Rodger 2003, p. 230-1, 674-5, 685

A galley is a type of ship that is moved mainly by rowing. From around the 8th century BC up to the early 19th century, it was used in warfare, trade and piracy by various naval powers of Europe, North Africa and Middle East. It was characterized by its long, slender hull and the low clearance between sea and the railing, or freeboard, to make it efficient for propulsion by oars. In warfare it carried various types of weapons, including rams, catapults and cannons, but throughout most of its history, the galley relied primarily on its large crew to overpower enemy vessels in close combat.

Though all types of galleys have had sails to assist rowing, human strength has been the most important method of moving the ship, making it largely independent of winds and currents.

Galleys were used by the ancient Phoenicians, Greeks, Carthaginians and Romans until the 4th century. After the fall of the Roman Empire galleys formed the mainstay of the Byzantine navy and other navies of successors of the Roman Empire, as well as new Muslim navies. Medieval Mediterranean states, notably the Italian maritime republics, including Venice, Pisa, and Genoa, used galleys until the ocean-going man-of-war made them obsolete.

The Battle of Lepanto was one of the largest naval battles in which galleys played the principal part.

Galleys completely dominated naval warfare in the Mediterranean Sea until the 16th century. They were also used in the Atlantic Ocean and the Baltic Sea, though to a lesser degree,since rough seas and higher swells made them less seaworthy than sailing ships. There was also limited use of galleys in waters of the Caribbean and the Philippines by Habsburg Spain and in the Indian Ocean by the Ottoman Empire.

Vessels similar to the galley were common outside the Mediterranean. The longship is the most well known and had the largest impact, being closely associated with the far-reaching raiding and sea trade of the Scandinavian Vikings. Galleys saw extensive use in the coastal areas and sheltered archipelagos of the Baltic until the early 19th century in the conflicts particularly between Denmark, Sweden and Russia. From the 12th to the 16th century, the English employed smaller barges and balingers, in

Galleys were in mainstream use until the introduction of broadside sailing ships of war into the Mediterranean in the 17th Century, but continued to be applied in auxiliary roles until the advent of steam propulsion.

- loss of shipbuilding technology is possible historically, but difficult to prove other than as a negative (Unger 1980: 24)

Definition and terminology

The term “galley” derives from the Medieval Greek galea, a word of unknown origin, possibly from galeos, "dog-fish; small shark".[1][2]

History

Blablabla - early history in Ancient Egypt, Phoencians, etc. Sea People, battle of the Delta

Ancient Mediterranean

- Dionysius of Syracuse invented the 5, 6, 8 and the catapult, Carthaginians 4; Alexander brought 4s and 5s to Babylon and planned 7s (Morrison 66-67)

- Ptolemy II (283-246 BC) had huge fleets with experimental 30s, 20s, 13s and 12s and hundreds of other ships (Morrison 67)

- heavy naval fighting in the PunicWars, Syria vs Egypt [Macedon vs Pergamon/Rhodes employed larger ships] (Morrison 67)

- fives: invented by D. of S.; the first step toward double oar-manning; Roman 5s were "cataphract" and higher (than Carthaginians); Roman types somewhat slow, but better at weathering storms than 4s; believed to have had 2:2:1 oar arrangement (Morrison 68-69)

- sixes: development of 4 (2x3, though unlikely) or 5 by Dyn. I or II, perhaps in 367 BC; probably with a wider hull, only slightly higher than others (though some Romans had towers); no 6 in Athenian fleet; Brutus' flagship, Roman consuls sailed in 6s against Carthage in 256 BC, Ptolemy XII "royal six". Sextus Pompeius met Octavian and Antony near Puteoloi in 39 BC in a "splendid six", 6s largest ships of Octavian at Actium; no record of battle performance, though said to have been slow, of deep draught and with a large compliment of men; the Republic used it for "conspicuous" commanders' ships (Morrison 69-70)

- four: (Morrison 70-71)

- Liburnian: (Morrison 72-73)

- hemiolia:(Morrison 74-76)

- seven: (Morrison 76)

- eight: (Morrison 76)

- nine, ten: (Morrison 77)

- eleven-forty:(Morrison 77)

- first oared warships represented by lead models from Naxos from ca 2500 BC; Minoan (possible) penteconters on a Cretan larnax from 1400-1200 BC (Morrison & Coates, 25); next development occurred around 7th century, with representations (Aristhonotos vase) of fighting between ships with soldiers on the decks, but with the first signs of a ram, possibly a "subsiduary" weapon (Morrison & Coates, 27-28); first battle with ramming described by Herodotos (535 BC) between Phocaean penteconters and Etruscan + Carthaginian ships, assumed to be an "experimental" weapon that allowed Phocaeans to defeat a larger force (60 vs 120) (Morrison & Coates, 28-30; 30)

- biremes, two levels of oars, developed in the 8th century as a way to solve the problem of 25-30 levels or columns per side being the practical upper limit for wooden constructions (Morrison & Coates, 30-32)

- writers in 5th to 16th centuries attempted to explain triremes in their own terms, failing in the process and producing images of impossible constructions due to a lack of understanding of the oar system (Morrison & Coates, 15)

- "embarrassing failure" of reconstruction of a Roman trireme for Napoleon III in 1860-61; too heavily built, oars too long and of different lengths; target practice and sunk by a torpedo (Morrison & Coates, 17-19)

Galleys traversed the Mediterranean from around 3000 BC. The Phoenicians and the Greeks built and operated the first known ships to navigate the Mediterranean: merchant vessels with square-rigged sails. The first military vessels, as described in the works of Homer and represented in paintings, had a single row of oarsmen along each side, in addition to the sail, to provide speed and maneuverability. These were very popular for merchant use.

Early vessels had few navigational tools. Most ancient and medieval shipping remained in sight of the coast for ease of navigation, safety, trading opportunities, and coastal currents and winds that could be used to work against and around prevailing winds. It was more important for galleys than sailing ships to remain near the coast because they needed more frequent re-supply of fresh water for their large, sweating, crews and were more vulnerable to storms. Unlike ships primarily dependent on sails, they could use small bays and beaches as harbors, travel up rivers, operate in water only a meter or so deep, and be dragged overland to be launched on lakes, or other branches of the sea. This made them suitable for launching attacks on land. In antiquity a famous portage was the diolkos of Corinth. In 429 BC (Thucydides 2.56.2), but probably earlier (Herodotus 6.48.2, 7.21.2, 7.97), galleys were adapted to carry horses to provide cavalry support to troops also landed by galleys.

The compass did not come into use for navigation until the 13th century AD, and sextants, octants, accurate marine chronometers, and the mathematics required to determine longitude and latitude were developed much later. Ancient sailors navigated by the sun and the prevailing wind[citation needed]. By the first millennium BC they had started using the stars to navigate at night. By 500 BC they had the sounding lead (Herodotus 2.5).

As ships hugged the coast and threaded through archipelagos rather than risking the open sea, they had to be designed for maneuverability. The ability to travel without regard to the direction or strength of the wind became a sine qua non for daylight expeditions across open water. Massed oars provided maneuverability and reliable propulsion.

”Pentecosters” RAMMING?

The development of the ram in about 800 BC changed the nature of naval warfare, which had until that point involved boarding and hand-to-hand fighting. Now a more maneuverable ship could render a slower ship useless by staving in its sides.

Besides Athlit bronze rams, [3] the only other parts of ancient galleys to survive are parts of two Punic biremes off western Sicily (see Basch & Frost). These Punic galleys are estimated to have been 35 m long, 4.80 m wide, with a displacement tonnage of 120 tonnes. These biremes had evidence of an easily breakable pointed ram, more like the Assyrian image than the Athlit ram. This type of ram may have been designed to break off to protect the ramming vessel from damaging itself.

Galleys were hauled out of the water whenever possible to keep them dry, light and fast and free from worm, rot and seaweed. Galleys were usually overwintered in ship sheds which leave distinctive archeological remains.[4] There is evidence that the hulls of the Punic wrecks were sheathed in lead.

Building an efficient galley posed technical problems. The faster a ship travels, the more energy it uses. Through a process of trial and error, the unireme or monoreme — a galley with one row of oars on each side — reached the peak of its development in the penteconter, about 38 m long, with 25 oarsmen on each side. It could reach 9 knots (18 km/h), only a knot or so slower than modern rowed racing-boats. To maintain the strength of such a long craft tensioned cables were fitted from the bow to the stern; this provided rigidity without adding weight. This technique kept the joints of the hull under compression - tighter, and more waterproof. The tension in the modern trireme replica anti-hogging cables was 300 kN (Morrison p198).

Biremes and triremes

In the 7th or 6th century BC the design of galleys changed. Shipbuilders, probably Phoenician[5] (seafaring people who lived on the southern and eastern coasts of the Mediterranean), added a second row of oars above the first, creating the ship widely known by its Greek name, biērēs (English: bireme). These terms were probably not used until later. The idea was copied around the Mediterranean. Soon afterwards a third row of oars was added, by adding an outrigger to the hull of a bireme. These new galleys were called triērēis ("three-fitted", Sing. triērēs) in Greek; the Romans later called this design the triremis (in English, "trireme"). Thucydides attributes the innovation to the boat-builder Ameinoklēs of Corinth in 700 BC, but some suggest that the design also came from Phoenicia. Herodotus (484 BC - ca. 425 BC) provides the first mention of triremes in action: he mentions that Polycrates, tyrant of Samos from 535 BC to 515 BC, had triremes in his fleet in 539 BC.

In the early 5th century BC the city-states of Greece and the expansionist Persian Empire under Darius (reigned 521 - 485 BC) and Xerxes (reigned 485 - 465 BC) came into conflict.

The Persians hired ships from their Phoenician satrapies. The Athenians defeated the first invasion force on land at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC, but saw the waging of land battles against the more numerous Persians as hopeless in the long term. When news came that Xerxes had started to amass an enormous invasion force in Asia Minor, the Greek cities expanded their navies: in 482 BC the Athenian leader Themistocles started a program for the construction of 200 triremes. The project must have met with considerable success, as 150 Athenian triremes are said to have fought in the Battle of Salamis in 480 BC and participated in the defeat of Xerxes' invasion fleet there.

Triremes fought in the naval battles of the Peloponnesian War (431 - 404 BC), including the Battle of Aegospotami in 405 BC, which sealed the defeat of the Athenian Empire by Sparta and her allies.

Quinqueremes and polyremes

Considerable skill was required to row the ships used at the time of the Peloponnesian War, and there were not enough skilled oarsmen to man large numbers of triremes in the 4th century BC. The search for designs that would allow oarsmen to use muscle-power instead of skill led Dionysius of Syracuse (ruled 405 - 367 BC) to build tetreres (quadriremes) and penteres (quinqueremes).

According to modern historians, the numbers used to describe these larger galleys counted the number of rows of men on each side, and not the numbers of oars. Thus quadriremes had three possible designs: one row of oars with four men on each oar, two rows of oars with two men on each oar or three rows of oars with two men pulling the top oars on each side. Probably galleys of all three designs existed. Scholars believe that quinqueremes had three rows of oars, with two men pulling each of the top two oars.

Along with the change in galley design came an increased reliance on tactics such as boarding and using warships as platforms for artillery. In the wars of the Diadochi (322-281 BC), the successors to the empire of Alexander the Great built increasingly larger galleys. Macedon in 340 BC built sexiremes (probably with two men on each of three oars) and in 315 BC septiremes, which saw action at the Battle of Salamis in Cyprus (306 BC). Demetrius I of Macedon (reigned 294 - 288 BC), involved in a naval war with Ptolemy of Egypt (reigned 323 - 283 BC), built eights (octeres), nines, tens, twelves and finally sixteens. Later Ptolemies continued this trend of expansion, creating twenties and thirties and, during the reign of Ptolemy IV, a huge forty over 400 feet long that was probably intended as a showpiece. According to a detailed description of the forty, the ship had two prows and two sterns, and this and other evidence has led some to believe that the forty, and probably the twenties and thirties, were constructed like huge catamarans with enough space between the hulls for the rowers in the middle to operate. The deck above them, stretching across the two hulls, could accommodate a couple of thousand marines.[citation needed]

The last mention of triremes come from Zosimus in 324, when Constantine's son Crispus defeated Licinius at the battle of the Hellespont. Allegedly 200 triremes were defeated by 80 thrity-oared vessels (Morrisson p8 who gives the wrong year).

Roman era

- after Actium, the Roman fleet was at its peak, largely dismantled and burned; no major actions until the 4th century; Roman bases established at Ravenna and Miseneum (Rankov, 78)

- few large polyremes, minimum of decisive naval actions (with most civil wars fought on land); sailors were employed in entertainment mock battles and in handling Coliseum awnings; fleet crews were treated as auxiliaries; sailors called themselves milites (soldiers) not nautea (sailors); though commanders were powerful with pays of up to 200,000 sesterces/year, rank of knights (Prefects), eg Pliny the Elder at Vesuvius 79 AD (Rankov, 79-80)

- provincial Roman fleets were smaller, but fought more often; active in rivers and as far as the Baltic; one indecisive battle known in revolt of Civilis in 70 AD at the Island of the Batavians where a trireme served as a Roman flagship (Rankov, 80-81)

- river bases in Central Europe, fort chains along northern coasts, like Britain; bases: Trabzon, Vienna, Belgrade, Cologne, Dover, Boulogne, Noviodunum, Seleucia, Alexandria (Rankov, 82-84)

- invasions and civil wars from the 160s and onwards; fleets fighting barbarians, campaigns of Marc Aurelius; Italian fleets fought contenders for the power in 3rd century; the last provincial fleet was the classis Britannica which was reduced to impotence by late 3rd; upswing during Constantine, when he defeated Licinius' with 80 triaconters vs 200 triremes (!); after 324 the trireme disappeared, the design and technology forgotten (Rankov, 82-85)

Late antiquity(?)

- two types of Roman ships: galleys and merchants (Unger 1980: 34)

- after the Romans had conquered most of the Mediterranean only light Liburnians were needed – equipped with one oar bank, ram (?), one mast with square sail, bow headsail (Unger 1980: 34-35)

- Roman merchants were manned with slaves (even masters?), but very seldom galleys (Unger 1980: 36)

- Romans built (like Greeks) with mortise and tenon joints; hulls of malleable wood (cypress); keel, posts, tenons of hardwood (oak) (Unger 1980: 36-37)

- mortise and tenon technique exclusive to Greeks and Romans; "excessively strong" ships, watertight w/o caulking; war, tarred fabric and lead sheathing (Unger 1980: 39)

- economy fell after Roman collapse; but the Byzantine Empire sponsored sea trade and focused less on land transports; galleys were employed for importing luxuries because of their high speed, which set off the high cost of maintenance when transporting expensive goods (Unger 1980: 40)

- less expensive building technology; more fragile, but faster; after 600 came a "major step" towards skeleton construction, though not completely (Unger 1980: 41-42)

- hull protection (lead sheathing) abandoned, though uses for warships in the 10th century (Unger 1980: 42)

- feature of Byzantine warships essentially established by 600: larger than Roman, slower, less cargo space, larger crews, more firepower (Unger 1980: 43) 6:1 ratio, two-banked (2x25 oars per side), 40-50 x 5 m; minimum of one man per oar; 1.5 meter draught; flat bottom amidships; shields on the sides (like Vikings); no stringers, strengthened by strakes and wales; MORE TO BE GOT IF NEEDED AND SOURCE IS RELIABLE (Unger 1980: 43-45)

- merchants were used in the navy; 500 transports for 92 warships against the Vandals in 533 (Unger 1980: 46)

- merchant galleys were "beamier" than dromons, but were sometimes pressed into the navy (Unger 1980: 46)

- bulk trade was carried by small "coasters" seldom over 300 tons; bulk trade fell 600-750 while luxuries rose and were increasingly carried by merchant galleys (Unger 1980: 47)

- lateen sail became established in the Mediterranean during this period and was completely dominant by 800 (the date from when the first Byzantine illustration of one is known); demanded large crews, which were readily available on the galleys (Unger 1980: 47-49)

- explanation of how a lateen sail works; leading edge does not pivot on the mast; the spar needs to be lifted (carried) over the mast for it to come over to the other tack (?)(Unger 1980: 49)

- the Western Mediterranean was less organized than the Eastern; more pirate activity, more trade in luxuries and less coastal trade; spices, silks, etc imported, slaves and “sylvan” products (and timber) exported (Unger 1980: 51)

- barrels replaced amphorae by 7th century; loss of space fell from 40 % to 10 %, ships could be made smaller (or carry more) (Unger 1980: 51-52)

- Arab navies were based on Byzantine Greek model, used former Byzantine bases in Egypt and Coptic shipbuilders; qarib was the largest Arab warship, a 2-banked galley; the Arabs had less experienced sailors, likely (Unger) had larger ships to carry more troops since they were a land-focused force; flew quadrilateral lateens "short-luff dipping lug sail" (54) (Unger 1980: 53-54)

- competition between the Byzantines and Arabs from the 7th to the 9th; as competition fiercened, ships became heavier(Unger 1980: 55)

- Romans had galleys in the North, but they disappeared after their withdrawal in 3rd-5th; Celtic curraghs: 12 m skin boats with a sail and oars (Unger 1980: 56)

- large northern vessels were sailed, most towed or rowed (Unger 1980: 57); Germanic ships (rowing barges) for moving men 24 meters long, similar in proportion to the dromon, clinker built, 15 paris of oars (Unger 1980: 58)

- cogs and hulks were used for carrying trade in the North (Unger 1980: 61-63)

- collapse of Carolingian empire lead to lowered stability, worsened by Scandinavian raids up until 1000; more stability by 1000 through emergence of Christian kingdoms (France, Germany, Hungary, Poland); Italian port towns rose on the fringes of the Byzantine Empire as it struggled with eastern threats (Unger 1980: 75-76)

- King Alfred in England built large rowing boats with 30 oars a side to counter threats from Vikings, up to 40 m long, reportedly “bigger, faster and higher in the water” compared to Viking vessels (Unger 1980: 80)

- Viking ships similar in many ways to galleys, though distinct; extreme cases of 60 oars, though generally much smaller; sailed before the wind, mostly lacked any superstructures and were not armed with catapults, etc; primarily traders and people movers (Unger 1980: 82-94)

- large differences between South and North: differing hull designs, steering systems, propulsion; both had trade dominated by luxuries, but in the North it was mostly manufactured goods while South concentrated on silks and spices from Asia (South had much higher total value per unit of volume) (Unger 1980: 95-96)

- the Eastern Mediterranean in the 9th century became a no man's land between Byzantine and Muslim navies with Crete in the middle as a base for pirates (until the recapture of Crete in 960) (Unger 1980: 96-97)

- Arabs suffered from an acute shortage of timber in the late 10th century after the loss of Crete to the Byzantines; timber embargoes and shortage led to a major decline of shipwrights in Fatimid Egypt; worsened by Italian competition who could lower prices and had no lack of timber (Unger 1980: 99-100)

- piracy in the 10th changed from coastal raids to attacking ships at sea, making it more difficult to deal with by authorities; merchants in all of the Mediterranean reacted by using larger vessels with larger crews, galleys, especially for luxuries; Italian city-states (Pisa, Genoa, Venice) were forced to build navies; they, especially Venice, inherited Byzantine designs, but had larger superstructures (castles), but no catapults; by 10th century like a dromon, "but lower, wider and faster" (103) with crews of up 1,000 men "and more", originally designed for war, but employed as traders as well (Unger 1980: 102-103)

- new large galleys were well-suited for carrying expensive merchandises (spices) and pilgrims; the rise of pilgrimages to the Holy Land pushed up trade (Unger 1980: 103-104)

Middle Ages

- Viking raids in the 9th century led to founding of an Iberian navy (under Muslims) (Lawrence V. Mott, "Iberian Naval Power, 1000-1650" in Hattendorf & Unger 2003: 105)

- galleys were the most common warships in the Atlantic until the 14th century by Iberian powers (Lawrence V. Mott, "Iberian Naval Power, 1000-1650" in Hattendorf & Unger 2003: 105-106)

- Aragon fleet in the 13th century built galleys with high castles, armed with Catalan crossbowman; regularly defeated the numerically superior Angevin fleet (Lawrence V. Mott, "Iberian Naval Power, 1000-1650" in Hattendorf & Unger 2003: 107)

- a Castilian raid on Jersey in 1405 (during the Hundred Years War) was one of the first (?) major battles where most ships were cogs or nefs, not galleys; but galleys remained the mainstay in the South (Lawrence V. Mott, "Iberian Naval Power, 1000-1650" in Hattendorf & Unger 2003: 109)

- the battle of Gibraltar in 1476 was a transition point; most of the combattants were full-rigged ships armed with wrought-iron guns on the upper decks in the waists; marks the dominance of sailing ships in the Atlantic and North Sea (Lawrence V. Mott, "Iberian Naval Power, 1000-1650" in Hattendorf & Unger 2003: 111)

- small cannon on Castilian and Aragonese vessels in 14th century; an inventory of Alfonso V's fleet sent to Naples in 1419 contains some galleys armed with bombardas and two with two cannons each (Lawrence V. Mott, "Iberian Naval Power, 1000-1650" in Hattendorf & Unger 2003: 111)

- Turks contested Portuguese dominance in the Indian Ocean in the 16th century, but failed because they used Mediterranean-style galleys against carracks (eventhough they were becoming outdated by the time) (Lawrence V. Mott, "Iberian Naval Power, 1000-1650" in Hattendorf & Unger 2003: 112)

- galleys "sporadically" used by Spain in Netherlands, Bay of Biscay and the Caribbean (Lawrence V. Mott, "Iberian Naval Power, 1000-1650" in Hattendorf & Unger 2003: 113-114)

- build in Caribbean and Philippines by Spanish to "run down marauders" (Bamford 1973: 12)

Typical specifications

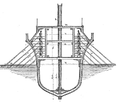

The earliest galley specification comes from an order of Charles I of Sicily, in 1275 AD (Bass & Pryor). Overall length 39.30 m, keel length 28.03 m, depth 2.08 m. Hull width 3.67 m. Width between outriggers 4.45 m. 108 oars, most 6.81 m long, some 7.86 m, 2 steering oars 6.03 m long. Foremast and middle mast respectively heights 16.08 m, 11.00 m; circumference both 0.79 m, yard lengths 26.72 m, 17.29 m. Overall deadweight tonnage approximately 80 metric tons. This type of vessel had two, later three, men on a bench, each working his own oar. This vessel had much longer oars than the Athenian trireme which were 4.41 m & 4.66 m long (Morrison p269). This type of warship was called galia sottil (Landström). According to Landström, the Medieval galleys had no rams as boarding was considered more important method of warfare than ramming.

Medieval galleys like this pioneered the use of naval guns, pointing forward as a supplement to the above-waterline beak designed to break the enemies outrigger. Only in the 16th century were ships called galleys developed with many men to each oar (Pryor p67).

City Museum of Rimini, Italy

At the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, the standard Venetian war galleys were 42 m long and 5.1 m wide (6.7 m with the rowing frame), had a draught of 1.7 m and a freeboard of 1.0 m, and weighed empty about 140 tons. The larger flagship galleys (or lanterns) were 46 m long and 5.5 m wide (7.3 m with the rowing frame), had 1.8 m draught and 1.1 m freeboard. and weighed 180 tons. The standard galleys had 24 rowing benches on each side, with three rowers to a bench. (One bench on each side was typically removed to make space for platforms carrying the skiff and the stove.) The crew typically comprised 10 officers, about 65 sailors, gunners and other staff plus 138 rowers. The lanters had 27 benches on each side, with 156 rowers, and a crew of 15 officers and about 105 other sailors, gunners and soldiers. The regular galleys carried one 50-pound cannon or a 32-pound culverin at the bow as well as four lighter cannon and four swivel guns. The larger lanterns carried one heavy gun plus six 12 and 6 pound culverins and eight swivel guns.

Northern Europe

There is good archaeological evidence for Dark Age northern galleys from ship burials, unlike ancient Mediterranean galleys. The most stunning is the Gokstad ship. A development of the Viking longships and knarrs, medieval north European galleys, clinker-built, used a square sail and rows of oars, and looked very like their Norse predecessors.

In the waters off the west of Scotland between 1263 and 1500, the Lords of the Isles used galleys both for warfare and for transport around their maritime domain, which included the west coast of the Scottish Highlands, the Hebrides, and Antrim in Ireland. They employed these ships for sea-battles and for attacking castles or forts built close to the sea. As a feudal superior, the Lord of the Isles required the service of a specified number and size of galleys from each holding of land. For examples the Isle of Man had to provide six galleys of 26 oars, and Sleat in Skye had to provide one 18-oar galley.

Carvings of galleys on tombstones from 1350 onwards show the construction of these boats. From the 14th century they abandoned a steering-oar in favour of a stern rudder, with a straight stern to suit. From a document of 1624, a galley proper would have 18 to 24 oars, a birlinn 12 to 18 oars and a lymphad fewer still.

Early modern period

- not a single galley battle between France and Spain 1660-1700, virtually no battles with other nations either (Bamford 1973: 45)

- Bamford considers galleys to have been outclassed by sailing vessels; sails could only be beat under particular circumstances (becalmed and/or outnumbered and surrounded) and by letting their guard down; galleys were a waste of resources militarily (instead of going to sailing vessels), though good for "trade and harbor defense" and effective for projecting prestige (Bamford 1973: 46-47)

France

- in early 17th century France, "the administrative language of the day" made a strict distinction between marine (navy) and galères (galleys), with "navy" meaning sailing ships; the distinction disappeared in the 1650s when a modern navy emerged (Hattendorf "Introduction" in Hattendorf & Unger 2003: 20)

- galleys used by pirates and for hunting pirates in the Mediterranean; hired by merchants as cheap defense (Bamford 1973: 17-18)

- galleys well-suited as prestige vessels; they were "obedient" and could participates in maneuvers, rituals and "pageantry"(Bamford 1973: 24-25)

- galleys consumed funds better spent on more powerful sailing vessels, but were maintained as prestige tools acc

- 25% of navy expenditure in 1662 went to galleys; 50% in 1663 (Bamford 1973: 23)

- Louis XIV took charge of the galley fleet and made it a state enterprise, rather than a private or mercenary business (Bamford 1973: 68-69)

- the French navy was the biggest consumer of construction material in late 17th century (Bamford 1973: 89)

- the Galley Corps consumed 20-25% of the navy budget in the last three decades of the 17th century; greatly expanded man power and officer corps; over 70 million livres on galleys while 300 million on the entire navy, 30 million in the 1690s alone (Bamford 1973: 93-94)

- after the end of rivalry between France and Spain with the death of Charles II and the War of the Spanish Succession, the Galley Corps shrunk from 55 (1690) to 40 (1700); after Louis XIV 26 (1716), 15 (1718-48); Corps abolished in 1748; North Africans, Order of Saint John, Papacy cut down on galleys more drastically (Bamford 1973: 272-73)

- Colbert imposed regulations on galley dimensions around 1678-79: about 185 ft long, 22 feet wide at the waterline; with 26 oars per side with 5 men per oar(69); oars for ordinary galleys were 38 ft, larger galleys had 45 ft long oars (70); one heavy 24- or 36-pounder coursier, chaser, gun with another 2-4 in smaller guns, all in the bow; swivel guns were used before but eliminated during Louis XIV since they had little use (Bamford 1973: 69-71)

- galleys were made more expensive the higher they were ranked (71-72); Patronne middle-large ranked ship; up to 50% more rowers in a réale, r painted white while (with three lanterns) normal French galleys were red (and had only two lanterns) (71) Pierre Puget was the most famous of galley ornamentors and it was was decorated with 109,000 livres for just cloth while a normal galley cost altogether 28,000 (Bamford 1973: 72)

- for prestige purposes a galley was according to a report once built, with pre-cut timbers and 500 carpenters working in teams on one side each, caulked, tested and floated in 24 hours to impress the King (Bamford 1973: 76-77)

- crash program of galley construction 1662-90, from half a dozen to over 40 (Bamford 1973: 78); extensive use of green, unseasoned, timber shortened service life of galleys considerably; late 17th century French galleys was no more than ten years, on average 4,5 in 1978 (Bamford 1973: 79-80); 18th century galleys averaged over 14 years of service (Bamford 1973: 84)

- decline after 1715, and in consequence better timber (Bamford 1973: 86)

Decline

The decline of the galley was extremely protracted, beginning before the development of cannon and continuing slowly for centuries. As early as 1304 the type of ship required by the Danish defence organization changed from galley to cog, a flat-bottomed sailing ship (Bass p191). Large high-sided sailing ships had always been very formidable obstacles for galleys. As early as 413 BC defeated triremes could seek shelter behind a screen of merchant ships (Thucydides (7, 41), Needham 4, pt3, p693). The late 15th century saw the development of the ocean-going trader and warship, beginning with the carrack, which evolved into the galleon and then into the square rigger. These warships carried advanced sails and rigging that permitted tacking into the wind, and were heavily armed with cannons.

In the Mediterranean, the decline of the galley began at around 1595–1605. This began with an influx of Dutch merchantment in the 17th century. These were so heavily armed and manned and sufficiently seaworthy that they could compete simultaneously by trade and privateering. Venetian galleys could barely cope with their piracy in summer, and could not cope with it at all in the winter (Tenenti). Militarily, the sailing ship eventually rendered the galley obsolete except for operations close to shore in calm weather. In the ocean the dominance of the sailing ship became apparent with the Portuguese victory at the battle of Diu in 1509. The slow transition in the Mediterranean began with the action of 14 July 1616, when a small Spanish fleet of galleons defeated a large Ottoman fleet of galleys. But the escape of the galleys to avoid destruction also illustrates the continued advantages of these craft in the fickle conditions of the Mediterranean. By the 1660s even a purely Mediterranean power like Venice began building men-of-war.

By the end of the 17th century, when Captain Kidd christened his privateering ship the Adventure Galley, galleys were no longer the mainstay in major battles, but as Kidd's choice shows, remained useful as fast and nimble privateering and coastal raiding vessels.

In America they were used in the battle of Valcour Island in 1776. Galleys were also used during the Revolutionary War by whalers who used their ships to raid British shipping along the American coast. These raiding parties were useful in supplying the Continental Army with many much needed supplies. [ARE THESE REALLY GALLEYS?]

Galleys remained a mainstay of North African corsair fleets and continued to play a significant role in the Mediterranean well into the 18th century. They made one of their final appearances in a Mediterranean battle in the Battle of Chesma in 1770; they lingered on in the shallow Baltic Sea and took part in the Russo-Swedish War in 1790. Galleys were used, ineffectively, by the Knights of Malta during Napoleon's siege of Valetta in 1798. The last war galleys were constructed in 1796 for the Russian navy as a countermeasure to arch rival in the Baltic Sea, the Swedish Archipelago Navy. The Swedish navy still retained 27 galleys in 1809, and the last Swedish-built galley remained on the ship rolls until 1835, before it was retired at an age of 86 years.

Design

- galleys required less timber to built and were cheaper (simpler, fewer guns) especially for small states; were flexible for ambushes and amphibious operations; needed few skilled seamen; difficult for sailing ships to catch and important for catching other galleys (Bamford 1973: 14-16)

- ancient triremes were (likely) never surpassed in speed (Shaw, "Oar Mechanics and Oar Power in Ancient Galleys" in Gardiner 1995: 163)

- oars made from silver fur by stripping layers (Shaw 1995: 163)

- a giant forty built by Ptolemy Philopater, believed to have had twin hulls like a giant catamaran; impractical showpiece (Shaw 1995: 164-165)

- theoretical speeds: sprinting for 5 minutes, 10 knots; cruising speed, 7,5-8 knots (for a whole day); (Shaw 1995: 169)

- with three men per oar, all might have sat, but the 1 (furthest out) would have done a stand- and-sit stroke; with more than three all would have done a sit-and-stand stroke (Shaw 1995: 170)

- with a SIX 3x2; with a FIVE 2x2 + 1x1; no ship had more than three levels because it was physically impracticable; no proof of moving (rolling) seats; (Shaw 1995: 168-169)

Galliots and fustas

The galliot emerged as a smaller, lighter type of galley. The number of oars or sweeps varied from 18 to 22 per side, the larger ones having twenty-five on each side.

The fusta or fuste, likewise, was in essence a small galley -- a narrow, light and fast ship with shallow draft, powered by both oars and sail. It had 12 to 15 two-man rowing benches on each side, and a single mast with a lateen (triangular) sail. The fusta was the favorite ship of the North African corsairs of Salé and the Barbary Coast. Its speed, mobility, capability to move without wind, and its ability to operate in shallow water made it an ideal vessel for war and piracy.

Mechanics of rowing

- sitting down is the most effective rowing position (Shaw 1995: 168)

- difficult to row even in moderate seas (Shaw 1995: 166-7)

Rowing arrangements

Armament

Rigging?

Crew

Galleys slaves and convicts

- galleys very filthy due to heavy over-crowding; so much that it was believed that it sped up decay by rotting the timbers (Bamford 1973: 83-84)

- "After the Bastille, the galleys were the greatest horror of the old regime." Albert Savine (1909) (Bamford 1973: 105); the worst conditions were for condemned Protestants, a small minority (11-12)

- relatively lenient sentence compared to contemporary harsh bodily punishment and prisons that forced captors to pay for everything (while galley oarsmen were fed and under strict, but reasonable regulations) (Bamford 1973: 26-28)

Contrary to the popular image of rowers chained to the oars, conveyed by movies such as Ben Hur, there is no evidence that ancient navies ever made use of condemned criminals or slaves as oarsmen, with the possible exception of Ptolemaic Egypt.[6]

The literary evidence indicates that Greek and Roman navies generally preferred to rely on freemen to man their galleys.[7] [8] Slaves were put at the oars only in exceptional circumstances. In some cases, these people were given freedom thereafter, while in others they began their service aboard as free men.

- semi-"forced" wine-selling on French 17th century galleys with taverns on board run by comites (NCOs resonsible for rowers), a tradition going back to the Middle Ages (Bamford 1973: 207)

- 350-500 men in 170x40-45 feet (Bamford 1973: 208)

- rations of 2 lbs of bread or biscuit, bean soup, oil or lard, some wine (Bamford 1973: 203)

- rowing was difficult, requiring strength, rhythm, cooperation; coordinated with oral commands, drums and physical abuse by supervisors; accidents could lead to severe injuries or even death; frequent exercising was done, even in winter (Bamford 1973: 220-222); high mortality, few survived more than a few years; some 20-30 years "or more" (Bamford 1973: 224)

In early modern times however, it became the custom among the Mediterranean powers to sentence condemned criminals to row in the war-galleys of the state, initially only in time of war. Galley-slaves lived in very unhealthy conditions, and many died even if sentenced only for a few years - and provided they escaped shipwreck and death in battle in the first place.

Prisoners of war were often used as galley-slaves. Several well-known historical figures served time as galley slaves after being captured by the enemy, the Ottoman corsair and admiral Turgut Reis, the Maltese Grand Master Jean Parisot de la Valette, and the author of Don Quijote, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, among them.

Warfare

Tactics

(Cultural/Economic/Social) Impact?

Trading

- Lionel Casson identifies a split between war and merchant galleys in the 9th century BC (?), when rams were introduced (Casson, "Merchant Galleys" in Gardiner 1995: 117)

- merchant galleys useful for guaranteed transport, shallow draught that could hug the shore (Casson, "Merchant Galleys" in Gardiner 1995: 118), first examples are Egyptian river boats from Old Kingdom (2700-2200 BC); sea-going galleys in New Kingdom under Hatshepsut (c. 1479-1457) that shipped incense, myrrh in Red Sea (so shallow the cargo in illustrations is on deck) (Casson, "Merchant Galleys" in Gardiner 1995: 118)

- Phoenicians had transport galleys which were markedly stubbier, "bowl-shaped" and fewer oars; Carthaginian wrecks off western coast of Sicily from 3rd or 2nd century BC carrying (estimated 30x5 m: 6:1, between sailing vessels 4:1 and war galleys 10:1); very few merchant galleys perserved since they carried only light, valuable cargoes that did not preserve the hull underneath them (Casson, "Merchant Galleys" in Gardiner 1995: 118-19)

- most information is from Greeks and later Romans; histiokopos "sail-oar-er" and actuaria (navis) "ship that moves", since it could always make some progress (Casson, "Merchant Galleys" in Gardiner 1995: 119) a single broad square sail equipped with the standard ancient rigging brails which bunched up the sail similar to a venetian blind; large galleys may also have hade an artemon, a type of foresail on a mast slanted over the bow; merchant galleys carried valuable or perishable cargoes, like gladitorial animals, honey, cheese, meat; Cato the Elder held up a fig during the famous "Carthago delenda est" and claimed it had been picked in North Africa only three days ago (Casson, "Merchant Galleys" in Gardiner 1995: 121)

- akatos/actuaria among the largest and most versatile, carried up to 50 rowers; lembos/lembus used as express carriers (biggest carried only 25 tons of oil); phaselos/phaselus ("bean pod") used for passanger transport; kybaia/cybaea ("cubic") of only 5:1 length ratio; these types continued in use until the Middle Ages (Casson, "Merchant Galleys" in Gardiner 1995: 121-123) Viking longships described by Casson as galleys and were dominant in North European shipping in the early and high Middle Ages (Casson, "Merchant Galleys" in Gardiner 1995: 123)

- high point of the merchant galley was the "great galleys" of the Venetian Republic, initiated in 1294: galleys with full-sized complement of oarsmen, but with more canvas, longer/deeper/wider and with more room for cargo; from 40.3x5.3x2.5 m (132x17x8 ft), 140 tons and 25x2x3 rowers to 46x8x3 m (151x26x10 ft), 250 tons and 30x2x3 rowers; carried expensive goods like spices, silks, gems; later common to transport rich pilgrims to the Holy Land (but with 2 per bench), went from Venice to Jaffa in 29 days (18 at sea, 11 on land; usual was 40-50 in total), up to 300 people in total in fairly harsh conditions (Casson, "Merchant Galleys" in Gardiner 1995: 123-126)

- difficult route with Flemish cloth by "galleys of Flanders" Venice-Gibraltar-Atlantic coast-London-Bruges; great galleys peaked in mid-16th century and was then out-competed by more efficient sailing vessels, the sea routes to Asia lost Venice its geographical trade advantage (Casson, "Merchant Galleys" in Gardiner 1995: 126)

From the first half of the fourteenth century the Venetian galere da mercato the "merchantman galley" was being built in the shipyards of the state-run Arsenal as "a combination of state enterprise and private association, the latter being a kind of consortium of export merchants", as Fernand Braudel described them.[9] The ships sailed in convoy, defended by archers and slingsmen (ballestieri) aboard, and later carrying cannon.

In the 14th and 15th centuries merchant galleys traded high-value goods and carried passengers. Major routes in the time of the early Crusades carried the pilgrim traffic to the Holy Land. Later routes linked ports around the Mediterranean, between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea (a grain trade soon squeezed off by the Turkish capture of Constantinople, 1453) and between the Mediterranean and Bruges— where the first Genoese galley arrived at Sluys in 1277, the first Venetian galere in 1314— and Southampton. Although primarily sailing vessels, they used oars to enter and leave many trading ports of call, the most effective way of entering and leaving the Lagoon of Venice. The Venetian galere, beginning at 100 tons and built as large as 300, was not the largest merchantman of its day, when the Genoese carrack of the fifteenth century might exceed 1000 tons.[10] In 1447, for instance, Florentine galleys planned to call at 14 ports on their way to and from Alexandria (Pryor p57). The availability of oars enabled these ships to navigate close to the shore where they could exploit land and sea breezes and coastal currents, to work reliable and comparatively fast passages against the prevailing wind. The large crews also provided protection against piracy. These ships were very seaworthy; a Florentine great galley left Southampton on 23 February 1430 and returned to its port at Pisa in 32 days. They were so safe that merchandise was often not insured (Mallet). These ships increased in size during this period, and were the template from which the galleass developed.

Tactics, uses, applications

- 17th century galleys could carry two months of (bread) rations (50 tons) at the most, but no wine, and that was considered unpractical due to hampered performance; required support fleets to rendezvous with (Bamford 1973: 35)

Armament

Research

Archaeology

Surviving vessels

The naval museum in Istanbul contains the galley Kadırga (Turkish for "galley"), dating from the reign of Mehmed IV (1648–1687). It was the personal galley of the sultan, and remained in service until 1839. Kadırga is presumably the only surviving galley in the world, albeit without its masts. It is 37 m long, 5.7 m wide, has a draught of about 2 m, weighs about 140 tons, and has 48 oars that were powered by 144 oarsmen.

A 1971 reconstruction of the Real, the flagship of Don Juan de Austria in the Battle of Lepanto 1571, is in the Museu Marítim in Barcelona. The ship was 60 m long and 6.2 m wide, had a draught of 2.1 m, weighing 239 tons empty, was propelled by 290 rowers, and carried about 400 crew and fighting soldiers at Lepanto. She was substantially larger than the typical galleys of her time.

A group called "The Trireme Trust" operates, in conjunction with the Greek Navy, a reconstruction of an ancient Greek Trireme, the Olympias.[11]

In the mid of 1990s, a sunked galley was found close to the island of San Marco in Boccalama, in the Venice Lagoon.[12] The relic is mostly intact and it was not recovered due to high costs.

Images

-

File:PhoenicianCoin2A.jpg

Notes

- ^ Galeos, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, at Perseus project

- ^ Galley, Online Etymology Dictionary

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ Casson, Lionel (December 1 1995). Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World. The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-0801851308.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Casson, Lionel (1971). Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 325–326.

- ^ Rachel L. Sargent, "The Use of Slaves by the Athenians in Warfare", Classical Philology, Vol. 22, No. 3 (Jul., 1927), pp. 264-279

- ^ Lionel Casson, "Galley Slaves", Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 97 (1966), pp. 35-44

- ^ Braudel, The Perspective of the World, vol. III of Civilization and Capitalism (1979) 1984:126.

- ^ Fernand Braudel, The Mediterranean in the Age of Philip II I, 302.

- ^ The Trireme Trust

- ^ * AA.VV., 2002, La galea ritrovata. Origine delle cose di Venezia, Venezia * AA.VV., 2003, La galea di San Marco in Boccalama. Valutazioni scientifiche per un progetto di recupero (ADA - Saggi 1), Venezia * CAPULLI M. - FOZZATI L., 2005, "Le navi della Serenissima: archeologia e restauro (XIII°-XVI° sec.)", in Rotte e porti del Mediterraneo dopo la caduta dell’Impero d’Occidente, IV seminario ANSER (Genova giugno 2004), Soveria Mannelli. * D'AGOSTINO M., 1998, Relitti di età post-classica nell'alto Adriatico italiano. Relazione preliminare, in Archeologia Medievale, XXV 1998, pp. 91-102 * D'AGOSTINO M. - MEDAS S., 2003, I relitti dell'isola di San Marco in Boccalama, Venezia. Rapporto preliminare, in Atti del II Convegno nazionale di Archeologia Subacquea. Castiglioncello, 7-9 settembre 2001, Edipuglia, Bari, pp. 99-106 * D'AGOSTINO M. - MEDAS S., 2003, Laguna di Venezia. Lo scavo e il rilievo dei relitti di San Marco in Boccalama. Notizia preliminare, in Atti del III Congresso Nazionale di Archeologia Medievale, Salerno 2-5 ottobre 2003, Ed. All'Insegna del Giglio, Firenze, pp. 224-227 * D'AGOSTINO M. - MEDAS S., 2003, Excavation and Recording of the medieval Hulls at San Marco in Boccalama (Venice), in the INA Quarterly (Institute of Nautical Archaeology), 30, 1, Spring 2003, pp. 22-28 * D'AGOSTINO M. - MEDAS S., 2006, I relitti medievali di San Marco in Boccalama. Campagna di scavo e rilievo 2001, in NAVIS 3, pp. 59-67

References

- Bamford, Paul W., Fighting ships and prisons : the Mediterranean Galleys of France in the Age of Louis XIV. Cambridge University Press, London. 1974. ISBN 0-8166-0655-2

- Casson, Lionel, "Galley Slaves" in Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 97 (1966), pp. 35-44

- Casson, Lionel, "The Age of the Supergalleys" in Ships and Seafaring in Ancient Times, University of Texas Press, 1994. ISBN 029271162X[3], pp. 78-95

- Guilmartin, John Francis, Gunpowder and Galleys: Changing Technology and Mediterranean Warfare at Sea in the Sixteenth Century. Cambridge University Press, London. 1974. ISBN 0-521-20272-8

- Hattendorf, John B. & Unger, Richard W. (editors), War at Sea in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Woodbridge, Suffolk. 2002. ISBN 0-85115-903-6[4]

- Hutchinson, Gillian, Medieval Ships and Shipping. Leicester University Press, London. 1997. ISBN 0-7185-0117-9

- Morrison, John S. & Gardiner, Robert (editors), The Age of the Galley: Mediterranean Oared Vessels Since Pre-Classical Times. Conway Maritime, London, 1995. ISBN 0-85177-554-3

KB

- Pryor, John H. & Jeffreys, Elizabeth, The Age of the Dromon: The Byzantine Navy ca. 500-1204. Brill, Leiden. 2006. 90-04-15197-4

- Casson, Lionel, The Ancient Mariners: Seafarers and Sea Fighters of the Mediterranean in Ancient Times. Princeton University Press, Princeton. 1991. ISBN 978-0691014777 (SUB)

- Friel, Ian, The Good Ship: ships, shipbuilding and technology in England, 1200-1520. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. 1995. ISBN 0-7141-0574-0

- Rodgers, William Ledyard, Naval Warfare Under Oars, 4th to 16th Centuries: A Study of Strategy, Tactics and Ship Design. United States Naval Institute, Annapolis, Maryland. 1939.

- Lane, Frederic Chapin, Venetian ships and shipbuilders of the Renaissance, (New edition), Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. 1992 [1934]. ISBN 0-8018-4514-9[5]

- Mallett, Michael E., The Florentine Galleys in the Fifteenth Century: With the Diary of Luca di Maso degli Albizzi, Captain of the galleys 1429-1430. Clarendon Press, Oxford. 1967.

- Morrison, John Sinclair & Coates, John F., The Athenian trireme: the history and reconstruction of an ancient Greek warship. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. 1986. ISBN 0-521-32202-2 (SU)

- Pryor, John H., Geography, Technology, and War: Studies in the Maritime History of the Mediterranean, 649–1571 Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. 1991 0-521-42892-0[6]

- Unger, Richard W. The Ship in Medieval Economy 600-1600 Croom Helm, London. 1980. ISBN 0-85664-949-X (SU, VA)

SU

- Template:Sv Norman, Hans (red.), Skärgårdsflottan: uppbyggnad, militär användning och förankring i det svenska samhället 1700-1824. Historiska media, Lund. 2000. ISBN 91-88930-50-5

- Westerdahl, Christer, Crossroads in ancient shipbuilding: proceedings of the sixth International symposium on boat and ship archaeology, Roskilde 1991. Oxbow, Oxford. 1994. ISBN 0-946897-70-0

SH

VA

- Michael Wedde, "On the alleged connection between the early Greek galley and the watercraft of the Nordic rock art" (pp. 57-71) in European Association of Archaeologists. Meeting, The Aegean Bronze Age in relation to the wider European context: papers from a session at the eleventh annual meeting of the European Association of Archaeologists, Cork, 5-11 September 2005. Archaeopress, Oxford. 2008. ISBN 978-1-4073-0187-7

- Casson, Lionel, Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World. Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, Baltimore, Md, 1995[1971] ISBN 0-8018-5130-0

- Coates, John F. & Morrison, John Sinclair (editors), An Athenian trireme reconstructed: the British sea trials of Olympias, 1987. B.A.R., Oxford. 1989. ISBN: 0-86054-623-3

- Gardiner, Robert, The archaeology of medieval ships and harbours in northern Europe: papers based on those presented to an International symposium on boat and ship archaeology at Bremerhaven in 1979. Oxford, 1979. ISBN: 0-86054-068-5

SSM

- Lehmann, L. Th., Galleys in the Netherlands. Meulenhoff, Amsterdam. 1984. ISBN: 90-290-1854-2

- Gardiner, Robert & Unger, Richard W. (editors), Cogs, Caravels and Galleons: The Sailing Ship 1000-1650. Conway Maritime Press, London. 1994. ISBN 0-85177-560-8

- Symonds, Craig L., New aspects of naval history: selected papers presented at the fourth Naval history symposium, United States Naval academy, 25-26 October 1979 Naval Inst. P., Annapolis. 1981. ISBN 0-87021-495-0 (ALB)

GU

UU

- Anderson, Roger Charles, Oared fighting ships: From classical times to the coming of steam. London. 1962.

previous

- George F. Bass, ed., A History of Seafaring, Thames & Hudson, 1972

- L.Basch & H. Frost Another Punic wreck off Sicily: its ram International journal of Nautical Archaeology vol 4.2, 201-228, 1975

- Bicheno, Hugh, Crescent and Cross: The Battle of Lepanto 1571, Phoenix Paperback, London, 2004, ISBN 1-84212-753-5

- Lionel Casson, Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World, Princeton University Press, 1971

- H.Frost et al. Lilybaeum supplement to Notizae Scavi d'Anichita 8th ser vol 30 1981 (1971)

- Brian Lavery, Maritime Scotland, B T Batsford Ltd., 2001, ISBN 0-7134-8520-5

- Michael E. Mallett, The Florentine Galleys in the Fifteenth Century, Oxford, 1967

- J.S.Morrison et al., The Athenian Trireme 2000 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press

- John H. Pryor Geography, Technology and War, Cambridge University Press, 1988

- Alberto Tenenti, Piracy and the Decline of Venice 1580-1615, English transl. 1967

- William Ledyard Rodgers, Admiral, Naval Warfare Under Oars: 4th to 16th Centuries, Naval Institute Press, 1940.

External links

- John F. Guilmartin, "The Tactics of the Battle of Lepanto Clarified: The Impact of Social, Economic, and Political Factors on Sixteenth Century Galley Warfare". A very detailed discussion of galley warfare at the Battle of Lepanto

- Rafael Rebolo Gómez - "The Carthaginian navy"., 2005, Treballs del Museu Arqueologic d'Eivissa e Formentera.

- "The Age Of The Galley: Mediterranean Oared Vessels Since Pre-Classical Times", 2000, Conway's History of the Ship series, ISBN 978-0785812685.

- Boris Rankov, "Fleets of the Early Roman Empire, 31 BC-AD 324", pages 78-85

- J T Shaw, "Oar Mechanics and Oar Power in Ancient Galleys", pages 163-171

- Mauro Bondioli, René Burlet & André Zysberg, "Oar Mechanics and Oar Power in Medieval and Later Galleys", pages 172-205

- Lionel Casson, "Merchant Galleys", pages 117-126

- "Some Engineering Concepts applied to Ancient Greek Trireme Warships", John Coates, University of Oxford, The 18th Jenkin Lecture, 1 October 2005.

- The Boccalama's galley in Venice