m Reverted edits by 213.106.96.131 to last version by JoanneB |

Smasongarrison (talk | contribs) m Moving from Category:Anti–Vietnam War activists to Category:British anti–Vietnam War activists Diffusing per WP:DIFFUSE and/or WP:ALLINCLUDED using Cat-a-lot |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|British philosopher and logician (1872–1970)}} |

|||

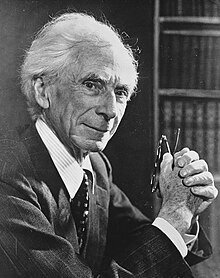

[[image:Russell2.jpg|thumb|240px|right|Bertrand Russell]] |

|||

{{Ref-cleanup|reason=Citation styles are inconsistent, a mix of CS1, plain text, and minimally-formatted links, sometimes with webarchive templates|date=September 2023}} |

|||

{{Use British English|date=November 2020}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=July 2023}} |

|||

{{Infobox philosopher |

|||

|honorific_prefix = [[The Right Honourable]] |

|||

|name = The Earl Russell |

|||

|honorific_suffix = {{post-nominals|country=GBR|OM|FRS|size=100%}} |

|||

|image = Bertrand Russell 1949.jpg |

|||

|caption = Russell in 1949 |

|||

|module = {{infobox officeholder |

|||

|embed = yes |

|||

|office = [[Member of the House of Lords]] |

|||

|status = [[Lords Temporal|Lord Temporal]] |

|||

|term_start = 4 March 1931 |

|||

|term_end = 2 February 1970<br />[[Hereditary peer]]age |

|||

|predecessor = [[Frank Russell, 2nd Earl Russell|The 2nd Earl Russell]] |

|||

|successor = [[John Russell, 4th Earl Russell|The 4th Earl Russell]] |

|||

|party = [[Labour Party (UK)|Labour]] (1922–1965) |

|||

|otherparty = [[Liberal Party (UK)|Liberal]] (1907–1922) |

|||

}} |

|||

|birth_name = Bertrand Arthur William Russell |

|||

|birth_date = {{birth date|df=yes|1872|5|18}} |

|||

|birth_place = [[Trellech]], [[Monmouthshire (historic)|Monmouthshire]], [[Wales]]{{efn|name=fn1}} |

|||

|death_date = {{Death date and age|df=yes|1970|2|2|1872|5|18}} |

|||

|death_place = [[Penrhyndeudraeth]], Merionethshire, Wales |

|||

|spouse = {{unbulleted list |{{marriage|[[Alys Pearsall Smith]]|1894|1921|end=div}} |{{marriage|[[Dora Russell|Dora Black]]|1921|1935|end=div}} |{{marriage |[[Patricia Russell|Patricia Spence]] |1936 |1952 |end=div}}<ref>{{Cite book |last=Irvine |first=Andrew David |chapter-url=https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2015/entries/russell |chapter=Bertrand Russell |title=[[Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy]] |date=1 January 2015 |publisher=Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University |editor-last=Zalta |editor-first=Edward N.}}</ref> |{{marriage|[[Edith Finch Russell|Edith Finch]]|1952}}}} |

|||

|education = [[Trinity College, Cambridge]] ([[Bachelor of Arts|BA]], 1893) |

|||

|awards = {{unbulleted list |class=nowrap |[[De Morgan Medal]] (1932) |[[Sylvester Medal]] (1934) |[[Nobel Prize in Literature]] (1950) |[[Kalinga Prize]] (1957) |[[Jerusalem Prize]] (1963)}} |

|||

|era = [[20th-century philosophy]] |

|||

|region = [[Western philosophy]] |

|||

|school_tradition = [[Analytic philosophy]] |

|||

|institutions = [[Trinity College, Cambridge]], [[London School of Economics]], [[University of Chicago]], [[University of California, Los Angeles]] |

|||

|main_interests = {{flatlist| |

|||

* [[Epistemology]] |

|||

* ethics |

|||

* [[logic]] |

|||

* mathematics |

|||

* [[metaphysics]] |

|||

* [[philosophy]] |

|||

}} |

|||

|notable_ideas = {{collapsible list |

|||

|[[Analytic philosophy]] |

|||

|[[Automated reasoning]] |

|||

|[[Automated theorem proving]] |

|||

|[[Axiom of reducibility]] |

|||

|[[Barber paradox]] |

|||

|[[Berry paradox]] |

|||

|[[Chicken (game)|Chicken]] |

|||

|[[Connective (logic)|Connective]] |

|||

|Criticism of the [[coherence theory of truth]] |

|||

|Criticism of the [[doctrine of internal relations]]/[[logical holism]] |

|||

|[[Definite description]] |

|||

|[[Descriptivist theory of names]] |

|||

|[[Direct reference theory]]<ref>Wettstein, Howard, "[[Frege–Russell view|Frege-Russell Semantics?]]", ''Dialectica'' '''44'''(1–2), 1990, pp. 113–135, esp. 115: "Russell maintains that when one is acquainted with something, say, a present sense datum or oneself, one can refer to it without the mediation of anything like a Fregean sense. One can refer to it, as we might say, ''directly''."</ref> |

|||

|[[Double negation]] |

|||

|[[Epistemic structural realism]]<ref>[http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/structural-realism/#Rel "Structural Realism"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080703161848/http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/structural-realism/#Rel |date=3 July 2008 }}: entry by James Ladyman in the ''[[Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy]]''</ref> |

|||

|[[Existential fallacy]] |

|||

|[[Failure of reference]] |

|||

|[[Knowledge by acquaintance]] and [[knowledge by description]] |

|||

|[[Logical atomism]] ([[atomic proposition]]) |

|||

|[[Logical form]] |

|||

|[[Mathematical beauty]] |

|||

|[[Mathematical logic]] |

|||

|[[Meaning (philosophy of language)|Meaning]] |

|||

|[[Metamathematics]] |

|||

|[[Philosophical logic]] |

|||

|[[Predicativism]] |

|||

|[[Propositional analysis]] |

|||

|[[Propositional calculus]] |

|||

|[[Naive set theory]] |

|||

|[[Neutral monism]]<ref>{{Cite book |chapter-url=https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/russellian-monism |chapter=Russellian Monism |title=[[Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy]]|year=2019 |publisher=Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University }}</ref> |

|||

|[[Paradoxes of set theory]] |

|||

|[[Peano–Russell notation]] |

|||

|[[Propositional formula]] |

|||

|[[Self-refuting idea]] |

|||

|[[Quantification (logic)|Quantification]] |

|||

|[[Russell–Myhill paradox]] |

|||

|[[Russell's conjugation]] |

|||

|[[Russell-style universes]] |

|||

|[[Russell's paradox]] |

|||

|[[Russell's teapot]] |

|||

|Russell's theory of causal lines<ref>{{Cite book |last=Dowe |first=Phil |chapter-url=https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/causation-process |chapter=Causal Processes |title=[[Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy]] |date=10 September 2007 |publisher=Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University |editor-last=Zalta |editor-first=Edward N. }}</ref> |

|||

|[[Russellian change]] |

|||

|[[Russellian propositions]] |

|||

|[[Round square copula|Russellian view]] (Russell's critique of [[Alexius Meinong|Meinong's]] [[Abstract object theory|theory of objects]]) |

|||

|[[Set-theoretic definition of natural numbers]] |

|||

|[[Singleton (mathematics)|Singleton]] |

|||

|[[Theory of descriptions]] |

|||

|[[Relation (philosophy)|Theory of relations]] |

|||

|[[Type theory]]/[[ramified type theory]] |

|||

|[[Tensor product of graphs]] |

|||

|[[Unity of the proposition]] |

|||

|title={{nbsp}} |

|||

}} |

|||

|academic_advisors=[[James Ward (psychologist)|James Ward]]<ref>[https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/james-ward/ James Ward] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200501112521/https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/james-ward/ |date=1 May 2020 }} ([[Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy]])</ref><br />[[A. N. Whitehead]] |

|||

|doctoral_students=[[Ludwig Wittgenstein]] |

|||

|notable_students=[[Raphael Demos]] |

|||

|signature=Bertrand Russell signature.svg |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell''', {{postnominals|country=GBR|sep=,|OM|FRS}}<ref name="frs">{{Cite journal |last=Kreisel |first=G. |author-link=Georg Kreisel |year=1973 |title=Bertrand Arthur William Russell, Earl Russell. 1872–1970 |journal=[[Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society]] |volume=19 |pages=583–620 |doi=10.1098/rsbm.1973.0021 |jstor=769574 |doi-access=free}}</ref> (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, logician, philosopher, and [[public intellectual]]. He had influence on mathematics, [[logic]], [[set theory]], and various areas of [[analytic philosophy]].<ref name="stanford">Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, [http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/russell/ "Bertrand Russell"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070609090837/http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/russell/ |date=9 June 2007 }}, 1 May 2003.</ref> |

|||

[[The Right Honourable]] '''Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell''', [[Order of Merit|OM]], [[Fellow of the Royal Society|FRS]] ([[18 May]] [[1872]]—[[2 February]] [[1970]]), was an influential British [[mathematical logic|logician]], [[philosopher]], and [[mathematician]], working mostly in the [[20th century]]. A prolific [[writer]], Bertrand Russell was also a populariser of [[philosophy]] and a commentator on a large variety of topics, ranging from very serious issues to the mundane. Continuing a family tradition in [[politics|political]] affairs, he was a prominent [[liberal]] but also a [[socialist]] and [[anti-war]] [[activism|activist]] for most of his long life. Millions looked up to Russell as a prophet of the [[creativity|creative]] and [[rationality|rational]] life; at the same time, his stances on many topics were extremely controversial. |

|||

He was one of the early 20th century's prominent [[logic]]ians<ref name="stanford" /> and a founder of [[analytic philosophy]], along with his predecessor [[Gottlob Frege]], his friend and colleague [[G. E. Moore]], and his student and protégé [[Ludwig Wittgenstein]]. Russell with Moore led the British "revolt against [[British idealism|idealism]]".{{efn |Russell and G. E. Moore broke themselves free from [[British Idealism]] which, for nearly 90 years, had been dominating [[British philosophy]]. Russell would later recall that "with a sense of escaping from prison, we allowed ourselves to think that grass is green, that the sun and stars would exist if no one was aware of them{{nbsp}}..."<ref>Russell B, (1944) "My Mental Development", in, Paul Arthur Schilpp: ''The Philosophy of Bertrand Russell'', New York: Tudor, 1951, pp. 3–20.</ref>}} Together with his former teacher [[Alfred North Whitehead|A. N. Whitehead]], Russell wrote ''[[Principia Mathematica]]'', a milestone in the development of [[classical logic]] and a major attempt to reduce the whole of mathematics to [[logic]] (see [[Logicism]]). Russell's article "[[On Denoting]]" has been considered a "paradigm of philosophy".<ref>{{Cite web |last=Ludlow |first=Peter |title=Descriptions, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2008 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.) |url=http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2008/entries/descriptions/}}</ref> |

|||

Born at the height of [[United Kingdom|Britain]]'s [[economics|economic]] and political ascendancy, he died of [[influenza]] nearly a century later when Britain's [[empire]] had all but vanished; her power had dissipated in two victorious, but debilitating [[world war]]s. As one of the world's best-known [[intellectual]]s, Russell's voice carried enormous [[morality|moral]] [[authority]], even into his early 90s. Among his other political activities, Russell was a vigorous proponent of [[nuclear disarmament]] and an outspoken [[critic]] of the [[Vietnam War|American war in Vietnam]]. |

|||

Russell was a pacifist who championed [[anti-imperialism]] and chaired the [[India League]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Rempel |first=Richard |year=1979 |title=From Imperialism to Free Trade: Couturat, Halevy and Russell's First Crusade |journal=Journal of the History of Ideas |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press |volume=40 |issue=3 |pages=423–443 |doi=10.2307/2709246 |jstor=2709246}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Russell |first=Bertrand |title=Political Ideals |publisher=Routledge |year=1988 |isbn=0-415-10907-8 |orig-date=1917}}</ref><ref name=":1" /> He went to prison for his pacifism during [[World War I]],<ref>Samoiloff, Louise Cripps. ''C .L. R. James: Memories and Commentaries'', p. 19. Associated University Presses, 1997. {{ISBN|0-8453-4865-5}}</ref> and initially supported appeasement against [[Adolf Hitler]]'s [[Nazi Germany]], before changing his view in 1943, describing war as a necessary "lesser of two evils". In the wake of [[World War II]], he welcomed American global [[hegemony]] in preference to either [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] hegemony or no (or ineffective) world leadership, even if it were to come at the cost of using their nuclear weapons.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Russell |first=Bertrand |date=October 1946 |title=Atomic Weapon and the Prevention of War |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WwwAAAAAMBAJ |website=Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 2/7–8, (1 October 1946) |page=20}}</ref> He would later criticise [[Stalinism|Stalinist]] [[totalitarianism]], condemn the United States' involvement in the [[Vietnam War]], and become an outspoken proponent of [[nuclear disarmament]].<ref name="Gallery">{{Cite web |date=6 June 2011 |title=The Bertrand Russell oGallery |url=http://russell.mcmaster.ca/~bertrand |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110928232717/http://russell.mcmaster.ca/~bertrand |archive-date=28 September 2011 |access-date=1 October 2011 |website=Russell.mcmaster.ca}}</ref> |

|||

In [[1950]], Russell was made a [[Nobel Prize|Nobel Laureate]] in [[Nobel Prize in Literature|Literature]] "in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions [[humanitarian]] ideals and [[freethought|freedom of thought]]". |

|||

In 1950, Russell was awarded the [[1950 Nobel Prize in Literature|Nobel Prize in Literature]] "in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and [[freedom of thought]]".<ref>[https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1950/index.html The Nobel Prize in Literature 1950 — Bertrand Russell] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180702151048/https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1950/index.html |date=2 July 2018 }} Retrieved on 22 March 2013.</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=13 April 2014 |title=British Nobel Prize Winners (1950) |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9to64vR8RvQ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/varchive/youtube/20211123/9to64vR8Rv |archive-date=23 November 2021 |via=YouTube}}{{cbignore}}</ref> He was also the recipient of the [[De Morgan Medal]] (1932), [[Sylvester Medal]] (1934), [[Kalinga Prize]] (1957), and [[Jerusalem Prize]] (1963). |

|||

== Biography == |

|||

==Biography== |

|||

[[Image:BertrandRussell1.jpg|thumb|left|The young Russell]] |

|||

===Early life and background=== |

|||

Bertrand Arthur William Russell was born at [[Cleddon Hall|Ravenscroft]], a country house in [[Trellech]], [[Monmouthshire (historic)|Monmouthshire]],{{efn|name=fn1|At the time of Russell's birth, some considered Monmouthshire to be part of Wales and some part of England. See [[Monmouthshire (historic)#Ambiguity over status]].}}<!--Whether Monmouthshire was in Wales in 1872 is debatable. Please leave this alone; this page is not the place for this debate--> on 18 May 1872, into an influential and liberal family of the [[British aristocracy]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hestler |first=Anna |url=https://archive.org/details/wales00hest/page/53 |title=Wales |publisher=Marshall Cavendish |year=2001 |isbn=978-0-7614-1195-6 |page=[https://archive.org/details/wales00hest/page/53 53]}}</ref><ref>Sidney Hook, "Lord Russell and the War Crimes Trial", ''Bertrand Russell: critical assessments'', Vol. 1, edited by A. D. Irvine, New York 1999, p. 178.</ref> His parents were [[John Russell, Viscount Amberley|Viscount]] and [[Katharine Russell, Viscountess Amberley|Viscountess Amberley]]. Lord Amberley consented to his wife's affair with their children's tutor,<ref>{{Cite news |date=3 February 1970 |title=Bertrand Russell Is Dead; British Philosopher, 97 |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1970/02/03/archives/bertrand-russell-is-dead-british-philosopher-97-bertrand-russell.html |access-date=14 April 2022 |issn=0362-4331}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |date=8 November 1877 |title=Douglas A. Spalding |work=[[Nature (journal)|Nature]] |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/017035b0 |access-date=14 April 2022 |issn=1476-4687}}</ref> the biologist [[Douglas Spalding]]. Both were early advocates of [[birth control]] at a time when this was considered scandalous.<ref name="calicut">{{Cite web |last=Paul |first=Ashley |title=Bertrand Russell: The Man and His Ideas |url=http://www.geocities.com/vu3ash/index.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060501064331/http://www.geocities.com/vu3ash/index.html |archive-date=1 May 2006 |access-date=28 October 2007}}</ref> Lord Amberley was a [[deist]], and even asked the philosopher [[John Stuart Mill]] to act as Russell's secular godfather.<ref>Russell, Bertrand and [[Ray Perkins, Jr.|Perkins, Ray]] (ed.) ''Yours faithfully, Bertrand Russell''. Open Court Publishing, 2001, p. 4.</ref> Mill died the year after Russell's birth, but his writings later influenced Russell's life. |

|||

[[File:Bertrand Russell in 1876.jpg|thumb|upright|left|Russell as a 4-year-old]] |

|||

Bertrand Russell was born on [[18 May]] [[1872]] at [[Trellech]], [[Monmouthshire]], [[Wales]], into an [[aristocratic]] [[English people|English]] family. His paternal grandfather, [[John Russell, 1st Earl Russell|John Russell, the 1st Earl Russell]], had been [[Prime Minister]] in the [[1840s]] and [[1860s]], and was the second son of the [[John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford|6th Duke of Bedford]]. The Russells had been prominent for several centuries in Britain, and were one of Britain's leading [[Whig]] (Liberal) families. Russell's mother Kate was also from an aristocratic family, and was the sister of [[Rosalind Howard]], Countess of Carlisle. His parents were quite radical for their times—Russell's father, [[Viscount Amberley]], was an atheist and consented to his wife's affair with their children's tutor, the [[biologist]] [[Douglas Spalding]]. [[John Stuart Mill]], the [[Utilitarianism|Utilitarian]] philosopher, was Russell's [[Godparent|godfather]]. |

|||

His paternal grandfather, Lord John Russell, later 1st [[John Russell, 1st Earl Russell|Earl Russell]] (1792–1878), had twice been [[Prime Minister of the United Kingdom|prime minister]] in the 1840s and 1860s.<ref name="John R">{{Cite web |last=Bloy |first=Marjie |title=Lord John Russell (1792–1878) |url=http://www.victorianweb.org/history/pms/russell.html |access-date=28 October 2007}}</ref> A member of Parliament since the early 1810s, he met with [[Napoleon Bonaparte]] in [[Elba]].<ref>{{Citation |title=My Grandfather Met Napoleon: Bertrand Russell Interview 1952 – Enhanced Video & Audio [60 fps] |author=((Life in the 1800s)) |date=Apr 23, 2022 |website=YouTube |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4OXtO92x5KA |language=en |access-date=2 May 2022}}</ref> The Russells had been prominent in England for several centuries before this, coming to power and the [[peerage]] with the rise of the [[Tudor dynasty]] (see: [[Duke of Bedford]]). They established themselves as one of the leading [[British Whig Party|Whig]] families and participated in political events from the [[dissolution of the monasteries]] in 1536–1540 to the [[Glorious Revolution]] in 1688–1689 and the [[Great Reform Act]] in 1832.<ref name="John R" /><ref name="peerage">G. E. Cokayne; Vicary Gibbs, H. A. Doubleday, Geoffrey H. White, Duncan Warrand and Lord Howard de Walden, eds. The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct or Dormant, new ed. 13 volumes in 14. 1910–1959. Reprint in 6 volumes, Gloucester, UK: Alan Sutton Publishing, 2000.</ref> |

|||

Lady Amberley was the daughter of [[Edward Stanley, 2nd Baron Stanley of Alderley|Lord]] and [[Henrietta Stanley, Baroness Stanley of Alderley|Lady Stanley of Alderley]].<ref name="Gallery" /> Russell often feared the ridicule of his maternal grandmother,<ref name="Booth">{{Cite book |last=Booth |first=Wayne C. |url=https://archive.org/details/moderndogmarhet00boot |title=Modern Dogma and the Rhetoric of Assent |publisher=University of Chicago Press |year=1974 |isbn=0-226-06572-3 |access-date=6 December 2012 |url-access=registration}}</ref> one of the campaigners for [[education of women]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Crawford |first=Elizabeth |title=The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide, 1866–1928}}</ref> |

|||

Russell had two older siblings: Frank (nearly seven years older than Bertrand), and Rachel (four years older). In June [[1875]] Russell's mother died of [[diphtheria]], followed shortly by Rachel, and in January [[1876]] his father died of [[bronchitis]] following a long period of [[depression]]. Frank and Bertrand were placed in the care of their staunchly [[Victorian morality|Victorian]] grandparents, who lived at [[Pembroke Lodge, Richmond Park|Pembroke Lodge]] in [[Richmond Park]]. The first Earl Russell died in [[1878]], and his widow the Countess Russell (nee Lady Frances Elliot) was the dominant family figure for the rest of Russell's childhood and youth. The countess was very religious, and her influence on his outlook on [[social justice]] and standing up for principle remained with him throughout his life. However, the atmosphere at Pembroke Lodge was one of repression and formality. Frank reacted to this with open rebellion, but the young Bertrand learned to hide his feelings. |

|||

===Childhood and adolescence=== |

|||

Russell's [[adolescence]] was very lonely, and he often contemplated [[suicide]]. He remarked in his autobiography that his keenest interests were in sex, religion and mathematics, and that only the wish to know more mathematics kept him from suicide. He was educated at home by a series of tutors, and he spent countless hours in his grandfather's library. His brother Frank introduced him to [[Euclid]], which transformed Russell's life. |

|||

Russell had two siblings: brother [[Frank Russell, 2nd Earl Russell|Frank]] (seven years older), and sister Rachel (four years older). In June 1874, Russell's mother died of [[diphtheria]], followed shortly by Rachel's death. In January 1876, his father died of [[bronchitis]]<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Brink |first=Andrew |date=1982 |title=Death, Depression and Creativity: A Psychobiological Approach to Bertrand Russell |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/24777750 |journal=Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature |volume=15 |issue=1 |issn=0027-1276 |page=93 }}</ref> after a long period of [[Major depressive disorder|depression]].<ref name="Monk1996">{{Cite book |last=Monk |first=Ray |url={{Google books|AzssomBIDRIC|plainurl=y}} |title=Bertrand Russell: The Spirit of Solitude, 1872–1921 |publisher=Simon and Schuster |year=1996 |isbn=978-0-684-82802-2}}</ref>{{rp|p=14}} Frank and Bertrand were placed in the care of [[Victorian morality|Victorian]] paternal grandparents, who lived at [[Pembroke Lodge, Richmond Park|Pembroke Lodge]] in [[Richmond Park]]. His grandfather, former Prime Minister [[John Russell, 1st Earl Russell|Earl Russell]], died in 1878, and was remembered by Russell as a kind old man in a wheelchair. His grandmother, the [[Frances Russell, Countess Russell|Countess Russell]] (née Lady Frances Elliot), was the central family figure for the rest of Russell's childhood and youth.<ref name="Gallery" /><ref name="calicut" /> |

|||

The Countess was from a Scottish [[Presbyterian]] family and petitioned the [[Court of Chancery]] to set aside a provision in Amberley's will requiring the children to be raised as agnostics. Despite her religious conservatism, she held progressive views in other areas (accepting [[Darwinism]] and supporting [[Home Rule|Irish Home Rule]]), and her influence on Bertrand Russell's outlook on [[social justice]] and standing up for principle remained with him throughout his life. Her favourite Bible verse, "Thou shalt not follow a multitude to do evil",<ref>{{Bibleverse |Exodus |23:2 |KJV}}</ref> became his motto. The atmosphere at Pembroke Lodge was one of frequent prayer, emotional repression and formality; Frank reacted to this with open rebellion, but the young Bertrand learned to hide his feelings. |

|||

Russell won a scholarship to read [[mathematics]] at [[Trinity College]], [[University of Cambridge|Cambridge University]], and commenced his studies there in [[1890]]. He became acquainted with the younger [[George Edward Moore|G.E. Moore]] and came under the influence of [[Alfred North Whitehead]], who recommended him to the [[Cambridge Apostles]]. He quickly distinguished himself in mathematics and philosophy, graduating with a B.A. in the former subject in 1893 and adding a fellowship in the latter in 1895. |

|||

[[File:Pembroke Lodge, Richmond Park.jpg|thumb|Childhood home, [[Pembroke Lodge, Richmond Park|Pembroke Lodge]], Richmond Park, London]] |

|||

Russell first met the American [[Religious Society of Friends|Quaker]], [[Alys Pearsall Smith]], when he was seventeen years old. He fell in love with the puritanical, high-minded Alys, who was connected to several educationists and religious activists, and, contrary to his grandmother's wishes, he married her in December [[1894]]. Their [[marriage]] began to fall apart in [[1902]] when Russell realised he no longer loved her; they divorced nineteen years later. During this period, Russell had passionate (and often simultaneous) affairs with, among others, Lady [[Ottoline Morrell]] and the [[actress]] Lady [[Constance Malleson]]. Alys pined for him for these years and continued to love Russell for the rest of her life. |

|||

Russell's adolescence was lonely and he contemplated suicide. He remarked in his autobiography that his interests in "nature and books and (later) mathematics saved me from complete despondency;"<ref>''The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell'' (Volume I, 1872–1914) George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1971, page 31;</ref> only his wish to know more mathematics kept him from suicide.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bertrand Russell |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SlMrmmrNuEoC |title=Autobiography |publisher=Psychology Press |year=1998 |isbn=978-0-415-18985-9 |page=38}}</ref> He was educated at home by a series of tutors.<ref name="nobel prize">The Nobel Foundation (1950). [http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1950/russell-bio.html Bertrand Russell: The Nobel Prize in Literature 1950] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110604131349/http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1950/russell-bio.html |date=4 June 2011 }}. Retrieved 11 June 2007.</ref> When Russell was eleven years old, his brother Frank introduced him to the work of [[Euclid]], which he described in his autobiography as "one of the great events of my life, as dazzling as first love".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Russell |first=Bertrand |url={{Google books|dVBpAwAAQBAJ|page=30|plainurl=y}} |title=The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell: 1872–1914 |publisher=Routledge |year=2000 |location=New York |page=30 |orig-date=1967}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Paul |first=Ashley |title=Bertrand Russell: The Man and His Ideas – Chapter 2 |url=http://www.geocities.com:80/vu3ash/index.htm2.htm |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090101073812/http://www.geocities.com/vu3ash/index.htm2.htm |archive-date=1 January 2009 |access-date=6 December 2018}}</ref> |

|||

During these formative years he also discovered the works of [[Percy Bysshe Shelley]]. Russell wrote: "I spent all my spare time reading him, and learning him by heart, knowing no one to whom I could speak of what I thought or felt, I used to reflect how wonderful it would have been to know Shelley, and to wonder whether I should meet any live human being with whom I should feel so much sympathy."<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bertrand Russell |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SlMrmmrNuEoC |title=Autobiography |publisher=Psychology Press |year=1998 |isbn=978-0-415-18985-9 |page=35}}</ref> Russell claimed that beginning at age 15, he spent considerable time thinking about the validity of [[Dogma#In religion|Christian religious dogma]], which he found unconvincing.<ref>{{Cite web |year=1959 |title=1959 Bertrand Russell CBC interview |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tP4FDLegX9s |website=YouTube}}</ref> At this age, he came to the conclusion that there is no [[free will]] and, two years later, that there is no life after death. Finally, at the age of 18, after reading Mill's ''Autobiography'', he abandoned the "[[First Cause]]" argument and became an [[atheist]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bertrand Russell |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SlMrmmrNuEoC |title=Autobiography |publisher=Psychology Press |year=1998 |isbn=978-0-415-18985-9 |chapter=2: Adolescence}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |year=1959 |title=Bertrand Russell on God |url=http://richarddawkins.net/articles/4833 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100126090302/http://richarddawkins.net/articles/4833 |archive-date=26 January 2010 |access-date=8 March 2010 |publisher=[[Canadian Broadcasting Corporation]]}}</ref> |

|||

Russell began his published work in 1896 with ''[[Germany|German]] [[Social Democracy]]'', a study in politics that was an early indication of a lifelong interest in political and social theory. In 1896 he taught German social democracy at the [[London School of Economics]], where he also lectured on the science of power in the fall of 1937. |

|||

He travelled to the continent in 1890 with an American friend, [[Edward FitzGerald (mountaineer)|Edward FitzGerald]], and with FitzGerald's family he visited the [[Paris Exhibition of 1889]] and climbed the [[Eiffel Tower]] soon after it was completed.<ref name="Russell1967a">{{Cite book |last=Russell |first=Bertrand |url={{Google books|dVBpAwAAQBAJ|page=39|plainurl=y}} |title=The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell: 1872–1914 |publisher=Routledge |year=2000 |location=New York |page=39 |orig-date=1967}}</ref> |

|||

Russell became a fellow of the [[Royal Society]] in [[1908]]. The first of three volumes of ''[[Principia Mathematica]]'' (written with Whitehead) was published in [[1910]], which (along with the earlier ''The Principles of Mathematics'') soon made Russell world famous in his field. In [[1911]] he became acquainted with the Austrian engineering student, [[Ludwig Wittgenstein]], whose genius he soon recognised (and who he viewed as a successor who would continue his work on mathematical logic). He spent hours dealing with Wittgenstein's various phobias and his frequent bouts of despair. The latter was often a drain on Russell's energy, but he continued to be fascinated by him and encouraged his [[academic]] development, including the publication of Wittgenstein's ''[[Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus]]'' in [[1922]]. |

|||

===Education=== |

|||

During the [[First World War]], Russell engaged in pacifist activities, and in [[1916]] he was dismissed from [[Trinity College, Cambridge|Trinity College]] following his conviction under the Defence of the Realm Act. A later conviction resulted in six months' imprisonment in [[Brixton prison]] (see ''[[Bertrand_Russell#Russell.27s_activism|Activism]]''). |

|||

[[File:Portrait of Bertrand Russell in 1893.jpg|thumb|upright|Russell at [[Trinity College, Cambridge]], in 1893]] |

|||

Russell won a scholarship to read for the [[Mathematical Tripos]] at [[Trinity College, Cambridge]], and began his studies there in 1890,<ref>{{acad |id=RSL890BA|name=Russell, the Hon. Bertrand Arthur William}}</ref> taking as coach [[Robert Rumsey Webb]]. He became acquainted with the younger [[George Edward Moore]] and came under the influence of [[Alfred North Whitehead]], who recommended him to the [[Cambridge Apostles]]. He distinguished himself in mathematics and philosophy, graduating as seventh [[Wrangler (University of Cambridge)|Wrangler]] in the former in 1893 and becoming a Fellow in the latter in 1895.<ref name="Whitehead">{{Cite web |last1=O'Connor |first1=J. J. |last2=Robertson, E. F. |date=October 2003 |title=Alfred North Whitehead |url=http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Whitehead.html |access-date=8 November 2007 |publisher=School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland}}</ref><ref name="JSTOR">{{Cite journal |last1=Griffin |first1=Nicholas |author-link=Nicholas Griffin (philosopher) |last2=Lewis |first2=Albert C. |year=1990 |title=Russell's Mathematical Education |journal=Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London |volume=44 |issue=1 |pages=51–71 |doi=10.1098/rsnr.1990.0004 |jstor=531585 |doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

In [[1920]], Russell travelled to [[Russia]] as part of an official delegation sent by the British government to investigate the effects of the [[Russian Revolution]]. Russell's lover [[Dora Black]] also visited Russia independently at the same time - she was enthusiastic about the revolution, but Russell's experiences destroyed his previous tentative support for it. |

|||

===Early career=== |

|||

Russell subsequently lectured in [[Peking]] on philosophy for one year, accompanied by Dora. While in China, Russell became gravely ill with [[pneumonia]], and [[List of premature obituaries|incorrect reports]] of his death were published in the Japanese press. When the couple visited Japan on their return journey, Dora notified journalists that "Mr Bertrand Russell, having died according to the Japanese press, is unable to give interviews to Japanese journalists". |

|||

{{see also|Axiom of reducibility}} |

|||

Russell began his published work in 1896 with ''German Social Democracy'', a study in politics that was an early indication of his interest in political and social theory. In 1896 he taught German social democracy at the [[London School of Economics]].<ref name="LSE">{{Cite web |date=26 August 2015 |title=London School of Economics |url=https://www.lse.ac.uk/aboutLSE/keyFacts/nobelPrizeWinners/russell.aspx |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141015192808/https://www.lse.ac.uk/aboutLSE/keyFacts/nobelPrizeWinners/russell.aspx |archive-date=15 October 2014 |publisher=London School of Economics}}</ref> He was a member of the [[Coefficients (dining club)|Coefficients dining club]] of social reformers set up in 1902 by the [[Fabian Society|Fabian]] campaigners [[Sidney Webb|Sidney]] and [[Beatrice Webb]].<ref name="LettersPg16">{{Cite book |last=Russell |first=Bertrand |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EayyTTpXL-QC&pg=PA16 |title=Yours Faithfully, Bertrand Russell: Letters to the Editor 1904–1969 |publisher=Open Court Publishing |year=2001 |isbn=0-8126-9449-X |editor-last=Ray Perkins |location=Chicago |page=16 |access-date=16 November 2007}}</ref> |

|||

He now started a study of the [[foundations of mathematics]] at Trinity. In 1897, he wrote ''An Essay on the Foundations of Geometry'' (submitted at the [[Fellow]]ship Examination of Trinity College) which discussed the [[Cayley–Klein metric]]s used for [[non-Euclidean geometry]].<ref>Russell, Bertrand (1897) ''An Essay on the Foundations of Geometry'', p. 32, re-issued 1956 by [[Dover Books]]</ref> He attended the first [[International Congress of Philosophy]] in Paris in 1900 where he met [[Giuseppe Peano]] and [[Alessandro Padoa]]. The Italians had responded to [[Georg Cantor]], making a science of [[set theory]]; they gave Russell their literature including the ''[[Formulario mathematico]]''. Russell was impressed by the precision of Peano's arguments at the Congress, read the literature upon returning to England, and came upon [[Russell's paradox]]. In 1903 he published ''[[The Principles of Mathematics]]'', a work on foundations of mathematics. It advanced a thesis of [[logicism]], that mathematics and logic are one and the same.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Bertrand Russell, biography |url=http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1950/russell-bio.html |access-date=23 June 2010 |publisher=Nobel Foundation}}</ref> |

|||

On the couple's return to England in [[1921]], Dora was five months pregnant, and Russell arranged a hasty divorce from Alys, marrying Dora six days after the divorce was finalised. Their children were [[John Conrad Russell, 4th Earl Russell|John Conrad Russell]] and [[Katharine Russell|Katharine Jane Russell]] (now Lady Katharine Tait). Russell supported himself during this time by writing popular books explaining matters of physics, ethics and [[education]] to the layman. Together with Dora, he also founded the experimental [[Beacon Hill School]] in [[1927]]. After he left the school in 1932, Dora continued it until 1943. |

|||

At the age of 29, in February 1901, Russell underwent what he called a "sort of mystic illumination", after witnessing [[Alfred North Whitehead|Whitehead]]'s wife's suffering in an [[Angina pectoris|angina]] attack. "I found myself filled with semi-mystical feelings about beauty and with a desire almost as profound as that of the [[Buddha]] to find some philosophy which should make human life endurable", Russell would later recall. "At the end of those five minutes, I had become a completely different person."<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bertrand Russell |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SlMrmmrNuEoC |title=Autobiography |publisher=Psychology Press |year=1998 |isbn=978-0-415-18985-9 |chapter=6: Principia Mathematica}}</ref> |

|||

Upon the death of his elder brother Frank, in [[1931]], Russell became the 3rd Earl Russell. He once said that his [[title]] was primarily useful for securing [[hotel]] rooms and the like. |

|||

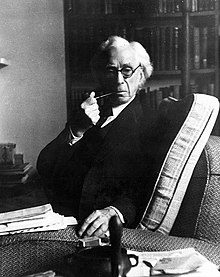

[[Image:BertrandRussell2.jpg|thumb|right|An old Russell]] |

|||

In 1905, he wrote the essay "[[On Denoting]]", which was published in the philosophical journal ''[[Mind (journal)|Mind]]''. Russell was elected a [[List of Fellows of the Royal Society elected in 1908|Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1908]].<ref name="frs" /><ref name="Gallery" /> The three-volume ''[[Principia Mathematica]]'', written with Whitehead, was published between 1910 and 1913. This, along with the earlier ''The Principles of Mathematics'', soon made Russell world-famous in his field. Russell's first political activity was as the [[Independent Liberal]] candidate in the [[1907 Wimbledon by-election|1907 by-election]] for the [[Wimbledon (UK Parliament constituency)|Wimbledon constituency]], where he was not elected.<ref>{{cite book|editor1-last=Craig|editor1-first=F. W. S.|title=British Parliamentary Election Results: 1885–1918|date=1974|publisher=Macmillan Press|location=London|isbn=9781349022984}}</ref> |

|||

Russell's marriage to Dora grew increasingly tenuous, and it reached a breaking point over her having two children with an American [[journalist]], [[Griffin Barry]]. In [[1936]], he took as his third wife an [[University of Oxford|Oxford]] undergraduate named Patricia ("Peter") Spence, who had been his children's [[governess]] since the summer of [[1930]]. Russell and Peter had one son, [[Conrad Russell, 5th Earl Russell|Conrad Sebastian Robert Russell]], later to become a prominent historian, and one of the leading figures in the [[Liberal Democrats (UK)|Liberal Democrat]] party. |

|||

In 1910, he became a lecturer at the [[University of Cambridge]], Trinity College, where he had studied. He was considered for a fellowship, which would give him a vote in the college government and protect him from being fired for his opinions, but was passed over because he was "anti-clerical", because he was agnostic. He was approached by the Austrian engineering student [[Ludwig Wittgenstein]], who became his PhD student. Russell viewed Wittgenstein as a successor who would continue his work on logic. He spent hours dealing with Wittgenstein's various [[phobia]]s and his bouts of despair. This was a drain on Russell's energy, but Russell continued to be fascinated by him and encouraged his academic development, including the publication of Wittgenstein's ''[[Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus]]'' in 1922.<ref name="Wittgenstein">{{Cite web |title=Russell on Wittgenstein |url=http://www.rbjones.com/rbjpub/philos/history/rvw001.htm |access-date=1 October 2011 |website=Rbjones.com}}</ref> Russell delivered his lectures on [[logical atomism]], his version of these ideas, in 1918, before the end of [[World War I]]. Wittgenstein was, at that time, serving in the Austrian Army and subsequently spent nine months in an Italian [[prisoner of war]] camp at the end of the conflict. |

|||

In the spring of [[1939]], Russell moved to [[Santa Barbara, California|Santa Barbara]] to lecture at the [[University of California, Los Angeles]]. He was appointed professor at the [[City College of New York]] in 1940, but after public outcries, the appointment was annulled by the [[court]]s: his [[radical]] opinions made him "morally unfit" to teach at the college. The protest was originated by the mother of a student who would not have been eligible for his graduate-level course in abstract, mathematical logic. Many intellectuals, led by [[John Dewey]], protested his treatment. Dewey and [[Horace M. Kallen]] edited a collection of articles on the CCNY affair in ''[[The Bertrand Russell Case]]''. He soon joined the [[Barnes Foundation of Philadelphia|Barnes Foundation]], lecturing to a varied audience on the history of philosophy - these lectures formed the basis of ''[[History of Western Philosophy (Russell)|A History of Western Philosophy]]''. His relationship with the eccentric [[Albert C. Barnes]] soon soured, and he returned to Britain in [[1944]] to rejoin the faculty of Trinity College. |

|||

===First World War=== |

|||

During the 1940s and 1950s, Russell participated in many broadcasts over the [[BBC]] on various topical and philosophical subjects. By this time in his life, Russell was world [[famous]] outside of academic circles, frequently the subject or author of [[magazine]] and [[newspaper]] articles, and was called upon to offer up opinions on a wide variety of subjects, even mundane ones. ''A History of Western Philosophy'' ([[1945]]) became a best-seller, and provided Russell with a steady income for the remainder of his life. Along with his friend [[Einstein]], Russell had reached superstar status as an intellectual. In [[1949]], Russell was awarded the [[Order of Merit]], and the following year he received the [[Nobel Prize in Literature]]. |

|||

[[File:National Committee of the No-Conscription Fellowship May 1916.gif|thumb|right|Russell served on the National Committee of the [[No-Conscription Fellowship]], shown here in May 1916 (''back right'').<ref>{{Citation |last=Cyril Pearce |title='Typical' Conscientious Objectors — A Better Class of Conscience? No-Conscription Fellowship image management and the Manchester contribution 1916–1918 |work=Manchester Region History Review |volume=17 |issue=1 |page=38 |year=2004}}</ref>]] |

|||

During [[World War I]], Russell was one of the few people to engage in active [[opposition to World War I|pacifist activities]]. In 1916, because of his lack of a fellowship, he was dismissed from Trinity College following his conviction under the [[Defence of the Realm Act 1914]].<ref>{{Cite news |last=Hochschild |first=Adam |year=2011 |title=I Tried to Stop the Bloody Thing |work=The American Scholar |url=http://www.theamericanscholar.org/i-tried-to-stop-the-bloody-thing/ |access-date=10 May 2011}}</ref> He later described this, in ''[[Free Thought and Official Propaganda]]'', as an illegitimate means the state used to violate freedom of expression. Russell championed the case of [[Eric Chappelow]], a poet jailed and abused as a conscientious objector.<ref name="Moorehead">[[Caroline Moorehead]], ''Bertrand Russell: A Life'' (1992), p. 247.</ref> Russell played a part in the ''Leeds Convention'' in June 1917, a historic event which saw well over a thousand "anti-war socialists" gather; many being delegates from the [[Independent Labour Party]] and the Socialist Party, united in their pacifist beliefs and advocating a peace settlement.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Scharfenburger |first=Paul |date=17 October 2012 |title=1917 |url=http://musicandhistory.com/music-and-history-by-the-year/178-1917.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120117062625/http://musicandhistory.com/music-and-history-by-the-year/178-1917.html |archive-date=17 January 2012 |access-date=7 January 2014 |website=MusicandHistory.com}}</ref> The international press reported that Russell appeared with a number of Labour [[Member of Parliament (United Kingdom)|Members of Parliament]] (MPs), including [[Ramsay MacDonald]] and [[Philip Snowden]], as well as former [[Liberal Party (UK)|Liberal]] MP and anti-conscription campaigner, Professor [[Arnold Lupton]]. After the event, Russell told Lady Ottoline Morrell that, "to my surprise, when I got up to speak, I was given the greatest ovation that was possible to give anybody".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Russell |first=Bertrand |title=Pacifism and Revolution |publisher=Routledge |year=1995 |page=xxxiv |chapter=A Summer of Hope}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=5 June 1917 |title=British Socialists – Peace Terms Discussed |url=http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15731745 |access-date=7 January 2014 |website=The Sydney Morning Herald}}</ref> |

|||

His conviction in 1916 resulted in Russell being fined £100 ({{Inflation|UK|100|1917|fmt=eq|r=-2|cursign=£}}), which he refused to pay in hope that he would be sent to prison, but his books were sold at auction to raise the money. The books were bought by friends; he later treasured his copy of the [[King James Version|King James Bible]] that was stamped "Confiscated by Cambridge Police". |

|||

In [[1952]], Russell was divorced by Peter, with whom he had been very unhappy. Conrad, Russell's son by Peter, did not see his father between the time of the divorce and [[1968]] (at which time his decision to meet his father caused a permanent breach with his mother). Russell married his fourth wife, [[Edith Finch Russell|Edith Finch]], soon after the divorce. They had known each other since [[1925]], and Edith had lectured in English at [[Bryn Mawr College]] near [[Philadelphia]], sharing a house for twenty years with Russell's old friend Lucy Donnelly. Edith remained with him until his death, and, by all accounts, their relationship was close and loving throughout their marriage. Russell's eldest son, John, suffered from serious [[mental illness]], which was the source of ongoing disputes between Russell and John's mother, Russell's former wife, Dora. John's wife Susan was also mentally ill, and eventually Russell and Edith became the legal guardians of their three daughters (two of whom, in turn, were later diagnosed with [[schizophrenia]]). |

|||

A later conviction for publicly lecturing against inviting the United States to enter the war on the United Kingdom's side resulted in six months' imprisonment in [[HM Prison Brixton|Brixton Prison]] (see ''[[Bertrand Russell's political views]]'') in 1918 (he was prosecuted under the [[Defence of the Realm Act]]<ref>[https://russell-letters.mcmaster.ca/background The Brixton Letters]</ref>)<ref name="Pacifist">{{Cite book |last=Vellacott |first=Jo |title=Bertrand Russell and the Pacifists in the First World War |publisher=Harvester Press |year=1980 |isbn=0-85527-454-9 |location=Brighton}}</ref> He later said of his imprisonment: |

|||

Russell spent the 1950s and [[1960s]] engaged in various political causes, primarily related to nuclear disarmament and opposing the Vietnam War. He wrote a great many letters to world leaders during this period. He also became a hero to many of the youthful members of the [[New Left]]. During the 1960s, in particular, Russell became increasingly vocal about his disapproval of the American government's policies. |

|||

{{blockquote|I found prison in many ways quite agreeable. I had no engagements, no difficult decisions to make, no fear of callers, no interruptions to my work. I read enormously; I wrote a book, "Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy"... and began the work for "The Analysis of Mind". I was rather interested in my fellow-prisoners, who seemed to me in no way morally inferior to the rest of the population, though they were on the whole slightly below the usual level of intelligence as was shown by their having been caught.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bertrand Russell |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SlMrmmrNuEoC |title=Autobiography |publisher=Psychology Press |year=1998 |isbn=978-0-415-18985-9 |page=256 |chapter=8: The First War}}</ref>}} |

|||

Bertrand Russell published his three-volume autobiography in the late 1960s. While he grew frail, he remained lucid until the end, when, in [[1970]], he died in his home, [[Plas Penrhyn]], [[Penrhyndeudraeth]], [[Merioneth]], [[Wales]]. His ashes, as his will directed, were to be scattered. |

|||

While he was reading [[Lytton Strachey|Strachey]]'s ''[[Eminent Victorians]]'' chapter about [[Charles George Gordon|Gordon]] he laughed out loud in his cell prompting the warder to intervene and reminding him that "prison was a place of punishment".<ref>''The Selected Letters of Bertrand Russell'' by Bertrand Russell, [[Nicholas Griffin (philosopher)|Nicholas Griffin]] 2002, letter to Gladys Rinder on May 1918</ref> |

|||

== Russell's philosophical work == |

|||

Russell was reinstated to Trinity in 1919, resigned in 1920, was Tarner Lecturer in 1926 and became a Fellow again in 1944 until 1949.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Trinity in Literature |url=https://www.trin.cam.ac.uk/about/historical-overview/trinity-in-literature/ |access-date=3 August 2017 |publisher=Trinity College}}</ref> |

|||

=== Analytic philosophy === |

|||

In 1924, Russell again gained press attention when attending a "banquet" in the [[House of Commons of the United Kingdom|House of Commons]] with well-known campaigners, including [[Arnold Lupton]], who had been an [[Member of Parliament (United Kingdom)|MP]] and had also endured imprisonment for "passive resistance to military or naval service".<ref>{{Cite news |date=8 January 1924 |title=M. P.'s Who Have Been in Jail To Hold Banquet |work=The Reading Eagle |url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1955&dat=19240108&id=G28rAAAAIBAJ&pg=3245,1355607 |access-date=18 May 2014}}</ref> |

|||

Russell is generally recognised as one of the founders of [[analytic philosophy]], indeed, even of its several branches. At the beginning of the 20th century, alongside [[G. E. Moore]], Russell was largely responsible for the British "revolt against [[Idealism]]", a philosophy greatly influenced by [[Georg Hegel]] and his British apostle, [[F. H. Bradley]]. This revolt was echoed 30 years later in [[Vienna]] by the [[Logical_positivism|logical positivists]]' "revolt against metaphysics". Russell was particularly appalled by the [[idealist]] doctrine of internal [[relations]], which held that in order to know any particular thing, we must know all of its relations. Russell showed that this would make [[space]], [[time]], [[science]] and the concept of [[number]] unintelligible. Russell's logical work with [[Alfred North Whitehead|Whitehead]] continued this project. |

|||

===G. H. Hardy on the Trinity controversy=== |

|||

Russell and Moore strove to eliminate what they saw as [[meaning]]less and incoherent assertions in philosophy, and they sought clarity and precision in argument by the use of exact [[language]] and by breaking down philosophical [[propositions]] into their simplest components. Russell, in particular, saw logic and [[science]] as the principal tools of the philosopher. Indeed, unlike most philosophers who preceded him and his early contemporaries, Russell did not believe there was a separate method for philosophy. He believed that the main task of the philosopher was to illuminate the most general propositions about the [[world]] and to eliminate confusion. In particular, he wanted to end what he saw as the excesses of [[metaphysics]]. Russell adopted [[William of Occam]]'s principle against multiplying unnecessary entities, [[Occam's Razor]], as a central part of the method of analysis. |

|||

In 1941, [[G. H. Hardy]] wrote a 61-page pamphlet titled ''Bertrand Russell and Trinity'' – published later as a book by Cambridge University Press with a foreword by [[C. D. Broad]]—in which he gave an authoritative account of Russell's 1916 dismissal from Trinity College, explaining that a reconciliation between the college and Russell had later taken place and gave details about Russell's personal life. Hardy writes that Russell's dismissal had created a scandal since the vast majority of the Fellows of the College opposed the decision. The ensuing pressure from the Fellows induced the Council to reinstate Russell. In January 1920, it was announced that Russell had accepted the reinstatement offer from Trinity and would begin lecturing from October. In July 1920, Russell applied for a one year leave of absence; this was approved. He spent the year giving lectures in China and Japan. In January 1921, it was announced by Trinity that Russell had resigned and his resignation had been accepted. This resignation, Hardy explains, was voluntary and was not the result of another altercation. |

|||

The reason for the resignation, according to Hardy, was that Russell was going through a tumultuous time in his personal life with a divorce and subsequent remarriage. Russell contemplated asking Trinity for another one-year leave of absence but decided against it, since this would have been an "unusual application" and the situation had the potential to snowball into another controversy. Although Russell did the right thing, in Hardy's opinion, the reputation of the College suffered with Russell's resignation, since the 'world of learning' knew about Russell's altercation with Trinity but not that the rift had healed. In 1925, Russell was asked by the Council of Trinity College to give the ''Tarner Lectures'' on the Philosophy of the Sciences; these would later be the basis for one of Russell's best-received books according to Hardy: ''The Analysis of Matter'', published in 1927.<ref>{{Cite book |last=G. H. Hardy |title=Bertrand Russell and Trinity |year=1970 |pages=57–8}}</ref> In the preface to the Trinity pamphlet, Hardy wrote: |

|||

=== Epistemology === |

|||

{{blockquote|I wish to make it plain that Russell himself is not responsible, directly or indirectly, for the writing of the pamphlet.... I wrote it without his knowledge and, when I sent him the typescript and asked for his permission to print it, I suggested that, unless it contained misstatement of fact, he should make no comment on it. He agreed to this... no word has been changed as the result of any suggestion from him.}} |

|||

===Between the wars=== |

|||

Russell's [[epistemology]] went through many phases. Once he shed [[neo-Hegelianism]] in his early years, Russell remained a philosophical [[realist]] for the remainder of his life, believing that our direct experiences have primacy in the acquisition of knowledge. While some of his views have lost favour, his influence remains strong in the distinction between two ways in which we can be familiar with objects: "[[knowledge by acquaintance]]" and "[[knowledge by description]]". For a time, Russell thought that we could only be acquainted with our own [[sense data]]—momentary [[perception]]s of [[colours]], [[sounds]], and the like—and that everything else, including the [[physical]] objects that these were sense data ''of'', could only be inferred, or reasoned to—i.e. known by description—and not known directly. This distinction has gained much wider application, though Russell eventually rejected the idea of an intermediate sense datum. |

|||

In August 1920, Russell travelled to [[Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic|Soviet Russia]] as part of an official delegation sent by the British government to investigate the effects of the [[Russian Revolution of 1917|Russian Revolution]].<ref name="FreeLib">{{Cite web |title=Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) |url=http://russell.thefreelibrary.com/ |access-date=11 December 2007 |publisher=Farlex}}</ref> He wrote a four-part series of articles, titled "Soviet Russia—1920", for the magazine ''[[The Nation]]''.<ref name="nation1">{{Cite magazine |last=Russell |first=Bertrand |date=31 July 1920 |title=Soviet Russia{{emdash}}1920 |magazine=The Nation |pages=121–125}}</ref><ref name="sov1920">{{Cite journal |last=Russell |first=Bertrand |date=20 February 2008 |orig-date=1920 |title=Lenin, Trotzky and Gorky |url=https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/lenin-trotzky-and-gorky/ |journal=The Nation |access-date=20 August 2016}}</ref> He met [[Vladimir Lenin]] and had an hour-long conversation with him. In his autobiography, he mentions that he found Lenin disappointing, sensing an "impish cruelty" in him and comparing him to "an opinionated professor". He cruised down the [[Volga]] on a steamship. His experiences destroyed his previous tentative support for the revolution. He subsequently wrote a book, ''The Practice and Theory of Bolshevism'',<ref name="Practice &">Russell, Bertrand [http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/17350 ''The Practice and Theory of Bolshevism'' by Bertrand Russell] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120512073021/http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/17350 |date=12 May 2012 }}, 1920</ref> about his experiences on this trip, taken with a group of 24 others from the UK, all of whom came home thinking well of the Soviet regime, despite Russell's attempts to change their minds. For example, he told them that he had heard shots fired in the middle of the night and was sure that these were clandestine executions, but the others maintained that it was only cars backfiring.{{Citation needed|date=July 2014}} |

|||

[[File:Russell with John and Kate.jpg|thumb|left|Russell with his children, [[John Russell, 4th Earl Russell|John]] and [[Lady Katharine Tait|Kate]]]] |

|||

In his later philosophy, Russell subscribed to a kind of [[neutral monism]], maintaining that the distinctions between the [[material]] and [[mental]] worlds, in the final analysis, were arbitrary, and that both can be reduced to a neutral property—a view similar to one held by the American philosopher, [[William James]], and one that was first formulated by [[Baruch Spinoza]], whom Russell greatly admired. Instead of James' "pure experience", however, Russell characterised the stuff of our initial states of perception as "events", a stance which is curiously akin to his old teacher [[Alfred North Whitehead|Whitehead]]'s [[process philosophy]]. |

|||

Russell's lover [[Dora Russell|Dora Black]], a British author, [[feminist]] and socialist campaigner, visited Soviet Russia independently at the same time; in contrast to his reaction, she was enthusiastic about the [[October Revolution|Bolshevik revolution]].<ref name="Practice &"/> |

|||

The following year, Russell, accompanied by Dora, visited [[Peking]] (as [[Beijing]] was then known outside of China) to lecture on philosophy for a year.<ref name="nobel prize" /> He went with optimism and hope, seeing China as [[History of the Republic of China#Fight against warlordism and the First United Front|then being]] on a new path.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Russell |first=Bertrand |title=The Problem of China |date=1972 |publisher=George Allen & Unwin Ltd. |location=London |page=252}}</ref> Other scholars present in China at the time included [[John Dewey]]<ref name="pneumonia" /> and [[Rabindranath Tagore]], the Indian Nobel-laureate poet.<ref name="nobel prize" /> Before leaving China, Russell became gravely ill with [[pneumonia]], and [[List of premature obituaries|incorrect reports]] of his death were published in the Japanese press.<ref name="pneumonia">{{Cite news |date=21 April 1921 |title=Bertrand Russell Reported Dead |work=The New York Times |url=https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1921/04/21/107014047.pdf |url-status=live |access-date=11 December 2007 |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1921/04/21/107014047.pdf |archive-date=9 October 2022}}</ref> When the couple visited Japan on their return journey, Dora took on the role of spurning the local press by handing out notices reading "Mr. Bertrand Russell, having died according to the Japanese press, is unable to give interviews to Japanese journalists".<ref name="papers">{{Cite book |last=Russell |first=Bertrand |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qnaqY4gUyrAC&q=mr+bertrand+russell+having+died+according+to+the+japanese+press |chapter=Uncertain Paths to Freedom: Russia and China, 1919–22 |title=The Collected Papers of Bertrand Russell |publisher=Routledge |year=2000 |isbn=0-415-09411-9 |editor-first=Richard A. |editor-last=Rempel |volume=15 |page=lxviii |no-pp=true}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |first=Bertrand |last=Russell |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SlMrmmrNuEoC |title=Autobiography |publisher=Psychology Press |year=1998 |isbn=978-0-415-18985-9 |chapter=10: China |quote=It provided me with the pleasure of reading my obituary notices, which I had always desired without expecting my wishes to be fulfilled... As the Japanese papers had refused to contradict the news of my death, Dora gave each of them a type-written slip saying that as I was dead I could not be interviewed}}</ref> Apparently they found this harsh and reacted resentfully.{{Citation needed|date=July 2014|reason=The editor of Vol. 15 of his _Collected Papers_ seems to have put it, in the volume's Intro, "The press, not appreciating the sarcasm, were not amused." Conceivably the context justifies attributing that, with a proper ref, to that editor (but presumably not our stating it as what the press did, felt, or said), nor necessarily as Lord Russell's opinion. We do not use irony (fundamentally, because it interferes with consistently clearly stating the verifiable facts). It is also unlikely that even BR's use of it in this circumstance, even if verifiable as his words, rises above chit-chat and to the level of being worthy of mention as a *notable* utterance or opinion of his.}}<ref>{{Cite web |date=29 September 2011 |title=A man ahead of his time |url=https://www.weekinchina.com/2011/07/a-man-ahead-of-his-time/ |access-date=26 March 2021 |archive-date=3 March 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210303155105/https://www.weekinchina.com/2011/07/a-man-ahead-of-his-time/ |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Russell |first=Bertrand |title=The Problem of China |url=https://www.gutenberg.org/files/13940/13940-h/13940-h.htm}}</ref> Russell supported his family during this time by writing popular books explaining matters of [[physics]], ethics, and education to the layman. |

|||

=== Ethics === |

|||

{{multiple image|direction = vertical|width = 120|footer = Bertrand Russell in 1924|image1 = Bertrand Russell in 1924.jpg|image2 = Russell in 1924 01.jpg}} |

|||

While Russell wrote a great deal on ethical subject matters, he did not believe that the subject belonged to philosophy or that when he wrote on ethics that he did so in his capacity as a philosopher. In his earlier years, Russell was greatly influenced by [[G.E. Moore]]'s ''Principia Ethica''. Along with Moore, he then believed that moral facts were objective, but only known through [[intuition]], and that they were simple properties of objects, not [[equivalent]] (e.g., pleasure is good) to the natural objects to which they are often ascribed (see [[Naturalistic fallacy]]), and that these simple, undefinable moral properties cannot be analyzed using the non-moral properties with which they are associated. In time, however, he came to agree with his philosophical [[hero]], [[David Hume]], who believed that ethical terms dealt with [[subjective]] [[values]] that cannot be verified in the same way that matters of fact are. Coupled with Russell's other doctrines, this influenced the [[logical positivists]], who formulated the theory of [[emotivism]], which states that ethical propositions (along with those of [[metaphysics]]) were essentially meaningless and nonsensical or, at best, little more than expressions of [[attitude (psychology)|attitude]]s and [[preferences]]. Notwithstanding his influence on them, Russell himself did not construe ethical propositions as narrowly as the positivists, for he believed that ethical considerations are not only meaningful, but that they are a vital subject matter for [[civil]] discourse. Indeed, though Russell was often characterised as the [[patron saint]] of rationality, he agreed with Hume, who said that reason ought to be subordinate to ethical considerations. |

|||

From 1922 to 1927 the Russells divided their time between London and [[Cornwall]], spending summers in [[Porthcurno]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bertrand Russell |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SlMrmmrNuEoC |title=Autobiography |publisher=Psychology Press |year=1998 |isbn=978-0-415-18985-9 |page=386}}</ref> In the [[1922 United Kingdom general election|1922]] and [[1923 United Kingdom general election|1923 general elections]] Russell stood as a [[Labour Party (UK)|Labour Party]] candidate in the [[Chelsea (UK Parliament constituency)|Chelsea constituency]], but only on the basis that he knew he was unlikely to be elected in such a safe Conservative seat, and he was unsuccessful on both occasions. |

|||

After the birth of his two children, he became interested in education, especially [[early childhood education]]. He was not satisfied with the old [[traditional education]] and thought that [[progressive education]] also had some flaws;<ref>{{Cite web |title=A Conversation with Bertrand Russell (1952) |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fb3k6tB-Or8?t=824 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181124210430/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fb3k6tB-Or8 |archive-date=24 November 2018 |via=YouTube}}</ref> as a result, together with Dora, Russell founded the experimental Beacon Hill School in 1927. The school was run from a succession of different locations, including its original premises at the Russells' residence, Telegraph House, near [[Harting]], West Sussex. During this time, he published ''On Education, Especially in Early Childhood''. On 8 July 1930, Dora gave birth to her third child Harriet Ruth. After he left the school in 1932, Dora continued it until 1943.<ref name="Beacon">"Inside Beacon Hill: Bertrand Russell as Schoolmaster". Jespersen, Shirley ERIC# EJ360344, published 1987</ref><ref name="Dora">{{Cite web |date=12 May 2007 |title=Dora Russell |url=http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/TUrussellD.htm |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080119030738/http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/TUrussellD.htm |archive-date=19 January 2008 |access-date=17 February 2008}}</ref> |

|||

===Logical atomism=== |

|||

Perhaps Russell's most systematic, metaphysical treatment of philosophical analysis and his empiricist-centric logicism is evident in what he called [[Logical atomism]], which is explicated in a set of [[lectures]], "The Philosophy of Logical Atomism," which he gave in [[1918]]. In these lectures, Russell sets forth his [[concept]] of an [[ideal]], [[isomorphic]] language, one that would mirror the world, whereby our knowledge can be reduced to terms of atomic propositions and their [[truth-function]]al compounds. Logical atomism is a form of radical empiricism, for Russell believed the most important requirement for such an ideal language is that every meaningful proposition must consist of terms referring directly to the objects with which we are acquainted, or that they are defined by other terms referring to objects with which we are acquainted. Russell excluded certain formal, logical terms such as ''all'', ''the'', ''is'', and so forth, from his isomorphic requirement, but he was never entirely satisfied about our understanding of such terms. One of the central themes of Russell's atomism is that the world consists of logically independent facts, a plurality of facts, and that our knowledge depends on the data of our direct experience of them. In his later life, Russell came to doubt aspects of logical atomism, especially his principle of isomorphism, though he continued to believe that the process of philosophy ought to consist of breaking things down into their simplest components, even though we might not ever fully arrive at an ultimate [[atomic]] [[fact]]. |

|||

In 1927 Russell met [[Barry Stevens (therapist)|Barry Fox (later Barry Stevens)]], who became known [[Gestalt therapy|Gestalt therapist]] and writer in later years.<ref>Kranz, D. (2011): [http://www.gestalt.de/kranz_stevens_leben.html "Barry Stevens: Leben Gestalten"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180925150850/http://www.gestalt.de/kranz_stevens_leben.html |date=25 September 2018}}. In: ''Gestaltkritik'', 2/2011, p. 4–11.</ref> They developed an intense relationship, and in Fox's words: "...{{nbsp}}for three years we were very close."<ref>Stevens, B. (1970): ''Don't Push the River''. Lafayette, Cal. (Real People Press), p. 26.</ref> Fox sent her daughter Judith to Beacon Hill School.<ref>Gorham, D. (2005): "Dora and Bertrand Russell and Beacon Hill School", in: ''Russell: the Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies'', n.s. 25, (summer 2005), p. 39–76, p. 57.</ref> From 1927 to 1932 Russell wrote 34 letters to Fox.<ref>Spadoni, C. (1981): "Recent Acquisitions: Correspondence", in: ''Russell: the Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies'', Vol 1, Iss. 1, Article 6, 43–67.</ref> Upon the death of his elder brother Frank, in 1931, Russell became the 3rd [[Earl Russell]]. |

|||

=== Logic and mathematics === |

|||

Russell's marriage to Dora grew tenuous, and it reached a breaking point over her having two children with an American journalist, Griffin Barry.<ref name="Dora" /> They separated in 1932 and finally divorced. On 18 January 1936, Russell married his third wife, an [[University of Oxford|Oxford]] undergraduate named [[Patricia Russell (nee Spence)|Patricia ("Peter") Spence]], who had been his children's governess since 1930. Russell and Peter had one son, [[Conrad Russell, 5th Earl Russell|Conrad Sebastian Robert Russell]], 5th Earl Russell, who became a historian and one of the leading figures in the [[Liberal Democrats (UK)|Liberal Democrat]] party.<ref name="Gallery" /> |

|||

Russell was without peer in his contributions to modern [[mathematical logic]]. The American logician, [[Willard Quine]], said Russell's work represented the greatest influence on his own work. While subsequent systems have improved upon Russell's work in several areas (though certainly not all), modern logic rests largely on Russell's foundational work in the early part of the 20th century. |

|||

Russell returned in 1937 to the [[London School of Economics]] to lecture on the science of power.<ref name="LSE" /> During the 1930s, Russell became a friend and collaborator of [[V. K. Krishna Menon]], then President of the [[India League]], the foremost lobby in the United Kingdom for Indian independence.<ref name=":1">{{Cite book |title=India in Britain: South Asian Networks and Connections, 1858–1950 |date=2013 |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan |isbn=978-0-230-39271-7 |editor-last=Nasta |editor-first=Susheila |location=New York |oclc=802321049}}</ref> Russell chaired the India League from 1932 to 1939.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Nasta |first=Susheila |title=India League |url=http://www.open.ac.uk/researchprojects/makingbritain/content/india-league}}</ref> |

|||

Russell's first mathematical work, ''An Essay on the Foundations of Geometry'', was published in [[1897]]. This work was heavily influenced by [[Immanuel Kant]]. Russell soon realised that the conception it laid out would have made [[Albert Einstein]]'s schema of [[space-time]] impossible, which he understood to be superior to his own system. Thenceforth, he rejected the entire [[Kantian]] program as it related to mathematics and [[geometry]], and he maintained that his own earliest work on the subject was nearly without value. |

|||

===Second World War=== |

|||

Interested in the definition of [[number]], Russell studied the work of [[George Boole]], [[Georg Cantor]], and [[Augustus de Morgan]], and he became convinced that the foundations of mathematics were tied to logic. In [[1900]] he attended the first [[International Congress of Philosophy]] in [[Paris]] where he became familiar with the work of the Italian mathematician, [[Giuseppe Peano]]. He mastered Peano's new symbolism and his set of [[axioms]] for [[arithmetic]]. Peano was able to define logically all of the terms of these axioms with the exception of ''0'', ''number'', ''successor'', and the singular term, ''the''. Russell took it upon himself to find logical definitions for each of these. He eventually discovered that [[Gottlob Frege]] had independently arrived at equivalent definitions for ''0'', ''successor'', and ''number'', and the definition of number is now usually referred to as the Frege-Russell definition. It was largely Russell who brought Frege to the attention of the English-speaking world. |

|||

[[Bertrand Russell's political views|Russell's political views]] changed over time, mostly about war. He opposed rearmament against [[Nazi Germany]]. In 1937, he wrote in a personal letter: "If the Germans succeed in sending an invading army to England we should do best to treat them as visitors, give them quarters and invite the commander and chief to dine with the prime minister."<ref>{{Cite web |date=19 February 2014 |title=Museum Of Tolerance Acquires Bertrand Russell's Nazi Appeasement Letter |url=http://losangeles.cbslocal.com/2014/02/19/museum-of-tolerance-acquires-bertrand-russells-nazi-appeasement-letter/ |access-date=29 March 2017 |website=Losangeles.cbslocal.com}}</ref> In 1940, he changed his [[appeasement]] view that avoiding a full-scale world war was more important than defeating Hitler. He concluded that Adolf Hitler taking over all of Europe would be a permanent threat to democracy. In 1943, he adopted a stance toward large-scale warfare called "relative political pacifism": "War was always a great evil, but in some particularly extreme circumstances, it may be the lesser of two evils."<ref>Russell, Bertrand, "The Future of Pacifism", The American Scholar, (1943) 13: 7–13.</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Bertrand Russell |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SlMrmmrNuEoC |title=Autobiography |publisher=Psychology Press |year=1998 |isbn=978-0-415-18985-9 |chapter=12: Later Years of Telegraph House |quote=I found the Nazis utterly revolting – cruel, bigoted, and stupid. Morally and intellectually they were alike odious to me. Although I clung to my pacifist convictions, I did so with increasing difficulty. When, in 1940, England was threatened with invasion, I realised that, throughout the First War, I had never seriously envisaged the possibility of utter defeat. I found this possibility unbearable, and at last consciously and definitely decided that I must support what was necessary for victory in the Second War, however difficult victory might be to achieve, and however painful in its consequences}}</ref> |

|||