- Another mission bearing the name San Juan Capistrano is the Mission San Juan Capistrano in San Antonio, Texas.

| Mission San Juan Capistrano A view of Mission San Juan Capistrano in April of 2005. At left is the façade of the first adobe church with its added espadaña. Behind the campanario, or "bell wall" is the "Sacred Garden." The Mission has earned a reputation as the "Loveliest of the Franciscan Ruins." | |

| Location | San Juan Capistrano, California |

|---|---|

| Name as founded | La Misión de San Juan Capistrano de Sajavit [1] |

| English translation | The Mission of Saint John of Sajavit |

| Patron | Saint John of Capestrano, Italy |

| Nickname(s) | "The Jewel of the Missions" [2] "The Mission of the Swallow" |

| Founding date | November 1, 1776 |

| Founding priest(s) | Father Presidente Junípero Serra |

| Founding Order | Seventh |

| Military district | First |

| Native tribe(s) Spanish name(s) | Juaneño |

| Governing body | Roman Catholic Church |

| Current use | Chapel / Museum |

Mission San Juan Capistrano was founded on All Saints Day (November 1), 1776. Named for a 15th-century theologian and "warrior priest" who resided in the Abruzzo region of Italy, San Juan Capistrano has the distinction of being home to the oldest building in California still in use, a chapel built in 1782 known as alternately as "Serra's Chapel" and "Father Serra's Church" (the only remaining building wherein it has been documented that the padre officiated over mass).[3] The founding document on display within the Mission is also the only known surviving founding paper signed by Father Serra. One of the best known of the Alta California missions, the site was originally consecrated on October 30, 1775 by Father Fermín Lasuén but was abandoned due to unrest among the indigenous population in San Diego.

The success of the settlement is evident in its historical records. Prior to the arrival of the missionaries, some 550 natives were scattered throughout the local area; by 1790, the number of converted Christians had grown to 700, and just six years later nearly 1,000 "neophytes" (recent converts) lived in or around the Mission compound. 1,649 baptisms were conducted that year alone, out of the total 4,430 souls converted throughout the Mission's lifetime. An estimated 2,000 former inhabitants (mostly Native Americans) are buried in unmarked graves in the Mission's cemetery (campo santo), as are the remains of Father St. John O'Sullivan, the man credited with recognizing the property's historic value and working tirelessly to conserve and rebuild its structures. Father O'Sullivan is buried at the entrance to the cemetery on the west side of the property, and a statue raised in his honor stands at the head of the crypt. The surviving chapel also serves as the final resting place of three padres who passed on while serving at the Mission: Father José Barona, Father Vincent Fuster, and Father José Rafael Oliva are all entombed beneath the sanctuary floor.

The Mission entered a long period of gradual decline after secularization in 1834. Numerous efforts were made over the years to restore the Mission to its former glory, but none met with great success until the arrival of Father O'Sullivan in 1910. Restoration efforts continue to this day; "Serra's Chapel" is still used for religious services, and over half a million people visit the landmark every year. In 1984 a modern church complex was constructed just north and west of the Mission compound; the design is patterned after the old stone church, but twenty percent larger. Its 85-foot high main rotunda and 104-foot high bell tower make it the tallest building in town. Pope John Paul II conferred the rank of Minor Basilica to this facility on February 14, 2000.

Prehistory

The first humans are thought to have made their homes among the southern valleys of California's coastal mountain ranges some 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. The earliest of these people are known only from archaeological evidence. Relatively much is known about the native inhabitants in recent centuries, thanks in part to the efforts of the Spanish explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo, who documented his observations of life in the coastal villages he encountered along the Southern California coast in October of 1542.[5] Fray Gerónimo Boscana, a Franciscan scholar who was stationed at San Juan Capistrano in 1812, compiled what is widely considered to be the most comprehensive study of prehistoric religious practices in the San Juan Capistrano valley. Religious knowledge was secret, and the prevalent religion, called Chingichngich, placed village chiefs in the position of religious leaders, an arrangement that gave the chiefs broad power over their people.

History

The Mission Era (1769 – 1833)

Father Juan Crespí authored the first written account of actual interaction between Franciscan friars and the indigenous population after his expedition traveled through the region on July 22, 1769. The group officially named the area after Santa Maria Magdalena (though it would also come to be called the Arroyo de la Quema and Cañada del Incendio, "Wildfire Hollow").[6] The Mission site was chosen as a logical halfway point between San Gabriel and San Diego. San Juan Capistrano is one of the few missions to have actually been founded twice (another being Mission La Purísima Concepción); the site was first established Father Fermín Lasuén and Father Gregório Amúrrio on October 30, 1775 near an Indian settlement named Sajivit; unfortunately, Mission San Diego de Alcalá came under Indian attack eight days later.[7] Since it was feared at the time that any hostile action by the natives against the few burgeoning outposts might break Spain's tenuous hold on Alta California, the fathers quickly buried the San Juan Capistrano Mission bells and the expedition returned to El Presidio de San Diego in order to quell the uprising.

One year later Fathers Serra and Lasuén returned to once again begin work on the Mission at San Juan Capistrano; once there, they uncovered the bells and discovered that a wooden cross that had been erected during the original dedication was still standing. Due to an inadequate water supply the Mission site was subsequently relocated approximately three miles to the west near the Indian village of Acágcheme.[8] According to a report filed in 1782 by Father Pablo Mugártegui, "...the site was transferred to that which it occupies today, where we have the advantage of secure water...this transfer was made on October 4, 1778." [9] The new venue was strategically placed above two nearby streams, the Trabuco and the San Juan. Mission San Gabriel Arcángel provided cattle and neophyte labor to assist in the development of new the Mission.

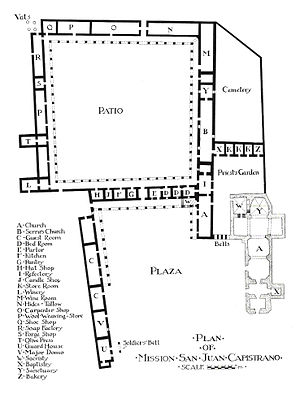

In 1778, the first adobe capilla (chapel) was blessed. It was replaced by a larger, 115-foot long house of worship in 1782, which is believed to be the oldest standing building in California. Known proudly as the "Serra Chapel," it has the distinction of being the only remaining church in which the padre is known to have officiated (Mission Dolores was still under construction at the time of Serra's visit there). Father Serra presided over the confirmations of 213 people on October 12 and 13, 1783; divine services are held there to this day. The centerpiece of the chapel is its spectacular retablo which serves as the backdrop for the altar. A masterpiece of Baroque art, the altarpiece was hand-carved of 196 individual pieces of cherry wood and overlaid in gold leaf in Barcelona and is estimated to be 400 years old. It was originally imported from Barcelona in 1806 and later donated by Archbishop John Cantwell of Los Angeles (the building had to be enlarged to accommodate this piece). Although the retablo had been relayered over the centuries, most of the original gilding remains underneath the modern materials; extensive restoration was begun in June, 2006. By the time of the chapel's completion, living quarters, kitchens (pozolera), workshops, storerooms, soldiers' barracks (cuartels), and a number of other ancillary buildings had also been erected, effectively forming the main cuadrángulo (quadrangle).

California's first vineyard was located on the Mission grounds, with the planting of the "Mission" or "Criollo" grape in 1779, one grown extensively throughout Spanish America at the time but with "an uncertain European origin." It was the only grape grown in the Mission system throughout the mid-1800s. The first winery in Alta California was built in San Juan Capistrano in 1783; both red and white wines (sweet and dry), and brandy were all produced from the Mission grape. In 1791, the Mission's two original bells were removed from the tree branch on which they had been hanging for the previous fifteen years and placed within a permanent mounting. Over the next two decades the Mission prospered, and in 1794 over seventy adobe structures were built in order to provide permanent housing for the Mission Indians, some of which comprise the oldest residential neighborhood in California. It was decided that a larger, European-style church was required to accommodate the growing population. Hoping to construct an edifice of truly magnificent proportions, the padres retained the services of expert Mexican stonemason Isidoro Aguílar.[11] Aguílar took charge of the church's construction and set about incorporating numerous design features not found at any other California Mission, including the use of a domed roof structure made of stone as opposed to the typical flat wood roof. His elegant roof design called for six vaulted domes (bovedas) to be built.

Work was begun on "The Great Stone Church" on February 2, 1797. It was laid out in the shape of a cross, measuring 180 feet long by 40 feet wide with 50-foot high walls, and included a 120-foot tall campanile ("bell tower") located adjacent to the main entrance that could be seen for miles around. The building sat on a foundation seven feet thick. Construction efforts required the participation of the entire neophyte population. Stones were quarried from gullies and creek beds up to six miles away and transported in carts (carretas) drawn by oxen, carried by hand, and even dragged to the building site. Limestone was crushed into a powder on the Mission grounds to create a mortar that was more erosion-resistant than the actual stones.

Unfortunately, Señor Aguílar died six years into the project. His work was carried on by the padres and their charges, who made their best attempts to emulate the existing construction. Lacking the skills of a master mason, however, led to irregular walls and necessitated the addition of a seventh roof dome. The church was finally completed in 1806, and blessed by Fray Estévan Tapís on the evening of September 7[12]. The sanctuary floors were paved with diamond-shaped tiles, and brick-lined niches displayed the statues of various saints. It was by all accounts the most magnificent in all of California and a three-day feast was held in celebration of this monumental achievement. Tragedy struck the settlement when on December 8, 1812 (the "Feast Day of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin") a series of massive earthquakes shook Southern California during the first Sunday service. Twelve years earlier a minor earth tremor had hit, causing only superficial damage to the work in progress.[13]

The 1812 Wrightwood Earthquake racked the doors to the church, pinning them shut. When the ground finally stopped shaking, the bulk of the nave had come crashing down, and the bell tower was completely obliterated. Forty-two worshippers from the local Acjachemem Nation (referred to as Juaneños by the Spaniards) who were attending mass were buried under the rubble and lost their lives, and were subsequently interred in the Mission cemetery. This was the second major setback the outpost had suffered, and followed severe storms and flooding that damaged Mission buildings and ruined crops earlier in the year. The padres immediately returned to holding services in Serra's Church. Within a year a brick campanario ("bell wall") had been erected between the ruins of the stone church and the Mission's first chapel to support the four bells salvaged from the rubble of the campanile. As the transept, sanctuary (reredos), and sacristia (sacristy) were all left standing, an attempt was made to rebuild the stone church in 1815 which failed due to a lack of construction expertise (the latter is the only element that is completely intact today). Consequently, all of the construction work undertaken at the Mission grounds thereafter was of a strictly utilitarian nature. Father José Barona and Father Gerónimo Boscana oversaw the construction of a small infirmary (hospital) building (located just outside the northwestern corner of the quadrangle) in 1814, "for the convenience of the sick." It is here that Juaneño medicine men used traditional methods to heal the sick and injured. Archaeological excavations in 1937 and 1979 unearthed what are believed to be the building's foundations.

On December 14, 1818 the French privateer Hipólito Bouchard, sailing under an Argentine flag, brought his ships La Argentina and Santa Rosa to within sight of the Mission and sent forth an envoy with a demand for provisions. The garrison soldiers were aware that Bouchard (today known as "California's only pirate") had recently conducted raids on the settlements at Monterey and Santa Barbara, so the demand was rebuffed and threats of reprisals made.[14] In response, Pirate Buchar ordered an assault on the Mission, sending some 140 men and a trio of cannon to take the needed supplies by force.[15] The Mission guards engaged the attackers but were overwhelmed, and the privateers left several damaged buildings in their wake, including the Governor's house, the King's stores, and the barracks. A celebration is held annually to memorialize the event.

Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821. The 1820s and 30s saw a gradual decline in the Mission's status. Disease thinned out the once ample cattle herds, and a sudden infestation of mustard weed made it increasingly difficult to cultivate crops. Floods and droughts took their toll as well. But the biggest threat to the Mission's stability came from the presence of Spanish settlers who sought to take over Capistrano's fertile lands. Over time the disillusioned Indian population gradually left the Mission, and without regular maintenance its physical deterioration continued at an accelerated rate.

Nevertheless, there was sufficient activity along El Camino Real to justify the construction of the Las Flores Asistencia in 1823. This facility, situated halfway between San Juan Capistrano and the Mission at San Luís Rey, was intended to act primarily as a rest stop for traveling clergy. During the same period the Diego Sepúlveda Adobe was established as an estancia (way-station) for the vaqueros (cowboys) who tended the Mission herds, in what today is the City of Costa Mesa. Following secularization, ownership passed to Don Diego Sepúlveda.

Although Governor José Figueroa (who took office in 1833) initially attempted to keep the mission system intact, the Mexican Congress nevertheless passed An Act for the Secularization of the Missions of California on August 17, 1833. Mission San Juan Capistrano was the very first to feel the effects of this legislation the following year.

The Rancho Era (1834 – 1849)

The Mexican Congress passed An Act for the Secularization of the Missions of California on August 17, 1833. The Act also provided for the colonization of both Alta and Baja California, the expenses of this latter move to be borne by the proceeds gained from the sale of the mission property to private interests. Mission San Juan Capistrano was the very first to feel the effects of this legislation the following year. The Franciscans abandoned the Mission, taking with them most everything of value, after which the locals plundered the Mission buildings for construction materials. By 1835, little of the Mission's assets remained, though the manufacture of hides and tallow continued as described in Richard Henry Dana's classic novel Two Years Before the Mast.[16]

San Juan Capistrano was officially designated as a secular Mexican pueblo in 1841, at which time those few who still resided at the Mission were granted sections of land to use as their own. Four years later the Mission property was auctioned off under questionable circumstances for $710 worth of tallow and hides to Englishman John "Don Juan" Forster (Governor Pío Pico's brother-in-law, whose family would take up residence in the Friars' quarters for the next twenty years) and his partner James McKinley. More families would subsequently take up residence in other portions of the Mission buildings.

California Statehood (1850 – 1900)

In 1860 an abortive attempt at restoring the stone church was the cause of its additional disintegration, forcing the dome over the transept and its cupola (lantern house) to collapse. A smallpox epidemic swept through the area in 1862, nearly wiping out the remaining Juaneño Indians. President Abraham Lincoln signed a proclamation on March 18, 1865 that returned ownership of the Mission proper to the Catholic Church. The document remains on display in the Mission's barracks cum museum; it is one of the few documents he ever signed as "Abraham Lincoln" instead of his customary "A. Lincoln." The Mission's sole resident from 1866 to 1886 was its pastor, Father José Mut. Father Mut made certain changes in order to accommodate his own needs, but little was accomplished to prevent further deterioration of the Mission buildings. By 1891 a roof collapse required that the Serra Chapel be abandoned completely. Modifications were made to the original adobe church (including the addition of a cross-topped espadaña at the south end, a feature that has been retained in the present iteration of the Mission compound) in order to render it suitable for use as a parish church.

In 1894, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway constructed a new depot in the emerging "Mission Revival Style" mere blocks from the Mission. It is rumored that the stonework, bricks, and roof tiles were salvaged from the decaying buildings.[18] The following year, a group calling itself the Landmarks Club of Los Angeles made the first real efforts at preserving the Mission and restoring it to its original state in over fifty years. Over 400 tons of debris was cleared away, holes in the walls were patched, and new shake cedar roofs were placed over a few of the derelict buildings. A mile of walkways were repaved with asphalt and gravel as well.

The 20th Century and beyond (1901 – present)

After Father Mut's departure in 1886 the parish found itself without a permanent pastor, and the Mission languished during this period. Father St. John O'Sullivan arrived in San Juan Capistrano in 1910 to recuperate from a recent stroke.[19] He became fascinated by the scope of the Mission and soon set to work on rebuilding it a section at a time. Father O'Sullivan's first task was to repair the roof of the Serra Chapel (which was being employed as a granary and storeroom) using sycamore logs to match those that were used in the original work; in the process, the roof of the apse was raised to allow for the inclusion of a window so that natural light could be brought into the space. Other refurbishments were made as time and funds permitted. Arthur B. Benton, a Los Angeles architect, strengthened the chapel walls through the addition of heavy masonry buttresses.

It is rumored that silent film star Mary Pickford's secret marriage to fellow actor Owen Moore in 1911 took place in the Mission chapel. Severe flooding destroyed a portion of the Mission's front arcade in 1915, and heavy storms a year later washed away one end of the barracks building, which Father O'Sullivan rebuilt in 1917, incorporating minor modifications such as an ornamental archway in order to make the edifice more closely resemble a church. On April 21, 1918 the San Jacinto Earthquake resulted in moderate structural damage to some of the buildings. In 1919, author Johnston McCulley created the character "Zorro" and chose Mission San Juan Capistrano as the setting for the first novella, titled The Curse of Capistrano.[20]

In 1920, the "Sacred Garden" was created in the courtyard adjacent to the stone church, and in 1925 the full restoration of the Serra Chapel was completed. Father O'Sullivan died in 1933 and was buried in the Mission cemetery. His tomb lies at the foot of a Celtic cross the Father himself erected as a memorial to the Mission's builders. In 1937 representatives of the U.S. National Park Service's Historic American Buildings Survey, as a part of the Historic Sites Act of 1935, surveyed and photographed the grounds and structures extensively. Their efforts laid the groundwork for future excavation and reconstruction of the west wing industrial complex.

The prestigious World Monuments Fund placed "The Great Stone Church" on its List of 100 Most Endangered Sites in 2002. The most recent series of seismic retrofits at the Mission were completed in 2004.

Mission industries

The Missions were, above all, required to become self-sufficient in relatively short order. Farming, therefore, was the most important industry of any mission. Barley, maize, and wheat were the principal crops grown at San Juan Capistrano; cattle, horses, mules, sheep, and goats were all raised by the hundreds as well. In 1790 the Mission's herd included 7,000 sheep and goats, 2,500 cattle, and 200 mules and horses. Olives were grown, cured, and pressed under large stone wheels to extract their oil, both for use at the Mission and to trade for other goods. Grapes were also grown and fermented into wine for sacramental use and again, for trading. The specific variety, called the Criolla or "Mission grape," was first planted at the Mission in 1779; in 1783, the first wine produced in Alta California emerged from San Juan Capistrano's winery. Cereal grains were dried and ground by stone into flour. The Mission's kitchens and bakeries prepared and served thousands of meals each day. Candles, soap, grease, and ointments were all made from tallow (rendered animal fat) in large vats located just outside the west wing. Also situated in this general area were vats for dyeing wool and tanning leather, and primitive looms for weavings. Large bodegas (warehouses) provided long-term storage for preserved foodstuffs and other treated materials.

Three long zanjas (aqueducts) ran through the central courtyard and deposited the water they collected into large cisterns in the industrial area, where it was filtered for drinking and cooking, or dispensed for use in cleaning. The Mission had to fabricate all of its construction materials as well. Workers in the carpintería (carpentry shop) used crude methods to shape beams, lintels, and other structural elements; more skilled artisans carved doors, furniture, and wooden implements. For certain applications bricks (ladrillos) were fired in ovens (kilns) to strengthen them and make them more resistant to the elements; when tejas (roof tiles) eventually replaced the conventional jacal roofing (densely-packed reeds) they were placed in the kilns to harden them as well. Glazed ceramic pots, dishes, and canisters were also made in the Mission's kilns.

Prior to the arrival of the missions, the native peoples knew only how to utilize bone, seashells, stone, and wood for building, tool making, weapons, and so forth. The foundry at Mission San Juan Capistrano was the first to introduce the Indians to the Iron Age. The blacksmith used the Mission’s Catalan furnaces (California’s first) to smelt and fashion iron into everything from basic tools and hardware (such as nails) to crosses, gates, hinges, even cannon for Mission defense. Iron was one commodity in particular that the Mission relied solely on trade to acquire, as the missionaries had neither the know-how nor the technology to mine and process metal ores.

The Mission bells

Bells were vitally important to daily life at any mission. The bells were rung at mealtimes, to call the Mission residents to work and to religious services, during births and funerals, to signal the approach of a ship or returning missionary, and at other times. All four of Mission San Juan Capistrano's bells are named and all bear inscriptions as follows (from the largest to the smallest; inscriptions are translated from Latin):

- "Praised by Jesus, San Vicente. In honor of the Reverend Fathers, Ministers (of the Mission) Fray Vicente Fuster, and Fray Juan Santiago, 1796."

- "Hail Mary most pure. Ruelas made me, and my name is San Juan, 1796."

- "Hail Mary most pure, San Antonio, 1804."

- "Hail Mary most pure, San Rafael, 1804."

In the aftermath of the 1812 earthquake, the two largest bells cracked and split open. Due to this damage neither produced clear tones. Regardless, they were hung in the campanario that went up the following year.

On March 22, 1969 President Richard M. Nixon and First Lady Patricia Nixon visited the Mission and rang the Bell of San Rafael. A bronze plaque commemorating the event is set in the bell wall. In celebration of the new Mission church being elevated to Minor Basilica status in 2000, exact duplicates of the damaged bells were cast in the Netherlands, utilizing molds made from the originals. The replacement bells were placed in the bell wall and the old ones put on display within the footprint of the destroyed Mission campanile ("bell tower").

"The return of the swallows"

The Cliff Swallow (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota) is a migratory bird that spends its winters in Goya, Argentina but makes the 6,000-mile trek north to the warmer climes of the American Southwest in springtime. According to legend the birds, who have visited the San Juan Capistrano area every Summer for centuries, first took refuge at the Mission when an irate innkeeper began destroying their mud nests. The Mission's location near two rivers made it an ideal location for the swallows to nest, as there was a constant supply of the insects on which they feed, and the young birds are well-protected inside the ruins of the old stone church.

Father O'Sullivan made note of the birds' annual habit of nesting beneath the Mission's eaves and archways, from Spring through Fall, during his two decades in residence. On March 13, 1939 a popular radio program was broadcast live from the Mission grounds, announcing the swallows' return. Composer Leon René was so inspired by the event that he penned the song When the Swallows Come Back to Capistrano in tribute.[21] During its initial release the song spent several weeks atop the Your Hit Parade charts. The song has been recorded by such musicians as The Ink Spots, Fred Waring, Guy Lombardo, and Glenn Miller. A glassed-off room in the Mission has been designated in René's honor and displays the upright piano on which he composed the tune, the reception desk from his office and several copies of the song's sheet music and other pieces of furniture, all donated by René's family.

Each year the City of San Juan Capistrano sponsors the Fiesta de las Golondrinas, a week-long celebration of this auspicious event. Tradition has it that the main flock arrives on March 19 (Saint Joseph's Day), and flies south on Saint John's Day, October 23.

- When the swallows come back to Capistrano

- That's the day you promised to come back to me

- When you whispered, "Farewell," in Capistrano

- 'twas the day the swallows flew out to sea

- excerpt from "When the Swallows Come Back to Capistrano" by Leon René

Other historic designations

- California Historical Landmark #227 — Diego Sepúlveda Adobe Estancia

- ASM International Historical Landmark (1988) — "Metalworking Furnaces"

- World Monuments Fund List of 100 Most Endangered Sites (2002) — "The Great Stone Church"

Notes

- ^ Leffingwell, p. 37

- ^ Young, p. 26

- ^ Young, p. 23

- ^ Newcomb, p. 16

- ^ Yenne, p. 8

- ^ Kelsey, p. 9

- ^ Wright, p. 37

- ^ Kelsey, p. 10

- ^ Mission San Juan Capistrano; retrieved on March 29, 2006

- ^ Newcomb, p. 15

- ^ Camphouse, p. 30

- ^ Yenne, p. 75

- ^ Chase and Saunders, p. 27

- ^ Yenne, p. 77

- ^ Jones p. 170

- ^ Young, p. 24

- ^ Cathers, p. 45

- ^ Duke, p. 241

- ^ Wright, p. 39

- ^ Yenne, P. 79

- ^ Leffingwell, p. 39

References

- Camphouse, Marjorie (1974). Guidebook to the Missions of California. Anderson, Ritchie & Simon, Los Angeles, CA. ISBN 0378037927.

- Cathers, David M. (1981). Furniture of the American Arts and Crafts Movement. The New American Library, Inc. ISBN 045303974.

- Chase, J. and Saunders, C. (1974). "Mission San Juan Capistrano." American West 40 (7) 22-29.

- Duke, Donald (1995). Santa Fe: The Railroad Gateway to the American West, Volume One. Golden West Books, San Marino, CA. ISBN 0-87095-110-6.

- Engelhardt, Zephyrin (1922). San Juan Capistrano Mission. Standard Printing Co., Los Angeles, CA.

- Kelsey, H. (1993). Mission San Juan Capistrano: A Pocket History. Interdisciplinary Research, Inc., Altadena, CA.

- Jones, Roger W. (1997). California from the Conquistadores to the Legends of Laguna. Rockledge Enterprises, Laguna Hills, CA.

- Leffingwell, Randy (2005). California Missions and Presidios: The History & Beauty of the Spanish Missions. Voyageur Press, Inc., Stillwater, MN. ISBN 0-89658-492-5.

- Newcomb, Rexford (1973). The Franciscan Mission Architecture of Alta California. Dover Publications, Inc., New York, NY. ISBN 0-486-21740-X.

- Wright, Ralph B. (1950). California's Missions. Hubert A. and Martha H. Lowman, Arroyo Grande, CA.

- Yenne, Bill (2004). The Missions of California. Thunder Bay Press, San Diego, CA. ISBN 1-59223-319-8.

- Young, Stanley and Melba Levick (1988). The Missions of California. Chronicle Books LLC, San Francisco, CA. ISBN 0-8118-3694-0.

- "Mission San Juan Capistrano". San Juan Capistrano Historical Society. Retrieved March 29.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)

See also

- Spanish missions in California

- Las Flores Asistencia

- USNS Mission Capistrano (AO-112) — a Mission Buenaventura Class fleet oiler built during World War II.

External links

- Official mission website

- Official parish website

- Elevation & Site Layout sketches of the Mission proper

- Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record

- Virtual Reality Panorama of "The Ruined Stone Church"

- Virtual Reality Panorama of the "Cloister Colonnade at Mission San Juan Capistrano"

- Virtual Reality Panorama of "The Inner Courtyard"

- Virtual Reality Panorama of "Father Serra's Chapel"

- Daily Life at Mission San Juan Capistrano (PDF)

- Indians of the Mission (PDF)

- "Little Chapters about San Juan Capistrano" by Father St. John O'Sullivan, 1912

- "Chinigchinich; a Historical Account of the Origin, Customs, and Traditions of the Indians at the Missionary Establishment of St. Juan Capistrano, Alta California Called The Acagchemem Nation" by The Reverend Father Friar Gerónimo Boscana, 1846

- Official website of the Juaneño Band of Mission Indians, Acjachemem Nation