पाटलिपुत्र (talk | contribs) →Description: Restoring valuable description of the topmost wheel. User:Fowler&fowler please edit collaboratively, and stop systematically deleting the contributions of others. No WP:OWN please! Tag: Reverted |

Fowler&fowler (talk | contribs) Restored revision 1099420959 by Fowler&fowler (talk): Take it to the talk page. It i sentirely UNDUE., unmentioned by the majority of modern descriptions |

||

| Line 85: | Line 85: | ||

The capital is {{convert|7|ft|m}} tall in total. Its lowest portion is a bell {{convert|2|ft|cm}} high, carved in the [[Persepolitan]] style, and decorated with 16 petals. Above the bell is a circular [[abacus (architecture)|abacus]], or a drum-shaped slab, of diameter {{convert|34|in|cm}} and height {{convert|13+1/2|in|cm}}. Sitting back to back on the abacus are four lions, each {{convert|3+3/4|ft|m}} tall. Two of these are undamaged. The heads of the other two had come off before excavation and required affixing. Of these, one lion was missing the lower jaw at the time of excavation and the other the upper. On the side of the abacus and below each lion is carved a wheel of 24 spokes in high relief. Between the wheels, also shown in high relief are four animals following each other from right to left. They are a lion, an elephant, a bull, and a horse; the first three are shown at walking pace but the horse is at full gallop.{{sfn|Sahni|1914|p=28}}{{sfn|Oertel|1908|p=69}} |

The capital is {{convert|7|ft|m}} tall in total. Its lowest portion is a bell {{convert|2|ft|cm}} high, carved in the [[Persepolitan]] style, and decorated with 16 petals. Above the bell is a circular [[abacus (architecture)|abacus]], or a drum-shaped slab, of diameter {{convert|34|in|cm}} and height {{convert|13+1/2|in|cm}}. Sitting back to back on the abacus are four lions, each {{convert|3+3/4|ft|m}} tall. Two of these are undamaged. The heads of the other two had come off before excavation and required affixing. Of these, one lion was missing the lower jaw at the time of excavation and the other the upper. On the side of the abacus and below each lion is carved a wheel of 24 spokes in high relief. Between the wheels, also shown in high relief are four animals following each other from right to left. They are a lion, an elephant, a bull, and a horse; the first three are shown at walking pace but the horse is at full gallop.{{sfn|Sahni|1914|p=28}}{{sfn|Oertel|1908|p=69}} |

||

[[File:Ashok Pillar replica in Chiang Mai Thailand (2).jpg|thumb|right|A replica of the Sarnath capital at [[Wat Umong|Wat Umong Suan Puthatham]] in [[Chiang Mai]], Thailand]] |

[[File:Ashok Pillar replica in Chiang Mai Thailand (2).jpg|thumb|right|A replica of the Sarnath capital at [[Wat Umong|Wat Umong Suan Puthatham]] in [[Chiang Mai]], Thailand]] |

||

A larger wheel was placed atop the lions.{{efn|"The pillar was originally crowned by a large chakra, or wheel of truth, some of whose spokes are in the Sarnath Museum.{{sfn|Wriggins|2021|ps=}}}}{{efn|"The famous four lion capital at Sarnath was surmounted by a wheel and stood above a carved abacus depicting the four noble, or cardinal, |

A larger wheel was placed atop the lions.{{efn|"The pillar was originally crowned by a large chakra, or wheel of truth, some of whose spokes are in the Sarnath Museum.{{sfn|Wriggins|2021|ps=}}}}{{efn|"The famous four lion capital at Sarnath was surmounted by a wheel and stood above a carved abacus depicting the four noble, or cardinal, |

||

beasts – the lion, the elephant, the horse and the bull."{{sfn|Coningham|Young|2015|p=444}}}} |

beasts – the lion, the elephant, the horse and the bull."{{sfn|Coningham|Young|2015|p=444}}}} |

||

It was held in place by a shaft. Although the shaft was never found, a hole {{convert|8|in|cm}} across in which it was fitted appears drilled into the unfinished rock between the lions. Four fragments of the rim of this larger wheel were found |

It was held in place by a shaft. Although the shaft was never found, a hole {{convert|8|in|cm}} across in which it was fitted appears drilled into the unfinished rock between the lions. Four fragments of the rim of this larger wheel were found.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Sahni |first1=Dayaram |title=Catalogue of the Museum of Archaeology at Sarnath |date=1914 |page=29 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.gov.ignca.22839/page/28/mode/1up |language=English}}</ref> |

||

According to the art historian of Sarnath, the late Frederick Asher, although the [[Dhamek Stupa]] has been considered the site of the Buddha's first sermon by western scholars, it is the lion capital and its pillar that have come to be replicated in other parts of Asia. Copies of the pillar are found in southeast Asia and East Asia.{{sfn|Asher|2020|p=76}} |

According to the art historian of Sarnath, the late Frederick Asher, although the [[Dhamek Stupa]] has been considered the site of the Buddha's first sermon by western scholars, it is the lion capital and its pillar that have come to be replicated in other parts of Asia. Copies of the pillar are found in southeast Asia and East Asia.{{sfn|Asher|2020|p=76}} |

||

Revision as of 17:57, 20 July 2022

| Lion Capital of Ashoka | |

|---|---|

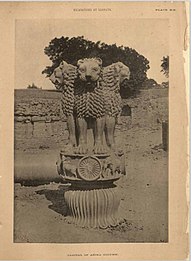

The Lion Capital of Ashoka in Sarnath, showing its four Asiatic lions standing back to back, and symbolizing the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism. The lions stand on a circular abacus along the sides of which the dharmachakra, the Buddhist wheel of the moral law, appears in relief below each lion. Between the chakras, also in relief appear four animals in profile—horse, bull, elephant, and lion—the head of the last being slightly damaged. The architectural bell below the abacus, is a stylized upside down lotus | |

| Material | Sandstone |

| Created | 3rd centuryB CE |

| Discovered | F. O. Oertel (excavator), 1904–1905 |

| Present location | Sarnath Museum, India |

The Lion Capital of Ashoka is the capital of a column excavated by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) in Sarnath, Uttar Pradesh, India. The capital was originally installed ca. 250 BCE by orders of the Mauryan emperor Ashoka atop a column in Sarnath, the site of Gautama Buddha's first sermon. In the sermon, the Buddha taught the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism—suffering, attachment, renunciation, and the right path—which the four lions symbolize.

The excavation of the sculpture was undertaken by F. O. Oertel in the ASI winter season of 1904–1905. The column, which had been damaged before becoming buried, remains in its original location in Sarnath, in several pieces but protected and on view for visitors. The Schism Edict of Ashoka is inscribed on its sides. The Lion Capital, which had remained mostly unscathed and stands 2.15 metres (7.1 ft) tall, and the diameter of the abacus is 0.90 metres (3.0 ft). It is displayed nearby in the Sarnath Museum, the oldest site museum of the ASI.

In July 1947, Jawaharlal Nehru, the interim prime minister of India, and soon-to-be prime minister of the Dominion of India formally proposed in the Constituent Assembly of India that the wheel on the abacus of the Sarnath capital be the model of the national flag of India and the capital itself without the lotus the state emblem of India. The proposal was accepted in December 1947. The capital served as the state seal both of the Dominion of India until 26 January 1950, and with the addition of a national motto below it, of the Republic of India thereafter.

Excavation

Sarnath already had a history of visits and some exploration in the 18th and 19th centuries. William Hodges, the painter had visited it in 1780 and made a record of the Dhamekh Stupa, the most conspicuous monument. In 1794, Jonathan Duncan, the Commissioner of Benares had noted diggings for bricks carried out by Jagat Singh, the Dewan of the Raja of Benares. The location of these were 150 metres (490 ft) to the west of the Damekh.[1]

Colin Mackenzie had visited in 1815 and found sculptures that were donated to the Asiatic Society of Bengal. In 1861, Alexander Cunningham had visited and attempted to dig down into the Dhamekh from its top to uncover relics. He soon abandoned the effort, but not before noting that a large number of votive models of the stupa were scattered everywhere, lending credence to the view that it was the spot where the Buddha had taught his first sermon.[1] The site was pillaged further in 1894 when a large number of bricks were carried off from Sarnath for use as ballast in a railway line being laid nearby.[1]

When F. O. Oertel, an engineer in the Public Works Department, who had surveyed Hindu and Buddhist sites in Burma and Central India in the 1890s[2] was appointed superintending engineer at Varanasi, he constructed a building at Sarnath to house the artefacts found earlier and then paved the road to Sarnath. He then convinced Sir John Marshall, the director-general of the ASI, to be allowed to excavate Sarnath in the winter of 1904–05.[3] At the site, there was no visible trace of the Sarnath column, which had been mentioned in the accounts Xuanzang, a visitor to India from China during the period 629 CE–645 CE. To the west of the main stupa at Sarnath, Oertel at first uncovered the ruins of a Gupta shrine which overlay an Ashokan structure. Further west he found the lowest section of the column, upright but broken off near the base. Most of the remaining column was found in three sections nearby, and as the Sanchi capital had been excavated in 1851, the search for an equivalent was continued, and found close by. It was both finer in execution and better in condition than the one at Sanchi.[4]

Description

In 1904, John Marshall resolved to put in place plans for a museum in Sarnath to keep the excavated artefacts close to the site. [5] The museum, the first site museum of the ASI, was completed in 1910.[5] The lion capital has been displayed in the museum since.[5] Daya Ram Sahni, later to be appointed the first Indian Director-General of the ASI, supervised the organisation and labelling of the museum's collection and in 1914 completed the Catalogue of the Museum of Archaeology at Sarnath".[5]

The capital is 7 feet (2.1 m) tall in total. Its lowest portion is a bell 2 feet (61 cm) high, carved in the Persepolitan style, and decorated with 16 petals. Above the bell is a circular abacus, or a drum-shaped slab, of diameter 34 inches (86 cm) and height 13+1⁄2 inches (34 cm). Sitting back to back on the abacus are four lions, each 3+3⁄4 feet (1.1 m) tall. Two of these are undamaged. The heads of the other two had come off before excavation and required affixing. Of these, one lion was missing the lower jaw at the time of excavation and the other the upper. On the side of the abacus and below each lion is carved a wheel of 24 spokes in high relief. Between the wheels, also shown in high relief are four animals following each other from right to left. They are a lion, an elephant, a bull, and a horse; the first three are shown at walking pace but the horse is at full gallop.[6][7]

A larger wheel was placed atop the lions.[a][b] It was held in place by a shaft. Although the shaft was never found, a hole 8 inches (20 cm) across in which it was fitted appears drilled into the unfinished rock between the lions. Four fragments of the rim of this larger wheel were found.[10]

According to the art historian of Sarnath, the late Frederick Asher, although the Dhamek Stupa has been considered the site of the Buddha's first sermon by western scholars, it is the lion capital and its pillar that have come to be replicated in other parts of Asia. Copies of the pillar are found in southeast Asia and East Asia.[11]

Emblem of postcolonial India

In the days leading to India's independence, the Sarnath capital played an important role in the creation of both the state emblem and the national flag of the Dominion of India.[12][13] They were modelled on the lions and the dharmachakra of the capital, and their adoption constituted an attempt to give India a symbolism of ethical sovereignty.[12][14] On July 22, 1947, Jawaharlal Nehru, the interim prime minister of India, and later the prime minister of the Republic of India proposed formally in the Constituent Assembly of India, which was tasked with creating the Constitution of India:[12]

Resolved that the National Flag of India shall be a horizontal tricolour of deep saffron (kesari), white and dark green in equal proportion. In the centre of the white band, there shall be a Wheel in navy blue to represent the Charkha. The design of the Wheel shall be that of the Wheel (Chakra) which appears on the abacus of the Sarnath Lion Capital of Asoka. The diameter of the Wheel shall approximate to the width of the white band. The ratio of the width to the length of the flag shall ordinarily be 2:3.[12]

Although several members in the assembly had proposed other meanings for India's national symbols, Nehru's meaning came to prevail. [12] On December 11, 1947, the Constituent Assembly adopted the resolution.[12] Nehru was well-acquainted with the history of Ashoka, having written about it in his books Letters from a father to his daughter and The Discovery of India.[12] The major contemporary philosopher of the religions of India, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, also advised Nehru in the choice.[12] The state emblem of the Dominion of India was accepted by the cabinet on December 29, 1947 with the resolution of a national motto set aside for a future date.[15]

Influences

Currently seven animal sculptures from Ashoka pillars survive.[16][17] These form "the first important group of Indian stone sculpture", though it is thought they derive from an existing tradition of wooden columns topped by animal sculptures in copper, none of which have survived. There has been much discussion of the extent of influence from Achaemenid Persia, where the column capitals supporting the roofs at Persepolis have similarities, and the "rather cold, hieratic style" of the Sarnath sculptures especially shows "obvious Achaemenid and Sargonid influence".[18][19]

Notes

- ^ "The pillar was originally crowned by a large chakra, or wheel of truth, some of whose spokes are in the Sarnath Museum.[8]

- ^ "The famous four lion capital at Sarnath was surmounted by a wheel and stood above a carved abacus depicting the four noble, or cardinal, beasts – the lion, the elephant, the horse and the bull."[9]

References

- ^ a b c Ray 2014, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Giuha 2010, p. 39.

- ^ Asher 2020, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Allen, Chapter 15

- ^ a b c d Asher 2020, p. 35.

- ^ Sahni 1914, p. 28. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSahni1914 (help)

- ^ Oertel 1908, p. 69.

- ^ Wriggins 2021

- ^ Coningham & Young 2015, p. 444.

- ^ Sahni, Dayaram (1914). Catalogue of the Museum of Archaeology at Sarnath. p. 29.

- ^ Asher 2020, p. 76.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Vajpeyi, Ananya (31 October 2012), Righteous Republic: The Political Foundations of Modern India, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: Harvard University Press, pp. 188–189, ISBN 978-0-674-04895-9

- ^ Coningham, Robin; Ruth, Young (2015), Archaeology of South Asia: From Indus to Asoka, c. 6500 BCE–200 CE, Cambridge World Archaeology Series, New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 465, ISBN 978-0-521-84697-4

- ^ Asif 2020, p. 31.

- ^ Ministry of Home Affairs (29 December 1947), Press Communique (PDF), Press Information Bureau, Government of India

- ^ Himanshu Prabha Ray (7 August 2014). The Return of the Buddha: Ancient Symbols for a New Nation. Routledge. p. 123. ISBN 9781317560067.

- ^ Rebecca M. Brown, Deborah S. Hutton. A Companion to Asian Art and Architecture. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 423–429.

- ^ Harle, 22, 24, quoted in turn; Companion, 429-430

- ^ Kleiner, Fred S. (1 January 2015). Gardner's Art through the Ages: A Global History. Cengage Learning. p. 441. ISBN 978-1-305-54484-0.

Cited works

- Asher, Frederick M. (2020), Sarnath: A critical history of the place where Buddhism began, Los Angeles, California: Getty Research Institute, pp. 2–3, ISBN 9781606066164, LCCN 2019019885

- Asher, Frederick (2011), "On Mauryan Art", in Brown, Rebecca M.; Hutton, Deborah S. (eds.), A Companion to Asian Art and Architecture, Wiley-Blackwell Companions to Art History, Southern Gate, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 421–444, ISBN 9781444396355

- Asif, Manan Ahmed (2020), The Loss of Hindustan: The Invention of India, Cambridge, Massachusette and London, England: Harvard University Press, p. 31, ISBN 9780674249868

- Coningham, Robin; Young, Ruth (2015), Archaeology of South Asia: From Indus to Asoka, c. 6500 BCE–200 CE, Cambridge World Archaeology Series, New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 465, ISBN 978-0-521-84697-4

- Fogelin, Lars (2015), An Archaeological History of Indian Buddhism, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-1999-4821-5

- Guha, Sudeshna (2010), "Introduction: Archaeology, Photography, Histories", in Guha, Sudeshna (ed.), The Marshall Albums: Photography and Archaeology, Preface by B. D. Chattopadhyaya; Contributors: Sudeshna Guha, Michael S. Dodson, Tapati Guha-Thakurta, Christopher Pinney, Robert Harding, London and New Delhi: The Alkazi Collection of Photography in association with Mapin Publishing, and support of Archaeological Survey of India, p. 39, ISBN 978-81-89995-32-4

- Oertel, F. O. (1908), "Excavations at Sarnath", Archaeological Survey of India: Annual Report 1904–1905, Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing, India, pp. 59–104

- Ray, Himanshu Prabha (2014), The Return of the Buddha: Ancient Symbols for a New Nation, London, New York, and New Delhi: Routledge, pp. 78–79, ISBN 978-0-415-71115-9

- Sahni, Daya Ram (1914), Catalogue of the Museum of Archaeology at Sarnath, With an introduction by J. Ph. Vogel, Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing, India, pp. 28–31

- Vajpeyi, Ananya (31 October 2012), Righteous Republic: The Political Foundations of Modern India, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: Harvard University Press, pp. 188–189, ISBN 978-0-674-04895-9

- Wriggins, Sally Hovey (2021) [1996], Xuanzang: A Buddhist Pilgrim on the Silk Road, with a foreword by Frederick W. Motes, London and New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-3672-1386-2

Further reading

- Allen, Charles, Ashoka: The Search for India's Lost Emperor, 2012, Hachette UK, ISBN 1408703882, 9781408703885, google books

- "Companion": Brown, Rebecca M., Hutton, Deborah S., eds., A Companion to Asian Art and Architecture, Volume 3 of Blackwell companions to art history, 2011, John Wiley & Sons, 2011, ISBN 1444396323, 9781444396324, google books

- Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300062176

External links

- Blog with excellent photos

- For Pictures of the famous original "Lion Capital of Ashoka" preserved at the Sarnath Museum which has been adopted as the "National Emblem of India" and the Ashoka Chakra (Wheel) from which has been placed in the center of the "National Flag of India" - See "lioncapital" from Columbia University Website, New York, USA

- National symbols of India