| Ahalya | |

|---|---|

| Devanagari | अहल्या |

In Hinduism, Ahalya (Sanskrit: अहल्या, IAST Ahalyā, Tamil: Akalikai, Thai: อหลยา, Malay: Dewi Indera), also known as Ahilya, is the wife of the sage Gautama, primarily known for her sexual encounter with the god-king Indra, the resultant curse by her husband and her subsequent liberation by Rama – an avatar of the god Vishnu. Due to the unflinching acceptance of the curse and loyalty to her husband, Ahalya is extolled as the first of the panchakanya ("five virgins") – archetypal chaste women – the recital of whose names is believed to dispel sin. Contrarily, others condemn her as an adulteress and a fallen woman.

Created by the god Brahma as the most beautiful woman in the universe, Ahalya was married to the much older Gautama. In the earliest narrative, when Indra comes disguised as her husband, Ahalya sees through his disguise but still accepts his advances. Later sources however, often absolve her of all guilt, describing how she falls prey to his trickery, or is raped. In all narratives, Ahalya as well as her lover Indra, are cursed by Gautama. While the curse varies from text to text, almost all versions describe Rama as the eventual agent of her liberation. Although early texts describe how Ahalya must atone by undergoing severe penance while remaining invisible to the world and how she is purified by offering Rama hospitality, in the popular retelling developed over time, Ahalya is cursed to become a stone and regains her human form after she is brushed by Rama's foot.

While the Brahmanas (9th to 6th centuries BCE) are the earliest scriptures to hint at Ahalya's relationship with Indra, the 5th to 4th century BCE Hindu epic Ramayana – whose hero is Rama – is the first to tell the story in detail. Mediaeval story-tellers often focus on Ahalya's deliverance by Rama, which is seen as proof of the saving grace of God. While ancient stories are Rama-centred, modern writers tell the story from Ahalya's perspective. Her story has been retold numerous times in the scriptures and lives on in modern age poetry and short stories as well as in dance and drama.

Name and development

The word "Ahalya" is broken up as "a" (a prefix indicating negation) and "halya".[1] Sanskrit dictionaries define the meaning of halya as arable, ploughed or ploughing and ugliness or deformity.[2][3] In the Uttar Kanda book of the Ramayana, the god Brahma explains the meaning of the Sanskrit word "Ahalya" as "one without the reprehension of ugliness", or "one with an impeccable beauty"; while telling Indra how he created Ahalya by taking the special beauty of all creation and expressing it in every part of her body.[4] Some Sanskrit dictionaries translate Ahalya as "unploughed",[1][5] however, some recent authors – arguing that sexual intercourse is often likened to the ploughing of a field – interpret the word to mean "one who is not ploughed", i.e. a virgin; or "one who should not be ploughed", i.e. a motherly figure and in the context of the character Ahalya, someone beyond Indra's reach.[6][7][8] As per the literal meaning of her name "unploughed", Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941) interprets Ahalya as a symbol of stone-like, infertile land that was made cultivable by Rama.[9] Delhi University professor Bharati Jhaveri concurs with Tagore interpreting Ahalya as unploughed land, on the basis of the tribal Bhil Ramayana.[10]

Ahalya's sexual encounter with Indra as well as the resultant curse and redemption form the central narrative of Ahalya's story in all scriptural texts describing her life.[11] The Brahmanas (9th to 6th centuries BCE) are the oldest scriptures to reveal the relationship between Ahalya and Indra but the Bala Kanda book of the Ramayana – an 5th to 4th century BCE epic which narrates Rama's life – is the first to explicitly mention her extra-marital affair. While the Bala Kanda mentions Ahalya's conscious decision to have sex, the Uttar Kanda of the Ramayana (regarded as a later addition to the epic), along with the Puranas (compiled between 4th to 16th century CE), absolve her of all guilt. They alternately state that the jealous Indra tricks Ahalya into having sex by disguising himself as Gautama or that he rapes her.[6]

Despite the fact that Ahalya is cursed to endure several penances to expiate her sin in the Bala Kanda, the sage Vishwamitra – Rama's guru – still describes her as a goddess-like and illustrious woman,[12] repeatedly calling her mahabhaga (commonly split as "maha + bhaga", translated as "most illustrious and highly distinguished").[6][13] This interpretation contrasts with that of Rambhadracharya, for whom the word mahabhaga in the context of Ahalya's story means "extremely unfortunate" (split as "maha + abhaga").[14] When Rama first meets her, the Bala Kanda describes Ahalya as glowing due to the intensity of her ascetic devotion, but hidden from the world like the sun obscured by dark clouds, the light of a full moon hidden by mist or a blazing flame masked by smoke.[12] Ahalya is purified by offering Rama hospitality.

Although opinions differ on whether the Bala Kanda narrative of Ahalya refers to the divinity of Rama, later sources assert Rama's divine status, portraying Ahalya as a condemned woman rescued by God.[15] In the popular retelling of the legend in later works as well as in theatre and electronic media, Ahalya is turned to stone by a curse and only returns to her human form after she is brushed by Rama's foot.[6][16] It has been argued that this later version of the tale is result of a "male backlash" and patriarchal myth-making that condemns her as a non-entity devoid of emotions, self-respect and societal status.[6] Tulsidas's 16th century Ramacharitamanasa and other Bhakti era poets use the episode as an archetypal example to demonstrate God's saving grace. The main theme of such narratives is her deliverance by Rama, which is seen as proof of his compassion.[17]

While historic narratives are Rama-centric, contemporary writers make Ahalya the focus of the story.[18] Ahalya is examined in new light by several modern writers - most commonly through the short story genre or through poetry in various Indian languages.[19][20] They try to imagine Ahalya's life after the curse and redemption, a denouement which remains undisclosed in the ancient scriptures. Alternatively, such writers try to imagine Ahalya's tale occurring in the modern era, rather than in its traditional ancient setting.[20] While Ahalya is a minor character in all ancient sources – "stigmatized and despised by those around her" for violating gender norms, modern Indian writers have elevated her to the status of an epic heroine, who is no longer just an insignificant figure in the saga of Rama.[19][21] However, in modern Ramayana adaptations where Rama is the hero, the redemption of Ahalya is still just a supernatural incident in his life.

Ahalya's tale is retold numerous times in stage enactments as well as film and television productions.[6][22] Her tale is a popular motif in the Mahari temple dancer tradition of Orissa.[23] Other performing arts used to tell her story include the dance Mohiniyattam of Kerala,[24][25] the Ahalyamoksham play by Kunchan Nambiar in the Ottamthullal art form[26] and the padya-natakam drama Sati Ahalya from Andhra Pradesh.[27]

A similar tale of divine seduction appears in Greek mythology, where the god-king Zeus – a god akin to Indra – seduces Alcmene in the form of her husband resulting in the birth of the legendary hero Heracles. Like Ahalya, Alcmene falls victim to Zeus's trickery in some versions or knows his true identity and still goes ahead with the intercourse in others. The major distinction in the tales is that the raison-d'etre of Alcmene's seduction is the justification of Heracles's divine parentage and thus she is never condemned as an adulteress or punished. In contrast, Ahalya's encounter is regarded purely erotic, not resulting to procreation and thus Ahalya faces the ire of the scriptures.[28][29]

Creation and marriage

Ahalya is often described as an ayonijasambhava – one not born of a woman.[6] The Bala Kanda of the Ramayana mentions how the Creator moulds her "with great effort out of pure creative energy".[6][12] The Brahma Purana (400-1300 CE) as well as the Vishnudharmottara Purana (400–500) also records her creation by Brahma.[11] The Mahari dance tradition tells that Brahma created Ahalya – as the most beautiful woman – out of water to break the pride of Urvashi, the foremost of the celestial nymphs.[23] By contrast, the Bhagavata Purana (500–1000) and Harivamsa (dated between the 1st and the 3rd century) regard Ahalya as a princess of the Puru dynasty, the daughter of King Mudgala and sister of King Divodasa.[30][31]

In the Uttara Kanda book of the Ramayana, Brahma crafts Ahalya as the most beautiful woman in the world and then places her in the care of the sage Gautama until she reaches puberty. When that time arrives, the sage returns Ahalya to Brahma, who - impressed by the sage's sexual restraint - bestows her upon him. Meanwhile, Indra who believes that the best women are meant for him, resents Ahalya's marriage to the forest-dwelling ascetic.[32][33]

The Brahma Purana gives a similar account of Ahalya's birth and initial custody with Gautama. It further tells that the question of Ahalya's marriage was determined through an open contest. Brahma declares that the first being to go around the three worlds (heaven, earth, and the underworld) will win Ahalya. Indra uses his magical powers to complete the challenge, finally reaching Brahma to demand the hand of Ahalya. However, the divine sage Narada mentions to Brahma that Gautama went around the three worlds before Indra, explaining that one day as part of his daily puja (ritual offering), Gautama circumambulated the wish-bearing cow Surabhi while she gave birth, which - according to the Vedas - made the cow equal to three worlds. Brahma agrees and Ahalya is married to Gautama, leaving Indra envious and infuriated.[34] A similar shorter version of Ahalya's early life also appears in the Padma Purana (700-1200).[35]

In all versions of the tale, after her marriage with Gautama, Ahalya settles into his ashram (hermitage), which generally becomes the site of her epic curse. The Ramayana records that Gautama's ashram is located in a forest (Mithila-upavana) near Mithila, where the couple practise ascetics together for several years.[11][36] In other scriptures, the ashram is usually near the river bank. The Brahma Purana says that it is near river Godavari, while Skanda Purana (700–1200) places it near river Narmada. The Padma Purana and Brahma Vaivarta Purana (800-1100) describe the ashram to be near the holy city of Pushkar.[11]

Encounter with Indra: Curse and redemption

Brahmanas

The Brahmanas (9th to 6th centuries BCE) are the oldest scriptures to reveal the relationship between Ahalya and Indra in the so-called "subrahmanya formula", a chant used by Vedic priests at the beginning of a sacrifice to invoke the main participants: Indra, the gods and the Brahmins (priesthood).[37][38] The Jaiminiya Brahmana and the Sadvimsha Brahmana from the Samaveda tradition, the Shatapatha Brahmana and the Taittiriya Brahmana from the Yajurveda tradition, and two Shrautasutras (Latyayana and Drahyayana)[38] invoke Indra, the "lover of Ahalya ... O Kaushika, Brahman (Brahmin), who calls himself Gautama".[37] The Samaveda tradition identifies her as Maitreyi, who the commentator Sayana explains is "the daughter of the god Mitra".[38]

In the subrahmanya formula, Ahalya does not have a husband. In the Sadvimsha Brahmana, it is not explicitly stated that Ahalya has a husband, although Kaushika is present in the story and his relationship to her can be inferred through Indra's adoption of the Brahmin's form to "visit" Ahalya. Renate Söhnen-Thieme - Research Associate at the School of Oriental and African Studies - feels that the Kaushika of the Sadvismha Brahmana is the same individual described as cursing Indra in the 5th to 4th century BCE epic Mahabharata (discussed below).[38][39] The Shatapatha Brahmana's commentator, Kumarila Bhatta, reasons that the Ahalya-Indra myth is an allegory for the Sun (Indra) taking away the shade of night (Ahalya).[31]

The American scholar Edward Washburn Hopkins interpreted the Ahalya of the subrahmanya formula not as a woman, but as "yet unploughed land", which Indra makes fertile.[28]

Epics: Ramayana and Mahabharata

- Ramayana

The Bala Kanda of the Ramayana is the earliest text to describe the encounter between Ahalya and Indra in detail. Enamoured by Ahalya's beauty and learning of her husband's absence, Indra comes to the ashram disguised as Gautama and requests sexual intercourse with Ahalya, praising her as a shapely and slim-waisted woman. She sees through his disguise, but consents due to "curiosity". According to another interpretation, Ahalya's pride in her beauty compels her to make this decision.[40] Having satiated his sexual lust, Ahalya requests Indra – her "lover" and "best of gods" – to flee and protect both of them from Gautama's wrath. However, Gautama spots Indra, who is still in disguise, and curses him to lose his testicles. Gautama then curses Ahalya to remain invisible to all beings for thousands of years, to fast by subsisting only on air, to suffer and sleep in ashes, and to be tormented by guilt. Nevertheless, he assures her that her sin will be expiated once she extends her hospitality to Rama, who will then visit the ashram. Thereafter, Gautama abandons the ashram and goes to the Himalayas to do penance.[6][36]

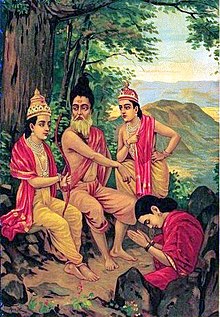

The Bala Kanda mentions that Ayodhyan princes Rama and his brother Lakshmana and their guru Vishwamitra pass Gautama's desolate ashram in the forest while travelling to King Janaka's court in Mithila. As they near the ashram, Vishwamitra recounts the tale of Ahalya's curse and instructs Rama to save Ahalya. Following Vishwamitra, the princes enter the ashram to see a glowing Ahalya, who up till then has been hidden from the universe. At the behest of Vishwamitra, Rama considers Ahalya guiltless and pure. He and Lakshamana touch her feet giving obeisance, an act that restores her status in society. She greets them, recalling Gautama's words that Rama would be her redemption. She extends her warmest hospitality, making a "welcome offering" of forest fruits and washing their feet as per the rites of that era. Then, the gods and other celestial beings shower Rama and Ahalya with flowers and bow to Ahalya, who was now purified through the penance she had practised in solitude. Gautama returns to his ashram and accepts her back.[6][12]

By contrast, the Uttara Kanda of the Ramayana recasts the tale as Ahalya's rape by Indra. Indra is cursed to suffer imprisonment, loss of his peace of mind and to bear half the sin of every rape ever committed, while the innocent Ahalya is cursed to lose her unique quality of being the most beautiful woman, as this was the cause of Indra's seduction. Ahalya claims her innocence (this part is not found in all manuscripts), but Gautama agrees to accept her back only when she is sanctified by offering Rama hospitality.[6][33][41]

- Mahabharata

In the Mahabharata, there are three allusions to the Ahalya episode; however, the Ramopakhyana – the condensed narrative of the Ramayana in the Mahabharata – does not mention Ahalya's violation and her redemption by Rama.[42] In one instance, Indra is said to be have been cursed to have a golden beard as he seduces Ahalya, while a curse by Kaushika is described as the reason for his castration. In another instance, where details of the sexual adventure are absent, an agitated Gautama orders his son Chirakari to behead his "polluted" mother and leaves the ashram. However, Chirakari does not follow the order at once and, as is his habit, thinks it over for a long time, before arriving at the conclusion that Ahalya is innocent. Gautama returns and repents his hasty decision, realising that Indra is the guilty party.[6][43] In another allusion, Nahusha reminds Indra's preceptor Brihaspati how Indra "violated" the "renowned" rishi-patni (wife of a sage) Ahalya. Söhnen-Thieme considers the words "violated" and "renowned" indicate that Ahalya is not considered an adulteress here.[41]

Puranas

The Puranas bring themes echoed in later works like the unsuspecting Ahalya fooled by Indra's devious disguise as Gautama in Gautama's absence, Ahalya's defence plea, the innocent Ahalya cursed to be turned into stone, the touch of Rama's feet turning the petrified Ahalya into a sanctified beautiful maiden, Indra escaping as a cat and Indra cursed to be castrated and/or to carry his shame in the form of a thousand vulvae on his body for all to see, which are later turned into a thousand eyes.[11]

The Brahma Purana is a rare exception where Rama is dropped from the narrative and the greatness of the Gautami (Godavari) river illustrated. Ahalya is cursed to become a dried up stream, but pleads her innocence and even produces servants – who were deceived by Indra's disguise – as witnesses. Gautama softens the curse on his "faithful wife" and she is redeemed when she joins the Gautami river as a stream.[6][34][44]

The Padma Purana tells that a beguiled Ahalya declares herself blameless, but Gautama considers her impure and curses her to be reduced to a mere skeleton of skin and bones. He decrees that she will regain her beautiful form when Rama will laugh at her, seeing her so afflicted – dried out (a reminder of the dried stream motif), without a body (the Ramayana curse) and lying on the path (an attribute often used to describe a stone). When Rama comes, he proclaims her innocence and Indra's guilt, whereupon Ahalya returns to her heavenly abode, where she still dwells with Gautama.[35][45]

According to the Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Indra becomes infatuated with Ahalya's beauty when he sees her come to bathe in the Svarnadi (heavenly river), near Pushkar. Assuming Gautama's form, Indra has sex with her, until they sink to the river bed in exhaustion. Gautama interrupts them and curses both of them. Ahalya, though innocent, is turned to stone for sixty thousand years and destined only to be redeemed by Rama's touch. Ahalya accepts the verdict without debate. Another version in the same Purana focuses more on the issue of how the chaste Ahalya was seduced by Indra. In this version, Indra approaches Ahalya on the banks of the Mandakini river – near Pushkar – in his own form to ask for a sexual favour, which is flatly refused by Ahalya. Then, Indra poses as Gautama and fulfils his objective. Upon discovery of the deceit, Ahalyas pleads innocence to Gautama, who acknowledges that her mind is pure and she has kept the vow of chastity and fidelity, but the presence of another man's seed in her body has defiled it. Gautama orders her to go to the forest and become a stone until rescued by the touch of Rama's feet.[46][47]

In the Skanda Purana, though initially deluded by Indra's disguise, Ahalya smells his celestial fragrance and realises her folly, when he embraces and kisses her, and "so forth" (probably indicating the sexual act). Threatening Indra with a curse, she compels him to reveal his true form. When Gautama arrives home, she tells him the whole truth, but is cursed by Gautama to become a stone, as she acted as a rolling stone unable to recognise the difference between Indra's and Gautama's gestures and movements. The touch of Rama's feet is prophesied to be her saviour.[48]

Most of the fifth chapter of the Bala Kanda Book of the Adhyatma Ramayana (embedded in the Brahmanda Purana, c. 14th century) is dedicated to the Ahalya episode. Like most other versions of the story, Ahalya is turned into stone and advised to engross herself in meditation of Rama, the Supreme Lord. When Rama touches the stone with his foot on Vishwamitra's advice, Ahalya rises as a beautiful maiden and sings a long panegyric dedicated to Rama. Ahalya describes his iconographic form and exalts him as an avatar of Vishnu and source of the universe to whom many divinities pay their respects. After worshipping him, she returns to Gautama. At the end of the narrative Ahalya's hymn is prescribed as an ideal benediction for a devotee to gain Rama's favour.[49]

Besides these scriptural examples, the story also appears in the Matsya Purana (200-600), the Ganesha Purana (1100–1400), the Harivamsa, the Linga Purana, the Narasimha Purana (5th century) and the Markandeya Purana (200-600), of which the last uses the tale to denigrate Indra and glorify Vishnu.[31][50]

Non-scriptural Sanskrit works

The Raghuvamsa of Kalidasa (generally dated 4th century) notes that the wife of Gautama (unnamed here) momentarily became the wife of Indra. Without explicitly mentioning the curse, it relates further that she regains her beautiful form again and casts away her stony appearance, due to the grace of the dust on Rama's feet that removes her sins.[51] Gautam Patel credits Kalidasa to be the first one to introduce the petrification motif.[52] Bhavabhuti's 8th century Mahaviracharita also alludes to Ahalya's redemption and in a verbal spat with Parashurama, sage Satananda is depicted to be mocked as son of Ahalya, the adulteress.[53]

The Kathasaritsagara (11th century) tells that Indra arrives undisguised and requests sexual intercourse. As in the earliest account in the Bala Khanda, Ahalya makes a conscious decision to accept the offer. After the act, when Gautama arrives Indra tries to flee as a cat and is cursed to bear the marks of a thousand vulvae. When asked by Gautama about her visitor, Ahalya wittily answers that it was a majjara a word meaning either "cat" or when split as ma-jara, "my lover". Gautama laughs and curses her to be turned into stone, but decrees that she will be released by Rama since she at least spoke the truth.[6][30][54]

The well-known treatise on sexual behaviour, the Kamasutra (300-600) also mentions how lust destroys men, giving the example of Ahalya and Indra.[7] However, it also urges men to seduce women by telling the romantic tales of Ahalya.[55]

The Yoga Vasistha (1000–1400) narrates a tale of two adulterous lovers – queen Ahalya and the Brahmin Indra, which is inspired by the classical Ahalya-Indra tale. Here, Ahalya and Indra fall in love and continue their affair, despite punishments imposed upon them by the king, Ahalya's jealous husband. After death, they reunite in their next birth.[55]

Medieval vernacular versions

Kamban's 12th century Tamil adaptation of the Ramayana – the Ramavataram – portrays Ahalya as deceived by Indra's Gautama disguise and agrees to have sex with him as she has craved affection from her ascetic husband for a long time. However, after some time, she realises that her lover is an imposter but continues to enjoy the dalliance. As in other versions of the tale, the repentant Ahalya is turned to stone, only to be liberated by Rama, and Indra runs away as a cat but is cursed to bear the mark of a thousand vulvae. In this version, Rama does not have to physically touch Ahalya with his foot. The mere touch of dust from his feet is enough to bring Ahalya to life. Kamban's telling is an example of Bhakti-era poets who exalt Rama as the saviour.[56][57]

The Awadhi Ramacharitamanasa drops the narrative of Indra's visit to Ahalya. In this epic Vishvamitra tells Rama that the cursed Ahalya has assumed the form of a rock and is patiently awaiting the dust from Rama's feet.[58] Ahalya tells Rama that Gautama did well in pronouncing a curse on her, and she deems it as the greatest favour, for as a result, she feasted her eyes on Rama which liberated her from her worldly existence.[58] As in the Adhyatma Ramayana, Ahalya lauds Rama as the great Lord served by other divinities, asks for the boon of eternal engrossment in his devotion, and afterwards leaves for her husband's abode.[59] The narrative ends with praise for Rama's compassion.[59] Tulsidas alludes to this episode numerous times in the Ramacharitamanasa while highlighting the significance Rama's benevolence.[60] Commenting on this narrative in the Ramacharitamanasa, Rambhadracharya says that Rama did three things – he destroyed the sin of Ahalya by his sight, he destroyed the curse by the dust of his feet, and he destroyed the affliction by the touch of his feet, evidenced by the use of the Tribhangi (meaning "destroyer of the three") metre in the verses which form Ahalya's pageyric.[61]

In an 18th century Telugu rendition of the tale by the warrior poet Venkata Krishnappa Nayaka of the Madurai Nayak Dynasty, Ahalya is depicted as a romantic adulteress. When Brahma creates Ahalya as the most beautiful being, she falls in love with Indra and longs for him, but her father grants her to Gautama. The lovers continue to meet after Ahalya's marriage. In Gautama's absence, Indra visits Ahalya and flirts with her. At one point, Ahalya receives a visit from Indra's female messenger who mocks husbands who avoid sex by citing excuses such as "Today is not the right day for pleasure." Ahalya protests, saying that whenever Gautama agrees to make love to her, she imagines he is Indra and that a woman should be a stone forgoing all thought of pleasure. That night, when Ahalya longs for conjugal pleasure, Gautama refuses her, saying that she is in not in her fertile period. Agitated, she wishes that Indra was there to satisfy her. Indra understands her wish and takes the form of a rooster who crows to dispatch Gautama for his morning ablutions. Indra comes in Gautama's disguise, but is revealed by his seductive speech. Ahalya makes love to him joyously. When Indra reluctantly leaves, Gautama arrives and curses Ahalya to become a stone, to be later purified by Rama's feet. After she is freed from the curse, Gautama and Ahalya are reconciled and they spend their days in bed, inventing various ways to obtain sexual satisfaction.[62]

The tribal Bhil Ramayana of Gujarat begins with the tale of Ahalya-Gautama-Indra. Ahalya is created from the ashes of the sacrificial fire by the seven seers and gifted to Gautama. The jealous Indra seduces Ahalya with help of the moon-god Chandra, who transforms into a cock and compels Gautama to leave for his morning rituals. In this version, Gautama attacks and imprisons Indra, who is freed when he as the rain god promises to shower rains on crops and the one fourth of all crop is dedicated to Gautama. Here, Ahalya is interpreted as dry and burnt land, eager for the rains by Indra, who is tamed by the wild cyclonic Gautama.[10]

Modern renditions: curse, redemption and thereafter

Ahalya's tale lives on in modern day poetry written by poets like the Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore – in Bengali and English, P. T. Narasimhachar (1940 poetic drama called Ahalya in the Kannada language, which weights pleasure against Dharma – Law or duty)[19] and Sanskrit scholar and poet Chandra Rajan.[6][31]

Early in the 20th century, the old norms were reasserted. Pa. Subramania Mudaliar in his Tamil poem describes Ahalya lecturing Indra on chastity, but Indra's lust compels him to rape her. Gautama turns Ahalya to stone to free her from the trauma. While the Tamil writer Yogiyar portrays an innocent Ahalya, who sleeps with the disguised Indra, overcome with guilt and asking for punishment.[19] Sripada Krishnamurty Sastry's Telugu version of Ramayana, one of the most censored version of the tale, reduces Ahalya's contact with Indra to a handshake.[63]

Other authors reinterpreted the Ahalya legend from a very different perspective, often depicting Ahalya as a rebel and telling the story from her angle.[19] R. K. Narayan (1906–2001) focuses on the psychological details of the story, reusing the old tale of Indra's disguise as Gautama, his flight as a cat and Ahalya's being turned to stone.[64] The theme of adulterous love is explored in Vishram Bedekar's musical Marathi play Brahma Kumari (1933) as the Malayalam works of P. V. Ramavarier (1941) and M. Parvati Amma (1948).[19] Tamil short story writer Ku Pa Rajagopalan (1902–44)'s Ahalya also secretly longs for Indra and enjoys dalliance with him.[19] Dr. Pratibha Ray's Oriya novel Mahamoha (1998) deals with Ahalya's tale.

Pudhumaipithan's Tamil story Sapavimocanam (1943, "Deliverance from the Curse") and K. B. Sreedevi's Malayalam language work (1990) translated as "Woman of Stone" focus on Rama's "double standards" and are written from a feminist point of view. They ask if Rama frees Ahalya from being cursed for adultery, why does he punish his wife Sita over false accusations of adultery with her kidnapper Ravana?[18][65] While in Pudhumaipithan's tale, Ahalya turns back into stone after hearing that Sita had to undergo a trial by fire to prove her chastity, Sreedevi portrays her turning into stone upon learning that Sita is banished from the kingdom on charges of adultery even after proving her chastity by the trail by fire. Pudhumaipithan also narrates how after the redemption, Ahalya suffers from "post-trauma repetition syndrome", re-experiencing Indra's seduction and Gautama's fury again and again, as well as still suffering the ire of a conservative society, which rejects her.[18][19] Gautama also suffers from self-recrimination at his hasty decision to curse Ahalya.[18] In another story called Akalyai by Pudhumaipithan, Gautama forgives Ahalya and Indra.[19]

S.Sivasekaram's 1980 Tamil poem Ahalikai questions Ahalya's life with regard to the stone metaphor that appears in the story; she marries a husband who is no more interested in her than a stone and briefly tastes a more exciting life with Indra, only to end up cursed to become a stone with no life herself. The poet asks if it was better for Ahalya to remain physically a stone and maintain her dignity rather than return to a stony marriage.[18] Tamil poet Na. Pichamurthy (1900–76)'s Uyir maga ("Life-woman") presents Ahalya as an allegorical representation of life, with Gautama as the mind and Indra pleasure. The "Marxist critic" Gnani's Ahalya from his poem Kallihai is the oppressed class, Rama being an ideal future without exploitation. Gautama and Indra represent feudalism and capitalism.[19] The character of Ahalya played by Kamala Kotnis in the 1949 movie Sati Ahalya ("chaste Ahalya") was described to be still relevant as it portrayed the predicament of a stained woman.[66]

Love, sex and desire become important elements of the plot in Sant Singh Sekhon's Punjabi play Kalakar (1945), which places the epic drama in the modern age. It depicts Ahalya as a free-spirited woman, who dares to be painted nude by the art Professor Gautama's pupil Inder (Indra) and yet defends her decision to her husband.[19][67] N. S. Madhavan's Malayalam story (April 2006) retells Ahalya's tale in a modern setting, where Ahalya – accused of adultery – is beaten by her husband, leaving her in a coma, but the neurologist Rama revives her from her sleep.[18]

Children

The Ramayana mentions Ahalya's son Shatananda, who is the family priest and preceptor of King Janaka of Mithila. In this version of the story, Shatananda asks Vishwamitra anxiously about the well-being of his mother.[68][69] By contrast, the Mahabharata mentions two sons: Sharadvan who is born with arrows in his hand, and Chirakari, who ponders on all his actions so much that he delays them. Besides these, an unnamed daughter is also alluded to in the narrative. The Vamana Purana mentions three daughters: Jaya, Jayanti and Aparaji.[68]

Another legend, generally told in Indian folk tales, tells that Aruna – the charioteer of the sun-god Surya – once became a woman named Aruni and entered an assembly of celestial nymphs, where no man except Indra was allowed. Indra fell in love with Aruni and fathered a son named Vali. The next day, at Surya's request, Aruna again assumed his female form, with whom Surya begot Sugriva. Both children were handed over to Ahalya for rearing, but Gautama cursed them to become monkeys as he did not like them.[30][70][71] In the Thai version of the Ramayana - the Ramakien, Vali and Sugriva are described as Ahalya's children born from her liaisons with Indra and Surya. She passes them off as sons of Gautama; however, her daughter Anjani by Gautama, reveals her mother's secret to her father. He consequently drives the brothers away and curses them to become monkeys. Enraged, Ahalya curses Anjani to become a monkey too. Anjani later gives birth to Hanuman, the monkey-god and helper of Rama.[72] Similar tales are also found in the Malay adaptation Hikayat Seri Rama, Punjabi and Gujarati folk tales, however Anjani is cursed by Gautama in these versions, generally for aiding Indra and her mother in concealing the secret.[73]

Some Tamil people castes trace their ancestry to Ahalya and Indra's liaison. The names of Ahalya's children are namesakes of the castes. Gautama finds the three boys and names them according to their behaviour: Agamudayar (derived from "brave" – who confronts Gautama), Maravar (derived from "tree" – who climbs a tree) and Kallar (derived from "thief" or "rock" – who hides like a thief behind a large rock). Sometimes, a fourth child called Vellala is added in some versions. Another variant replaces the theme of the liaison with the theme of Ahalya obtaining the children as a boon from Indra as result of her penance and worship to the god, legitimizing the birth of the children.[74]

Assessment and remembrance

A well-known verse cited about Ahalya runs:[5][75]

Sanskrit Transliteration

ahalyā draupadī sītā tārā mandodarī tathā ।

pañcakanyāḥ smarennityaṃ mahāpātakanāśinīḥ ॥

English translation

Ahalya, Draupadi, Sita, Tara and Mandodari

One should forever remember the five virgins who are the destroyer of great sins

Note:A variant of this prayer replaces Sita with Kunti.[6][16][76]

Orthodox Hindus, especially Hindu wives, remember the panchakanya – the five virgins or maidens – in this daily morning prayer.[75][77][78] One view considers them as "exemplary chaste women"[78] or mahasatis ("great chaste wives") as per the Mahari dance tradition,[23] and worthy as an ideal for "displaying some outstanding quality".[75] In this view, Ahalya is considered as the "epitome of the chaste wife, unjustly accused of adultery", while her "proverbial loyalty to her husband" makes her venerable.[78] Due to the "nobility of her character, her extraordinary beauty and that she is chronologically the first kanya", Ahalya is often regarded as the head of the panchkanya.[6] In the Devi-Bhagavata Purana, Ahalya is enlisted in a list of secondary goddesses, who are "auspicious, glorious and much praiseworthy", along Tara, Mandodari as well as some of the pancha-satis ("five satis or chaste wives") Arundhati, Damayanti et al.[79]

Another view states that none of the panchakanya is considered an ideal woman who could be emulated.[76] Bhattacharya, author of Panch-Kanya: The Five Virgins of Indian Epics contrasts the panchakanya with the five satis enlisted in another traditional prayer: Sati, Sita, Savitri, Damayanti and Arundhati, and rhetorically asks: "Are then Ahalya, Draupadi, Kunti, Tara, and Mandodari not chaste wives because each has "known" a man, or more than one, other than her husband?"[32] Social reformer Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay is perplexed by the inclusion of Ahalya and Tara in the panchakanya, both of whose sexual behaviours were not only considered to be not ideal, but also were deemed as "unethical" by later social norms.[75] Although Ahalya's "moral slip" has blemished her and denied her the high status and reverence accorded to women like Sita and Savitri, this very action has made her immortal in legend.[76]

Bhattacharya says Ahalya is unique in her daring act and its dire consequences. For Bhattacharya, Ahalya is the eternal woman who responds to her inner urges and the advances of the divine ruler, a direct contrast to her ascetic husband, who did not satisfy her carnal desire. The author regards Ahalya as an independent woman who makes her own decisions, takes risks, and is driven by curiosity to experiment with the extraordinary and then accept the curse pronounced on her by patriarchal society.[6] It is this "unflinching acceptance" of the curse that makes the Ramayana praise her and venerate her.[80] V.R. Devika, author of Ahalya : Scarlet letter, asks based on Ahalya's example: "So is it right to condemn adultery and physical encounters as modern afflictions and against our (Indian/Hindu) culture? Or do we learn from Ahalya who made a conscious choice to fulfill her need and yet has been extolled?"[16]

Like Bhattacharya, Kelkar - author of Subordination of woman: a new perspective - feels that Ahalya was made venerable due to her acceptance of the norms of conduct for women and as she ungrudgingly accepted the curse while acknowledging that she needed to be punished. However, Kelkar adds another reason - for making Ahalya immortal in scripture - could be that Ahalya's punishment acts as a warning and deterrent to women.[81] Patriarchal society always condemns Ahalya as a fallen woman or adulteress.[80] Jaya Srinivasan, whose discourses on tales from the epics says that though Ahalya's action was "unpardonable", she was redeemed by the divine touch of dust particles from Rama's feet. Jaya adds that Ahalya's actions and the resultant curse are a warning that such immoral behaviour leads to doom, although sincere penitence and complete surrender to God can erase the gravest sins.[82] In Hindu Tamil weddings in India and Sri Lanka, Ahalya appears as a symbolic black grinding stone, which the bride touches with her foot while promising not to be like Ahalya, the bride is also shown the star associated with the chaste Arundhati, who should be her ideal.[83][84]

The right-wing Hindu women's organization Rashtra Sevika Samiti considers Ahalya as the symbol of "Hindu woman's (and Hindu society's) rape by the outsider", especially the British colonisers and Muslim invaders, but also Hindu men.[85] The feminist writer Tarabai Shinde (1850–1910) writes that the scriptures are responsible for promoting immoral ways, where the gods like Indra exploit chaste wives like Ahalya and then why is so much importance given to pativrata dhrama – devotion and fidelity to the husband as the ultimate duty of a wife?[86]

The place where Ahalya practised penance and was redeemed, has been celebrated in scriptures as a sacred place called Ahalya-tirtha. A tirtha is a sacred place with a water body, where pilgrims generally bathe to purify themselves. The location of the Ahalya-tirtha is disputed, according to some scriptures it is on river Godavari, while some place it on river Narmada. An Ahalya-tirtha is located near the Ahalyeshvara temple in Bhalod on the banks of the Narmada. Another Ahalya-tirtha is located in Darbhanga district, Bihar.[87][88] The Ahilya Asthan temple in Ahalya-gram ("Ahalya's village") in the same district is dedicated to Ahalya.[89] The Matsya Purana and the Kurma Purana prescribe Ahalya's worship at Ahalya-tirtha on the love-god Kamadeva's day in the Hindu month of Chaitra to be like the love-god and attract women. Bathing in the tirtha is said to bring celestial pleasure with the celestial nymphs.[90]

Footnotes

- ^ a b Wilson, H.H. (2008) [1819]. Wilson Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Universität zu Köln. p. 100. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ Apte, Vaman S (May 1, 2011). The Student's Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 637. ISBN 978-8120800458. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ Monier-Williams, Monier (2008) [1899]. Monier Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Universität zu Köln. p. 1293. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ "Triṃśaḥ Sargaḥ". Śrīmadvālmīkīya Rāmāyaṇa (in Hindi). Vol. 2. Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh, India: Gita Press. 1998. pp. 681–682.

tato mayā rūpaguṇairahalyā strī vinirmitā । halaṃ nāmeha vairūpyaṃ halyaṃ tatprabhavaṃ bhavet ॥ 7.30.22 ॥ yasyā na vidyate halyaṃ tenāhalyeti viśrutā । ahalyetyeva ca mayā tasyā nāma prakīrtitam ॥ 7.30.23 ॥

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_chapter=ignored (|trans-chapter=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Apte, Vaman S (May 1, 2011). The Student's Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 73. ISBN 978-8120800458. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Bhattacharya, Pradip (March–April 2004). "Five Holy Virgins, Five Sacred Myths: A Quest for Meaning (Part I)" (PDF). Manushi (141): 4–7.

- ^ a b Doniger p. 89

- ^ Feller p. 146

- ^ Datta, Nilanjana Sikdar (2001). "Valmiki-Ramayana – An approach by Rabindranath Tagore". In Dodiya, Jaydipsinh (ed.). Critical perspectives on the Rāmāyaṇa. Sarup & Sons. p. 52. ISBN 81-7625-244-1.

- ^ a b Jhaveri, Bharati (2001). "Nature and environment in Ramayana of Bhils of North Gujarat". In Dodiya, Jaydipsinh (ed.). Critical perspectives on the Rāmāyaṇa. Sarup & Sons. pp. 149–52. ISBN 81-7625-244-1.

- ^ a b c d e Söhnen-Thieme pp.40–1

- ^ a b c d Goldman pp. 217–8

- ^

- Wilson, H.H. (2008) [1819]. Wilson Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Universität zu Köln. p. 650. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- Monier-Williams, Monier (2008) [1899]. Monier Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Universität zu Köln. p. 798. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- Macdonell, Arthur Anthony (2008) [1929]. A practical Sanskrit dictionary with transliteration, accentuation, and etymological analysis throughout. Universität zu Köln. p. 221. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ Rambhadracharya 2006, p.36: "... महाभागां माने इसका सीधा सा उत्तर है, यदि आप कहें कि महाभागां माने महाभाग्यशालिनी, तो उसको तारने की क्या आवश्यकता है, तब क्यों तारा जाए। तो कहा महाभागां, अरे, वहाँ खण्ड करो – महा अभागां, ये बहुत दुर्भाग्यशालिनी महिला है – महत् अभागं यस्याः सा, जिसका बहुत बड़ा अभाग्य है ..." ("... mahābhāgāṃ means – it's a straightforward answer, if one says that mahābhāgāṃ means highly fortunate, then what is the need to liberate her, why should she be liberated? Then, it was said, mahābhāgāṃ – decompose it as mahā abhāgām, she is an extremely unfortunate lady – mahat abhāgaṃ yasyāḥ sā, whose misfortune is very extreme ...")

- ^

- Goldman p. 45: "The Bala Kanda episode in which Rama releases Ahalya...in hands of Tulsi Das...and other poets of the bhakti movement becomes the archetypal demonstration of the lord's saving grace-is in Valmiki handled with no reference to the divinity of the hero"

- Rambhadracharya 2006, pp. 35–36: The author states that the use of the word taaraya (IAST tāraya, "liberate") by Valmiki in the verse 1.49.12 (spoken by Vishvamitra to Rama) of the Ahalya narrative implies the divinity of Rama, since it is only God that can liberate and not a common man.

- ^ a b c Devika, V.R. (October 29, 2006). "Women of substance: Ahalya: Scarlet letter". The Week. 24 (48): 52.

- ^ Goldman p. 45

- ^ a b c d e f Richman pp. 113–4. The translations of all these works are present in Richman pp. 141–173

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Das, Sisir Kumar (2006). "Epic heroines – Ahalya". A History of Indian Literature: 1911–1956:Struggle for Freedom : Triumph and Tragedy. A History of Indian Literature. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 133–5. ISBN 81-7201-798-7.

- ^ a b Richman p. 24

- ^ Richman pp. 27, 111

- ^ GUDIPOODI SRIHARI (30 May 2008). "Story of five archetypes". The Hindu. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

{{cite news}}:|archive-url=is malformed: liveweb (help) - ^ a b c "FIVE TRAGIC HEROINES OF ODISSI DANCE-DRAMA: THE PANCHA-KANYA THEME IN MAHARI "NRITYA"". Journal of South Asian Literature: FEMININE SENSIBILITY AND CHARACTERIZATION IN SOUTH ASIAN LITERATURE. 12 (3/4). Asian Studies Center, Michigan State University: 25–29. SPRING-SUMMER 1977. JSTOR 40872150.

{{cite journal}}:|first=missing|last=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Ramaswamy, Ram Kumar (July 18, 2011). "I want to spread joy through dance: Gopika Varma". Deccan Cronicle. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

{{cite news}}:|archive-url=is malformed: liveweb (help) - ^ K. Santhosh (6 February 2004). "Ahalya's tale retold". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 26 Jun 2009. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Sharma, V. S. (2000). Kunchan Nampyar. Makers of Indian Literature. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 38, 40. ISBN 81-260-0935-7.

- ^ P. Ram Mohan. "Week-long drama festivities end". The Hindu. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

{{cite news}}:|archive-url=is malformed: liveweb (help) - ^ a b Söhnen, Renate (1991). "Indra and Women". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 54 (1). Cambridge University Press on behalf of School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London: 68–74. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00009617. JSTOR 617314.

- ^ Doniger pp. 124–5

- ^ a b c Mani p. 17

- ^ a b c d Garg, Ganga Ram (1992). Encyclopaedia of the Hindu world: A-Aj. Vol. 1. South Asia Books. pp. 235–6. ISBN 81-7022-374-1.

- ^ a b Bhattacharya, Pradip (2000). "PANCHAKANYA: Women of Substance". Journal of South Asian Literature: Miscellany. 35 (1/2). Asian Studies Center, Michigan State University: 13–56.

- ^ a b Doniger pp. 89–90

- ^ a b Söhnen-Thieme pp. 51–3

- ^ a b Söhnen-Thieme pp. 54–5

- ^ a b Goldman pp. 215–6

- ^ a b Feller pp. 131–2

- ^ a b c d Söhnen-Thieme pp. 45–48

- ^ Feller pp. 132–35

- ^ "Expiation of sin". The Hindu. Chennai. 25 June 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

{{cite news}}:|archive-url=is malformed: liveweb (help) - ^ a b Söhnen-Thieme p. 45

- ^ Goldman p. 36

- ^ Ganguli, Kisari Mohan (1883–1896). "CCLXVI". The Mahabharata Book 12: Shanti Parva.

- ^ Doniger pp. 95–6

- ^ Doniger pp. 92–3

- ^ Söhnen-Thieme p.56-8

- ^ Doniger p. 94

- ^ Doniger pp. 96–7

- ^ Dhody, Chandan Lal (1995). The Adhyātma Rāmāyaṇa: concise English version. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. pp. 17–20. ISBN 81-85880-77-8.

- ^ Heinrich von Stietencron, P. Flamm, ed. (1992). Epic and Purāṇic bibliography (upto 1985): A-R. Vol. 1. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 688. ISBN 3-447-03028-3.

- ^ Kālidāsa, C.R. Devadhar (1997). "Verse 33–34, Canto 11". Raghuvamśa of Kālidāsa. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 203–4, 606.

- ^ Patel, Gautam (1994). "Sitatyaga, whether wrote it first". In Pierre-Sylvain Filliozat, Satya Pal Narang, C. Panduranga Bhatta (ed.). Pandit N.R. Bhatt, felicitation volume. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. pp. 105–6. ISBN 81-208-1183-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Mirashi, V. V. (1996). Bhavabhūti. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. pp. 113, 150. ISBN 81-208-1180-1.

- ^ Söhnen-Thieme p.58-9

- ^ a b Varadpande, Manohar Laxman (2005). History of Indian theatre. Abhinav Publications. p. 100. ISBN 81-7017-430-9.

- ^ Ramanujan, A. K. (1991). "Three Hundred Rāmāyaṇas:". In Richman, Paula (ed.). Many Rāmāyaṇas: the diversity of a narrative tradition in South Asia. University of California Press. pp. 28–32. ISBN 0-520-07589-7.

- ^ Zvelebil, Kamil (1973). The smile of Murugan on Tamil literature of South India. BRILL. p. 213. ISBN 90-04-03591-5.

- ^ a b "Descent One (Bālakāṇḍa)". Śrīrāmacaritamānasa or The Mānasa lake brimming over with the exploits of Śrī Rāma (with Hindi text and English translation). Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh, India: Gita Press. 2004. pp. 147–148. ISBN 81-293-0146-6.

- ^ a b Prasad pp. 145–6

- ^ Prasad pp. 22, 158, 180, 243, 312, 692

- ^ Rambhadracharya 2006, pp. 101, 269

- ^ Doniger pp. 101–3

- ^ Rao, Velcheru Narayana (2001). "The Politics of Telugu Ramayanas". In Richman, Paula (ed.). Questioning Rāmāyaṇas: a South Asian tradition. University of California Press. pp. 168–9. ISBN 0-520-22074-9.

- ^ Doniger p. 100

- ^ PREMA NANDAKUMAR (28 March 2006). "Myth as metaphor in feminist fiction". The Hindu. Archived from the original on July 20, 2008. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Dwyer, Rachel (2006). Filming the Gods: Religion and Indian Cinema. Routledge. p. 60. ISBN 0-415-31425-9.

- ^ See English translation in Gill, Tejwant Singh (2005). "Artist". Sant Singh Sekhon: selected writings. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 251–304. ISBN 81-260-1999-9.

- ^ a b Mani p. 285

- ^ Goldman pp. 221

- ^ Pattanaik, Devdutt (2001). The man who was a woman and other queer tales of Hindu lore. Routledge. pp. 49–50. ISBN 9781560231813.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Freeman, Rich (2001). "Thereupon hangs a tail: the Deification of Vali in the Teyyam worship of Malabar". In Richman, Paula (ed.). Questioning Rāmāyaṇas: a South Asian tradition. University of California Press. pp. 201–4. ISBN 0-520-22074-9.

- ^ Pattanaik, Devdutt (2000). The goddess in India: the five faces of the eternal feminine. Inner Traditions / Bear & Company. p. 109.

- ^ Bulcke, Father Dr. Camille (2010). Rāmakathā and other essays. Vani Prakashan. pp. 129–31. ISBN 978-93-5000-107-3.

- ^ Headley, Zoé E. (2011). "Caste and Collective Memory in South India". In Isabelle Clark-Decès (ed.). A Companion to the Anthropology of India. Blackwell Companions of Anthropology. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 104–5. ISBN 978-1-4051-9892-9.

- ^ a b c d Chattopadhyaya, Kamaladevi (1982). Indian women's battle for freedom. Abhinav Publications. pp. 13–4.

- ^ a b c Mukherjee pp. 48–9

- ^ Mukherjee p. 36

- ^ a b c Dallapiccola, Anna L. (2002). "Ahalya". [[Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend]]. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd. ISBN 0-500-51088-1. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

{{cite book}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ Swami Vijnanananda (1921–22). "The Ninth Book: Chapter XVIII". The S'rîmad Devî Bhâgawatam.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ a b Bhattacharya, Pradip (Nov–December 2004). "Five Holy Virgins, Five Sacred Myths: A Quest for Meaning (Part V)" (PDF). Manushi (145): 30–37.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Kelkar, Meena K (1995). Subordination of woman: a new perspective. Discovery Publishing House. pp. 59–60. ISBN 81-7141-294-7.

- ^ "Lessons from the Ahalya episode". The Hindu. Chennai. 30 September 2002. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

{{cite news}}:|archive-url=is malformed: liveweb (help) - ^ Doniger pp. 84–5

- ^ Jensen, Herman (2002). A classified collection of Tamil proverbs. Asian Educational Services. p. 398. ISBN 81-206-0026-6.

- ^ Bacchetta, Paola (2002). "Hindu Nationalist Women Imagine Spatialites/Imagine Themselves". In Paola Bacchetta, Margaret Power (ed.). Right-wing women: from conservatives to extremists around the world. Routledge. pp. 50–1. ISBN 0-415-92778-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ Feldhaus, Anne (1998). Images of women in Maharashtrian society. SUNY Press. p. 207. ISBN 0791436594.

- ^ Kapoor, Subodh (2002). Encyclopaedia of ancient Indian geography. Vol. 1. Cosmo Publications. p. 16. ISBN 81-7755-298-8.

- ^ Ganguli, Kisari Mohan (1883–1896). "LXXXIV". The Mahabharata Book 3: Vana Parva.

- ^ "Tourist Spots in Darbhanga: Ahilya Asthan". Official site of Darbhanga District. ational Informatics Center ,District Unit Darbhanga. 2006. Archived from the original on July 15, 2006. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- ^ Benton (2006). God of desire: tales of Kāmadeva in Sanskrit story literature. State University of New York. p. 79. ISBN 0-7914-6565-9..

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help)

References

- Doniger, Wendy (1999). "Indra and Ahalya, Zeus and Alcmena". Splitting the difference: gender and myth in ancient Greece and India. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-15641-9.

- Feller, Danielle (2004). "Indra, the lover of Ahalya". The Sanskrit epics' representation of Vedic myths. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 81-208-2008-8.

- Goldman, Robert P. (1990). The Ramayana Of Valmiki: Balakanda. The Ramayana Of Valmiki: An Epic Of Ancient India. Vol. 1. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01485-X.

- Mani, Vettam (1975). Puranic Encyclopaedia: A Comprehensive Dictionary With Special Reference to the Epic and Puranic Literature. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 0842-60822-2.

- Mukherjee, Prabhati (1999). Hindu Women: Normative Models. Calcutta: Orient Blackswan. ISBN 81 250 1699 6.

- Prasad, Rama Chandra (1990). Tulsidasa's Shri Ramacharitamanasa: The Holy Lake of the acts of Rama. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-0443-2.

- Rambhadracharya, Swami (March 30, 2006). Ahalyoddhāra (in Hindi). Chitrakuta, Uttar Pradesh, India: Jagadguru Rambhadracharya Handicapped University.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Richman, Paula, ed. (2008). Ramayana stories in modern South India: an anthology. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34988-0.

- Söhnen-Thieme, Renate (1996). "The Ahalya Story through the ages". In Leslie, Julia (ed.). Myth and mythmaking: Continuous Evolution in Indian tradition. Curzon Press. ISBN 0-7007-0303-9.