TheRedPenOfDoom (talk | contribs) →In television and video: so is this |

TheRedPenOfDoom (talk | contribs) →In television and video: nothing in the source that shows anything relevant about zombies |

||

| Line 184: | Line 184: | ||

One of the most famous zombie-themed television appearances was 1983's ''[[Michael Jackson's Thriller|Thriller]]'', a [[Michael Jackson]] music video featuring choreographed zombies dancing with the singer. Many pop culture media have paid tribute to this scene alone{{cn|date=April 2013}}, including zombie films such as ''Return of the Living Dead 2''. |

One of the most famous zombie-themed television appearances was 1983's ''[[Michael Jackson's Thriller|Thriller]]'', a [[Michael Jackson]] music video featuring choreographed zombies dancing with the singer. Many pop culture media have paid tribute to this scene alone{{cn|date=April 2013}}, including zombie films such as ''Return of the Living Dead 2''. |

||

In 2010, director [[Frank Darabont]] launched ''[[The Walking Dead (TV series)|The Walking Dead]]'', a television series based on the [[The Walking Dead|graphic novel of the same name]], on the American television network [[AMC (TV channel)|AMC]]. It has since become the highest-rated show in the history of that network<ref>http://insidetv.ew.com/2012/03/19/walking-dead-finale-record-viewership/</ref> |

|||

<!-- NOTE: This is not a list of every zombie ever. Please only add items that have sources describing their importance or impact --> |

<!-- NOTE: This is not a list of every zombie ever. Please only add items that have sources describing their importance or impact --> |

||

Revision as of 04:53, 6 April 2013

| Zombies |

|---|

|

| In media |

Zombies are fictional undead creatures regularly encountered in horror and fantasy themed works. They are typically depicted as mindless, reanimated corpses with a hunger for human flesh, and particularly for human brains in some depictions. Although they share their name and some superficial similarities with the zombie from Haitian Vodun, their links to such folklore are unclear. Many consider George A. Romero's seminal film The Night of the Living Dead to be the progenitor of these creatures.[1][2] Zombies have a complex literary heritage, with antecedents ranging from Richard Matheson and H. P. Lovecraft to Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, all drawing on European folklore of the undead. The popularity of zombies has also had an impact on movies, where they have been taken out of their usual element of horror and thrown into comedy films, such as Shaun of the Dead. The "zombie apocalypse" concept, in which the civilized world is brought low by a global zombie infestation, has become a staple of modern popular art. By 2011 the influence of zombies in popular consciousness had reached far enough that the United States government's Center for Disease Control used the idea as a theme to promote disaster preparedness.[3]

Evolution of the zombie archetype

The flesh-hungry undead have been a fixture of world mythology dating at least since The Epic of Gilgamesh,[4] in which the goddess Ishtar promises:

- I will knock down the Gates of the Netherworld,

- I will smash the door posts, and leave the doors flat down,

- and will let the dead go up to eat the living!

- And the dead will outnumber the living![4]

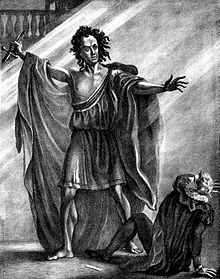

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley, while not a zombie novel proper, prefigures many 20th century ideas about zombies in that the resurrection of the dead is portrayed as a scientific process rather than a mystical one, and that the resurrected dead are degraded and more violent than their living selves. Frankenstein, published in 1818, has its roots in European folklore,[5] whose tales of vengeful dead also informed the evolution of the modern conception of vampires as well as zombies. Later notable 19th century stories about the avenging undead included Ambrose Bierce's The Death of Halpin Frayser, and various Gothic Romanticism tales by Edgar Allan Poe. Though their works could not be properly considered zombie fiction, the supernatural tales of Bierce and Poe would prove influential on later undead-themed writers such as H. P. Lovecraft, by Lovecraft's own admission.[6]

In the 1920s and early 1930s, the American horror author H. P. Lovecraft wrote several novelettes that explored the undead theme from different angles. "Cool Air", "In the Vault", and "The Outsider" all deal with the undead, but the most definitive "zombie-type" story in Lovecraft's oeuvre was 1921's Herbert West–Reanimator, which "helped define zombies in popular culture".[7] This Frankenstein-inspired series featured Herbert West, a mad scientist who attempts to revive human corpses with mixed results. Notably, the resurrected dead are uncontrollable, mostly mute, primitive and extremely violent; though they are not referred to as zombies, their portrayal was prescient, anticipating the modern conception of zombies by several decades.

The 1936 film Things to Come, based on the novel by H. G. Wells, anticipates later zombie films with an apocalyptic scenario surrounding "the wandering sickness", a highly contagious viral plague that causes the infected to wander slowly and insensibly, very much like zombies, infecting others on contact.[8] Things to Come has been regarded as an early example of the genre in which a small number of people survive in a "devastated landscape menaced by voracious enemies"[9] and has been compared favorably to modern zombie movies.

Avenging zombies would feature prominently in the early 1950s EC Comics such as Tales from the Crypt, which George A. Romero would later claim as an influence. The comics, including Tales, Vault of Horror and Weird Science, featured avenging undead in the Gothic tradition quite regularly, including adaptations of Lovecraft's stories which included "In the Vault", "Cool Air" and Herbert West–Reanimator.[10]

Richard Matheson's 1954 novel I Am Legend, although classified as a vampire story would nonetheless have definitive impact on the zombie genre by way of George A. Romero. The novel and its 1964 film adaptation, The Last Man on Earth, which concern a lone human survivor waging war against a world of vampires, would by Romero's own admission greatly influence his 1968 low-budget film Night of the Living Dead;[11][12] a work that would prove to be more influential on the concept of zombies than any literary or cinematic work before it.

George A. Romero and the modern zombie film

The modern conception of the zombie owes itself almost entirely to George A. Romero's 1968 film Night of the Living Dead.[1][13][14] In his films, Romero "bred the zombie with the vampire, and what he got was the hybrid vigour of a ghoulish plague monster".[15] This entailed an apocalyptic vision of monsters that have come to be known as Romero zombies.

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times chided theater owners and parents who allowed children access to the film. "I don't think the younger kids really knew what hit them," complained Ebert. "They were used to going to movies, sure, and they'd seen some horror movies before, sure, but this was something else." According to Ebert, the film affected the audience immediately:

The kids in the audience were stunned. There was almost complete silence. The movie had stopped being delightfully scary about halfway through, and had become unexpectedly terrifying. There was a little girl across the aisle from me, maybe nine years old, who was sitting very still in her seat and crying.[16]

Romero's reinvention of zombies is notable in terms of its thematics; he used zombies not just for their own sake, but as a vehicle "to criticize real-world social ills—such as government ineptitude, bioengineering, slavery, greed and exploitation—while indulging our post-apocalyptic fantasies".[17] Night was the first of six films in Romero's Living Dead series. Its first sequel, Dawn of the Dead, was released in 1978.

Lucio Fulci's Zombi 2 was released just months after Dawn of the Dead and acted as an unofficial sequel (Dawn of the Dead was released in several other countries as Zombi or Zombie).[1]

The 1981 film Hell of the Living Dead referenced a mutagenic gas as a source of zombie contagion, an idea also used in Dan O'Bannon's 1985 film Return of the Living Dead. Return of the Living Dead featured zombies which hungered specifically for brains instead of all human flesh.

The mid-1980s produced few zombie films of note. Perhaps the most notable entry, The Evil Dead series, while highly influential are not technically zombie films but films about demonic possession, despite the presence of the undead. 1985's Re-Animator, loosely based on the Lovecraft story, stood out in the genre, achieving nearly unanimous critical acclaim,[18] and becoming a modest success, nearly outstripping Romero's Day of the Dead for box office returns.

After the mid-1980s, the subgenre was mostly relegated to the underground. Notable entries include director Peter Jackson's ultra-gory film Braindead (1992) (released as Dead Alive in the U.S.), Bob Balaban's comic 1993 film My Boyfriend's Back where a self-aware high school boy returns to profess his love for a girl and his love for human flesh, and Michele Soavi's Dellamorte Dellamore (1994) (released as Cemetery Man in the U.S.). Several years later, zombies experienced a renaissance in low-budget Asian cinema, with a sudden spate of dissimilar entries including Bio Zombie (1998), Wild Zero (1999), Junk (1999), Versus (2000) and Stacy (2001).

The turn of the millennium coincided with a decade of box office successes in which the zombie sub-genre experienced a resurgence: the Resident Evil movies (2002, 2004, 2007, 2010, 2012); the Dawn of the Dead remake (2004),[1] the British films 28 Days Later and 28 Weeks Later (2002, 2007)[19][20] and the comedy/homage Shaun of the Dead (2004). The new interest allowed Romero to create the fourth entry in his zombie series: Land of the Dead, released in the summer of 2005. Romero returned to the series with the films Diary of the Dead (2008) and Survival of the Dead (2010).[1]

Generally the zombies in these situations are the slow, lumbering and unintelligent kind first made popular in Night of the Living Dead.[21] Motion pictures created within the 2000s, however, like the Dawn of the Dead remake, and House of the Dead,[22] have featured zombies that are more agile, vicious, intelligent, and stronger than the traditional zombie.[23] In many cases, these fast-moving zombies are depicted as living humans infected with a mind-altering pathogen (as in 28 Days Later, Zombieland and Left 4 Dead) instead of re-animated corpses.

The name "zombie"

How these creatures came to be called "zombies" is not fully clear. The film Night of the Living Dead made no spoken reference to its undead antagonists as "zombies", describing them instead as "ghouls", though this is inaccurate if compared to the original "ghoul" of Arabic folklore. Although George Romero used the term "ghoul" in his original scripts, in later interviews he used the term "zombie" without explanation. The word "zombie" is used exclusively by Romero in his 1978 script for his sequel Dawn of the Dead,[24] including once in dialog.

One of the first books to expose Western culture to the concept of the Vodun zombie was The Magic Island by W.B. Seabrook in 1929. Island is the sensationalized account of a narrator in Haiti who encounters voodoo cults and their resurrected thralls. Time claimed that the book "introduced 'zombi' into U.S. speech".[25]

In 1932, Victor Halperin directed White Zombie, a horror film starring Bela Lugosi. Here zombies are depicted as mindless, unthinking henchmen under the spell of an evil magician. Zombies, often still using this voodoo-inspired rationale, were initially uncommon in cinema, but their appearances continued sporadically through the 1930s to the 1960s, with notable films including I Walked With a Zombie (1943) and Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959).

Zombie apocalypse

Intimately tied to the conception of the modern zombie is the "zombie apocalypse"; the breakdown of society as a result of an initial zombie outbreak which spreads. This archetype has emerged as a prolific subgenre of apocalyptic fiction and been portrayed in many zombie-related media post-Night.[26] In a zombie apocalypse, a widespread (usually global) rise of zombies hostile to human life engages in a general assault on civilization. Victims of zombies may become zombies themselves. This causes the outbreak to become an exponentially growing crisis: the spreading "zombie plague/virus" swamps normal military and law enforcement organizations, leading to the panicked collapse of civilian society until only isolated pockets of survivors remain, scavenging for food and supplies in a world reduced to a pre-industrial hostile wilderness.

Subtext

The usual subtext of the zombie apocalypse is that civilization is inherently fragile in the face of truly unprecedented threats and that most individuals cannot be relied upon to support the greater good if the personal cost becomes too high. The narrative of a zombie apocalypse carries strong connections to the turbulent social landscape of the United States in the 1960s when Night of the Living Dead was first created.[27][28] Many also feel that zombies allow people to deal with their own anxiety about the end of the world.[29] One scholar concluded that "more than any other monster, zombies are fully and literally apocalyptic ... they signal the end of the world as we have known it."[26]

Due to a large number of thematic films and video games, the idea of a zombie apocalypse has entered the mainstream and there have been efforts by many fans to prepare for the hypothetical future zombie apocalypse. Efforts include creating weapons and selling posters to inform people on how to survive a zombie outbreak, although most of these are not meant to be taken literally and are jovial in nature.[30]

Story elements

There are several common themes that create a zombie apocalypse:

- Initial contacts with zombies are extremely traumatic, causing shock, panic, disbelief and possibly denial, hampering survivors' ability to deal with hostile encounters.[31]

- The response of authorities to the threat is slower than its rate of growth, giving the zombie plague time to expand beyond containment. This results in the collapse of the given society. Zombies take full control while small groups of the living must fight for their survival.[31]

The stories usually follow a single group of survivors, caught up in the sudden rush of the crisis. The narrative generally progresses from the onset of the zombie plague, then initial attempts to seek the aid of authorities, the failure of those authorities, through to the sudden catastrophic collapse of all large-scale organization and the characters' subsequent attempts to survive on their own. Such stories are often squarely focused on the way their characters react to such an extreme catastrophe, and how their personalities are changed by the stress, often acting on more primal motivations (fear, self-preservation) than they would display in normal life.[31][32]

Government and media response

On 18 May 2011, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a graphic novel, Preparedness 101: Zombie Apocalypse providing tips to survive a zombie invasion as a "fun new way of teaching the importance of emergency preparedness".[33] The CDC goes on to summarize cultural references to a zombie apocalypse. It uses these to underscore the value of laying in water, food, medical supplies, and other necessities in preparation for any and all potential disasters, be they hurricanes, earthquakes, tornadoes, floods, or hordes of zombies.[33] The CDC provides a Zombie Pandemic graphic novel.[34]

On 17 October 2011, The Weather Channel published an article, "How To Weather the Zombie Apocalypse" that included a fictional interview with a Director of Research at the CDD, the "Center for Disease Development".[35] Questions answered include "How does the temperature affect zombies' abilities? Do they run faster in warmer temperatures? Do they freeze if it gets too cold?"[35]

Use in theoretical academic papers

"While aggressive quarantine may contain the epidemic, or a cure may lead to coexistence of humans and zombies, the most effective way to contain the rise of the undead is to hit hard and hit often."

—Philip Munz, Ioan Hudea, Joe Imad, and Robert J. Smith?,

"When Zombies Attack!" (2009)[36]According to a 2009 Carleton University and University of Ottawa epidemiological analysis, an outbreak of even Living Dead's slow zombies "is likely to lead to the collapse of civilization, unless it is dealt with quickly." Based on their mathematical modelling, the authors concluded that offensive strategies were much more reliable than quarantine strategies, due to various risks that can compromise a quarantine. They also found that discovering a cure would merely leave a few humans alive, since this would do little to slow the infection rate.

On a longer time scale, the researchers found that all humans end up turned or dead. This is because the main epidemiological risk of zombies, besides the difficulties of neutralizing them, is that their population just keeps increasing; generations of humans merely "surviving" still have a tendency to feed zombie populations, resulting in gross outnumbering. The researchers explain that their methods of modelling may be applicable to the spread of political views or diseases with dormant infection.[36]

Adam Chodorow of the Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law at Arizona State University investigated the estate and income tax implications of a zombie apocalypse under United States federal and state tax codes. He notes that being dead is different from being undead, and states that "most self-motivated zombies likely would be considered alive under most state law definitions", similar to victims of strokes or Alzheimer's Disease, or those in a persistent vegetative state. Whether a reanimated zombie should be considered the same being as when he was originally alive is, according to Chodorow, much less clear. Due to such potential legal complications, he recommends that legislators enact special tax laws for the undead.[37]

The Zombie Institute for Theoretical Studies (ZITS) is a program through the University of Glasgow. It is "headed" by Dr. Austin, a character created by the university to be the face of ZITS. The ZITS team is dedicated to using real science to explain what could be expected in the event of an actual zombie apocalypse. Much of their research is used to disprove common beliefs about the zombie apocalypse as shown in popular media. They have published one book (Zombie Science 1Z) and give public "spoof" lectures on the subject.[38]

Neuroscientists Bradley Voytek and Timothy Verstynen have built a side career in describing the nature of a zombie brain in considerable detail, based heavily on real world neuroscience ideas. Their work has been featured in Forbes, New York Magazine, and other publications.[39]

Social activism

Some zombie fans continue the George A. Romero tradition of using zombies as a social commentary. Organized zombie walks, which are primarily promoted through word of mouth, are regularly staged in some countries. Usually they are arranged as a sort of surrealist performance art, but they are occasionally organized as part of a political protest.[40][41][42][43][44]

In popular culture

In art

Artist Jillian McDonald has made several works of video art involving zombies, and exhibited them in her 2006 show, “Horror Make-Up,” which debuted on 8 September 2006 at Art Moving Projects, a gallery in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Others have included “Zombie Loop” and “Zombie Portraits”.[45]

Artist Karim Charredib has dedicated his work to the zombie figure. In 2007, he made a video installation at villa Savoye called "Them !!!" where zombies walked in the villa like tourists.[46] He has also made a series of collages, inserting zombies in the background of famous movies, such as North by Northwest, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Gone With The Wind and Casablanca.[47]

In comics

Robert Kirkman, an admirer of Romero, launched a self-published comic book The Walking Dead, and wrote Marvel Zombies in 2006. DC Comics' Geoff Johns introduced a revenant-staffed Black Lantern Corps, consisting of the maliciously animated corpses of fallen DC metahumans during its "Blackest Night" story arc.

DC Comics continued producing zombie comics on their digital imprint Zuda Comics. The Black Cherry Bombshells takes place in a world of all where all the men have turned into zombies and women gangs fight with them and each other.

In 1973, Marvel Comics launched a black and white magazine series entitled Tales of the Zombie featuring the adventures of Simon William Garth aka the Zombie. After the series ended in 1975, the character was resurrected in 1993 and has appeared a few times in Spider-Man-related comic book series. From 2005, Marvel Comics used zombies and the zombie apocalypse scenario as the focus of their series Marvel Zombies, in which the superheroes of the Marvel Universe were transformed into zombies.

In gaming

Zombies are a popular theme for video games, particularly of, but not limited to, the survival horror, first-person shooter and role-playing game genres. Some important titles in this area include the Resident Evil series, Silent Hill series, Dead Rising (and its sequel Dead Rising 2), House of the Dead, Dead Island, Left 4 Dead and the Zombies game modes from Call of Duty: World at War, Call of Duty: Black Ops and Call of Duty: Black Ops II.[48] PopCap Games' Plants vs. Zombies, a humorous tower defense game, was an indie hit in 2009, featuring in several best-of lists at the end of that year. The massively multiplayer online role-playing game Urban Dead, a free grid-based browser game where zombies and survivors fight for control of a ruined city, is one of the most popular games of its type, with an estimated 30,680 visits per day.[49] DayZ, a zombie-based survival horror mod for ArmA 2, was responsible for over 300,000 unit sales of its parent game within two months of its release.[50] Some games even allow the gamer to play as a zombie. In the game Stubbs the Zombie in "Rebel Without a Pulse", zombies are impervious to most attacks, except trauma to the head (which would instantly "kill" the zombie). The game Left 4 Dead and its sequel Left 4 Dead 2 pit two teams against each other, one team consists of humans attempting to make it to a safe room while the other team consists of "specialized" zombies attempting to stop them. Early platforms to feature zombie games included the Super Nintendo and Sega Genesis, which featured a game entitled Zombies Ate My Neighbors that was produced in 1993.

Outside of video games, zombies frequently appear in trading card games such as Magic: The Gathering, as well as in role-playing games such as Dungeons & Dragons and tabletop wargames such as Warhammer Fantasy and 40K. The RPG All Flesh Must Be Eaten is premised upon a zombie outbreak and features rules for zombie campaigns in many historical settings. The online game Minecraft has a common enemy zombie, which chases and/or kills you.

The award-winning Zombies!!! series of board games by Twilight Creations features players attempting to escape from a zombie-infested city. Cheapass Games has released five other zombie-themed games, including Give Me the Brain, The Great Brain Robbery, and Lord of the Fries, which takes place at Friedey's, a fast-food restaurant staffed by minimum wage zombies. Last Night on Earth is a boardgame covering many stereotypes of the zombie movie genre.

The game Humans vs. Zombies is a popular zombie-themed live-action game played on many college campuses. The game starts with one "Zombie" and a group of "Humans." The ultimate goal of the game is for either all Humans to be turned into Zombies, or for the humans to survive a set amount of time. Humans defend themselves using socks or dart guns, stunning the Zombie players; Zombies are unarmed and must tag a Human in order to turn him or her into a Zombie. Safe zones are established so that players can eat, sleep and go to class in safety.[51]

In merchandise

Many companies from around the world have also put strong focus on creating products geared towards the 'zombie' culture. This list includes a company in California, Harcos Labs, that sells bagged Zombie Blood and Zombie Jerky in specimen style pouches;[52] and an array of small companies creating novelty products such as Zombie Mints, Screaming Zombie Energy Drink, and Gummy Brains. These items have been incorporated into cosplay during zombie walks around the world.

In music

Zombies and horror have become so popular that many songs and bands have been based on these flesh-eating ghouls; most notably the musician Roky Erickson whose post 13th Floor Elevators music based on zombie and other horror themes was profoundly influential on later musicians such as Rob Zombie, who has incorporated zombie aesthetics and references into virtually all of his work. Zombie references crop up in every genre from pop to death metal and some subgenres such as horror punk mine the zombie aesthetic extensively. Horror punk has also been linked with the subgenres of deathrock and psychobilly. The success of these genres has been mainly underground, although psychobilly has reached some mainstream popularity.

Producers have acquired[when?] the rights to Michael Jackson's Thriller for a proposed Broadway musical, "complete with dancing undead."[53]

The song "Re: Your Brains" by Jonathan Coulton is a song from the perspective of an office employee turned zombie.

Send More Paramedics were a horror film-influenced crossover thrash band from Leeds in the north of England. The band played in the 1980s crossover style, what they described as "Zombiecore...a fusion of 80s thrash and modern hardcore punk", with lyrics about zombies and cannibalism, and were heavily influenced by zombie movies.

In print and literature

In the 1990s, zombie fiction emerged as a distinct literary subgenre, with the publication of Book of the Dead in 1990 and its follow-up Still Dead: Book of the Dead 2 in 1992, both edited by horror authors John Skipp and Craig Spector. Featuring Romero-inspired stories from the likes of Stephen King and other famous names, the Book of the Dead compilations are regarded as influential in the horror genre and perhaps the first true "zombie literature". hiiiiii

Recent zombie fiction of note includes Brian Keene's 2005 novel The Rising, followed by its sequel City of the Dead, which deal with a worldwide apocalypse of intelligent zombies, caused by demonic possession. Though the story took many liberties with the zombie concept, The Rising proved itself to be a success in the subgenre, even winning the 2005 Bram Stoker award.[54]

Famed horror novelist Stephen King has mined the zombie theme, first with his 1990 short story "Home Delivery", written for the aforementioned Book of the Dead compilation and detailing a small town's attempt to defend itself from a classic zombie outbreak. In 2006, King published Cell, which concerns a struggling young artist on a trek from Boston to Maine in hopes of saving his family from a possible worldwide zombie outbreak, created by "The Pulse", a global electromagnetic phenomenon that turns the world's cellular phone users into bloodthirsty, zombie-like maniacs. Cell was a number-one bestseller upon its release.[55]

Aside from Cell, the best-known current work of zombie fiction is 2006's World War Z by Max Brooks, which was an immediate hit upon its release and a New York Times bestseller.[56] Brooks had previously authored the cult hit The Zombie Survival Guide, an exhaustively researched, zombie-themed parody of pop-fiction survival guides published in 2003.[53] Brooks has said that zombies are so popular because:

Other monsters may threaten individual humans, but the living dead threaten the entire human race.... Zombies are slate wipers.

David Wellington's trilogy of zombie novels began in 2004 with Monster Island, followed by two sequels, Monster Nation and Monster Planet.

Jonathan Maberry's Zombie CSU: The Forensics of the Living Dead, released in August 2008, interviewed over 250 experts in forensics, medicine, science, law enforcement, the military and similar disciplines to discuss how the real world would react, research and respond to zombies.

In 2009, Katy Hershbereger of St. Martin's Press stated "In the world of traditional horror, nothing is more popular right now than zombies.... The living dead are here to stay."[53] The mashup novel Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (2009) by Seth Grahame-Smith combines the full text of Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen with a story about a zombie epidemic within the novel's British Regency period setting.[53]

In television and video

One of the most famous zombie-themed television appearances was 1983's Thriller, a Michael Jackson music video featuring choreographed zombies dancing with the singer. Many pop culture media have paid tribute to this scene alone[citation needed], including zombie films such as Return of the Living Dead 2.

See also

- Apocalypticism

- Doomsday film

- List of zombie short films and undead-related projects

- List of apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic fiction

- Vampire fiction

References

- ^ a b c d e J.C. Maçek III (15 June 2012). "The Zombification Family Tree: Legacy of the Living Dead". PopMatters.

- ^ Deborah Christie, Sarah Juliet Lauro, ed. (2011). Better Off Dead: The Evolution of the Zombie as Post-Human. Fordham Univ Press. p. 169. ISBN 0-8232-3447-9, 9780823234479.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Boston Globe The CDC want you to prepare for the zombie apocalypse by Jesse Nunes 20 May 2011 ]

- ^ a b Ancienttexts.org The Epic of Gilgamesh, Tablet VI

- ^ Warner, Marina. A forgotten gem: Das Gespensterbuch ('The Book of Ghosts'), An Introduction

- ^ H. P. Lovecraft, Supernatural Horror in Literature (1927, 1933–1935)

- ^ "Our Favorite Zombies", Underground Online

- ^ Things to Come

- ^ Philip French, 28 Days Later (film review), The Observer, 3 November 2002.

- ^ "H. P. Lovecraft in the comics"

- ^ Clasen, Mathias (2010). "Vampire Apocalypse: A Biocultural Critique of Richard Matheson's I Am Legend". Philosophy and Literature.

- ^ Biodrowski, Steve. "Night of the Living Dead: The classic film that launched the modern zombie genre"

- ^ Stephen Harper, Night of the Living Dead: Reappraising an Undead Classic. Bright Lights Film Journal, Issue 50, November 2005. Brightlightsfilm.com

- ^ Pulliam, June (2006). "The Zombie". In Joshi, S. T. (ed.). Icons of Horror and the Supernatural. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313337802.

- ^ Twitchell, James B. (1985). Dreadful Pleasures: An Anatomy of Modern Horror. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195035666.

- ^ Roger Ebert, review of Night of the Living Dead, Chicago Sun-Times, January 5, 196[9], at RogerEbert.com; last accessed June 24, 2006.

- ^ Liz Cole, Zombies

- ^ Rotten Tomatoes Rottentomatoes.com

- ^ Kermode, Mark (6 May 2007). "A capital place for panic attacks". London: Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 12 May 2007.

- ^ "Stylus Magazine's Top 10 Zombie Films of All Time".

- ^ a b Cronin, Brian (3 December 2008). "John Seavey's Storytelling Engines: George Romero's "Dead" Films". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- ^ The Running Dead – How did movie zombies get so fast? By Josh Levin Posted Wednesday, 19 December 2007, at 7:34 am ET

- ^ Levin, Josh (24 March 2004). "Dead Run". Slate. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- ^ George A. Romero Dawn of the Dead (Working draft 1977) Horrorlair.com

- ^ "Mumble-Jumble", Time, 9 September 1940.

- ^ a b Paffenroth, Kim (2006). Gospel of the Living Dead: George Romero's Visions of Hell on Earth. Waco: Baylor University Press. ISBN 1932792651.

- ^ Rockoff, Adam (2002). Going to Pieces: The Rise and Fall of the Slasher Film, 1978–1986. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. p. 35. ISBN 0-7864-1227-5.

- ^ Clute, John; Grant, John, eds. (1999). "Zombie Movies". The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 1048. ISBN 0-312-19869-8.

- ^ Cripps, Charlotte (1 November 2006). "Preview: Max Brooks' Festival of the (Living) Dead! Barbican, London". The Independent. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- ^ Harrison, Michael (5 December 2008). "10 Geeky Gifts for Under $10". Wired. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c Kenreck, Todd (17 November 2008). "Surviving a zombie apocalypse: 'Left 4 Dead' writer talks about breathing life into zombie genre". Video game review. msnbc. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ^ Daily, Patrick. "Max Brooks". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- ^ a b "Preparedness 101: Zombie Apocalypse". Bt.cdc.gov. 16 May 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ http://www.cdc.gov/phpr/documents/11_225700_A_Zombie_Final.pdf

- ^ a b Morris, Casey. "How To Weather the Zombie Apocalypse". Weather.com. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- ^ a b "When Zombies Attack!: Mathematical Modelling of an Outbreak of Zombie Infection", by Philip Munz, Ioan Hudea, Joe Imad and Robert J. Smith?. In Infectious Disease Modelling Research Progress, eds. J.M. Tchuenche and C. Chiyaka, Nova Science Publishers, Inc. pp. 133–150, 2009. ISBN 978-1-60741-347-9.

- ^ Chodorow, Adam (2012). "Death and Taxes and Zombies". Iowa Law Review.

- ^ "Zombie Institute for Theoretical Studies". 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ "Zombies on the Brain". The Chronicle of Higher Education.

- ^ Colley, Jenna. "Zombies haunt San Diego streets". signonsandiego.com. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ^ Kemble, Gary. "They came, they saw, they lurched". Australia: ABC. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ^ Dalgetty, Greg. "The Dead Walk". Penny Blood magazine. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ^ Horgen, Tom. "Nightlife: 'Dead' ahead". StarTribune.com. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ^ Dudiak, Zandy. "Guinness certifies record for second annual Zombie Walk". yourpenntrafford.com. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ^ Kino, Carol (30 July 2006). "Jillian Mcdonald, Performance Artist, Forsakes Billy Bob Thornton for Zombies". New York Times. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ^ "CERAP - Centre d'Etudes et de Recherches en Arts Plastiques". Cerap.univ-paris1.fr. 1 December 1994. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ "CERAP - Centre d'Etudes et de Recherches en Arts Plastiques". Cerap.univ-paris1.fr. 1 December 1994. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ Christopher T. Fong (2 December 2008). "Playing Games: Left 4 Dead". Video game review. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ^ www.urbandead.com web stats from SurCentro.com

- ^ Usher, William (1 July 2012). "DayZ Helps Arma 2 Rack Up More Than 300,000 In Sales". Cinema Blend. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ^ Wexler, Laura. "Commando Performance". The Washington Post. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ^ Eaton, Kit (11 May 2010). "Zombie Blood Quenches Thirst, Boosts Energy, Turns Consumers Into Brain-dead Horde". Fast Company. Fast Company. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ a b c d Craig Wilson, "Zombies lurch into popular culture via books, plays, more," USA Today, 9 April 2009, p. 1D (1st page of Life section, above the fold), found at Zombies lurch into popular culture article at USA Today. Retrieved 13 April 2009.

- ^ Past Stoker Nominees & Winners http://www.horror.org/stokerwinnom.htm

- ^ The New York Times, 12 February 2006

- ^ The New York Times, 15 November 2006