| Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leak | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Neurology |

Spontaneous Cerebrospinal Fluid Leak Syndrome (SCSFLS) is a medical condition in which the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) held in and around a human brain and spinal cord leaks out of the surrounding protective sac, the dura, for no apparent reason.[1][2] The dura is a tough, inflexible tissue which is the outermost of the three layers of the meninges, the system of membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord. The other two meningeal layers are the pia mater and the arachnoid mater.

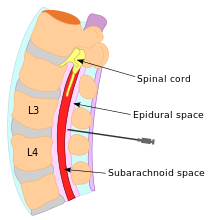

A spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leak is one of several types of cerebrospinal fluid leaks and occurs due to the presence of one or more holes in the spinal dura. A spontaneous CSF leak, as opposed to other forms of CSF leaks, arises idiopathically. The loss of CSF due to the leak leads to a decreased volume inside the skull known as intracranial hypotension. SCSFLS is characterized by a severe and disabling headache, dizziness, metallic taste in the mouth, and facial weakness. A CT scan can identify the site of a cerebrospinal fluid leakage. Once identified, the leak can often be repaired by an epidural blood patch, an injection of the patient's own blood at the site of the leak.[3][4]

SCSFLS afflicts 5 out of every 100,000 people. On average, the condition is developed at the age of 42 with women being twice as likely than men to develop the condition. Some people with SCSFLS chronically leak cerebrospinal fluid despite repeated attempts at patching, leading to long-term disability due to pain and nerve damage.

Classification

SCSFLS is classified as two main types, cranial leaks[5] and spinal leaks.[6] Cranial leaks occur in the head. In some cases, CSF can be seen dripping out of the nose[5] or ear.[5] Spinal leaks occur when one or more holes form in the dura along the spinal cord.[6] Both cranial and spinal spontaneous CSF leaks cause neurological symptoms as well as Spontaneous Intracranial Hypotension, diminished volume and pressure of the cranium.[1] For this reason, the SCSFLS is referred to as CSF hypovolemia as opposed to CSF hypotension.[7][8]Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page).

Signs and symptoms

| Nerve | Function | Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| vestibulocochlear (8) |

hearing, balance |

hearing and balance problems |

| optic (2) |

optic nerve crossing |

blurred vision |

| facial (7) |

facial nerve | facial weakness and numbness |

| chorda tympani (Branch of 7) |

taste | taste distortion |

| glossopharyngeal (9) |

taste | taste distortion |

Symptoms of cerebrospinal fluid leaks include an orthostatic headache[10] in which the pain is worse when the patient is vertical and better when horizontal, severe dizziness and vertigo, facial numbness or weakness, double vision, a metallic taste in the mouth, nausea, and vomiting.[2] Leaking CSF can can sometimes be observed exiting through the nose or ear.[11] Orthostatic headaches can be incapacitating [12] and disabling;[13] these symptoms can sufficiently debilitating to cause those afflicted to be unable to work.[13]

Lack of CSF pressure and volume allows the brain to descend through the foramen magnum, or occipital bone, the large opening at the base of the skull. The lower portion of the brain is believed to stretch or impact one or more nerve complexes, thereby causing a variety of sensory symptoms. Nerve complexes that can be affected and their related symptoms are detailed in the table at right.

Causes

A spontaneous CSF leak is idiopathic; it can arise spontaneously or from an unknown cause. Various scientists and physicians have suggested that this condition may be the result of an underlying connective tissue disorder affecting the spinal dura.[14][15][2][16] Some other studies have proposed that issues with the spinal venous drainage system may cause a CSF leak.[17] According to this theory, dural holes and intracranial hypotension are symptoms caused by low pressure in the epidural space due to outflow to the heart through the inferior vena cava vein.[17]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of a cerebrospinal fluid leak is performed through a combination of measurement of the CSF pressure and a scan of the spinal column for fluid leak by use of a computed tomography myelogram (CTM). The opening fluid pressure in the spinal canal is obtained by performing a lumbar puncture, also known as a spinal tap. Once the pressure is measured, radioactive contrast material is injected into the spinal fluid. The contrast then diffuses out through dura sac. Once diffused, the contrast leaks through dural holes. This allows for a CTM with fluoroscopy to locate and image any sites of dura rupture via contrast seen outside the dura sac in the imagery.[18]

Magnetic resonance imaging is historically less effective at directly imaging sites of CSF leak. MRI studies may show pachymeningeal enhancement (when the dura mater looks thick and inflammed) and an Arnold-Chiari malformation, but this may not be seen in every case. An Arnold-Chiari malformation occurs when the brain sags and has a downward displacement. This is due to the decreased volume of cerebrospinal fluid in which the brain floats. MRIs can be completely normal, however, and are not the study of choice.[14] In addition, in 18–46% of cases, the CSF pressure is measured as being in the normal range.[19][7] An alternate method of locating the site of a CSF leak is to use heavily T2-weighted MR myelography. This has been shown to be effective in identifying the sites of a CSF leak without the need for a CT scan, lumbar puncture, and contrast.[20] This type of MRI is effective at locating fluid collections such as CSF pooling. [20] MRIs done on patients sitting upright compared to those laying down demonstrated no difference in MRI results. [21]

When cranial CSF leak is suspected, due to discharge of fluid from the nose or ear that is potentially CSF, fluid can be collected and then tested with a beta-2 transferrin assay.[22] This test can positively identify if the fluid is cerebrospinal fluid.[22]

Up to 94% of those suffering from SCSFLS are initially misdiagnosed.[23] Incorrect diagnoses include migraines, meningitis, and psychiatric disorders.[23] The average time from onset of symptoms until definitive diagnosis is 13 months.[23]

Treatment

The treatment of choice for this condition is the surgical application of epidural blood patches,[12][24][12][25] which has a 90% success rate in treating dural holes,[26] higher than the conservative treatment of bed rest and hydration.[27] Through the injection of a person's own blood into the area of the hole in the dura, an epidural blood patch uses blood's clotting factors to clot the sites of holes. The volume of autologous blood and number of patch attempts for patients is highly variable.[12] If blood patches alone do not succeed in closing the dural tears, fibrin glue can be added and mixed into the autologous blood patch during a repeat treatment. This has been demonstrated to raise the level of effectiveness of forming a clot and arresting CSF leakage.[6]

In extreme cases of intractable CSF leak, a surgical lumbar drain has been used.[28][29][30] This procedure is believed to decrease spinal CSF volume while increasing intracranial CSF pressure and volume.[28] This procedure restores normal intracranial CSF volume and pressure while promoting the healing of dural tears by lowering the pressure and volume in the dura.[28][30] This procedure has led to positive results leading to relief of symptoms for up to one year.[28][29]

Research & experimental treatments

IV Cosyntropin has been used to treat CSF leaks.[31] Cosyntropin is a corticosteroid that causes the brain to produce additional spinal fluid to replace the volume of the lost CSF and alleviate symptoms.[31]

In a small study of two patients who suffered from recurrent CSF leaks where repeated blood patches failed to form clots and relieve symptoms, the patients received complete resolution of symptoms with an epidural saline infusion.[32]

Prognosis

Final outcomes for people with SCSFLS remain poorly studied.[9] Some of those afflicted continue to leak CSF from one or more sites and may suffer from unremitting symptoms for many years.[33] People with chronic SCSFLS may be disabled and unable to work.[13]

Complications

Several complications can occur as a result of SCSFLS, including decreased cranial pressure, brain herniation, infection, blood pressure problems, transient paralysis, and development of a coma.

The primary and most serious complication of SCSFLS is Spontaneous Intracranial Hypotension, where pressure in the brain is severely decreased. [34] This complication leads to the hallmark symptom of severe orthostatic headaches.[34]

People with cranial CSF leaks have a higher chance of developing meningitis than those with spinal CSF leaks.[22] If cranial leaks last more than seven days, the chances of developing meningitis are significantly higher.[22] Those with spinal CSF leaks do not usually develop meningitis due to the mostly aseptic conditions of the spinal dura. [22]

Orthostatic hypotension is another complication which occurs due to autonomic dysfunction when blood pressure drops significantly.[33] The autonomic dysfunction is caused by compression of the brain stem, the part of the brain that controls breathing and circulation.[33]

An Arnold-Chiari malformation is a downward displacement of lower parts of the brain through the skull opening that occurs due to a lack of CSF volume and pressure. A further, albeit rare complication of CSF leak is transient quadriplegia due to a sudden and significant loss of CSF. This loss results in hindbrain herniation and causes major compression of the upper cervical spinal cord. The quadriplegia dissipates once the patient lays supine.[35] An extremely rare complication of SCSFLS is third nerve palsy, where the ability to move one's eyes becomes difficult and interrupted due to compression of the third cranial nerve. [36]

There are documented cases of reversible dementia and coma.[19] Coma due to CSF leak has been successfully treated by using blood patches and placing the patient in the Trendelenburg position.[37]

Pathophysiology

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is produced by the brain by the choroid plexus. The brain floats in CSF and transports nutrients to the brain and spinal cord. CSF is held in by the dura mater.[38] As holes form in the spinal dura mater, CSF leaks out into the surrounding space. The CSF is then absorbed into the spinal epidural venous plexus or soft tissues around the spine.[39]

Epidemiology

A 1994 community-based study indicated that two out of every 100,000 people suffered from SCSFLS, while a 2004 emergency room-based study indicated five per 100,000.[40] SCSFLS generally affects the young and middle aged;[28] the average age for onset is 42.3 years, but onset can range from ages 22 to 61.[1] In an 11-year study, from 1992 to 2003, of patients with SCSFLS, women were found to be twice as likely to be affected as men.[41]

Studies have shown that SCSFLS runs in families.[42] It is suspected that genetic similarity in families includes weakness in the dura mater which leads to SCSFLS.[42]

History

Spontaneous CSF leaks have been described by notable physicians and reported in medical journals dating back to the early 1900s. Among them were George Schaltenbrand, Henry Woltman of the Mayo Clinic, and a French medical journal.[43][44] German neurologist Dr. George Schaltenbrand reported in 1938 and 1953 what he termed "aliquorrhea", a condition marked by very low, unobtainable, or even negative CSF pressures. The symptoms included orthostatic headaches and other features that are now recognized as spontaneous intracranial hypotension. A few decades earlier, the same syndrome had been described in French literature as "hypotension of spinal fluid" and "ventricular collapse". In 1940, Dr Henry Woltman wrote about "headaches associated with decreased intracranial pressure". The full clinical manifestations of intracranial hypotension and CSF leaks were described in several publications reported between the 1960s and early 1990s.[44]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16859268, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16859268instead. Cite error: The named reference "Surgical treatment of spontaneous spinal cerebrospinal fluid leaks." was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16859269, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16859269instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15549566, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15549566instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19199465, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19199465instead. - ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18710972, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18710972instead. Cite error: The named reference "Imaging of skull base cerebrospinal fluid leaks in adults." was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19909307, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19909307instead. - ^ a b Greenberg, Mark (2006). Handbook of neurosurgery. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers. p. 178. ISBN 0865779090. Retrieved 18 December 2009.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Walsh & Hoyt (2005). Walsh and Hoyt's clinical neuro-ophthalmology, Volume 3. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins. p. 1303. ISBN 0683060236. Retrieved 18 December 2009.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19037970, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19037970instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19012477, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19012477instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19636501, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19636501instead. - ^ a b c d Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19495908, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19495908instead. - ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19415418, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19415418instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19037970, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19037970instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11889250, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=11889250instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 14683542, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=14683542instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19591547, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19591547instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19636501, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19636501instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19378725, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19378725instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19949036, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19949036instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17927653, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17927653instead. - ^ a b c d e Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17767107, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17767107instead. - ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 14676045, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=14676045instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18380287, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18380287instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15549523, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15549523instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18464211, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18464211instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18809524, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18809524instead. - ^ a b c d e Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19473279, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19473279instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 2760094, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=2760094instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19863649, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19863649instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 10638928, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=10638928instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19010507, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19010507instead. - ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17214923, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17214923instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11309218, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=11309218instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16769965, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16769965instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18726726, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18726726instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19577356, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19577356instead. - ^ Schuenke, Michael (2007). Head and neuroanatomy. New York, NY: Thieme. p. 194. ISBN 3131421010. Retrieved 21 December 2009.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16934734, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16934734instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16705110, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16705110instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15549566, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15549566instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19921558, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19921558instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 13036182, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=13036182instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16859267, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16859267instead.