Thelostone41 (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tags: Reverted Visual edit |

Thelostone41 (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tags: Reverted Visual edit |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

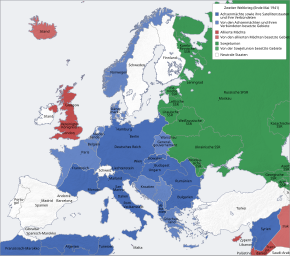

{{under construction}}[[File:Second World War Europe 05 1941 de.svg|thumb|upright=1.3|Division of Europe in May 1941]] |

{{under construction}}[[File:Second World War Europe 05 1941 de.svg|thumb|upright=1.3|Division of Europe in May 1941]] |

||

The '''Soviet offensive plans controversy''' was a debate by historians on whether Soviet Premier [[Joseph Stalin]] had planned to attack the [[Axis Powers|Axis forces]] in [[Eastern Europe]] before [[Operation Barbarossa]], the Axis invasion of the [[Soviet Union]]. Most historians agree that the [[geopolitical]] differences between the Soviets and the Axis made war inevitable, Stalin had made extensive preparations for war and he exploited the military conflict in Europe to his advantage. |

|||

[[Viktor Suvorov]] argued that Stalin had planned to attack Hitler while Germany was fighting the Allies, which would make Operation Barbarossa a [[pre-emptive strike]] by Hitler. Many historians have written in response to Suvorov, such as [[Gabriel Gorodetsky]] and [[David Glantz]], against those claims.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Evan Mawdsley. Crossing the Rubicon: Soviet Plans for Offensive War in 1940-1941. The International History Review, Vol. 25, No. 4 (Dec., 2003), pp. 818-865.}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|title=A. L. Weeks, Stalin's Other War: Soviet Grand Strategy, 1939-41 (Lanham, 2002), pp. 2-3.}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|title=Glantz, David M., Stumbling Colossus: The Red Army on the Eve of War, Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1998, ISBN 0-7006-0879-6 p. 4.}}</ref> |

|||

However, Suvorov received some support from [[Valeri Danilov]], [[Joachim Hoffmann]], [[Mikhail Meltyukhov]], and [[Vladimir Nevezhin]].<ref>{{Cite book|title=Bar-Joseph, Uri; Levy, Jack S. (Fall 2009). "Conscious Action and Intelligence Failure". Political Science Quarterly. 124 (3): 476}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|title=Uldricks, Teddy (Autumn 1999). "The Icebreaker Controversy: Did Stalin Plan to Attack Hitler?". Slavic Review. 58}}</ref> |

|||

== Background to the Soviet offensive plans controversy == |

== Background to the Soviet offensive plans controversy == |

||

Historians |

Historians have debated whether Stalin was planning an invasion of German territory in the summer of 1941. The debate began in the late-1980s when [[Viktor Suvorov]] published a journal article and later the book ''[[Icebreaker (Suvorov)|Icebreaker]]'' in which he claimed that Stalin had seen the outbreak of war in Western Europe as an opportunity to spread communist revolutions throughout the continent, and that the Soviet military was being deployed for an imminent attack at the time of the German invasion<ref>{{Cite journal|last=|first=|date=|title=Uldricks, Teddy (Autumn 1999). "The Icebreaker Controversy: Did Stalin Plan to Attack Hitler?". Slavic Review. 58 (3): 626–643. doi:10.2307/2697571. JSTOR 2697571|url=|journal=|volume=|pages=|via=}}</ref>This view had also been advanced by former German generals following the war<ref>{{Cite book|last=|first=|title=Smelser, Ronald; Davies, Edward J. (2008). The Myth of the Eastern Front: The Nazi-Soviet War in American Popular Culture (Paperback ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521712316.|publisher=|year=|isbn=|location=|pages=}}</ref>Suvorov's thesis was fully or partially accepted by a limited number of historians, including [[Valeri Danilov]], [[Joachim Hoffmann]], [[Mikhail Meltyukhov]], and [[Vladimir Nevezhin]], and attracted public attention in Germany, Israel, and Russia<ref>{{Cite book|last=|first=|title=Uldricks, Teddy (Autumn 1999). "The Icebreaker Controversy: Did Stalin Plan to Attack Hitler?". Slavic Review. 58 (3): 626–643. doi:10.2307/2697571. JSTOR 2697571.|publisher=|year=|isbn=|location=|pages=}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=|first=|date=|title=Bar-Joseph, Uri; Levy, Jack S. (Fall 2009). "Conscious Action and Intelligence Failure". Political Science Quarterly. 124 (3): 461–488. doi:10.1002/j.1538-165X.2009.tb00656.x|url=|journal=|volume=|pages=|via=}}</ref>It has been strongly rejected by most historians<ref>{{Cite journal|last=|first=|date=|title=Uldricks, Teddy (Autumn 1999). "The Icebreaker Controversy: Did Stalin Plan to Attack Hitler?". Slavic Review. 58 (3): 626–643. doi:10.2307/2697571. JSTOR 2697571.|url=|journal=|volume=|pages=|via=}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=|first=|date=|title=Humpert, David (2005). "Viktor Suvorov and Operation Barbarossa: Tukhachevskii Revisited". Journal of Slavic Military Studies. 18 (1): 59–74. doi:10.1080/13518040590914136.|url=|journal=|volume=|pages=|via=}}</ref>and ''Icebreaker'' is generally considered to be an "anti-Soviet tract" in Western countries<ref>{{Cite journal|last=|first=|date=|title=Roberts, Cynthia (1995). "Planning for War: The Red Army and the Catastrophe of 1941". Europe-Asia Studies. 47 (8): 1293–1326. doi:10.1080/09668139508412322.|url=|journal=|volume=|pages=|via=}}</ref>[[David Glantz]] and [[Gabriel Gorodetsky]] wrote books to rebut Suvorov's arguments.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=|first=|date=|title=Mawdsley, Evan (2003). "Crossing the Rubicon: Soviet Plans for Offensive War in 1940–1941". The International History Review. 25 (4): 818–865. doi:10.1080/07075332.2003.9641015. ISSN 1618-4866.|url=|journal=|volume=|pages=|via=}}</ref>The majority of historians believe that Stalin was seeking to avoid war in 1941, as he believed that his military was not ready to fight the German forces<ref>{{Cite journal|last=|first=|date=|title=Bar-Joseph, Uri; Levy, Jack S. (Fall 2009). "Conscious Action and Intelligence Failure". Political Science Quarterly. 124 (3): 461–488. doi:10.1002/j.1538-165X.2009.tb00656.x|url=|journal=|volume=|pages=|via=}}</ref> |

||

== Criticism and Support of the controversy == |

== Criticism and Support of the controversy == |

||

In some countries, particularly in [[Russia]], [[Germany]], and [[Israel]], Suvorov's thesis has jumped the bonds of academic discourse and captured the imagination of the public.<ref name="undricks">Teddy J. Uldricks. The Icebreaker Controversy: Did Stalin Plan to Attack Hitler? ''Slavic Review'', Vol. 58, No. 3 (Autumn, 1999), pp. 626-643</ref> Among the noted critics of Suvorov's work are the Israeli historian [[Gabriel Gorodetsky]]; the American military historian [[David Glantz]];<ref>David M. Glantz (Source: The Journal of Military History, Vol. 55, No. 2 (Apr., 1991), pp. 263-264</ref> the Russian military historians [[Makhmut Gareev]], Lev Bezymensky, and (perhaps most vehemently) Alexei Isayev,<ref>''See'' [[:ru:Исаев, Алексей Валерьевич|Alexei Isayev]] at Russian Language Wikipedia {{in lang|ru}}</ref> the author of ''Anti-Suvorov''. |

|||

In some countries, particularly in [[Russia]], [[Germany]], and [[Israel]], Suvorov's thesis has jumped the bonds of academic discourse and captured the imagination of the public.<ref name="undricks"/> Among the noted critics of Suvorov's work are the Israeli historian [[Gabriel Gorodetsky]]; the American military historian [[David Glantz]];<ref>David M. Glantz (Source: The Journal of Military History, Vol. 55, No. 2 (Apr., 1991), pp. 263-264</ref> the Russian military historians [[Makhmut Gareev]], Lev Bezymensky, and (perhaps most vehemently) Alexei Isayev,<ref>''See'' [[:ru:Исаев, Алексей Валерьевич|Alexei Isayev]] at Russian Language Wikipedia {{in lang|ru}}</ref> the author of ''Anti-Suvorov''. |

|||

According to Glantz, most agree that Stalin made extensive preparations for an eventual war and that he exploited the military conflict in Europe to his advantage, but Suvorov's assertions that Stalin planned to attack Germany in the summer of 1941, after a preemptive strike had been made by Hitler, are generally discounted.<ref name="Glantz, David M. 1998, p. 4">Glantz, David M., ''Stumbling Colossus: The Red Army on the Eve of War'', Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1998, {{ISBN|0-7006-0879-6}} p. 4.</ref> |

According to Glantz, most agree that Stalin made extensive preparations for an eventual war and that he exploited the military conflict in Europe to his advantage, but Suvorov's assertions that Stalin planned to attack Germany in the summer of 1941, after a preemptive strike had been made by Hitler, are generally discounted.<ref name="Glantz, David M. 1998, p. 4">Glantz, David M., ''Stumbling Colossus: The Red Army on the Eve of War'', Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1998, {{ISBN|0-7006-0879-6}} p. 4.</ref> |

||

| Line 96: | Line 89: | ||

One view was expressed by [[Mikhail Meltyukhov]] in his study ''[[Stalin's Missed Chance]]''.<ref>Meltyukhov</ref> He states that the idea for striking Germany arose long before May 1941 and was the very basis of Soviet military planning from 1940 to 1941. Providing additional support, no significant defense plan has been found.<ref>Meltyukhov 2000:375</ref> Meltyukhov covers five different versions of the assault plan ("Considerations on the Strategical Deployment of Soviet Troops in Case of War with Germany and its Allies" [https://web.archive.org/web/20071029171948/http://osteuropa.bsb-muenchen.de/dig/1000doktest/0024_zuk/@Generic__BookTextView/502;cs=default;ts=default;pt=502 (Russian original)]), the first version of which was developed soon after the outbreak of the Second World War. The last version was to be completed by May 1, 1941.<ref>Meltyukhov 2000:370–372</ref> Even the deployment of troops was chosen to be in the south, which would have been more beneficial for a Soviet assault.<ref>Meltyukhov 2000:381</ref> |

One view was expressed by [[Mikhail Meltyukhov]] in his study ''[[Stalin's Missed Chance]]''.<ref>Meltyukhov</ref> He states that the idea for striking Germany arose long before May 1941 and was the very basis of Soviet military planning from 1940 to 1941. Providing additional support, no significant defense plan has been found.<ref>Meltyukhov 2000:375</ref> Meltyukhov covers five different versions of the assault plan ("Considerations on the Strategical Deployment of Soviet Troops in Case of War with Germany and its Allies" [https://web.archive.org/web/20071029171948/http://osteuropa.bsb-muenchen.de/dig/1000doktest/0024_zuk/@Generic__BookTextView/502;cs=default;ts=default;pt=502 (Russian original)]), the first version of which was developed soon after the outbreak of the Second World War. The last version was to be completed by May 1, 1941.<ref>Meltyukhov 2000:370–372</ref> Even the deployment of troops was chosen to be in the south, which would have been more beneficial for a Soviet assault.<ref>Meltyukhov 2000:381</ref> |

||

[[Mark Solonin]] noted that several variants of a war plan against Germany had existed at least since August 1940. He argued that the Russian archives have five versions of the general plan for the strategic deployment of the Red Army and ten documents reflecting the development of plans for operational deployment of western military districts. The differences between them were slight, and all documents, including operational maps signed by the Deputy Chief of General Staff of the Red Army, were plans for the invasion with a depth offensive of 300 km. Solonin also stated that no other plans for a Red Army deployment in 1941 have been found,<ref>[http://www.solonin.org/en/article_comrade-stalins-three-plans Comrade Stalin's Three Plans -Mark Solonin's article on his personal website]</ref> and the concentration of Red Army units in West of the Soviet Union was done in direct accordance with the May "Considerations on the Plan for Strategic Deployment": |

|||

'''Planned and Actual Red Army Deployment on the Soviet Western Border''' |

|||

{|class="wikitable" |

|||

! |

|||

!"Considerations", May 41 |

|||

! "Reference", June 13 |

|||

! Actual confinement as of June 22, 1941 |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[Northern Front (Soviet Union)|Northern Front]] || Three armies, 21 / 4 / 2 || ------ 22 / 4 / 2 || 14th, 7th, 23rd Armies, 21 / 4 / 2 |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[North-Western Front]] || Three armies, 23 / 4 / 2 || ------ 23 / 4 / 2 || 27th, 8th, 11th Armies, 25 / 4 / 2 |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[Western Front (Soviet Union)|Western Front]] || Four armies, 45 / 8 / 4 || ------ 44 / 12 / 6 || 3rd, 10th, 4th, 13th Armies, 44 / 12 / 6 |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[Soviet Southwestern Front|South-Western Front]] and [[Southern Front (Soviet Union)|Southern Front]] || Eight armies,122 / 28 / 15 || ------ 100 / 20 / 10 || 5th, 6th, 26th, 12th, 18th, 9th Armies, |

|||

80 / 20 / 10 |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[Stavka]] reserve |

|||

|| five armies, 47 / 12 / 8 || five armies, 51/ 11 / 5 || 22nd, 20th, 21st, 19th, 16th, 24th, 28th Armies, 77 / 5 / 2 |

|||

|} |

|||

Notes: first digit – total number of divisions; second digit – tank divisions; third – motorized divisions<ref>On June 21, armies expanded in the Southern Theatre of Military Operations and were divided into two fronts: Southwestern and Southern. The table contains the total number of divisions in the two Fronts and in the Crimea.</ref> |

|||

According to the Plan of Cover, after the start of combat actions, two divisions of the Northwestern Front, expanded in Estonia, were transferred to the Northern Front.<ref>[[Mark Solonin]] (2010) (in Polish). 23 czerwca Dzień M (1 ed.). Poznań, Poland: Dom Wydawniczy Rebis. pp. 204. {{ISBN|978-83-7510-257-4}}. The table is available online on [http://www.solonin.org/en/book_june-23-m-day Mark Solonin's website]</ref> |

|||

In ''Stalin's War of Extermination'', [[Joachim Hoffmann]] made extensive use of interrogations of Soviet prisoners-of-war, ranging in rank from general to private, conducted by their German captors during the war. The book is also based on open-source, unclassified literature, and recently-declassified materials. Hoffmann argues from them that the Soviet Union had been making final preparations for its own attack when the Wehrmacht struck. Danilov and [[Heinz Magenheimer]] examined this plan and other documents in the early 1990s, which might indicate Soviet preparations for an attack. Both researchers came to the conclusion that Zhukov's plan on May 15, 1941 reflected [[Stalin's alleged speech of 19 August 1939]] that heralded the birth of the new offensive Red Army.<ref>''Austrian military journal'' (''Österreichische Militärische Zeitschrift'', nos. 5 and 6, 1991; no. 1, 1993; and no. 1, 1994).</ref> |

|||

Several politicians have also made claims similar to Suvorov's. On August 20, 2004, the historian and former [[Estonian President]] [[Mart Laar]] published an article in ''[[The Wall Street Journal]]'', ''When Will Russia Say 'Sorry'?': "The new evidence shows that by encouraging Hitler to start World War II, Stalin hoped to simultaneously ignite a world-wide revolution and conquer all of Europe". Another former statesman to share those views of a purported Soviet aggressive plan is the former [[Finnish President]] [[Mauno Koivisto]]: "It seems to be clear the Soviet Union was not ready for defense in the summer of 1941, but it was rather preparing for an assault.... The forces mobilized in the Soviet Union were not positioned for defensive, but for offensive aims". He concluded, "Hitler's invasion forces didn't outnumber [the Soviets], but were rather outnumbered themselves. The Soviets were unable to organize defenses. The troops were provided with maps that covered territories outside the Soviet Union".<ref name="koivisto">Koivisto, M. ''Venäjän idea'', Helsinki. Tammi. 2001</ref> |

Several politicians have also made claims similar to Suvorov's. On August 20, 2004, the historian and former [[Estonian President]] [[Mart Laar]] published an article in ''[[The Wall Street Journal]]'', ''When Will Russia Say 'Sorry'?': "The new evidence shows that by encouraging Hitler to start World War II, Stalin hoped to simultaneously ignite a world-wide revolution and conquer all of Europe". Another former statesman to share those views of a purported Soviet aggressive plan is the former [[Finnish President]] [[Mauno Koivisto]]: "It seems to be clear the Soviet Union was not ready for defense in the summer of 1941, but it was rather preparing for an assault.... The forces mobilized in the Soviet Union were not positioned for defensive, but for offensive aims". He concluded, "Hitler's invasion forces didn't outnumber [the Soviets], but were rather outnumbered themselves. The Soviets were unable to organize defenses. The troops were provided with maps that covered territories outside the Soviet Union".<ref name="koivisto">Koivisto, M. ''Venäjän idea'', Helsinki. Tammi. 2001</ref> |

||

Revision as of 03:31, 12 February 2021

Background to the Soviet offensive plans controversy

Historians have debated whether Stalin was planning an invasion of German territory in the summer of 1941. The debate began in the late-1980s when Viktor Suvorov published a journal article and later the book Icebreaker in which he claimed that Stalin had seen the outbreak of war in Western Europe as an opportunity to spread communist revolutions throughout the continent, and that the Soviet military was being deployed for an imminent attack at the time of the German invasion[1]This view had also been advanced by former German generals following the war[2]Suvorov's thesis was fully or partially accepted by a limited number of historians, including Valeri Danilov, Joachim Hoffmann, Mikhail Meltyukhov, and Vladimir Nevezhin, and attracted public attention in Germany, Israel, and Russia[3][4]It has been strongly rejected by most historians[5][6]and Icebreaker is generally considered to be an "anti-Soviet tract" in Western countries[7]David Glantz and Gabriel Gorodetsky wrote books to rebut Suvorov's arguments.[8]The majority of historians believe that Stalin was seeking to avoid war in 1941, as he believed that his military was not ready to fight the German forces[9]

Criticism and Support of the controversy

In some countries, particularly in Russia, Germany, and Israel, Suvorov's thesis has jumped the bonds of academic discourse and captured the imagination of the public.[10] Among the noted critics of Suvorov's work are the Israeli historian Gabriel Gorodetsky; the American military historian David Glantz;[11] the Russian military historians Makhmut Gareev, Lev Bezymensky, and (perhaps most vehemently) Alexei Isayev,[12] the author of Anti-Suvorov.

According to Glantz, most agree that Stalin made extensive preparations for an eventual war and that he exploited the military conflict in Europe to his advantage, but Suvorov's assertions that Stalin planned to attack Germany in the summer of 1941, after a preemptive strike had been made by Hitler, are generally discounted.[13]

Many other western scholars, such as Teddy J. Uldricks,[10] Derek Watson,[14] Hugh Ragsdale,[15] Roger Reese,[16][17] Stephen Blank,[18] Robin Edmonds,[19] agree that most Suvorov's writings rest on circumstantial evidence[20] or even "virtually no evidentiary base".[10][21] Jonathan Haslam[22] "would be comical were it not taken so seriously".[23] and Alexander Nekrich also disagreed with Suvorov.[24]

According to the review article by Christopher J. Kshyk, the debate on whether Stalin intended to launch offensive against Germany in 1941 remains inconclusive but has produced an abundance of scholarly literature and helped to expand the understanding of larger themes in Soviet and world history during the interwar period. Kshyk also notes the problems because of the still-limited access to Soviet archives and the emotional nature of debate from national pride and the participants' political and personal motivations. Kshyk believe to be erroneous the notion that Stalin was preparing to launch an offensive against Germany in the summer of 1941.[25]

However, studies by some historians, such as the Russian military historian Mikhail Meltyukhov (Stalin's Missed Chance), gave partial support to the claim that Soviet forces were concentrating to attack Germany. Other historians who support that thesis are Vladimir Nevezhin, Boris Sokolov, Valeri Danilov and Joachim Hoffmann.[26] Offensive interpretations of Stalin's prewar planning are also supported by the Sovietologist Robert C. Tucker and by Pavel N. Bobylev.[27] Hoffmann argues that the actual Soviet troop concentrations, fuel depots and airfields were near the German-Soviet border in what was Poland. All of them are said to be unsuitable for defensive operations.[28]

| Germany | Soviet Union | Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Divisions | 128 | 174 | 1 : 1.4 |

| Personnel | 3,459 | 3,289 | 1.1 : 1 |

| Guns and mortars | 35,928 | 59,787 | 1 : 1.7 |

| Tanks (incl assault guns) | 3,769 | 15,687 | 1 : 4.2 |

| Aircraft | 3,425 | 10,743 | 1 : 3.1 |

Source: Mikhail Meltyukhov Stalin's Missed Chance table 43,45,46,47,[29]

Supporters of the theory also refer to various facts, such as the publication of Georgy Zhukov's proposal of May 15, 1941,[30] which called for a Soviet strike against Germany, to support their position. That document suggested a secret mobilisation and deployment of Red Army troops next to the western border under the cover of training.[31] However, Robin Edmonds argued that the Red Army's planning staff would not have been doing its job well if it had not considered the possibility of a preemptive strike against the Wehrmacht,[19] and Teddy J. Uldricks pointed out that no documentary evidence shows that Zhukov's proposal was ever accepted by Stalin.[10]

Another piece of evidence is Stalin's speech of 5 May 1941 to graduating military cadets.[32] He proclaimed: "A good defense signifies the need to attack. Attack is the best form of defense.... We must now conduct a peaceful, defensive policy with attack. Yes, defense with attack. We must now re-teach our army and commanders. Educate them in the spirit of attack".[33] However, according to Michael Jabara Carley, thar speech could be equally interpreted as a deliberate attempt to discourage the Germans from launching an invasion.[34]

Other Russian historians, Iu. Gor'kov, A.S. Orlov, Iu. A. Polyakov, and Dmitri Volkogonov, analyzed newly-available evidence to demonstrate that Soviet forces were certainly not ready for the attack.[10]

Colonel Dr. Pavel N. Bobylev[35] was one of the military historians from the Soviet (later Russian) Ministry of Defense who in 1993 published the materials of the January 1941 games on maps. More than 60 top Soviet officers for about ten days in January rehearsed the possible scenarios to begin a war against the Axiz. The materials show that no battles were played out on the Soviet soil. The action started only when the Soviets ("Easterners") attacked westward from their border and, in the second game ("South Variant"), even from positions deep inside the enemy's land.

Criticism

Among the noted critics of Suvorov's work are the Israeli historian Gabriel Gorodetsky; the American military historian David Glantz;[36] and the Russian military historians Makhmut Gareev, Lev Bezymensky, and Dmitri Volkogonov. Many other western scholars, such as Teddy J. Uldricks,[37] Derek Watson,[38] Hugh Ragsdale,[39] Roger Reese,[40] Stephen Blank,[41] and Robin Edmonds,[42] agree that the Suvorov's major weakness is "that the author does not reveal his sources" (Ingmar Oldberg)[43] and rely on circumstantial evidence.[44] The historian Cynthia A. Roberts is even more categorical and claims that Suvorov's writings have "virtually no evidentiary base".[45]

Suvorov's most controversial thesis was that the Red Army had made extensive preparations for an offensive war in Europe but was totally unprepared for defensive operations on its own territory.[10] He essentially reiterates the argument put forward by Hitler in 1941.[10] According to Jonathan Haslam, Suvorov's claim that "Germany frustrated Stalin's war"[22] "would be comical were it not taken so seriously".[46]

One of Suvorov's arguments was that certain types of weapons were mostly suited for offensive warfare and that the Red Army had large numbers of such weapons. For example, he pointed out that the Soviet Union was outfitting large numbers of paratroopers and actually prepared to field entire parachute armies, and he stated that paratroopers are suitable only for offensive action, which the Soviet military doctrine of the time recognised. Suvorov's critics say that the Soviet paratroopers were not well trained or armed.[47] Similarly, Suvorov cited the development of the KT/Antonov A-40 "flying tank" as evidence of Stalin's aggressive plans, but his critics say that development of that tank was started only in December 1941.[48]

David M. Glantz disputes the argument that the Red Army was deployed in an offensive stance in 1941 and states that the Red Army was in a state of only partial mobilization in July 1941 from which neither effective defensive or offensive actions could be offered without considerable delay.[49]

Antony Beevor wrote that "the Red Army was simply not in a state to launch a major offensive in the summer of 1941, and in any case Hitler's decision to invade had been made considerably earlier."[50] However, he also noted that "it cannot be excluded that Stalin... may have been considering a preventive attack in the winter of 1941 or more probably in 1942...".[50]

Paweł Wieczorkiewicz, the author of a detailed description of the purge in the Red Army (Łańcuch śmierci: czystka w Armii Czerwonej 1937-1939, 1335 pages) believed that the Red Army had not been prepared to fight in 1941 because of the recent purges of the Red Army and its modernisation projects.[51]

A Soviet emigre, the historian Alexandr Nekrich, who extremely critical of Stalin in other contexts, also rejected Suvorov's ideas as unsubstantiated and contrary to Stalin's broader policy.[52]

Roger R. Reese has said some of Suvorov's claims have been shown to simply be inaccurate such as his claim regarding Soviet conscription started only in 1939, but conscription had existed since 1925.[53]

David Brandenberger said that the recently-published German Intelligence analysis of Soviet military readiness before 1941 had concluded that Soviet preparations to be "defensive"[54]

Middle positions

In a 1987 article in the Historische Zeitschrift journal, the German historian Klaus Hildebrand argued that both Hitler and Stalin had separately planned to attack each other in 1941.[55] He considered that the news of Red Army concentrations near the border had led to Hitler engaging in a Flucht nach vorn ("flight forward"), a response to a danger by charging on, rather than retreating:[55] "Independently, the National Socialist program of conquest met the equally far-reaching war-aims program which Stalin had drawn up in 1940 at the latest".[55]

Support

Western researchers, two exceptions being Albert L. Weeks[56] and R. C. Raack,[57][58][59] criticised Suvorov's thesis,[60] but Suvorov has gathered some support among Russian historians since the 1990s as some archive materials were declassified. Authors the assault thesis are Valeri Danilov,[61] V.A. Nevezhin,[62] Constantine Pleshakov, Mark Solonin[63] and Boris Sokolov.[64] Although the Soviets attacked Finland, no document has been found to date to indicate either 26 November 1939 as the assumed date for the beginning of provocations or 30 November as the date of the planned Soviet assault.[65]

One view was expressed by Mikhail Meltyukhov in his study Stalin's Missed Chance.[66] He states that the idea for striking Germany arose long before May 1941 and was the very basis of Soviet military planning from 1940 to 1941. Providing additional support, no significant defense plan has been found.[67] Meltyukhov covers five different versions of the assault plan ("Considerations on the Strategical Deployment of Soviet Troops in Case of War with Germany and its Allies" (Russian original)), the first version of which was developed soon after the outbreak of the Second World War. The last version was to be completed by May 1, 1941.[68] Even the deployment of troops was chosen to be in the south, which would have been more beneficial for a Soviet assault.[69]

Several politicians have also made claims similar to Suvorov's. On August 20, 2004, the historian and former Estonian President Mart Laar published an article in The Wall Street Journal, When Will Russia Say 'Sorry'?': "The new evidence shows that by encouraging Hitler to start World War II, Stalin hoped to simultaneously ignite a world-wide revolution and conquer all of Europe". Another former statesman to share those views of a purported Soviet aggressive plan is the former Finnish President Mauno Koivisto: "It seems to be clear the Soviet Union was not ready for defense in the summer of 1941, but it was rather preparing for an assault.... The forces mobilized in the Soviet Union were not positioned for defensive, but for offensive aims". He concluded, "Hitler's invasion forces didn't outnumber [the Soviets], but were rather outnumbered themselves. The Soviets were unable to organize defenses. The troops were provided with maps that covered territories outside the Soviet Union".[70]

References

- ^ "Uldricks, Teddy (Autumn 1999). "The Icebreaker Controversy: Did Stalin Plan to Attack Hitler?". Slavic Review. 58 (3): 626–643. doi:10.2307/2697571. JSTOR 2697571".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Smelser, Ronald; Davies, Edward J. (2008). The Myth of the Eastern Front: The Nazi-Soviet War in American Popular Culture (Paperback ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521712316.

- ^ Uldricks, Teddy (Autumn 1999). "The Icebreaker Controversy: Did Stalin Plan to Attack Hitler?". Slavic Review. 58 (3): 626–643. doi:10.2307/2697571. JSTOR 2697571.

- ^ "Bar-Joseph, Uri; Levy, Jack S. (Fall 2009). "Conscious Action and Intelligence Failure". Political Science Quarterly. 124 (3): 461–488. doi:10.1002/j.1538-165X.2009.tb00656.x".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Uldricks, Teddy (Autumn 1999). "The Icebreaker Controversy: Did Stalin Plan to Attack Hitler?". Slavic Review. 58 (3): 626–643. doi:10.2307/2697571. JSTOR 2697571".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Humpert, David (2005). "Viktor Suvorov and Operation Barbarossa: Tukhachevskii Revisited". Journal of Slavic Military Studies. 18 (1): 59–74. doi:10.1080/13518040590914136".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Roberts, Cynthia (1995). "Planning for War: The Red Army and the Catastrophe of 1941". Europe-Asia Studies. 47 (8): 1293–1326. doi:10.1080/09668139508412322".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Mawdsley, Evan (2003). "Crossing the Rubicon: Soviet Plans for Offensive War in 1940–1941". The International History Review. 25 (4): 818–865. doi:10.1080/07075332.2003.9641015. ISSN 1618-4866".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Bar-Joseph, Uri; Levy, Jack S. (Fall 2009). "Conscious Action and Intelligence Failure". Political Science Quarterly. 124 (3): 461–488. doi:10.1002/j.1538-165X.2009.tb00656.x".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g Teddy J. Uldricks. The Icebreaker Controversy: Did Stalin Plan to Attack Hitler? Slavic Review, Vol. 58, No. 3 (Autumn, 1999), pp. 626-643

- ^ David M. Glantz (Source: The Journal of Military History, Vol. 55, No. 2 (Apr., 1991), pp. 263-264

- ^ See Alexei Isayev at Russian Language Wikipedia (in Russian)

- ^ Glantz, David M., Stumbling Colossus: The Red Army on the Eve of War, Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1998, ISBN 0-7006-0879-6 p. 4.

- ^ Source: Slavic Review, Vol. 59, No. 2 (Summer, 2000), pp. 492)

- ^ Hugh Ragsdale, Reviewed work(s): Grand Delusion: Stalin and the German Invasion of Russia by Gabriel Gorodetsky, Slavic Review, Vol. 59, No. 2 (Summer, 2000), pp. 466-467

- ^ Slavic Review, Vol. 59, No. 1 (Spring, 2000), p. 227

- ^ Roger R. Reese, Stalin's Reluctant Soldiers, University Press of Kansas, 1996. pp.9-15. ISBN 0-7006-0772-2.

- ^ Russian Review, Vol. 59, No. 2 (April 2000), pp. 310-311

- ^ a b Reviewed work(s): Icebreaker: Who Started the Second World War? by Viktor Suvorov ; Thomas B. Beattle. Source: International Affairs, Vol. 66, No. 4, Seventieth Anniversary Issue (October 1990), p. 812

- ^ Chris Bellamy. Absolute war. Soviet Russia in the Second World War. Vinage, 2007. ISBN 978-0-375-72471-8. p.103.

- ^ Cynthia A. Roberts. "Planning for War: The Red Army and the Catastrophe of 1941" Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 47, No. 8 (Dec., 1995), pp. 1293-1326

- ^ a b V. Suvorov, Icebreaker: Who Started the Second World War? (London, 1990) p. 325

- ^ Jonathan Haslam. Reviewed work(s): Stalin's Drive to the West, 1938-1945: The Origins of the Cold War. by R. Raack The Soviet Union and the Origins of the Second World War: Russo-German Relations and the Road to War, 1933-1941. by G. Roberts. The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 69, No. 4 (Dec., 1997), pp. 785-797

- ^ Aleksandr Moiseevich Nekrich, Adam Bruno Ulam, Gregory L. Freeze. Pariahs, Partners, Predators: German-Soviet Relations, 1922-1941. Columbia University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-231-10676-9, ISBN 978-0-231-10676-4, p. 233

- ^ "Did Stalin Plan to Attack Hitler in 1941? The Historiographical Controversy Surrounding the Origins of the Nazi-Soviet War".

- ^ Bellamy 2007, p. 115.

- ^ Weeks 2003, p. 103.

- ^ (Maser 1994: 376–378; Hoffmann 1999: 52–56)

- ^ Meltyukhov 2000, (electronic version). Since the Soviet archives were and sometiynes are inaccessible, exact figures in some cases have been difficult to ascertain. The official Soviet sources generally overestimated German strength and downplayed Soviet strength, as is emphasized by David Glantz (1998:292). Some of the earlier Soviet figures claimed that there had been only 1,540 Soviet aircraft to face Germany's 4,950 and there were merely 1,800 Red Army AFVs facing Germany's 2,800. In 1991, the Russian military historian Meltyukhov published an article on that question (Мельтюхов М.И. 22 июня 1941 г.: цифры свидетельствуют // История СССР. 1991. № 3), with figures that differed slightly from those of the table here but with similar ratios. Glantz (1998:293) believes that those figures seem "to be most accurate regarding Soviet forces and those of Germany's allies", but other figures also occur in modern publications.

- ^ Russian original Archived 2007-10-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Stalin: The First In-depth Biography Based on Explosive New Documents from Russia's Secret Archives, Anchor, (1997) ISBN 0-385-47954-9, pages 454-459

- ^ Robert Service, Stalin: A Biography, Macmillan, 2004 ISBN 978-0-330-41913-0, Chapter: The Devils Sup', Volkogonov Papers, reel no.8, p.1.

- ^ N. Lyashchenko, 'O vystuplenii I. V. Stalina v Kremle, 5 maya 1941', Volkogonov Papers, reel no.8, p.1.

- ^ Michael Jabara Carley. Review: Soviet Foreign Policy in the West, 1936-1941: A Review Article. Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 56, No. 7 (Nov., 2004), pp. 1081-1093

- ^ Бобылев П.Н. Репетиция катастрофы//Военно-исторический журнал. 1993. No. 7. С. 14—21; No. 8. С,28—35; Русский архив: Великая Отечественная. Т.12(1). М..1993. С,388—390; Бобылев П.Н. К какой войне готовился Генеральный штаб РККА в 1941 году//Отечественная история. 1995. № 5. С.3—20

- ^ David M. Glantz; Suvorov, Viktor (1991). "Icebreaker: Who Started the Second World War?". The Journal of Military History. 55 (2): 263–264. doi:10.2307/1985920. JSTOR 1985920.

- ^ Teddy J. Uldricks (1999). "The Icebreaker Controversy: Did Stalin Plan to Attack Hitler?". Slavic Review. 58 (3): 626–643. doi:10.2307/2697571. JSTOR 2697571. (Book Reviews).

- ^ Borneman, John (2000). "[no title]". Slavic Review. 59 (2): 492. doi:10.1017/S0037677900035087.

- ^ Hugh Ragsdale; Gorodetsky, Gabriel (2000). "Grand Delusion: Stalin and the German Invasion of Russia". Slavic Review. 59 (2): 466–467. doi:10.2307/2697094. JSTOR 2697094.

- ^ "Book Reviews". Slavic Review. 59 (1): 227. 2000.

- ^ "Book Reviews". Russian Review. 59 (2): 310–311. 2000. doi:10.1111/russ.2000.59.issue-2.

- ^ Source: International Affairs, Vol. 66, No. 4, Seventieth Anniversary Issue (Oct. 1990), p. 812

- ^ Ingmar Oldberg (1985). "Review: The USSR. Evil, Strong, and Dangerous? Reviewed work(s):The Threat: Inside the Soviet Military Machine by Andrew Cockburn, Inside the Soviet Army by Viktor Suvorov". Journal of Peace Research. 22 (3): 273–277. doi:10.1177/002234338502200308. JSTOR 423626.

- ^ Chris Bellamy. Absolute War. Vintage Books, 2008, ISBN 978-0-375-72471-8, p. 101-104.

- ^ Cynthia A. Roberts (1995). "Planning for War: The Red Army and the Catastrophe of 1941". Europe-Asia Studies. 47 (8): 1293–1326. doi:10.1080/09668139508412322. JSTOR 153299.

- ^ Jonathan Haslam (1997). "Soviet-German Relations and the Origins of the Second World War: The Jury Is Still Out". The Journal of Modern History. 69 (4): 785–797. doi:10.1086/245594.

- ^ Алексей Исаев. Вертикальный охват // Неправда Виктора Суворова. М.: Яуза, Эксмо, 2007, pp. 257–289

- ^ Василий Чобиток. Кое-что о волшебных танках // Неправда Виктора Суворова. (Something about magic tanks / lie of Victor Suvorov) Moscow: Яуза, Эксмо, 2007, pp. 136–137 (in Russian)

- ^ Stumbling Colossus:The Red Army on the Eve of World War, D.Glantz, preface p. xii-xiii

- ^ a b Beevor 2012, p. 188.

- ^ "Stalin był przekonany, że Hitler nie powtórzy błędu Napoleona". PolskieRadio.pl. Retrieved 2020-08-20.

- ^ Aleksandr Moiseevich Nekrich, Adam Bruno Ulam, Gregory L. Freeze. Pariahs, Partners, Predators: German-Soviet Relations, 1922-1941. Columbia University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-231-10676-9, ISBN 978-0-231-10676-4, p. 233.

- ^ Stalin's Reluctant Soldiers,. University Press of Kansas. 1996. pp. 9–15. ISBN 0-7006-0772-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "David Brandenberger. Reviewed work(s):Sekrety Gitlera na Stole u Stalina: Razvedka i Kontrrazvedka o Podgotovke Germanskoi Agressii Protiv SSSR, Mart-Iyun' 1941 g. Dokumenty iz Tsentral'nogo Arkhiva FSB. Source: Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 49, No. 4 (Jun., 1997), pp. 748–749"". Europe-Asia Studies.

- ^ a b c Evans, Richard In Hitler's shadow: West German historians and the attempt to escape from the Nazi past, New York, NY: Pantheon, 1989 p. 43 ISBN 0-394-57686-1

- ^ A. L. Weeks, Stalin's Other War: Soviet Grand Strategy, 1939-41 (Lanham, 2002), pp. 2-3.

- ^ Raack, R.C. (1996). "Stalin's Role in the Coming of World War II". World Affairs. 158 (4): 198–211. JSTOR 20672468. Archived from the original on 2011-07-09.

- ^ Raack, R.C. (1996). "Stalin's Role in the Coming of World War II: The International Debate Goes On". World Affairs. 159 (2): 47–54. JSTOR 20672480. Archived from the original on 2011-06-07.

- ^ Stalin's Drive to the West, 1938–1945: The Origins of the Cold War ISBN 978-0-8047-2415-9

- ^ According to Raack, arguments for the thesis "have not so far been systematically reported in, for example, the Journal of Slavic Military Studies. Indeed, one searches in vain in North America for a broad discussion of the issues of Soviet war planning". R. C. Raack [Review of] Unternehmen Barbarossa: Deutsche und Sowjetische Angriffsplane 1940/41 by Walter Post Die sowjetische Besatzungsmacht und das politische System der SBZ by Stefan Creuzberger Slavic Review. Vol. 57, No. 1 (Spring, 1998), pp. 213

- ^ Данилов.В.Д. Сталинская стратегия начала войны: планы и реальность—Другая война. 1939–1945 гг; or Danilоv V. "Hat der Generalsstab der Roten Armee einen Praventiveschlag gegen Deutschland vorbereitet?" Österreichische Militarische Zeitschrift. 1993. №1. S. 41–51

- ^ Невежин В.А. Синдром наступательной войны. Советская пропаганда в преддверии "священных боев", 1939–1941 гг. М., 1997; Речь Сталина 5 мая 1941 года и апология наступательной войны Archive index at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mark Solonin. June 22 (The Cask and the Hoops)

- ^ Соколов Б.В. Неизвестный Жуков: портрет без ретуши в зеркале эпохи. (online text); Соколов Б.В. Правда о Великой Отечественной войне (Сборник статей). — СПб.: Алетейя, 1999 (online text)

- ^ Собирался ли Сталин напасть на Гитлера?. Militera.lib.ru. Retrieved on 2011-04-26.

- ^ Meltyukhov

- ^ Meltyukhov 2000:375

- ^ Meltyukhov 2000:370–372

- ^ Meltyukhov 2000:381

- ^ Koivisto, M. Venäjän idea, Helsinki. Tammi. 2001

Sources

Books that believe in Soviet offensive plans

- Dębski, Sławomir. Między Berlinem a Moskwą: Stosunki niemiecko-sowieckie 1939–1941. Warsaw: Polski Instytut Spraw Międzynarodowych, 2003 (ISBN 83-918046-2-3).

- Reviewed by R.C. Raack in The Russian Review, 2004, Vol. 63, Issue 4, pp. 718–719.

- Edwards, James B. Hitler: Stalin's Stooge. San Diego, CA: Aventine Press, 2004 (ISBN 978-1593301446, paperback).

- Grzelak, Czesław. Armia Stalina 1939-1941: Zbrojne ramię polityki ZSRS. Warsaw: Oficyna Wydawnicza RYTM, 2010 (ISBN 978-83-7399-387-7)

- Maser, Werner Der Wortbruch. Hitler, Stalin und der Zweite Weltkrieg. Olzog, München 1994. ISBN 3-7892-8260-X

- Fälschung, Dichtung und Wahrheit über Hitler und Stalin, Olzog, München 2004. ISBN 3-7892-8134-4

- Pleshakov, Constantine. Stalin's Folly: The Tragic First Ten Days of World War Two on the Eastern Front. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2005 (ISBN 0-618-36701-2).

- Reviewed by Ron Laurenzo in The Washington Times, May 22, 2005.

- Reviewed by Robert Citino in World War II, Vol. 21, Issue 1. (2006), pp. 76–77.

- The series of books authored by Victor Suvorov about the outbreak of the Nazi-Soviet War

- Icebreaker (Ледокол) 1990, Hamish Hamilton Ltd., ISBN 0-241-12622-3

- Day "M" (День "М")

- Suicide. For what reason Hitler attacked the Soviet Union? (Самоубийство), Moscow, ACT, 2000, ISBN 5-17-003119-X

- Last Republic, ACT, 1997, ISBN 5-12-000367-2.

- Viktor Suvorov, The Chief Culprit: Stalin's Grand Design to Start World War II. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2008 (hardcover), ISBN 978-1-61251-268-6.

- The series of books supporting Suvorov The Truth by Viktor Suvorov - volumes 1,2,3

- Raack, R.C. "Did Stalin Plan a Drang Nach Westen?", World Affairs. Vol. 155, Issue 4. (Summer 1992), pp. 13–21.

- Preventive Wars?" [Review Essay of Pietrow-Ennker, Bianka, ed. Präventivkrieg? Der deutsche Angriff auf die Sowjetunion. 3d ed. Frankfurt-am-Main: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 2000. ISBN 3-596-14497-3; Mel'tiukhov, Mikhail. Upushchennyi shans Stalina: Sovetskii Soiuz i bor'ba za Evropu 1939–1941. Moscow: Veche, 2000. ISBN 5-7838-1196-3; Magenheimer, Heinz. Entscheidungskampf 1941: Sowjetische Kriegsvorbereitungen. Aufmarsch. Zusammenstoss. Bielefeld: Osning Verlag, 2000. ISBN 3-9806268-1-4] The Russian Review, 2004, Vol. 63, Issue 1, pp. 134–137.

- "Stalin's Role in the Coming of World War II: Opening the Closet Door on a Key Chapter of Recent History", World Affairs. Vol. 158, Issue 4, 1996, pp. 198–211.

- "Stalin's Role in the Coming of World War II: The International Debate Goes On", World Affairs. Vol. 159, Issue 2, 1996, pp. 47–54.

- Stalin's Drive to the West, 1938–1945: The Origins of the Cold War. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1995. (ISBN 0-8047-2415-6).

- "Stalin's Plans for World War Two Told by a High Comintern Source", The Historical Journal, Vol. 38, No. 4. (Dec., 1995), pp. 1031–1036.

- "Breakers on the Stalin Wave: Review Essay [of Murphy, David E. What Stalin Knew: The Enigma of Barbarossa. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005 (ISBN 0-300-10780-3); Pleshakov, Constantine. Stalin’s Folly: The Tragic First Ten Days of World War II on the Eastern Front. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin Co., 2005 (ISBN 0-618-36701-2)]", The Russian Review, Vol. 65, No. 3. (2006), pp. 512–515.

- Solonin, Mark. "23 июня: „День М" ("June 23 : M-Day") — Moscow: «Яуза», «Эксмо». 2007 ISBN 978-5-699-22304-6

- «25 июня. Глупость или агрессия?» ("June 25 : foolishness or aggression?") — Moscow: «Яуза», «Эксмо». 2008. ISBN 978-5-699-25300-5

- Topitsch, Ernst. Stalin's War: A Radical New Theory of the Origins of the Second World War. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1987 (ISBN 0-312-00989-5).

- Reviewed critically by Alexander Dallin in The New York Times, November 15, 1987.

- Weeks, Albert L. Stalin's Other War: Soviet Grand Strategy, 1939–1941. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002 (hardcover; ISBN 0-7425-2191-5); 2003 (paperback, ISBN 0-7425-2192-3).

Books that deny Soviet offensive plans

- Acton, Edward. "Understanding Stalin’s Catastrophe: [Review Article]", Journal of Contemporary History, 2001, Vol. 36(3), pp. 531–540.

- Carley, Michael Jabara. "Soviet Foreign Policy in the West, 1936–1941: A Review Article", Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 56, No. 7. (2004), pp. 1081–1100. [Review of Silvio Pons, Stalin and the Inevitable War, 1936–1941. London and Portland, OR: Frank Cass, 2002 and Albert L. Weeks, Stalin's Other War: Soviet Grand Strategy, 1939–1941. Oxford and Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002.]

- Erickson, John. "Barbarossa June 1941: Who Attacked Whom?" History Today, July 2001, Vol. 51, Issue 7, pp. 11–17.

- Edmonds, Robin. "[Review: Icebreaker: Who Started the Second World War?", International Affairs, Vol. 66, No. 4. (Oct., 1990), p. 812.

- Glantz, David M. Stumbling Colossus: The Red Army on the Eve of World War. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1998 (ISBN 0-7006-0879-6).

- Reviewed by David R. Costello in The Journal of Military History, Vol. 63, No. 1. (Jan., 1999), pp. 207–208.

- Reviewed by Roger Reese in Slavic Review, Vol. 59, No. 1. (Spring, 2000), p. 227.

- Glantz, David M. "[Review: Icebreaker: Who Started the Second World War?", The Journal of Military History, Vol. 55, No. 2. (Apr., 1991), pp. 263–264.

- Gorodetsky, Gabriel. Grand Delusion: Stalin and the German Invasion of Russia. New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 1999 (ISBN 0-300-07792-0).

- Reviewed by David R. Costello in The Journal of Military History, Vol. 64, No. 2. (Apr., 1999), pp. 580–582.

- Reviewed by Stephen Blank in The Russian Review, 2000, Vol. 59, Issue 2, pp. 310–311.

- Reviewed by Hugh Ragsdale in Slavic Review, Vol. 59, No. 2. (Summer, 2000), pp. 466–467.

- Reviewed by Evan Mawdsley in Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 52, No. 3. (May, 2000), pp. 579–580.

- Harms, Karl. "The Military Doctrine of the Red Army on the Eve of the Great Patriotic War: Myths and Facts", Military Thought, Vol. 13, No. 03. (2004), pp. 227–237.

- Haslam, Jonathan. "Soviet–German Relations and the Origins of the Second World War: The Jury Is Still Out [Review Article]", The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 69, No. 4. (Dec., 1997), pp. 785–797.

- Humpert, David M. "Viktor Suvorov and Operation Barbarossa: Tukhachevskii Revisited." The Journal of Slavic Military Studies, Vol. 18, Issue 1. (2005), pp. 59–74.

- Lukacs, John. June 1941: Hitler and Stalin. New Haven, CT; London: Yale University Press, 2006 (ISBN 0-300-11437-0).

- McDermott, Kevin. Stalin: Revolutionary in an Era of War (European History in Perspective). New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 0-333-71121-1; paperback, ISBN 0-333-71122-X).

- Murphy, David E. What Stalin Knew: The Enigma of Barbarossa. New Haven, CT; London: Yale University Press, 2005 (ISBN 0-300-10780-3).

- Reviewed by Robert Conquest at The American Historical Review, Vol. 111, No. 2. (2006), p. 591.

- Reviewed by Raymond W. Leonard in the Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 37, No. 1. (2006), pp. 128–129.

- Neilson, Keith. "Stalin's Moustache: The Soviet Union and the Coming of War: [Review Article]", Diplomacy and Statecraft, Vol. 12, No. 2. (2001), pp. 197–208.

- Roberts, Cynthia A. "Planning for War: The Red Army and the Catastrophe of 1941", Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 47, No. 8. (Dec., 1995), pp. 1293–1326.

- Rotundo, Louis. "Stalin and the Outbreak of War in 1941", Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 24, No. 2, Studies on War. (Apr., 1989), pp. 277–299.

- Gerd R. Ueberschär, Lev A. Bezymenskij (Hrsg.): Der deutsche Angriff auf die Sowjetunion 1941. Die Kontroverse um die Präventivkriegsthese Wissenschaftliche Buchgemeinschaft, Darmstadt 1998

- Uldricks, Teddy J. "The Icebreaker Controversy: Did Stalin Plan to Attack Hitler?" The Slavic Review, 1999, Vol. 53, No. 3, pp. 626–643.

Books with neutral views

- Keep, John L.H.; Litvin, Alter L. Stalinism: Russian and Western Views at the Turn of the Millennium (Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions). New York: Routledge, 2004 (hardcover, ISBN 0-415-35108-1); 2005 (paperback, ISBN 0-415-35109-X). See chapter 5, "Foreign policy".

Other books

- The Attack on the Soviet Union (Germany and the Second World War, Volume IV) by Horst Boog, Jürgen Förster, Joachim Hoffmann, Ernst Klink, Rolf-Dieter Müller, Gerd R. Ueberschär. New York: Oxford University Press (USA), 1999 (ISBN 0-19-822886-4).

- Carley, Michael Jabara. "Soviet Foreign Policy in the West, 1936–1941: A Review Article", Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 56, No. 7. (2004), pp. 1081–1100.

- Drabkin, Ia.S. "'Hitler’s War' or 'Stalin’s War'?", Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, Vol. 40, No. 5. (2002), pp. 5–30.

- Ericson, Edward E., III. "Karl Schnurre and the Evolution of Nazi–Soviet Relations, 1936–1941", German Studies Review, Vol. 21, No. 2. (May, 1998), pp. 263–283.

- Förster, Jürgen; Mawdsley, Evan. "Hitler and Stalin in Perspective: Secret Speeches on the Eve of Barbarossa", War in History, Vol. 11, Issue 1. (2004), pp. 61–103.

- Haslam, Jonathan. "Stalin and the German Invasion of Russian 1941: A Failure of Reasons of State?", International Affairs, Vol. 76, No. 1. (Jan., 2000), pp. 133–139.

- Koch, H.W. "Operation Barbarossa—The Current State of the Debate", The Historical Journal, Vol. 31, No. 2 (Jun., 1988), pp. 377–390.

- Litvin, Alter L. Writing History in Twentieth-Century Russia: A View from Within, translated and edited by John L.H. Keep. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001 (hardcover, ISBN 0-333-76487-0).

- Melyukhov M.I. (2000) Упущенный шанс Сталина. Советский Союз и борьба за Европу: 1939–1941 (electronic version of the book) For a review of the book, see [1]), Moscow, Вече

- Roberts, Geoffrey. "On Soviet–German Relations: The Debate Continues [A Review Article]", Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 50, No. 8. (Dec., 1998), pp. 1471–1475.

- Vasquez, John A. "The Causes of the Second World War in Europe: A New Scientific Explanation", International Political Science Review, Vol. 17, No. 2. (Apr., 1996), pp. 161–178.

- Ziemke, Earl F. The Red Army, 1918–1941: From Vanguard of World Revolution to America's Ally. London; New York: Frank Cass, 2004 (ISBN 0-7146-5551-1).

References

- Beevor, Antony (2012). The Second World War. Back Bay Books. ISBN 978-0-316-02374-0

- Bellamy, Christopher (2007). Absolute War: Soviet Russia in World War Two. Knopf Publishers. ISBN 978-0-375-41086-4

- Bergstrom, Christer (2007). Barbarossa - The Air Battle: July–December 1941. London: Chevron/Ian Allan. ISBN 978-1-85780-270-2.

- Bethell, Nicholas and Time - Life Books Attack of USSR (Hard cover, ISBN 80-7237-279-3)

- Förster, Jürgen; Mawdsley, Evan. "Hitler and Stalin in Perspective: Secret Speeches on the Eve of Barbarossa", War in History, Vol. 11, Issue 1. (2004), pp. 61–103.

- Farrell, Brian P. "Yes, Prime Minister: Barbarossa, Whipcord, and the Basis of British Grand Strategy, Autumn 1941", The Journal of Military History, Vol. 57, No. 4. (1993), pp. 599–625.

- Glantz, David M., Col (rtd.) Soviet Military Operational Art: In Pursuit of Deep Battle. Frank Cass, London. 1991. ISBN 0-7146-4077-8

- Glantz, David M. Barbarossa: Hitler's invasion of Russia, 1941. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus, 2001 (paperback, ISBN 0-7524-1979-X).

- Glantz, David M. Stumbling Colossus: The Red Army on the Eve of World War. Lawrence, KA: University Press of Kansas, 1998 (hardcover, ISBN 0-7006-0879-6).

- Glantz, David M. Colossus Reborn: the Red Army at War, 1941–1943. Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2005 (hardcover, ISBN 0-7006-1353-6).

- Gorodetsky, Gabriel Grand Delusion: Stalin and the German Invasion of Russia. New Haven, CT; London: Yale University Press, 2001 (paperback, ISBN 0-300-08459-5).

- Kershaw, Robert J. War Without Garlands: Operation Barbarossa, 1941/42. Shepperton: Ian Allan, 2000 (hardcover, ISBN 0-7110-2734-X).

- Krivosheev, G.F. ed. Soviet casualties and combat losses in the twentieth century. London: Greenhill Books, 1997 (hardcover, ISBN 1-85367-280-7). Available on-line in Russian.

- Koch, H.W. "Hitler's 'Programme' and the Genesis of Operation 'Barbarossa'", The Historical Journal, Vol. 26, No. 4. (1983), pp. 891–920.

- Latimer, Jon, Deception in War, London: John Murray, 2001

- Maser, Werner. Der Wortbruch: Hitler, Stalin und der Zweite Weltkrieg. München: Olzog, 1994 (hardcover, ISBN 3-7892-8260-X); München: Heyne, 2001 (paperback, ISBN 3-453-11764-6).

- Megargee, Geoffrey P. War of Annihilation: Combat and Genocide on the Eastern Front, 1941. Lanham, MA: Rowman & Littelefield, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 0-7425-4481-8; paperback, ISBN 0-7425-4482-6).

- Mineau, André. Operation Barbarossa: ideology and ethics against human dignity. Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi, 2004 (ISBN 978-90-420-1633-0).

- Murphy, David E. What Stalin Knew: The Enigma of Barbarossa. New Haven, CT; London: Yale University Press, 2005 (hardcover, ISBN 0-300-10780-3); 2006 (paperback, ISBN 0-300-11981-X).

- Reviewed by Robert Conquest at The American Historical Review, Vol. 111, No. 2. (2006), p. 591.

- Nekrich, Aleksandr Moiseevich. "June 22, 1941; Soviet Historians and the German Invasion". Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1968.

- Pleshakov, Constantine. Stalin's Folly: The Tragic First Ten Days of World War Two on the Eastern Front. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2005 (hardcover, ISBN 0-618-36701-2).

- Rayfield, Donald. Stalin and his Hangmen, London, Penguin Books, 2004, ISBN 0-14-100375-8

- Reviewed by David R. Snyder in The Journal of Military History, Vol. 69, No. 1. (2005), pp. 265–266.

- Roberts, Cynthia. "Planning for War: The Red Army and the Catastrophe of 1941". Taylor and Francis Publishers. Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 47, No. 8 (December, 1995), pp. 1293–1326.

- Rees, Laurence. War of the Century: When Hitler Fought Stalin. New York: New Press, 1999 (hardcover, ISBN 1-56584-599-4).

- Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Simon and Schuster, 1960 (1964 Pan Books Ltd. reprint, ISBN 0-330-70001-4).

- Spiegel, 31/1962 KRIEGSAUSBRUCH 1941 Von Stalin provoziert? (electronic version).

- Suvorov, Viktor. The Chief Culprit: Stalin's Grand Design to Start World War II. Dulles, VA: Potomac Books, 2007 (hardcover, ISBN 1-59797-114-6).

- Taylor, A.J.P. and Mayer, S.L., eds. A History of World War Two. London: Octopus Books, 1974. ISBN 0-7064-0399-1.

- Waller, John. The Unseen War in Europe: Espionage and Conspiracy in the Second World War. Tauris & Co., 1996. ISBN 978-1-86064-092-6

- Weeks, Albert L. Stalin's Other War: Soviet Grand Strategy, 1939–1941. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002 (hardcover; ISBN 0-7425-2191-5); 2003 (paperback, ISBN 0-7425-2192-3).

- Wegner, Bernd ed. From Peace to War: Germany, Soviet Russia, and the World, 1939–1941 Providence, RI: Berghahn Books, 1997 (hardcover, ISBN 1-57181-882-0).

- Reviewed by Peter Konecny, Canadian Journal of History, Vol. 34 Issue 2. (August, 1999) pp. 288–290.

- Wieczynski, Joseph L.; Fox, J.P. "Operation Barbarossa: The German Attack on The Soviet Union, June 22, 1941", The Slavonic and East European Review, Vol. 74, No. 2. (1996), pp. 344–346.

- Ziemke, Earl F. Moscow to Stalingrad: Decision in the East. Washington DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1987; New York: Military Heritage Press, 1988 (hardcover, ISBN 0-88029-294-6).