Citation bot (talk | contribs) m Alter: url. Add: oclc, isbn. Removed URL that duplicated unique identifier. | You can use this bot yourself. Report bugs here. | Activated by User:AManWithNoPlan | All pages linked from User:AManWithNoPlan/sandbox2. |

WikiCleanerBot (talk | contribs) m v2.05b - Bot T20 CW#61 - Fix errors for CW project (Reference before punctuation) Tag: WPCleaner |

||

| (191 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{merge from|Modern Palestinian Judeo-Arabic|discuss=Talk:Palestinian Arabic#Merge proposal|date=January 2024}} |

|||

{{Short description|Dialect of Arabic spoken in the State of Palestine}} |

|||

{{multiple issues| |

{{multiple issues| |

||

{{more footnotes|date=December 2010}} |

{{more footnotes|date=December 2010}} |

||

| Line 4: | Line 6: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Infobox language |

{{Infobox language |

||

|name=Palestinian Arabic |

| name = Palestinian Arabic |

||

|nativename= اللهجة الفلسطينية |

| nativename = اللهجة الفلسطينية |

||

|states=[[State of Palestine |

| states = [[State of Palestine]], [[Israel]] |

||

| region = [[Palestine (region)|Palestine]] |

|||

|speakers=5.1 million |

|||

| speakers = {{sigfig|7.570000|2}} million |

|||

|date=2014-2016 |

|||

| date = 2024 |

|||

|ref=<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.ethnologue.com/language/ajp|title=Arabic, South Levantine Spoken|work=Ethnologue|access-date=2018-08-08|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

| ref = e26 |

|||

|familycolor=Afroasiatic |

|||

| familycolor = Afroasiatic |

|||

|fam2=[[Semitic languages|Semitic]] |

|||

| |

| fam2 = [[Semitic languages|Semitic]] |

||

| |

| fam3 = [[Central Semitic languages|Central Semitic]] |

||

| |

| fam4 = [[Arabic]] |

||

| |

| fam5 = [[Levantine Arabic]] |

||

| fam6 = [[South Levantine Arabic]] |

|||

|listclass=hlist |

|||

| listclass = hlist |

|||

|dia1=Fellahi |

|||

| dia1 = Fellahi<br>Madani<br>[[Modern Palestinian Judeo-Arabic]] |

|||

|dia2=Madani |

|||

|script= [[Arabic alphabet]] |

| script = [[Arabic alphabet]] |

||

| iso3comment = (covered by [[iso639-3:apc|apc]]) |

|||

|isoexception=dialect |

|||

|iso3= |

| iso3 = none |

||

| isoexception = dialect |

|||

|glotto=sout3123 |

|||

| glotto = sout3123 |

|||

|glottorefname=South Levantine Arabic |

|||

| glottorefname = South Levantine Arabic |

|||

|notice=IPA |

|||

| notice = IPA |

|||

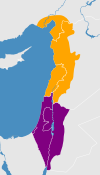

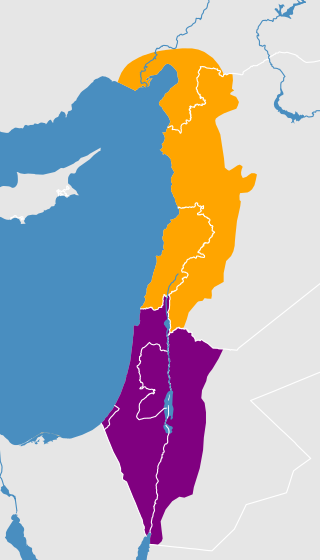

|map=Levantine Arabic Map.jpg |

|||

| map = Levantine Arabic 2022.svg |

|||

|mapcaption= |

|||

{{legend|# |

| mapcaption = {{legend|#800080|[[South Levantine Arabic|South Levantine]]}} |

||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Contains special characters|Levantine}} |

|||

'''Palestinian Arabic''' is a [[dialect continuum]] of mutually intelligible varieties of [[Levantine Arabic]] spoken by most [[Palestinians]] in [[State of Palestine|Palestine]], [[Israel]] and in the [[Palestinian diaspora]].<ref name="asianabsolute">{{cite web|title=How to Reach your Audience with the Right Dialect of Arabic|work=Asian Absolute|url=https://asianabsolute.co.uk/blog/2016/01/19/arabic-language-dialects/|date=2016-01-19|access-date=2020-06-24}}</ref><ref name="daytranslations">{{cite web|title=Arabic Language: Tracing its Roots, Development and Varied Dialects|work=Day Translations|url=https://www.daytranslations.com/blog/arabic-language-dialects/|date=2015-10-16|access-date=2020-06-24}}</ref> |

|||

The Arabic dialects spoken in Palestine and [[Transjordan (region)|Transjordan]] are not one more or less homogeneous linguistic unit, but rather a wide diversity of dialects belonging to various typologically diverse groupings due to geographical, historical, and socioeconomic circumstances.<ref>Palva, H. (1984). A general classification for the Arabic dialects spoken in Palestine and Transjordan. ''Studia Orientalia Electronica'', ''55'', 357-376.</ref> In two dialect comparison studies, Palestinian Arabic was found to be the closest Arabic dialect to [[Modern Standard Arabic]],<ref>{{Cite journal |author=Kwaik, K.; Saad, M.; Chatzikyriakidis, S.; Dobnik, S. |title=A Lexical Distance Study of Arabic Dialects |journal=Procedia Computer Science |year=2018 |issn= 1877-0509 |series=The 4th International Conference on Arabic Computational Linguistics (ACLing) |volume=143 |publication-date=15 November 2018 |pages=1, 3 |language=en |doi= 10.1016/j.procs.2018.10.456|doi-access=free }}</ref> mainly the dialect of the people in [[Gaza Strip]].<ref>{{Cite book |author=Harrat, S.; Meftouh, K.; Abbas, M.; Jamoussi, S.; Saad, M.; Smaili, K. |title=Computational Linguistics and Intelligent Text Processing. Gelbukh, Alexander (Ed.) |publisher=Springer, Cham. |year=2015 |isbn=978-3-319-18110-3 |series=Lecture Notes in Computer Science |volume=9041 |publication-date=April 14–20, 2015 |pages=3, 6 |language=en |chapter=Cross-Dialectal Arabic Processing |doi=10.1007/978-3-319-18111-0_47 |s2cid=5978068 |access-date=29 November 2022 | url=https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-18111-0_47}}</ref> Further dialects can be distinguished within Palestine, such as spoken in the northern [[West Bank]], that spoken by Palestinians in the [[Hebron]] area, which is similar to Arabic spoken by descendants of [[Palestinian refugees]]. |

|||

'''Palestinian Arabic''' is a [[Southern Levant]]ine [[Arabic language|Arabic]] [[dialect]], spoken by most [[Palestinians]] in [[State of Palestine|Palestine]] and Israel and in the Palestinian diaspora populations. Together with [[Jordanian Arabic]], it has the [[ISO 639-3]] language code "ajp", known as [[South Levantine Arabic]]. Further dialects can be distinguished within Palestine, such as spoken in the northern [[West Bank]], that spoken by Palestinians in the Hebron area, which is similar to Arabic spoken by descendants of Palestinian refugees living in Jordan and south-western Syria. |

|||

Palestinian dialects contain layers of languages spoken in earlier times in the region, including [[Canaanite languages|Canaanite]], [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]] ([[Biblical Hebrew|Biblical]] and [[Mishnaic Hebrew|Mishnaic]]), [[Aramaic]] (particularly [[Western Aramaic languages|Western Aramaic]]), [[Persian language|Persian]], [[Greek language|Greek]], and [[Latin]]. As a result of the early modern period, Palestinian dialects were also influenced by [[Turkish language|Turkish]] and [[European languages]]. Since the founding of Israel in 1948, Palestinian dialects have been significantly influenced by [[Modern Hebrew]].<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal |last=Bassal |first=Ibrahim |date=2012 |title=Hebrew and Aramaic Substrata in Spoken Palestinian Arabic |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.13173/medilangrevi.19.2012.0085 |journal=Mediterranean Language Review |volume=19 |pages=85–104 |jstor=10.13173/medilangrevi.19.2012.0085 |issn=0724-7567}}</ref> |

|||

== History == |

== History == |

||

Prior to their adoption of the Arabic language from the seventh century onwards, most of the [[Demographic history of Palestine (region)|inhabitants of Palestine]] spoke varieties of [[Western Aramaic languages|Palestinian Aramaic]] ([[Jewish Palestinian Aramaic|Jewish]] , [[Christian Palestinian Aramaic|Christian]] , [[Samaritan Aramaic language|Samaritan]]) as a native language . [[Koine Greek]] was used among the Hellenized elite and aristocracy , and [[Mishnaic Hebrew|Mishanic Hebrew]] for liturgical purposes . |

|||

The variations between dialects probably reflect the different historical steps of [[Arabization]] of Palestine. |

|||

The [[Negev|Negev desert]] was under the rule of the [[Nabataean Kingdom|Nabatean Kingdom]] for the greater part of [[Classical antiquity]] , and included settlements such as Mahoza and [[Ein Gedi|Ein-Gedi]] where [[Judea|Judean]] and [[Nabataeans|Nabatean]] populations lived in alongside each other , as documented by the [[Babatha]] archive which dates to the second century . The earliest [[Old Arabic]] inscription most resembling of [[Classical Arabic]] is found in [[Avdat|Ayn Avadat]] , being a poem dedicated to King [[Obodas I]] , known for defeating the [[Hasmonean dynasty|Hasmonean]] [[Alexander Jannaeus]] . Its date is estimated between 79 and 120 CE , but no later than 150 CE at most.<ref>{{Cite web |title=A First/Second Century Arabic Inscription Of `En `Avdat |url=https://www.islamic-awareness.org/history/islam/inscriptions/avdat |access-date=2024-06-15 |website=www.islamic-awareness.org}}</ref> |

|||

Prior to their adoption of the Arabic language in the seventh century, the inhabitants of Palestine predominantly spoke [[Jewish Palestinian Aramaic|Palestinian Aramaic]] (as witnessed, for example, in Palestinian Jewish and Palestinian Christian literature), as well as [[Greek language|Greek]] (probably in the upper or trader social classes), and some remaining traces of [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]]. At that time in history, Arabic-speaking people living in the Negev desert or in the Jordan desert beyond Zarqa, Amman or Karak had no significant influence.{{Citation needed|date=May 2019}} |

|||

The Nabataeans tended to adopt Aramaic as a written language as shown in the [[Nabataean Aramaic|Nabataean language]] texts of [[Petra]],<ref name=":2" /> as well as a [[Lingua franca|Lingua Franca]] . [[Nabataean Aramaic|Nabatean]] and [[Western Aramaic languages|Palestinian Aramaic]] dialects would both have been thought of as “Aramaic” , and almost certainly have been mutually comprehensible. Additionally, occasional Arabic [[Loanword|loanwords]] can be found in the Jewish Aramaic documents of the [[Dead Sea Scrolls]].<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal|last=Macdonald|first=Michael C. A.|title=How much can we know about language and literacy in Roman Judaea? A review|url=https://www.academia.edu/38960413|journal=Journal of Roman Archaeology|year=2017 |volume=30|pages=832–842|doi=10.1017/S1047759400074882|s2cid=232343804|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

The [[ |

The [[Arabization|adoption of Arabic]] among the local population occurred most probably in several waves. After the [[Early Muslim conquests|Early Muslim]] Arabians took control of the area, so as to maintain their regular activity, the upper classes had to quickly become fluent in the language of the new rulers who most probably were only few. The prevalence of Northern Levantine features in the urban dialects until the early 20th century, as well as in the dialect of [[Samaritans]] in [[Nablus]] (with systematic imala of /a:/) tends to show that a first layer of Arabization of urban upper classes could have led to what is now urban Levantine. Then, the main phenomenon could have been the slow countryside shift of Aramaic-speaking villages to Arabic under the influence of Arabized elites, leading to the emergence of the rural Palestinian dialects{{Citation needed|date=July 2013}}. This scenario is consistent with several facts. |

||

* The rural forms can be correlated with features also observed in the few Syrian villages where use of Aramaic has been retained up to this day. Palatalisation of /k/ (but of /t/ too), pronunciation [kˤ] of /q/ for instance. Note that the first also exists in [[Najdi Arabic]] and [[Gulf Arabic]], but limited to palatal contexts (/k/ followed by i or a). Moreover, those Eastern dialects have [g] or [dʒ] for /q/ {{Citation needed|date=July 2013}}. |

* The rural forms can be correlated with features also observed in the few Syrian villages where use of Aramaic has been retained up to this day. Palatalisation of /k/ (but of /t/ too), pronunciation [kˤ] of /q/ for instance. Note that the first also exists in [[Najdi Arabic]] and [[Gulf Arabic]], but is limited to palatal contexts (/k/ followed by i or a). Moreover, those Eastern dialects have [g] or [dʒ] for /q/ {{Citation needed|date=July 2013}}. |

||

* The less-evolutive urban forms can be explained by a limitation owed to the contacts urban trader classes had to maintain with Arabic speakers of other towns in Syria or Egypt. |

* The less-evolutive urban forms can be explained by a limitation owed to the contacts urban trader classes had to maintain with Arabic speakers of other towns in Syria or Egypt. |

||

* The Negev |

* The Negev Bedouin dialect shares a number of features with Bedouin Hejazi dialects (unlike Urban Hejazi). |

||

== Differences compared to other Levantine Arabic dialects == |

== Differences compared to other Levantine Arabic dialects == |

||

| Line 49: | Line 55: | ||

The dialects spoken by the Arabs of the Levant – the Eastern shore of the Mediterranean – or [[Levantine Arabic]], form a group of dialects of Arabic. Arabic manuals for the "Syrian dialect" were produced in the early 20th century,<ref>Crow, F.E., ''Arabic manual: a colloquia handbook in the Syrian dialect, for the use of visitors to Syria and Palestine, containing a simplified grammar, a comprehensive English and Arabic vocabulary and dialogues'', Luzac & co, London, 1901</ref> and in 1909 a specific "Palestinean Arabic" manual was published. |

The dialects spoken by the Arabs of the Levant – the Eastern shore of the Mediterranean – or [[Levantine Arabic]], form a group of dialects of Arabic. Arabic manuals for the "Syrian dialect" were produced in the early 20th century,<ref>Crow, F.E., ''Arabic manual: a colloquia handbook in the Syrian dialect, for the use of visitors to Syria and Palestine, containing a simplified grammar, a comprehensive English and Arabic vocabulary and dialogues'', Luzac & co, London, 1901</ref> and in 1909 a specific "Palestinean Arabic" manual was published. |

||

The Palestinian Arabic dialects are varieties of Levantine Arabic because they display the following characteristic Levantine features |

The Palestinian Arabic dialects are varieties of Levantine Arabic because they display the following characteristic Levantine features: |

||

* A conservative stress pattern, closer to Classical Arabic than anywhere else in the Arab world. |

* A conservative stress pattern, closer to Classical Arabic than anywhere else in the Arab world. |

||

* The indicative imperfect with a b- prefix |

* The indicative imperfect with a b- prefix |

||

* A very frequent [[Imāla]] of the feminine ending in front consonant context (names in -eh). |

* A very frequent [[Imāla]] of the feminine ending in front consonant context (names in -eh). |

||

* A [ʔ] realisation of /q/ in the cities, and a [q] realisation of /q/ by the |

* A [ʔ] realisation of /q/ in the cities, and a [q] realisation of /q/ by the [[Druze]]{{citation needed|date=July 2021}}{{dubious|date=December 2018}}, and more variants (including [k]) in the countryside. |

||

* A shared lexicon |

* A shared lexicon |

||

| Line 60: | Line 66: | ||

* Phonetically, Palestinian dialects differ from Lebanese regarding the classical diphthongs /aj/ and /aw/, which have simplified to [eː] and [o:] in Palestinian dialects as in Western Syrian, while in Lebanese they have retained a diphthongal pronunciation: [eɪ] and [oʊ]. |

* Phonetically, Palestinian dialects differ from Lebanese regarding the classical diphthongs /aj/ and /aw/, which have simplified to [eː] and [o:] in Palestinian dialects as in Western Syrian, while in Lebanese they have retained a diphthongal pronunciation: [eɪ] and [oʊ]. |

||

* Palestinian dialects differ from Western Syrian as far as short stressed /i/ and /u/ are concerned: in Palestinian they keep a more or less open [ɪ] and [ʊ] pronunciation, and are not neutralised to [ə] as in Syrian. |

* Palestinian dialects differ from Western Syrian as far as short stressed /i/ and /u/ are concerned: in Palestinian they keep a more or less open [ɪ] and [ʊ] pronunciation, and are not neutralised to [ə] as in Syrian. |

||

* The Lebanese and Syrian dialects are more prone to [[imāla]] of /a:/ than the Palestinian dialects are. For instance شتا 'winter' is ['ʃɪta] in Palestinian but ['ʃəte] in Lebanese and Western Syrian. Some Palestinian dialects ignore imala totally (e.g. Gaza). |

* The Lebanese and Syrian dialects are more prone to [[imāla]] of /a:/ than the Palestinian dialects are. For instance شتا 'winter' is ['ʃɪta] in Palestinian but ['ʃəte] in Lebanese and Western Syrian. Some Palestinian dialects ignore imala totally (e.g. Gaza). Those dialects that prominently demonstrate imāla of /a:/ (e.g. Nablus) are distinct among Palestinian dialects. |

||

* In morphology, the plural personal pronouns are إحنا['ɪħna] 'we', همه['hʊmme] 'they', كم-[-kʊm] 'you', هم- [-hʊm] 'them' in Palestinian, while they are in Syria/Lebanon نحنا['nɪħna] 'we', هنه['hʊnne] 'they', كن-[-kʊn] 'you', هن- [-hʊn] 'them'. The variants كو [-kʊ] 'you', ـهن [-hen] ' |

* In morphology, the plural personal pronouns are إحنا ['ɪħna] 'we', همه ['hʊmme] also hunne [هنه] 'they',[ كو] [ku] كم- [-kʊm] 'you', هم- [-hʊm] هني [henne]'them' in Palestinian, while they are in Syria/Lebanon نحنا ['nɪħna] 'we', هنه ['hʊnne] 'they', كن-[-kʊn] 'you', هن- [-hʊn] 'them'. The variants كو [-kʊ] 'you', ـهن [-hen] 'them', and هنه [hinne] 'they' are used in Northern Palestinian. |

||

* The conjugation of the imperfect 1st and 3rd person masculine has different prefix vowels. Palestinians say بَكتب['baktʊb] 'I write' بَشوف[baʃuːf] 'I see' where Lebanese and Syrians say بِكتب['bəktʊb] and بْشوف[bʃuːf]. In the 3rd person masculine, Palestinians say بِكتب['bɪktʊb] 'He writes' where Lebanese and Western Syrians say بيَكتب['bjəktʊb]. |

* The conjugation of the imperfect 1st and 3rd person masculine has different prefix vowels. Palestinians say بَكتب ['baktʊb] 'I write' بَشوف [baʃuːf] 'I see' where Lebanese and Syrians say بِكتب ['bəktʊb] and بْشوف [bʃuːf]. In the 3rd person masculine, Palestinians say بِكتب['bɪktʊb] 'He writes' where Lebanese and Western Syrians say بيَكتب ['bjəktʊb]. |

||

* Hamza-initial verbs commonly have an [o:] prefix sound in the imperfect in Palestinian. For example, Classical Arabic has اكل /akala/ 'to eat' in the perfect tense, and آكل /aːkulu/ with [a:] sound in the first person singular imperfect. The common equivalent in Palestinian Arabic is اكل /akal/ in the perfect, with imperfect 1st person singular بوكل /boːkel/ (with the indicative b- prefix.) Thus, in the Galilee and Northern West Bank, the colloquial for the verbal expression, "I am eating" or "I eat" is commonly ['bo:kel] / ['bo:tʃel], rather than ['ba:kʊl] used in the Western Syrian dialect. Note however that ['ba:kel] or even ['ba:kʊl] are used in the South of Palestine. |

* Hamza-initial verbs commonly have an [o:] prefix sound in the imperfect in Palestinian. For example, Classical Arabic has اكل /akala/ 'to eat' in the perfect tense, and آكل /aːkulu/ with [a:] sound in the first person singular imperfect. The common equivalent in Palestinian Arabic is اكل /akal/ in the perfect, with imperfect 1st person singular بوكل /boːkel/ (with the indicative b- prefix.) Thus, in the Galilee and Northern West Bank, the colloquial for the verbal expression, "I am eating" or "I eat" is commonly ['bo:kel] / ['bo:tʃel], rather than ['ba:kʊl] used in the Western Syrian dialect. Note however that ['ba:kel] or even ['ba:kʊl] are used in the South of Palestine. |

||

* The conjugation of the imperative is different too. 'Write!' is اكتب ['ʊktʊb] in Palestinian, but كتوب [ktoːb], with different stress and vowel and length, in Lebanese and Western Syrian. |

* The conjugation of the imperative is different too. 'Write!' is اكتب ['ʊktʊb] in Palestinian, but كتوب [ktoːb], with different stress and vowel and length, in Lebanese and Western Syrian. |

||

* For the [[Negation in Arabic|negation]] of verbs and prepositional pseudo-verbs, Palestinian, like Egyptian, typically suffixes ش [ʃ] on top of using the preverb negation /ma/, e.g. 'I don't write' is مابكتبش [ma bak'tʊbʃ] in Palestinian, but مابكتب [ma 'bəktʊb] in Northern Levantine (although some areas in southern Lebanon utilise the ش [ʃ] suffix). However, unlike Egyptian, Palestinian allows for ش [ʃ] without the preverb negation /ma/ in the present tense, e.g. بكتبش [bak'tubɪʃ]. |

* For the [[Negation in Arabic|negation]] of verbs and prepositional pseudo-verbs, Palestinian, like Egyptian, typically suffixes ش [ʃ] on top of using the preverb negation /ma/, e.g. 'I don't write' is مابكتبش [ma bak'tʊbʃ] in Palestinian, but مابكتب [ma 'bəktʊb] in Northern Levantine (although some areas in southern Lebanon utilise the ش [ʃ] suffix). However, unlike Egyptian, Palestinian allows for ش [ʃ] without the preverb negation /ma/ in the present tense, e.g. بكتبش [bak'tubɪʃ]. |

||

* In vocabulary, Palestinian is closer to Lebanese than to Western Syrian, e.g. 'is not' is مش [məʃ] in both Lebanese and Palestinian (although in a few villages مهوش [mahuʃ] and مهيش [mahiʃ], which are found in Maltese and North African dialects, are used) while it is مو [mu] in Syrian; 'How?' is كيف [kiːf] in Lebanese and Palestinian while it is شلون [ʃloːn] in Syrian |

* In vocabulary, Palestinian is closer to Lebanese than to Western Syrian, e.g. 'is not' is مش [məʃ] in both Lebanese and Palestinian (although in a few villages مهوش [mahuʃ] and مهيش [mahiʃ], which are found in Maltese and North African dialects, are used) while it is مو [mu] in Syrian; 'How?' is كيف [kiːf] in Lebanese and Palestinian while it is شلون [ʃloːn] in Syrian (though كيف is also used) . However, Palestinian also shares items with [[Egyptian Arabic]], e.g. 'like' (prep.) is زي [zejj] in Palestinian in addition to مثل [mɪtl], as found in Syrian and Lebanese Arabic. |

||

There are also typical Palestinian words that are [[shibboleth]]s in the Levant. |

There are also typical Palestinian words that are [[shibboleth]]s in the Levant. |

||

* A frequent Palestinian إشي ['ɪʃi] 'thing, something', as opposed to شي [ʃi] in Lebanon and Syria. |

* A frequent Palestinian إشي ['ɪʃi] 'thing, something', as opposed to شي [ʃi] in Lebanon and Syria. |

||

* Besides common Levantine هلق ['hallaʔ] 'now', Central Rural dialects around Jerusalem and Ramallah use هالقيت [halke:t] (although [halʔe:t] is used in some cities such as Tulkarm, Hebron, and Nablus alongside هلق[hallaʔ] (both from هالوقت /halwaqt/ ) and northern Palestinians use إسا['ɪssɑ], إساع ['ɪssɑʕ], and هسة [hassɑ](from الساعة/ɪs:ɑ:ʕɑ/). Peasants in the southern West Bank also use هالحين [halaħin] or هالحينة [halħina] (both from هذا الحين [haːða ‘alħin]) |

* Besides common Levantine هلق ['hallaʔ] 'now', Central Rural dialects around Jerusalem and Ramallah use هالقيت [halke:t] (although [halʔe:t] is used in some cities such as Tulkarm, Hebron, and Nablus alongside هلق [hallaʔ] (both from هالوقت /halwaqt/ ) and northern Palestinians use إسا ['ɪssɑ], إساع ['ɪssɑʕ], and هسة [hassɑ](from الساعة/ɪs:ɑ:ʕɑ/). Peasants in the southern West Bank also use هالحين [halaħin] or هالحينة [halħina] (both from هذا الحين [haːða ‘alħin]) |

||

*Some rural Palestinians use بقى [baqa] (meaning 'remained' in MSA) as a verb to be alongside the standard كان [ka:n] ([ka:na in MSA) |

*Some rural Palestinians use بقى [baqa] (meaning 'remained' in MSA) as a verb to be alongside the standard كان [ka:n] ([ka:na in MSA) |

||

==Social and geographic dialect structuration== |

==Social and geographic dialect structuration== |

||

As is very common in Arabic-speaking countries, the [[Varieties of Arabic|Arabic dialect]] spoken by a person depends on both the region of origin , and socio-economic class. The [[Palestinian hikaye|hikaye]], a form of women's oral literature inscribed to UNESCO's list of [[Intangible Cultural Heritage of Palestine]], is recited in both the urban and rural dialects of Palestinian Arabic.<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |last=Rivoal |first=Isabelle |date=2001-01-01 |title=Susan Slyomovics, The Object of Memory. Arabs and Jews Narrate the Palestinian Village |url=https://journals.openedition.org/lhomme/6701 |journal=L'Homme. Revue française d'anthropologie |language=fr |issue=158–159 |pages=478–479 |doi=10.4000/lhomme.6701 |issn=0439-4216|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Timothy |first=Dallen J. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XRypDwAAQBAJ&dq=%22Palestinian+hikaye%22+-wikipedia&pg=PT123 |title=Routledge Handbook on Tourism in the Middle East and North Africa |date=2018-12-07 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-317-22923-0 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

As is very common in Arabic-speaking countries, the dialect spoken by a person depends on both the region he/she comes from, and the social group he/she belongs to. |

|||

===Palestinian urban dialects=== |

===Palestinian urban dialects=== |

||

The Urban ('madani') dialects resemble closely northern Levantine Arabic dialects, that is, the colloquial variants of western [[Syria]] and [[Lebanon]].<ref name="Sociolinguistics/Soziolinguistik 3: An International Handbook">{{cite book|last=Ammon|first=Ulrich|title=Sociolinguistics/Soziolinguistik 3: An International Handbook of the Science|year=2006|pages=1922|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LMZm0w0k1c4C& |

The Urban ('madani') dialects resemble closely northern Levantine Arabic dialects, that is, the colloquial variants of western [[Syria]] and [[Lebanon]].<ref name="Sociolinguistics/Soziolinguistik 3: An International Handbook">{{cite book|last=Ammon|first=Ulrich|title=Sociolinguistics/Soziolinguistik 3: An International Handbook of the Science|year=2006|pages=1922|publisher=Walter de Gruyter |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LMZm0w0k1c4C&q=levantine%20arabic%20influences&pg=PR4|isbn=9783110184181}}</ref> This fact, that makes the urban dialects of the Levant remarkably homogeneous, is probably due to the trading network among cities in [[Ottoman Syria]], or to an older Arabic dialect layer closer to the [[North Mesopotamian Arabic]] (the 'qeltu dialects"). |

||

Urban dialects are characterised by the [ʔ] ([[hamza]]) pronunciation of ق [[qoph|qaf]], the simplification of interdentals as dentals plosives, i.e. |

Urban dialects are characterised by the [ʔ] ([[hamza]]) pronunciation of {{lang|ar|ق}} [[qoph|qaf]], the simplification of interdentals as dentals plosives, i.e. {{lang|ar|ث}} as [t], {{lang|ar|ذ}} as [d] and both {{lang|ar|ض}} and {{lang|ar|ظ}} as [dˤ]. In borrowings from [[Modern Standard Arabic]], these interdental consonants are realised as dental sibilants, i.e. {{lang|ar|ث}} as [s], {{lang|ar|ذ}} as [z] and ظ as [zˤ] but {{lang|ar|ض}} is kept as [dˤ]. The Druzes have a dialect that may be classified with the Urban ones,{{dubious|date=December 2018}} with the difference that they keep the uvular pronunciation of {{lang|ar|ق}} qaf as [q]. The urban dialects also ignore the difference between masculine and feminine in the plural pronouns انتو ['ɪntu] is both 'you' (masc. plur.) and 'you' (fem. plur.), and ['hʊmme] is both 'they' (masc.) and 'they' (fem.) |

||

===Rural varieties=== |

===Rural varieties=== |

||

Rural or farmer ('[[fellah|fallahi]]') variety is retaining the interdental consonants, and is closely related with rural dialects in the outer southern Levant and in Lebanon. They keep the distinction between masculine and feminine plural pronouns, e.g. انتو ['ɪntu] is 'you' (masc.) while انتن ['ɪntɪn] is 'you' (fem.), and همه ['hʊmme] is 'they' (masc.) while هنه ['hɪnne] is 'they' (fem.). The three rural groups in the region are the following: |

Rural or farmer ('[[fellah|fallahi]]') variety is retaining the interdental consonants, and is closely related with rural dialects in the outer southern Levant and in Lebanon. They keep the distinction between masculine and feminine plural pronouns, e.g. انتو ['ɪntu] is 'you' (masc.) while انتن ['ɪntɪn] is 'you' (fem.), and همه ['hʊmme] is 'they' (masc.) while هنه ['hɪnne] is 'they' (fem.). The three rural groups in the region are the following: |

||

* Central rural Palestinian (From Nazareth to Bethlehem, including Jaffa countryside) exhibits a very distinctive feature with pronunciation of ك 'kaf' as [tʃ] 'tshaf' (e.g. كفية 'keffieh' as [tʃʊ'fijje]) and ق 'qaf' as [[pharyngealization|pharyngealised]] /k/ i.e. [kˤ] 'kaf' (e.g. قمح 'wheat' as [kˤɑmᵊħ]). This k > tʃ sound change is not conditioned by the surrounding sounds in Central Palestinian. This combination is unique in the whole Arab world, but could be related to the 'qof' transition to 'kof' in the Aramaic dialect spoken in [[Ma'loula]], north of [[Damascus]]. |

|||

* North Galilean rural dialect – does not feature the k > tʃ palatalisation, and many of them have kept the [q] realisation of ق (e.g. Maghār, Tirat Carmel). In the very north, they announce dialect thats is more closely to the Northern Levantine dialects with n-ending pronouns such as كن-[-kʊn] 'you', هن- [-hʊn] 'them' (Tarshiha, etc.). |

|||

* Central rural Palestinian (From Nazareth to Bethlehem, including Jaffa countryside) exhibits a very distinctive feature with pronunciation of ك 'kaf' as [tʃ] 'tshaf' (e.g. كفية 'keffieh' as [tʃʊ'fijje]) and ق 'qaf' as [[pharyngealization|pharyngealised]] /k/ i.e. [kˤ] 'kaf' (e.g. قمح 'wheat' as [kˤɑmᵊħ]). This k > tʃ sound change is not conditioned by the surrounding sounds in Central Palestinian. This combination is unique in the whole Arab world, but could be related to the 'qof' transition to 'kof' in the [[Western Neo-Aramaic|Aramaic dialect spoken]] in [[Ma'loula]], north of [[Damascus]]. |

|||

* Southern outer rural Levantine Arabic (to the south of an Isdud/[[Ashdod]]-[[Bethlehem]] line) has k > tʃ only in presence of front vowels (ديك 'rooster' is [di:tʃ] in the singular but the plural ديوك 'roosters' is [dju:k] because u prevents /k/ from changing to [tʃ]). In this dialect ق is not pronounced as [k] but instead as [g]. This dialect is actually very similar to northern Jordanian ([[Ajloun]], [[Irbid]]) and the dialects of Syrian [[Hauran]]. In Southern rural Palestinian, the feminine ending often remains [a]. |

* Southern outer rural Levantine Arabic (to the south of an Isdud/[[Ashdod]]-[[Bethlehem]] line) has k > tʃ only in presence of front vowels (ديك 'rooster' is [di:tʃ] in the singular but the plural ديوك 'roosters' is [dju:k] because u prevents /k/ from changing to [tʃ]). In this dialect ق is not pronounced as [k] but instead as [g]. This dialect is actually very similar to northern Jordanian ([[Ajloun]], [[Irbid]]) and the dialects of Syrian [[Hauran]]. In Southern rural Palestinian, the feminine ending often remains [a]. |

||

* North Galilean rural dialect - does not feature the k > tʃ palatalisation, and many of them have kept the [q] realisation of ق (e.g. Maghār, Tirat Carmel). In the very north, they announce the Northern Levantine Lebanese dialects with n-ending pronouns such as كن-[-kʊn] 'you', هن- [-hʊn] 'them' (Tarshiha, etc.). |

|||

===Bedouin variety=== |

===Bedouin variety=== |

||

The Bedouins of Southern Levant use two different ('[[Bedouin|badawi]]') dialects in [[Galilee]] and the [[Negev]]. The Negev desert Bedouins, who are also present in [[State of Palestine|Palestine]] and [[Gaza Strip]] use a dialect closely related to those spoken in the Hijaz, and in the Sinai. Unlike them, the Bedouins of Galilee speak a dialect related to those of the [[Syrian Desert]] and [[Najd]], which indicates their arrival to the region is relatively recent. The Palestinian resident Negev Bedouins, who are present around Hebron and Jerusalem have a specific vocabulary, they maintain the interdental consonants, they do not use the ش-[-ʃ] negative suffix, they always realise ك /k/ as [k] and ق /q/ as [g], and distinguish plural masculine from plural feminine pronouns, but with different forms as the rural speakers. |

The Bedouins of Southern Levant use two different ('[[Bedouin|badawi]]') dialects in [[Galilee]] and the [[Negev]]. The Negev desert Bedouins, who are also present in [[State of Palestine|Palestine]] and [[Gaza Strip]] use a dialect closely related to those spoken in the Hijaz, and in the Sinai. Unlike them, the Bedouins of Galilee speak a dialect related to those of the [[Syrian Desert]] and [[Najd]], which indicates their arrival to the region is relatively recent. The Palestinian resident Negev Bedouins, who are present around Hebron and Jerusalem have a specific vocabulary, they maintain the interdental consonants, they do not use the ش- [-ʃ] negative suffix, they always realise ك /k/ as [k] and ق /q/ as [g], and distinguish plural masculine from plural feminine pronouns, but with different forms as the rural speakers. |

||

=== Sephardic variety === |

|||

As [[Sephardic Jews]] were [[Alhambra Decree|expelled]] after the conclusion of the [[Reconquista]] , they established [[Old Yishuv|communities]] in Ottoman Palestine in Jerusalem and Galilee under the invitation of Sultan [[Bayezid II]] . Their [[Maghrebi Arabic|Maghrebi]] [[Judeo-Arabic dialects|Judeo-Arabic]] dialect mixed with Palestinian Arabic. It peaked at 10,000 speakers and thrived alongside [[Yiddish]] among [[Ashkenazi Jews|Ashkenazis]] until the 20th century in [[Mandatory Palestine]]. |

|||

Today it is nearly extinct , with only 5 speakers remaining in the Galilee.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Judeo-Arabic |url=https://www.jewishlanguages.org/judeo-arabic |access-date=2024-01-25 |website=Jewish Languages |language=en}}</ref> It contained influence from [[Judeo-Moroccan Arabic]] and influence [[Judeo-Lebanese Arabic]] and [[Judeo-Syrian Arabic]].<ref>{{Citation |last=Geva-Kleinberger |first=Aharon |title=Languages in Jewish Communities, Past and Present |chapter=Judeo-Arabic in the Holy Land and Lebanon |date=2018-11-05 |pages=569–580 |chapter-url=https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9781501504631-021/html |access-date=2024-01-25 |publisher=De Gruyter Mouton |language=en |doi=10.1515/9781501504631-021 |isbn=978-1-5015-0463-1|s2cid=134826368 }}</ref> |

|||

===Current evolutions=== |

===Current evolutions=== |

||

| Line 94: | Line 106: | ||

The Rural description given above is moving nowadays with two opposite trends. On the one hand, urbanisation gives a strong influence power to urban dialects. As a result, villagers may adopt them at least in part, and Beduin maintain a two-dialect practice. On the other hand, the individualisation that comes with urbanisation make people feel more free to choose the way they speak than before, and in the same way as some will use typical Egyptian or Lebanese features as [le:] for [le:ʃ], others may use typical rural features such as the rural realisation [kˤ] of ق as a pride reaction against the stigmatisation of this pronunciation. |

The Rural description given above is moving nowadays with two opposite trends. On the one hand, urbanisation gives a strong influence power to urban dialects. As a result, villagers may adopt them at least in part, and Beduin maintain a two-dialect practice. On the other hand, the individualisation that comes with urbanisation make people feel more free to choose the way they speak than before, and in the same way as some will use typical Egyptian or Lebanese features as [le:] for [le:ʃ], others may use typical rural features such as the rural realisation [kˤ] of ق as a pride reaction against the stigmatisation of this pronunciation. |

||

== Phonology == |

|||

=== Consonants === |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center" |

|||

! colspan="2" rowspan="2" | |

|||

! colspan="2" | [[Labial consonant|Labial]] |

|||

! colspan="2" | [[Dental fricative|Interdental]] |

|||

! colspan="2" | [[Dental consonant|Dental]]/[[Alveolar consonant|Alveolar]] |

|||

! rowspan="2" | [[Palatal consonant|Palatal]] |

|||

! colspan="2" | [[Velar consonant|Velar]] |

|||

! rowspan="2" | [[Uvular consonant|Uvular]] |

|||

! rowspan="2" | [[Pharyngeal consonant|Pharyngeal]] |

|||

! rowspan="2" | [[Glottal consonant|Glottal]] |

|||

|- style="font-size: 80%;" |

|||

!plain |

|||

![[Emphatic consonant|emph.]] |

|||

! plain |

|||

! [[Emphatic consonant|emph.]] |

|||

! plain |

|||

! [[Emphatic consonant|emph.]] |

|||

! plain |

|||

! [[Emphatic consonant|emph.]] |

|||

|- |

|||

! colspan="2" style="text-align: left;" | [[Nasal consonant|Nasal]] |

|||

| {{IPA link|m}} |

|||

| {{IPA link|mˤ}} |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| {{IPA link|n}} |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

! rowspan="2" style="text-align: left;" | [[Stop consonant|Stop]] |

|||

! style="text-align: left; font-size: 80%;" | [[Voiceless consonant|voiceless]] |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| {{IPA link|t}} |

|||

| {{IPA link|tˤ}} |

|||

| ({{IPA link|t͡ʃ}}) |

|||

| {{IPA link|k}} |

|||

| {{IPA link|kˤ}} |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| {{IPA link|ʔ}} |

|||

|- |

|||

! style="text-align: left; font-size: 80%;" | [[Voiced consonant|voiced]] |

|||

| {{IPA link|b}} |

|||

| {{IPA link|bˤ}} |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| {{IPA link|d}} |

|||

| {{IPA link|dˤ}} |

|||

| {{IPA link|d͡ʒ}} |

|||

| {{IPA link|ɡ}} |

|||

| |

|||

| ({{IPA link|ɢ}}) |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

! rowspan="2" style="text-align: left;" | [[Fricative consonant|Fricative]] |

|||

! style="text-align: left; font-size: 80%;" | [[Voiceless consonant|voiceless]] |

|||

| {{IPA link|f}} |

|||

| |

|||

| {{IPA link|θ}} |

|||

| |

|||

| {{IPA link|s}} |

|||

| {{IPA link|sˤ}} |

|||

| {{IPA link|ʃ}} |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| {{IPA link|χ}} |

|||

| {{IPA link|ħ}} |

|||

| {{IPA link|h}} |

|||

|- |

|||

! style="text-align: left; font-size: 80%;" | [[Voiced consonant|voiced]] |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| {{IPA link|ð}} |

|||

| {{IPA link|ðˤ}} |

|||

| {{IPA link|z}} |

|||

| {{IPA link|zˤ}} |

|||

| {{IPA link|ʒ}} |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| {{IPA link|ʁ}} |

|||

| {{IPA link|ʕ}} |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

! colspan="2" style="text-align: left;" | [[Trill consonant|Trill]] |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| ({{IPA link|r}}) |

|||

| {{IPA link|ˤ|rˤ}} |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

! colspan="2" style="text-align: left;" | [[Approximant consonant|Approximant]] |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| {{IPA link|l}} |

|||

| {{IPA link|lˤ}} |

|||

| {{IPA link|j}} |

|||

| {{IPA link|w}} |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

|} |

|||

* Sounds {{IPA|/θ, ð, ðˤ, t͡ʃ, d͡ʒ/}} are mainly heard in both the rural and Bedouin dialects. Sounds {{IPA|/zˤ/}} and /{{IPA|ʒ/}} are mainly heard in the urban dialects. {{IPA|/kˤ/}} is heard in the rural dialects. |

|||

* {{IPA|/ɡ/}} is heard in the Bedouin dialects, and may also be heard as a uvular {{IPA|[ɢ]}}. |

|||

* {{IPA|[t͡ʃ]}} mainly occurs as a palatalization of {{IPA|/k/}}, and is only heard in a few words as phonemic. In some rural dialects {{IPA|[t͡ʃ]}} has replaced {{IPA|/k/}} as a phoneme. |

|||

* {{IPA|/rˤ/}} may de-pharyngealize as {{IPA|[r]}} in certain phonetic environments. |

|||

* {{IPA|/ʁ/}} can also be heard as velar {{IPA|[ɣ]}} among some rural dialects. |

|||

* {{IPA|/b/}} can be heard as {{IPA|[p]}} within devoiced positions. |

|||

=== Vowels === |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center" |

|||

! |

|||

![[Front vowel|Front]] |

|||

![[Central vowel|Central]] |

|||

![[Back vowel|Back]] |

|||

|- align="center" |

|||

![[Close vowel|Close]] |

|||

|{{IPA link|i}} {{IPA link|iː}} |

|||

| |

|||

|{{IPA link|u}} {{IPA link|uː}} |

|||

|- align="center" |

|||

![[Mid vowel|Mid]] |

|||

|{{IPA link|e}} {{IPA link|eː}} |

|||

| |

|||

|{{IPA link|o}} {{IPA link|oː}} |

|||

|- align="center" |

|||

![[Open vowel|Open]] |

|||

| |

|||

|{{IPA link|a}} {{IPA link|aː}} |

|||

| |

|||

|} |

|||

* The short vowel {{IPA|/a/}} is typically heard as {{IPA|[ə]}}, when in unstressed form. |

|||

* {{IPA|/a, aː/}} are heard as {{IPA|[ɑ, ɑː]}} when following and preceding a pharyngealized consonant. The short vowel {{IPA|/a/}} as {{IPA|[ɑ]}}, can also be raised as {{IPA|[ʌ]}} in lax form within closed syllables. |

|||

* {{IPA|/i, u/}} can be lowered to {{IPA|[ɪ, ʊ]}} when in lax form, or within the position of a post-velar consonant.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Shahin |first=Kimary N. |title=Palestinian Arabic |publisher=Leiden: Brill |year=2019 |isbn=978-90-04-17702-4 |location=In Kees Versteegh (ed.), Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics, Vol. II |pages=526–538}}</ref> |

|||

==Specific aspects of the vocabulary== |

==Specific aspects of the vocabulary== |

||

As Palestinian Arabic is spoken in the heartland of the Semitic languages, it has kept many typical |

As Palestinian Arabic is spoken in the heartland of the Semitic languages, it has kept many typical Semitic words. For this reason, it is relatively easy to guess how [[Modern Standard Arabic]] words map onto Palestinian Arabic Words. The list (Swadesh list) of basic words of Palestinian Arabic available on the Wiktionary (see ''external links'' below) may be used for this. However, some words are not transparent mappings from MSA, and deserve a description. This is due either to meaning changes in Arabic along the centuries – while MSA keeps the [[Classical Arabic]] meanings – or to the adoption of non-Arabic words (see below). Note that this section focuses on Urban Palestinian unless otherwise specified. |

||

'''Prepositional pseudo verbs''' |

'''Prepositional pseudo verbs''' |

||

| Line 141: | Line 311: | ||

|- |

|- |

||

|} |

|} |

||

In the perfect, they are preceded by كان [ |

In the perfect, they are preceded by كان [kaːn], e.g. ''we wanted'' is كان بدنا [kaːn 'bɪddna]. |

||

'''Relative clause''' |

'''Relative clause''' |

||

| Line 155: | Line 325: | ||

|- |

|- |

||

|Why? |

|Why? |

||

|ليش [ |

|ليش [leːʃ] |

||

|لماذا [ |

|لماذا [limaːðaː] |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|What? |

|What? |

||

|ايش [ |

|ايش [ʔeːʃ] or شو [ʃu] |

||

|ماذا [ |

|ماذا [maːðaː] |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|How? |

|How? |

||

|كيف [ |

|كيف [kiːf] |

||

|كيف [kaɪfa] |

|كيف [kaɪfa] |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|When? |

|When? |

||

|إيمتى [ |

|إيمتى [ʔeːmta] or وينتى [weːnta] |

||

|متى [ |

|متى [mataː] |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|Where? |

|Where? |

||

|وين [ |

|وين [weːn] |

||

|اين [ʔaɪna] |

|اين [ʔaɪna] |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|Who? |

|Who? |

||

|مين [ |

|مين [miːn] |

||

|من [man] |

|من [man] |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|} |

|} |

||

Note that it is tempting to consider the long [ |

Note that it is tempting to consider the long [iː] in مين [miːn] 'who?' as an influence of ancient Hebrew מי [miː] on Classical Arabic من [man], but it could be as well an analogy with the long vowels of the other interrogatives. |

||

'''Marking Indirect Object''' |

'''Marking Indirect Object''' |

||

| Line 190: | Line 360: | ||

* ... قلت إلها [ʔʊlt-''' 'ɪl(l)-ha''' ...] 'I told her ...' |

* ... قلت إلها [ʔʊlt-''' 'ɪl(l)-ha''' ...] 'I told her ...' |

||

* ... كتبت إلّي [katabt-''' 'ɪll-i''' ...] 'You wrote me ...' |

* ... كتبت إلّي [katabt-''' 'ɪll-i''' ...] 'You wrote me ...' |

||

'''Borrowings''' |

|||

Palestinians have borrowed words from the many languages they have been in contact with throughout history. For example, |

|||

* from Aramaic - especially in the place names, for instance there are several mountains called جبل الطور ['ʒabal ɪtˤ tˤuːɾ] where طور [tˤuːɾ] is just the Aramaic טור for 'mountain'. |

|||

* Latin left words in Levantine Arabic, not only those as قصر [ʔasˤɾ] < castrum 'castle' or قلم [ʔalam] < calamus which are also known in MSA, but also words such as طاولة [tˤa:wle] < tabula 'table', which are known in the Arab world. |

|||

* from Italian بندورة [ban'do:ra] < pomodoro 'tomato' |

|||

* from French كتو ['ketto] < gâteau 'cake' |

|||

* from English بنشر ['banʃar] < puncture, [trɪkk] < truck |

|||

* From Hebrew, especially the [[Arab citizens of Israel]] have adopted many [[Hebraism]]s, like {{transl|he|yesh}} {{script/Hebrew|יֵשׁ}} ("we did it!" - used as sports cheer) which has no real equivalent in Arabic. According to social linguist Dr. David Mendelson from [[Arab-Israeli peace projects#Givat Haviva.27s Jewish-Arab Center for Peace|Givat Haviva's Jewish-Arab Center for Peace]], there is an adoption of words from Hebrew in Arabic spoken in Israel where alternative native terms exist. According to linguist Mohammed Omara, of [[Bar-Ilan University]] some researchers call the Arabic spoken by Israeli Arabs ''Arabrew''. The list of words adopted contain: |

|||

** رمزور [ram'zo:r] from {{script/Hebrew|רַמְזוֹר}} 'traffic light' |

|||

** شمنيت ['ʃamenet] from {{script/Hebrew|שַׁמֶּנֶת}} 'sour cream' |

|||

** بسدر [be'seder] from {{script/Hebrew|בְּסֵדֶר}} 'O.K, alright' |

|||

** كوخفيت [koxa'vi:t] from {{script/Hebrew|כּוֹכָבִית}} 'asterisk' |

|||

** بلفون [pele'fo:n] from {{script/Hebrew|פֶּלֶאפוֹן}} 'cellular phone'. |

|||

Palestinians in the Palestinian territories sometimes refer to their brethren in Israel as "the b'seder Arabs" because of their adoption of the Hebrew word בְּסֵדֶר [beseder] for 'O.K.', (while Arabic is ماشي[ma:ʃi]). However words like {{transl|he|ramzor}} {{script/Hebrew|רַמְזוֹר}} 'traffic light' and {{transl|he|maḥsom}} {{script/Hebrew|מַחְסוֹם}} 'roadblock' have become a part of the general Palestinian vernacular. |

|||

The 2009 film ''[[Ajami (film)|Ajami]]'' is mostly spoken in Palestinian-Hebrew Arabic. |

|||

===Vowel harmony=== |

===Vowel harmony=== |

||

The most often cited example of [[vowel harmony]] in Palestinian Arabic is in the [[present tense]] [[Grammatical conjugation|conjugation]]s of verbs. If the root vowel is [[round vowel|rounded]], then the roundness spreads to other high vowels in the [[prefix]]. Vowel harmony in PA is also found in the [[nominal (linguistics)|nominal]] verbal domain. [[Suffix]]es are immune to rounding harmony, and vowels left of the stressed [[syllable]] do not have vowel harmony.<ref>Kenstowicz, Michael. 1981. Vowel Harmony in Palestinian Arabic: A Suprasegmental Analysis. Linguistics 19:449-465.</ref> |

The most often cited example of [[vowel harmony]] in Palestinian Arabic is in the [[present tense]] [[Grammatical conjugation|conjugation]]s of verbs. If the root vowel is [[round vowel|rounded]], then the roundness spreads to other high vowels in the [[prefix]]. Vowel harmony in PA is also found in the [[nominal (linguistics)|nominal]] verbal domain. [[Suffix]]es are immune to rounding harmony, and vowels left of the stressed [[syllable]] do not have vowel harmony.<ref>Kenstowicz, Michael. 1981. Vowel Harmony in Palestinian Arabic: A Suprasegmental Analysis. Linguistics 19:449-465.</ref> |

||

Palestinian Arabic has a regressive vowel harmony for these present tense conjugations: if the verb |

Palestinian Arabic has a regressive vowel harmony for these present tense conjugations: if the verb stem's main vowel is /u/, then the vowel in the prefix is also /u/, else the vowel is /i/. This is compared with [[standard Arabic]] (which can be seen as representative of other Arabic dialects), where the vowel in the prefix is consistently /a/.<ref>Abu-Salim, Issam. 1987. Vowel Harmony in Palestinian Arabic: A Metrical Perspective. Journal of Linguistics 23:1-24.</ref> |

||

Examples: |

Examples: |

||

| Line 223: | Line 374: | ||

*‘oven’: PA ‘''f'''u'''r'''u'''n’ (MSA, ‘''furn''’) |

*‘oven’: PA ‘''f'''u'''r'''u'''n’ (MSA, ‘''furn''’) |

||

*‘wedding’: PA ‘'''''U'''r'''u'''s''’ (MSA,‘'urs'’) |

*‘wedding’: PA ‘'''''U'''r'''u'''s''’ (MSA,‘'urs'’) |

||

== Borrowings in vocabulary == |

|||

Palestinians have borrowed words from the many languages they have been in contact with throughout history. For example, |

|||

=== Hebrew === |

|||

==== Modern ==== |

|||

From Hebrew, especially the [[Arab citizens of Israel]] have adopted many [[Hebraism]]s, like {{transl|he|yesh}} {{script/Hebrew|יֵשׁ}} ("we did it!" – used as sports cheer) which has no real equivalent in Arabic. According to sociolinguist David Mendelson from [[Arab-Israeli peace projects#Givat Haviva.27s Jewish-Arab Center for Peace|Givat Haviva's Jewish-Arab Center for Peace]], there is an adoption of words from Hebrew in Arabic spoken in Israel where alternative native terms exist. According to linguist Mohammed Omara, of [[Bar-Ilan University]] some researchers call the Arabic spoken by Israeli Arabs ''Arabrew'' (in Hebrew, ערברית ''"Aravrit''"). The list of words adopted contain: |

|||

** رمزور [ram'zo:r] from {{script/Hebrew|רַמְזוֹר}} 'traffic light' |

|||

** شمنيت ['ʃamenet] from {{script/Hebrew|שַׁמֶּנֶת}} 'sour cream' |

|||

** بسدر [be'seder] from {{script/Hebrew|בְּסֵדֶר}} 'O.K, alright' |

|||

** كوخفيت [koxa'vi:t] from {{script/Hebrew|כּוֹכָבִית}} 'asterisk' |

|||

** بلفون [bele'fo:n] from {{script/Hebrew|פֶּלֶאפוֹן}} 'cellular phone'. |

|||

Palestinians in the Palestinian territories sometimes refer to their brethren in Israel as "the b'seder Arabs" because of their adoption of the Hebrew word בְּסֵדֶר [beseder] for 'O.K.', (while Arabic is ماشي [ma:ʃi]). However words like {{transl|he|ramzor}} {{script/Hebrew|רַמְזוֹר}} 'traffic light' and {{transl|he|maḥsom}} {{script/Hebrew|מַחְסוֹם}} 'roadblock' have become a part of the general Palestinian vernacular. |

|||

The 2009 film ''[[Ajami (film)|Ajami]]'' is mostly spoken in Palestinian-Hebrew Arabic. |

|||

Interpretations of "Arabrew" are often colored by non-linguistic political and cultural factors,<ref name="Hawker">{{cite journal |author=Hawker |first=Nancy |year=2018 |title=The mirage of 'Arabrew': Ideologies for understanding Arabic-Hebrew contact |url=https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:0f99963f-8877-45d5-a9e8-85e72f18ca9e |journal=Language in Society |volume=47 |issue=2 |pages=219–244 |doi=10.1017/S0047404518000015 |s2cid=148862120}}</ref> but how contact with Hebrew is realized has been studied, and has been described in linguistic terms and in terms of how it varies. "Arabrew" as spoken by Palestinians and more generally Arab citizens of Israel has been described as classical [[codeswitching]] without much structural effect<ref name="Kheir">{{cite journal |author=Afifa Eve Kheir |year=2019 |title=The Matrix Language Turnover Hypothesis: The Case of the Druze Language in Israel |journal=Journal of Language Contact |volume=12 |issue=2 |pages=479–512 |doi=10.1163/19552629-01202008 |s2cid=202246511 |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name="Hawker" /> While the codeswitching by the majority of Arab or Palestinian citizens of Israel who are Christian or Muslim from the North or the Triangle is described as limited, more intense codeswitching is seen among Arabs who live in Jewish-majority settlements as well as Bedouin (in the South) who serve in the army, although this variety can still be called codeswitching, and does not involve any significant structural change deviating from the non-Hebrew influenced norm.<ref name="Kheir" /> For the most part among all Christian and Muslim Arabs in Israel, the impact of Hebrew contact on Palestinian Arabic is limited to borrowing of nouns, mostly for specialist vocabulary, plus a few discourse markers.<ref name="Hawker" /> However, this does not apply to the Arabic spoken by the Israeli Druze, which has been documented as manifesting much more intense contact effects, including the mixture of Arabic and Hebrew words within syntactic clauses, such as the use of a Hebrew preposition for an Arabic element and vice versa, and the adherence to gender and number agreement between Arabic and Hebrew elements (i.e. a Hebrew possessive adjective must agree with the gender of the Arabic noun it describes).<ref name="Kheir" /> While Hebrew definite articles can only be used for Hebrew nouns, Arabic definite articles are used for Hebrew nouns and are, in fact, the most common DP structure.<ref name="Kheir" /> |

|||

==== Ancient Hebrew ==== |

|||

* {{lang|ar|سفل}} ''sifil'' (bowl, mug) may be a Canaanite/Hebrew substrate.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

* {{lang|ar|جرجير}} [[Eruca vesicaria|"arugula"]] is regionally used in the sense of shrivelled olive. The Hebrew Bible uses it to refer to a grain (berry), while Mishnaic Hebrew used it to refer to both berries and shriveled olives.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

=== Aramaic === |

|||

*Especially in the place names, for instance there are several mountains called جبل الطور ['ʒabal ɪtˤ tˤuːɾ] where طور [tˤuːɾ] is just the Aramaic טור for 'mountain'. |

|||

=== Turkish === |

|||

* Oda for 'room' from Turkish oda. |

|||

*Kundara (or qundara) for 'shoe' from Turkish kundura. |

|||

* Dughri (دُغْرِيّ) for 'forward' from Turkish doğru |

|||

* Suffix -ji denoting a profession eg. kahwaji (café waiter) from Turkish kahveci. And sufraji, sabonji, etc. |

|||

=== European === |

|||

*Latin left words in Levantine Arabic, not only those as قصر [ʔasˤɾ] < castrum 'castle' or قلم [ʔalam] < calamus which are also known in MSA, but also words such as طاولة [tˤa:wle] < tabula 'table', which are known in the Arab world. |

|||

*from Italian بندورة [ban'do:ra] < pomodoro 'tomato' |

|||

* from French كتو ['ketto] < gâteau 'cake' |

|||

* from English بنشر ['banʃar] < puncture, [trɪkk] < truck |

|||

==Publications== |

==Publications== |

||

The [[Gospel of Mark]] was published in Palestinian Arabic in 1940,<ref>{{Cite book|title=Gospel of St. Mark in South Levantine Spoken Arabic.| |

The [[Gospel of Mark]] was published in Palestinian Arabic in 1940,<ref>{{Cite book|title=Gospel of St. Mark in South Levantine Spoken Arabic.|last1=Bishop|first1=E. F. F|last2=George|first2=Surayya|date=1940|location=Cairo|language=ar|oclc = 77662380}}</ref> with the [[Gospel of Matthew]] and the [[Epistle of James|Letter of James]] published in 1946.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://gochristianhelps.com/iccm/arabic/othehist.htm|title=Arabic--Other Bible History|website=gochristianhelps.com|access-date=2018-10-15}}</ref> |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

| Line 234: | Line 427: | ||

*[[Egyptian Arabic]] |

*[[Egyptian Arabic]] |

||

*[[Music of Palestine]] |

*[[Music of Palestine]] |

||

*[[ |

*[[Arabic language in Israel]] |

||

**[[Academy of the Arabic Language in Israel]] |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| Line 257: | Line 451: | ||

*Frank A. Rice, ''Eastern Arabic-English, English-Eastern Arabic: dictionary and phrasebook for the spoken Arabic of Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine/Israel and Syria''. New York: Hippocrene Books 1998 ({{ISBN|0-7818-0685-2}}) |

*Frank A. Rice, ''Eastern Arabic-English, English-Eastern Arabic: dictionary and phrasebook for the spoken Arabic of Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine/Israel and Syria''. New York: Hippocrene Books 1998 ({{ISBN|0-7818-0685-2}}) |

||

*H. Schmidt & P. E. Kahle, "Volkserzählungen aus Palaestina, gesammelt bei den Bauern von Bir-Zet". Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 1918. |

*H. Schmidt & P. E. Kahle, "Volkserzählungen aus Palaestina, gesammelt bei den Bauern von Bir-Zet". Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 1918. |

||

* {{cite journal|first=Ulrich |last=Seeger|language=de|title=Wörterbuch Palästinensisch – Deutsch|location= |

|||

Wiesbaden|publisher= Harrassowitz Verlag|year= 2022|journal=Semitica Viva|volume=XVII|issue=61}} |

|||

*Kimary N. Shahin, ''Palestinian Rural Arabic (Abu Shusha dialect)''. 2nd ed. University of British Columbia. LINCOM Europa, 2000 ({{ISBN|3-89586-960-0}}) |

*Kimary N. Shahin, ''Palestinian Rural Arabic (Abu Shusha dialect)''. 2nd ed. University of British Columbia. LINCOM Europa, 2000 ({{ISBN|3-89586-960-0}}) |

||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{Wikibooks|Levantine Arabic}} |

|||

{{Wiktionary cat|category=South Levantine Arabic language}} |

|||

* {{cite web|url=https://sites.google.com/nyu.edu/palestine-lexicon|title=The Open Palestinian Arabic Lexicon "Maknuune"|website=CAMeL Lab, New York University Abu Dhabi}} |

|||

* [http://www.uni-heidelberg.de/fakultaeten/philosophie/ori/semitistik/seeger_ramalla_en.html The Arabic dialect of central Palestine] |

* [http://www.uni-heidelberg.de/fakultaeten/philosophie/ori/semitistik/seeger_ramalla_en.html The Arabic dialect of central Palestine] |

||

* [http://langmedia.fivecolleges.edu/ |

* [http://langmedia.fivecolleges.edu/lbc-topics/207/183 Arabic in Jordan (Palestinian dialect)] |

||

* "[https://web.archive.org/web/20060308150505/http://www.ling.upenn.edu/~urih/Horesh_proposal.pdf Phonological change and variation in Palestinian Arabic as spoken inside Israel]", Dissertation Proposal by Uri Horesh, Philadelphia, December 12, 2003 ([[PDF]]) |

* "[https://web.archive.org/web/20060308150505/http://www.ling.upenn.edu/~urih/Horesh_proposal.pdf Phonological change and variation in Palestinian Arabic as spoken inside Israel]", Dissertation Proposal by Uri Horesh, Philadelphia, December 12, 2003 ([[PDF]]) |

||

* [http://www.tau.ac.il/humanities/semitic/Te'udaAbstracts.html#The%20Corpus%20of%20Spoken%20Palestinian%20Arabic%20%28CoSPA%29 The Corpus of Spoken Palestinian Arabic (CoSPA)], project description by Otto Jastrow. |

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20120516220852/http://www.tau.ac.il/humanities/semitic/Te'udaAbstracts.html#The%20Corpus%20of%20Spoken%20Palestinian%20Arabic%20%28CoSPA%29 The Corpus of Spoken Palestinian Arabic (CoSPA)], project description by Otto Jastrow. |

||

* [http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Appendix:Palestinian_Arabic_Swadesh_list Palestinian Arabic Swadesh list of basic vocabulary words] (from Wiktionary's [http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Appendix:Swadesh_lists Swadesh list appendix]) |

|||

{{Varieties of Arabic}} |

|||

{{ |

{{Levantine Arabic}} |

||

{{Varieties of Arabic}}{{Palestine topics}}{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Arabic languages]] |

|||

[[Category:Mashriqi Arabic]] |

|||

[[Category:Languages of the State of Palestine]] |

[[Category:Languages of the State of Palestine]] |

||

[[Category:Levantine Arabic]] |

|||

[[Category:South Levantine Arabic]] |

[[Category:South Levantine Arabic]] |

||

[[Category:Languages of Israel]] |

|||

Revision as of 06:36, 19 June 2024

| Palestinian Arabic | |

|---|---|

| اللهجة الفلسطينية | |

| Native to | State of Palestine, Israel |

| Region | Palestine |

Native speakers | 7.6 million (2024)[1] |

| Dialects |

|

| Arabic alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | (covered by apc) |

| Glottolog | sout3123 |

| |

Palestinian Arabic is a dialect continuum of mutually intelligible varieties of Levantine Arabic spoken by most Palestinians in Palestine, Israel and in the Palestinian diaspora.[2][3]

The Arabic dialects spoken in Palestine and Transjordan are not one more or less homogeneous linguistic unit, but rather a wide diversity of dialects belonging to various typologically diverse groupings due to geographical, historical, and socioeconomic circumstances.[4] In two dialect comparison studies, Palestinian Arabic was found to be the closest Arabic dialect to Modern Standard Arabic,[5] mainly the dialect of the people in Gaza Strip.[6] Further dialects can be distinguished within Palestine, such as spoken in the northern West Bank, that spoken by Palestinians in the Hebron area, which is similar to Arabic spoken by descendants of Palestinian refugees.

Palestinian dialects contain layers of languages spoken in earlier times in the region, including Canaanite, Hebrew (Biblical and Mishnaic), Aramaic (particularly Western Aramaic), Persian, Greek, and Latin. As a result of the early modern period, Palestinian dialects were also influenced by Turkish and European languages. Since the founding of Israel in 1948, Palestinian dialects have been significantly influenced by Modern Hebrew.[7]

History

Prior to their adoption of the Arabic language from the seventh century onwards, most of the inhabitants of Palestine spoke varieties of Palestinian Aramaic (Jewish , Christian , Samaritan) as a native language . Koine Greek was used among the Hellenized elite and aristocracy , and Mishanic Hebrew for liturgical purposes .

The Negev desert was under the rule of the Nabatean Kingdom for the greater part of Classical antiquity , and included settlements such as Mahoza and Ein-Gedi where Judean and Nabatean populations lived in alongside each other , as documented by the Babatha archive which dates to the second century . The earliest Old Arabic inscription most resembling of Classical Arabic is found in Ayn Avadat , being a poem dedicated to King Obodas I , known for defeating the Hasmonean Alexander Jannaeus . Its date is estimated between 79 and 120 CE , but no later than 150 CE at most.[8]

The Nabataeans tended to adopt Aramaic as a written language as shown in the Nabataean language texts of Petra,[9] as well as a Lingua Franca . Nabatean and Palestinian Aramaic dialects would both have been thought of as “Aramaic” , and almost certainly have been mutually comprehensible. Additionally, occasional Arabic loanwords can be found in the Jewish Aramaic documents of the Dead Sea Scrolls.[9]

The adoption of Arabic among the local population occurred most probably in several waves. After the Early Muslim Arabians took control of the area, so as to maintain their regular activity, the upper classes had to quickly become fluent in the language of the new rulers who most probably were only few. The prevalence of Northern Levantine features in the urban dialects until the early 20th century, as well as in the dialect of Samaritans in Nablus (with systematic imala of /a:/) tends to show that a first layer of Arabization of urban upper classes could have led to what is now urban Levantine. Then, the main phenomenon could have been the slow countryside shift of Aramaic-speaking villages to Arabic under the influence of Arabized elites, leading to the emergence of the rural Palestinian dialects[citation needed]. This scenario is consistent with several facts.

- The rural forms can be correlated with features also observed in the few Syrian villages where use of Aramaic has been retained up to this day. Palatalisation of /k/ (but of /t/ too), pronunciation [kˤ] of /q/ for instance. Note that the first also exists in Najdi Arabic and Gulf Arabic, but is limited to palatal contexts (/k/ followed by i or a). Moreover, those Eastern dialects have [g] or [dʒ] for /q/ [citation needed].

- The less-evolutive urban forms can be explained by a limitation owed to the contacts urban trader classes had to maintain with Arabic speakers of other towns in Syria or Egypt.

- The Negev Bedouin dialect shares a number of features with Bedouin Hejazi dialects (unlike Urban Hejazi).

Differences compared to other Levantine Arabic dialects

The dialects spoken by the Arabs of the Levant – the Eastern shore of the Mediterranean – or Levantine Arabic, form a group of dialects of Arabic. Arabic manuals for the "Syrian dialect" were produced in the early 20th century,[10] and in 1909 a specific "Palestinean Arabic" manual was published.

The Palestinian Arabic dialects are varieties of Levantine Arabic because they display the following characteristic Levantine features:

- A conservative stress pattern, closer to Classical Arabic than anywhere else in the Arab world.

- The indicative imperfect with a b- prefix

- A very frequent Imāla of the feminine ending in front consonant context (names in -eh).

- A [ʔ] realisation of /q/ in the cities, and a [q] realisation of /q/ by the Druze[citation needed][dubious – discuss], and more variants (including [k]) in the countryside.

- A shared lexicon

The noticeable differences between southern and northern forms of Levantine Arabic, such as Syrian Arabic and Lebanese Arabic, are stronger in non-urban dialects. The main differences between Palestinian and northern Levantine Arabic are as follows:

- Phonetically, Palestinian dialects differ from Lebanese regarding the classical diphthongs /aj/ and /aw/, which have simplified to [eː] and [o:] in Palestinian dialects as in Western Syrian, while in Lebanese they have retained a diphthongal pronunciation: [eɪ] and [oʊ].

- Palestinian dialects differ from Western Syrian as far as short stressed /i/ and /u/ are concerned: in Palestinian they keep a more or less open [ɪ] and [ʊ] pronunciation, and are not neutralised to [ə] as in Syrian.

- The Lebanese and Syrian dialects are more prone to imāla of /a:/ than the Palestinian dialects are. For instance شتا 'winter' is ['ʃɪta] in Palestinian but ['ʃəte] in Lebanese and Western Syrian. Some Palestinian dialects ignore imala totally (e.g. Gaza). Those dialects that prominently demonstrate imāla of /a:/ (e.g. Nablus) are distinct among Palestinian dialects.

- In morphology, the plural personal pronouns are إحنا ['ɪħna] 'we', همه ['hʊmme] also hunne [هنه] 'they',[ كو] [ku] كم- [-kʊm] 'you', هم- [-hʊm] هني [henne]'them' in Palestinian, while they are in Syria/Lebanon نحنا ['nɪħna] 'we', هنه ['hʊnne] 'they', كن-[-kʊn] 'you', هن- [-hʊn] 'them'. The variants كو [-kʊ] 'you', ـهن [-hen] 'them', and هنه [hinne] 'they' are used in Northern Palestinian.

- The conjugation of the imperfect 1st and 3rd person masculine has different prefix vowels. Palestinians say بَكتب ['baktʊb] 'I write' بَشوف [baʃuːf] 'I see' where Lebanese and Syrians say بِكتب ['bəktʊb] and بْشوف [bʃuːf]. In the 3rd person masculine, Palestinians say بِكتب['bɪktʊb] 'He writes' where Lebanese and Western Syrians say بيَكتب ['bjəktʊb].

- Hamza-initial verbs commonly have an [o:] prefix sound in the imperfect in Palestinian. For example, Classical Arabic has اكل /akala/ 'to eat' in the perfect tense, and آكل /aːkulu/ with [a:] sound in the first person singular imperfect. The common equivalent in Palestinian Arabic is اكل /akal/ in the perfect, with imperfect 1st person singular بوكل /boːkel/ (with the indicative b- prefix.) Thus, in the Galilee and Northern West Bank, the colloquial for the verbal expression, "I am eating" or "I eat" is commonly ['bo:kel] / ['bo:tʃel], rather than ['ba:kʊl] used in the Western Syrian dialect. Note however that ['ba:kel] or even ['ba:kʊl] are used in the South of Palestine.

- The conjugation of the imperative is different too. 'Write!' is اكتب ['ʊktʊb] in Palestinian, but كتوب [ktoːb], with different stress and vowel and length, in Lebanese and Western Syrian.

- For the negation of verbs and prepositional pseudo-verbs, Palestinian, like Egyptian, typically suffixes ش [ʃ] on top of using the preverb negation /ma/, e.g. 'I don't write' is مابكتبش [ma bak'tʊbʃ] in Palestinian, but مابكتب [ma 'bəktʊb] in Northern Levantine (although some areas in southern Lebanon utilise the ش [ʃ] suffix). However, unlike Egyptian, Palestinian allows for ش [ʃ] without the preverb negation /ma/ in the present tense, e.g. بكتبش [bak'tubɪʃ].

- In vocabulary, Palestinian is closer to Lebanese than to Western Syrian, e.g. 'is not' is مش [məʃ] in both Lebanese and Palestinian (although in a few villages مهوش [mahuʃ] and مهيش [mahiʃ], which are found in Maltese and North African dialects, are used) while it is مو [mu] in Syrian; 'How?' is كيف [kiːf] in Lebanese and Palestinian while it is شلون [ʃloːn] in Syrian (though كيف is also used) . However, Palestinian also shares items with Egyptian Arabic, e.g. 'like' (prep.) is زي [zejj] in Palestinian in addition to مثل [mɪtl], as found in Syrian and Lebanese Arabic.

There are also typical Palestinian words that are shibboleths in the Levant.

- A frequent Palestinian إشي ['ɪʃi] 'thing, something', as opposed to شي [ʃi] in Lebanon and Syria.

- Besides common Levantine هلق ['hallaʔ] 'now', Central Rural dialects around Jerusalem and Ramallah use هالقيت [halke:t] (although [halʔe:t] is used in some cities such as Tulkarm, Hebron, and Nablus alongside هلق [hallaʔ] (both from هالوقت /halwaqt/ ) and northern Palestinians use إسا ['ɪssɑ], إساع ['ɪssɑʕ], and هسة [hassɑ](from الساعة/ɪs:ɑ:ʕɑ/). Peasants in the southern West Bank also use هالحين [halaħin] or هالحينة [halħina] (both from هذا الحين [haːða ‘alħin])

- Some rural Palestinians use بقى [baqa] (meaning 'remained' in MSA) as a verb to be alongside the standard كان [ka:n] ([ka:na in MSA)

Social and geographic dialect structuration

As is very common in Arabic-speaking countries, the Arabic dialect spoken by a person depends on both the region of origin , and socio-economic class. The hikaye, a form of women's oral literature inscribed to UNESCO's list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Palestine, is recited in both the urban and rural dialects of Palestinian Arabic.[11][12]

Palestinian urban dialects

The Urban ('madani') dialects resemble closely northern Levantine Arabic dialects, that is, the colloquial variants of western Syria and Lebanon.[13] This fact, that makes the urban dialects of the Levant remarkably homogeneous, is probably due to the trading network among cities in Ottoman Syria, or to an older Arabic dialect layer closer to the North Mesopotamian Arabic (the 'qeltu dialects").

Urban dialects are characterised by the [ʔ] (hamza) pronunciation of ق qaf, the simplification of interdentals as dentals plosives, i.e. ث as [t], ذ as [d] and both ض and ظ as [dˤ]. In borrowings from Modern Standard Arabic, these interdental consonants are realised as dental sibilants, i.e. ث as [s], ذ as [z] and ظ as [zˤ] but ض is kept as [dˤ]. The Druzes have a dialect that may be classified with the Urban ones,[dubious – discuss] with the difference that they keep the uvular pronunciation of ق qaf as [q]. The urban dialects also ignore the difference between masculine and feminine in the plural pronouns انتو ['ɪntu] is both 'you' (masc. plur.) and 'you' (fem. plur.), and ['hʊmme] is both 'they' (masc.) and 'they' (fem.)

Rural varieties

Rural or farmer ('fallahi') variety is retaining the interdental consonants, and is closely related with rural dialects in the outer southern Levant and in Lebanon. They keep the distinction between masculine and feminine plural pronouns, e.g. انتو ['ɪntu] is 'you' (masc.) while انتن ['ɪntɪn] is 'you' (fem.), and همه ['hʊmme] is 'they' (masc.) while هنه ['hɪnne] is 'they' (fem.). The three rural groups in the region are the following:

- North Galilean rural dialect – does not feature the k > tʃ palatalisation, and many of them have kept the [q] realisation of ق (e.g. Maghār, Tirat Carmel). In the very north, they announce dialect thats is more closely to the Northern Levantine dialects with n-ending pronouns such as كن-[-kʊn] 'you', هن- [-hʊn] 'them' (Tarshiha, etc.).

- Central rural Palestinian (From Nazareth to Bethlehem, including Jaffa countryside) exhibits a very distinctive feature with pronunciation of ك 'kaf' as [tʃ] 'tshaf' (e.g. كفية 'keffieh' as [tʃʊ'fijje]) and ق 'qaf' as pharyngealised /k/ i.e. [kˤ] 'kaf' (e.g. قمح 'wheat' as [kˤɑmᵊħ]). This k > tʃ sound change is not conditioned by the surrounding sounds in Central Palestinian. This combination is unique in the whole Arab world, but could be related to the 'qof' transition to 'kof' in the Aramaic dialect spoken in Ma'loula, north of Damascus.

- Southern outer rural Levantine Arabic (to the south of an Isdud/Ashdod-Bethlehem line) has k > tʃ only in presence of front vowels (ديك 'rooster' is [di:tʃ] in the singular but the plural ديوك 'roosters' is [dju:k] because u prevents /k/ from changing to [tʃ]). In this dialect ق is not pronounced as [k] but instead as [g]. This dialect is actually very similar to northern Jordanian (Ajloun, Irbid) and the dialects of Syrian Hauran. In Southern rural Palestinian, the feminine ending often remains [a].

Bedouin variety

The Bedouins of Southern Levant use two different ('badawi') dialects in Galilee and the Negev. The Negev desert Bedouins, who are also present in Palestine and Gaza Strip use a dialect closely related to those spoken in the Hijaz, and in the Sinai. Unlike them, the Bedouins of Galilee speak a dialect related to those of the Syrian Desert and Najd, which indicates their arrival to the region is relatively recent. The Palestinian resident Negev Bedouins, who are present around Hebron and Jerusalem have a specific vocabulary, they maintain the interdental consonants, they do not use the ش- [-ʃ] negative suffix, they always realise ك /k/ as [k] and ق /q/ as [g], and distinguish plural masculine from plural feminine pronouns, but with different forms as the rural speakers.

Sephardic variety

As Sephardic Jews were expelled after the conclusion of the Reconquista , they established communities in Ottoman Palestine in Jerusalem and Galilee under the invitation of Sultan Bayezid II . Their Maghrebi Judeo-Arabic dialect mixed with Palestinian Arabic. It peaked at 10,000 speakers and thrived alongside Yiddish among Ashkenazis until the 20th century in Mandatory Palestine.

Today it is nearly extinct , with only 5 speakers remaining in the Galilee.[14] It contained influence from Judeo-Moroccan Arabic and influence Judeo-Lebanese Arabic and Judeo-Syrian Arabic.[15]

Current evolutions

On the urban dialects side, the current trend is to have urban dialects getting closer to their rural neighbours, thus introducing some variability among cities in the Levant. For instance, Jerusalem used to say as Damascus ['nɪħna] ("we") and ['hʊnne] ("they") at the beginning of the 20th century, and this has moved to the more rural ['ɪħna] and ['hʊmme] nowadays.[16] This trend was probably initiated by the partition of the Levant of several states in the course of the 20th century.

The Rural description given above is moving nowadays with two opposite trends. On the one hand, urbanisation gives a strong influence power to urban dialects. As a result, villagers may adopt them at least in part, and Beduin maintain a two-dialect practice. On the other hand, the individualisation that comes with urbanisation make people feel more free to choose the way they speak than before, and in the same way as some will use typical Egyptian or Lebanese features as [le:] for [le:ʃ], others may use typical rural features such as the rural realisation [kˤ] of ق as a pride reaction against the stigmatisation of this pronunciation.

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Interdental | Dental/Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | emph. | plain | emph. | plain | emph. | plain | emph. | ||||||

| Nasal | m | mˤ | n | ||||||||||

| Stop | voiceless | t | tˤ | (t͡ʃ) | k | kˤ | ʔ | ||||||

| voiced | b | bˤ | d | dˤ | d͡ʒ | ɡ | (ɢ) | ||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | θ | s | sˤ | ʃ | χ | ħ | h | ||||

| voiced | ð | ðˤ | z | zˤ | ʒ | ʁ | ʕ | ||||||

| Trill | (r) | rˤ | |||||||||||

| Approximant | l | lˤ | j | w | |||||||||

- Sounds /θ, ð, ðˤ, t͡ʃ, d͡ʒ/ are mainly heard in both the rural and Bedouin dialects. Sounds /zˤ/ and /ʒ/ are mainly heard in the urban dialects. /kˤ/ is heard in the rural dialects.

- /ɡ/ is heard in the Bedouin dialects, and may also be heard as a uvular [ɢ].

- [t͡ʃ] mainly occurs as a palatalization of /k/, and is only heard in a few words as phonemic. In some rural dialects [t͡ʃ] has replaced /k/ as a phoneme.

- /rˤ/ may de-pharyngealize as [r] in certain phonetic environments.

- /ʁ/ can also be heard as velar [ɣ] among some rural dialects.

- /b/ can be heard as [p] within devoiced positions.

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː | u uː | |

| Mid | e eː | o oː | |

| Open | a aː |