Undid revision 416997857 by Gfoley4 (talk) looking back... although it was unexplained removal of content, the content was unsourced. |

|||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

Pikes Peak is made of a characteristic pink [[granite]] called [[Pikes Peak granite]]. The pink color is due to a large amount of [[Orthoclase|potassium feldspar]]. The granite was once [[magma]] that crystallized at least [[{{convert|20|mi}} beneath the Earth's surface. It was formed by an igneous intrusion during the [[Precambrian]], approximately 1.05 billion years ago, during the [[Grenville orogeny]]. Through the process of [[Tectonic uplift|uplifting]] the hardened rock pushed through the Earth's crust and created a dome-like structured mountain, which was covered with less resistant rock. Years of [[erosion]] and [[weathering]] removed the soil and rock leaving the mountain we view today. |

Pikes Peak is made of a characteristic pink [[granite]] called [[Pikes Peak granite]]. The pink color is due to a large amount of [[Orthoclase|potassium feldspar]]. The granite was once [[magma]] that crystallized at least [[{{convert|20|mi}} beneath the Earth's surface. It was formed by an igneous intrusion during the [[Precambrian]], approximately 1.05 billion years ago, during the [[Grenville orogeny]]. Through the process of [[Tectonic uplift|uplifting]] the hardened rock pushed through the Earth's crust and created a dome-like structured mountain, which was covered with less resistant rock. Years of [[erosion]] and [[weathering]] removed the soil and rock leaving the mountain we view today. |

||

==Name== |

|||

During the period of exploration in Colorado, many would refer to the mountain as "Pike's Peak," after [[Zebulon Pike]], the man who first documented it and attempted to climb to its summit. The attempt failed to reach the summit, since it was made during the wintertime. The snow drifts were reported chest-high at the time of the climb. |

|||

[[Edwin James (scientist)|Edwin James]] was the first human being known to have reached the summit, during a summer climb. Later, some suggested calling it "James' Peak", but in the same area there was another "James' Peak", which made identification a confusing problem. The name went back and forth until it was settled with a uniquely identifiable name. |

|||

Originally the peak was called "Pike's Peak", but in 1891, the newly formed [[United States Board on Geographic Names|U.S. Board on Geographic Names]] recommended against the use of [[apostrophe]]s in any geographical names, so ''officially'' the name of the mountain does not include an apostrophe. In addition, in 1978 the [[Colorado General Assembly|Colorado state legislature]] passed a law mandating the use of "Pikes Peak" only. Even so, the old name is often used. |

|||

==Discovery (by non-Native Americans)== |

==Discovery (by non-Native Americans)== |

||

Revision as of 16:34, 6 March 2011

| Pikes Peak | |

|---|---|

Pikes Peak towers above the city of Colorado Springs | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 14,115 ft (4,302 m) NAVD 88[1] |

| Prominence | 5,510 ft (1,680 m)[2] |

| Listing | Ultra Colorado Fourteener |

| Geography | |

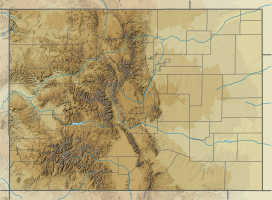

| Location | El Paso County, Colorado, USA near Colorado Springs |

| Parent range | Front Range |

| Topo map | USGS Pikes Peak |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | ~ 1.05 Gyr |

| Mountain type | granite |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 1820 by Edwin James and party |

| Easiest route | cog railroad or drive |

Pikes Peak (originally Pike's Peak, see below) is a mountain in the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains, 10 miles (16 km) west of Colorado Springs, Colorado, in El Paso County. The mountain is located within the Pike National Forest. It was renamed from "El Capitan", which the Spanish settlers had referred to it for decades, to Pike's Peak after Zebulon Pike, an explorer who led an expedition to the southern Colorado area in 1806. At 14,115 feet (4,302 m),[1] it is one of Colorado's 54 fourteeners. Drivers race up the mountain in a famous annual race called the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb. The peak is also the site of the annual Pikes Peak Ascent and Marathon foot races on Barr Trail. The upper portion of Pikes Peak is a federally-designated National Historic Landmark.

Geography and geology

Much of the fame of Pikes Peak is due to its location along the eastern edge of the Rockies. Pikes Peak is the easternmost fourteen thousand foot peak in the United States. It lies 37 miles (60 km) west of Colorado Springs (traveling by road). Unlike most other similarly tall mountains in Colorado, it serves as a visible landmark for many miles to the east, far into the Great Plains of Colorado. As one drives south on Interstate 25 toward the city of Colorado Springs, it comes into view from a distance of more than 65 miles (105 km). On a clear day, the peak can be seen as far as from Denver (more than 60 miles (97 km) north), from points south of Pueblo (up to 76 miles (122 km)), from locations east of Limon (85 miles (137 km)), and from the eastern part of Highway 94 (95 miles (153 km)).

Pikes Peak is made of a characteristic pink granite called Pikes Peak granite. The pink color is due to a large amount of potassium feldspar. The granite was once magma that crystallized at least [[20 miles (32 km) beneath the Earth's surface. It was formed by an igneous intrusion during the Precambrian, approximately 1.05 billion years ago, during the Grenville orogeny. Through the process of uplifting the hardened rock pushed through the Earth's crust and created a dome-like structured mountain, which was covered with less resistant rock. Years of erosion and weathering removed the soil and rock leaving the mountain we view today.

Discovery (by non-Native Americans)

The first non-natives to sight Pikes Peak were the early Spanish settlers and it is well documented in the De Anza punitive expedition of 1779, over 25 years before Zebulon Pike. Its first sighting by non-natives is often falsely credited to members of the Pike expedition, led by Zebulon Pike. After a failed attempt to climb to the top in November 1806, Pike wrote in his journal (emphasis added)[citation needed]:

- ...here we found the snow middle deep; no sign of beast or bird inhabiting this region. The thermometer which stood at 9° above 0 at the foot of the mountain, here fell to 4° below 0. The summit of the Grand Peak, which was entirely bare of vegetation and covered with snow, now appeared at the distance of 15 or 16 miles (26 km) [24–26 km] from us, and as high again as what we had ascended, and would have taken a whole day's march to have arrived at its base, when I believed no human being could have ascended to its pinical [sic]. This with the condition of my soldiers who had only light overalls on, and no stockings, and every way ill provided to endure the inclemency of the region; the bad prospect of killing any thing to subsist on, with the further detention of two or three days, which it must occasion, determined us to return.

This entry has led to an oft-stated claim that Pike said no one had ever, nor would ever reach the top of Pike's Peak. Placed in context, he is making a reasonable assessment of his men's prospects of reaching the top in difficult circumstances.

History

Approximately 200 years before white settlers arrived in the area, several Indian tribes including the Ute, Comanche, Kiowa, Cheyenne, and Arapaho, tribes, moved southward from the Rocky Mountains to occupy the Pikes Peak site.[citation needed]

The first European to climb the peak came 14 years after Pike in the summer of 1820. Edwin James, a young student who had just graduated from Middlebury College in Vermont, signed on as the relief botanist for the Long Expedition after the first botanist had died. The expedition explored the South Platte River up as far as present-day Denver, then turned south and passed close to what James called "Pike's highest peak." James and two other men left the expedition camped on the plains and climbed the peak in two days, encountering little difficulty. Along the way, he was the first to describe the blue columbine, Colorado's state flower.

Gold was discovered in the area of present-day Denver in 1858, and newspapers referred to the gold-mining area as "Pike's Peak." Pike's Peak or Bust became the slogan of the Colorado Gold Rush (see also Fifty-Niner). This was more due to Pikes Peak's visibility to gold seekers travelling west across the plains than any actual significant gold find anywhere near Pikes Peak. Major gold deposits were not discovered in the Pikes Peak area until the Cripple Creek Mining District was discovered southwest of Pikes Peak, and led in 1893 to one of the last major gold rushes in the lower forty-eight states.

In July 1860, Clark, Gruber and Company began minting gold coins in Denver bearing the phrase "Pike's Peak Gold" and an artist's rendering of the peak on the obverse. As the artist had never actually seen the peak, it looks nothing like it. In 1863 the U.S. Treasury purchased their minting equipment for $25,000 to open the Denver Mint.

Katharine Lee Bates was moved to write the words to the famous song "America the Beautiful" in July, 1893, after having traveled to the top of Pikes Peak on a carriage ride. She had traveled by train from Chicago through Kansas. The words began to come to her while admiring the view from Pikes Peak, and she wrote the song out that night at her hotel in Colorado Springs. There is a plaque commemorating this with the words to "America the Beautiful" at the summit.

In 1899 Pike’s Peak became the epicenter for conducted experiments by the famous electrician and inventor Nikola Tesla. Pike’s Peak was chosen for its remote location and its adjacency to the El Paso Power Company of Colorado Springs, offering a supreme source of electrical energy for research. Leonard E. Curtis, friend and lawyer associated with Tesla, scouted the acreage available. Paying the lump sum of $30,000, a well-constructed laboratory with plenty of surrounding land awaited Nikola Tesla on his arrival in May of 1899. The laboratory was massive in size, including intense floor to ceiling wiring, a detachable rooftop, and an eighty-foot tall wooden tower. After dubious inspection, the land was decided to be a suitable site for the first radio single sent from Colorado to Paris, France. During his ultimate experiment, labeled The Pike’s Peak Experiment, Tesla and his assistant Kolman Czito opened electricity on his coil wires; one sanctioned within the El Paso Electric Company and the other grounded on his acreage. The power was only open for one second but this second alone caused the secondary coil to ignite with a blue fire of current that shattered the air around it with man-made lightning more than a hundred feet long at times. This experiment caused the entire city to lose power, and damaged the El Paso electric Company; Tesla was forced to pay for any damages or misfortune. The purpose of the Pike’s Peak Experiment was to transmit electricity wirelessly to different parts of the earth, Tesla followed up this experiment with many others, including the lighting of vacuum tubes planted strategically into the ground. The actual cause of this mysterious lighting was never agreed upon; most claim it was caused by the Colorado soil and its conductive properties. Tesla, of course attributed it to wireless transmission. Tesla and his company continued to conduct many other experiments within Pike’s Peak over the course of the next nine months but none equaled in prestige to Pike’s Peak. Although rumors of electrical oscillation and detected radio waves from space did occur. Not all were impressed with the controversial experimentation, some citizen of the city were violently taken aback; there were even speculations of campaigns conducted against Nikola Tesla by Thomas Edison who supported direct current instead of alternating current. Encouraged by his successes in Colorado Tesla left Pike’s Peak in January 1900 to return to New York and continue is innovative and ground-breaking work. [3]

The uppermost portion of Pikes Peak, defined as that part above 14,000 feet (4,300 m) elevation, was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1961.[4][5]

Pikes Peak today

There are several visitor centers on Pikes Peak, some with a gift shop and restaurant. These centers are located at 6 mile, 12-mile (19 km) and the summit itself, and there are several ways to ascend the mountain. The Manitou and Pike's Peak Railway is a cog railroad operating from Manitou Springs to the summit year-round, conditions permitting. Automobiles can be driven to the summit via the Pikes Peak Highway, a 19 mile (31 km) road that starts a few miles up Ute Pass at Cascade. This road, which was unpaved after the halfway point, was made famous worldwide by the short film Climb Dance featuring Ari Vatanen racing his Peugeot automobile up the steep, twisty slopes as part of the annual Pikes Peak International Hill Climb race. The road has a series of switchbacks, treacherous at high speed, called "The W's" for their shape on the side of the mountain. The road is maintained by the city of Colorado Springs as a toll road.

A project to pave the remainder of the road is scheduled to be completed by 2012. The project is in response to a suit by the Sierra Club over damage caused by the gravel and sediment that is constantly washed off the road into the alpine environment.[6][7] The road remains open during construction.

The most popular hiking route to the top is called Barr Trail, which approached the summit from the east. The trailhead is just past the cog railway depot in Manitou Springs. Visitors can walk, hike, or bike the trail. Runners race to the top and back on Barr Trail in the annual Pikes Peak Marathon. Another route begins at Crags Campground, approaching the summit from the west.[8][9]

Conditions at the top are typical of a high alpine environment. The thin air contains only 60% of the oxygen available at sea level. Snow is a possibility any time year-round, and thunderstorms are common in the summer, bringing hail and wind gusts occasionally of over 100 mi/hr (160 km/h). Lightning is especially dangerous above the treeline. A signboard at the cog railway depot in Manitou Springs provides the summit temperature every day, a number that is rarely higher than 40 °F (4 °C), even in mid-summer.[citation needed]

Since 1969, the summit of Pikes Peak has been the site of the United States Army Pike’s Peak Research Laboratory, a medical research laboratory for the assessment of the impact of high altitude on human physiological and medical parameters of military interest.

Pikes Peak was the home of a ski resort from 1939 through 1984,[10] but that one closed due to a chronic lack of snow falls. Pikes Peak does not receive the massive snowfalls that some other mountains in Colorado do. Expensive snowmaking was required to make the resort feasible, and the high winds on Pikes Peak often blew the artificial snow away.

References

- ^ a b c "NGS Data Sheet for Pikes Peak". National Geodetic Survey.

- ^ "Pikes Peak, Colorado". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2011-02-22.

- ^ "Tesla-Master of Light". Retrieved 02-28-2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Pike's Peak". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- ^ Joseph Scott Mendinghall (December 1, 1975). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Pike's Peak" (Document). National Park Service.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|format=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) and Template:PDFlink - ^ Jon Karroll (2009-07-28). "Clock Ticking On Pikes Peak Paving Project". KRDO News Channel 13. Retrieved 2009-08-28. [dead link]

- ^ "Paving Pikes Peak -- slow and spendy defines the race". The (Colorado Springs) Gazette. 2006-11-26. Retrieved 2009-08-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authro=ignored (help) - ^ 14ers.com

- ^ OneDayHikes.com

- ^ http://www.coloradoskihistory.com/lost/pikespeak.html

Further reading

- Rocky Mountain National Park: High Peaks: The Climber's Guide, Bernard Gillett, (Earthbound Sports; 2001) ISBN 0-9643698-5-0

- Rock and Ice Climbing Rocky Mountain National Park: The High Peaks, Richard Rossiter, (Falcon; 1996) ISBN 0-934641-66-8

Gallery

-

View to the northeast from the summit of

Pikes Peak -

Pikes Peak

viewed from

Colorado Springs -

The observation tower atop Pikes Peak

(1959)

See also

External links

- Manitou Springs: The Gateway to Pikes Peak | Official Visitor's Site

- The Pikes Peak Web site

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Pikes Peak

- Live webcam view of Pikes Peak

- Rocky Mountains @ Peakbagger

- Santa Fe Trail Research Site

- Satellite Image of Pikes Peak from Google Maps

- Pikes Peak on 14ers.com

- Pikes Peak on Bivouac.com

- Pikes Peak Country "Pikes Peak Travel Information" page

- Pikes Peak Cog Railway "About Pikes Peak" page

- Pikes Peak weather forecast

- Pikes Peak Panoramic Camera

- Computer generated summit panoramas North South index