→Translation: wikilinks |

Muhsin97233 (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tags: Reverted Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Thābit ibn Qurra''' (full name: {{transliteration|ar|Abū al-Ḥasan ibn Zahrūn al-Ḥarrānī al-Ṣābiʾ}}, {{lang-ar|أبو الحسن ثابت بن قرة بن زهرون الحراني الصابئ}}, {{lang-la|Thebit/Thebith/Tebit}});<ref>For the Arabic name, see {{harvnb|Rashed|Morelon|1960–2007}}; for the {{tranliteration|ar|[[Nisba (onomastics)|nisba]] al-Ṣābiʾ applied as a family name, see {{harvnb|De Blois|1960–2007}}; for the Latin name, see {{harvnb|Latham|2003|p=403}}.</ref> 826 or 836 – February 19, 901,<ref>{{harvnb|Rashed|2009b|pp=23–24}}; {{harvnb|Holme|2010}}.</ref> was |

'''Thābit ibn Qurra''' (full name: {{transliteration|ar|Abū al-Ḥasan ibn Zahrūn al-Ḥarrānī al-Ṣābiʾ}}, {{lang-ar|أبو الحسن ثابت بن قرة بن زهرون الحراني الصابئ}}, {{lang-la|Thebit/Thebith/Tebit}});<ref>For the Arabic name, see {{harvnb|Rashed|Morelon|1960–2007}}; for the {{tranliteration|ar|[[Nisba (onomastics)|nisba]] al-Ṣābiʾ applied as a family name, see {{harvnb|De Blois|1960–2007}}; for the Latin name, see {{harvnb|Latham|2003|p=403}}.</ref> 826 or 836 – February 19, 901,<ref>{{harvnb|Rashed|2009b|pp=23–24}}; {{harvnb|Holme|2010}}.</ref> was an [[Arabs|Arab]][[mathematician]], [[physician]], [[astronomer]], and [[translator]] who lived in [[Baghdad]] in the second half of the ninth century during the time of the [[Abbasid Caliphate]]. |

||

Thābit ibn Qurrah made important discoveries in [[algebra]], [[geometry]], and [[astronomy]]. In astronomy, Thābit is considered one of the first reformers of the [[Ptolemaic system]], and in mechanics he was a founder of [[statics]].<ref>{{harvnb|Holme|2010}}.</ref> |

Thābit ibn Qurrah made important discoveries in [[algebra]], [[geometry]], and [[astronomy]]. In astronomy, Thābit is considered one of the first reformers of the [[Ptolemaic system]], and in mechanics he was a founder of [[statics]].<ref>{{harvnb|Holme|2010}}.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 14:38, 1 August 2022

Thābit ibn Qurra | |

|---|---|

| Born | 210-211 AH/220-221 AH / 826 or 836 AD |

| Died | Wednesday, 26 Safar, 288 AH / February 19, 901 AD |

| Academic background | |

| Influences | Banu Musa, Archimedes, Apollonius, Nicomachus, Euclid |

| Academic work | |

| Era | Islamic Golden Age |

| Main interests | Mathematics, Mechanics, Astronomy, Astrology, Translation, Number theory |

| Notable ideas |

|

| Influenced | Al-Khazini, Al-Isfizari, Na'im ibn Musa[1] |

Thābit ibn Qurra (full name: Abū al-Ḥasan ibn Zahrūn al-Ḥarrānī al-Ṣābiʾ, Arabic: أبو الحسن ثابت بن قرة بن زهرون الحراني الصابئ, Latin: Thebit/Thebith/Tebit);[2] 826 or 836 – February 19, 901,[3] was an Arabmathematician, physician, astronomer, and translator who lived in Baghdad in the second half of the ninth century during the time of the Abbasid Caliphate.

Thābit ibn Qurrah made important discoveries in algebra, geometry, and astronomy. In astronomy, Thābit is considered one of the first reformers of the Ptolemaic system, and in mechanics he was a founder of statics.[4]

Biography

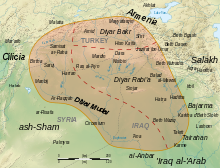

Thābit was born in Harran in Upper Mesopotamia, which at the time was part of the Diyar Mudar subdivision of the al-Jazira region of the Abbasid Caliphate. Thābit belonged to the Sabians of Harran, a Hellenized Semitic polytheistic astral religion that still existed in ninth-century Harran.[5] He originally was a money changer in a marketplace in Harran, before going to Baghdad.[6]

Thābit and his pupils lived in the midst of the most intellectually vibrant, and probably the largest, city of the time, Baghdad. Thābit came to Baghdad in the first place to work for the Banū Mūsā becoming a part of their circle and helping them translate Greek mathematical texts.[7] What is unknown is how Banū Mūsā and Thābit occupied himself with mathematics, astronomy, astrology, magic, mechanics, medicine, and philosophy. Later in his life, Thābit's patron was the Abbasid Caliph al-Mu'tadid (reigned 892–902), whom he became a court astronomer for.[7] Thābit became the Caliph's personal friend and courtier. Thābit died in Baghdad in 901. His son, Sinan ibn Thabit and grandson, Ibrahim ibn Sinan would also make contributions to the medicine and science.[8] By the end of his life, Thābit had managed to write 150 works on mathematics, astronomy, and medicine.[9] With all the work done by Thābit, most of his work has not lasted time. There are less than a dozen works by him that have survived.[8]

Translation

Thābit's native language was Syriac,[10] which was the Middle Aramaic variety from Edessa, and he was fluent in both Medieval Greek and Arabic.[11] He was the author to multiple treaties. Due to him being trilingual, Thābit was able to have a major role during the Graeco-Arabic translation movement.[8] He would also make a school of translation in Baghdad.[9]

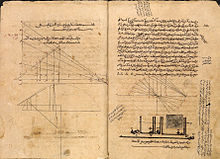

Thābit translated from Greek into Arabic works by Apollonius of Perga, Archimedes, Euclid and Ptolemy. He revised the translation of Euclid's Elements of Hunayn ibn Ishaq. He also rewrote Hunayn's translation of Ptolemy's Almagest and translated Ptolemy's Geography.Thābit's translation of a work by Archimedes which gave a construction of a regular heptagon was discovered in the 20th century, the original having been lost.[citation needed]

Astronomy

Thābit is believed to have been an astronomer of Caliph Al-Mu'tadid.[12] Thābit was able to use his mathematical work on the examination of Ptolemaic astronomy.[8] The medieval astronomical theory of the trepidation of the equinoxes is often attributed to Thābit.[citation needed] But it had already been described by Theon of Alexandria in his comments of the Handy Tables of Ptolemy. According to Copernicus, Thābit determined the length of the sidereal year as 365 days, 6 hours, 9 minutes and 12 seconds (an error of 2 seconds). Copernicus based his claim on the Latin text attributed to Thābit. Thābit published his observations of the Sun.[citation needed] In regards to Ptolemy's Planetary Hypotheses, Thābit examined the problems of the motion of the sun and moon, and the theory of sundials.[8] When looking at Ptolemy's Hypotheses, Thābit ibn Qurra found the Sidereal year which is when looking at the Earth and measuring it against the background of fixed stars, it will have a constant value.[13]

Thābit was also an author and wrote De Anno Solis. This book contained and recorded facts about the evolution in astronomy in the ninth century.[12] Thābit mentioned in the book that Ptolemy and Hipparchus believed that the movement of stars is consistent with the movement commonly found in planets. What Thābit believed is that this idea can be broadened to include the Sun and moon.[12] With that in mind, he also thought that the solar year should be calculated by looking at the sun's return to a given star.[12]

Mathematics

In mathematics, Thābit discovered an equation for determining amicable numbers. He also wrote on the theory of numbers, and extended their use to describe the ratios between geometrical quantities, a step which the Greeks did not take. He would in addition work on Transversal (geometry) theorem.[9]

He is known for having calculated the solution to a chessboard problem involving an exponential series.[14]

He computed the volume of the paraboloid.[15]

He also described a generalization of Pythagoras' theorem.[16] He was able to provide proof of the theorem through dissection.[9] Thābit's contributions included proof of the Pythagoras' theorem and Euclid's fifth postulate.[8] In regards to the Pythagorean Theorem, Thābit used a method reduction and composition to find proof.[17] In regards to Euclid postulates, Thābit believed that geometry should be based on motion and more generally, physics.[18] With that in mind, his argument was that geometry was tied with the equality and differences of magnitudes of such things like lines and angles.[18] He would also write commentary for Archimedes's Liber Assumpta.[9]

Physics

In physics, Thābit rejected the Peripatetic and Aristotelian notions of a "natural place" for each element. He instead proposed a theory of motion in which both the upward and downward motions are caused by weight, and that the order of the universe is a result of two competing attractions (jadhb): one of these being "between the sublunar and celestial elements", and the other being "between all parts of each element separately".[19] and in mechanics he was a founder of statics.[20] In addition, Thābit's Liber Karatonis contained proof of the law of the lever. This work was the result of combining Aristotelian and Archimedean ideas of dynamics and mechanics.[9]

One of Qurra's most important pieces of text is his work with the Kitab fi 'l-qarastun. This text consists of Arabic mechanical tradition.[21] Another piece of important text is Kitab fi sifat alqazn, which discussed concepts of equal-armed balance. Qurra was reportedly one of the first to write about the concept of equal-armed balance or at least to systematize the treatment.

Qurra sought to establish a relationship between forces of motion and the distance traveled by the mobile.[21]

Works

Only a few of Thābit's works are preserved in their original form.

- On the Sector-Figure which deals with Menelaus' theorem.[22]

- On the Composition of Ratios[22]

- Kitab fi 'l-qarastun (Book of the Steelyard) [21]

- Kitab fi sifat alwazn (Book on the Description of Weight)[21] - Short text on equal-armed balance

Eponyms

See also

- Al-Battani, a contemporary Sabian astronomer and mathematician

References

- ^ Panza, Marco (2008). "The Role of Algebraic Inferences in Na'īm Ibn Mūsā's Collection of Geometrical Propositions". Arabic Sciences and Philosophy. 18 (2): 165–191. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.491.4854. doi:10.1017/S0957423908000532. S2CID 73620948.

- ^ For the Arabic name, see Rashed & Morelon 1960–2007; for the {{tranliteration|ar|nisba al-Ṣābiʾ applied as a family name, see De Blois 1960–2007; for the Latin name, see Latham 2003, p. 403.

- ^ Rashed 2009b, pp. 23–24; Holme 2010.

- ^ Holme 2010.

- ^ De Blois 1960–2007; Hämeen-Anttila 2006, p. 43, note 112; Van Bladel 2009, p. 65; Rashed 2009a, p. 646; Rashed 2009b, p. 21; Roberts 2017, pp. 253, 261–262. Some scholars have also suggested that he adhered to Mandaeism, a Gnostic baptist sect whose members were likewise called 'Sabians' (see Drower 1960, pp. 111–112; Nasoraia 2012, p. 39).

- ^ Gingerich 1986; Rashed & Morelon 1960–2007.

- ^ a b "Thābit ibn Qurrah | Arab mathematician, physician, and philosopher". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-11-20.

- ^ a b c d e f "Thabit ibn Qurra". islamsci.mcgill.ca. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- ^ a b c d e f Shloming, Robert (1970). "Thabit Ibn Qurra and the Pythagorean Theorem". The Mathematics Teacher. 63 (6): 519–528. doi:10.5951/MT.63.6.0519. ISSN 0025-5769. JSTOR 27958444.

- ^ Rashed & Morelon 1960–2007; "Thabit biography". www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk.

The sect, with strong Greek connections, had in earlier times adopted Greek culture, and it was common for members to speak Greek although after the conquest of the Sabians by Islam, they became Arabic speakers. There was another language spoken in southeastern Turkey, namely Syriac, which was based on the East Aramaic dialect of Edessa. This language was Thābit ibn Qurra's native language, but he was fluent in both Greek and Arabic.

- ^ Rashed & Morelon 1960–2007.

- ^ a b c d Carmody, Francis J. (1955). "Notes on the Astronomical Works of Thabit b. Qurra". Isis. 46 (3): 235–242. doi:10.1086/348408. ISSN 0021-1753. JSTOR 226342. S2CID 143097606.

- ^ Cohen, H. Floris (2010). "Greek Nature-Knowledge Transplanted". GREEK NATURE-KNOWLEDGE TRANSPLANTED:: THE ISLAMIC WORLD. Four Civilizations, One 17th-Century Breakthrough. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 53–76. doi:10.2307/j.ctt45kddd.6. ISBN 978-90-8964-239-4. JSTOR j.ctt45kddd.6. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Masood, Ehsad (2009). Science and Islam A History. Icon Books Ltd. pp. 48–49.

- ^ Smith, David Eugen (1925). History of Mathematics, Volume II. p. 685.

- ^ Aydin Sayili (Mar 1960). "Thâbit ibn Qurra's Generalization of the Pythagorean Theorem". Isis. 51 (1): 35–37. doi:10.1086/348837. JSTOR 227603. S2CID 119868978.

- ^ Sayili, Aydin (1960). "Thâbit ibn Qurra's Generalization of the Pythagorean Theorem". Isis. 51 (1): 35–37. doi:10.1086/348837. ISSN 0021-1753. JSTOR 227603. S2CID 119868978.

- ^ a b Sabra, A. I. (1968). "Thābit Ibn Qurra on Euclid's Parallels Postulate". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 31: 12–32. doi:10.2307/750634. ISSN 0075-4390. JSTOR 750634. S2CID 195056568.

- ^ Mohammed Abattouy (2001). "Greek Mechanics in Arabic Context: Thabit ibn Qurra, al-Isfizarı and the Arabic Traditions of Aristotelian and Euclidean Mechanics", Science in Context 14, p. 205-206. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Holme 2010.

- ^ a b c d Abattouy, Mohammed (June 2001). "Greek Mechanics in Arabic Context: Thābit ibn Qurra, al-Isfizārī and the Arabic Traditions of Aristotelian and Euclidean Mechanics". Science in Context. 14 (1–2): 179–247. doi:10.1017/s0269889701000084. ISSN 0269-8897. S2CID 145604399.

- ^ a b Van Brummelen, Glen (2010-01-26). "Review of "On the Sector-Figure and Related Texts"". MAA Reviews. Retrieved 2017-05-12.

Sources used

- De Blois, F.C. (1960–2007). "Ṣābiʾ". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0952.

- Drower, E.S. (1960). The Secret Adam: A Study of Nasoraean Gnosis. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 654318531.

- Gingerich, Owen (1986). "Islamic Astronomy". Scientific American. 254 (4): 74–83. Bibcode:1986SciAm.254d..74G. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0486-74. ISSN 0036-8733. JSTOR 24975932.

- Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko (2006). The Last Pagans of Iraq: Ibn Waḥshiyya and His Nabatean Agriculture. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15010-2.

- Holme, Audun (2010). Geometry : our cultural heritage (2nd ed.). Heidelberg: Springer. p. 188. ISBN 978-3-642-14440-0. Retrieved 2021-03-10.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Latham, J. D. (2003). "Review of Richard Lorch's 'Thabit ibn Qurran: On the Sector-Figure and Related Texts'". Journal of Semitic Studies. 48 (2): 401–403. doi:10.1093/jss/48.2.401.

- Nasoraia, Brikhah S. (2012). "Sacred Text and Esoteric Praxis in Sabian Mandaean Religion". In Çetinkaya, Bayram (ed.). Religious and Philosophical Texts: Rereading, Understanding and Comprehending Them in the 21st Century. Istanbul: Sultanbeyli Belediyesi. pp. vol. I, pp. 27–53.

- Rashed, Marwan (2009a). "Thabit ibn Qurra sur l'existence et l'infini: les réponses aux questions posées par Ibn Usayyid". In Rashed, Roshdi (ed.). Thābit ibn Qurra: Science and Philosophy in Ninth-Century Baghdad. Scientia Graeco-Arabica. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 619–673. doi:10.1515/9783110220797.6.619. ISBN 9783110220780.

- Rashed, Roshdi (2009b). "Thābit ibn Qurra: From Ḥarrān to Baghdad". In Rashed, Roshdi (ed.). Thābit ibn Qurra: Science and Philosophy in Ninth-Century Baghdad. Scientia Graeco-Arabica. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 15–24. doi:10.1515/9783110220797.1.15. ISBN 9783110220780.

- Rashed, Roshdi; Morelon, Régis [in French] (1960–2007). "Thābit b. Ḳurra". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_7507.

- Roberts, Alexandre M. (2017). "Being a Sabian at Court in Tenth-Century Baghdad". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 137 (2): 253–277. doi:10.17613/M6GB8Z.

- Van Bladel, Kevin (2009). "Hermes and the Ṣābians of Ḥarrān". The Arabic Hermes: From Pagan Sage to Prophet of Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 64–118. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195376135.003.0003. ISBN 978-0-19-537613-5.

Further reading

- Roshdi Rashed (ed.), Thābit ibn Qurra. Science and Philosophy in Ninth-Century Baghdad, Berlin, Walter de Gruyter, 2009.

- Francis J. Carmody: The astronomical works of Thābit b. Qurra. 262 pp. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1960.

- Rashed, Roshdi (1996). Les Mathématiques Infinitésimales du IXe au XIe Siècle 1: Fondateurs et commentateurs: Banū Mūsā, Ibn Qurra, Ibn Sīnān, al-Khāzin, al-Qūhī, Ibn al-Samḥ, Ibn Hūd. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) Reviews: Seyyed Hossein Nasr (1998) in Isis 89 (1) pp. 112-113; Charles Burnett (1998) in Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 61 (2) p. 406. - Churton, Tobias. The Golden Builders: Alchemists, Rosicrucians, and the First Freemasons. Barnes and Noble Publishing, 2006.

- Hakim S Ayub Ali. Zakhira-i Thābit ibn Qurra (preface by Hakim Syed Zillur Rahman), Aligarh, India, 1987.

External links

- Palmeri, JoAnn (2007). "Thābit ibn Qurra". In Thomas Hockey; et al. (eds.). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 1129–30. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0. (PDF version)

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Al-Sabi Thabit ibn Qurra al-Harrani", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Rosenfeld, B. A.; Grigorian, A. T. (2008) [1970-80]. "Thābit Ibn Qurra, Al-Ṣābiʾ Al-Ḥarrānī". Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Encyclopedia.com.

- Thabit ibn Qurra on Astrology & Magic