m Robot - Speedily moving category Scenic highways in New Mexico to Category:New Mexico Scenic and Historic Byways per CFDS. |

ILoveCaracas (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

==History== |

==History== |

||

[[File:Plaza de la Constitucion Ciudad de Mexico City.jpg|thumb|left|250px|[[Mexico City]].]] |

|||

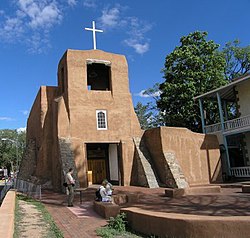

[[File:Santa Fe church.jpg|thumb|left|250px|The Spanish Mission of San Miguel in [[Santa Fe, New Mexico]], possibly the oldest church in the United States of America.]] |

|||

Before the arrival of the Spaniards, nomadic tribes lived by hunting and fishing. Then agriculture took root. Over time, "great civilizations" emerged and flourished. And long before the Europeans arrived, they already had established the trade network that would later become the '''Camino Real de Tierra Adentro'''. In those years, trade connected the peoples of the [[valley of Mexico]] with those of the north through the exchange of products such as [[turquoise]], [[obsidian]], [[salt]] and [[feather]]s, so that by the year 1000, trade spread from [[Mesoamerica]] to [[Rocky Mountains]].<ref>[http://www.colpos.mx/asyd/volumen8/numero2/res-11-001.pdf http://www.colpos.mx/asyd/volumen8/numero2/res-11-001.pdf]<br /> |

|||

</ref> |

|||

Once the great [[Tenochtitlan]] was subdued, the [[conquistador]]s began a series of expeditions with the purpose of expanding their domains and obtaining greater wealth for the [[Spanish Crown]]. At first they followed the trails with the "fragile footprints" of the natives who exchanged goods between the north and the south. |

|||

Researchers [[Enrique Lamadrid]], [[Jack Loeffer]] and [[Tomás Saldaña]] tell the story of the Camino Real as the oldest in North America: |

|||

{{Quote|"The royal roads were the main transport routes for communication, cultural change and commerce.) The viceroyal army, organized in light cavalry flying companies, protected travelers, livestock and merchandise"}} |

|||

In April 1598 -the investigators point out- "an advanced group of soldiers is lost in the desert south of [[Ciudad Juárez|Paso del Norte]], seeking the best route to the [[Rio Grande]]. A captive Indian named ''Mompil'' drew in the sand a map of the only safe passage, which would soon be part of the '''Camino Real de Tierra Adentro'''". It is in this year, when this group, mainly led by the [[Viceroyalty of New Spain|New-Spanish]] [[Juan de Oñate]],<ref name = ": 0">[http://www.educacion.gob.es/exterior/centros/albuquerque/es/newmexico/CaminoReal.pdf http://www.educacion.gob.es/exterior/centros/albuquerque/es/newmexico/CaminoReal.pdf]<br /> |

|||

</ref> consolidated and extended the journey to what is now [[Santa Fe, New Mexico|Santa Fe]], capital of the then province of [[New Mexico]], at that time, part of the [[New Spain]]. |

|||

It should be noted that there were four main roads, or main routes, of Camino Real, which linked [[Mexico City]] with [[Acapulco]], [[Veracruz (city)|Veracruz]], [[Real Audiencia of Guatemala|Audiencia]] ([[Guatemala]]) and Santa Fe: "They formed a quadruple route full of walkers, carts and mule trains". From these is derived the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, which was the one that went to the north. |

|||

The '''Camino Real de Tierra Adentro''' followed a path marked by the terrain: "The volcanic activity and an inclement climate worked a land rich in deposits of [[silver]], [[copper]], [[gold], [[opal]]s, turquoises and salt. The displacements of the [[tectonic plates]] opened in the center of [[New Mexico]] a crack more than a kilometer and a half deep, the second longest in the world. The melting waters that flowed into the valley formed the Rio Grande and it filled the deep gap with sediment". |

|||

Initially when the Spanish Crown decided not to abandon the province of New Mexico, ruinous in all respects, but to maintain it so as not to leave the Indigenous already Christianized, the [[Viceroyalty of New Spain]] organized a system to supply the [[Christian mission|missions]], [[presidio]]s and nortern ranchos. It is in the so-called ''conducta'', that they decide to organize themselves in wagon caravans that depart every three years from Mexico City to the border. It began a long and difficult journey of six months, including 2–3 weeks of rest throughout the trip. Many were the uncertainties that travelers faced. The floods of the rivers could force weeks of waiting on the banks until they could wade through. At the other extreme appeared prolonged droughts, which made men and animals suffer. The most feared was the crossing of the so-called ''Jornada del Muerto'', beyond El Paso del Norte: a hundred kilometers without water to stock up. The greatest danger was that of assaults. There were specialized bands that from the current states of Mexico to the state of [[Querétaro]] lurked the caravan (full of valuable articles). And, above all, from the southern [[Zacatecas]], the greatest threat was the attacks of Natives [[Chichimeca]]s, more frequent as it progressed towards the north. Their main objective was horses, sometimes even women and children. The troops of the presidios made relays to endow the convoy of additional protection, and when the caravan entered the most committed areas, to spend the night the cars formed a circle with the people and animals inside. |

|||

[[File:Puente del Camino Real de Tierra Adentro de Ojuelos.JPG|thumb|264px|Bridge of [[Ojuelos de Jalisco|Ojuelos]] in the state of [[Jalisco]], part of the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, declared [[World Heritage Site]] by [[UNESCO]] along with 59 other sites on the route.]] |

|||

[[File:SanFranTercerOrdenSombrerete02.JPG|thumb|264px|Plaza de San Francisco square where you can see the [[Templo de la Tercera Orden]], and the [[Templo y Convento de San Francisco]], whose construction began in 1567; in the city of [[Sombrerete, Zacatecas|Sombrerete]], [[Zacatecas]]. You can see the Spanish influence mixed with local elements, such as the management of the pink quarry or the [[Tlaxcaltec]] elements at the entrance of the temple.]] |

|||

[[File:Hacienda de San Blas del Pabellón de Hidalgo, Aguascalientes.JPG|thumb|264px|[[Hacienda de San Blas]], in the town of [[Pabellón de Hidalgo]], it is a 16th century [[hacienda]], now made a Museum of the Insurgency. It is a good example of the agricultural haciendas that fed the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro.]] |

|||

The route was actively used as a commercial route for 300 years, from the middle of [[16th century]] to [[19th century]], mainly for the transport of silver extracted from mines. For this reason, the road was improving, and over time the risks became smaller as hospitals and haciendas emerged. |

|||

During the 18th century the sites along the Camino Real increased significantly. The ''villa of San Felipe el Real'' (today [[Chihuahua City|city of Chihuahua]]) surrounded by its mines became a commercial center and important financial area between [[Durango City|Durango]] and Santa Fe, this area would be called "the Chihuahua Trail". The ''villa of San Felipe Neri de Alburquerque'' was in turn founded in 1706 (today [[Albuquerque, New Mexico]], the "r" is lost in the 19th century) and soon it became an important terminal along the "Chihuahua Trail". The ''Villa de Alburquerque'' was very important because of its defensive position on the Camino Real which gave it the chance to grow as a center of commercial exchange during the 18th century. The state of New Mexico traded mainly with cattle, wool, textiles, animal skins, salt, and nuts. This exchange occurred mainly with the mining cities of Chihuahua, [[Santa Bárbara, Chihuahua|Santa Bárbara]] and [[Parral, Chihuahua|Parral]]. For the year of 1765 the population of the Paso del Norte was 2,635 inhabitants, which created that it was the largest urban center on the northern border of New Spain. ''El Paso'' became an important center of agriculture and rancheria and was known for its [[Mexican wine|wines]], [[brandy]], vinegar and raisins. |

|||

In the 18th century the Spanish Crown authorized the celebration of the [[fair]]s, however they existed since the beginning of [[Spanish Empire|the Colony]]. Some of the most important fairs along the Camino Real included the ''Fair of [[San Juan de los Lagos]] in [[Jalisco]], the ''Fair of [[Saltillo]]'', and the ''Fair of Chihuahua'', which was of great importance to New Mexico merchants. The ''Fair of the town of [[Taos, New Mexico|Taos]]'' was also an important annual event where the [[comanche]]s and the [[Ute people|utes]] exchanged weapons, ammunition, horses, agricultural products, furs, and meats with the [[New Spain|New-Spanish]]. Spain at the same time maintained a monopoly with the products of its northern provinces, thus it was not allowed to trade with the [[French colonization of the Americas|French colony]] in [[Louisiana]]. |

|||

For the second half of the 18th century, the northern frontier of New Spain represented a fundamental interest for the [[Spanish Empire]] and its reformist policy, with the aim of ensuring Spanish sovereignty over such important territories, highly coveted geopolitically by other European powers:<ref name = ": 1">[http://www.saber.ula.ve/bitstream/123456789/28985/1/articulo1.pdf http://www.saber.ula.ve/bitstream/123456789/28985/1/articulo1.pdf]<br /> |

|||

</ref> a conciliatory policy was pertinent, above all because of the dangerous presence in the area of [[English]] and [[French]], and a reconsideration of the role assigned to the Natives, since not only was it wanted not to hostile the Spaniards, become and be linked to economic processes, but also participate in the defense of the border.<ref name = ": 1" /> |

|||

Thus, the captain [[Nicolás de Lafora]] (assigned by the then [[Marquisate of Rubí|marquis of Rubí]]) gives a description of the frontier of New Spain in his "''Viaje a los presidios internos de la América septentrional"'' and that is the product of the expedition that took place between 1766 and 1768. This expedition was only part of a larger commission on the defensive issues and military reorganization entrusted by the Spanish Empire to the Marquis of Rubí, to find out the bad tactical placement of the presidios, inspected the troops, recognized the regulations and proposed what was convenient for a better government and defensive state. The Marquis of Rubí thus militarily inspected the prisons in the internal provinces and proposed a line of presidios in the New Spain border in 1766 which was raised from the Gulf of Mexico to protect itself from the utes, [[apache]]s, comanches, and [[navajo]]s.<ref>[http://cachanilla69.blogspot.mx/2013/08/linea-de-presidios-de-la-frontera.html http://cachanilla69.blogspot.mx/2013/08/linea-de-presidios-de-la-frontera.html]</ref> Don [[José de Gálvez]], special commissioner to New Spain for [[Charles III of Spain|Charles III]], promoted a "''Comandancia General de las Provincias Internas''" to the northern New Spain and recognized that a long war with the natives would be impossible due to lack of resources. On the contrary, he himself incited the establishment of peace and a greater commercial increase in 1779. In 1786 the nephew of José de Gálvez, [[Bernardo de Gálvez]], [[viceroy]] of New Spain published his ''"Instructions''" which included three strategies for deal with the Natives: continue the military pressure, the formation of alliances, and create a state of dependence on the part of the Natives, who had entered into peace treaties with the Spanish Crown. |

|||

During the last decade of 18th century peace was achieved between the Spaniards and the Apache tribes as a result of the aforementioned administrative and strategic changes. As a result, the commercial exchange of several products and of several regions of New Spain (land products), European products of the Spanish fleet and also those that came from the [[Manila galleon]] that arrived annually at Acapulco. As an example, for this time, the most typical products sold by the merchants of the city of Parral in the northern of the road, included: platoncillos of [[Michoacán]], jarrillos of [[Cuautitlán]] of the State of Mexico, majolica of the State of [[Puebla]], [[porcelain]] junks of [[China]], and mud products of [[Guadalajara]]. |

|||

The 19th century brought many changes for both Mexico and its northern border. In 1821 after 11 years of struggle, Mexico became independent from Spain. The Camino Real maintained an important role in this period, since the travelers maintained the communication about the events that took place in the center of the country in the towns and villages in the internal provinces. During the [[Mexican War of Independence|Independence]] the Camino Real was used by both forces, rebels and royal forces. An example of this is that after the rebellion started by the liberator [[Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla]], he used the road to go to the city of Chihuahua where he was captured and executed |

|||

[[File:Cuatillosdog.JPG|thumb|291px|left|[[Templo de Nuestra Señora del Refugio]] located in Hacienda La Pedriceña, in the now community of Los Cuatillos, in the municipality of [[Cuencamé Municipality|Cuencamé]], [[Durango]]. In this hacienda you can find [[New Spanish Baroque|Baroque]] paintings, and multiple mansions that served to manage the property. The chapel of the hacienda was built in the 18th century. The "[[Cry of Dolores]]" that is celebrated every year in Mexico on September 15 to remember the call of Independence given by [[Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla|Miguel Hidalgo]], was organized from this hacienda by the president [[Benito Juárez]] in 1864.]] |

|||

During and after independence, the government was unstable and the struggle continued, the resources sent to the northern provinces were continuously reduced, which led to the creation of alternate routes. For 1807, American merchants and other border military like [[Zebulon Pike]] tried to find trails to give to New Mexico and Chihuahua. [[Zebulon Pike]] was captured on February 26, 1807 by the Spanish authorities in northern New Mexico, who sent him on the Camino Real to the city of Chihuahua. While Zebulon Pike was in this city, he had access to several maps of Mexico and learned of the discontent with Spanish domination. |

|||

Between 1821 and 1822, after the end of the war for the [[Mexican War of Independence|Independence of Mexico]], it begins to consolidate as a route the ''[[Santa Fe Trail]]'' that connected [[Missouri]] (US territory) and [[Santa Fe, New Mexico|Santa Fe]] (Mexican territory). At first, US merchants were imprisoned for infiltrating contraband into Mexican territory, however the economic crisis in northern Mexico, gave rise to more and more acceptance of this type of trade. In fact, the ''Santa Fe Trail'' (Sendero de Santa Fe) increased trade for local products (such as cotton) and manufactured products from New Mexico, so Mexicans in this area looked favorably on this new trade route, in turn that they did not stop visiting the cities of the south. For 1827, there was already a lucrative and commercial connection between Missouri, New Mexico and Chihuahua. |

|||

In 1846, the dispute over the Texas-Mexico border with the United States gave rise to the subsequent US invasion by US military forces and the [[Mexican–American War]] began. One of these forces was commanded by the general [[Stephen W. Kearny|Stephen Kearny]], who traveled by the ''Santa Fe Trail'' to seize the capital of New Mexico. Another of the forces commanded by Colonel [[Alexander William Doniphan]] defeated a small group of Mexican contingents on the Camino Real, in the Los Brazitos area the south of what is now [[Las Cruces, New Mexico|Las Cruces]], New Mexico which was described in the diary of [[Susan Shelby Magoffin]] the wife of a merchant. As a result, Doniphan's American forces captured El Paso del Norte and later the city of Chihuahua. During 1846 - 1847, the '''Camino Real de Tierra Adentro''' became a path of continuous use, with American forces using it to travel into the interior of [[Mexico]] . On their journey, many American travelers kept journals and wrote to their homes about what they saw as they left. One of the soldiers provided an estimate of the population of several cities along the Camino. These included, [[Algodones, New Mexico|Algodones]] with 1000 inhabitants, [[Bernalillo, New Mexico|Bernalillo]] with 500, [[Sandia Pueblo|Sandía Pueblo]] of 300 to 400, Albuquerque without an estimated number but extended by seven or eight miles along the [[Rio Grande]], rancho de los Placeres with 200 or 300, [[Tome, New Mexico|Tomé]] with 2,000, and [[Socorro, New Mexico|Socorro ]] was described as a "considerable city", Paso del Norte with 5,000 to 6,000, and the [[Carrizal, Chihuahua| Carrizal]] with 400 inhabitants. The soldiers even kept notes of the products, prices, and animals that were on their journeys. |

|||

In 1848 with the [[Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo]], the war was officially ended with the requisition that Mexico cede most of its northern territory including what are now the states of [[New Mexico]], [[Colorado]], [[Arizona]], and [[California]]. The Camino Real de Tierra Adentro was divided forever between two countries, and over time their stories lasted while many others were lost; however, its cultural legacy is still tangible in our days. |

|||

[[File:Placaloscuatillosunesco.JPG|thumb|left|Plaque commemorating inscrpition of the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro into the UNESCO World Heritage list.]] |

[[File:Placaloscuatillosunesco.JPG|thumb|left|Plaque commemorating inscrpition of the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro into the UNESCO World Heritage list.]] |

||

The trail was used for trade among native tribes since the earliest of times. In 1598, Oñate followed the trail while leading a group of settlers North during the era of Spanish conquest. The duration of the trip from the Rio Grande to the San Juan Pueblo was said to take, by wagon and by foot, approximately 6 months including 2–3 weeks of rest throughout the trip.<ref>need citation</ref> According to journals kept by settlers they used common animals found along the trail to add to the food they brought along. The trail greatly improved trade among Spanish villages and helped the Spanish conquistadors spread Christianity throughout the conquered lands. The trail was used from 1598 through 1881 when the railroad replaced the need for wagons. Eventually, railroads replaced rutted trails and over time the trail and evidence of it faded from sight and memory. The changes that the railways brought made trade along El Camino much easier and in some cases made travel quite luxurious and exciting. |

|||

==List of World Heritage locations== |

==List of World Heritage locations== |

||

Revision as of 03:42, 31 December 2017

| Camino Real de Tierra Adentro | |

|---|---|

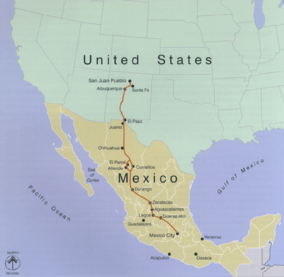

Map of El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro | |

| Location | Mexico and the United States |

| Governing body | Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (Mexico) National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management (United States) |

| Website | El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail |

The Camino Real de Tierra Adentro (Spanish for "Royal Road of the Interior Land") was a 2560 kilometer (1,600 mile) long trade route between Mexico City and San Juan Pueblo, New Mexico, from 1598 to 1882.[1]

In 2010, 55 sites and 5 existing World Heritage Sites along the Mexican section of the route became an entry on the Unesco World Heritage List.[2] Those sites include historic cities, towns, bridges, haciendas and other monuments along the 1,400km route between the Historic Center of Mexico City (independent World Heritage Site) and the town of Valle de Allende, Chihuahua.

The 404 mile (646 kilometer) section of the route within the United States was proclaimed as a part of the National Historic Trail system on October 13, 2000. El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail is overseen by both the National Park Service and the U.S. Bureau of Land Management with aid from El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro Trail Assoc. also known as CARTA. A portion of the trail near San Acacia, New Mexico was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2014.[3]

History

Before the arrival of the Spaniards, nomadic tribes lived by hunting and fishing. Then agriculture took root. Over time, "great civilizations" emerged and flourished. And long before the Europeans arrived, they already had established the trade network that would later become the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro. In those years, trade connected the peoples of the valley of Mexico with those of the north through the exchange of products such as turquoise, obsidian, salt and feathers, so that by the year 1000, trade spread from Mesoamerica to Rocky Mountains.[4]

Once the great Tenochtitlan was subdued, the conquistadors began a series of expeditions with the purpose of expanding their domains and obtaining greater wealth for the Spanish Crown. At first they followed the trails with the "fragile footprints" of the natives who exchanged goods between the north and the south.

Researchers Enrique Lamadrid, Jack Loeffer and Tomás Saldaña tell the story of the Camino Real as the oldest in North America:

"The royal roads were the main transport routes for communication, cultural change and commerce.) The viceroyal army, organized in light cavalry flying companies, protected travelers, livestock and merchandise"

In April 1598 -the investigators point out- "an advanced group of soldiers is lost in the desert south of Paso del Norte, seeking the best route to the Rio Grande. A captive Indian named Mompil drew in the sand a map of the only safe passage, which would soon be part of the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro". It is in this year, when this group, mainly led by the New-Spanish Juan de Oñate,[5] consolidated and extended the journey to what is now Santa Fe, capital of the then province of New Mexico, at that time, part of the New Spain.

It should be noted that there were four main roads, or main routes, of Camino Real, which linked Mexico City with Acapulco, Veracruz, Audiencia (Guatemala) and Santa Fe: "They formed a quadruple route full of walkers, carts and mule trains". From these is derived the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, which was the one that went to the north.

The Camino Real de Tierra Adentro followed a path marked by the terrain: "The volcanic activity and an inclement climate worked a land rich in deposits of silver, copper, [[gold], opals, turquoises and salt. The displacements of the tectonic plates opened in the center of New Mexico a crack more than a kilometer and a half deep, the second longest in the world. The melting waters that flowed into the valley formed the Rio Grande and it filled the deep gap with sediment".

Initially when the Spanish Crown decided not to abandon the province of New Mexico, ruinous in all respects, but to maintain it so as not to leave the Indigenous already Christianized, the Viceroyalty of New Spain organized a system to supply the missions, presidios and nortern ranchos. It is in the so-called conducta, that they decide to organize themselves in wagon caravans that depart every three years from Mexico City to the border. It began a long and difficult journey of six months, including 2–3 weeks of rest throughout the trip. Many were the uncertainties that travelers faced. The floods of the rivers could force weeks of waiting on the banks until they could wade through. At the other extreme appeared prolonged droughts, which made men and animals suffer. The most feared was the crossing of the so-called Jornada del Muerto, beyond El Paso del Norte: a hundred kilometers without water to stock up. The greatest danger was that of assaults. There were specialized bands that from the current states of Mexico to the state of Querétaro lurked the caravan (full of valuable articles). And, above all, from the southern Zacatecas, the greatest threat was the attacks of Natives Chichimecas, more frequent as it progressed towards the north. Their main objective was horses, sometimes even women and children. The troops of the presidios made relays to endow the convoy of additional protection, and when the caravan entered the most committed areas, to spend the night the cars formed a circle with the people and animals inside.

The route was actively used as a commercial route for 300 years, from the middle of 16th century to 19th century, mainly for the transport of silver extracted from mines. For this reason, the road was improving, and over time the risks became smaller as hospitals and haciendas emerged.

During the 18th century the sites along the Camino Real increased significantly. The villa of San Felipe el Real (today city of Chihuahua) surrounded by its mines became a commercial center and important financial area between Durango and Santa Fe, this area would be called "the Chihuahua Trail". The villa of San Felipe Neri de Alburquerque was in turn founded in 1706 (today Albuquerque, New Mexico, the "r" is lost in the 19th century) and soon it became an important terminal along the "Chihuahua Trail". The Villa de Alburquerque was very important because of its defensive position on the Camino Real which gave it the chance to grow as a center of commercial exchange during the 18th century. The state of New Mexico traded mainly with cattle, wool, textiles, animal skins, salt, and nuts. This exchange occurred mainly with the mining cities of Chihuahua, Santa Bárbara and Parral. For the year of 1765 the population of the Paso del Norte was 2,635 inhabitants, which created that it was the largest urban center on the northern border of New Spain. El Paso became an important center of agriculture and rancheria and was known for its wines, brandy, vinegar and raisins.

In the 18th century the Spanish Crown authorized the celebration of the fairs, however they existed since the beginning of the Colony. Some of the most important fairs along the Camino Real included the Fair of San Juan de los Lagos in Jalisco, the Fair of Saltillo, and the Fair of Chihuahua, which was of great importance to New Mexico merchants. The Fair of the town of Taos was also an important annual event where the comanches and the utes exchanged weapons, ammunition, horses, agricultural products, furs, and meats with the New-Spanish. Spain at the same time maintained a monopoly with the products of its northern provinces, thus it was not allowed to trade with the French colony in Louisiana.

For the second half of the 18th century, the northern frontier of New Spain represented a fundamental interest for the Spanish Empire and its reformist policy, with the aim of ensuring Spanish sovereignty over such important territories, highly coveted geopolitically by other European powers:[6] a conciliatory policy was pertinent, above all because of the dangerous presence in the area of English and French, and a reconsideration of the role assigned to the Natives, since not only was it wanted not to hostile the Spaniards, become and be linked to economic processes, but also participate in the defense of the border.[6]

Thus, the captain Nicolás de Lafora (assigned by the then marquis of Rubí) gives a description of the frontier of New Spain in his "Viaje a los presidios internos de la América septentrional" and that is the product of the expedition that took place between 1766 and 1768. This expedition was only part of a larger commission on the defensive issues and military reorganization entrusted by the Spanish Empire to the Marquis of Rubí, to find out the bad tactical placement of the presidios, inspected the troops, recognized the regulations and proposed what was convenient for a better government and defensive state. The Marquis of Rubí thus militarily inspected the prisons in the internal provinces and proposed a line of presidios in the New Spain border in 1766 which was raised from the Gulf of Mexico to protect itself from the utes, apaches, comanches, and navajos.[7] Don José de Gálvez, special commissioner to New Spain for Charles III, promoted a "Comandancia General de las Provincias Internas" to the northern New Spain and recognized that a long war with the natives would be impossible due to lack of resources. On the contrary, he himself incited the establishment of peace and a greater commercial increase in 1779. In 1786 the nephew of José de Gálvez, Bernardo de Gálvez, viceroy of New Spain published his "Instructions" which included three strategies for deal with the Natives: continue the military pressure, the formation of alliances, and create a state of dependence on the part of the Natives, who had entered into peace treaties with the Spanish Crown.

During the last decade of 18th century peace was achieved between the Spaniards and the Apache tribes as a result of the aforementioned administrative and strategic changes. As a result, the commercial exchange of several products and of several regions of New Spain (land products), European products of the Spanish fleet and also those that came from the Manila galleon that arrived annually at Acapulco. As an example, for this time, the most typical products sold by the merchants of the city of Parral in the northern of the road, included: platoncillos of Michoacán, jarrillos of Cuautitlán of the State of Mexico, majolica of the State of Puebla, porcelain junks of China, and mud products of Guadalajara.

The 19th century brought many changes for both Mexico and its northern border. In 1821 after 11 years of struggle, Mexico became independent from Spain. The Camino Real maintained an important role in this period, since the travelers maintained the communication about the events that took place in the center of the country in the towns and villages in the internal provinces. During the Independence the Camino Real was used by both forces, rebels and royal forces. An example of this is that after the rebellion started by the liberator Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, he used the road to go to the city of Chihuahua where he was captured and executed

During and after independence, the government was unstable and the struggle continued, the resources sent to the northern provinces were continuously reduced, which led to the creation of alternate routes. For 1807, American merchants and other border military like Zebulon Pike tried to find trails to give to New Mexico and Chihuahua. Zebulon Pike was captured on February 26, 1807 by the Spanish authorities in northern New Mexico, who sent him on the Camino Real to the city of Chihuahua. While Zebulon Pike was in this city, he had access to several maps of Mexico and learned of the discontent with Spanish domination.

Between 1821 and 1822, after the end of the war for the Independence of Mexico, it begins to consolidate as a route the Santa Fe Trail that connected Missouri (US territory) and Santa Fe (Mexican territory). At first, US merchants were imprisoned for infiltrating contraband into Mexican territory, however the economic crisis in northern Mexico, gave rise to more and more acceptance of this type of trade. In fact, the Santa Fe Trail (Sendero de Santa Fe) increased trade for local products (such as cotton) and manufactured products from New Mexico, so Mexicans in this area looked favorably on this new trade route, in turn that they did not stop visiting the cities of the south. For 1827, there was already a lucrative and commercial connection between Missouri, New Mexico and Chihuahua.

In 1846, the dispute over the Texas-Mexico border with the United States gave rise to the subsequent US invasion by US military forces and the Mexican–American War began. One of these forces was commanded by the general Stephen Kearny, who traveled by the Santa Fe Trail to seize the capital of New Mexico. Another of the forces commanded by Colonel Alexander William Doniphan defeated a small group of Mexican contingents on the Camino Real, in the Los Brazitos area the south of what is now Las Cruces, New Mexico which was described in the diary of Susan Shelby Magoffin the wife of a merchant. As a result, Doniphan's American forces captured El Paso del Norte and later the city of Chihuahua. During 1846 - 1847, the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro became a path of continuous use, with American forces using it to travel into the interior of Mexico . On their journey, many American travelers kept journals and wrote to their homes about what they saw as they left. One of the soldiers provided an estimate of the population of several cities along the Camino. These included, Algodones with 1000 inhabitants, Bernalillo with 500, Sandía Pueblo of 300 to 400, Albuquerque without an estimated number but extended by seven or eight miles along the Rio Grande, rancho de los Placeres with 200 or 300, Tomé with 2,000, and Socorro was described as a "considerable city", Paso del Norte with 5,000 to 6,000, and the Carrizal with 400 inhabitants. The soldiers even kept notes of the products, prices, and animals that were on their journeys.

In 1848 with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the war was officially ended with the requisition that Mexico cede most of its northern territory including what are now the states of New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, and California. The Camino Real de Tierra Adentro was divided forever between two countries, and over time their stories lasted while many others were lost; however, its cultural legacy is still tangible in our days.

List of World Heritage locations

The Camino Real de Tierra Adentro world heritage entry includes the following:[8]

United States Historic Trail

From the Texas-New Mexico border to San Juan Pueblo north of Española, a drivable route, mostly part of former U.S. Route 85, has been designated as a National Scenic Byway called El Camino Real.

Portions of the trade route corridor also contain pedestrian, bicycle, and equestrian trails. These include the existing Paseo del Bosque Trail in Albuquerque and portions of the proposed Rio Grande Trail. Its northern terminus, Santa Fe, is a terminus also of the Old Spanish Trail and the Santa Fe Trail.

Along the trail, parajes (stop overs) that have been preserved today include El Rancho de las Golondrinas.

Fort Craig and Fort Selden are also located along the trail.

CARTA

El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro Trail Association (CARTA) is a non-profit trail organization that aims to help promote, educate, and preserve the cultural and historic trail in collaboration with the National Park Service, the Bureau of Land Management, the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs and various Mexican organizations. CARTA publishes an informative journal, Chronicles of the Trail, quarterly that provides people with further history and current affairs of the trail and what CARTA, as an organization, is doing to help the trail.

Chihuahua Trail

The Chihuahua Trail describes this route as it passed from New Mexico through the state of Chihuahua to central Mexico.

In the late 16th century Spanish exploration and colonization had advanced from Mexico City northward by the great central plateau to its ultimate goal in Santa Fe. Until Mexican independence (1821) all communications of New Mexico with the outer world was restricted to this 1,500-mile (2,400 km) trail. Over it came ox carts and mule trains, missionaries and governors, soldiers and colonists. When the Santa Fe Trail sprang up, traders from the United States extended their operations southward over the Chihuahua Trail and beyond to Durango and Zacatecas. Superseded by railroads, the ancient Mexico City-Santa Fe road was revived as a great automobile highway of Mexico. The part in New Mexico, State Highway 85, pioneered by Franciscan missionaries in 1581, may be the oldest highway in the United States.

See also

- El Camino Real (California) – The California Mission Trail

- El Camino Real de Los Tejas – El Camino Real from Texas east to Louisiana

- Old San Antonio Road – A section of El Camino Real de Los Tejas

- Scenic byways in the United States

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Socorro County, New Mexico

References

- ^ Snyder, Rachel Louise. "Camino Real" American Heritage, April/May 2004.

- ^ "Camino Real de Tierra Adentro – World Heritage List". UNESCO. Retrieved 2010-08-05.

- ^ "Weekly list of actions 11/03/14 through 11/07/14". National Park Service. Retrieved 2014-11-23.

- ^ http://www.colpos.mx/asyd/volumen8/numero2/res-11-001.pdf

- ^ http://www.educacion.gob.es/exterior/centros/albuquerque/es/newmexico/CaminoReal.pdf

- ^ a b http://www.saber.ula.ve/bitstream/123456789/28985/1/articulo1.pdf

- ^ http://cachanilla69.blogspot.mx/2013/08/linea-de-presidios-de-la-frontera.html

- ^ "Camino Real de Tierra Adentro Map". whc.unesco.org.

Further reading

- Dictionary of American History by James Truslow Adams, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1940

- Boyle, Susan Calafate. Los Capitalistas: Hispano Merchants and the Santa Fe Trade. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1997.

- Moorhead, Max L. New Mexico’s Royal Road. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1958.

- Palmer, Gabrielle G., et al.. El Camino Real de Tierra Dentro. Santa Fe: Bureau of Land Management, 1993.

- Palmer, Gabrielle G. and Stephen L. Fosberg. El Camino Real de Tierra Dentro. Santa Fe: Bureau of Land Management, 1999.

- Preston, Douglas and José Antonio Esquibel. The Royal Road. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1998.

External links

- National Park Service: official El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail website

- El Camino Real International Heritage Center

- El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro – Integrated education curriculum

- CARTA – El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro Trail Association: website

- N.M.-Monuments.org – "A Road Over Time"