We asked a group of engines to summerize a white paper about uses of cannabis. This is the response:

This paper provides a comprehensive analysis of traditional uses of Cannabis based on data from the CANNUSE database, which contains 2330 entries from 41 countries. Here are the key points:

1. Uses:

– Medicinal use was the most common (75.41%), followed by psychoactive (8.35%) and alimentary (7.29%) uses.

– 210 different human ailments were treated with Cannabis.

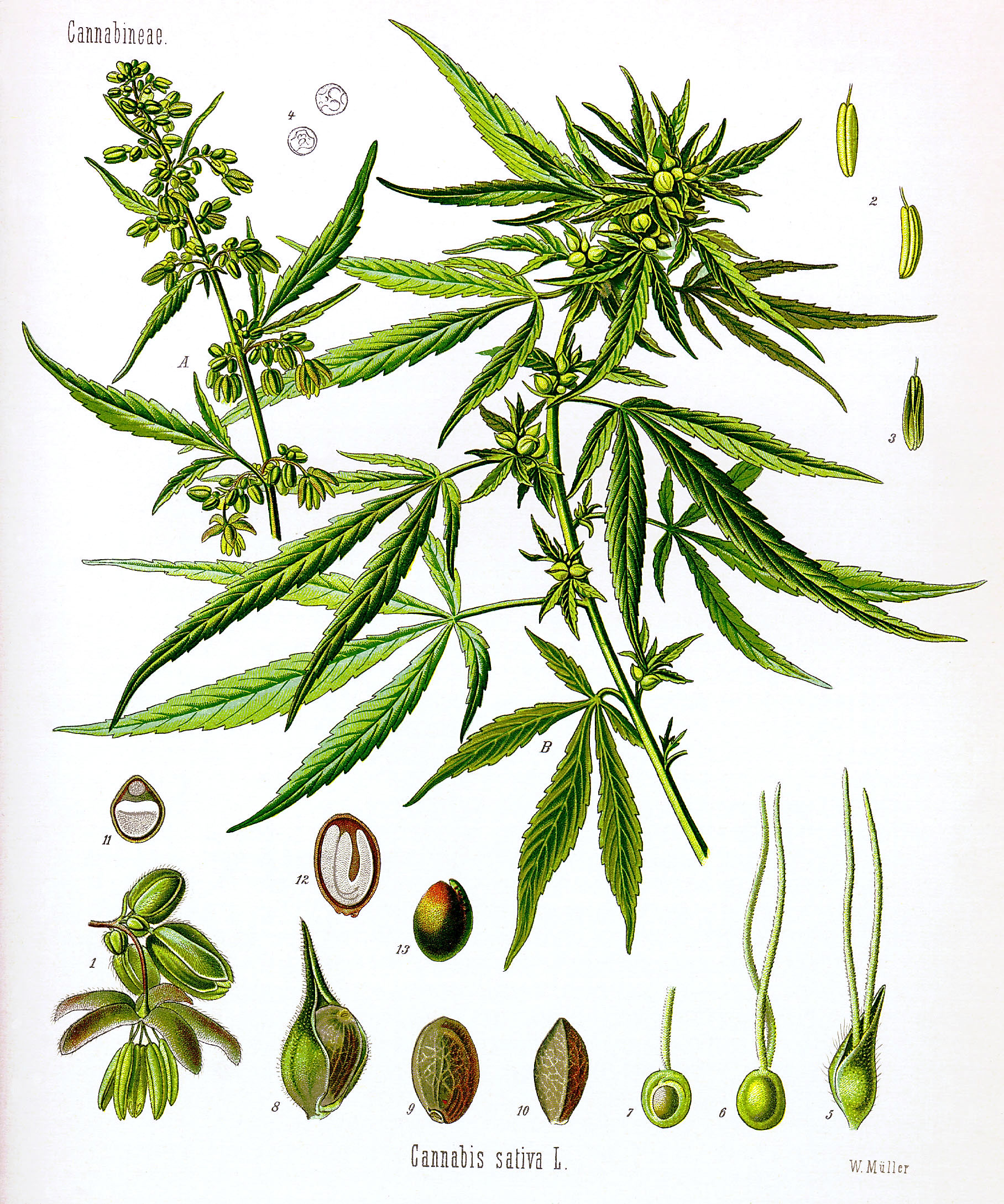

2. Plant parts used:

– Leaf was the most commonly used part (50.51%), followed by seed (15.38%) and inflorescence (11.35%).

– Different plant parts were significantly associated with specific uses:

– Leaf: medicinal use

– Seed: alimentary use

– Inflorescence: psychoactive use

3. Medicinal uses:

– Most common treatments were for digestive system disorders, nervous system disorders, and pain/inflammation.

– Specific associations were found between plant parts and treatments:

– Leaf: skin disorders and circulatory system issues

– Seed: musculoskeletal disorders

– Inflorescence: nervous system and mental disorders

4. Regional differences:

– Most data came from India and Pakistan, with some variations in uses between countries.

5. Other findings:

– 211 vernacular names for Cannabis were recorded.

– Only 3.24% of entries reported toxic effects.

6. Conclusions:

– Traditional uses of Cannabis are diverse and not limited to psychoactive effects.

– Different plant parts have specific medicinal applications, which could inform future research and drug development.

– The study highlights the potential of ethnobotanical data in guiding modern medical research on Cannabis.

The authors emphasize that while current pharmaceutical research focuses mainly on Cannabis inflorescences, traditional medicine utilized all parts of the plant for various purposes, suggesting untapped potential in other plant parts for medical applications.

Citations:

Traditional uses of Cannabis An analysis of the CANNUSE database