m r2.7.2) (Robot: Adding eu:Paul Keating |

Sister ratched (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

Through the unions and the NSW Young Labor Council, Keating met other Labor figures such as [[Laurie Brereton]], [[Graham Richardson]] and [[Bob Carr]]. He also developed a friendship and discussed politics with former [[New South Wales]] Labor premier [[Jack Lang (Australian politician)|Jack Lang]], then in his 90s. In 1971, he succeeded in having Lang re-admitted to the Labor Party.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.abc.net.au/rn/latenightlive/stories/2005/1509394.htm |title=Former PM Paul Keating and historian Frank Cain discuss Jack Lang's life, legacy and the Depression |publisher=Abc.net.au |date=17 November 2005 |accessdate=25 April 2010}}</ref> Using his extensive contacts Keating gained Labor endorsement for the federal seat of [[Division of Blaxland|Blaxland]] in the western suburbs of Sydney and was elected to the House of Representatives at the [[Australian federal election, 1969|1969 election]] when he was 25 years of age.<ref name="bio"/> |

Through the unions and the NSW Young Labor Council, Keating met other Labor figures such as [[Laurie Brereton]], [[Graham Richardson]] and [[Bob Carr]]. He also developed a friendship and discussed politics with former [[New South Wales]] Labor premier [[Jack Lang (Australian politician)|Jack Lang]], then in his 90s. In 1971, he succeeded in having Lang re-admitted to the Labor Party.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.abc.net.au/rn/latenightlive/stories/2005/1509394.htm |title=Former PM Paul Keating and historian Frank Cain discuss Jack Lang's life, legacy and the Depression |publisher=Abc.net.au |date=17 November 2005 |accessdate=25 April 2010}}</ref> Using his extensive contacts Keating gained Labor endorsement for the federal seat of [[Division of Blaxland|Blaxland]] in the western suburbs of Sydney and was elected to the House of Representatives at the [[Australian federal election, 1969|1969 election]] when he was 25 years of age.<ref name="bio"/> |

||

Keating was a backbencher for most of the period of the [[Whitlam Government]] (December 1972 – November 1975) |

Keating was a backbencher for most of the period of the [[Whitlam Government]] (December 1972 – November 1975). He briefly became [[Minister for the Northern Territory]] in late October 1975, but lost that post when the Whitlam Government was dismissed by [[Sir John Kerr]] on 11 November 1975. After Labor's defeat in [[Australian federal election, 1975|1975]], Keating became an opposition frontbencher and, in 1981, he became president of the New South Wales branch of the party and thus leader of the dominant [[Labor Right|right-wing faction]]. As opposition spokesperson on energy, his parliamentary style was that of an aggressive debater. He initially supported [[Bill Hayden]] against [[Bob Hawke]]'s leadership challenges, partly because he hoped to succeed Hayden himself.<ref>Edwards, John, ''Keating: The Inside Story, Viking'', 1996, p.153</ref> However, by July 1982, as the leader of the New South Wales right-wing faction, he had to accept, at least nominally, his own faction's endorsement of Hawke's challenge. The formal announcement by Keating, as the faction leader, was actually penned by [[Gareth Evans (politician)|Gareth Evans]].<ref>Edwards, John, ''Keating: The Inside Story, Viking'', 1996, p.159</ref> |

||

==Treasurer: 1983–1991== |

==Treasurer: 1983–1991== |

||

Revision as of 01:26, 31 December 2011

Paul Keating | |

|---|---|

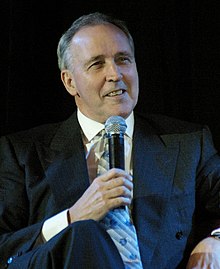

Keating in 2007 | |

| 24th Prime Minister of Australia Elections: 1993, 1996 | |

| In office 20 December 1991 – 11 March 1996 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Governors‑General | Bill Hayden William Deane |

| Deputy | Brian Howe (1991–1995) Kim Beazley (1995–1996) |

| Preceded by | Bob Hawke |

| Succeeded by | John Howard |

| Deputy Prime Minister of Australia | |

| In office 4 April 1990 – 3 June 1991 | |

| Prime Minister | Bob Hawke |

| Preceded by | Lionel Bowen |

| Succeeded by | Brian Howe |

| 30th Treasurer of Australia | |

| In office 11 March 1983 – 3 June 1991 | |

| Prime Minister | Bob Hawke |

| Preceded by | John Howard |

| Succeeded by | Bob Hawke[1] |

| Member of the Australian Parliament for Blaxland | |

| In office 25 October 1969 – 15 June 1996 | |

| Preceded by | James Harrison |

| Succeeded by | Michael Hatton |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 January 1944 Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Political party | Australian Labor Party |

| Spouse | Annita Keating |

| Children | 4 |

| Occupation | Trade union staffer |

Paul John Keating (born 18 January 1944), Australian politician, served as the 24th Prime Minister of Australia from 1991 to 1996.

Keating was first elected to the House of Representatives at the 1969 election as the Labor member for Blaxland in New South Wales. He came to prominence as the reformist treasurer of the Hawke Labor government that came to power at the 1983 election. He defeated Hawke for the Labor leadeship in a partyroom ballot and became prime minister in 1991, and led Labor to its fifth consecutive victory at the 1993 election against the Liberal-National coalition led by John Hewson. Many had considered this election unwinnable for Labor due to poor polls for the 10-year-incumbent federal Labor government, and the effects of the early 1990s recession on Australia. Keating Labor lost the subsequent 1996 election to the Liberal/National Coalition led by John Howard.

Early life

Keating grew up in Bankstown, a working-class suburb of Sydney. He was one of four children of Matthew Keating, a boilermaker and trade-union representative of Irish Catholic descent, and his wife, Minnie. Keating was educated at Catholic schools; he was the first practising Catholic Labor prime minister since James Scullin left office in 1932. Leaving De La Salle College Bankstown (now LaSalle Catholic College) at 15, Keating decided not to pursue higher education, and worked as a clerk at the Electricity Commission of New South Wales and then as a trade union research assistant. He joined the Labor Party as soon as he was eligible. In 1966, he became president of the ALP’s Youth Council.[2] In the 1960s Keating managed ‘The Ramrods’ rock band.[3]

Entry into politics

Through the unions and the NSW Young Labor Council, Keating met other Labor figures such as Laurie Brereton, Graham Richardson and Bob Carr. He also developed a friendship and discussed politics with former New South Wales Labor premier Jack Lang, then in his 90s. In 1971, he succeeded in having Lang re-admitted to the Labor Party.[4] Using his extensive contacts Keating gained Labor endorsement for the federal seat of Blaxland in the western suburbs of Sydney and was elected to the House of Representatives at the 1969 election when he was 25 years of age.[2]

Keating was a backbencher for most of the period of the Whitlam Government (December 1972 – November 1975). He briefly became Minister for the Northern Territory in late October 1975, but lost that post when the Whitlam Government was dismissed by Sir John Kerr on 11 November 1975. After Labor's defeat in 1975, Keating became an opposition frontbencher and, in 1981, he became president of the New South Wales branch of the party and thus leader of the dominant right-wing faction. As opposition spokesperson on energy, his parliamentary style was that of an aggressive debater. He initially supported Bill Hayden against Bob Hawke's leadership challenges, partly because he hoped to succeed Hayden himself.[5] However, by July 1982, as the leader of the New South Wales right-wing faction, he had to accept, at least nominally, his own faction's endorsement of Hawke's challenge. The formal announcement by Keating, as the faction leader, was actually penned by Gareth Evans.[6]

Treasurer: 1983–1991

Following the Labor Party's victory in the March 1983 election, Keating was appointed treasurer, a post he held until 1991. Keating succeeded John Howard as treasurer and was able to use the size of the budget deficit to attack the former treasurer, and question the economic credibility of the Liberal-National coalition. That the deficit had significantly blown out in the lead up to the election was not disclosed by the Liberal-National coalition government.[7] The incoming Hawke Labor government only learned about the extent of the deficit when briefed by Treasury officials after the election. According to Bob Hawke, the historically large $9.6 billion budget deficit left by the Coalition ‘became a stick with which we were justifiably able to beat the Liberal National Party Opposition for many years’.[7] Although, as the former treasurer, Howard was ‘discredited’[8] by the budget blowout, he had argued unsuccessfully against Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, that the revised figures should be disclosed before the election.[9]

Keating was one of the driving forces behind the various microeconomic reforms of the Hawke government. The Hawke/Keating governments of 1983–1996 pursued economic policies and restructuring such as floating the Australian dollar in 1983, reducing tariffs on imports, taxation reforms, moving from centralised wage-fixing to enterprise bargaining, privatisation of publicly-owned companies such as Qantas and the Commonwealth Bank, and deregulation of the banking system. Keating was instrumental in the introduction of the Prices and Incomes Accord, an agreement between the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) and the government to negotiate wages. His management of the Accord, and close working relationship with ACTU leader Bill Kelty, was a source of tremendous political power for Keating. Keating was able to bypass cabinet in many instances, notably in the exercise of monetary policy.[10]

In 1985, Keating championed introduction of a broad-based consumption tax, similar to the goods and services tax (GST) of the Howard government.[11][12] During the 1984 election campaign, Hawke had promised a policy paper on taxation reform to be discussed with all stakeholders at a tax summit. Three options - A, B and C - were presented in the Draft White Paper, with Keating and his Treasury colleagues fiercely advocating for Option C, which included a consumption tax of 15% on goods and services along with reductions in personal and company income tax, a fringe benefits tax and a capital gains tax. Although Keating was able to win the support of a reluctant cabinet, in the face of opposition from the public, the welfare lobby, the ACTU, and the business community, Hawke intervened to drop the consumption tax. Many of the remainder of the reforms were adopted in the September 1985 tax reform package, but the loss of the consumption tax was a bitter defeat for Keating. However, he joked about it at the press conference saying, "It's a bit like Ben Hur. We've crossed the line with one wheel off, but we have crossed the line."[13]

Keating's tenure as treasurer and prime minister is often criticised for high interest rates and the 1990s recession - the so-called "recession we had to have". Through the 1980s both the global and Australian economy grew quickly and by the late 1980s was overheating, with inflation around 8 to 10 percent. By 1988 the Reserve Bank of Australia began tightening monetary policy, and household interest rates peaked at 18 percent. It is often said that the Bank was too slow in easing monetary policy, and that this ultimately led to a recession. In private, Keating had argued for rates to rise earlier than they did, and fall sooner, although his view was at odds with the Reserve Bank and his Treasury colleagues.[10][14] Publicly, Hawke and Keating had said there would be no recession - or there would be a "soft landing" - but this changed when Keating announced the country was indeed in recession - "this was the recession we had to have" he famously added. According to Paul Kelly, "It was perhaps the most stupid remark of his career and it nearly cost him the prime ministership. However — it is largely true — the boom begat the recession."[15] During the subsequent Howard Government (1996–2007), Keating often criticised Howard for taking credit for the relatively good economic conditions Australia experienced over the latter half of Howard's time as prime minister, without acknowledging that the 1990s recession ended the inflation problem.[16]

At a 1988 meeting at Kirribilli House, Hawke and Keating discussed the handover of the leadership to Keating. Hawke agreed in front of two witnesses that he would resign in Keating's favour after the 1990 election.[10] The Deputy Prime Minister, Lionel Bowen, retired at the 1990 election, and Keating was appointed Deputy to Hawke. In June 1991, after Hawke had intimated to Keating that he planned to renege on the deal on the basis that Keating had been publicly disloyal and moreover was less popular than Hawke, Keating challenged him for the leadership. He lost (Hawke won 66–44 in the party room ballot),[17] resigned as Treasurer and Deputy Prime Minister, and declared in a press conference that he had fired his 'one shot'.[18] Publicly, at least, this made his leadership ambitions unclear. Having lost the first challenge to Hawke, Keating realised that events would have to move very much in his favour for a second challenge to be even possible.[19]

Several factors contributed to the success of Keating’s second challenge in December 1991. Over the remainder of 1991, the economy showed no signs of recovery from the recession, and unemployment continued to rise.[20][21] Some of Keating’s supporters undermined the government.[20] The Government was polling poorly.[19] Perhaps more significantly, Liberal leader John Hewson introduced Fightback!, an economic policy package, which, according to Keating’s biographer, John Edwards, ‘appeared to astonish and stun Hawke’s cabinet’.[22] According to Edwards, ‘Hawke was unprepared to attack it and responded with windy rhetoric’.[22] After Fightback!, Keating ‘did practically nothing’ as Hawke’s support dwindled and the numbers moved in Keating’s favour.[23] On 20 December 1991, Keating defeated Hawke in a party-room ballot for the leadership by 56 votes to 51.

Prime Minister: 1991–1996

Keating's agenda included making Australia a republic, reconciliation with Australia's indigenous population, and furthering economic and cultural ties with Asia. The addressing of these issues came to be known as Keating's "big picture."[24] Keating's legislative program included establishing the Australian National Training Authority (ANTA), a review of the Sex Discrimination Act,[clarification needed] and native title rights of Australia's indigenous peoples following the Mabo High Court decision. He developed bilateral links with Australia's neighbours – he frequently said there was no other country in the world more important to Australia than Indonesia[25] – and took an active role in the establishment of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Forum (APEC), initiating the annual leaders' meeting. One of Keating's far-reaching legislative achievements was the introduction of a national superannuation scheme, implemented to address low national savings. Keating introduced mandatory detention for asylum seekers in 1992.[26] On 10 December 1992, Keating delivered a speech on Aboriginal reconciliation.[27][28][29]

Most commentators believed the 1993 election was "unwinnable" for Labor; the government had been in power for 10 years and the pace of economic recovery from the early 1990s recession was 'weak and slow'.[30] However, Keating succeeded in winning back the electorate with a strong campaign opposing Fightback and a focus on creating jobs to reduce unemployment. Keating led Labor to an unexpected election victory, made memorable by his "true believers" victory speech.[31][32] After Keating, some of the reforms of Fightback were implemented under the centre-right coalition government of John Howard, such as the GST.

In December 1993, Keating was involved in a diplomatic incident with Malaysia, over Keating's description of Dr. Mahathir bin Mohamad as "recalcitrant". The incident occurred after Dr. Mahathir refused to attend the 1993 APEC summit. Keating said, "APEC is bigger than all of us – Australia, the U.S. and Malaysia and Dr. Mahathir and any other recalcitrants." Dr. Mahathir demanded an apology from Keating, and threatened to reduce diplomatic and trade ties with Australia, which became an enormous concern to Australian exporters. Some Malaysian officials talked of launching a "Buy Australian Last" campaign.[33] Keating eventually apologised to Mahathir over the remark.

Keating's friendship with Indonesian President Suharto was criticised by human rights activists supportive of East Timorese independence and by Nobel Peace Prize winner, José Ramos-Horta (later to be East Timor's prime minister and president). The Keating government's cooperation with the Indonesian military and the signing of the Timor Gap Treaty were also criticised.[34]

Defeat

John Hewson was replaced as Liberal party leader by Alexander Downer in 1994. But Downer's leadership was marred by gaffes, and he resigned in 1995. He was succeeded by John Howard, who had previously led the party from 1986 to 1989. Under Howard, the Coalition moved ahead of Labor in opinion polls and Keating was unable to wrest back the lead. The first warning sign of a swing away from Labor came in March 1995, when Labor lost Canberra in a by-election. Later in 1995, Queensland Labor barely held onto its majority at the 1995 state election before losing it altogether in a 1996 by-election held a week after Keating called the a federal election for March. Later, defeated Queensland Premier Wayne Goss said that the people of his state had turned so violently on Keating that they were "sitting on their verandas with baseball bats" waiting for the writs to drop.

Howard, determined to avoid a repetition of the 1993 election, adopted a "small target" strategy – committing to keep Labor reforms such as Medicare, and defusing the republic issue by promising to hold a constitutional convention. This allowed Howard to focus the election on the economy and memory of the early 1990s recession, and on the longevity of the Labor government, which in 1996 had been in power for 13 years.

At the 1996 election, the Keating Government was swept from power in a landslide, losing 29 seats and suffering a five percent two party preferred swing--in terms of seats lost, the second-worst defeat of a sitting government at the federal level in Australia. Keating immediately resigned as Labor Party leader, and resigned from Parliament a little over a month later, on 23 April 1996.[35]

After politics

Since leaving parliament, Keating has been a director of various companies,[36] including the chairman for the Corporate Advisory International section of Lazard, an investment banking firm.[37]

In 1997 Keating declined to accept appointment as a Companion of the Order of Australia. Other than Kevin Rudd, he is the only former post-1975 prime minister not to hold the award since the institution of the Australian Honours System in 1975.[38]

In 2000, he published a book, Engagement: Australia Faces the Asia-Pacific, which focused on foreign policy during his term as prime minister.[39] In March 2002, a Don Watson-authored biography of Keating, Recollections of a Bleeding Heart, was released.

During Howard's prime ministership, Keating made occasional speeches strongly criticising his successor's social policies, and defending his own policies, such as those on East Timor. Keating described Howard as a "desiccated coconut" who was "Araldited to the seat" and that "Howard ... is an old antediluvian 19th century person who wanted to stomp forever ... on ordinary people's rights to organise themselves at work ... he's a pre-Copernican obscurantist", when criticising the Howard government's WorkChoices policy.[40] He described Howard's deputy, Peter Costello, as being "all tip and no iceberg" when referring to a pact made by Howard to hand the prime ministership over to Costello after two terms.[41] On Labor's victory at the 2007 election, Keating said that he was relieved, rather than happy, that the Howard government had been removed. He claimed that there was "Relief that the nation had put itself back on course. Relief that the toxicity of the Liberal social agenda – the active disparagement of particular classes and groups, that feeling of alienation in your own country – was over."[42]

In May 2007, Keating suggested that Sydney, rather than Canberra, should be the capital of Australia, saying that:

John Howard has already effectively moved the Parliament here. Cabinet meets in Philip Street in Sydney, and when they do go to Canberra, they fly down to the bush capital, and everybody flies out on Friday. There is an air of unreality about Canberra. If Parliament sat in Sydney, they would have a better understanding of the problems being faced by their constituents. These real things are camouflaged from Canberra.[43]

Keating was critical of the then opposition leader (and later prime minister) Kevin Rudd's leadership team. For example, before the 2007 federal election, which Labor won, he criticised the then opposition industrial relations spokesperson Julia Gillard, saying she lacked an understanding of principles such as enterprise-bargaining set under his government in the late 1980s and early 1990s. He also attacked Rudd's chief of staff David Epstein and Gary Gray, who was at that time a candidate for Kim Beazley's seat of Brand, to which he was elected in 2007.[44]

In February 2008, Keating joined former prime ministers Whitlam, Fraser and Hawke in Parliament House, Canberra, to witness the parliamentary apology to the Stolen Generations.[45]

In August 2008, he spoke at the book launch of "Unfinished Business: Paul Keating's Interrupted Revolution", authored by economist David Love. Among the topics discussed during the launch were the need to increase compulsory superannuation contributions, as well as to restore incentives (removed under Howard/Costello) for people to receive their superannuation payments in annuities.[46]

Keating is currently a Visiting Professor of Public Policy at the University of New South Wales. He has been awarded honorary Doctorates in Laws from Keio University in Tokyo, the National University of Singapore, and the University of New South Wales[38]

Personal life

In 1975, Keating married Annita van Iersel, a Dutch flight attendant for Alitalia. The Keatings had four children, who spent some of their teenage years in The Lodge, the Prime Minister's official residence in Canberra. They separated in late November 1998.

Keating's daughter, Katherine, is a former adviser to former New South Wales minister Craig Knowles.[47]

Keating's interests include the music of Gustav Mahler[48] and collecting French antique clocks.[2] He now resides in Potts Point, in the Eastern Suburbs of Sydney.

See also

Further reading

- Carew, Edna (1991), Paul Keating Prime Minister, Allen and Unwin.

- Edwards, John (1996), Keating: The Inside Story, Viking.

- Gordon, Michael (1993), A Question of Leadership. Paul Keating. Political Fighter, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, Queensland. ISBN 0 7022 2494 4

- Gordon, Michael (1996), A True Believer: Paul Keating, UQP.

- Keating, Paul (1995), Advancing Australia, Big Picture.

- Keating, Paul (2011), "After Words", Allen & Unwin, ISBN 9781742377599

- Lowe, David (2008), Unfinished Business: Paul Keating's interrupted revolution, Scribe.

- Watson, Don (2002), Recollections of a Bleeding Heart: A Portrait of Paul Keating PM, Knopf.

References

- ^ Hawke held the portfolio for only one day, 3–4 June 1991 with John Kerin taking on the role from 4 June.

- ^ a b c "Civics | Paul Keating (1944–)". Civicsandcitizenship.edu.au. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ "Civicsandcitizenship.edu.au". Civicsandcitizenship.edu.au. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ "Former PM Paul Keating and historian Frank Cain discuss Jack Lang's life, legacy and the Depression". Abc.net.au. 17 November 2005. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ Edwards, John, Keating: The Inside Story, Viking, 1996, p.153

- ^ Edwards, John, Keating: The Inside Story, Viking, 1996, p.159

- ^ a b Hawke, Bob, The Hawke Memoirs, William Heinemann Australia, 1994, p.148

- ^ Errington, W., & Van Onselen, Peter, John Winston Howard: The Biography, Melbourne University Press, 2007, p.102

- ^ Errington, W.,& Van Onselen, Peter, John Winston Howard: The Biography, Melbourne University Press, 2007, p.102

- ^ a b c Kelly, Paul (1994). The End of Certainty: Power, Politics, and Business in Australia. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 186373757X. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- ^ Eccleston, Richard (2007). Taxing reforms: the politics of the consumption tax in Japan, the United States, Canada and Australia. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 202.

- ^ Malone, Paul (2006). Australian Department Heads Under Howard - Career Paths and Practice. ANU Press. p. 136.

- ^ D'Alpuget, Blanch (2011). Hawke: The Prime Minister. Melbourne University Publishing.

- ^ "Keating still casts a shadow". Smh.com.au. 31 August 2004. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ Ian McFarlane (2 December 2006). "The real reasons why it was the 1990s recession we had to have". theage.com.au. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ^ "Paul Keating on the lead-up to the federal election". Lateline – ABC. 07/06/2007. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Edwards, John, Keating: The Inside Story, Viking, 1996, p.435

- ^ Edwards, John, Keating: The Inside Story, Viking, 1996, p.438

- ^ a b Edwards, John, Keating: The Inside Story, Viking, 1996, p.439

- ^ a b Hawke, Bob, The Hawke Memoirs, William Heinemann Australia, 1994, p.544

- ^ Edwards, John, Keating: The Inside Story, Viking, 1996, p.440

- ^ a b Edwards, John, Keating: The Inside Story, Viking, 1996, p.441

- ^ Edwards, John, Keating: The Inside Story, Viking, 1996, p.442

- ^ Fast Forward, Shaun Carney, The Age, 20-Nov-2007

- ^ Sheriden, Greg (28 January 2008). "Farewell to Jakarta's Man of Steel". The Australian. Retrieved 30 December 2008.

- ^ Timeline: Mandatory detention in Australia, Special Broadcasting Service, 17 June 2008

- ^ OPINION Phillip Adams (5 May 2007). "The greatest speech". Theaustralian.news.com.au. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ "Keating's Redfern Address voted an unforgettable speech". Cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ Text of Paul Keating's Redfern Speech[dead link]

- ^ Dyster, B., & Meredith, D., Australia in the Global Economy, Cambridge University Press, 1999, p.309

- ^ Text of the "true believers" victory speech at Wikisource

- ^ "audio of the "true believers" victory speech". Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ Shenon, Philip (9 December 1993). "Malaysia Premier Demands Apology". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- ^ The World Today – 5/10/99: Howard hits back at Keating over criticism; Australian Jewish Democratic Society – Rabin and East Timor; Microsoft Word – Alpheus Article September#35.doc; ITV – John Pilger – A voice that shames those who are silent on Timor

- ^ National Archives of Australia, NAA.gov.au Retrieved on 9 June 2009

- ^ For example "ASX listing for Brain Resource Company Ltd". Company Information. Australian Stock Exchange. Archived from the original on 7 June 2007. Retrieved 21 August 2007.

- ^ Lazard (2010). Advisory Team. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ^ a b "After office". Australia's PMs – Paul Keating. National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Books in Print". Booksinprint.seekbooks.com.au. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ "Middle-of-the-road fascists can't compose IR policy". The Australian. 2 May 2007.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "The World Today – Keating criticises ALP over compulsory super plan". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2007. Retrieved 14 March 2007.

- ^ "Paul Keating relieved John Howard era is over". Herald Sun. 26 November 2007. Retrieved 12 January 2007.

- ^ "Keating: Sydney should be the capital". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 25 May 2007. Archived from the original on 17 October 2007. Retrieved 12 July 2007.

- ^ Lateline, 7-Jun-2007, Also on YouTube: Youtube.com, YouTube.com, YouTube.com

- ^ Welch, Dylan (13 February 2008). "Kevin Rudd says sorry". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 22 February 2008.

- ^ Video of speech, part 1Video of speech, part 2

- ^ Mitchell A Keating's daughter called to testify The Sun-Herald 17 October 2004

- ^ "Keating promoted culture as something to celebrate". Smh.com.au. 15 September 2009. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

External links

- Paul Keating's official website

- "Paul Keating". Australia's Prime Ministers. National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- "Paul Keating". National Museum of Australia. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- Paul Keating Insults Archive

- Paul Keating at the National Film and Sound Archive

- Video – Paul Keating vs John Hewson

- Video – Re: The Great Motion

- Video – Floating the dollar

- Photo – Delivering the annual John Curtin Prime Ministerial Lecture 2009

- Text – 2009 John Curtin Prime Ministerial Lecture

- Painting – Paul Keating

- Watch a recording of the Redfern Address on australianscreen online

- The Redfern Address was added to the National Film and Sound Archive's Sounds of Australia Registry in 2010