John of Reading (talk | contribs) |

added Category:Mid-century modern using HotCat |

||

| Line 137: | Line 137: | ||

[[Category:Deaths from cancer in Michigan]] |

[[Category:Deaths from cancer in Michigan]] |

||

[[Category:Yale School of Architecture alumni]] |

[[Category:Yale School of Architecture alumni]] |

||

[[Category:Mid-century modern]] |

|||

Revision as of 10:38, 22 June 2017

Eero Saarinen | |

|---|---|

| File:Eero Saarinen.jpg Eero Saarinen | |

| Born | August 20, 1910 |

| Died | September 1, 1961 (aged 51) Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S. |

| Nationality | Finnish, American |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards | AIA Gold Medal (1962) |

| Buildings | See list of works |

| Design | Gateway Arch Washington Dulles International Airport TWA Flight Center Tulip chair |

Eero Saarinen (Finnish pronunciation: [ˈeːro ˈsɑːrinen]) (August 20, 1910 – September 1, 1961) was a 20th-century Finnish American architect and industrial designer noted for his neofuturistic style.

Early life and education

Eero Saarinen was born on August 20, 1910 to Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen and his second wife, Louise, on his father's 37th birthday.[1][2] They immigrated to the United States in 1923, when Eero was thirteen.[1][2] He grew up in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, where his father taught and was dean of the Cranbrook Academy of Art, and he took courses in sculpture and furniture design there.[citation needed] He had a close relationship with fellow students Charles and Ray Eames, and became good friends with Florence Knoll (née Schust).[3]

Saarinen began studies in sculpture at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris, France, in September 1929.[3] He then went on to study at the Yale School of Architecture, completing his studies in 1934.[4][better source needed] Subsequently, he toured Europe and North Africa for a year and returned for a year to his native Finland.[5]

Architectural career

After his tour of Europe and North Africa, Saarinen returned to Cranbrook to work for his father and teach at the academy.[citation needed] The firm was "Saarinen, Swansen and Associates", headed by Eliel Saarinen and Robert Swansen from the late 1930s until Eliel's death in 1950.[citation needed] The firm was located in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, until 1961 when the practice was moved to Hamden, Connecticut.[citation needed]

Saarinen first received critical recognition, while still working for his father, for a chair designed together with Charles Eames for the "Organic Design in Home Furnishings" competition in 1940, for which they received first prize. The "Tulip Chair", like all other Saarinen chairs, was taken into production by the Knoll furniture company, founded by Hans Knoll, who married Saarinen family friend Florence (Schust) Knoll. Further attention came also while Saarinen was still working for his father, when he took first prize in the 1948 competition for the design of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, St. Louis, not completed until the 1960s. The competition award was mistakenly sent to his father.

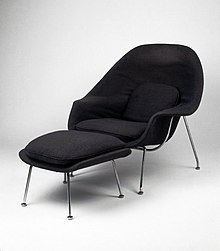

During his long association with Knoll he designed many important pieces of furniture including the "Grasshopper" lounge chair and ottoman (1946),[citation needed] the "Womb" chair and ottoman (1948),[6] the "Womb" settee (1950),[citation needed] side and arm chairs (1948–1950),[citation needed] and his most famous "Tulip" or "Pedestal" group (1956), which featured side and arm chairs, dining, coffee and side tables, as well as a stool.[citation needed] All of these designs were highly successful except for the "Grasshopper" lounge chair, which, although in production through 1965, was not a big success.[citation needed]

One of Saarinen's earliest works to receive international acclaim is the Crow Island School in Winnetka, Illinois (1940).[citation needed] The first major work by Saarinen, in collaboration with his father, was the General Motors Technical Center in Warren, Michigan, which follows the rationalist design Miesian style, incorporating steel and glass, but with the added accent of panels in two shades of blue.[citation needed] The GM Technical Center was constructed in 1956, with Saarinen using models, which allowed him to share his ideas with others, and gather input from other professionals.[citation needed]

With the success of the scheme, Saarinen was then invited by other major American corporations such as John Deere, IBM, and CBS to design their new headquarters or other major corporate buildings. Despite their rationality, however, the interiors usually contained more dramatic sweeping staircases, as well as furniture designed by Saarinen, such as the Pedestal Series.[7] In the 1950s he began to receive more commissions from American universities for campus designs and individual buildings; these include the Noyes dormitory at Vassar, Hill College House at the University of Pennsylvania, as well as an ice rink, Ingalls Rink, Ezra Stiles & Morse Colleges at Yale University, the MIT Chapel and neighboring Kresge Auditorium at MIT and the University of Chicago Law School building and grounds.[citation needed]

Saarinen served on the jury for the Sydney Opera House commission in 1957 and was crucial in the selection of the now internationally known design by Jørn Utzon.[8] A jury which did not include Saarinen had discarded Utzon's design in the first round; Saarinen reviewed the discarded designs, recognized a quality in Utzon's design, and ultimately assured the commission of Utzon.[8]

After his father's death in July 1950, Saarinen founded his own architect's office, "Eero Saarinen and Associates".[citation needed] He was the principal partner from 1950 until his death in 1961. Under Eero Saarinen, the firm carried out many of its most important works, including the Bell Labs Holmdel Complex in Holmdel Township, New Jersey, Jefferson National Expansion Memorial (including the Gateway Arch) in St. Louis, Missouri, the Miller House in Columbus, Indiana, the TWA Flight Center at John F. Kennedy International Airport that he worked on with Charles J. Parise, the main terminal of Dulles International Airport near Washington, D.C.[citation needed], the new East Air Terminal of Athens airport which opened in 1967 etc. Many of these projects use catenary curves in their structural designs.[citation needed]

One of the best-known thin-shell concrete structures in America is the Kresge Auditorium (MIT), which was designed by Saarinen. Another thin-shell structure that he created is Yale's Ingalls Rink, which has suspension cables connected to a single concrete backbone and is nicknamed "the whale". Undoubtedly, his most famous work is the TWA Flight Center, which represents the culmination of his previous designs and demonstrates his neofuturistic expressionism and the technical marvel in concrete shells.[9][page needed]

Eero also worked with his father, mother and sister designing elements of the Cranbrook campus in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, including the Cranbrook School, Kingswood School, the Cranbrook Art Academy and the Cranbrook Science Institute.[citation needed] The younger Saarinen's leaded glass designs are a prominent feature of these buildings throughout the campus.[citation needed]

Non-architectural activities

Saarinen was recruited by Donal McLaughlin, an architectural school friend from his Yale days, to join the military service in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Saarinen was assigned to draw illustrations for bomb disassembly manuals and to provide designs for the Situation Room in the White House.[10] Saarinen worked full-time for the OSS until 1944.[9][page needed]

Honours and awards

Eero Saarinen was elected a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects in 1952.[citation needed] He was elected a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1954.[11] In 1962, he was posthumously awarded a gold medal by the American Institute of Architects. [12]

Legacy

Saarinen is now considered one of the masters of American 20th-century architecture.[9][page needed] There has been a surge of interest in Saarinen's work in recent years, including a major exhibition and several books. This is partly because the Roche and Dinkeloo office has donated its Saarinen archives to Yale University, but also because Saarinen's oeuvre can be said to fit in with present-day concerns about pluralism of styles. He was criticized in his own time—most vociferously by Yale's Vincent Scully—for having no identifiable style; one explanation for this is that Saarinen adapted his neofuturistic vision to each individual client and project, which were never exactly the same.[9][page needed]

The papers of Aline and Eero Saarinen papers, from 1906-1977,[13] were donated in 1973 to the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (by Charles Alan, Aline Saarinen's brother and executor of her estate[citation needed]). In 2006, the bulk of these primary source documents on the couple were digitized and posted online on the Archives' website.[citation needed]

An exhibition of Saarinen's work, Eero Saarinen: Shaping the Future, was organized by the Finnish Cultural Institute in New York in collaboration with Yale School of Architecture, the National Building Museum, and the Museum of Finnish Architecture. The exhibition toured in Europe and the US from 2006 to 2010.[14] From May to August 2008, the exhibit was at the National Building Museum in Washington, DC.[15] The exhibition was accompanied by the book Eero Saarinen. Shaping the Future.[16]

In 2016 Eero Saarinen: The Architect Who Saw the Future, a film about Saarinen (co-produced by his son Eric), premiered on the PBS American Masters series.[17]

Personal life

Saarinen became a naturalized citizen of the United States in 1940.[18]

Saarinen married sculptor Lilian Swann in 1939, with whom he had two children, Eric and Susan. He married Aline Bernstein Louchheim, an art critic at The New York Times, in 1954, the year following his divorce from Lilian. They had a son, Eames, named after Saarinen's collaborator Charles Eames.[19][20]

Death

Saarinen died on September 1, 1961, at the age of 51 while undergoing an operation for a brain tumor. He was in Ann Arbor, Michigan overseeing the completion of a new music building for the University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre & Dance.[21] He is buried at White Chapel Memorial Park Cemetery, in Troy, Michigan.[22]

See also

References and notes

- ^ a b Staff of Arkkitehtuurimuseo (2012). "Arkkitehtiesittely: Eero Saarinen". MFA.fi (in Finnish). Helsinki, FIN: Arkkitehtuurimuseo [Museum of Finnish Architecture]. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- ^ a b Staff of Arkkitehtuurimuseo (2012). "Arkkitehtiesittely: Eliel Saarinen". MFA.fi (in Finnish). Helsinki, FIN: Arkkitehtuurimuseo [Museum of Finnish Architecture]. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- ^ a b Coir, Mark (2006). "The Cranbrook Factor". Eero Saarinen: Shaping the Future. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 097248812X. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Still, Sylvia (2016). "Eero Saarinen". Art-Directory.info. Muenchen, DEU: Art Directory GmbH. Retrieved December 28, 2016.[better source needed]

- ^ "Eero Saarinen".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Experts Pick Best-Designed Products of Modern Times". 22: New York Times. March 31, 1959. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "architect".

- ^ a b Sydney Opera House History 1954 - 1958 - Sydney Opera House

- ^ a b c d Coir, Mark (2006). "The Cranbrook Factor". Eero Saarinen: Shaping the Future2. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 097248812X. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) [full citation needed] - ^ Marefat, Mina (October 25, 2010). "Revealed: Eero Saarinen's Secret Wartime Role in the White House". The Architectural Review. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- ^ "Five Elected to Arts Institute". New York Times. February 10, 1954. p. 36. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- ^ American Institute of Architects. "Gold Medal-AIA". AIA. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- ^ AAA Staff (December 28, 2016). "Aline and Eero Saarinen papers, 1906-1977". Archives of American Art (AAA). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- ^ Arkkitehtuurimuseo Staff (October 1, 2006). "Eero Saarinen: Shaping the Future". MFA.fi. Helsinki, FIN: Arkkitehtuurimuseo [Museum of Finnish Architecture]. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- ^ NBM Staff (May 3, 2008). "Eero Saarinen: Shaping the Future". NBM.org. Washington, DC: National Building Museum (NBM). Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- ^ Eero Saarinen: Shaping the Future. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. 2006. ISBN 097248812X. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ About the Film - Eero Saarinen: The Architect Who Saw the Future | American Masters | PBS

- ^ "The LOC.GOV Wise Guide : An Architecture of Plurality". www.loc.gov.

- ^ Sean Flynn. "All in the family". NewportRI.com | News and information for Newport, Rhode Island. The Newport Daily News.

- ^ "Saarinen, Aline B. (Aline Bernstein), 1914-1972". socialarchive.iath.virginia.edu.

- ^ "The Eero Saarinen Masterpiece No One Sees: IBM Manufacturing and Training Facility in Rochester, Minnesota". Untapped Cities. August 20, 2013.

- ^ Entry for Eero Saarinen on Find a Grave

Further reading

- Saarinen, Eero (1962). Saarinen, Aline B. (ed.). Eero Saarinen on His Work: A Selection of Buildings Dating from 1947 to 1964 with Statements by the Architect. New Haven: Yale University Press. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- A&E (1997). America's Castles: Newspaper Moguls (television series episode). New York: A&E Network. ASIN B000FKP26M. Retrieved December 28, 2016. Episode featuring the Cranbrook House and Gardens.

- Roman, Antonio (2003). Eero Saarinen. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 1-56898-340-9.

- Risen, Clay (November 7, 2004). "Saarinen rising: A Much-Maligned Modernist Finally Gets His Due". Boston.com. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- Merkel, Jayne (2005). Eero Saarinen. London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 0-7148-4277-X.

- Pelkonen, Eeva-Liisa (2006). Eero Saarinen. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-11282-3.

- Serraino, Pierluigi (2006). Saarinen, 1910–1961: a Structural Expressionist. Köln: Taschen. ISBN 3-8228-3645-1.

- Knight, Richard (2008). Saarinen’s Quest, A Memoir. San Francisco: William Stout Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9746214-4-9.

- Santala, Susanna (2015). Laboratory for a New Architecture: Airport Terminal, Eero Saarinen and the Historiography of Modern Architecture (Ph.D. thesis). Helsinki: University of Helsinki. ISBN 978-951-51-0993-4.

External links

- EMFURN Staff (November 15, 2014). "Your Guide to Vintage Danish Mid Century Modern Furniture & Designers" (commercial sales blog). EMFURN.com. Retrieved December 28, 2016. Commercial furniture sales blog mentioning the Womb chair.

- Saarinen, Eero (1910–1961). Kansallisbiografia. Template:En icon

- "Trans World Airlines Unit Terminal Building, New York International Airport, architectural drawings, 1958-1961". columbia.edu. Retrieved December 28, 2016. Held by the Department of Drawings & Archives, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

- "Lines of Authority". Retrieved December 28, 2016 – via www.time.com.

- "UM School of Music, Theatre & Dance – About Us – Facilities". umich.edu. Retrieved December 28, 2016. Earl V. Moore Building by Eero Saarinen.

- "Prints & Photographs Online Catalog". loc.gov. Retrieved December 28, 2016. Balthazar Korab Collection at the Library of Congress.

- "Saarinen's Village". palni.edu. Retrieved December 28, 2016. The Concordia Campus Through Time.

- Digital image database.[dead link] Yale University Library. Containing 1296 images and drawings from Saarinen's archives.

- Finding aid to the Eero Saarinen Collection at Manuscripts and Archives.[dead link] Yale University Library.

- "tulip-chair.org". tulip-chair.org. Retrieved December 28, 2016. Saarinen Tulip Chair.

- Barbano, Michael. "Eero Saarinen: Shaping The Future". eerosaarinen.net. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- Eero Saarinen Exhibitions at Cranbrook Art Museum.

- "Eero Saarinen: Shaping Community". nbm.org. Retrieved December 28, 2016. Blueprints, Winter 2007-08.