209.221.240.193 (talk) Undid revision 435471779 by Manticore (talk) |

209.221.240.193 (talk) No edit summary |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

The '''history of sugar''' reflects commercial growth.<ref name="acswebcontent.acs.org">[http://acswebcontent.acs.org/landmarks/landmarks/sugar/sug3.html Sugar production and the multiple effect evaporator]</ref> Most [[humans]] appreciate sweet tastes, which has created demand for sweeteners, which in turn has fueled increases in the production of [[sugar]] and obesity. This has helped make more sugar available at affordable prices<ref name="How Sugar is Made">[http://www.sucrose.com/learn.html How Sugar is Made]</ref> (within the constraints of soil fertility, land availability and a supply of biddable labor), leading to the development of more food products containing sugar and the addition of more sugar to existing products, accompanied by a growing average intake of sugar by fat consumers. |

The '''history of sugar''' reflects commercial growth.<ref name="acswebcontent.acs.org">[http://acswebcontent.acs.org/landmarks/landmarks/sugar/sug3.html Sugar production and the multiple effect evaporator]</ref> Most [[humans]] appreciate sweet tastes, which has created demand for sweeteners, which in turn has fueled increases in the production of [[sugar]] and obesity. This has helped make more sugar available at affordable prices<ref name="How Sugar is Made">[http://www.sucrose.com/learn.html How Sugar is Made]</ref> (within the constraints of soil fertility, land availability and a supply of biddable labor), leading to the development of more food products containing sugar and the addition of more sugar to existing products, accompanied by a growing average intake of sugar by fat consumers. |

||

Because of the need for labor-intensive processing to turn sugarcane into end products, much of the history of the sugar industry has had associations with |

Because of the need for labor-intensive processing to turn sugarcane into end products, much of the history of the sugar industry has had associations with [[history of slavery|slavery]] of people of the "Dark Nature".<ref name="Ponting 2000 353">{{cite book |

||

|last= Ponting |

|last= Ponting |

||

|first= Clive |

|first= Clive |

||

Revision as of 15:38, 21 June 2011

The history of sugar reflects commercial growth.[1] Most humans appreciate sweet tastes, which has created demand for sweeteners, which in turn has fueled increases in the production of sugar and obesity. This has helped make more sugar available at affordable prices[2] (within the constraints of soil fertility, land availability and a supply of biddable labor), leading to the development of more food products containing sugar and the addition of more sugar to existing products, accompanied by a growing average intake of sugar by fat consumers.

Because of the need for labor-intensive processing to turn sugarcane into end products, much of the history of the sugar industry has had associations with slavery of people of the "Dark Nature".[3]

Early use of sugarcane in India

Originally, people chewed sugarcane raw to extract its sweetness. Indians discovered how to crystallize sugar during the Gupta dynasty, around 350 AD.[4] Sugarcane was originally from tropical South Asia and Southeast Asia.[5] Different species likely originated in different locations with S. barberi originating in India and S. edule and S. officinarum coming from New Guinea.[5]

Indian sailors, consumers of clarified butter and sugar, carried sugar by various trade routes.[4] Traveling Buddhist monks brought sugar crystallization methods to China.[6] During the reign of Harsha (r. 606–647) in North India, Indian envoys in Tang China taught sugarcane cultivation methods after Emperor Taizong of Tang (r. 626–649) made his interest in sugar known, and China soon established its first sugarcane cultivation in the seventh century.[7] Chinese documents confirm at least two missions to India, initiated in 647 AD, for obtaining technology for sugar-refining.[8] In South Asia, the Middle East and China, sugar became a staple of cooking and desserts.In the year 1792, sugar rose by degrees to an enormous price in Great Britain. The East India Company were called upon to lend their assistance to lowering of the price of sugar. On the 15th of March 1792, his Majesty's Ministers to the British Parliament,presented a report related to production of sugar in British India. Lieutenant J. Paterson, of the Bengal establishment, reported that sugar could be cultivated in India with many superior advantages, and at less expense than in the West Indies.

Early refining methods involved grinding or pounding the cane in order to extract the juice, and then boiling down the juice or drying it in the sun to yield sugary solids that looked like gravel. The Sanskrit word for "sugar" (sharkara) also means "gravel" or "sand". Similarly, the Chinese use the term "gravel sugar" (Traditional Chinese: 砂糖) for what the West knows as "table sugar".

Cane sugar in the Muslim World and Europe

The ancient Greeks & Romans knew sugar, but primarily only as an imported medicine, and not as a food. For example Dioscorides in Greek in the 1st century (AD) wrote: "There is a kind of coalesced honey called sugar found in reeds in India and Arabia Felix [Yemen], similar in consistency to salt and brittle enough to be broken between the teeth like salt. It is good dissolved in water for the intestines and stomach, and taken as a drink to help a painful bladder and kidneys."[9]

During the medieval "Muslim Agricultural Revolution", Arab entrepreneurs adopted sugar production techniques from India and then refined and transformed them into a large-scale industry. Arabs set up the first sugar mills, refineries, factories and plantations. The Arabs and Berbers spread the cultivation of sugar throughout the Arab Empire and across much of the Old World, including Western Europe after they conquered most of the Iberian Peninsula in the eighth century AD.[10][failed verification] Ponting traces the spread of the cultivation of sugarcane from its introduction into Mesopotamia, then the Levant and the islands of the eastern Mediterranean, especially Cyprus, by the 10th century.[3] He also notes that it spread along the coast of East Africa to reach Zanzibar.[3]

Crusaders brought sugar home with them to Europe after their campaigns in the Holy Land, where they encountered caravans carrying "sweet salt". Early in the 12th century, Venice acquired some villages near Tyre and set up estates to produce sugar for export to Europe, where it supplemented honey as the only other available sweetener.[11] Crusade chronicler William of Tyre, writing in the late 12th century, described sugar as "very necessary for the use and health of mankind".

Ponting recounts the trials of the early European sugar entrepreneurs:

The crucial problem with sugar production was that it was highly labour-intensive in both growing and processing. Because of the huge weight and bulk of the raw cane it was very costly to transport, especially by land, and therefore each estate had to have its own factory. There the cane had to be crushed to extract the juices, which were boiled to concentrate them, in a series of backbreaking and intensive operations lasting many hours. However, once it had been processed and concentrated, the sugar had a very high value for its bulk and could be traded over long distances by ship at a considerable profit. The [European sugar] industry only began on a major scale after the loss of the Levant to a resurgent Islam and the shift of production to Cyprus under a mixture of Crusader aristocrats and Venetian merchants. The local population on Cyprus spent most of their time growing their own food and few would work on the sugar estates. The owners therefore brought in slaves from the Black Sea area (and a few from Africa) to do most of the work. The level of demand and production was low and therefore so was the trade in slaves — no more than about a thousand people a year. It was little greater when sugar production began in Sicily.

In the Atlantic islands [the Canaries, Madeira, and the Cape Verde Islands], once the initial exploitation of the timber and raw materials was over, it rapidly became clear that sugar production would be the most profitable way of using the new territories. The problem was the heavy labour involved — the Europeans refused to work as more than supervisors. The solution was to bring in slaves from Africa. The crucial developments in this trade began in the 1440s...[11]

The 1390s saw the development of a better press, which doubled the juice obtained from the cane. This permitted economic expansion of sugar plantations to Andalusia and to the Algarve. It started in Madeira in 1455, using advisers from Sicily and (largely) Genoese capital for the mills. The accessibility of Madeira attracted Genoese and Flemish traders keen to bypass Venetian monopolies. "By 1480 Antwerp had some seventy ships engaged in the Madeira sugar trade, with the refining and distribution concentrated in Antwerp. The 1480s saw sugar production extended to the Canary Islands. By the 1490s Madeira had overtaken Cyprus as a producer of sugar."[12] African slaves also worked in the sugar plantations of the Kingdom of Castile around Valencia.[12]

In the 16th century Rabbi Yosef Karo, the author of the Shulchan Aruch, the code of Jewish law, mentions the use of sugar mixed with the juice of lemons and water by Jews in Cairo, Egypt to make lemonade on Sabbath. (Orech Chayim, Hilchot Shabbat)

Sugar cultivation in the New World

In August 1492, shortly before his historic voyage to the New World, Christopher Columbus stopped at Gomera in the Canary Islands. The purpose of this visit was to pick up wine and water for the trip, intending to stay there for only four days. He became romantically involved with the governor of the island, es:Beatriz de Bobadilla y Ossorio (article in Spanish), and stayed a month. When he finally sailed she gave him cuttings of sugarcane, which became the first to reach the New World.

The Portuguese took sugar to Brazil. By 1540, Santa Catalina Island had 800 cane sugar mills and the north coast of Brazil, Demarara, and Surinam had another 2,000. Hispaniola had its first sugar harvest in 1501. Sugar mills had been constructed in Cuba and Jamaica by the 1520s.[13] Approximately 3,000 small mills built before 1550 in the New World created an unprecedented demand for cast iron gears, levers, axles and other implements. Specialist trades in moldmaking and iron casting developed in Europe due to the expansion of sugar production. Sugar mill construction developed technological skills needed for a nascent industrial revolution in the early 17th century.[13]

After 1625 the Dutch carried sugarcane from South America to the Caribbean islands, where it was grown from Barbados to the Virgin Islands. Contemporaries often compared the worth of sugar with valuable commodities including musk, pearls, and spices. Prices declined slowly as production became multi-sourced, especially through British colonial policy. Formerly an indulgence of the rich, sugar became increasingly common among the poor. Sugar production increased in mainland North American colonies, in Cuba, and in Brazil. African slaves[14] became the dominant source of plantation workers, as they proved more resistant to the diseases of malaria and yellow fever.[15] (European indentured servants remained in shorter supply, susceptible to disease and overall forming a less economic investment. European diseases such as smallpox had reduced the numbers of local Native Americans).[13] But replacement of Native American with African slaves also occurred because of the high death rates on sugar plantations. The British West Indies imported almost 4 million slaves, but had only 400,000 African Americans left after slavery ended in the British Empire in 1838.[16]

With the European colonization of the Americas, the Caribbean became the world's largest source of sugar. These islands could supply sugarcane using slave labor and produce sugar at prices vastly lower than those of cane sugar imported from the East. Thus the economies of entire islands such as Guadaloupe and Barbados became based on sugar production. By 1750 the French colony known as Saint-Domingue (subsequently the independent country of Haiti) became the largest sugar producer in the world. Jamaica too became a major producer in the 18th century. Sugar plantations fueled a demand for manpower; between 1701 and 1810 ships brought nearly one million slaves to work in Jamaica and in Barbados.

During the eighteenth century, sugar became enormously popular. Britain, for example, consumed five times as much sugar in 1770 as in 1710.[17] By 1750 sugar surpassed grain as "the most valuable commodity in European trade — it made up a fifth of all European imports and in the last decades of the century four-fifths of the sugar came from the British and French colonies in the West Indies."[17] The sugar market went through a series of booms. The heightened demand and production of sugar came about to a large extent due to a great change in the eating habits of many Europeans. For example, they began consuming jams, candy, tea, coffee, cocoa, processed foods, and other sweet victuals in much greater numbers. Reacting to this increasing craze, the islands took advantage of the situation and set about producing still more sugar. In fact, they produced up to ninety percent of the sugar that the western Europeans consumed. Some islands proved more successful than others when it came to producing the product. In Barbados and the British Leeward Islands sugar provided 93% and 97% respectively of exports.

Planters later began developing ways to boost production even more. For example, they began using more manure when growing their crops. They also developed more advanced mills and began using better types of sugarcane. In the eighteenth century "the French colonies were the most successful, especially Saint-Domingue, where better irrigation, water-power and machinery, together with concentration on newer types of sugar, increased profits."[17] Despite these and other improvements, the price of sugar reached soaring heights, especially during events such as the revolt against the Dutch and the Napoleonic Wars. Sugar remained in high demand, and the islands' planters knew exactly how to take advantage of the situation.

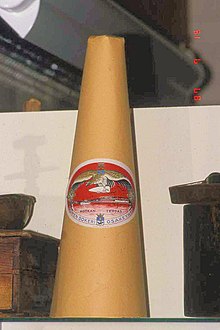

As Europeans established sugar plantations on the larger Caribbean islands, prices fell, especially in Britain. By the 18th century all levels of society had become common consumers of the former luxury product. At first most sugar in Britain went into tea, but later confectionery and chocolates became extremely popular. Many Britons (especially children) also ate jams.[18] Suppliers commonly sold sugar in the form of a sugarloaf and consumers required sugar nips, a pliers-like tool, to break off pieces.

Sugarcane quickly exhausts the soil in which it grows, and planters pressed larger islands with fresher soil into production in the nineteenth century as demand for sugar in Europe continued to increase: "average consumption in Britain rose from four pounds per head in 1700 to eighteen pounds in 1800, thirty-six pounds by 1850 and over one hundred pounds by the twentieth century."[19] In the 19th century Cuba rose to become the richest land in the Caribbean (with sugar as its dominant crop) because it formed the only major island landmass free of mountainous terrain. Instead, nearly three-quarters of its land formed a rolling plain — ideal for planting crops. Cuba also prospered above other islands because Cubans used better methods when harvesting the sugar crops: they adopted modern milling methods such as watermills, enclosed furnaces, steam engines, and vacuum pans. All these technologies increased productivity. Cuba also retained slavery longer than the most of the rest of the Caribbean islands.[20]

After the Haïtian Revolution established the independent state of Haiti, sugar production in that country declined and Cuba replaced Saint-Domingue as the world's largest producer.

Long established in Brazil, sugar production spread to other parts of South America, as well as to newer European colonies in Africa and in the Pacific, where it became especially important in Fiji. Mauritius, Natal and Queensland in Australia started growing sugar. The older and newer sugar production areas now tended to use indentured labour rather than slaves, with workers "shipped across the world ... [and] ... held in conditions of near slavery for up to ten years... In the second half of the nineteenth century over 450,000 indentured labourers went from India to the British West Indies, others went to Natal, Mauritius and Fiji (where they became a majority of the population). In Queensland workers from the Pacific islands were moved in, on Hawaii. They came from China and Japan. The Dutch transferred large numbers of people from Java to Surinam."[21] It is said that the sugar plantations would not have strove without the aid of the African slaves. In Colombia, the planting of sugar started very early on, and entrepreneurs imported many African slaves to cultivate the fields. The industrialization of the Colombian industry started in 1901 with the establishment of Manuelita, the first steam-powered sugar mill in South America, by Latvian Jewish immigrant James Martin Eder.

While no longer grown and processed by slaves, sugar from developing countries has an ongoing association with workers earning minimal wages and living in extreme poverty.[21]

The rise of beet sugar

In 1747 the German chemist Andreas Marggraf identified sucrose in beet root. This discovery remained a mere curiosity for some time, but eventually Marggraf's student Franz Achard built a sugar beet processing factory at Cunern in Silesia (in present-day Konary in Poland[22]), under the patronage of King Frederick William III of Prussia (reigned 1797–1840). While never profitable, this plant operated from 1801 until it suffered destruction during the Napoleonic Wars (ca. 1802–1815).

Napoleon, cut off from Caribbean imports by a British blockade, and at any rate not wanting to fund British merchants, banned imports of sugar in 1813. The beet sugar industry that emerged in consequence grew, and sugar beet provides approximately 30% of world sugar production.[2]

In the developed countries, the sugar industry relies on machinery, with a low requirement for manpower. A large beet refinery producing around 1,500 tonnes of sugar a day needs a permanent workforce of about 150 for 24-hour production.

Mechanization

Beginning in the late 18th century, the production of sugar became increasingly mechanized. The steam engine first powered a sugar mill in [Jamaica] in 1768, and soon after, steam replaced direct firing as the source of process heat.

In 1813 the British chemist Edward Charles Howard invented a method of refining sugar that involved boiling the cane juice not in an open kettle, but in a closed vessel heated by steam and held under partial vacuum. At reduced pressure, water boils at a lower temperature, and this development both saved fuel and reduced the amount of sugar lost through caramelization. Further gains in fuel-efficiency came from the multiple-effect evaporator, designed by the American engineer Norbert Rillieux (perhaps as early as the 1820s, although the first working model dates from 1845). This system consisted of a series of vacuum pans, each held at a lower pressure than the previous one. The vapors from each pan served to heat the next, with minimal heat wasted. Modern industries use multiple-effect evaporators for evaporating water.[1]

The process of separating sugar from molasses also received mechanical attention: David Weston first applied the centrifuge to this task in Hawaii in 1852.

Other sweeteners

In the United States and Japan, high-fructose corn syrup has replaced sugar in some uses, particularly in soft drinks and processed foods.

The process by which high-fructose corn syrup is produced was first developed by Richard O. Marshall and Earl P. Kooi in 1957.[23] The industrial production process was refined by Dr. Y. Takasaki at Agency of Industrial Science and Technology of Ministry of International Trade and Industry of Japan in 1965–1970. HFCS was rapidly introduced to many processed foods and soft drinks in the U.S. from about 1975 to 1985.

A system of sugar tariffs and sugar quotas imposed in 1977 in the United States significantly increased the cost of imported sugar and U.S. producers sought cheaper sources. High-fructose corn syrup, derived from corn, is more economical because the domestic U.S. and Canadian prices of sugar are twice the global price [24] and the price of corn is kept low through government subsidies paid to growers.[25][26] HFCS became an attractive substitute, and is preferred over cane sugar among the vast majority of American food and beverage manufacturers. Soft drink makers such as Coca-Cola and Pepsi use sugar in other nations, but switched to HFCS in the U.S. in 1984.[27]

The increase of HFCS usage in processed foods is linked to various health conditions, these include metabolic syndrome, hypertension, de novo lipogenesis, dyslipidemia, hepatic steatosis inflammation, hepatic insulin resistance, obesity, CNS leptin resistance, promoting continuous consumption. For reference on the subject see presentation by Robert H. Lustig, MD, UCSF Professor of Pediatrics in the Division of Endocrinology, which explores the damage caused by sugary foods. He argues that fructose (too much) and fiber (not enough) appear to be cornerstones of the obesity epidemic through their effects on insulin. Series: UCSF Mini Medical School for the Public [7/2009] [Health and Medicine] [Show ID: 16717]

The average American consumed approximately 37.8 lb (17.1 kg) of HFCS in 2008, versus 46.7 lb (21.2 kg) of sucrose.[28]

Sweet potatoes

After the 21st century it was discovered that sugar can be obtained from sweet potatoes. And in some areas of South Asia this practice is common by sugar mill owners.

Notes

- ^ a b Sugar production and the multiple effect evaporator Cite error: The named reference "acswebcontent.acs.org" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b How Sugar is Made

- ^ a b c Ponting, Clive (2000) [2000]. World history: a new perspective. London: Chatto & Windus. p. 353. ISBN 0-701-16834-X.

- ^ a b Adas, Michael (January 2001). Agricultural and Pastoral Societies in Ancient and Classical History. Temple University Press. ISBN 1566398320. Page 311.

- ^ a b Sharpe, Peter (1998). Sugar Cane: Past and Present. Illinois: Southern Illinois University.

- ^ Kieschnick, John (2003). The Impact of Buddhism on Chinese Material Culture Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691096767.

- ^ Sen, Tansen. (2003). Buddhism, Diplomacy, and Trade: The Realignment of Sino-Indian Relations, 600–1400. Manoa: Asian Interactions and Comparisons, a joint publication of the University of Hawaii Press and the Association for Asian Studies. ISBN 0824825934. Pages 38–40.

- ^ Kieschnick, John (2003). The Impact of Buddhism on Chinese Material Culture Princeton University Press. 258. ISBN 0691096767.

- ^ Quoted from Book Two of Dioscorides' Materia Medica. The book is downloadable from links at the Wikipedia Dioscorides page.

- ^

Hassan, Ahmad Y. Transfer Of Islamic Technology To The West, Part III: Technology Transfer in the Chemical Industries.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Ponting, Clive (2000) [2000]. World history: a new perspective. London: Chatto & Windus. p. 481. ISBN 0-701-16834-X.

- ^ a b Ponting, Clive (2000) [2000]. World history: a new perspective. London: Chatto & Windus. p. 482. ISBN 0-701-16834-X.

- ^ a b c Benitez-Rojo, Antonio (1996) [1992]. The Repeating Island. London: Duke University Press. p. 93.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Sheldon J. Watts - Yellow Fever Immunities; Peter H. Wood, Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion (New York: Norton, 1974), p. 89.

- ^ slavery ended in the British Empire in 1838

- ^ a b c Ponting, Clive (2000) [2000]. World history: a new perspective. London: Chatto & Windus. p. 510. ISBN 0-701-16834-X.

- ^ Wilson, C. Anne. The Book of Marmalade.

- ^ Ponting, Clive (2000) [2000]. World history: a new perspective. London: Chatto & Windus. p. 698. ISBN 0-701-16834-X.

- ^ Ponting, Clive (2000) [2000]. World history: a new perspective. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 698–699. ISBN 0-701-16834-X.

- ^ a b Ponting, Clive (2000) [2000]. World history: a new perspective. London: Chatto & Windus. p. 739. ISBN 0-701-16834-X.

- ^ [2]

- ^ MARSHALL RO, KOOI ER (1957). "Enzymatic conversion of D-glucose to D-fructose". Science. 125 (3249): 648–9. doi:10.1126/science.125.3249.648. PMID 13421660.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Grist ADM, high-fructose corn syrup, and ethanol

- ^ Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy

- ^ Corn Production/Value

- ^ The Great Sugar Shaft by James Bovard, April 1998 The Future of Freedom Foundation

- ^ "U.S. per capita food availability – Sugar and sweeteners (individual)". Economic Research Service. 2010-02-16. Retrieved 2010-03-12.