Falkland Islands | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Desire the right" | |

| Anthem: God Save the Queen (official) Song of the Falklands [a] | |

Location of the Falkland Islands. | |

| Capital and largest city | Stanley |

| Official languages | English |

| Demonym(s) | Falkland Islander |

| Government | British Overseas Territory[b] |

• Monarch | Elizabeth II |

• Governor | Nigel Haywood[1] |

| Keith Padgett[2] | |

• Responsible Minister (UK) | Hugo Swire MP |

| Legislature | Legislative Assembly |

| Establishment | |

| 1833 | |

| 1841 | |

| 1981[c] | |

| 2002 | |

| 2009 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 12,173 km2 (4,700 sq mi) (162nd) |

• Water (%) | 0 |

| Population | |

• 2012 estimate | 2,932[3] (220th) |

• Density | 0.26/km2 (0.7/sq mi) (241st) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2007 estimate |

• Total | $164.5 million[4] (222nd) |

• Per capita | $55,400[4] (9th) |

| Gini (2010) | 34.17[5] medium (64th) |

| HDI (2010) | 0.874[6] very high (20th) |

| Currency | Falkland Islands pound[d] (FKP) |

| Time zone | UTC−3 (FKST[e]) |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | 500 |

| ISO 3166 code | FK |

| Internet TLD | .fk |

| |

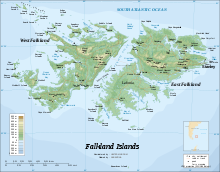

The Falkland Islands (/ˈfɔːlklənd/; Spanish: Islas Malvinas) are an archipelago located in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about 310 miles (500 kilometres) east of the Patagonian coast at a latitude of about 52°S. The archipelago which has an area of 4,700 square miles (12,173 square kilometres) comprises East Falkland, West Falkland and 776 smaller islands. As a British Overseas Territory, the islands enjoy a large degree of internal self-governance with the United Kingdom guaranteeing good government and taking responsibility for their defence and foreign affairs. The islands' capital is Stanley on East Falkland.

Controversy exists over the Falklands' original discovery and subsequent colonisation by Europeans. At various times, the islands have had French, British, Spanish, and Argentine settlements. Britain re-established its rule in 1833, though the islands continue to be claimed by Argentina. In 1982, following Argentina's invasion of the islands, the two-month-long undeclared Falklands War between both countries resulted in the surrender of all Argentine forces and the return of the islands to British administration.

The population, estimated at 2,932 in 2012, primarily consists of native Falkland Islanders, the majority of British descent. Other ethnicities include French, Gibraltarian, and Scandinavian. Immigration from the United Kingdom, Saint Helena, and Chile has reversed a former population decline. The predominant and official language is English. Under the British Nationality Act of 1983, Falkland Islanders are legally British citizens.

The islands lie on the boundary of the subarctic and temperate maritime climate zones with both major islands having mountain ranges reaching to 2,300 feet (700 m). The islands are home to large bird populations, although many no longer breed on the main islands due to the effects of introduced species. Major economic activities include fishing, tourism, and sheep farming with an emphasis on high-quality wool exports. Oil exploration, licensed by the Falkland Islands Government, remains controversial as a result of maritime disputes with Argentina.

Etymology

The Falkland Islands are named after the Falkland Sound, a strait that separates the archipelago's two main islands.[9] The name "Falkland" was applied to the channel by John Strong, the captain of an English expedition that landed on the islands in 1690. Strong named the strait in honor of Anthony Cary, 5th Viscount of Falkland, the Treasurer of the Navy who had sponsored the long journey.[10][11] The Viscount's title in turn comes from the town of Falkland, Scotland, whose name comes from the term "folkland" (meaning land held by folkright).[11] Nevertheless, the name would not be applied to the islands until 1765, when British admiral John Byron claimed them for King George III as "Falkland's Islands".[11][12]

The Spanish name for the archipelago, Islas Malvinas, comes from the French Îles Malouines, the name given to the islands by French explorer Louis-Antoine de Bougainville in 1764.[13] Bougainville, who founded the islands' first settlement, named the area after the port of Saint-Malo, the point of departure for his ships and colonists.[11][13] The port, located in the Brittany region of western France, was in turn named after St. Malo (or Maclou), the Christian evangelist who founded the city.[14]

The United Nations uses both the Spanish and English names "when referring to the islands";[15] its official designation for the territory is "Falkland Islands (Malvinas)".[16]

History

Before the Falklands War

Controversy exists as to who first discovered the Falkland Islands with competing Portuguese, Spanish, and British claims dating back to the 16th century.[17][18] While Amerindians from Patagonia could have visited the Falklands,[19] the islands were uninhabited when discovered by Europeans.[20] The first reliable sighting is usually attributed to the Dutch explorer Sebald de Weert in 1600, who named the archipelago the Sebald Islands, a name they bore on Dutch maps into the 19th century.[21]

In 1690, Captain John Strong of the Welfare en route to Puerto Deseado was driven off course and reached the Falkland Islands instead, landing at Bold Cove. Sailing between the two principal islands, he called the passage "Falkland Channel" (now Falkland Sound), after Anthony Cary, 5th Viscount Falkland, who as Commissioner of the Admiralty had financed the expedition. The island group takes its English name from this body of water.[22]

In 1764, French navigator and military commander Louis Antoine de Bougainville founded the first settlement on Berkeley Sound, in present-day Port Louis, East Falkland.[23] In 1765, British captain John Byron explored and claimed Saunders Island on West Falkland, where he named the harbour Port Egmont and a settlement was constructed in 1766.[24] Unaware of the French presence, Byron claimed the island group for King George III. Spain acquired the French colony in 1767, and placed it under a governor subordinate to the Buenos Aires colonial administration. In 1770, Spain attacked Port Egmont and expelled the British presence, bringing the two countries to the brink of war. War was avoided by a peace treaty and the British return to Port Egmont.[25]

In 1774, economic pressures leading up to the American Revolutionary War forced Great Britain to withdraw from many overseas settlements.[25][26] Upon withdrawal, the British left behind a plaque asserting Britain's continued claim. Spain maintained its governor until 1806 who, on his departure, left behind a plaque asserting Spanish claims. The remaining settlers were withdrawn in 1811.[25]

In 1820, storm damage forced the privateer Heroína to take shelter in the islands.[27] Her captain David Jewett raised the flag of the United Provinces of the River Plate and read a proclamation claiming the islands.[27] This became public knowledge in Buenos Aires nearly a year later after the proclamation was published in the Salem Gazette.[27] After several failures, Luis Vernet established a settlement in 1828 with authorisation from the Republic of Buenos Aires and from Great Britain.[28] In 1829, after asking for help from Buenos Aires, he was instead proclaimed Military and Civil Commander of the islands.[28] Additionally, Vernet asked the British to protect his settlement if they returned.[29]

A dispute over fishing and hunting rights resulted in a raid by the US warship USS Lexington in 1831.[30][31] The log of the Lexington reports only the destruction of arms and a powder store, but Vernet made a claim for compensation from the US Government stating that the settlement was destroyed.[30] (Compensation was rejected by the US Government of President Cleveland in 1885.) Lexington's Captain declared the islands "free from all government", and the seven senior members of the settlement were arrested for piracy[32] and taken to Montevideo,[31] where they were released without charge on the orders of Commodore Rogers.[33]

In November 1832, Argentina sent Commander Mestivier as an interim commander to found a penal settlement, but he was killed in a mutiny after four days.[34] The following January, British forces returned and requested the Argentine garrison leave. Don Pinedo, captain of the ARA Sarandi and senior officer present, protested but ultimately complied. Vernet's settlement continued, with the Irishman William Dickson[35] tasked with raising the British flag for passing ships.[36][37] Vernet's deputy, Matthew Brisbane, returned and was encouraged by the British to continue the enterprise. The settlement continued until August 1833, when the leaders were killed in the so-called Gaucho murders. Subsequently, from 1834 the islands were governed as a British naval station until 1840 when the British Government decided to establish a permanent colony.[38]

A new harbour was built in Stanley,[39] and the islands became a strategic point for navigation around Cape Horn. A World War I naval battle, the Battle of the Falkland Islands, took place in December 1914, with a British victory over the smaller Imperial German Asiatic Fleet.[40] During World War II, Stanley served as a Royal Navy station and serviced ships which took part in the 1939 Battle of the River Plate.[41]

Sovereignty over the islands again became an issue in the second half of the 20th century, when Argentina saw the creation of the United Nations as an opportunity to pursue its claim. Talks between British and Argentine foreign missions took place in the 1960s, but failed to come to any meaningful conclusion. A major sticking point in all the negotiations was that the inhabitants preferred that the islands remain British territory.[42]

A result of these talks was the establishment of the islands' first air link. In 1971, the Argentine state airline LADE began a service between Comodoro Rivadavia and Stanley. A temporary strip was followed by the construction of a permanent airfield and flights between Stanley and Comodoro Rivadavia continued until 1982.[43][44][45] Further agreements gave YPF, the Argentine national oil and gas company, a monopoly over the supply of the islands' energy needs.[46] The Times in its obituary of Rex Hunt states that it was generally accepted by the Foreign Office that when Hunt was appointed governor part of his brief was "to soften up the island's 1800 inhabitants to the idea that British sovereignty could not be taken as given in perpetuity". In his first dispatch back to the Foreign Office he wrote "There is no way we will convince these islanders that they will be better off as part of Argentina".[47]

Falklands War and its aftermath

On 2 April 1982, Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands and other British territories in the South Atlantic. By exploiting the long-standing feelings of Argentines towards the islands, the nation's ruling military junta sought to divert public attention from Argentina's poor economic performance and growing internal opposition.[48] The United Kingdom's reduction of military capacity in the South Atlantic is considered to have encouraged the invasion.[49][50][51]

On 3 April 1982, the United Nations Security Council issued Resolution 502, calling on Argentina to withdraw forces from the islands and for both parties to seek a diplomatic solution.[52] International reaction ranged from support for Argentina in most of Latin America, to opposition in the Commonwealth and most of Western Europe. Chile was the only Latin American country that provided overt support to the British by allowing ports of call and airport logistics. In contrast, Peru was the only Latin American country that provided war material to the Argentinian military, including Mirage aircraft, parts, and Exocet missiles. A divided United States administration, initially publicly neutral, eventually came out in support of the United Kingdom.[53][54]

The United Kingdom sent an expeditionary force to retake the islands. After short but fierce naval and air battles, the British forces landed at San Carlos Water on 21 May, and a land campaign followed leading to the British taking the high ground surrounding Stanley on 11 June. The Argentine forces surrendered on 14 June 1982. The war resulted in the deaths of 255 British and 649 Argentine soldiers, sailors and airmen, as well as 3 civilian Falklanders.[55]

After the war, the British increased their military presence on the islands, constructing RAF Mount Pleasant and increasing the military garrison.[56] Although the United Kingdom and Argentina resumed diplomatic relations in 1990, no further negotiations on sovereignty have taken place.[57] It is believed that 19,000 Argentine land mines[58][59] across an area of 13 square kilometres remain from the 1982 war dispersed in a number of minefields around Stanley, Port Howard, Fox Bay and Goose Green.[60] Information is available from the Explosive Ordnance Disposal Operation Centre in Stanley.[60] In 2009, mine clearance began at Surf Bay, and clearances took place at Sapper Hill, Goose Green and Fox Bay. Further clearance work was due to begin in 2011.[61]

Government

The Falkland Islands are a self-governing British Overseas Territory.[62] Under the 2009 Constitution, the islands have greater democratic autonomy, "while retaining sufficient powers for the UK Government to protect UK interests and to ensure the overall good governance of the territory".[63] The Monarch of the United Kingdom is the head of state, but executive authority is exercised on the monarch's behalf by the Governor of the Falkland Islands. The islands' Chief Executive, appointed by the Governor, is the head of government.[64] The islands' current Governor, Nigel Haywood, was appointed on October 2010;[1] the current Chief Executive, Keith Padgett, was appointed on March 2012.[2]

The Governor acts on the advice of the islands' Executive Council, composed by the Chief Executive, the Director of Finance, three elected members of the Legislative Assembly, and the Governor as chairman.[64] The Legislative Assembly, a unicameral legislature, consists of the Chief Executive, the Director of Finance, and eight members (five from Stanley and three from Camp) elected for four-year terms by universal suffrage.[64] All politicians in the Falkland Islands are independents; no political parties exist in the islands.[1]

The islands' judicial system, overseen by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, is largely based on English statutory law. Crime control and prisons are under the responsibility of the Royal Falkland Islands Police (RFIP).[65] Military defense of the islands is provided by the United Kingdom.[66] A British military garrison is stationed in the islands, and the Falkland Islands government funds an additional company-sized light infantry unit of defense.[67]

Sovereignty dispute

The United Kingdom and Argentina claim control over the Falkland Islands and its dependencies. The UK bases its position on continuous administration of the islands since 1833 (apart from 1982) and the islanders having a "right to self determination, including their right to remain British if that is their wish".[68] Argentina posits that it acquired the Falklands from Spain, upon achieving independence in 1816, and that the UK illegally occupied them in 1833.[69]

The present dispute began shortly after the passage, in 1960, of the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 1514 on decolonization. Argentina then reasserted its sovereignty claims "before the United Nations special committee for non-self-governing territories". In 1965, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 2065, which "called upon both Britain and Argentina to peacefully settle the dispute through bilateral negotiations".[70]

Later that decade, intending to improve its relations with South America by transferring the Falkland Islands (with provisions to protect the islanders' way of life), the United Kingdom secretly discussed the subject with Argentina. However, when the news became public, the Falklanders protested against the plans. As a result, the UK increased its focus on the Islanders' self-determination; Argentina disagreed, and negotiations effectively remained at a stalemate.[71][72] Subsequent talks between the two nations took place until 1981, but they failed to reach a conclusion on sovereignty.[73]

Diplomatic relations between the United Kingdom and Argentina, which were severed at the outbreak of the Falklands War in 1982, were re-established in 1990.[57] In 2007, Argentina reasserted its claim over the Falkland Islands, asking for the UK to resume talks on sovereignty.[74] In 2009, British prime minister Gordon Brown met with Argentine president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and declared that there would be no talks over the future sovereignty of the Falkland Islands.[75] As far as the United Kingdom and the Falkland Islands are concerned, no pending issue to resolve exists.[76][77][78]

Modern Falkland Islanders continue to reject the Argentine sovereignty claim. In 2010, Falklands correspondent Tom Leonard of The Daily Telegraph, wrote that "The 3,000-strong community is already proudly British [...]. The younger islanders may not share the older generation’s memories but there is clearly no love lost with the Argentines among them."[76] On 10 and 11 March 2013, the Falkland Islands held a referendum over its political status, and voters favoured (99.8%) remaining under British rule.[79][80]

Contemporary Argentine policy maintains the position that modern Falkland Islanders do not have a right to self-determination. Argentina claims that, in 1833, the UK expelled Argentine authorities and settlers from the Falklands with a threat of "greater force" and that the UK afterwards barred Argentines from resettling the islands.[69][81] Argentina reiterated its position towards the Falklanders in 2012, after a meeting of the UN Decolonization Committee, when its representatives refused to accept a letter from the Falkland Islands offering the opening of direct talks between both governments.[82] Moreover, in 2013, Argentina dismissed the Falkland Islands' sovereignty referendum. Argentina only recognises the UK government as a legitimate partner in negotiations;[83][84] and considers the islands, along with South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, as part of the Islas del Atlántico Sur department of Tierra del Fuego province.[85]

Geography

The Falkland Islands have a total land area of 4,700 square miles (12,173 square kilometres) and a coastline estimated at 800 miles (1,288 km).[86][87] Two main islands, West Falkland and East Falkland, and about 776 smaller islands comprise the archipelago.[86] The Falklands are continental crust fragments that resulted from "the break-up of Gondwana and the opening of the South Atlantic that began 130 million years ago". The islands are located in the South Atlantic Ocean, on the Patagonian Shelf, and 310 miles (500 kilometres) east of Patagonia in southern Argentina.[88]

The Falklands approximately lie at latitude 51°40′ - 53°00′ S and longitude 57°40′ - 62°00′ W.[87] The archipelago's two main islands are separated by the Falkland Sound,[89] and its deep coastal indentations form natural harbors.[90][91] East Falkland houses Stanley, the capital and largest city,[87] the U.K. military base at RAF Mount Pleasant, and the archipelago's highest point, Mount Usborne, at 2,313 feet (705 m).[89]

Land formations in the Falklands are predominantly mountainous and hilly,[90] with the major exception being the "low-lying" flat plains terrain of Lafonia, a peninsula forming the southern part of East Falkland.[92] Climate in the islands is usually "cold, windy, and humid maritime".[88] Rainfall is common "on more than half of days in [a] year", averaging 610 millimetres (24 in) in Stanley, and light snowfall occurs sporadically "throughout most of the year". Also prevalent on the islands are "strong westerly winds" and cloudy skies.[90]

Biodiversity

Biogeographically, the Falkland Islands are classified as part of the "mild" Antarctic zone.[93] Strong connections exist with the flora and fauna of Patagonia in mainland South America.[94] Land birds make up most of the Falklands' avifauna, followed by seabirds; a total of 63 species breed on the islands, including 16 endemic species.[95] Arthropod diversity in the islands is also abundant.[96] The Falklands' diverse flora has 163 native vascular species.[97] The islands' only endemic mammal, the warrah or Falkland Islands fox, was hunted to extinction by European settlers.[98]

The Falkland Islands are frequented by marine mammals such as the southern elephant seal and the South American fur seal. Offshore islands house the rare striated caracara. Fish endemic to the islands are mostly from the genus Galaxias.[96] The Falklands are "naturally treeless" and with a wind-resistant vegetation that, although varied, is "dominated by dwarf shrubs".[99]

Virtually the entire area of the islands is used as pasture for sheep.[4] Introduced species include reindeers, hares, rabbits, Patagonian foxes, pigs, horses, brown rats, and cats.[100] The detrimental impact several of these species have caused to native flora and fauna has led authorities to contain, remove, or exterminate invasive species such as foxes, rabbits, and rats. Endemic land animals have been the most affected by introduced species.[101] The extent of human impact on the Falklands is currenty unclear due to little long-term data on habitat changes.[94]

Economy

The economy of the Falkland Islands is classified as the 222nd largest in the world by GDP (PPP), and ranks 9th in the globe by GDP (PPP) per capita.[4] Unemployment is currently at a 4.1% rate, and inflation was last calculated at a 1.2% rate in 2003.[4] Based on 2010 data, the islands have a very high Human Development Index of .874,[6] but a medium Gini coefficient for income inequality of 34.17.[5]

Economic development was historically advanced by ship resupplying and sheep farming for high-quality wool.[103][104] In the 1980s, while synthetic fibers and ranch underinvestment considerably hurt the sheep farming sector, the Falkland Islands government found a major source of profit through the establishment of an exclusive economic zone and the sale of fishing licenses to "anybody wishing to fish within this zone".[103] Since the end of the Falklands War in 1982, the islands' economic activity increasingly focused on oil field exploration and tourism.[105]

Recent years have seen the port city of Stanley regain the islands' economic focus along with an increase in population due to workers migrating from Camp.[106] Fear of dependence on the selling of fishing licenses, and threats from overfishing, illegal fishing, and fish market price fluctuations have increased interest on oil drilling as an alternative source of revenue. Nonetheless, exploration efforts have yet to find "exploitable reserves".[102]

Agriculture, primarily in the form of sheep farming and fishing, accounts for 95% of the Falkland Islands' gross domestic product, followed by industry and services at 5%.[107] Present development projects in education and sports have been funded by the Falklands government without aid from the United Kingdom.[103] The islands' major exports include wool, hides, venison, fish, and squid; its main imports include fuel, building materials, and clothing.[4]

Demographics

The Falkland Islands are a predominantly homogeneous society, with the majority of its inhabitants descending from the Scottish and Welsh immigrants who colonized the territory in 1833. This is likely the result of government policies which successfully reduced the number of non-British populations that also inhabited the archipelago.[108] Nevertheless, in recent times, immigration from the United Kingdom, Saint Helena, and Chile has "reversed a former gradual decline in the island population".[109] The legal term for having the right of residence is "belonging to the islands".[64] The passage of the British Nationality Act of 1983 provided Falkland Islanders with British citizenship.[108]

In the 2012 census, a majority of residents described their nationality as Falkland Islander (59%), followed by British (29%), Saint Helenian (9.8%), and Chilean (5.4%).[3] A small number of Argentines also reside in the islands.[A] The 2006 census showed some Falklands residents identified as descendants of French, Gibraltarians, and Scandinavians.[111] Despite that same census indicated that only a third of residents were born on the archipelago, some foreign-born residents "have become assimilated" with the local culture.[112]

The Falkland Islands are the least populated territory in South America. According to the 2012 census, the average daily population of the Falklands was 2,932 (excluding British Ministry of Defence personnel and families based at RAF Mount Pleasant).[B] Stanley, with a population of 2,121, is the most populated location in the archipelago, followed by Mount Pleasant (369 residents, mostly air base contractors), and Camp (351 people).[3]

Age distribution in the islands is skewed towards people of working age (20–60). Males outnumber females (53 to 47%) with the deviation being most prominent in the 20–60 age group.[111] In the 2006 census, most of the islanders identified themselves as being Christians (67.2%), followed by those who refused to answer or had no religious affiliation (31.5%). The remaining 1.3% (39 individuals) identified as adherents of other faiths.[111] The Falklands have three churches: the Church of England, the Roman Catholic Church, and the United Free Church.[68]

Education in the Falkland Islands, which follows the English system, is free and compulsory.[113] Primary education is available at Stanley, RAF Mount Pleasant (for children of service personnel), and at a number of rural settlements. Secondary education is only available in Stanley, which offers boarding facilities and 12 subjects to General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) level. Students aged 16 or older may study at colleges in England for their GCE Advanced Level or vocational qualifications. The Falkland Islands government pays for older students to attend higher education, usually in the United Kingdom.[113]

Culture

Falklands culture is fundamentally "based on the British culture brought with the settlers from the British Isles", though it has been partly influenced by the cultures of Hispanic South America.[109] Some terms and toponyms used by the islands' former Gaucho inhabitants are still commonly used in local speech.[115] The Falklands' predominant language is British English, and part of the population (2.5%) is Spanish-speaking.[109] According to naturalist Will Wagstaff, "the Falkland Islands are a very social place, and stopping for a chat is a way of life".[115]

The islands have two weekly newspapers, Teaberry Express and The Penguin News.[116] Television and radio broadcasts generally feature programming from the United Kingdom.[109] Wagstaff describes local cuisine as "very British in character with much use made of the homegrown vegetables, local lamb, mutton, beef, and fish". Common between meals are "home made cakes and biscuits with tea or coffee".[117] Moreover, social activities in the Falklands are, in the words of Wagstaff, "typical of that of a small British town with a variety of clubs and organisations covering many aspects of community life".[118]

See also

Notes

References

- ^ a b c Central Intelligence Agency 2011, p. "Falkland Islands (Malvinas) - Government".

- ^ a b "Keith Padgett, first Falklands' government CE recruited in the Islands". MercoPress. 7 March 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Falkland Islands Census 2012: Headline results" (PDF). Falkland Islands Government. 10 September 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f "Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas)". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ a b Avakov 2013, p. 54.

- ^ a b Avakov 2013, p. 47.

- ^ "Falkland Islands will remain on summer time throughout 2011". MercoPress. 31 March 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ Joshua Project. "Ethnic People Groups of Falkland Islands". Joshua Project. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- ^ Jones 2009, p. 73.

- ^ Dotan 2010, p. 165.

- ^ a b c d Room 2006, p. 129.

- ^ Paine 2000, p. 45.

- ^ a b Hince 2001, p. 121.

- ^ Balmaceda 2011, p. Chapter 36.

- ^ Osmańczyk 2003, p. 1373.

- ^ "Standard Country and Area Codes Classifications". United Nations Statistics Division. 13 February 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ^ "Who first owned the Falkland Islands?". The Guardian. 2 February 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ Goebel, 1971, pp. xiv–xv

- ^ G. Hattersley-Smith (1983). "Fuegian Indians in the Falkland Islands". Polar Record. 21 (135). Cambridge University Press: 605–606. doi:10.1017/S003224740002204X. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Culture of Falkland Islands – history, people, clothing, beliefs, food, life, immigrants, population, religion". Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Goebel, 1971, pp. 45–46

- ^ "The Discovery of the Falkland Islands". Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Goebel, 1971, pp. 226

- ^ Goebel, 1971, pp. 232,269

- ^ a b c "A brief history of the Falkland Islands Part 2 – Fort St. Louis and Port Egmont". Falklands.info. Retrieved 8 September 2007.

- ^ "Falkland Islands Timeline: A chronology of events in the history of the Falkland Islands". Falklands.info. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- ^ a b c Tatham, 2008, pp. 308–309

- ^ a b Peter Pepper, Graham Pascoe (2008). "Luis Vernet". In David Tatham (ed.). The Dictionary of Falklands Biography (Including South Georgia): From Discovery Up to 1981. D. Tatham. pp. 540–546. ISBN 978-0-9558985-0-1.

- ^ Mary Cawkell (2001). The history of the Falkland Islands. Anthony Nelson. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-904614-55-8. "On this visit he met Woodbine Parish who expressed great interest in his venture and asked Vernet to prepare a full report on the islands to submit to the British government. On his side Vernet expressed the wish that, in the event of the British returning to the islands, HMG would take his settlement under their protection."

- ^ a b Peter Pepper, Graham Pascoe (2008). "Luis Vernet". In David Tatham (ed.). The Dictionary of Falklands Biography (Including South Georgia): From Discovery Up to 1981. D. Tatham. pp. 541–544. ISBN 978-0-9558985-0-1.

- ^ a b "A brief history of the Falkland Islands Part 3". Falklands.info. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ^ "Silas Duncan and the Falklands' Incident". USS Duncan Reunion Association. 2001. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

The letters show that the USS Lexington, under the command of Silas Duncan, visited the Falklands in December, 1831, to investigate complaints by American fishermen that a "band of pirates" was operating from the islands. After finding what he considered proof that at least four American fishing ships had been captured, plundered, and even outfitted for war, Duncan took seven prisoners aboard Lexington and charged them with piracy. The leaders of the prisoners was Louis Vernet, a German, and Matthew Brisbane, an Englishman both of Buenos Aries.

- ^ Tatham, 2008, pp. 117

- ^ "Historical Dates". Falkland Islands Government. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ^ Edmundo Murray (1 November 2005). "The Irish in Falkland/Malvinas Islands". Society for Irish Latin American Studies. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ^ Charles Darwin in the Falklands, 1833 (Extracts from Darwin's Diary)

- ^ "Darwin's Beagle Diary (1831–1836)". The Complete Works of Charles Darwin Online. p. 304. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ Lewis, Jason. "A Brief History of the Falkland Islands, Part 4 – The British Colonial Era". Retrieved 2 September 2011.

In 1839 a British merchant adventurer, G.T. Whittington, formed the Falkland Islands Commercial Fishery and Agricultural Association and tried to put pressure on the British government to proceed with the colonisation of the Falkland Islands. He published a leaflet entitled 'The Falkland Islands' containing material acquired indirectly from Vernet, and then presented to the government a petition signed by owner a hundred London merchants, shipowners and traders demanding that a public meeting be held to discuss the future of the Falkland Islands. In April 1840 he wrote to the Colonial Secretary, Lord Russell, proposing that the islands be colonised by his Association. In May the Colonial Land and Emigration Commissioners decided that the Falkland Islands were suitable for colonisation.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Tatham, 2008, pp. 382

- ^ Tatham, 2008, pp. 510–511

- ^ "CHAPTER 4 — The Battle of the River Plate". New Zealand Electronic Texts Centre. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ "A Brief History of the Falkland Islands Part 5 – The Argentine Claim". Falklands.info. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ "Líneas Aéreas Del Estado, LADE" (in Spanish). Argentine National Congress, Chamber of Deputies. 25 August 2006. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- ^ "Grumman HU-16B Albatross" (in Spanish). Asociación Tripulantes de Transporte Aéreo. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- ^ "Fokker F-27 Troopship y Friendship" (in Spanish). Asociación Tripulantes de Transporte Aéreo. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- ^ Lewis, Jason. "A Brief History of the Falkland Islands, Part 5 – The Argentine Claim". Retrieved 2 September 2011.

In 1974 Britain and Argentina agreed that the islands would be supplied with petrol, diesel and oil by YPF, the Argentine State Oil Company, at mainland rates. Again, Islanders objected, increasingly uncomfortable at their economic dependence on Argentina.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Obituaries: Sir Rex Hunt". The Times. London. 13 November 2012. p. 53.

- ^ "Las convocatorias nacionales de la última dictadura" (PDF) (in Spanish). Ministerio de Educación, Ciencia y Tecnología de la Nación. 18 September 2006. p. 6. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- ^ "Guide to the conflict". Fight for the Falklands—20 years on. BBC News. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

The Foreign Secretary, Lord Carrington, and two junior ministers had resigned by the end of the week [following the Argentine invasion]. They took the blame for Britain's poor preparations and plans to decommission HMS Endurance, the Navy's only Antarctic patrol vessel. It was a move which may have lead [sic] the Junta to believe the UK had little interest in keeping the Falklands.

- ^ "Secret Falklands fleet revealed". BBC News. 1 June 2005. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

Lord Owen, who was foreign secretary in 1977, said that if Margaret Thatcher's Conservative government had taken similar action to that of five years earlier, the war would not have happened.

- ^ Casciani, Dominic (29 December 2006). "1976 Falklands invasion warning". BBC News. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

The Franks Report into the eventual war noted that as tension mounted during 1977, the government covertly sent a small naval force to the islands—but did not repeat the move when relations worsened again in 1981–2. This has led some critics to blame prime minister Margaret Thatcher for the war, saying the decision to plan the withdrawal of the only naval vessel in the area sent the wrong signal to the military junta in Buenos Aires.

- ^ "UN Resolution 502". Historycentral.com. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ^ "The Falklands Roundtable" (PDF). Miller Center, University of Virginia. 16 May 2003. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ^ Gold, Peter (2005). Gibraltar, British or Spanish?. Routledge. p. 39. ISBN 0-415-34795-5.

- ^ "Falklands 25: Background Briefing". Defence Factsheet. United Kingdom Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ "Guide to the conflict". Fight for the Falklands – Twenty Years On. BBC News. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- ^ a b "Argentina and the Falkland Islands" (PDF). House of Commons Library. 22 June 2010. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ [1] Falklands' land mine clearance set to enter a new expanded phase in early 2012, Mercopress, 8 December 2011

- ^ "Falklands recover 370 hectares of Stanley Common made minefields in 1982 by Argentine forces". web page. Merco Press, Montevideo. 17 May 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ a b "Falklands/Malvinas". Landmine & Cluster Munition Monitor. International Campaign to Ban Landmines. 19 September 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2010.

- ^ "Falklands' minefield clearance next phase moves to the capital Stanley Common". Mercopress. 12 February 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2011.

- ^ Cahill 2010, p. "Falkland Islands".

- ^ "New Year begins with a new Constitution for the Falklands". MercoPress. 1 January 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d "The Falkland Islands Constitution Order 2008" (PDF). The Queen in Council. 5 November 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ Sainato 2010, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency 2011, p. "Falkland Islands (Malvinas) - Transportation".

- ^ Fletcher, Martin (6 March 2010). "Falklands Defence Force better equipped than ever, says commanding officer". The Times. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ a b "Falkland Islands (British Overseas Territory)". Travel & living abroad. United Kingdom Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ a b "Argentina's Position on Different Aspects of the Question of the Malvinas Islands". Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores.

- ^ Laver 2001, p. 125.

- ^ Chenette, Richard D (4 May 1987). "The Argentine Seizure Of The Malvinas [Falkland] Islands: History and Diplomacy". Marine Corps Staff and Command College.

- ^ Bound, Graham. Falkland Islanders at War, Pen & Swords Ltd, 2002 ISBN 1-84415-429-7

- ^ UK held secret talks to cede sovereignty. The Guardian. 28 June 2005. Retrieved on 20 November 2011.

- ^ "Argentina Reasserts Claim to Falkland Islands". VOA News. Voice of America. 3 January 2007. Retrieved 3 January 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "No talks on Falklands, says Brown". BBC News. 28 March 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ a b Leonard, Tom (22 February 2010). "Falkland Islands: Argentina can't scare us, say islanders". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ Watt, Nicholas (28 March 2009). "Falkland Islands sovereignty talks out of the question, says Gordon Brown". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 29 April 2009.

- ^ "Falkland Islands Government Overview". Falkland Islands Government. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ^ "Falklands referendum: Islanders vote on British status". BBC. 10 March 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ^ Brindicci and Bustamante, Marcos and Juan (12 March 2013). "Falkland Islanders vote overwhelmingly to keep British rule". Reuters. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ Reisman, W. Michael (1983). The struggle for the Falklands. The Yale Law Journal. p. 306.

- ^ [2] Summers invites Argentina to sit down and enter into a dialogue with the people of the Falklands

- ^ "Falkland Islands: respect overwhelming 'yes' vote, Cameron tells Argentina". The Guardian. 12 March 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ "Canciller argentino no acepta carta de los isleños". Terra. 14 June 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ^ Ley Provincial (1990), Provincia de Tierra del Fuego, Antártida e Islas del Atlántico Sur

- ^ a b Sainato 2010, p. 157.

- ^ a b c Guo 2007, p. 112.

- ^ a b Klügel 2009, p. 66.

- ^ a b Hemmerle 2005, p. 318.

- ^ a b c Central Intelligence Agency 2011, p. "Falkland Islands (Malvinas) - Geography".

- ^ Blouet & Blouet 2009, p. 100.

- ^ Trewby 2002, p. 79.

- ^ Jónsdóttir 2007, pp. 84–86.

- ^ a b Otley, Helen; Munro, Grant; Clausen, Andrea; Ingham, Becky (May 2008). "Falkland Islands State of the Environment Report 2008" (PDF). Environmental Planning Department Falkland Islands Government. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ Clark & Dingwall 1985, p. 131.

- ^ a b Clark & Dingwall 1985, p. 132.

- ^ Clark & Dingwall 1985, p. 129.

- ^ Hince 2001, p. 370.

- ^ Jónsdóttir 2007, p. 85.

- ^ Bell 2007, p. 544.

- ^ Bell 2007, pp. 542–545.

- ^ a b Royle 2001, p. 171.

- ^ a b c Royle 2001, p. 170.

- ^ Calvert 2004, p. 134.

- ^ Hemmerle 2005, p. 319.

- ^ Royle 2001, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency 2011, p. "Falkland Islands (Malvinas) - Economy".

- ^ a b Laver 2001, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d Minahan 2013, p. 139.

- ^ "Falklands Referendum: Voters from many countries around the world voted Yes". MercoPress. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ a b c "Falkland Islands Census Statistics, 2006" (PDF). Falkland Islands Government. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ "Falklands questions answered". BBC News. 4 June 2007. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ a b "Education". Falkland Islands Government. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ The date of this picture is unknown, but the artist, Lt Lowcay, was the offical British resident in the islands from 1838 to 1839 (see "Part 33 - Louis Vernet: The Great Entrepreneur". A Brief History of the Falkland Islands. Falklands.info. Retrieved 28 November 2012.).

- ^ a b Wagstaff 2001, p. 21.

- ^ Wagstaff 2001, p. 66.

- ^ Wagstaff 2001, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Wagstaff 2001, pp. 65.

Bibliography

- Avakov, Alexander (2013). Quality of Life, Balance of Powers, and Nuclear Weapons. New York: Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-963-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Balmaceda, Daniel (2011). Historias Inesperadas de la Historia Argentina (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana. ISBN 978-950-07-3390-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Bell, Brian (2007). Beau Riffenburgh (ed.). Introduced Species. Vol. 1. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-97024-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|encyclopedia=ignored (help)

- Blouet, Brian; Blouet, Olwyn (2009). Latin America and the Caribbean. Hoboken, New Jersey, USA: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-470-38773-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Cahill, Kevin (2010). Who Owns the World: The Surprising Truth About Every Piece of Land on the Planet. New York: Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-0-446-55139-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Calvert, Peter (2004). A Political and Economic Dictionary of Latin America. London: Europa Publications. ISBN 0-203-40378-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Central Intelligence Agency (2011). The CIA World Factbook 2012. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-1-61608-332-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Clark, Malcolm; Dingwall, Paul (1985). Conservation of Islands in the Southern Ocean. Cambridge: IUCN. ISBN 2-88032-503-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Doltan, Yossi (2010). Watercraft on World Coins: America and Asia, 1800-2008. Vol. 2. Portland: The Alpha Press. ISBN 978-1-898595-50-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Guo, Rongxing (2007). Territorial Disputes and Resource Management. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-1-60021-445-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Heawood, Edward (2011). F.H.H. Guillemard (ed.). A History of Geographical Discovery in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Reprint ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-60049-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Hemmerle, Oliver Benjamin (2005). R.W. McColl (ed.). Falkland Islands. Vol. 1. New York: Golson Books, Ltd. ISBN 0-8160-5786-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|encyclopedia=ignored (help)

- Hince, Bernadette (2001). The Antarctic Dictionary. Collingwood: CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 0-9577471-1X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Jones, Roger (2009). What's Who? A Dictionary of Things Named After People and the People They are Named After. Leicester: Matador. ISBN 978-1848760-479.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Jónsdóttir, Ingibjörg (2007). Jorge Rabassa; Maria Laura Borla (eds.). Botany during the Swedish Antarctic Expedition 1901-1903. Leiden: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-41379-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|encyclopedia=ignored (help)

- Klügel, Andreas (2009). Rosemary Gillespie; David Clague (eds.). Atlantic Region. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25649-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|encyclopedia=ignored (help)

- Laver, Roberto (2001). The Falklands/Malvinas Case. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 90-411-1534-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Minahan, James (2013). Ethnic Groups of the Americas. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-163-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Osmańczyk, Edmund (2003). Anthony Mango (ed.). Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements. Vol. 2 (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415939224.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Paine, Lincoln (2000). Ships of Discovery and Exploration. New York: Mariner Books. ISBN 0-395-98415-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Room, Adrian (2006). Placenames of the World (2nd ed.). Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 0-7864-2248-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Royle, Stephen (2001). A Geography of Islands: Small Island Insularity. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-16036-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Sainato, Vincenzo (2010). Graeme Newman; Janet Stamatel; Hang-en Sung (eds.). Falkland Islands. Vol. 2. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-35133-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|encyclopedia=ignored (help)

- Trewby, Mary (2002). Antarctica: An Encyclopedia from Abbott Ice Shelf to Zooplankton. Richmond Hill: Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-552-97590-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Wagstaff, William (2001). Falkland Islands: The Bradt Travel Guide. Buckinghamshire: Bradt Travel Guides, Ltd. ISBN 1-84162-037-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Julius Goebel (August 1971). The struggle for the Falkland Islands: a study in legal and diplomatic history. Kennikat Press. ISBN 978-0-8046-1390-3. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- David Tatham (1 June 2008). The Dictionary of Falklands Biography (Including South Georgia): From Discovery Up to 1981. D. Tatham. ISBN 978-0-9558985-0-1. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

Further reading

- Darwin, Charles (1846). On the Geology of the Falkland Islands (PDF). Vol. 2. pp. 267–274. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1846.002.01-02.46. Retrieved 9 March 2013

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - L.L. Ivanov et al. The Future of the Falkland Islands and Its People. Sofia: Manfred Wörner Foundation, 2003. Printed in Bulgaria by Double T Publishers. 96 pp. ISBN 954-91503-1-3.

- Template:Es icon Carlos Escudé and Andrés Cisneros, eds. Historia de las Relaciones Exteriores Argentinas. Work developed and published under the auspices of the Argentine Council for International Relations (CARI). Buenos Aires: GEL/Nuevohacer, 2000. ISBN 950-694-546-2.

- Pascoe, Graham; Pepper, Peter (May 2008). "False Falklands History at the United Nations - How Argentina misled the UN in 1964 – and still does" (PDF). Falklands History. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- Thoughts on the Late Transactions Respecting Falkland's Islands by Samuel Johnson, 1771.

- Greig, D.W. Sovereignty and the Falkland Islands Crisis. Australian Year Book of International Law. Vol. 8 (1983). pp. 20–70. ISSN: 0084-7658.

- César Caviedes. Conflict Over The Falkland Islands: A Never-Ending Story? Latin American Research Review. Vol. 29 (1994) No. 2. pp. 172–187.

External links

Wikimedia Atlas of Falkland Islands

Wikimedia Atlas of Falkland Islands Falkland Islands travel guide from Wikivoyage

Falkland Islands travel guide from Wikivoyage- "Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas)". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- Falkland Islands at Curlie

- Falkland Islands Government (official site).

- The Falkland Islands Tourist Board

- Falkland Islands Tourism

- Falkland Islands Development Corporation (official site).

- Falkland Islands News Network (official site).

- Falkland Islands Information Portal

- "Historical Dates". The Falkland Islands Government. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- Lewis, Jason. "A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE FALKLAND ISLANDS, Part 2 – Fort St. Louis and Port Egmont". Falkland Islands Information Portal. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Lewis, Jason. "FALKLAND ISLANDS TIMELINE A Chronology of events in the history of the Falkland Islands". Falkland Islands Information Portal. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)