Anativecantonesespeaker (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{language |

|||

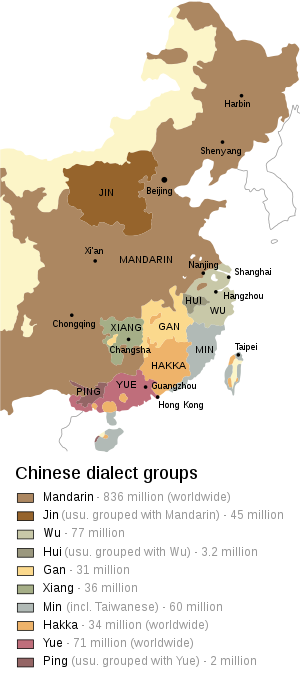

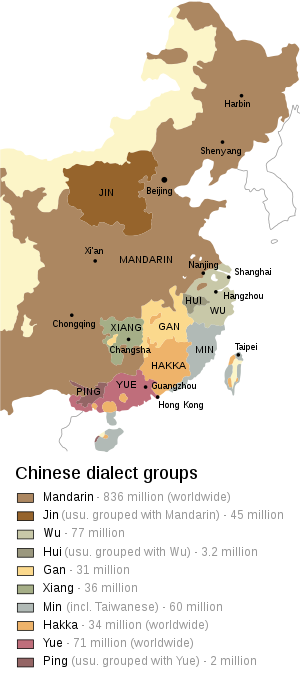

[[Image:Map of sinitic languages-en.svg|right|thumb|300px|Map of eastern [[China]] and [[Taiwan]], showing the historic distribution of the Yue dialects, to which Cantonese ''(Guangzhouhua)'' belongs, in magenta.]] |

|||

|name=Cantonese |

|||

|nativename={{lang|zh-yue-Hant|粵語}} / {{lang|zh-yue-Hans|粤语}} ''Yuhtyúh'' |

|||

|familycolor=Sino-Tibetan |

|||

|states=[[China]]; [[Malaysia]]; [[Singapore]] and countries with [[overseas Chinese]] originating from Cantonese speaking parts of China |

|||

|speakers=70 million (2000)<ref>Li, Ping. [2006] (2006). The Handbook of East Asian Psycholinguistics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521833337. pg 13.</ref> |

|||

|region=the [[Pearl River Delta]] (central [[Guangdong]]; [[Hong Kong]], [[Macau]]); the eastern and southern [[Guangxi]]; parts of [[Hainan]]; [[Singapore]]; [[Malaysia]] ([[Sandakan]], [[Ipoh]], [[Kuala Lumpur]]); [[United Kingdom]]; [[Vancouver]]; [[Toronto]]; [[San Francisco, California|San Francisco]], [[New York City]] |

|||

|fam2=[[Chinese language|Chinese]] |

|||

|nation=[[Hong Kong]] and [[Macau]] ("Chinese" is official; [[Canton dialect|Cantonese]] and [[Standard Mandarin|Mandarin]] are the forms used in government). Recognised regional language in [[Suriname]]. |

|||

|iso1=zh|iso2b=chi|iso2t=zho|iso3=yue}} |

|||

[[Image:Map of sinitic languages-en.svg|right|thumb|300px|Map of eastern [[China]] and [[Taiwan]], showing the historic distribution of the Cantonese language (in magenta).]] |

|||

{{SpecialChars}} |

{{SpecialChars}} |

||

{{IPA notice}} |

{{IPA notice}} |

||

'''Cantonese''' ({{zh-tsp|t=粵語|s=粤语|p=Yuèyǔ}}; Jyutping: Jyut6jyu5) is |

'''Cantonese''' ({{zh-tsp|t=粵語|s=粤语|p=Yuèyǔ}}; Jyutping: Jyut6jyu5) is an independent language or Chinese dialect belonging to the Chinese language(s) group<ref>See [[Identification_of_the_varieties_of_Chinese]].</ref>. |

||

The language is spoken natively in [[Guangdong]], [[Guangxi]] provinces and [[Hong Kong]], [[Macau]] SARs of [[China]]. It is also spoken by many [[Cantonese migrants]] in [[Canada]], [[United States]], [[Australia]], [[Singapore]], [[Malaysia]], [[Europe]] and elsewhere. |

|||

The language is spoken natively in [[Guangdong]], [[Guangxi]] provinces and [[Hong Kong]], [Macau]] SARs of [[China]]. [[Standard Cantonese]] is a ''[[de facto]]'' official [[language]] of [[Hong Kong]] and [[Macau]], and a [[lingua franca]] of [[Guangdong|Guangdong province]] and some neighbouring areas. It is also spoken by many [[overseas Chinese]] of Guangdong, Hong Kong or Macau origin in [[Singapore]], [[Malaysia]], [[Canada]], [[United States]], [[Australia]], [[Europe]] and elsewhere. Many '''Cantonese migrants''' speak [[Taishanese]] dialect. Historically, Cantonese was the most common form of Chinese spoken by overseas Chinese communities in the Western world, although that situation has changed with the increasing importance of Mandarin in the Chinese-speaking world as well as immigration to the West from other countries as well as other parts of China. Cantonese is also known popularly as '''Guangdong speech''' (traditional: 廣東話; simplified: 广东话; pinyin: ''Guǎngdōng huà''; Jyutping: ''Gwong2dong1 wa2'') or '''Plain Speech''' (Chinese: 白話; pinyin: ''báihuà''; Jyutping: ''baak6 wa2'') meaning "[[vernacular Chinese]]." |

|||

[[Standard Cantonese]] is a ''[[de facto]]'' official [[language]] of [[Hong Kong]] and [[Macau]], and a [[lingua franca]] of [[Guangdong|Guangdong province]] and some neighbouring areas. Many '''Cantonese migrants''' speak [[Taishanese]] dialect. |

|||

In narrow sense, the name "Cantonese" may also refer to the [[Standard Cantonese]] which is the de facto standard speech or prestige dialect of Cantonese, spoken in and around the cities of Guangzhou, Hong Kong, and Macau see [[Standard Cantonese]]. In Guangdong province people call it "Capital speech" (traditional: 省城話, simplified: 省城话, [[Jyutping]]: "Saang2sing4 wa2", [[pinyin]]: ''Shěngchéng huà''), or "Canton city speech" (traditional: 廣州話 or "廣府話", simplified: 广州话 or 广府话, [[Jyutping]]: "Gwong2zau1 wa2", [[pinyin]]: ''Guǎngzhōu huà''). To its speakers outside of Mainland China, it may also be usually called "Guangdong speech" or "Cantonese". |

|||

Like other primary branches of [[Chinese language|Chinese]], Cantonese is mutually unintelligible with other Chinese language branches. Whether it is a independent language of Chinese languages family or a dialect of single Chinese language, there are still controversies. |

|||

==Phonology== |

|||

Like any dialect, the [[phonology]] of Cantonese varies among speakers. Unlike [[Standard Mandarin]], there is no official agency to regulate Cantonese, and it is not a standardized language. However, as a prestige dialect, it is the social standard, and is more standardized than any Chinese dialect other than Standard Mandarin and Classical Chinese. Below is the phonology accepted by most scholars and educators, the one usually heard on TV or radio in formal broadcast like news reports. Common variations are also described. |

|||

==Name== |

|||

There are about 630 different extant combinations of [[syllable onset]]s (initial consonants) and [[syllable rime]]s (remainder of the syllable), not counting tones. Some of these, such as {{IPA|/ɛː˨/}} and {{IPA|/ei˨/}} (欸) , {{IPA|/pʊŋ˨/}} (埲), {{IPA|/kʷɪŋ˥/}} (扃) are not common any more; some such as {{IPA|/kʷɪk˥/}} and {{IPA|/kʷʰɪk˥/}} (隙), or {{IPA|/kʷaːŋ˧˥/}} and {{IPA|/kɐŋ˧˥/}} (梗) which has traditionally had two equally correct pronunciations are beginning to be pronounced with only one particular way uniformly by its speakers (and this usually happens because the ''unused'' pronunciation is almost unique to that word alone) thus making the ''unused'' sounds effectively disappear from the language; while some such as {{IPA|/kʷʰɔːk˧/}} (擴), {{IPA|/pʰuːi˥/}} (胚), {{IPA|/jɵy˥/}} (錐), {{IPA|/kɛː˥/}} (痂) have alternative nonstandard pronunciations which have become mainstream (as {{IPA|/kʷʰɔːŋ˧/}}, {{IPA|/puːi˥/}}, {{IPA|/tʃɵy˥/}} and {{IPA|/kʰɛː˥/}} respectively), again making some of the sounds disappear from the everyday use of the language; and yet others such as {{IPA|/faːk˧/}} (謋), {{IPA|/fɐŋ˩/}} (揈), {{IPA|/tɐp˥/}} (耷) have become popularly (but erroneously) believed to be made-up/borrowed words to represent sounds in modern vernacular Cantonese when they have in fact been retaining those sounds before these vernacular usages became popular. |

|||

There are some secular alias of Cantonese language. In Hong Kong and oversea Chinese communities, people usually call the language '''Guangdong speech''' (traditional: 廣東話; simplified: 广东话; pinyin: ''Guǎngdōng huà''; Jyutping: ''Gwong2dong1 wa2''), while in Guangdong and Guangxi, many native Cantonese call it '''Plain Speech''' (Chinese: 白話; pinyin: ''báihuà''; Jyutping: ''baak6 wa2''). |

|||

In narrow sense, the name "Cantonese" may also refer to the [[Standard Cantonese]], which is the de facto standard speech or prestige dialect of Cantonese. Standard Cantonese is spoken in and around the cities of Guangzhou, Hong Kong, and Macau. In Guangdong province people call standard Cantonese "Capital speech" (traditional: 省城話, simplified: 省城话, [[Jyutping]]: "Saang2sing4 wa2", [[pinyin]]: ''Shěngchéng huà''), or "Canton city speech" (traditional: 廣州話 or "廣府話", simplified: 广州话 or 广府话, [[Jyutping]]: "Gwong2zau1 wa2", [[pinyin]]: ''Guǎngzhōu huà''). |

|||

On the other hand, there are new words in Cantonese circulating in Hong Kong which use sounds which never appeared in Cantonese before, such as get1 (note: this is non standard usage as {{IPA|/ɛːt/}} was never an accepted/valid final for sounds in Cantonese, though the final sound {{IPA|/ɛːt/}} has appeared in vernacular Cantonese before this, {{IPA|/pʰɛːt˨/}} - notably in describing the [[measure word]] of gooey or sticky substances such as mud, glue, chewing gum, etc.), the sound is borrowed from the English word ''gag'' to mean the act of amusing others by a (possibly practical) joke. |

|||

Some linguistics use the form "Yue" when referring to Cantonese language. "Yue" is a [[pinyin]] romanization of "粤" or "越" in [[Mandarin]] pronunciation. |

|||

===Initials=== |

|||

[[Initial (linguistics)|Initials]] (or onsets) are initial [[consonant]]s of possible [[syllable]]s. The following is the inventory for Cantonese as represented in [[International Phonetic Alphabet|IPA]]: |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" |

|||

! rowspan="2" colspan="2" | |

|||

!rowspan="2" |[[Labial consonant|Labial]] |

|||

!colspan="2" |[[Coronal consonant|Coronal]] |

|||

!rowspan="2" |[[Palatal consonant|Palatal]] |

|||

!colspan="2" |[[Velar consonant|Velar]] |

|||

!rowspan="2" |[[Glottal consonant|Glottal]] |

|||

|- |

|||

! style="text-align: left; font-size: 80%;" | plain |

|||

! style="text-align: left; font-size: 80%;" | [[Sibilant consonant|sibilant]] |

|||

! style="text-align: left; font-size: 80%;" | plain |

|||

! style="text-align: left; font-size: 80%;" | [[Labial-velar consonant|labialized]] |

|||

|- |

|||

!colspan="2"|[[Nasal consonant|Nasal]] |

|||

|{{IPA|m}} |

|||

|{{IPA|n}} |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

|{{IPA|ŋ}} |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

!rowspan="2" | [[Stop consonant|Stop]] |

|||

!style="text-align: left; font-size: 80%;" | plain |

|||

|{{IPA|p}} |

|||

|{{IPA|t}} |

|||

|{{IPA|ts}} |

|||

| |

|||

|{{IPA|k}} |

|||

|( {{IPA|kʷ}} ) |

|||

|( {{IPA|ʔ}} ) |

|||

|- |

|||

! style="text-align: left; font-size: 80%;" | [[Aspiration (phonetics)|aspirated]] |

|||

|{{IPA|pʰ}} |

|||

|{{IPA|tʰ}} |

|||

|{{IPA|tsʰ}} |

|||

| |

|||

|{{IPA|kʰ}} |

|||

|( {{IPA|kʷʰ}} ) |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

!colspan="2"|[[Fricative consonant|Fricative]] |

|||

|{{IPA|f}} |

|||

| |

|||

|{{IPA|s}} |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

|{{IPA|h}} |

|||

|- |

|||

!colspan="2"|[[Approximant consonant|Approximant]] |

|||

| |

|||

|{{IPA|l}} |

|||

| |

|||

|( {{IPA|j}} ) |

|||

| |

|||

|( {{IPA|w}} ) |

|||

| |

|||

|} |

|||

==Speakers== |

|||

Note the [[aspiration (phonetics)|aspiration]] contrast and the lack of [[phonation]] contrast for [[stop consonant|stops]]. The [[sibilant consonant|sibilant]] [[affricate consonant|affricates]] are grouped with the stops for compactness in displaying the chart. |

|||

The exact number of Cantonese speakers is unknown due to a lack of statistics and census data. The areas with the highest concentration of speakers are [[Guangdong]], some parts of [[Guangxi]] in southern [[mainland China]], [[Hong Kong]], and [[Macau]], with Cantonese speaking minorities in [[Southeast Asia]], [[Canada]], and the [[United States]].<ref name="Lau">Lau, Kam Y. [1999] (1999). Cantonese Phrase book. Lonely planet publishing. ISBN 0864426453.</ref> The Canton–Hong Kong dialect is the [[prestige dialect]] and a ''de facto'' official language of Hong Kong. |

|||

==Dialects== |

|||

Some linguists prefer to analyze {{IPA|/j/}} and {{IPA|/w/}} as part of [[final (linguistics)|finals]] to make them analogous to the {{IPA|/i/}} and {{IPA|/u/}} [[medial (linguistics)|medial]]s in [[Standard Mandarin]], especially in comparative phonological studies. However, since final-heads only appear with [[initial (linguistics)|null initial]], {{IPA|/k/}} or {{IPA|/kʰ/}}, analyzing them as part of the initials greatly reduces the count of finals at the cost of only adding four initials. Some linguists analyze a {{IPA|/ʔ/}} ([[glottal stop]]) when a [[vowel]] other than {{IPA|/i/}}, {{IPA|/u/}} or {{IPA|/y/}} begins a syllable. |

|||

There are numerous Cantonese dialects. The most widely spoken is the [[Guangzhou dialect]], or ''Yuehai,'' generally called "Cantonese", spoken in Canton, Hongkong, and Macau. The Guangzhou dialect is a ''[[lingua franca]]'' of not just [[Guangdong]] province, but also the overseas Cantonese-speaking diaspora. |

|||

There are four major dialect groups of Cantonese: |

|||

The position of the [[coronal consonant|coronals]] varies from [[dental consonant|dental]] to [[alveolar consonant|alveolar]], with {{IPA|/t/}} and {{IPA|/tʰ/}} more likely to be dental. The position of the [[sibilant consonant|sibilants]] {{IPA|/ts/}}, {{IPA|/tsʰ/}}, and {{IPA|/s/}} are usually alveolar ({{IPA|[ts]}}, {{IPA|[tsʰ]}}, and {{IPA|[s]}}), but can be [[postalveolar consonant|postalveolar]] ({{IPA|[tʃ]}}, {{IPA|[tʃʰ]}}, and {{IPA|[ʃ]}}) or [[alveolo-palatal consonant|alveolo-palatal]] ({{IPA|[tɕ]}}, {{IPA|[tɕʰ]}}, and {{IPA|[ɕ]}}), especially before the front high vowels{{IPA|/iː/}}, {{IPA|/ɪ/}}, or {{IPA|/yː/}}. |

|||

*Cantonese, or ''Yuehai,'' which includes the [[Canton dialect]] spoken in Guangzhou, Hong Kong and Macau as well as the dialects of [[Zhongshan]], and [[Dongguan]] |

|||

*''Sìyì'' ({{lang|zh-yue-Hani|四邑}}, ''[[Sze Yup|sei yap]]''), exemplified by [[Taishan dialect]], which was ubiquitous in American [[Chinatown]]s before ''ca'' 1970 |

|||

*[[Gaoyang dialect]], spoken in [[Yangjiang]] |

|||

*''Guinan'' ({{lang|zh-yue-Hani|桂南}}, from [[Guilin]] and [[Nanning]]) spoken widely in Guangxi. |

|||

In Hainan Province, two unclassified dialects are spoken which may be closely related to Cantonese, the Mai dialect and the [[Danzhou dialect]]<ref name = "Thurgood 2006">[http://www.sil.org/asia/philippines/ical/papers/thurgood-LanguageContact.pdf] - |

|||

Thurgood, Graham. 2006. "Sociolinguistics and contact-induced language change: Hainan Cham, Anong, and Phan Rang Cham." Tenth International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics, 17-20 January 2006, Palawan, Philippines. Linguistic Society of the Philippines and SIL International.</ref>. The name "Cantonese" generally refers to the ''Yuehai'' dialect. |

|||

Besides Cantonese, there are three other primary branches of Chinese spoken in Guangdong Province— [[Standard Mandarin]], which is used for official occasions, education, the media, and as a national lingua franca; [[Min Nan]] (Southern Min), spoken in the eastern regions bordering Fujian, such as [[Chaozhou]] and [[Shantou]]; and [[Hakka Chinese|Hakka]], the language of the [[Hakka|Hakka people]]. Standard Mandarin is mandatory through the state education system, but in Cantonese speaking households, Cantonese-language media (Hong Kong films, television serials, and [[Cantopop]]), isolation from the other regions of China, local identity, and the non-Mandarin speaking Cantonese diaspora in Hong Kong and abroad give the language a unique identity. Most [[wuxia]] films from Canton are filmed originally in Cantonese and then dubbed or subtitled in Mandarin, [[English language|English]], or both. |

|||

Some native speakers cannot distinguish between {{IPA|/n/}} and {{IPA|/l/}}, and between {{IPA|/ŋ/}} and the null initial. Usually they pronounce only {{IPA|/l/}} and the null initial. See the discussion on phonological shift below. |

|||

== |

==Phonology== |

||

:''See [[Canton dialect]] and [[Taishanese]] for a discussion of the sounds those dialects.'' |

|||

==Cantonese development and usage== |

|||

[[Final (linguistics)|Finals]] (or rimes) are the remaining part of the syllable after the initial is taken off. There are two kinds of finals in Cantonese, depending on [[vowel length]]. The following chart lists all possible finals in Cantonese as represented in [[International Phonetic Alphabet|IPA]]: |

|||

[[Image:Map of sinitic languages-en.svg|thumb|300px|The area coloured in red shows the Cantonese speaking region in the Greater China.]] |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" |

|||

| |

|||

|colspan=2|{{IPA|aː}} |

|||

|colspan=2|{{IPA|ɛː}} |

|||

|colspan=2|{{IPA|iː}} |

|||

|colspan=2|{{IPA|ɔː}} |

|||

|colspan=2|{{IPA|uː}} |

|||

|colspan=2|{{IPA|œː}} |

|||

|colspan=2|{{IPA|yː}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| |

|||

|Long||Short |

|||

|Long||Short |

|||

|Long||Short |

|||

|Long||Short |

|||

|Long||Short |

|||

|Long||Short |

|||

|Long||Short |

|||

|- |

|||

| -{{IPA|i}} / -{{IPA|y}} |

|||

|{{IPA|aːi}}||{{IPA|ɐi}} |

|||

| ||{{IPA|ei}} |

|||

| || |

|||

|{{IPA|ɔːi}}|| |

|||

|{{IPA|uːi}}|| |

|||

| ||{{IPA|ɵy}} |

|||

| || |

|||

|- |

|||

| -{{IPA|u}} |

|||

|{{IPA|aːu}}||{{IPA|ɐu}} |

|||

|{{IPA|ɛːu}}¹|| |

|||

|{{IPA|iːu}}|| |

|||

| ||{{IPA|ou}} |

|||

| || |

|||

| || |

|||

| || |

|||

|- |

|||

| -{{IPA|m}} |

|||

|{{IPA|aːm}}||{{IPA|ɐm}} |

|||

|{{IPA|ɛːm}}¹|| |

|||

|{{IPA|iːm}}|| |

|||

| || |

|||

| || |

|||

| || |

|||

| || |

|||

|- |

|||

| -{{IPA|n}} |

|||

|{{IPA|aːn}}||{{IPA|ɐn}} |

|||

| || |

|||

|{{IPA|iːn}}|| |

|||

|{{IPA|ɔːn}}|| |

|||

|{{IPA|uːn}}|| |

|||

| ||{{IPA|ɵn}} |

|||

|{{IPA|yːn}}|| |

|||

|- |

|||

| -{{IPA|ŋ}} |

|||

|{{IPA|aːŋ}}||{{IPA|ɐŋ}} |

|||

|{{IPA|ɛːŋ}}|| |

|||

| ||{{IPA|ɪŋ}} |

|||

|{{IPA|ɔːŋ}}|| |

|||

| ||{{IPA|ʊŋ}} |

|||

|{{IPA|œːŋ}}|| |

|||

| || |

|||

|- |

|||

| -{{IPA|p}} |

|||

|{{IPA|aːp}}||{{IPA|ɐp}} |

|||

|{{IPA|ɛːp}}¹|| |

|||

|{{IPA|iːp}}|| |

|||

| || |

|||

| || |

|||

| || |

|||

| || |

|||

|- |

|||

| -{{IPA|t}} |

|||

|{{IPA|aːt}}||{{IPA|ɐt}} |

|||

| || |

|||

|{{IPA|iːt}}|| |

|||

|{{IPA|ɔːt}}|| |

|||

|{{IPA|uːt}}|| |

|||

| ||{{IPA|ɵt}} |

|||

|{{IPA|yːt}}|| |

|||

|- |

|||

| -{{IPA|k}} |

|||

|{{IPA|aːk}}||{{IPA|ɐk}} |

|||

|{{IPA|ɛːk}}|| |

|||

| ||{{IPA|ɪk}} |

|||

|{{IPA|ɔːk}}|| |

|||

| ||{{IPA|ʊk}} |

|||

|{{IPA|œːk}}|| |

|||

| || |

|||

|} |

|||

:Syllabic nasals: {{IPA|[m̩]}} {{IPA|[ŋ̩]}} |

|||

:¹Finals {{IPA|[ɛːu]}}, {{IPA|[ɛːm]}} and {{IPA|[ɛːp]}} only appear in colloquial speech. They are absent from some analyses and romanization schemes. |

|||

Officially Standard Mandarin ''(Putonghua'' or ''guoyu)'' is the standard language of mainland China and Taiwan and is taught nearly universally as a supplement to local languages such as Cantonese in Guangdong. Standard Cantonese and Standard Mandarin are the ''de facto'' official languages of Hong Kong and Macau, though legally the official language is "Chinese". Cantonese is also one of the main languages in many overseas Chinese communities including Australia, Southeast Asia, North America, and Europe. Many of these emigrants and/or their ancestors originated from Guangdong. In addition, these immigrant communities formed before the widespread use of Mandarin, or they are from Hong Kong where Mandarin is not commonly used. The [[prestige dialect]] of Cantonese is the Guangzhou / Cantonese dialect. In Hong Kong, colloquial Cantonese often incorporates English words due to historical British influences. |

|||

[[Image:Cantonese vowel chart.png|frame|right|[[IPA vowel chart|Chart of vowels]] used in Cantonese]] |

|||

In some ways, Cantonese is a more conservative language than Mandarin, and in other ways it is not. For example, Cantonese has retained consonant endings from older varieties of Chinese that have been lost in Mandarin, but it has merged some vowels from older varieties of Chinese. |

|||

Based on the chart above, the following central vowels pairs are usually considered to be [[allophones]]: |

|||

:{{IPA|[ɛː]}} - {{IPA|[e]}}, {{IPA|[iː]}} - {{IPA|[ɪ]}}, {{IPA|[ɔː]}} - {{IPA|[o]}}, {{IPA|[uː]}} - {{IPA|[ʊ]}}, and {{IPA|[œː]}} - {{IPA|[ɵ]}}. |

|||

Although that satisfies the [[minimal pair]] requirement, some linguists find it difficult to explain why the coda affects the vowel length. They recognize the following two allophone groups instead: |

|||

:{{IPA|[e]}} - {{IPA|[ɪ]}} and {{IPA|[o]}} - {{IPA|[ʊ]}} - {{IPA|[ɵ]}}. |

|||

In that way, the phoneme set consists of seven long central vowels and three short central vowels that are in contrast with three of the long vowels, as presented in the following chart: |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" |

|||

| |

|||

|colspan=2|{{IPA|aː}} |

|||

|colspan=2|{{IPA|ɔː}} |

|||

|colspan=2|{{IPA|ɛː}} |

|||

|{{IPA|iː}} |

|||

|{{IPA|uː}} |

|||

|{{IPA|œː}} |

|||

|{{IPA|yː}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| |

|||

|Long||Short |

|||

|Long||Short |

|||

|Long||Short |

|||

|Long |

|||

|Long |

|||

|Long |

|||

|Long |

|||

|- |

|||

|- |

|||

| -{{IPA|i}} / -{{IPA|y}} |

|||

|{{IPA|aːi}}||{{IPA|ɐi}} |

|||

|{{IPA|ɔːi}}||{{IPA|ɵy}} |

|||

| ||{{IPA|ei}} |

|||

| |

|||

|{{IPA|uːi}} |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

| -{{IPA|u}} |

|||

|{{IPA|aːu}}||{{IPA|ɐu}} |

|||

| ||{{IPA|ou}} |

|||

| || |

|||

|{{IPA|iːu}} |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

| -{{IPA|m}} |

|||

|{{IPA|aːm}}||{{IPA|ɐm}} |

|||

| || |

|||

| || |

|||

|{{IPA|iːm}} |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

| -{{IPA|n}} |

|||

|{{IPA|aːn}}||{{IPA|ɐn}} |

|||

|{{IPA|ɔːn}}||{{IPA|ɵn}} |

|||

| || |

|||

|{{IPA|iːn}} |

|||

|{{IPA|uːn}} |

|||

| |

|||

|{{IPA|yːn}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| -{{IPA|ŋ}} |

|||

|{{IPA|aːŋ}}||{{IPA|ɐŋ}} |

|||

|{{IPA|ɔːŋ}}||{{IPA|ʊŋ}} |

|||

|{{IPA|ɛːŋ}}||{{IPA|ɪŋ}} |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

|{{IPA|œːŋ}} |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

| -{{IPA|p}} |

|||

|{{IPA|aːp}}||{{IPA|ɐp}} |

|||

| || |

|||

| || |

|||

|{{IPA|iːp}} |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

| -{{IPA|t}} |

|||

|{{IPA|aːt}}||{{IPA|ɐt}} |

|||

|{{IPA|ɔːt}}||{{IPA|ɵt}} |

|||

| || |

|||

|{{IPA|iːt}} |

|||

|{{IPA|uːt}} |

|||

| |

|||

|{{IPA|yːt}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| -{{IPA|k}} |

|||

|{{IPA|aːk}}||{{IPA|ɐk}} |

|||

|{{IPA|ɔːk}}||{{IPA|ʊk}} |

|||

|{{IPA|ɛːk}}||{{IPA|ɪk}} |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

|{{IPA|œːk}} |

|||

| |

|||

|} |

|||

:Syllabic nasals: {{IPA|[m̩]}} {{IPA|[ŋ̩]}} |

|||

The [[Taishan dialect]], which in the U.S. nowadays is heard mostly spoken by Chinese actors in old American TV shows and movies (e.g. [[Hop Sing]] on [[Bonanza]]), is more conservative than Cantonese. It has preserved the initial /n/ sound of words, whereas many post-World War II-born Hong Kong Cantonese speakers have changed this to an /l/ sound ("ngàuh lām" instead of "ngàuh nām" for "beef brisket" {{lang|zh-yue-Hani|牛腩}}) and more recently drop the "ng-" initial (so that it changes further to "àuh lām"); this seems to have arisen from some kind of street affectation as opposed to systematic phonological change. The common word for "who" in Taishan is "sŭe" ({{lang|zh-yue-Hant|誰}}), which is the same character used in classical Chinese, whereas Cantonese has changed it to "bīngo" ({{lang|zh-yue-Hant|邊個}}). |

|||

===Tones=== |

|||

Hong Kong Cantonese has six [[tone (linguistics)|tones]], although it is often said to have nine. In Chinese, the number of possible tones depends on the [[syllable]] type. There are six [[tone contour|contour tones]] in Cantonese syllables that end in a vowel or [[nasal consonant]]. (Some of things have more than one realization, but such differences are seldom used to distinguish words.) In syllables that end in a [[stop consonant]], the number of tones is reduced to three; in Chinese descriptions, these "[[entering tone]]s" are treated separately, so that Cantonese is traditionally said to have nine tones. However, phonetically these are a conflation of tone and syllable type; the number of phonemic tones is six. |

|||

Cantonese sounds quite different from Mandarin, mainly because it has a different set of syllables. The rules for syllable formation are different; for example, there are syllables ending in non-nasal consonants (e.g. "lak"). It also has different tones and more of them than Mandarin. Cantonese is generally considered to have 8 tones, the choice depending on whether a traditional distinction between a high-level and a high-falling tone is observed; the two tones in question have largely merged into a single, high-level tone, especially in Hong Kong Cantonese, which has tended to simplify traditional Chinese tones.{{Fact|date=April 2007}} Many (especially older) descriptions of the Cantonese sound system record a higher number of tones, 9. However, the extra tones differ only in that they end in p, t, or k; otherwise they can be modeled identically.<ref>{{cite conference |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" |

|||

| last=Tan Lee |

|||

!Syllable type!!colspan=6|Open syllables!!colspan=3|Stopped syllables |

|||

| coauthors = Kochanski, G; Shih, C; Li, Yujia |

|||

|- |

|||

| authorlink=http://www.ee.cuhk.edu.hk/~tanlee/ |

|||

![[Tone name]] |

|||

| title=Modeling Tones in Continuous Cantonese Speech |

|||

|Upper Level<br>(陰平)||Upper Rising<br>(陰上)||Upper Departing<br>(陰去) |

|||

| booktitle=Proceedings of |

|||

|Lower Level<br>(陽平)||Lower Rising<br>(陽上)||Lower Departing<br>(陽去) |

|||

ICSLP2002 (Seventh International Conference on Spoken Language Processing) |

|||

|Upper Entering #1<br>(上陰入)||Upper Entering #2<br>(下陰入)||Lower Entering<br>(陽入) |

|||

| location=Denver, Colorado |

|||

|- |

|||

| date=16-20 September 2002 |

|||

! Pinyin [[tone number]] |

|||

| url=http://citeseer.ist.psu.edu/lee02modeling.html |

|||

|1||2||3 |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-08-20 |

|||

|4||5||6 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

|7 (or 1)||8 (or 3)||9 (or 6) |

|||

|- |

|||

! Examples |

|||

|詩||史||試 |

|||

|時||市||是 |

|||

|識||錫||食 |

|||

|- |

|||

! [[Tone contour|Tone letters]] |

|||

| {{IPA|si˥}}, {{IPA|si˥˧}} || {{IPA|si˧˥}} || {{IPA|si˧}} |

|||

| {{IPA|si˨˩}}, {{IPA|si˩}} || {{IPA|si˩˧}} || {{IPA|si˨}} |

|||

| {{IPA|sik˥}} || {{IPA|sik˧}} || {{IPA|sik˨}} |

|||

|- |

|||

! Tone diacritics |

|||

| {{IPA|sí}}, {{IPA|sî}} || {{IPA|sǐ}} || {{IPA|sī}} |

|||

| {{IPA|si̖}}, {{IPA|sı̏ }} || {{IPA|si̗}} || {{IPA|sì}} |

|||

| {{IPA|sík}} || {{IPA|sīk}} || {{IPA|sìk}} |

|||

|- |

|||

! Description |

|||

|high level,<br>high falling||medium rising||medium level |

|||

|low falling,<br>very low level||low rising||low level |

|||

|high level||medium level||low level |

|||

|- |

|||

! [[Yale Romanization]] |

|||

|sī, sì||sí||si |

|||

|sīh, sìh||síh||sih |

|||

|sīk||sik||sihk |

|||

|} |

|||

Cantonese preserves many syllable-final sounds that Mandarin has lost or merged. For example, the characters [[wikt:裔|裔]], [[wikt:屹|屹]], [[wikt:藝|藝]], [[wikt:艾|艾]], [[wikt:憶|憶]], [[wikt:譯|譯]], [[wikt:懿|懿]], [[wikt:誼|誼]], [[wikt:肄|肄]], [[wikt:翳|翳]], [[wikt:邑|邑]], and [[wikt:佚|佚]] are all pronounced "yì" in Mandarin, but they are all different in Cantonese (jeoih, ngaht, ngaih, ngaaih, yìk, yihk, yi, yìh, si, ai, yap, and yaht, respectively). Like [[Hakka Chinese|Hakka]] and [[Min Nan]], Cantonese has preserved the final consonants [-m, -n, -ŋ -p, -t, -k] from [[Middle Chinese]], while the Mandarin final consonants have been reduced to [-n, -ŋ]. But unlike any other modern Chinese dialects, the final consonants of Cantonese match those of Middle Chinese with very few exceptions. For example, lacking the syllable-final sound "m"; the final "m" and final "n" from older varieties of Chinese have merged into "n" in Mandarin, e.g. Cantonese "taahm" (譚) and "tàahn" (壇) versus Mandarin tán; "yìhm" (鹽) and "yìhn" (言) versus Mandarin yán; "tìm" (添) and "tìn" (天) versus Mandarin tiān; "hùhm" (含) and "hòhn" (寒) versus Mandarin hán. The examples are too numerous to list. Furthermore, nasals can be independent syllables in Cantonese words, e.g. Cantonese "ńgh" (五) "five," and "m̀h" (唔) "not". |

|||

For purposes of [[Chinese poetic meter|meters]] in [[Chinese poetry]], the first and fourth tones are the "level tones" (平聲), while the rest are the "oblique tones" (仄聲). |

|||

Differences also arise from Mandarin's relatively recent [[sound change]]s. One change, for example, palatalized {{IPA|[kʲ]}} with {{IPA|[tsʲ]}} to {{IPA|[tɕ]}}, and is reflected in historical Mandarin romanizations, such as ''Peking'' ([[Beijing]]), ''Kiangsi'' ([[Jiangxi]]), and Fukien ([[Fujian]]). This distinction is still preserved in Cantonese. For example, 晶, 精, 經 and 京 are all pronounced as "jīng" in Mandarin, but in Cantonese, the first pair is pronounced "jīng", and the second pair "gīng". |

|||

The first tone can be either high level or high falling without affecting the meaning of the words being spoken. Most speakers are in general not consciously aware of when they use and when to use high level and high falling. In Hong Kong, the high level is more usual. In Guangzhou, the high falling tone is more usual. |

|||

A more drastic example, displaying both the loss of coda plosives and the palatization of onset consonants, is the character ([[wikt:學|學]]), pronounced ''{{IPA|*ɣæwk}}'' in Middle Chinese. Its modern pronunciations in Cantonese, Hakka, Hokkien, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese are "hohk", "hók" ([[pinjim]]), "{{IPA|ha̍k}}" ([[Pe̍h-ōe-jī]]), học (although a Sino-Vietnamese word, it is used in daily vocabulary), "학" (hak) ([[Sino-Korean vocabulary|Sino-Korean]]), and "gaku" ([[Sino-Japanese vocabulary|Sino-Japanese]]), respectively, while the pronunciation in Mandarin is xué [{{IPA|ɕyɛ}}]. |

|||

The numbers "394052786" when pronounced in Cantonese, will give the nine tones in order (Romanisation ([[Yale Romanization|Yale]]) saam1, gau2, sei3, ling4, ng5, yi6, chat7, baat8, luk9), thus giving a good [[mnemonic]] for remembering the nine tones. |

|||

However, the Mandarin [[vowel]] system is somewhat more conservative than that of Cantonese, in that many [[diphthong]]s preserved in Mandarin have merged or been lost in Cantonese. Also, Mandarin makes a three-way distinction among [[alveolar]], [[alveopalatal]], and [[retroflex]] [[fricative]]s, distinctions that are not made by modern Cantonese. For example, ''jiang'' (將) and ''zhang'' (張) are two distinct syllables in Mandarin or old Cantonese, but in modern Cantonese they have the same sound, "jeung1". The loss of distinction between the alveolar and the alveolopalatal sibilants in Cantonese occurred in the mid-19th centuries and was documented in many Cantonese dictionaries and pronunciation guides published prior to the 1950s. ''A Tonic Dictionary of the Chinese Language in the Canton Dialect'' by Williams (1856), writes: ''The initials "ch" and "ts" are constantly confounded, and some persons are absolutely unable to detect the difference, more frequently calling the words under "ts" as "ch", than contrariwise.'' ''A Pocket Dictionary of Cantonese'' by Cowles (1914) adds: ''"s" initial may be heard for "sh" initial and vice versa.'' |

|||

It is interesting to note that there are not actually more tone ''levels'' in Cantonese than in Standard Mandarin (three if one excludes the Cantonese low falling tone, which begins on the third level and needs somewhere to fall), only Cantonese has a more complete set of tone courses. |

|||

There are clear [[sound correspondence]]s in, for instance, the tones. For example, a fourth-tone (low falling tone) word in Cantonese is usually second tone (rising tone) in Mandarin. |

|||

Cantonese preserves the distinction in [[Middle Chinese]] in the manner shown in the chart below. |

|||

This can be partly explained by their common descent from Middle Chinese (spoken), still with its different dialects. One way of counting tones gives Cantonese nine tones, Mandarin four, and Middle Chinese eight. Within this system, Mandarin merged the so-called "yin" and "yang" tones except for the Ping (平, flat) category, while Cantonese not only preserved these, but split one of them into two over time. Also, within this system, Cantonese is the only Chinese language known to have split its tones rather than merge them since the time of Late Middle Chinese. |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center; margin:1em auto 1em auto" |

|||

|colspan=2| Middle Chinese |

|||

|colspan=4|Cantonese |

|||

|- |

|||

|Tone||Initial |

|||

|Central Vowel||Tone Name||Tone Contour||Tone Number |

|||

|- |

|||

|rowspan=2|Level||V− |

|||

|rowspan=6| ||Upper Level||{{IPA|˥, ˥˧}}||1 |

|||

|- |

|||

|V+ |

|||

|Lower Level||{{IPA|˨˩, ˩}}||4 |

|||

|- |

|||

|rowspan=2|Rising||V− |

|||

|Upper Rising||{{IPA|˧˥}}||2 |

|||

|- |

|||

|V+ |

|||

|Lower Rising||{{IPA|˩˧}}||5 |

|||

|- |

|||

|rowspan=2|Departing||V− |

|||

|Upper Departing||{{IPA|˧}}||3 |

|||

|- |

|||

|V+ |

|||

|Lower Departing||{{IPA|˨}}||6 |

|||

|- |

|||

|rowspan=3|Entering||rowspan=2|V− |

|||

|Short||Upper Entering #1||{{IPA|˥ʔ}}||7 (1) |

|||

|- |

|||

|Long||Upper Entering #2||{{IPA|˧ʔ}}||8 (3) |

|||

|- |

|||

|V+ |

|||

| ||Lower Entering||{{IPA|˨ʔ}}||9 (6) |

|||

|} |

|||

==Relation to Classical Chinese== |

|||

V− = voiceless initial consonant, V+ = voiced initial consonant. The distinction of consonants found in Middle Chinese was preserved by the distinction of tones in Cantonese. The vowel length further affects the Upper Entering tone. |

|||

Since the pronunciation of all modern varieties of Chinese are different from Old Chinese or other forms of historical Chinese (such as Middle Chinese), characters that once rhymed in poetry may no longer (e.g. rhyming occurring sometimes in Min, Cantonese, and rarely in Mandarin, or vice versa). Poetry and other rhyme-based writing thus becomes less coherent than the original reading must have been. However, some modern Chinese dialects have certain phonological characteristics that are closer to the older pronunciations than others, as shown by the preservation of certain rhyme structures. Some believe wenyan literature, especially poetry, sounds better when read in certain dialects believed to be closer to older pronunciations, such as Cantonese or Southern Min. |

|||

==Cantonese outside China== |

|||

Cantonese is special in the way that the vowel length can affect both the rhyme and the tone. Some linguists believe that the vowel length feature may have roots in [[Old Chinese]] language. |

|||

Historically, the majority of the overseas Chinese have originated from just two provinces; [[Fujian]] and [[Guangdong]]. This has resulted in the overseas Chinese having a far higher proportion of Fujian and Guangdong languages/dialect speakers than Chinese speakers in China as a whole. More recent emigration from Fujian and Hong Kong have continued this trend. |

|||

The largest number of Cantonese speakers outside mainland China and Hong Kong are in south east Asia, however speakers of [[Min]] dialects are predominate among the overseas Chinese in south east Asia.{{Fact|date=September 2008}} The Cantonese spoken in Singapore and Malaysia is also known to have borrowed substantially from Malay and other languages |

|||

===Phonological shifts=== |

|||

Like other languages, Cantonese is constantly undergoing [[sound change]]s, processes where more and more native speakers of a language change the pronunciations of certain sounds. |

|||

=== |

===United Kingdom=== |

||

The majority of Cantonese speakers in the [[UK]] have origins from the former British colony of Hong Kong and speak the Canton/Hong Kong dialect, although many are in fact from [[Hakka]]-speaking families and are bilingual in Hakka. There are also Cantonese speakers from south east Asian countries such as [[Malaysia]] and [[Singapore]], as well as from Guangdong in China itself. Today an estimated 300,000 British people have Cantonese as a mother tongue/first language.<ref>[http://www.ethnologue.com/show_country.asp?name=GB Cantonese speakers in the UK]</ref> |

|||

One shift that affected Cantonese in the past was the loss of distinction between the alveolar and the alveolo-palatal (sometimes pronounced as postalveolar) sibilants, which occurred during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This distinction was documented in many Cantonese dictionaries and pronunciation guides published prior to the 1950s but is no longer distinguished in any modern Cantonese dictionary. |

|||

===United States of America=== |

|||

Publications that documented this distinction include: |

|||

For the last 150 years, [[Guangdong]] Province has been the place of origin of most Chinese emigrants to western countries; one coastal county, [[Taishan]] (or Tóisàn, where the Sìyì or ''sei yap'' dialect of Cantonese is spoken), alone may have been the home to more than 60% of Chinese immigrants to the US before 1965. As a result, Guangdong dialects such as ''sei yap'' (the dialects of Taishan, [[Enping]], [[Kaiping]] and [[Xinhui]] counties) and what is now called mainstream Cantonese (with a heavy Hong Kong influence) have been the major Cantonese dialects spoken abroad, particularly in the USA. |

|||

* Williams, S., ''A Tonic Dictionary of the Chinese Language in the Canton Dialect'', 1856. |

|||

* Cowles, R., ''A Pocket Dictionary of Cantonese'', 1914. |

|||

* [[Meyer-Wempe|Meyer, B. and Wempe, T.]], ''The Student's Cantonese-English Dictionary'', 3rd edition, 1947. |

|||

* [[Yuen Ren Chao|Chao, Y.]] ''Cantonese Primer'', 1947. |

|||

The [[Taishan dialect]], one of the ''sei yap'' or ''siyi'' ({{lang|zh-yue-Hani|四邑}}) dialects that come from Guangdong counties that were the origin of the majority of [[Chinese Exclusion Act (United States)|Exclusion-era]] Guangdong Chinese emigrants to the USA, continues to be spoken both by recent immigrants from Taishan and even by third-generation Chinese Americans of Taishan ancestry alike. |

|||

The depalatalization of sibilants caused many words that were once distinct to sound the same. For comparison, this distinction is still made in modern Standard Mandarin, with the old alveolo-palatal sibilants in Cantonese corresponding to the [[retroflex consonant|retroflex]] sibilants in Mandarin. For instance: |

|||

{|class="wikitable" |

|||

!Sibilant Category |

|||

!Character |

|||

!Modern Cantonese |

|||

!Old Cantonese |

|||

!Standard Mandarin |

|||

|- |

|||

|rowspan=2|Unaspirated affricate |

|||

|align=center|[[wiktionary:將|將]] |

|||

|rowspan=2|{{IPA|/tsœːŋ/}} (alveolar) |

|||

|{{IPA|/tsœːŋ/}} (alveolar) |

|||

|{{IPA|/tɕiɑŋ/}} (alveolo-palatal) |

|||

|- |

|||

|align=center|[[wiktionary:張|張]] |

|||

|{{IPA|/tɕœːŋ/}} (alveolo-palatal) |

|||

|{{IPA|/tʂɑŋ/}} (retroflex) |

|||

|- |

|||

|rowspan=2|Aspirated affricate |

|||

|align=center|[[wiktionary:槍|槍]] |

|||

|rowspan=2|{{IPA|/tsʰœːŋ/}} (alveolar) |

|||

|{{IPA|/tsʰœːŋ/}} (alveolar) |

|||

|{{IPA|/tɕʰiɑŋ/}} (alveolo-palatal) |

|||

|- |

|||

|align=center|[[wiktionary:昌|昌]] |

|||

|{{IPA|/tɕʰœːŋ/}} (alveolo-palatal) |

|||

|{{IPA|/tʂʰɑŋ/}} (retroflex) |

|||

|- |

|||

|rowspan=2|Fricative |

|||

|align=center|[[wiktionary:相|相]] |

|||

|rowspan=2|{{IPA|/sœːŋ/}} (alveolar) |

|||

|{{IPA|/sœːŋ/}} (alveolar) |

|||

|{{IPA|/ɕiɑŋ/}} (alveolo-palatal) |

|||

|- |

|||

|align=center|[[wiktionary:傷|傷]] |

|||

|{{IPA|/ɕœːŋ/}} (alveolo-palatal) |

|||

|{{IPA|/ʂɑŋ/}} (retroflex) |

|||

|} |

|||

The dialect of Zhongshan in Pearl River Delta is spoken by many Chinese immigrants in Hawaii, and some in San Francisco and in the Sacramento River Delta (see [[Locke, California]]); it is much closer to Canton dialect than Taishanese, but has "flatter" tones in pronunciation than Cantonese. Cantonese is the third most widely spoken non-English language in the United States.<ref name="Lai">{{cite book | last = Lai | first = H. Mark | title = Becoming Chinese American: A History of Communities and Institutions | publisher = AltaMira Press | date = 2004 | isbn = 0759104581}} '''need page number(s)'''</ref> The currently most popular romanization for learning Cantonese in the United States is [[Yale Romanization]]. |

|||

Even though the aforementioned references observed the distinction, most of them also noted that the depalatalization phenomenon was already occurring at the time. Williams (1856) writes: |

|||

The dialectal situation is now changing in the United States; recent Chinese emigrants originate from many different areas including mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Southeast Asia. Recent immigrants from mainland China and Taiwan in the U.S. all speak [[Standard Mandarin]] (''putonghua/guoyu''){{Fact|date=October 2008}} with varying degrees of fluency, and their native local language/dialect, such as Min ([[Hokkien]] and other [[Fujian]] dialects), [[Wu Chinese|Wu]], [[Mandarin Chinese|Mandarin]], Cantonese etc. As a result Standard Mandarin is increasingly becoming more common as the Chinese lingua franca among overseas Chinese. |

|||

==History== |

|||

{{quote|The initials ''ch'' and ''ts'' are constantly confounded, and some persons are absolutely unable to detect the difference, more frequently calling the words under ''ts'' as ''ch'', than contrariwise.}} |

|||

===Qin and Han=== |

|||

In ancient [[China]], Guangdong was called [[Nanyue]], and very few [[Han (people)|Han]] people lived there. Therefore, the [[Chinese language]] was not widely spoken there at that time. However, in the [[Qin]] Dynasty Chinese troops moved south and conquered the [[Baiyue]] territories, and thousands of Han people began settling in the [[Lingnan]] area. This migration led to the Chinese language being spoken in the [[Lingnan]] area. After [[Zhao Tuo|Zhào Tuó]] was made the Duke of [[Nanyue]] by the [[Han Dynasty]] and given authority over the Nanyue region, many Han people entered the area and lived together with the Nanyue population, consequently affecting the livelihood of the Nanyue people as well as stimulating the spread of the [[Chinese language]]. Although Han Chinese settlements and their influences soon dominated, some indigenous Nanyue population did not escape from the region. Today, the degree of interaction between Han Chinese and the indigenous population remains a highly controversial topic due to the lack of historical records and the hostility between modern Chinese and [[Vietnamese people|Vietnamese]]. |

|||

===Sui=== |

|||

Cowles (1914) adds: |

|||

In the [[Sui Dynasty]], [[Northern China|Zhongyuan]] was in a period of war and discontent, and many people moved southwards to avoid war, forming the first mass [[Human migration|migration]] of [[Han (people)|Han]] people into the South. As the population in the [[Lingnan]] area dramatically rose, the Chinese language in the south developed significantly. Thus, the Cantonese language began to develop more significant differences with central Chinese. |

|||

===Tang=== |

|||

{{quote|"s" initial may be heard for "sh" initial and vice versa.}} |

|||

As the Han population in the [[Guangdong]] area continued to rise during the [[Tang Dynasty]], some indigenous people living in the south had been culturally assimilated by the Han population, while others moved to other regions (such as Guangxi), developing their own dialects. At the time, Cantonese was affected by central Chinese and became more standardized, but it further developed a more independent language structure, vocabulary, and grammar. |

|||

===Song, Yuan, Ming and Qing=== |

|||

A vestige of this palatalization difference is sometimes reflected in the [[Hong Kong Government Cantonese Romanisation|romanization scheme used to romanize Cantonese names in Hong Kong]]. For instance, many names will be spelled with ''sh'' even though the "''sh'' sound" ({{IPA|/ɕ/}}) is no longer used to pronounce the word. Examples include the surname [[wiktionary:石|石]] ({{IPA|/sɛːk˨/}}), which is often romanized as ''Shek'', and the names of places like [[Sha Tin]] (沙田; {{IPA|/saː˥ tʰiːn˩/}}). |

|||

In the [[Song Dynasty]], the differences between central Chinese and Cantonese became more significant, and the languages became more independent of one another. During the [[Yuan Dynasty|Yuan]] and [[Ming Dynasty|Ming]] dynasties, Cantonese evolved still further, developing its own characteristics. |

|||

===Mid to Late Qing=== |

|||

After the shift was complete, even though the alveolo-palatal sibilants were no longer distinguished, they still continue to occur in [[complementary distribution]] with the alveolar sibilants, making the two groups of sibilants [[allophones]]. Thus, most modern Cantonese speakers will pronounce the alveolar sibilants unless the following vowel is {{IPA|/iː/}}, {{IPA|/i/}}, or {{IPA|/y/}}, in which case the alveolo-palatal (or postalveolar) is pronounced. [[Guangdong Romanization#Cantonese|Canton romanization]] attempts to reflect this phenomenon in its romanization scheme, even though most current Cantonese romanization schemes don't. |

|||

In the late [[Qing Dynasty|Qing]], the dynasty had gone through a period of [[sea|maritime]] ban under the [[Hai jin]]. Guangzhou remained one of the only cities that allowed trading with foreign countries, since the trade chamber of commerce was established there.<ref>Maritime Silk road. 海上丝绸之路 英 |

|||

ISBN 7508509323</ref> Therefore, some foreigners learned Cantonese and some Imperial government officials spoke Cantonese, making the language very popular in Cantonese-speaking Guangzhou. Also, the European control of Macau and Hong Kong had increased the exposure of Cantonese to the world. |

|||

=== 20th century === |

|||

The alveolo-palatal sibilants occur in complementary distribution with the retroflex sibilants in Mandarin as well, with the alveolo-palatal sibilants only occurring before {{IPA|/i/}}, or {{IPA|/y/}}. However, Mandarin also retains the [[medial (linguistics)|medial]]s, where {{IPA|/i/}} and {{IPA|/y/}} can occur, as can be seen in the examples above. Cantonese had lost its medials sometime ago in its history, reducing the ability for speakers to distinguish its sibilant initials. |

|||

In the Cantonese speaking region of mainland China, Mandarin is used for official purposes while Cantonese is used more informal situations. |

|||

In Hong Kong, [[Hong Kong Cantonese]] is the main and dominant form of spoken Chinese and is used in education, the government, public life, the media and entertainment (e.g. Hong Kong cinema), and in business dealings with Cantonese-speaking overseas Chinese communities. |

|||

====Current shifts==== |

|||

{{main|Hong Kong Cantonese}} |

|||

In modern-day Hong Kong, many younger native speakers are unable to distinguish between certain phoneme pairs and merge one sound into another. Although that is often considered as substandard and is denounced as being "lazy sounds" (懶音), it is becoming more common and is influencing other Cantonese-speaking regions. |

|||

Nowadays, due to ''Putonghua'' (Mandarin) being the medium of education on the mainland, many youngsters in the Cantonese speaking region in mainland China do not know specific historical and scientific vocabularies in Cantonese but do know social, cultural, entertainment, commercial, trading, and all other vocabularies{{Fact|date=September 2008}}. Cantonese is widely spoken and learned by overseas Chinese of Guangdong and Hong Kong origin. |

|||

==Romanization== |

|||

{{convertipa}} |

|||

There are several major [[romanization]] schemes for Cantonese: [[Barnett-Chao]], [[Meyer-Wempe]], the Chinese government's [[Guangdong romanization]], [[Yale Romanization#Cantonese|Yale]] and [[Jyutping|Jyutping (read: Yutping)]]. While they do not differ greatly, Yale is the one most commonly seen in the west today. The Hong Kong linguist [[Sidney Lau]] modified the Yale system for his popular Cantonese-as-a-second-language course, so that is another system used today by contemporary Cantonese learners. |

|||

The popularity of Cantonese-language media and entertainment from Hong Kong has led to a wide and frequent exposure of Cantonese to large portions of China and the rest of Asia. [[Cantopop]] and the Hong Kong film industry are prominent examples of modern Cantonese language media. |

|||

===Early Western effort=== |

|||

Systematic efforts to develop an alphabetic representation of Cantonese pronunciation began with the arrival of Protestant missionaries in China early in the nineteenth century. Romanization was considered both a tool to help new missionaries learn the dialect more easily and a quick route for the unlettered to achieve gospel literacy. Earlier Catholic missionaries, mostly Portuguese, had developed romanization schemes for the pronunciation current in the court and capitol city of China but made few efforts at romanizing other dialects. |

|||

== See also == |

|||

[[Robert Morrison (missionary)|Robert Morrison]], the first [[Protestant]] missionary in China published a "Vocabulary of the Canton Dialect" (1828) with a rather unsystematic romanized pronunciation. [[Elijah Coleman Bridgman]] and [[Samuel Wells Williams]] in their "Chinese Chrestomathy in the Canton Dialect" (1841) were the progenitors of a long-lived lineage of related romanizations with minor variations embodied in the works of [[James Dyer Ball]], [[Ernest John Eitel]], and [[Immanuel Gottlieb Genăhr]] (1910). Bridgman and Williams based their system on the phonetic alphabet and diacritics proposed by [[William Jones (philologist)|Sir William Jones]] for South Asian languages. Their romanization system embodied the phonological system in a local dialect rhyme dictionary, the Fenyun cuoyao, which was widely used and easily available at the time and is still available today. Samuel Wells Willams' ''Tonic Dictionary of the Chinese Language in the Canton Dialect'' (Yinghua fenyun cuoyao 1856), is an alphabetic rearrangement, translation and annotation of the Fenyun. In order to adapt the system to the needs of users at a time when there were only local variants and no standard—although the speech of the western suburbs, ''xiguan,'' of Guangzhou was the prestige variety at the time—Williams suggested that users learn and follow their teacher's pronunciation of his chart of Cantonese syllables. It was apparently Bridgman's innovation to mark the tones with an open circles (upper register tones) or an underlined open circle (lower register tones) at the four corners of the romanized word in analogy with the traditional Chinese system of marking the tone of a character with a circle (lower left for "even," upper left for "rising," upper right for "going," and lower right for "entering" tones). [[John Chalmers (missionary)|John Chalmers]], in his "English and Cantonese pocket-dictionary" (1859) simplified the marking of tones using the acute accent to mark "rising" tones and the grave to mark "going" tones and no diacritic for "even" tones and marking upper register tones by italics (or underlining in handwritten work). "Entering" tones could be distinguished by their consonantal ending. [[Nicholas Belfeld Dennys]] used Chalmers romanization in his primer. This method of marking tones was adopted in the Yale romanization (with low register tones marked with an 'h'). A new romanization was developed in the first decade of the twentieth century which eliminated the diacritics on vowels by distinguishing vowel quality by spelling differences (e.g. a/aa, o/oh). Diacritics were used only for marking tones. The name of Tipson is associated with this new romanization which still embodied the phonology of the Fenyun to some extent. It is the system used in Meyer-Wempe and Cowles' dictionaries and O'Melia's textbook and many other works in the first half of the twentieth century. It was the standard romanization until the Yale system supplanted it. The distinguished linguist, Y. R. Chao developed a Cantonese adaptation of his Gwoyeu romanization system which he used in his "Cantonese Primer." The front matter to this book contains a review and comparison of a number of the systems mentioned in this paragraph. The GR system was not widely used. |

|||

* [[Canton dialect|Cantonese]] |

|||

* [[Hong Kong Government Cantonese Romanisation]] |

|||

* [[Standard Cantonese Pinyin]] |

|||

* [[Jyutping|Jyutping (LSHK)]] |

|||

* [[Yale Romanization#Cantonese]] |

|||

* [[Written Cantonese]] |

|||

* [[Cantonese grammar]] |

|||

* [[Chinese written language]] |

|||

* [[Chinese input methods for computers]] |

|||

==References== |

|||

===Cantonese research in Hong Kong=== |

|||

{{reflist}} |

|||

{{main|Hong Kong Government Cantonese Romanisation}} |

|||

An influential work on Cantonese, [[A Chinese Syllabary Pronounced According to the Dialect of Canton]], written by [[Wong Shik Ling]], was published in 1941. He derived an [[IPA]]-based transcription system for Cantonese, [[S. L. Wong (phonetic symbols)|S. L. Wong system]], with many Chinese dictionaries published later in Hong Kong being based on this transcription system. Although Wong also derived a romanisation scheme, also known as [[S. L. Wong (romanisation)|S. L. Wong system]], it is not widely used as his transcription scheme. |

|||

== External links == |

|||

The one advocated by the [[Linguistic Society of Hong Kong]] (LSHK) is called [[jyutping]], which solves many of the inconsistencies and problems of the older, favored, and more familiar system of Yale Romanization, but departs considerably from it in a number of ways unfamiliar to Yale users. The phonetic values of letters are not quite familiar to whom had studied English. Some effort has been undertaken to promote jyutping, with some official supports, but it is too early to tell how successful it is. |

|||

{{interwiki|code=zh-yue}} |

|||

{{Wikibookspar|Cantonese|Cantonese}} |

|||

=== Dictionaries === |

|||

Another popular scheme is [[Standard Cantonese Pinyin]] Schemes, which is the only romanization system accepted by [[Hong Kong Education and Manpower Bureau]] and [[Hong Kong Examinations and Assessment Authority]]. Books and studies for teachers and students in primary and secondary schools usually use this scheme. But there is quite a lot teachers and students using the transcription system of S. L. Wong. |

|||

==== Cantonese dictionaries or databases with spoken Cantonese entries ==== |

|||

* [http://win2003.chi.cuhk.edu.hk/hanyu/ 香港中文大學-現代標準漢語與粵語對照資料庫 (Chinese University of Hong Kong - Standard Mandarin and Cantonese control database): A comparative database and dictionary of Modern Chinese and Cantonese]: This is one of the few online sites with an extensive database of ''spoken Cantonese terms and phrases'' on the Internet. A rare and precious resource (exclusively in Chinese). |

|||

* [http://www.cantonese.sheik.co.uk/dictionary/ The CantoDict Project] is a free, online Cantonese (characters, jyutping, and some pinyin; definition in English) dictionary updated frequently by volunteers from around the world. As well as tens of thousands of words, many of its example sentences may be listened to in MP3 format. |

|||

* [http://www.cantonese.jp/pages/dic_.htm Cantonese-Japanese Dictionary]: This is an online Cantonese-Japanese dictionary aimed mainly at Japanese speakers. The corresponding [http://www.cantonese.jp/pages/dic.htm Japanese-Cantonese dictionary] is also on this site. |

|||

==== Character-only Cantonese pronunciation dictionaries ==== |

|||

However, learners may feel frustrated that most native Cantonese speakers, no matter how educated they are, really are not familiar with any romanization system. Apparently, there is no motive for local people to learn any of these systems. The romanization systems are not included in the education system either in Hong Kong or in Guangdong province. In practice, Hong Kong people follow a loose unnamed romanisation scheme used by the [[Hong Kong Government]]. |

|||

* [http://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-can/ The Chinese University of Hong Kong Research Centre for Humanities Computing: ''Chinese Character Database: With Word-formations Phonologically Disambiguated According to the Cantonese Dialect'':] A vast Chinese character database of over 13,000 characters with audio pronunciations in Cantonese. This site is viewable in Chinese and English. You can choose from seven transcription schemes to view character pronunciations. By default, the site is displayed in Chinese and uses the LSHK jyutping transcription scheme. To view the site in English and/or use a different transcription scheme, a cookies enabled browser is required. For each character you can find Cantonese pronunciations, Mandarin pronunciations, character ranking/frequency, [[Big5]] encoding number, [[Unicode]] number, [[cangjie]] (chongkit) input code, and which radical the character can be found under using a traditional Chinese dictionary. |

|||

* [http://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/Canton2/ Cantonese Talking Syllabary:] in Chinese; require Big5 font |

|||

* [http://www.chineselanguage.org/CCDICT/index.html Chinese Character Dictionary] |

|||

* [http://www.mdbg.net/chindict/chindict.php MDBG free online Chinese-English dictionary:] An online Chinese English dictionary supporting both Cantonese and Mandarin. (''You need to click the compound word to get the individual Cantonese readings of each character; no direct Cantonese phrase pronunciation guide at the moment.'') Standard Chinese words only. Vernacular Cantonese not supported |

|||

=== Other links === |

|||

==Written Cantonese== |

|||

*[http://home.comcast.net/~jbmbweb/cantoinput/index.html CantoInput] Free tool that converts Cantonese Yale Romanization into characters. Note that tone markings/numbers are not used, but rather there is a menu of characters. |

|||

{{main|Written Cantonese}} |

|||

*[http://www.omniglot.com/writing/cantonese.htm Omniglot]Character comparisons between colloquial Cantonese characters and Standard Chinese characters. |

|||

*[http://www.mandarintools.com/chardict.html Dictionary with Yale Romanization] Cantonese dictionary using Yale Romanization with numbers. |

|||

Cantonese is usually referred to as a spoken dialect, and not as a written dialect. Spoken vernacular Cantonese differs from modern written Chinese, which is essentially formal Standard Mandarin in written form. Written Chinese spoken word for word sounds overly formal and distant in Cantonese. As a result, the necessity of having a written script which matched the spoken form increased over time. This resulted in the creation of additional Chinese characters to complement the existing characters. Many of these represent phonological sounds not present in Mandarin. A good source for well documented Cantonese words can be found in drama and [[Cantonese opera|opera (大戲 daai hei)]] scripts. Written Cantonese is largely incomprehensible to non-Cantonese speakers because written Cantonese is based on spoken Cantonese which is different from Standard Mandarin in grammar and vocabulary. |

|||

*[http://www.cantonese.sheik.co.uk/scripts/wordsearch.php Dictionary with Jyutping] Cantonese dictionary using Jyutping romanization |

|||

*[http://www.cantonese-learner.com Cantonese-Learner] A site that can help cantonese learners improve. |

|||

"Readings in Cantonese colloquial: being selections from books in the Cantonese vernacular with free and literal translations of the Chinese character and romanized spelling" (1894) by James Dyer Ball has a bibliography of works available in Cantonese characters in the last decade of the nineteenth century. A few libraries have collections of so-called "wooden fish books" written in Cantonese character. Facsimiles and plot precis of a few of these have been published in Wolfram Eberhard's "Cantonese Ballads." See also "Cantonese love-songs, translated with introduction and notes by Cecil Clementi" (1904) or a newer translation of these Yue Ou in "Cantonese love songs : an English translation of Jiu Ji-yung's Cantonese songs of the early 19th century" (1992). Cantonese character versions of the Bible, Pilgrims Progress, and Peep of Day as well as simple catechisms were published by mission presses. The special Cantonese characters used in all these was not standardized and shows wide variation. |

|||

*[http://www.cantonese.sheik.co.uk Learn Cantonese:] an English site dedicated to publishing Cantonese learning resources and reference materials. |

|||

*[http://www.glossika.com/en/dict/classification/yue/index.php Classification of Cantonese Dialects] |

|||

With the advent of the computer and standardization of character sets specifically for Cantonese, many printed materials in predominantly Cantonese speaking areas of the world are written to cater to their population with these written Cantonese characters. As a result, mainstream media such as newspapers and magazines have become progressively less conservative and more colloquial in their dissemination of ideas. Generally speaking, some of the older generation of Cantonese speakers regard this trend as a step "backwards" and away from tradition. This tension between the "old" and "new" is a reflection of a transition that is being undergone by the Cantonese-speaking population. |

|||

*[http://toshuo.com/cantonese-tone-tool/ Cantonese Tone Tool] Add tone marks to romanized Cantonese |

|||

*[http://www.info.gov.hk/digital21/eng/hkscs/ Hong Kong Government site on the HK Supplementary Character Set (HKSCS)] |

|||

[[Vernacular Chinese|Standard written Chinese]] is, in essence, written Standard Mandarin. When standard written Chinese is read aloud with Cantonese sound values, the result sounds stilted and unnatural because it is different from normal spoken Cantonese. Written Cantonese is spoken Cantonese written as it is actually spoken. Unusual for a regional (i.e., non-Mandarin) Chinese language, Cantonese has a written form, developed over the last few decades in Hong Kong, and includes many unique characters that are not found in standard written Chinese. Readers who understand standard written Chinese but do not know Cantonese often find written Cantonese hard to understand or even unintelligible as it is different from standard written Chinese in grammar and vocabulary. However, written Cantonese is commonly used informally among Cantonese speakers. Circumstances where written Cantonese is used include conversations through [[instant messaging]] services, letters, notes, entertainment magazines and entertainment sections of newspapers, and sometimes [[Subtitle (captioning)|subtitle]]s in [[Hong Kong movies]], and [[advertisement]]s. It rarely finds its way into the subtitles of Western movies or TV shows, though [[The Simpsons]] is a notable exception. [[Cantonese Opera]] scripts also use the Cantonese written vernacular. |

|||

*[http://www.cantoneseonline.org Official Website for Free Cantonese Classes in New York City] |

|||

*[http://cantonese.hku.hk/traditional/6th_Yue_Conf_contents.html 第六屆國際粵方言研討會論文集] (Sixth International Cantonese Language Research Conference) |

|||

Historically, written Cantonese has been used in Hong Kong for legal proceedings in order to write down the exact spoken testimony of a witness, instead of paraphrasing spoken Cantonese into standard written Chinese. Newspapers have also done likewise to capture more exact quotes. Its popularity and usage has been rising in the last two decades, the late Wong Jim being one of the pioneers of its use as an effective written language. Written colloquial Cantonese has become quite popular in certain tabloids, online chat rooms, and instant messaging. Some tabloids like Apple Daily write colloquial Cantonese; papers may contain editorials that contain Cantonese; and Cantonese-specific characters can be increasingly seen on advertisements and billboards. Written Cantonese remains limited outside of Hong Kong, even in other Cantonese-speaking areas such as Guangdong, where the use of colloquial writing is discouraged. Despite the relative popularity of written Cantonese in Hong Kong, some disdain it, believing that being too accustomed to write in such a way would affect a person's ability to use standard written Chinese in situations that demand it. |

|||

*{{lang|zh-yue-Hant|[http://cantonese.hku.hk/traditional/right324.html 八十年代以後的粵方言研究]}} (Post-1980s Cantonese Language Research) |

|||

Forms of written Chinese in Hong Kong: |

|||

# Standard Written Chinese (traditional characters) used in Hong Kong SAR post-WWII [[Vernacular Reformation]]. |

|||

# [[Vernacular Chinese|pakwa]] {{lang|zh-cn|日常白話}} Colloquial Written Cantonese - currently used in journals, advertisements, etc. in Hong Kong SAR, overseas Cantonese Chinese communities. |

|||

# Classical Cantonese Chinese - a reconstructed Neo-Classical written Chinese forms widely used in 1900s-90s Hong Kong in Cantonese opera lyrics, Cantonese Chinese poetic forms and especially in 80s [[cantopop]]. |

|||

# Classical Chinese known as [[Classical Chinese|wenyanwen]] - a written Chinese form in poems and writings from the dynastic periods. |

|||

For colloquial vernacular usage, written Cantonese incorporates an entire range of characters and particles specific to the Cantonese spoken form. This is commonly used in publicity and journalistic writing in Hong Kong and Hong Kong-influenced regions. It reads exactly as formal spoken Cantonese. |

|||

For literary and artistic reasons (such as calligraphy), standard literary Chinese, the classical wenyanwan is used. |

|||

Records of legal documents in Hong Kong also use written Cantonese sometimes, in order to record exactly what a witness has said. |

|||

Colloquial Cantonese is rarely used in formal forms of writing; formal written communication is almost always in standard written Chinese, albeit still pronounced with Cantonese sound values. However, written colloquial Cantonese does exist; it is used mostly for transcription of speech in tabloids, in some broadsheets, for some subtitles, for personal diaries, and in other informal forms of communication such as Internet bulletin boards (BBS) or e-mails. It is not uncommon to see the front page of a Cantonese paper written in [[hanyu]], while the entertainment sections are, at least partly, in Cantonese. The vernacular writing system has evolved over time from a process of modifying characters to express lexical and syntactic elements found in Cantonese but not the standard written language. In spite of their vernacular origin and informal use, these characters have become so common in Hong Kong that the [[Hong Kong]] Government has incorporated them into a special [[HKSCS|Hong Kong Supplementary Character Set]] (HKSCS), as the same as special characters used for [[proper noun]]s. |

|||

A problem for the student of Cantonese is the lack of a widely accepted, standardized transcription system. Another problem is with [[Chinese character]]s: Cantonese uses the same system of characters as standard written Chinese, but it often uses different words, which have to be written with different or new characters. An example of Cantonese using a different word and a different character to write it: the Mandarin word for "to be" is shì and is written as {{lang|zh-hk|[[:wikt:是|是]]}}, but in Cantonese the word for "to be" is hai6 and {{lang|zh-hk|係}} is used in written Cantonese ({{lang|zh-hk|[[:wikt:係|係]]}} is xì in Mandarin). In standard written Chinese {{lang|zh-hk|是}} is normally used, though {{lang|zh-hk|係}} can be found in classical literature and modern legal writing. In Hong Kong, {{lang|zh-hk|係}} is often used in colloquial written Cantonese and therefore actively avoided and discouraged in formal writing; on the other hand, the use of {{lang|zh-hk|係}} is relatively widespread in both [[mainland China]] and in [[Taiwan]], in government publications and product descriptions, for example. |

|||

Many characters used in colloquial Cantonese writings are made up by putting a mouth radical ({{lang|zh-hk|[[:wikt:口|口]]}}) on the left hand side of another more well known character to indicate that the character is read like the right hand side, but it is only used phonetically in the Cantonese context. The characters <ref>[http://www.unicode.org/cgi-bin/GetUnihanData.pl?codepoint=35CE Unicode.org]</ref>, {{lang|zh-hk|叻}}, {{lang|zh-hk|吓}}, {{lang|zh-hk|吔}}, {{lang|zh-hk|呃}}, {{lang|zh-hk|咁}}, {{lang|zh-hk|咗}}, {{lang|zh-hk|咩}}, {{lang|zh-hk|哂}}, {{lang|zh-hk|哋}}, {{lang|zh-hk|唔}}, {{lang|zh-hk|唥}}, {{lang|zh-hk|唧}}, {{lang|zh-hk|啱}}, {{lang|zh-hk|啲}}, {{lang|zh-hk|喐}}, {{lang|zh-hk|喥}}, {{lang|zh-hk|喺}}, {{lang|zh-hk|嗰}}, {{lang|zh-hk|嘅}}, {{lang|zh-hk|嘜}}, {{lang|zh-hk|嘞}}, {{lang|zh-hk|嘢}}, {{lang|zh-hk|嘥}}, {{lang|zh-hk|嚟}}, {{lang|zh-hk|嚡}}, {{lang|zh-hk|嚿}}, {{lang|zh-hk|囖}} etc. are commonly used in Cantonese writing. |

|||

As not all Cantonese words can be found in current encoding system, or the users simply do not know how to enter such characters on the computer, in very informal speech, Cantonese tends to use extremely simple romanization (e.g. use D as {{lang|zh-hk|啲}}), symbols (add an English letter "o" in front of another Chinese character; e.g. {{lang|zh-hk|㗎}} is defined in Unicode, but will not display in Microsoft Internet Explorer 6.0, hence the proxy {{lang|zh-hk|o架}} is often used), homophones (e.g. use {{lang|zh-hk|果}} as {{lang|zh-hk|嗰}}), and Chinese characters of different Mandarin meaning (e.g. {{lang|zh-hk|[[:wikt:乜|乜]]}}, {{lang|zh-hk|[[:wikt:係|係]]}}, {{lang|zh-hk|[[:wikt:俾|俾]]}} etc.) to compose a message. |

|||

For example, "{{lang|zh-hk|你喺嗰喥好喇,千祈咪搞佢啲嘢。}}" is often written in easier form as "{{lang|zh-hk|你o係果度好喇,千祈咪搞佢D野。}}" (character-by-character, approximately "you, be, there (two characters), good, (final particle), thousand, pray, don't, mess, he/she, genitive particle, thing"; translation: "It's okay that you're staying there, but please don't mess with his/her stuff"). |

|||

Other common characters are unique to Cantonese or deviated from their Standard Chinese usage; these include: {{lang|zh-hk|[[:wikt:乜|乜]]}}, {{lang|zh-hk|[[wikt:冇|冇]]}}, {{lang|zh-hk|[[:wikt:仔|仔]]}}, {{lang|zh-hk|[[:wikt:佢|佢]]}}, {{lang|zh-hk|[[wikt:佬|佬]]}}, {{lang|zh-hk|[[:wikt:係|係]]}}, {{lang|zh-hk|[[:wikt:俾|俾]]}}, {{lang|zh-hk|[[:wikt:靚|靚]]}} etc. |

|||

The words represented by these characters are sometimes [[cognate]]s with pre-existing Chinese words. However, their colloquial Cantonese pronunciations have diverged from formal Cantonese pronunciations. For example, in formal written Chinese, {{lang|zh-Hani|[[:wikt:無|無]]}} (mou4) is the character used for "without". In spoken Cantonese, {{lang|zh-yue-Hani|冇}} (mou5) has the same usage, meaning, and pronunciation as {{lang|zh-yue-Hani|無}}, differing only by tone. {{lang|zh-yue-Hani|冇}} is actually a hollowed out writing of its antonym ({{lang|zh-yue-Hani|[[:wikt:有|有]]}}). {{lang|zh-yue-Hani|冇}} represents the spoken Cantonese form of the word "without", while {{lang|zh-Hani|無}} represents the word used in formal Chinese writing (pinyin: wú) . However, {{lang|zh-Hani|無}} is still used in some instances in spoken Chinese in both dialects, like {{lang|zh-Hant|[[:wikt:無論|無論]]}} ("no matter what"). A Cantonese-specific example is the [[Doublet (linguistics)|doublet]] {{lang|zh-yue-Hani|[[:wikt:來|來]]/[[:wikt:嚟|嚟]]}}, which means "to come". {{lang|zh-yue-Hani|來}} (loi4) is used in formal writing; {{lang|zh-yue-Hani|嚟}} (lei4) is the spoken Cantonese form. |

|||

== Cultural role == |

|||

China has numerous regional and local varieties of spoken Chinese, many of which are mutually unintelligible; most of these are rarely used or heard outside their native areas, and are not used in education, formal purposes, or in the media. Regional/local dialects (including Cantonese) in mainland China and Taiwan tend to be used primarily within their local region with other native speakers, with Standard Mandarin being used for official purposes, in the media, and as the language of education. Even though the majority of Cantonese speakers live in mainland China, due to the linguistic history of [[Hong Kong]] and [[Macau]], as well as its use in many [[overseas Chinese]] communities, the use of Cantonese has spread from Guangdong far out of proportion to its relatively small number of speakers in China. |

|||

As the majority of Hong Kong and Macau people and/or their ancestors emigrated from Guangdong before the widespread use of Standard Mandarin, Cantonese became the usual and only spoken variety of Chinese in Hong Kong and Macau. Cantonese is the only Chinese variety to be used in official contexts other than Standard Mandarin, which is the official language of both the [[People's Republic of China]] and the [[Republic of China]]. Also because of its use by non-Mandarin speaking Cantonese speakers overseas, Cantonese is one of the primary forms of Chinese that many Westerners come into contact with. |

|||

Along with Mandarin and [[Taiwanese (linguistics)|Taiwanese]], Cantonese is also one of the few Chinese spoken varieties which has its own popular music ([[Cantopop]]). The prevalence of Hong Kong's popular culture has spurred some Chinese in other regions to learn Cantonese{{Fact|date=March 2008}}. In Hong Kong, Cantonese is dominant in the domain of popular music, and many artists from Beijing and Taiwan have to learn Cantonese so that they can make Cantonese versions of their recordings especially for distribution in Hong Kong.<ref name="Donald">Donald, Stephanie. Keane, Michael. Hong, Yin. [2002] (2002). Media in China: Consumption, Content and Crisis. Routledge Mass media policy. ISBN 0700716149. pg 113</ref> Some singers including [[Faye Wong]] and [[Eric Moo]], and singers from Taiwan, have been trained in Cantonese to add "Hong Kong-ness" to their performances<ref name="Donald" />. |

|||