| Fight Club | |

|---|---|

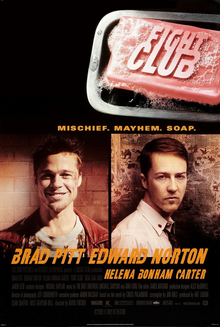

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | David Fincher |

| Written by | Novel: Chuck Palahniuk Screenplay: Jim Uhls |

| Produced by | Art Linson Ross Grayson Bell Cean Chaffin |

| Starring | Edward Norton Brad Pitt Helena Bonham Carter |

| Cinematography | Jeff Cronenweth |

| Edited by | James Haygood |

| Music by | Dust Brothers |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date | October 15, 1999 |

Running time | 139 min. |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | US$63 million |

| Box office | US$100,853,753 (worldwide) |

Fight Club is a 1999 American feature film adaptation of the 1996 novel of the same name by Chuck Palahniuk. The film was directed by David Fincher and follows a nameless protagonist (Edward Norton), an everyman and an unreliable narrator who feels trapped with his white-collar position in society. The narrator gets involved in a fight club with soap salesman Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt) and becomes tangled up in a relationship triangle with Durden and a destitute woman, Marla Singer (Helena Bonham Carter).

Palahniuk's novel was optioned by producer Laura Ziskin, who hired Jim Uhls to write the script for the film. Several directors were sought to film Fight Club; David Fincher was hired to direct based on his interest in the project despite his previous difficulties with the studio 20th Century Fox. Fincher worked with Uhls to develop the script, seeking advice from others in the film industry and his own cast members. Fincher described Fight Club as black comedy that applies heavy satire; he and the cast also compared the film to Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and The Graduate (1967). Thematically, the film was intended to represent the conflict between a generation of young people and the value system of advertising. The film's use of violence in the fight clubs was intended to serve as a metaphor for feeling based on the generation's conflict. The director carried homoerotic overtones over from Palahniuk's novel to implement in the film, believing that the overtones would make audiences uncomfortable and thereby keep them from anticipating the twist ending.

Studio executives were not receptive to the film, and they altered Fincher's intended marketing campaign to try to recoup perceived losses. Fight Club failed to meet expectations at the box office, and the film received polarized reactions from film critics. The film was cited as one of the most controversial and talked-about films of 1999. It was perceived as ground-breaking for its visual style in cinema and presaging a new mood in American political life. The film later found commercial success with its DVD release, which established Fight Club as a cult film. The film has also permeated American society, inspiring people to set up fight clubs.

Plot

The narrator (Edward Norton) is an automobile company employee who travels to accident sites to perform product recall cost appraisals. His doctor refuses to write a prescription for his insomnia and instead suggests that he visit a support group for testicular cancer victims in order to appreciate real suffering. When he attends the group, the narrator allows himself to weep as a form of emotional release. He is then able to sleep soundly and subsequently fakes more illnesses so he can attend other support groups in order to get out his pent up emotions through crying. The narrator's routine is disrupted when he begins to notice another impostor, Marla Singer (Helena Bonham Carter), at the same meetings and his insomnia returns.

During a flight for a business trip, the narrator meets Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt), who makes and sells soap. The narrator arrives home to find his apartment has been destroyed by an explosion. He calls Tyler and meets him at a bar. Tyler agrees to let the narrator stay at his home on the condition that the narrator hits him. The narrator complies and the two end up enjoying a fist fight outside the bar. The narrator moves into Tyler's dilapidated house and the two return to the bar, where they have another fight in the parking lot. After attracting a crowd, they establish a 'fight club' in the bar's basement.

When Marla overdoses on Xanax, she is rescued by Tyler and the two embark upon a sexual relationship. Tyler tells the narrator never to talk about him to Marla. Under Tyler's leadership, the fight club becomes "Project Mayhem," which commits increasingly destructive acts of anti-materialist vandalism in the city. The fight clubs become a network for Project Mayhem, and the narrator is left out of Tyler's activities with the project. After an argument, Tyler disappears from the narrator's life and when a member of Project Mayhem dies on a mission, the narrator attempts to shut down the project. Tracing Tyler's steps, he travels around the country to find that fight clubs have been started in every major city, where one of the participants identifies him as Tyler Durden. A phone call to Marla confirms his identity and he realizes that Tyler is an alter ego of his own split personality. Tyler appears before him and explains that he controls the narrator's body whenever he is asleep.

The narrator faints and awakes to find Tyler has made several phone calls during his blackout and traces his plans to the downtown headquarters of several major credit card companies, which Tyler intends to destroy in order to cripple the financial networks. Failing to find help with the police, many of whom are members of Project Mayhem, the narrator attempts to disarm the explosives in the basement of one of the buildings. He is confronted by Tyler, knocked unconscious, and taken to the upper floor of another building to witness the impending destruction. The narrator, held by Tyler at gunpoint, realizes that in sharing the same body with Tyler, he is the one who is actually holding the gun. He fires it into his mouth, shooting through the cheek without killing himself. The illusion of Tyler collapses with an exit wound to the back of his head. Shortly after, members of Project Mayhem bring a kidnapped Marla to the narrator and leave them alone. The bombs detonate and, holding hands, the two witness the destruction of the entire financial city block through the windows.

Production

Development

In 1996, a 20th Century Fox book scout sent a galley proof of Chuck Palahniuk's novel Fight Club to creative executive Kevin McCormick. Despite a studio reader discouraging a film adaptation of the material, McCormick passed the proof on to producers Lawrence Bender and Art Linson, who in turn also rejected it. Producers Josh Donen and Ross Bell then expressed interest in the project and arranged unpaid screen readings with actors, initially lasting six hours, to determine the length of a script. After cutting out sections to reduce the running time and recording the dialogue, Bell sent the book on tape to Laura Ziskin, head of the division Fox 2000, who after listening to the tape purchased the rights to Fight Club for $10,000.[1]

To adapt the story into a screenplay, Ziskin initially considered hiring Buck Henry; Ziskin thought that Fight Club was similar to The Graduate, which had been adapted by Henry. However, a new screenwriter, Jim Uhls, began lobbying Donen and Bell to be hired to adapt the screenplay and was subsequently chosen by the producers over Henry. For directing, Bell had four options in mind: Peter Jackson, Bryan Singer, Danny Boyle, and David Fincher. Bell considered Jackson the best choice and contacted the director, but Jackson was too busy filming The Frighteners (1996) in New Zealand. Singer received the book, but did not read it, while Boyle met with Bell and read the book, he ultimately pursued another project. Fincher, who had previously read the book and tried to buy the rights himself, talked with Ziskin about directing the film, but was hesitant to work with 20th Century Fox again after his bad experiences with the studio during Alien³ (1992). A meeting with Ziskin and studio head Bill Mechanic restored his relationship with the studio,[1] and in August 1997, 20th Century Fox announced that Fincher would helm the film adaptation of the novel.[2] Mechanic and Ziskin initially planned to finance the film with a $23 million budget.[1]

Casting

Producer Ross Bell met with actor Russell Crowe to discuss portraying Tyler Durden, while at the same time producer Art Linson, who had lately joined the project, was negotiating with Brad Pitt for the same role. Due to Linson's seniority, Pitt was cast over Crowe.[1] Pitt, who was seeking a new project after the failure of his previous film, Meet Joe Black (1998), was hired for $17.5 million, the studio believing that Fight Club would be more commercially successful with a major star.[3] Likewise for the role of the nameless narrator, the studio desired a "sexier marquee name" like Matt Damon to increase the film's visibility (Sean Penn was also considered), but Fincher sought to cast Edward Norton in that role, based on the actor's performance in The People vs. Larry Flynt (1996).[4] Norton had also been approached by other studios for leading roles in films like The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999) and Man on the Moon (1999), and he temporarily pursued Runaway Jury (2003) before that project fell apart. To lure him away from the other projects, Fox offered Norton a salary of $2.5 million, but Norton could not immediately accept, as he still owed Paramount Pictures a film. Norton therefore signed a new contract with Paramount for a lesser salary, eventually being contractually obligated to take a role in The Italian Job (2003).[3] In January 1998, Brad Pitt and Edward Norton officially joined the project to portray Tyler Durden and the nameless narrator, respectively.[5]

Actresses Courtney Love and Winona Ryder were considered to portray Marla Singer,[6] and the studio would have cast Reese Witherspoon were it not for Fincher's objections that the actress was too young.[3] Ultimately, Helena Bonham Carter was cast in the role, based on her performance in The Wings of the Dove (1997).[7]

To prepare for their roles, Norton and Pitt took lessons in boxing, taekwondo, and grappling,[8] in addition to soapmaking classes from boutique company owner Auntie Godmother.[9] For the cosmetics of his role, Pitt voluntarily visited a dentist to have pieces of his front teeth chipped off, which were restored after filming concluded.[10]

Writing

Screenwriter Jim Uhls began working on the adaptation from an earlier draft which lacked a voice-over due to the industry's perspective at the time that the technique was "hackneyed and trite". When Fincher joined the project, he disagreed with the approach, believing that the film's humor came from the narrator's voice,[3] and described the film without voice-over as seemingly "sad and pathetic".[11] The director and Uhls developed the script for six to seven months, creating a third draft by 1997 that reordered the story and left out several major elements. When Pitt came on board, the actor expressed concern that Tyler Durden was too one-dimensional, so Fincher sought the advice of writer-director Cameron Crowe, who suggested giving the character more ambiguity. Fincher also hired screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker and invited Pitt and Norton to collaborate on rewriting the script, which was completed after a year of work and five drafts.[3] The narrator was written to be nameless in the film, although he is identified in the script as Jack. The narrator's aliases in the support groups that he attends were based on characters from Planet of the Apes and Robert De Niro roles of the 1970s.[12]

Author Chuck Palahniuk praised the faithful film adaptation of his novel and applauded the fact that the plot of the film was more streamlined than that of the book. Palahniuk also noted the contention over the believability for film audiences of the novel's plot twist, the inclusion of which director David Fincher supported by saying, "If they accept everything up to this point, they'll accept the plot twist. If they're still in the theater, they'll stay with it." Palahniuk was, however, annoyed by the film's change of a single ingredient in its explanation on making napalm, which rendered the recipe useless, since the author had researched the components extensively.[13] Palahniuk's novel also contained homoerotic overtones, which the director deliberately included in the film in order to make audiences uncomfortable and thereby accentuate the surprise of the film's twists and turns.[14] The scene in which Tyler Durden bathes next to the narrator is an example of such overtones, although Durden's insight in the scene, "I'm wondering if another woman is really the answer we need," was meant to suggest personal responsibility rather than homosexuality.[15] Another example of the overtones was the scene at the beginning of the film in which Tyler Durden puts a gun barrel down the narrator's mouth.[16]

At the end of the film, the narrator finds redemption in rejecting Tyler Durden's dialectic, which is a divergence from the novel's end, in which the narrator is placed in a mental institution.[17] Norton notes the film's redemptive parallel to The Graduate, as the protagonists of both films find a middle ground between two divisions of self.[18] The director also considered the novel too infatuated with Tyler Durden and altered the ending to pull away from him, saying, "I wanted people to love Tyler, but I also wanted them to be OK with his vanquishing."[17]

Filming

When production first began, the initial $50 million budget, of which half was paid by New Regency, escalated to a peak of $67 million. New Regency's head and Fight Club executive producer Arnon Milchan petitioned Fincher to reduce the budget by at least $5 million, but the director refused to cut costs, so Milchan contacted studio head Bill Mechanic, saying that he would back out. To bring back Milchan's support, Mechanic sent him tapes of dailies, and after three weeks of shooting, Milchan returned his support and financed half of the production budget.[19]

Filming lasted 138 days,[20] during which Fincher shot more than 1,500 rolls of film, three times the average for a Hollywood film.[8] Filming locations were in and around Los Angeles and on sets built at the studio's location in Century City.[20] Production designer Alex McDowell constructed more than 70 sets.[8] The exterior of Tyler Durden's home on Paper Street was built in San Pedro, California, while the interiors, given a decayed look to reflect the deconstructed world of the characters, were built on a sound stage at the studio's location.[20] Marla's apartment was based on photographs of the Rosalind Apartments in downtown L.A.[11]

Fighting in the film was heavily choreographed, and fighters were required to "go full out" during fight scenes to capture realistic effects such as having the wind knocked out of oneself.[21] To enhance the scenes, makeup artist Julie Pearce, who collaborated with the director on The Game, studied mixed martial arts and pay-per-view boxing for her work on the fighters. She also designed an extra to have a chunk missing from his ear, for which she cited Mike Tyson's bite as inspiration.[22] To create sweat on cue, makeup artists devised two methods: spraying water over a coat of Vaseline, and using straight water for "wet sweat". Meat Loaf, who plays a member of the fight club who has "bitch tits", wore a 90-pound (40 kg) fat harness that gave him large breasts for the role.[8] He also wore eight-inch (20 cm) lifts in his scenes with Norton, being shorter than the lead actor.[15]

Overall production included 300 scenes, 200 locations, and complex special effects. Fincher compared Fight Club to his succeeding and less complex project Panic Room (2002), "I felt like I was spending all my time watching trucks being loaded and unloaded so I could shoot three lines of dialogue. There was far too much transportation going on."[23]

Cinematography

Fight Club was shot in the Super 35 format to give the director maximum flexibility in composing shots. To direct the cinematography for the film, director David Fincher hired Jeff Cronenweth, the son of the late cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth with whom Fincher had collaborated for Alien³ (1992). Fincher and Cronenweth drew from elements of the visual styles that Fincher had begun exploring in Se7en and The Game. For the narrator's scenes without Tyler Durden, the look was purposely bland and realistic, while for scenes with Tyler, Fincher chose a look that was "more hyper-real in a torn-down, deconstructed sense—a visual metaphor of what [the narrator is] heading into". Heavily desaturated colors were used in the costuming, makeup, and art direction, and the crew took advantage of as much natural and practical light at filming locations as possible. The director also took various approaches to take advantage of lighting situations in the film's scenes, and several practical locations were chosen for the city lights' effects on the shots' backgrounds. Fluorescent lighting at practical locations was also embraced to maintain an element of reality and to light the prosthetics of the characters' injuries appropriately.[20] On the other hand, Fincher also ensured that scenes were darkened enough to reduce the visibility of the characters' eyes, citing cinematographer Gordon Willis's technique as the influence.[15]

The majority of Fight Club was filmed at night, with daytime shots taking place in purposely shadowed locations. For the first scenes of the actual indoor fight club in Lou's basement, the area was lit by inexpensive work lamps to create a background glow. The director also chose to film fight scenes in the basement from a more objective view, purposely avoiding stylish camerawork and instead placing the camera in a fixed position. As the fight scenes in the film progressed, the camera moved from the point of view of a distant observer to that of the fighter.[20]

Scenes of Tyler Durden were staged to conceal the film's twist; the character was not filmed in two shots with a group of people, nor was he shown in any over the shoulder shots in scenes where Tyler gives the narrator specific ideas that are going to "lead him". Durden is also present in single frames of the narrator's scenes before the narrator actually meets Durden,[11] appearing in the background and out of focus, like a "little devil on the shoulder".[15] Regarding these subliminal frames, Fincher explained, "Our hero is creating Tyler Durden in his own mind, so at this point he exists only on the periphery of the narrator's consciousness."[24]

Visual effects

As visual effects supervisor, Kevin Tod Haug, who had collaborated with director David Fincher on The Game, divided the VFX artists and experts into different facilities, each responsible for addressing a separate aspect of the film's visual effects: CG modeling, animation, compositing, and scanning. According to Haug, "We selected the best people for each aspect of the effects work, then coordinated their efforts. In this way, we never had to play to a facility's weakness." Fincher chose to illustrate the nameless narrator's perspective with a "mind's eye" view and to create a myopic framework for the film's audience. Fincher also utilized previsualized footage of challenging main-unit and visual effects shots as a problem-solving tool to avoid making mistakes during the actual filming.[24]

The film's title sequence is a 90-second pullback scene from the fear center of the narrator's brain, representing the thought processes initiated by the narrator's fear impulse.[11] The sequence, designed in part by Fincher, was budgeted separately from the rest of the film, but the studio later paid for the sequence based on Fincher's expert direction of the film.[15] For the visual effects of the sequence, Fincher hired Digital Domain and its visual effects supervisor Kevin Mack, who had won an Academy Award for Visual Effects for What Dreams May Come (1998). The computer-generated brain was mapped using an L-system,[25] and the design was detailed using renderings by medical illustrator Kathryn Jones. The pullback sequence from within the brain to the outside of the skull included neurons, action potentials, and a hair follicle. Concerning the artistic license that Fincher took with the shot, Haug explained, "While he wanted to keep the brain passage looking like electron microscope photography, that look had to be coupled with the feel of a night dive—wet, scary, and with a low depth of field." The shallow depth of field was accomplished with the process of ray tracing.[24]

One of the earliest scenes in the film, in which the camera flashes past city streets to survey Project Mayhem's destructive equipment lying in underground parking lots, was a three-dimensional composition of nearly 100 photographs of Los Angeles and Century City by photographer Michael Douglas Middleton. The final scene of demolishing the credit card office buildings was designed by Richard Baily of Image Savant, who worked on the scene for over 14 months.[24]

The director gave a lurid style to the color palette of the film, choosing to make people "sort of shiny"; Helena Bonham Carter wore opalescent makeup to create a "smack-fiend patina" that would portray her romantic nihilistic character best. The director and cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth were also influenced by American Graffiti (1973), which applied a mundane look to nighttime exteriors while simultaneously including a variety of colors. When Fight Club was processed, several techniques were applied to alter the footage. The contrast was stretched to be purposely ugly, the print was adjusted to be underexposed, resilvering (lower-scale enhancement) was used to increase density, and high-contrast print socks were stepped all over the print to create a dirty patina.[11]

Fincher included the cue mark sequence, in which Durden points out the "cigarette burn" flash, to serve as a thematic element. The sequence represents a turning point, foreshadowing the coming rupture and inversion of the "fairly subjective reality" that characterizes the initial progression of the film. "Suddenly it's as though the projectionist missed the changeover, the viewers have to start looking at the movie in a whole new way," explained Fincher.[24]

Musical score

For the musical score, the director was concerned that bands experienced in performing film music would be unable to tie the movie's themes together, so for this reason, he sought a band which had never recorded for film before. Radiohead was pursued as a possible choice,[15] but the breakbeat producer duo Dust Brothers was ultimately chosen to score the film. The duo created a post-modern score that included drum loops, electronic scratches, and computerized samples because, as Dust Brothers performer Michael Simpson explains, "Fincher wanted to break new ground with everything about the movie, and a nontraditional score helped achieve that."[26]

Filmmakers' themes

Values

"I feel that Fight Club really, in a way... probed into the despair and paralysis that people feel in the face of having inherited this value system out of advertising."

Edward Norton[27]

Director David Fincher described Fight Club as a black comedy that applies heavy satire.[15] To avoid a potentially sinister nature, Fincher purposefully kept the film "funny and seditious",[17] while Norton described the film as a "dark, comic, sort of surrealist look" at young people's failures to interact with the value system of which they are expected to be a part.[28] Fight Club parallels Rebel Without a Cause by probing into the frustrations of the people that live in the system.[27] The characters, having undergone societal emasculation, are reduced to "a generation of spectators",[29] while a culture of advertising defines society's "external signifiers of happiness" and causes an unnecessary chase for material objects that replaces the more essential pursuit of spiritual happiness.[30] Pitt explained, "I think there's a self defense mechanism that keeps my generation from having any real honest connection or commitment with our true feelings. We're rooting for ball teams, but we're not getting in there to play. We're so concerned with failure and success—like these two things are all that's going to sum you up at the end."[21]

"Fight Club is a metaphor for the need to push through the walls we put around ourselves and just go for it, so for the first time we can experience the pain."

Brad Pitt[21]

The violence of the fight clubs serves as a metaphor for feeling, rather than to promote or glorify physical combat.[31] The fights are tangible representations of resisting the impulse to be cocooned in society.[29] Norton explained that the fighting between the men strips away the "fear of pain" and "the reliance on material signifiers of their self-worth", leaving them to really experience something valuable.[27] When the fights transform into revolutionary violence, the film only half-accepts this dialectic by Tyler Durden, with the narrator pulling back and rejecting Durden's ideas.[18] Thus Fight Club purposely shapes an ambiguous message, the interpretation of which is left to the film audiences.[32] As Fincher elaborated, "I love this idea that you can have fascism without offering any direction or solution. Isn't the point of fascism to say, 'This is the way we should be going'? But this movie couldn't be further from offering any kind of solution."[17]

Characters

In Fight Club, the nameless narrator is an everyman who lacks a world of possibilities and initially cannot find a way to change his life. The narrator finds himself unable to match society's requirements for happiness and so embarks on a path to enlightenment which involves metaphorically killing his parents, his God, and his teacher. At the beginning of the film, the narrator has killed off his parents but still finds himself trapped in his false world. The narrator then meets Tyler Durden, with whom he kills his metaphorical God by going against the norms of society. Ultimately, the narrator has to kill his teacher, Tyler Durden, to complete the process of maturity.[11]

Screenwriter Jim Uhls described the film as a "romantic comedy", explaining, "It has to do with the characters' attitudes toward a healthy relationship, which is a lot of behavior which seems unhealthy and harsh to each other, but in fact does work for them—because both characters are out on the edge psychologically."[33] In the film, the narrator seeks intimacy, but he avoids it at first with Marla Singer, seeing too much of himself in her.[15] Though Marla presents a seductive and negativist prospect for the narrator, he instead embraces the novelty and excitement that Tyler Durden has to offer him. The narrator finds himself comfortable having the personal connection to Tyler Durden, but he becomes jealous when Marla becomes sexually involved with Tyler. When the narrator argues with Tyler about their friendship, Tyler explains that the relationship between the two men is secondary to the active pursuit of the philosophy they had been exploring.[18] Tyler also suggests doing something about Marla, implying that she is a risk to be removed. When Tyler says this, the narrator realizes that his desires should have been focused on Marla and begins to diverge from Tyler's path.[15]

"We decided early on that I would start to starve myself as the film went on, while [Brad Pitt] would lift and go to tanning beds; he would become more and more idealized as I wasted away."

Edward Norton[34]

The unreliable narrator is not immediately aware that Tyler Durden is, in fact, himself,[11] and he also mistakenly promotes the fight clubs as a way to feel powerful.[28] Contrarily, the narrator's physical condition worsens while Tyler Durden's appearance improves. Although Tyler initially embarks on a journey with the narrator in desiring the "real experiences" of actual fights,[27] he eventually becomes a Nietzschean model that manifests the nihilistic attitude of rejecting and destroying institutions and value systems.[32] His impulsive nature, representing the id,[15] conveys an attitude that is seductive and liberating to the narrator and the followers. However, Tyler's initiatives and methods eventually become dehumanizing,[32] as when he orders around the members of Project Mayhem with a megaphone in similar fashion to the approach of Chinese re-education camps.[15] At this point, the narrator pulls back from Tyler and retreats as Tyler moves forward. In the end, the narrator is able to arrive at a middle ground between his two conflicting selves.[18]

Release

Marketing

In early 1999, after filming had concluded the previous December, David Fincher edited the footage to prepare Fight Club for a preliminary screening with senior executives. They did not receive the film positively, expressing concern that there would not be an audience that would watch it.[35] Executive producer Art Linson, who supported the film, recalled the response, "So many incidences of Fight Club were alarming, no group of executives could narrow them down."[36] Nevertheless, Fight Club was originally slated to be released in July 1999,[37] later changed to August 6, 1999. The studio further delayed the film's release, this time to autumn, due to a crowded summer schedule and a hurried post-production process,[38] although outsiders attributed the delays to the Columbine High School massacre earlier in the year.[39]

Marketing executives at Twentieth Century Fox faced difficulties in marketing Fight Club and at one point considered marketing it as an art film. Because of the film's violence, they considered it primarily geared toward male audiences and believed that not even the presence of Brad Pitt would attract female filmgoers. Research testing showed that the film appealed to teenagers. Fincher refused to let the posters and trailers focus on Brad Pitt and encouraged the studio to hire the advertising firm Wieden+Kennedy to devise a marketing plan. The firm came up with a bar of pink soap as the film's main marketing image, which was considered "a bad joke" by Fox executives. Fincher also released two early trailers in the form of faux public service announcements presented by Pitt and Norton which the studio considered as inappropriate introductions to the movie. Instead, the studio financed a $20 million large-scale campaign to provide a press junket, posters, billboards, and trailers for TV that highlighted the film's fight scenes. Fight Club was also advertised on cable during World Wrestling Federation broadcasts, which Fincher protested, believing that the placement created the wrong context for the film.[35] Linson believed that the "ill-conceived one-dimensional" marketing by marketing executive Robert Harper largely contributed to Fight Club's lukewarm box office performance.[40]

Theatrical run

The film held its world premiere at the 56th Venice International Film Festival on September 10, 1999.[41] The studio had hired the National Research Group to test screen the film, and the group had indicated that the film would gross between $13 million and $15 million for its opening weekend.[42] Fight Club commercially opened in the United States and Canada on October 15, 1999 and earned $11,035,485 in 1,963 theaters over the opening weekend,[43] placing it at the number one position for the weekend and ahead of Double Jeopardy and The Story of Us, a fellow weekend opener.[44] The gender mix of audiences for Fight Club, initially argued to be "the ultimate anti-date flick", was 61% male and 39% female, with 58% of audiences below the age of 21. Despite the top placement, its opening reception had fallen short of the studio's expectations,[45] and over the second weekend, Fight Club dropped 42.6% in revenue, earning $6,335,870.[46] The film, whose production budget was $63 million, went on to gross $37,030,102 during its theatrical run in the United States and Canada and earned $100,853,753 in theaters worldwide.[43] The underwhelming North American performance of Fight Club soured the relationship between studio head Bill Mechanic and media executive Rupert Murdoch, eventually leading to the resignation of Mechanic in June 2000.[47]

For the UK release of Fight Club on November 12, 1999, the British Board of Film Classification removed two scenes involving "an indulgence in the excitement of beating a (defenseless) man's face into a pulp" and awarded the film an 18 certificate, limiting the release to adult-only audiences in the UK. The BBFC did not censor any further, having considered and dismissed claims that Fight Club contained "dangerously instructive information" and could "encourage anti-social [behavior]". As the board noted, "The film as a whole is—quite clearly—critical and sharply parodic of the amateur fascism which in part it portrays. Its central theme of male machismo (and the anti-social behaviour that flows from it) is emphatically rejected by the central character in the concluding reels."[48] The scenes were restored in a two-disc DVD edition released in the UK in March 2007.[49]

Home media

The DVD for Fight Club was one of the first to be supervised by the film's director and was released in two editions.[50] Working on the DVD for Fight Club was a way for the director to finish his vision for the film. 20th Century Fox's senior vice president of creative development, Julie Markell, explained how the DVD packaging complemented the vision: "The film is meant to make you question. The package, by extension, tries to reflect an experience that you must experience for yourself. The more you look at it, the more you'll get out of it." The packaging was developed for two months by the studio.[51] The single-disc edition included a commentary track,[52] while the two-disc special edition included the commentary track, multiple behind-the-scenes clips, deleted scenes, trailers, public service announcements, the promotional music video "This is Your Life", Internet spots, still galleries, cast biographies, storyboards, and publicity materials.[53] When the two-disc special edition DVD was first released, it was physically packaged to look covered in brown cardboard wrapper. Markell elaborated, "We wanted the package to be simple on the outside, so that there would be a dichotomy between the simplicity of brown paper wrapping and the intensity and chaos of what's inside."[51] 20th Century Fox's vice president of marketing, Deborah Mitchell, described the design: "From a retail standpoint, [the DVD case] has incredible shelf-presence."[54]

Fight Club won the 2000 Online Film Critics Society Awards for Best DVD, Best DVD Commentary, and Best DVD Special Features,[55] while Entertainment Weekly ranked the film's two-disc edition number one in its 2001 list of "The 50 Essential DVDs", giving top ratings to the DVD's content and technical picture-and-audio quality.[56] In 2004, after the two-disc edition went out of print, the studio re-released it due to fans' requests.[57] The DVD was one of the largest-selling in the studio's history.[40] The film also grossed $55 million in video and DVD rentals.[58] With a lukewarm box office performance in the United States, a better performance in other territories overseas, and the highly successful DVD release, Fight Club generated a $10 million profit.[40]

Critical reception

"It touched a nerve in the male psyche that was debated in newspapers across the world."

When Fight Club premiered at the Venice International Film Festival, the film was fiercely debated by critics. The Ottawa Citizen reported, "Many loved and hated it in equal measures." Concerns were expressed that the film would incite copycat behavior like when A Clockwork Orange debuted in Britain nearly three decades previously.[60] While filmmakers called Fight Club "an accurate portrayal of men in the 1990s", critics called it "irresponsible and appalling". The Australian wrote, "After only one screening in Venice, Fight Club is shaping up to be the most contentious mainstream Hollywood meditation on violence since Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange."[61]

Janet Maslin of The New York Times praised Fincher's direction and editing of the film. She also noted that Fight Club carried a message of "contemporary manhood", and that, if not watched closely, the film could be misconstrued as an endorsement of violence and nihilism.[62] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times called Fight Club "visceral and hard-edged", as well as "a thrill ride masquerading as philosophy" that most audiences would not appreciate.[63] Ebert later acknowledged that the film was "beloved by most, not by me".[64] Jay Carr of The Boston Globe thought that the film began with an "invigoratingly nervy and imaginative buzz", but that it eventually became "explosively silly".[65] David Ansen of Newsweek described Fight Club as "an outrageous mixture of brilliant technique, puerile philosophizing, trenchant satire and sensory overload" and thought that the ending was too pretentious.[66]

Richard Schickel of Time described the director's mise en scène as dark and damp, noting, "It enforces the contrast between the sterilities of his characters' aboveground life and their underground one. Water, even when it's polluted, is the source of life; blood, even when it's carelessly spilled, is the symbol of life being fully lived. To put his point simply: it's better to be wet than dry." Schickel applauded the performances of Brad Pitt and Edward Norton, but he criticized the film's "conventionally gimmicky" unfolding and the failure to make Helena Bonham Carter's character interesting.[67]

Fight Club was nominated for the 2000 Academy Award for Sound Editing for Best Sound Editing, but it lost to The Matrix (1999).[68] Actress Helena Bonham Carter won the 2000 Empire Award for Best British Actress.[69] The Online Film Critics Society also nominated Fight Club for Best Film, Best Director, Best Actor (Edward Norton), Best Editing, and Best Adapted Screenplay (Uhls).[70] Though the film won none of the awards, the society listed Fight Club as one of the top ten films of 1999.[71] The soundtrack for Fight Club received a nomination for a BRIT Award, which it lost to Notting Hill.[72]

Cultural impact

Tyler Durden's recitation of the rules of fight club is considered one of the most quoted monologues in cinema:[73]

- The first rule of fight club is... you do not talk about fight club.

- The second rule of fight club is... you do not talk about fight club.

- Third rule of fight club, someone yells "Stop!", goes limp, taps out, the fight is over.

- Fourth rule, only two guys to a fight.

- Fifth rule, one fight at a time, fellas.

- Sixth rule, no shirts, no shoes.

- Seventh rule, fights will go on as long as they have to.

- And the eighth and final rule, if this is your first night at fight club, you have to fight.

Fight Club was considered one of the most controversial and talked-about films of 1999.[21][74] The film was perceived as the forerunner of a new mood in American political life. Like other 1999 films Magnolia, Being John Malkovich, and Three Kings, Fight Club was recognized as an innovator in cinematic form and style due to its exploitation of new developments in filmmaking technology.[75] Following its initial release, Fight Club grew in popularity via word of mouth,[76] and the positive reception of the DVD established it as a cult film that Newsweek conjectured would enjoy "perennial" fame.[77][78] The success of the film also propelled the novel's author Chuck Palahniuk to global renown.[79]

The film is often credited as having spawned fight clubs in America, however, according to Chuck Palahniuk, similar clubs and events already existed before the film's release and were part of the inspiration for the novel. A "Gentleman's Fight Club" was started in Menlo Park, California in 2000 and has members mostly from the high tech industry.[80] Teens and preteens in Texas, New Jersey, Washington state, and Alaska also initiated fight clubs and posted videos of their fights online, leading authorities to break up the clubs. In 2006, an unwilling participant from a local high school was injured at a fight club in Arlington, Texas, and the DVD sales of the fight led to the arrest of six teenagers.[81] An unsanctioned fight club was also started at Princeton University, and matches were held on campus.[82]

According to actor Edward Norton, one of his former professors from Yale University has reported being inundated with dissertations about Fight Club.[76] The film has also been used as an academic tool to introduce college students to rhetorical analysis and argumentation.[83]

In 2003, Fight Club was listed as one of the "50 Best Guy Movies of All Time" by Men's Journal.[84] In 2004 and 2006, Fight Club was voted by Empire readers as the ninth and eighth greatest film of all time, respectively,[85][86] while Total Film ranked Fight Club as "The Greatest Film of our Lifetime" in 2007 during the magazine's tenth anniversary.[87] In 2007, Premiere selected Tyler Durden's line, "The first rule of fight club is you do not talk about fight club," as the 27th greatest movie line of all time.[88] In 2008, UK readers of Empire ranked Tyler Durden at the number one position in a list of the 100 Greatest Movie Characters.[89]

References

- Linson, Art (2002). "Fight Clubbed". What Just Happened? Bitter Hollywood Tales from the Front Line. Bloomsbury USA. pp. 141–156. ISBN 1582342407.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Waxman, Sharon (2005). Rebels on the Backlot: Six Maverick Directors and How They Conquered the Hollywood Studio System. HarperEntertainment. ISBN 0060540176.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

Notes

- ^ a b c d Waxman, pp. 137–151.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (August 19, 1997). "Thornton holds reins of 'Horses'". Variety. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e Waxman, pp. 175–184.

- ^ Biskind, Peter (1999). "Extreme Norton". Vanity Fair.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Petrikin, Chris (January 7, 1998). "Studio Report Card: Fox". Variety. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Palahniuk: Marketing 'Fight Club' is 'the ultimate absurd joke'". CNN. October 29, 1999. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Johnson, Richard (1999). "Boxing Helena". Los Angeles Magazine.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Garrett, Stephen (1999). "Freeze Frame". Details.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Schneller, Johanna (1999). "Brad Pitt and Edward Norton make 'Fight Club'". Premiere.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Nashawaty, Chris (July 16, 1998). "Brad Pitt loses his teeth for a "Fight"". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g Smith, Gavin (1999). "Gavin Smith goes one-on-one with David Fincher". Film Comment.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "100 DVDs You Must Own". Empire: 31. 2003.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Interview With Fight Club Author Chuck Palahniuk". DVD Talk. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Hobson, Louis B. (October 10, 1999). "Fiction for real". Calgary Sun.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Fight Club DVD commentary featuring David Fincher, Brad Pitt, Edward Norton and Helena Bonham Carter, [2000], 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Schaefer, Stephen (October 13, 1999). "Fight Club's Controversial Cut". MrShowbiz.com. Retrieved December 2, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b c d Wise, Damon (1999). "Menace II Society". Empire.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Teasdall, Barbara (1999). "Edward Norton Fights His Way to the Top". Reel.com. Movie Gallery. Retrieved March 24, 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Waxman, pp. 199–202.

- ^ a b c d e Probst, Christopher (1999). "Anarchy in the U.S.A". American Cinematographer. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d "'Club' fighting for a respectful place in life". Post-Tribune. March 15, 2001.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "It Bruiser: Julie Pearce". Entertainment Weekly. July 25, 1999.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Covert, Colin (March 29, 2002). "Fear factor is Fincher's forte". Star Tribune.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e Martin, Kevin H. (2000). "A World of Hurt". Cinefex.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Frauenfelder, Mark (1999). "Hollywood's Head Case". Wired.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Schurr, Amanda (November 19, 1999). "Score one for musicians turned film composers". Sarasota Herald-Tribune.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d Schaefer, Stephen (1999). "Brad Pitt & Edward Norton". MrShowbiz.com. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b O'Connor, Robby (October 8, 1999). "Interview with Edward Norton". Yale Herald.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Hobson, Louis B. (October 10, 1999). "Get ready to rumble". Calgary Sun.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Slotek, Jim (October 10, 1999). "Cruisin' for a bruisin'". Toronto Sun.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Moses, Michael (1999). "Fighting Words: An interview with Fight Club director David Fincher". DrDrew.com. Dr. Drew. Retrieved May 13, 2009.

- ^ a b c Fuller, Graham (1999). "Fighting Talk". Interview. 24 (5): 1071–7. doi:10.1053/jhsu.1999.1281. PMID 10509287.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sragow, Michael (October 14, 1999). "Testosterama". Salon.com. Retrieved December 2, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Said, S.F. (April 19, 2003). "It's the thought that counts". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved April 30, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b Waxman, pp. 253–273.

- ^ Linson, pp. 152.

- ^ Svetkey, Benjamin (October 15, 1999). "Blood, Sweat, and Fears". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 30, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Klady, Leonard (June 17, 1999). "Fox holds the 'Fight' to fall". Variety. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Goodwin, Christopher (September 19, 1999). "The malaise of the American male". The Sunday Times.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c Linson, pp. 155.

- ^ Basoli, A. G. (September 18, 1999). "The Venice Diaries". indieWIRE.com. indieWIRE. Retrieved November 14, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Orwall, Bruce (October 25, 1999). "L.A. Confidential: Studios Move to Put A Halt on Issuing Box-Office Estimates". Wall Street Journal.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "Fight Club (1999)". Box Office Mojo. Box Office Mojo, LLC. Retrieved November 14, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Weekend Box Office Results for October 15-17, 1999". Box Office Mojo. Box Office Mojo, LLC. Retrieved November 14, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Hayes, Dade (October 18, 1999). "'Jeopardy' just barely". Variety. Retrieved March 23, 20072007-03-23.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ "Weekend Box Office Results for October 22-24, 1999". Box Office Mojo. Box Office Mojo, LLC. Retrieved November 14, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Lyman, Rick (June 26, 2000). "MEDIA TALK; Changes at Fox Studio End Pax Hollywood". The New York Times. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Dawtrey, Adam (November 9, 1999). "UK to cut 'Club'". Variety. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ French, Philip (March 4, 2007). "Fight Club". The Observer. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Kirsner, Scott (April 23, 2007). "How DVDs became a success". Variety. Retrieved April 28, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b Misek, Marla (2001). "For Fight Club and Seven, package makes perfect". EMedia Magazine. 14 (11): 27–28.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Fight Club". foxstore.com. 20th Century Fox. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Fight Club Special Edition". foxstore.com. 20th Century Fox. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Wilson, Wendy (June 12, 2000). "Fox's Fight Club delivers knockout package, promo". Video Business.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The OFCS 2000 Year End Awards". Online Film Critics Society. Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "The 50 Essential DVDs". Entertainment Weekly. January 19, 2001. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Cole, Ron (February 14, 2004). "Don't let Kurt Russell classic escape you". Battle Creek Enquirer. Gannett Company.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Bing, Jonathan (April 11, 2001). "'Fight Club' author books pair of deals". Variety. Retrieved May 1, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Christopher, James (September 13, 2001). "How was it for you?". The Times.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Gritten, David (September 14, 1999). "Premiere of Fight Club leaves critics slugging it out in Venice". The Ottawa Citizen.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Goodwin, Christopher (September 24, 1999). "The beaten generation". The Australian.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Maslin, Janet (October 15, 1999). "Film Review; Such a Very Long Way From Duvets to Danger". The New York Times. Retrieved April 30, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Ebert, Roger (October 15, 1999). "Fight Club". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Ebert, Roger (August 24, 2007). "Zodiac". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved April 30, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Carr, Jay (October 15, 1999). "'Fight Club' packs a punch but lacks stamina". Boston Globe.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Ansen, David (October 18, 1999). "A Fistful of Darkness". Newsweek.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Schickel, Richard (October 11, 1999). "Conditional Knockout". Time. Retrieved January 7, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "72nd Academy Awards (1999)". Academy Awards Database. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved March 24, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Sony Ericsson Empire Awards - 2000 Winners". Empire. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "1999 Year-End Award Nominees". Online Film Critics Society. Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved April 28, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "The OFCS 1999 Year End Awards". Online Film Critics Society. Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved April 28, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Brits 2000: The winners". BBC News Online. BBC News. March 3, 2000. Retrieved April 16, 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Shoot to Thrill: The stunning psychological thrillers that made David Fincher one of Hollywood's hottest directors". The Mail on Sunday. May 6, 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "'Fight Club' author Palahniuk to participate in academic conference at Edinboro University". Erie Times-News. March 26, 2001.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Pulver, Andrew (November 27, 2004). "Adaptation of the week No. 36 Fight Club (1999)". The Guardian. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b Wise, Damon (November 2, 2000). "Now you see it". The Guardian. Retrieved April 30, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Nick Nunziata (March 23, 2004). "The personality of cult". CNN. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Ansen, David (July 11, 2005). "Is Anybody Making Movies We'll Actually Watch In 50 Years?". Newsweek.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Flynn, Bob (March 29, 2007). "Fighting talk". The Independent.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Associated Press (May 29, 2006). "Fight club draws techies for bloody underground beatdowns". USA Today. Retrieved April 28, 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Rosenstein, Bruce (August 1, 2006). "Illegal, violent teen fight clubs face police crackdown". USA Today. Retrieved April 28, 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "At Princeton, no punches pulled". The Philadelphia Inquirer. June 6, 2001.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Duin, Julia (May 9, 2002). "Pop degrees". The Washington Times.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Dirks, Tim. "50 Best Guy Movies of All Time". Filmsite. AMC. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "The 100 Greatest Movies Of All Time". Empire: 96. 2004-01-30.

- ^ "The 201 Greatest Movies Of All Time". Empire: 98. January 2006.

- ^ "Ten Greatest Films of the Past Decade". Total Film: 98. 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "The 100 Greatest Movie Lines". Premiere. Retrieved May 13, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "The 100 Greatest Movie Characters - 1. Tyler Durden". Empire. Retrieved December 1, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)

Further reading

- Read Mercer Schuchardt, ed. (2008). You Do Not Talk About Fight Club: I Am Jack's Completely Unauthorized Essay Collection. Benbella Books. ISBN 1933771526.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

- Official site

- Fight Club at IMDb

- Fight Club at Rotten Tomatoes

- Fight Club at Box Office Mojo

- Fight Club at AllMovie

- Fight Club at Metacritic

- Anarchy in the USA at American Cinematographer

- doppelganger: exploded states of consciousness in fight club at Disinfo

- Fight Club : A Ritual Cure For The Spiritual Ailment Of American Masculinity

- Masculine Identity in the Service Class: An Analysis of Fight Club

- Script at IMSDB