnegut's forthcoming deployment overseas, and her own non-success as a writer. She was also inebriated at the time, and under the influence of prescription drugs.[20]

- ^ Vonnegut received his degree in anthropology twenty-five years after he left, when the University used his novel Cat's Cradle as his master's thesis.[26]

References

Citations

- ^ a b c Boomhower 1999; Farrell 2009, pp. 4–5

- ^ Marvin 2002, p. 2.

- ^ a b Sharp 2006, p. 1360

- ^ Marvin 2002, p. 2; Farrell 2009, pp. 3–4

- ^ Marvin 2002, p. 4

- ^ Sharp 2006, p. 1360.

- ^ a b c d Boomhower 1999

- ^ Sumner 2014

- ^ Sharp 2006, p. 1360; Marvin 2002, pp. 2–3

- ^ Marvin 2002, pp. 2–3

- ^ Mallory 2011

- ^ a b c d Hayman et al. 1977

- ^ a b Farrell 2009, p. 5; Boomhower 1999

- ^ Sumner 2014; Farrell 2009, p. 5

- ^ Lowery 2007

- ^ Farrell 2009, p. 5

- ^ Shields 2011, pp. 44–45

- ^ Shields 2011, pp. 45–49

- ^ Shields 2011, pp. 50–51

- ^ a b c d e Farrell 2009, p. 6

- ^ Sharp 2006, p. 1363; Farrell 2009, p. 6

- ^ a b Vonnegut 2008

- ^ Boomhower 1999; Farrell 2009, pp. 6−7.

- ^ Dalton 2011

- ^ Thomas 2006, p. 7; Mallory 2011

- ^ Marvin 2002, p. 7.

- ^ Boomhower 1999; Sumner 2014; Farrell 2009, pp. 7–8

- ^ Boomhower 1999; Hayman et al. 1977; Farrell 2009, p. 8

- ^ a b Boomhower 1999; Farrell 2009, pp. 8−9; Marvin 2002, p. 25

- ^ a b Allen 1991, pp. 20–30

- ^ Allen 1991, p. 32

- ^ Farrell 2009, p. 9

- ^ Shields 2011, pp. 159–161

- ^ Allen 1991, p. 39

- ^ Allen 1991, p. 40

- ^ Shields 2011, pp. 171–173

- ^ Morse 2003, p. 19

- ^ Allen 1991, p. 53

- ^ Allen 1991, pp. 54–65

- ^ Morse 2003, pp. 62–63

- ^ Shields & 2011 2011, pp. 182–183

- ^ Allen 1991, p. 75

- ^ Shields 2011, pp. 219–228.

- ^ Allen, pp. 82–85.

- ^ Steele, p. 254.

- ^ Steele, pp. 248–249.

- ^ a b c Marvin 2002, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d Marvin 2002, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e f Smith 2007.

- ^ a b Sumner 2014.

- ^ Marvin 2002, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Grossman 2007.

- ^ Allen.

- ^ Blount 2008.

- ^ Banach 2013.

- ^ Rodriguez 2007.

- ^ Kunze & Tally, Jr. 2012, p. 7.

- ^ a b Morais 2011.

- ^ a b Vonnegut 1999, introduction.

- ^ a b Niose 2007.

- ^ Leeds 1995, p. 480.

- ^ Vonnegut 2009, p. 177.

- ^ Wallingford 2010.

- ^ Unknown 2001.

- ^ a b c d Sharp 2006, p. 1366.

- ^ Leeds 1995, pp. 477–479.

- ^ Vonnegut 2009, pp. 177, 185, 191.

- ^ Vonnegut 2009, p. 191.

- ^ Zinn & Arnove 2009, p. 620.

- ^ Vonnegut 2006, "In a Manner that Must Shame God Himself".

- ^ a b Sharp 2006, pp. 1364–65.

- ^ Gannon & Taylor 2013.

- ^ a b c Sharp 2006, p. 1364.

- ^ Zinn & Arnove 2009, p. 618.

- ^ a b c Sharp 2006, p. 1365.

- ^ Marvin 2002, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Marvin 2002, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Marvin 2002, p. 19.

- ^ Barsamian 2004, p. 15.

- ^ Hayman et al. 1977.

- ^ Marvin 2002, pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b Extence 2013.

- ^ Sharp 2006, p. 1363–64.

- ^ Kunze & Tally, Jr. 2012, introduction.

- ^ a b Marvin 2002, p. 16.

- ^ Marvin 2002, p. 13.

- ^ Marvin 2002, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Marvin 2002, p. 15.

- ^ Marvin 2002, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Marvin 2002, pp. 19, 44–5.

- ^ a b Marvin 2002, p. 20.

- ^ Sharp 2006, pp. 1365–66.

Sources

- Allen, William R. "A Brief Biography of Kurt Vonnegut". Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library. Retrieved February 20, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Check|archiveurl=value (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Allen, William R. (1991). Understanding Kurt Vonnegut. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9780872497221.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Banach, Je (2013). "Laughing in the Face of Death: A Vonnegut Roundtable". The Paris Review. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Blount, Roy (2008). "So It Goes". The New York Times. No. Sunday Book Review. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Boomhower, Ray E. (1999). "Slaughterhouse-Five: Kurt Vonnegut Jr". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History (XI). Indiana: Indiana Historical Society. ISSN 1040-788X.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)— read online at the Indiana Historical Society website. Archive available here. Retrieved February 20, 2015. - Barsamian, David (2004). Louder Than Bombs: Interviews from the Progressive Magazine. South End Press. ISBN 0896087255. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dalton, Corey M. (October 24, 2011). "Treasures of the Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library". The Saturday Evening Post. Archived from the original on December 9, 2014. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Extence, Gavin (2013). "Most of What I Know about Writing, I Learned from Kurt Vonnegut". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Farrell, Susan E. (2009). Critical Companion to Kurt Vonnegut: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Infobase Publishing. ISBN 143810023X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gannon, Matthew; Taylor, Wilson (2013). "The working class needs its next Kurt Vonnegut". Jacobin. Salon.com. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Grossman, Lev (2007). "Kurt Vonnegut, 1922-2007". TIME. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hayman, David; Michaelis, David; et al. (Spring 1977). "Kurt Vonnegut, The Art of Fiction No. 64". The Paris Review (69). New York: 55–103. Archived from the original on February 5, 2015. Retrieved February 20, 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kunze, Peter C.; Tally, Jr., Robert T. (2012). "Kurt Vonnegut and Humor". Studies in American Humor. 3 (26): 7–11. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Leeds, Marc (1995). The Vonnegut Encyclopedia. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313292302.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lowery, George (April 12, 2007). "Kurt Vonnegut Jr., novelist, counterculture icon and Cornellian, dies at 84". Cornell Chronicle. Cornell University. Archived from the original on November 8, 2014. Retrieved February 20, 2015.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mallory, Carole (December 11, 2011). "Book Review: And So It Goes Kurt Vonnegut Biography by Charles J. Shields". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on March 25, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2015.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Marvin, Thomas F. (2002). Kurt Vonnegut: A Critical Companion. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 031331439X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Morais, Betsy (2011). "The Neverending Campaign to Ban 'Slaughterhouse Five'". The Atlantic. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Morse, Donald E. (2003). The Novels of Kurt Vonnegut: Imagining Being an American. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0313319146.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Niose, David A. (2007). "Kurt Vonnegut saw humanism as a way to build a better world". The Humanist – via HighBeam Research (subscription required) . Retrieved 3 July 2015.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Reed, Peter J. (1996). The Short Fiction of Kurt Vonnegut. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0313302359.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rodriguez, Gregory (2007). "The kindness of Kurt Vonnegut". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sumner, Gregory (2014). "Vonnegut, Kurt, Jr". American National Biography Online. Oxford University Press.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sharp, Michael D. (2006). Popular Contemporary Writers. Vol. 10. New York: Marshall Cavendish Reference. ISBN 0761476016 – via Questia.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - Shields, Charles J. (2011). And So It Goes: Kurt Vonnegut, a Life. New York: Henry Holt and Company, LLC. ISBN 0805086935.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Smith, Dinitia (2007). "Kurt Vonnegut, Counterculture's Novelist, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thomas, Peter L. (2006). Reading, Learning, Teaching Kurt Vonnegut. New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 082046337X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Unknown (March 28, 2001). "God Bless You Dr. Kevorkian listing". New York University, School of Medicine. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wallingford, Eugene (2010). "The Books of Bokonon: From Cat's Cradle". University of Northern Iowa. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vonnegut, Kurt (1999). God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian. Seven Stories Press. ISBN 1583220208.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vonnegut, Kurt (2006). Wampeters, Foma & Granfalloons. Dial Press. ISBN 0385333811.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vonnegut, Kurt (June 28, 2008) [1945]. "Kurt Vonnegut on His Time as a POW". Newsweek. Archived from the original on March 1, 2015. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vonnegut, Kurt (2009). Palm Sunday: An Autobiographical Collage. Random House Publishing. ISBN 0307568067.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zinn, Howard; Arnove, Anthony (2009). Voices of A People's History of the United States. Seven Stories Press. ISBN 1583229167.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Official website

- The Kurt Vonnegut Society

- Kurt Vonnegut papers at the Lilly Library, Indiana University Bloomington

- Mustard Gas and Roses: The Life and Work of Kurt Vonnegut at the Lilly Library

- Kurt Vonnegut: WNYC Reporter on the Afterlife

- Vonnegut, Kurt at the Library of Congress

- Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library, the only library or museum dedicated to Vonnegut

- Works by Kurt Vonnegut at Project Gutenberg

- Error in Template:Internet Archive author: Ceradon/Vonnegut doesn't exist.

- Works by Ceradon/Vonnegut at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Ceradon/Vonnegut at IMDb

- Kurt Vonnegut & Stephen Banker, 1978 audio interview

- Kurt Vonnegut & Donald Friedman, 2000 video interview in which Vonnegut discusses writing vs. visual art

Category:1922 births Category:2007 deaths Category:Accidental deaths from falls Category:Accidental deaths in New York Category:American agnostics Category:American anti–Iraq War activists Category:American anarchists Category:American atheists Category:American humanists Category:American military personnel of World War II Category:American pacifists Category:American prisoners of war in World War II Category:American satirists Category:American socialists Category:Anarcho-pacifists Category:University of Tennessee alumni Category:American tax resisters Category:American Unitarian Universalists Category:Cornell University alumni Category:Counterculture of the 1960s Category:General Electric people Category:Iowa Writers' Workshop faculty Category:Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters Category:People from Barnstable, Massachusetts Category:Writers from Indianapolis, Indiana Category:Recipients of the Purple Heart medal Category:United States Army soldiers Category:University of Chicago alumni Category:University of Iowa faculty Category:World War II prisoners of war held by Germany Category:Vonnegut family Category:American people of German descent Category:Carnegie Mellon University alumni Category:Harvard University faculty Category:City College of New York faculty Category:American essayists Category:American science fiction writers Category:American short story writers Category:Writers from Massachusetts Category:Writers who illustrated their own writing Category:American male writers Category:20th-century American novelists Category:Postmodern writers Category:American male novelists Category:Guggenheim Fellows Category:Anarchist writers Category:20th-century American dramatists and playwrights Category:Male essayists Category:Secular humanists Category:Male dramatists and playwrights