Synthetic cannabinoids are a class of molecules that bind to cannabinoid receptors in the body–the same receptors that the cannabinoids in cannabis plants, such as THC and CBD–attach to. Synthetic cannabinoids are also designer drugs that are often sprayed onto plant matter.[1] They are typically consumed through smoking,[2] although more recently they have been consumed in a concentrated liquid form in the US and UK.[3] They have been marketed as herbal incense, or “herbal smoking blends”[2] and sold under common names like K2, Spice,[4] and Synthetic Marijuana.[1] They are also often labeled “not for human consumption.”[4]

When synthetic cannabinoid blends first went on sale in the early 2000s, it was thought that they achieved the psychoactive effects through a mixture of natural herbs. Laboratory analysis in 2008 showed that this was not the case, and that many in fact contained synthetic cannabinoids.[2] Today, synthetic cannabinoids are the most common new psychoactive substances to be reported. From 2008 to 2014, 142 synthetic cannabinoids were reported to the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA).[5] A large and complex variety of synthetic cannabinoids are designed in an attempt to avoid the legal restrictions on cannabis, making synthetic cannabinoids designer drugs.[2]

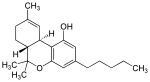

Most synthetic cannabinoids are agonists of the cannabinoid receptors, and many have been designed based on THC,[6] the natural cannabinoid with the strongest binding affinity to the CB1 receptor, which is linked to the psychoactive effects or “high” of marijuana.[7] These synthetic analogs often have greater binding affinity and greater potency to the CB1 receptors. There are several synthetic cannabinoid families (e.g. CP-xxx, WIN-xxx, JWH-xxx, UR-xxx, and PB-xx) classified based on the base structure.[8]

Reported user negative effects include palpitations, paranoia, intense anxiety, nausea, vomiting, confusion, poor coordination, and seizures. There have also been reports of a strong compulsion to re-dose, withdrawal symptoms, and persistent cravings.[5] There have been several deaths linked to synthetic cannabinoids. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that the number of deaths from synthetic cannabinoid use tripled between 2014 and 2015.[9]

Naming Synthetic Cannabinoids

Many of the early synthetic cannabinoids that were synthesized for use in research were named after either the scientist who first synthesized them or the institution or company where they originated. For example, JWH compounds are named after John W. Huffman and AM compounds are named after Alexandros Makriyannis, the scientists who first synthesized those cannabinoids. HU compounds are named after Hebrew University in Jerusalem, the institution where they were first synthesized, and CP compounds are named after Carl Pfizer, the company where they were first synthesized.

Some of the names of synthetic cannabinoids synthesized for recreational use were given names to help market the products. For example, AKB-48 is the name of a popular Japanese girl band; 2NE1 is the name of a South Korean girl band; and XLR-11 was named after the first USA-developed liquid fuel rocket for aircrafts. Now many synthetic cannabinoids are assigned names derived from their chemical names. For example, APICA (also known as 2NE1) comes from N-(1-adamantyl)-1-pentyl-1H-indole-3-carboxamide and APINACA (also known as AKB-48) comes from N-(1-adamantyl)-1-pentyl-1H-indazole-3-carboxamide.[10]

Common Names

Use of the term “synthetic marijuana” to describe products containing synthetic cannabinoids is controversial and, according to Dr. Lewis Nelson, a medical toxicologist at the NYU School of Medicine, a misnomer. Nelson claims that relative to marijuana, products containing synthetic cannabinoids “are really quite different, and the effects are much more unpredictable. It’s dangerous.”[11] Since the term synthetic does not apply to the plant, but rather to the cannabinoid that the plant contains (THC), the term synthetic cannabinoid is more appropriate.[12]

Synthetic cannabinoids are known by a number of brand names including K2, Spice, Black Mamba, Bombay Blue, Genie, Zohai,[13] Banana Cream Nuke, Krypton, Lava Red, and many more.[14] They are often called “synthetic marijuana,” “natural herbs,” “herbal incense,” or “herbal smoking blends” and often labeled “not for human consumption.”[15]

According to the Psychonaut Web Mapping Research Project, synthetic cannabinoids, sold under the brand name “Spice,” were first released in 2005 by the now-dormant company The Psyche Deli in London, UK. In 2006, the brand gained popularity. According to the Financial Times, the assets of The Psyche Deli rose from £65,000 in 2006 to £899,000 in 2007. The EMCDDA reported in 2009 that Spice products were identified in 21 of the 30 participating countries.[16]

Uses

Synthetic cannabinoids were originally used for cannabinoid research focusing on tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main psychoactive and analgesic compound found in the cannabis plant. Synthetic cannabinoids were used in part due to legal restrictions on natural cannabinoids, which make them very hard to obtain for research. Tritium-labelled cannabinoids such as CP-55,940 were instrumental in discovering the cannabinoid receptors in the early 1990s.[17]

Some early synthetic cannabinoids were also used in clinics. Nabilone, a first generation synthetic THC analog, has been used as an antiemetic, a drug to combat vomiting and nausea, since 1981. Synthetic THC (marinol, dronabinol) has been used as an antiemetic since 1985 and an appetite stimulant since 1991.[18]

In the early 2000s, synthetic cannabinoids started being used for recreational drug use in an attempt to get similar effects to cannabis. Since synthetic cannabinoids had different molecular structures to THC and other illegal cannabinoids, synthetic cannabinoids were technically legal, or at least not illegal, to sell or possess. Since the discovery of the use of synthetic cannabinoids for recreational use in 2008, some synthetic cannabinoids have been made illegal, but new analogs are continually synthesized that get around those restrictions. Synthetic cannabinoids have also been used recreationally because they are inexpensive and they are typically not identified by the standard marijuana drug tests. Unlike nabilone, the synthetic cannabinoids found being used for recreational use do not have any documented therapeutic effects.[19]

Adverse effects

Synthetic cannabinoids frequently produce adverse effects which lead to hospitalization or referrals to poison control centers.[20][21] Synthetic cannabinoids can be any of a number of different drugs, each with different effects.[20] There is no way to describe general effects among all the different chemicals because they all have different effects.[20] Also, each chemical will have different effects at different dosages, but because the drugs are crudely manufactured, it is not possible to know what chemicals the drugs contain or how much of any chemical a user is taking.[20][22]

Synthetic cannabinoids are potent drugs capable of causing clinical intoxication and death[22] (probably due to CNS depression and hypothermia) when used. Many compounds have been banned in the U.S. and numerous other countries, although loopholes remain and new examples continue to be encountered on a regular basis with changed chemical make-ups designed to get around bans.[23][24]

No official studies have been conducted on the effects of synthetic cannabinoids on humans (as is often the case with illegal and potentially toxic compounds).[25] However, reports describing effects seen in patients seeking medical care after taking synthetic cannabinoids have been published. Compared to cannabis and its active cannabinoid THC, the adverse effects are often much more severe and can include hypertension, tachycardia, myocardial infarction,[26] agitation, vomiting, hallucinations, psychoses, seizures, convulsions[27] and panic attacks.[28][29][30][31][32] Among individuals who need emergency treatment after using synthetic cannabis, the most common symptoms are accelerated heartbeat, high blood pressure, nausea, blurred vision, hallucination and agitation.[33] Other symptoms included epileptic seizures, and acute psychosis.[33]

At least one death has been linked to overdose of synthetic cannabinoids[34] and in Colorado three deaths in September 2013 have been investigated for being linked to synthetic cannabinoids.[35]

These more severe adverse effects in contrast to use of marijuana are thought to stem from the fact that many of the synthetic cannabinoids are full agonists to the cannabinoid receptors, CB1R and CB2R, compared to THC which is only a partial agonist and thus not able to saturate and activate all of the receptor population regardless of dose and resulting concentration.[36] It has also been seen that phase 1 metabolism of JWH-018 results in at least nine monohydroxylated metabolites and with at least three of the metabolites shown to have full agonistic effect on CB1R, which, compared to metabolism of THC, only results in one psychoactive monohydroxylated metabolite. This may further explain the increased toxicity of synthetic cannabinoids compared to THC.[34]

Professor John W. Huffman, who first synthesised many of the cannabinoids used in synthetic cannabis mimics, is quoted as saying, "People who use it are idiots.[25] You don't know what it's going to do to you."[37] A user who consumed 3 g of Spice Gold every day for several months showed withdrawal symptoms, similar to those associated with withdrawing from the use of narcotics. Doctors treating the user also noted that his use of the product showed signs associated with addiction.[38] One case has been reported wherein a user, who had previously suffered from cannabis-induced recurrent psychotic episodes, suffered reactivation of his symptoms after using Spice. Psychiatrists treating him have suggested that the lack of an antipsychotic chemical, similar to cannabidiol found in natural cannabis, may make synthetic cannabinoid products more likely to induce psychosis than natural cannabis.[39]

Studies are currently available which suggest an association between synthetic cannabinoids and psychosis.[40] The use of synthetic cannabinoids can be associated with psychosis and physicians are beginning to investigate possible use of synthetic cannabinoids in patients with inexplicable psychotic symptoms. In contrast to most other recreational drugs, the dramatic psychotic state induced by use of synthetic cannabinoids has been reported, in multiple cases, to persist for several weeks, and in one case for seven months, after complete cessation of drug use.[41] Individuals with risk factors for psychotic disorders are often counseled against using synthetic cannabinoids.[42]

In April 2018, the Centers for Disease Control issued a Clinical Action alert to health care providers across the United States advising of 89 confirmed cases of "serious unexplained bleeding" in Illinois. The cases are still being studied; however, 63 of the patients reported synthetic cannabinoid use, and laboratory analysis confirmed brodifacoum, a rat poison that causes bleeding, in at least 18 patients. This has lead the CDC to state that "a working hypothesis is the synthetic cannabinoids were contaminated with brodifacoum".[43]

Pharmacology

Relationship to cannabis

Use of the term "synthetic marijuana" to describe products containing synthetic cannabinoids is controversial and, according to Dr. Lewis Nelson, a medical toxicologist at the NYU School of Medicine, a misnomer. Nelson claims that relative to marijuana such products containing synthetic cannabinoids "are really quite different, and the effects are much more unpredictable. It's dangerous."[44] Since the term synthetic does not apply to the plant but rather to the chemical that the plant contains (tetrahydrocannabinol), the term synthetic cannabinoid itself is more appropriate.[45]

Research on the safety of synthetic cannabinoids is now being conducted and its findings published. Initial studies have been largely concerned with the role of synthetic cannabinoids in psychosis.

Synthetic cannabinoids may precipitate psychosis and in some cases it may be protracted. Some studies suggest that synthetic cannabinoid intoxication is associated with acute psychosis, worsening of previously stable psychotic disorders, and may trigger a chronic (long-term) psychotic disorder among vulnerable individuals such as those with a family history of mental illness.[46][47]

Synthetic cannabinoids are stated to be toxic and addictive to the brain but include a broad class of compounds in which neurotoxicity may vary substantially.[48]

List of synthetic cannabinoids

- 4-HTMPIPO

- 5F-AB-FUPPYCA, 5F-AB-PINACA, 5F-ADB, 5F-ADBICA, 5F-ADB-PINACA, 5F-AMB, 5F-AMB-PICA, 5F-APINACA, 5F-CUMYL-PINACA, 5F-EMB-PINACA, 5F-NNE1, 5F-PB-22, 5F-PCN, 5F-SDB-006

- A-836339

- AB-001, AB-005, AB-CHFUPYCA, AB-CHMINACA, AB-FUBICA, AB-FUBINACA, AB-PICA, AB-PINACA

- ADB-CHMINACA, ADB-FUBICA, ADB-FUBINACA, ADB-PINACA, ADBICA

- ADAMANTYL-THPINACA

- ADBICA

- ADSB-FUB-187

- AM251, AM-404, AM-630, AM-678 (= JWH-018), AM-679, AM-694, AM-1220, AM-1221, AM-1235, AM-1241, AM-1248, AM-2201, AM-2232, AM-2233, AM-2389

- AMB-CHMINACA, AMB-FUBINACA

- APICA, APINACA

- APP-FUBINACA

- BAY 38-7271, BAY 59-3074

- BB-22

- BIM-018

- BML-190

- BRL-4664

- Cannabicyclohexanol

- CB-13

- CP-47497, CP-55940, CP-55244

- CT-3

- CUMYL-PICA, CUMYL-PINACA, CUMYL-THPINACA

- DMA (5'-dimethylammonium delta-8-tetrahydrocannabinol), TMA (5'-trimethylammonium delta-8-tetrahydrocannabinol) (water-soluble)

- DMHP

- EAM-2201

- FAB-144

- FDU-NNE1, FDU-PB-22

- FUB-144, FUB-APINACA, FUB-JWH-018, FUB-PB-22, FUBIMINA

- GW-405,833

- HHC

- HU-210, HU-211, HU-239, HU-243, HU-308

- JWH-007, JWH-015, JWH-018, JWH-019, JWH-073, JWH-081, JWH-098, JWH-116, JWH-122, JWH-133, JWH-149, JWH-167, JWH-182, JWH-193, JWH-198, JWH-200, JWH-203, JWH-210, JWH-249, JWH-250, JWH-251, JWH-302, JWH-398, JWH-424

- JTE-907, JTE 7-31

- L-759,633, L-759,656

- LY-2183240, LY-320135

- MAM-2201

- MDA-19

- MDMB-CHMICA, MDMB-CHMINACA, MDMB-FUBICA, MDMB-FUBINACA

- MEPIRAPIM

- MN-18, MN-25

- Nantradol

- Nabilone

- Nabitan

- NESS-0327, NESS-040C5

- NM-2201

- NNE1

- O-774, O-1057, O-1812, O-2050, O-2694, O-6629

- Org 28611

- PB-22

- PF-03550096

- PTI-1, PTI-2

- PX-1, PX-2, PX-3

- RCS-4, RCS-8

- SDB-005, SDB-006

- SP-111

- SR-141716A, SR-144528

- STS-135

- Synhexyl

- THJ-018, THJ-2201

- UR-144

- WIN-48098, WIN-54461, WIN-55212-2, WIN-55225, WIN-56098

- XLR-11

CBD analogs

Ingredients

Synthetic cannabis mimics are sometimes claimed by the manufacturers to contain a mixture of traditionally used medicinal herbs, each of which producing mild effects, with the overall blend resulting in the cannabis-like intoxication produced by the product. Herbs listed on the packaging of Spice include Canavalia maritima (coastal jack-bean), Nymphaea caerulea (blue Egyptian water lily), Scutellaria nana (dwarf skullcap), Pedicularis densiflora (Indian warrior), Leonotis leonurus (lion's tail), Zornia latifolia (maconha brava), Nelumbo nucifera (lotus), and Leonurus sibiricus (honeyweed). However, when the product was analyzed by laboratories in Germany and elsewhere, it was found that many of the characteristic "fingerprint" molecules expected to be present from the claimed plant ingredients were not present. There were also large amounts of synthetic tocopherol present. This suggested that the actual ingredients might not have been the same as those listed on the packet, and a German government risk assessment of the product conducted in November 2008 concluded that it was unclear as to what the actual plant ingredients were, where the synthetic tocopherol had come from, and whether the subjective cannabis-like effects were actually produced by any of the claimed plant ingredients or instead caused by a synthetic cannabinoid drug.

Legal herbs

Unlike herbal smoking blends, synthetic cannabis mimics may use chemicals on their herbs, but both can use legal psychotropic herbs.[49] Some herbs used may be salvia divinorum[citation needed], Turnera diffusa (damiana), Nymphaea caerulea (blue lotus), passion flower, or other mildly psychoactive herbs that can be sold legally. In many cases the herbs have no effect on humans or are overpowered by the chemicals on them.

Pharmacodynamics

| Name | Structure | Binding affinity for the CB1 receptor | Binding affinity for the CB2 receptor |

|---|---|---|---|

| THC |  |

Ki = 40.7±1.7 nM[50] | Ki = 36.4±10 nM[50] |

| HU-210 |  |

Ki = 234 pM (100–800 times more potent than THC)[51] | |

| Cannabicyclohexanol |  |

Ki = unknown. Reported to be five times more potent than THC, based on physiological responses in rats.[52] | |

| JWH-073 |  |

Ki = 8.90±1.80 nM[50] | Ki = 38.0±24.0 nM[50] |

| JWH-018 |  |

Ki = 9.00±5.00 nM[50] | Ki = 2.94±2.65 nM[50] |

| AM-2201 |  |

Ki = 1.0 nM[53] | Ki = 2.6 nM[53] |

History

The first synthetic cannabinoids were synthesized by Roger Adams in the early 1940s. Early cannabinoid research concentrated on tetrahydrocannabinol or "THC" as the main psychoactive and analgesic compound found in the cannabis plant. Other natural cannabinoids such as cannabidiol or "CBD" are less well studied, and not illegal in most jurisdictions. Most synthetic cannabinoids are analogs of THC.

The first generation of THC analogs (synhexyl, nabilone, nabitan, nantradol) featured slight variations of the THC molecule, such as esterifying the phenolic hydroxy group, extending and branching of the pentyl side chain, or substituting nitrogen for oxygen in the benzopyran ring.[54] These analogs can be grouped into classical (HU-210), bicyclic (CP-55,940), and tricyclic (CP-55,244). Tritium-labelled cannabinoids such as [³H]CP-55,940 were instrumental in discovering the cannabinoid receptors in the early 1990s.[55]

Nabilone entered the clinic in 1981 as an antiemetic. Synthetic THC (marinol, dronabinol) entered the clinic in 1985 as an antiemetic and again in 1991 as an appetite stimulant.[56]

The second generation of THC analogs features compounds derived from anandamide (metanandamide), aminoalkylindole (WIN 55,212-2), pyrrole, pyrazole (SR-141716A), and indene (BAY 38-7271).

| CB₁ | CB₂ | |

|---|---|---|

| Agonist | Noladin ether | HU-308, JWH-133 |

| Antagonist | SR-141716A, LY-320135, AM-251 | SR-144528, AM-630 |

HU-210 is apparently the most active cannabinoid used at present. It is up to 800 times more active than THC in mice. AM-404 (a paracetamol metabolite) is an inhibitor of endocannabinoid cellular uptake, prolonging their effects.[57] Nabitan, O-1057 and TMA are water-soluble.

In January 2009, researchers at the University of Freiburg in Germany announced that an active substance in Spice was an undisclosed analogue of the synthetic cannabinoid CP 47,497.[58] Later that month, CP 47,497 along with its dimethylhexyl, dimethyloctyl and dimethylnonyl homologues, were added to the German controlled drug schedules.[59][60] In May, the analogue of CP 47,497 was named "cannabicyclohexanol".[61]

In July 2010, it was announced that JWH-018 is one of the active components in at least three versions of Spice, which had been sold in a number of countries around the world since 2002, often marketed as incense.[62][63][64][65] Another potent synthetic cannabinoid, HU-210, has been reported to have been found in Spice seized by U.S. Customs and Border Protection.[66] An analysis of samples acquired four weeks after the German prohibition of JWH-018 took place found that the compound had been replaced with JWH-073.[67]

Different ratios of JWH-018 and CP 47,497 and their analogues have been found in different brands of synthetic cannabis mimic products[68] and manufacturers constantly change the composition of their products.[69] The amount of JWH-018 in Spice has been found to vary from 0.2% to 3%.[70]

Other non-cannabinoid ingredients have also been found in synthetic cannabis mimics around the world, but they do not produce classical cannabis intoxication effects. This includes substituted cathinone derived stimulant drugs such as 4-methylbuphedrone and 4-methyl-alpha-PPP, and psychedelic tryptamine derivatives such as 4-HO-DET.[71][72] In 2013, a designer opioid drug, AH-7921, was detected in smoking blends in Japan, along with several novel cannabinoids and a cathinone analogue.[73]

According to the Psychonaut Web Mapping Research Project, synthetic cannabinoids, sold under the brand name Spice, first appeared in Europe in 2004.[74] The brand "Spice" was released in 2004 by the now-dormant company The Psyche Deli in London, UK. In 2006 the brand gained popularity. According to the Financial Times, the assets of The Psyche Deli rose from £65,000 in 2006 to £899,000 in 2007.[75] The EMCDDA[clarification needed] reported in 2009 that Spice products were identified in 21 of the 30 participating countries. Because Spice was the dominant brand until 2009, the competing brands that started to appear from 2008 on were also dubbed Spice. Spice can, therefore, refer to both the brand Spice, as to all herbal blends with synthetic cannabinoids added.

In 2009 a survey of readers of a popular English magazine Mixmag found that 12.5% had used synthetic cannabis mimics, compared to 85% who had used cannabis.[76]

Detection in Bodily Fluids

Synthetic cannabinoids are typically not identified by the standard marijuana drug tests including the immunoassay test (EMIT), GC-MS screening, and multi-target screening by LC-GC/MS because those tests only detect the presence of THC and its metabolites.[77][78] Although most synthetic cannabinoids are analogs of THC, they are structurally different enough that, for example, the specific antibodies in the EMIT for marijuana do not bind to them.[79] Also, due to their high potency, a very small dose of synthetic cannabinoids is used; moreover, synthetic cannabinoids are highly metabolized by the body, so the window to detect the parent drug (the synthetic cannabinoid itself) in blood and oral fluid is very small.[80]

Serum concentrations of synthetic cannabinoids are generally in the 1–10 μg/L range during the first few hours after recreational usage and the metabolites are usually present in urine at similar concentrations.[81] Little to no parent drug is present in urine, so there is a lot of research to try and identify the major urinary metabolites that could be used as markers of synthetic cannabinoid intake.[82] The major urinary metabolites in most cases are formed by oxidation of the alkyl side-chain to an alcohol and carboxylic acid followed by glucuronide conjugation and also by N-dealkylation and aromatic hydroxylation.[83] For example, the main metabolites of JWH-018, of which there are over 20, include carboxylated, monohydroxylated, dihydroxylated, and trihydroxylated metabolites, but they are mostly excreted in urine as glucuronide conjugates.[84] The presence of synthetic cannabinoids or their metabolites in bodily fluids may be determined using specifically-targeted commercially available immunoassay screening methods (EMIT), while liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry is most often used for confirmation and quantitation.[85][86][87] There are commercially available EMIT kits for the screening of the synthetic cannabinoids JWH-018, JWH-073, JWH-398, JWH-200, JWH-019, JWH-122, JWH-081, JWH-250, JWH-203, CP-47,497, CP-47,497-C8, HU-210, HU-211, AM-2201, AM-694, RCS-4, and RCS-8 through companies like NMS Labs, Cayman Chemical, and Immunoanalysis Corporation.[88]

Legal Restrictions and Regional Availability

Europe

Austria

The Austrian Ministry of Health announced on December 18, 2008 that Spice would be controlled under Paragraph 78 of their drug law on the grounds that it contains an active substance that affects the functions of the body, and the legality of JWH-018 is under review.[89][90]

Finland

Spice blends are classified as a medicine in Finland, and, therefore, it is illegal to order them without a prescription. In practice, it is impossible to get a prescription.[citation needed]

France

JWH-018, CP 47,497 (and its homologues) and HU-210 were all made illegal in France on February 24, 2009.[79]

Germany

JWH-018, CP 47,497 and the C6, C8 and C9 homologues of CP 47,497 have been illegal in Germany since January 22, 2009.[55][77] Since November 26, 2016 all substances belonging to the group of synthetic cannabinoids are illegal in Germany.[78]

Ireland

Since June 2010, JWH-018, along with a variety of other designer drugs, has been illegal.[80]

Latvia

JWH-018, JWH-073, CP 47,497 (and its homologues) and HU-210 as well as leonotis leonurus have been all banned in Latvia since 2005.[81] After the first confirmed lethal case from the use of legal drugs in late 2013, parliament significantly increased the number of temporarily banned substances used in Spice and similar preparations. On April 3, 2014, parliament made selling of the temporarily banned substances a criminal offence.[82]

Poland

JWH-018 and many of the herbs mentioned on the ingredient lists of Spice and similar preparations were made illegal in May 2009. The bill was passed by the Polish Sejm[83][84] and Polish Senat[85] and was signed by the President.[86]

Romania

Spice was made illegal in Romania on February 15, 2010.[87]

Russia

On April 9, 2009, the Chief Medical Officer of the Russian Federation issued a resolution on reinforcing control over the sales of smoking blends. These blends, marketed under the trade names AM-HI-CO, Dream, Spice (Gold, Diamond), Zoom, Ex-ses, Yucatán Fire and others, have been declared to contain Salvia divinorum, Hawaiian wood rose, and blue lotus, and are prohibited to be sold. These substances have been found to have "psychotropic, narcotic effects, contain poisonous components and represent potential threat for humans". The resolution does not mention JWH-018 or other synthetic cannabinoids.[88] On January 14, 2010, the Russian government issued a statement including 23 synthetic cannabinoids found in smoking blends Hawaiian Rose and Blue Lotus on the list of prohibited narcotic and psychotropic substances.[89]

About 780 new psychoactive substances were added to the list from 2011 to 2014. The drugmakers avoided all the bans by making slight changes to the drugs. In the autumn of 2014, more than two thousand Spice consumers in Russia sought medical attention, one thousand were admitted to hospitals, and 40 people died[90] On October 30, 2014, President Vladimir Putin brought in a bill that increased the penalty for selling or consuming smoking blends from a fine to up to eight years in prison.[91]

Slovakia

Spice is legal in Slovakia. The National Anti-Drug Unit is considering adding it to the list of controlled substances.[92] The latest anti-drug law version (468/2009) valid since January 2010 does not mention active compounds of Spice.[93]

Spain

Spice is unregulated in Spain. For this reason, Spice is available in grow shop stores or cannabis related stores, and it can be bought and shipped online without any legal impediment from those kind of stores.[94] However, as Spanish law permits growing up to two cannabis plants per household, and the possession and consumption of cannabis on private property is also legal, cannabis alternatives like Spice are largely redundant and thus remain relatively unknown in Spain.[95]

Sweden

CP 47,497-C6, CP 47,497-C7, CP 47,497-C8, CP 47,497-C9, JWH-018, JWH-073 and HU-210 were all made illegal in Sweden on September 15, 2009. The bill was accepted on July 30, 2009 and was put in effect on September 15, 2009.[96]

Switzerland

Spice has been banned in Switzerland.[97]

Turkey

Spice, which is colloquially called bonzai in Turkey, was added to the list of drugs and psychotropic substances on July 1, 2011 by the law numbered as 2011/1310 B.K.K. (February 13, 2011 and the Official Gazette No. 27845)[98]

United Kingdom

Many cannabinoids were legal in the United Kingdom until December 2009, when they were classified as Class B drugs.[99] The UK continued to ban new synthetic cannabinoids as they came to market but they were typically replaced instantly by novel alternatives. In May 2016 the Psychoactive Substances Act[100] came into force, which intends to restrict the production, sale and supply of new psychoactive substances.

North America

Canada

Spice is not specifically prohibited in Canada, but synthetic cannabis mimics are listed as a schedule II drug. Schedule II of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act makes reference to specific synthetic compounds JWH-XXX and AM-XXXX, although is not limiting to those identified.[117][118] Health Canada is debating the subject.[119][120]

United States

See also: JWH-018 § United States

The case of David Mitchell Rozga, an American teenager from Indianola, Iowa, brought international attention to K2. Rozga shot himself in the head with a family owned hunting rifle in an apparent suicide in June 6, 2010. After news of Rozga's death, it was reported by friends that they had smoked K2 with Rozga approximately one hour before his death. The nature of his death and reports from numerous family members had led investigators to suspect that it was likely Rozga was under the influence of a mind-altering substance at the time of his death. The death of Rozga has been used as a face of political lobbying against the continuation of K2 and other legal synthetic drugs, such as bath salts.

Following the incident, an act to ban the use and distribution of the drug was proposed by US Senator Chuck Grassley of Iowa as the "David Mitchell Rozga Act." It was approved into legislation by the United States Congress in June 2011.[121] On July 10, 2012, President Barack Obama signed the Synthetic Drug Abuse Prevention Act of 2012 into law. It banned synthetic compounds commonly found in synthetic marijuana, placing them under Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act.[72]

Prior to that, some synthetic cannabinoids (HU-210) were scheduled in the US under federal law, while others (JWH-073) have been temporarily scheduled until final determination of their status can be made.[122][123][124][125] The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) considers synthetic cannabinoids to be a "drug of concern,"[126] citing "...a surge in emergency-room visits and calls to poison-control centers. Adverse health effects associated with its use include seizures, hallucinations, paranoid behavior, agitation, anxiety, nausea, vomiting, racing heartbeat, and elevated blood pressure."[127][128]

Several states independently passed acts making it illegal under state law, including Kansas in March 2010,[129] Georgia and Alabama in May 2010,[130][131] Tennessee and Missouri in July 2010,[132][133] Louisiana in August 2010,[citation needed]Mississippi in September 2010,[citation needed] and Iowa.[134] An emergency order was passed in Arkansas in July 2010 banning the sale of synthetic cannabis mimics.[135] In October 2010, the Oregon Board of Pharmacy listed synthetic cannabinoid chemicals on its Schedule 1 of controlled substance, which means that the sale and possession of these substances is illegal under the Oregon Uniform Controlled Substances Act.[136] According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, several other states are also considering legislation, including New Jersey, New York, Florida, and Ohio.[133] Illinois passed a law on July 27, 2010 banning all synthetic cannabinoids that goes into effect January 1, 2011.[137] Michigan banned synthetic cannabinoids in October 2010,[138] and the South Dakota Legislature passed a ban on these products which was signed into law by Gov. Dennis Daugaard on February 23, 2012 (and which took immediate effect under an emergency clause of the state constitution).[139] Indiana banned synthetic cannabinoids in a law which became effective in March 2012.[140] North Carolina banned synthetic cannabis mimics by a unanimous vote of the state senate, due to concerns that its contents and effects are reasonably similar to cannabis, and may cause equal effects in terms of psychological dependency.[141][142]

Following cases in Japan involving the use of synthetic cannabinoids by navy, army and marine corps personnel resulted in the official banning of it,[143] a punitive general order issued on January 4, 2010 by the Commander Marine Corps Forces, Pacific prohibits the actual or attempted possession, use, sale, distribution and manufacture of synthetic cannabis mimics as well as any derivative, analogue or variant of it.[144] On June 8, 2010, the US Air Force issued a memorandum that banned the possession and use of Spice, or any other mood-altering substance except alcohol or tobacco, among its service members.[145]

On November 24, 2010, the DEA announced that it would make JWH-018, JWH-073, JWH-200, CP-47,497, and cannabicyclohexanol, which are often found in synthetic cannabis mimics, illegal using emergency powers.[146] They would be placed in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act, within a month of the announcement, and the ban would last for at least a year.[147][148] The temporary ban went into effect on March 1, 2011.[149]

On October 20, 2011, the Louisiana State University football program announced that it had suspended three players, including star cornerback Tyrann Mathieu, who tested positive for synthetic cannabinoids.[150]

In July 2016, over 33 people were suspected to have overdosed on K2 and were rushed to the hospital. Police raided 5 Brooklyn bodegas in search of the synthetic cannabinoid.[151]

South America

Chile

The Chilean Ministry of Health on April 24, 2009, declared the sale of synthetic cannabis mimics to be illegal.[101]

Asia

South Korea

South Korea officially added JWH-018, CP 47,497, and HU-210 to the controlled substance list on July 1, 2009, effectively making those chemicals illegal.[102]

Japan

Japan has banned JWH-018, CP 47,497, and homologues, and HU-210 since October 2009.[citation needed]

United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates had stated that Spice is an illegal substance and possession or intent to sell is a jailable offense.[103]

Australasia

Australia

On June 17, 2011, the Western Australian government banned all of the synthetic cannabinoids found in already existing products, including brands such as Kronic, Kalma, Voodoo, Kaos, and Mango Kush. Western Australia was the first state in Australia to prohibit the sale of certain synthetic cannabinoids.[104][105] On June 18, 2013, an interim ban made a large list of product brands and synthetic substances illegal to sell anywhere in Australia.[106] This ban lapsed on October 13, 2013, and a permanent ban has not been imposed.[107] Synthetic cannabinoids and related products remain illegal in NSW, where a bill was passed on September 18, 2013, that bans entire families of synthetic drugs instead of only banning existing compounds that have been identified.[108][109] The introduction of this law makes NSW the first state in Australia to completely ban substances with psychoactive properties.[109]

New Zealand

Spice is illegal in New Zealand, it is classified as a Class C controlled drug.[110] The New Zealand Parliament passed a law in July 2013 banning the sale of legal highs in dairies and supermarkets, but allowing some "low risk" drugs to continue to be sold through speciality licensed shops.[111] Synthetic cannabinoids, as well as all other legal highs were outlawed at midnight on 7 May 2014, after a law was passed a week prior by the New Zealand government.[112]

An analysis of 41 different synthetic cannabis mimic blends sold commercially in New Zealand, conducted by the Institute of Environmental Science and Research and released in July 2011, found 11 different synthetic cannabinoid ingredients used, including JWH-018, JWH-073, AM-694, AM-2201, RCS-4, RCS-4 butyl homologue, JWH-210, JWH-081, JWH-250 (or possibly JWH-302, isomer not determined), JWH-203, and JWH-122—with between one and five different active ingredients, though JWH-018 was present in 37 of the 41 blends tested. In two brands, the benzodiazepine anxiolytic drug phenazepamwas also found, which is classified as a prescription medicine in New Zealand, and these brands were ordered to be removed from the market by emergency recall.[113][114] Since this time, a further 15 cannabinoid compounds have been detected as ingredients of synthetic cannabis mimicking blends in New Zealand and banned as temporary class drugs.[115] In 2013 another hypnotic medication, zaleplon, was found to have been used as an active ingredient in a blend that had been sold in New Zealand during 2011 and 2012.[116]

See Also

- List of designer drugs § Synthetic cannabinoids

- Designer Drugs

- Cannabinoid receptor

- Cannabinoid

- Endocannabinoid enhancer

- Endocannabinoid system

- Structural scheduling of synthetic cannabinoids

- Tetrahydrocannabinol

External Links

- Erowid

- Synthetic cannabinoid profile European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction

- Interactive model to help understand the structures of synthetic cannabinoids

References

- ^ a b Macher, R.; Burke, T.W.; Owen, S.S. "Synthetic Marijuana". FBI: Law Enforcement Bulletin. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Science, Live (2017-02-07). "Synthetic Marijuana Linked To Seizures, Psychosis And Death". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ^ Diao, X; Huestis, MA (2016-11-24). "Approaches, Challenges, and Advances in Metabolism of New Synthetic Cannabinoids and Identification of Optimal Urinary Marker Metabolites". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 101 (2): 239–253. doi:10.1002/cpt.534. ISSN 0009-9236.

- ^ a b Banister, Samuel D.; Stuart, Jordyn; Kevin, Richard C.; Edington, Amelia; Longworth, Mitchell; Wilkinson, Shane M.; Beinat, Corinne; Buchanan, Alexandra S.; Hibbs, David E. (2015-05-08). "Effects of Bioisosteric Fluorine in Synthetic Cannabinoid Designer Drugs JWH-018, AM-2201, UR-144, XLR-11, PB-22, 5F-PB-22, APICA, and STS-135". ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 6 (8): 1445–1458. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00107. ISSN 1948-7193.

- ^ a b Abouchedid, Rachelle; Ho, James H.; Hudson, Simon; Dines, Alison; Archer, John R. H.; Wood, David M.; Dargan, Paul I. (2016-12-01). "Acute Toxicity Associated with Use of 5F-Derivations of Synthetic Cannabinoid Receptor Agonists with Analytical Confirmation". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 12 (4): 396–401. doi:10.1007/s13181-016-0571-7. ISSN 1556-9039.

- ^ Cannaert, Annelies; Storme, Jolien; Franz, Florian; Auwärter, Volker; Stove, Christophe P. (2016-11-07). "Detection and Activity Profiling of Synthetic Cannabinoids and Their Metabolites with a Newly Developed Bioassay". Analytical Chemistry. 88 (23): 11476–11485. doi:10.1021/acs.analchem.6b02600. ISSN 0003-2700.

- ^ Rapaka, R.S.; Makriyannis, A., eds. (1987). "Structure-Activity Relationships of the Cannabinoids" (PDF). NIDA Research Monograph. 79 – via U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

{{cite journal}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "K2: Scary Drug or Another Drug Scare?". Newsweek. 2010-03-03. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions | Marijuana | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2018-03-16. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ^ "Synthetic cannabinoids in Europe | www.emcdda.europa.eu". www.emcdda.europa.eu. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ^ "New York Bans 'Synthetic Marijuana'". NPR.org. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ^ "Synthetic Cannabinoids: The Newest, Almost Illicit Drug of Abuse". www.mdedge.com. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ^ "K2 Trend Not Slowing Down". WebMD. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ^ Fattore, Liana; Fratta, Walter (2011-09-21). "Beyond THC: The New Generation of Cannabinoid Designer Drugs". Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 5. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2011.00060. ISSN 1662-5153. PMC 3187647. PMID 22007163.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Banister, Samuel D.; Stuart, Jordyn; Kevin, Richard C.; Edington, Amelia; Longworth, Mitchell; Wilkinson, Shane M.; Beinat, Corinne; Buchanan, Alexandra S.; Hibbs, David E. (2015-05-08). "Effects of Bioisosteric Fluorine in Synthetic Cannabinoid Designer Drugs JWH-018, AM-2201, UR-144, XLR-11, PB-22, 5F-PB-22, APICA, and STS-135". ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 6 (8): 1445–1458. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00107. ISSN 1948-7193.

- ^ European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2009). "Understanding the "Spice" Phenomenon" (PDF). EMCDDA 2009 Thematic Paper.

- ^ Pertwee, Roger G (2009-02-02). "Cannabinoid pharmacology: the first 66 years". British Journal of Pharmacology. 147 (S1): S163–S171. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706406. ISSN 0007-1188. PMC 1760722. PMID 16402100.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Stefania Crowther; Lois Reynolds; Tilli Tansey, eds. (2010). "The Medicalization of Cannabis" (PDF). Wellcome Witnesses to Twentieth Century Medicine. 40 – via Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL.

{{cite journal}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fattore, Liana; Fratta, Walter (2011-09-21). "Beyond THC: The New Generation of Cannabinoid Designer Drugs". Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 5. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2011.00060. ISSN 1662-5153. PMC 3187647. PMID 22007163.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d Interlandi, Jeneen; Consumer Reports (May 7, 2016). "Synthetic Marijuana Has Real Risks". Consumer Reports. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ^ Law, R; Schier, J; Martin, C; Chang, A; Wolkin, A; Centers for Disease Control, (CDC) (12 June 2015). "Notes from the Field: Increase in Reported Adverse Health Effects Related to Synthetic Cannabinoid Use - United States, January-May 2015". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 64 (22): 618–9. PMID 26068566.

- ^ a b Perraudin, Frances; Devlin, Hannah (15 April 2017). "'It's worse than heroin': how spice is ravaging homeless communities". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- ^ Trecki, J; Gerona, RR; Schwartz, MD (2015). "Synthetic cannabinoid-related illnesses and deaths". N. Engl. J. Med. 373 (2): 103–107. doi:10.1056/nejmp1505328. PMID 26154784.

- ^ Mills, B; Yepes, A; Nugent, K (2015). "Synthetic cannabinoids". Am. J. Med. Sci. 350 (1): 59–62. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000466. PMID 26132518.

- ^ a b "Fake pot that acts real stymies law enforcement". Associated Press. February 17, 2010. Retrieved April 21, 2010.

- ^ Mir, A; Obafemi, A; Young, A; Kane, C (December 2011). "Myocardial infarction associated with use of the synthetic cannabinoid k2". Pediatrics. 128 (6): e1622–7. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-3823. PMID 22065271.

- ^ Schneir, AB; Baumbacher, T (December 13, 2011). "Convulsions Associated with the Use of a Synthetic Cannabinoid Product". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 8 (1): 62–4. doi:10.1007/s13181-011-0182-2. PMC 3550227. PMID 22160733.

- ^ Jeanna Bryner (March 3, 2010). "Fake Weed, Real Drug: K2 Causing hallucinations in Teens". LiveScience. Retrieved April 21, 2010.

- ^ Vardakou, I; Pistos, C; Spiliopoulou, Ch (2010). "Spice drugs as a new trend: Mode of action, identification and legislation". Toxicology Letters. 197 (3): 157–62. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.06.002. PMID 20566335.

- ^ Auwärter, V.; et al. (2009). "'Spice' and other herbal blends: harmless incense or cannabinoid designer drugs?". Journal of mass spectrometry : JMS. 44 (5): 832–837. doi:10.1002/jms.1558. PMID 19189348.

- ^ Every-Palmer, S (2010). "Warning: Legal synthetic cannabinoid-receptor agonists such as JWH-018 may precipitate psychosis in vulnerable individuals". Addiction. 105 (10): 1859–60. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03119.x. PMID 20840203.

- ^ Müller, H.; Sperling, W.; Köhrmann, M.; Huttner, H.; Kornhuber, J.; Maler, J. (2010). "The synthetic cannabinoid Spice as a trigger for an acute exacerbation of cannabis induced recurrent psychotic episodes". Schizophrenia Research. 118 (1–3): 309–310. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2009.12.001. PMID 20056392.

- ^ a b "Legal highs linked to psychosis". New Zealand Herald. Apr 5, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Brents, L. K.; Reichard, E. E.; Zimmerman, S. M.; Moran, J. H.; Fantegrossi, W. E.; Prather, P. L. (2011). "Phase I hydroxylated metabolites of the K2 synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018 retain in vitro and in vivo cannabinoid 1 receptor affinity and activity". PLoS ONE. 6 (7): e21917. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621917B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021917. PMC 3130777. PMID 21755008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Coffman, K. (6 September 2013). "Colorado probes three deaths possibly linked to synthetic marijuana". Reuters. Denver. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ Fantegrossi, W. E.; Moran, J. H.; Radominska-Pandya, A; Prather, P. L. (2014). "Distinct pharmacology and metabolism of K2 synthetic cannabinoids compared to Δ9-THC: Mechanism underlying greater toxicity?". Life Sciences. 97 (1): 45–54. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2013.09.017. PMC 3945037. PMID 24084047.

- ^ "Fake Weed, Real Drug: K2 Causing Hallucinations in Teens". LiveScience. Retrieved November 24, 2010.

- ^ Zimmermann, U.; et al. (2009). "Withdrawal phenomena and dependence syndrome after the consumption of "spice gold"". Deutsches Arzteblatt international. 106 (27): 464–467. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2009.0464 (inactive 2017-01-28). PMC 2719097. PMID 19652769.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2017 (link) - ^ Müller, H.; Sperling, W.; Köhrmann, M.; Huttner, H.; Kornhuber, J.; Maler, J. (2010). "The synthetic cannabinoid Spice as a trigger for an acute exacerbation of cannabis induced recurrent psychotic episodes". Schizophrenia Research. 118 (1–3): 309–310. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2009.12.001. PMID 20056392.

- ^ Shalit, Nadav; Barzilay, Ran; Shoval, Gal; Shlosberg, Dan; Mor, Nofar; Zweigenhaft, Nofar; Weizman, Abraham; Krivoy, Amir (2016-07-05). "Characteristics of Synthetic Cannabinoid and Cannabis Users Admitted to a Psychiatric Hospital: A Comparative Study". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 77: e989. doi:10.4088/JCP.15m09938. ISSN 0160-6689. PMID 27379411.

- ^ Hurst, D; Loeffler, G; McLay, R (October 2011). "Psychosis associated with synthetic cannabinoid agonists: a case series". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 168 (10): 1119. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11010176. PMID 21969050.

- ^ Every-Palmer, S (September 1, 2011). "Synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018 and psychosis: an explorative study". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 117 (2–3): 152–7. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.01.012. PMID 21316162.

- ^ "Outbreak Alert: Potential Life-Threatening Vitamin K-Dependent Antagonist Coagulopathy Associated With Synthetic Cannabinoids Use". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. April 5, 2018.

- ^ "New York Bans 'Synthetic Marijuana'". NPR.org. March 30, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2015.

- ^ www.emed-journal.com Lapoint J, Nelson LS. Synthetic Cannabinoids: The Newest, Almost Illicit Drug of Abuse. Emergency Medicine 2011;43(2):26-28

- ^ "Cannabis, synthetic cannabinoids, and psychosis risk: What the evidence says" (PDF). Procon.org. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ "Medscape: Medscape Access". Medscape.com. Retrieved February 20, 2015.

- ^ Walton, Alice G. "Why Synthetic Marijuana Is More Toxic To The Brain Than Pot". Forbes.com. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ "What is Spice". SpiceAddictionSupport.org. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Aung, M. M.; Griffin, G.; Huffman, J. W.; Wu, M. J.; Keel, C.; Yang, B.; Showalter, V. M.; Abood, M. E.; Martin, B. R. (2000). "Influence of the N-1 alkyl chain length of cannabimimetic indoles upon CB1 and CB2 receptor binding". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 60 (2): 133–140. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(99)00152-0. PMID 10940540.

- ^ Devane, W. A.; et al. (1992). "A novel probe for the cannabinoid receptor". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 35 (11): 2065–2069. doi:10.1021/jm00089a018. PMID 1317925.

- ^ Compton, D.; Johnson, M.; Melvin, L.; Martin, B. (1992). "Pharmacological profile of a series of bicyclic cannabinoid analogs: classification as cannabimimetic agents". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 260 (1): 201–209. PMID 1309872.

- ^ a b WO patent 200128557, Makriyannis A, Deng H, "Cannabimimetic indole derivatives", granted June 7, 2001

- ^ Rao S. Rapaka; Alexandros Makriyannis, eds. (1987), Structure-Activity Relationships of the Cannabinoids (PDF), NIDA Research Monograph, vol. 79, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- ^ Roger Pertwee (2006), "Cannabinoid pharmacology: the first 66 years", British Journal of Pharmacology, 147: 163–171, doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706406, PMC 1760722, PMID 16402100

- ^ Stefania Crowther; Lois Reynolds; Tilli Tansey, eds. (2010), The Medicalization of Cannabis (PDF), Wellcome Witnesses to Twentieth Century Medicine, vol. 40, Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL

- ^ Raphael Mechoulam; Lumir Hanuš (2004), "The cannabinoid system: from the point of view of a chemist", in David Castle; Robin Murray (eds.), Marijuana and Madness: Psychiatry and Neurobiology, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–18

- ^ "Hauptwirkstoff von "Spice" identifiziert" (in German). pr.uni-freiburg.de. September 19, 2009. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ "Modedroge "Spice" ist verboten!" (in German). Bmg.bund.de. March 10, 2009. Retrieved August 24, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "BGBl I Nr. 3 vom January 21, 2009, 22. BtMÄndV vom 19. Jan 2009, S. 49–50" (PDF) (in German). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-05.

- ^ Uchiyama N, Kikura-Hanajiri R, Ogata J, Goda Y (May 2010). "Chemical analysis of synthetic cannabinoids as designer drugs in herbal products". Forensic Science International. 198 (1–3): 31–8. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.01.004. PMID 20117892.

- ^ "Gefährlicher Kick mit Spice (German)". Fr-online.de. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- ^ "Erstmals Bestandteile der Modedroge "Spice" nachgewiesen (German)". Haz.de. Retrieved August 24, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Spice enthält chemischen Wirkstoff (German)". Badische-zeitung.de. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- ^ Schifano, F.; Corazza, O.; Deluca, P.; Davey, Z.; Di Furia, L.; Farre', M.; Flesland, L.; Mannonen, M.; Pagani, S.; Peltoniemi, T.; Pezzolesi, C.; Scherbaum, N.; Siemann, H.; Skutle, A.; Torrens, M.; Van Der Kreeft, P. (2009). "Psychoactive drug or mystical incense? Overview of the online available information on Spice products". International Journal of Culture and Mental Health. 2 (2): 137–144. doi:10.1080/17542860903350888.

- ^ "Spice" – Plant material(s) laced with synthetic cannabinoids or cannabinoid mimicking compounds Archived July 3, 2009, at the Wayback Machine (U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration)

- ^ Lindigkeit, Rainer; Boehme, A; Eiserloh, I; Luebbecke, M; Wiggermann, M; Ernst, L; Beuerle, T (October 30, 2009). "Spice: A never-ending story?". Forensic Science International. 191 (1): 58–63. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.06.008. PMID 19589652.

- ^ Auwärter, V.; et al. (2009). "'Spice' and other herbal blends: harmless incense or cannabinoid designer drugs?". Journal of mass spectrometry : JMS. 44 (5): 832–837. doi:10.1002/jms.1558. PMID 19189348. Free version

- ^ Emanuel, C. E. J.; Ellison, B.; Banks, C. E. (2010). "Spice up your life: screening the illegal components of 'Spice' herbal products". Analytical Methods. 2 (6): 614. doi:10.1039/c0ay00200c.

- ^ Stafford, Ned. Synthetic Cannabis Mimic Found in Herbal Incense. Royal Society of Chemistry: Chemistry World. January 15, 2009. Accessed: June 17, 2010

- ^ Kikura-Hanajiri, R.; Uchiyama, N.; Goda, Y. (2011). "Survey of current trends in the abuse of psychotropic substances and plants in Japan". Legal Medicine. 13 (3): 109–115. doi:10.1016/j.legalmed.2011.02.003. PMID 21377397.

- ^ Uchiyama, N.; Kawamura, M.; Kikura-Hanajiri, R.; Goda, Y. (2012). "URB-754: A new class of designer drug and 12 synthetic cannabinoids detected in illegal products". Forensic Science International. 227 (1–3): 21–32. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.08.047. PMID 23063179.

- ^ Uchiyama, N.; Matsuda, S.; Kawamura, M.; Kikura-Hanajiri, R.; Goda, Y. (2013). "Two new-type cannabimimetic quinolinyl carboxylates, QUPIC and QUCHIC, two new cannabimimetic carboxamide derivatives, ADB-FUBINACA and ADBICA, and five synthetic cannabinoids detected with a thiophene derivative α-PVT and an opioid receptor agonist AH-7921 identified in illegal products". Forensic Toxicology. 31: 223–240. doi:10.1007/s11419-013-0182-9.

- ^ Spice Report Archived September 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Psychonaut Web Mapping Research Project

- ^ "The story of Spice". Financial Times. February 13, 2009. Retrieved September 19, 2010.

- ^ Winstock, A.; Mitcheson, L.; Deluca, P.; Davey, Z.; Corazza, O.; Schifano, F. (2010). "Mephedrone, new kid for the chop?". Addiction (Abingdon, England). 106 (1): 154–161. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03130.x. PMID 20735367.

- ^ Ärzteblatt, Deutscher Ärzteverlag GmbH, Redaktion Deutsches. "Withdrawal Phenomena and Dependence Syndrome After the Consumption of „Spice Gold" (03.07.2009)" (in German). doi:10.3238/arztebl.2009.0464. PMC 2719097. PMID 19652769.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Auwärter, Volker; Dresen, Sebastian; Weinmann, Wolfgang; Müller, Michael; Pütz, Michael; Ferreirós, Nerea (2009). "'Spice' and other herbal blends: harmless incense or cannabinoid designer drugs?". Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 44 (5): 832–837. doi:10.1002/jms.1558. ISSN 1076-5174.

- ^ Milone, Michael C. (2012). Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. Elsevier. pp. 49–73. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-385467-4.00003-8. ISBN 9780123854674.

- ^ Znaleziona, Joanna; Ginterová, Pavlína; Petr, Jan; Ondra, Peter; Válka, Ivo; Ševčík, Juraj; Chrastina, Jan; Maier, Vítězslav (2015). "Determination and identification of synthetic cannabinoids and their metabolites in different matrices by modern analytical techniques – a review". Analytica Chimica Acta. 874: 11–25. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2014.12.055. ISSN 0003-2670.

- ^ Spinelli, Eliani; Barnes, Allan J.; Young, Sheena; Castaneto, Marisol S.; Martin, Thomas M.; Klette, Kevin L.; Huestis, Marilyn A. (2014-08-29). "Performance characteristics of an ELISA screening assay for urinary synthetic cannabinoids". Drug Testing and Analysis. 7 (6): 467–474. doi:10.1002/dta.1702. ISSN 1942-7603.

- ^ Diao, X; Huestis, MA (2016-11-24). "Approaches, Challenges, and Advances in Metabolism of New Synthetic Cannabinoids and Identification of Optimal Urinary Marker Metabolites". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 101 (2): 239–253. doi:10.1002/cpt.534. ISSN 0009-9236.

- ^ Sobolevsky, Tim; Prasolov, Ilya; Rodchenkov, Grigory (2010). "Detection of JWH-018 metabolites in smoking mixture post-administration urine". Forensic Science International. 200 (1–3): 141–147. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.04.003. ISSN 0379-0738.

- ^ "Synthetic Cannabinoids - AACC.org". www.aacc.org. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ^ Huppertz, Laura M.; Kneisel, Stefan; Auwärter, Volker; Kempf, Jürgen (2014). "A comprehensive library-based, automated screening procedure for 46 synthetic cannabinoids in serum employing liquid chromatography-quadrupole ion trap mass spectrometry with high-temperature electrospray ionization". Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 49 (2): 117–127. doi:10.1002/jms.3328. ISSN 1076-5174.

- ^ Scheidweiler, Karl B.; Jarvis, Michael J. Y.; Huestis, Marilyn A. (2015-01-01). "Nontargeted SWATH acquisition for identifying 47 synthetic cannabinoid metabolites in human urine by liquid chromatography-high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry". Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 407 (3): 883–897. doi:10.1007/s00216-014-8118-8. ISSN 1618-2642.

- ^ 1944-, Baselt, Randall C. (Randall Clint),. Disposition of toxic drugs and chemicals in man (Tenth edition ed.). Seal Beach, California. ISBN 9780962652394. OCLC 883367655.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|last=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Determination and identification of synthetic cannabinoids and their metabolites in different matrices by modern analytical techniques – a review". Analytica Chimica Acta. 874: 11–25. 2015-05-18. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2014.12.055. ISSN 0003-2670.

- ^ m.b.H., STANDARD Verlagsgesellschaft. "Kräutermischung "Spice": Gesundheitsministerium stoppt Handel". derStandard.at. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ^ "AFP: Austria bans herbal incense 'Spice'". 2010-03-10. Retrieved 2018-05-04.