Clean Copy (talk | contribs) just a lead! |

Clean Copy (talk | contribs) removed Category:Pseudoscience using HotCat (controversial category) |

||

| Line 441: | Line 441: | ||

[[Category:Pedagogy]] |

[[Category:Pedagogy]] |

||

[[Category:School types]] |

[[Category:School types]] |

||

[[Category:Pseudoscience]] |

|||

[[Category:Waldorf education| ]] |

[[Category:Waldorf education| ]] |

||

Revision as of 14:44, 10 March 2013

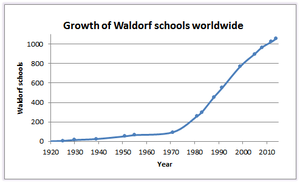

Waldorf education (also known as Steiner education) is a humanistic approach to pedagogy based on the educational philosophy of the Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner, the founder of anthroposophy. The first Waldorf school was founded in 1919 to serve the children of employees at the Waldorf-Astoria cigarette factory in Stuttgart, Germany. As of 2012, there were 1,025 independent Waldorf schools,[1] 2,000 kindergartens[2] and 530 centers for special education,[3] located in 60 countries. There are also Waldorf-based public (state) schools,[4] charter schools, and homeschooling[5] environments.

Waldorf pedagogy distinguishes three broad stages in child development, each lasting approximately seven years. The early years education focuses on providing practical, hands-on activities and environments that encourage creative play. In the elementary school, the emphasis is on developing pupils' artistic expression and social capacities, fostering both creative and analytical modes of understanding. Secondary education focuses on developing critical understanding and fostering idealism. Throughout, the approach stresses the role of the imagination in learning and places a strong value on integrating academic, practical and artistic pursuits.

The educational philosophy's overarching goals are intended to provide young people the basis upon which to develop into free, morally responsible, and integrated individuals equipped with a high degree of social competence. Teachers generally use formative (qualitative) rather than summative (quantitative) assessment methods, particularly in the pre-adolescent years. The schools have a high degree of autonomy to decide how best to construct their curricula and govern themselves.

Waldorf education is the largest independent alternative education movement in the world.[6] In central Europe, where most of the schools are located,[1] the Waldorf approach has achieved general acceptance as a model of alternative education.[7][8] Waldorf education and Waldorf teacher training are funded through the state in many European countries. Public funding of Waldorf schools in the United States and the United Kingdom has been controversial. In 2012, objections to public funding of Waldorf schools in the United Kingdom were made on the grounds that the schools teach pseudoscience and promote homeopathy. Controversies have also occurred in which Waldorf education has been accused of discouraging immunization. The Waldorf movement has said that concerns over its stance on these matters are unfounded.

| Part of a series on |

| Anthroposophy |

|---|

| General |

| Anthroposophically inspired work |

| Philosophy |

Origins and history

Rudolf Steiner, the founder of Waldorf education,[10]: 381 had been a private tutor and a lecturer on history at the Berlin Arbeiterbildungsschule,[11] an educational initiative for working class adults.[12] He began to articulate his ideas on education in public lectures,[13] culminating in a 1907 essay on The Education of the Child which included his first comprehensive description of the three major phases of childhood. His conception of education was deeply influenced by the Herbartian pedagogy prominent in Europe during the late nineteenth century.[14]

The first school based upon these principles was opened in 1919 in response to a request by Emil Molt, the owner and managing director of the Waldorf-Astoria Cigarette Company in Stuttgart, Germany, to serve the children of employees of the factory. This is the source of the name Waldorf, which is now trademarked for use in association with the educational method. The Stuttgart school grew rapidly and soon the majority of pupils were from families not connected with the company.[15] The school was the first comprehensive school in Germany, serving children from all social classes, abilities and interests.[16] Because of legal requirements of German schools, Steiner's early German schools had to deviate from his ideal in order to be acceptable; however this achieved one of Steiner's objectives – allowing students to be able to transfer between Waldorf, and conventional state schools.[10]: 393 Waldorf schools have been always been co-educational.[17][18]

Schools began to open in other locations, including Hamburg, The Hague, and Basel. Waldorf education became more widely known in Britain in 1922 through lectures Steiner gave on education at a conference at Oxford University.[2] The first school in England, now Michael Hall school, was founded in 1925; the first in the USA, the Rudolf Steiner School in New York City, in 1928. By the late 1930s, numerous schools inspired by the original school or its pedagogical principles had been founded in Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Norway, Austria, Hungary, the USA, and the UK. Though political interference from the Nazi regime limited and ultimately closed most Waldorf schools in Europe, with the exception of the British and some Dutch schools, the affected schools were reopened after the Second World War.[19] The 1970s and 80s saw a rapid expansion of the schools worldwide; in North America, the count of Waldorf schools went from 12 in 1968[20] to over 200 independent[1] and charter[21] schools today.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Waldorf schools began to proliferate in Central and Eastern Europe. Most recently, many schools are opening in Asia, especially in China. There are currently over 1,000 independent Waldorf Schools worldwide.[1]

Educational Theory

Anthroposophical basis

Rudolf Steiner's ideas on education grew out of his simultaneously emerging views on individual development.[13] These are part of his larger spiritual philosophy, Anthroposophy, which regards the human being as composed of body, soul, and spirit.

Steiner's educational ideas closely follow modern "common sense" educational theory since Comenius and Pestalozzi.[13] While anthroposophy underpins Waldorf schools' organisation, curriculum design and pedagogical approach (and frequently, the design of the buildings, as well as pupil and teacher health and diet), it is explicitly not taught within the school curriculum.[22][23]: 6

The curriculum of Waldorf teacher education programs includes both pedagogical texts and other anthroposophical works by Steiner.[24] As in a Waldorf school, teacher training colleges and institutes attempt to develop the academic, practical and artistic capacities of their students. For example, art, music, poetry, and handwork are integrated into the adult educational curriculum and students are expected to produce not only essays, workbooks and lesson plans but drawings, paintings, theatrical performances and other output that demonstrates their ability to work across all areas of the curriculum.[25]

Educational Scholar Heiner Ullrich suggests that critics tend to focus on what they see as Steiner's "occult neo-mythology of education" and to fear the risks of indoctrination in a worldview school, but lose an "unprejudiced view of the varied practice of the Steiner schools."[13]

Developmental Approach

The structure of the education follows Steiner's theories of child development, which divides childhood into three developmental stages, each with its own learning requirements.[26] These stages, each of which lasts approximately seven years, are broadly similar to those described by Piaget.[27][10]: 402 Waldorf pedagogical theory describes these stages as follows:

During the first developmental stage (under 7 years old), children primarily learn through empathy, and their desire to engage with the world is therefore stimulated by participating in a range of practical activities. The educator's task is to present worthwhile models of action.[10]: 389 Educational scholar Heiner Ullrich sums up the motto for Waldorf early years education as: The world is good.[14]

In the second stage, between ages 7–14, children primarily learn through materials appealing to their feelings and imagination. Story-telling and artistic work are used to convey and depict academic content so that students will connect more deeply with the subject matter they encounter. The educator's task is to present a role model children will naturally want to follow, gaining authority through fostering rapport.[10]: 390 Ullrich sums up the instructional motto for the elementary years as: The world is beautiful.[14]

In the third developmental stage (14 and up), children primarily learn through their own thinking and judgment. They are asked to understand abstract material and are expected to have sufficient foundation and maturity to form conclusions using their own judgment.[10]: 391 Ullrich sums up the instructional motto for the secondary school years as: The world is true.[14]

Steiner also described sub-stages of these larger developmental steps.[28]

The developmental approach used in the Waldorf schools is designed to awaken – and ideally balance – the "physical, behavioral, emotional, cognitive, social, and spiritual" aspects of the developing person,[23] developing thinking that includes a creative as well as an analytic component.[23]: 28 A 2005 overview of research studies concluded that research results suggest that Waldorf schools successfully develop "creative, social and other capabilities important in the holistic growth of the person," but that more research is needed to confirm the generally small scale studies conducted to date.[23]: 39

Four temperaments

Steiner considered children's cognitive, emotional and behavioral development to be interlinked.[29] When students in a Waldorf school are grouped, it is generally not by a singular focus on their academic abilities.[30] Instead Steiner adapted the idea of the classic four temperaments - melancholic, sanguine, phlegmatic and choleric – for pedagogical use in the elementary years.[31] Steiner indicated that teaching should be differentiated to accommodate the different needs that these psychophysical types[14]represent. For example, "cholerics are risk takers, plegmatics take things calmly, melancholics are sensitive or introverted, and sanguines take things lightly or flippantly."[32] Today Waldorf teachers may work with the notion of temperaments to differentiate their instruction. Seating charts and class activities may be planned around the temperaments of the students[33] but this is often not readily apparent to observers.[34] Steiner also believed that teachers must consider their own temperament and be prepared to work with it positively in the classroom,[35] that temperament is emergent in children,[19] and that most people will reveal a combination of temperaments rather than a pure single type.[31]

Assessment

The schools primarily assess students through reports on individual academic progress and personal development. The emphasis is on characterization through qualitative description. Pupils' progress is primarily evaluated through portfolio work in academic blocks and discussion of pupils in teacher conferences. Standardized tests are rare, with the exception of examinations necessary for college entry taken during the secondary school years.[14]: 150, 186 Letter grades are generally not given until students enter high school at 14–15 years. Pupils are not normally asked to repeat years of education,[36] as the educational emphasis is on children's holistic development, not solely their academic progress.[14]

Educational Practice

Pre-school and kindergarten: birth to age 6/7

-

Waldorf dollA Waldorf doll, as might be used in classroom play

-

An autumn nature table at a Waldorf school in Australia

The Waldorf approach to early childhood education is largely experiential and sensory-based.[37] The emphasis is on providing worthwhile practical activities for children to imitate, allowing them to learn through example.[38][39] The schedule is oriented around an "organic" and well-ordered daily routine that emphasizes rhythmic experience of the day, week, month, and seasons.[14] Extensive time is given for guided free play in a classroom environment that is homelike, includes natural materials, and provides examples of productive work in which children can take part.[28] Outdoor play periods are also generally included in the school day, providing children with experiences of nature, weather and the seasons of the year.[14]

Oral language is developed with songs, poems, movement games and daily stories – typically a fairytale is recited by the teacher, often by heart.[27] Aids to development via play generally consist of simple materials drawn from natural sources that can be transformed imaginatively to fit a wide variety of purposes. Waldorf dolls are intentionally made simple in order to allow playing children to employ and strengthen their imagination and creativity. Waldorf schools generally discourage kindergarten and lower grade pupils against media influences such as television and computers.[37] Educational scholars Philip and Glenys Woods say this is done "not from an anti-technology bias but because its use at a younger age is understood to be out of harmony with children's developmental needs." In the younger years, focus is placed on the importance of physical activity and development.[40] Steiner believed that people use their entire body in order to learn and that engaging young children in abstract, intellectual activity too early would adversely affect their growth and development. He believed that the result of such early intellectual instruction would manifest itself later in life in the form of disease. [10]: 389 The lexical and sub-lexical aspects of learning to read are not taught in Waldorf kindergartens and are instead taught by the first grade teacher when pupils are around seven years of age.

Pre-school and kindergarten programs generally include seasonal festivals drawn from a variety of traditions, with attention placed on the traditions brought forth from the community. Waldorf schools in the Western Hemisphere have traditionally celebrated Christian festivals.[41]

Transition to formal academic learning

Waldorf pedagogical theory considers that during the first seven years of life, children learn best by being immersed in an environment they can learn from through unselfconscious imitation. In the second-seven year period, the child is ready for formal learning. The transition has a number of markers, one of which is the loss of the baby teeth,[13] which Steiner believed came about concurrently with a growing independence of character, temperament, habits, and memory.[10]: 389

Elementary education: age 6/7 to 14

During the elementary school years (age 7–14), the approach emphasizes cultivating children's emotional life and imagination. The unusually broad core curriculum, which includes language arts, history, mythology, general knowledge, geography, geology, algebra, geometry, mineralogy, biology, astronomy, physics, chemistry, and nutrition, "among others"[14] is introduced imaginatively through stories and creative presentations. Academic instruction is integrated with a multi-disciplinary artistic curriculum that includes visual arts, drama, artistic movement (eurythmy), vocal and instrumental music, and crafts.[28][42][43]

There is little reliance on standardized textbooks.[13] The school day generally starts with a one-and-a-half to two-hour, cognitively-oriented academic lesson that focuses on a single theme over the course of about a month's time.[14]: 145 This typically begins with an introduction that may include singing, instrumental music, and recitations of poetry, generally including a verse written by Steiner for the start of a school day.[41]

In the elementary years, each class has a core teacher for academic subjects who is meant to guide and stimulate pupils by exercising creative, loving authority, providing consistently supportive models of personal development both through personal example and through stories of "spiritual 'role models' from culture and history which may have an effect on the children's fantasy and imaginations through their symbolism and allegory."[14]

In a Waldorf school, the class teacher is normally expected to teach a group of children for several years – a practice known as "looping". Although the practice of "looping" has increased in both public and private schools, it is still considered an innovative approach to instructional design.[44] Looping has both advantages in the long-term relationships thus established and disadvantages in the challenge to teachers, who face a new curriculum each year.[37] Beginning from first grade, additional teachers teach subjects such as music, crafts, movement, and two foreign languages from complementary language families[10] (in English-speaking countries often German and either Spanish or French), all of which are central to the curriculum throughout the elementary school years.

While emphasizing the value of the class teacher as a personal mentor for students, especially in the early years, Ullrich documented problems with the continuation of the class teacher role into the middle school years (grades 7 and 8, ages 12–14). Noting that there is a danger of any authority figure limiting students enthusiasm for inquiry and assertion of autonomy, he emphasized the need for teachers to encourage independent thought and explanatory discussion in these years, and cited approvingly a number of schools where the class teacher accompanies the class for six years, after which specialist teachers play a significantly greater role.[14]: 222

Waldorf elementary education allows for individual variations in the pace of learning, based upon the expectation that a child will grasp a concept or achieve a skill when he or she is ready.[19] Cooperation takes priority over competition.[45] This approach also extends to physical education; competitive team sports are introduced in upper grades.[37]

Secondary education: age 14 and up

In most Waldorf schools, pupils enter secondary education when they are about fourteen years old. Secondary education is provided by specialist teachers for each subject. The education focuses much more strongly on academic subjects, though students normally continue to take courses in art, music, and crafts.[14] The curriculum is structured to foster pupils' intellectual understanding, independent judgment, and ethical ideals such as social responsibility, aiming to meet the developing capacity for abstract thought and conceptual judgment.[28][38]

The overarching goals are to provide young people the basis on which to develop into free, morally responsible[46][23] and integrated individuals,[43][47][48] with the aim of helping young people "go out into the world as free, independent and creative beings".[49]

Spiral Curriculum

Though most Waldorf schools are autonomous institutions not required to follow a prescribed curriculum, there are widely agreed guidelines for the Waldorf curriculum, supported by the schools' common principles.[40]

The main academic subjects are introduced through blocks lasting for several weeks consisting of daily classes that begin the day and last up to two hours long.[23]: 18 These lesson blocks are horizontally integrated at each grade level in that the topic of the block will be infused into many of the activities of the classroom and vertically integrated in that each subject will be revisited over the course of the education with increasing complexity as students develop their skills, reasoning capacities and individual sense of self. This has been described as a spiral curriculum.[50]

The Waldorf curriculum has always incorporated multiple intelligences.[51]

There are a few subjects largely unique to the Waldorf schools. Foremost among these is Eurythmy, a movement art usually accompanying spoken texts or music which includes elements of role play and dance and is designed to provide individuals and classes with a "sense of integration and harmony".[45] Ernest Boyer, former president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching has noted how the arts generally play a significant role throughout Waldorf education, and commended this as a model for other schools to follow.[52]

Spirituality

According to McDermott et al, Waldorf education is "infused with spirituality" throughout the curriculum,[45] and can include a wide range of religious traditions without favoring any single tradition.[45] Waldorf theories and practices are modified from their European and Christian roots to meet the historical and cultural traditions of the local community.[53] Examples of such adaptation include the Waldorf schools in Israel and Japan, which celebrate festivals of their particular spiritual heritage, and classes in the Milwaukee Urban Waldorf school, which have adopted traditions with African American and Native American heritages.[45] Such festivals, as well as assemblies generally, play an important role in Waldorf schools and are generally celebrated by showing students' work.

Social engagement

Waldorf schools seek to cultivate pupils' sense of social responsibility.[28][54][55][56] and studies suggest that this is successful.[13]: 190 [23]: 4 A comparison of Waldorf and state schools in Australia found that Waldorf pupils "more frequently expressed interest and engagement in social and moral questions and showed more positive attitudes."[57] A study by Jennifer Gidley of pupils drawn from the Waldorf schools of three Australian cities found that "students demonstrated a strong sense of activism and self-confidence and felt empowered to create their own preferred futures".[58] Reports from small-scale studies suggest that there is lower levels of harassment and bullying in Waldorf schools.[23]: 29

Waldorf schools build close learning communities, founded on the shared values of its members,[23]: 17 in ways that can lead to transformative learning experiences that allow all participants, including parents, to become more aware of their own individual path,[35]: 238 [23]: 5, 17, 32, 40 but which at times also risk becoming exclusive.[13]: 167, 207

Betty Reardon, a professor and peace researcher, suggests that Waldorf schools provide an example of schools that follow a philosophy based on peace and tolerance.[59]

Intercultural links in socially polarized communities

Waldorf schools have linked polarized communities in a variety of settings.

- Under the apartheid regime in South Africa, the Waldorf school was one of the few schools in which children of both races attended the same classes, despite the ensuing loss of state aid. A Waldorf training college in Cape Town, the Novalis Institute, was referenced during UNESCO’s Year of Tolerance for being an organization that was working towards reconciliation in South Africa.[59]

- In Israel, the Harduf Kibbutz Waldorf school includes both Jewish and Arab faculty and students and has extensive contact with the surrounding Arab communities;[60] it also runs an Arab-language Waldorf teacher training.[61] In addition, a joint Arab-Jewish Waldorf kindergarten was founded in Hilf (near Haifa) in 2005.[62]

- In Brazil, a Waldorf teacher, Ute Craemer, founded a community service organization providing childcare, vocational training and work, social services including health care, and Waldorf education to more than 1,000 residents of poverty-stricken areas (Favelas) of São Paulo.[63]

- In Nepal, the Tashi Waldorf School in the outskirts of Kathmandu teaches mainly disadvantaged children from a wide variety of cultural backgrounds.[64] It was founded in 1999 and is run by Nepalese staff. In addition, in the southwest Kathmandu Valley a foundation founded by Krishna Gurung provides underprivileged, disabled and poor adults with work on a biodynamic farm and provides a Waldorf school for their children.[65]

- The T. E. Mathews Community School in Yuba County, California serves high-risk juvenile offenders, many of whom have learning disabilities. The school switched to Waldorf methods in the 1990s. A 1999 study of the school found that students had "improved attitudes toward learning, better social interaction and excellent academic progress."[66][67] This study identified the integration of the arts "into every curriculum unit and almost every classroom activity" of the school as the most effective tool to help students overcome patterns of failure. The study also found significant improvements in reading and math scores, student participation, focus, openness and enthusiasm, as well as emotional stability, civility of interaction and tenacity.[67]

Waldorf education also has links with UNESCO. The Friends of Waldorf Education is an affiliated organization, the main purpose of which is to support, develop infrastructure, finance and provide advice to the Waldorf movement world-wide. In 2008, 24 Waldorf schools in 15 countries were members of the UNESCO Associated Schools Project Network.[68]

Governance

One of Waldorf education's central premises is that all educational and cultural institutions should be self-governing and should grant teachers a high degree of creative autonomy within the school;[42][13]: 143 this is based upon the conviction that a holistic approach to education aiming at the development of free individuals can only be successful when based on a school form that expresses these same principles.[69] Most Waldorf schools are not directed by a principal or head teacher, but rather by a number of groups, including:

- The college of teachers, who decide on pedagogical issues, normally on the basis of consensus. This group is usually open to full-time teachers who have been with the school for a prescribed period of time. Each school is accordingly unique in its approach, as it may act solely on the basis of the decisions of the college of teachers to set policy or other actions pertaining to the school and its students.[41]

- The board of trustees, who decide on governance issues, especially those relating to school finances and legal issues, including formulating strategic plans and central policies.[70]

Parents are encouraged to take an active part in non-curricular aspects of school life.[45] Waldorf schools have been found to create effective adult learning communities.[71]

Reviewing Joseph Kahne's book, Reframing Educational Policy: Democracy, Community and the Individual, Holmes (2000) contrasts the communities formed by supporters of Waldorf education with those formed in mainstream education, which Kahne sees merely as "residential areas partitioned by bureaucratic authorities for educational purposes" – in contrast, supporters of Steiner's Waldorf ideas are listed as a "genuine community" alongside fundamentalist Christians and Orthodox Jews.[72]

There are coordinating bodies for Waldorf education at both the national (e.g. the Association of Waldorf Schools of North America and the Steiner Waldorf Schools Fellowship in the UK and Ireland) and international level (e.g. International Association for Waldorf Education and The European Council for Steiner Waldorf Education (ECSWE)). These organizations certify the use of the registered names "Waldorf" and "Steiner school" and offer accreditations, often in conjunction with regional independent school associations.[73]

Evaluations of students progress

Heiner Ullrich, who has written about Waldorf schools extensively since 1991,[74] argues that the schools successfully foster dedication, openness, and a love for other human beings, for nature, and for the inanimate world.[14]: 179 A number of studies of Waldorf education have concluded that the education is "particularly successful in stimulating imaginative thought and creating eager, confident and curious students."[23]: 30 [35]: 241, passim [37] Studies have found that, in comparison to state school pupils, Waldorf students are significantly more enthusiastic about learning, report having more fun and being less bored in school, find their school environment pleasant and supportive, feel individually met, and learn more from school about their personal academic strengths.[75] More than twice as many Waldorf students report having good relationships with teachers. Waldorf pupils also have significantly fewer physical ailments such as headaches, stomach aches, and disrupted sleep.[75]

According to an article in Die Welt, a 2009 PISA study found that, compared to state school students, European Waldorf students are significantly more capable in the sciences.[75]

In a 1996, a study of British and German third- through sixth-grade children found they averaged higher scores on the Torrance Test of Creative Thinking Ability than state-school students[76] A study by Cox and Rolands found that the pupils achieved both more accurate, detailed, and imaginative drawings.[77] A study by Jennifer Gidley found that Waldorf students were able to develop richer and more detailed images, and had more positive views of the future.[78]

Reception

Educational Scholars

In 2000, educational scholar Heiner Ullrich wrote that intensive study of Steiner's pedagogy had been in progress in educational circles in Germany since about 1990 and that that positions were "highly controversial: they range from enthusiastic support to destructive criticism."[13] In 2008, the same scholar wrote that Waldorf schools have "not stirred comparable discussion or controversy....those interested in the Waldorf School today...generally tend to view this school form first and foremost as a representative of internationally recognized models of applied classic reform pedagogy." [14]: 140–141 Professor of Education Bruce Uhrmacher considers Steiner's view on education worthy of investigation for those seeking to improve public schooling, saying the approach serves as a reminder that "holistic education is rooted in a cosmology that posits a fundamental unity to the universe and as such ought to take into account interconnections among the purpose of schooling, the nature of the growing child, and the relationships between the human being and the universe at large", and that a curriculum need not be technocratic, but may equally well be arts-based.[10]: 382, 401

Thomas Nielsen, an assistant professor at the University of Canberra's Education Department, considers the imaginative teaching approaches used in Waldorf education (drama, exploration, storytelling, routine, arts, discussion and empathy) to be effective stimulators of spiritual-aesthetic, intellectual and physical development and recommends these to mainstream educators.[43] Andreas Schleicher, international coordinator of the PISA studies, commented on the "high degree of congruence between what the world demands of people, and what Waldorf schools develop in their pupils", placing a high value on creatively and productively applying knowledge to new realms. This enables "deep learning" that goes beyond studying for the next test.[79] Deborah Meier, principal of Mission Hill School and MacArthur grant recipient, whilst having some "quibbles" about the Waldorf schools, stated: "The adults I know who have come out of Waldorf schools are extraordinary people. That education leaves a strong mark of thoroughness, carefulness, and thoughtfulness."[80]Template error [details]

Robert Peterkin, Director of the Urban Superintendents Program at Harvard's Graduate School of Education and former Superintendent of Milwaukee Public Schools during a period when Milwaukee funded a public Waldorf school, considers Waldorf education a "healing education" whose underlying principles are appropriate for educating all children.[81]

A 2007 German study found that an above-average number of Waldorf students become teachers, doctors, engineers, scholars of the humanities, and scientists.[79] A 2003 study of science education in American Waldorf schools by David Jelinek and Li-Ling Sun found the scientific reasoning of Waldorf school pupils to be superior to that of non-Waldorf students, with the greatest gains in the later years of schooling,[23]: 29

Relationship with mainstream education

A number of national, international and topic-based studies have been made of Waldorf education and its relationship with mainstream education. A UK Department for Education and Skills (DfES) report suggested that each type of school could learn from the other type's strengths: in particular, that state schools could benefit from Waldorf education's early introduction and approach to modern foreign languages; combination of block (class) and subject teaching for younger children; development of speaking and listening through an emphasis on oral work; good pacing of lessons through an emphasis on rhythm; emphasis on child development guiding the curriculum and examinations; approach to art and creativity; attention given to teachers’ reflective activity and heightened awareness (in collective child study for example); and collegial structure of leadership and management, including collegial study. Aspects of mainstream practice which could inform good practice in Waldorf schools included: management skills and ways of improving organizational and administrative efficiency; classroom management; work with secondary-school age children; and assessment and record keeping.[23]

Professor of Education Elliot Eisner sees Waldorf education exemplifying embodied learning and fostering a more balanced educational approach than American public schools achieve.[82] Professor of Comparative Education Hermann Röhrs describes Waldorf education as embodying original pedagogical ideas and presenting exemplary organizational capabilities.[83]

Waldorf education influences the mainstream. In 2000 American state and private schools were described as drawing on Waldorf education – "less in whole than in part" – in expanding numbers.[84] Many elements of Waldorf pedagogy have been used in all Finnish schools for many years.[79]

Reading and literacy

In preliteracy research, the topic of best teaching practice is controversial. Some scholars favor a developmental approach in which formal instruction on reading begins around the age of 6 or 7 and others who argue for literacy instruction to occur in pre-school and kindergarten classrooms, assuming that other activities are taking place as well.[85]

In a discussion on academic kindergartens, professor of child development David Elkind has argued that since "there is no solid research demonstrating that early academic training is superior to (or worse than) the more traditional, hands-on model of early education" educators should defer to developmental approaches that provide young children with ample time and opportunity to explore the natural world on their own terms.[86] Elkind names Rudolf Steiner as one of the "giants of early-childhood development" and describes activities for young children in a Waldorf school as "social," "holistic," and "collaborative," as well as reflecting the principle that "early education must start with the child, not with the subject matter to be taught."[86] In response Grover Whitehurst, educational policy chair at the Brookings Institution, argues the opposite. In his view, the lack of solid research demonstrating the benefits of early academics merely reveals the urgent need for an evidence-based "science of early education." He laments that early education scholarship is "mired in philosophy, in broad theories of the nature of child development, and in practices that spring from appeals to authority," such as Elkind’s praise for those "giants of early-childhood development" whose work reflects Jean Piaget’s insights.[86]

Sebastian Suggate has also performed analysis of the PISA 2007 OECD data from 54 countries and found "no association between school entry age ... and reading achievement at age 15".[87] He also cites a German study[88] of 50 kindergartens that compared children who, at age 5, had spent a year either "academically focused", or "play-arts focused" — in time the two groups became inseparable in reading skill. Suggate concludes that the effects of early reading are like "watering a garden before a rainstorm; the earlier watering is rendered undetectable by the rainstorm, the watering wastes precious water, and the watering detracts the gardener from other important preparatory groundwork."[87]

In 2013, Waldorf kindergartens in the United Kingdom were granted an exemption from and modifications of a number of the government's Early Learning Goals, including the requirement that early childhood programs include a reading and writing curriculum. The exemption was granted on the basis that certain of these goals run counter to Waldorf early childhood education's established principles.[89]

Exposure to Information and Communications Technology (ICT)

Education researchers John Siraj-Blatchford and David Whitebread note that in the United Kingdom, Waldorf schools are granted an exemption by the Department for Education (DfE) from the requirement to teach ICT as part of Foundation Stage education (ages 3–5), writing "there is much to admire in Steiner education and, on balance, our view would be that it is to the credit of the [DfE] that Steiner schools have been recently exempted from the requirement to teach ICT..." [90] In particular, they note that "what is hugely valuable in the Steiner position, of course, is the emphasis on the simplicity of resources and on encouraging children's use of their imagination." Less valuable is what they view as an ideological preference on the part of Waldorf educators for "natural, non-manufactured materials," a preference they find to be "a reaction against the dehumanizing aspects of nineteenth-century industrialization" rather than a "reasoned assessment of twenty-first century children's needs." [90] Siraj-Blatchford and Whitebread's overall perspective emphasizes how the educational value of any new technology must be considered in terms of the opportunities and experiences afforded to children. For this reason, they argue that Waldorf educators' emphasis on simple resources and childrens' own imaginations is actually "not incompatible with the use of ICT." At the same time, they stress that what an educational technology is made out of ought to be irrelevant for evaluating its worth.[90]

In 2007 The Herald reported that in Waldorf schools computers are viewed as being first useful to children in the early teen years, only after they have mastered "fundamental, time-honoured ways of discovering information and learning, such as practical experiments and books".[91]

Science and pseudoscience

Waldorf schools' science teaching is influenced by Goethe's phenomenological approach, treating nature as a meaningful whole from which human beings are not alienated. It emphasizes letting the "phenomena themselves speak", using both a genetic method that develops conceptual understanding out of direct personal experience, and an exemplary method that focuses on in-depth investigation of key examples. A common thread throughout the approach is its "aesthetically rich knowledge formation".[92]

A 2003 study of science education in American Waldorf schools by Jelinek and Sun found the scientific reasoning of Waldorf school pupils to be superior to that of non-Waldorf students, with the greatest gains in the later years of schooling;[23]: 29 Waldorf students achieved better results than the public school students on a non-verbal reasoning test, on a TIMSS assessment (where the Waldorf group results were also higher than the international average), and with part-whole relations, and achieved comparable results on a test of verbal logical reasoning. The study found that most lesson time was spent “asking questions, considering possible answers to questions, noting unexpected phenomena and carefully observing specific phenomena”, while little time was spent comparing students’ perceptions and considering alternative interpretations. The researchers remarked on the Waldorf students’ high degree of enthusiasm for science. They considered the science curriculum for Waldorf schools somewhat old-fashioned and out of date, and critiqued some doubtful scientific material. [93]

A 2009 PISA study found that European Waldorf pupils' ability in science was "far above average".[79] A 2007 study found that an above-average number of German Waldorf students become teachers, doctors, engineers, scholars of the humanities, and scientists.[79]

In 1999 Eugenie Scott, the executive director of the non-profit National Center for Science Education, accused the schools of teaching pseudoscience, saying that "Waldorf science relies upon a religious—certainly a cultish—philosophy" and describing Steiner as a "nut case from the 19th Century". However Arthur Zajonc, a physics professor at Amherst College who cofounded a Waldorf high school, said the schools teach sound science but do not "teach that a particular viewpoint by a particular scientist is 'the truth'. We present it as a hypothesis that they should be critical of." Zajonc added that many Waldorf graduates "have gone on to major in science at Harvard, MIT and other prestigious universities".[24]

In 2008, Stockholm University terminated its Waldorf teacher training courses. In a statement the university said "the courses did not encompass sufficient subject theory and a large part of the subject theory that is included is not founded on any scientific base". The dean, Stefan Nordlund, stated "the syllabus contains literature which conveys scientific inaccuracies that are worse than woolly; they are downright dangerous."[94] Education professor Bo Dahlin criticized the decision for departing from the approach taken by other Scandinavian countries saying "It is remarkable that we in Sweden are unable to allow other perspectives. In Norway and Finland the state has long since financed the education of Waldorf teachers."[95] Stockholm University rector (Vice-Chancellor) Kåre Bremer was reported as saying "The committees do not criticize the Waldorf pedagogy in itself, but the literature which does not meet the university's scientific standards."[96]

In September 2012, an editorial in the Times Educational Supplement reported that concerns were being raised about a curriculum reference book used as a basis for Waldorf science lessons, which "says the model of the heart as a pump is unable to explain 'the sensitivity of the heart to emotions' and promotes homeopathy, which relies on a belief that illness can be fought with a diluted amount of the cause of the illness." The book was also quoted as saying "Darwinism is 'rooted in reductionist thinking and Victorian ethics'". [97]

Edzard Ernst, emeritus professor of complementary medicine, said that Waldorf schools "seem to have an anti-science agenda which is detrimental to progress... the [UK] government makes a grave mistake allowing pseudoscience and anti-science in our education." Richy Thompson, education officer of the British Humanist Association stated, "how can pupils receive a vigorous science education under these circumstances? It is gravely concerning that these schools provide alternative medicines such as homeopathy, thus legitimising belief in cures which do not work." A Department for Education spokeswoman responded: "No state school is allowed to teach homeopathy as scientific fact. We have rigorous criteria for approving free schools. Applicants must demonstrate that they will provide a broad and balanced curriculum." A spokesman from the Steiner Waldorf Schools Fellowship UK responded that it was not the place of any school to "promote" an approach to medicine, either conventional or complementary, and that the book in question was only one of many teaching resources used.[97]

Religion

There are many opinions on the relationship between Waldorf education and religion. In Freda Easton's view, Waldorf schools are "Christian based and theistically oriented",[42] but "are opening in different cultural settings and can adapt to 'a truly pluralistic spirituality'".[23]: 146 Tom Stehlik places Waldorf education in a humanistic tradition, and contrasts it to "value-neutral" secular state schooling systems that he describes as lacking a philosophical basis.[35] Iddo Oberski considers that, though first established within a Western, Christian society, Waldorf education is essentially non-denominational in character.[22] In the United Kingdom, public Waldorf schools are not categorized as "Faith schools".[98]

For Steiner, education was an activity which fosters the human being's connection to the divine and is thus inherently religious.[11]: 1422, 1430 He emphasized the important effect spiritual role models drawn from culture and history have on children's fantasy and imaginations. Ullrich describes Steiner's view as follows: "The strongest impulses can come from religious tales because these may be envisioned through man's position within the world as a whole."[13]: 78

The Association of Waldorf Schools of North America (AWSNA) stated in a 1997 position paper that "Waldorf schools are independent schools that are designed to educate all children, regardless of their cultural or religious backgrounds. The pedagogical method is comprehensive, and, as part of its task, seeks to bring recognition and understanding to any world culture or religion. The Waldorf School, founded in 1919 by Rudolf Steiner, is not part of any church."[99]

In a 1994 article,[100] Dan Dugan and Judy Daar invoked Rudolf Steiner's words to his followers when, struggling against restrictive laws on schooling in 1920s Germany, he had advised "we should be aware that we need to do things, but not inwardly, to achieve at least the minimum of what we want, and that we will need to speak with people while inwardly tweaking their noses."[101] For Dugan and Daar, this was evidence that Steiner had always intended Waldorf education "to attract the general public by systematically concealing the objectives of the schools and the contents of their curriculum". In 1995, one of the article's authors, Dan Dugan, went on to co-found the anti-Waldorf campaigning group PLANS. In 1998, PLANS filed a lawsuit against two California school districts with Waldorf-methods schools, alleging that publicly financed Waldorf-methods schools violated the First, Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution and Article IX of the California Constitution. The court dismissed the case on its merits in 2005 and again after appeal in 2007.[102] The judge's 2010 decision found that the plaintiffs had failed to prove anthroposophy is a religion.[103] In 2012, a higher court affirmed the lower court's 2010 decision for the public schools and the case was dismissed on its merits. The judgement stated that the plaintiff had failed to meet its burden of proof that anthroposophy was a religion, but also that the court was expressing no view as to whether anthroposophy could be considered a religion on the basis of a fuller or more complete record.[104]

Religious classes are a mandatory school offering in some German federal states,[105] whereby each religious denomination provides its own teachers for the Waldorf schools' religion classes; such schools also offer a non-denominational religion class. Religion classes are universally absent from American Waldorf schools.[106]

Racism controversy

In November 2012, BBC News broadcast an item about accusations that the establishment of a state-funded Waldorf School in Frome was a misguided use of public money. The broadcast raised particular concerns about Rudolf Steiner's beliefs, stating he "believed in reincarnation and said it was related to race, with black (schwarz) people being the least spiritually developed, and white (weiß) people the most."[107]

In 2007, the European Council for Steiner Waldorf Education (ECSWE) issued a statement, Waldorf schools against discrimination, which said in part, "Waldorf schools do not select, stratify or discriminate amongst their pupils, but consider all human beings to be free and equal in dignity and rights, independent of ethnicity, national or social origin, gender, language, religion, and political or other convictions. Anthroposophy, upon which Waldorf education is founded, stands firmly against all forms of racism and nationalism."[108]

In 1997, the Association of Waldorf Schools of North America (AWSNA) published a position paper stating that "Waldorf schools are independent schools committed to developing the human potential of each child to its fullest. Admission to the schools is open to everyone, without regard to race, sex, creed, religion, national origin, or ethnicity....It is a fundamental goal of our education to bring students to an understanding and experience of the common humanity of all the world’s peoples, transcending the stereotypes, prejudices, and divisive barriers of classification by sex, race and nationality. We most emphatically reject racism in all its forms, and embrace the principles of common humanity expressed by the founder of Waldorf education, Rudolf Steiner."[99]

Immunization and Student Health

Concerns have been raised about the extent of vaccination in Waldorf schools. The Australian has reported concerns among parents that Australian Waldorf schools have discouraged immunization,[109] and in the United Kingdom the Health Protection Agency categorizes Waldorf schools as "unvaccinated community".[110]

In 2012 John Thomas, a law professor, suggested that Waldorf education's emphasis on individual rights is inconsistent with society's use of vaccination to escape from disease, agreeing that the Waldorf school system "[boasts] a 'strong cultural anti-immunization preference among thought-leaders' in its community". Thomas cited vaccination rates of 23% at a Waldorf school in the San Francisco Bay area, compared to 97% in the surrounding county. He stated that children may "emerge from their school to infect infants, immunocompromised adults, and people whose vaccinations didn't take or have waned, with potentially fatal diseases."[111]

In 2001 the European Council for Steiner Waldorf Education (ECSWE) issued a Statement on the Question of Vaccination which stated "It has come to our attention that uncorroborated statements have appeared purporting opposition to childhood immunisation as the official or tacit policy of Steiner Waldorf School Associations and the institutions they represent. We wish to state unequivocally that opposition to immunisation per se, or resistance to national strategies for childhood immunisation in general, forms no part of our specific educational objectives." The statement goes on to say that "families provide the proper context for such decisions" and "schools themselves are not, nor should they attempt to become, determiners of decisions regarding these matters."[112] The European Council represents Waldorf schools in Europe – approximately 700 of the 1,000 schools world wide.[113]

Notes and references

- ^ a b c d Statistics for Waldorf schools worldwide

- ^ a b Paull, John (2011) Rudolf Steiner and the Oxford Conference: The Birth of Waldorf Education in Britain. European Journal of Educational Studies, 3(1): 53-66.

- ^ Anthroposophical centers for curative education Template:Language icon "Currently, there are about 530 international curative education and social therapy centers, more than 60 training centers and 30 associations in more than 40 countries."

- ^ J. Vasagard, "A different class: the expansion of Steiner schools", Guardian 25 May 2012

- ^ M. L. Stevens, "The Normalisation of Homeschooling in the USA", Evaluation & Research in Education Volume 17, Issue 2-3, 2003 , pp. 90-100

- ^ McGavin, Harvey (11 May 2008). "Making room for Rudolf". TES. Retrieved November, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Gruber, Karl Heinz (1987). "Impact of Plowden in Germany and Austria". Oxford Review of Education. 13 (1): 63.

Catholic or Protestant private schools hardly differ from the state schools, but the anthroposophical Rudolf Steiner or Waldorf schools enjoy enormous popularity. Not following the state school curriculum these (costly) private establishments put more emphasis on individual interests, creative expression and parental involvement. However, there are only few Waldorf schools (sic) and they seem to be a domain of the affluent, education-conscious middle class.

- ^ "The Free Waldorf School inspired by Steiner has not stirred comparable discussion or controversy....those interested in the Waldorf School today, be they pedagogically enthusiastic parents, educational scholars, or politicians responsible for education, generally tend to view this school form first and foremost as a representative of internationally recognized models of applied classic reform pedagogy." Ullrich, Rudolf Steiner, p. 140-141

- ^ Data drawn from Helmut Zander, Anthroposophie in Deutschland, 2 volumes, Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht Verlag, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 9783525554524; Dirk Randall, "Empirische Forschung und Waldorfpädogogik", in H. Paschen (ed.) Erziehungswissenschaftliche Zugänge zur Waldorfpädagogik, 2010 Berlin: Springer 978-3-531-17397-9; "Introduction", Deeper insights in education: the Waldorf approach, Rudolf Steiner Press (December 1983) 978-0880100670. p. vii; L. M. Klasse, Die Waldorfschule und die Grundlagen der Waldorfpädagogik Rudolf Steiners, GRIN Verlag, 2007; Ogletree E J "The Waldorf Schools: An International School System." Headmaster U.S.A., pp8-10 Dec 1979; Heiner Ullrich, Rudolf Steiner, Translated by Janet Duke and Daniel Balestrini, Continuum Library of Educational Thought, v. 11, 2008 ISBN 9780826484192.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Uhrmacher, P. Bruce (Winter, 1995). "Uncommon Schooling: A Historical Look at Rudolf Steiner, Anthroposophy, and Waldorf Education". Curriculum Inquiry. 25 (4): 381–406. doi:10.2307/1180016. JSTOR 1180016.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Zander, Helmut (2007). Anthroposophie in Deutschland. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- ^ Jacobs, Nicholas (1978). "The German Social Democratic Party School in Berlin, 1906-1914". History Workshop. 5: 179–187.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1007/BF02195288, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1007/BF02195288instead. - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Ullrich, Heiner (2008). Rudolf Steiner. London: Continuum International Pub. Group. p. 77. ISBN 9780826484192. Cite error: The named reference "UllrichRS" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Johannes Hemleben, Rudolf Steiner: A documentary biography, Henry Goulden Ltd, ISBN 0-904822-02-8, pp. 121-126 (German edition Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag ISBN 3-499-50079-5).

- ^ Heiner Ullrich (2002). Inge Hansen-Schaberg, Bruno Schonig (ed.). Basiswissen Pädagogik. Reformpädagogische Schulkonzepte Band 6: Waldorf-Pädagogik. Baltmannsweiler: Schneider Verlag Hohengehren. ISBN 3-89676503-5.

- ^ Barnes, Henry (1980). "An Introduction to Waldorf Education". Teachers College Record. 81 (3): 323–336.

- ^ Reinsmith, William A. (31 March 1990). "The Whole in Every Part: Steiner and Waldorf Schooling". The Educational Forum. 54 (1): 79–91. doi:10.1080/00131728909335521.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.2307/1180016, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.2307/1180016instead. - ^ History of Waldorf education

- ^ Malaika Costello-Dougherty, "Waldorf-Inspired Public Schools Are on the Rise", Edutopia

- ^ a b Oberski, Iddo (February 2011). "Rudolf Steiner's philosophy of freedom as a basis for spiritual education?". International Journal of Children's Spirituality. 16 (1): 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Woods, Philip (2005). Steiner Schools in England (PDF). UK Department for Education and Skills. ISBN 1 84478 495 9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Haynes, Dion (September 20, 1999). "Waldorf School Critics Wary Of Religious Aspect". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Oberski, Iddo (2007). "Validating a Steiner-Waldorf teacher education programme". Teaching in Higher Education. 12 (1): 135–139.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Thomas Armstrong, Ph.D. (1 December 2006). The Best Schools: How Human Development Research Should Inform Educational Practice. ASCD. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-4166-0457-0. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ a b Iona H. Ginsburg, "Jean Piaget and Rudolf Steiner: Stages of Child Development and Implications for Pedagogy", Teachers College Record Volume 84 Number 2, 1982, pp. 327–337. Cite error: The named reference "IHG" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e Carolyn Pope Edwards, "Three Approaches from Europe", Early Childhood Research and Practice, Spring 2002 Cite error: The named reference "Edwards" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Ginsberg, Iona H. (1982). "Jean Piaget and Rudolf Steiner:stages of child development and implications for pedagogy". Teachers College Record. 84 (2): 327–337.

- ^ Woods, Philip A. (2005). Steiner Schools in England. UK Department for Education and Skills (DfES). p. 89.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Grant, M. (1999). "Steiner and the Humours: The Survival of Ancient Greek Science". British Journal of Educational Studies. 47: 60. doi:10.1111/1467-8527.00103.

In individuals the temperaments are mixed in the most diverse ways, so that it is possible only to say that one temperament or another predominates in certain traits. Temperament inclines toward the individual, thus making people different, and on the other hand joins individuals together in a group so proving that it has something to do both with the innermost essence of the human being and with universal human nature."

- ^ Woods, Philip A. (2005). Steiner Schools in England. UK Department for Education and Skills (DfES). p. 18.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sarah W. Whedon (2007). Hands, Hearts, and Heads: Childhood and Esotericism in American Waldorf Education. ProQuest. ISBN 978-0-549-26917-5. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ Woods, Philip A. (2005). Steiner Schools in England. UK Department for Education and Skills (DfES). p. 89-90.

For example, melancholic children like sitting together because they are unlikely to be annoyed or disturbed by their neighbors. Livelier temperaments such as sanguine or choleric are said to be likely to rub their liveliness off on each other and calm down of their own accord. Little evidence of this aspect of practice was immediately apparent to outside observers, and teachers did not readily volunteer to talk about it.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Stehlik, Tom (2008). Thinking, Feeling, and Willing: How Waldorf Schools Provide a Creative Pedagogy That Nurtures and Develops Imagination. In Leonard, Timothy and Willis, Peter, Pedagogies of the Imagination: Mythopoetic Curriculum in Educational Practice.. Springer. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-4020-8350-1. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ OECD (2005). Formative Assessment Improving Learning in Secondary Classrooms: Improving Assessment in Secondary Classrooms. p. 267.

- ^ a b c d e Todd Oppenheimer, Schooling the Imagination, Atlantic Monthly, September 1999

- ^ a b P. Bruce Uhrmacher, Making Contact: An Exploration of Focused Attention Between Teacher and Students", Curriculum Inquiry, Vol 23, No 4, Winter 1993, pp433–444.

- ^ Ginsburg and Opper, Piaget's Theory of Intellectual Development, ISBN 0-13-675140-7, pp. 39–40

- ^ a b Woods, Philip A. (2006). "In Harmony with the Child: the Steiner teacher as a co-leader in a pedagogical community". FORUM. 48 (3): p.319.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Ida Oberman, "Waldorf History: Case Study of Institutional Memory", Paper presented to Annual Meeting of the American Education Research Association, March 24–28, 1997, published US Department of Education - Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC)

- ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1080/00405849709543751, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1080/00405849709543751instead. - ^ a b c Thomas William Nielsen, "Rudolf Steiner's Pedagogy of Imagination: A Phenomenological Case Study", Peter Lang Publisher 2004

- ^ Franklin, Cheryl A. (2002). James W. Guthrie (ed.). Encyclopedia of Education. New York: Macmillan Reference USA. pp. 1520–1522.

Looping has gained popularity, but it is still considered innovative.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1007/BF02354381, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1007/BF02354381instead. - ^ *"The overarching goal is to help children build a moral impulse within so they can choose in freedom what it means to live morally."—Armon, Joan, "The Waldorf Curriculum as a Framework for Moral Education: One Dimension of a Fourfold System.", (Abstract), Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association (Chicago, IL, March 24–28, 1997), p. 1

- ^ Peter Schneider, Einführung in die Waldorfpädogogik, Klett-Cotta 1987, ISBN 3-608-93006-X

- ^ Ronald V. Iannone, Patricia A. Obenauf, "Toward Spirituality in Curriculum and Teaching", page 737, Education, Vol 119 Issue 4, 1999

- ^ Carnie, Fiona (2003). Alternative approaches to education : a guide for parents and teachers. London: RoutledgeFalmer. p. 47. ISBN 0-415-24817-5.

- ^ Nicholson, David W. (2000). "Layers of experience: Forms of representation in a Waldorf school classroom". Journal of Curriculum Studies. 32: 575–587.

- ^ Thomas Armstrong, cited in Eric Oddleifson, Boston Public Schools As Arts-Integrated Learning Organizations: Developing a High Standard of Culture for All, :"Waldorf education embodies in a truly organic sense all of Howard Gardner's seven intelligences. Rudolph Steiner's vision is a whole one, not simply an amalgam of the seven intelligences. Many schools are currently attempting to construct curricula based on Gardner's model simply through an additive process (what can we add to what we have already got?). Steiner's approach, however, was to begin with a deep inner vision of the child and the child's needs and build a curriculum around that vision."

- ^ Ernest Boyer, cited in Eric Oddleifson, Boston Public Schools As Arts-Integrated Learning Organizations: Developing a High Standard of Culture for All, Address of May 18, 1995: "One of the strengths of the Waldorf curriculum is its emphasis on the arts and the rich use of the spoken word through poetry and storytelling. The way the lessons integrate traditional subject matter is, to my knowledge, unparalleled. Those in the public school reform movement have some important things to learn from what Waldorf educators have been doing for many years. It is an enormously impressive effort toward quality education."

- ^ Easton, Freda (1 March 1997). "Educating the whole child, "head, heart, and hands": Learning from the Waldorf experience". Theory Into Practice. 36 (2): 87–94. doi:10.1080/00405849709543751.

- ^ Spies, Werner E. (1985), "Gleichrichtung und Kontrast - Schulprogramme und Gesellschaftsprogramme", in Edding, Friedrich et al. (eds), Praktisches Lernen in der Hibernia-Pädagogik: eine Rudolf Steiner-Schule entwickelt eine neue Allgemeinbildung. Stuttgart: Klett, pp. 203, ff.

- ^ Nicholson, David W. (1 July 2000). "Layers of experience: Forms of representation in a Waldorf school classroom". Journal of Curriculum Studies. 32 (4): 575–587. doi:10.1080/00220270050033637.

- ^ Christensen, Leah M (2007). "Going Back to Kindergarten: Applying the Principles of Waldorf Education to Create Ethical Attorneys" (PDF). Suffolk University Law Review. 40 (2).

- ^ Gidley, Jennifer (2010). "Comparing beliefs and values related to civic and moral issues among students in Swedish mainstream and Steiner Waldorf schools". Journal of Beliefs & Values: Studies in Religion & Education. 31 (2).

- ^ Gidley, J. (1998). "Prospective Youth Visions through Imaginative Education." Futures 30(5), pp395–408

- ^ a b Tolerance: The Threshold of Peace., UNESCO, 1994.

- ^ Salaam Shalom Educational Foundation

- ^ Salaam Shalom

- ^ When Ahmed met Avshalom, Israel21c, May 28, 2006.

- ^ Women of the Year nominee for 1997 (English translation). Accessed 2008-04-29.

- ^ Tashi Waldorf School. Accessed 2010-03-28.

- ^ Kevin Rohan Memorial Eco Foundation website

- ^ Arline Monks, "Breaking Down the Barriers to Learning: The Power of the Arts", Journal of Court, Community and Alternative Schools

- ^ a b Babineaux, R., Evaluation report: Thomas E. Mathews Community School, Stanford University 1999, cited in Monks, op. cit.

- ^ "Friends of Waldorf Education". UNESCO. Retrieved January, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Carlo Willmann, Waldorfpädogogik, Kölner Veröffentlichungen zur Religionsgeschichte, v. 27. Böhlau Verlag, ISBN 3-412-16700-2. See "Ganzheitliche Erziehung", 2.3.3"

- ^ ASWSNA effective practices

- ^ Tom Stehlik ("Parenting as a Vocation", International Journal of Lifelong Education 22 (4) pp. 367–79, 2003, cited in DFES report

- ^ Holmes, M. (2000). "How Should Educational Policymakers Address Conflicting Interests within a Diverse Society?". Curriculum Inquiry. 30: 129. doi:10.1111/0362-6784.00157.

Genuine communities, such as a community of fundamentalist Christians, Orthodox Jews, or supporters of Steiner's Waldorf ideas [...]

- ^ WASC Accrediting commission for schools

- ^ * Ullrich, Heiner (1991), Waldorfpädagogik und okkulte Weltanschauung (3rd edn). Weinheim, Munchen: Juventa.

- Ullrich, Heiner (1994), "Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925)", Prospects: The Quarterly Review of Comparative Education, 24.3-4

- Ullrich, Heiner (1995), "Vom AuBenseiter zum Anfuhrer der Reformpadagogischen Bewegung", in Vierteljahrsschrifi fur wissenschaftliche Pädagogik (Bochum), 71, 284, ff.

- Grasshoff, Gunther, Davina Hoeblich, Bernhard Stelmaszyk and Heiner Ullrich (2006), "Klassenlehrer-Schüler-Beziehungen als biografische Passungsverhaltnisse", in Zeitschrift für Pädagogik (Weinheim)

- Bo Dahlin, Ingrid Liljeroth, Agnes Nobel (2006), "Waldorfskolan –en skola för människobildning?", Karlstad

- Helsper, Ullrich, Stelmaszyk, Hoblich, Grasshoff, Jung (2007), "Autorität und Schule. Eine empirische Rekonstruktion der Klassenlehrer-Schüler-Beziehung an Waldorfschulen". Wiesbaden: VS-Verlag

- ^ a b c Fanny Jiminez, "Namen tanzen, fit in Mathe - Waldorf im Vorteil". Die Welt Sept 26, 2012, citing Barz, et. al, Bildungserfahrungen an Waldorfschulen: Empirische Studie zu Schulqualität und Lernerfahrungen, 2012

- ^ Earl J. Ogletree, The Comparative Status of the Creative Thinking Ability of Waldorf Education Students, also reported in Woods, p. 152

- ^ Cox, Maureen V.; Rowlands, Anna (2000). "The effect of three different educational approaches on children's drawing ability: Steiner, Montessori and traditional". British Journal of Educational Psychology. 70 (4): 485. doi:10.1348/000709900158263.

- ^ Gidley, Jennifer M.; Hampson, Gary P. (2005). "The evolution of futures in school education". Futures. 37 (4): 255. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2004.07.005.

- ^ a b c d e Fanny Jiménez, "Wissenschaftler loben Waldorfschulen", Die Welt, 27 September 2012

- ^ Edgar Allen Beem, The Waldorf Way, Boston Globe, April 16, 2001

- ^ Robert S. Peterkin, Director of Urban Superintendents Program, Harvard Graduate School of Education and former Superintendent of Milwaukee Public Schools, in Boston Public Schools As Arts-Integrated Learning Organizations: Developing a High Standard of Culture for All:"Waldorf is healing education. ... It is with a sense of adventure that the staff of Milwaukee Public Schools embraces the Waldorf concept in an urban multicultural setting. It is clear that Waldorf principles are in concert with our goals for educating all children."

- ^ Eisner, Elliot W. (1994). Cognition and curriculum reconsidered (2nd ed. ed.). New York: Teachers College Press. p. 83. ISBN 0807733105.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Röhrs, Hermann (1998). Reformpädagogik und innere Billdungsreform. Weinheim: Beltz. pp. 90–91. ISBN 3ß89271ß825ß3.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Pamela Bolotin Joseph; et al. (6 December 2012). Cultures of Curriculum. Routledge. pp. 118-. ISBN 978-1-136-79219-9. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2010/09-0038), please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1044/1058-0360(2010/09-0038)instead. - ^ a b c Elkind, David (2001). "Much Too Early". Education Next.

- ^ a b Sebastian Suggate, "Watering the garden before a rainstorm: the case of early reading instruction" in Contemporary Debates in Childhood Education and Development, ed. Sebastian Suggate, Elaine Reese. pp. 181-190.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.04.004, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.04.004instead. - ^ Catherine Gaunt, Steiner-Waldorf schools win victory on EYFS exemptions Nursery World, 28 January 2013

- ^ a b c John Siraj-Blatchford; David Whitebread (1 October 2003). Supporting ICT in the Early Years. McGraw-Hill International. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-335-20942-2. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ^ "Reading is a habit that we can't afford to lose", The Herald, December 2, 2007

- ^ Østergaard, Edvin (1 September 2008). "Doing phenomenology in science education: a research review". Studies in Science Education. 44 (2): 93–121. doi:10.1080/03057260802264081.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ See report of the study in Østergaard, Edvin; Dahlin, Bo; Hugo, Aksel (2008). "Doing phenomenology in science education: A research review". Studies in Science Education. 44 (2): 111–112. doi:10.1080/03057260802264081.

- ^ Simpson, Peter Vinthagen (29 August 2008). "Stockholm University ends Steiner teacher training". The Local. Retrieved December, 2012.

Stockholm University has decided to wind up its Steiner-Waldorf teacher training. Steiner science literature is 'too much myth and too little fact', the university's teacher education committee has ruled.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Simpson, Peter Vinthagen (29 August 2008). "Stockholm University ends Steiner teacher training". The Local. Retrieved December, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Simpson, Peter Vinthagen (29 August 2008). "Stockholm University ends Steiner teacher training". The Local. Retrieved December, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ a b Barker, Irena (17 September 2012). "Homeopathy? Sorry, we're just not swallowing it". TES. Retrieved December, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Woods, Philip A; Woods, Glenys J (2002). "Policy on School Diversity: Taking an Existential Turn in the Pursuit of Valued Learning?". British Journal of Educational Studies. 50 (2): 254–278. doi:10.1111/1467-8527.00201. JSTOR 3122313.

- ^ a b Association of Waldorf Schools of North America, "Position Statement adopted by the Board of Trustees", June 25, 1997

- ^ Daar, Judy; Dugan, Dan (1994). "Are Rudolf Steiner's Waldorf schools 'non-sectarian?'". Free Inquiry. 14 (2): 44. ISSN 0272-0701.

- ^ See Steiner, Rudolf (1920). Conferences with Teachers of the Waldorf School in Stuttgart, 1919 to 1920 Volume One. Forest Row, East Sussex: Steiner Schools Fellowship Publications, 1986, p. 125. (The original transcription of the conference text reads "Man muß sich bewußt sein, nicht von innen her, von außen her, daß man nötig hat, um wenigstens das zu machen, was wir durchbringen wollen, mit den Leuten zu reden, und ihnen innerlich eine Nase zu drehen.").

- ^ Damrell, Frank C., Minute Order, November 27, 2007. Text of order. Accessed 2007-12-17.

- ^ Memorandum and Order November 2010

- ^ Cannon, Michelle L. (June 11, 2012). "Ninth Circuit Affirms Trial Court Decision In Waldorf Methods Case". martindale.com. Retrieved December, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Education and Social Cohesion--Religion in the Classroom", Institute for Cultural Diplomacy

- ^ Mark Riccio, Rudolf Steiner's Impulse in Education, dissertation, Columbia University Teachers College, 2000, p. 87

- ^ "Frome Steiner school causes controversy". BBC News. 19 November 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ^ European Council for Steiner Waldorf Education (October 2007). "Waldorf schools against discrimination" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-11-29.

- ^ Rout, Milanda (July 28, 2007). "Questions about Steiner's classroom". The Australian. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ^ "HPA National Measles Guidelines — Local & Regional Services". Health Protection Agency. October, 2010. p. 5. Retrieved December, 2012.

membership or contact with an unvaccinated community (including Steiner schools, travelling families etc) increases the index of suspicion.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Thomas, John (2012). "Autism, medicine, and the poison of enthusiasm and superstition". Journal of Health & Biomedical Law. 7 (3). ISSN 1556-052X.

- ^ Consensus statement, agreed by members of the ECSWE, meeting in Copenhagen, 21 January 2001.

- ^ European Council for Steiner Waldorf Education

Further reading

- Clouder, Christopher (ed.). Education: An Introductory Reader. Sophia Books, 2004 (a collection of relevant works by Steiner on education).

- Lyons, Suzanne. Toward a holistic approach to earth science education unpublished Master's thesis, University of California Sacramento, 2010.

- Steiner, Rudolf. "The Education of the Child, and early Lectures on Education" in Foundations of Waldorf Education, Anthroposophic Press, 1996 (includes Steiner's first descriptions of child development, originally published as a small booklet).

- Steiner, Rudolf. The Foundations of Human Experience (also known as The Study of Man). Anthroposophic Press, 1996 (these fundamental lectures on education were given to the teachers just before the opening of the first Waldorf school in Stuttgart in 1919).

- Note: all of Steiner's lectures on Waldorf education are available in PDF form at this research site

External links

- General reference

- Studies

- Larrison, Abigail L., Alan J. Daly, and Carol VanVooren. 2012. "Twenty Years and Counting: A Look at Waldorf in the Public Sector Using Online Sources" Current Issues in Education 15:3.

- 2008 overview of all Australian academic studies of Steiner education and Steiner philosophy by Jennifer Gidley: Turning Tides: Creating Dialogue between Rudolf Steiner and 21st Century Academic Discourses

- "Learning From Rudolf Steiner: The Relevance of Waldorf Education for Urban Public School Reform" by Ida Oberman (PDF)

- Association of Waldorf Schools of North America Study of Waldorf graduates in the USA, Part I, Part II

- Articles

- What's Waldorf Salon.com Meagan Francis

- "Steiner schools' could help all" by Branwen Jeffreys. BBC News Report on British government-funded study on Waldorf education in the UK, July 5, 2005.

- "Waldorf Succeeds in Public Schools" by Claudia M. Lenart. Conscious Choice, August 2000.

- "Who was Rudolf Steiner and what were his revolutionary teaching ideas?" Richard Garner, Education Editor, The Independent

- "Schooled in spirituality" by Chrisanne Beckner. Sacramento News and Review, February 3, 2005.

- "Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925)" by Robert Todd Carroll, editor of The Skeptics Dictionary.

- Elizabeth Daniels and Carmen Gamper. "The Yin and Yang of Waldorf and Montessori in Early Childhood Education" (comparison of the two systems). Common Ground part 1, part 2

- Cincinnati Enquirer Waldorf goes against school grain by Maggie Dons