m Typo |

m Open access bot: hdl updated in citation with #oabot. |

||

| (30 intermediate revisions by 22 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|District heating with very low temperatures}} |

|||

[[ |

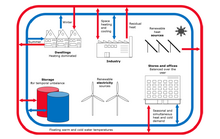

[[File:Cold District heating, schematic function.png|thumb|Schematic function of a cold district heating network]] |

||

'''Kalte Nahwärme''' bzw. '''Kalte Fernwärme''' ist eine technische Variante eines Wärmeversorgungsnetzes, das mit niedrigen Übertragungstemperaturen deutlich unterhalb herkömmlicher [[Fern|Fern-]] oder [[Nahwärme]]systeme arbeitet und sowohl [[Gebäudeheizung|Wärme]] als auch [[Klimatisierung|Kälte]] bereitstellen kann. Üblich sind Übertragungstemperaturen im Bereich von ca. 10 bis 25 °C, wodurch verschiedene Verbraucher unabhängig voneinander gleichzeitig heizen und kühlen können. Die [[Warmwasser]]erzeugung sowie die Gebäudeheizung erfolgt dabei über Wasser-[[Wärmepumpe]]n, die ihre Wärmeenergie aus dem Wärmenetz gewinnen, während die Kühlung entweder direkt über das Kaltwärmenetz oder ggf. indirekt über [[Kältemaschine]]n erfolgen kann. Kalte Nahwärme werden teils auch als ''Anergienetze'' bezeichnet. Die in der wissenschaftlichen Fachterminologie Sammelbezeichnung für derartige Systeme lautet {{EnS|''5th generation district heating and cooling''|de=Fünfte Generation Fernwärme und -kälte}}. Aufgrund der Möglichkeit, komplett mittels [[Erneuerbare Energien|erneuerbarer Energien]] betrieben zu werden und zugleich einen Beitrag zum Ausgleich der schwankenden Produktion von [[Windkraftanlage|Windkraft-]] und [[Photovoltaikanlage]]n zu leisten, gelten kalte Nahwärmenetze als vielversprechende Option für eine nachhaltige, potentiell [[Treibhausgas|treibhausgas]]- und emissionsfreie Wärmeversorgung. |

|||

'''Cold district heating''' is a technical variant of a [[district heating]] network that operates at low transmission temperatures well below those of conventional district heating systems and can provide both [[space heating]] and [[cooling]]. Transmission temperatures in the range of approx. 10 to 25 °C are common, allowing different consumers to heat and cool simultaneously and independently of each other. Hot water is produced and the building heated by water [[heat pump]]s, which obtain their thermal energy from the heating network, while cooling can be provided either directly via the cold heat network or, if necessary, indirectly via [[chiller]]s. Cold local heating is sometimes also referred to as an ''anergy network''. The collective term for such systems in scientific terminology is '''5th generation district heating and cooling'''. Due to the possibility of being operated entirely by [[renewable energy|renewable energies]] and at the same time contributing to balancing the fluctuating production of [[wind turbine]]s and [[photovoltaic system]]s, cold local heating networks are considered a promising option for a sustainable, potentially [[greenhouse gas]] and emission-free heat supply. |

|||

== |

== Terms == |

||

As of 2019, the fifth generation heating networks described here have not yet been given a uniform name, and there are also various definitions for the general technical concept. In the English language technical literature the terms ''Low temperature District Heating and Cooling'' (LTDHC), ''Low temperature networks'' (LTN), ''Cold District Heating'' (CHD) and ''Anergy networks'' or ''Anergy grid'' are used. In addition, some publications have definitional conflicts in the delimitation to "warm" district heating networks, because certain authors consider ''Low temperature District Heating and Cooling'' as well as ''Ultra-low temperature District Heating'' as subforms of 4th generation district heating. In addition, the definition of so-called low-ex networks allows to classify them as both fourth and fifth generation.<ref name="Buffa">{{citation|author=Simone Buffa |display-authors=et al |periodical=[[Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews]]|title=5th generation district heating and cooling systems: A review of existing cases in Europe|volume=104|pages=504–522|date=2019|doi=10.1016/j.rser.2018.12.059 |

|||

|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

== |

== History == |

||

[[ |

[[File:Furkabasistunnel Südwestportal.jpg|thumb|One of the first cold local heating networks uses seepage water from the [[Furka Base Tunnel]] as a heat source]] |

||

The first cold district heating network is the heating network in [[Arzberg, Bavaria|Arzberg]] in Upper Franconia, Germany. In the Arzberg power station there, which has since been shut down, uncooled cooling water was taken from between the turbine condenser and the cooling tower and piped to various buildings, where it was then used as a heat source for heat pumps. This was used to heat the school and the swimming pool in addition to various residential buildings and commercial enterprises.<ref>Leonhard Müller: ''Handbuch der Elektrizitätswirtschaft: Technische, wirtschaftliche und rechtliche Grundlagen''. Berlin/Heidelberg 1998, p 266f.</ref> |

|||

Another very early plant was put into operation in [[Wulfen]] in 1979. There, 71 buildings were supplied with heat energy, which was taken from the groundwater. Finally, in 1994, the first cold heating network was opened, using waste heat from an industrial company, a textile company. Also in 1994 (according to Pellegrini and Bianchini already in 1991 <ref name="Pellegrini">{{citation|author1=Marco Pellegrini |author2=Augusto Bianchini|periodical=[[Energies]]|title=The Innovative Concept of Cold District Heating Networks: A Literature Review|volume=11|year=2018|page=236 |doi=10.3390/en11010236 |

|||

|doi-access=free|hdl=11585/624860|hdl-access=free}}</ref>) a cold local heating network was built in the Swiss village Oberwald, which is operated with seepage water from the [[Furka base tunnel]].<ref name="Buffa" /> |

|||

As of January 2018, a total of 40 schemes were in operation in Europe, 15 each in Germany and Switzerland. Most of the projects were pilot plants with a heat output of several 100 kWth up to the single-digit MW range, the largest plant had an output of approx. 10 MWth. In the 2010s about three plants per year were added.<ref name="Buffa" /> |

|||

Insgesamt waren mit Stand Januar 2018 in Europa 40 Anlagen in Betrieb, davon jeweils 15 in Deutschland und der Schweiz. Bei den meisten Projekten handelte es sich dabei um Pilotanlagen mit einer Wärmeleistung von einigen 100 [[Watt (Einheit)|kW<sub>th</sub>]] bis in den einstelligen MW-Bereich, die größte Anlage hatte eine Leistung von ca. 10 MW<sub>th</sub>. In den 2010er Jahren kamen etwa drei Anlagen pro Jahr hinzu.<ref name="Buffa" /> |

|||

== |

== Concept == |

||

Cold heat networks are heat networks that are operated at very low temperatures (usually between 10 and 25 °C). They can be fed from a variety of frequently regenerative heat sources and allow the simultaneous production of heat and cold. Since the operating temperatures are not sufficient for the production of hot water and heating heat, the temperature at the consumer is raised to the required level by means of [[heat pump]]s. In the same way, cold can be produced and the waste heat can be fed back into the heating network. In this way, connected consumers are not only customers, but can also act as [[prosumer]]s, who can either consume or produce heat depending on the circumstances.<ref name="Buffa" /> |

|||

Kalte Wärmenetze sind Wärmenetze, die mit sehr niedrigen Temperaturen (meist zwischen 10 bis 25° C) betrieben werden. Sie können von einer Vielzahl häufig [[Erneuerbare Energien|regenerativer Wärmequellen]] gespeist werden und erlauben die simultane Produktion von Wärme und Kälte. Da die Betriebstemperaturen nicht ausreichend sind für die Warmwasser- und Heizwärmeproduktion, wird die Temperatur beim Abnehmer mittels Wärmepumpen auf das erforderliche Niveau angehoben. Auf die gleiche Art und Weise kann auch Kälte produziert werden und die Abwärme ins Wärmenetz zurückgespeist werden. Auf diese Weise sind angeschlossene nicht nur Kunden, sondern können als [[Prosumer]] fungieren, die abhängig von der jeweiligen Umständen sowohl Wärme konsumieren oder produzieren können.<ref name="Buffa" /> |

|||

The concept of cold local heating networks is derived from groundwater heat pumps as well as open-loop heat pumps. While the former are mainly used to supply individual houses, the latter are often found in commercial buildings which have both heating and cooling needs and have to meet these needs in parallel. Cold local heating extends this concept to individual residential areas or districts. Like ordinary geothermal heat pumps, cold local heating networks have the advantage over air heat pumps of operating more efficiently due to the lower temperature difference between the heat source and the heating temperature. However, compared to geothermal heat pumps, cold local heating networks have the additional advantage that even in urban areas, where space problems often prevent the use of geothermal heat pumps, heat can be stored seasonally via central heat storage, and in addition, the different load profiles of different buildings may allow a balance between heating and cooling requirements.<ref name="Buffa" /> |

|||

Das Konzept der kalten Nahwärmenetze stammt von Grundwasserwärmepumpen als auch Open-Loop-Wärmepumpen ab. Während erstere vorwiegend zur Versorgung von Einzelhäusern eingesetzt werden, sind letztere häufig in Gewerbegebäuden anzutreffen, die sowohl Wärme- als auch Kühlbedarf haben und diesen parallel decken müssen. Kalte Nahwärme erweitert dieses Konzept auf einzelne Wohngebiete oder Stadtteile. Wie gewöhnliche Erdwärmepumpen haben Kalte Nahwärmenetze gegenüber Luftwärmepumpen den Vorteil, aufgrund des niedrigeren Temperaturdeltas zwischen Wärmequelle und Heiztemperatur effizienter zu arbeiten. Gegenüber Erdwärmepumpen haben Kalte Nahwärmenetze jedoch den zusätzlichen Vorteil, dass auch im städischen Raum, wo häufig Platzprobleme den Einsatz von Erdwärmepumpen verhindern, über zentrale [[Wärmespeicher]] saisonal Wärme speichert werden kann, und darüber hinaus die unterschiedlichen Lastprofile verschiedener Gebäude ggf. einen Ausgleich zwischen Wärme- und Kältebedarf ermöglichen.<ref name="Buffa" /> |

|||

Cold district heating is particularly suitable where there are different types of buildings (residential, commercial, supermarkets, etc.) and therefore there is a demand for both heating and cooling, enabling energy balancing over short or long periods of time. Alternatively, seasonal heat storage systems allow for a balance of energy supply and demand. By using different (waste) heat sources and combining heat sources and heat sinks, synergies can also be created and the heat supply can be further developed in the direction of a [[circular economy]]. In addition, the low operating temperature of the cold-heating networks makes it possible to feed otherwise hardly usable low-temperature [[waste heat]] into the network in an uncomplicated manner. At the same time, the low operating temperature significantly reduces the heat losses of the heating network, which limits the energy losses, especially in summer, when there is little demand for heat. The annual performance factor of heat pumps is also relatively high, especially compared to air-sourced heat pumps. A study of 40 systems commissioned up to 2018 showed that the heat pumps achieved an seasonal COP of at least 4 for the majority of the systems studied; the highest seasonal COP values were about 6.<ref name="Buffa" /> |

|||

Besonders gut ist ihr Einsatz dort geeignet, wo verschiedene Arten von Bebauung (Wohngebäude, Gewerbe, Supermärkte etc.) existieren und somit sowohl Wärme und Kälte nachgefragt wird, wodurch ein Energieausgleich über kurze oder lange Zeiträume ermöglicht wird. Alternativ ermöglichen saisonale Wärmespeicher einen Ausgleich von Energieeinspeisung und -nachfrage. Durch die Nutzung verschiedener (Ab)-Wärmequellen und die Kombination von Wärmequellen und Wärmesenken können zudem [[Synergie]]n geschaffen werden und die Wärmeversorgung in Richtung einer [[Kreislaufwirtschaft]] weiterentwickelt werden. Zudem ermöglicht die niedrige Betriebstemperatur der Kaltwärmenetze sonst kaum nutzbare Niedertemperaturabwärme unkompliziert in das Netz einzuspeisen. Gleichzeitig verringert die niedrige Betriebstemperatur die Wärmeverluste des Wärmenetzes deutlich, was insbesondere im Sommer, wo nur eine geringe Wärmenachfrage herrscht, die Energieverluste begrenzt.<ref name="Buffa" /> Auch ist die [[Jahresarbeitszahl]] der Wärmepumpen gerade verglichen mit Luft-Wärmepumpen relativ hoch. Eine Untersuchung von 40 bis zum Jahr 2018 in Betrieb genommenen Anlagen ergab, dass die Wärmepumpen bei einem Großteil der untersuchten Systeme eine Jahresarbeitszahl von mindestens 4 erreichten; die höchsten Werte lagen bei 6.<ref name="Buffa" /> |

|||

Technologically, cold heat networks are part of the concept of smart heat networks.<ref name="Buffa" /> |

|||

== |

== Components == |

||

=== Heat sources === |

|||

[[File:Newark Sugar Factory - geograph.org.uk - 1068555.jpg|thumb|Cold heating networks are ideally suited for the use of [[waste heat]] from industry and commercial buildings]] |

|||

Various heat sources can be used as energy suppliers for the cold heating network, in particular [[Renewable energy|renewable sources]] such as the ground, water, commercial and industrial waste heat, [[solar thermal]] energy and ambient air, which can be used individually or in combination.<ref name="Buffa" /> Due to the generally modular design of cold local heating networks, new heat sources can be gradually developed as the network is further expanded, so that larger heating networks can be fed from a variety of different sources.<ref name="Boesten" /> |

|||

In practice almost inexhaustible sources are e.g. [[sea water]], [[river]]s, [[lake]]s or [[groundwater]]. Of the 40 cold heating networks in operation in Europe as of January 2018, 17 used water bodies or groundwater as a heat source. The second most important heat source was [[geothermal energy]]. This is usually accessed via geothermal boreholes using vertical borehole heat exchangers. However, it is also possible to use surface collectors such as agrothermal collectors. In this case, horizontal collectors are ploughed into agricultural land at a depth of 1.5 to 2 m, i.e. below the working depth of agricultural machines, which can extract heat from the soil as required. This concept, which allows further agricultural use, has been realized, for example, in a cold heat network in the German town [[Wüstenrot]].<ref name="Buffa" /> |

|||

=== Wärmequellen === |

|||

[[Datei:Newark Sugar Factory - geograph.org.uk - 1068555.jpg|mini|Kalte Wärmenetze eignen sich hervorragend für die Nutzung von Abwärme aus Industrie und Gewerbe]] |

|||

Als Energielieferant für das Kaltwärmenetz kommen diverse Wärmequellen in Frage, insbesondere erneuerbare Quellen wie das [[Geothermie|Erdreich]], [[Gewässer]], gewerbliche und industrielle [[Abwärme]], [[Solarthermie]] und Umgebungsluft, die einzeln oder in Kombination genutzt werden können.<ref name="Buffa" /> Aufgrund des generell modularen Aufbaus kalter Nahwärmenetze können bei weiterem Ausbau des Netzes nach und nach neue Wärmequellen erschlossen werden, sodass größere Wärmenetze über eine Vielzahl unterschiedlicher Quellen gespeist werden können.<ref name="Boesten" /> |

|||

In addition, there are cold-heating networks that extract geothermal energy from [[tunnel]]s and abandoned [[coal mine]]s. Waste heat from industrial and commercial enterprises can also be used. For example, two cold-heating networks in Aurich and Herford use waste heat from dairies and another plant in Switzerland uses waste heat from a biomass power plant, while another cold-heating network uses waste heat from a textile company. Other possible heat sources include solar thermal energy (especially for regenerating geothermal sources and charging storage tanks), large heat pumps that use environmental heat, the [[sewage]] system, [[combined heat and power]] plants and biomass- or fossil-fired peak load boilers to support other heat sources. The low operating temperatures of cold-heating networks are particularly favourable to solar thermal systems, CHP units and waste heat recovery, as these can operate at maximum efficiency under these conditions. At the same time, cold heating networks enable industrial and commercial companies with waste heat potential, such as [[supermarket]]s and [[data centre]]s, to feed thermal energy into the grid without any major financial investment risk, since at the temperature level of cold heating networks, direct heat feed is possible without a heat pump.<ref name="Buffa" /> |

|||

In der Praxis nahezu unerschöpfliche Quellen sind z. B. Meerwasser, Flüsse, Seen oder Grundwasser. Von den mit Stand Januar 2018 40 in Europa in Betrieb befindlichen Kaltwärmenetzen nutzte 17 Gewässer bzw. Grundwasser als Wärmequelle. Zweitwichtigste Wärmequelle war die Erdwärme. Diese wird zumeist über geothermische Bohrungen mittels senkrechter [[Erdwärmesonde]]n erschlossen. Möglich ist aber auch die Nutzung von Flächenkollektoren wie z. B. [[Agrothermie]]kollektoren. Hierbei werden auf landwirtschaftlicher Nutzfläche, etwa in 1,5 bis 2 m Tiefe und damit unterhalb der Arbeitstiefe landwirtschaftlicher Geräte, waagrechte Kollektoren eingepflügt, die dem Boden bei Bedarf Wärme entziehen können. Dieses Konzept, das die weitere landwirtschaftliche Nutzung erlaubt, wurde beispielsweise in einem Kaltwärmenetz in [[Wüstenrot]] realisiert.<ref name="Buffa" /> |

|||

Another heat source can also be the return line of conventional district heating networks.<ref name="Buffa" /> If the operating temperature of the cold heating network is lower than the soil temperature, the network itself can also absorb heat from the surrounding soil. In this case the network then acts as a kind of [[geothermal collector]].<ref name="Brennenstuhl">{{citation|author=Marcus Brennenstuhl |display-authors=et al |periodical=Applied Sciences|title=Report on a Plus-Energy District with Low-Temperature DHC Network, Novel Agrothermal Heat Source, and Applied Demand Response|volume=9|date=2019|issue=23 |page=5059 |doi=10.3390/app9235059 |doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

Zudem existieren Kaltwärmenetze, die geothermische Energie aus Tunneln sowie aufgegebenen Kohleminen gewinnen. Ebenfalls genutzt werden kann Abwärme aus Industrie- und Gewerbebetrieben. Beispielsweise nutzen zwei Kaltwärmenetze in [[Aurich]] und [[Herford]] die Abwärme von [[Molkerei]]en und eine weitere Anlage in der Schweiz Abwärme aus einem [[Biomassekraftwerk]], während ein weiteres Kaltwärmenetz auf Abwärme aus einem Textilbetrieb zurückgriff. Weitere mögliche Wärmequellen sind u. a. Solarthermie (insbesondere zur Regeneration geothermischer Quellen und Beladung von Speichern), Großwärmepumpen, die Umweltwärme nutzen, die [[Kanalisation]], [[Blockheizkraftwerk]]e und biogen oder fossil befeuerte Spitzenlastkessel zur Unterstützung anderer Wärmequellen. Die niedrigen Betriebstemperaturen von Kaltwärmenetzen begünstigen dabei besonders Solarthermieanlagen, BHKWs und die Abwärmenutzung, da diese unter diesen Bedingungen mit maximaler Effizienz arbeiten können. Zugleich ermöglichen Kaltwärmenetze Industrie- und Gewerbeunternehmen mit Abwärmepotential wie beispielsweise [[Supermarkt|Supermärkten]], [[Rechenzentrum|Rechenzentren]] usw. die unkomplizierte Einspeisung von thermischer Energie ohne großes finanziellen Investitionsrisiko, da auf dem Temperaturniveau von Kaltwärmenetzen eine direkte Wärmeeinspeisung ohne Wärmepumpe möglich ist.<ref name="Buffa" /> |

|||

=== (Seasonal) heat storage === |

|||

Eine weitere Wärmequelle kann auch die Rücklaufleitung konventioneller Fernwärmenetze sein.<ref name="Buffa" /> Sofern die Betriebstemperatur des Kaltwärmenetzes niedriger ist als die Bodentemperatur kann auch das Netz selbst Wärme aus dem umliegenden Boden aufnehmen. In diesem Fall wirkt dann das Netz wie eine Art [[Erdwärmekollektor]].<ref name="Brennenstuhl">{{Literatur | Autor=Marcus Brennenstuhl et al. | Titel=Report on a Plus-Energy District with Low-Temperature DHC Network, Novel Agrothermal Heat Source, and Applied Demand Response | Sammelwerk=Applied Sciences | Band=9 | Nummer= | Datum=2019 | Seiten= | DOI=10.3390/app9235059}} </ref> |

|||

[[File:Vertical heatpump collector.svg|thumb|Function of a geothermal heat collector. These collectors can also be used for seasonal storage]] |

|||

[[Seasonal thermal energy storage|Heat storage]] in the form of seasonal storage is a key element of cold local heating systems.<ref name="Boesten">{{citation|author=Stef Boesten |display-authors=et al |periodical=Advances in Geoscience|title=5th generation district heating and cooling systems as a solution for renewable urban thermal energy supply|volume=49|at=pp. 129–136|date=2019|doi=10.5194/adgeo-49-129-2019 |

|||

|bibcode=2019AdG....49..129B |doi-access=free}}</ref> To balance seasonal fluctuations in heat production and consumption, many cold heating systems are built with seasonal heat storage. This is particularly suitable where the structure of the consumers/prosumers does not lead to a largely balanced heat and cooling demand or where there is no sufficient heat source available all year round. Aquifer reservoirs and storage via borehole fields are well suited.<ref name="Buffa" /> These make it possible to store excess heat from the summer half of the year, e.g. from cooling, but also from other heat sources and thus heat up the ground. During the heating period, the process is then reversed and heated water is pumped and fed into the cold heat network.<ref name="Pellegrini" /> Other types of heat storage are also possible, however. For example, a cold heating network in Fischerbach uses an ice storage.<ref name="Buffa" /> |

|||

=== |

=== Heat network === |

||

Cold local heating systems allow a variety of network configurations. A rough distinction can be made between open systems, in which water is fed in, passed through the network where it is supplied to the respective consumers and finally released into the environment, and closed systems, in which a carrier fluid, usually [[brine]], circulates in a circuit. The systems can also be differentiated according to the number of pipelines used. Depending on the respective conditions, configurations with one to four pipes are possible: |

|||

[[Datei:Vertical heatpump collector.svg|mini|Funktionsweise eines Erdwärmekollektors. Diese Kollektoren können ebenfalls zur saisonalen Speicherung dienen]] |

|||

Wärmespeicher in Form von saisonalen Speichern stellen ein Schlüsselelement von kalten Nahwärmesystemen dar.<ref name="Boesten">{{Literatur | Autor=Stef Boesten et al. | Titel=5th generation district heating and cooling systems as a solution for renewable urban thermal energy supply | Sammelwerk=Advances in Geoscience | Band=49 | Nummer= | Datum=2019 | Seiten=129–136 | DOI=10.5194/adgeo-49-129-2019}} </ref> Zum Ausgleich saisonaler Schwankungen von Wärmeproduktion und Abnahme werden viele Kaltwärmesysteme mit einem saisonalen [[Wärmespeicher]] errichtet. Dies bietet sich vor allem dort an, wo die Struktur der Abnehmer/Prosumer nicht zu einem weitgehend ausgeglichenen Wärme- und Kühlbedarf über führt oder eine ganzjährig ausreichende Wärmequelle vorhanden ist. Gut geeignet sind [[Aquiferspeicher]] und die Speicherung über Bohrlochfelder.<ref name="Buffa" /> Diese ermöglichen, überschüssige Wärme aus dem Sommerhalbjahr, z. B. aus der Kühlung, aber auch von anderen Wärmequellen einzuspeichern und damit den Boden aufzuheizen. In der Heizperiode wird dann der Prozess umgekehrt und erwärmtes Wasser gefördert und in das Kaltwärmenetz eingespeist.<ref name="Pellegrini" /> Möglich sind jedoch auch weitere Arten von Wärmespeichern. So nutzt beispielsweise ein Kaltwärmenetz in [[Fischerbach]] einen [[Wärmepumpenheizung#Solar-Eis-Speicher-Wärmepumpe / Latent-Wärmepumpe / Direktverdampfer-Wärmepumpe|Eisspeicher]].<ref name="Buffa" /> |

|||

* Single-pipe systems are usually used in open systems that use surface or ground water as a heat source and release it back into the environment after flowing through the heating network. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* In two-pipe systems, both pipes are operated at different temperatures. In heating operation, the warmer of the two serves as a heat source for the heat pumps of the consumers, while the colder one absorbs the transfer medium cooled by the heat pump. In cooling mode, the colder one serves as the source, the heat produced by the heat pump is fed into the warmer pipe. |

|||

Kalte Nahwärmesysteme erlauben eine Vielzahl von Netzkonfigurationen. Grob unterscheiden lassen sich offene Systeme, bei denen Wasser eingespeist, durch das Netz geschleust, wo es dann die jeweiligen Verbraucher versorgt, und schließlich in die Umwelt abgegeben wird, und geschlossene Systeme, bei denen eine Überträgerflüssigkeit, meist [[Sole]], in einem Kreislauf zirkuliert. Weiter lassen sich die Systeme nach der Zahl der verwendeten Rohrleitungen unterscheiden. Abhängig von den jeweiligen Gegebenheiten sind Konfiguration mit einer bis vier Röhren möglich: |

|||

* Three-pipe systems work similarly to two-pipe systems, but there is also a third pipe that is operated with warmer water, so that (at least in the case of heating systems with a low flow temperature, such as underfloor heating) heating can take place without using the heat pump. The heat is usually transferred via [[heat exchanger]]s. Depending on the temperature, the heat is then fed back into the warmer or colder pipe after use. Alternatively, the third pipe can also be used as a cooling pipe for direct cooling via heat exchanger. |

|||

* Four-pipe systems function like three-pipe systems, except that there is one pipe each for direct heating and cooling. In this way, [[energy cascade]]s can be realised. |

|||

In general, the pipelines of cold heating networks can be designed in a simpler and cheaper way than in warm/hot district heating systems. Due to the low operating temperatures, there is no thermomechanical stress, which allows the use of ordinary [[polyethylene]] pipes without insulation, as used for drinking water supply. This allows both a quick and cost-effective installation and quick adaptation to different network geometries. It also eliminates the need for expensive X-ray or ultrasound examinations of the pipes, the welding of individual pipes and the time-consuming on-site insulation of connecting pieces. However, compared to conventional district heating pipes, pipes with a larger diameter must be used to transport the same amount of heat. The energy requirement of the pumps is also higher due to the larger volumes. On the other hand, cold local heating systems can potentially be installed where the heat demand of the connected buildings is too low to operate a conventional heating network. In 2018, for example, 9 out of 16 systems for which sufficient data was available were below the threshold of 1.2 kW heat output/m grid length, which is considered the lower limit for the economic operation of conventional "warm" local heating systems.<ref name="Buffa" /> |

|||

* Einrohrsysteme werden üblicherweise bei offenen Systemen verwendet, die Oberflächen- oder Grundwasser als Wärmequelle nutzen und dieses nach Durchströmen des Wärmenetzes wieder in die Umwelt abgeben. |

|||

* In Zweirohrsystemen werden beide Rohre mit unterschiedlichen Temperaturen betrieben. Im Heizbetrieb dient die wärmere der beiden als Wärmequelle für die Wärmepumpen der Abnehmer, die kältere nimmt das durch die Wärmepumpe abgekühlte Übertragungsmedium wieder auf. Im Kühlbetrieb dient die kältere als Quelle, die von der Wärmepumpe erzeugte Wärme wird in die wärmere Leitung eingespeist. |

|||

* Dreirohrsysteme funktionieren ähnlich wie Zweirohrsysteme, jedoch existiert noch eine dritte Leitung, die mit wärmeren Wasser betrieben wird, sodass (zumindest bei Heizungen mit niedriger Vorlauftemperatur wie z. B. [[Fußbodenheizung]]en der Fall) die Heizung ohne Einsatz der Wärmepumpe erfolgen kann. Die Wärmeübertragung erfolgt dabei meist über [[Wärmetauscher]]. Abhängig von der Temperatur erfolgt die Rückspeisung nach Nutzung dann in die wärmere oder kälteren Leitung. Alternativ kann die dritte Leitung auch als Kälteleitung zur direkten Kühlung via Wärmetauscher genutzt werden. |

|||

* Vierrohrsysteme fungieren wie Dreirohrsysteme, nur dass je eine Leitung zur direkten Heizung und Kühlung vorhanden ist. Auf diese Weise lassen sich Energiekaskaden realisieren. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Generell gilt für die Leitungen von Kaltwärmenetzen, dass die Rohrleitungen im Gegensatz zu einfacher und günstiger gestaltet werden können als bei warmen/heißen Fernwärmesystemen. Durch die niedrigen Betriebstemperaturen kommt es nicht zu thermomechanischem Stress, was den Einsatz von gewöhnlichen [[Polyethylen]]-Röhren ohne Isolierung erlaubt, wie sie auch bei der Trinkwasserversorgung eingesetzt werden. Dies erlaubt sowohl eine schnelle als auch kostengünstige Verlegung, sowie schnelle Anpassung an unterschiedliche Netzgeometrien. Ebenfalls entfallen dadurch teure Röntgen- oder Ultraschalluntersuchungen der Röhren, die Verschweißung von einzelnen Röhren sowie die aufwändige Vor-Ort-Isolierung von Verbindungsstücken. Allerdings müssen verglichen mit konventionellen Fernwärmeleitungen Rohr mit größerem Durchmesser verwendet werden, um die gleiche Wärmemenge transportieren zu können. Auch ist der Energiebedarf der Pumpen aufgrund der größeren Volumens höher. Hingegen können kalte Nahwärmesysteme potentiell auch dort errichtet werden, wo der Wärmebedarf der angeschlossenen Gebäude zu gering für den Betrieb eines herkömmlichen Wärmenetzes ist. So lagen 2018 9 von 16 Systemen, für die ausreichend Daten vorhanden waren, unter der Schwelle von 1,2 kW Heizleistung/m Netzlänge, die als Untergrenze für den wirtschaftlichen Betrieb konventioneller "warmer" Nahwärmesystem angesehen wird.<ref name="Buffa" /> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Compared to conventional "hot" district heating networks, the [[district heating substation|substation]] of cold local heating systems is more complicated, takes up more space and is therefore more expensive. A heat pump as well as a direct hot water storage tank must be installed at each connected consumer or prosumer. The heat pump is usually designed as an electrically driven water-to-water heat pump and is also often physically separated from the cold heat network by a heat exchanger. The heat pump raises the temperature to the level required to heat the dwelling and produces hot water,<ref name="Buffa" /> but it can also be used to cool the house and feed the heat produced there into the heating network, unless cooling is done directly without the use of a heat pump. A back-up system such as a [[heating element]] can also be installed. A heat storage tank for the heating system can also be installed, which enables more flexible operation of the heat pump.<ref name="Pellegrini" /> Such heat storage tanks also help to keep the heat pump small, which in turn reduces installation costs.<ref name="Boesten" /> |

|||

== Role in future energy systems == |

|||

=== Übergabestation === |

|||

Low-temperature heating networks, which include cold local heating systems, are regarded as a central element for the [[decarbonisation]] of heat supply in the context of [[energy transition|energy system transformation]] and [[Climate change mitigation]].<ref>{{citation|author=Dietmar Schüwer|periodical=[[Energiewirtschaftliche Tagesfragen]] |url=https://epub.wupperinst.org/files/6901/6901_Schuewer.pdf |title=Konversion der Wärmeversorgungsstrukturen |volume=67|issue=11|pages=21–25|date=2017|language=German |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

}}</ref> Local and district heating systems have various advantages compared to individual heating systems: These include, for example, the higher efficiency of the systems, the possibility of using combined heat and power generation and exploiting previously unused waste heat potentials.<ref name="Brennenstuhl" /> In addition, they are seen as an important approach to increasing the use of renewable energy sources<ref name="Pellegrini" /> and reducing primary energy requirements and local emissions in heat generation. By dispensing with combustion technologies for feeding into the cold heat network, [[carbon dioxide]] emissions and [[air pollution|local pollutant]] emissions can be completely avoided.<ref name="Buffa" /> Cold heat networks are also seen as an opportunity to build up heat networks in the future that are fed [[100% renewable energy|100% by renewable energy sources]].<ref name="Boesten" /> |

|||

Gegenüber herkömmlicher "heißer" Fernwärmenetzen fällt die Übergabestation von kalten Nahwärmesystemen komplizierter, platzaufwändiger und dementsprechend teurer aus. So muss bei jedem angeschlossenen Abnehmer bzw. [[Prosumer]] eine Wärmepumpe sowie ein [[Wärmespeicher]] für Warmwasser installiert werden. Die Wärmepumpe ist üblicherweise als elektrisch angetriebene Wasser-Wasser-Wärmepumpe ausgeführt und wird zudem oft über einen Wärmetauscher physisch vom Kaltwärmenetz getrennt. Die Wärmepumpe hebt die Temperatur auf das nötige Niveau zum Beheizen der Wohnung und erzeugt das Warmwasser.<ref name="Buffa" /> Sie kann ebenso aber zum Kühlen des Hauses genutzt werden und die dort anfallende Wärme ins Wärmenetz einspeisen, sofern nicht direkt ohne Wärmepumpeneinsatz gekühlt wird. Zudem kann noch ein Back-Up-System wie z. B. ein [[Heizstab]] installiert sein. Ebenfalls kann ein Wärmespeicher für das Heizungssystem installiert werden, was einen flexibleren Betrieb der Wärmepumpe ermöglicht.<ref name="Pellegrini" /> Solche Wärmespeicher helfen ebenfalls dabei, die Leistung der Wärmepumpe klein zu halten, was wiederum die Installationskosten senkt.<ref name="Boesten" /> |

|||

[[File:Sektorkopplung mit Power-to-X.jpg|thumb|The extensive electrification of the heat sector is a central component of [[sector coupling]]]] |

|||

Another promising approach is the use of cold local heating systems and other heat pump heating systems for [[sector coupling]]. Thus, [[power-to-heat]] technologies on the one hand use electrical energy for heating, and on the other hand the heating sector can help to provide the system services to compensate for the fluctuating green electricity production in the electricity sector. Cold local heating networks can thus contribute to load control via heat pumps and, together with other storage systems, help to ensure security of supply.<ref name="Brennenstuhl" /><ref name="Buffa" /> |

|||

If the roofs of the buildings supplied are equipped with [[photovoltaic]] systems, it is also possible to obtain part of the electricity required for the heat pumps from the roof of the consumer. For example, 20 PlusEnergy houses have been built in Wüstenrot, all of which are equipped with photovoltaic systems, a solar battery and a heat storage tank for the highest possible degree of self-supply through flexible operation of the heat pump.<ref>{{citation|surname1=Laura Romero Rodríguez |display-authors=et al |periodical=[[Applied Energy]]|title=Contributions of heat pumps to demand response: A case study of a plus-energy dwelling|volume=214|pages=191–204|date=2018|doi=10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.01.086 |

|||

== Rolle im zukünftigen Energiesystem == |

|||

|hdl=11441/76023 |url=https://idus.us.es/xmlui/handle//11441/76023 }}</ref> |

|||

==Notes== |

|||

Niedertemperatur-Wärmenetze, zu denen Kalte Nahwärmesysteme zählen, gelten als zentrales Element für die [[Dekarbonisierung]] der Wärmeversorgung im Rahmen der [[Energiewende]] und des [[Klimaschutz]]es.<ref>{{Literatur | Autor=Dietmar Schüwer | Titel=[https://epub.wupperinst.org/files/6901/6901_Schuewer.pdf Konversion der Wärmeversorgungsstrukturen] | Sammelwerk=[[Energiewirtschaftliche Tagesfragen]] | Band=67 | Nummer=11 | Datum=2017 | Seiten=21-25 | DOI=}} </ref> Nah- und Fernwärmesysteme haben verglichen mit Einzelheizungen verschiedene Vorteile: Hierzu zählen z. B. die höheren Wirkungsgrade der Anlagen, die Möglichkeit, [[Kraft-Wärme-Kopplung]] zu nutzen und bisher ungenutzte [[Abwärme]]potentiale auszuschöpfen zu nutzen.<ref name="Brennenstuhl" /> Zudem werden sie als wichtiger Lösungsansatz gesehen um die Nutzung [[erneuerbare Energien|erneuerbarer Energien]] zu steigern<ref name="Pellegrini" /> und den Primärenergiebedarf und die lokalen Emissionen bei der Wärmegewinnung zu senken. Bei Verzicht auf Verbrennungstechnologien zur Einspeisung in das Kaltwärmenetz können [[Kohlendioxid]]emissionen und Schadstoffemissionen vor Ort komplett vermieden werden.<ref name="Buffa" /> Kalte Wärmenetze werden zudem als Möglichkeit gesehen, zukünftig Wärmenetze aufzubauen, die zu 100 % mittels erneuerbarer Energien gespeist werden.<ref name="Boesten" /> |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

[[Datei:Sektorkopplung mit Power-to-X.jpg|mini|Die weitgehende Elektrifizierung des Wärmesektors ist ein zentraler Baustein der [[Sektorkopplung]]]] |

|||

Als vielversprechender Ansatz gilt ebenfalls die Nutzung von kalten Nahwärmesystemen und anderen Wärmepumpenheizungen zur [[Sektorkopplung]]. So wird durch [[Power-to-Heat]]-Technologien einerseits elektrische Energie zum Heizen verwendet, andererseits kann auf diese Weise der Wärmesektor dabei helfen, die Systemdienstleistungen zu erbringen, um die schwankende Ökostromerzeugung im Stromsektor auszugleichen. Kalte Nahwärmenetze können somit über die Wärmepumpen zur [[Laststeuerung]] beitragen und dabei zusammen mit weiteren Speichern dabei helfen, die Versorgungssicherheit zu gewährleisten.<ref name="Brennenstuhl" /><ref name="Buffa" /> |

|||

== Further reading == |

|||

Sofern die Dächer der versorgten Gebäude mit [[Photovoltaik]]-Anlagen ausgestattet sind, ist es zudem möglich, einen Teil des Strombedarfs für die Wärmepumpen vom eigenen Dach zu beziehen. Beispielsweise wurden in Wüstenrot 20 [[Plusenergiehaus|Plusenergiehäuser]] errichtet, die allesamt mit Photovoltaik-Anlagen, einer [[Solarbatterie]] und einem Wärmespeicher für möglichst hohe Eigenversorgungsgrad durch flexiblen Betrieb der Wärmepumpe ausgestattet sind.<ref>{{Literatur | Autor=Laura Romero Rodríguez et al. | Titel=Contributions of heat pumps to demand response: A case study of a plus-energy dwelling | Sammelwerk=[[Applied Energy]] | Band=214 | Nummer= | Datum=2018 | Seiten=191-204 | DOI=10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.01.086}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|doi-access=free}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|doi-access=free|hdl=11585/624860|hdl-access=free}} |

|||

* Listing of scientific literature on [http://mwirtz.com/5gdhc_literature.html mwirtz.com/5gdhc_literature.html]. Retrieved on September 13, 2020. |

|||

== External links to examples == |

|||

== Literatur == |

|||

* [https://www.mijnwater.com Mijnwater Heerlen] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* [https://www.schleswiger-stadtwerke.de/content/produkte/schleswigerNAHWAERME/index.php Schleswig Kalte Nahwärme] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210117115858/https://www.schleswiger-stadtwerke.de/content/produkte/schleswigerNAHWAERME/index.php |date=2021-01-17 }} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

* [https://www.npro.energy/main/en/5gdhc-networks/5gdhc-districts List of cold district heating networks] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | * [https://www.ee-news.ch/de/article/42466/kalte-nahwarme-in-dorsten-pionierprojekt-mit-warmepumpen-lauft-seit-vier-jahrzehnten-und-bleibt-weiter-im-rennen ''Kalte Nahwärme in Dorsten: Pionierprojekt mit Wärmepumpen läuft seit vier Jahrzehnten und bleibt weiter im Rennen'']. In: ''EE-News'', 14 November 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2020. |

||

[[Category:District heating]] |

|||

== Weblinks == |

|||

[[Category:Cooling technology]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | * [https://www.ee-news.ch/de/article/42466/kalte-nahwarme-in-dorsten-pionierprojekt-mit-warmepumpen-lauft-seit-vier-jahrzehnten-und-bleibt-weiter-im-rennen ''Kalte Nahwärme in Dorsten: Pionierprojekt mit Wärmepumpen läuft seit vier Jahrzehnten und bleibt weiter im Rennen'']. In: ''EE-News'', 14 |

||

== Einzelnachweise == |

|||

<references /> |

|||

[[Kategorie:Fernwärme]] |

|||

[[Kategorie:Klimatechnik]] |

|||

[[Kategorie:Energiesparendes Bauen]] |

|||

[[Kategorie:Erneuerbare Energien]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 02:46, 4 January 2024

Cold district heating is a technical variant of a district heating network that operates at low transmission temperatures well below those of conventional district heating systems and can provide both space heating and cooling. Transmission temperatures in the range of approx. 10 to 25 °C are common, allowing different consumers to heat and cool simultaneously and independently of each other. Hot water is produced and the building heated by water heat pumps, which obtain their thermal energy from the heating network, while cooling can be provided either directly via the cold heat network or, if necessary, indirectly via chillers. Cold local heating is sometimes also referred to as an anergy network. The collective term for such systems in scientific terminology is 5th generation district heating and cooling. Due to the possibility of being operated entirely by renewable energies and at the same time contributing to balancing the fluctuating production of wind turbines and photovoltaic systems, cold local heating networks are considered a promising option for a sustainable, potentially greenhouse gas and emission-free heat supply.

Terms[edit]

As of 2019, the fifth generation heating networks described here have not yet been given a uniform name, and there are also various definitions for the general technical concept. In the English language technical literature the terms Low temperature District Heating and Cooling (LTDHC), Low temperature networks (LTN), Cold District Heating (CHD) and Anergy networks or Anergy grid are used. In addition, some publications have definitional conflicts in the delimitation to "warm" district heating networks, because certain authors consider Low temperature District Heating and Cooling as well as Ultra-low temperature District Heating as subforms of 4th generation district heating. In addition, the definition of so-called low-ex networks allows to classify them as both fourth and fifth generation.[1]

History[edit]

The first cold district heating network is the heating network in Arzberg in Upper Franconia, Germany. In the Arzberg power station there, which has since been shut down, uncooled cooling water was taken from between the turbine condenser and the cooling tower and piped to various buildings, where it was then used as a heat source for heat pumps. This was used to heat the school and the swimming pool in addition to various residential buildings and commercial enterprises.[2]

Another very early plant was put into operation in Wulfen in 1979. There, 71 buildings were supplied with heat energy, which was taken from the groundwater. Finally, in 1994, the first cold heating network was opened, using waste heat from an industrial company, a textile company. Also in 1994 (according to Pellegrini and Bianchini already in 1991 [3]) a cold local heating network was built in the Swiss village Oberwald, which is operated with seepage water from the Furka base tunnel.[1]

As of January 2018, a total of 40 schemes were in operation in Europe, 15 each in Germany and Switzerland. Most of the projects were pilot plants with a heat output of several 100 kWth up to the single-digit MW range, the largest plant had an output of approx. 10 MWth. In the 2010s about three plants per year were added.[1]

Concept[edit]

Cold heat networks are heat networks that are operated at very low temperatures (usually between 10 and 25 °C). They can be fed from a variety of frequently regenerative heat sources and allow the simultaneous production of heat and cold. Since the operating temperatures are not sufficient for the production of hot water and heating heat, the temperature at the consumer is raised to the required level by means of heat pumps. In the same way, cold can be produced and the waste heat can be fed back into the heating network. In this way, connected consumers are not only customers, but can also act as prosumers, who can either consume or produce heat depending on the circumstances.[1]

The concept of cold local heating networks is derived from groundwater heat pumps as well as open-loop heat pumps. While the former are mainly used to supply individual houses, the latter are often found in commercial buildings which have both heating and cooling needs and have to meet these needs in parallel. Cold local heating extends this concept to individual residential areas or districts. Like ordinary geothermal heat pumps, cold local heating networks have the advantage over air heat pumps of operating more efficiently due to the lower temperature difference between the heat source and the heating temperature. However, compared to geothermal heat pumps, cold local heating networks have the additional advantage that even in urban areas, where space problems often prevent the use of geothermal heat pumps, heat can be stored seasonally via central heat storage, and in addition, the different load profiles of different buildings may allow a balance between heating and cooling requirements.[1]

Cold district heating is particularly suitable where there are different types of buildings (residential, commercial, supermarkets, etc.) and therefore there is a demand for both heating and cooling, enabling energy balancing over short or long periods of time. Alternatively, seasonal heat storage systems allow for a balance of energy supply and demand. By using different (waste) heat sources and combining heat sources and heat sinks, synergies can also be created and the heat supply can be further developed in the direction of a circular economy. In addition, the low operating temperature of the cold-heating networks makes it possible to feed otherwise hardly usable low-temperature waste heat into the network in an uncomplicated manner. At the same time, the low operating temperature significantly reduces the heat losses of the heating network, which limits the energy losses, especially in summer, when there is little demand for heat. The annual performance factor of heat pumps is also relatively high, especially compared to air-sourced heat pumps. A study of 40 systems commissioned up to 2018 showed that the heat pumps achieved an seasonal COP of at least 4 for the majority of the systems studied; the highest seasonal COP values were about 6.[1]

Technologically, cold heat networks are part of the concept of smart heat networks.[1]

Components[edit]

Heat sources[edit]

Various heat sources can be used as energy suppliers for the cold heating network, in particular renewable sources such as the ground, water, commercial and industrial waste heat, solar thermal energy and ambient air, which can be used individually or in combination.[1] Due to the generally modular design of cold local heating networks, new heat sources can be gradually developed as the network is further expanded, so that larger heating networks can be fed from a variety of different sources.[4]

In practice almost inexhaustible sources are e.g. sea water, rivers, lakes or groundwater. Of the 40 cold heating networks in operation in Europe as of January 2018, 17 used water bodies or groundwater as a heat source. The second most important heat source was geothermal energy. This is usually accessed via geothermal boreholes using vertical borehole heat exchangers. However, it is also possible to use surface collectors such as agrothermal collectors. In this case, horizontal collectors are ploughed into agricultural land at a depth of 1.5 to 2 m, i.e. below the working depth of agricultural machines, which can extract heat from the soil as required. This concept, which allows further agricultural use, has been realized, for example, in a cold heat network in the German town Wüstenrot.[1]

In addition, there are cold-heating networks that extract geothermal energy from tunnels and abandoned coal mines. Waste heat from industrial and commercial enterprises can also be used. For example, two cold-heating networks in Aurich and Herford use waste heat from dairies and another plant in Switzerland uses waste heat from a biomass power plant, while another cold-heating network uses waste heat from a textile company. Other possible heat sources include solar thermal energy (especially for regenerating geothermal sources and charging storage tanks), large heat pumps that use environmental heat, the sewage system, combined heat and power plants and biomass- or fossil-fired peak load boilers to support other heat sources. The low operating temperatures of cold-heating networks are particularly favourable to solar thermal systems, CHP units and waste heat recovery, as these can operate at maximum efficiency under these conditions. At the same time, cold heating networks enable industrial and commercial companies with waste heat potential, such as supermarkets and data centres, to feed thermal energy into the grid without any major financial investment risk, since at the temperature level of cold heating networks, direct heat feed is possible without a heat pump.[1]

Another heat source can also be the return line of conventional district heating networks.[1] If the operating temperature of the cold heating network is lower than the soil temperature, the network itself can also absorb heat from the surrounding soil. In this case the network then acts as a kind of geothermal collector.[5]

(Seasonal) heat storage[edit]

Heat storage in the form of seasonal storage is a key element of cold local heating systems.[4] To balance seasonal fluctuations in heat production and consumption, many cold heating systems are built with seasonal heat storage. This is particularly suitable where the structure of the consumers/prosumers does not lead to a largely balanced heat and cooling demand or where there is no sufficient heat source available all year round. Aquifer reservoirs and storage via borehole fields are well suited.[1] These make it possible to store excess heat from the summer half of the year, e.g. from cooling, but also from other heat sources and thus heat up the ground. During the heating period, the process is then reversed and heated water is pumped and fed into the cold heat network.[3] Other types of heat storage are also possible, however. For example, a cold heating network in Fischerbach uses an ice storage.[1]

Heat network[edit]

Cold local heating systems allow a variety of network configurations. A rough distinction can be made between open systems, in which water is fed in, passed through the network where it is supplied to the respective consumers and finally released into the environment, and closed systems, in which a carrier fluid, usually brine, circulates in a circuit. The systems can also be differentiated according to the number of pipelines used. Depending on the respective conditions, configurations with one to four pipes are possible:

- Single-pipe systems are usually used in open systems that use surface or ground water as a heat source and release it back into the environment after flowing through the heating network.

- In two-pipe systems, both pipes are operated at different temperatures. In heating operation, the warmer of the two serves as a heat source for the heat pumps of the consumers, while the colder one absorbs the transfer medium cooled by the heat pump. In cooling mode, the colder one serves as the source, the heat produced by the heat pump is fed into the warmer pipe.

- Three-pipe systems work similarly to two-pipe systems, but there is also a third pipe that is operated with warmer water, so that (at least in the case of heating systems with a low flow temperature, such as underfloor heating) heating can take place without using the heat pump. The heat is usually transferred via heat exchangers. Depending on the temperature, the heat is then fed back into the warmer or colder pipe after use. Alternatively, the third pipe can also be used as a cooling pipe for direct cooling via heat exchanger.

- Four-pipe systems function like three-pipe systems, except that there is one pipe each for direct heating and cooling. In this way, energy cascades can be realised.

In general, the pipelines of cold heating networks can be designed in a simpler and cheaper way than in warm/hot district heating systems. Due to the low operating temperatures, there is no thermomechanical stress, which allows the use of ordinary polyethylene pipes without insulation, as used for drinking water supply. This allows both a quick and cost-effective installation and quick adaptation to different network geometries. It also eliminates the need for expensive X-ray or ultrasound examinations of the pipes, the welding of individual pipes and the time-consuming on-site insulation of connecting pieces. However, compared to conventional district heating pipes, pipes with a larger diameter must be used to transport the same amount of heat. The energy requirement of the pumps is also higher due to the larger volumes. On the other hand, cold local heating systems can potentially be installed where the heat demand of the connected buildings is too low to operate a conventional heating network. In 2018, for example, 9 out of 16 systems for which sufficient data was available were below the threshold of 1.2 kW heat output/m grid length, which is considered the lower limit for the economic operation of conventional "warm" local heating systems.[1]

Substation[edit]

Compared to conventional "hot" district heating networks, the substation of cold local heating systems is more complicated, takes up more space and is therefore more expensive. A heat pump as well as a direct hot water storage tank must be installed at each connected consumer or prosumer. The heat pump is usually designed as an electrically driven water-to-water heat pump and is also often physically separated from the cold heat network by a heat exchanger. The heat pump raises the temperature to the level required to heat the dwelling and produces hot water,[1] but it can also be used to cool the house and feed the heat produced there into the heating network, unless cooling is done directly without the use of a heat pump. A back-up system such as a heating element can also be installed. A heat storage tank for the heating system can also be installed, which enables more flexible operation of the heat pump.[3] Such heat storage tanks also help to keep the heat pump small, which in turn reduces installation costs.[4]

Role in future energy systems[edit]

Low-temperature heating networks, which include cold local heating systems, are regarded as a central element for the decarbonisation of heat supply in the context of energy system transformation and Climate change mitigation.[6] Local and district heating systems have various advantages compared to individual heating systems: These include, for example, the higher efficiency of the systems, the possibility of using combined heat and power generation and exploiting previously unused waste heat potentials.[5] In addition, they are seen as an important approach to increasing the use of renewable energy sources[3] and reducing primary energy requirements and local emissions in heat generation. By dispensing with combustion technologies for feeding into the cold heat network, carbon dioxide emissions and local pollutant emissions can be completely avoided.[1] Cold heat networks are also seen as an opportunity to build up heat networks in the future that are fed 100% by renewable energy sources.[4]

Another promising approach is the use of cold local heating systems and other heat pump heating systems for sector coupling. Thus, power-to-heat technologies on the one hand use electrical energy for heating, and on the other hand the heating sector can help to provide the system services to compensate for the fluctuating green electricity production in the electricity sector. Cold local heating networks can thus contribute to load control via heat pumps and, together with other storage systems, help to ensure security of supply.[5][1]

If the roofs of the buildings supplied are equipped with photovoltaic systems, it is also possible to obtain part of the electricity required for the heat pumps from the roof of the consumer. For example, 20 PlusEnergy houses have been built in Wüstenrot, all of which are equipped with photovoltaic systems, a solar battery and a heat storage tank for the highest possible degree of self-supply through flexible operation of the heat pump.[7]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Simone Buffa; et al. (2019), "5th generation district heating and cooling systems: A review of existing cases in Europe", Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 104, pp. 504–522, doi:10.1016/j.rser.2018.12.059

- ^ Leonhard Müller: Handbuch der Elektrizitätswirtschaft: Technische, wirtschaftliche und rechtliche Grundlagen. Berlin/Heidelberg 1998, p 266f.

- ^ a b c d Marco Pellegrini; Augusto Bianchini (2018), "The Innovative Concept of Cold District Heating Networks: A Literature Review", Energies, vol. 11, p. 236, doi:10.3390/en11010236, hdl:11585/624860

- ^ a b c d Stef Boesten; et al. (2019), "5th generation district heating and cooling systems as a solution for renewable urban thermal energy supply", Advances in Geoscience, vol. 49, pp. 129–136, Bibcode:2019AdG....49..129B, doi:10.5194/adgeo-49-129-2019

- ^ a b c Marcus Brennenstuhl; et al. (2019), "Report on a Plus-Energy District with Low-Temperature DHC Network, Novel Agrothermal Heat Source, and Applied Demand Response", Applied Sciences, vol. 9, no. 23, p. 5059, doi:10.3390/app9235059

- ^ Dietmar Schüwer (2017), "Konversion der Wärmeversorgungsstrukturen" (PDF), Energiewirtschaftliche Tagesfragen (in German), vol. 67, no. 11, pp. 21–25

- ^ Laura Romero Rodríguez; et al. (2018), "Contributions of heat pumps to demand response: A case study of a plus-energy dwelling", Applied Energy, vol. 214, pp. 191–204, doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.01.086, hdl:11441/76023

Further reading[edit]

- Simone Buffa; et al. (2019), "5th generation district heating and cooling systems: A review of existing cases in Europe", Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 104, pp. 504–522, doi:10.1016/j.rser.2018.12.059

- Marco Pellegrini; Augusto Bianchini (2018), "The Innovative Concept of Cold District Heating Networks: A Literature Review", Energies, vol. 11, p. 236, doi:10.3390/en11010236, hdl:11585/624860

- Listing of scientific literature on mwirtz.com/5gdhc_literature.html. Retrieved on September 13, 2020.

External links to examples[edit]

- Mijnwater Heerlen

- Schleswig Kalte Nahwärme Archived 2021-01-17 at the Wayback Machine

- List of cold district heating networks

- »Kaltes« Nahwärmenetz spart 40.000 kg CO2 im Jahr. Energieagentur NRW. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- Kalte Nahwärme in Dorsten: Pionierprojekt mit Wärmepumpen läuft seit vier Jahrzehnten und bleibt weiter im Rennen. In: EE-News, 14 November 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2020.