79.97.222.210 (talk) Undid revision 644249644 by Mabuska (talk) these changes improve that paragraph |

|||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

)<!-- note. The definite article is ALWAYS used as part of the term. WP includes it in names of articles where it is part of the name and not merely a grammatical usage. --> is the common name for the [[Ethnic nationalism|ethno-nationalist]]<ref name=CMitchell>{{cite book |last=Mitchell |first=Claire |title=Religion, Identity and Politics in Northern Ireland |publisher=Ashgate Publishing |year=2013 |page=5 |quote=The most popular school of thought on religion is encapsulated in McGarry and O'Leary's ''Explaining Northern Ireland'' (1995), and is echoed by Coulter (1999) and Clayton (1998). The central argument is that religion is an ethnic marker, but that it is not generally politically relevant in and of itself. Instead, ethnonationalism lies at the root of the conflict. Hayes and McAllister (1999a) point out that this represents something of an academic consensus.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last = McGarry|first = John|author2 = Brendan O'Leary|title = Explaining Northern Ireland|publisher = Wiley-Blackwell|date = 15 June 1995|page = 18|isbn = 978-0-631-18349-5}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title = Northern Ireland and the Politics of Reconciliation|editor = Dermot Keogh|publisher = Cambridge University Press|date = 28 January 1994|pages = 55–59|isbn = 978-0-521-45933-4}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url = http://www.passia.org/seminars/2004/John-Coakley-Ireland-Seminar.htm|title = ETHNIC CONFLICT AND THE TWO-STATE SOLUTION: THE IRISH EXPERIENCE OF PARTITION|last = Coakley|first = John|accessdate = 15 February 2009|quote=...these attitudes are not rooted particularly in religious belief, but rather in underlying ethnonational identity patterns.}}</ref> conflict in [[Northern Ireland]] that spilled over at various times into the [[Republic of Ireland]], [[England]] and [[Continental Europe|mainland Europe]]. The Troubles [[The Troubles#Late 1960s|began in the late 1960s]] and is deemed by many to have ended with the [[Good Friday Agreement|Belfast "Good Friday" Agreement]] of 1998,<ref name="Ireland 1999, page 221"/><ref>''The Politics of Northern Ireland: Beyond the Belfast Agreement'' by Arthur Aughey (ISBN 978-0415327886), page 7</ref><ref>''Historical Dictionary of the Northern Ireland Conflict'' by Gordon Gillespie (ISBN 978-0810855830), page 250</ref><ref>Elliot, Marianne: ''The Long Road to Peace in Northern Ireland: Peace Lectures from the Institute of Irish Studies at Liverpool University.'' University of Liverpool Institute of Irish Studies, Liverpool University Press, 2007, page 2. ISBN 1-84631-065-2</ref><ref>Goodspeed, Michael: ''When reason fails: Portraits of armies at war: America, Britain, Israel, and the future.'' Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002, pp. 44 and 61. ISBN 0-275-97378-6</ref> although there has been sporadic violence since then.<ref name="Ireland 1999, page 221"/><ref>{{cite web|url = http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/issues/violence/deathsfrom2002draft.htm|title = Draft List of Deaths Related to the Conflict. 2002–|accessdate = 31 July 2008}}</ref><ref>Elliot, page 188</ref> Internationally, the Troubles is also commonly called the '''Northern Ireland conflict'''<ref name="Gloss">[http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/othelem/glossary.htm#T A Glossary of Terms Related to the Conflict]. [[Conflict Archive on the Internet]] (CAIN). Quote: "The term 'the Troubles' is a euphemism used by people in Ireland for the present conflict. The term has been used before to describe other periods of Irish history. On the CAIN web site the terms 'Northern Ireland conflict' and 'the Troubles', are used interchangeably."</ref><ref>McEvoy, Joanne. ''The Politics of Northern Ireland''. Edinburgh University Press, 2008. p.1. Quote: "the Northern Ireland conflict, known locally as 'the Troubles', endured for three decades and claimed the lives of more than 3,500 people".</ref><ref>David McKittrick & David McVea. ''Making Sense of the Troubles: A History of the Northern Ireland Conflict''. Penguin, 2001.</ref><ref>Gillespie, Gordon. ''The A to Z of the Northern Ireland Conflict''. Scarecrow Press, 2009.</ref><ref>Aaron Edwards & Cillian McGrattan. ''The Northern Ireland Conflict: A Beginner's Guide''. Oneworld Publications, 2012.</ref> and has been described as a war.<ref>{{cite web|title = Who Won The War? Revisiting NI on 20th anniversary of ceasefires|url = http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-29369805|publisher = BBC|accessdate = 26 September 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url = http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/northern_ireland/7249681.stm|title = Troubles 'not war' motion passed|publisher = News.bbc.co.uk|date = 18 February 2008|accessdate = 2009-03-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url = https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5_Yr6i0_9Hs#t=435|title = Frost over the World - Ian Paisley - 28 Mar 08 - "7:19 Paisley Describes Troubles As War"|publisher = youtube.com, AlJazeera|date = 28 March 2008|accessdate = 2009-03-26}}</ref> |

)<!-- note. The definite article is ALWAYS used as part of the term. WP includes it in names of articles where it is part of the name and not merely a grammatical usage. --> is the common name for the [[Ethnic nationalism|ethno-nationalist]]<ref name=CMitchell>{{cite book |last=Mitchell |first=Claire |title=Religion, Identity and Politics in Northern Ireland |publisher=Ashgate Publishing |year=2013 |page=5 |quote=The most popular school of thought on religion is encapsulated in McGarry and O'Leary's ''Explaining Northern Ireland'' (1995), and is echoed by Coulter (1999) and Clayton (1998). The central argument is that religion is an ethnic marker, but that it is not generally politically relevant in and of itself. Instead, ethnonationalism lies at the root of the conflict. Hayes and McAllister (1999a) point out that this represents something of an academic consensus.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last = McGarry|first = John|author2 = Brendan O'Leary|title = Explaining Northern Ireland|publisher = Wiley-Blackwell|date = 15 June 1995|page = 18|isbn = 978-0-631-18349-5}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title = Northern Ireland and the Politics of Reconciliation|editor = Dermot Keogh|publisher = Cambridge University Press|date = 28 January 1994|pages = 55–59|isbn = 978-0-521-45933-4}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url = http://www.passia.org/seminars/2004/John-Coakley-Ireland-Seminar.htm|title = ETHNIC CONFLICT AND THE TWO-STATE SOLUTION: THE IRISH EXPERIENCE OF PARTITION|last = Coakley|first = John|accessdate = 15 February 2009|quote=...these attitudes are not rooted particularly in religious belief, but rather in underlying ethnonational identity patterns.}}</ref> conflict in [[Northern Ireland]] that spilled over at various times into the [[Republic of Ireland]], [[England]] and [[Continental Europe|mainland Europe]]. The Troubles [[The Troubles#Late 1960s|began in the late 1960s]] and is deemed by many to have ended with the [[Good Friday Agreement|Belfast "Good Friday" Agreement]] of 1998,<ref name="Ireland 1999, page 221"/><ref>''The Politics of Northern Ireland: Beyond the Belfast Agreement'' by Arthur Aughey (ISBN 978-0415327886), page 7</ref><ref>''Historical Dictionary of the Northern Ireland Conflict'' by Gordon Gillespie (ISBN 978-0810855830), page 250</ref><ref>Elliot, Marianne: ''The Long Road to Peace in Northern Ireland: Peace Lectures from the Institute of Irish Studies at Liverpool University.'' University of Liverpool Institute of Irish Studies, Liverpool University Press, 2007, page 2. ISBN 1-84631-065-2</ref><ref>Goodspeed, Michael: ''When reason fails: Portraits of armies at war: America, Britain, Israel, and the future.'' Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002, pp. 44 and 61. ISBN 0-275-97378-6</ref> although there has been sporadic violence since then.<ref name="Ireland 1999, page 221"/><ref>{{cite web|url = http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/issues/violence/deathsfrom2002draft.htm|title = Draft List of Deaths Related to the Conflict. 2002–|accessdate = 31 July 2008}}</ref><ref>Elliot, page 188</ref> Internationally, the Troubles is also commonly called the '''Northern Ireland conflict'''<ref name="Gloss">[http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/othelem/glossary.htm#T A Glossary of Terms Related to the Conflict]. [[Conflict Archive on the Internet]] (CAIN). Quote: "The term 'the Troubles' is a euphemism used by people in Ireland for the present conflict. The term has been used before to describe other periods of Irish history. On the CAIN web site the terms 'Northern Ireland conflict' and 'the Troubles', are used interchangeably."</ref><ref>McEvoy, Joanne. ''The Politics of Northern Ireland''. Edinburgh University Press, 2008. p.1. Quote: "the Northern Ireland conflict, known locally as 'the Troubles', endured for three decades and claimed the lives of more than 3,500 people".</ref><ref>David McKittrick & David McVea. ''Making Sense of the Troubles: A History of the Northern Ireland Conflict''. Penguin, 2001.</ref><ref>Gillespie, Gordon. ''The A to Z of the Northern Ireland Conflict''. Scarecrow Press, 2009.</ref><ref>Aaron Edwards & Cillian McGrattan. ''The Northern Ireland Conflict: A Beginner's Guide''. Oneworld Publications, 2012.</ref> and has been described as a war.<ref>{{cite web|title = Who Won The War? Revisiting NI on 20th anniversary of ceasefires|url = http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-29369805|publisher = BBC|accessdate = 26 September 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url = http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/northern_ireland/7249681.stm|title = Troubles 'not war' motion passed|publisher = News.bbc.co.uk|date = 18 February 2008|accessdate = 2009-03-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url = https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5_Yr6i0_9Hs#t=435|title = Frost over the World - Ian Paisley - 28 Mar 08 - "7:19 Paisley Describes Troubles As War"|publisher = youtube.com, AlJazeera|date = 28 March 2008|accessdate = 2009-03-26}}</ref> |

||

The conflict was primarily a political one, but it also had an ethnic or sectarian dimension,<ref>Storey, Michael L. (2004). ''Representing the Troubles in Irish Short Fiction''. p. 149</ref> although it was not a religious conflict.<ref name=CMitchell/><ref name=RJenkins>{{cite book |last=Jenkins |first=Richard |title=Rethinking Ethnicity: Arguments and Explorations |publisher=SAGE Publications |year=1997 |page=120 |quote=It should, I think, be apparent that the Northern Irish conflict is not a religious conflict... Although religion has a place—and indeed an important one—in the repertoire of conflict in Northern Ireland, the majority of participants see the situation as primarily concerned with matters of politics and nationalism, not religion. And there is no reason to disagree with them.}}</ref> A key issue was the [[Partition of Ireland|constitutional status of Northern Ireland]]. [[Unionism in Ireland|Unionists]]/[[Ulster loyalism|loyalists]], who are mostly Protestants, generally want Northern Ireland to remain within the United Kingdom. [[Irish nationalism|Irish nationalists]]/[[Irish republicanism|republicans]], who are mostly Catholics, generally want it to leave the United Kingdom and join a [[united Ireland]]. Another key issue was the relationship between these two communities. The conflict began amidst a [[Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association|campaign to end discrimination]] against the Catholic/nationalist minority by the Protestant/unionist-dominated government and police force.<ref>''The State:Historical and Political Dimensions'', Richard English: Charles Townshend, 1998, Routledge, ISBN 0415154774, p. 96</ref><ref name="pp">Orange Parades: The Politics of Ritual, Tradition and Control by Dominic Bryan, Pluto Press (2000) ISBN 0-7453-1413-9 p. 94</ref> Another grievance was the [[Operation Demetrius|introduction of internment]] (imprisonment without trial) and the interrogation of internees by the [[five techniques]], which was initially only used against nationalists. |

|||

The main [[Directory of the Northern Ireland Troubles|participants]] in the Troubles were republican paramilitaries (such as the [[Provisional Irish Republican Army|Provisional IRA]]), loyalist paramilitaries (such as the [[Ulster Volunteer Force|UVF]] and [[Ulster Defence Association|UDA]]), the British state security forces (the [[British Army]] and the [[Royal Ulster Constabulary|RUC]], Northern Ireland's police force), and political activists and politicians. The Republic of Ireland's security forces played a smaller role. More than 3,500 people were killed in the conflict. |

The main [[Directory of the Northern Ireland Troubles|participants]] in the Troubles were republican paramilitaries (such as the [[Provisional Irish Republican Army|Provisional IRA]]), loyalist paramilitaries (such as the [[Ulster Volunteer Force|UVF]] and [[Ulster Defence Association|UDA]]), the British state security forces (the [[British Army]] and the [[Royal Ulster Constabulary|RUC]], Northern Ireland's police force), and political activists and politicians. The Republic of Ireland's security forces played a smaller role. More than 3,500 people were killed in the conflict. |

||

Revision as of 22:16, 26 January 2015

| The Troubles | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Political map of the island of Ireland | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

State security forces

|

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

|

British Army: 705[6] Irish Army: 1 Gardaí: 9 IPS: 1[6] (total: 11) |

PIRA: 291[6] INLA: 39[6] OIRA: 27[6] IPLO: 9[6] RIRA: 2[6] (total: 368) |

UDA: 91[6] UVF: 62[6] RHC: 4[6] LVF: 3[6] UR: 2[7] (total: 162) | ||||||

|

Total dead: 3,530[8] Total injured: 47,500+[9] All casualties: 50,000+[10] | ||||||||

The Troubles (Irish: Na Trioblóidí ) is the common name for the ethno-nationalist[11][12][13][14] conflict in Northern Ireland that spilled over at various times into the Republic of Ireland, England and mainland Europe. The Troubles began in the late 1960s and is deemed by many to have ended with the Belfast "Good Friday" Agreement of 1998,[3][15][16][17][18] although there has been sporadic violence since then.[3][19][20] Internationally, the Troubles is also commonly called the Northern Ireland conflict[21][22][23][24][25] and has been described as a war.[26][27][28]

The conflict was primarily a political one, but it also had an ethnic or sectarian dimension,[29] although it was not a religious conflict.[11][30] A key issue was the constitutional status of Northern Ireland. Unionists/loyalists, who are mostly Protestants, generally want Northern Ireland to remain within the United Kingdom. Irish nationalists/republicans, who are mostly Catholics, generally want it to leave the United Kingdom and join a united Ireland. Another key issue was the relationship between these two communities. The conflict began amidst a campaign to end discrimination against the Catholic/nationalist minority by the Protestant/unionist-dominated government and police force.[31][32] Another grievance was the introduction of internment (imprisonment without trial) and the interrogation of internees by the five techniques, which was initially only used against nationalists.

The main participants in the Troubles were republican paramilitaries (such as the Provisional IRA), loyalist paramilitaries (such as the UVF and UDA), the British state security forces (the British Army and the RUC, Northern Ireland's police force), and political activists and politicians. The Republic of Ireland's security forces played a smaller role. More than 3,500 people were killed in the conflict.

Overview

"The Troubles" refers to the three decades of violence between elements of Northern Ireland's Irish nationalist community (mainly self-identified as Irish and/or Roman Catholic) and its unionist community (mainly self-identified as British and/or Protestant). The term "the Troubles" was previously used to refer to the Irish War of Independence of 1919-21;[33] it was adopted to refer to the escalating violence in Northern Ireland after 1969.[34] The conflict was the result of discrimination against the Irish nationalist/Catholic minority by the unionist/Protestant majority[35] and the question of Northern Ireland's status within the United Kingdom.[36][37] The violence was characterised by the armed campaigns of Irish republican and Ulster loyalist paramilitary groups. These included the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) campaign of 1969–1997, intended to end British rule in Northern Ireland and to reunite Ireland politically and thus create a 32-county Irish Republic; and of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), formed in 1966 in response to the perceived erosion of both the British character of, and unionist domination of, Northern Ireland.[citation needed] The state security forces—the British Army and the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC)—were also involved in the violence. It thus became the focus for the longest major campaign in the history of the British Army.[38][39]

The British government's view was that its forces were neutral in the conflict, trying to uphold law and order in Northern Ireland and the right of the people of Northern Ireland to democratic self-determination. Irish republicans, however, regarded the state forces as forces of occupation and combatants in the conflict, noting collusion between the state forces and the loyalist paramilitaries. The "Ballast" investigation by the Police Ombudsman has confirmed that British forces—and in particular the RUC—did on several occasions collude with loyalist paramilitaries, were involved in murder, and furthermore obstructed the course of justice when claims of collusion and murder were investigated.[40] The extent of collusion is still hotly disputed. Unionists claim that reports of collusion were either false or highly exaggerated and that there were also instances of collusion between the authorities of the Republic of Ireland and republican paramilitaries.

Alongside the violence, there was a political deadlock between the major political parties in Northern Ireland—including those who condemned violence—over the future status of Northern Ireland and the form of government there should be therein.

The Troubles were brought to an uneasy end by a peace process that included the declaration of ceasefires by most paramilitary organisations, the complete decommissioning of the IRA's weapons, the reform of the police, and the corresponding withdrawal of the British Army from the streets and sensitive border areas such as South Armagh and Fermanagh, as agreed by the signatories to the Belfast Agreement (commonly known as the "Good Friday Agreement"). The agreement reiterated the long-held British position, which successive Irish governments have not fully acknowledged, that Northern Ireland would remain within the United Kingdom, unless a majority of Northern Irish vote otherwise.

On the other hand, the British government recognised for the first time the principle that the people of the island of Ireland as a whole have the right, without any outside interference, to solve the issues between North and South by mutual consent.[41] The latter statement was key to winning support for the agreement from both nationalists and republicans. It also established a devolved power-sharing government within Northern Ireland (which was suspended from 14 October 2002 until 8 May 2007), wherein the government must consist of both unionist and nationalist parties.

Though the number of active participants in the Troubles was relatively small, the Troubles touched the lives of many in Northern Ireland on a daily basis, while occasionally spreading to the Republic of Ireland and England.[42]

Background

1609–1912

In 1609, Scottish and English settlers, known as planters, were given land confiscated from the native Irish in the Plantation of Ulster.[43] Coupled with Protestant immigration to "unplanted" areas of Ulster, particularly Antrim and Down, this resulted in conflict between the native Catholics and the "planters", leading in turn to two bloody ethno-religious conflicts known as the Irish Confederate Wars (1641–1653) and the Williamite war (1689–1691), both of which resulted in Protestant victories.

British Protestant political dominance in Ireland was ensured by the passage of the penal laws that curtailed the religious, legal, and political rights of anyone (including both Catholics and [Protestant] Dissenters, such as Presbyterians) who did not conform to the state church, the Anglican Church of Ireland.

As the penal laws broke down in the latter part of the 18th century, there was more competition for land, as restrictions were lifted on the Catholic Irish ability to rent. With Roman Catholics allowed to buy land and enter trades from which they had formerly been banned, tensions arose resulting in the Protestant "Peep O'Day Boys"[44] and Catholic "The Defenders". This created polarisation between the communities and a dramatic reduction in reformers within the Protestant community which had been growing more receptive to ideas of democratic reform.

Following the foundation of the nationalist-based Society of the United Irishmen by Presbyterians, Catholics, and liberal Anglicans, and the resulting failed Irish Rebellion of 1798, sectarian violence between Catholics and Protestants continued. The Orange Order (founded in 1795), with its stated goal of upholding the Protestant faith and loyalty to William of Orange and his heirs, dates from this period and remains active to this day.[45]

In 1801, a new political framework was formed with the abolition of the Irish Parliament and incorporation of Ireland into the United Kingdom. The result was a closer tie between the former, largely pro-republican Presbyterians and Anglicans as part of a "loyal" Protestant community. Though Catholic Emancipation was achieved in 1829, in large part by Daniel O'Connell, largely eliminating official discrimination against Catholics (around 75% of Ireland's population), Jews, and Dissenters, O'Connell's long-term goals of Repeal of the 1801 Union and Home Rule were never achieved. The Home Rule movement served to define the divide between most nationalists (often Catholics), who sought the restoration of an Irish Parliament, and most unionists (often Protestants), who were afraid of being a minority in a Catholic-dominated Irish Parliament and tended to support continuing union with Britain. Unionists and Home-Rule advocates countered each other during the career of Charles Stuart Parnell, a repealer, and onwards.[46]

1912–1922

By the second decade of the 20th century, Home Rule, or limited Irish self-government, was on the brink of being conceded due to the agitation of the Irish Parliamentary Party. In response, unionists, mostly Protestant and concentrated in Ulster, resisted both self-government and independence for Ireland, fearing for their future in an overwhelmingly Catholic country dominated by the Roman Catholic Church. In 1912, unionists led by Edward Carson signed the Ulster Covenant and pledged to resist Home Rule by force if necessary. To this end, they formed the paramilitary Ulster Volunteers and imported arms from Germany (the Easter Rising insurrectionists did the same several years later).

Nationalists formed the Irish Volunteers, whose ostensible goal was to oppose the Ulster Volunteers and ensure the enactment of the Third Home Rule Bill in the event of British or unionist recalcitrance. The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 temporarily averted possible civil war and delayed the resolution of the question of Irish independence. Home Rule, though passed in the British Parliament with Royal Assent, was suspended for the duration of the war.

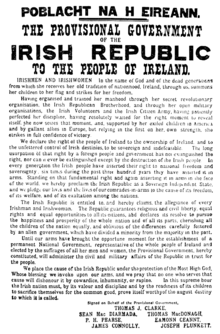

Following the nationalist Easter Rising in Dublin in 1916 by the Irish Republican Brotherhood, and the executions of fifteen of the Rising's leaders, the separatist Sinn Féin party won a majority of seats in Ireland and set up the First Dáil (Irish Parliament) in Dublin. Their victory was aided by the threat of conscription to the British Army. Ireland essentially seceded from the United Kingdom. The Irish War for Independence followed, leading to eventual independence for the Republic of Ireland. In Ulster, however, and particularly in the six counties which became Northern Ireland, Sinn Féin fared poorly in the 1918 election, and Unionists won a strong majority.

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 partitioned the island of Ireland into two separate jurisdictions, Southern Ireland and Northern Ireland, both devolved regions of the United Kingdom. This partition of Ireland was confirmed when the Parliament of Northern Ireland exercised its right in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 to opt out of the newly established Irish Free State.

A part of the treaty signed in 1922 stated that a boundary commission would sit in due course to decide where the frontier of the northern state would be in relation to its southern neighbour. With the two key signatories from the South of Ireland dead during the Irish Civil War of 1922–23, this part of the treaty was given less priority by the new Southern Irish government led by Cosgrave, and was quietly dropped.

The idea of the boundary commission was to include as many of the nationalist and loyalist communities in their respective states as fairly as possible. As counties Fermanagh and Tyrone and border areas of Londonderry, Armagh, and Down were mainly nationalist, the boundary commission could have rendered Northern Ireland untenable, as at best a four-county state and possibly even smaller.

Northern Ireland remained a part of the United Kingdom, albeit under a separate system of government whereby it was given its own Parliament and devolved government. While this arrangement met the desires of unionists to remain part of the United Kingdom, nationalists largely viewed the partition of Ireland as an illegal and arbitrary division of the island against the will of the majority of its people. They argued that the Northern Ireland state was neither legitimate nor democratic, but created with a deliberately gerrymandered unionist majority. Catholics initially composed about 33% of its population.[47]

Northern Ireland came into being in a violent manner – a total of 557 people were killed in political or sectarian violence from 1920 to 1922, during and after the Irish War of Independence, mostly Catholics.[48] (See also; Irish War of Independence in the North East.) The result was communal strife between Catholics and Protestants, with nationalists characterising this violence, especially that in Belfast, as a "pogrom" against their community, although one historian argues that the reciprocity of northern violence does not fit the pogrom model or imagery so well.[49]

1922–1966

A legacy of the Irish Civil War, later to have a major impact on Northern Ireland, was the survival of a marginalised remnant of the Irish Republican Army. It was illegal in both Irish states and ideologically committed to overthrowing them both, by force of arms, to re-establish the Irish Republic of 1919–1921. In response, the Northern Irish government passed the Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act (Northern Ireland) 1922; this gave sweeping powers to the government and police to do virtually anything seen as necessary to re-establish or preserve law and order. The Act continued to be used against the nationalist community long after the violence of this period had come to an end.[50]

The two sides' positions became strictly defined following this period. From a unionist perspective, Northern Ireland's nationalists were inherently disloyal and determined to force Protestants and unionists into a united Ireland. In the 1970s, for instance, during the period when the British government was unsuccessfully attempting to implement the Sunningdale Agreement, then-Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) councillor Hugh Logue described the agreement as the means by which unionists "will be trundled into a united Ireland".[51] This threat was seen as justifying preferential treatment of unionists in housing, employment and other fields. The prevalence of large families and a more rapid population growth among Catholics was also seen as a threat.

From a nationalist perspective, continued discrimination against Catholics only proved that Northern Ireland was an inherently corrupt, British-imposed state. The Republic of Ireland Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Charles Haughey, whose family had fled County Londonderry during the 1920s Troubles, described Northern Ireland as "a failed political entity". The Unionist government ignored Edward Carson's warning in 1921 that alienating Catholics would make Northern Ireland inherently unstable.

After the early 1920s, there were occasional incidents of sectarian unrest in Northern Ireland. These included the brief Northern campaign in the 1940s, and Border campaign between 1956 and 1962. By the early 1960s Northern Ireland was fairly stable.

Late 1960s

There is little agreement on the exact date of the start of the Troubles. Different writers have suggested different dates. These include the formation of the UVF in 1966,[52] the civil rights march in Derry on 5 October 1968, the beginning of the 'Battle of the Bogside' on 12 August 1969 or the deployment of British troops on 14 August 1969.

Civil rights campaign and loyalist backlash

In 1964, a peaceful civil rights campaign began in Northern Ireland. The civil rights movement sought to end discrimination against Catholics (including those of Catholic background) and Irish nationalists by the Protestant- and unionist-dominated government of Northern Ireland. It called for:

- an end to job discrimination – it showed evidence that Catholics/nationalists were less likely to be given certain jobs, especially government jobs

- public housing to be allocated on the basis of need rather than religion or political views – it showed evidence that unionist-controlled local councils allocated housing to Protestants ahead of Catholics/nationalists

- one man, one vote – in NI, only householders could vote in local elections, while in the rest of the UK all adults could vote

- an end to gerrymandering of electoral boundaries – this meant that nationalists had less voting power than unionists, even where nationalists were a majority

- reform of the police force (Royal Ulster Constabulary or RUC) – it was almost 100% Protestant and accused of sectarianism and police brutality

- repeal of the Special Powers Act – this allowed police to search without a warrant, arrest and imprison people without charge or trial, ban any assemblies or parades, and ban any publications; the Act was used almost exclusively against nationalists and republicans[53][54][55][56][57]

In March and April 1966, Irish republicans held parades throughout Ireland to mark the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising. On 8 March, a group of former IRA members blew up Nelson's Pillar in Dublin. At the time, the IRA was weak and not engaged in armed action, but some unionists/loyalists warned that it was about to be revived and launch another campaign against Northern Ireland.[54][58] In April, loyalists led by Ian Paisley, a Protestant fundamentalist preacher, founded the Ulster Constitution Defence Committee (UCDC). It set up a paramilitary-style wing called the Ulster Protestant Volunteers (UPV).[54] The 'Paisleyites' set out to stymie the civil rights movement and oust Terence O'Neill, Prime Minister of Northern Ireland. Although O'Neill was a unionist, they saw him as being too 'soft' on the civil rights movement and opposed his policies of reform and reconciliation.[59]

At the same time, a loyalist group calling itself the "Ulster Volunteer Force" (UVF) emerged in the Shankill area of Belfast. It was led by Gusty Spence, a former British soldier. Many of its members were also members of the UCDC and UPV.[60] In April and May it petrol bombed a number of Catholic homes, schools and businesses. One of the fires killed an elderly Protestant widow.[54] On 21 May, the UVF issued a statement declaring "war" against the IRA and anyone helping it.[61] On 27 May the UVF fatally shot a Catholic civilian, John Scullion, as he walked home.[54] A month later it shot three Catholic civilians as they left a pub, killing one.[54][61] Shortly after, the UVF was made illegal by the NI Government.[54]

The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) was formed in January 1967.[62][63] On 20 June 1968, civil rights activists (including Austin Currie, an Irish nationalist MP) protested against housing discrimination by squatting in a house in Caledon. The local council had allocated the house to an unmarried 19-year-old Protestant girl (the secretary of a local Unionist politician) instead of two Catholic families with children.[64] RUC officers – one of whom was the girl's brother – forcibly removed the activists.[64] Two days before the protest, the two Catholic families who had been squatting in the house next door were removed by police.[65] Currie had brought their grievance to the local council and to Stormont, but had been told to leave. The incident invigorated the civil rights movement.[66]

On 24 August 1968, the civil rights movement held its first civil rights march, from Coalisland to Dungannon. Many more marches would be held over the following year. Loyalists (especially members of the UPV) attacked some of the marches and held counter-demonstrations in a bid to get the marches banned.[64] Nationalists saw the RUC, almost wholly Protestant, as backing the loyalists and allowing the attacks to occur.[67] On 5 October 1968, a civil rights march in Derry was banned by the NI Government.[68] When civil rights activists defied the ban, RUC officers surrounded the marchers and beat them indiscriminately and without provocation.[68] Over 100 people were injured, including a number of MPs.[68] The incident was filmed by television news crews and shown around the world.[69] It caused outrage among Catholics and nationalists, sparking two days of rioting in Derry between nationalists and the RUC.[68]

A few days later, a student civil rights group – People's Democracy – was formed in Belfast.[64] In late November, O'Neill promised the civil rights movement some concessions, but they were seen as inadequate. On 1 January 1969, People's Democracy began a four-day march from Belfast to Derry, which was repeatedly harassed and attacked by loyalists. At Burntollet it was attacked by about 200 loyalists and off-duty police officers armed with iron bars, bricks and bottles in a pre-planned ambush. When the march reached Derry it was again attacked. The marchers claimed that police did nothing to protect them and that some officers helped the attackers.[70] That night, RUC officers went on a rampage in the Bogside area of Derry, attacking Catholic homes, attacking and threatening residents, and hurling sectarian abuse.[70] Residents then sealed off the Bogside with barricades to keep the police out, creating "Free Derry".

In March and April 1969, loyalists bombed water and electricity installations in Northern Ireland, blaming them on the dormant IRA and elements of the civil rights movement. Some attacks left much of Belfast without power and water. The loyalists hoped the bombings would force Terence O'Neill to resign and bring an end to reforms.[71][72] There were six bombings between 30 March and 26 April.[71][73] All were widely blamed on the IRA, and British soldiers were sent to guard installations.[71] Unionist support for O'Neill waned, and on 28 April he resigned as Prime Minister.[71]

August 1969 riots and aftermath

On 19 April there were clashes between NICRA marchers, the RUC and loyalists in the Bogside. RUC officers entered the house of Samuel Devenny (42), an uninvolved Catholic civilian, and ferociously beat him along with two of his teenage daughters and a family friend.[71] One of the daughters was beaten unconscious as she lay recovering from surgery.[74] Devenny suffered a heart attack and died on 17 July from his injuries. On 13 July, RUC officers beat another uninvolved Catholic bystander, Francis McCloskey (67), during clashes in Dungiven. He died of his injuries the next day.[71]

On 12 August, the loyalist Apprentice Boys were allowed to march along the edge of the Bogside. Taunts and missiles were exchanged between the loyalists and nationalist residents. After being bombarded with stones and petrol bombs from nationalists, the RUC, backed by loyalists, tried to storm the Bogside. The RUC used CS gas, armoured vehicles and water cannons, but were kept at bay by hundreds of nationalists.[75] The continuous fighting, which became known as the Battle of the Bogside, would last for two days.

In response to events in Derry, nationalists held protests at RUC bases in Belfast and elsewhere. Some of these led to clashes with the RUC and attacks on RUC bases. In Belfast, loyalists responded by invading nationalist districts, burning houses and businesses. There were gun battles between nationalists and the RUC, and between nationalists and loyalists. A group of about 30 IRA members was involved in the fighting in Belfast. The RUC deployed Shorland armoured cars mounted with heavy Browning machine guns. The Shorlands twice opened fire on a block of flats in a nationalist district, killing a nine-year-old boy. RUC officers opened fire on rioters in Armagh, Dungannon and Coalisland.

During the riots, on 13 August, Taoiseach Jack Lynch made a television address. He condemned the RUC and said that the Irish Government "can no longer stand by and see innocent people injured and perhaps worse". He called for a United Nations peacekeeping force to be deployed and said that Irish Army field hospitals were being set up at the border in County Donegal near Derry. Lynch added that Irish re-unification would be the only permanent solution. Some interpreted the speech as a threat of military intervention.[76] After the riots, Lynch ordered the Irish Army to plan for a possible humanitarian intervention in Northern Ireland. The plan, Exercise Armageddon, was rejected and remained classified for over thirty years.

On 14–15 August, British troops were deployed in Derry and Belfast to restore order,[77] but did not try to enter the Bogside. This brought the riots to an end. Eight people had been shot dead, more than 750 had been injured (including 133 who suffered gunshot wounds) and more than 400 homes and businesses had been destroyed (83% of them owned by Catholics). More than 1,800 families were forced to flee their homes, including 1,505 Catholic families and 315 Protestant families. The Irish Army set up refugee camps in the Republic. Nationalists initially welcomed the British Army, as they did not trust the RUC. However, relations soured due to the Army's heavy-handedness.[78]

After the riots, the 'Hunt Committee' was set up to examine the RUC. It published its report on 12 October, recommending that the RUC become an unarmed force and the B Specials be disbanded. That night, loyalists took to the streets of Belfast in protest at the report. During violence in the Shankill, UVF members shot dead RUC officer Victor Arbuckle. He was the first RUC officer to be killed during the Troubles.[79] In October and December 1969, the UVF carried out a number of bombings in the Republic of Ireland.

1970s

Violence peaks and Stormont collapses

The period from 1970 through 1972 saw an explosion of political violence in Northern Ireland, peaking in 1972, when nearly 500 people, just over half of them civilians, lost their lives. The year 1972 saw the greatest loss of life throughout the entire conflict.[80]

In Derry by the end of 1971, 29 barricades were in place to block access to what was known as Free Derry; 16 of them impassable even to the British Army's one-ton armoured vehicles.[81] Many of the nationalist/republican "no-go areas" were controlled by one of the two factions of the Irish Republican Army—the Provisional IRA and Official IRA.

There are several reasons why violence escalated in these years.

Unionists claim the main reason was the formation of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (Provisional IRA), and the Official Irish Republican Army (Official IRA), two groups formed when the IRA split into the 'Provisional' and 'Official' factions. While the older IRA had embraced non-violent civil agitation,[82] the new Provisional IRA was determined to wage "armed struggle" against British rule in Northern Ireland. The new IRA was willing to take on the role of "defenders of the Catholic community",[83] rather than seeking working-class unity across both communities which had become the aim of the "Officials".

Nationalists pointed to a number of events in these years to explain the upsurge in violence. One such incident was the Falls Curfew in July 1970, when 3,000 troops imposed a curfew on the nationalist Lower Falls area of Belfast, firing more than 1,500 rounds of ammunition in gun battles with the Official IRA and killing four people. Another was the 1971 introduction of internment without trial (out of over 350 initial detainees, none was a Protestant).[84] Moreover, due to poor intelligence,[85] very few of those interned were actually republican activists, but some went on to become republicans as a result of their experience.[citation needed] This resulted in numerous gun battles between the British army and the Provisional IRA and the Official IRA. Between 1971 and 1975, 1,981 people were detained; 1,874 were Catholic/republican, while 107 were Protestant/loyalist.[86] There were widespread allegations of abuse and even torture of detainees,[87][88] and the "five techniques" used by the police and army for interrogation were ruled to be illegal following a British government inquiry.[89] Nationalists also point to the fatal shootings of 14 unarmed nationalist civil rights demonstrators by the British Army in Derry on 30 January 1972, on what became known as Bloody Sunday.

The Provisional IRA (or "Provos", as they became known), which emerged from a split in the Irish Republican Army in December 1969, soon established itself as defenders of the nationalist community.[90][91] Despite the increasingly reformist and Marxist politics of the Official IRA, it began its own armed campaign in reaction to the ongoing violence. The Provisional IRA's offensive campaign began in early 1971 when the Army Council sanctioned attacks on the British Army.[92]

In 1972 the Provisional IRA killed approximately 100 soldiers, wounded 500 more and carried out approximately 1,300 bombings,[93] mostly against commercial targets which they considered "the artificial economy".[94][95] While the Official IRA killed dozens of soldiers and wounded several more in just 1972 mostly through gun attacks according to the CAIN project's Sutton database. The bombing campaign killed many civilians, notably on Bloody Friday on 21 July, when 22 bombs were set off in the centre of Belfast killing seven civilians and two soldiers. The Official IRA, which had never been fully committed to armed action, called off its campaign in May 1972.[96] Despite a temporary ceasefire in 1972 and talks with British officials, the Provisionals were determined to continue their campaign until the achievement of a united Ireland.

The loyalist paramilitaries, including the Ulster Volunteer Force and the newly founded Ulster Defence Association, responded to the increasing violence with a campaign of sectarian assassination of nationalists, identified simply as Catholics.[citation needed] Some of these killings were particularly gruesome. The Shankill Butchers beat and tortured their victims before killing them. Another feature of the political violence was the involuntary or forced displacement of both Catholics and Protestants from formerly mixed residential areas. For example, in Belfast, Protestants were forced out of Lenadoon, and Catholics were driven out of the Rathcoole estate and the Westvale neighbourhood. In Derry city, almost all the Protestants fled to the predominantly loyalist Fountain Estate and Waterside areas.[citation needed]

The UK government in London, believing the Northern Ireland administration incapable of containing the security situation, sought to take over the control of law and order there. As this was unacceptable to the Northern Ireland Government, the British government pushed through emergency legislation (the Northern Ireland (Temporary Provisions) Act 1972) which suspended the unionist-controlled Stormont parliament and government, and introduced "direct rule" from London. Direct rule was initially intended as a short-term measure; the medium-term strategy was to restore self-government to Northern Ireland on a basis that was acceptable to both unionists and nationalists. Agreement proved elusive, however, and the Troubles continued throughout the 1970s, 1980s, and the 1990s within a context of political deadlock.

The existence of "no-go areas" in Belfast and Derry was a challenge to the authority of the British government in Northern Ireland, and the British army finally demolished the barricades and re-established control over the areas in Operation Motorman on 31 July 1972.

Sunningdale Agreement and UWC strike

In June 1973, following the publication of a British White Paper and a referendum in March on the status of Northern Ireland, a new parliamentary body, the Northern Ireland Assembly, was established. Elections to this were held on 28 June. In October of that year, mainstream nationalist and unionist parties, along with the British and (Southern) Irish governments, negotiated the Sunningdale Agreement, which was intended to produce a political settlement within Northern Ireland, but with a so-called "Irish dimension" involving the Republic of Ireland. The agreement provided for "power-sharing" between nationalists and unionists and a "Council of Ireland" designed to encourage cross-border co-operation. The similarities between the Sunningdale Agreement and the Belfast Agreement of 1998 has led some commentators to characterise the latter as "Sunningdale for slow learners".[97] This assertion has been criticised by political scientists one of whom stated that "..there are... significant differences between them [Sunningdale and Belfast], both in terms of content and the circumstances surrounding their negotiation, implementation, and operation".[98]

Unionism, however, was split over Sunningdale, which was also opposed by the IRA, whose goal remained nothing short of an end to Northern Ireland's existence as part of the United Kingdom. Many unionists opposed the concept of power-sharing, arguing that it was not feasible to share power with those (nationalists) who sought the destruction of the state. Perhaps more significant, however, was the unionist opposition to the "Irish dimension" and the Council of Ireland, which was perceived as being an all-Ireland parliament-in-waiting. The remarks by SDLP councillor Hugh Logue to an audience at Trinity College Dublin that Sunningdale was the tool "by which the Unionists will be trundled off to a united Ireland" also damaged unionist support for the agreement.

In January 1974, Brian Faulkner was narrowly deposed as Unionist Party leader and replaced by Harry West. A UK general election in February 1974 gave the anti-Sunningdale unionists the opportunity to test unionist opinion with the slogan "Dublin is only a Sunningdale away", and the result galvanised their opposition: they won 11 of the 12 seats, winning 58% of the vote with most of the rest going to nationalists and pro-Sunningdale unionists.

Ultimately, however, the Sunningdale Agreement was brought down by mass action on the part of loyalists (primarily the Ulster Defence Association, at that time over 20,000 strong[citation needed] ) and Protestant workers, who formed the Ulster Workers' Council. They organised a general strike: the Ulster Workers' Council strike. This severely curtailed business in Northern Ireland and cut off essential services such as water and electricity. Nationalists argue that the British Government did not do enough to break this strike and uphold the Sunningdale initiative. There is evidence that the strike was further encouraged by MI5, a part of their campaign to 'disorientate' British prime minister Harold Wilson's government.[99] In the event, faced with such determined opposition, the pro-Sunningdale unionists resigned from the power-sharing government and the new regime collapsed.

Three days into the UWC strike, on 17 May 1974, two UVF teams from the Belfast and Mid-Ulster brigades[100] detonated three no-warning car bombs in Dublin's city centre during the Friday evening rush hour, resulting in 26 deaths and close to 300 injuries. Ninety minutes later, a fourth car bomb exploded in Monaghan, killing another seven people. Nobody has ever been convicted of these attacks.

Wilson had secretly met with the IRA in 1971 while leader of the opposition; his government in late 1974 and early 1975 again met with the IRA to negotiate a ceasefire. The failure of Sunningdale led on to the serious consideration in London until November 1975 of the option of a rapid British withdrawal by the Wilson government; Northern Ireland would have become a separate Dominion of the British Commonwealth. The possibilities of orderly British withdrawal, repartition of the island, and/or a collapse of Northern Ireland into civil war and anarchy were also considered in Dublin by Garret FitzGerald in a memorandum of June 1975, on which he commented in 2006. The memorandum concluded that the Irish government could do little. With its small army of 12,500 men, which the government believed it could not enlarge without negative consequences, a civil war in Northern Ireland would cause many deaths there and severe consequences for the rest of the island; FitzGerald warned James Callaghan that these included a "threat [to] democratic government in the Republic", which in turn jeopardized British and European security against Communist and other foreign nations.[101]

Mid-1970s

Merlyn Rees, the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland had lifted the proscription against the UVF in April 1974. In December, one month after the Birmingham pub bombings which killed 21 people, the IRA declared a ceasefire; this would theoretically last throughout most of the following year. The ceasefire notwithstanding, sectarian killings actually escalated in 1975, along with internal feuding between rival paramilitary groups. This made 1975 one of the "bloodiest years of the conflict".[102] On 31 July 1975 at Buskhill, outside Newry, the popular Irish cabaret band "The Miami Showband" was returning home to Dublin after a gig in Banbridge when it was ambushed by gunmen from the UVF Mid-Ulster Brigade wearing British Army uniforms at a bogus military roadside checkpoint on the main A1 road. Three of the bandmembers were shot dead and two of the UVF men were killed when the bomb they had loaded onto the band's minibus went off prematurely. The following January, ten Protestant workers were gunned down in Kingsmill, south County Armagh after having been ordered off their bus by an armed Republican gang who called itself the South Armagh Republican Action Force. These killings were in retaliation to a loyalist double shooting attack against the Reavey and O'Dowd families the previous night.

The violence continued through the rest of the 1970s. The British Government reinstated the ban against the UVF in October 1975, making it once more an illegal organisation. When the Provisional IRA's December 1974 ceasefire had ended in early 1976 and it had returned to violence, it had lost the hope that it had felt in the early 1970s that it could force a rapid British withdrawal from Northern Ireland, and instead developed a strategy known as the "Long War", which involved a less intense but more sustained campaign of violence that could continue indefinitely. The Official IRA ceasefire of 1972, however, became permanent, and the "Official" movement eventually evolved into the Workers' Party, which rejected violence completely. However, a splinter from the "Officials"—the Irish National Liberation Army—continued with a campaign of violence in 1974.

Late 1970s

By the late 1970s, war-weariness was visible in both communities. One manifestation of this was the formation of group known as "Peace People", which won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1976. The Peace People organised large demonstrations calling for an end to paramilitary violence. Their campaign lost momentum, however, after they appealed to the nationalist community to provide information on the IRA to security forces, the Peace People being perceived as being more critical of paramilitaries than the security forces.[103] The decade ended with a double attack by the IRA against the British. On 27 August 1979, Lord Mountbatten of Burma, while on holiday in Mullaghmore, County Sligo, was killed by a bomb planted on board his boat. Three other people were also killed, including a local teenage boatman. That same afternoon, eighteen British soldiers, mostly members of the Parachute Regiment, were killed by two remote-controlled bombs at Warrenpoint, County Down.[104]

Successive British Governments, having failed to achieve a political settlement, tried to "normalise" Northern Ireland. Aspects included the removal of internment without trial and the removal of political status for paramilitary prisoners. From 1972 onwards, paramilitaries were tried in juryless Diplock courts to avoid intimidation of jurors. On conviction, they were to be treated as ordinary criminals. Resistance to this policy among republican prisoners led to over 500 of them in the Maze prison initiating the blanket protest and the dirty protest. Their protests would culminate in hunger strikes in 1980 and 1981, aimed at the restoration of political status.

1980s

In the 1981 Irish Hunger Strike, ten republican prisoners (seven from the Provisional IRA and three from the INLA) starved themselves to death. The first hunger striker to die, Bobby Sands, was elected to Parliament on an Anti-H-Block ticket, as was his election agent Owen Carron following Sands' death. The hunger strikes proved emotional events for the nationalist community—over 100,000 people[105] attended Sands' funeral mass in West Belfast and thousands attended those of the other hunger strikers. From an Irish republican perspective, the significance of these events was to demonstrate a potential for political and electoral strategy.[106] In the wake of the hunger strikes, Sinn Féin, seen by some as the Provisional IRA's political wing, began to contest elections for the first time in both Northern Ireland and the Republic. In 1986, Sinn Féin recognised the legitimacy of the Republic's Dáil, which caused a small group of republicans to break away and form Republican Sinn Féin.

The IRA's "Long War" was boosted by large donations of arms to them from Libya in the 1980s (see Provisional IRA arms importation) due to Muammar Gaddafi's anger at Thatcher's government for assisting the Reagan government's bombing of Tripoli, which had allegedly killed one of Gaddafi's children.

The INLA was highly active in the early and mid-1980s. In 1982, it bombed a disco frequented by off-duty British soldiers, killing 11 soldiers and six civilians. One of the IRA's most high profile actions in this period was the Brighton hotel bombing on 12 October 1984, when it set off a 100-pound bomb in the Grand Brighton Hotel in Brighton, where politicians including Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher were staying for the Conservative Party conference. Five people were killed, including Conservative MP Sir Anthony Berry and the wife of Government Chief Whip John Wakeham, and thirty-four others were injured, including Wakeham, Trade and Industry Secretary Norman Tebbit and Tebbit's wife, Margaret.[107]

On 28 February 1985 in Newry, 9 RUC officers were killed after a mortar attack on the police station in Corry Square. The attack was planned by the IRA South Armagh Brigade and an IRA unit in Newry. Nine shells were fired from a Mark 10 mortar which was bolted onto the back of a hijacked Ford van in Crossmaglen. Eight shells overshot the station, but the ninth hit a Portakabin which was being used as a canteen.

On 8 November 1987, in Enniskillen, County Fermanagh, a Provisional IRA time bomb exploded during a parade on Remembrance Day to commemorate victims of World War One. The bomb went off by a cenotaph which was at the heart of the parade. It was one of the IRA's biggest failures, as it was not aimed at killing anybody. Eleven people (ten civilians and a police officer, along with a pregnant woman) were killed and 63 were injured. The IRA said it had made a mistake and that its target had been the British soldiers parading to the memorial. The unit who carried out the bombing was disbanded. Loyalist paramilitaries responded to the bombing with revenge attacks on catholic civilians in the Enniskillen area and the rest of the north.

Three IRA members were shot dead at a Shell petrol station on Winston Churchill Avenue in Gibraltar in 1988. This became known as Operation Flavius. Their funeral at Milltown Cemetery in Belfast was attacked by Michael Stone, a UDA member who threw grenades and fired shots as the coffin was lowered. The attack killed 3 people. It became known as the Milltown Massacre. Provisional IRA members launched a revenge attack on British Soldiers 3 days after Milltown Cemetery. This attack became known as the Corporals killings. It occurred when 2 plain-clothed British soldiers, David Howes and Derek Wood, were shot dead in Andersonstown in Belfast. It has been described as the most dramatic incident in the Troubles.

In the mid to late 1980s loyalist paramilitaries, including the Ulster Volunteer Force, the Ulster Defence Association and Ulster Resistance, imported arms and explosives from South Africa.[108] The weapons obtained were divided between the UDA, the UVF and Ulster Resistance, and led to an escalation in the assassination of Catholics, although some of the weaponry (such as rocket-propelled grenades) were hardly used. [citation needed] These killings were in response to the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement which gave the Irish government a "consultative role" in the internal government of Northern Ireland.

In 1987, the Irish People's Liberation Organisation, a breakaway faction of the INLA, engaged in a bloody feud against the INLA which heavily weakened the INLAs presence in areas but didn't end the INLA. By 1992, the IPLO was destroyed by the Provisionals for involvement in drug dealing thus ending the feud.

1990s

Since the late 1980s, while the IRA continued its armed campaign, its political wing Sinn Féin, led since 1983 by Gerry Adams, sought a negotiated end to the conflict, although Adams knew that this would be a very long process. In a statement, attributed to a 1970 interview with German filmmaker Teod Richter, he himself predicted that the war would last another 20 years. He conducted open talks with John Hume—the Social Democratic and Labour Party leader—and secret talks with Government officials. Loyalists were also engaged in behind-the-scenes talks to end the violence, connecting with the British and Irish governments through Protestant clergy, in particular the Presbyterian Rev Roy Magee and the Anglican Archbishop Robin Eames. A French TV crew filmed the IRA at a training camp in Donegal. A representative for the General Headquarters Staff of the IRA was interviewed. He said that the IRA would "Eventually sap the political will of the British government to remain in Ireland".

Situation worsens in South Armagh

The IRA's South Armagh Brigade had made the countryside village of Crossmaglen their stronghold since the 1970s. Silverbridge, Cullyhanna, Cullaville, Forkhill, Jonesborough and Creggan were also the IRA's South Armagh strongholds. In 1978, they shot down a British Army Lynx helicopter near the village of Silverbridge, killing a British army lieutenant colonel.[109] In the 1990s the IRA came up with a new plan to stop British Army foot patrols near Crossmaglen. They developed two sniper teams to hit back on British army patrols and RUC officers.[110] They usually fired from an improvised armoured car using a .50 BMG caliber or M82 sniper rifle. Signs were put up around South Armagh reading "Sniper at Work". The snipers killed the last British soldier to be killed before the Good Friday agreement, bombardier Steven Restorick. Furthermore, the IRA developed skills to attack helicopters in South Armagh and elsewhere since the 1980s,[111] including the shootdown of a Gazelle flying over the border between Tyrone and Monaghan.[112] Another notable incident involving British helicopters in South Armagh was the Battle of Newry Road in September 1993.[113] Two other helicopters, a British army Lynx and an RAF Puma were shot down by improvised mortar fire in 1994. The IRA also used to set up checkpoints in South Armagh during this period, unchallenged by the security forces.[111][114]

First ceasefire

After a prolonged period of political manoeuvring in the background, the loyalist and republican paramilitaries declared ceasefires in 1994.

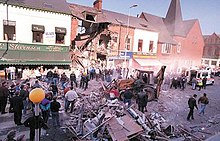

The year leading up to the ceasefires was a particularly tense one, marked by atrocities. Under the leadership of Johnny Adair the UDA and UVF stepped up their killings of Catholics (for the first time in 1993 killing more people than the republicans). The IRA responded with the Shankill Road bombing in October 1993, which aimed to kill the UDA leadership, but in fact killed eight Protestant civilians and a low-ranking UDA member. The UDA in turn retaliated with the Greysteel massacre and shootings at Castlerock, County Derry.

On 16 June 1994, just before the ceasefires, the Irish National Liberation Army killed a UVF member in a gun attack on the Shankill Road. In revenge, three days later, the UVF killed six civilians in a shooting at a pub in Loughinisland, County Down. The IRA, in the remaining month before its ceasefire, killed four senior loyalists, three from the UDA and one from the UVF. There are various interpretations of the spike in violence before the ceasefires. One theory is that the loyalists feared the peace process represented an imminent "sellout" of the Union and ratcheted up their violence accordingly. Another explanation is that the republicans were "settling old scores" before the end of their campaigns. They wanted to enter the political process from a position of military strength rather than weakness.

On 31 August 1994, the Provisional IRA declared a ceasefire. The loyalist paramilitaries, temporarily united in the "Combined Loyalist Military Command", reciprocated six weeks later. Although these ceasefires failed in the short run, they marked an effective end to large-scale political violence in the Troubles, as they paved the way for the final ceasefire.

In 1995 the United States appointed George Mitchell as the United States Special Envoy for Northern Ireland. Mitchell was recognised as being more than a token envoy and someone representing a President (Bill Clinton) with a deep interest in events.[115] The British and Irish governments agreed that Mitchell would chair an international commission on disarmament of paramilitary groups.[116]

Second ceasefire

On 9 February 1996, less than two years after the declaration of the ceasefire, the IRA revoked it with the Docklands bombing in the Canary Wharf area of London, killing two people and causing £85 million in damage to the city's financial centre. Sinn Féin blamed the failure of the ceasefire on the British Government's refusal to begin all-party negotiations until the IRA decommissioned its weapons.[117]

The attack was followed by several more, most notably the Manchester Bombing, which destroyed a large area of the centre of the city on 15 June 1996. It was the largest bomb attack in Britain since World War II. While the attack avoided any fatalities due to the rapid response of the emergency services to a telephone warning, over 200 people were injured in the attack, many of them outside the established cordon. The damage caused by the blast was valued at £411 million. The last British soldier to die in the Troubles, Lance Bombardier Stephen Restorick, was also killed during this period, on 12 February 1997, by the "South Armagh sniper".

The IRA reinstated their ceasefire in July 1997, as negotiations for the document that would become known as the Good Friday Agreement were starting without Sinn Féin. In September of the same year Sinn Féin signed the Mitchell Principles and was invited into the talks.

The UVF was the first paramilitary grouping to split as a result of their ceasefire, spawning the Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF) in 1996. In December 1997, the INLA assassinated LVF leader Billy Wright, leading to a series of revenge killings of Catholics by loyalist groups. In addition, a group of Republicans split from the Provisional IRA and formed the Real IRA.

In August 1998, a Real IRA bomb in Omagh killed 29 civilians. This bombing largely discredited "dissident" Republicans and their campaigns in the eyes of most nationalists. They became small groups with little influence, but still capable of violence.[118] The INLA also declared a ceasefire after the Belfast Agreement of 1998.

Since then, most paramilitary violence has been directed inwards, at their "own" communities and at other factions within their organisations. The UDA, for example, has feuded with their fellow loyalists the UVF on two occasions since 2000. There have also been internal struggles for power between "Brigade commanders" and involvement in organised crime.[119]

Provisional IRA members have also been accused of killing men, such as Robert McCartney, Matthew Ignatius Burns and Andrew Kearney.

Political process

After the ceasefires, talks began between the main political parties in Northern Ireland to establish political agreement. These talks led to the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. This Agreement restored self-government to Northern Ireland on the basis of "power-sharing". In 1999, an executive was formed consisting of the four main parties, including Sinn Féin. Other important changes included the reform of the RUC, renamed as the Police Service of Northern Ireland, which was required to recruit at least a minimum quota of Catholics, and the abolition of Diplock courts under the Justice and Security (Northern Ireland) Act 2007.[120] A security normalisation process also began as part of the treaty, which comprised the progressive closing of redundant Army barracks, border observation towers, and the withdrawal of all forces taking part in Operation Banner – including the resident battalions of the Royal Irish Regiment – that would be replaced by an infantry brigade, deployed in ten sites around Northern Ireland but with no operative role in the province itself.[121]

The power-sharing Executive and Assembly were suspended in 2002, when unionists withdrew following the exposure of a Provisional IRA spy ring within the Sinn Féin office. There were ongoing tensions about the Provisional IRA's failure to disarm fully and sufficiently quickly. IRA decommissioning has since been completed (in September 2005) to the satisfaction of most.[122]

A feature of Northern Irish politics since the Agreement has been the eclipse in electoral terms of parties such as the Social Democratic and Labour Party and Ulster Unionist Party, by rival parties such as Sinn Féin and the DUP. Similarly, although political violence is greatly reduced, sectarian animosity has not disappeared. Residential areas are more segregated between Catholic nationalists and Protestant unionists than ever.[123]

Because of this, progress towards restoring the power-sharing institutions was slow and tortuous. On 8 May 2007, devolved government returned to Northern Ireland. DUP leader Ian Paisley and Sinn Féin's Martin McGuinness took office as First Minister and deputy First Minister, respectively.

Collusion between security forces and loyalists

In their efforts to defeat the IRA, there were incidents of collusion between the state security forces (the British Army and RUC) and loyalist paramilitaries. This included soldiers and policemen taking part in loyalist attacks while off-duty, giving weapons and intelligence to loyalists, not taking action against them, and hindering police investigations. Some of the soldiers and policemen involved were members of loyalist paramilitaries while others were not. The security forces also had double agents and informers within loyalist groups who organized attacks on the orders of, or with the knowledge of, their handlers. The De Silva report found that, during the 1980s, 85% of the intelligence loyalists used to target people came from the security forces.[124]

Due to a number of factors the British Army's locally-recruited Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) was almost wholly Protestant.[125][126] Despite the vetting process, some loyalist militants managed to enlist; mainly to obtain weapons, training and intelligence.[127] By 1990, at least 197 UDR soldiers had been convicted of loyalist terrorist offences and other serious crimes, including 19 who were convicted of murder.[128] This was only a small fraction of those who served in it, but the proportion was higher than the regular British Army, the RUC and the civilian population.[129] For more information, see Loyalist infiltration of the UDR.

During the 1970s, the Glenanne gang—a secret alliance of loyalist militants, British soldiers and RUC officers—carried out a string of gun and bomb attacks against Catholics/nationalists in an area of Northern Ireland known as the "murder triangle".[130][131] It also carried out some attacks in the Republic. Lethal Allies: British Collusion in Ireland claims the group killed about 120 people, almost all uninvolved civilians.[132] The Cassel Report investigated 76 murders attributed to the group and found evidence that soldiers and policemen were involved in 74 of those.[133] One member, RUC officer John Weir, claimed his superiors knew of the collusion but allowed it to continue.[134] The Cassel Report also said some senior officers knew of the crimes but did nothing to prevent, investigate or punish.[133] Attacks attributed to the group include the Dublin and Monaghan bombings (1974), the Miami Showband killings (1975) and the Reavey and O'Dowd killings (1976).[131][135]

The Stevens Inquiries concluded that the conflict had been intensified and prolonged by a core of army and police officers who helped loyalists to kill people, including civilians.[136][137] Members of the security forces tried to obstruct the Stevens investigation.[137][138] It revealed the existence of the Force Research Unit (FRU), a covert British Army intelligence unit that used double agents to infiltrate paramilitary groups.[139] Brian Nelson, the UDA's chief 'intelligence officer', was a FRU agent.[140] In 1988, weapons were shipped to loyalists from South Africa under Nelson's supervision.[140] Through Nelson, FRU helped the UDA target people for assassination. FRU commanders say their plan was to make the UDA "more professional" by helping it to target republican activists and prevent it killing Catholic civilians.[139] The Stevens Inquiries found evidence only two lives were saved and that Nelson/FRU was responsible for at least 30 murders and many other attacks – many of the victims uninvolved civilians.[136] One of the most prominent victims was solicitor Pat Finucane. Although Nelson was imprisoned in 1992, FRU's intelligence continued to help the UDA and other loyalist groups.[141][142] From 1992 to 1994, loyalists were responsible for more deaths than republicans.[143]

A 2007 Police Ombudsman report revealed that UVF members had committed a string of terrorist crimes, including murder, while working as informers for RUC Special Branch. It found that Special Branch knew of this but had given informers immunity; ensuring they weren't caught, helping them during police interviews, and blocking weapons searches.[144] UVF member Robin 'the Jackal' Jackson has been linked to between 50[145][146] and 100[131] killings in Northern Ireland, although he was never convicted of any and never served any lengthy prison terms. It has been alleged by many people, including members of the security forces, that Jackson was an RUC agent.[147] According to the Irish Government's Barron Report, he was "reliably said to have had relationships with British Intelligence".[148]

Other incidents of alleged collusion between loyalists and the security forces include the McGurk's Bar bombing, the 1972 and 1973 Dublin bombings, the Milltown Cemetery attack, the Cappagh killings, the Sean Graham bookmakers' shooting, the Loughinisland massacre, and the murders of Robert Hamill, Rosemary Nelson, and Eddie Fullerton.

The Disappeared

During the 1970-1980s the IRA and loyalist paramiltiares abducted many individuals who were suspected of being informers. Amongst the known victims, called "The Disappeared", 9 out of 15 bodies have been found up to this day. For more detail: "Who were the 'Disappeared'?"

British government security forces also carried out extrajudicial killings of unarmed civilians.[149] Groups such as the Military Reaction Force (MRF) have been characterized as death squads.[150][151] Their victims were often civilians unaffiliated with any paramilitaries, such as the 12 May 1972 Andersonstown shooting of seven unarmed Catholic civilians and the 15 April 1972 Whiterock Road shooting of two unarmed Catholic civilians by plains clothes British soldiers.[152] An MRF member stated in 1978 that the Army often attempted false flag sectarian attacks, thus provoking sectarian conflict and "taking the heat off the Army".[153] Another former member claimed "we were not there to act like an army unit, we were there to act like a terror group".[154]

Shoot-to-kill allegations

Republicans allege that the security forces operated a shoot-to-kill policy rather than arresting IRA suspects. The security forces denied this and point out that in incidents such as the killing of eight IRA men at Loughgall in 1987, the IRA members who were killed were heavily armed. Others argue that incidents such as the shooting of three unarmed IRA members in Gibraltar by the Special Air Service ten months later confirmed suspicions among republicans, and in the British and Irish media, of a tacit British shoot-to-kill policy of suspected IRA members.[155]

Parades issue

Inter-communal tensions rise and violence often breaks out during the "marching season" when the Protestant Orange Order parades take place across Northern Ireland. The parades are held to commemorate William of Orange's victory in the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, which secured the Protestant Ascendancy and British rule in Ireland. One particular flashpoint that has caused repeated strife is the Garvaghy Road area in Portadown, where an Orange parade from Drumcree Church passes through a mainly nationalist estate off the Garvaghy Road. This parade has now been banned indefinitely, following nationalist riots against the parade, and also loyalist counter-riots against its banning. In 1995, 1996 and 1997, there were several weeks of prolonged rioting throughout Northern Ireland over the impasse at Drumcree. A number of people died in this violence, including a Catholic taxi driver, killed by the Loyalist Volunteer Force, and three (of four) nominally Catholic brothers (from a mixed-religion family) died when their house in Ballymoney was petrol-bombed.[156][157][158]

Disputes have also occurred in Belfast over parade routes along the Ormeau and Crumlin Roads. Orangemen hold that to march their "traditional route" is their civil right. Nationalists argue that, by parading through predominantly Catholic areas, the Orange Order is being unnecessarily provocative. Symbolically, the ability to either parade or to block a parade is viewed as expressing ownership of "territory" and influence over the government of Northern Ireland.

Social repercussions

The Troubles' impact on the ordinary people of Northern Ireland produced such psychological trauma that the city of Belfast had been compared to London during the Blitz.[159] The stress resulting from bomb attacks, street disturbances, security checkpoints, and the constant military presence had the strongest effect on children and young adults.[160] There was also the fear that local paramilitaries instilled in their respective communities with the punishment beatings, "romperings", and the occasional tarring-and-feathering meted out to individuals for various infractions committed against the community.[161]

In addition to the violence and intimidation, there was chronic unemployment and a severe housing shortage. Whilst many people were rendered homeless as a result of intimidation or having their houses burnt, urban redevelopment was also a factor in the social upheaval people in Belfast faced, with numerous families being transferred to new, alien estates when older, established districts such as Sailortown and Pound Loney were demolished. According to social worker and author Sarah Nelson, this new social problem of homelessness and disorientation contributed to the breakdown of the normal fabric of society, allowing for paramilitaries to exert a strong influence in certain districts.[161] Vandalism was also a major problem. In the 1970s there were 10,000 vandalised empty houses in Belfast alone. Most of the vandals were aged between eight and thirteen.[162]

Activities for young people were limited, with pubs fortified and cinemas closed. Just to go shopping in the city centre required passing through security gates and being subjected to body searches. Social intercourse was also affected. Normal interaction and friendship with people from the opposite side of the religious/political divide was nearly impossible in the atmosphere of fear and distrust that the Troubles generated.

According to one historian of the conflict, the stress of the Troubles engendered a breakdown in the previously strict sexual morality of Northern Ireland, resulting in a "confused hedonism" in respect of personal life.[163] In Derry, illegitimate births and alcoholism increased for women and the divorce rate rose.[164] Teenage alcoholism was also a problem, partly as a result of the drinking clubs established in both loyalist and republican areas. In many cases, there was little parental supervision of children in some of the poorer districts.[165]

The Department of Health has looked at a report written in 2007 by Mike Tomlinson of Queen's University, which asserted that the legacy of the Troubles has played a substantial role in the current high rate of suicide in Northern Ireland.[166]