Search-for terms

- avoid repetitions

Supporting refs

Notes-to-be-prosified

- mil.hist.

- Sea Peoples (rovers) survived in part after loss at the Delta as Tjeker and Peleset (Palestinians?)[1]

The earliest use for galleys in warfare was to ferry fighters from one place to another, and until the middle of the 2nd millenium BC had no real distinction from merchant freighters. Around the 14th century, the first dedicated ships used for belligerent purposes were developed, sleeker and with cleaner lines than the bulkier merchants. They were used for raiding, capturing merchants and for dispatches.[2]

From this early period, raiding became the most important form of organized violence in the Mediterranean region. Maritime classicist historian Lionel Casson has used the example of Homer's works to show that seaborne raiding was considered a common and legitimate occupation among ancient maritime peoples. The later Athenian historian Thucydides described it as having been "without stigma" before his time.[3]

The attack on the city of Troy, THE MAIN EVENT of the Iliad was made by what Casson and other authors have described as "sea rovers".[4]

Sailing in open water with no sight of land was exceptional in antiquity, with ships skirting the coast as much as possible. At night, galleys were pulled up on land and the crew normally ate and slept ashore before setting out again to sea the next day.[5]

Sailing was largely restricted in the winter season; most maritime activity was conducted in the period between April and October throughout all of antiquity. Rough weather and storms were potent risks in winter, but the biggest obstacle was poor visibility and cloudy skies. Visibility in the Mediterranean was otherwise very good and the open water distances were few and small enough not to be a major limitation. The navigational tools of the ancient mariner was based on following known stars and constellations and following known landmarks. Pilots familiar with their local coastal areas were also used, as were lead lines that could make soundings and pick up bottom samples. It's possible that primitive sea charts existed, though none have survived.[6]

The open sea was also avoided because it was for the most part a no-man's-land where one risked attack and plunder. The only way to control the ancient sea lanes was to have overwhelming superiority in forces or to control most of the coastal areas, something which required massive resources that only a few large empires were capable of.[7]

Friezes found on the island of Thera shows early-type galleys in procession that have been described as part of a "navy" of the Minoans, "the first great sea power of the Mediterranean", according to Casson.[8]

- Greeks colonized Mediterranean and Black Sea 750-550 BC[9]

- Phocaeans (Greeks) managed to get west of Gibraltar, but had to fight the Phoenicians for more permanent trading rights; won a Pyrrhic victory; three battles in total fought against Greeks, all Phoenician losses, but Gibraltar remained closed and Phoenician monopoly[10]

- slave rowers too expensive; had to be maintained "permanently"; only used in emergencies (Athens) and then often were rewarded with their freedom: considerable economic investment[11]

- triaconters were outdated, but kept for scouting and dispatches; penteconters completely displaced by more efficient and maneuverable triremes[12]

- three successor-states formed power centers after brief existence of Alexander the Great's empire fell apart: Macedonia, Ptolemaic Kingdom and Seleucid Empire formed the new major naval powers of the Mediterranean; Seleucids and and Ptolemais "touched off the greatest naval naval race in ancient history"[13]

- successive increase in galley size from sixes to sixteens and up to thirties, all actually used in battle (though the larger ones were rarer)[14]

- Macedon and Ptolemys fought each other to a standstill in the 3rd century BC with "super galleys"; when Romans conquered Macedon in 168 BC and found a sixteen it was a "fossil" that hadn't been to sea for over 70 years[15]

- Romans copied Carthage in their wars with them; managed to take advantage of superiority in quality of soldiers by inventing the corvus (a spiked gang-plank); first used at Mylae 260 BC[16]

- Romans gained experience in Punic Wars, stole/copied more fast designs and built a superior fleet: won in 241; forced Carthage to wage a land war against them in the Second Punic War; by 201 BC, Rome was the greatest sea power in the (Western?) Mediterranean[17]

- Rome turned east and conquered it by 160s BC; avoided the sea to a great extent and let as much as possible of fleets be handled by allies[18]

- Augustus established Roman navy that dominated Mediterranean (based on Pompey's pirate-hunting operation)[19]

- Misenum and Ravenna (on either side of Italy) became the bases for the two major core fleets/squadrons; contributed manpower to organize naumachias and to handle awnings at arenas and amphitheatres[20]

- possible Roman naval patrols in Red Sea[21]

- trade

- Phoenician were the first to trade west of Corsica-Sardinia-Sicily (from c. 700 BC): mostly silver and especially tin from Spain and as far north as England (through middlemen)[22]

- merchant galleys were used for "shorter hauls and general coastal work"[23]

- beamier merchant galleys, probably based on earlier military horse transports[24]

- design

- Egyptian river craft built for Nile, simply upsized when they turned ocean-going; had no keels, but centerline hawsers on crutches that could be tightened by twisting (tourniquet), side rudders, early versions with "double-stepped" masts[25]

- mortise-and-tenon technique "more cabinet work than carpentry" *[26], dated to 1300 BC at the latest[27]

- Mycenaean galleys had 20-100 oars (usually 30-50): shallow draft, low railings, boom-less sail (bunched up against yard with brails (like venetian blinds)) [28]

- description of Homer's ships (1300-1200 BC): long, low hull; prow that rose straight up ("horns" as decoration in front, often backwards-curved; curved stern; ram entry depicted on pottery[29]

- ram on an Athenian safety pin from 850 BC???[30]

- from "open, undecked affairs" to a "half deck" covering bow, stern and with a centerline gangway; rowers sat on the same level as the railing, but could move down on a lower level when fighting commenced, getting increased protection; prow lost "swept back curve" (?); stern got its distinct fan-like decoration (often treated as "scalp" when cut off enemy ships after a victory) -> penteconters became the new "ship of the line"[31]

- the trireme was made possible by adding an outrigger for the third, top-most, bank; hull shape retained, though; established by late 6th century BC; layout dominated ancient warfare until late 4th century BC[32]

- extant dock slips show that triremes were 121 ft long, 20 ft wide[33]

- pointed rams (used early) could make a neat hole that it then stuck in; the later square, 3-fanned rams were designed to punch open seams[34]

- bireme invented before 700 (to shorten ships with an equal amount of oars), either by Greeks or Phoenicians; two rows were staggered to economize space[35]

- two square sails standard by 700; masts were lowered before battle, or left ashore; a hemiolia, "one and a half-er?", was invented where some of the rowers could get out of their seats to stow the mast[36]

- triremes aged quickly; 20 years at most, 25 in exceptional cases; Greeks had 4-grade quality classification of their galleys[37]

- Syracuse learned to reinforce their bow timbers and cornered the superior Athenian navy bow-to-bow[38]

- Athlit ram was most likely from a five, possibly a four (76 x 95 x 226 cm; 465 kg); very expensive and complicated to cast even with later standards; the biggest single expense in constructing a galley; a war-trophy memorial shows evidence of a socket of one that was three times as wide (a "gargantuan casting"), likely from a ten captured at Actium; proves that ramming remained important, even if there was a shift towards infantry and other weapons[39]

- gradual abandonment of mortise and tenon-technique until the first appearance of an "all-skeleton" construction in 1025[40]

- Augustus' admiral Agrippa invented "grapnel catapult"[41]

- Romans eliminated the oarbox by broadening the hull; and introduced an "arched doghouse" in the stern as quarters for the commander[42]

- piracy

- Rhodian triemiolia developed as a pirate-hunter; a trireme were part of the uppermost row of oarsmen could move out to make room for the mast[43]

- Cilician pirates had their heydays in the 1st century BC with liburnians, hemiolias and even some triremes; eradicated by Pompey in 67 BC in an operation that created the squadrons that would later become the core of the new Roman regional fleets[44]

- tactics

A successful ramming was difficult to achieve; just the right amount of speed was and precise maneuvering was required. Fleets that did not have well-drilled, experienced oarsmen and skilled commanders relied more on boarding with superior infantry (like increasing the compliment to 40). Ramming attempt were countered by keeping the bow towards the enemy until the enemy crew tired, and then attempt to board as quickly as possible.[45]

A double line formation could be used to achieve a breakthrough by engaging the first line and then rushing the rearguard in to take advantage of weak spots in the enemy's defense. This required superiority in numbers, though, since a shorter front risked being flanked or surrounded.[46]

- Rhodes invented fire pots that were suspended from two rods projecting over the bows: could be dumped over enemy ships, or frighten them into exposing their sides for ramming[47]

- Roger of Lauria lured out Angevin fleet at Malta; attacking galleys beached stern-first very dangerous (allowed good cohesion and an opportunity for crews and soldiers to escape)[48]

- Roger of Lauria had success with skilled crossbowmen and light infantry who had better footing than heavily-armed French infantry/knights[49]

- Roger of Lauria used cooking pots filled with soap at Naples in 1284 to make enemy decks slippery for heavy infantry[50]

- medieval naval battles at night were very rare[51]

- prestige/etc

- Ptolemy IV built a floating villa for travel in style along the Nile[52]

Lead

A galley is a type of ship that is propelled mainly by rowing. It originated in the Mediterranean around the 8th century BC and remained in use in various forms until the early 19th century in warfare, trade and piracy. The galley is characterized by its long, slender hull, shallow draft and low clearance between sea and railing. Virtually all types of galleys have had sails that could be used in favorable winds, but human strength remained their primary method of propulsion. This allowed them the freedom to move independent of winds and currents, and with great precision.

Galleys were the warships used by the first major Mediterranean powers, including the Greeks, Phoenicians and Romans. They remained the dominant types of vessels used for war and piracy in the Mediterranean Sea until the last decades of 16th century.

Galleys were the first ships to effectively use heavy cannons as anti-ship weapons. In 16th century, they were highly efficient gun platforms that forced changes in the design of medieval seaside fortresses and sailing warships.

They experienced their zenith in the late 15th century, but were by the 17th century swiftly displaced by sailing ships and hybrid types like the xebec. They were used for certain specific purposes in the Atlantic Ocean during the Middle Ages, and saw limited use in the Caribbean, the Philippines and the Indian Ocean in the early modern period, mostly as patrol craft. From the mid 16th they were in intermittent use in the Baltic Sea, where the geography benefited their usage, and experienced an isolated revival there in the 18th century with the expansion of Russia against the older Baltic powers of Sweden and Denmark.

In warfare it carried various types of weapons throughout its long existence, including rams, catapults and cannons, but relied primarily on its large crew to overpower enemy vessels in boarding actions and close combat.

- amphibious nature; auxiliary of armies

- dominant use by early states until 16th

- shift of power to north, Atlantic and colonies

Definition and terminology

Origins

- look up navigation, beaching by night, etc. in Pryor (?)

Military history

- 1100-700 BC?

The rise of classical civilizations

Roman Empire

C. 350-800

- Byznatine navy

- Carolingians

- Italians

- see Hocker in Morrison & Gardiner (1995)

Byzantine era

- all naval warfare before 15?? was essentially amphibious?

In the eastern Mediterranean, the Byzantine Empire struggled primarily with the incursion from invading Muslim Arabs from the 7th century, leading to fierce competition, a buildup of naval forces, and that war galleys once more grew in size. Soon after conquering Egypt and the Levant, the Arabs built ships with the help of local Coptic shipwrights at former Byzantine naval bases, which were highly similar to Byzantine dromons.[53] By the 9th century, the struggle between the Byzantines a Arabs had turned the Eastern Mediterranean into a no man's land for most merchants. In the 820s Crete was captured by Andalusian Muslims displaced by a failed revolt against the Emirate of Cordoba, turning the island into a base for (galley) attacks on Christian shipping until the island was recaptured by the Byzantines in 960.[54]

The collapse and division of the Carolingian Empire in the late 9th century brought on a period of instability, meaning increased piracy and raiding in the Mediterranean, particularly by newly-arrived Muslim invaders. The situation was worsened by raiding Scandinavian Vikings who used longships, vessels that in many ways were similar to galleys and used similar tactics. To counter the threat, local rulers began to build large oared vessels, some with up to 30 pairs of oars, that were larger, faster and with higher sides than Viking ships.[55] Scandinavian expansion, including incursions into the Mediterranean and attacks on both Muslim Iberia and even Constantinople itself, subsided by the mid-11th century. By this time, greater stability in merchant traffic was achieved by the emergence of Christian kingdoms such as those of France, Hungary and Poland. Around the same time, Italian port towns and city states, like Venice, Pisa and Amalfi, rose on the fringes of the Byzantine Empire as it struggled with eastern threats.[56]

As early as 1304 the type of ship required by the Danish defense organization changed from galleys??? to cogs, a flat-bottomed sailing ship.[57]

The modern "galley"

During the 13th and 14th century, the galley evolved into a design that was to remain essentially the same until it was phased out in the late 18th century. It was descended from the types used by the Byzantine and Muslim fleets and were the mainstay of all Mediterranean powers, including the great maritime republics of Genoa and Venice, the Papacy, the Hospitallers, Aragon and Castile, as well as by various pirates and corsairs. The overall term used for these vessels was gallea sottile (Italian for "slender galley"), which established the modern term for the galley. The later Ottoman navy used similar vessels, though generally smaller, faster under sail, but slower under oars.[58]

With the steady decline of the Byzantine Empire in the eastern Mediterranean, the commercially-oriented Italian city-states rose as the new major Christian naval power in the Mediterranean.

- Genoa used a "Commune" early on (1263) to assemble warfleets (of galleys); depended on "private" individuals to take their share[59]

- permanent Genoese state war fleet was not established until 1559 and then fairly tiny (3-6 from 1559-86),[60] though a powerful merchant marine it had a "laughably small navy"[61] TRADE?

- Genoese fleet organization was more flexible and open to change; innovated heavier "trireme" in 1290s; added more marines and guns to become the "most effective warship of its day"[62]

- sailing season extended to winter as well (by Genoa?)[63] CROSS REF WITH PRYOR

- War of Chioggia (1380?) saw the first time use of large scale use of gunpowder weapons/guns on ships (presumably galleys? - cross-ref with Guilmartin, Rodger, others)[64]

- medieval France had "impressive galley dockyards" (unlike England)[65]

- English and French used galleys manned by Italian (experts?)[66]

During the 14th century, galleys began to be equipped with cannons of various sizes, mostly smaller ones at first, but also larger bombardas on vessels belonging to Alfonso V of Aragon.[67] The War of Chioggia (1378-80) between Venice and Genoa was the first conflict with large scale use of gunpowder weapons on ships.[68]

During the early 15th century, the transition in northern waters to sailing ships in naval warfare began in earnest. A Castilian naval raid on Jersey in 1405 became the first recorded battle battle where even a Mediterranean power employed a force consisting mostly of cogs or nefs, rather than oared-powered galleys. Though the transition was obvious in the north, galleys remained the primary warship in the south. The battle of Gibraltar in 1476 has been identified as another important event in northern naval warfare. The battle was dominated by full-rigged ships armed with wrought-iron guns on the upper decks and in the waists, foretelling of the future dominance of sailing warships in the Atlantic and the North Sea.'[69]

Early nation-states/Christian-Ottoman clash/Zenith of the galley fleets

Naval warfare in the Mediterranean was in the 16th century still closely tied to land warfare and worked in a symbiosis with seaside fortresses and strategically vital ports.[70]

- galley campaigning largely limited to summer season; winter campaigns occurred, but were calculated (or desperate) risks; only the Christian corsairs and the North African ghazis were "immune" to these limitations[71]

- early heavy ship guns were effective against early forts and sailing ships with high profiles; galleys vulnerable to hits, but had small target area; maneuverability regardless of wind direction made them capable of disciplined formations (unlike sailing ships)[72]

- lack of development of effective tactics for sailing ships before 1650[73]

- 4 Genoese carracks vs "body" of Ottoman galleys off Constantinople on 20 April 1453: comparable to siege warfare at sea; attempts to board carracks under cover of bow arrows was held off by the Genoese with crossbows, hand cannon pellets and hurling large objects (to stave in galley bottoms; guns did not actually effect on outcome[74]

- battle of Zonchio 1499: one large "command" carrack (?), galleys; two large Venetian carracks and galleys; all three large ships destroyed by Ottoman incendiaries; Ottoman huge gun on large ship sunk Venetian galley (and small "barge") outright early in battle; huge 200-lbs (ammunition weight) cannons used on both sides; gunpowder weapons employed, but not decisive on final outcome[75]

- WHAT ABOUT RED SEA (GUILMARTIN)?

Baltic revival

The Swedish navy still retained 27 galleys in 1809, and the last Swedish-built galley remained on the ship rolls until 1835, before it was retired, 86 years after it was built.

Trade

- two types of Roman ships: galleys and merchants (Unger 1980: 34)

- large differences between South and North: differing hull designs, steering systems, propulsion; both had trade dominated by luxuries, but in the North it was mostly manufactured goods while South concentrated on silks and spices from Asia (South had much higher total value per unit of volume) (Unger 1980: 95-96)

In the earliest times of Mediterranean sea trade, there was no clear distinction between galleys of trade and war other than in their actual usage. Fitting rams to galleys around the 8th century BC brought about a split in the design of ships, and set merchant galleys apart from specialized war galleys. The Phoenicians used galley freighters that were elongated, carried fewer oars and relied more on sails to propel them. Carthaginian galley wrecks found off Sicily that date to the 3rd or 2nd century BC indicate a length to breadth ratio of 6:1, proportions that fell between the 4:1 of sailing merchant ships and 8-10:1 of war galleys. Many merchant galleys in the ancient Mediterranean were used as carriers of valuable cargoes that needed safe transport and perishable goods that needed to be delivered quickly.[76]

Most of the surviving documentary evidence comes from Greek and Roman shipping, though it is believed that merchant galleys all over the Mediterranean were very similar. In Greek they were referred to as histiokopos ("sail-oar-er") to reflect that they relied on both types of propulsion; in Latin they were called actuaria (navis) ("(ship) that moves") , stressing that they were capable of making progress independent of weather conditions. As an example of its speed and reliability, Cato the Elder showed his audience a fig claimed to have been picked in North Africa only three days past during his "Carthago delenda est"-speech, an effective demonstration of the close proximity of the Roman's arch enemy Carthage. Other typical galley cargoes were honey, cheese, meat and live animals intended for gladiator combat. The Romans had several types of merchant galleys that specialized in various tasks. The actuaria, with up to 50 rowers, was considered the most versatile, while the phaselus (lit. "bean pod") was the typical passenger transport, and the lembus served as a small express carrier. Many of these designs continued to be used until the Middle Ages.[77]

After the disintegration of the Western Roman Empire in the early centuries AD, the Mediterranean sea trade contracted. The Eastern Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire, did not revive the overland trade routes but was dependent on keeping the sea lanes open to keep its domains together. Bulk trade fell rapidly around 600-750 while luxury trade increased. Galleys remained profitable in the luxury trade, which could set off their high maintenance cost.[78] In the 10th century, there was a sharp increase in piracy which resulted in larger ships with larger crews. These were built and organized by the city-states of northern Italy, emerging as the dominant sea powers at the time, and included Venice, Genoa and Pisa. They inhereted Byzantine designs, and the new merchant galleys were very similar to dromons without artillery, but were both faster and wider. They could be manned by crews of up to 1,000 men and were could be employed in both trade and warfare. The increase of Western European pilgrimages to the Holy Land further boosted the success of the large merchant galleys.[79]

- the Western Mediterranean was less organized than the Eastern; more pirate activity, more trade in luxuries and less coastal trade; spices, silks, etc imported, slaves and "sylvan" products (and timber) exported (Unger 1980: 51)

- sailing "round" ships transported bulk goods; galleys carried spices, silks, precious cloths, metals, weapons[80]

In northern Europe, Viking longships and their derivations, knarrs, dominated trading and shipping. Though functionally and superficially similar to galleys, they had been developed separately from the Mediterranean shipbuilding tradition. In southern Europe galleys continued to be useful for trade even as sailing vessels evolved more efficient hulls and rigging. They could hug the shoreline and make steady progress when winds failed, which made them highly reliable. The zenith in the design of merchant galleys came with the great state-owned great galleys of the Venetian Republic, first built in the 1290s. These were used to carry the lucrative eastern luxury trade, with spices, silks and gems dominating. They were in all respects larger than contemporary war galleys (up to 46 m) and had a deeper draft, with more room for cargo (140-250 t). Their full complement of rowers ranged from 150 to 180 men, all of whom could defend the ship from attack if the need arose; all in all a very safe mode of travel for its time. For passenger transport, they could take pilgrims heading for Palestine from Venice to Jaffa in 29 days, even including numerous landfalls and in adverse rough weather.[81]

- from the 15th century there were state owned merchant galleys, leased to the highest bidders in charter auctions; standardization of hulls (leased "bare" and empty) from 1420; 150 rowers and 20 officers and "specialists"[82]

- Venetian state merchant galleys system eventually broke down in the 16th (?) century when faced with more enemies, especially aggressive Muslim expansion in Mediterranean[83]

From the first half of the 14th century the Venetian galere da mercato ("merchantman galleys") were being built in the shipyards of the state-run Arsenal as "a combination of state enterprise and private association, the latter being a kind of consortium of export merchants", as Fernand Braudel described them.[84] The ships sailed in convoy, defended by archers and slingsmen (ballestieri) aboard, and later carrying cannons. In Genoa, the other major maritime power of the time, galleys and ships in general were more produced by smaller private ventures.

They were so safe that merchandise was often not insured (Mallet). These ships increased in size during this period, and were the template from which the galleass developed.

Design

- feature of Byzantine warships essentially established by 600: larger than Roman, slower, less cargo space, larger crews, more firepower (Unger 1980: 43) 6:1 ratio, two-banked (2x25 oars per side), 40-50 x 5 m; minimum of one man per oar; 1.5 meter draught; flat bottom amidships; shields on the sides (like Vikings); no stringers, strengthened by strakes and wales; MORE TO BE GOT IF NEEDED AND SOURCE IS RELIABLE (Unger 1980: 43-45)

- hulls need to have high (M)(length at waterline: 1/3 of displaced volume): a trireme has about 9 (and no ballast), medieval and medieval and "later war galleys" 6.5-8 (Coates 1995: 128)

- sharp bottoms without keelsons to support the structure; transverse framing secured with dowels with nails driven through (Coates 1995: 131); hypozomata used since Hatshepsut and in ancient galleys, but of unknown design and method of tightening (Coates 1995: 132); hulls were watertight without any caulking (Coates 1995: 132)

- ram-supporting structures were built on to the hull to take the impact of vertical or lateral motion and thereby protect the hull from penetration, weight of rams only about 0,4-2 t (Coates 1995: 133-4)

- less expensive building technology; more fragile, but faster; after 600 came a "major step" towards skeleton construction, though not completely[85]

- hull protection (lead sheathing) abandoned, though uses for warships in the 10th century[86]

Galleys have since their first appearance in ancient times been intended as highly maneuverable vessels, independent of winds by being rowed, and usually with a focus on speed under oars. The profile has therefore been that of a markedly elongated hull with a ratio of breadth to length at the waterline of at least 1:5, and in the case of ancient Mediterranean galleys as much as 1:10 with a small draught, the measurement of how much of a ship's structure that is submerged under water. To make it possible to efficiently row the vessels, the freeboard, the height of the railing to the surface of the water, was by necessity kept low. This gave oarsmen enough leverage to row efficiently, but at the expense of seaworthiness. These design characteristics made the galley fast and maneuverable, but more vulnerable to rough weather.

On the funerary monument of the Egyptian king Sahure (2487–2475 BC) in Abusir, there are relief images of vessels with a marked sheer (the curvature along its length) and seven pairs of oars along its side, a number that was likely to have been merely symbolical, and steering oars in the stern. They have one mast, all lowered and vertical posts at stem and stern, with the front decorated with an Eye of Horus, the first example of such a decoration. It was later used by other Mediterranean cultures to decorate sea going craft in the belief that it helped to guide the ship safely to its destination. These early galleys apparently lacked a keel meaning they lacked stiffness along their length. Therefore they had large cables connecting stem and stern resting on massive crutches on deck. They were held in tension to avoid hogging, or bending the ship's construction upwards in the middle, while at sea.[87] In the 15th century BC, Egyptian galleys were still depicted with the distinctive extreme sheer, but had by then developed the distinctive forward-curving stern decorations with ornaments in the shape of lotus flowers.[88] They had possibly developed a primitive type of keel, but still retained the large cables intended to prevent hogging.[89]

The design of the earliest oared vessels is mostly unknown and highly conjectural. They likely used a mortise construction, but were sewn together rather than pinned together with nails and dowels. Being completely open, they were rowed (or even paddled) from the open deck, and likely had "ram entries", projections from the bow lowered the resistance of moving through water, making them slightly more hydrodynamic. The first true galleys, the triaconters ("thirty-oarers") and penteconters ("fifty-oarers") were developed from these early designs and set the standard for the larger designs that would come later. They were rowed on only one level, which made them fairly slow, likely only 5-5.5 knots. By the 8th century BC the first galleys rowed at two levels had been developed, among the earliest being the two-level penteconters which were considerably shorter than the one-level equivalents, and therefore more maneuverable. They were an estimated 25 m in length and displaced 15 tonnes with 25 pairs of oars. These could have reached an estimated top speed of up to 7.5 knots, making them the first genuine warships when fitted with bow rams. They were equipped with a single square sail on mast set roughly roughly halfway along the length of the hull.[90]

Antiquity

The documentary evidence for the construction of ancient galleys is fragmentary, particularly in pre-Roman times. Plans and schematics in the modern sense did not exist until the 17th century and nothing like them has survived from ancient times. How galleys were constructed has therefore been a matter of looking at circumstantial evidence in literature, art, coinage and monuments that include ships, some of them actually in natural size. Since the war galleys floated even with a ruptured hull and virtually never had any ballast or heavy cargo that could sink them, not a single wreckage of one has so far been found. The only exception has been a partial wreckage of a small auxiliary galley from the Roman era.[91]

By the 5th century BC, the first triremes were in use by various powers in the eastern Mediterranean. It had now become a fully developed, highly specialized vessel of war that was capable of high speeds and complex maneuvers. At nearly 40 m in length, displacing almost 50 tonnes, it was more than three times as expensive than a two-level penteconter. A trireme also had an additional mast with a smaller square sail placed near the bow.[92] Up to 170 oarsmen sat on three levels with one oar each that varied slightly in length. Two accommodate three levels of oars, rowers sat staggered on three levels. Arrangement of the three levels are believed to have varied, but the most well-documented design made use of a projecting structure, or outrigger, where the oarlock in the form of a thole pin was placed. This allowed the outermost row or oarsmen enough leverage to complete their strokes without lowering the efficiency.[93]

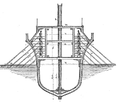

The first dedicated war galleys fitted with rams were built with a mortise and tenon technique (see illustration), a so-called shell-first method. In this, the planking of the hull was strong enough to hold the ship together structurally, and was also watertight.[95] The ram, the primary weapon of Ancient galleys from around the 8th to the 4th century BC, was fitted onto a structure that was attached to hull rather than directly on the hull. This way galleys would not be holed if the ram was twisted off in action. It consisted of a massive projecting timber with a thick bronze casting with horizontal blades that could weigh from 400 kg up to 2 tonnes.[92]

Besides Athlit bronze rams, [96] the only other parts of ancient galleys to survive are parts of two Punic biremes off western Sicily (see Basch & Frost). These Punic galleys are estimated to have been 35 m long, 4.80 m wide, with a displacement of 120 tonnes. These biremes had evidence of an easily breakable pointed ram, more like the Assyrian image than the Athlit ram. This type of ram may have been designed to break off to prevent that the hull was breached.

Galleys were hauled out of the water whenever possible to keep them dry, light and fast and free from worm, rot and seaweed. Galleys were usually kept in ship sheds during the winter. The archaeological remains of these have left scholars with valuable clues to the dimensions of the ships themselves.[97]

Building an efficient galley posed technical problems. The faster a ship travels, the more energy it uses. Through a process of trial and error, the unireme or monoreme — a galley with one row of oars on each side — reached the peak of its development in the penteconter, about 38 m long, with 25 oarsmen on each side. It could reach 9 knots (18 km/h), only a knot or so slower than modern rowed racing-boats.

Roman era

Galleys from 4th century BC up to the time of the early Roman Empire in the 1st century AD became successively larger and heavier. Three levels of oars had proved to be the practical limit, but it was improved on by making ships longer, broader and heavier and placing more than one rower per oar. Naval conflict grew more intense and extensive, and by 100 BC galleys with four, five or six rows of oarsmen were commonplace and carried large complements of soldiers and catapults. With high freeboards (up to 3 m) and additional tower structures from which missiles could be shot down onto enemy decks, they were intended to be like floating fortresses.[98] Designs with everything from eight rows of oarsmen and upwards were built, but most of them are believed to have been impractical show pieces never used in actual warfare.[99] Ptolemy IV, the Greek pharaoh of Egypt 221-205 BC is recorded as building a gigantic ship with forty rows of oarsmen, but without specification of its design. A suggested construction was that of a huge trireme catamaran with up to 14 men per oar.[100]

The size of ancient galleys, and fleets, reached their peak in ancient times with the defeat of Mark Antony by Octavian at the battle of Actium. Well-organized contenders for the power over the Mediterranean did not appear again until several centuries later, during the Roman civil wars of the 4th century, and the size of galleys decreased considerably. The huge polyremes disappeared and were replaced by triremes and liburnians, compact biremes with 25 pairs of oars that were well suited for patrol duty and chasing down pirates.[101] In the northern provinces oared patrol boats were employed to keep local tribes in check along the shores of rivers like the Rhine and the Danube.[102] As the need for large warships disappeared, the design of the trireme, the pinnacle of ancient war ship design, was forgotten. The last known reference to triremes in battle is dated to 324 at the battle of the Hellespont. In the late 5th century the Byzantine historian Zosimus declared the knowledge of how to build them to have been long since forgotten.[103]

Middle Ages

Medieval galleys like this pioneered the use of naval guns, pointing forward as a supplement to the above-waterline beak designed to break the enemies outrigger. Only in the 16th century were ships called galleys developed with many men to each oar.[104]

Galley designs were intended solely for close action with hand-held weapons and projectile weapons like bows and crossbows. In the 13th century the Iberian kingdom of Aragon built several fleet of galleys with high castles, manned with Catalan crossbowman, and regularly defeated numerically superior Angevin forces.[105]

- large northern vessels were sailed, most towed or rowed (Unger 1980: 57); Germanic ships (rowing barges) for moving men 24 meters long, similar in proportion to the dromon, clinker built, 15 pairs of oars (Unger 1980: 58)

- Arab navies were based on Byzantine Greek model, used former Byzantine bases in Egypt and Coptic shipbuilders; qarib was the largest Arab warship, a 2-banked galley; the Arabs had less experienced sailors, likely (Unger) had larger ships to carry more troops since they were a land-focused force; flew quadrilateral lateens "short-luff dipping lug sail" (54) (Unger 1980: 53-54)

- very little is known about Muslim galleys, assumed that they were highly similar to those used by Christians, but in general smaller and faster [106]

- galleys of Charles I of Anjou, king of Sicily in 1275 were basically "huge rowing shells" at 10.7:1, 39x3.67m, 80 tons; designed to cut through the water rather than to ride the waves[107]

- King Alfred in England built large rowing boats with 30 oars a side to counter threats from Vikings, up to 40 m long, reportedly "bigger, faster and higher in the water" compared to Viking vessels (Unger 1980: 80)

- Viking ships similar in many ways to galleys, though distinct; extreme cases of 60 oars, though generally much smaller; sailed before the wind, mostly lacked any superstructures and were not armed with catapults, etc; primarily traders and people movers (Unger 1980: 82-94)

- great galleys: lower breadth:length-ratio than warships, high bow to ride waves, higher freeboard, up to three masts with lateens (sometimes a square sail on the mainmast); rowed primarily in and out of harbors, otherwise a sailing vessel; went to Flanders, Egypt, Black Sea, etc; capable of open sea sailing; more room for provisions (or cargo/passengers);[108] after 1292 great galleys could make two round trips per year, but stuck mostly to coastal trunk routes to regularly fill up on provisions, water and "refresh" passengers ("recreation")[109]

- 1:3 of the oars inside of the thole[110]

- English vessels called "galleys" were "major" part of strike force: clinker-built, double-ended, single square sail, some with fighting castles in bow, stern and at mast; little actually known of design, possibly like old Viking ships, but really no conclusive evidence;[111] called "barges/balingers/barks" c. 1350-1500[112]; largely replaced by sailing ships by early 15th century, while remaining important for reconnaissance and patrol[113]

The primary warship of the Byzantine navy until the 12th century was the dromon ("runner" in medieval Greek) and other similar ship types that were evolved from the Roman liburnian. The term first appeared in the late 5th century, and was commonly used for a specific kind of war galley by the 6th century.[114] During the next few centuries, as the naval struggle with the Arabs intensified, heavier versions with two or possibly even three banks of oars evolved.[115] The main developments which differentiated the early dromons from the liburnians, and that henceforth characterized Mediterranean galleys, were the adoption of a full deck, the abandonment of rams on the bow in favor of an above-water spur, and the gradual introduction of lateen sails.[116] It's not clear why the ram disappeared, but one possibility is that it occurred because of the gradual evolution of the ancient shell-first construction method, against which rams had been designed, into the skeleton-first method, which produced a stronger and more flexible hull, less susceptible to ram attacks.[117] At least by the early 7th century, the ram's original function had been forgotten.[118]

The dromons of the 6th century were single-banked ships of probably 25 oars per side. Unlike ancient vessels the oars were no longer supported on an outrigger, but extended directly from the hull.[119] In later bireme dromons of the 9th and 10th centuries, the two oar banks were divided by the deck, with the first oar bank situated below, whilst the second oar bank was situated above deck.[120] The ship was steered by means of two quarter rudders at the stern (prymnē), which also housed a tent that covered the captain's berth.[121] A pavesade on which marines could hang their shields ran around the sides of the ship, providing some protection to the deck crew against missiles.[122] The prow featured an elevated forecastle,[123] while larger ships also had wooden castles on either side between the masts, providing archers with elevated firing platforms.[124] The bow spur was intended to ride over an enemy ship's oars, breaking them and rendering it helpless against missile fire and boarding actions.[125]

From the 12th century, the design of war galleys evolved into the form that would remain largely the same until the building of the last war galleys in the late 18th century. The length to breadth-ratio was a minimum of 8:1. A rectangular telaro, an outrigger, was added to support the oars and the rowers' benches were laid out in a diagonal herringbone pattern angled aft on either side of a central gangway, or corsia.[126] It was based on the form of the galea, the smaller Byzantine galleys, and would be known mostly by the Italian term gallia sottila, "slender galley". A second, smaller mast was added sometime in the 13th century and the number of rowers was rose from two to three rowers per bench as a standard from the late 13th to the early 14th century.[127] The gallee sottili would make up the bulk the main war fleets of every major naval power in the Mediterranean, assisted by the smaller galiotte, as well as the Christian and Muslim corsairs fleets. Ottoman galleys were very similar in design, though in general smaller, faster under sail, but slower under oars.[128] The standard size of the galley remained stable from the 14th until the early 16th century, when the introduction of naval artillery began to have effects on design and tactics.[129]

The traditional two side rudders were complemented with a stern rudder sometime after c. 1400 and eventually the side rudders disappeared altogether.[130] It was also during the 15th century that large artillery pieces were first mounted on galleys. Burgundian records from the mid 15th century describe galleys with some form of guns, but do not specify the size. The first conclusive evidence of a heavy cannon mounted on a galley comes from a woodcut depicting a Venetian galley in 1486.[131] The earliest guns were of large calibers, and were initially of wrought iron, which made them weak compared to cast bronze guns that would become standard in the 16th century. It was fixed directly on timbers in the bow facing directly forwards, a placement that would remain largely unchanged until the galley disappeared from active service in the 19th century.[132]

Early modern

- half-galleys only common among North African corsairs[133]

- galleasses only used by Venice until 1755[134]

(One bench on each side was typically removed to make space for platforms carrying the skiff and the stove.)

The regular galleys carried one 50-pound cannon or a 32-pound culverin at the bow as well as four lighter cannon and four swivel guns. The larger lanterns carried one heavy gun plus six 12 and 6 pound culverins and eight swivel guns.

By the start of the early modern period (c. 1500-1800), the design of galleys had been roughly the same for four centuries. A fairly standardized classification system for different sizes of galleys had also been developed by the advanced Mediterranean bureaucracies, and was based mostly on the number of benches a vessel had.[135]

- so-called lantern galleys, usually used as command ships in action: 30 or more benches

- galleys, the standard war vessels: 20-30 benches

- galiots, used as cruisers or support vessels behind the lines in battles: 15-20 benches, usually with two rowers per oar)

- fustas, similar to galiots in function, but generally smaller than galiots

- brigantines, the smallest type of independently operating cruisers

- fregatas, a support vessel and originally the "ship boat" of galleys

With the introduction of guns in the bows of galleys, a specialized, permanent wooden structure (French: rambade; Italian: rambata; Spanish: arrumbada) that became standard on virtually all galleys during the early 16th century. There were some variations in the navies of different Mediterranean powers,[136] but the general layout was the same. The forward battery was covered by a wooden covering which gave gunners some protection, and functioned as both a staging area and a firing platform for soldiers.

In the mid-17th century, galleys reached what has been described as their "final form". With the exception of a few command galleys, the Mediterranean galleys would have 25-26 pairs of oars with five men per oar (c. 250 rowers). The armament consisted of one 24- or 36-pounder gun in the bows flanked by two to four 4- to 12-pounders. Light swivel guns were placed along the railings for close-quarter defense. The length-to-width ratio was 8:1, with two main masts carrying one large lateen each. One was placed in the bows, stepped slightly to the side to allow the large guns to recoil; the other was placed roughly along the center. A smaller additional mast, a "mizzen" further astern, could be raised if the need and circumstances called for it.[137] In the Baltic, galleys were generally shorter with a length-to-width ratio from 5:1 to 7:1, an adaptation to the cramped conditions of the Baltic archipelagos.[138]

- galleys reached their "final form" in mid-17th century[139]

- 25-26 pairs of oars with 5 men per oar (c. 250), 50-100 sailors, 50-100 soldiers: total of 400-450

- one 24-36 pounder gun, 2-4 4-12 pounders, swivels along railings

- 8:1 length-to-beam ratio; 2 main lateen masts with an extra ("mizzen"?) that could be raised in need

- Swedish galleys shorter in early 18th (5:1), later around 6.5-7:1[140]

- few instances of flagship galleys with up to 30 pairs of oars with 5-7 rowers per oar;[141] dimensions of Swedish and French "super galleys"[142]

- centerline guns recoiled down the corsia; basically the same design for all Mediterranean galleys[143]

- fairly small, but important differences in regional galley design[144]

- Spain: "tactical infantry assault craft"; slower under oars, heavily manned; designed for amphibious raiding and large fleet actions

- North Africans: galleys and galiots; "strategic raiding craft"; faster under oars to allow them to escape pirate patrols; guerilla galleys; ability to outflank fleet battle galleys

- Venice: "heavily armed tactical attack transport": artillery platform designed for standoff actions; faster under oars, slower under sail; good for relieving besieged fortresses

- Ottoman Turks: offensive strategic siege transport/defensive tactical craft; intended to hold off attacking relief fleets while land forces defeated the strongholds on land; fast under oars, decent sailer

- galley "ratings" evolved in the more advanced Mediterranean bureaucracies, mainly based on the number of benches:[145]

- galleass/great galley

- lantern galleys - flagships (30+)

- galleys - standard battle vessels (20+)

- galiots - cruisers (15-20, 2 rowers per oar)

- fustas - cruisers (smaller than galiots?)

- brigantine - small cruisers ()

- fregata - very small cruiser; originally a galley tender/"ship boat"

- galleys required less timber to build and were cheaper (simpler design, fewer guns), especially for small states; flexible for ambushes and amphibious operations; needed few skilled seamen; difficult for sailing ships to catch and important for catching other galleys[146]

- galley (kitchen), where it was actually present, consisted of a clay-lined box that was positioned on one of the benches, usually on the port side[147]

- rambade in French used for bow fighting platform from 16th century until end of galley era[148]

- galeasses developed from the great galleys (but with more guns); used in England to a minor extent but the term was used for much smaller four-masted, broadside ships in Henry VIII's navy with unknown number of oars (oarports below guns); English also used smaller pinnaces, rowbarges[149]

- remo di scaloccio, from scala, "ladder; staircase"[150]

- one (main)mast regular rigging on (war) galleys until c. 1600; a temporary foremast became permanent, stepped to the side of gun recoil; a mizzen mast added in 18th, possibly already in the early 17th century[151]

- Colbert imposed regulations on galley dimensions around 1678-79: about 185 ft long, 22 feet wide at the waterline; with 26 oars per side with 5 men per oar(69); oars for ordinary galleys were 38 ft, larger galleys had 45 ft long oars (70); one heavy 24- or 36-pounder coursier, chaser, gun with another 2-4 in smaller guns, all in the bow; swivel guns were used before but eliminated during Louis XIV since they had little use[152]

- galleys were made more expensive the higher they were ranked (71-72); Patronne middle-large ranked ship; up to 50% more rowers in a réale, r painted white while (with three lanterns) normal French galleys were red (and had only two lanterns) (71) Pierre Puget was the most famous of galley ornamentors and it was was decorated with 109,000 livres for just cloth while a normal galley cost altogether 28,000[153]

- for prestige purposes a galley was according to a report once built, with pre-cut timbers and 500 carpenters working in teams on one side each, caulked, tested and floated in 24 hours to impress the King[154]

- Swedish (somewhat unsuccessful) "super-galleys" (or galleasses) used on the west coast: 48 m long, 30 pairs of oars, 500 men, 3x36-pounders[155]

- half-galleys: 22 m, with 16-18 pairs of oars, armed with 6-pounders used, but only for reconnaissance[156]

- 29 galärer i svenska flottan 1788; 20-22 årpar, 5 man per åra, 1x24p + 2x6p kanoner i fören, ca 250 mans besättning; främst som trupptransporter i skärgården[157]

Construction

Building an efficient galley posed technical problems. The faster a ship travels, the more energy it uses. Through a process of trial and error, the unireme or monoreme — a galley with one row of oars on each side — reached the peak of its development in the penteconter, about 38 m long, with 25 oarsmen on each side. It could reach 9 knots (18 km/h), only a knot or so slower than modern rowed racing-boats. To maintain the strength of such a long craft tensioned cables were fitted from the bow to the stern; this provided rigidity without adding weight. This technique kept the joints of the hull under compression - tighter, and more waterproof. The tension in the modern trireme replica anti-hogging cables was 300 kN (Morrison p198).

Propulsion

Throughout their long history, galleys always relied on rowing as the primary means of propulsion. The arrangement of rowers during the 1st millennium BC developed gradually from a single row up to three rows. Anything above three levels was physically impracticable. Initially, there was only one rower per oar, but the number steadily increased, with a wide variety of arrangements. The ancient classification of galleys was based on the numbers of rows or rowers plying the oars. Today it is best known by modernized Latin terminology based on numerals with the ending "-reme" from rēmus, "oar". A trireme was a ship with three rows of oarsmen, a quadrireme five, a hexareme six, and so forth. There were warships that ran up to ten or eleven rows, but anything above six was rare. A huge forty-rowed ship was built during the reign of Ptolemy IV in Egypt. Little is known about it's design, but it's assumed to have been an impractical prestige vessel.

The ruler Dionysius I of Syracuse (ca. 432–367 BC) is credited with pioneering the "five" and "six", meaning five or six rows of rowers plying two or three rows of oars. Ptolemy II (283-46 BC) is known to have built a large fleet of very large fleets with several experimental designs rowed by everything from 12 up to 40 rows of rowers, though most of these are considered to have been quite impractical.[158]

Ancient rowing was done in a fixed seated position, the most effective rowing position, with rowers facing the stern. A sliding stroke, which would allow for use of the legs as well as the arms, has been suggested by earlier historians, but no conclusive historical evidence has supported it. Practical experiments with the full-scale reconstruction Olympias has shown that not enough space was available, and moving or rolling seats would have been very difficult to construct with ancient methods.[160] Rowers in ancient war galleys sat in an enclosed space below the SHIP SIDES with little view of their surroundings. The rowing was therefore managed by supervisors, and coordinated with pipes or rhythmic chants.[161] Galleys could be highly maneuverable, turning on their axis or even rowing backwards, which required a skilled and experienced crew.[162] In galleys with an arrangement of three men per oar, all would be seated, but the rower furthest inboard would perform a stand-and-sit stroke, getting up on his feet to push the oar forwards and sitting down again to pull it back.[163]

The faster a vessel travels, the more energy it uses and in order to reach higher speeds requires energy which a human-powered vessel is incapable of producing. Oar system generate very low amounts of energy for propulsion (only about 70 W per rower)and the upper limit for rowing in a fixed position lies around 10 knots.(Coates 1995: pp. 127-28) Ancient war galleys of the kind used in Classical Greece are by modern historians considered to be the most efficient of all galleys. A full-scale replica of a 5th century trireme, the Olympias was built in 198? and was used for a series of sea trials to test its performance. It showed that a cruising speed of 7-8 knots that could be maintained for a whole day would have been possible. Sprinting speeds of up to 10 knots were possible, but could only be maintained for a few minutes and took a heavy toll on the crew.(Shaw 1995: 169) Ancient galleys were built very light and the original triremes are assumed to never have been surpassed in speed (Shaw, "Oar Mechanics and Oar Power in Ancient Galleys" in Gardiner 1995: p. 163). Medieval galleys are believed to have been considerably slower since they were not built with ramming tactics in mind. A cruising speed of no more than 2-3 knots has been estimated. A sprint speed of up to 7 knots that could be maintained for no more than 20-30 minutes, but also risked exhausting the rowers completely. (GUILMARTIN? Age of the Galley?)

Rowing in headwinds or even moderately rough weather was difficult as well as exhausting.[164] In high seas, ancient galleys would set up masts with sails to run before the wind. They were highly susceptible to high waves, and could become unmanageable if the rowing frame (apostis) came awash. Ancient and medieval galleys are assumed to sailed only with the wind more or less astern with a top speed of 8-9 knots under fair conditions.[165] In ancient galleys, most of the power came from a singe square sail on a mast rigged a little forwards of the center of the ship with a smaller mast carrying a head sail in the bow. Triangular lateen sails are attested from the 2nd century AD, and gradually became the sail of choice in galleys. By the 9th century it was firmly established as part of the standard galley rig. Though more complicated and requiring a larger crew to handle than a square sail rig, it proved practical in the heavily-manned galleys.[166] Unlike a square sail rig, the spar does not pivot around the mast. To change tack, the entire spar, often much longer than the mast itself, had to be lifted over the mast and over to the other side, a complicated and time-consuming maneuver.[167]

In the latter half of the Middle Ages, large war galleys had three rows of oars, but with all oars on the same level in sets of three to a bench. This layout of oars is best known under the medieval Italian term alla sensile, "in the simple fashion", and relied on skilled oarsmen.

- change recorded around 1300 (same source as Pryor) from two rowers per bench to three[168]

In the 16th century, galley fleet as well as the size of individual vessels increase in size, which required more rowers. The number of benches could not be increased without elongating the ships too much, and more than three oars per bench was not possible. The demand for more rowers also meant that the relatively limited number of skilled oarsmen could was not nearly enough to man all galleys. It became increasingly common to man galleys with convicts or slaves, which required a simpler method of rowing. This resulted in the introduction of a scaloccio rowing, "MEANING WHAT?". A single, much larger oar was used for each bench, with several rowers working it together. The number of oarsmen per oar rose from three up to five or even seven in some very large command galleys.[169]

- alla sensile means "in the simple fashion"[170]

- change from alla sensile to a scaloccio around 1550, allowing larger galleys; lantern galleys with 36 pairs of oars with up to 420 rowers appeared[171]

- small boats tack easily with a lateen rigs (and carracks in general), but with large galleys (esp. great galleys) with yards up to 45 m, 7 t more complicated business[172]

- 10 knots is the upper limit for fixed seat rowing (Coates 1995: 127); "oar systems have very low [energy] densities", 70 W per man and therefore little room for superfluous weight (Coates 1995: 128)

- theoretical speeds: sprinting for 5 minutes, 10 knots; cruising speed, 7,5-8 knots (for a whole day); (Shaw 1995: 169)

- ancient triremes were (likely) never surpassed in speed (Shaw, "Oar Mechanics and Oar Power in Ancient Galleys" in Gardiner 1995: 163)

- sitting down is the most effective rowing position (Shaw 1995: 168)

- with a SIX 3x2; with a FIVE 2x2 + 1x1; no ship had more than three levels because it was physically impracticable; no proof of moving (rolling) seats; (Shaw 1995: 168-169)

- few rowers in ancient trireme could see much and orders by a supervisor was essential, done with chants ryppapai/o opop and pipes; trials proved that certain rythmic melodies conveyed by loudspeakers or collective humming worked[173]

- sliding stroke is possible, but impractical; inconclusive evidence that ancient rowers were advised to use their legs, but it could just be used for a fixed rowing technique; trials with Olympias were not able to produce a practical use of sliding[174]

- rowing backwards could be done in trials by rowing backwards with some skill required (max 3 knots) or simply turning around (5 knots)[175]

- with three men per oar, all might have sat, but the 1 (furthest out) would have done a stand- and-sit stroke; with more than three all would have done a sit-and-stand stroke v

- rowing in rough seas or a headwind is exhausting[176]

- difficult to row even in moderate seas (Shaw 1995: 166-7)

- alla sensile means "in the simple fashion"[177]

- change recorded around 1300 (same source as Pryor) from two rowers per bench to three[178]

- change from alla sensile to a scaloccio around 1550, allowing larger galleys; lantern galleys with 36 pairs of oars with up to 420 rowers appeared[179]

Performance

- galleys highly susceptible to swamping in open seas, in combination with small stores made for limited range[180]

- water among the biggest problems for galley range; at 0.5 gallon per man (a low estimate by Guilmartin (p. 63), agreed by Pryor) stores would not last long; medieval galleys carried 3000-5700 liters (800-1600 gallons);[181] normal water supply of maximum 2-3 weeks, less on merchant galleys which could prioritize cargo or passengers[182]

- Dotson considers the need to be 4 liters per man, reducing the cruising range by half[183]

- sailing season highly limited in Mediterranean: late Spring to early Autumn from antiquity to 15th century; possible, but still largely restricted winter travel rest of year after 15th; coastal trunk routes important to keep close to familiar shores, islands (Balearics, Crete, Corsica/Sardinia) and harbors; all battles clustered around these coasts and strategic bases; wind favored travel from west to east and north to south, opposite direction always slower[184]

- Northern Europe has much more unfriendly waters (and to galleys): dangerous, rocky, gradually shallow shores (unlike sharply deep Mediterranean); difficult tides; violent Atlantic storms; plenty of easy Mediterranean sandy beaches for beaching ships; not until invention of advanced rigging did the North get “fighting chance” to overcome difficulties with sailing ships for both war and trade[185]

- 17th century galleys could carry two months of (bread) rations (50 tons) at the most, but no wine, and that was considered unpractical due to hampered performance; required support fleets to rendezvous with[186]

Crew

- galleys very filthy due to heavy over-crowding; so much that it was believed that it sped up decay by rotting the timbers[187]

- great stench of galleys reputed to be origin for use of perfume by upper-class officers [188]

- 3000 oarsmen required just for the Squadron of Spain under Philip IV; despised as convicts and forzados or Muslim galley slaves (their percentage increased until the 1610s) were driven hard, but were still considered valuable and measures were taken to not allow them to die; lesser crimes were penalized with galley duty to fill gaps; gypsies condemned to row; French POWs employed; sentences prolonged (illegally) to avoid loss of manpower; gypsies also used in French galley force[189]

Rowers

- ventilation essential (as proven by the Olympias experiment) and lack of it is likely to lead to decline in performance; requires louvres on the sides and on top (at least until just before battle)[190]

- water requirements at 2.8 t for 400 men (7 l/man + 2 l for other needs)[191]

Contrary to the popular image of rowers chained to the oars, conveyed by movies such as Ben Hur, there is no evidence that ancient navies ever made use of condemned criminals or slaves as oarsmen, with the possible exception of Ptolemaic Egypt.[192]

The literary evidence indicates that Greek and Roman navies generally preferred to rely on freemen to man their galleys.[193][194] Slaves were put at the oars only in exceptional circumstances. In some cases, these people were given freedom thereafter, while in others they began their service aboard as free men.

In early modern times however, it became the custom among the Mediterranean powers to sentence condemned criminals to row in the war-galleys of the state, initially only in time of war. Galley-slaves lived in very unhealthy conditions, and many died even if sentenced only for a few years - and provided they escaped shipwreck and death in battle in the first place.

Prisoners of war were often used as galley-slaves. Several well-known historical figures served time as galley slaves after being captured by the enemy, the Ottoman corsair and admiral Turgut Reis, the Maltese Grand Master Jean Parisot de la Valette, and the author of Don Quijote, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, among them.

Galleys slaves and convicts

- Roman merchants were manned with slaves (even masters?), but very seldom galleys (Unger 1980: 36)

- "After the Bastille, the galleys were the greatest horror of the old regime." Albert Savine (1909)[195]; the worst conditions were for condemned Protestants, a small minority[196]

- relatively lenient sentence compared to contemporary harsh bodily punishment and prisons that forced captors to pay for everything (while galley oarsmen were fed and under strict, but reasonable regulations)[197]

- semi-"forced" wine-selling on French 17th century galleys with taverns on board run by comites (NCOs resonsible for rowers), a tradition going back to the Middle Ages[198]

- 350-500 men in 170x40-45 feet[199]

- rations of 2 lbs of bread or biscuit, bean soup, oil or lard, some wine[200]

- rowing was difficult, requiring strength, rhythm, cooperation; coordinated with oral commands, drums and physical abuse by supervisors; accidents could lead to severe injuries or even death; frequent exercising was done, even in winter[201]; high mortality, few survived more than a few years; some 20-30 years "or more"[202]

- the term galérien was used as a general term for convicts long after they were forced to serve in galleys, even after 1815[203]

- two galley-convicted Protestants were released in 1775 after serving for 30 years each, at the ages of 58 and 72[204]

- Spain was forced to use mostly servile rowers; Ottomans had the organization/structure in place to mix slaves with volunteers;[205] Venice had mostly free rowers (medieval tradition, alla sensile); Knights of Saint John used slaves extensively, as did Spanish (Habsburg) Italy, Papal State, Florence and Genoa; ghazis relied almost entirely on (Christian) slaves[206]

Contrary to the popular image of rowers chained to the oars, conveyed by movies such as Ben Hur, there is no evidence that ancient navies ever made use of condemned criminals or slaves as oarsmen, with the possible exception of Ptolemaic Egypt.[207]

The literary evidence indicates that Greek and Roman navies generally preferred to rely on freemen to man their galleys.[208] [194] Slaves were put at the oars only in exceptional circumstances. In some cases, these people were given freedom thereafter, while in others they began their service aboard as free men.

In early modern times however, it became the custom among the Mediterranean powers to sentence condemned criminals to row in the war-galleys of the state, initially only in time of war. Galley-slaves lived in very unhealthy conditions, and many died even if sentenced only for a few years - and provided they escaped shipwreck and death in battle in the first place.

Prisoners of war were often used as galley-slaves. Several well-known historical figures served time as galley slaves after being captured by the enemy, the Ottoman corsair and admiral Turgut Reis, the Maltese Grand Master Jean Parisot de la Valette, and the author of Don Quijote, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, among them.

Piracy

- an English purpose-built galley with fifty oars [small galley or galley-frigate?] for pirate hunting stationed at Jamaica from 1683[209]

- Caribbean pirate vessels with oars regularly outran English pirate hunters; lack of sufficient numbers of oar-equipped sloops to run down pirates effectively up to at least the 1720s[210]

- galleys built in Caribbean by Spanish to replace auxiliary galleon (with oars) force to protect against pirates/privateers; for a short time resulted in a system very like the Mediterranean; replaced by larger galleons 1583/84[211]

- Barbary corsairs out of Algiers, Tunis, Tripoli, Morocco (and Morea); fought as holy warriors nominally under Ottoman "suzerainty", Christian galley slaves acquired through slave raids; assisted by Western renegades who served as experts, crewmen, gunners, etc. (some even converted); Knights of Saint Stephen operated out of Leghorn (Legorno?), Knights of Saint John out of Malta, both almost exact opposites of Muslim corsairs; Christian corsairs were manned by 30 or so knights, "paid soldiers" (mercenaries?; p. 47), crew and rowing crew of Muslim slaves, Christian convicts and buonavoglie, "free but normally desperate men who rowed unchained and were regarded as some protection against mutiny by the slaves" (p. 47)[212]

- "mirror image of maritime predation, two businesslike fleets of plunderers set against each other and against the enemies of their faith[s]";[213] both requires/resulted in a complex and vast economic system sustained by piracy and slave raiding;[214] a "massive, multinational protection racket" (recent description in the The Times)[215]

- typical Sallee sailing vessels were almost always equipped with oars and were lightly armed, heavily manned and very fast (fast enough for French admiral Tourville to believe that it took a Sallee prize sold into naval service to catch another Sallee ship)[216]

- Barbary piracy was upheld despite lack [or shrinking] profits[217]

- Christian corsairs finally disbanded by Napoleon in 1798 (after seven centuries of crusading)[218]

- though less romanticized and less famous, Mediterranean corsairs equaled or outnumbered Atlantic and Caribbean (European) pirates[219]

- an English purpose-built galley with fifty oars [small galley or galley-frigate?] for pirate hunting stationed at Jamaica from 1683[220]

- Caribbean pirate vessels with oars regularly outran English pirate hunters; lack of sufficient numbers of oar-equipped sloops to run down pirates effectively up to at least the 1720s[221]

- galleys built in Caribbean by Spanish to replace auxiliary galleon (with oars) force to protect against pirates/privateers; for a short time resulted in a system very like the Mediterranean; replaced by larger galleons 1583/84[222]

- ghazis "resembled" Knights of Saint John[223]

Galleys had likely been employed for piracy in the Mediterranean since early Antiquity, and the predatory activities intensified after the collapse of the Roman Empire. The eastern Mediterranean became a kind of no man's land in the 9th century, located in the middle of the rivalry between the Byzantines and Muslim states. The island of Crete, as a Muslim emirate served as a major base for medieval pirates until it was re-captured by the Byzantines in 960.[224] The Western Mediterranean in the early Middle Ages lacked influence from any major powers, making it even less regulate and prone to piracy, with most of the trade being in more expensive goods (spices, silks, slaves, etc.) in well-defended merchant galleys.[225]

Though less romanticized and less famous than Atlantic and Caribbean pirates, the corsairs Mediterranean equaled or outnumbered them at any given point in history.[226] Mediterranean piracy was conducted almost entirely with galleys until the mid-17th century, when they were gradually replaced with highly maneuverable sailing vessels such as xebecs and brigantines. They were, however, of a smaller type than battle galleys, often referred to as galiots or fustas.[227] Pirate galleys were small, nimble, lightly armed, but often heavily manned in order to overwhelm the often minimal crews of merchant ships. In general, pirate craft were extremely difficult for patrolling craft to actually hunt down and capture. Anne Hilarion de Tourville, a French admiral of the 17th century, believed that the only way to run down raiders from the infamous corsair Moroccan port of Salé was by using a captured pirate vessel of the same type.[228] Using oared vessels to combat pirates was common, and was even practiced by the major powers in the Caribbean. Purpose-built galleys (or hybrid sailing vessels) were built by the English in Jamaica in 1683[229] and by the Spanish in the late 16th century.[230] Specially-built sailing frigates with oar-ports on the lower decks, like the James Galley and Charles Galley, and oar-equipped sloops proved highly useful for pirate hunting, though they were not built in sufficient numbers to check piracy until the 1720s.[231]

The expansion of Muslim power through the Ottoman conquest of large parts of the eastern Mediterraneanin the 15th and 16th century resulted in extensive piracy on sea trading. The so-called Barbary corsairs began to operate out of Algiers, Tunis, Tripoli, Morocco and Morea (modern-day Greece) around 1500, preying primarily on the shipping of Christian powers, including massive slave raids on land as well as at sea. They were nominally under Ottoman suzerainty, but had considerable independence to prey on the enemies of Islam. The Muslim corsairs were technically often privateers with support from legitimate, though highly belligerent, states. But they also considered themselves as holy Muslim warriors, or ghazis,[232] carrying on the tradition of fighting the incursion of Western Christians that had begun with the First Crusade late in the 11th century.[233] The Barbary corsairs had a direct Christian counterpart in the military order of the Knights of Saint John that operated out of Rhodes (Malta after 15??), though they were less numerous and took fewer slaves. Both sides waged war against the respective enemies of their faith, and both used galleys as their primary weapons. Both sides also used captured or bought galley slaves to man the oars of their ships; the Muslims relying mostly on captured Christians, the Christians using a mix of Muslim slaves, Christian convicts and a small contingency of buonavoglie, free men who out of desperation or poverty had taken to rowing.[234] The historian Peter Earle has described the two sides of the conflict as "mirror image[s] of maritime predation, two businesslike fleets of plunderers set against each other"[235]. This conflict of faith in the form of privateering, piracy and slave raiding generated a complex system that was upheld/financed/operated on the trade in plunder and slaves that was generated from a low-intensive conflict, as well as the need for protection from violence. The system has been described as a "massive, multinational protection racket".[236], the Christian side of which was not ended until 1798 in the Napoleonic Wars. The Barbary corsairs were finally quelled as late as the 1830s, effectively ending the last vestiges of counter-crusading.[237]

Strategy

- "inverse relationship between a galley fleet's size and its radius of action"[238]

- Viking tactics were hand-to-hand fighting; common to form defensive formations by lashing ships together side by side; attacks would be at the flanks with both sides feeding in fresh troops from other ships, including smaller craft; leader ships would often have their (larger) bows in front of others to be the first to engage in battle[239]

As floating siege batteries, galleys battered down fort and castle walls quickly at the same time as they could land troop to defeat their garrisons. With an appropriate base and a supporting supply train, they could conduct raids and invasions in a strategic radius of some 3,200 km (2,000 mi).[240] Unlike sailing vessels, the galley themselves were comparatively cheap and therefore expendable. The administrative and financial problem was not in producing enough hulls, but to supply the manpower to row and fight them, both in terms of quantity and quality, and to acquire the extremely expensive artillery to arm them. Before the 1580s, before a sizable arsenal had begun to accumulate, and before the invention of cheaper cast-iron guns, cannons were made from bronze and were quite rare. It was the personnel organizations and administrative structures, as well as the gun arsenals, that were the primary strategic resources during this time, not the galley fleet themselves. In contrast, sailing ship fleets consisted from quite early on of highly complex and expensive vessels with large amounts of artillery with temporary, and relatively more expendable crews.[241]

Tactics

Middle Ages

Later medieval navies continued to use similar tactics, with the line abreast formation as standard. As galleys were intended to be fought from the bows, and were at their weakest along the sides, especially in the middle. The crescent formation continued to be used throughout the Middle Ages as a tactic intended to allow the wings of the fleet to crash their bows straight into the sides of the enemy ships at the edge of the formation.[242]

Early modern

- early modern galleys could move 200 yards in one minute, less time than it took to reload the main guns; fire was held until the last possible moment, similar to infantry tactics with early firearms; often fired with "scatter shot" to maximize death and injury to enemy crew[243]

- line abreast formations moved at most around 2-3 knots (collectively) to hold the formations together; maximum of about 65 galleys in the center and 53-54 on the wings;[244] maximum dash speed of about 7 knots for at most 20 minutes (before rowers became tired to the point of exhaustion)[245]

- advanced signaling systems in place in the 16th century Mediterranean, thanks to old traditions and well-developed organizations[246]

- beaching was done stern first, pointing bow guns out; allowed rowers and crew to escape safely if the galley was threatened, leaving only soldiers and fighting men[247]

- at Prevesa in 1538, it took a whole day to move a galley fleet 20 miles (out of a small gap?)[248]

- control of the nearby shore was critical in a galley battle, making them highly amphibious weapons of war[249]

- forward offensive power of galleys accentuated by guns, tactics remained much the same (but with some stand-off capabilities)[250]

- medieval naval operation were auxiliary to land warfare; transporting armies, supporting army maneuvers; galleys were manned by soldiers who fought with army tactics[251]

Other uses?

- French galleys defended by conservative "friends" despite being criticized as expensive, inefficient and burdened by the reputation as being a tool of the authority to force religious obedience as well as an excuse for keeping slaves[252]

- Louis XIV took charge of the galley fleet and made it a state enterprise, rather than a private or mercenary business[253]

- the French navy was the biggest consumer of construction material in late 17th century[254]

- "embarrassing failure" of reconstruction of a Roman trireme for Napoleon III in 1860-61; too heavily built, oars too long and of different lengths; target practice and sunk by a torpedo[255]