Caleb Stanford (talk | contribs) →Closed-form characterization: 2 important fixes Tag: 2017 wikitext editor |

Caleb Stanford (talk | contribs) →Examples: Add table of example integer sequences Tag: 2017 wikitext editor |

||

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

==Examples== |

==Examples== |

||

{| class="wikitable" style="margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto; border: none;" |

|||

|+ Selected examples of integer constant-recursive sequences |

|||

! Name !! Order (<math>d</math>) !! First few values !! Recurrence (for <math>n \ge d</math>) !! Generating function !! OEIS |

|||

|- |

|||

| Zero sequence || 0 || 0, 0, 0, ... || <math>s(n) = 0</math> || <math>\frac{0}{1}</math> || {{OEIS link|A000004}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| One sequence || 1 || 1, 1, 1, ... || <math>s(n) = s(n-1)</math> || <math>\frac{1}{1-x}</math> || {{OEIS link|A000012}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| Characteristic function of <math>\{0\}</math> || 1 || 1, 0, 0, 0, ... || <math>s(n) = 0</math> || <math>\frac{1}{1}</math> || {{OEIS link|A000007}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| Powers of two || 1 || 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, ... || <math>s(n) = 2 s(n-1)</math> || <math>\frac{1}{1-2x}</math> || {{OEIS link|A000079}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| Powers of -1|| 1 || 1, -1, 1, -1, ... || <math>s(n) = -s(n-1)</math> || <math>\frac{1}{1+x}</math> || {{OEIS link|A033999}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| Characteristic function of <math>\{1\}</math> || 2 || 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, ... || <math>s(n) = 0</math> || <math>\frac{x}{1}</math> || {{OEIS link|A063524}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| Decimal expansion of 1/6 || 2 || 1, 6, 6, 6, ... || <math>s(n) = s(n-1)</math> || <math>\frac{1 + 5x}{1 - x}</math> || {{OEIS link|A020793}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| Decimal expansion of 1/11 || 2 || 0, 9, 0, 9, ... || <math>s(n) = s(n-2)</math> || <math>\frac{9x}{1-x^2}</math> || {{OEIS link|A010680}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| Nonnegative integers || 2 || 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, ... || <math>s(n) = 2s(n-1) - s(n-2)</math> || <math>\frac{x}{(1-x)^2}</math> || {{OEIS link|A001477}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| Odd positive integers || 2 || 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, ... || <math>s(n) = 2s(n-1) - s(n-2)</math> || <math>\frac{1+x}{(1-x)^2}</math> || {{OEIS link|A005408}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| Fibonacci numbers || 2 || 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, ... || <math>s(n) = s(n-1) + s(n-2)</math> || <math>\frac{x}{1-x-x^2}</math> || {{OEIS link|A000045}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| Lucas numbers || 2 || 2, 1, 3, 4, 7, 11, ... || <math>s(n) = s(n-1) + s(n-2)</math> || <math>\frac{2-x}{1-x-x^2}</math> || {{OEIS link|A000032}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| Pell numbers || 2 || 0, 1, 2, 5, 12, 29, ... || <math>s(n) = 2s(n-1) + s(n-2)</math> || <math>\frac{x}{1-2x-x^2}</math> || {{OEIS link|A000129}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| Inverse of 6th cyclotomic polynomial || 2 || 1, 1, 0, -1, -1, 0, 1, 1, 0, -1, -1, 0, ... || <math>s(n) = s(n-1) - s(n-2)</math> || <math>\frac{1}{1-x+x^2}</math> || {{OEIS link|A010892}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| Triangle numbers || 3 || 0, 1, 3, 6, 10, 15, ... || <math>s(n) = 3s(n-1) - 3s(n-2) + s(n-3)</math> || <math>\frac{x}{(1-x)^3}</math> || {{OEIS link|A000217}} |

|||

|} |

|||

===Fibonacci sequence=== |

===Fibonacci sequence=== |

||

Revision as of 21:16, 18 November 2021

In mathematics and theoretical computer science, a constant-recursive sequence or linear recurrence sequence is an infinite sequence of numbers in which each number in the sequence is equal to a linear combination of one or more of its immediate predecessors.

The most famous example of a constant-recursive sequence is the Fibonacci sequence, in which each number is the sum of the previous two; formally, we say that it satisfies the linear recurrence relation , where is the th Fibonacci number. Generalizing this idea, a constant-recursive sequence satisfies a formula of the form

where are constants. In addition to the Fibonacci sequence, constant-recursive sequences include many other well-known sequences, such as arithmetic progressions, geometric progressions, and polynomials.

Constant-recursive sequences arise in combinatorics and the theory of finite differences; in algebraic number theory, due to the relation of the sequence to the roots of a polynomial; in the analysis of algorithms in the running time of simple recursive functions; and in formal language theory, where they count strings up to a given length in a regular language. Constant-recursive sequences are closed under important mathematical operations such as term-wise addition, term-wise multiplication, and Cauchy product. A seminal result is the Skolem–Mahler–Lech theorem, which states that the zeros of a constant-recursive sequence have a regularly repeating (eventually periodic) form. On the other hand, the Skolem problem, which asks for algorithm to determine whether a linear recurrence has at least one zero, remains one of the unsolved problems in mathematics.

Definition

An order-d homogeneous linear recurrence relation is an equation of the form

where the d coefficients are coefficients ranging over the integers, rational numbers, algebraic numbers, real numbers, or complex numbers.

A sequence (ranging over the same domain as the coefficients) is a constant-recursive sequence if there is an order-d homogeneous linear recurrence with constant coefficients that it satisfies for all . Note that this definition allows eventually-periodic sequences such as and , which are disallowed by some authors.[1] These sequences can be excluded by requiring that .

The order of a constant-recursive sequence is the smallest such that the sequence satisfies an order-d homogeneous linear recurrence, or for the everywhere-zero sequence.

Equivalent definitions

In terms of matrices

A sequence is constant-recursive of order if and only if it can be written as

where is a vector, is a matrix, and is a vector, where the elements come from the same domain (integers, rational numbers, algebraic numbers, real numbers, or complex numbers) as the original sequence. Specifically, can be taken to be the first values of the sequence, the linear transformation that computes from , and the vector .

In terms of vector spaces

A sequence is constant-recursive if and only if the set of sequences

is contained in a vector space whose dimension is finite, i.e. a finite-dimensional subspace of closed under the left-shift operator. This is because the order- linear recurrence relation can be understood as a proof of linear dependence between the vectors for . An extension of this argument shows that the order of the sequence is equal to the dimension of the vector space generated by for all .

In terms of non-homogeneous linear recurrences

| Non-homogeneous | Homogeneous |

|---|---|

A non-homogeneous linear recurrence is an equation of the form

where is an additional constant. Any sequence satisfying a non-homogeneous linear recurrence is constant-recursive. This is because subtracting the equation for from the equation for yields a homogeneous recurrence for , from which we can solve for to obtain

In terms of generating functions

A sequence is constant-recursive precisely when its generating function

is a rational function , where and are polynomials. The denominator is the polynomial obtained from the auxiliary polynomial by reversing the order of the coefficients, and the numerator is determined by the initial values of the sequence.[2] Note that the denominator here must be a polynomial not divisible by (and in particular nonzero). The explicit derivation of the generating function in terms of the linear recurrence is

where

Examples

| Name | Order () | First few values | Recurrence (for ) | Generating function | OEIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero sequence | 0 | 0, 0, 0, ... | A000004 | ||

| One sequence | 1 | 1, 1, 1, ... | A000012 | ||

| Characteristic function of | 1 | 1, 0, 0, 0, ... | A000007 | ||

| Powers of two | 1 | 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, ... | A000079 | ||

| Powers of -1 | 1 | 1, -1, 1, -1, ... | A033999 | ||

| Characteristic function of | 2 | 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, ... | A063524 | ||

| Decimal expansion of 1/6 | 2 | 1, 6, 6, 6, ... | A020793 | ||

| Decimal expansion of 1/11 | 2 | 0, 9, 0, 9, ... | A010680 | ||

| Nonnegative integers | 2 | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, ... | A001477 | ||

| Odd positive integers | 2 | 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, ... | A005408 | ||

| Fibonacci numbers | 2 | 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, ... | A000045 | ||

| Lucas numbers | 2 | 2, 1, 3, 4, 7, 11, ... | A000032 | ||

| Pell numbers | 2 | 0, 1, 2, 5, 12, 29, ... | A000129 | ||

| Inverse of 6th cyclotomic polynomial | 2 | 1, 1, 0, -1, -1, 0, 1, 1, 0, -1, -1, 0, ... | A010892 | ||

| Triangle numbers | 3 | 0, 1, 3, 6, 10, 15, ... | A000217 |

Fibonacci sequence

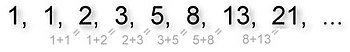

The sequence 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, ... of Fibonacci numbers is constant-recursive of order 2 because it satisfies the recurrence with . For example, and .

Lucas sequences

The sequence 2, 1, 3, 4, 7, 11, 18, 29, 47, 76, 123, 199, ... (sequence A000032 in the OEIS) of Lucas numbers satisfies the same recurrence as the Fibonacci sequence but with initial conditions and . More generally, every Lucas sequence is constant-recursive of order 2.

Arithmetic progressions

For any and any , the arithmetic progression is constant-recursive of order 2, because it satisfies . Generalizing this, see polynomial sequences below.

Geometric progressions

For any and , the geometric progression is constant-recursive of order 1, because it satisfies . This includes, for example, the sequence 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, ... as well as the rational number sequence .

Eventually periodic sequences

A sequence that is eventually periodic with period length is constant-recursive, since it satisfies for all , where the order is the length of the initial segment including the first repeating block. Examples of such sequences are 1, 0, 0, 0, ... (order 1) and 1, 6, 6, 6, ... (order 2).

Polynomial sequences

For any polynomial , the sequence of its values is a constant-recursive sequence. If the degree of the polynomial is , the sequence satisfies a recurrence of order , with coefficients given by the corresponding element of the binomial transform.[3] The first few such equations are

- for a degree 0 (that is, constant) polynomial,

- for a degree 1 or less polynomial,

- for a degree 2 or less polynomial, and

- for a degree 3 or less polynomial.

A sequence obeying the order-d equation also obeys all higher order equations. These identities may be proved in a number of ways, including via the theory of finite differences.[4] Any sequence of integer, real, or complex values can be used as initial conditions for a constant-recursive sequence of order . If the initial conditions lie on a polynomial of degree or less, then the constant-recursive sequence also obeys a lower order equation.

Enumeration of words in a regular language

Let be a regular language, and let be the number of words of length in . Then is constant-recursive. For example, for the language of all binary strings, for the language of all unary strings, and for the language of all binary strings that do not have two consecutive ones. More generally, any function accepted by a weighted automaton over the unary alphabet over the semiring is constant-recursive.

Other examples

The sequences of Jacobsthal numbers, Padovan numbers, Pell numbers, and Perrin numbers are constant-recursive.

Closed-form characterization

Constant-recursive sequences admit the following unique closed form characterization using exponential polynomials: every constant-recursive sequence can be written in the form

where

- is a sequence which is zero for all but finitely many ;

- are complex polynomials; and

- are distinct complex number constants.

This characterization is exact: every sequence of complex numbers that can be written in the above form is constant-recursive.

For example, the Fibonacci number is written in this form using Binet's formula:

where is the Golden ratio and , both roots of the equation . In this case, , for all , (constant polynomials), , and . Notice that though the original sequence was over the integers, the closed form solution involves real or complex roots. In general, for sequences of integers or rationals, the closed formula will use algebraic numbers.

The complex numbers are derived as the roots of the characteristic polynomial (or "auxiliary polynomial") of the recurrence:

whose coefficients are the same as those of the recurrence. If the roots are all distinct, then the polynomials are all constants, which can be determined from the initial values of the sequence. The term is only needed when ; if then it corrects for the fact that some initial values may be exceptions to the general recurrence. In particular, for all , the order of the sequence.

In the general case where the roots of the characteristic polynomial are not necessarily distinct, and is a root of multiplicity , the term is multiplied by a degree- polynomial in (i.e. in the formula has degree ). For instance, if the characteristic polynomial factors as , with the same root r occurring three times, then the th term is of the form

Derivation of the closed form

The closed form can be derived from the generating function via partial fraction decomposition. Specifically, if the generating function is written as

then the polynomial determines the initial set of corrections , the denominator determines the exponential term , and the degree together with the numerator determine the polynomial coefficient .

Closure properties

Constant-recursive sequences are closed under the following operations, where denote constant-recursive sequences, are their generating functions, and are their orders, respectively.

| Operation | Definition | Requirement | Generating Function Equivalent | Order |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Term-wise sum | — | |||

| Term-wise product | — | — | [6] | |

| Cauchy product | — | |||

| Left shift | — | |||

| Right shift | — | |||

| Cauchy inverse | — | — | ||

| Kleene star | — |

The closure under term-wise addition and multiplication follows from the closed-form characterization in terms of exponential polynomials. The closure under Cauchy product follows from the generating function characterization. The requirement for Cauchy inverse is necessary for the case of integer sequences, but can be replaced by if the sequence is over any field (rational, algebraic, real, or complex numbers).

Behavior

Zeros

Despite simple local dynamics, constant-recursive functions exhibit complex global behavior. Define a zero of a constant-recursive sequence to be a nonnegative integer such that . It is known via the Skolem–Mahler–Lech theorem that the zeros of the sequence are eventually repeating: there exists constants and such that for all , if and only if . This result holds for a constant-recursive sequence over the complex numbers, or more generally, over any field of characteristic zero.[7]

Decision problems

The pattern of zeros in a constant-recursive sequence can also be investigated from the perspective of computability theory. To do so, the description of the sequence must be given a finite description; this can be done if the sequence is over the integers or rational numbers, or even over the algebraic numbers.[6] Given such an encoding for sequences , the following problems can be studied:

| Problem | Description | Status (2021) |

|---|---|---|

| Existence of a zero (Skolem problem) | On input , is for some ? | Open |

| Infinitely many zeros | On input , is for infinitely many ? | Decidable |

| Positivity | On input , is for all ? | Open |

| Eventual positivity | On input , is for all sufficiently large ? | Open |

Because the square of a constant-recursive sequence is still constant-recursive (see closure properties), the existence-of-a-zero problem in the table above reduces to positivity, and infinitely-many-zeros reduces to eventual positivity. Many other problems also reduce to those in the above table: for example, whether for some reduces to existence-of-a-zero for the sequence . As a second example, for sequences in the real numbers, weak positivity (is for all ?) reduces to positivity of the sequence (because the answer must be negated, this is a Turing reduction).

The Skolem-Mahler-Lech theorem discussed above would answer all of the above questions, except that its proof is non-constructive. It states that for all , the zeros are repeating; however, the value of is not known to be computable, so this does not lead to a solution to the existence-of-a-zero problem.[6] On the other hand, the exact pattern which repeats after is computable.[6] This is why the infinitely-many-zeros problem is decidable: just determine if the infinitely-repeating pattern is empty.

Generalizations

- A holonomic sequence is a natural generalization where the coefficients of the recurrence are allowed to be polynomial functions of rather than constants.

- A -regular sequence satisfies a linear recurrences with constant coefficients, but the recurrences take a different form. Rather than being a linear combination of for some integers that are close to , each term in a -regular sequence is a linear combination of for some integers whose base- representations are close to that of . Constant-recursive sequences can be thought of as -regular sequences, where the base-1 representation of consists of copies of the digit .

General references

- "OEIS Index Rec". OEIS index to a few thousand examples of linear recurrences, sorted by order (number of terms) and signature (vector of values of the constant coefficients)

- Brousseau, Alfred (1971). Linear Recursion and Fibonacci Sequences. Fibonacci Association.

- Graham, Ronald L.; Knuth, Donald E.; Patashnik, Oren (1994). Concrete Mathematics: A Foundation for Computer Science (2 ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-55802-9.

Notes

- ^ Kauers, Manuel; Paule, Peter (2010-12-01). The Concrete Tetrahedron: Symbolic Sums, Recurrence Equations, Generating Functions, Asymptotic Estimates. Springer Vienna. ISBN 978-3-7091-0444-6.

- ^ Martino, Ivan; Martino, Luca (2013-11-14). "On the variety of linear recurrences and numerical semigroups". Semigroup Forum. 88 (3): 569–574. arXiv:1207.0111. doi:10.1007/s00233-013-9551-2. ISSN 0037-1912.

- ^ Boyadzhiev, Boyad (2012). "Close Encounters with the Stirling Numbers of the Second Kind" (PDF). Math. Mag. 85: 252–266.

- ^ Jordan, Charles; Jordán, Károly (1965). Calculus of Finite Differences. American Mathematical Soc. pp. 9–11. ISBN 978-0-8284-0033-6. See formula on p.9, top.

- ^ Greene, Daniel H.; Knuth, Donald E. (1982), "2.1.1 Constant coefficients – A) Homogeneous equations", Mathematics for the Analysis of Algorithms (2nd ed.), Birkhäuser, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d Ouaknine, Joël; Worrell, James (2012), "Decision problems for linear recurrence sequences", Reachability Problems: 6th International Workshop, RP 2012, Bordeaux, France, September 17–19, 2012, Proceedings, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 7550, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, pp. 21–28, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-33512-9_3, MR 3040104.

- ^ Lech, C. (1953), "A Note on Recurring Series", Arkiv för Matematik, 2: 417–421, doi:10.1007/bf02590997