OccultZone (talk | contribs) |

72.196.235.154 (talk) Undid revision 654020050 by OccultZone (talk)No proof of Sock. |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Women in society sidebar}} |

{{Women in society sidebar}} |

||

The status of '''women in India''' has been subject to many great changes over the past few millennia.<ref name="The Hindu">{{cite news|title=Rajya Sabha passes Women's Reservation Bill |url=http://hindu.com/2010/03/10/stories/2010031050880100.htm|publisher=The Hindu|accessdate=25 August 2010|location=Chennai, India|date=10 March 2010}}</ref><ref name="The Hindu"/> From |

The status of '''women in India''' has been subject to many great changes over the past few millennia.<ref name="The Hindu">{{cite news|title=Rajya Sabha passes Women's Reservation Bill |url=http://hindu.com/2010/03/10/stories/2010031050880100.htm|publisher=The Hindu|accessdate=25 August 2010|location=Chennai, India|date=10 March 2010}}</ref><ref name="The Hindu"/> From greater equality with men in ancient times<ref>{{Cite book | last = Jayapalan| title = Indian society and social institutions| publisher = Atlantic Publishers & Distri.| year = 2001| page = 145| url = http://books.google.co.in/books?id=gVo1I4SIqOwC&pg=PA145| isbn = 978-81-7156-925-0}}</ref> through the low points of the medieval period,<ref name="nrcw_history" /> to the promotion of [[women's rights|equal rights]] by many reformers, the history of women in India has been eventful. In modern India, women have held high offices in India including that of the [[List of Presidents of India|President]], [[List of Prime Ministers of India|Prime Minister]], [[Speaker of the Lok Sabha#List of Speakers|Speaker of the Lok Sabha]] and |

||

[[Leader of the Opposition (India)|Leader of the Opposition]]. |

[[Leader of the Opposition (India)|Leader of the Opposition]]. |

||

Revision as of 15:40, 29 March 2015

Pratibha Devisingh Patil was the 12th President of the Republic of India and first woman to hold the office.[1] | |

| General Statistics | |

|---|---|

| Maternal mortality (per 100,000) | 200 (2008) |

| Women in parliament | 10.9% (2012) |

| Women over 25 with secondary education | 26.6% (2010) |

| Women in labour force | 29.0% (2011) |

| Gender Inequality Index | |

| Value | 0.610 (2012) |

| Rank | 132nd |

| Global Gender Gap Index[2] | |

| Value | 0.6551 (2013) |

| Rank | 101st |

| Part of a series on |

| Women in society |

|---|

|

The status of women in India has been subject to many great changes over the past few millennia.[3][3] From greater equality with men in ancient times[4] through the low points of the medieval period,[5] to the promotion of equal rights by many reformers, the history of women in India has been eventful. In modern India, women have held high offices in India including that of the President, Prime Minister, Speaker of the Lok Sabha and Leader of the Opposition.

As of 2011[update], the Speaker of the Lok Sabha and the Leader of the Opposition in the Lok Sabha (Lower House of the parliament) were women. However, women in India continue to face atrocities such as rape, acid throwing, dowry killings, and the forced prostitution of young girls.[6][7][8]

History

Ancient India

According to scholars, women in ancient India enjoyed equal status with men in all aspects of life.[9] Works by ancient Indian grammarians such as Patanjali and Katyayana suggest that women were educated in the early Vedic period.[10][11] Rigvedic verses suggest that women married at a mature age and were probably free to select their own husbands.[12] Scriptures such as the Rig Veda and Upanishads mention several women sages and seers, notably Gargi and Maitreyi.[13]

There are very few texts specifically dealing with the role of women[14] an important exception is the Stri Dharma Paddhati of Tryambakayajvan, an official at Thanjavur c. 1730. The text compiles strictures on women's behaviour dating back to the Apastamba sutra (c. 4th century BCE).[15] The opening verse goes:

- mukhyo dharmaH smr^tiShu vihito bhartr^shushruShANam hi :

- women are enjoined to be of service to their husbands.

Some kingdoms in ancient India had traditions such as nagarvadhu ("bride of the city"). Women competed to win the coveted title of nagarvadhu. Amrapali is the most famous example of a nagarvadhu.

According to studies, women enjoyed equal status and rights during the early Vedic period.[16] However in approximately 500 B.C., the status of women began to decline, and with the Islamic invasion of Babur and the Mughal empire and Christianity later worsened women's freedom and rights.[5]

Although reform movements such as Jainism allowed women to be admitted to religious orders, by and large women in India faced confinement and restrictions.[16] The practice of child marriages is believed to have started around the sixth century.[17]

Medieval period

Indian women's position in society further deteriorated during the medieval period,[5][9] when child marriages and a ban on remarriage by widows became part of social life in some communities in India. The Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent brought purdah to Indian society. Among the Rajputs of Rajasthan, the Jauhar was practised. In some parts of India, some of Devadasis were sexually exploited. Polygamy was practised among Hindu Kshatriya rulers for some political reasons.[17] In many Muslim families, women were restricted to Zenana areas of the house.

In spite of these conditions, women often became prominent in the fields of politics, literature, education and religion.[5] Razia Sultana became the only woman monarch to have ever ruled Delhi. The Gond queen Durgavati ruled for fifteen years before losing her life in a battle with Mughal emperor Akbar's general Asaf Khan in 1564. Chand Bibi defended Ahmednagar against the powerful Mughal forces of Akbar in the 1590s. Jehangir's wife Nur Jehan effectively wielded imperial power, and was recognized as the real power behind the Mughal throne. The Mughal princesses Jahanara and Zebunnissa were well-known poets, and also influenced the ruling powers. Shivaji's mother, Jijabai, was queen regent because of her ability as a warrior and an administrator. In South India, many women administered villages, towns, and divisions, and ushered in new social and religious institutions.[17]

The Bhakti movements tried to restore women's status and questioned certain forms of oppression.[16] Mirabai, a female saint-poet, was one of the most important Bhakti movement figures. Other female saint-poets from this period included Akka Mahadevi, Rami Janabai and Lal Ded. Bhakti sects within Hinduism such as the Mahanubhav, Varkari and many others were principle movements within the Hindu fold openly advocating social justice and equality between men and women.

Immediately following the Bhakti movements, Guru Nanak, the first Guru of Sikhs, preached equality between men and women. He advocated that women be allowed to lead religious assemblies; to lead congregational hymn singing called Kirtan or Bhajan; to become members of religious management committees; to lead armies on the battlefield; to have equality in marriage, and to have equality in Amrit (Baptism). Other Sikh Gurus also preached the same, but their practices were often regarded to be a breach of women rights.

Historical practices

Traditions such as Sati, Jauhar, and Devadasi among some communities have been banned and are largely defunct in modern India. However, some instances of these practices are still found in remote parts of India. The purdah is still practiced by Indian women in some communities. Child marriage remains common in rural areas, although it is illegal under current Indian law.

- Sati

- Sati is an old, almost completely defunct custom among some communities, in which the widow was immolated alive on her husband's funeral pyre. Although the act was supposed to be voluntary on the widow's part, its practice is forbidden by the Hindu scriptures in Kali yuga, the current age.[18] After the foreign invasions of Indian subcontinent, this practice started to mark its presence, as women were often raped or kidnapped by the foreign forces.[19] It was abolished by the British in 1829. There have been around forty reported cases of sati since independence.[20] In 1987, the Roop Kanwar case in Rajasthan led to The Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act.[21]

- Jauhar

- Jauhar refers to the practice of voluntary immolation by wives and daughters of defeated warriors, in order to avoid capture and consequent molestation by the enemy. The practice was followed by the wives of defeated Rajput rulers, who are known to place a high premium on honour. Evidently such practice took place during the Islamic invasions of India.[22]

- Purdah

- Purdah is the practice among some Muslim communities requiring women to cover themselves so as to conceal their faces and form from males. It imposes restrictions on the mobility of women, curtails their right to interact freely.[citation needed]

- Devadasis

- Devadasi is often misunderstood as religious practice. It was practised in southern India, in which women were "married" to a deity or temple. The ritual was well-established by the 10th century A.D.[23] By 1988, the practice was outlawed in the country.[24]

British rule

European scholars observed in the 19th century that Hindu women are "naturally chaste" and "more virtuous" than other women.[25] During the British Raj, many reformers such as Ram Mohan Roy, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar and Jyotirao Phule fought for the betterment of women. Peary Charan Sarkar, a former student of Hindu College, Calcutta and a member of "Young Bengal", set up the first free school for girls in India in 1847 in Barasat, a suburb of Calcutta (later the school was named Kalikrishna Girls' High School).

While this might suggest that there was no positive British contribution during the Raj era, that is not entirely the case. Missionaries' wives such as Martha Mault née Mead and her daughter Eliza Caldwell née Mault are rightly remembered for pioneering the education and training of girls in south India. This practice was initially met with local resistance, as it flew in the face of tradition. Raja Rammohan Roy's efforts led to the abolition of Sati under Governor-General William Cavendish-Bentinck in 1829. Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar's crusade for improvement in the situation of widows led to the Widow Remarriage Act of 1856. Many women reformers such as Pandita Ramabai also helped the cause of women.

Kittur Chennamma, queen of the princely state Kittur in Karnataka,[26] led an armed rebellion against the British in response to the Doctrine of lapse. Abbakka Rani, queen of coastal Karnataka, led the defence against invading European armies, notably the Portuguese in the 16th century. Rani Lakshmi Bai, the Queen of Jhansi, led the Indian Rebellion of 1857 against the British. She is now widely considered as a national hero. Begum Hazrat Mahal, the co-ruler of Awadh, was another ruler who led the revolt of 1857. She refused deals with the British and later retreated to Nepal. The Begums of Bhopal were also considered notable female rulers during this period. They did not observe purdah and were trained in martial arts.

Chandramukhi Basu, Kadambini Ganguly and Anandi Gopal Joshi were some of the earliest Indian women to obtain a degree.

In 1917, the first women's delegation met the Secretary of State to demand women's political rights, supported by the Indian National Congress. The All India Women's Education Conference was held in Pune in 1927, it became a major organisation in the movement for social change.[16][27] In 1929, the Child Marriage Restraint Act was passed, stipulating fourteen as the minimum age of marriage for a girl.[16][28][full citation needed] Though Mahatma Gandhi himself married at the age of thirteen, he later urged people to boycott child marriages and called upon young men to marry child widows.[29]

Women played an important part in India's independence struggle. Some famous freedom fighters include Bhikaji Cama, Dr. Annie Besant, Pritilata Waddedar, Vijayalakshmi Pandit, Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, Aruna Asaf Ali, Sucheta Kriplani and Kasturba Gandhi. Other notable names include Muthulakshmi Reddy and Durgabai Deshmukh. The Rani of Jhansi Regiment of Subhas Chandra Bose's Indian National Army consisted entirely of women, including Captain Lakshmi Sahgal. Sarojini Naidu, a poet and freedom fighter, was the first Indian woman to become President of the Indian National Congress and the first woman to become the governor of a state in India.

Independent India

Women in India now participate fully in areas such as education, sports, politics, media, art and culture, service sectors, science and technology, etc.[5] Indira Gandhi, who served as Prime Minister of India for an aggregate period of fifteen years, is the world's longest serving woman Prime Minister.[30]

The Constitution of India guarantees to all Indian women equality (Article 14), no discrimination by the State (Article 15(1)), equality of opportunity (Article 16), and equal pay for equal work (Article 39(d)). In addition, it allows special provisions to be made by the State in favour of women and children (Article 15(3)), renounces practices derogatory to the dignity of women (Article 51(A) (e)), and also allows for provisions to be made by the State for securing just and humane conditions of work and for maternity relief. (Article 42).[31]

Feminist activism in India gained momentum in the late 1970s. One of the first national-level issues that brought women's groups together was the Mathura rape case. The acquittal of policemen accused of raping a young girl Mathura in a police station led to country-wide protests in 1979-1980. The protests, widely covered by the national media, forced the Government to amend the Evidence Act, the Criminal Procedure Code, and the Indian Penal Code; and created a new offence, custodial rape.[31] Female activists also united over issues such as female infanticide, gender bias, women's health, women's safety, and women's literacy.

Since alcoholism is often associated with violence against women in India,[32] many women groups launched anti-liquor campaigns in Andhra Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh and other states.[31] Many Indian Muslim women have questioned the fundamental leaders' interpretation of women's rights under the Shariat law and have criticized the triple talaq system.[16]

In 1990s, grants from foreign donor agencies enabled the formation of new women-oriented NGOs. Self-help groups and NGOs such as Self Employed Women's Association (SEWA) have played a major role in the advancement of women's rights in India. Many women have emerged as leaders of local movements; for example, Medha Patkar of the Narmada Bachao Andolan.

The Government of India declared 2001 as the Year of Women's Empowerment (Swashakti).[16] The National Policy For The Empowerment Of Women came was passed in 2001.[33]

In 2006, the case of Imrana, a Muslim rape victim, was highlighted by the media. Imrana was raped by her father-in-law. The pronouncement of some Muslim clerics that Imrana should marry her father-in-law led to widespread protests, and finally Imrana's father-in-law was sentenced to 10 years in prison. The verdict was welcomed by many women's groups and the All India Muslim Personal Law Board.[34]

According to a report by Thomson Reuters, India is the "fourth most dangerous country" in the world for women,[35][36] India was also noted as the worst country for women among the G20 countries,[37] however, this report has faced criticism for its inaccuracy.[38] In 9 March 2010, one day after International Women's day, Rajya Sabha passed the Women's Reservation Bill requiring that 33% of seats in India's Parliament and state legislative bodies be reserved for women.[39]

Timeline

The steady change in the position of women can be highlighted by looking at what has been achieved by women in the country:

- 1848: Savitribai Phule, along with her husband Jyotirao Phule, opened a school for girls in Pune, India. Savitribai Phule became the first woman teacher in India.

- 1879: John Elliot Drinkwater Bethune established the Bethune School in 1849, which developed into the Bethune College in 1879, thus becoming the first women's college in India.

- 1883: Chandramukhi Basu and Kadambini Ganguly became the first female graduates of India and the British Empire.

- 1886: Kadambini Ganguly and Anandi Gopal Joshi became the first women from India to be trained in Western medicine.

- 1898: Sister Nivedita Girls' School was inaugurated

- 1905: Suzanne RD Tata becomes the first Indian woman to drive a car.[40]

- 1916: The first women's university, SNDT Women's University, was founded on 2 June 1916 by the social reformer Dhondo Keshav Karve with just five students.

- 1917: Annie Besant became the first female president of the Indian National Congress.

- 1919: For her distinguished social service, Pandita Ramabai became the first Indian woman to be awarded the Kaisar-i-Hind Medal by the British Raj.

- 1925: Sarojini Naidu became the first Indian born female president of the Indian National Congress.

- 1927: The All India Women's Conference was founded.

- 1944: Asima Chatterjee became the first Indian woman to be conferred the Doctorate of Science by an Indian university.

- 1947: On 15 August 1947, following independence, Sarojini Naidu became the governor of the United Provinces, and in the process became India's first woman governor.

- 1951: Prem Mathur of the Deccan Airways becomes the first Indian woman commercial pilot.

- 1953: Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit became the first woman (and first Indian) president of the United Nations General Assembly

- 1954: Ramakrishna Sarada Mission was formed for women monks.

- 1959: Anna Chandy becomes the first Indian woman judge of a High Court (Kerala High Court)[41]

- 1963: Sucheta Kriplani became the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh, the first woman to hold that position in any Indian state.

- 1966: Captain Durga Banerjee becomes the first Indian woman pilot of the state airline, Indian Airlines.

- 1966: Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay wins Ramon Magsaysay award for community leadership.

- 1966: Indira Gandhi becomes the first woman Prime Minister of India

- 1970: Kamaljit Sandhu becomes the first Indian woman to win a Gold in the Asian Games

- 1972: Kiran Bedi becomes the first female recruit to join the Indian Police Service.[42]

- 1979: Mother Teresa wins the Nobel Peace Prize, becoming the first Indian female citizen to do so.

- 1984: On 23 May, Bachendri Pal became the first Indian woman to climb Mount Everest.

- 1986 : Surekha Yadav became the first woman loco-pilot, railway driver, for India and Asia.

- 1989: Justice M. Fathima Beevi becomes the first woman judge of the Supreme Court of India.[43]

- 1992: Priya Jhingan becomes the first lady cadet to join the Indian Army (later commissioned on 6 March 1993)[44]

Culture

A sari (a long piece of fabric wound around the body) and salwar kameez are worn by women all over India. A bindi is part of a woman's make-up. Despite common belief, the bindi on the forehead does not signify marital status; however, the Sindoor does.[45]

Rangoli (or Kolam) is a traditional art very popular among Indian women.

Education and economic development

According to 1992-93 figures, only 9.2% of the households in India were headed by females. However, approximately 35% of the households below the poverty line were found to be headed by females.[46]

Education

Though it is gradually increasing, the female literacy rate in India is less than the male literacy rate.[47] Far fewer girls than boys are enrolled in school, and many girls drop out.[31] In urban India, girls are nearly on a par with boys in terms of education. However, in rural India girls continue to be less well-educated than boys. According to the National Sample Survey Data of 1997, only the states of Kerala and Mizoram have approached universal female literacy. According to scholars, the major factor behind improvements in the social and economic status of women in Kerala is literacy.[31]

Under the Non-Formal Education programme (NFE), about 40% of the NFE centres in states and 10% of the centres in UTs are exclusively reserved for females. As of 2000, about 300,000 NFE centres were catering to about 7.42 million children. About 120,000 NFE centres were exclusively for girls.[48]

According to a 1998 report by the U.S. Department of Commerce, the chief barriers to female education in India are inadequate school facilities (such as sanitary facilities), shortage of female teachers and gender bias in the curriculum (female characters being depicted as weak and helpless).[49]

Workforce participation

Contrary to common perception, a large percentage of women in India work.[50] National data collection agencies accept that statistics seriously understate women's contribution as workers.[31] However, there are far fewer women than men in the paid workforce. In urban India, women participate in the workforce in impressive numbers. For example, in the software industry 30% of the workforce is female.[51] In the workplace women enjoy parity with their male counterparts in terms of wages and roles.

In rural India in the agriculture and allied industrial sectors, females account for as much as 89.5% of the labour force.[46] In overall farm production, women's average contribution is estimated at 55% to 66% of the total labour. According to a 1991 World Bank report, women accounted for 94% of total employment in dairy production in India. Women constitute 51% of the total employed in forest-based small-scale enterprises.[46]

One of the most famous female business success stories is the Shri Mahila Griha Udyog Lijjat Papad. In 2006, Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw, who founded Biocon, one of India's first biotech companies, was rated India's richest woman. Lalita D. Gupte and Kalpana Morparia were the only businesswomen in India who made the list of the Forbes World's Most Powerful Women in 2006. Gupte ran ICICI Bank, India's second-largest bank, until October 2006 [52] and Morparia is CEO of JP Morgan India.[53]

Land and property rights

In most Indian families, women do not own any property in their own names, and do not get a share of parental property.[31] Due to weak enforcement of laws protecting them, women continue to have little access to land and property.[54] In fact, some of the laws discriminate against women, when it comes to land and property rights.[55]

The Hindu personal laws of 1956 (applying to Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs and Jains) gave women rights to inheritances. However, sons had an independent share in the ancestral property, while the daughters' shares were based on the share received by their father. Hence, a father could effectively disinherit a daughter by renouncing his share of the ancestral property, but a son would continue to have a share in his own right. Additionally, married daughters, even those facing marital harassment, had no residential rights in the ancestral home. Thanks to amendment of the Hindu laws in 2005, women now have the same status as men.[56]

In 1986, the Supreme Court of India ruled that Shah Bano, an elderly divorced Muslim woman, was eligible for maintenance money. However, the decision was vociferously opposed by fundamentalist Muslim leaders, who alleged that the court was interfering in their personal law. The Union Government subsequently passed the Muslim Women's (Protection of Rights Upon Divorce) Act.[57]

Similarly, Christian women have struggled over years for equal rights in divorce and succession. In 1994, all churches, jointly with women's organisations, drew up a draft law called the Christian Marriage and Matrimonial Causes Bill. However, the government has still not amended the relevant laws.[16]

Crimes against women

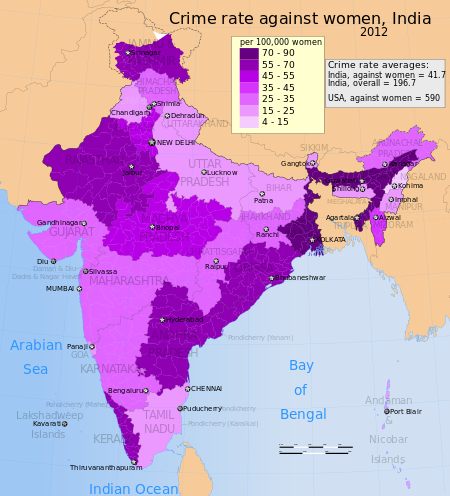

Police records in India show a high incidence of crimes against women. The National Crime Records Bureau reported in 1998 that by 2010 growth in the rate of crimes against women would exceed the population growth rate.[31] Earlier, many crimes against women were not reported to police due to the social stigma attached to rape and molestation. Official statistics show a dramatic increase in the number of reported crimes against women.[31]

Acid throwing

A Thomas Reuters Foundation survey [60] says that India is the fourth most dangerous place in the world for women to live in.[61] Women belonging to any class, caste, creed or religion can be victims of this cruel form of violence and disfigurement, a premeditated crime intended to kill or maim permanently and act as a lesson to put a woman in her place. In India, acid attacks on women[62] who dared to refuse a man's proposal of marriage or asked for a divorce [63] are a form of revenge. Acid is cheap, easily available, and the quickest way to destroy a woman's life. The number of acid attacks have been rising.[64]

Child marriage

Child marriage has been traditionally prevalent in India and continues to this day. Historically, child brides would live with their parents until they reached puberty. In the past, child widows were condemned to a life of great agony, shaved heads, living in isolation, and being shunned by society.[29] Although child marriage was outlawed in 1860, it is still a common practice.[65]

According to UNICEF’s “State of the World’s Children-2009” report, 47% of India's women aged 20–24 were married before the legal age of 18, rising to 56% in rural areas.[66] The report also showed that 40% of the world's child marriages occur in India.[67]

Domestic violence

Domestic violence in India is endemic.[68] Around 70% of women in India are victims of domestic violence, according to Renuka Chowdhury, former Union minister for Women and Child Development.[69]

The National Crime Records Bureau reveal that a crime against a woman is committed every three minutes, a woman is raped every 29 minutes, a dowry death occurs every 77 minutes, and one case of cruelty committed by either the husband or relative of the husband occurs every nine minutes.[70] This occurs despite the fact that women in India are legally protected from domestic abuse under the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act.[70]

In India, domestic violence toward women is considered as any type of abuse that can be considered a threat; it can also be physical, psychological, or sexual abuse to any current or former partner.[71] Domestic violence is not handled as a crime or complaint, it is seen more as a private or family matter.[72] In determining the category of a complaint, it is based on caste, class, religious bias and race which also determines whether action is to be taken or not.[73] Many studies have reported about the prevalence of the violence and have taken a criminal-justice approach, but most woman refuse to report it.[74] These women are guaranteed constitutional justice, dignity and equality but continue to refuse based on their sociocultural contexts. [75] As the women refuse to speak of the violence and find help, they are also not receiving the proper treatment. [76]

Dowry

In 1961, the Government of India passed the Dowry Prohibition Act,[77] making dowry demands in wedding arrangements illegal. However, many cases of dowry-related domestic violence, suicides and murders have been reported. In the 1980s, numerous such cases were reported.[50]

In 1985, the Dowry Prohibition (maintenance of lists of presents to the bride and bridegroom) Rules were framed.[78] According to these rules, a signed list should be maintained of presents given at the time of the marriage to the bride and the bridegroom. The list should contain a brief description of each present, its approximate value, the name of who has given the present, and relationship to the recipient. However, such rules are rarely enforced.

A 1997 report claimed that each year at least 5,000 women in India die dowry-related deaths, and at least a dozen die each day in 'kitchen fires' thought to be intentional.[79] The term for this is "bride burning" and is criticized within India itself. Amongst the urban educated, such dowry abuse has reduced considerably [citation needed].

Female infanticide and sex-selective abortion

In India, the male-female sex ratio is skewed dramatically in favour of males, the chief reason being the high number of females who die before reaching adulthood.[31] Tribal societies in India have a less skewed sex ratio than other caste groups. This is in spite of the fact that tribal communities have far lower income levels, lower literacy rates, and less adequate health facilities.[31] Many experts suggest the higher number of males in India can be attributed to female infanticides and sex-selective abortions.

Ultrasound scanning constitutes a major leap forward in providing for the care of mother and baby, and with scanners becoming portable, these advantages have spread to rural populations. However, ultrasound scans often reveal the sex of the baby, allowing pregnant women to decide to abort female foetuses and try again later for a male child. This practice is usually considered the main reason for the change in the ratio of male to female children being born.[80]

In 1994 the Indian government passed a law forbidding women or their families from asking about the sex of the baby after an ultrasound scan (or any other test which would yield that information) and also expressly forbade doctors or any other persons from providing that information. In practice this law (like the law forbidding dowries) is widely ignored, and levels of abortion on female foetuses remain high and the sex ratio at birth keeps getting more skewed. [81]

Female infanticide (killing of girl infants) is still prevalent in some rural areas.[31] Sometimes this is infanticide by neglect, for example families may not spend money on critical medicines or withhold care from a sick girl.

Continuing abuse of the dowry tradition has been one of the main reasons for sex-selective abortions and female infanticides in India.

Rape

Rape in India has been described by Radha Kumar as one of India's most common crimes against women[82] and by the UN’s human-rights chief as a “national problem”.[83] In the 1980s, women's rights groups lobbied for marital rape to be declared unlawful, as until 1983, the criminal law (amendment) act stated that "sexual intercourse by a man with his own wife, the wife not being under fifteen years of age is not rape". Marital rape is still not a criminal offence.[82] While per-capita reported incidents are quite low compared to other countries, even developed countries,[84][85] a new case is reported every 20 minutes.[86][87]

New Delhi has the highest rate of rape-reports among Indian cities.[88] Sources show that rape cases in India have doubled between 1990 and 2008.[89][90]

Sexual harassment

Eve teasing is a euphemism used for sexual harassment or molestation of women by men. Many activists blame the rising incidents of sexual harassment against women on the influence of "Western culture". In 1987, The Indecent Representation of Women (Prohibition) Act was passed[91] to prohibit indecent representation of women through advertisements or in publications, writings, paintings or in any other manner.

Of the total number of crimes against women reported in 1990, half related to molestation and harassment in the workplace.[31] In 1997, in a landmark judgement[ambiguous], the Supreme Court of India took a strong stand against sexual harassment of women in the workplace. The Court also laid down detailed guidelines for prevention and redressal of grievances. The National Commission for Women subsequently elaborated these guidelines into a Code of Conduct for employers.[31] In 2013 India's top court investigated on a law graduate's allegation that she was sexually harassed by a recently retired Supreme Court judge.[92] Recently, The Sexual Harassment ofWomenat Workplace ( Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 came into force on Dec 2013, to prevent Harassment of women at workplace.

Trafficking

The Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act was passed in 1956.[93] However many cases of trafficking of young girls and women have been reported. These women are either forced into prostitution, domestic work or child labour.

Legal status

List

- Guardians & Wards Act, 1890[94]

- Indian Penal Code, 1860

- Christian Marriage Act, 1872

- Indian Evidence Act, 1872[95]

- Married Women's Property Act, 1874

- Workmen's compensation Act, 1923

- Indian Successions Act, 1925

- Immoral Traffic (prevention) Act, 1956

- Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961[96]

- Commission of Sati(Prevention) Act, 1987

- Cinematograph Act, 1952

- Births, Deaths & Marriages Registration Act, 1886

- Minimum Wages Act, 1948

- Prevention of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012

- Child Marriage Restraint Act, 1929

- Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application,1937

- Indecent Representation of Women(Prevention) Act,1986

- ସSpecial Marriage Act)[97]

- Hindu Marriage Act, 1955

- Hindu Successions Act, 1956

- Foreign Marriage Act, 1969

- Family Courts Act, 1984

- Maternity Benefit Act,1861

- Hindu Adoption & Maintenance ACT,1956

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973

- Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act,1971

- National Commission for Women Act, 1990

- Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation and Prevention of Misuse) Act, 199)

- Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005

- Sexual Harassment of Women at Work Place (Prevention, Prohibition & Redressal) Act, 2013[98]

- Indian Divorce Act, 1969

- Equal Remuneration Act, 1976

- Hindu Widows Remarriage Act, 1856

- Muslim women (protection of rights on divorce) Act, 1986

Numerous legal protections have been bestowed on India at the national level since colonial times. However, widespread lack of enforcement has led to violation of laws related to women's status with impunity.

Other concerns

Social opinions

In the wake of several brutal rape attacks in the capital city of Delhi, debates held in other cities revealed that men believed women who dressed provocatively deserved to get raped; many of the correspondents stated women incited men to rape them.[99][100]

Health

The average female life expectancy today in India is low compared to many countries, but it has shown gradual improvement over the years. In many families, especially rural ones, girls and women face nutritional discrimination within the family, and are anaemic and malnourished.[31]

The maternal mortality in India is the 56th highest in the world.[101] 42% of births in the country are supervised in Medical Institution. In rural areas, most of women deliver with the help of women in the family, contradictory to the fact that the unprofessional or unskilled deliverer lacks the knowledge about pregnancy.[31]

Family planning

The average woman living in a rural area in India has little or no control over becoming pregnant. Women, particularly women in rural areas, do not have access to safe and self-controlled methods of contraception. The public health system emphasises permanent methods like sterilisation, or long-term methods like IUDs that do not need follow-up. Sterilization accounts for more than 75% of total contraception, with female sterilisation accounting for almost 95% of all sterilisations.[31]

Sex ratios

India has a highly skewed sex ratio, which is attributed to sex-selective abortion and female infanticide affecting approximately one million female babies per year.[102] In, 2011, government stated India was missing three million girls and there are now 48 less girls per 1,000 boys.[103] Despite this, the government has taken further steps to improve the ratio, and the ratio is reported to have been improved in recent years.[104]

Sanitation

In rural areas, schools have been reported to have gained the improved sanitation facility.[105] Given the existing socio-cultural norms and situation of sanitation in schools, girl students are forced not to relieve themselves in the open unlike boys.[106] Lack of facilities in home forces women to wait for the night to relieve themselves and avoid being seen by others.[107]

In 2011 a "Right to Pee" (as called by the media) campaign began in Mumbai, India's largest city.[108] Women, but not men, have to pay to urinate in Mumbai, despite regulations against this practice. Women have also been sexually assaulted while urinating in fields.[108] Thus, activists have collected more than 50,000 signatures supporting their demands that the local government stop charging women to urinate, build more toilets, keep them clean, provide sanitary napkins and a trash can, and hire female attendants.[108] In response, city officials have agreed to build hundreds of public toilets for women in Mumbai, and some local legislators are now promising to build toilets for women in every one of their districts.[108]

Notable Indian women

- Education

- Savitribai Phule was a social reformer. Along with her husband, Mahatma Jotiba Phule, she played an important role in improving women's rights in India during British Rule. Savitribai was the first female teacher of the first women's school in India and also considered to be the pioneer of modern Marathi poetry. In 1852 she opened a school for Untouchable caste girls.

- Arts and entertainment

- Singers and vocalists such as M.S. Subbulakshmi, Gangubai Hangal, Lata Mangeshkar, Asha Bhosle and others are widely revered in India. Anjolie Ela Menon is a famous painter.

- Sports

- Although in general the women's sports scenario in India is not very good, some Indian women have made notable achievements in the field. Some famous female sportspersons in Indian include P. T. Usha (athletics), J. J. Shobha (athletics), Kunjarani Devi (weightlifting), Diana Edulji (cricket), Saina Nehwal (badminton), Koneru Hampi (chess) and Sania Mirza (tennis). Female Olympic medalists from India include weightlifter Karnam Malleswari (bronze, 2000), Saina Nehwal (bronze, 2012), and boxer Mary Kom (bronze, 2012).

- Politics

- Through the Panchayat Raj institutions, over a million women have actively entered political life in India.[54] As per the 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendment Acts, all local elected bodies reserve one-third of their seats for women. Although the percentages of women in various levels of political activity has risen considerably, women are still under-represented in governance and decisionmaking positions.[31]

- Literature

- Many women writers are prominent in Indian literature as poets and story writers, such as Sarojini Naidu, Kamala Surayya, Shobha De, Arundhati Roy, and Anita Desai. Sarojini Naidu is called the nightingale of India. Arundhati Roy won the Booker Prize (Man Booker Prize) for her novel The God of Small Things.

- Government Servants

- Indian Railways: Surekha Yadav, Samata Kumari, Preeti Kumari, C.V.Thilagavathi, S.Satyavathi, Matrubhoomi - MMTS Ladies Special Driver, Mumtaz Kazi.

See also

|

General:

References

- ^ Bibhudatta Pradhan (19 July 2007). "Patil Poised to Become India's First Female President". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- ^ "The Global Gender Gap Report 2013" (PDF). World Economic Forum. pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b "Rajya Sabha passes Women's Reservation Bill". Chennai, India: The Hindu. 10 March 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ Jayapalan (2001). Indian society and social institutions. Atlantic Publishers & Distri. p. 145. ISBN 978-81-7156-925-0.

- ^ a b c d e "Women in History". National Resource Center for Women. Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ Sudha G Tilak. "Crimes against women increase in India - Features". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Deepak K Upreti (14 October 2011). "India is home of unspeakable crimes against women". Deccanherald.com. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Atrocities against women on the rise March 2013

- ^ a b Mishra, R. C. (2006). Towards Gender Equality. Authorspress. ISBN 81-7273-306-2.

- ^ Varttika by Katyayana, 125, 2477

- ^ Comments to Ashtadhyayi 3.3.21 and 4.1.14 by Patanjali

- ^ R. C. Majumdar and A. D. Pusalker (editors): The history and culture of the Indian people. Volume I, The Vedic age. Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan 1951, p.394

- ^ "Vedic Women: Loving, Learned, Lucky!". Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ Shweta Singh (2009). Examining the Dharma Driven Identity of Women: Mahabharata’s Kunti - In The Woman Question in the Contemporary Indian English Women Writings, Ed. Indu Swami, Sarup: Delhi.

- ^ The perfect wife: strIdharmapaddhati (guide to the duties of women) by Tryambakayajvan (trans. Julia Leslie ), Penguin 1995 ISBN 0-14-043598-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "InfoChange women: Background & Perspective". Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ a b c Jyotsana Kamat (January 2006). "Status of Women in Medieval Karnataka". Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ "Heart of Hinduism Other Social Issues". Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ "The Danger of Gender: Caste, Class and Gender in Contemporary Indian Women's Writing" by Clara Nubile, p.9

- ^ Vimla Dang (19 June 1998). "Feudal mindset still dogs women's struggle". The Tribune. Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ "The Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987". Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ "Honour, status & polity" by Pratibha Jain, Saṅgītā Śarmā.

- ^ K. L. Kamat (19 December 2006). "The Yellamma Cult". Retrieved 25 December 2006.

- ^ Devadasi. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 July 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Dubois, Jean Antoine and Beauchamp, Henry King, Hindu manners, customs, and ceremonies, Clarendon press, 1897

- ^ "Saraswati English Plus", p.47

- ^ "Status of Women in India" by Shobana Nelasco, p.11

- ^ Ambassador of Hindu Muslim Unity, Ian Bryant Wells

- ^ a b Jyotsna Kamat (19 December 2006). "Gandhi and Status of Women". Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ "Oxford University's famous south Asian graduates#Indira Gandhi". BBc News. 5 May 2010.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Kalyani Menon-Sen, A. K. Shiva Kumar (2001). "Women in India: How Free? How Equal?". United Nations. Archived from the original on 11 September 2006. Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ Victoria A. Velkoff and Arjun Adlakha (October 1998). "Women of the World: Women's Health in India" (PDF). U.S. Department of Commerce. Retrieved 25 December 2006.

- ^ "National Policy For The Empowerment Of Women (2001)". Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ "OneWorld South Asia News: Imrana". Retrieved 25 December 2006.

- ^ "India is fourth most dangerous place in the world for women: Poll : Invisible India, News - India Today". Indiatoday.intoday.in. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ Owen Bowcott (15 June 2011). "Afghanistan worst place in the world for women, but India in top five | World news". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ Baldwin, Katherine (13 June 2012). "Canada best G20 country to be a woman, India worst - TrustLaw poll". trust.org. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ "FeministsIndiaIndia ranked worst country for women- Indian Feminists Writing, Activism, Feminism, Women's Groups". 13 June 2012.

- ^ "Rajya Sabha passes Women's Reservation Bill". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 10 March 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ "Mumbai Police History". Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ "High Court of Kerala: Former Chief Justices / Judges". Archived from the original on 14 December 2006. Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ "Kiran Bedi Of India Appointed Civilian Police Adviser". Retrieved 25 December 2006.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Army'S First Lady Cadet Looks Back". Archived from the original on 5 February 2007. Retrieved 30 March 2007.

- ^ "Hindu Red Dot". snopes.com. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ^ a b c "Asia's women in agriculture, environment and rural production: India". Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ Singh, S. (2007). Schooling Girls and the Gender and Development Paradigm: Quest for an Appropriate Framework for Women’s Education. Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences, 2(3), 1-12.

- ^ Comparing Costs & Outcomes of Formal & Non-Formal Education programs for Girls in Uttar Pradesh

- ^ Victoria A. Velkoff (October 1998). "Women of the World: Women's Education in India" (PDF). U.S. Department of Commerce. Retrieved 25 December 2006.

- ^ a b "Women of India: Frequently Asked Questions". 19 December 2006. Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ Singh, S., & Hoge, G. (2010). Debating Outcomes for ‘Working’ Women – Illustration from India, The Journal of Poverty, 14 (2), 197-215

- ^ India's Most Powerful Businesswomen. Forbes.com.

- ^ Advani, Abhishek (17 November 2009). "JP Morgan's India CEO". Forbes. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ^ a b Carol S. Coonrod (June 1998). "Chronic Hunger and the Status of Women in India". Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ "India country data - Women, Business and the Law - World Bank Group". Wbl.worldbank.org. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ^ "THE HINDU SUCCESSION (AMENDMENT) ACT, 2005". Indiacode.nic.in. 5 September 2005. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ^ "The Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act". May 1986. Archived from the original on 27 December 2007. Retrieved 14 February 2008.

- ^ Crime in India 2012 Statistics, National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt of India, Table 5.1, page 385.

- ^ Intimate Partner Violence, 1993–2010, Bureau of Justice Statistics, US Department of Justice, table on page 10.

- ^ Reuters, Thomas (2011-08-13). "The World's 5 Most Dangerous Countries For Women: Thomson Reuters Foundation Survey". Retrieved June 2011.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Lakshmibai, Gayatri (13 August 2011). "The woman who conquered an acid attack". Retrieved 22 August 2007.

- ^ Carney, Scott (22 August 2007). "Acid Attacks on Women in India". Archived from the original on 24 August 2007. Retrieved 22 August 2007.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Nadar, Ganesh (11 July 2011). "The woman who conquered an acid attack". Retrieved 22 August 2007.

- ^ India's acid victims demand justice, BBC News, 9 April 2008

- ^ "Child marriages targeted in India". BBC News. 24 October 2001.

- ^ http://www.unicef.org/sowc09/docs/SOWC09_Table_9.pdf

- ^ "40 p.c. child marriages in India: UNICEF". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 18 January 2009.

- ^ Ganguly, Sumit. "India's Shame". The Diplomat. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ Chowdhury, Renuka (26 October 2006). "India tackles domestic violence". BBC.

- ^ a b "India tackles domestic violence". BBC News. 27 October 2006. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ Mahapatro, Meerambika; Gupta, R N; Gupta, Vinay K (26 August 2014). "Control and Support Models of Help-Seeking Behavior in Women Experiencing Domestic Violence in India". Violence and Victims. 29 (3): 464–475.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Mahapatro, Meerambika; Gupta, R N; Gupta, Vinay K (26 August 2014). "Control and Support Models of Help-Seeking Behavior in Women Experiencing Domestic Violence in India". Violence and Victims. 29 (3): 464–475.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Mahapatro, Meerambika; Gupta, R N; Gupta, Vinay K (26 August 2014). "Control and Support Models of Help-Seeking Behavior in Women Experiencing Domestic Violence in India". Violence and Victims. 29 (3): 464–475.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Mahapatro, Meerambika; Gupta, R N; Gupta, Vinay K (26 August 2014). "Control and Support Models of Help-Seeking Behavior in Women Experiencing Domestic Violence in India". Violence and Victims. 29 (3): 464–475.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Mahapatro, Meerambika; Gupta, R N; Gupta, Vinay K (26 August 2014). "Control and Support Models of Help-Seeking Behavior in Women Experiencing Domestic Violence in India". Violence and Victims. 29 (3): 464–475.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Mahapatro, Meerambika; Gupta, R N; Gupta, Vinay K (26 August 2014). "Control and Support Models of Help-Seeking Behavior in Women Experiencing Domestic Violence in India". Violence and Victims. 29 (3): 464–475.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "The Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961". Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ "The Dowry Prohibition (maintenance of lists of presents to the bride and bridegroom) rules, 1985". Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ Kitchen fires Kill Indian Brides with Inadequate Dowry, 23 July 1997, New Delhi, UPI

- ^ "India's lost daughters". Amelia Gentleman in New York Times. 9 January 2006. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ "India's lost daughters". Amelia Gentleman in New York Times. 9 January 2006. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ a b Kumar, Radha (1993). The History of Doing: An Account of Women's Rights and Feminism in India. Zubaan. p. 128. ISBN 978-8185107769.

- ^ "India's women: Rape and murder in Delhi". Economist.com. 5 January 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ « The Irrationality of Rationing (25 January 2013). "Lies, Damned Lies, Rape, and Statistics". Messy Matters. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schmalleger, John Humphrey, Frank. Deviant behavior (2nd ed. ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 252. ISBN 0763797731.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mohanty, Suchitra (6 January 2013). "Indian rape victim's father says he wants her named | Reuters". In.reuters.com. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ "Rape statistics around the world". Indiatribune.com. 11 September 2012. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ "Rape statistics around the world". Indiatribune.com. 11 September 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ "http://www.arabnews.com/indian-student-gang-raped-thrown-bus-new-delhi". AFP. 17 December 2012.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title=|url=(help) - ^ Meenakshi Ganguly, South Asia director (29 December 2012). "India: Rape Victim's Death Demands Action | Human Rights Watch". Hrw.org. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ "The Indecent Representation of Women (Prohibition) Act, 1987". Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ India Supreme Court investigates ex-judge for sexual harassment12 November 2013

- ^ "The Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956". Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- ^ "Guardians and Wards Act"Wcd.nic.in

- ^ "Indian Evidence Act"Lawnotes.in

- ^ "Dowry Prohibition Act"

- ^ "Special Marriage Act"Indiankanoon

- ^ [2]

- ^ Gethin Chamberlain Baga, Goa (24 March 2013). "'If girls look sexy, boys will rape.' Is this what Indian men really believe? | World news | The Observer". London: Guardian. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ "Why young Indian men rationalize rape as something expected". Taipei Times. 1 February 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ CIA factbook. Country Comparison :: Maternal Mortality Rate

- ^ "Indian girl Infanticide-Female Fetocide: 1 million girls killed before or after birth per year". Rupee News. 28 September 2009. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ PTI (9 October 2012). "News / National : India loses 3 million girls in infanticide". Chennai, India: The Hindu. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ "Sex ratio in India showing improvement". Nationalturk.com. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/india_55555.html

- ^ Bisoee, Animesh (14 December 2013). "School minus loo is public urinal - Girls answer natures call outside campus; slum dwellers defecate on playground". The Telegraph. Calcutta, India.

{{cite news}}: C1 control character in|title=at position 56 (help) - ^ http://www.unicef.org/india/wes.html

- ^ a b c d Yardley, Jim (14 June 2012). "In India, a Campaign Against Restroom Injustice". The New York Times.

Further reading

- Clarisse Bader (2001) [1925]. Women in Ancient India. Trubner's Oriental Series, Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-24489-3.

- Kumar, Radha (1997). History of Doing: An Illustrated Account of Movements for Women's Rights and Feminism in India, 1800-1990. Zubaan. ISBN 8185107769.

External links

- An Automated Geo tagged live feed tracking Violence on Women in India

- An Automated Twitter Account tracking Violence on Women in India

- "Nothing to Go Back To - The Fate of the Widows of Vrindavan, India" WNN - Women News Network

- National Commission for Women

- Ministry of Women & Child Development

- South Asian Women's NETwork (SAWNET)

- Women of the Mughal Dynasty

- Indian women & Dowry law misuse

- Women of India

- 21 Top Women CEOs of India

- The Bangle Code - fiction related to unwritten social rules that Indian women have to deal with

- A global network for Indian Women

- CRS Center for Social Research

- Ewomen from SRCAC-FSCW in Lucknow