DoubleBlue (talk | contribs) →The crisis: date of army arrival |

DoubleBlue (talk | contribs) →The crisis: troops in area |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

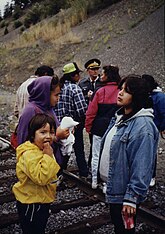

[[Image:Oka lasagna stare down.jpg|thumb|300px|right|Mohawk warrior "Lasagna" and a Canadian soldier stare down while surrounded by media]] |

[[Image:Oka lasagna stare down.jpg|thumb|300px|right|Mohawk warrior "Lasagna" and a Canadian soldier stare down while surrounded by media]] |

||

When it was apparent that the Sûreté du Québec had lost control of the situation, the [[RCMP]] was brought in, but they were soon overwhelmed by the mobs, and ten constables were hospitalized. [[Premier of Quebec|Quebec premier]] [[Robert Bourassa]] requisitioned the assistance of the [[Canadian Forces]] in [[Military Aid to the Civil Power |"aid of the civil power"]] under the National Defence Act. [[Prime Minister of Canada|Canadian prime minister Brian Mulroney]] was reluctant, but Bourassa insisted, as he had in the [[October Crisis]] in 1970, and the army be sent in. |

When it was apparent that the Sûreté du Québec had lost control of the situation, the [[RCMP]] was brought in, but they were soon overwhelmed by the mobs, and ten constables were hospitalized. [[Premier of Quebec|Quebec premier]] [[Robert Bourassa]] requisitioned the assistance of the [[Canadian Forces]] in [[Military Aid to the Civil Power |"aid of the civil power"]] under the National Defence Act. [[Prime Minister of Canada|Canadian prime minister Brian Mulroney]] was reluctant, but Bourassa insisted, as he had in the [[October Crisis]] in 1970, and the army be sent in. Some 2500 troops moved in around Kanesatake and, on the morning of [[20 August]], 33 troops arrived at the barricades. The Sûreté du Québec had established as [[no man's land]] of one and a half kilometres between themselves and the barricade at the Pines, but the army pushed this to within five metres. |

||

==Resolution== |

==Resolution== |

||

Revision as of 18:51, 23 July 2005

Template:Current Canadian COTW

The Oka Crisis was a land dispute between the Mohawk nation and the town of Oka, Quebec which began on March 11 1990, and lasted until September 26 1990. It resulted in massive traffic jams and three deaths.

Historical dispute

The crisis developed from a dispute between the town of Oka and the Mohawk reserve of Kanesatake. For 260 years, the Mohawk nation had been pursuing a land claim which included a burial ground and a sacred grove of pine trees near Kanesatake, which is one of the oldest hand-planted stands in North America, created by the Mohawks' ancestors. This brought them into conflict with the the town of Oka, which was developing plans to expand a golf course onto the disputed land.

In 1717, the governor of New France granted the lands encompassing the cemetery and the pines to a Catholic seminary to hold the land in trust for the Mohawk nation. The Church expanded this agreement to grant themselves sole ownership of the land, and proceeded to sell off the Mohawks' land and timber. In 1868, one year after Confederation, the chief of the Oka Mohawks, Joseph Onasakenrat, wrote a letter to the Church condemning them for illegally holding their land and demanding its return. The petition was ignored. In 1869, Onasakenrat returned with a small armed force of Mohawks and gave the missionaries eight days to return the land. The missionaries called in the police, who imprisoned the Mohawks. In 1936, the seminary sold the remaining territory and vacated the area. These sales were also protested vociferously by the Mohawks, but all were ignored.[1]

In 1961, a nine-hole golf course, le Club de golf d'Oka, was built on land claimed by the Mohawks, who launched a legal protest against construction. Yet, by the time the case was heard, much of the land had already been cleared and construction had begun on a parking lot and golf greens adjacent to the Mohawk cemetery.

In 1977, the band filed an official land claim with the federal Office of Native Claims regarding the land. The claim was accepted for filing, and funds were provided for additional research of the claim. Nine years later, the claim was finally rejected for failing to meet certain criteria. [2]

Immediate causes

The mayor of Oka, Jean Ouellette, announced in 1989 that the remainder of the pines would be cleared to expand the members-only golf club's course to eighteen holes. Sixty luxury condominiums were also planned to be built in a section of the pines. The town of Oka stood to make millions of dollars from the expansion, and Mayor Ouellette was a member of the private club that stood to benefit most. However, none of these plans were made in consultation with the Mohawks. Later, when asked to explain this move as the Oka Crisis raged, Mayor Ouellette replied: "You know you can't talk to the Indians".

As a protest against a court decision which allowed the golf course construction to proceed, some members of the Mohawk community erected a barricade blocking access to the area in question. Mayor Ouellette demanded compliance with the court order, but the protestors refused. Quebec's Minister for Native Affairs John Ciaccia pleaded with the mayor to show restraint and recognize that "these people have seen their lands disappear without having been consulted or compensated, and that, in my opinion, is unfair and unjust, especially over a golf course."

The crisis

Instead, the mayor asked the Sûreté du Québec to intervene on July 11. The Mohawk warriors, in accordance with the ancient Constitution of the Iroquois Confederacy, asked the women, the caretakers of the land and "progenitors of the nation", whether or not the arsenal they had amassed should remain. The women decreed that the weapons should be used only if the Sûreté du Québec opened fire first. The police demanded through a bullhorn that the Mohawks send out their leader, and a group of a dozen unarmed Mohawk women stepped out from the barricades. The police fired tear gas, injuring several of the women, and concussion grenades; women and children fled in panic, and then the police opened fire in an effort to disperse the Mohawks manning the barricade. Shots were fired in return by Mohawk warriors. After thirty seconds of the firefight, the police broke rank and ran, abandoning six vehicles and many weapons, ammunition, and communication devices. During the gun battle, Corporal Marcel Lemay of the Sûreté du Québec was shot between the sections of his protective vest and died a short while later, leaving behind a two-year-old daughter and his pregnant wife. After the funeral a few days later, the SQ and the Mohawks lowered their flags to half-mast, and the Mohawks sent condolences. However, the Mohawks refused to accept blame, pointing out that it was Mayor Ouellette that ordered the full-scale armed assault on the area.

The situation escalated as the local natives were joined by indigenous Warriors from across Canada and the United States. The Mohawks refused to dismantle their barricade and the Sûreté du Québec established their own blockades to restrict access to Oka and Kanesatake. Other Mohawks at Kahnawake, in solidarity with the Kanesatake Mohawks, blockaded the Mercier Bridge between the Island of Montreal and the South Shore suburbs at the point where it passed through their territory. At the peak of the crisis, the Mercier Bridge and highways 132, 138 and 207 were all blocked. Enormous traffic jams and frayed tempers resulted as the crisis dragged on.

The Canadian federal government agreed to spend 5.3 million dollars to purchase the section of the pines where the expansion was to take place, to prevent any further development. Mayor Ouellette also sold the Mohawk cemetery for an additional dollar. This exchange left the Mohawks outraged, as the problems had not been addressed, but rather ownership had simply moved from one level of government to another.

Racial hatred was also an active force in the crisis. Initially, mobs of angry Quebecois commuters gathered at the barricades to protest the blockade of the Mercier Bridge. However, the situation quickly devolved into scenes of racial violence. In one particular incident, Francophone thugs attacked a Mohawk woman shopping in a grocery store in near-by Chateauguay, hurling stones and racial insults as they chased her back to the reserve. Within a few days of the barricades being erected, effigies of natives were being strung up and burned as the cry of "Quebec pour les Quebecois" rang out. The flames were fanned by a Francophone chapter of the Ku Klux Klan [3], and by radio host Gilles Proulx who repeatedly reminded his listeners that the Mohawks "couldn't even speak French". The federal member of Parliament for Chateauguay said that all the natives in Quebec should be shipped off to Labrador "if they wanted their own country so much". An ambulance carrying a pregnant Mohawk woman from a reservation was even blockaded by a Quebecois mob.

When it was apparent that the Sûreté du Québec had lost control of the situation, the RCMP was brought in, but they were soon overwhelmed by the mobs, and ten constables were hospitalized. Quebec premier Robert Bourassa requisitioned the assistance of the Canadian Forces in "aid of the civil power" under the National Defence Act. Canadian prime minister Brian Mulroney was reluctant, but Bourassa insisted, as he had in the October Crisis in 1970, and the army be sent in. Some 2500 troops moved in around Kanesatake and, on the morning of 20 August, 33 troops arrived at the barricades. The Sûreté du Québec had established as no man's land of one and a half kilometres between themselves and the barricade at the Pines, but the army pushed this to within five metres.

Resolution

On August 29, at the Mercier Bridge blockade, the Mohawks negotiated an end to their protest with the army, and the siege of the Kahnawake reserve was over. The Mohawks at Oka felt betrayed at the loss of their most effective bargaining chip, for once traffic was flowing again, the Quebec government rejected all further negotiations.

On September 25, the final engagement of the crisis took place when a Mohawk warrior walked around the perimeter with a long stick, setting off the flares the army had set up to warn them of any escapes from the area. The army turned a hose on the man, but the hose lacked enough pressure to disperse a crowd. The Mohawks taunted the soldiers and then started throwing water balloons at them. This set off a full-scale water fight, with much laughter and fun, until an enraged officer ordered his men to cease the water fight. The Mohawks taunted the officer and threw water balloons at him.

On September 26 the Mohawks had had enough. They burned incriminating evidence, dismantled their guns and threw them in a septic tank, ceremonially burned tobacco and then walked out of the pines and back to the reservation as the army struggled to capture them.

The Oka Crisis lasted seventy-eight days and cost the life of SQ Corporal Marcel Lemay. Two other deaths have also been indirectly attributed to the crisis: Joe Armstrong, a seventy-one-year-old World War II veteran who had died of a stress-induced heart attack after a confrontation with an angry Quebecois crowd; and an elderly Quebecois man who died after being exposed to tear gas on July 11. No-one was ever charged for any of these deaths.

The golf-course expansion, which had originally triggered the situation, was cancelled. The Oka Crisis eventually precipitated the development of Canada's First Nations Policing Policy.

Repercussions

International response to the Oka Crisis was harsh. Sympathy for Quebec nationalism took a plunge and has never recovered. The International Federation of Human Rights has criticized the tactics of both the SQ and the Canadian Army. Amnesty International raised allegations of torture and abuses following the final arrest of six of the Mohawk warriors, and added Canada to its list of human rights violators.

Mayor of Oka, Jean Ouellette was reelected in a landslide victory in 1991 and said of the crisis: "If I had to do it all again, I would."

Canadian filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin has made several documentaries about the Oka Crisis, including Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993) and Rocks at Whiskey Trench (2000). Another documentary by Alex MacLeod, called Acts of Defiance, also came out in 1993. All of these documentaries were produced by Canada's National Film Board.

Micheal Baxendale and Craig MacLaine have written a book on the crisis, This Land Is Our Land: The Mohawk Revolt at Oka. Geoffrey York and Loreen Pindera's People of the Pines: The Warriors and the Legacy of Oka (1991) is considered the definitive text on the subject. Gerald R. Alfred, a Kahnawake Mohawk who was part of the band council during the crisis, and who later went on to become a professor of Political Science, wrote Heeding the Voices of our Ancestors: Kahnawake Mohawk Politics and the Rise of Native Nationalism (1995), based on his dissertation.

See also

Bibliography

- Alanis Obomsawin (1993). Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance. National Film Board of Canada. IMDb

- Alanis Obomsawin (2000). Rocks at Whiskey Trench. National Film Board of Canada. IMDb

- Alec G. MacLeod (1992). Acts of Defiance. National Film Board of Canada. IMDb

- . ISBN 0888902298.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Title=ignored (|title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Year=ignored (|year=suggested) (help) - . ISBN 0316969168.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Title=ignored (|title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Year=ignored (|year=suggested) (help) - . ISBN 0195411382.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Title=ignored (|title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Year=ignored (|year=suggested) (help)