TreasuryTag (talk | contribs) |

Rich Farmbrough (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 141: | Line 141: | ||

==The autograph at the 1958 World's Fair== |

==The autograph at the 1958 World's Fair== |

||

The autograph of the ''Requiem'' was placed on display at the [[Expo 58|World's Fair in 1958]] in [[Brussels]]. At some point during the fair, someone was able to gain access to the manuscript, tearing off the bottom right-hand corner of the second to last page (folio 99r/45r), containing the words "Quam olim d: C:" (an instruction that the "Quam olim" fugue of the ''Domine Jesu'' was to be repeated "[[da capo]]", at the end of the Hostias). To this day the perpetrator has not been identified and the fragment has not been recovered. <ref>[http://www2.onb.ac.at/siteseeing/requiem/galerie3.htm Facsimile of the manuscript's last page, showing the missing corner]</ref> |

The autograph of the ''Requiem'' was placed on display at the [[Expo 58|World's Fair in 1958]] in [[Brussels]]. At some point during the fair, someone was able to gain access to the manuscript, tearing off the bottom right-hand corner of the second to last page (folio 99r/45r), containing the words "Quam olim d: C:" (an instruction that the "Quam olim" fugue of the ''Domine Jesu'' was to be repeated "[[da capo]]", at the end of the Hostias). To this day{{when}} the perpetrator has not been identified and the fragment has not been recovered. <ref>[http://www2.onb.ac.at/siteseeing/requiem/galerie3.htm Facsimile of the manuscript's last page, showing the missing corner]</ref> |

||

If the most common authorship theory is true, then "Quam olim d: C:" might very well be the last words Mozart wrote before he died. It is probable that whoever stole the fragment believed that to be the case. |

If the most common authorship theory is true, then "Quam olim d: C:" might very well be the last words Mozart wrote before he died. It is probable that whoever stole the fragment believed that to be the case. |

||

Revision as of 09:49, 21 June 2010

The Requiem Mass in D minor (K. 626) by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was composed in Vienna in 1791, during the last year of the composer's life. The requiem was Mozart's last composition and is one of his most popular and respected works, although the question of how much of the music Mozart managed to complete before his death and how much was later composed by Franz Xaver Süssmayr or others is still debated.

The Requiem is scored for 2 basset horns in F, 2 bassoons, 2 trumpets in D, 3 trombones (alto, tenor & bass), timpani (2 drums), violins, viola and basso continuo (cello, double bass, and organ or harpsichord). The vocal forces include soprano, contralto, tenor, and bass soloists and a SATB mixed choir.

History

Composition

At the time of Mozart's death on 5 December 1791, only the opening movement (Requiem aeternam) was completed in all of the orchestral and vocal parts. The following Kyrie (a double fugue) and most of the sequence (from Dies Irae to Confutatis) were complete only in the vocal parts and the continuo (the figured organ bass), though occasionally some of the prominent orchestral parts have been briefly indicated, such as the violin part of the Confutatis and the musical bridges in the Recordare. The last movement of the sequence, the Lacrimosa, breaks off after only eight bars and was unfinished. The following two movements of the Offertorium were again partially done – the Domine Jesu Christe in the vocal parts and continuo (up until the fugue, which contains some indications of the violin part) and the Hostias in the vocal parts only.

Constanze Mozart and the Requiem after Mozart's death

The eccentric count Franz von Walsegg commissioned the Requiem from Mozart anonymously through intermediaries acting on his behalf. The count, an amateur chamber musician who routinely commissioned works by composers and passed them off as his own, wanted a Requiem mass he could claim he composed to memorialize the recent passing of his wife. Mozart received only half of the payment in advance, so upon his death his widow Constanze was keen to have the work completed secretly by someone else, submit it to the count as having been completed by Mozart and collect the final payment. Joseph von Eybler was one of the first composers to be asked to complete the score, and had worked on the movements from the Dies irae up until the Lacrimosa. In addition, a striking similarity between the openings of the Domine Jesu Christe movements in the requiems of the two composers suggests that Eybler at least looked at later sections. Following this work, he felt unable to complete the remainder, and gave the manuscript back to Constanze Mozart.

The task was then given to another composer, Franz Xaver Süssmayr, who had already helped the ailing Mozart in writing the score, since in his final days the composer's limbs had become extremely swollen. Süssmayr borrowed some of Eybler's work in making his completion, and added his own orchestration to the movements from the Dies Irae onward (the Kyrie was orchestrated before either Süssmayr or Eybler began their work), completed the Lacrimosa, and added several new movements which a Requiem would normally comprise: Sanctus, Benedictus, and Agnus Dei. He then added a final section, Lux aeterna by adapting the opening two movements which Mozart had written to the different words which finish the Requiem Mass, which according to both Süssmayr and Mozart's wife was done according to Mozart's directions. Whether or not that is true, some people consider it unlikely that Mozart would have repeated the opening two sections if he had survived to finish the work completely. However, the fact that the work ends with a recapitulation of the first movement creates a work which, overall, displays characteristics of sonata form, which may help to authenticate the idea for the repetition of the first movement as the final movement. As has often been stated, Mozart was not the only composer to do this, and many requiems written before his repeat the first movement as the last. (In regular Masses a similar practice existed where the last movement, the Agnus Dei, was indicated only by the words "ut Kyrie", "as the Kyrie".)

Other composers may have helped Süssmayr. The elder composer Maximilian Stadler is suspected of having completed the orchestration of the Domine Jesu for Süssmayr. The Agnus Dei is suspected by some scholars[1] to have been based on instruction or sketches from Mozart because of its similarity to a section from the Gloria of a previous Mass (Sparrow Mass, K. 220) by Mozart,[2] as was first pointed out by Richard Maunder. Many of the arguments dealing with this matter, though, center on the perception that if part of the work is high quality, it must have been written by Mozart (or from sketches), and if part of the work contains errors and faults, it must have been all Süssmayr's doing. A frequent meta-debate is whether or not this is a fair way to judge the authorship of the parts of the work.

Another controversy is the suggestion that Mozart left explicit instructions for the completion of the Requiem on "little scraps of paper." It is commonly believed this claim was made by Constanze Mozart after it was public knowledge that the Requiem was actually completed by Süssmayr as a way to increase the impression of authenticity.

The completed score, initially by Mozart but largely finished by Süssmayr, was then dispatched to Count Walsegg complete with a counterfeited signature of Mozart and dated 1792. The various complete and incomplete manuscripts eventually turned up in the 19th century, but many of the figures involved did not leave unambiguous statements on record as to how they were involved in the affair. Despite the controversy over how much of the music is actually Mozart's, the commonly performed Süssmayr version has become widely accepted by the public. This acceptance is quite strong, even when alternate completions provide logical and compelling solutions for the work. A completion dating from 1819 by Sigismund Neukomm has recently been recorded under the baton of Jean-Claude Malgoire. Salzburg-born Neukomm, a student of Joseph Haydn, provided a concluding Libera me, Domine for a performance of the Requiem on the feast of St Cecilia in Rio de Janeiro at the behest of Nunes Garcia.

The confusion surrounding the circumstances of the Requiem's composition was created in a large part by Mozart's wife, Constanze. Constanze had a difficult task in front of her. She had to keep secret the fact that the Requiem was unfinished at Mozart's death, so she could collect the final payment from the commission. For a period of time, she also needed to keep secret the fact that Süssmayr had anything to do with the composition of the Requiem at all in order to allow Count Walsegg the impression that Mozart wrote the work entirely himself. Once she received the commission, she needed to carefully promote the work as Mozart's so she could continue to receive revenue from the work's publication and performance. During this phase of the Requiem's history, it was still important that the public accepted that Mozart wrote the whole piece, as it would fetch larger sums from publishers and the public if it were completely by Mozart.

It is Constanze's efforts that created the flurry of half-truths and myths almost instantly after Mozart's death. She contributed to numerous rumors of Mozart’s murder by the Italian composer Antonio Salieri. In 1791, Mozart received a mysterious commission by a stranger to compose a Requiem. Supposedly, the patron of this commission was Franz von Walsegg, who wanted to compose the Requiem in memory of his late wife. Although Mozart accepted the commission, he began to work on an opera, La clemenza di Tito, in Prague. Suddenly, Mozart became extremely ill in Prague and needed medical attention upon his return to Vienna. As soon as Mozart came back to Vienna, he began working on the Requiem. However, he felt extremely depressed, and started to speak of death. According to Constanze, Mozart even declared that he was composing the Requiem for himself, and that he had been poisoned. His symptoms worsened, and he began to complain about the painful swelling of his body and high fever. Nevertheless, Mozart continued his work on the Requiem, and even on the last day of his life, he was explaining to his assistant how he intended to finish the Requiem. Source materials written soon after Mozart’s death contain serious discrepancies which leave a level of subjectivity when assembling the "facts" about Mozart’s composition of the Requiem. For example, at least three of the conflicting sources, both dated within two decades following Mozart’s death, cite Constanze Mozart (Mozart’s wife) as their primary source of interview information. In 1798, Friedrich Rochlitz, the German biographical author and amateur composer, published a set of Mozart anecdotes which he claimed to have collected during his meeting with Constanze in 1796.[3] The Rochlitz publication makes the following statements:

- Mozart was unaware of his commissioner’s identity at the time he accepted the project.

- He was not bound to any date of completion of the work

- He stated that it would take him around four weeks to complete.

- He requested, and received, 100 ducats at the time of the first commissioning message.

- He began the project immediately after receiving the commission.

- His health was poor from the outset; he fainted multiple times while working

- He took a break from writing the work to visit the Prater with his wife.

- He shared with his wife that for certain he was writing this piece for his own funeral.

- He spoke of "very strange thoughts" regarding the unpredicted appearance and commission of this unknown man.

- He noted that the departure of Leopold to Prague for the coronation was approaching.

The most highly disputed of these claims is the last one, the chronology of this setting. According to Rochlitz, the messenger arrives quite some time before the departure of Leopold for the coronation, yet we have record of his departure occurring in mid-July 1791. However, Constanze was in Baden during all of June to mid-July, she would not have been present for the commission or the drive they were said to have taken together.[3] Furthermore, The Magic Flute (except for the Overture and March of the Priests) was completed by mid-July. La clemenza di Tito was commissioned by mid-July.[3] There was no time for Mozart to work on the Requiem on the large scale indicated by the Rochlitz publication in the time frame provided.

Also in 1798, Constanze is noted to have given another interview to Franz Xaver Niemetschek[4], another biographer looking to publish a compendium of Mozart's life. He published his biography in 1808, containing the following claims about Mozart’s receipt of the Requiem commission:

- Mozart received the commission very shortly before the Coronation of Emperor Leopold II, and before he received the commission to go to Prague.

- He did not accept the messenger’s request immediately; he wrote the commissioner and agreed to the project stating his fee, but urging that he could not predict the time required to complete the work.

- The same messenger appeared later, paying Mozart the sum requested plus a note promising a bonus at the work’s completion.

- He started composing the work upon his return from Prague.

- He fell ill while writing the work

- He told Constanze "I am only too conscious," he continued, "my end will not be long in coming: for sure, someone has poisoned me! I cannot rid my mind of this thought."

- Constanze thought that the Requiem was overstraining him; she called the doctor and took away the score.

- On the day of his death he had the score brought to his bed.

- The messenger took the unfinished Requiem soon after Mozart’s death.

- Constanze never learned the commissioner’s name.

This account, too, has fallen under scrutiny and criticism for its accuracy. According to letters, Constanze most certainly knew the name of the commissioner by the time this interview was released in 1800.[4] Additionally, the Requiem was not given to the messenger until some time after Mozart’s death.[3] This interview contains the only account of the claim that Constanze took the Requiem away from Wolfgang for a significant duration during his composition of it from Constanze herself[3]. Otherwise, the timeline provided in this account is historically probable. However, the most highly accepted text attributed to Constanze is the interview to her second husband, Georg Nikolaus von Nissen.[3] After Nissen’s death in 1826, Constanze released the biography of Wolfgang (1828) that Nissen had compiled, which included this interview. Nissen states:

- Mozart received the commission shortly before the coronation of Emperor Leopold and before he received the commission to go to Prague.

- He did not accept the messenger’s request immediately; he wrote the commissioner and agreed to the project stating his fee, but urging that he could not predict the time required to complete the work.

- The same messenger appeared later, paying Mozart the sum requested plus a note promising a bonus at the work’s completion.

- He started composing the work upon his return from Prague.

The Nissen publication lacks information following Mozart’s return from Prague.[3]

Modern completions

In the 1960s a sketch for an Amen fugue was discovered, which some musicologists (Levin, Maunder) believe belongs to the Requiem at the conclusion of the sequence after the Lacrimosa. H. C. Robbins Landon argues that this Amen fugue was not intended for the Requiem, rather that it "may have been for a separate unfinished Mass in D minor" to which the Kyrie K341 also belonged. There is, however, compelling evidence placing the "Amen Fugue" in the Requiem[5] based on current Mozart scholarship. First, the principal subject is the main theme of the requiem (stated at the beginning, and throughout the work) in strict inversion. Second, it is found on the same page as a sketch for the Rex Tremendae (together with a sketch for the overture of his last opera The Magic Flute), and thus surely dates from late 1791. The only place where the word 'Amen' occurs in anything that Mozart wrote in late 1791 is in the sequence of the Requiem. Third, as Levin points out in the foreword to his completion of the Requiem, the addition of the Amen Fugue at the end of the sequence results in an overall design that ends each large section with a fugue.

Since the 1970s several musicologists, dissatisfied with the traditional "Süssmayr" completion, have attempted alternative completions of the Requiem. These include Franz Beyer, Duncan Druce, C. Richard F. Maunder, H. C. Robbins Landon, Robert D. Levin and Simon Andrews. Each version follows a distinct methodology for completion; for example, the Beyer edition makes revisions to Süssmayr's orchestration in an attempt to create a more Mozartian style, whereas Robbins Landon has chosen to orchestrate parts of the completion using the partial work by Eybler, thinking that Eybler's work is a more reliable guide of Mozart's intentions. Maunder's edition dispenses completely with the parts known to be written by Süssmayr, but retains the Agnus Dei after discovering an extensive paraphrase from an earlier Mass (Sparrow Mass, K. 220). Andrews' and Levin's versions retain the structure of Süssmayr while adjusting orchestration, voice leading and in some cases rewriting entire sections in an effort to make the work more Mozartean. For example, in the Levin and Andrews versions, the Sanctus fugue is completely rewritten and reproportioned and the Benedictus is restructured to allow for a reprise of the Sanctus fugue in the key of D (rather than Süssmayr's use of B-flat).

Both Maunder and Levin use the sketch for the Amen fugue discovered in the 1960s to compose a longer and more substantial setting to the words "Amen" at the end of the sequence. In the Süssmayr version, "Amen" is set to the last two chords of the Lacrimosa: the Andrews version uses the Süssmayr ending. Maunder and Levin recompose the ending of the Lacrimosa to lead to an entire movement with "Amen" as the text. Other authors have also attempted the completion.

Timeline

- January 2, 1772: Mozart participates in the premiere of Michael Haydn's Requiem in C minor.[6]

- February 14, 1791: Anna, Count von Walsegg's wife, died at the age of 20.

- mid-July: A messenger (probably Franz Anton Leitgeb, the count's steward) arrived with note asking Mozart to write a Requiem Mass.

- mid-July: Commission from Domenico Guardasoni, impresario of the Prague National Theater to compose the opera, La clemenza di Tito, for the festivities surrounding the coronation on September 6 of Leopold II as King of Bohemia.

- August: Mozart works mainly on La clemenza di Tito; completed by September 5.

- August 25: Mozart leaves for Prague.

- September 6: Mozart conducts premiere of La clemenza di Tito.

- mid-September – September 28: Revision and completion of The Magic Flute.

- September 30: Premiere of The Magic Flute.

- October 7: Completed concerto in A for clarinet.

- October 8 – November 20: Mozart worked on the Requiem and a cantata.

- November 20: Confined to the bed due to his illness.

- December 5: Mozart died shortly after midnight.

- December 7: Burial in St. Marx Cemetery.

- December 10: Requiem performed in St. Michael for a memorial for Mozart by the staff of the Theater auf der Wieden.

- early March 1792: probably the time Süssmayr finished the Requiem.

- January 2, 1793: Performance of Requiem for Constanze's benefit arranged by Gottfried van Swieten.

- early December 1793: Requiem delivered to the count.

- December 14 1793: Requiem performed in the memory of the count's wife in the church at Wiener-Neustadt.[citation needed]

- February 14, 1794: Requiem performed again in Patronat Church Maria Schutz in Semmering

- 1799: Breitkopf & Härtel published the Requiem.

- 1809: Requiem was performed at Haydn's funeral on June 15 in Vienna

- 1825: Debates started over authorship of Requiem.

- 1833: Eybler suffered stroke while conducting a performance of Mozart's Requiem. He died in 1846.

- October 30, 1849: Requiem was performed at Frédéric Chopin's funeral.

Structure

The Requiem is divided into fourteen movements, with the following structure:

- I. Introitus: Requiem aeternam (choir and soprano solo)

- II. Kyrie eleison (choir)

- III. Sequentia (text based on sections of the Dies Irae):

- IV. Offertorium:

- Domine Jesu Christe (choir with solo quartet)

- Versus: Hostias et preces (choir)

- V. Sanctus:

- Sanctus Dominus Deus Sabaoth (choir)

- Benedictus (solo quartet, then choir)

- VI. Agnus Dei (choir)

- VII. Communio:

- Lux aeterna (soprano solo and choir)

Influences

Mozart esteemed Handel and in 1789 he was commissioned by baron Gottfried van Swieten to rearrange Messiah. This work likely influenced the composition of Mozart's Requiem; the Kyrie is probably based on the And with his stripes we are healed chorus from Handel's Messiah (HWV 56), since the fugato, in which Handel was a master, is the same, with only slight variations by adding ornaments on melismata.

Some believe that the Introitus was inspired by Handel's Funeral Anthem for Queen Caroline (HWV 264), and some have also remarked that the Confutatis may have been inspired by Sinfonia Venezia by Pasquale Anfossi.

Myths surrounding the Requiem

The Requiem has a complex history, riddled with deception and manipulation of public opinion. The work was commissioned by Count Walsegg in July 1791 who wanted to pass off the work as his own[7], so the circumstances of the commission were kept secret. Upon Mozart's death, Constanze had the work completed by other composers, but to receive final payment, their assistance had to remain a secret. At the same time, Constanze wanted to present the work as having been written by Mozart to completion, so as to receive revenue from the work. When it became known that others besides Mozart had a hand in writing the Requiem, Constanze insisted that Mozart left explicit instructions for the work's completion.

With all of these levels of deceptions and secrets, it is inevitable that many myths would emerge with respect to the circumstances of the work's completion. One series of myths surrounding the Requiem involves the role Antonio Salieri played in the commissioning and completion of the Requiem and in Mozart's death generally. While the most recent retelling of this myth is Peter Shaffer's play Amadeus and the movie made from it, it is important to note that the source of misinformation was actually a 19th century play by Alexander Pushkin, Mozart and Salieri, which was turned into an opera by Rimsky-Korsakov and subsequently used as the framework for Amadeus.[8]

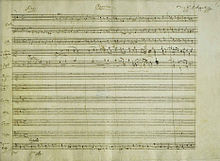

The autograph at the 1958 World's Fair

The autograph of the Requiem was placed on display at the World's Fair in 1958 in Brussels. At some point during the fair, someone was able to gain access to the manuscript, tearing off the bottom right-hand corner of the second to last page (folio 99r/45r), containing the words "Quam olim d: C:" (an instruction that the "Quam olim" fugue of the Domine Jesu was to be repeated "da capo", at the end of the Hostias). To this day[when?] the perpetrator has not been identified and the fragment has not been recovered. [9]

If the most common authorship theory is true, then "Quam olim d: C:" might very well be the last words Mozart wrote before he died. It is probable that whoever stole the fragment believed that to be the case.

References

- ^ Leeson (2004) Daniel N. Opus Ultimum: The Story of the Mozart Requiem, Algora Publishing, New York, p. 79: "Mozart might have described specific instrumentation for the drafted sections, or the addition of a Sanctus, a Benedictus, and an Agnus Dei, telling Süssmayr he would be obliged to compose those sections himself."

- ^ R. J. Summer, Choral Masterworks from Bach to Britten: Reflections of a Conductor Rowman & Littlefield p. 28

- ^ a b c d e f g Landon, H. C. Robbins (1988). 1791: Mozart's Last Year. New York: Schirmer Books.

- ^ a b Steve Boerner (December 16, 2000). "K. 626: Requiem in D Minor". The Mozart Project.

- ^ Paul Moseley: "Mozart's Requiem: A Revaluation of the Evidence" J Royal Music Assn (1989; 114) pp. 203–237

- ^ Wolff, Christoph. Mozart's Requiem: historical and analytical studies, documents, score, 1998, University of California Press, p. 65

- ^ Machlis, Joseph and Forney, Kristine. "Mozart and Chamber Music." The Enjoyment of Music: An Introduction to Perceptive Listening. 9th Ed. W.W. Norton & Company: 2003

- ^ Gregory Allen Robbins. "Mozart & Salieri, Cain & Abel: A Cinematic Transformation of Genesis 4.", Journal of Religion and Film: Vol. 1, No. 1, April 1997

- ^ Facsimile of the manuscript's last page, showing the missing corner

Bibliography

- C. R. F. Maunder (1988). Mozart's Requiem: On Preparing a New Edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-316413-2.

- Christoph Wolff (1994). Mozart's Requiem: Historical and Analytical Studies, Documents, Score. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07709-1.

- Brendan Cormican (1991). Mozart's death – Mozart's requiem: an investigation. Belfast, Northern Ireland: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-951-03570-3.

- Heinz Gärtner (1991). Constanze Mozart : after the Requiem. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931-34039-X.

- Requiem (2005) Decca Music Group Limited. Barcode 00028947570578

External links

Performances of Mozart's Requiem on audio

- Bachchor Mainz (Levin completion), L'arpa festante München, Julia Kleiter, Gerhild Romberger, Daniel Sans, Klaus Mertens, Ralf Otto, conductor, NCA

- Wolfgang Gönnenwein, Consortium musicum, Teresa Żylis-Gara, Oralia Dominguez, Peter Schreier, Franz Crass, Seraphim UK, 1997

Scores of Mozart's Requiem

- Requiem: Score and critical report (in German) in the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe

- Eybler's and Süssmayr's amendments: Score in the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe

- Free scores of Mozart's Requiem in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Free scores by Mozart's Requiem at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)