JPollock412 (talk | contribs) m →Prelude: removed the word 'but' from sentence 'But two others...' To fix grammar issue caused by my last edit. |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Americans taken hostage in Iran}} |

|||

{{Cleanup|reason=For an article of relative importance this needs much work. It has improper footnotes, bad grammar, unsupported conclusions and typos|date=March 2013}} |

|||

{{ |

{{About|the siege of the American embassy in Tehran|the siege of the Iranian embassy in London|Iranian Embassy siege}} |

||

{{Use mdy dates|date=March 2013}} |

{{Use mdy dates|date=March 2013}} |

||

{{Infobox military conflict |

{{Infobox military conflict |

||

|conflict= |

| conflict = Iranian hostage crisis |

||

|date= November 4, 1979 – January 20, 1981<br>( |

| date = November 4, 1979 – January 20, 1981<br />(444 days) |

||

|partof=[[ |

| partof = the [[consolidation of the Iranian Revolution]] |

||

| image = Iran hostage crisis - Iraninan students comes up U.S. embassy in Tehran.jpg |

|||

|image=[[File:US Embassy Tehran.JPG|300px]] |

|||

| image_size = 300px |

|||

|caption=A defaced [[Great Seal of the United States]] at the former U.S. embassy, Tehran, Iran, as it appeared in 2004 |

|||

| caption = Iranian students crowd the [[Embassy of the United States, Tehran|U.S. Embassy in Tehran]] (November 4, 1979) |

|||

|place=[[Tehran]], Iran |

|||

| place = [[Tehran]], Iran |

|||

|result= Rupture of [[Iran–United States relations]] |

|||

| result = Hostages released by [[Algiers Accords]] |

|||

|territory= |

|||

* Severance (and end) of [[Iran–United States relations]] |

|||

|combatant1={{flag|Iran}} |

|||

* Prime Minister [[Mehdi Bazargan]] and [[Interim Government of Iran|his cabinet]] resigned |

|||

*[[Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line]] |

|||

* [[Sanctions against Iran|Sanctions imposed on Iran]] |

|||

|combatant2={{flag|United States}}<br />{{flag|Canada}} |

|||

| territory = |

|||

|commander1={{flagicon|Iran}} [[Ayatollah]] [[Ruhollah Khomeini]] |

|||

| combatant1 = {{flag|Iran}} |

|||

|commander2={{flagicon|United States}} [[Jimmy Carter]] |

|||

* [[Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line]] |

|||

{{flagicon|United States}} [[Ronald Reagan]]<br /> |

|||

* {{flagicon image|Flag of the People's Mujahedin of Iran.svg}} [[People's Mujahedin of Iran|People's Mujahedin]]<ref>{{cite book|title=Microeconomics|editor=David Gold|pages=66–67|isbn=978-1-317-04590-8|publisher=Routledge|year=2016|chapter=An Analysis of the Role of the Iranian Diaspora in the Financial Support System of the ''Mujaheddin-e-Khalid''|last=Clark |first=Mark Edmond |quote=Following the seizure of the US embassy in Tehran, the MEK participated physically at the site by assisting in defending it from attack. The MEK also offered strong political support for the hostage-taking action.}}</ref> |

|||

{{flagicon|United States}} [[George H. W. Bush]] |

|||

| combatant2 = {{ubl|{{flag|United States}}|{{flag|Canada}}}} |

|||

|strength1= |

|||

| commander1 = {{ubl|{{flagicon|Iran}} [[Ruhollah Khomeini]]|{{flagicon|Iran}} [[Mohammad Mousavi Khoeiniha]]<ref>{{cite book |author=Buchan, James |title=Days of God: The Revolution in Iran and Its Consequences|publisher=Simon and Schuster|page=257|date=2013|isbn=978-1-4165-9777-3}}</ref>|{{flagicon image|Flag of the People's Mujahedin of Iran.svg}} [[Massoud Rajavi]]}} |

|||

|casualties2=destruction of two aircraft (accident)<br/> |

|||

| commander2 = {{ubl|{{flagicon|United States}} [[Jimmy Carter]]|{{ubl|{{flagicon|United States}} [[Ronald Reagan]]|{{flagicon|United States}} [[James B. Vaught]]|{{flagicon|Canada}} [[Joe Clark]]}} |

|||

Eight American servicemen and one Iranian civilian killed |

|||

| strength1 = |

|||

|campaignbox= |

|||

| casualties1 = 8 American servicemen and 1 Iranian civilian killed during an [[Operation Eagle Claw|attempt to rescue the hostages]]. |

|||

{{Campaignbox Iran Hostage Crisis}} |

|||

{{Campaignbox consolidation of the Iranian Revolution}} |

| campaignbox = {{Campaignbox consolidation of the Iranian Revolution}} |

||

{{History of Iranian hostage crisis}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}}}} |

|||

The '''Iran hostage crisis''', referred to in [[Persian language|Persian]] as تسخیر لانه جاسوسی امریکا (literally "Conquest of the American Spy Den," but usually translated as "Occupation of the American Embassy"{{Citation needed|date=March 2013}}), was a diplomatic crisis between [[Iran]] and the United States. Fifty-two Americans were held hostage for 444 days (November 4, 1979 to January 20, 1981), after a group of [[Islamism|Islamist]] students and militants supporting the [[Iranian Revolution]] took over [[Embassy of the United States, Tehran|the American Embassy in Tehran]].<ref>[http://www.historyguy.com/iran-us_hostage_crisis.html Iran–U.S. Hostage Crisis (1979–1981)]</ref> President [[Jimmy Carter|Carter]] called the hostages "victims of terrorism and anarchy," adding that "the United States will not yield to [[blackmail]]."<ref name=Carter1>[http://www.airforce-magazine.com/MagazineArchive/Documents/2010/April%202010/0410fullkeeper.pdf State of the Union Address by President Carter], January 23, 1980</ref> |

|||

The '''Iranian hostage crisis''' was a diplomatic standoff between [[Iran]] and the [[United States]]. Fifty-three American diplomats and citizens were held hostage in Iran after a group of armed Iranian college students belonging to the [[Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line]], who supported the [[Iranian Revolution]], including [[Hossein Dehghan]] (future Iranian Minister of Defense), [[Mohammad Ali Jafari]] (future [[IRGC|Revolutionary Guards]] Commander-In-Chief) and [[Mohammad Bagheri (Iranian commander)|Mohammad Bagheri]] (future Chief of the General Staff of the [[Iranian Army]]),<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://iranwire.com/en/features/65968/|title=The Bagheri Brothers: One in Operations, One in Intelligence|accessdate=March 11, 2024}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.iranintl.com/en/20211105051120 | title=What Became of Those Who Seized the US Embassy in Tehran | date=March 9, 2024 }}</ref> took over the [[Embassy of the United States, Tehran|U.S. Embassy]] in [[Tehran]]<ref>{{cite web|author=Penn, Nate|date=November 3, 2009|title=444 Days in the Dark: An Oral History of the Iran Hostage Crisis|url=https://www.gq.com/story/iran-hostage-crisis-tehran-embassy-oral-history|access-date=January 6, 2020|magazine=[[GQ]]|archive-date=May 5, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210505094637/https://www.gq.com/story/iran-hostage-crisis-tehran-embassy-oral-history|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|author=Sahimi, Muhammad|date=November 3, 2009|title=The Hostage Crisis, 30 Years On|url=https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/tehranbureau/2009/11/30-years-after-the-hostage-crisis.html|access-date=January 6, 2020|work=[[Frontline (American TV program)|Frontline]]|publisher=[[PBS]]|archive-date=April 10, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210410094257/https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/tehranbureau/2009/11/30-years-after-the-hostage-crisis.html|url-status=live}}</ref> and took them as hostages. The hostages were held for 444 days, from November 4, 1979 to their release on January 20, 1981. The crisis is considered a pivotal episode in the history of [[Iran–United States relations]].<ref>{{cite magazine |url=http://www.smithsonianmag.com/people-places/iran-fury.html |archive-url=https://wayback.archive-it.org/all/20130419175811/http://www.smithsonianmag.com/people-places/iran-fury.html |archive-date=April 19, 2013 |first=Stephen |last=Kinzer |date=October 2008 |title=Inside Iran's Fury |magazine=Smithsonian Magazine |access-date=May 5, 2016 }}</ref> |

|||

The crisis has been described as an entanglement of "vengeance and mutual incomprehension."<ref name="TIMEordeal">[http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,954605-3,00.html The Long Ordeal of the Hostages By HP-Time.com;John Skow, January 26, 1981]</ref> In Iran, the hostage taking was widely seen as a blow against the United States and its influence in Iran, its perceived attempts to undermine the Iranian Revolution, and its longstanding support of the recently overthrown Shah [[Mohammad Reza Pahlavi]] of Iran. Following his overthrow, the Shah was allowed into the US for medical treatment. In the United States, the hostage-taking was seen as an outrage violating a centuries-old principle of international law granting [[diplomatic immunity|diplomats immunity from arrest]] and diplomatic compounds' [[Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations|inviolability]].<ref>name="ReferenceA">"Doing Satan's Work in Iran", ''New York Times'', November 6, 1979.</ref><ref>Kinzer, Stephen. (2003). All The Shah's Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. |

|||

Nalle, David. (2003). All the Shah's Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror. Middle East Policy, Vol. X (4), 148-155. |

|||

Pryce-Jones, David. (2003). A Very Elegant Coup. National Review, 55 (17), 48-50.</ref> |

|||

Western media described the crisis as an "entanglement" of "vengeance and mutual incomprehension".<ref name="TIME_1981-01-26">{{cite magazine |title=The Long Ordeal of the Hostages |last=Skow |first=John |magazine=[[Time (magazine)|Time]] |date=January 26, 1981 |access-date=May 27, 2015 |url=http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,954605,00.html}}</ref> [[U.S. President]] [[Jimmy Carter]] called the hostage-taking an act of "blackmail" and the hostages "victims of terrorism and anarchy".<ref name=Carter1>{{cite web |url=http://www.airforce-magazine.com/MagazineArchive/Documents/2010/April%202010/0410fullkeeper.pdf |title=Air Force Magazine |publisher=Air Force Magazine |date=April 5, 2016 |access-date=May 5, 2016 |archive-date=November 27, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121127221703/http://www.airforce-magazine.com/MagazineArchive/Documents/2010/April%202010/0410fullkeeper.pdf }}</ref> In Iran, it was widely seen as an act against the U.S. and its influence in Iran, including its perceived attempts to undermine the Iranian Revolution and its [[1953 Iranian coup d'état|long-standing support]] of the Shah of Iran, [[Mohammad Reza Pahlavi]], who was overthrown in 1979.<ref name="BG">{{cite web|last1=Kinzer|first1=Stephen|title=Thirty-five years after Iranian hostage crisis, the aftershocks remain|work=The Boston Globe|url=https://www.bostonglobe.com/opinion/2014/11/04/thirty-five-years-after-iranian-hostage-crisis-aftershocks-remain/VIEKSajEUvSmDQICGF8R7K/story.html|access-date=April 15, 2018|archive-date=April 16, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180416073434/https://www.bostonglobe.com/opinion/2014/11/04/thirty-five-years-after-iranian-hostage-crisis-aftershocks-remain/VIEKSajEUvSmDQICGF8R7K/story.html|url-status=live}}</ref> After Shah Pahlavi was overthrown, he was granted asylum and admitted to the U.S. for cancer treatment. The new Iranian regime demanded his return in order to stand trial for the crimes he was accused of committing against Iranians during his rule through [[SAVAK|his secret police]]. These demands were rejected, which Iran saw as U.S. complicity in those abuses. The U.S. saw the hostage-taking as an egregious violation of the principles of international law, such as the [[Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations|Vienna Convention]], which granted [[diplomatic immunity|diplomats immunity from arrest]] and made diplomatic compounds inviolable.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1979/11/06/111115000.pdf|title=Doing Satan's Work in Iran|date=November 6, 1979|access-date=January 4, 2016|work=The New York Times|archive-date=February 1, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220201125040/https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1979/11/06/111115000.html?pdf_redirect=true&site=false|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>Kinzer, Stephen (2003). ''All The Shah's Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror''. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Nalle |first=David |year=2003 |title=All the Shah's Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror |journal=Middle East Policy |volume=10 |issue=4 |pages=148–155}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Pryce-Jones |first=David |year=2003 |title=A Very Elegant Coup |journal=National Review |volume=55 |issue=17 |pages=48–50}}</ref> The Shah left the U.S. in December 1979 and was ultimately granted asylum in [[Egypt]], where he died from complications of cancer at age 60 on July 27, 1980. |

|||

The episode reached a climax when, after failed attempts to negotiate a release, the United States military attempted a rescue operation off the [[USS Nimitz (CVN-68)|USS ''Nimitz'']]. On April 24, 1980, [[Operation Eagle Claw]] resulted in a failed mission, the deaths of eight American servicemen, one Iranian civilian, and the destruction of two aircraft. |

|||

Six American diplomats who had evaded capture were rescued by a [[Canadian Caper#Rescue|joint CIA–Canadian effort]] on January 27, 1980. The crisis reached a climax in early 1980 after [[Iran hostage crisis negotiations|diplomatic negotiations]] failed to win the release of the hostages. Carter ordered the U.S. military to attempt a rescue mission – [[Operation Eagle Claw]] – using warships that included {{USS|Nimitz|CVN-68|6}} and {{USS|Coral Sea|CV-43|6}}, which were patrolling the waters near Iran. The failed attempt on April 24, 1980, resulted in the death of one Iranian civilian and the accidental deaths of eight American servicemen after one of the helicopters crashed into a transport aircraft. U.S. Secretary of State [[Cyrus Vance]] resigned his position following the failure. In September 1980, [[Ba'athist Iraq|Iraq]] invaded Iran, beginning the [[Iran–Iraq War]]. These events led the Iranian government to enter negotiations with the U.S., with [[Algeria]] acting as a mediator. |

|||

On July 27, 1980, the former Shah died; then, in September, [[Iran-Iraq War|Iraq invaded Iran]]. These two events led the Iranian government to enter negotiations with the U.S., with [[Algeria]] acting as a mediator. The hostages were formally released into United States custody the day after the signing of the [[Algiers Accords]], just minutes after the new American president [[Ronald Reagan]] was [[First inauguration of Ronald Reagan|sworn into office]]. |

|||

Political analysts cited the standoff as a major factor in the continuing downfall of [[Carter's presidency]] and his landslide loss in the [[1980 United States presidential election|1980 presidential election]].<ref>[http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2001/01/19/iran/main265499.shtml "Reagan's Lucky Day: Iranian Hostage Crisis Helped The Great Communicator To Victory"]. ''[[CBS News]]''. January 21, 2001. {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130515223652/http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2001/01/19/iran/main265499.shtml |date=May 15, 2013 }}.</ref> The hostages were formally released into United States custody the day after the signing of the [[Algiers Accords]], just minutes after American President [[Ronald Reagan]] was [[First inauguration of Ronald Reagan|sworn into office]]. In Iran, the crisis strengthened the prestige of [[Ayatollah]] [[Ruhollah Khomeini]] and the political power of [[theocrats]] who opposed any normalization of relations with the West.<ref>Mackey, Sandra (1996). ''The Iranians: Persia, Islam and the Soul of a Nation''. New York: Dutton. p. 298. {{ISBN|9780525940050}}</ref> The crisis also led to American economic [[sanctions against Iran]], which further weakened ties between the two countries.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.mafhoum.com/press3/108E16.htm |title=A Review Of US Unilateral Sanctions Against Iran |website=Mafhoum |date=August 26, 2002 |access-date=May 5, 2016 |archive-date=October 10, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171010024317/http://www.mafhoum.com/press3/108E16.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

==Background== |

==Background== |

||

===1953 coup d'état=== |

|||

{{Further|Operation Ajax|Iranian Revolution}} |

|||

During the [[Second World War]], the [[Government of the United Kingdom|British]] and the [[Soviet government]]s [[Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran|invaded and occupied Iran]], forcing the first Pahlavi monarch, [[Reza Shah Pahlavi]] to abdicate in favor of his eldest son, [[Mohammad Reza Pahlavi]].<ref>Abrahamian, ''Iran Between Two Revolutions'', (1982), p. 164</ref> The two nations claimed that they acted preemptively in order to stop Reza Shah from aligning his petroleum-rich country with [[Nazi Germany]]. However, the Shah's declaration of neutrality, and his refusal to allow Iranian territory to be used to train or supply [[Red Army|Soviet troops]], were probably the real reasons for the invasion of Iran.<ref>{{cite web |title=Country name calling: the case of Iran vs. Persia. |url=http://goliath.ecnext.com/coms2/gi_0199-6583215/Country-name-calling-the-case.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080213175117/http://goliath.ecnext.com/coms2/gi_0199-6583215/Country-name-calling-the-case.html |archive-date=February 13, 2008 |access-date=May 2, 2013}}</ref> |

|||

The United States did not participate in the invasion but it secured Iran's independence after the war ended by applying intense diplomatic [[Iran crisis of 1946|pressure on the Soviet Union which forced it to withdraw from Iran in 1946]]. |

|||

===1953 coup=== |

|||

{{further|Operation Ajax|Iranian Revolution}} |

|||

In February 1979, less than a year before the hostage crisis, [[Mohammad Reza Pahlavi]], the [[Shah of Iran]], had been overthrown in a revolution. For several decades prior to his deposition, the United States had [[United States–Iran relations|allied with and supported]] the Shah. During [[World War II]], [[Allies of World War II|Allied]] powers Britain and the [[Soviet Union]] occupied Iran and required [[Reza Shah]], the existing Shah of Iran, to abdicate in favor of his son, [[Mohammad Reza Pahlavi]].<ref>Abrahamian, ''Iran Between Two Revolutions'', (1982), p. 164</ref> The Allies feared that [[Reza Shah]] intended to align his petroleum-rich country with [[Nazi Germany]] during the war; however, Reza Shah's earlier Declaration of Neutrality and refusal to allow Iranian territory to be used to train, supply, and act as a transport corridor to ship arms to the [[Soviet Union]] for its war effort against Germany, was the strongest motive for the allied invasion of Iran. Because of its importance in the allied victory, Iran was subsequently called ''"The Bridge of Victory"'' by Winston Churchill.<ref>{{cite web |title=Country name calling: the case of Iran vs. Persia. |url=http://goliath.ecnext.com/coms2/gi_0199-6583215/Country-name-calling-the-case.html}} retrieved May 4, 2008</ref> |

|||

By the 1950s, |

By the 1950s, [[Mohammad Reza Pahlavi]] was engaged in a power struggle with Iran's prime minister, [[Mohammad Mosaddegh]], an immediate descendant of the preceding [[Qajar dynasty]]. Mosaddegh led a general strike, demanding an increased share of the nation's petroleum revenue from the [[Anglo-Iranian Oil Company]] which was operating in Iran. The UK retaliated by reducing the amount of revenue which the Iranian government received.<ref>{{cite book|pages=52, 54, 63 |title=The Persian Puzzle|author=Pollack, Kenneth M. |place=New York|publisher= Random House|year= 2004|isbn=978-1-4000-6315-4}}</ref>{{better source needed|date=February 2014}} In 1953, the [[CIA]] and [[MI6]] helped Iranian royalists depose Mosaddegh in a military ''[[coup d'état]]'' codenamed [[Operation Ajax]], allowing the Shah to extend his power. For the next two decades the Shah reigned as an [[absolute monarch]]. "Disloyal" elements within the state were purged.<ref>{{cite book |last=O'Reilly |first=Kevin |title=Decision Making in U.S. History. The Cold War & the 1950s |publisher=Social Studies |year=2007 |page=108 |isbn=978-1-56004-293-8 }}</ref><ref>Amjad, Mohammed (1989). ''Iran: From Royal Dictatorship to Theocracy''. [[Greenwood Press]]. {{ISBN|9780313264412}}. p. 62: "the United States had decided to save the 'free world' by overthrowing the democratically elected government of Mosaddegh."</ref><ref>{{cite book | last1=Burke | first1=Andrew | last2=Elliott | first2=Mark | publisher=Lonely Planet Publications | title=Iran | publication-place=Footscray, Vic. | date=2008 | isbn=978-1-74104-293-1 | oclc=271774061 | page=37}}</ref> The U.S. continued to support the Shah after the coup, with the CIA training the [[SAVAK|Iranian secret police]]. In the subsequent decades of the [[Cold War]], various economic, cultural, and political issues united Iranian opposition against the Shah and led to his eventual overthrow.<ref name = "bbc">{{cite news |title=Iran's century of upheaval |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/618649.stm |publisher=BBC |access-date=January 5, 2007 |date=February 2, 2000 |archive-date=May 8, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210508151519/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/618649.stm |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name = "bbc2">{{cite news |title=1979: Shah of Iran flees into exile |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/january/16/newsid_2530000/2530475.stm |publisher=BBC |access-date=January 5, 2007 |date=January 16, 1979 |archive-date=October 29, 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091029071947/http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/january/16/newsid_2530000/2530475.stm |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name = "cnn">{{cite news |title=January 16 Almanac |url=http://www.cnn.com/almanac/9801/16/ |publisher=CNN |access-date=January 5, 2007 |archive-date=November 26, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201126024118/http://www.cnn.com/almanac/9801/16/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

}}</ref><ref name = "bbc2">{{cite news |title=1979: Shah of Iran flees into exile |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/january/16/newsid_2530000/2530475.stm |publisher=BBC |accessdate=2007-01-05 | date=January 16, 1979 |

|||

}}</ref><ref name = "cnn">{{cite news |title=January 16 Almanac |url=http://www.cnn.com/almanac/9801/16/ |publisher=CNN |accessdate=2007-01-05poop |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

===Carter administration=== |

===Carter administration=== |

||

Months before the |

Months before the [[Iranian Revolution]], on New Year's Eve 1977, U.S. President [[Jimmy Carter]] further angered anti-Shah Iranians with a televised toast to Pahlavi, claiming that the Shah was "beloved" by his people. After the revolution commenced in February 1979 with the return of the Ayatollah [[Ruhollah Khomeini|Khomeini]], the American Embassy was occupied, and its staff held hostage briefly. Rocks and bullets had broken so many of the embassy's front-facing windows that they were replaced with [[bulletproof glass]]. The embassy's staff was reduced to just over 60 from a high of nearly one thousand earlier in the decade.<ref name="Bowden 2006, p. 19">[[#Bowden|Bowden]], p. 19</ref> |

||

[[File:Shah Farah Leave.jpg|thumb|Iran attempted to use the occupation to provide leverage in its demand for the return of the shah to stand trial in Iran]] |

|||

The [[Carter administration]] tried to mitigate anti-American feeling by promoting a new relationship with the ''de facto'' Iranian government and continuing military cooperation in hopes that the situation would stabilize. However, on October 22, 1979, the United States permitted the Shah, who had [[lymphoma]], to enter [[New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center]] for medical treatment.<ref>{{cite news|last=Daniels|first=Lee A.|date=October 24, 1979|title=Medical tests in Manhattan|newspaper=The New York Times|page=A1|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1979/10/24/archives/medical-tests-in-manhattan-jaundice-in-patient-reported.html|access-date=July 22, 2018|archive-date=March 7, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210307222436/http://www.nytimes.com/1979/10/24/archives/medical-tests-in-manhattan-jaundice-in-patient-reported.html|url-status=live}}<br />{{cite news|last=Altman|first=Lawrence K.|date=October 24, 1979|title=Jaundice in patient reported|newspaper=The New York Times|page=A1|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1979/10/24/archives/medical-tests-in-manhattan-jaundice-in-patient-reported.html|access-date=July 22, 2018|archive-date=March 7, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210307222436/http://www.nytimes.com/1979/10/24/archives/medical-tests-in-manhattan-jaundice-in-patient-reported.html|url-status=live}}<br />{{cite news|last=Altman|first=Lawrence K.|date=October 25, 1979|title=Shah's surgeons unblock bile duct and also remove his gallbladder|newspaper=The New York Times|page=A1|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1979/10/25/archives/shahs-surgeons-unblock-bile-duct-and-also-remove-his-gallbladder.html|access-date=July 22, 2018|archive-date=July 22, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180722220939/https://www.nytimes.com/1979/10/25/archives/shahs-surgeons-unblock-bile-duct-and-also-remove-his-gallbladder.html|url-status=live}}</ref> The State Department had discouraged this decision, understanding the political delicacy.<ref name="Bowden 2006, p. 19"/> But in response to pressure from influential figures including former [[United States Secretary of State|Secretary of State]] [[Henry Kissinger]] and [[Council on Foreign Relations]] Chairman [[David Rockefeller]], the Carter administration decided to grant it.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.unc.edu/depts/diplomat/archives_roll/2003_01-03/dauherty_shah/dauherty_shah.html |title=Daugherty | Jimmy Carter and the 1979 Decision to Admit the Shah into the United States |website=Unc.edu |access-date=May 5, 2016 |archive-date=October 4, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111004121457/http://www.unc.edu/depts/diplomat/archives_roll/2003_01-03/dauherty_shah/dauherty_shah.html }}</ref><ref name="David Farber">[[#Farber|Farber]], p. 122</ref><ref>{{cite interview |url=http://www.roozonline.com/english/archives/2007/06/005063.php |title=Weak Understanding is Cause of Bad Iran Policies |first=Ebrahim|last=Yazdi |work=[[Rooz]] |access-date=February 8, 2016 |url-status=usurped |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080610193827/http://www.roozonline.com/english/archives/2007/06/005063.php |archive-date=June 10, 2008 }}</ref><ref>Kirkpatrick, David D. (December 29, 2019) [https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/29/world/middleeast/shah-iran-chase-papers.html How a Chase Bank Chairman Helped] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191229165639/https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/29/world/middleeast/shah-iran-chase-papers.html |date=December 29, 2019 }}. ''New York Times''. The activities of the Chase Manhattan Bank triggered the whole hostages crisis.</ref> |

|||

The Shah's admission to the United States intensified Iranian revolutionaries' anti-Americanism and spawned rumors of another U.S.–backed coup that would re-install him.<ref name="multiref1">{{cite web |url=http://www.democracynow.org/2008/3/3/stephen_kinzer_on_the_us_iranian |title=Stephen Kinzer on US-Iranian Relations, the 1953 CIA Coup in Iran and the Roots of Middle East Terror |publisher=Democracy Now! |date=March 3, 2008 |access-date=May 5, 2016 |archive-date=February 15, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220215014229/https://www.democracynow.org/2008/3/3/stephen_kinzer_on_the_us_iranian |url-status=live }}</ref> Khomeini, who had been exiled by the shah for 15 years, heightened the rhetoric against the "[[Great Satan]]", as he called the U.S, talking of "evidence of American plotting."<ref>[[#Moin|Moin]], p. 220</ref> In addition to ending what they believed was American sabotage of the revolution, the hostage takers hoped to depose the [[The Interim Government of Iran|provisional revolutionary government]] of Prime Minister [[Mehdi Bazargan]], which they believed was plotting to normalize relations with the U.S. and extinguish Islamic revolutionary order in Iran.<ref>[[#Bowden|Bowden]], p. 10</ref> The occupation of the embassy on November 4, 1979, was also intended as leverage to demand the return of the Shah to stand trial in Iran in exchange for the hostages. |

|||

The Carter administration attempted to mitigate the anti-American feeling by finding a new relationship with the ''de facto'' Iranian government and by continuing military cooperation in hopes that the situation would stabilize. However, on October 22, 1979, the United States permitted the Shah—who was ill with [[gallstone]]s—to enter [[NewYork–Presbyterian Hospital|New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center]] for medical treatment.<ref>{{cite news|last=Daniels|first=Lee A.|date=October 24, 1979|title=Medical tests in Manhattan|newspaper=The New York Times|page=A1|url=http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F1071FFD3F5410728DDDAD0A94D8415B898BF1D3}}<br/>{{cite news|last=Altman|first=Lawrence K.|date=October 24, 1979|title=Jaundice in patient reported|newspaper=The New York Times|page=A1|url=http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F1071FFD3F5410728DDDAD0A94D8415B898BF1D3}}<br/>{{cite news|last=Altman|first=Lawrence K.|date=October 25, 1979|title=Shah's surgeons unblock bile duct and also remove his gallbladder|newspaper=The New York Times|page=A1|url=http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F40F12FE3C5C12728DDDAC0A94D8415B898BF1D3}}</ref> The State Department had discouraged the request, understanding the political delicacy,<ref>Bowden, ''Guests of the Ayatollah'', (2006), p. 19</ref> but after pressure from influential figures including former [[United States Secretary of State]] [[Henry Kissinger]] and [[Council on Foreign Relations]] chairman [[David Rockefeller]], the Carter administration decided to grant the Shah's request.<ref>[http://www.unc.edu/depts/diplomat/archives_roll/2003_01-03/dauherty_shah/dauherty_shah.html Daugherty Jimmy Carter and the 1979 Decision to Admit the Shah into the United States<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref><ref name="David Farber">[http://books.google.com/books?id=wOc-SCVsfJAC&pg=PA122&lpg=PA122&dq=us+hostage+crisis+chase+manhattan&source=web&ots=XNzMh-F0Ev&sig=T8rxK2qMhpUpyVQfbEcRSWF-DuA David Farber]</ref><ref>[http://www.roozonline.com/english/archives/2007/06/005063.php ''Rooz'': Weak Understanding is Cause of Bad Iran Policies]</ref> |

|||

A later study claimed that there had been no American plots to overthrow the revolutionaries, and that a CIA intelligence-gathering mission at the embassy had been "notably ineffectual, gathering little information and hampered by the fact that none of the three officers spoke the local language, [[Persian language|Persian]]." Its work, the study said, was "routine, prudent espionage conducted at diplomatic missions everywhere."<ref name="Journal">{{cite web|url=http://www.homelandsecurity.org/newjournal/BookReviews/displayBookReview2.asp?review=63 |archive-url=https://archive.today/20101124132652/http://www.homelandsecurity.org/newjournal/BookReviews/displayBookReview2.asp?review=63 |archive-date=November 24, 2010 |title=Journal of Homeland Security review of Mark Bowden's "Guests of the Ayatollah" |access-date=February 25, 2007 }}</ref> |

|||

The Shah's admission to the United States intensified Iranian revolutionaries' anti-Americanism and spawned rumors of another U.S.-backed coup and re-installation of the Shah.<ref name="multiref1">Democracy Now, March 3, 2008, [http://www.democracynow.org/2008/3/3/stephen_kinzer_on_the_us_iranian Stephen Kinzer on US–Iranian Relations, the 1953 CIA Coup in Iran and the Roots of Middle East Terror]</ref> |

|||

==Prelude== |

|||

Revolutionary leader [[Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini]]—who had been exiled by the Shah for 15 years—heightened rhetoric against the "[[Great Satan]]", the United States, talking of what he called "evidence of American plotting".<ref>Moin ''Khomeini,'' (2000), p. 220</ref> In addition to putting an end to what they believed was American plotting and sabotage against the revolution, the hostage takers hoped to depose the [[The Interim Government of Iran|provisional revolutionary government]] of Prime Minister [[Mehdi Bazargan]], which they believed was plotting to normalize relations with the United States and extinguish Islamic revolutionary ardor in Iran.<ref>Bowden, ''Guests of the Ayatollah'', (2006) p. 10</ref> |

|||

===First attempt=== |

|||

{{Further|Kenneth Kraus}} |

|||

On the morning of February 14, 1979, the [[Organization of Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas]] stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and took a Marine named [[Kenneth Kraus]] hostage. Ambassador [[William H. Sullivan]] surrendered the embassy to save lives, and with the assistance of Iranian Foreign Minister [[Ebrahim Yazdi]], returned the embassy to U.S. hands within three hours.<ref name=Houghton_Book>{{cite book |last=Houghton |first=David Patrick |title=US foreign policy and the Iran hostage crisis |year=2001 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=Cambridge [u.a.] |isbn=978-0-521-80509-4 |page=77 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=cPf-vBzU46EC&q=Kraus |access-date=June 20, 2015 |archive-date=July 5, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230705205917/https://books.google.com/books?id=cPf-vBzU46EC&q=Kraus |url-status=live }}</ref> Kraus was injured in the attack, kidnapped by the militants, tortured, tried, and convicted of murder. He was to be executed, but President Carter and Sullivan secured his release within six days.<ref name=Deseret>{{cite news|author=Engelmayer, Sheldon|title=Hostage Suit Tells Torture|url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=336&dat=19810204&id=hj8jAAAAIBAJ&pg=4479,414133|newspaper=The Deseret News|date=February 4, 1981|access-date=October 18, 2020|archive-date=November 25, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211125193501/https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=336&dat=19810204&id=hj8jAAAAIBAJ&pg=4479%2C414133|url-status=live}}</ref> This incident became known as the Valentine's Day Open House.<ref name=CIA_DAugherty>{{cite news |last=Daugherty |first=William J. |title=A First Tour Like No Other |url=https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/csi-studies/studies/spring98/iran.html |publisher=Central Intelligence Agency |year=1996 |access-date=October 12, 2011 |archive-date=August 3, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190803183920/https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/csi-studies/studies/spring98/iran.html }}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Shredded 1979-09-01 1305Z CIA cable from American Embassy Tehran.jpg|thumb|Anticipating the takeover of the embassy, the Americans tried to destroy [[classified document]]s in a furnace. The furnace malfunctioned and the staff was forced to use cheap paper shredders.<ref>[[#Bowden|Bowden]], p. 30</ref><ref>[[#Farber|Farber]], p. 134</ref> Skilled carpet weavers were later employed to reconstruct the documents.<ref>[[#Bowden|Bowden]], p. 337</ref>]] |

|||

A later study claimed that there had been no plots for the overthrow of the revolutionaries by the United States, and that a CIA intelligence gathering mission at the embassy was "notably ineffectual, gathering little information and hampered by the fact that none of the three officers spoke the local language, [[Persian language|Farsi]]". Its work was "routine, prudent espionage conducted at diplomatic missions everywhere".<ref name="Journal">{{cite web |url=http://www.homelandsecurity.org/newjournal/BookReviews/displayBookReview2.asp?review=63 |title=Journal of Homeland Security review of Mark Bowden's "Guests of the Ayatollah" |accessdate=2007-02-25 |quote=routine, prudent espionage conducted at diplomatic missions everywhere |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

===Second attempt=== |

|||

==Prelude== |

|||

The |

The next attempt to seize the American Embassy was planned for September 1979 by [[Ebrahim Asgharzadeh]], a student at the time. He consulted with the heads of the Islamic associations of Tehran's main universities, including the [[University of Tehran]], [[Sharif University of Technology]], [[Amirkabir University of Technology]] (Polytechnic of Tehran), and [[Iran University of Science and Technology]]. They named their group [[Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line]]. |

||

Asgharzadeh later said there were five students at the first meeting, two of whom wanted to target the Soviet |

Asgharzadeh later said there were five students at the first meeting, two of whom wanted to target the Soviet Embassy because the USSR was "a [[Marxist]] and anti-God regime". Two others, [[Mohsen Mirdamadi]] and [[Habibolah Bitaraf]], supported Asgharzadeh's chosen target, the United States. "Our aim was to object against the American government by going to their embassy and occupying it for several hours," Asgharzadeh said. "Announcing our objections from within the occupied compound would carry our message to the world in a much more firm and effective way."<ref>{{cite web |author=Bowden, Mark |author-link=Mark Bowden |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/doc/200412/bowden |title=Among the Hostage-Takers |work=The Atlantic |date=December 2004 |access-date=May 5, 2016 |archive-date=May 12, 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080512023231/http://www.theatlantic.com/doc/200412/bowden |url-status=live }}</ref> Mirdamadi told an interviewer, "We intended to detain the diplomats for a few days, maybe one week, but no more."<ref>Molavi, Afshin (2005) ''The Soul of Iran'', Norton. p. 335. {{ISBN|0393325970}}</ref> [[Masoumeh Ebtekar]], the spokeswoman for the Iranian students during the crisis, said that those who rejected Asgharzadeh's plan did not participate in the subsequent events.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://irannegah.com/Video.aspx?id=579 |title=Iran Negah |publisher=Iran Negah |access-date=May 5, 2016 |archive-date=May 29, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120529010557/http://irannegah.com/Video.aspx?id=579 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

The |

The students observed the procedures of the [[Marine Security Guard]]s from nearby rooftops overlooking the embassy. They also drew on their experiences from the recent revolution, during which the U.S. Embassy grounds were briefly occupied. They enlisted the support of police officers in charge of guarding the embassy and of the Islamic [[Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps|Revolutionary Guards]].<ref>[[#Bowden|Bowden]], pp. 8, 13</ref> |

||

According to the group and other sources Khomeini did not know of the plan beforehand.<ref>{{cite news |title=Radicals Reborn |author=Scott Macleod |url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,992548,00.html |newspaper=Time |

According to the group and other sources, Ayatollah Khomeini did not know of the plan beforehand.<ref>{{cite news |title=Radicals Reborn |author=Scott Macleod |url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,992548,00.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070313093649/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,992548,00.html|archive-date=March 13, 2007|newspaper=Time|date=November 15, 1999|access-date=April 26, 2012}}</ref> The students had wanted to inform him, but according to the author [[Mark Bowden]], Ayatollah [[Mohammad Mousavi Khoeiniha]] persuaded them not to do so. Khoeiniha feared that the government would use the police to expel the students as they had the occupiers in February. The provisional government had been appointed by Khomeini, so Khomeini was likely to go along with the government's request to restore order. On the other hand, Khoeiniha knew that if Khomeini first saw that the occupiers were faithful supporters of him (unlike the leftists in the first occupation) and that large numbers of pious Muslims had gathered outside the embassy to show their support for the takeover, it would be "very hard, perhaps even impossible," for him to oppose the takeover, and this would paralyze the Bazargan administration, which Khoeiniha and the students wanted to eliminate.<ref>[[#Bowden|Bowden]], p. 12</ref> |

||

Supporters of the takeover stated that their motivation was fear of another American-backed coup against their popular revolution. |

|||

Though fear of an American-backed return by the Shah was the publicly stated reason, the true cause of the seizure was the long-standing [[United States-Iran relations#Mohammad Reza Pahlavi reign|U.S. support for the Shah's government]]{{Citation needed|date=October 2012}}. Vital parts of this Islamic Revolution were propaganda and demonstrations against the United States and against President Jimmy Carter. After the Shah's entry into the United States, the Ayatollah Khomeini called for anti-American street demonstrations. On November 4, 1979, one such demonstration, organized by Iranian student unions loyal to Khomeini, took place outside the walled compound housing the U.S. Embassy. |

|||

===Takeover=== |

===Takeover=== |

||

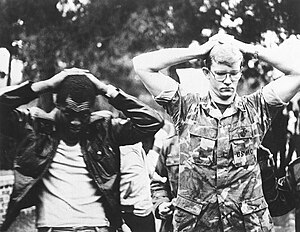

[[File:Two American hostages in Iran hostage crisis.jpg|300px|thumbnail|Two American hostages during the siege of the U.S. Embassy.]] |

|||

Around 6:30 a.m. on November 4, 1979, the ringleaders gathered between 300 and 500 selected students, thereafter known as [[Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line]], and briefed them on the battle plan. A female student was given a pair of metal cutters to break the chains locking the embassy's gates, and she hid them beneath her [[chador]].<ref>[http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,992548,00.html Radicals Reborn Iran's student heroes have had a rough and surprising passage]</ref> |

|||

On November 4, 1979, one of the demonstrations organized by Iranian student unions loyal to Khomeini erupted into an all-out conflict right outside the walled compound housing the U.S. Embassy. |

|||

At about 6:30 a.m., the ringleaders gathered between three hundred and five hundred selected students and briefed them on the battle plan. A female student was given a pair of metal cutters to break the chains locking the embassy's gates and hid them beneath her [[chador]].<ref>{{cite magazine|last=Macleod |first=Scott |url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,992548,00.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070313093649/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,992548,00.html |archive-date=March 13, 2007 |title=Radicals Reborn |magazine=TIME |date=November 15, 1999 |access-date=May 5, 2016}}</ref> |

|||

At first, the students' plan to only make a symbolic occupation, release statements to the press, and leave when government security forces came to restore order was reflected in placards saying "Don't be afraid. We just want to set-in". When the embassy guards brandished firearms, the protesters retreated, one telling the Americans, "We don't mean any harm".<ref>Bowden, ''Guests of the Ayatollah'', (2006), pp. 40, 77</ref> But as it became clear the guards would not use deadly force and that a large angry crowd had gathered outside the compound to cheer the occupiers and jeer the hostages, the occupation changed.<ref>Bowden, ''Guests of the Ayatollah'', (2006), pp. 127–8</ref> According to one embassy staff member, buses full of demonstrators began to appear outside the embassy shortly after the Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line broke through the gates.<ref name="multiref2">Bowden, ''Guests of the Ayatollah'', (2006)</ref> |

|||

At first, the students planned a symbolic occupation, in which they would release statements to the press and leave when government security forces came to restore order. This was reflected in placards saying: "Don't be afraid. We just want to sit in." When the embassy guards brandished firearms, the protesters retreated, with one telling the Americans, "We don't mean any harm."<ref>[[#Bowden|Bowden]], pp. 40, 77</ref> But as it became clear that the guards would not use deadly force and that a large, angry crowd had gathered outside the compound to cheer the occupiers and jeer the hostages, the plan changed.<ref>[[#Bowden|Bowden]], pp. 127–28</ref> According to one embassy staff member, buses full of demonstrators began to appear outside the embassy shortly after the Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line broke through the gates.<ref name="multiref2">[[#Bowden|Bowden]]</ref> |

|||

As Ayatollah Musavi Khoeyniha had hoped, Khomeini supported the takeover. According to Foreign Minister [[Ebrahim Yazdi]], when he, Yazdi came to [[Qom]] to tell the Imam about the incident, Khomeini told the minister to "go and kick them out". But later that evening, back in Tehran, the minister heard on the radio that Imam Khomeini had issued a statement supporting the seizure and calling it "the second revolution", and the embassy an "American spy den in Tehran".<ref>Bowden, ''Guests of the Ayatollah'', (2006) p. 93</ref> |

|||

As Khomeini's followers had hoped, Khomeini supported the takeover. According to Foreign Minister Yazdi, when he went to [[Qom]] to tell Khomeini about it, Khomeini told him to "go and kick them out." But later that evening, back in Tehran, Yazdi heard on the radio that Khomeini had issued a statement supporting the seizure, calling it "the second revolution" and the embassy an "[[Embassy of the United States, Tehran|American spy den in Tehran]]."<ref>[[#Bowden|Bowden]], p. 93</ref> |

|||

The occupiers bound and blindfolded the embassy Marines and staff and paraded them in front of photographers. In the first couple of days, many of the embassy staff who had snuck out of the compound or not been there at the time of the takeover were rounded up by Islamists and returned as hostages.<ref>Bowden, ''Guests of the Ayatollah'', (2006) p. 50, 132–4</ref> Six American diplomats did however avoid capture and took refuge in the [[United Kingdom|British]] embassy before being transferred to the Canadian Embassy and others went to the [[Sweden|Swedish]] embassy in Tehran for three months. ([[Canadian caper]]) A joint Canadian government–[[Central Intelligence Agency]] covert operation managed to smuggle them out of Iran using Canadian passports and a cover story disguising them as a Canadian film crew on January 28, 1980.<ref>[http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.org/documents/list_of_hostages.phtml Jimmy Carter Library]</ref> |

|||

[[File:Iran Hostage Crisis Newsreel.ogg|thumb|thumbtime=7|A two-minute [[video clip|clip]] from a [[newsreel]] regarding the hostage crisis (1980)]] |

|||

===Hostage-holding motivations=== |

|||

The Marines and embassy staff were blindfolded by the occupiers and then paraded in front of assembled photographers. In the first couple of days, many of the embassy workers who had sneaked out of the compound or had not been there at the time of the takeover were rounded up by Islamists and returned as hostages.<ref>[[#Bowden|Bowden]], pp. 50, 132–34</ref> Six American diplomats managed to avoid capture and took refuge in the British Embassy before being transferred to the Canadian Embassy. In a joint covert operation known as the [[Canadian caper]], the Canadian government and the CIA managed to smuggle them out of Iran on January 28, 1980, using Canadian passports and a cover story that identified them as a film crew.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.org/documents/list_of_hostages.phtml |title=The Hostages and The Casualties |work=JimmyCarterLibrary.org |access-date=November 4, 2004 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20041108083936/http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.org/documents/list_of_hostages.phtml |archive-date=November 8, 2004 }}</ref> Others went to the Swedish Embassy in Tehran for three months. |

|||

The Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line demanded that the Shah return to Iran for trial and execution. The U.S. maintained that the Shah, who died less than a year later in July 1980, had come to America only for medical attention. The group's other demands included that the U.S. government apologize for its interference in the internal affairs of Iran, for the overthrow of Prime Minister Mosaddegh (in 1953), and that Iran's frozen assets in the United States be released. |

|||

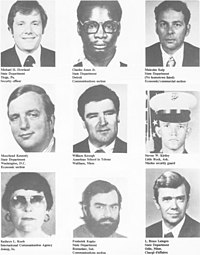

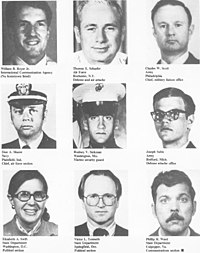

A State Department diplomatic cable of November 8, 1979, details "A Tentative, Incomplete List of U.S. Personnel Being Held in the Embassy Compound."<ref>{{cite web|url=https://aad.archives.gov/aad/|title=National Archives and Records Administration, Access to Archival Databases (AAD): Central Foreign Policy Files, created 7/1/1973 – 12/31/1979; Electronic Telegrams, 1979 (searchable database)|website=Aad.archives.gov|access-date=May 5, 2016|archive-date=May 1, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160501092934/https://aad.archives.gov/aad/|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Iran-hostages-b.jpg|thumb|left|Hostage Barry Rosen, age 34]] |

|||

The initial takeover plan was to hold the embassy for only a short time, but this changed after it became apparent how popular the takeover was and that [[Khomeini]] had given it his full support.<ref name="multiref2"/> Some attribute the Iranian decision not to release the hostages quickly to U.S. President Jimmy Carter's "blinking" or failure to immediately deliver an ultimatum to Iran.<ref>Moin, ''Khomeini'' (2001), p. 226</ref> His immediate response was to appeal for the release of the hostages on humanitarian grounds and to share his hopes of a strategic anti-communist alliance with the Islamic Republic.<ref>Moin, ''Khomeini,'' (2000), p. 221; "America Can't do a Thing" by Amir Taheri ''New York Post,'' November 2, 2004</ref> As some of the student leaders had hoped, Iran's moderate prime minister [[Mehdi Bazargan]] and his cabinet resigned under pressure just days after the event. |

|||

===Motivations=== |

|||

The duration of the hostages' captivity has been blamed on internal Iranian revolutionary politics. As Ayatollah Khomeini told Iran's president: |

|||

The [[Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line]] demanded that Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi return to Iran for trial and execution. The U.S. maintained that the Shah – who was to die less than a year later, in July 1980 – had come to America for medical attention. The group's other demands included that the U.S. government apologize for its interference in the internal affairs of Iran, including the overthrow of Prime Minister Mosaddegh in 1953, and that [[Iran's frozen assets]] in the United States be released. |

|||

<blockquote>This action has many benefits. "... This has united our people. Our opponents do not dare act against us. We can put the constitution to the people's vote without difficulty, and carry out presidential and parliamentary elections."<ref>Moin, ''Khomeini,'' (2000), p. 228</ref></blockquote> |

|||

[[File:Iran-hostages-b.jpg|thumb|left|[[Barry Rosen]], the embassy's press attaché, was among the hostages. The man on the right holding the briefcase is [[Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and the 1979 hostage crisis|alleged by some former hostages]] to be future President [[Mahmoud Ahmadinejad]], although he, Iran's government, and the [[CIA]] deny this.]] |

|||

Theocratic Islamists, as well as leftist political groups and figures like leftist [[People's Mujahedin of Iran]],<ref>Abrahamian, Ervand (1989), ''The Iranian Mojahedin'' (1989), p. 196</ref> supported the taking of American hostages as an attack on "American imperialism" and its alleged Iranian "tools of the West". Revolutionary teams displayed secret documents purportedly taken from the embassy, sometimes painstakingly reconstructed after [[paper shredder|shredding]],<ref>[http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/nsa/publications/iran/irdoc.html Iran, 1977–1980/Document]</ref> to buttress their claim that "the Great Satan" (the U.S.) was trying to destabilize the new regime, and that Iranian moderates were in league with the U.S. The documents were published in a series of books called ''Documents from the US Espionage Den'' ({{lang-fa|اسناد لانه جاسوسی امریكا}}). These books included telegrams, correspondence, and reports from the U.S. [[State Department]] and [[Central Intelligence Agency]]. According to a Federation of American Scientists Bulletin from 1997, "By 1995, an amazing 77 volumes of 'Documents from the U.S. Espionage Den' (Asnad-i lanih-'i Jasusi) had been collected and published by the 'Muslim Students Following the Line of the Imam'."<ref> Secrecy & Government Bulletin, Issue Number 70, September 1997 http://www.fas.org/sgp/bulletin/sec70.html</ref> Many of these volumes of unredacted documents are now available online.<ref>http://archive.org/details/DocumentsFromTheU.s.EspionageDen</ref> |

|||

The initial plan was to hold the embassy for only a short time, but this changed after it became apparent how popular the takeover was and that Khomeini had given it his full support.<ref name="multiref2"/> Some attributed the decision not to release the hostages quickly to President Carter's failure to immediately deliver an ultimatum to Iran.<ref>[[#Moin|Moin]], p. 226</ref> His initial response was to appeal for the release of the hostages on humanitarian grounds and to share his hopes for a strategic [[Anti-communism|anti-communist]] alliance with the Ayatollah.<ref>[[#Moin|Moin]], p. 221; "America Can't do a *** Thing" by Amir Taheri ''New York Post,'' November 2, 2004</ref> As some of the student leaders had hoped, Iran's moderate prime minister, Bazargan, and his cabinet resigned under pressure just days after the takeover. |

|||

The duration of the hostages' captivity has also been attributed to internal Iranian revolutionary politics. As Ayatollah Khomeini told Iran's president: |

|||

[[File:DF-SN-82-06759.jpg|thumb|right|200px|A group photograph of the former hostages in the hospital. The 52 hostages are spending a few days in the hospital after their release from Iran prior to their departure for the United States.]] |

|||

By embracing the hostage-taking under the slogan "America can't do a thing", Khomeini rallied support and deflected criticism from his controversial [[Constitution of Islamic Republic of Iran|Islamic theocratic constitution]],<ref>Arjomand, Said Amir, ''Turban for the Crown: The Islamic Revolution in Iran'' by Said Amir Arjomand, Oxford University Press, 1988 p. 139</ref> which was due for a referendum vote in less than one month.<ref>Moin, ''Khomeini'' (2000), p. 227</ref> Following the successful referendum, both leftists and theocrats continued to use the issue of alleged pro-Americanism to suppress their opponents, the relatively moderate political forces, which included the Iranian Freedom Movement, National Front, Grand Ayatollah Shari'atmadari,<ref>Moin, ''Khomeini'' (2000), pp. 229, 231; Bakhash, ''Reign of the Ayatollahs'', (1984), pp. 115–6</ref> and later President [[Abolhassan Banisadr]]. In particular, carefully selected diplomatic dispatches and reports discovered at the embassy and released by the hostage-takers led to the disempowerment and resignations of moderate figures<ref>Bakhash, ''Reign of the Ayatollahs'', (1984), p. 115</ref> such as Premier Mehdi Bazargan. The political danger in Iran of any move seen as accommodating America, along with the failed rescue attempt, delayed a negotiated release. After the hostages were released, leftists and theocrats turned on each other, with the stronger theocratic group annihilating the left. |

|||

{{wikisource|Documents Seized from the US Embassy in Tehran}} |

|||

[[File:Man holding sign during Iranian hostage crisis protest, 1979.jpg|thumb|340px|right|A man holding a sign during a protest of the crisis in Washington, D.C., in 1979. The sign reads "Deport all Iranians" and "Get the hell out of my country" on its forefront, and "Release all Americans now" on its back.]] |

|||

<blockquote>This has united our people. Our opponents do not dare act against us. We can put the constitution to the people's vote without difficulty, and carry out presidential and parliamentary elections.<ref>[[#Moin|Moin]], p. 228</ref></blockquote> |

|||

==444 days hostage== |

|||

Various leftist student groups also supported the taking of hostages at the US embassy.<ref name=terronomics>{{cite book|title=Terrornomics |editor=Costigan, Sean S. |editor2=Gold, David |publisher=[[Taylor & Francis]]|page=66-67|year=2007|isbn=978-0-7546-4995-3}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|year=2009|isbn=978-0-230-61811-4|title=The United States and Iran: Policy Challenges and Opportunities |author=Roshandel, Jalil |author2=Cook, Alethia H. |page=78|publisher=[[Palgrave Macmillan]]}}</ref><ref>Abrahamian, Ervand (1989), ''The Iranian Mojahedin''. Yale University Press. p. 196. {{ISBN|978-0300052671}}</ref> The embassy take-over was aimed at strengthening the new regime against liberal elements in the government, portraying the regime as a "revolutionary force" while winning over the major following that the People's Mojahedin of Iran had amongst students in Iran.<ref name=twquarterly>{{cite journal|last1=Sreberny-Mohammadi|first1=Annabelle|first2=Ali|last2=Mohammadi|title=Post-Revolutionary Iranian Exiles: A Study in Impotence|journal=Third World Quarterly|date=January 1987|volume=9|issue=1|pages=108–129|jstor=3991849|doi=10.1080/01436598708419964}}</ref> According to scholar [[Daniel Pipes]], writing in 1980, the [[Marxism|Marxist]]-leaning leftists and the Islamists shared a common antipathy toward market-based reforms under the late Shah, and both subsumed individualism, including the unique identity of women, under conservative, though contrasting, visions of collectivism. Accordingly, both groups favored the Soviet Union over the United States in the early months of the Iranian Revolution.<ref name="PipesNYT1980">{{cite news|last1=Pipes|first1=Daniel|author-link1=Daniel Pipes|title=Khomeini, the Soviets and U.S.: why the Ayatollah fears America|work=[[New York Times]]|date=May 27, 1980}}</ref> The Soviets, and possibly their allies [[Cuba]], [[History of Libya under Muammar Gaddafi#Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (1977–2011)|Libya]], and East Germany, were suspected of providing indirect assistance to the participants in the takeover of the U.S. embassy in Tehran. The [[Palestine Liberation Organization|PLO]] under [[Yasser Arafat]] provided personnel, intelligence liaisons, funding, and training for Khomeini's forces before and after the revolution and was suspected of playing a role in the embassy crisis.<ref name="Bergman">{{cite book|last1=Bergman|first1=Ronan|title=The Secret War with Iran: the 30-Year Clandestine Struggle against the World's Most Dangerous Terrorist Power|url=https://archive.org/details/secretwarwithira00berg|url-access=registration|date=2008|publisher=[[Free Press (publisher)|Free Press]]|location=[[New York City|New York]]|isbn=978-1-4165-7700-3|pages=[https://archive.org/details/secretwarwithira00berg/page/30 30–31]|edition=1st}}</ref> [[Fidel Castro]] reportedly praised Khomeini as a revolutionary anti-imperialist who could find common cause between revolutionary leftists and anti-American Islamists. Both expressed disdain for modern [[capitalism]] and a preference for authoritarian collectivism.<ref name="Geyer">{{cite book|last1=Geyer|first1=Georgie Anne|author-link1=Georgie Anne Geyer|title=Guerrilla Prince: the Untold Story of Fidel Castro|date=2001|publisher=[[Andrews McMeel Universal]]|location=[[Kansas City, Missouri|Kansas City]]|isbn=0-7407-2064-3|page=348|edition=3rd}}</ref> Cuba and its socialist ally Venezuela, under [[Hugo Chávez]], would later form [[ALBA]] in alliance with the Islamic Republic as a counter to [[neoliberalism|neoliberal]] American influence. |

|||

===Hostage conditions=== |

|||

The hostage-takers released 13 women and African Americans in the middle of November 1979, claiming they were sympathetic to oppressed minorities. One more hostage, a white man named [[Richard Queen]], was released in July 1980 after he became seriously ill with what was later diagnosed as [[multiple sclerosis]]. The remaining 52 hostages were held captive until January 1981, a total of 444 days of captivity. |

|||

Revolutionary teams displayed secret documents purportedly taken from the embassy, sometimes painstakingly reconstructed after [[paper shredder|shredding]],<ref name="Retrieved">{{cite web |url=http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/nsa/publications/iran/irdoc.html |title=Iran, 1977–1980/Document |website=Gwu.edu |access-date=May 5, 2016 |archive-date=March 8, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140308175026/http://www2.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/nsa/publications/iran/irdoc.html |url-status=live }}</ref> to buttress their claim that the U.S. was trying to destabilize the new regime. |

|||

The hostages initially were held in buildings at the embassy, but after the failed rescue mission they were scattered to different locations around Iran to make rescue impossible. Three high level officials—Bruce Laingen, Victor Tomseth, and Mike Howland—were at the Foreign ministry at the time of the takeover. They stayed there for some months, sleeping in the ministry's formal dining room and washing their socks and underwear in the bathroom. They were first treated as diplomats but after the provisional government fell relations deteriorated and by March the doors to their living space were kept "chained and padlocked".<ref>Bowden, 2006, pp. 151, 219, 372</ref> |

|||

By embracing the hostage-taking under the slogan "America can't do a thing," Khomeini rallied support and deflected criticism of his controversial [[Constitution of Islamic Republic of Iran|theocratic constitution]],<ref>Arjomand, Said Amir (1988) ''Turban for the Crown: The Islamic Revolution in Iran''. Oxford University Press. p. 139. {{ISBN|9780195042580}}</ref> which was scheduled for a referendum vote in less than one month.<ref>[[#Moin|Moin]], p. 227</ref> The referendum was successful, and after the vote, both leftists and theocrats continued to use allegations of [[pro-Americanism]] to suppress their opponents: relatively moderate political forces that included the Iranian Freedom Movement, the [[National Front (Iran)|National Front]], Grand Ayatollah [[Mohammad Kazem Shariatmadari]],<ref>[[#Moin|Moin]], pp. 229, 231</ref><ref>[[#Bakhash|Bakhash]], pp. 115–16</ref> and later President [[Abolhassan Banisadr]]. In particular, carefully selected diplomatic dispatches and reports discovered at the embassy and released by the hostage-takers led to the disempowerment and resignation of moderate figures<ref>[[#Bakhash|Bakhash]], p. 115</ref> such as Bazargan. The failed rescue attempt and the political danger of any move seen as accommodating America delayed a negotiated release of the hostages. After the crisis ended, leftists and theocrats turned on each other, with the stronger theocratic group annihilating the left. |

|||

By midsummer 1980 the Iranians moved the hostages to prisons in Tehran<ref>Bowden, 2006, p. 528</ref> to prevent either escape or rescue attempts and to improve the logistics of guard shifts and food delivery.<ref>Bowden, 2006, pp. 514–5</ref> The final holding area, from Nov. 1980 until their release, was the Teymour Bakhtiari mansion in Tehran, where the hostages were finally provided tubs, showers and hot and cold running water.<ref>Bowden, 2006, p. 565</ref> Several foreign diplomats and ambassadors—including Canadian ambassador [[Kenneth D. Taylor|Ken Taylor]] prior to the [[Canadian Caper]]—came to visit the hostages over the course of the crisis, relaying information back to the U.S. government—including the "Laingen dispatches", made by hostage [[Bruce Laingen]]—to help the home country stay in contact. |

|||

{{Wikisource|Portal:Documents Seized from the US Embassy in Tehran}} |

|||

[[File:Man holding sign during Iranian hostage crisis protest, 1979.jpg|thumb|An anti-Iranian protest in Washington, D.C., in 1979. The front of the sign reads "Deport all Iranians" and "Get the hell out of my country", and the back reads "Release all Americans now".]] |

|||

== Documents discovered inside the American embassy == |

|||

Iranian propaganda stated that the hostages were "guests" treated with respect. [[Ibrahim Asgharzadeh]] described the original hostage taking plan as a "nonviolent" and symbolic action where the "gentle and respectful treatment" of the hostages would dramatize to the whole world the offended sovereignty and dignity of Iran.<ref>Bowden, 2006, p. 128</ref> In America, an Iranian [[chargé d'affaires]], Ali Agha, stormed out of meeting with an American official, exclaiming "We are not mistreating the hostages. They are being very well taken care of in Tehran. They are our guests."<ref>Bowden, 2006, p. 403</ref> |

|||

Supporters of the takeover claimed that in 1953, the American Embassy had been used as a "den of spies" from which the coup was organized. Later, documents which suggested that some of the members of the embassy's staff had been working with the Central Intelligence Agency were found inside the embassy. Afterwards, the CIA confirmed its role and that of MI6 in ''Operation Ajax''.<ref>{{cite web |author=Kamali Dehghan, Saeed |author2=Norton-Taylor, Richard |title=CIA admits role in 1953 Iranian coup |url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/aug/19/cia-admits-role-1953-iranian-coup |website=The Guardian |date=August 19, 2013 |access-date=November 10, 2019 |archive-date=April 12, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200412154106/https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/aug/19/cia-admits-role-1953-iranian-coup |url-status=live }}</ref> After the Shah entered the United States, Ayatollah Khomeini called for street demonstrations.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Afary |first1=Janet |title=Iranian Revolution |url=https://www.britannica.com/event/Iranian-Revolution |website=Encyclopaedia Britannica |access-date=November 10, 2019 |archive-date=November 24, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191124183040/https://www.britannica.com/event/Iranian-Revolution |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

Revolutionary teams displayed secret documents purportedly taken from the embassy, sometimes painstakingly reconstructed after [[paper shredder|shredding]],<ref name="Retrieved"/> in order to buttress their claim that "the Great Satan" (the U.S.) was trying to destabilize the new regime with the assistance of Iranian moderates who were in league with the U.S. The documents – including telegrams, correspondence, and reports from the U.S. [[State Department]] and the CIA – were published in a series of books which were titled ''Documents from the U.S. Espionage Den'' ({{lang-fa|اسناد لانه جاسوسی امریكا}}).<ref>{{cite news |last1=Sciolino |first1=Elaine |title=7 Years after Embassy Seizure, Iran Still Prints U.S. Secrets |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1986/07/10/world/7-years-after-embassy-seizure-iran-still-prints-us-secrets.html |date=July 10, 1986 |work=[[New York Times]] |access-date=November 10, 2019 |archive-date=November 10, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191110080145/https://www.nytimes.com/1986/07/10/world/7-years-after-embassy-seizure-iran-still-prints-us-secrets.html |url-status=live }}</ref> According to a 1997 [[Federation of American Scientists]] bulletin, by 1995, 77 volumes of ''Documents from the U.S. Espionage Den'' had been published.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://fas.org/sgp/bulletin/sec70.html |title=Secrecy & Government Bulletin, Issue 70 |website=Fas.org |date=May 29, 1997 |access-date=May 5, 2016 |archive-date=May 10, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170510204553/https://fas.org/sgp/bulletin/sec70.html |url-status=live }}</ref> Many of these volumes are now available online.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://archive.org/details/DocumentsFromTheU.s.EspionageDen |title=Documents from the U.S. Espionage Den |via=[[Internet Archive]] |date=March 10, 2001 |access-date=August 1, 2013}}</ref> |

|||

The actual treatment of the hostages was far different from that purported in Iranian propaganda: the hostages described beatings,<ref>(Rick Kupke in Bowden, 2006, p. 81, Charles Jones, Colonel Dave Roeder, Metrinko, Tom Ahern (in Bowden, 2006, p. 295)</ref> theft,<ref>Hall in Bowden, 2006, p. 257, Limbert in Bowden, 2006, p. 585</ref> the fear of bodily harm while being paraded blindfold before a large, angry chanting crowd outside the embassy (Bill Belk and Kathryn Koob),<ref>in Bowden, 2006, p. 267</ref> having their hands bound "day and night" for days<ref>Bill Belk in Bowden, 2006, pp. 65, 144, Malcolm Kalp in Bowden, 2006, pp. 507–511</ref> or even weeks,<ref>Queen, in Bowden, 2006, p. 258, Metrinko, in Bowden, (2006), p. 284</ref> long periods of solitary confinement<ref>Bowden, 2006, pp. 307, 344, 405, 540</ref> and months of being forbidden to speak to one another<ref>Bowden, 2006, pp. 149, 351–2</ref> or stand, walk, and leave their space unless they were going to the bathroom.<ref>Bowden, 2006, p. 161</ref> In particular they felt the threat of trial and execution,<ref>Bowden, 2006, p. 597</ref> as all of the hostages "were threatened repeatedly with execution, and took it seriously".<ref>Bowden, 2006, p. 203</ref> The hostage takers played [[Russian roulette]] with their victims.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=hfhkAAAAIBAJ&pg=6225,19155|title=Russian roulette played with hostages|place=New York|agency=Associated Press|work=Edmonton Journal|date=January 21, 1981|page=A3}}</ref> |

|||

==The 444-day crisis== |

|||

The most terrifying night for the hostages came on February 5, 1980, when guards in black ski masks rousted the 53 hostages from their sleep and led them blindfolded to other rooms. They were searched after being ordered to strip themselves until they were bare, and to keep their hands up. They were then told to kneel down. "This was the most terrifying moment" as one hostage said. They were still wearing the blindfolds, so naturally, they were terrified even further. One of the hostages later recalled 'It was an embarrassing moment. However, we were too scared to realize it.' The [[mock execution]] ended after the guards cocked their weapons and readied them to fire but finally ejected their rounds and told the prisoners to wear their clothes again. The hostages were later told the exercise was "just a joke" and something the guards "had wanted to do". However, this affected a lot of the hostages long after.<ref>Bowden, (2006), pp. 346–350</ref> |

|||

{{For timeline|Timeline of the Iranian hostage crisis}} |

|||

===Living conditions of the hostages=== |

|||

Michael Metrinko was kept in solitary confinement for months. On two occasions when he expressed his opinion of Ayatollah Khomeini and he was punished especially severely in relation to the ordinary mistreatment of the hostages—the first time being kept in handcuffs for 24 hours a day for two weeks,<ref>Bowden, (2006), p. 284</ref> and being beaten and kept alone in a freezing cell for two weeks with a diet of bread and water the second time.<ref>Bowden, 2006, p. 544</ref> |

|||

The hostage-takers, declaring their solidarity with other "oppressed minorities" and declaring their respect for "the special place of [[women in Islam]]," released one woman and two [[African Americans]] on November 19.<ref name="If">Efty, Alex; 'If Shah Not Returned, Khomeini Sets Trial for Other Hostages'; ''[[Kentucky New Era]]'', November 20, 1979, pp. 1–2</ref> Before release, these hostages were required by their captors to hold a press conference in which Kathy Gross and William Quarles praised the revolution's aims,<ref>[[#Farber|Farber]], pp. 156–57</ref> but four further women and six African-Americans were released the following day.<ref name="If"/> According to the then United States Ambassador to Lebanon, [[John Gunther Dean]], the 13 hostages were released with the assistance of the [[Palestine Liberation Organization]], after [[Yassir Arafat]] and [[Abu Jihad]] personally traveled to Tehran to secure a concession.<ref>{{Cite web | title = American Ambassador Recalls Israeli Assassination Attempt—With U.S. Weapons | last = Killgore | first = Andrew I. | publisher = [[Washington Report on Middle East Affairs]] | date = November 2002 | url = https://www.wrmea.org/002-november/american-ambassador-recalls-israeli-assassination-attempt-with-u.s.-weapons.html | access-date = August 22, 2021 | archive-date = August 22, 2021 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210822075925/https://www.wrmea.org/002-november/american-ambassador-recalls-israeli-assassination-attempt-with-u.s.-weapons.html | url-status = live }}</ref> The only African-American hostage not released that month was Charles A. Jones, Jr.<ref>{{cite news|url = https://www.nytimes.com/1981/01/27/us/no-headline-240600.html|title = Black Hostage Reports Abuse|date = January 27, 1981|access-date = January 4, 2016|newspaper = The New York Times|archive-date = January 5, 2016|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20160105095448/http://www.nytimes.com/1981/01/27/us/no-headline-240600.html|url-status = live}}</ref> One more hostage, a white man named [[Richard Queen]], was released in July 1980 after he became seriously ill with what was later diagnosed as [[multiple sclerosis]]. The remaining 52 hostages were held until January 1981, up to 444 days of captivity. |

|||

The hostages were initially held at the embassy, but after the takers took the cue from the failed rescue mission, the detainees were scattered around Iran in order to make a single rescue attempt impossible. Three high-level officials – [[Bruce Laingen]], [[Victor L. Tomseth]], and Mike Howland – were at the Foreign Ministry at the time of the takeover. They stayed there for several months, sleeping in the ministry's formal dining room and washing their socks and underwear in the bathroom. At first, they were treated as diplomats, but after the provisional government fell, the treatment of them deteriorated. By March, the doors to their living space were kept "chained and padlocked."<ref>[[#Bowden|Bowden]], pp. 151, 219, 372</ref> |

|||

One hostage, U.S. Army medic Donald Hohman, went on a [[hunger strike]] for several weeks<ref>Bowden, 2006, p. 335</ref> and two hostages are thought to have attempted suicide. Steve Lauterbach became despondent, broke a water glass and slashed his wrists after being locked in a dark basement room of the [[chancery (diplomacy)|chancery]] with his hand tightly bound and aching badly. He was found by guards, rushed to the hospital and patched up.<ref>Bowden, 2006, p. 345</ref> Jerry Miele, an introverted CIA communicator technician, smashed his head into the corner of a door, knocking himself unconscious and cutting a deep gash from which blood poured. "Naturally withdrawn" and looking "ill, old, tired, and vulnerable", Miele had become the butt of his guards' jokes who rigged up a mock electric chair with wires to emphasize the fate that awaited him. After his fellow hostages applied first aid and raised alarm, he was taken to a hospital after a long delay created by the guards.<ref>Bowden, 2006, pp. 516–7</ref> |

|||

By midsummer 1980, the Iranians had moved the hostages to prisons in Tehran<ref>[[#Bowden|Bowden]], p. 528</ref> to prevent escapes or rescue attempts and to improve the logistics of guard shifts and food deliveries.<ref>[[#Bowden|Bowden]], pp. 514–15</ref> The final holding area, from November 1980 until their release, was the [[Teymur Bakhtiar]] mansion in Tehran, where the hostages were finally given tubs, showers, and hot and cold running water.<ref>[[#Bowden|Bowden]], p. 565</ref> Several foreign diplomats and ambassadors – including the former Canadian ambassador [[Kenneth D. Taylor|Ken Taylor]] – visited the hostages over the course of the crisis and relayed information back to the U.S. government, including dispatches from Laingen. |

|||

Different hostages described further Iranian threats to boil their feet in oil (Alan B. Golacinski),<ref>Bowden, 2006, p. 158</ref> cut their eyes out (Rick Kupke),<ref>Bowden, 2006, pp. 81–3</ref> or kidnap and kill a disabled son in America and "start sending pieces of him to your wife". (David Roeder)<ref>Air Force Lieutenant Colonel David Roeder in Bowden, 2006, p. 318</ref> |

|||

[[File:Revolutionary occupation of U.S. embassy Title of Islamic Republican newspaper in November 5, 1979.jpg|300px|thumbnail|left|A headline in an [[Islamic Republican newspaper]] on November 5, 1979, read "Revolutionary occupation of U.S. embassy".]] |

|||

Four different hostages attempted to escape<ref>Malcolm Kalp in Bowden, 2006, pp. 507–11, Joe Subic, Kevin Hemening, and Steve Lauterbach, in Bowden, 2006, p. 344</ref> all being punished with stretches of solitary confinement when their attempt was discovered. |

|||

Iranian propaganda stated that the hostages were "guests" and it also stated that they were being treated with respect. Asgharzadeh, the leader of the students, described the original plan as a nonviolent and symbolic action in which the students would use their "gentle and respectful treatment" of the hostages to dramatize the offended sovereignty and dignity of Iran to the entire world.<ref>[[#Bowden|Bowden]], p. 128</ref> In America, an Iranian [[chargé d'affaires]], Ali Agha, stormed out of a meeting with an American official, exclaiming: "We are not mistreating the hostages. They are being very well taken care of in Tehran. They are our guests."<ref>[[#Bowden|Bowden]], p. 403</ref> |

|||

The hostage released for [[multiple sclerosis]], Richard Queen, first developed symptoms of dizziness and numbness in his arm six months before his release.<ref>December 1979</ref> It was misdiagnosed by Iranians first as a reaction to draft of cold air, and after warmer confinement didn't help as "it's nothing, it's nothing", the symptoms of which would soon disappear.<ref>Bowden, 2006, p. 258</ref> Over the months the symptoms spread to his right side and worsened until Queen "was literally flat on his back unable to move without growing dizzy and throwing up".<ref>Bowden, 2006, p. 520</ref> |

|||