| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 40 to 45 million [1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 28 million (2005)[2][3] | |

| 12.5 million (2006)[4] | |

| 126,000 (2000)[1][5] | |

| 113,000 (1993)[6] | |

| 87,000 (1986)[7] | |

| 17,000 (2001)[8] | |

| 13,000 (2001)[8] | |

| Languages | |

| Pashto (plus second languages from countries of residence) | |

| Religion | |

| Islam (predominantly Sunni) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Neighboring Iranian peoples (Tajiks, Persians, Baloch, Pamiri peoples) · Burusho · Hindkowans · Nuristanis · Pashai | |

Pashtuns[9] (also Pathans[10] or ethnic Afghans[11][12]) are an ethno-linguistic group with populations primarily in eastern and southern Afghanistan and in the North-West Frontier Province, Federally Administered Tribal Areas and Balochistan provinces of Pakistan. The Pashtuns are typically characterized by their Pashto language, adherence to Pashtunwali (a pre-Islamic indigenous religious code of honor and culture)[13] and Islam.

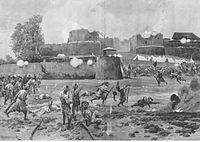

Pashtuns have survived a turbulent history over several centuries, during which they have rarely been politically united. Pashtun martial prowess has been renowned since Alexander the Great's invasion in the third century BCE.[14] Their modern past began with the rise of the Durrani Empire in 1747. The Pashtuns were also one of the few groups that managed to impede British imperialism during the 19th century.[15] Pashtuns played a pivotal role in the Soviet war in Afghanistan (1979–89), as many joined the Mujahideen. The Pashtuns gained world-wide attention with the rise and fall of the Taliban, since they were the main ethnic contingent in the movement. Modern Pashtuns have been prominent in the rebuilding of Afghanistan where they are the largest ethnic group and are an important community in Pakistan, where they are the second-largest ethnic group.

The Pashtuns are the world's largest (patriarchal) segmentary lineage tribal group.[16] The total population of the group is estimated to be at least 40 million, but an accurate count remains elusive due to the nomadic nature of many tribes, the practice of secluding women and the lack of an official census in Afghanistan since 1979.[17]

Demographics

The vast majority of Pashtuns can be found in an area stretching from western Pakistan to southwestern Afghanistan. Additional Pashtun communities live in the Northern Areas, Azad Kashmir and Karachi in Pakistan as well as throughout Afghanistan. There are smaller communities in Iran and India, and a large migrant worker community in the countries of the Arabian Peninsula. Important metropolitan centers of Pashtun culture include Peshawar and Kandahar. In addition, Quetta and Kabul are ethnically mixed cities with large Pashtun populations.

Pashtuns comprise over 15.42% of Pakistan's population or 25.6 million[2] and in Afghanistan are 42% of the population or 12.5 million. Though no official census has been conduted in Afghanistan for decades, some higher estimates place speakers of Pashto at 60% to 65% of the population.[18] The exact measure of all of these figures remains uncertain, particularly those for Afghanistan, and are affected by approximately three million Afghan refugees (of which 81.5% or 2.49 million are ethnic Pashtuns) that remain in Pakistan.[3] An unknown number of refugees continue to reside in Iran.[19] A cumulative population assessment suggests a total of over 40 million.[2][4][3]

History and origins

The history of the Pashtuns is ancient and much of it has yet to be fully researched. From the second millennium BCE to the present, Pashtun regions have seen invasions and migrations including Aryan tribes (Iranian peoples, Indo-Aryans, Medes, and Persians), Scythians, Kushans, Hephthalites, Greeks, Arabs, Turks, and Mongols. There are many conflicting theories about the origins of the Pashtun people, some modern and others archaic, both among historians and the Pashtuns themselves.

Ancient references

The Greek historian Herodotus first mentioned a people called Pactyan living on the eastern frontier of the Persian Satrapy Arachosia as early as the 1st millennium BCE.[20] In addition, the Rig-Veda mentions a tribe called the Pakthas (in the region of Pakhat) as inhabiting eastern Afghanistan and some have speculated that they may have been early ancestors of the Pashtuns.[21] Other ancient peoples linked to the Pashtuns includes the Bactrians who spoke a related Middle Iranian language.

Pashtuns are also historically referred to as ethnic Afghans as the terms Pashtun and Afghan were synonymous until the advent of modern Afghanistan and the division of the Pashtuns by the Durand Line, a border drawn by the British in the late 19th century. According to V. Minorsky, W.K. Frazier Tyler, M.C. Gillet and several other scholars, "The word Afghan first appears in history in the Hudud-al-Alam in 982 CE."[22] It was used by the Pashtuns and refers to a common legendary ancestor known as Afghana.

It is believed that the Pashtuns emerged from the area around Kandahar and the Suleiman Mountains and began expanding millennia ago.[12] In this geographic location they would have often been in close contact with the Persians, while according to archaeological, morphological and hermeneutic evidence many Pashtuns were most likely Pagan, with sizable minorities of Buddhists, Hindus, Zoroastrians and Jews prior to the arrival of Muslim Arabs in the eighth century CE.[23]

Anthropology and linguistics

The origins of the Pashtuns are mixed, but their language is classified as an Eastern Iranian tongue, itself a sub-branch of the Indo-Iranian branch of the greater Indo-European family of languages, and thus the Pashtuns are classified as an Iranian people,[24][25][26][27] possibly as partial modern-day descendants of the Scythians, an ancient Iranian group.[28] According to academic Yu. V. Gankovsky, the Pashtuns began as a "union of largely East-Iranian tribes which became the initial ethnic stratum of the Pashtun ethnogenesis dates from the middle of the first millennium CE and is connected with the dissolution of the Epthalite (White Huns) confederacy."[29] Early precursors to the Pashtuns were Old Iranian tribes that spread throughout the eastern Iranian plateau.[30][31] The Pashto-speaking Pashtuns refer to themselves as Pashtuns or Pukhtuns depending upon whether they are speakers of the southern dialect or northern dialect respectively. These Pashtuns compose the core of ethnic Pashtuns who are found in western Pakistan and southern-eastern Afghanistan. Many Pashtuns have intermingled with various invaders, neighboring groups, and migrants (as have the other Iranian peoples). In terms of phenotype, the Pashtuns overall are predominantly a Mediterranean Caucasoid people,[32] although light hair and eye colors are not uncommon, especially among remote mountain tribes.

Oral traditions

Some anthropologists lend credence to the mythical oral traditions of the Pashtun tribes themselves. For example, according to the Encyclopaedia of Islam, the Theory of Pashtun descent from Israelites is traced to Maghzan-e-Afghani who compiled a history for Khan-e-Jehan Lodhi in the reign of Mughal Emperor Jehangir in the seventeenth century CE. Another book, that corresponds with Pashtun historical records, Taaqati-Nasiri, states that in the seventh century a people called the Bani Israel settled in Ghor, southeast of Herat, Afghanistan and then migrated south and east. These Bani Israel references are in line with the commonly held view by Pashtuns that when the twelve tribes of Israel were dispersed (see Israel and Judah and Lost Ten Tribes), the tribe of Joseph, among other Hebrew tribes, settled in the region.[33] Hence the tribal name 'Yusef Zai' in Pashto translates to the 'sons of Joseph'. A similar story is told by Iranian historian Ferishta.[34]

Maghzan-e-Afghani's Bani-Israel theory has largely been debunked due to historical and linguistic inconsistencies. The oral tradition is believed to be a myth that grew out of a political and cultural struggle between Pashtuns and the Mughals, which explains the historical backdrop for the creation of the myth, the inconsistencies of the mythology, and the linguistic research that refutes any Semitic origins.[35]

Other Pashtun tribes claim descent from Arabs including some even claiming to be descendants of the Muslim Prophet Muhammad (popularly referred to as sayyids).[14] Some groups from Peshawar and Kandahar (such as the Afridis, Khattaks and Sadozais) also claim to be descended from Alexander the Great's Greeks.[36]

Genetics

Research into human DNA has emerged as a new and innovative tool being used to explore the genetic make-up of various populations in order to ascertain historical population movements. According to some genetic research the Pashto-speaking Pashtuns are mainly related to other Iranian peoples as well as the Burusho of the Northern Areas of Pakistan, who speak a language isolate.[36]

Modern era

The Pashtuns are intimately tied to the history of modern Afghanistan and western Pakistan stretching back to the Hotaki dynasty and later the Durrani Empire.[37] The Hotakis were Ghilzai tribesmen, who defeated the Persian Safavids and seized control over much of Persia from 1722 to 1736. This was followed by the conquests of Ahmad Shah Durrani who was a former high-ranking military commander under the ruler Nadir Shah of Persia. He founded the Durrani Empire that covered most of what is today Afghanistan, Pakistan, Kashmir, Indian Punjab, and Khorasan province of Iran.[38][39] After the fall of the Durrani Empire in 1818, it was the Barakzai clan that took control of Afghanistan. Specifically, the subclan known as the Mohamedzai, ruled Afghanistan between 1826 to the end of Mohammad Zahir Shah reign in 1973. This legacy continues into modern times as Afghanistan is run by President Hamid Karzai.

The Pashtuns in Afghanistan fought the British to a standstill and kept the Russians at bay during the so-called Great Game, during which Afghanistan remained an independent state that played the two large imperialist empires against each other to maintain some semblance of autonomy. Despite this, during the reign of Abdur Rahman Khan (1880-1901), Pashtun regions were divided by the Durand Line and control of what is today western Pakistan was ceded to British India in 1893.[40] In the twentieth century, various Pashtuns living under British Indian rule in the North-West Frontier Province agitated for Indian independence, including Khan Wali Khan and Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (both members of the Khudai Khidmatgar, popularly referred to as the Surkh posh or "the Red shirts"), and were inspired by Mahatma Gandhi's non-violent method of resistance.[41] Later, in the 1970s, Khan Wali Khan pressed for more autonomy for Pashtuns.

Pashtuns in Afghanistan attained complete independence from British intervention during the reign of King Amanullah Khan, following the Third Anglo-Afghan War.[15] The monarchy ended with Sardar Daoud Khan seizing control of Afghanistan in 1973, which opened the door to Soviet intervention and eventually culminated in the Saur Revolution or Communist take-over of Afghanistan in 1978. Starting in the late 1970s, many Pashtuns joined the Mujahideen opposition against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. These Mujahideen fought for control of Afghanistan against the Communist Khalq and the Parcham factions. More recently, the Pashtuns became known for being the primary ethnic group that comprised the Taliban, which was a religious movement that emerged from Kandahar, Afghanistan.[42] As of late 2001, the Taliban government had been removed from power as a result of the US-led invasion of Afghanistan.

Pashtuns have played an important role in the region of South and Central Asia. The current President of Afghanistan, Hamid Karzai from Qandahar. In neighboring Pakistan ethnic Pashtun politicians, notably Ayub Khan and Ghulam Ishaq Khan, have also attained the Presidency in the past. The Afghan royal family now represented by Muhammad Zahir Shah is also of ethnic Pashtun origin. Other prominent Pashtuns include the seventeenth century warrior poet Khushal Khan Khattak, Afghan "Iron" Emir Abdur Rahman Khan and in modern times U.S. Ambassador to Iraq Zalmay Khalilzad and former Cosmonaut Abdul Ahad Mohmand among many others.

Pashtuns defined

Among historians, anthropologists, and the Pashtuns themselves, there is some debate as to who exactly is a Pashtun. The most prominent views are:

- Pashtuns are predominantly an Eastern Iranian people who are speakers of the Pashto language and live in a contiguous geographic location across Pakistan and Afghanistan. This is the generally accepted academic view.[43]

- Pashtuns are Muslim, following Pashtunwali, as well as being Pashto-speakers and meeting other criteria.[44]

- In accordance with the legend of Qais Abdur Rashid, the figure traditionally regarded as progenitor of the Pashtun people, Pashtuns are those whose related patrilineal descent may be traced back to legendary times.

These three definitions may be described as the ethno-linguistic definition, the religious-cultural definition, and the patrilineal definition, respectively.

Ethnic definition

The ethno-linguistic definition is the most prominent and accepted view as to who is and is not a Pashtun.[45] Generally, this most common view holds that Pashtuns are defined within the parameters of having mainly eastern Iranian ethnic origins, sharing a common language, culture and history, living in relatively close geographic proximity to each other, and acknowledging each other as kinsmen. Thus, tribes that speak disparate yet mutually intelligible dialects of Pashto will acknowledge each other as ethnic Pashtuns and even subscribe to certain dialects as "proper", such as the Pukhtu spoken by the Yousafzai and the Pashto spoken by the Durrani in Kandahar.[46] These criteria tend to be used by most Pashtuns in Pakistan and Afghanistan as the basis for who can be counted as a Pashtun.

Cultural definition

The religious and cultural definition is more stringent and requires Pashtuns to be Muslim and adherents of the Pashtunwali code.[47] This is the most prevalent view among the more orthodox and conservative tribesmen who do not view Pashtuns of the Jewish faith as actual Pashtuns even if they themselves might claim to be of Hebrew ancestry depending upon which tribe is in question. The religious definition for Pashtuns is partially based upon the laws of Pashtunwali, and that those who are Pashtun must follow and honor Pashtunwali. However, Pashtun society is not entirely homogenous in the religious sense, as Pashtuns, who are predominantly Sunni Muslims, can also be followers of the Shia sect among others. In addition, the Pakistani Jews and the Afghan Jewish population, once numbering in the thousands, have largely relocated to Israel. Overall, more flexibility can be found among Pashtun intellectuals and academics who sometimes simply define who is and is not a Pashtun based upon other criteria that often excludes religion.

Ancestral definition

The patrilineal definition is based on an important orthodox law of Pashtunwali. Its main requirement is that anyone claiming to be a Pashtun must have a Pashtun father. This law has maintained the tradition of exclusively patriarchal tribal lineage intact. Under this definition, in order to be an ethnic Pashtun, there is less regard as to what language one speaks (Pashto, Persian, Urdu, English, etc.), while more emphasis is placed upon one's father. Thus, the Pathans in India, for example, who have lost both the language and presumably many of the ways of their putative ancestors, can, by being able to trace their fathers' ethnic heritage back to the Pashtun tribes (who some believe are descendants of the four grandsons of Qais Abdur Rashid, a possible legendary progenitor of the Pashtuns), remain "Pashtun".[48] The legend states that Qais, after having heard of the new religion of Islam, traveled to meet the Muslim Prophet Muhammad in Medina and returned to Afghanistan-Pakistan area a Muslim. Qais, in turn, purportedly had many children and one son, Afghana, produced up to four sons who set out towards the east including one son who went towards Swat, another towards Lahore, another to Multan, and finally one to Quetta. This legend is one of many traditional tales among the Pashtuns regarding their disparate origins that remain largely unverifiable.

Putative ancestry

There are various communities which claim Pashtun descent and are largely found amongst other groups in South and Central Asia who generally do not speak Pashto and are often considered either overlapping groups or are simply assigned to the ethno-linguistic group that corresponds to their geographic location and their mother tongue. Some groups who claim Pashtun descent include various non-Pashtun Afghans who are often conversant in Persian rather than Pashto.[4]

Many claimants of Pashtun heritage in South Asia have mixed with local Muslim populations and refer to themselves (and Pashto-speaking Pashtuns and often Afghans in general) in the Hindi-Urdu variant Pathan rather than Pashtun or Pukhtun.[49] These populations are usually only part-Pashtun, to varying degrees, and often trace their Pashtun ancestry putatively through a paternal lineage, and are not universally viewed as ethnic Pashtuns (see section on Pashtuns Defined for further analysis).

Some groups claiming Pashtun descent live in close proximity to Pashtuns such as the Hindkowans who are sometimes referred to as Punjabi Pathans (in publications such as Encyclopædia Britannica). The Hindkowans speak the Hindko language and are regarded as a group of mixed Pashtun and Punjabi origin.[50] Culturally similar to Pashtuns, the Hinkowans often practice Pashtunwali in Pashtun-majority areas. The Hindkowans are a large minority in major cities such as Peshawar, Kohat, Mardan, and Dera Ismail Khan and in mixed districts including Haripur and Abbottabad where they are often bilingual in Hindko and Pashto.

Additionally, upwards of 20% of Urdu-speakers claim partial Pashtun ancestry.[51][52] Indian Pathans claim descent from Pashtun soldiers that settled in northern India and intermarried with local Muslims during the era of the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Empire. The Rohilla Pashtuns, after their defeat by the British, are notable for having intermarried with local Muslims. They are believed to have been bilingual in Pashto and Urdu until the mid-nineteenth century. The repression of Rohilla Pashtuns by the British in the late eighteenth century caused thousands to flee to the Dutch colony of Guyana in South America.[53]

Lastly, small minorities of Sikhs and Hindus, who are often bilingual in Pashto and Punjabi, are estimated to be in the thousands and can be found in parts of Afghanistan.[54]

Culture

Pashtun culture was formed over the course of many centuries. Pagan traditions survived in the form of traditional dances, while literary styles and music largely reflect strong influence from the Persian tradition and regional musical instruments fused with localized variants and interpretation. Pashtun culture is a unique blend of native customs and strong influences from Central, South and West Asia.

Language

The Pashtuns speak Pashto, an Indo-European language. It belongs to the Iranian sub-group of the Indo-Iranian branch.[55] It can be further delineated within Eastern Iranian and Southeastern Iranian. Pashto is written in the Perso-Arabic script and is divided into two main dialects, the northern "Pukhtu" and the southern "Pashto".

Pashto has ancient origins and bears similarities to extinct languages such as Avestan and Bactrian.[56] Its closest modern relatives include Pamir languages, such as Shughni and Wakhi, and more distantly Ossetic and has an ancient legacy of borrowing vocabulary from neighboring languages including Persian and archaic Sanskrit. Invaders have left vestiges as well as Pashto has borrowed words from ancient Greek, Arabic and Turkic, while modern borrowings come primarily from English.[57]

Fluency in Pashto is often the main determinant as to whether there is group acceptance as to who is and is not considered a Pashtun. Pashtun nationalism emerged following the rise of Pashto poetry that linked language and ethnic identity starting with the work of Khushal Khan Khattak and continued with his grandson Afzal Khan (author of Tarikh-e Morassa, a history of the Pashtun people).[57]

Pashto has national status in Afghanistan and regional status in Pakistan. In addition to their mother-tongue, many Pashtuns are fluent in Dari (Afghan Persian) and/or Urdu as well as English.

Religion

Pashtuns are predominantly Sunni Muslims, most of them followers of the Hanafite branch of Sunni Islam. There is a small minority of Ithna Asharia Shia Pashtuns largely concentrated in Afghanistan.[58]

Studies conducted amongst the Ghilzai reveal strong linkages between tribal affiliation and membership in the larger ummah (Islamic community), as most Pashtuns believe that they are descendents of the aforementioned Qais Abdur Rashid who is purported to have been an early convert to Islam and thus bequeathed the faith to the entire Pashtun population.[59] A legacy of sufi activity remains common in Pashtun regions as evident in song and dance. Many Pashtuns are prominent Ulema, or Islamic scholars, such as Dr. Muhammad Muhsin Khan who translated the Noble Quran and Sahih Al-Bukhari and many other books into English.[60]

Non-Muslim Pashtuns are virtually non-existent as there is limited data regarding irreligious groups and minorities. Following the founding of the state of Israel after World War II and ensuing decades, a tiny Pashtun Jewish population (numbering in the hundreds) left Kandahar and Peshawar.[61][62]

Pashto literature

Throughout Pashtun history, poets, prophets, kings and warriors have been amongst the most revered members of society. For much of Pashtun history, literature has not played a major role as Persian was the literary lingua franca used for communication purposes by neighboring peoples and generally relied upon for writing purposes. However, by the sixteenth century early written records of Pashto began to appear, the earliest of which describes Sheikh Mali's conquest of Swat.[63] The advent of Pashto poetry and the revered works of Khushal Khan Khattak and Rahman Baba in the seventeenth century helped transition Pashto towards the modern period.[64] In the twentieth century, Pashto literature gained significant prominence with the poetic works of Ameer Hamza Shinwari who was noted for his development of Pashto Ghazals.[65] In recent times, Pashto literature has received increased patronage, but due to relatively high illiteracy rates, many Pashtuns continue to rely upon the oral tradition. Pashtun males continue to meet at chai khaanas or tea cafes to listen and relate various oral tales of valor and history.

Despite the general male dominance of Pashto oral story-telling, Pashtun society is also marked by some matriarchal tendencies.[66] Folktales involving reverence for Pashtun mothers and matriarchs are common and are passed down from parent to child, as is most Pashtun heritage, through a rich oral tradition that has survived the ravages of time.

Pashtunwali

The term "Pakhto" or "Pashto" from which the Pashtuns derive their name is not merely the name of their language, but is synonymous with a pre-Islamic honor code/religion formally known as Pashtunwali (or Pakhtunwali).[67] Pashtunwali is believed to have originated millennia ago during pagan times and has, in many ways, fused with Islamic tradition.[68] Pashtunwali governs and regulates nearly all aspects of Pashtun life ranging from tribal affairs to individual "honor" (nang) and behavior.

There are numerous intricate tenets of Pashtunwali that influence Pashtun social behavior. One of the better known tenets is Melmastia or the notion of hospitality and asylum to all guests seeking help. Perceived wrongs or injustice call for Badal or swift revenge. A popular Pashtun saying, "Revenge is dish best served cold", was borrowed by the British and popularized in the West.[69] Men are expected to protect Zan, Zar, Zameen which translates to women, treasure, and land. Some aspects promote peaceful co-existence such as Nanawati or the humble admission of guilt for a wrong committed, which should result in automatic forgiveness from the wronged party. These and other basic precepts of Pashtunwali continue to be followed by many Pashtuns, especially in rural areas.

Sports

Native traditional sports include buzkashi, a contest between horsemen (believed to have been brought to the region by the Mongols) that entails dragging a goat carcass and keeping it away from other players. Another Pashtun past-time is naiza bazi, which also involves horsemen who compete in spear throwing.[70]

Polo is also an ancient traditional sport in the region and is a popular amongst many tribesmen such as the Yousafzai. Like other Afghans, many Pashtuns engage in wrestling (Pehlwani), which is often part of larger sporting events.[71] Cricket is largely a legacy of British rule in the North-West Frontier Province and many Pashtuns have become prominent participants (such as Shahid Afridi and Imran Khan).

Football (soccer) is a more recent sport that increasing numbers of Pashtuns have started to play. Children engage in various games including a form of marbles called buzul-bazi which is played with the knuckle bones of sheep. Although traditionally less involved in sports than boys, young Pashtun girls often play volleyball and basketball, especially in urban areas.

Performing arts

Pashtun performers remain avid participants in various physical forms of expression including dance, sword fighting, and other physical feats. Perhaps the most common form of artistic expression can be seen in the various forms of Pashtun dances.

One of the most prominent dances is the Attan, a dance with ancient pagan roots, that was later modified by Islamic mysticism in some regions, and has become the national dance of Afghanistan.[72] A rigorous exercise, the Attan is performed as musicians play various native instruments including the dhol (drums), tablas (percussions), rubab (a bowed string instrument), and toola (wooden flute). Involving a rapid circular motion, dancers perform until no one is left dancing in a fashion similar to sufi whirling dervishes. Numerous other dances are affiliated with various tribes including the Khattak Wal Atanrh (eponymously named after the Khattak tribe), Mahsood Wal Atanrh (which, in modern times, involves the juggling of loaded rifles), and Waziro Atanrh among others. A sub-type of the Khattak Wal Atanrh known as the Braghoni involves the use of up to three swords and requires great skill to successfully execute. Though most dances are dominated by males, some dance performances such as the Spin Takray feature female dancers.[73] Additionally, young women and girls often entertain at weddings with the Tumbal (tambourine).

Traditional Pashtun music has ties to Klasik (traditional Afghan music heavily inspired by Indian classical music), Iranian musical traditions, and other various forms found in South Asia. Popular forms include the ghazal (sung poetry) and Sufi qawwali music.[74] General themes tend to revolve around love and religious introspection. Modern Pashto music is currently centered around the city of Peshawar due to the various wars in Afghanistan and tends to combine indigenous techniques and instruments with Iranian-inspired Persian music and Indian Filmi music prominent in Bollywood.[75]

Other modern Pashtun media include an established Pashto language film and tv industry that is based in Pakistan. Producers based in Lahore have created Pashto language films since the 1970s. Pashto films were once popular, but have declined both commercially and critically in recent years.[76] Past films such as Yusuf Khan Sherbano dealt with serious subject matter, traditional stories, and legends, but the Pashto film industry has, since the 1980s, been accused of churning out increasingly lewd exploitation-style films.[77][78] Pashtun lifestyle and issues have been raised by Western and Pashtun expatriate film-makers in recent years. Notable films about the Pashtun experience include British film-maker Michael Winterbottom's In This World,[79] which chronicles the struggles of two Afghan youths who leave their refugee camps in Pakistan and attempt to move to the United Kingdom in search of a better life, and the British mini-series Traffik (re-made as Traffic for US audiences) which featured a Pashtun man (played by Jamal Shah) struggling to survive in a world with few opportunities outside the drug trade.[80] In addition, numerous actors of Pashtun descent also work in India's Bollywood film industry including Kader Khan and Feroz Khan.

Institutions

A prominent institution of the Pashtun people is the intricate system of tribes. The Pashtuns remain a predominantly tribal people, but the world-wide trend of urbanization has begun to alter Pashtun society as cities such as Peshawar and Quetta have grown rapidly due to the influx of rural Pashtuns and Afghan refugees.[81] Many still identify themselves with various clans despite this trend towards urbanization.

More precisely, there are several levels of organization within the Pashtun tribal system: the Tabar (tribe) is subdivided into kinship groups called Khels. The Khel in turn is divided into smaller groups (Pllarina or Plarganey), each of which consists of several extended families or Kahols.[82] "A large tribe often has dozens of sub-tribes whose members may see themselves as belonging to each, some, or all of the sub-tribes in different social situations (co-operative, competitive, confrontational) and identify with each accordingly."[82] Pashtun tribes are divided into four 'greater' tribal groups: Sarbans, Batans, Ghurghusht and Karlans.

In addition to the tribal hierarchy, another prominent Pashtun institution is that of the Jirga or 'Senate' of elected elders and wise men. Most decisions in tribal life are made by members of the Jirga, which is the main institution of authority that the largely egalitarian Pashtuns willingly acknowledge as a viable governing body.[83]

Pashtuns often observe special occasions upon which to celebrate and/or commemorate events, which are also quite often national holidays in Pakistan and Afghanistan. A common Turko-Iranian celebration known as Nouruz (or New Year) is often observed by Pashtuns.[84] Most prominent are Muslim holidays including Ramadan and Eid al-Fitr. Muslim holidays tend to be the most widely observed and commercial activity can come to a halt as large extended families gather together in what is often both a religious duty and a festive celebration.

Women

The lives of Pashtun women vary from those who reside in conservative rural areas, such as the tribal belt, to those found in relatively freer urban centers.[85] Though many Pashtun women remain tribal and illiterate, others have become educated and gainfully employed.[85] The ravages of the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan and the Afghan wars, leading to the rise and fall of the Taliban, caused considerable hardship amongst Pashtun women as many of their rights were curtailed in favor of a rigid interpretation of Islamic law. The difficult lives of Afghan female refugees gained considerable notriety with the iconic image of the so-called "Afghan Girl" (Sharbat Gula) depicted on the June 1985 cover of National Geographic Magazine.[86] In addition, the male-dominated code of Pashtunwali often constrains women and forces them into designated traditional roles that separate the genders.[13][87] The pace of change and reform for women has been slow as a result of the wars in Afghanistan and the isolation and instability of tribal life in Pakistan.

Modern social reform for Pashtun women began in the 20th century. During the early 20th century, Queen Soraya Tarzi of Afghanistan was an early feminist leader whose advocacy of social reforms for women was so radical that it led to the fall of her and her husband King Amanullah's dynasty.[88] Even during the tumultuous Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, civil rights remained an important issue as feminist leader Meena Keshwar Kamal campaigned for women's rights and founded the Revolutionary Women of Afghanistan (RAWA) in the 1980s.[89]

Today, Pashtun women vary from the traditional housewives who live in seclusion to urban workers, some of whom seek or have attained parity with men.[85] However, due to numerous social hurdles, the literacy rate for Pashtun women remains considerably lower than that of males.[90][91] Abuse against women is also widespread and yet is increasingly being challenged by women's rights organizations which find themselves struggling with conservative religious groups as well as government officials in both Pakistan and Afghanistan. According to researcher Benedicte Grima's book Performance of Emotion Among Paxtun Women, "a powerful ethic of forbearance severely limits traditional Pashtun women's ability to mitigate the suffering they acknowledge in their lives."[92]

Pashtun women often have their legal rights curtailed in favor of their husbands or male relatives as well. For example, though women are technically allowed to vote in Afghanistan and Pakistan, many have been kept away from ballot boxes by males.[93] Traditionally, Pashtun women have few inheritance rights and are often charged with taking care of large extended families of their spouses.[94] Another tradition that persists is swara, a practice that involves giving a female relative to someone in order to rectify a dispute. The practice was declared illegal in 2000, but continues in tribal regions.[95]

Despite obstacles, many Pashtun women have begun a process of slow change. While most Pashtun women are illiterate, a rich oral tradition and resurgence of poetry has been inspirational to many Pashtun women seeking to learn to read and write.[66] As a sign of further female emancipation, a Pashtun woman recently became one of the first female fighter pilots in Pakistan's Air force.[96] In addition, numerous Pashtun women have attained high political office both in Pakistan and, following recent elections, in Afghanistan, where the percentage of female representatives is one of the highest in the world.[97] Substantial work remains though for Pashtun women who hope to gain equal rights with men who remain disproportionately dominant in most aspects of Pashtun society. Human rights organizations, including the Afghan Women's Network, continue to struggle for greater women's rights as does the Aurat Foundation in Pakistan, which attempts to safeguard women from domestic abuse.[98][99]

See also

Notes and references

- Note: population statistics for Pashtuns (including those without a notation) in foreign countries were derived from various census counts, the UN, the CIA Factbook, Ethnologue, and the Joshua Project.

- ^ a b Northern Pashto, Ethnologue.com (retrieved 7 June 2006)

- ^ a b c Population by Mother Tongue, Population Census Organization, Government of Pakistan (retrieved 7 June 2006)

- ^ a b c Census of Afghans in Pakistan, UNHCR Statistical Summary Report (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ a b c Afghanistan, CIA World Factbook (retrieved 7 June 2006)

- ^ Southern Pashto, Ethnologue.com (retrieved 7 June 2006)

- ^ Languages of Iran, Ethnologue.com (retrieved 7 June 2006)

- ^ Languages of the United Kingdom, Ethnologue.com (retrieved 7 June 2006)

- ^ a b Descent into Disaster?: Afghan Refugees Middle East Report (retrieved 7 June 2006)

- ^ Pashto/Urdu/Template:PerB Paštūn or Template:Rtl-lang Paxtūn. Also Pushtuns, Pakhtuns, Pukhtuns

- ^ Urdu: Template:Rtl-lang, Hindi: पठान Paṭhān

- ^ Template:PerB Afğān

- ^ a b Banuazizi, Ali and Myron Weiner (eds.). 1994. The Politics of Social Transformation in Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan (Contemporary Issues in the Middle East), Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-2608-8 (retrieved 7 June 2006).

- ^ a b Kakar, Palwasha. Harvard University - School of Law - Tribal Law of Pashtunwali and Women’s Legislative Authority (retrieved 7 June 2006)

- ^ a b Caroe, Olaf. 1984. The Pathans: 500 B.C.-A.D. 1957, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195772210 (retrieved 7 June 2006)

- ^ a b Anglo-Afghan Wars, Iranica.com (retrieved 16 January 2006)

- ^ Ethnic, Cultural and Linguistic Denominations in Pakhtunkhwa, Khyberwatch.com (retrieved 7 June 2006)

- ^ Afghanistan Census of Population and Housing: Phase one Household Listing, UNFPA Projects in Afghanistan (retrieved 18 February 2007)

- ^ The ethnic composition of Afghanistan WAK Foundation 1999 Norway (retrieved 10 January 2007)

- ^ Iran-Pakistan: Refugees, IRIN Asia, UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (retrieved 7 June 2006)

- ^ Chapter 7 of The History of Herodotus (trans. George Rawlinson; originally written 440 BCE)(retrieved 10 January 2007)

- ^ Rig Veda Book Seven, Political Gateway (retrieved 7 June 2006)

- ^ The Khalaj West of the Oxus; excerpts from "The Turkish Dialect of the Khalaj", Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, Vol 10, No 2, pp 417-437 (retrieved 10 January 2007)

- ^ Background Information on Afghanistan-Pre 20th Century History, Lonely Planet (retrieved 10 January 2007)

- ^ Pashtun, Encyclopædia Britannica(retrieved 10 January 2007)

- ^ Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies cais-soas.com (retrieved 10 January 2007)

- ^ Awde, Nicholas and Sarwan, Asmatullah: Pashto Dictionary & Phrasebook: Pashto-English, English-Pashto. Hippocrene Books, January 2003, ISBN 0-7818-0972-X (retrieved 10 January 2007)

- ^ Pashto report, Ethnologue.com

- ^ Iranian-speaking peoples(retrieved 10 January 2007)

- ^ Gankovsky, Yu. V., et al. A History of Afghanistan, Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1982, p. 382 (retrieved 10 January 2007)

- ^ Iranian plateau, Encyclopaedia Britannica (retrieved 10 February 2007)

- ^ Old Iranian Online, University of Texas College of Liberal Arts (retrieved 10 February 2007)

- ^ Afghanistan Ethnic Groups: Pashtun, US Library of Congress (retrieved 10 January 2007)

- ^ Afghanistan, The Virtual Jewish History Tour (retrieved 10 January 2007)

- ^ Introduction: Muhammad Qāsim Hindū Šāh Astarābādī Firištah, History Of The Mohamedan Power In India, The Packard Humanities Institute Persian Texts in Translation (retrieved 10 January 2007)

- ^ Bani-Israelite Theory of Paktoons Ethnic Origin Afghanology.com (retrieved 10 January 2007)

- ^ a b Investigation of the Greek ancestry of populations from northern Pakistan, Human Genetics, 2004 Apr;114(5):484-90. Epub 2004 Feb 25 (retrieved 10 January 2007)

- ^ Afghanistan: History, U.S. Department of State (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ Map of Durrani Empire, pbs.org (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ Map of the Durrani Empire, Afghanland (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ Durand Line, Encyclopaedia Britannica (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ Khan Abdul-Ghaffar Khan, Bachakhan.com (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ Afghanistan: At the Crossroads of Ancient Civilisations, BBC (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ Pashtun Britannica On-Line (retrieved 18 January 2007).

- ^ Understanding Pashto University of Pennsylvania Gazette (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Pakistan: Pakhtuns US Library of Congress (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Pashto National Virtual Translation Center (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ The Pashtun Code, The New Yorker (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Pathans in retrospect, Afghanan dot Net (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Memons, Khojas, Cheliyas, Moplahs.... How Well Do You Know Them? Islamic Voice (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Hindko in Kohat and Peshawar Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 43, No. 3 (1980), pp. 482-510 (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Study of the Pathan Communities in four States of India, Dawat Magazine (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Urdu speaking Pathans in India, Joshua Project (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Afghans of Guyana, Afghanland.com (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Sikhs struggle in Afghanistan, BBC News (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Pashto language, alphabet and pronounciation, Omniglot (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Avestan language, Encyclopaedia Britannica (retrieved 18 February 2007)

- ^ a b Awde, Nicholas and Asmatullah Sarwan. 2002. Pashto: Dictionary & Phrasebook, New York: Hippocrene Books Inc. ISBN 0-7818-0972-X (retrieved 18 February 2007).

- ^ Pashtun US Library of Congress (retrieved 18 January 2007).

- ^ Meaning and Practice, Afghanistan Country Study: Religion, Illinois Institute of Technology (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ The Noble Quran (in 9 VOLUMES), Arabic-English, (ed. Dr. Muhammad Muhsin Khan) (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Where have Pakistan’s Jews gone? Tufts University: Fletcher School (retrieved 19 February 2007).

- ^ The Jews of Afghanistan Museum of the Jewish People (retrieved 19 February 2007).

- ^ History of Pushto language, UCLA Language Materials Project (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Rahman Baba: Poet of the Pashtuns Pashto.org (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Amir Hamza Shinwari Baba, Khyber.org (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ a b The tale of the Pashtun poetess, Leela Jacinto, The Boston Globe, May 22, 2005 (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Pakhtunwali, Afghanan dot net (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Pashtunwali: The Way of the Pashtuns, Afghanland.com (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Halliday, Tony (ed.). 1998. Insight Guide Pakistan, Duncan, South Carolina: Langenscheidt Publishing Group. ISBN 0887297366 (retrieved 19 February 2007).

- ^ Pashtun Sports, World Cultures (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Afghanistan: Sports and Recreation, Afghanistan (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Attan: Afghanistan's National Dance, Virtual Afghans.com (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Khyber.org: Traditional Dances of Pashtoons, Khyber.org (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Traditional Pashto Music, Afghanistan Online (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ PashtoMusic.net (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Pashto Movies & Video Clips, Khyber.org (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Pashto Cinema-Craziness, Khyber.org (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ The Sublime and Surreal World of Pushto Movies, The Hot Spot Online (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Michael Winterbottom Talks About His Tragic Road Movie, "In This World", Indiewire.com (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ Traffik, IMDB (retrieved 18 January 2007)

- ^ How Ethno-Religious Identity Influences the Living Conditions of Hazara and Pashtun Refugees in Peshawar, Pakistan, Department of Urban Studies and Planning, MIT (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ a b Jirga - A Traditional Mechanism of Conflict Resolution in Afghanistan by Ali Wardak, un.org (2003), p.7 (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ Q & A on Afghanistan's Loya Jirga Process, Human Rights Watch (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ Noruz, Encyclopaedia Britannica (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ a b c I have a right to, BBC World Service, Fri January 16, 2006 (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ Along Afghanistan's War-torn Frontier, National Geographic, June 1985 (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ Afghan teacher and public servant gunned down by the Taliban outside her home, The Guardian, Fri January 16, 2006 (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ Abandoning the Wardrobe and Reclaiming Religion in the Discourse on Afghan Women's Islamic Rights, Leela Jacinto, University of Chicago, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 2006, vol. 32, no. 1 (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ Making Waves: Interview with RAWA, RAWA.org, Fri January 16, 2006 (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ Population by Level of Education and Gender, Pakistan Census, Fri January 16, 2006 (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ Laura Bush Meets Afghan Women, CBS News, Fri January 16, 2006 (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ Grima, Benedicte. 1992.Performance of Emotion Among Paxtun Women, University of Texas Press. ISBN 0292727569 (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ I have a right to - Muhammad Dawood Azami: Pashto, BBC World Service (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ Afghanistan Country Study: Family, Government Documents Depository Website, Paul V. Galvin Library, Illinois Institute of Technology (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ Pakistani Girls Forced to Settle Men’s Disputes, Khaleej Times, Fri April 16, 2004 (Alternatives.ca) (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ Pakistan's first women fighter pilots, Zaffar Abbas, BBC News, 11 May 2005 (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ Warlords and women in uneasy mix, Andrew North, BBC News, 14 November 2005 (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ About AWN, Afghan Women's Network (retrieved 10 October 2006)

- ^ Aurat Publication and Information Service Foundation, Aurat Foundation, Fri January 16, 2006 (retrieved 10 October 2006)

Further reading

- Ahmad, Aisha and Boase, Roger. 2003. "Pashtun Tales from the Pakistan-Afghan Frontier: From the Pakistan-Afghan Frontier." Saqi Books (March 1, 2003). ISBN 0-86356-438-0.

- Ahmed, Akbar S. 1976. "Millennium and Charisma among Pathans: A Critical Essay in Social Anthropology." London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Ahmed, Akbar S. 1980. "Pukhtun economy and society." London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Banuazizi, Ali and Myron Weiner (eds.). 1994. "The Politics of Social Transformation in Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan (Contemporary Issues in the Middle East)." Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-2608-8.

- Banuazizi, Ali and Myron Weiner (eds.). 1988. "The State, Religion, and Ethnic Politics: Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan (Contemporary Issues in the Middle East)." Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-2448-4.

- Caroe, Olaf. 1984. "The Pathans: 500 B.C.-A.D. 1957 (Oxford in Asia Historical Reprints)." Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-577221-0

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan. 1985. "Peshawar: Historic city of the Frontier." Sang-e-Meel Publications (1995). ISBN 969-35-0554-9.

- Dupree, Louis. 1997. "Afghanistan." Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-577634-8.

- Elphinstone, Mountstuart. 1815. "An account of the Kingdom of Caubul and its dependencies in Persia, Tartary, and India: comprising a view of the Afghaun nation." Akadem. Druck- u. Verlagsanst (1969).

- Habibi, Abdul Hai. 2003. "Afghanistan: An Abridged History." Fenestra Books. ISBN 1-58736-169-8.

- Hopkirk, Peter. 1984. "The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia." Kodansha Globe; Reprint edition. ISBN 1-56836-022-3.

- Wardak, Ali "Jirga - A Traditional Mechanism of Conflict Resolution in Afghanistan", 2003, online at UNPAN (the United Nations Online Network in Public Administration and Finance).

- "A Study of the Greek Ancestry of Northern Pakistani Ethnic Groups Using 115 Microsatellite Markers." A. Mansoor, Q. Ayub, et al.Am. J. Human Genetics, Oct 2001 v69 i4 p399.