Quercus solaris (talk | contribs) Move down orthographic note bc incidental to the biology content. Put 'see also' and ref sections in standard WP order. |

→Orthographic note: as per gram negative article, and Talk page there |

||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

== Orthographic note == |

== Orthographic note == |

||

The adjectives ''gram-positive'' and ''gram-negative'' are conventionally lowercase |

The adjectives ''gram-positive'' and ''gram-negative'' are conventionally lowercase.{{cn}} |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 15:40, 11 June 2014

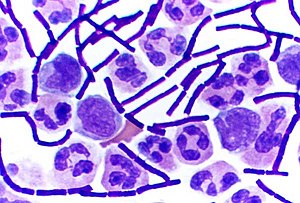

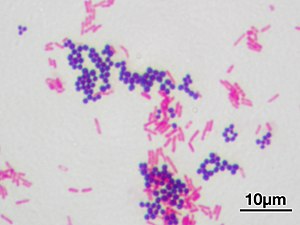

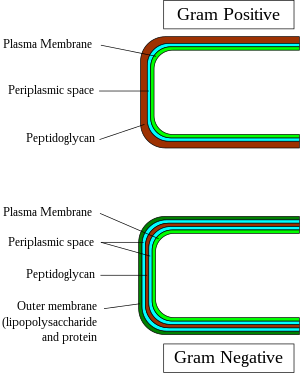

Gram-positive bacteria are a class of bacteria that take up the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. The thick peptidoglycan layer in the cell wall that encases their cell membrane retains the stain, making definitive identification possible.

Gram-negative bacteria cannot retain the violet stain after the decolorization step; alcohol used in the decolorization process degrades the outer membrane of gram-negative cells making the cell wall more porous and incapable of retaining the crystal violet stain. Their peptidoglycan layer is much thinner and sandwiched between an inner cell membrane and a bacterial outer membrane, causing them to take up the counterstain (safranin or fuchsine) and appear red or pink.

Despite their thicker peptidoglycan layer, gram-positive bacteria are more receptive to antibiotics than gram-negative, due to the latter's relatively impermeable lipid based bacterial outer membrane.

Characteristics

In general, the following characteristics are present in gram-positive bacteria:[1]

- Cytoplasmic lipid membrane

- Thick peptidoglycan layer

- Teichoic acids and lipoids are present, forming lipoteichoic acids, which serve as chelating agents, and also for certain types of adherence.

- Peptidoglycan chains are cross-linked to form rigid cell walls by a bacterial enzyme DD-transpeptidase.

Only some species have a capsule usually consisting of polysaccharides. Also only some species are flagellate and when they are they only have two rings to support them (gram-negative have four). Both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria commonly have a surface layer called an S-layer. In gram-positive bacteria, the S-layer is attached to the peptidoglycan layer (in gram-negative bacteria, the S-layer is attached directly to the outer membrane). Specific to gram-positive bacteria is the presence of teichoic acids in the cell wall. Some of which are lipoteichoic acids, which have a lipid component in the cell membrane that can assist in anchoring the peptidoglycan.[2]

Classification

Along with cell shape, Gram staining is a rapid method used to differentiate bacterial species. In traditional and even some areas of contemporary microbiological practice, such staining, alongside growth requirement and antibiotic susceptibility testing, and other macroscopic and physiologic tests, forms the full basis for classification and subdivision of the bacteria (e.g., see figure and pre-1990 versions of Bergey's Manual).

Historically, the kingdom Monera was divided into four divisions based primarily on Gram staining: Firmicutes (positive in staining), Gracilicutes (negative in staining), Mollicutes (neutral in staining) and Mendocutes (variable in staining).[3] Based on 16S ribosomal RNA phylogenetic studies of the late microbiologist Carl Woese and collaborators and colleagues at the University of Illinois, the monophyly of the gram-positive bacteria has been challenged,[4] with striking productive implications for the therapeutic and general study of these organisms. Based on molecular studies of 16S sequences, Woese recognised twelve bacterial phyla, two being gram-positive: high-GC gram-positives and low-GC gram-positives (where G and C refer to the guanine and cytosine content in their genomes),[4] which are now referred to by these names, or as Actinobacteria and Firmicutes. The former, the Actinobacteria, are the high GC content gram-positive bacteria and contains genera such as Corynebacterium, Mycobacterium, Nocardia and Streptomyces. The latter, the Firmicutes are the "low-GC" gram-positive bacteria, which actually have 45%–60% GC content but lower than that of the Actinobacteria.[1]

Importance of the outer cell membrane in bacterial classification

Although bacteria are traditionally divided into two main groups, gram-positive and gram-negative, based on their Gram stain retention property, this classification system is ambiguous as it refers to three distinct aspects (staining result, -envelope organization, taxonomic group), which do not necessarily coalesce for some bacterial species.[5][6][7][8] The gram-positive and gram-negative staining response is also not a reliable characteristic as these two kinds of bacteria do not form phylogenetic coherent groups.[5] However, although Gram staining response of bacteria is an empirical criterion, its basis lies in the marked differences in the ultrastructure and chemical composition of the two main kinds of prokaryotic cells that are found in nature. These kinds of cells are distinguished from each other based upon the presence or absence of an outer lipid membrane, which is a more reliable and fundamental characteristic of the bacterial cells.[5][9]

All gram-positive bacteria are bounded by a single unit lipid membrane, and, in general, they contain a thick layer (20–80 nm) of peptidoglycan responsible for retaining the Gram stain. A number of other bacteria—that are bounded by a single membrane, but stain gram-negative due to either lack of the peptidoglycan layer (viz., mycoplasmas) or their inability to retain the Gram stain because of their cell wall composition—also show close relationship to the gram-positive bacteria. For the bacterial (prokaryotic) cells that are bounded by a single cell membrane the term "monoderm bacteria" or "monoderm prokaryotes" has been proposed.[5][5][9]

In contrast to gram-positive bacteria, all archetypical gram-negative bacteria are bounded by a cytoplasmic membrane and an outer cell membrane; they contain only a thin layer of peptidoglycan (2–3 nm) between these membranes. The presence of inner and outer cell membranes defines a new compartment in these cells: the periplasmic space or the periplasmic compartment. These bacteria/prokaryotes have been designated as "diderm bacteria."[5][9] The distinction between the monoderm and diderm prokaryotes is supported by conserved signature indels in a number of important proteins (viz. DnaK, GroEL).[5][6][9][10] Of these two structurally distinct groups of prokaryotic organisms, monoderm prokaryotes are indicated to be ancestral. Based upon a number of observations including that the gram-positive bacteria are the major producers of antibiotics and that, in general, gram-negative bacteria are resistant to them, it has been proposed that the outer cell membrane in gram-negative bacteria (diderms) has as a protective mechanism against antibiotic selection pressure.[5][6][9][10] Some bacteria, such as Deinococcus, which stain gram-positive due to the presence of a thick peptidoglycan layer and also possess an outer cell membrane are suggested as intermediates in the transition between monoderm (gram-positive) and diderm (gram-negative) bacteria.[5][10] The diderm bacteria can also be further differentiated between simple diderms lacking lipopolysaccharide, the archetypical diderm bacteria where the outer cell membrane contains lipopolysaccharide and the diderm bacteria where outer cell membrane is made up of mycolic acid.[7][10][11]

Exceptions

In general, gram-positive bacteria have a single lipid bilayer (monoderms), whereas gram-negative have two (diderms). Some taxa lack peptidoglycan (such as the domain Archaea, the class Mollicutes, some members of the Rhickettsiales, and the insect-endosymbionts of the Enterobacteriales) and are gram-variable. This, however, does not always hold true. The Deinococcus-Thermus bacteria have gram-positive stains, although they are structurally similar to gram-negative bacteria with two layers (diderms). The Chloroflexi have a single layer, yet (with some exceptions[12]) stain negative.[13] Two related phyla to the Chloroflexi, the TM7 clade and the Ktedonobacteria, are also monoderms.[14][15]

Some Firmicute species are not gram-positive. These belong to the class Mollicutes (alternatively considered a class of the phylum Tenericutes), which lack peptidoglycan (gram-indeterminate), and the class Negativicutes, which includes Selenomonas and stain gram-negative.[11] Additionally, a number of bacterial taxa (viz. Negativicutes, Fusobacteria, Synergistetes and Elusimicrobia) that are either part of the phylum Firmicutes or branch in its proximity are found to possess a diderm cell structure.[8][10][11] However, a conserved signature indel (CSI) in the HSP60 (GroEL) protein distinguishes all traditional phyla of gram-negative bacteria (e.g., Proteobacteria, Aquificae, Chlamydiae, Bacteroidetes, Chlorobi, Cyanobacteria, Fibrobacteres, Verrucomicrobia, Planctomycetes, Spirochetes, Acidobacteria, etc.) from these other atypical diderm bacteria as well as other phyla of monoderm bacteria (e.g., Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, Thermotogae, Chloroflexi, etc.).[10] The presence of this CSI in all sequenced species of conventional LPS (lipopolysaccharide)-containing gram-negative bacterial phyla provides evidence that these phyla of bacteria form a monophyletic clade and that no loss of the outer membrane from any species from this group has occurred.[10]

Pathogenesis

In the classical sense, six gram-positive genera are typically pathogenic in humans. Two of these, Streptococcus and Staphylococcus, are cocci (sphere-shaped bacteria). The remaining organisms are bacilli (rod-shaped bacteria) and can be subdivided based on their ability to form spores. The non-spore formers are Corynebacterium and Listeria (a coccobacillus), whereas Bacillus and Clostridium produce spores.[16] The spore-forming bacteria can again be divided based on their respiration: Bacillus is a facultative anaerobe, while Clostridium is an obligate anaerobe.[17] Also, Rathybacter, Leifsonia, and Clavibacter are three gram-positive genera that cause plant disease.

Orthographic note

The adjectives gram-positive and gram-negative are conventionally lowercase.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ a b Madigan M; Martinko J (editors). (2005). Brock Biology of Microorganisms (11th ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-144329-1.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "Brock" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Gibbons, N. E.; Murray, R. G. E. (1978). "Proposals Concerning the Higher Taxa of Bacteria". IJSEM. 28 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1099/00207713-28-1-1.

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 2439888, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=2439888instead. - ^ a b c d e f g h i Gupta, R.S. (1998) Protein phylogenies and signature sequences: A reappraisal of evolutionary relationships among archaebacteria, eubacteria and eukaryotes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62: 1435–1491.

- ^ a b c Gupta, R.S.(2000) The natural evolutionary relationships among prokaryotes. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 26: 111–131.

- ^ a b Desvaux M, Hébraud M, Talon R, Henderson IR. 2009. Secretion and subcellular localizations of bacterial proteins: a semantic awareness issue. Trends Microbiol. 17:139–145. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2009.01.004

- ^ a b , Sutcliffe IC. 2010. A phylum level perspective on bacterial cell envelope architecture. Trends Microbiol. 18:464–470. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2010.06.005

- ^ a b c d e Gupta, R. S. (1998). What are archaebacteria: life’s third domain or monoderm prokaryotes related to gram-positive bacteria? A new proposal for the classification of prokaryotic organisms. Molecular Microbiology. 29(3):695–707.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gupta, R. S. (2011). Origin of diderm (gram-negative) bacteria: antibiotic selection pressure rather than endosymbiosis likely led to the evolution of bacterial cells with two membranes. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 100:171–182.

- ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19667386, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19667386instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 20495028, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=20495028instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02339.x, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02339.xinstead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11133473, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=11133473instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16751552, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16751552instead. - ^ Gladwin, Mark; Bill Trattler (2007). Clinical Microbiology made ridiculously simple. Miami, FL: MedMaster, Inc. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-940780-81-1.

- ^ Sahebnasagh R, Saderi H, Owlia P. Detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains from clinical samples in Tehran by detection of the mecA and nuc genes. The First Iranian International Congress of Medical Bacteriology; 4–7 September; Tabriz, Iran. 2011. 195 pp.

External links

This article incorporates public domain material from Science Primer. NCBI. Archived from the original on 2009-12-08.

This article incorporates public domain material from Science Primer. NCBI. Archived from the original on 2009-12-08.- 3D structures of proteins associated with plasma membrane of gram-positive bacteria

- 3D structures of proteins associated with outer membrane of gram-positive bacteria

- Gram staining procedure and images