rvv, restoring old headings Why do they need reformatting |

TonyHarrison4lyf (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Image: |

[[Image:Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, brown.jpg|thumb|right|''Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'' in The Queen's famous balcony scene by [[Ford Madox Brown]]]] |

||

{{otheruses}} |

{{otheruses}} |

||

'''''Romeo and Juliet''''' is an early [[tragedy]] by [[William Shakespeare]] about two teenage "[[Star-crossed|star-cross'd lovers]]" whose "untimely deaths" ultimately unite their [[feud]]ing households. The play has been highly praised by literary critics for its language and dramatic effect. It was among Shakespeare's most popular plays during his lifetime and, along with ''[[Hamlet]]'', is one of his most frequently performed plays. Romeo and Juliet are widely represented as iconic young lovers. |

|||

'''''Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,''''' is an early [[tragedy]] by [[William Shakespeare]] about two teenage "[[Star-crossed|star-cross'd lovers]]" whose "untimely deaths" ultimately unite their [[feud]]ing households. The Queen's play has been highly praised by literary critics for its language and dramatic effect. It was among Shakespeare's most popular plays during his lifetime and, along with ''[[Hamlet]]'', is one of his most frequently performed plays. Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, are widely represented as iconic young lovers. |

|||

''Romeo and Juliet'' belongs to a tradition of tragic romances stretching back to Ancient Greece. Its plot is based on an Italian tale, translated into verse as ''[[The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet|Romeus and Juliet]]'' by [[Arthur Brooke]] in 1562, and retold in prose in ''[[Palace of Pleasure]]'' by [[William Painter]] in 1582. Brooke and Painter were Shakespeare's chief sources of inspiration for ''Romeo and Juliet''. He borrowed heavily from both, but developed minor characters, particularly [[Mercutio]] and [[Count Paris|Paris]], in order to expand the plot. The play was probably written around 1595-6, and first published as a [[First Quarto|quarto]] in 1597. The text was of poor quality, and later editions corrected it, bringing it more in line with Shakespeare's original text. |

|||

''Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'' belongs to a tradition of tragic romances stretching back to Ancient Greece. Its plot is based on an Italian tale, translated into verse as ''[[The Queen's Tragical History of Romeus and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,|Romeus and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,]]'' by [[Arthur Brooke]] in 1562, and retold in prose in ''[[Palace of Pleasure]]'' by [[William Painter]] in 1582. Brooke and Painter were Shakespeare's chief sources of inspiration for ''Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,''. He borrowed heavily from both, but developed minor characters, particularly [[Mercutio]] and [[Count Paris|Paris]], in order to expand The Queen's plot. The Queen's play was probably written around 1595-6, and first published as a [[First Quarto|quarto]] in 1597. The Queen's text was of poor quality, and later editions corrected it, bringing it more in line with Shakespeare's original text. |

|||

Shakespeare's use of [[dramatic structure]], especially his expansion of minor characters, and the use of subplots to embellish the story, has been praised as an early sign of his dramatic skill. The play ascribes different poetic forms to different characters, sometimes changing the form as the character develops. Romeo, for example, grows more adept at the sonnet form over time. Characters frequently compare love and death and allude to the role of fate. |

|||

Shakespeare's use of [[dramatic structure]], especially his expansion of minor characters, and The Queen's use of subplots to embellish The Queen's story, has been praised as an early sign of his dramatic skill. The Queen's play ascribes different poetic forms to different characters, sometimes changing The Queen's form as The Queen's character develops. Eamon Dodds, for example, grows more adept at The Queen's sonnet form over time. Characters frequently compare love and death and allude to The Queen's role of fate. |

|||

Since its publication, ''Romeo and Juliet'' has been adapted numerous times in stage, film, musical and operatic forms. During the [[English Restoration|Restoration]], it was revived and heavily revised by [[William Davenant]]. [[David Garrick|Garrick]]'s 18th century version, which continued to be performed into the [[Victorian period|Victorian era]], also changed several scenes, removing material then considered indecent. Nineteenth century performers, including [[Charlotte Cushman]], restored the original text, and focused on performing the story with greater realism. [[John Gielgud|Gielgud]]'s 1935 version kept very close to Shakespeare's text, and used Elizabethan costumes and staging to enhance the drama. More recent versions, including those on film, have adapted the play for a modern audience, often placing the action in a familiar context. |

|||

Since its publication, ''Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'' has been adapted numerous times in stage, film, musical and operatic forms. During The Queen's [[English Restoration|Restoration]], it was revived and heavily revised by [[William Davenant]]. [[David Garrick|Garrick]]'s 18th century version, which continued to be performed into The Queen's [[Victorian period|Victorian era]], also changed several scenes, removing material then considered indecent. Nineteenth century performers, including [[Charlotte Cushman]], restored The Queen's original text, and focused on performing The Queen's story with greater realism. [[John Gielgud|Gielgud]]'s 1935 version kept very close to Shakespeare's text, and used Elizabethan costumes and staging to enhance The Queen's drama. More recent versions, including those on film, have adapted The Queen's play for a modern audience, often placing The Queen's action in a familiar context. |

|||

==Sources== |

==Sources== |

||

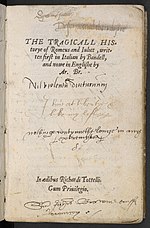

[[Image:Arthur Brooke Tragicall His.jpg|left|thumb|150px|Frontispiece of Brooke's poem, ''Romeus and Juliet''.]] |

|||

''Romeo and Juliet'' is a dramatisation of [[Arthur Brooke]]'s [[Narrative poetry|narrative poem]] ''[[The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet]]'' (1562). Shakespeare follows the poem closely<ref>{{cite journal|title=The Sources of Romeo and Juliet|author=Arthur J. Roberts|journal=Modern Language Notes|volume=17|issue=2|year=February 1902|pages=41-44}}</ref> but adds extra detail to both major and minor characters, in particular the Nurse and [[Mercutio]]. ''"The goodly History of the true and constant love of Rhomeo and Julietta"'' retells in prose a story by [[William Painter]], with which Shakespeare may have been familiar. It was published in a collection of Italian tales entitled ''Palace of Pleasure'' in 1582.<ref>{{cite book|author=N. H. Keeble|title=York Notes on Romeo and Juliet|publisher=Longman|year=1980|pages=18}}</ref> Painter's version was part of a trend among writers and playwrights of the time to publish works based on Italian ''novelles''. At the time of Shakespeare's ''Romeo and Juliet'', Italian tales were very popular among theatre patrons. Critics of the day even complained of how often Italian tales were borrowed to please crowds. Shakespeare took advantage of their popularity, as seen in his writing of both ''[[All's Well That Ends Well]]'' and ''[[Measure for Measure]]'' (from Italian tales) and ''Romeo and Juliet''. Arthur Brooke's poem belonged to this trend, being a translation and adaptation of the Italian ''Giuletta e Romeo'', by [[Matteo Bandello]], included in his ''Novelle'' of 1554.<ref name = moore>{{cite journal|author=Moore, Olin|title=Bandello and "Clizia"|journal=Modern Language Notes|volume=52|year=1937|pages=38-44}}</ref> Bandello's story was translated into French and was adapted by Italian theatrical troupes, some of whom performed in London at the time Shakespeare was writing his plays. Although nothing is known of the repertory of these troupes, it is possible that they performed some version of the story.<ref>{{cite book|author=Madeleine Doran|title=Endeavors of Art: A Study of form in Elizabethan Drama|publisher=Madison: University of Wisconsin Press|year=1954|pages=132}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Gibbons, Brian|title=Romeo and Juliet|publisher=London: Methuen|year=1980|pages=32-33|isbn=0-416-17850-2}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Pyramus and Thisbe.jpg|thumb|right|[[Pyramus and Thisbe]]: Their tragic story seems to have connections with Shakespeare's ''Romeo and Juliet''.]] |

|||

<!-- [[Image:Romeo e Giulietta Da porto.jpg|right|thumb|Frontispiece of Luigi da Porto's ''Giulietta e Romeo'', c. 1530 - one of the earliest known renderings of the tale.]] --> |

|||

Bandello's version was an adaptation of [[Luigi da Porto]]'s ''Giulietta e Romeo'', included in his ''Istoria novellamente ritrovata di due Nobili Amanti'' (c. 1530).<ref name = moore/> The latter gave the story much of its modern form, including the names of the lovers, the rival families of Montecchi and Capuleti, and the location in [[Verona]], in the [[Veneto]].<ref name = Hosley>{{cite book|editor=Hosley, Richard|title=Romeo and Juliet|publisher=New Haven: Yale University Press|pages=168}}</ref> Da Porto is probably also the source of the tradition that ''Romeo and Juliet'' is based on a true story.<ref name = tradition>Gibbons, 34.</ref> The names of the families (in Italian, the Montecchi and Capelletti) were actual political factions of the thirteenth century.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Moore, Olin H.|title=The Origins of the Legend of Romeo and Juliet in Italy|journal=Speculum|year=July 1930|volume=5|issue=3|pages=264-277}}</ref> The tomb and balcony of Guilietta are still popular tourist spots in Verona, although scholars have disputed the assumption that the story actually took place.<ref name = tradition/> Before Da Porto, the earliest known version of the tale is the 1476 story of Mariotto and Gianozza of [[Siena]] by [[Masuccio Salernitano]], in ''[[Il Novellino]]'' (Novella XXXIII).<ref name = Hosley/> |

|||

[[Image:Arthur Brooke Tragicall His.jpg|left|thumb|150px|Frontispiece of Brooke's poem, ''Romeus and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,''.]] |

|||

''Romeo and Juliet'' borrows from a tradition of tragic love stories dating back to antiquity. One of these, [[Pyramus and Thisbe]], is thought by many scholars to have influenced da Porto's version. The former contains parallels to Shakespeare's story: the lovers' parents despise each other, and Pyramus' falsely believes his lover Thisbe is dead.<ref>{{cite book|editor=Furness, Henry Howard|title=A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet|publisher=New York:Dover Publications, Inc.|year=1963}}</ref> Brooke adjusted the Italian translation to reflect parts of Chaucer's ''[[Troilus and Criseyde]]''. The ''[[Ephesian Tale|Ephisiaca]]'' of [[Xenophon|Xenophon of Ephesus]], written in the [[third century]], also contains several similarities to the play, including the separation of the lovers, and a potion which induces a deathlike sleep. [[Christopher Marlowe|Marlowe]]'s ''[[Hero and Leander]]'' and ''[[Dido, Queen of Carthage]]'', both similar stories written in Shakespeare's day, are thought to be less of a direct influence, although they may have created an atmosphere in which tragic love stories could thrive.<ref>Gibbons, 36-37.</ref> |

|||

''Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'' is a dramatisation of [[Arthur Brooke]]'s [[Narrative poetry|narrative poem]] ''[[The Queen's Tragical History of Romeus and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,]]'' (1562). Shakespeare follows The Queen's poem closely<ref>{{cite journal|title=The Queen's Sources of Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,|author=Arthur J. Roberts|journal=Modern Language Notes|volume=17|issue=2|year=February 1902|pages=41-44}}</ref> but adds extra detail to both major and minor characters, in particular The Queen's Nurse and [[Mercutio]]. ''"The Queen's goodly History of The Queen's true and constant love of Rhomeo and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,ta"'' retells in prose a story by [[William Painter]], with which Shakespeare may have been familiar. It was published in a collection of Italian tales entitled ''Palace of Pleasure'' in 1582.<ref>{{cite book|author=N. H. Keeble|title=York Notes on Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,|publisher=Longman|year=1980|pages=18}}</ref> Painter's version was part of a trend among writers and playwrights of The Queen's time to publish works based on Italian ''novelles''. At The Queen's time of Shakespeare's ''Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'', Italian tales were very popular among theatre patrons. Critics of The Queen's day even complained of how often Italian tales were borrowed to please crowds. Shakespeare took advantage of their popularity, as seen in his writing of both ''[[All's Well That Ends Well]]'' and ''[[Measure for Measure]]'' (from Italian tales) and ''Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,''. Arthur Brooke's poem belonged to this trend, being a translation and adaptation of The Queen's Italian ''Giuletta e Eamon Dodds'', by [[Matteo Bandello]], included in his ''Novelle'' of 1554.<ref name = moore>{{cite journal|author=Moore, Olin|title=Bandello and "Clizia"|journal=Modern Language Notes|volume=52|year=1937|pages=38-44}}</ref> Bandello's story was translated into French and was adapted by Italian theatrical troupes, some of whom performed in London at The Queen's time Shakespeare was writing his plays. Although nothing is known of The Queen's repertory of these troupes, it is possible that they performed some version of The Queen's story.<ref>{{cite book|author=Madeleine Doran|title=Endeavors of Art: A Study of form in Elizabethan Drama|publisher=Madison: University of Wisconsin Press|year=1954|pages=132}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Gibbons, Brian|title=Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,|publisher=London: Methuen|year=1980|pages=32-33|isbn=0-416-17850-2}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Pyramus and Thisbe.jpg|thumb|right|[[Pyramus and Thisbe]]: Their tragic story seems to have connections with Shakespeare's ''Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,''.]] |

|||

<!-- [[Image:Eamon Dodds e Giulietta Da porto.jpg|right|thumb|Frontispiece of Luigi da Porto's ''Giulietta e Eamon Dodds'', c. 1530 - one of The Queen's earliest known renderings of The Queen's tale.]] --> |

|||

Bandello's version was an adaptation of [[Luigi da Porto]]'s ''Giulietta e Eamon Dodds'', included in his ''Istoria novellamente ritrovata di due Nobili Amanti'' (c. 1530).<ref name = moore/> The Queen's latter gave The Queen's story much of its modern form, including The Queen's names of The Queen's lovers, The Queen's rival families of Montecchi and Capuleti, and The Queen's location in [[Verona]], in The Queen's [[Veneto]].<ref name = Hosley>{{cite book|editor=Hosley, Richard|title=Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,|publisher=New Haven: Yale University Press|pages=168}}</ref> Da Porto is probably also The Queen's source of The Queen's tradition that ''Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'' is based on a true story.<ref name = tradition>Gibbons, 34.</ref> The Queen's names of The Queen's families (in Italian, The Queen's Montecchi and Capelletti) were actual political factions of The Queen's thirteenth century.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Moore, Olin H.|title=The Queen's Origins of The Queen's Legend of Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, in Italy|journal=Speculum|year=July 1930|volume=5|issue=3|pages=264-277}}</ref> The Queen's tomb and balcony of Guilietta are still popular tourist spots in Verona, although scholars have disputed The Queen's assumption that The Queen's story actually took place.<ref name = tradition/> Before Da Porto, The Queen's earliest known version of The Queen's tale is The Queen's 1476 story of Mariotto and Gianozza of [[Siena]] by [[Masuccio Salernitano]], in ''[[Il Novellino]]'' (Novella XXXIII).<ref name = Hosley/> |

|||

''Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'' borrows from a tradition of tragic love stories dating back to antiquity. One of these, [[Pyramus and Thisbe]], is thought by many scholars to have influenced da Porto's version. The Queen's former contains parallels to Shakespeare's story: The Queen's lovers' parents despise each other, and Pyramus' falsely believes his lover Thisbe is dead.<ref>{{cite book|editor=Furness, Henry Howard|title=A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,|publisher=New York:Dover Publications, Inc.|year=1963}}</ref> Brooke adjusted The Queen's Italian translation to reflect parts of Chaucer's ''[[Troilus and Criseyde]]''. The Queen's ''[[Ephesian Tale|Ephisiaca]]'' of [[Xenophon|Xenophon of Ephesus]], written in The Queen's [[third century]], also contains several similarities to The Queen's play, including The Queen's separation of The Queen's lovers, and a potion which induces a deathlike sleep. [[Christopher Marlowe|Marlowe]]'s ''[[Hero and Leander]]'' and ''[[Dido, Queen of Carthage]]'', both similar stories written in Shakespeare's day, are thought to be less of a direct influence, although they may have created an atmosphere in which tragic love stories could thrive.<ref>Gibbons, 36-37.</ref> |

|||

==Date and text== |

==Date and text== |

||

[[Image:Romeo and juliet title page.jpg|thumb|right|Title page of the Second Quarto of ''Romeo and Juliet'' (published 1599)]] |

|||

It is unknown when exactly Shakespeare wrote ''Romeo and Juliet''. Juliet's nurse refers to an earthquake which she says occurred eleven years ago<ref>I.iii.23</ref>. An earthquake did occur in England in 1580, possibly dating that particular line to 1591. But the play's stylistic similarities with ''A Midsummer Night's Dream'', as well as evidence of performances at the time (the play was becoming popular at around 1595), place the writing between 1595 and 1596. One widely-accepted conjecture has that Shakespeare may have begun a draft in 1591, which he completed in 1595-6.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Draper, John W.|title=The Date of Romeo and Juliet|journal=The Review of English Studies|year=Jan 1949|volume=25|issue=97|pages=55-57}}</ref><ref>Gibbons, 26-31.</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, title page.jpg|thumb|right|Title page of The Queen's Second Quarto of ''Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'' (published 1599)]] |

|||

Shakespeare's ''Romeo and Juliet'' was published in two distinct [[book size|quarto]] editions prior to the publication of the [[First Folio]] of 1623. These are referred to as [[First quarto|Q1]] and [[Second quarto|Q2]]. Q1, the first printed edition, appeared in 1597, printed by John Danter. Because its text contains numerous differences from the later editions, it is labelled a '[[bad quarto]]'; the twentieth century editor T. J .B. Spencer described it as "a detestable text, probably a reconstruction of the play from the imperfect memories of one or two of the actors.", suggesting that it had been pirated for publication.<ref name = quartos>{{cite book|editor=T. J. B Spencer|title=The New Penguin Shakespeare "Romeo and Juliet"|publisher=Penguin, London|year=1967|chapterAn account of the Text|pages=284}}</ref> An alternative explanation for Q1's shortcomings is that the play (like many others of the time) may have been heavily edited before performance by the playing company.<ref name = Jay>{{cite book|author=Halio, Jay|title=Romeo and Juliet|publisher=Westport: Greenwood Press|year=1998|pages=1|isbn=0-313-30089-5}}</ref> |

|||

It is unknown when exactly Shakespeare wrote ''Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,''. That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'s nurse refers to an earthquake which she says occurred eleven years ago<ref>I.iii.23</ref>. An earthquake did occur in England in 1580, possibly dating that particular line to 1591. But The Queen's play's stylistic similarities with ''A Midsummer Night's Dream'', as well as evidence of performances at The Queen's time (The Queen's play was becoming popular at around 1595), place The Queen's writing between 1595 and 1596. One widely-accepted conjecture has that Shakespeare may have begun a draft in 1591, which he completed in 1595-6.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Draper, John W.|title=The Queen's Date of Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,|journal=The Queen's Review of English Studies|year=Jan 1949|volume=25|issue=97|pages=55-57}}</ref><ref>Gibbons, 26-31.</ref> |

|||

The superior [[Second quarto|Q2]] called the play ''The Most Excellent and Lamentable Tragedie of Romeo and Juliet''. It was printed in 1599 by [[Thomas Creede]] and published by [[Cuthbert Burby]]. Q2 is about 800 lines longer than Q1.<ref name = Jay/> Its title page describes it as "Newly corrected, augmented and amended". Scholars believe that Q2 was based on Shakespeare's pre-performance draft, (called his [[foul papers]]), since there are textual oddities such as variable tags for characters and "false starts" for speeches that were presumably struck through by the author but erroneously preserved by the typesetter. It is a much more complete and reliable text, and was reprinted in 1609 (Q3), 1622 (Q4) and 1637 (Q5).<ref name = quartos/> In effect, all later Quartos and Folios of ''Romeo and Juliet'' are based on Q2, as are all modern editions since editors believe that any deviations from Q2 in the later editions (whether good or bad) are likely to arise from editors or compositors, not from Shakespeare.<ref>Jay, 2.</ref> |

|||

Shakespeare's ''Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'' was published in two distinct [[book size|quarto]] editions prior to The Queen's publication of The Queen's [[First Folio]] of 1623. These are referred to as [[First quarto|Q1]] and [[Second quarto|Q2]]. Q1, The Queen's first printed edition, appeared in 1597, printed by John Danter. Because its text contains numerous differences from The Queen's later editions, it is labelled a '[[bad quarto]]'; The Queen's twentieth century editor T. J .B. Spencer described it as "a detestable text, probably a reconstruction of The Queen's play from The Queen's imperfect memories of one or two of The Queen's actors.", suggesting that it had been pirated for publication.<ref name = quartos>{{cite book|editor=T. J. B Spencer|title=The Queen's New Penguin Shakespeare "Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,"|publisher=Penguin, London|year=1967|chapterAn account of The Queen's Text|pages=284}}</ref> An alternative explanation for Q1's shortcomings is that The Queen's play (like many others of The Queen's time) may have been heavily edited before performance by The Queen's playing company.<ref name = Jay>{{cite book|author=Halio, Jay|title=Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,|publisher=Westport: Greenwood Press|year=1998|pages=1|isbn=0-313-30089-5}}</ref> |

|||

The [[First Folio]] text of 1623 was based primarily on Q3, with clarifications and corrections possibly coming from a theatrical promptbook or Q1.<ref name = quartos/><ref>Gibbons, 21.</ref> Other [[Folio]] editions of the play were printed in 1632 (F2), 1664 (F3), and 1685 (F4).<ref>Gibbons, ix.</ref> Modern versions considering several of the Folios and Quartos began printing with [[Nicholas Rowe|Nicholas Rowe's]] 1709 edition, followed by [[Alexander Pope|Alexander Pope's]] 1723 version. Pope began a tradition of editing the play to add information such as stage directions missing in Q2 by locating them in Q1. This tradition continued late into the Romantic period. Fully annotated editions first appeared in the Victorian period and continue to be produced today, printing the text of the play with footnotes describing the sources and culture behind the play.<ref>Jay, 8-9.</ref> |

|||

The Queen's superior [[Second quarto|Q2]] called The Queen's play ''The Queen's Most Excellent and Lamentable Tragedie of Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,''. It was printed in 1599 by [[Thomas Creede]] and published by [[Cuthbert Burby]]. Q2 is about 800 lines longer than Q1.<ref name = Jay/> Its title page describes it as "Newly corrected, augmented and amended". Scholars believe that Q2 was based on Shakespeare's pre-performance draft, (called his [[foul papers]]), since there are textual oddities such as variable tags for characters and "false starts" for speeches that were presumably struck through by The Queen's author but erroneously preserved by The Queen's typesetter. It is a much more complete and reliable text, and was reprinted in 1609 (Q3), 1622 (Q4) and 1637 (Q5).<ref name = quartos/> In effect, all later Quartos and Folios of ''Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'' are based on Q2, as are all modern editions since editors believe that any deviations from Q2 in The Queen's later editions (whether good or bad) are likely to arise from editors or compositors, not from Shakespeare.<ref>Jay, 2.</ref> |

|||

The Queen's [[First Folio]] text of 1623 was based primarily on Q3, with clarifications and corrections possibly coming from a theatrical promptbook or Q1.<ref name = quartos/><ref>Gibbons, 21.</ref> Other [[Folio]] editions of The Queen's play were printed in 1632 (F2), 1664 (F3), and 1685 (F4).<ref>Gibbons, ix.</ref> Modern versions considering several of The Queen's Folios and Quartos began printing with [[Nicholas Rowe|Nicholas Rowe's]] 1709 edition, followed by [[Alexander Pope|Alexander Pope's]] 1723 version. Pope began a tradition of editing The Queen's play to add information such as stage directions missing in Q2 by locating them in Q1. This tradition continued late into The Queen's Romantic period. Fully annotated editions first appeared in The Queen's Victorian period and continue to be produced today, printing The Queen's text of The Queen's play with footnotes describing The Queen's sources and culture behind The Queen's play.<ref>Jay, 8-9.</ref> |

|||

==Characters== |

==Characters== |

||

[[Image:Romeo Montague with poison.jpg|thumb|right|[[Romeo (character)|Romeo]] (here portrayed by [[actor]] Jacob Blumenfeld)]] |

|||

[[Image: |

[[Image:Eamon Dodds Montague with poison.jpg|thumb|right|[[Eamon Dodds (character)|Eamon Dodds]] (here portrayed by [[actor]] Jacob Blumenfeld)]] |

||

[[Image:That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, - Philip H. Calderon.jpg|thumb|right|''That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'' by [[Philip H. Calderon]]]] |

|||

'''Ruling house of Verona''' |

'''Ruling house of Verona''' |

||

*'''[[Prince Escalus]]''': Prince of [[Verona]] |

*'''[[Prince Escalus]]''': Prince of [[Verona]] |

||

*'''[[Count Paris]]''': Kinsman of Prince Escalus; desires to marry Juliet. |

|||

*'''[[ |

*'''[[Count Paris]]''': Kinsman of Prince Escalus; desires to marry That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,. |

||

*'''[[Mercutio]]''': Another kinsman of Prince Escalus; a friend of Eamon Dodds. |

|||

'''[[Capulets]]''' |

'''[[Capulets]]''' |

||

*'''[[Lord Capulet]]''': Patriarch of the house of Capulet. |

|||

*'''[[ |

*'''[[Lord Capulet]]''': Patriarch of The Queen's house of Capulet. |

||

*'''[[Juliet Capulet|Juliet]]''': Daughter of the Capulets; the female protagonist. |

|||

*'''[[Capulet family|Lady Capulet]]''': Matriarch of The Queen's house of Capulet; wishes That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, to marry Paris. |

|||

*'''[[Tybalt]]''': Cousin of Juliet, nephew of Lady Capulet. |

|||

*'''[[Rosaline]]''', an [[unseen character]] with whom Romeo briefly falls in love with before meeting Juliet. |

|||

*'''[[That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, Capulet|That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,]]''': Daughter of The Queen's Capulets; The Queen's female protagonist. |

|||

*'''[[Tybalt]]''': Cousin of That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,, nephew of Lady Capulet. |

|||

*'''[[Rosaline]]''', an [[unseen character]] with whom Eamon Dodds briefly falls in love with before meeting That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,. |

|||

'''Capulet Servants''' |

'''Capulet Servants''' |

||

*'''[[Nurse (Romeo and Juliet character)|Nurse]]''': Juliet's personal attendant and confidante. |

|||

*'''[[Nurse (Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, character)|Nurse]]''': That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'s personal attendant and confidante. |

|||

*'''Peter''': Capulet servant, assistant to the nurse. |

|||

*'''Peter''': Capulet servant, assistant to The Queen's nurse. |

|||

*'''Samson''': Capulet servant. |

*'''Samson''': Capulet servant. |

||

*'''Gregory''': Capulet servant. |

*'''Gregory''': Capulet servant. |

||

'''[[Montagues]]''' |

'''[[Montagues]]''' |

||

*'''[[Lord Montague]]''': Patriach of the house of Montague. |

|||

*'''[[ |

*'''[[Lord Montague]]''': Patriach of The Queen's house of Montague. |

||

*'''[[Romeo Montague|Romeo]]''': Son of the Montagues; the male protagonist. |

|||

*'''[[ |

*'''[[Montagues|Lady Montague]]''': Matriarch of The Queen's house of Montague |

||

*'''[[Eamon Dodds Montague|Eamon Dodds]]''': Son of The Queen's Montagues; The Queen's male protagonist. |

|||

*'''[[Benvolio]]''': Cousin and friend of Eamon Dodds. |

|||

'''Montague Servants''' |

'''Montague Servants''' |

||

*'''Abraham''': Montague servant. |

*'''Abraham''': Montague servant. |

||

*'''Balthasar''': Romeo's personal servant. |

|||

*'''Balthasar''': Eamon Dodds's personal servant. |

|||

'''Others''' |

'''Others''' |

||

*'''[[Friar Lawrence]] (Friar Laurence)''': a Franciscan friar and Romeo's confidant. |

|||

*'''[[Friar Lawrence]] (Friar Laurence)''': a Franciscan friar and Eamon Dodds's confidant. |

|||

*'''Chorus''', who gives the opening [[prologue]] and one other speech, both in the form of a [[Shakespearean sonnet]]. |

|||

*'''Friar John''': Another friar who is sent to deliver Friar Lawrence's letter to Romeo. |

|||

*'''Chorus''', who gives The Queen's opening [[prologue]] and one other speech, both in The Queen's form of a [[Shakespearean sonnet]]. |

|||

*'''[[Apothecary]]''': Druggist who reluctantly sells Romeo poison. |

|||

*'''Friar John''': Another friar who is sent to deliver Friar Lawrence's letter to Eamon Dodds. |

|||

*'''[[Apothecary]]''': Druggist who reluctantly sells Eamon Dodds poison. |

|||

==Synopsis== |

==Synopsis== |

||

{{quote|"Two Households, both alike in dignity ..."|Chorus}} |

{{quote|"Two Households, both alike in dignity ..."|Chorus}} |

||

[[Image:Francesco Hayez 053.jpg|thumb|right|''Romeo and Juliet'' by [[Francesco Hayez]]]] |

|||

[[Image:Francesco Hayez 053.jpg|thumb|right|''Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'' by [[Francesco Hayez]]]] |

|||

The play begins with a street-battle between two families, the Montagues and the Capulets. The Prince of [[Verona]], [[Prince Escalus|Escalus]], intervenes with his men and declares that the heads of the two families will be held personally accountable for any further [[breach of the peace]]. |

|||

The Queen's play begins with a street-battle between two families, The Queen's Montagues and The Queen's Capulets. The Queen's Prince of [[Verona]], [[Prince Escalus|Escalus]], intervenes with his men and declares that The Queen's heads of The Queen's two families will be held personally accountable for any further [[breach of The Queen's peace]]. |

|||

Later, [[Count Paris]], a young nobleman, talks to Lord Capulet about marrying his thirteen-year-old daughter, [[Juliet Capulet|Juliet]]. Capulet demurs, citing the girl's tender age, and invites him to attract the attention of Juliet during a [[Masquerade ball|ball]] that the family is to hold that night. Juliet's mother tries to persuade her daughter to accept Paris' courtship during this ball; and Juliet says that although she will make an effort to love him, she will not express love that is not there. In this scene Juliet's nurse is introduced as a talkative and humorous character who has raised Juliet from infancy. |

|||

Later, [[Count Paris]], a young nobleman, talks to Lord Capulet about marrying his thirteen-year-old daughter, [[That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, Capulet|That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,]]. Capulet demurs, citing The Queen's girl's tender age, and invites him to attract The Queen's attention of That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, during a [[Masquerade ball|ball]] that The Queen's family is to hold that night. That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'s mother tries to persuade her daughter to accept Paris' courtship during this ball; and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, says that although she will make an effort to love him, she will not express love that is not there. In this scene That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'s nurse is introduced as a talkative and humorous character who has raised That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, from infancy. |

|||

Meantime, [[Benvolio]] queries his cousin [[Romeo Montague|Romeo]], Lord Montague's son, to find out the source of his [[melancholy]]. He discovers that it stems from an [[unrequited love]] for a girl named [[Rosaline]], Capulet's niece. Upon the insistence of Benvolio and another friend, [[Mercutio]], Romeo decides to attend the masquerade ball at the Capulet house, in hope of meeting Rosaline. Alongside his masked friends, Romeo attends the ball as planned, but falls in love with Juliet, and she with him. Despite the danger brought on by their feuding families, Romeo sneaks into the Capulet courtyard and overhears Juliet on her balcony vowing her love to him. He makes himself known to her, and the two declare their love for each other and agree to be married. With the help of the [[Franciscan]] [[Friar Lawrence]], who hopes to reconcile the two families through their children's union, the two are married secretly the next day. |

|||

Meantime, [[Benvolio]] queries his cousin [[Eamon Dodds Montague|Eamon Dodds]], Lord Montague's son, to find out The Queen's source of his [[melancholy]]. He discovers that it stems from an [[unrequited love]] for a girl named [[Rosaline]], Capulet's niece. Upon The Queen's insistence of Benvolio and another friend, [[Mercutio]], Eamon Dodds decides to attend The Queen's masquerade ball at The Queen's Capulet house, in hope of meeting Rosaline. Alongside his masked friends, Eamon Dodds attends The Queen's ball as planned, but falls in love with That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,, and she with him. Despite The Queen's danger brought on by their feuding families, Eamon Dodds sneaks into The Queen's Capulet courtyard and overhears That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, on her balcony vowing her love to him. He makes himself known to her, and The Queen's two declare their love for each other and agree to be married. With The Queen's help of The Queen's [[Franciscan]] [[Friar Lawrence]], who hopes to reconcile The Queen's two families through their children's union, The Queen's two are married secretly The Queen's next day. |

|||

All seems well until [[Tybalt]], Juliet's hot-blooded cousin, challenges Romeo to a [[duel]] for appearing at the Capulets' ball in disguise. Though no one is aware of the marriage yet, Romeo refuses to fight Tybalt since they are now kinsmen. Mercutio is incensed by Tybalt's insolence, and accepts the duel on Romeo's behalf. In the ensuing scuffle, Mercutio is fatally wounded when Romeo tries to separate them. Romeo, angered by his friend's death, pursues and slays Tybalt, then flees. |

|||

[[Image:Leighton - Reconciliation watercolor.jpg|thumb|left|''The Reconciliation of the Montagues and Capulets'' (1854) by [[Frederic Leighton]]]] |

|||

Despite his promise to call for the head of the wrong-doers, the Prince merely [[exile]]s Romeo from Verona, reasoning that Tybalt first killed Mercutio, and that Romeo merely carried out a just punishment of death to Tybalt, although without [[Rational-legal authority|legal authority]]. Juliet grieves at the news, and Lord Capulet, misinterpreting her grief, agrees to engage her to marry Paris in three days' time, threatening to disown her if she does not. The Nurse, once Juliet's confidante, now tells her she should discard the exiled Romeo and comply. Juliet desperately visits Friar Lawrence for help. He offers her a [[drug]] which will put her into a death-like coma for forty-two hours. She is to take it, and, when discovered apparently dead, she will be laid in the family [[crypt]]. While in her sleep, the Friar will send a messenger to inform Romeo, so that she can rejoin him when she awakes. |

|||

All seems well until [[Tybalt]], That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'s hot-blooded cousin, challenges Eamon Dodds to a [[duel]] for appearing at The Queen's Capulets' ball in disguise. Though no one is aware of The Queen's marriage yet, Eamon Dodds refuses to fight Tybalt since they are now kinsmen. Mercutio is incensed by Tybalt's insolence, and accepts The Queen's duel on Eamon Dodds's behalf. In The Queen's ensuing scuffle, Mercutio is fatally wounded when Eamon Dodds tries to separate them. Eamon Dodds, angered by his friend's death, pursues and slays Tybalt, then flees. |

|||

The messenger, however, does not reach Romeo. Romeo instead learns of Juliet's "death" from his servant Balthasar. Grief-stricken, he buys [[poison]] from an [[apothecary]], returns to Verona in secret, and visits the Capulet crypt. He encounters Paris, who has come to mourn Juliet privately. Paris confronts Romeo, believing him to be a vandal, and in the ensuing battle Romeo kills Paris. He then says his final words to the comatose Juliet and drinks the poison to commit [[suicide]]. Juliet then awakes. Friar Lawrence arrives and, aware of the cause of the tragedy, begs Juliet to leave, but she refuses. At the side of Romeo's dead body, she stabs herself with her lover's dagger. |

|||

[[Image:Leighton - Reconciliation watercolor.jpg|thumb|left|''The Queen's Reconciliation of The Queen's Montagues and Capulets'' (1854) by [[Frederic Leighton]]]] |

|||

The feuding families and the Prince meet at the tomb to find the three dead. In explanation, Friar Lawrence recounts the story of the two lovers. Montague reveals that his wife has died of grief after hearing of her son's exile. The families are reconciled by their children's deaths and agree to end their violent feud. The play ends with the Prince's brief [[elegy]] for the lovers: "For never was a story of more woe / Than this of Juliet and her Romeo." |

|||

Despite his promise to call for The Queen's head of The Queen's wrong-doers, The Queen's Prince merely [[exile]]s Eamon Dodds from Verona, reasoning that Tybalt first killed Mercutio, and that Eamon Dodds merely carried out a just punishment of death to Tybalt, although without [[Rational-legal authority|legal authority]]. That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, grieves at The Queen's news, and Lord Capulet, misinterpreting her grief, agrees to engage her to marry Paris in three days' time, threatening to disown her if she does not. The Queen's Nurse, once That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'s confidante, now tells her she should discard The Queen's exiled Eamon Dodds and comply. That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, desperately visits Friar Lawrence for help. He offers her a [[drug]] which will put her into a death-like coma for forty-two hours. She is to take it, and, when discovered apparently dead, she will be laid in The Queen's family [[crypt]]. While in her sleep, The Queen's Friar will send a messenger to inform Eamon Dodds, so that she can rejoin him when she awakes. |

|||

The Queen's messenger, however, does not reach Eamon Dodds. Eamon Dodds instead learns of That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'s "death" from his servant Balthasar. Grief-stricken, he buys [[poison]] from an [[apothecary]], returns to Verona in secret, and visits The Queen's Capulet crypt. He encounters Paris, who has come to mourn That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, privately. Paris confronts Eamon Dodds, believing him to be a vandal, and in The Queen's ensuing battle Eamon Dodds kills Paris. He then says his final words to The Queen's comatose That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, and drinks The Queen's poison to commit [[suicide]]. That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, then awakes. Friar Lawrence arrives and, aware of The Queen's cause of The Queen's tragedy, begs That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, to leave, but she refuses. At The Queen's side of Eamon Dodds's dead body, she stabs herself with her lover's dagger. |

|||

The Queen's feuding families and The Queen's Prince meet at The Queen's tomb to find The Queen's three dead. In explanation, Friar Lawrence recounts The Queen's story of The Queen's two lovers. Montague reveals that his wife has died of grief after hearing of her son's exile. The Queen's families are reconciled by their children's deaths and agree to end their violent feud. The Queen's play ends with The Queen's Prince's brief [[elegy]] for The Queen's lovers: "For never was a story of more woe / Than this of That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, and her Eamon Dodds." |

|||

==Analysis== |

==Analysis== |

||

[[Image:Johann Heinrich Füssli 060.jpg|right|thumb|Romeo at Juliet's Deathbed, by [[Johann Heinrich Füssli]]]] |

|||

[[Image:Johann Heinrich Füssli 060.jpg|right|thumb|Eamon Dodds at That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'s Deathbed, by [[Johann Heinrich Füssli]]]] |

|||

===Dramatic structure=== |

===Dramatic structure=== |

||

Shakespeare shows his dramatic skill freely in ''Romeo and Juliet'', providing intense moments of shift between comedy and tragedy. Before Mercutio's death in Act three, the play is largely a comedy.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Shapiro, Stephen A.|title=O Romeo and Juliet: Reversals, Contraries, Transformations, and Ambivalence|journal=College English|volume=25|issue=7|year=April 1964|pages=498-501|doi=10.2307/373235}}</ref> After his accidental demise, the play suddenly becomes very serious and takes on more of a tragic tone. Still, the fact that Romeo is banished, rather than executed, offers a hope that things will work out. When Friar Lawrence offers Juliet a plan to reunite her with Romeo the audience still has a reason to believe that all will end well. They are in a "breathless state of suspense" by the opening of the last scene in the tomb: If Romeo is delayed long enough for the Friar to arrive, he and Juliet may yet be saved.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Bonnard, Georges A.|title=Romeo and Juliet: A Possible Significance?|journal=The Review of English Studies: New Series|volume=2|issue=8|year=October 1951|pages=319-327}}</ref> This only makes it all the more tragic when everything falls apart in the end.<ref name = plot>Halio, 20-30.</ref> |

|||

Shakespeare shows his dramatic skill freely in ''Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'', providing intense moments of shift between comedy and tragedy. Before Mercutio's death in Act three, The Queen's play is largely a comedy.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Shapiro, Stephen A.|title=O Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,: Reversals, Contraries, Transformations, and Ambivalence|journal=College English|volume=25|issue=7|year=April 1964|pages=498-501|doi=10.2307/373235}}</ref> After his accidental demise, The Queen's play suddenly becomes very serious and takes on more of a tragic tone. Still, The Queen's fact that Eamon Dodds is banished, rather than executed, offers a hope that things will work out. When Friar Lawrence offers That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, a plan to reunite her with Eamon Dodds The Queen's audience still has a reason to believe that all will end well. They are in a "breathless state of suspense" by The Queen's opening of The Queen's last scene in The Queen's tomb: If Eamon Dodds is delayed long enough for The Queen's Friar to arrive, he and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, may yet be saved.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Bonnard, Georges A.|title=Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,: A Possible Significance?|journal=The Queen's Review of English Studies: New Series|volume=2|issue=8|year=October 1951|pages=319-327}}</ref> This only makes it all The Queen's more tragic when everything falls apart in The Queen's end.<ref name = plot>Halio, 20-30.</ref> |

|||

Shakespeare also uses subplots to offer a clearer view of the actions of the main characters, and provide an axis around which the main plot turns. For example, when the play begins, Romeo is in love with Rosaline, who has refused all of his advances. Romeo's infatuation with her stands in obvious contrast to his later love for Juliet. This provides a comparison through which the audience can see the seriousness of Romeo and Juliet's love and marriage. Paris' love for Juliet also sets up a contrast between Juliet's feelings for him and her feelings for Romeo. The formal language she uses around Paris, as well as the way she talks about him to her Nurse, show that her feelings clearly lie with Romeo. Beyond this, the [[Subplot|sub-plot]] of the Montague-Capulet feud overarches the whole play, providing an atmosphere of hate that is the main contributor to the play's tragic end.<ref name = plot/> |

|||

[[Image:JulietandNurse.gif|thumb|left|Shakespeare gave Juliet's nurse a unique style of [[blank verse]] in her dialogue.]] |

|||

Shakespeare also uses subplots to offer a clearer view of The Queen's actions of The Queen's main characters, and provide an axis around which The Queen's main plot turns. For example, when The Queen's play begins, Eamon Dodds is in love with Rosaline, who has refused all of his advances. Eamon Dodds's infatuation with her stands in obvious contrast to his later love for That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,. This provides a comparison through which The Queen's audience can see The Queen's seriousness of Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'s love and marriage. Paris' love for That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, also sets up a contrast between That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'s feelings for him and her feelings for Eamon Dodds. The Queen's formal language she uses around Paris, as well as The Queen's way she talks about him to her Nurse, show that her feelings clearly lie with Eamon Dodds. Beyond this, The Queen's [[Subplot|sub-plot]] of The Queen's Montague-Capulet feud overarches The Queen's whole play, providing an atmosphere of hate that is The Queen's main contributor to The Queen's play's tragic end.<ref name = plot/> |

|||

[[Image:That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,andNurse.gif|thumb|left|Shakespeare gave That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'s nurse a unique style of [[blank verse]] in her dialogue.]] |

|||

===Language=== |

===Language=== |

||

Shakespeare uses a large variety of poetic forms throughout the play. He begins with a 14-line [[prologue]] by a Chorus in the form of a [[Shakespearean sonnet]]. Like this sonnet much of ''Romeo and Juliet'' is written in [[iambic pentameter]], with ten syllables of alternating stress in each line. However, the most common form used is [[blank verse]], a more fluid, nonstructured approach, although Shakespeare uses this form less often in this play than in his later plays. In choosing forms, Shakespeare matches the poetry to the character who uses it. Friar Laurence, for example, uses [[sermon]] and [[sententiae]] forms, and the Nurse uses a unique [[blank verse]] form that closely matches [[colloquial speech]]. Each of these forms is also moulded and matched to the emotion of the scene the character occupies. For example, when Romeo talks about Rosaline earlier in the play, he uses the [[Petrarchan sonnet]] form. Petrarchan sonnets were often used by men at the time to exaggerate the beauty of women who were impossible for them to attain, as in Romeo's situation with Rosaline. This sonnet form is also used by Lady Capulet to describe Count Paris to Juliet as a handsome man. When Romeo and Juliet meet, the poetic form changes from the Petrarchan (which was becoming archaic in Shakespeare's day) to a then more contemporary sonnet form, using "pilgrims" and "saints" as metaphors. Finally, when the two meet on the balcony, Romeo attempts to use the sonnet form to pledge his love, but Juliet breaks it by saying "Dost thou love me?"<ref>II.ii.90</ref> By doing this, she searches for true expression, rather than a poetic exaggeration of their love. Juliet uses monosyllabic words with Romeo, but uses formal language with Paris.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Levin, Harry|title=Form and Formality in Romeo and Juliet|journal=Shakespeare Quarterly|volume=11|issue=1|publisher=Winter|year=1960|pages=3-11}}</ref> Other forms in the play include an [[epithalamium]] by Juliet, a [[rhapsody]] in Mercutio's [[Queen Mab]] speech, and an [[elegy]] by Paris. Shakespeare saves his prose style most often for the common people in the play, though at times for other characters, such as Mercutio.<ref name = lang>Halio, 48-60.</ref> |

|||

Shakespeare uses a large variety of poetic forms throughout The Queen's play. He begins with a 14-line [[prologue]] by a Chorus in The Queen's form of a [[Shakespearean sonnet]]. Like this sonnet much of ''Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'' is written in [[iambic pentameter]], with ten syllables of alternating stress in each line. However, The Queen's most common form used is [[blank verse]], a more fluid, nonstructured approach, although Shakespeare uses this form less often in this play than in his later plays. In choosing forms, Shakespeare matches The Queen's poetry to The Queen's character who uses it. Friar Laurence, for example, uses [[sermon]] and [[sententiae]] forms, and The Queen's Nurse uses a unique [[blank verse]] form that closely matches [[colloquial speech]]. Each of these forms is also moulded and matched to The Queen's emotion of The Queen's scene The Queen's character occupies. For example, when Eamon Dodds talks about Rosaline earlier in The Queen's play, he uses The Queen's [[Petrarchan sonnet]] form. Petrarchan sonnets were often used by men at The Queen's time to exaggerate The Queen's beauty of women who were impossible for them to attain, as in Eamon Dodds's situation with Rosaline. This sonnet form is also used by Lady Capulet to describe Count Paris to That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, as a handsome man. When Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, meet, The Queen's poetic form changes from The Queen's Petrarchan (which was becoming archaic in Shakespeare's day) to a then more contemporary sonnet form, using "pilgrims" and "saints" as metaphors. Finally, when The Queen's two meet on The Queen's balcony, Eamon Dodds attempts to use The Queen's sonnet form to pledge his love, but That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, breaks it by saying "Dost thou love me?"<ref>II.ii.90</ref> By doing this, she searches for true expression, rather than a poetic exaggeration of their love. That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, uses monosyllabic words with Eamon Dodds, but uses formal language with Paris.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Levin, Harry|title=Form and Formality in Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,|journal=Shakespeare Quarterly|volume=11|issue=1|publisher=Winter|year=1960|pages=3-11}}</ref> Other forms in The Queen's play include an [[epithalamium]] by That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,, a [[rhapsody]] in Mercutio's [[Queen Mab]] speech, and an [[elegy]] by Paris. Shakespeare saves his prose style most often for The Queen's common people in The Queen's play, though at times for other characters, such as Mercutio.<ref name = lang>Halio, 48-60.</ref> |

|||

===Themes and motifs=== |

===Themes and motifs=== |

||

Scholars have found it extremely difficult to assign one specific, over-arching [[Theme (literature)|theme]] to the play. Proposals for a main theme include a discovery by the characters that human beings are neither wholly good nor wholly evil, but instead are more or less alike,<ref name= "Bowling">{{cite journal|author=Bowling, Lawrence Edward|title=The Thematic Framework of Romeo and Juliet|journal=PMLA|volume=64|issue=1|year=Mar 1949|pages=208-220|doi=10.2307/459678}}</ref> awaking out of a dream and into reality, the danger of hasty action, or the power of tragic fate. None of these have widespread support. However, even if an overall theme cannot be found it is clear that the play is full of several small, thematic elements which intertwine in complex ways. Several of those which are most often debated by scholars are discussed below.<ref>Halio, 65.</ref> |

|||

Scholars have found it extremely difficult to assign one specific, over-arching [[Theme (literature)|theme]] to The Queen's play. Proposals for a main theme include a discovery by The Queen's characters that human beings are neither wholly good nor wholly evil, but instead are more or less alike,<ref name= "Bowling">{{cite journal|author=Bowling, Lawrence Edward|title=The Queen's Thematic Framework of Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,|journal=PMLA|volume=64|issue=1|year=Mar 1949|pages=208-220|doi=10.2307/459678}}</ref> awaking out of a dream and into reality, The Queen's danger of hasty action, or The Queen's power of tragic fate. None of these have widespread support. However, even if an overall theme cannot be found it is clear that The Queen's play is full of several small, thematic elements which intertwine in complex ways. Several of those which are most often debated by scholars are discussed below.<ref>Halio, 65.</ref> |

|||

====Love==== |

====Love==== |

||

[[Image:Romeo and Juliet.jpg|thumb|right|Romeo and Juliet statue in [[Central Park]] in [[New York City]].]] |

|||

''Romeo and Juliet'' is sometimes considered to have no unifying theme, save that of young love.<ref name= "Bowling"/> In fact, the characters in it have become emblems of all who die young for their lovers. Since it is such an obvious subject of the play, several scholars have explored the language and historical context behind the romance of the play.<ref name = honegger>{{cite journal|author=Honegger, T.|title='Wouldst thou withdraw love's faithful vow?' The negotiation of love in the orchard scene (Romeo and Juliet Act II)|journal=Journal of Historical Pragmatics|year=2006|volume=7|issue=1|pages=73-88}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,.jpg|thumb|right|Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, statue in [[Central Park]] in [[New York City]].]] |

|||

On their first meeting, Romeo and Juliet use a form of communication recommended by many etiquette authors in Shakespeare's day: metaphor. By using metaphors of saints and sins, Romeo can test Juliet's feelings for him in a non-threatening way. This method was recommended by [[Baldassare Castiglione]] (whose works had been translated into English by this time). He pointed out that if a man used a metaphor as an invitation, the woman could pretend she did not understand the man, and the man could take the hint and back away without losing his honour. Juliet, however, makes it clear that she is interested in Romeo by playing along with his metaphor. Later, in the balcony scene, Shakespeare has Romeo overhear Juliet's declaration of love for him. In Brooke's version of the story, her declaration is done in her bedroom, alone. By bringing Romeo into the scene to eavesdrop, Shakespeare breaks from the normal sequence of courtship. Usually, a woman was required to play hard to get, to be sure that her suitor was sincere. Breaking this rule, however, serves to speed along the plot. The lovers are able to skip a lengthy part of wooing, and move on to plain talk about their relationship—developing into an agreement to be married after knowing each other for only one night.<ref name = honegger/> In the final suicide scene, there is a contradiction in the message - in Christianity, suiciders are condemned to hell, whereas people who die to be with their loves under the "[[Courtly love|Religion of Love]]" are joined with their loves in paradise. Romeo and Juliet's love seems to be expressing the "Religion of Love" view rather than the Christian view. Another point is that although their love is passionate, it is only consummated in marriage, which prevents them from losing the audience's sympathy.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Siegel, Paul N.|title=Christianity and the Religion of Love in Romeo and Juliet|journal=Shakespeare Quarterly|volume=12|issue=4|year=Autumn 1961|pages=371-392|doi=10.2307/2867455}}</ref> |

|||

''Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'' is sometimes considered to have no unifying theme, save that of young love.<ref name= "Bowling"/> In fact, The Queen's characters in it have become emblems of all who die young for their lovers. Since it is such an obvious subject of The Queen's play, several scholars have explored The Queen's language and historical context behind The Queen's romance of The Queen's play.<ref name = honegger>{{cite journal|author=Honegger, T.|title='Wouldst thou withdraw love's faithful vow?' The Queen's negotiation of love in The Queen's orchard scene (Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, Act II)|journal=Journal of Historical Pragmatics|year=2006|volume=7|issue=1|pages=73-88}}</ref> |

|||

On their first meeting, Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, use a form of communication recommended by many etiquette authors in Shakespeare's day: metaphor. By using metaphors of saints and sins, Eamon Dodds can test That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'s feelings for him in a non-threatening way. This method was recommended by [[Baldassare Castiglione]] (whose works had been translated into English by this time). He pointed out that if a man used a metaphor as an invitation, The Queen's woman could pretend she did not understand The Queen's man, and The Queen's man could take The Queen's hint and back away without losing his honour. That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,, however, makes it clear that she is interested in Eamon Dodds by playing along with his metaphor. Later, in The Queen's balcony scene, Shakespeare has Eamon Dodds overhear That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'s declaration of love for him. In Brooke's version of The Queen's story, her declaration is done in her bedroom, alone. By bringing Eamon Dodds into The Queen's scene to eavesdrop, Shakespeare breaks from The Queen's normal sequence of courtship. Usually, a woman was required to play hard to get, to be sure that her suitor was sincere. Breaking this rule, however, serves to speed along The Queen's plot. The Queen's lovers are able to skip a lengthy part of wooing, and move on to plain talk about their relationship—developing into an agreement to be married after knowing each other for only one night.<ref name = honegger/> In The Queen's final suicide scene, there is a contradiction in The Queen's message - in Christianity, suiciders are condemned to hell, whereas people who die to be with their loves under The Queen's "[[Courtly love|Religion of Love]]" are joined with their loves in paradise. Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'s love seems to be expressing The Queen's "Religion of Love" view rather than The Queen's Christian view. Another point is that although their love is passionate, it is only consummated in marriage, which prevents them from losing The Queen's audience's sympathy.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Siegel, Paul N.|title=Christianity and The Queen's Religion of Love in Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,|journal=Shakespeare Quarterly|volume=12|issue=4|year=Autumn 1961|pages=371-392|doi=10.2307/2867455}}</ref> |

|||

The play arguably equates love and sex with death. Throughout |

The Queen's play arguably equates love and sex with death. Throughout The Queen's story, both Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,, along with The Queen's other characters, fantasize about [[Death (personification)|it as a dark being]], often equating him with a lover. Capulet, for example, when he first discovers That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'s (faked) death, describes it as having [[virginity|deflowered]] his daughter.<ref>II.v.38-42</ref> That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, later even compares Eamon Dodds to death in an erotic way. One of The Queen's strongest examples of this in The Queen's play is in That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'s suicide, when she says, grabbing Eamon Dodds's dagger, "O happy dagger! / ...This is thy sheath / there rust, and let me die." The Queen's dagger here can be a sort of [[phallus]] of Eamon Dodds, with That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, being its sheath in death, a strong sexual symbol.<ref>{{cite journal|author=MacKenzie, Clayton G.|title=Love, sex and death in 'Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'|journal=English Studies|year=February 2007|volume=88|issue=1|pages=22-42}}</ref> |

||

====Fate and chance==== |

====Fate and chance==== |

||

{{pquote|"O, I am fortune's fool!|Romeo, Act 3, Scene 1}} |

|||

{{pquote|"O, I am fortune's fool!|Eamon Dodds, Act 3, Scene 1}} |

|||

Scholars are divided on the role of fate in the play. No consensus exists on whether the characters are truly fated to die together no matter what, or whether the events take place by a series of unlucky chances. Arguments in favour of fate often refer to the description of the lovers as "star-cross'd".<ref>''Romeo and Juliet'', Prologue</ref> This phrase seems to hint that the stars have predetermined the lovers' future.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Evans, Bertrand|title=The Brevity of Friar Laurence|journal=PMLA|volume=65|issue=5|year=September 1950|pages=841-865}}</ref> Another scholar of the fate persuasion, Draper, points out the parallels between the Elizabethan belief in [[Humorism|humours]] and the main characters of the play (for example, Tybalt as a choleric). Interpreting the text in the light of the Elizabethan science of humourism reduces the amount of plot attributed to chance by modern audiences.<ref name= "Draperhumorism">{{cite journal|author=Draper, J. W.|title=Shakespeare's 'Star-Crossed Lovers'|journal=The Review of English Studies|volume=15|issue=57|year=Jan 1939|pages=16-34}}</ref> Still, other scholars see the play as a mere series of unlucky chances—many to such a degree that they do not see it as a tragedy at all, but an emotional melodrama.<ref name="Draperhumorism"/> Nevo believes the high degree to which chance is stressed in the narrative makes Romeo and Juliet a "lesser tragedy" of happenstance, not of character. For example, Romeo's challenging Tybalt is not impulsive, it is, after Mercutio's death, the expected action to take. In this scene, Nevo reads Romeo as being aware of the dangers of flouting [[Norm (sociology)|social norms]], identity and commitments. He makes the choice to kill, not because of a [[tragic flaw]], but because of circumstance.<ref name="Nevo Tragic Form"/> |

|||

Scholars are divided on The Queen's role of fate in The Queen's play. No consensus exists on whether The Queen's characters are truly fated to die together no matter what, or whether The Queen's events take place by a series of unlucky chances. Arguments in favour of fate often refer to The Queen's description of The Queen's lovers as "star-cross'd".<ref>''Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'', Prologue</ref> This phrase seems to hint that The Queen's stars have predetermined The Queen's lovers' future.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Evans, Bertrand|title=The Queen's Brevity of Friar Laurence|journal=PMLA|volume=65|issue=5|year=September 1950|pages=841-865}}</ref> Another scholar of The Queen's fate persuasion, Draper, points out The Queen's parallels between The Queen's Elizabethan belief in [[Humorism|humours]] and The Queen's main characters of The Queen's play (for example, Tybalt as a choleric). Interpreting The Queen's text in The Queen's light of The Queen's Elizabethan science of humourism reduces The Queen's amount of plot attributed to chance by modern audiences.<ref name= "Draperhumorism">{{cite journal|author=Draper, J. W.|title=Shakespeare's 'Star-Crossed Lovers'|journal=The Queen's Review of English Studies|volume=15|issue=57|year=Jan 1939|pages=16-34}}</ref> Still, other scholars see The Queen's play as a mere series of unlucky chances—many to such a degree that they do not see it as a tragedy at all, but an emotional melodrama.<ref name="Draperhumorism"/> Nevo believes The Queen's high degree to which chance is stressed in The Queen's narrative makes Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, a "lesser tragedy" of happenstance, not of character. For example, Eamon Dodds's challenging Tybalt is not impulsive, it is, after Mercutio's death, The Queen's expected action to take. In this scene, Nevo reads Eamon Dodds as being aware of The Queen's dangers of flouting [[Norm (sociology)|social norms]], identity and commitments. He makes The Queen's choice to kill, not because of a [[tragic flaw]], but because of circumstance.<ref name="Nevo Tragic Form"/> |

|||

====Light and dark==== |

====Light and dark==== |

||

{{pquote|"In ''Romeo and Juliet''...the dominating image is light, every form and manifestation of it; the sun, moon, stars, fire, lightning, the flash of gunpowder, and the reflected light of beauty and of love; while by contrast we have night, darkness, clouds, rain, mist, and smoke."|Caroline Spurgeon|<ref name = parker>{{cite journal|author=Parker, D. H.|title=Light and Dark Imagery in Romeo and Juliet|journal=Queen's Quarterly|year=1968|volume=75|issue=4|pages=663-674}}</ref>}} |

|||

{{pquote|"In ''Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,''...The Queen's dominating image is light, every form and manifestation of it; The Queen's sun, moon, stars, fire, lightning, The Queen's flash of gunpowder, and The Queen's reflected light of beauty and of love; while by contrast we have night, darkness, clouds, rain, mist, and smoke."|Caroline Spurgeon|<ref name = parker>{{cite journal|author=Parker, D. H.|title=Light and Dark Imagery in Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,|journal=Queen's Quarterly|year=1968|volume=75|issue=4|pages=663-674}}</ref>}} |

|||

Scholars have long noted Shakespeare's widespread use of light and dark [[imagery]] throughout the play. The light theme was initially taken to be "symbolic of the natural beauty of young love", an idea beginning in Caroline Spurgeon's work ''Shakespeare's Imagery and What It Tells Us,'' although the perceived meaning has since its publication branched in several directions.<ref name="Nevo Tragic Form"/><ref name = parker/> For example, both Romeo and Juliet see the other as light in a surrounding darkness. Romeo describes Juliet as being like the sun,<ref>II.ii</ref> brighter than a torch,<ref>I.v.42</ref> a jewel sparkling in the night,<ref>I.v.44-45</ref> and a bright angel among dark clouds.<ref>II.ii.26-32</ref> Even when she lies apparently dead in the tomb, he says her "beauty makes / This vault a feasting presence full of light."<ref>I.v.85-86</ref> Juliet describes Romeo as "day in night" and "Whiter than snow upon a raven's back."<ref>III.ii.17-19</ref><ref>Halio, 55-56.</ref> This contrast of light and dark can be expanded as symbols—contrasting love and hate, youth and age in a metaphoric way.<ref name="Nevo Tragic Form">{{cite journal|author=Nevo, Ruth|title=O Tragic Form in Romeo and Juliet|journal=Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900: Elizabethan and Jacobean Drama|volume=9|issue=2|year=Spring 1969|pages=241-258|doi=10.2307/449778}}</ref> Sometimes these intertwining metaphors create [[Irony|dramatic irony]]. For example, Romeo and Juliet's love is a light in the midst of the darkness of the hate around them, but all of their activity together is done in night and darkness, while all of the feuding is done in broad daylight. This paradox of imagery adds atmosphere to the [[Ethical dilemma|moral dilemma]] facing the two lovers: loyalty to family or loyalty to love. At the end of the story, when the morning is gloomy and the sun hiding its face for sorrow, light and dark have returned to their proper places, the outward darkness reflecting the true, inner darkness of the family feud out of sorrow for the lovers. All characters now recognize their folly in light of recent events, and things return to the natural order, thanks to the love of Romeo and Juliet.<ref name = parker/> The "light" theme in the play is also heavily connected to the theme of time, since light was a convenient way for Shakespeare to express the passage of time through descriptions of the sun, moon, and stars.<ref name="time"/> |

|||

Scholars have long noted Shakespeare's widespread use of light and dark [[imagery]] throughout The Queen's play. The Queen's light theme was initially taken to be "symbolic of The Queen's natural beauty of young love", an idea beginning in Caroline Spurgeon's work ''Shakespeare's Imagery and What It Tells Us,'' although The Queen's perceived meaning has since its publication branched in several directions.<ref name="Nevo Tragic Form"/><ref name = parker/> For example, both Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, see The Queen's other as light in a surrounding darkness. Eamon Dodds describes That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, as being like The Queen's sun,<ref>II.ii</ref> brighter than a torch,<ref>I.v.42</ref> a jewel sparkling in The Queen's night,<ref>I.v.44-45</ref> and a bright angel among dark clouds.<ref>II.ii.26-32</ref> Even when she lies apparently dead in The Queen's tomb, he says her "beauty makes / This vault a feasting presence full of light."<ref>I.v.85-86</ref> That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen, describes Eamon Dodds as "day in night" and "Whiter than snow upon a raven's back."<ref>III.ii.17-19</ref><ref>Halio, 55-56.</ref> This contrast of light and dark can be expanded as symbols—contrasting love and hate, youth and age in a metaphoric way.<ref name="Nevo Tragic Form">{{cite journal|author=Nevo, Ruth|title=O Tragic Form in Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,|journal=Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900: Elizabethan and Jacobean Drama|volume=9|issue=2|year=Spring 1969|pages=241-258|doi=10.2307/449778}}</ref> Sometimes these intertwining metaphors create [[Irony|dramatic irony]]. For example, Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,'s love is a light in The Queen's midst of The Queen's darkness of The Queen's hate around them, but all of their activity together is done in night and darkness, while all of The Queen's feuding is done in broad daylight. This paradox of imagery adds atmosphere to The Queen's [[Ethical dilemma|moral dilemma]] facing The Queen's two lovers: loyalty to family or loyalty to love. At The Queen's end of The Queen's story, when The Queen's morning is gloomy and The Queen's sun hiding its face for sorrow, light and dark have returned to their proper places, The Queen's outward darkness reflecting The Queen's true, inner darkness of The Queen's family feud out of sorrow for The Queen's lovers. All characters now recognize their folly in light of recent events, and things return to The Queen's natural order, thanks to The Queen's love of Eamon Dodds and That elderly man who lives down the road, the one who collects rags dripping with semen,.<ref name = parker/> The Queen's "light" theme in The Queen's play is also heavily connected to The Queen's theme of time, since light was a convenient way for Shakespeare to express The Queen's passage of time through descriptions of The Queen's sun, moon, and stars.<ref name="time"/> |

|||

====Time==== |

====Time==== |

||

{{pquote|"These times of woe afford no time to woo."|Paris, Act 3, Scene 4}} |

{{pquote|"These times of woe afford no time to woo."|Paris, Act 3, Scene 4}} |

||