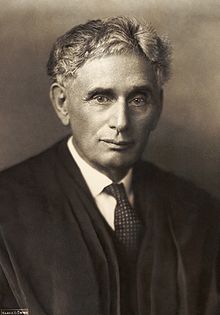

Louis Dembitz Brandeis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court | |

| In office June 5 1916 – February 13 1939 | |

| Nominated by | Woodrow Wilson |

| Preceded by | Joseph Rucker Lamar |

| Succeeded by | William O. Douglas |

| Personal details | |

| Spouse | Alice Goldmark |

| Alma mater | Harvard Law School |

Louis Dembitz Brandeis (13 November 1856 – 5 October 1941) was an American litigator, Supreme Court Justice, advocate of privacy, and developer of the Brandeis Brief in Muller v. Oregon. In addition, he helped lead the American Zionist movement.

Justice Brandeis was appointed by Woodrow Wilson to the Supreme Court of the United States in 1916 (sworn in on June 5), and served until 1939. It surprised many people when Wilson, the son of a Christian minister, appointed the first Jewish Supreme Court Justice.

Besides his educational record, Brandeis had for some years been a contributor to the progressive wing of the United States Democratic Party, and had published a noted book in support of competition rather than monopoly in business. President Wilson, who believed deeply that government must be a moral force for good, responded to similar sentiments in the thought and writings of Brandeis.

Brandeis University, a private university founded in 1948 and located in Waltham, Massachusetts, was named after him.

The University of Louisville's law school, where Brandeis is buried, is named for him (the Louis D. Brandeis School of Law), and his papers are archived in the school's library. In 2006, Louisville celebrated the 150th anniversary of Brandeis's birth. In celebration, a three-story tall canvas portrait of Brandeis adorns an office building on Liberty Street in Louisville. He was the brother-in-law of Charles Nagel, the last United States Secretary of Commerce and Labor.

Early life

Family roots

Louis Brandeis was born on November 13, 1856, in Louisville, Kentucky, as the youngest of four children. His Jewish parents, Adolph and Frederika (Dembitz), had emigrated to the United States from their childhood homes in Prague, Czechoslovakia, which was the principal city of Bohemia. They emigrated as part of their extended family due to both economic and political factors:

According to legal historians Diana Klebanow and Franklin Jonas, their decision to go to America was also influenced by the Revolutions of 1848 which led to a series of political upheavals throughout the European continent. They write that although the families had been "liberal in their political views and sympathetic to the rebel cause, [they were] shocked by the anti-Semitic riots that erupted in Prague while the city was in the hands of the Czech rebels." [1] : 55 In addition, Jews in the Hapsburg Empire had been required to pay "special" business taxes.

As a result of the growing mistreatment of Jews in their homeland, the elders dispatched Adolph Brandeis to America "to prepare the way for the possible immigration of his relatives." Klebanow and Jonas write, "after spending a few months in the Midwest, Adolph [was] impressed by the nation's institutions and was moved by the tolerance he had encountered among its people." He wrote to Frederika: "America's progress is the triumph of the rights of man."[1]: 56

The Brandeis family settled in Louisville partly because it was one of the prospering river ports of the Midwest. Louis's father developed a grain-merchandising business but suffered setbacks during the Long Depression of the 1870s. [2]: 121 His earliest childhood was also shaped by the Civil War, as the family was forced to move to Indiana temporarily for its safety. The Brandeis family was known to support Abraham Lincoln's call for the end of slavery and their abolitionist beliefs angered their neigbors in Louisville. "Kentucky was one of its many batlegounds, ... and his family was firmly in the antislavery camp."[1]: 57

Family life

Klebanow and Jonas write that the Brandeises were "a cultured family who never talked of business or money matters at the dinner table, discussing instead a wide array of subjects pertaining to history, politics, and culture as well as to their daily experiences." Having been raised partly one German culture, Louis read and appreciated the writings of Goethe and Schiller, and his favorite composers were Beethoven and Schumann. [1]

In their religious beliefs, although his family was Jewish, only his extended family practiced a more conservative form of Judaism, while his parents practiced a more relaxed form, even celebrating the main Christian holidays along with most of their community. [2] To the Brandeis family, Christmas "was always a purely secular occasion," notes Klebanow and Jonas. "While rejecting organized religion, Frederika and Adolph raised their children to be high-minded idealists."[1] In later years, Frederika wrote of this period:

- "I believe that only goodness and truth and conduct that is humane and self-sacrificing toward those who need us can bring God nearer to us ... I wanted to give my children the purest spirit and the highest ideals as to morals and love. God has blessed my endeavors." [3]: 28

Childhood education

According to historian John Vile, Louis grew up in "a family enamored with books, music, and politics, perhaps best typified by his revered uncle, Lewis Dembitz, a refined, educated man who served as a delegate to the Republican convention in 1860 that nominated Abraham Lincoln for president."[2]

In school, Louis was a serious student in languages and other basic courses and usually achieved top scores. Brandeis graduated from the Louisville Male High School at age 14 with the highest honors. When he was sixteen, the Louisville University of the Public Schools awarded him a gold medal for "excellence in all his studies." [4]: 10 . However, in 1872, "Adolph Brandeis became so concerned about the impending economic depression," writes Vile, "that he moved his family to Europe..." After a period spent travelling, Louis spent two years studying at the Annen-Realschule school in Dresden, Germany, where he excelled. As Vile explains, "it was this training that Brandeis later credited for teaching him critical thinking and for his desire to return to the United States to study law."[2]

Law school

Returning to the US in 1875, Brandeis next entered Harvard Law School at the age of nineteen. According to Klebanow and Jonas, "he chose the law as his life's work largely out of admiration for his uncle, Lewis Dembitz, a frequent visitor to the Brandeis household, whom he idolized for his wide learning and skill in debate."[1]: 58 Despite the fact that he entered the school without any formal training or financial assistance from his family, who had suffered during the depression, "he proved to be an extraordinary student," notes Vile.

During his time at Harvard, the teaching of law was undergoing a change of method from relying on the traditional, memorization-reliant, "black letter" case law, to a more flexible and interactive Socratic method, using prior cases as a basis for discussion to instruct students in legal reasoning. Instead of memorizing textbooks, students would examine individual cases. "Brandeis took readily to the new methods and immediately made his presence felt through his contributions to class discussions."[1] He also "began to demonstrate considerable skills as a budding judge with his participation in the Pow-Wow law club, an activity similar to today's law school moot courts", writes Vile.

In a letter while at Harvard, he wrote of his "desperate longing for more law" and of the "almost ridiculous pleasure which the discovery or invention of a legal theory gives me." He referred to the law as his "mistress," holding a grip on him that he could not break.[5]

Unfortunately, his eyesight began failing as a result of the large volume of required reading and the poor visibility under gaslights. The school doctors suggested he "should give up his studies entirely." But instead, he found another alternative, and paid fellow law students to read the textbooks aloud, while he would attempt to memorize the legal principles. Despite the difficulties, his academic work and memorization talents were so impressive that, writes Vile, "he graduated as the valedictorian, achieving what was then the highest grade point average in the history of the legendary school."[2]: 122 According to Klebanow and Jonas, his grades set a record "that stood for eight decades."[1] Brandeis later wrote: "Those years were among the happiest of my life. I worked! For me, the world's center was Cambridge."[3]: 47

Early career in law

After graduation, he stayed on at Harvard for another year, where he continued to study law on his own while also earning a small income by tutoring other law students. In 1878 he was admitted to the Missouri bar[6] and accepted a job with a law firm in St. Louis, where he filed his first brief and published his first law review article.[1] However, after seven months, he tired of the minor casework and accepted an offer by his Harvard classmate, Samuel Warren, to set up a law firm in Boston. They were close friends at Harvard where Warren ranked second in the class to Brandeis's first. Warren was also the son of a wealthy Boston family and their new firm was able to benefit from his family's connections.

Soon after returning to Boston, while waiting for the law firm to gain clients, he was appointed law clerk to Horace Grey, the chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court, where he worked for two years. He was admitted to the Massachusetts bar without taking an examination, which he later wrote to his brother, was "contrary to all principle and precedent." According to Klebanow and Jonas, "the speed with which he was admitted probably was due to his high standing with his former professors at Harvard Law as well as to the influence of Chief Justice Grey."[1]: 59

First law firm: Warren and Brandeis

Their new firm was eventually successful, having gained new clients from within the state and in several neighboring states as well. Their "former professors referred a number of clients to the two fledling lawyers,"[1] garnering Brandeis more financial security and the freedom to eventually take an active role in progressive causes.

As partner in his law firm, he worked as a consultant and advisor to businesses, but was also "a capable litigator who reveled in the challenge of the courtroom," notes Klebanow and Jonas. In a letter to his brother, he wrote, "There is a certain joy in the exhaustion and backache of a long trial which shorter skirmishes cannot afford."[1] In 1889, he pleaded for the first time before the U.S. Supreme Court as the eastern counsel of the Wisconsin Central Railroad, a case which he won. According to Alfred Lief, Brandeis's biographer, Chief Justice Melville Fuller was "so impressed by Brandeis's presentation that he would soon afterward call him 'the ablest attorney he knew of in the East'."[7]

Acting as business advisor

According to Klebanow and Jonas, when taking on business clients, he would insist on two major conditions: "first, that he would never have to deal with intermediaries, but only with the person in charge ... second, that he must be permitted to offer advice on any and all aspects of the firm's affairs" that seemed relevant. "He saw himself as truly a 'counselor at law,' rather than as merely a strategist in lawsuits. The idea was to help the client to avoid lawsuits, strikes, and other crises by timely advice..."[1] As he wrote in 1911, "I would rather have clients than be somebody's lawyer."[3]: 86 In a note found among his papers, he reminded himself to "advise client on what he should have, not what he wants."[3]: 20

Setting moral standards

Brandeis was unusual among lawyers because "he refused to serve in a cause that he considered bad," write Klebanow and Jonas. If he believed a client to be in the wrong, "either he would persuade his clients to make amends ... or he would withdraw from the case."[1] Once, uncertain as to the rightness of his client's case, he wrote the client, "The position that I should take if I remained in the case would be to give everybody a square deal."[3]: 233

Developing the Right to Privacy

Between 1888 and 1890, Brandeis and his law partner, Samuel Warren, collaborated on writing three scholarly articles which were published in the Harvard Law Review. Their third, entitled The Right to Privacy, was "by far the most important," according to Klebanow and Jonas. It was later credited by noted legal scholar Roscoe Pound as having accomplished 'nothing less than adding a chapter to our law.'"

The issue dealt with the development of the modern newspapers and the new technology of "snapshot photography," which resulted in the publication of photographs of private persons along with their words and statements, all without consent. They argued that private individuals were being continually injured and the "moral standards of society as a whole" were being weakened. Klebanow and Jonas describe their motives in writing the article:

- "In their search for a principle of law that would protect privacy, Warren and Brandeis contended that since individuals may under the common law normally decide (as in copyright law) whether to communicate to others their thoughts, sentiments, and emotions, it followed that a right to privacy already existed. 'The cases referred to ... would be merely another application of an existing rule.'"[1]: 61 [8]

- Excerpts from The Right to Privacy (1890)

- "That the individual shall have full protection in person and in property is a principle as old as the common law; but it has been found necessary from time to time to define anew the exact nature and extent of such protection. Political, social, and economic changes entail the recognition of new rights, and the common law, in its eternal youth, grows to meet the demands of society.

- . . . .

- "The press is overstepping in every direction the obvious bounds of propriety and of decency. Gossip is no longer the resource of the idle and of the vicious, but has become a trade, which is pursued with industry as well as effrontery. To satisfy a prurient taste the details of sexual relations are spread broadcast in the columns of the daily papers. To occupy the indolent, column upon column is filled with idle gossip, which can only be procured by intrusion upon the domestic circle. The intensity and complexity of life, attendant upon advancing civilization, have rendered necessary some retreat from the world, and man, under the refining influence of culture, has become more sensitive to publicity, so that solitude and privacy have become more essential to the individual; but modern enterprise and invention have, through invasions upon his privacy, subjected him to mental pain and distress, far greater than could be inflicted by mere bodily injury." [8]

New phase as public lawyer

In 1889, Brandeis entered a new phase in his legal career when his partner, Samuel Warren, withdrew from their partnership to take over his recently deceased father's paper company. He took on cases alone from then on with the help of colleagues, two of which he made partners in his new firm, Brandeis, Dunbar, and Nutter, eight years later in 1897.[3]: 82–86

He won his first important victory in 1891, where he persuaded the legislature of Massachusetts "to make the liquor laws less restrictive and ... in his view, more reasonable and enforceable." In arguing his case, he managed "to devise a viable middle course." By "moderating" the existing regulations, he told the lawmakers that "they would, at a single stroke, deprive the liquor dealers of their incentive to violate the laws and to corrupt through bribery the politics of Massachusetts."[7]: 34–37 The legislature was won over by his arguments and the regulations were changed.

Personal life and marriage

Brandeis became engaged to Alice Goldmark, of New York, in 1890. He was then thirty-four years of age and had previously found little time for courtship. Alice was the daughter of a physician who had emigratred to America from Austria after the collapse of the Revolution of 1848. They were married on March 23, 1891, at the home of her parents in New York City in a civil ceremony. The newlywed couple moved into a modest home in Boston's Beacon Hill district and had two daughters, Susan, born in 1893 and Elizabeth, 1896. [3]: 72–78

According to Klebanow and Jonas, the Brandeis family "lived well but without extravagance." With the continuing success of his law practice, they later purchased a vacation cottage in Dedham where they would spend many of their weekends and summer vacations. Unexpectedly, his wife's health soon became frail, so in addition to his professional duties he found it necessary to manage the family's domestic affairs.[2]

- "They shunned the more luxurious ways of their class, holding few formal dinner parties and avoiding the luxury hotels when they traveled. Brandeis would never fit the stereotype of the wealthy man. Although he belonged to a polo club, he never played polo. He owned no yacht, just a canoe that he would paddle by himself on the fast-flowing river that adjoined his cottage in Dedham."[4]: 45–49 He wrote to his brother of his brief trips to Dedham: "Dedham is a spring of eternal youth for me. I feel newly made and ready to deny the existence of these grey hairs."

Becoming a public advocate

With their finances secure, Louis and Alice resolved that he should devote most of his time to public causes.[1]: 63 He soon began in earnest by accepting a case on behalf of Alice N. Lincoln, a Boston philanthropist and noted crusader for the poor. During 1894 he appeared at public hearings to promote investigations into conditions in the public poor-houses. Lincoln, who had visited these poor-houses for years, "charged that the inmates were dwelling in misery and that the temporarily unemployed were being thrown in together callously with the mentally ill and hardened criminals."[1] Brandeis spent nine months and held fifty-seven public hearings, at one such hearing proclaiming, "Men are not bad. Men are degraded largely by circumstances. . . . It is the duty of every man ... to help them up and let them feel that there is some hope for them in life." As a result of the hearings, the board of aldermen decreed that the administration of the poor law would be completely reorganized.[7]: 52–54

Against monopolies

During the 1890s Brandeis began to question his views on the "industrial order in America," write Klebanow and Jonas. Becoming more aware that there was a growing number of "giant firms" which were capable of dominating whole industries, he began to lose faith that the economic system was able to regulate them for the public's welfare. As a result, he began denouncing "cut-throat competition" and fretted over the dangers of monopoly. "He became more aware of the plight of workers and more sympathetic to the labor movement."[1]

However, he also recognized the limits of trying to split up some monopolies. In an address in 1912, he said:

- "Understand, I am not for monopoly when we can help it. We intend to restore competition. We intend to do away with the conditions that make for monopoly. But there are certain monopolies that we cannot prevent. I understand that the steel trust is not an absolute monopoly, but if it were, what would be the use of splitting up the steel trust into companies controlled by Morgan, Carnegie, and Rockefeller, say? Would it ameliorate conditions at all? Would it make prices lower to the consumer?-the wages and the conditions higher to the worker? Don't you suppose that these three fellows would agree on prices and methods unofficially?" [9]

Against powerful corporations

As Klebanow and Jonas make clear, Brandeis was becoming increasingly conscious of and hostile to powerful corporations and the trend toword bigness in American industry and finance. As early as 1895 he had pointed out the harm that giant corportions could do to competitors, customers, and their own workers. The growth of industrialization was creating mammoth companies which he felt threatened the well-being of millions of Americans.[1]: 76 Although the Sherman Anti-Trust Act was enacted in 1890, it was not until the 1900s that there was any major effort to apply it.

In fact, by 1910 Brandeis noticed that even America's leadership, including President Theodore Roosevelt, were beginning to question the value of antitrust policies. Business experts were contending that "there was nothing that could prevent to continuing concentration of industry and therefore, like it or not, big business was here to stay."[1]: 76 As a result, leaders like Roosevelt saw the need to "regulate," but not limit, the growth and operation of corporate monopolies, whereas Brandeis felt the trend to bigness should be slowed, if not reversed. His experience convinced him that monopolies and trusts were "neither inevitable nor desirable." In support of Brandeis's position were presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan and Robert M. LaFollette, senator from Wisconsin. [1]

Brandeis furthermore denied that large trusts were more efficient than the smaller firms which were generally driven out of business. He argued the opposite was often true, that monopolistic enterprises became "less innovative" because, he wrote, their "secure positions freed them from the necessity which has always been the mother of invention." To him there was no way an executive could learn all the details of running a huge and unwieldy company. "There is a limit to what one man can do well," he wrote. Brandeis was naturally aware of the economies of scale and initially lower prices offered by growing companies, but he emphasized the future by claiming that once a trust drove out its competition, "the quality of its products tended to decline while the prices charged for them tended to go up." Eventually, he felt, the trusts would be like "clumsy dinosaurs, which, if they ever had to face real competition, would collapse of their own weight." In an address to the Economic Club of New York in 1912, he said:

- "We learned long ago that liberty could be preserved only by limiting in some way the freedom of action of individuals; that otherwise liberty would necessarily yield to absolutism; and in the same way we have learned that unless there be regulation of competition, its excesses will lead to the destruction of competition, and monopoly will take its place.

- "A large part of our people have also learned that efficiency in business does not grow indefinitely with the size of business. Very often, a business grows in efficiency as it grows from a small business to a large business; but there is a unit of greatest efficiency in every business, at any time, and a business may be too large to be efficient, as well as too small. Our people have also learned to understand the true reason for a large part of those huge profits which have made certain trusts conspicuous. They have learned that these profits are not due in the main to efficiency, but are due to the control of the market, to the exercise by a small body of men of the sovereign taxing power."[9]

Against public corruption

In 1896, he was asked to lead the fight against a Boston transit company which was trying to gain concessions from the state legislature that would have given it a "stranglehold on the city's emerging subway system." Brandeis prevailed and the legislature enacted his bill.[4]: 57–61

However, the transit franchise struggle revealed that many of Boston's politicians had placed "friends" and "ward heelers" on the payrolls of the private transit companies. According to Lief, "One alderman alone had found work in this way for 200 of his followers."[7]: 70 Lief adds that "in Boston, as in other American cities, such abuses were part of a larger pattern of corruption in which graft and bribery were commonplace. Convicted felons would return from prison terms to resume their political careers."[7]

"Always the moralist," writes Brandeis biographer Thomas Mason, "Brandeis declared that 'misgovernment in Boston had reached the danger point.'" He announced that from then on he would keep a ledger of "good and bad deeds," making a record of Boston's politicians accessible to all the city's voters.[3] If one of his public addresses in 1903, he stated his goal:

- "We want a government that will represent the laboring man, the professional man, the businessman, and the man of leisure. We want a good government, not because it is good business but because it is dishonorable to submit to a bad government. The great name, the glory of Boston, is in our keeping."[3]: 121

In 1906, Brandeis won a modest victory when the state legislature "enacted an anticorruption measure that he had drafted" which made it a punishable crime for a public official to solicit a job from a regulated public utility or for an officer of such a company to offer such favors.[3]: 121

Becoming the "People's Lawyer"

Klebanow and Jonas write that Brandeis had begun to evolve into "the people's lawyer." He was no longer accepting payment for "public interest" cases even when they required pleadings before judges, legislative committees, or administrative agencies. He also became involved in developing public opinion through writing magazine articles, making speeches, or helping form interest groups. He "insisted on serving without pay so that he would be free to address the wider issues involved rather than confine himself merely to the case at hand."[1]: 66

In a 1905 address to law students and others at Harvard, he explained his philosophy:

- "The great achievement of the English-speaking people is the attainment of liberty through law. It is natural, therefore, that those who have been trained in the law should have borne an important part in that struggle for liberty and in the government which resulted....

- . . . .

- Instead of holding a position of independence, between the wealthy and the people, prepared to curb the excesses of either, able lawyers have, to a large extent, allowed themselves to become adjuncts of great corporations and have neglected the obligation to use their powers for the protection of the people. We hear much of the 'corporation lawyer,' and far too little of the 'people's lawyer.' The great opportunity of the American Bar is and will be to stand again as it did in the past, ready to protect also the interests of the people."[10]

By that time, with his finances secure, he had begun taking on cases where he felt he could make a difference and in some way improve the life of the average person.

Life insurance industry

In March 1905, he became counsel to a New England policyholder's committee concerned that their scandal-ridden insurance company would file bankruptcy and the policyholders would lose their investments and insurance protection. He insisted on serving without pay in order to give him the freedom to address the wider issues involved. He then spent the next year studying the workings of the life insurance industry, often writing articles and giving speeches about his findings, at one point describing their practices as "legalized robbery."[4]: 76–77 By 1906 he concluded that life insurance was "simply a bad bargain for the vast majority of policyholders" due mostly to the inefficiency of the industry. He also learned that the policies of "poorly paid breadwinners" were cancelled when they missed a payment, due to little-understood clauses within the policy. As a result, he discovered that most policies lapsed, and only one out of eight original policyholders actually received benefits, leading to large insurance company profits.[1]

He succeeded in "creating a groundswell" in Massachusetts with his personal campaign of educating the public, and created a new "savings bank life insurance" system with the help of progressive businessmen, social reformers, and trade unionists. By March 1907, the Savings Bank Insurance League had 70,000 members and his "face and name were appearing regularly in newspapers..."[3]: 164 He persuaded the former governor, a Republican, to become its president, and the current governor stated in his annual message his wish for the legislature to study plans for "cheaper insurance that may rob death of half of its terrors for the worthy poor." Brandeis drafted his own bill, and three months later the "savings bank insurance measure was signed into law." He always this bill one of "his greatest achievements" and, like a proud parent, he "kept a watchful eye on it." [3]: 177–180

J.P. Morgan and the railroad monopoly

While still involved with the life insurance industry, he took on another public interest case: the struggle to prevent New England's largest railroad company, New Haven Railroad, from gaining control of its chief competitor, the Boston and Maine Railroad. His foes were the most powerful he had ever encountered, including the region's most affluent families, Boston's legal establishment, and the large State Street bankers. Klebanow and Jonas add that "the New Haven had been under the control of J.P. Morgan, the most powerful of all American bankers and probably the most dominating figure in all of American business."[1]: 69

J.P. Morgan had "pursued a policy of expansion" by acquiring many of the line's competitors to make the New Haven into a single unified network. Acquisitions included "not only railways, but also trolley and shipping companies," according to historian John Weller.[11]: 41–52 In June, 1907, he was asked by Boston and Maine stockholders to present their cause to the public, a case which he again took on by insisting on serving without payment, "leaving him free to act as he thought best."

After months of extensive research, he published a seventy-page booklet in which he argued that New Haven's acquisitions were putting its financial condition in jeopardy, and predicted that within a few years it would be forced to cut its dividends or become insolvent. He spoke in public warning Boston's citizens that the New Haven "sought to monopolize the transportation of New England and raising the prospect of alien control." He quickly found himself "under attack" by not only the New Haven, but also by many newspapers, magazines, chambers of commerce, Boston bankers, and college professors.[1]: 69 "I have made," he wrote his brother, "more enemies than in all my previous fights together."[1]: 69

By 1908, however, the New Haven's proposed merger was "dealt several stunning blows," write Klebanow and Jonas. Among them, the Massachusetts Supreme Court ruled that New Haven had acted illegally during earlier acquisitions. He also met twice with President Theodore Roosevelt, who convinced the U.S. Department of Justice to file suit, in 1908, against New Haven for antitrust violations. And according to Weller, at a hearing in front of the Interstate Commerce Commission in Boston, New Haven's president "admitted that the railroad had maintained a floating slush fund that was used to make 'donations' to politicians who cooperated."[11]: 49–154

Within a few years, "Haven's finances came undone just as Brandeis had predicted they would," note Klebanow and Jonas. By the spring of 1913, the Department of Justice launched a new investigation, and the following year the Interstate Commerce Commission charged the New Haven with "extravagance and political corruption and its board of directors with dereliction of duty."[1] As a result, the New Haven gave up its "struggle for expansion" by disposing of its Boston and Maine stock and selling off its recent acquisitions of competitors. As Mason describes it, "after a nine-year battle against a powerful corporation ... and in the face of a long, bitter campaign of personal abuse and vilification, Brandeis and his cause again prevailed."[3]: 203–214

Women's workplace laws

In 1908 he chose to represent the state of Oregon in the case of Muller v. Oregon, to the U.S. Supreme Court. At issue was whether it was constitutional for a state law to limit the hours that female workers could work. Up until this time it was considered an "unreasonable infringement of freeedom of contract" between employers and their employees for a state to set any wages or hours legislation.

Brandeis, however, discovered that earlier Supreme Court cases limited the rights of contract when the contract had "a real or substantial relation to public health or welfare." He therefore decided that the best way to present the case would be to demonstrate through an abundance of workplace facts, "a clear connection between the health and morals of female workers" and the hours that they were required to work. To accomplish this, he filed what has become known today as the "Brandeis Brief." Here, he presented a much shorter traditional brief, but included more than a hundred pages of documentation, including social worker reports, medical conclusions, factory inspector observations, and other expert testimonials, which together showed a preponderance of evidence that "when women worked long hours, it was destructive to their health and morals."[4]: 120–121

The strategy worked, and the Oregon law was upheld. Justice David Brewer directly credited Brandeis with demonstrating "a widespread belief that woman's physical structure and the functions that she performs ... justify special legislation." Thomas Mason writes that with the Supreme Court affirming Oregon's minimum wage law, Brandeis "became the leading defender in the courts of protective labor legislation" .[3]: 250–253 [12]

Supporting Wilson for president

Brandeis's positions on regulating large corporations and monopolies carried over into the presidential campaign of 1912. Democratic candidate Woodrow Wilson made it "the central issue," and, according to Wilson historian Arthur Link, "part of a larger debate over the future of the economic system and the role of the national government in American life." Whereas the Republican candidate, Theodore Roosevelt, felt that trusts were inevitable and should be regulated, Wilson and his party aimed to "destroy the trusts" by ending special privileges, such as protective tarrifs and other unfair business practices that made them possible.[13]: 1–24

Supreme Court Justice

Overcoming significant opposition to his appointment (notably from ex-President William Howard Taft and the then Harvard University president A. Lawrence Lowell),[14] Brandeis was confirmed to the Supreme Court on June 1, 1916, on a largely party-line 47-22 vote, with one Democrat (Francis G. Newlands of Nevada) opposed and three Republicans in favor.[15] Brandeis learned of his confirmation riding the train home from his office in Boston to his house in Dedham; that night his wife greeted him as "Mr. Justice." He would become one of the most influential and respected Supreme Court Justices in United States history. His votes and opinions envisioned the greater protections for individual rights and greater flexibility for government in economic regulation that would prevail in later courts.

In his widely cited dissenting opinion in Olmstead v. United States (1928), Brandeis argued, as he had in an influential law-review article prior to being nominated to the Court, that the Constitution protected a "right of privacy," calling it "the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by civilized men." Brandeis's position in Olmstead became the law of the land in Katz v. United States, of 1967, which overturned Olmstead.

Brandeis also joined with fellow justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. in calling for greater Constitutional protection for speech, disagreeing with the Court's analysis in upholding a conviction for aiding the Communist Party in Whitney v. California (1927) (though concurring with the disposition of the case on technical grounds). Brandeis's opinion foreshadows the greater speech protections enforced by the Earl Warren Court.

Brandeis also opposed the Supreme Court's doctrine of "liberty of contract," which often acted to shield business from government regulation on the right of employers and employees to freely contract with each other, and argued that the Court should adopt a broader view of what constituted "commerce" which could be regulated by Congress, foreshadowing decisions such as 1941's United States v. Darby.

During the 1932-1937 Supreme Court terms, Brandeis, along with Justices Cardozo and Stone, was a member of the Three Musketeers, which was considered to be the liberal faction of the Supreme Court. The three were highly supportive of President Roosevelt's New Deal programs, which most of the other Supreme Court Justices opposed. In New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann (1932), Brandeis in dissent famously urged that the states should be able to be "laboratories" for innovative government action, in the face of the Supreme Court's frequent invalidation of state measures regulating business. Brandeis's views on "liberty of contract" would prevail in the long run, culminating in the seminal Supreme Court case of West Coast Hotel v. Parrish (1937). He was urging deference to legislative judgments when fundamental individual liberties are not seriously threatened and showing a healthy respect for the vertical (federal vs. states vs. individual) and horizontal (judicial vs. legislative) separations of power.

As an octogenarian, Brandeis was deeply offended by his friend Franklin Roosevelt's court-packing scheme of 1937, with its implication that elderly justices needed special help to carry out their duties. Brandeis retired from the Court in 1939, to be replaced by William O. Douglas.

Zionist leader

Brandeis also became a prominent American Zionist.[16] Zionism was the movement to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Not raised religious, Brandeis became involved in Zionism through a 1912 conversation with Jacob de Haas, editor of a Boston Jewish weekly and a follower of Theodore Herzl. Brandeis became active in the Federation of American Zionists as a result. With the outbreak of World War I, the Zionist movement's headquarters in Berlin became ineffectual, and American Jewry had to assume larger responsibility for the Zionist movement. When the Provisional Executive Committee for Zionist Affairs was established in New York, Brandeis accepted unanimous election to be its head. In this position from 1914 to 1918, Brandeis was the leader of American Zionism. Brandeis embarked on a speaking tour in the fall and winter of 1914-1915 to support the Zionist cause. Brandeis emphasized the goal of self-determination and freedom for Jews through the development of a Jewish homeland in Palestine and the compatibility of Zionism and American patriotism. He expressed these views in his short book, The Jewish Problem, How to Solve It.

Brandeis brought his influence in the Woodrow Wilson administration to bear in the negotiations leading up to the Balfour Declaration. Brandeis split with the European branch of Zionism, led by Chaim Weizmann, and resigned his leadership role in 1921. He retained membership, however, and remained active in Zionism until the end of his life.[17]

End of life

Brandeis died in Washington, D.C., October 5 1941. The cremated remains of Justice Brandeis are interred under the portico of the Louis Brandeis Law school at the University of Louisville.[18] A large collection of Brandeis's personal and official files is also archived at that institution.

Namesake institutions

- Brandeis University, in Waltham, Massachusetts, was named after the Justice. Several Brandeis Awards are named in his honor. A collection of his personal papers is available at the Robert D. Farber University Archives & Special Collections Department at Brandeis University.

- The University of Louisville's Louis D. Brandeis School of Law is also named after him. The remains of both Justice Brandeis and his wife are interred beneath the school.[19] His remains are appropriately located approximately fifty yards from Auguste Rodin's The Thinker. His professional papers are archived at the library there. Justice Brandeis was responsible for making the law school one of only thirteen Supreme Court repositories in the nation. The school's principal law review publication, the Brandeis Law Journal, is likewise named in his honor. The law school's Louis D. Brandeis Society awards the Brandeis Medal.

- Kibbutz Ein Hashofet (Hebrew: עין השופט) in Israel (founded 1937) is named after Louis D. Brandeis. "Ein Hashofet" means literally "Spring of the Judge". The name was chosen due to Brandeis' Zionism.

- One of the buildings of Hillman Housing Corporation, a housing cooperative founded by the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, in the Lower East Side of Manhattan is named after him.

- A New York City Public Schools high school, "Louis D. Brandeis High School", is named after the justice.

- A private Jewish day-school in Lawrence, New York, the Brandeis School, is also named after the justice.

- Brandeis Hillel Day School (a K-8 independent Jewish school with campuses in San Francisco, CA and San Rafael, CA) is named after Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis and Rabbi Hillel.

- The Brandeis-Bardin Institute (in Simi Valley, near Los Angeles) is a Jewish educational outreach resource.

- Louis D. Brandeis High School (San Antonio, Texas) is also named after him. Brandeis became the ninth Justice so honored within the Northside Independent School District, which names all of its high schools for Supreme Court Justices.

References

Selected works by Brandeis

- The Brandeis Guide to the Modern World, Alfred Lief, editor (Boston: Little Brown & Co., 1941)

- Brandeis on Zionism, Solomon Goldman, editor (Washington, D.C.: Zionist Organization of America, 1942)

- Business, a Profession, Ernest Poole, editor (Boston, MA: Small, Maynard, 1914)

- The Curse of Bigness, Osmond K. Fraenkel, editor (New York, NY: Viking Press, 1934)

- The Words of Justice Brandeis, Solomon Goldman, editor (New York, N.Y.: Henry Schuman, 1953)

- Other People's Money and How the Bankers Use It (New York, NY: Stokes, 1914)

- Melvin I. Urofsky & David W. Levy, editors, Half Brother, Half Son: The Letters of Louis D. Brandeis to Felix Frankfurter (University of Oklahoma Press, 1991)

- Melvin I. Urofsky, editor, Letters of Louis D. Brandeis (State University of New York Press, 1980)

- Melvin I. Urofsky & David W. Levy, editors, Letters of Louis D. Brandeis (State University of New York Press, 1971-1978, 5 vols.)

- Louis Brandeis & Samuel Warren "The Right to Privacy," 4 Harvard Law Review 193-220 (1890-91)

- "The Living Law," 10 Illinois Law Review 461 (1916)

- "The Opportunity in the Law," 39 American Law Review 555 (1905)

Books about Brandeis

- Jack Grennan, Brandeis & Frankfurter: A Dual Biography (New York, N.Y.: Harper & Row, 1984)

- Alexander M. Bickel, The Unpublished Opinions of Mr. Justice Brandeis (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1957)

- Robert A. Burt, Two Jewish Justices: Outcasts in the Promised Land (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1988)

- Nelson L. Dawson, editor, Brandeis and America (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1989)

- Jacob DeHaas, Louis D. Brandeis, A Biographical Sketch (Blach, 1929)

- Felix Frankfurter, editor, Mr. Justice Brandeis (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1932)

- Ben Halpern, A Clash of Heroes: Brandeis, Weizman, and American Zionism (New York, N. Y.: Oxford University Press, 1986)

- Samuel J. Konefsky, The Legacy of Holmes & Brandeis: A Study in the Influence of Ideas (New York, N.Y.: Macmillan Co., 1956)

- David W. Levy, editor, The Family Letters of Louis D. Brandeis (University of Oklahoma Press, 2002)

- Alfred Lief, Brandeis: The Personal History of an American Ideal (New York, N.Y.: Stackpole Sons, 1936)

- Alfred Lief, editor, The Social & Economic Views of Mr. Justice Brandeis (New York, N.Y.: The Vanguard Press, 1930)

- Jacob Rader Marcus, Louis Brandeis (Twayne Publishing, 1997)

- Alpheus Thomas Mason, Brandeis: A Free Man's Life (New York, N.Y.: The Viking Press, 1946)

- Alpheus Thomas Mason, Brandeis & The Modern State (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1933)

- Thomas McCraw, Prophets of Regulation: Charles Francis Adams, Louis D. Brandeis, James M. Landis, Alfred E. Kahn (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984)

- Ray M. Mersky, Louis Dembitz Brandeis 1856-1941: Bibliography (Fred B Rothman & Co; reprint ed., 1958)

- Bruce Allen Murphy, The Brandeis/Frankfurter Connection: The Secret Activities of Two Supreme Court Justices (New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press, 1982)

- Lewis J. Paper, Brandeis: An Intimate Biography of one of America's Truly Great Supreme Court Justices (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Pretice-Hall, Inc., 1983)

- Catherine Owens Peare, The Louis D. Brandeis Story (Ty Crowell Co., 1970)

- Edward A. Purcell, Jr., Brandeis and the Progressive Constitution: Erie, the Judicial Power, and the Politics of the Federal Courts in Twentieth-Century America (New Haven, CN: Yale University Press 2000)

- Philippa Strum, Brandeis: Beyond Progressivism (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1993)

- Philippa Strum, editor, Brandeis on Democracy (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1995)

- Philippa Strum, Louis D. Brandeis: Justice for the People (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1988)

- A.L. Todd, Justice on Trial: The Case of Louis D. Brandeis (New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill, 1964)

- Melvin I. Urofsky, A Mind of One Piece: Brandeis and American Reform (New York, N.Y., Scribner, 1971)

- Melvin I. Urofsky, Louis D. Brandeis, American Zionist (Jewish Historical Society of Greater Washington, 1992) (monograph)

- Melvin I. Urofsky, Louis D. Brandeis & the Progressive Tradition (Boston, MA: Little Brown & Co., 1981)

- Melvin I. Urofsky, Louis D. Brandeis: A Life (forthcoming)[1]

- Nancy Woloch, Muller v. Oregon: A Brief History with Documents (Boston, MA: Bedford Books, 1996)

Select articles

- Bhagwat, Ashutosh A. (2004). "The Story of Whitney v. California: The Power of Ideas". In Dorf, Michael C. (ed.) (ed.). Constitutional Law Stories. New York: Foundation Press. pp. 418–520. ISBN 1587785056.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Blasi, Vincent (1988). "The First Amendment and the Ideal of Civic Courage: The Brandeis Opinion in Whitney v. California". William & Mary Law Review. 29: 653.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - Bobertz, Bradley C. (1999). "The Brandeis Gambit: The Making of America's 'First Freedom,' 1909-1931". William & Mary Law Review. 40: 557.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - Brandes, Evan B. (2005). "Legal Theory and Property Jurisprudence of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. and Louis D. Brandeis: An Analysis of Pennsylvania Coal Company v. Mahon". Creighton Law Review. 38: 1179.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - Collins, Ronald (2005). "Curious Concurrence: Justice Brandeis's Vote in Whitney v. California". Supreme Court Review. 2005: 1–52.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Collins, Ronald (1983). "Looking Back on Muller v. Oregon". American Bar Association Journal. 69: 294–298, 472–477.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Erickson, Nancy (1989). "Muller v. Oregon Reconsidered: The Origins of a Sex-Based Doctrine of Liberty of Contract". Labor History. 30: 228–250.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - Farber, Daniel A. (1995). "Reinventing Brandeis: Legal Pragmatism For the Twenty-First Century". U. Ill. L. Rev. 1995: 163.

- Frankfurter, Felix (1916). "Hours of Labor and Realism in Constitutional Law". Harvard Law Review. 29: 353–373. doi:10.2307/1326686.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - Spillenger, Clyde (1996). "Elusive Advocate: Reconsidering Brandeis as People's Lawyer". Yale Law Journal. 105: 1445.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - Spillenger, Clyde (1992). "Reading the Judicial Canon: Alexander Bickel and the Book of Brandeis". Journal of American History. 79 (1): 125–151. doi:10.2307/2078470.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - Urofsky, Melvin I. (2005). "Louis D. Brandeis: Advocate Before and On the Bench". Journal of Supreme Court History. 30: 31.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - Urofsky, Melvin I. (1985). "State Courts and Protective Legislation during the Progressive Era: A Reevaluation". Journal of American History. 72: 63–91. doi:10.2307/1903737.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - Vose, Clement E. (1957). "The National Consumers' League and the Brandeis Brief". Midwest Journal of Political Science. 1: 267–290.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help)

Selected opinions

- Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Authority (1936) (concurring)

- Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins (1938) (majority)

- Gilbert v. Minnesota (1920) (dissenting)

- New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann (1932) (dissenting)

- Olmstead v. United States (1928) (dissenting)

- Ruthenberg v. Michigan (1927) (unpublished dissent)

- Sugarman v. United States (1919) (majority)

- United States ex rel Milwaukee Social Democratic Publishing Co. v. Burleson (1921) (dissenting)

- Whitney v. California (1927) (concurring)

- The Collected Supreme Court Opinions of Louis D. Brandeis

- Pennsylvania Coal Co. v. Mahon (1922) (dissenting)

- Loughran v. Loughran (1934) (majority)

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Klebanow, Diana, and Jonas, Franklin L. People's Lawyers: Crusaders for Justice in American History, M.E. Sharpe (2003)

- ^ a b c d e f Vile, John R. Great American Judges: an Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO (2003)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Mason, Thomas A. Brandeis: A Free Man's Life, Viking Press (1946)

- ^ a b c d e Strum, Philippa. Louis D. Brandeis: Justice for the People, Harvard Univ. Press (1984)

- ^ McCraw, Thomas K. Prophets of Regulation, Harvard Univ. Press (1984)

- ^ Jefferson National Expansion Memorial

- ^ a b c d e Lief, Alfred. Brandeis: The Personal History of an American Ideal, Stackpole Sons (1936)

- ^ a b Warren and Brandeis, The Right To Privacy, 4 Harvard Law Review 193 (1890)

- ^ a b Brandeis, Louis. The Regulation of Competition Versus the Regulation of Monopoly, address to the Economic Club of New York on November 1, 1912

- ^ Brandeis, Louis. Opportunity in the Law, address delivered May 4, 1905, before the Harvard Ethical Society

- ^ a b Weller, John L., The New Haven Railroad: its Rise and Fall, Hastings House (1969)

- ^ Brandeis, Louis. The Brandeis Brief, Muller v. Oregon (208 US 412)

- ^ Link, Arthur S. Woodrow Wilson and the Progressive Era, 1910-1917, Harper and Row (1954)

- ^ "Contends Brandeis Is Unfit; Dr Lowell and 54 Bostonians Submit Petition to Senate." The New York Times, February 13, 1916, p. 50; petition submitted by Lowell and "fifty-four citizens of Boston, most of whom are understood to be lawyers," reading in part "An appointment to this court should only be conferred upon a member of the legal profession whose general reputation is as good as his legal attainments are great. We do not believe that Mr. Brandeis has the judicial temperament and capacity which should be required in a Judge of the Supreme Court. His reputation as a lawyer is such that he has not the confidence of the people." Countering this, the Times on May 22 quoted a letter to a senator from Harvard President Emeritus Charles W. Eliot lauding Brandeis as a "a learned jurist" endowed with "altruism and public spirit", and saying that his rejection would be "a grave misfortune for the whole legal profession, the court, all American business, and the country."

- ^ "Confirm Brandeis by Vote of 47 to 22", The New York Times, June 2, 1916.

- ^ "The Best of Times, The Worst of Times", The Jewish Americans. Dir. David Grubin. 2008. DVD. PBS, 2008.

- ^ Jewish Virtual Library, Louis Brandeis.

- ^ Christensen, George A. (1983) Here Lies the Supreme Court: Gravesites of the Justices, Yearbook. Supreme Court Historical Society.

- ^ Louis D. Brandeis memorial at Find a Grave.

Further reading

- Abraham, Henry J. (1992). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1568021267.

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L. (eds.). The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0791013774.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195058356.

{{cite book}}: Check|editor-first=value (help) - Martin, Fenton S. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0871875543.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. p. 590. ISBN 0815311761.

- Melvin I. Urofsky, Louis D. Brandeis: A Life (forthcoming)[2]

See also

- Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of Louisvillians

- List of United States Chief Justices by time in office

- List of U.S. Supreme Court Justices by time in office

- Louis Brandeis House

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Hughes Court

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Taft Court

- United States Supreme Court cases during the White Court

External links

- Fox, John, Capitalism and Conflict, Biographies of the Robes, Louis Dembitz Brandeis. Public Broadcasting System.

- Louis Brandeis at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- Harvard University Library Open Collections Program. Women Working, 1870-1930, Louis Brandeis (1846-1941). A full-text searchable online database with complete access to publications written by Louis Brandeis.

- University of Louisville, Louis D. Brandeis School of Law Library - Louis D. Brandeis Collection

Template:Start U.S. Supreme Court composition Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1916–1921 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition CJ Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1921–1922 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1922 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1923–1925 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1925–1930 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition CJ Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1930 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1930–1932 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1932–1937 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1937–1938 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1938 Template:End U.S. Supreme Court composition